Abstract

Aims:

RALA is a novel 30 mer bioinspired amphipathic peptide that is showing promise for gene delivery. Here, we used RALA to deliver the FK506-binding protein like – FKBPL gene (pFKBPL) – a novel member of the immunophilin protein family. FKBPL is a secreted protein, with overexpression shown to inhibit angiogenesis, tumor growth and stemness, through a variety of intra- and extracellular signaling mechanisms. We also elucidated proangiogenic activity and stemness after utilizing RALA to deliver siRNA (siFKBPL).

Materials & methods:

The RALA/pFKBPL and RALA/siFKBPL nanoparticles were characterized in terms of size, charge, stability and toxicity. Overexpression and knockdown of FKBPL was assessed in vitro and in vivo.

Results:

RALA delivered both pFKBPL and siFKBPL with less cytotoxicity than commercially available counterparts. In vivo, RALA/pFKBPL delivery retarded tumor growth, and prolonged survival with an associated decrease in angiogenesis, while RALA/siFKBPL had no effect on tumor growth rate or survival, but resulted in an increase in angiogenesis and stemness.

Conclusion:

RALA is an effective delivery system for both FKBPL DNA and RNAi and highlights an alternative therapeutic approach to harnessing FKBPL's antiangiogenic and antistemness activity.

Keywords: : antiangiogenic, FKBPL DNA, nanoparticle, RALA peptide, RNAi

Background

Nucleic acid therapeutics are gaining momentum for a wide range of disease states [1]. Whether the nucleic acid is designed to augment or repress a target gene of interest; an effective delivery system is required. There are numerous intra- and extracellular barriers that can impede successful nucleic acid delivery [2]. A successful gene delivery vector must be efficient, nonimmunogenic, targeted and relatively easy to manufacture. The delivery vehicle must also protect the nucleic acid cargo, facilitate intracellular transport, disrupt endosomes to reach the cytoplasm for siRNA delivery and actively transport to the nucleus for DNA delivery [3,4]. Effective delivery, targeting and a lack of toxicity are key criteria, if such nucleic acid therapeutics are ever going to become a clinical reality. Although viral vectors are highly efficient, they are somewhat limited by induction of immune responses, nonspecific insertion, oncogene activation, high manufacturing costs and perhaps most importantly patient perception [5,6]. Nevertheless, viruses have a key role to play in the design of their nonviral counterparts.

While nonviral vectors have traditionally been less efficacious, the field has moved toward the creation of bioinspired viral mimetic systems with considerable success [7–9]. Hatefi's group have created numerous multifunctional nonviral delivery systems with discrete interchangeable motifs, each one of which is designed to overcome a specific biological barrier [10,11]. While such systems are excellent examples of what can be achieved, the large-scale production of such recombinant proteins can be time-consuming and therefore peptide-mediated gene delivery presents a highly attractive option. Many amphipathic membrane destabilizing peptides have been developed over recent years, but the most publicized have been the anionic membrane destabilizing peptide, GALA, which requires conjugation of a positively charged ligand to facilitate delivery of nucleic acid, and the cationic delivery systems, CADY, KALA and RAWA, which allow independent delivery of nucleic acid [4,12,13].

The newest addition to this group, RALA, was developed by McCarthy et al. (2014) [14]. RALA is a 30-amino acid peptide modified from the KALA structure by substitution of lysine groups with arginine. The rationale was that the α-helicity of KALA over a wide pH range contributes to its toxicity; arginine is positively charged in neutral, acidic and most basic environments, making RALA more responsive to the low pH found in the endosome, causing α-helicity selectively in the endosome and theoretically minimizing toxicity. Characterization indicated that RALA is an effective DNA delivery platform with increased α-helicity in lower pH, does not affect viability in vitro and successful reporter gene delivery following systemic administration in vivo. Knowing that RALA can successfully deliver reporter gene DNA, we wanted to assess the benefits of RALA-mediated delivery of a therapeutic transgene, FKBPL.

FK506-binding protein like – FKBPL, is a novel member of the immunophilin protein family; these proteins have wide-ranging intra- and extracellular roles in a host of diseases through their chaperoning and PPIase activity [15]. FKBPL is emerging as a key player in the DNA damage response [16], steroid receptor signaling [17,18] and more recently, control of tumor growth where it regulates response to endocrine therapy [19] as well as acting as a novel secreted antiangiogenic protein, where it inhibits endothelial cell migration and has potent antitumor activity in vivo [20,21]; this effect is dependent on the cell surface receptor CD44 [22]. More recently, we have demonstrated that because of FKBPL's ability to target the cell surface receptor, CD44, we are also able to reduce cancer stem cells [23]. Finally, in a meta-analysis of 3277 patients from five breast cancer cohorts, FKBPL levels were a significant and independent predictor of breast cancer-specific survival, indicating superiority over current prognostic markers, not surprising giving the antitumor activity of this protein [24]. A therapeutic peptide, ALM201, based on the antiangiogenic domain has now entered Phase I/II clinical trials (EudraCT number: 2014–001175–31).

Here, and for the first time, we investigated the delivery of pFKBPL using the novel RALA peptide as a gene delivery approach to increasing endogenous FKBPL levels for therapeutic benefit. Furthermore, delivery of siFKBPL via RALA to reduce FKBPL levels was also investigated. This had only previously been achieved in vitro by inhibiting the activity of secreted FKBPL, using an inhibitory antibody, so blocking its exogenous interaction with CD44, as well as via delivery of FKBPL siRNA (siFKBPL) using Oligofectamine™, both of which increased cell migration [20,22]. We were able to demonstrate that RALA is an effective delivery system for both FKBPL DNA and RNAi and provides an alternative approach to harnessing FKBPL's antitumor activity.

Materials & methods

Materials

RALA peptide

RALA peptide (Biomatik, DE, USA) was produced by solid-state synthesis, and supplied as a lyophilized powder, with the purity defined as desalted. The 30 amino acid sequence of RALA is as follows: N-WEARLARALARALARHLARALARALRACEA-C.

pDNA

Glycerol stocks containing pFKBPL (prepared as described previously in [17,20]) or empty vector plasmid (pEV) (pcDNA3.1, Invitrogen, UK) were prepared and extracted using a PureLink® HiPure Plasmid Filter Maxiprep Kit (Life Technologies, UK). Plasmid purity and DNA concentration was confirmed by using the NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, UK); DNA (1 µg/µl) having a 260/280 nm ≥1.8 was used for nanoparticle formation.

siFKBPL

siFKBPL (Invitrogen, UK) was supplied at a 20 nM concentration. It comes as three siRNA designed to be used together to achieve transient knockdown.

F1 (GGAGACGCCACCAGUCAAUACAAUU)

F2 (GCUGAACUUGAAGGAGACUCUCAUA)

F3 (CAGCCAAAUUCUAGAGCAUACUCAA)

Cell lines

ZR-75–1 breast cancer cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection and cultivated in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% O2. Cells were routinely verified to be Mycoplasma free, and were authenticated by short tandem repeat profiling carried out by the supplier.

Animals

Female, 6-week-old SCID mice were obtained from Harlan Laboratories, UK and housed in a specified pathogen-free facility at 21°C and 50% humidity with food and water ad libidum. The experimental protocols were compliant to the UK Scientific Act of 1986 and project license 2678.

Methods

Preparation of RALA-DNA & RALA-siRNA nanoparticles

DNA and siRNA complexes were prepared at N:P ratios 0–15 by adding appropriate volumes of peptide solution to 1 µg DNA or siRNA as detailed in McCarthy et al. (2014) [14]. FKBPL siRNA is comprised of three individual siRNA, F1, F2 and F3 that were pooled together after 30 min incubation at room temperature.

Gel retardation assay

Complexes were prepared and electrophoresed through a 1% agarose gel containing 0.01% ethidium bromide (1 mg/ml; BioRad, CA, USA) with 1× TAE buffer (Invitrogen, UK) at 80 V for 60 min. The gel was then imaged under UV light using a UVP Bioimaging System (UVP, UK).

Complex size & zeta potential analysis

The mean hydrodynamic size of the complexes was determined by dynamic light scattering on a Malvern Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments, UK). Mean surface charge (zeta potential) of the complexes in each sample was also measured by using Laser Doppler Velocimetry on a Malvern Nano ZS.

Serum stability assay

RALA-pFKBPL complexes were prepared at N:P ratio 10. Samples were incubated ±10% FCS (PAA Laboratories, Austria) for 1–4 h at 37°C. Subsequently, the condensed DNA was decomplexed from RALA by addition of 10% SDS to the required samples, incubated for 10 min and electrophoresed through a 1% agarose gel as above.

Transmission electron microscopy

RALA-siFKBPL complexes were prepared at N:P ratio 10. A Formvar carbon-coated copper 200 mesh transmission electron microscopy (TEM) grid (Agar Scientific, UK) was placed face down into a 10 µl sample of the complex for 10 min, and allowed to dry overnight. A drop of 5% uranyl acetate solution was added to each grid for 4 min before removing excess with filter paper. The grid was imaged at 40,000× magnification using a JEOL 100CXII transmission electron microscope at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV onto Kodak 4489 Electron Microscope Film.

Transfection of ZR-75–1 cells in vitro

ZR-75–1 cells were seeded at a density of 3 × 104 cells per well in a 96-well plate (VWR, UK) and left to adhere for 24 h prior to transfection. Opti-MEM media (Gibco, UK) was added to each well for 2 h. This was then supplemented with RALA-pFKBPL (containing 1 µg pFKBPL) or RALA-siFKBPL (containing 0.125, 0.25 or 1.02 µg siFKBPL) transfection complexes, at N:P ratio 10, for 6 h before addition of RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS. As positive controls, cells were also transfected using the well-established transfection agents, Oligofectamine® (Invitrogen, UK) for siRNA, and Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen, UK). Transfection was carried out for 72 h and cell lysates were harvested by aspiration of the media, followed by addition of Laemmli 2× Sample Buffer (Sigma, UK).

Western blotting

Cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE electrophoresis using a NuPAGE® 4–12% Bis-Tris gel (Novex by Life Technologies, UK) and the XCellSurelock™ electrophoresis cell (Invitrogen, UK), transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, blocked for 1 h at room temperature in 3% skimmed milk powder (Merck, UK) blocking solution in PBS-Tween. The membrane was then probed with 1:1000 dilution of rabbit FKBPL IgG polyclonal primary antibody (Proteintech, UK), 1:5000 dilution of rabbit GAPDH primary antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1:5000 dilution of ECL antirabbit IgG HRP-linked whole secondary antibody (GE Healthcare UK Ltd, UK). Antibody binding was detected using Immobilon™ Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore) and autoradiography films. The resulting films were then scanned by using x-ray imaging on the UVP Bioimaging System (UVP, UK). Densitometric analysis was performed, where FKBPL was quantified relative to GAPDH using ImageJ software and Microsoft Excel. Statistical analysis was performed using One-Way ANOVA with a Dunnett's Multiple Comparison Test using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA).

WST-1 cytotoxicity assay

ZR-75–1 cells were transfected with pFKBPL or siFKBPL using RALA, Oligofectamine or Lipofectamine. After 72 h, the complete media was removed and replaced with 10% WST-1 Reagent (Roche, UK) in Opti-MEM. Cells were incubated for 4 h, at 37°C, the media was harvested onto a fresh 96-well plate, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm on an EL808 plate reader (Biotek Instruments Inc., UK). Statistical analysis was by one-way ANOVA, with p-values less than 0.05 deemed statistically significant.

Delivery of RALA-pDNA & RALA-siRNA complexes in vivo

Manufacture of estrogen pellets

ZR-75–1 cells are an estrogen-dependent cell line; therefore, estrogen pellets each containing 0.5 mg were implanted subcutaneously into the mouse dorsal area at the same time as ZR-75–1 cells. 120 mg estradiol and 9.7 g silicone elastomer were mixed together and 1.1 g silicone elastomer curing agent was added on a weigh-boat. The resulting mixture was spread over two weigh-boats to achieve a thickness of 1 mm, and placed in an oven overnight at 42°C. The estrogen pellets were cut into 2 mm × 2 mm × 1 mm pieces to provide 0.5 mg estrogen per pellet.

ZR-75–1 intradermal implantation to SCID mice

ZR-75–1 cells were centrifuged and reconstituted in PBS, before being diluted 1:1 in Matrigel (BD Biosciences, UK) which was kept in syringes on ice until implantation. 35 SCID mice were anesthetized using isoflurane (Abbott, UK), the dorsal area was shaved and 5 × 106 cells (100 µl) were implanted intradermally. Tumors were allowed to become established and were injected with RALA-pDNA or RALA-siRNA complexes when they reached a volume greater than 100 mm3.

Preparation of RALA complexes for in vivo injection

RALA-pDNA (containing either 5 µg pFKBPL, or 5 µg pEV) and RALA-siRNA (containing either 3 µg siFKBPL or 3 µg nontargeting siRNA [siNT]) complexes were made with an N:P ratio of 10. Particles were prepared on the morning of injection in 50 µl aliquots.

Intratumoral injection

Power calculations, assuming a power of 0.8 were used to determine optimal sample size. Thirty mice were randomized into one of five treatment groups (control, pFKBPL, pEV, siFKBPL siRNA or siNT) after their tumors reached treatment volume. 10 µg of pFKBPL or pEV or 2 µg of siFKBPL or siNT was administered to each mouse twice weekly by intratumoral injection of 100 µl RALA – pDNA/siRNA complex solution.

Measurement of tumor growth

Following treatment, the length (L), breadth (B) and height (H) of tumors were measured twice weekly using calipers. Tumor volume was calculated by 4/3 ∏r3, where r is the half of the geometric mean diameter (GMD), and GMD is the cube root of L × B × H. Mice were also weighed twice weekly to ensure health. When tumors reached a volume greater than 100 mm3, they were eligible to enter treatment with the RALA complexes. Results were presented by using a Kaplan Meier survival curve, and statistical analysis was by Mantel-Cox Log Rank Test with a p-value of ≤0.05 considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed by using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software).

Sacrifice of mice, tissue extraction & IHC analyses

Mice were sacrificed and half of each of the tumors were fixed in 10% formaldehyde. Subsequent paraffin embedding and Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining, and immunohistochemistry staining for FKBPL (Proteintech, UK), CD34 (MEC14.7, ab8158; Abcam Plc, UK), using HRP-conjugated rabbit and rat secondary, respectively, was performed by the Northern Ireland Molecular Pathology Laboratory, QUB. Briefly, FKBPL staining was carried out at a dilution of 1:800 for 1 h using the Ventana Discovery XT Immunostainer (Ventana Medical Systems Inc, AZ, USA). Cell conditioning was achieved using ‘standard’ (36 min) CC1 (Ventana 050–500) and detection of immunoreactivity was with Ventana Chromomap DAB kit (Ventana 760–159). Prior to CD34 staining, 3 µm sections were cut and deparaffinized by sequential incubations in xylene and rehydrated through descending grades of alcohol. CD34 staining was carried out at a dilution of 1/25 followed by application of 1/50 HRP-conjugated antirat secondary antibody (GE Healthcare UK Ltd) and treatment with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAKO). Sections were then counterstained with hematoxylin. Representative comparative images were then selected showing FKBPL, H+E and CD34 staining from the same field of view from high-quality-scanned images on the Northern Ireland Virtual Tissue Archive (NIVTA) pathXL website. The CD34 staining of endothelial cells was then quantified by an independent assessor who was blinded to the treatment received by each tumor. Number of vessels for each field of view were quantified and displayed on a vertical scatter plot as number of CD34 vessels counted per field of view ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired t-test with Welch's Correction using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software). p-values of ≤0.05 were deemed statistically significant.

Cell count & mammosphere assay

The remaining half of the excised tumor was excised and assayed using the ex vivo mammosphere assay, as described previously [23]. Briefly, the tumor was cut into less than 1 mm pieces, disaggregated overnight using DMEM/F12 (Gibco) medium containing 10% collagenase/hyaluronidase (Stem Cell Technologies) and filtered through 100, 70 and 40 µm cell strainers. Live cancer cells were counted by Trypan Blue exclusion assay (Sigma-Aldrich) using a hemocytometer and seeded at a density of 500 cells/cm2 in low adherent 6-well dishes. Cells were cultured for 7 days at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% O2/5% CO2 before mammospheres were counted.

Results

Biophysical characterization of RALA-siFKBPL & RALA-pFKBPL complexes

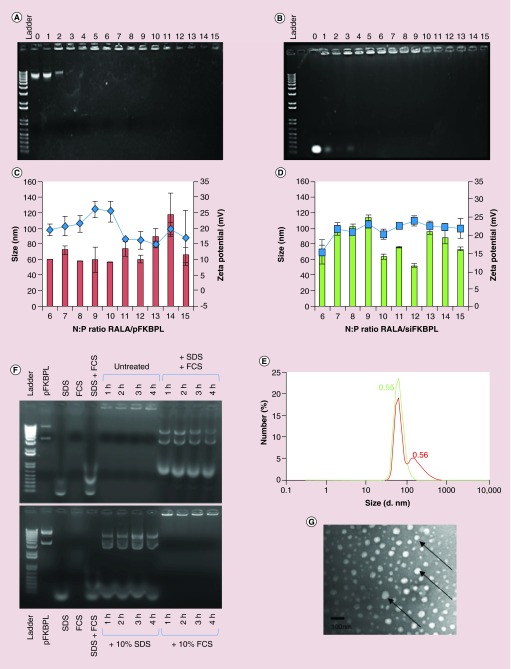

RALA-siFKBPL and RALA-pFKBPL complexes were optimized to establish the N:P ratio at which RALA starts to condense siRNA and DNA. Gel retardation studies, as shown by representative images, demonstrated that this occurred from N:P ratio 3 for pDNA, and N:P ratio 4 for siRNA (Figure 1A & B, respectively). N:P 0, 1 and 2 (and 3 for siRNA) migrated down the agarose gel, indicating that the charge of the DNA/RNA was not sufficiently neutralized to remain in the wells. From N:P 3/4 onward, the RALA-pDNA/siRNA complex remained in the well, suggesting a net positive charge, and that DNA condensation by the RALA peptide had occurred. Size and charge characterization of RALA-pFKBPL and RALA-siFKBPL complexes from N:P 6–15 were suitable for use. A N:P ratio of 10 was selected, displaying ideal size (˜55–65 nm) and charge (˜20–25 mV) characteristics (Figure 1C & D). N:P10 has previously been shown to have the best transfection rate [14]. The Mean Count Rate (MCR, kcps) was greater than 100 for each sample measured, and all complexes had a polydispersity index (PDI) of less than 0.6 (Figure 1E). This is indicative of a heterogenous nanoparticle population; however, the majority of the nanoparticles are less than 200 nm which is still suitable for traversing the cellular membrane (Figure 1E). Assessment of the stability of the complexes over 4 h in serum at 37°C indicated that RALA-pFKBPL complexes were stable alone, and in serum. The study also indicated that after release from the complex using 1% SDS, DNA remained intact compared with naked pDNA (Figure 1F). The lowest bands underneath the dissociated nanoparticles correspond to the SDS and FCS controls. Representative TEM images of RALA-siFKBPL complexes at N:P ratio 10 indicate that these complexes are spherical and confirm the previous measured size range detected in Figure 1C & D. Furthermore there was no evidence of aggregation (Figure 1G).

Figure 1. . Biophysical characterization of RALA-pFKBPL nanoparticles and RALA-siFKBPL nanoparticles.

(A) Gel retardation assay of RALA-pFKBPL nanoparticles from N:P ratio 0–15. (B) Gel retardation assay of RALA-siFKBPL nanoparticles from N:P ratio 0–15; each lane (L–R) represents an increase in N:P ratio from 0 to 15. (C) Particle size and zeta potential of RALA-pFKBPL nanoparticles (bars = size, line = charge). (D) Particle size and zeta potential of RALA-siFKBPL nanoparticles from N:P ratio 6–15 (bars = size, line = charge). (E) Serum stability of RALA -pFKBPL nanoparticles for 4 h at 37°C. (F) Dynamic light scattering of RALA-pFKBPL (red) and RALA-siFKBPL (green) at N:P10 with PDI and (G) transmission electron microscope image of RALA-siFKBPL complexes at N:P 10 with RALA-siFKBPL nanoparticles indicated by arrows.

pFKBPL: FK506-binding protein like – FKBPL gene, delivered using RALA.

In vitro efficacy of RALA as a transfection agent for siFKBPL & pFKBPL in ZR-75–1 cells

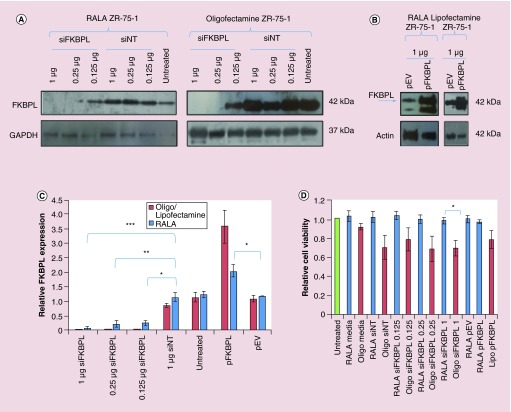

Transfection of ZR-75–1 cells and subsequent analysis by western blotting showed that significant FKBPL knockdown to varying extents was observed with delivery of 0.125, 0.25 µg and most significantly with 1 µg siFKBPL when delivered with RALA (p = 0.006, p = 0.004, p = 0.0007, respectively); FKBPL knockdown was greater following transfection with Oligofectamine (Figure 2A & C), although it was difficult to ascertain significance as the levels were very low. pFKBPL delivery with RALA showed a significant increase in FKBPL expression (p = 0.04) over empty vector but this was greater with Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Figure 2B & C). The relative FKBPL expression is based upon raw data and corrected to GAPDH-loading controls. WST-1 reagent was used to assess the effect of the transfection agents RALA, Lipofectamine 2000 and Oligofectamine on ZR-75–1 cell proliferation. Cells transfected with RALA-siFKBPL and RALA-pFKBPL complexes remained 98–100% viable, whereas cells transfected with Oligofectamine or Lipofectamine 2000 remained only 65–78% viable (Figure 2D). Comparison between RALA and Oligofectamine at the most effective transfection concentration, 1.02 µg showed that Oligofectamine was significantly more toxic to cells than RALA (p = 0.03).

Figure 2. . N:P 10 RALA-siFKBPL and RALA-pFKBPL nanoparticles in vitro.

(A) Western blot for FKBPL expression in ZR-75–1 cells following transfection for 72 h with RALA-siFKBPL or RALA-siNT N:P ratio 10 complexes, and also with Oligofectamine as a positive control. (B) Western blot for FKBPL expression in ZR-75–1 cells following transfection for 72 h with RALA-pFKBPL or RALA-pEV N:P ratio 10, and also with Lipofectamine 2000 as a positive control. (C) Densitometric analysis of RALA-siFKBPL knockdown. n = 3 ± SEM. Statistical analysis was by one-way ANOVA, where *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001. (D) Relative cell viability of ZR-75–1 cells 72 h post-transfection with RALA-siFKBPL and RALA-pFKBPL N:P ratio 10 complexes determined via WST-1 assay. n = 3 ± SEM. Statistical analysis was by t-test, where *p < 0.05.

pEV: Empty vector plasmid; pFKBPL: FK506-binding protein like – FKBPL gene, delivered using RALA; siFKBPL: FKBPL siRNA; siNT: Nontargeting siRNA.

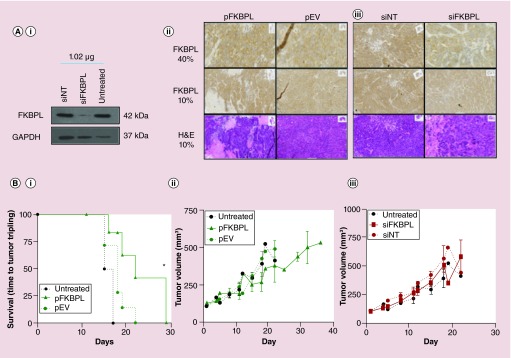

Delivery of RALA-pFKBPL delays tumor growth rate & prolongs survival

Prior to injection of RALA complexes, the ability of the RALA complexes to maintain their transfection efficacy at volumes larger than 50 µL after combination of individual 50 µl batches was assessed by transfection of 2 × 106 cells, followed by western blot analysis. Figures 2B & 3 Ai demonstrated that RALA complexes were efficiently transfected; FKBPL overexpression was observed with RALA-pFKBPL (Figure 2B), and reduced with RALA-siFKBPL, respectively (Figure 3Ai). In vivo intratumoral administration of RALA-pFKBPL significantly prolonged survival (p = 0.042), demonstrated by using tumor volume tripling time as the end point, and also reduced overall tumor growth compared with RALA-FKBPL pEV control (Figure 3Bi & ii). Immunohistochemistry staining for FKBPL revealed tumor necrosis at the experimental end point with a marginal increase in intensity of FKBPL staining after treatment with RALA-pFKBPL (Figure 3Aii). In vivo intratumoral administration of RALA-siFKBPL complexes did not affect ZR-75–1 tumor growth rate compared with RALA-siNT control (Figure 3Biii). However, immunohistochemistry staining for FKBPL revealed a reduction in FKBPL staining compared with control, indicating that there had been successful delivery of siRNA, and FKBPL knockdown, as shown in Figure 3Aiii.

Figure 3. . RALA is a suitable delivery vehicle for FKBPL overexpressing plasmid and FKBPL siRNA in vitro and in vivo.

(Ai) In vitro FKBPL knockdown was confirmed by western blot, representative images of which are shown. Twice weekly in vivo ZR-75–1 intratumoral administration of RALA-pFKBPL or of RALA-siFKBPL resulted in enhanced (ii) or reduced (iii) immunohistochemistry staining for FKBPL respectively, and for RALA-pFKBPL, revealed areas of necrosis at the experimental end point ([i]; bottom panel). Prior to intratumoral injection, 2 × 106 ZR-75–1 cells were transfected with a sample of the in vivo nanoparticle preparation, and FKBPL knockdown. (B) Administration of RALA-pFKBPL significantly prolonged survival (time to tumor tripling) (i) and reduced overall tumor growth (ii) compared with administration of RALA-pEV. However, administration of RALA-siFKBPL showed no difference in tumor growth rate (iii).

pEV: Empty vector plasmid; pFKBPL: FK506-binding protein like – FKBPL gene, delivered using RALA; siFKBPL: FKBPL siRNA; siNT: Nontargeting siRNA.

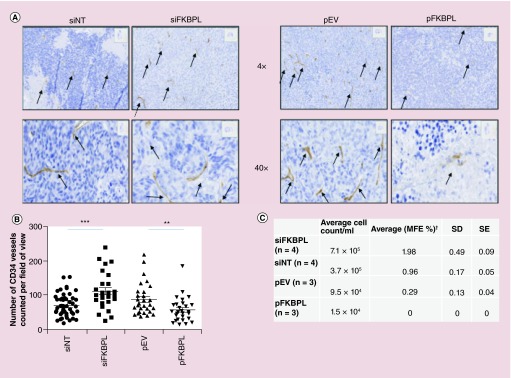

FKBPL knockdown & overexpression effects tumor vasculature, viable tumor cell number & mammosphere forming efficiency

Delivery of RALA-siFKBPL visibly resulted in an increase in MVD as measured by immunohistochemistry staining for CD34, compared with RALA-siNT, while delivery of RALA-pFKBPL visibly reduced MVD compared with RALA-pEV control as shown in Figure 4A. Quantification of blood vessels, using the endothelial cell marker, CD34, were carried out by an independent assessor, blinded to the treatment groups. As displayed in Figure 4B, the number of vessels in each field of view on tumor sections was counted, confirming a significant decrease in vessel number when RALA-pFKBPL was delivered compared with RALA-pEV (p = 0.007), and a significant increase in vessel number when RALA-siFKBPL was delivered compared with RALA-siNT (p = 0.0006). Furthermore, MVD correlated with viable cell numbers within disaggregated tumor xenografts. The number of viable cells was higher in the FKBPL knockdown xenografts (supported by more vessels) and lower in the pFKBPL xenografts (supported by less vessels and associated with tumor necrosis) compared with their respective controls, siNT or pEV control (Figure 4C); this confirms that pFKBPL may decrease tumor survival while FKBPL knockdown increases survival.

Figure 4. . In vivo ZR-75–1 intratumoral administration of RALA-pFKBPL or RALA-siFKBPL.

(A) Representative images of stained tumor sections following delivery of RALA-siFKBPL or RALA-pFKBPL at 4× and 40× are shown, with vessels marked with arrows. (B) Manual quantification of CD34+ blood vessels. Results were taken from a minimum of 27 fields of view and were statistically analyzed by unpaired t-test with Welch's correction, where **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001. (C) A subsequent cell count and mammosphere assay of cells extracted from excised tumors at experimental end point showed a significant increase in cell count and MFE after delivery of siFKBPL compared with delivery of siNT, and a significant decrease in cell count after delivery of pFKBPL compared with delivery of pEV; MFE was unable to be determined for pFKBPL due to insufficient cell numbers.

pEV: Empty vector plasmid; pFKBPL: FK506-binding protein like – FKBPL gene, delivered using RALA; SD: Standard deviation; SE: Standard error; siFKBPL: FKBPL siRNA; siNT: Nontargeting siRNA.

(C) Data taken from [23].

Samples from the same tumors were subsequently processed for mammosphere assay. The results from this assay were previously published in McClements et al. 2013 [23] in graphical format, where we clearly demonstrate that FKBPL's ability to target CD44 leads to a reduction in stemness by targeting CD44+ breast cancer stem cells. As shown in Figure 4C, FKBPL knockdown resulted in a significant increase (56% increase) in mammosphere forming efficiency compared with control. This indicates that knockdown of endogenous FKBPL can promote stemness within tumors, supporting our previously published work, where complementing FKBPL levels with a therapeutic peptide, AD-01, inhibits stemness [23]. Therefore, despite the RALA-siFKBPL showing no effect on reducing survival or increasing tumor growth, there was a more subtle effect that was observed by an increase in blood vessel formation, an increase in viable tumor cells in excised tumor and an increase in mammosphere forming efficiency after this treatment.

Discussion

Condensation of nucleic acid in RALA-siFKBPL and RALA-pFKBPL complexes starts to occur from N:P 3 upward and the optimal N:P ratio was taken to be 10. This confirms previous studies that have characterized RALA using the reporter genes, GFP and Luciferase [14]. TEM and size analysis revealed that both sets of complexes were <100 nm with a narrow size distribution and there was no evidence of aggregation. These biophysical characteristics are indicative of highly stable nanoparticles [25] and are within the ideal size for receptor mediated endocytosis [26,27]. A zeta potential greater than +10 mV as seen in this study provides sufficient electrostatic interaction to facilitate cellular endocytosis via the clathrin pathway. If the charge is strongly negative, particles will be scavenged by phagocytosis via the macrophage polyanion receptor [25]. If the charge is positive, but low, the complexes would aggregate as there would not be adequate electrostatic repulsion. Conversely, if the charge is greater than +25 mV, there is the possibility that complexes will aggregate with negatively charged serum proteins, causing an immune response and toxicity [3,28–30]. The RALA complexes tested were stable in serum for at least 6 h, and DNA remained intact after decomplexation. Previous studies have indicated that trehalose is an ideal cryoprotectant for the RALA peptide and so further lyophilization studies could provide a solution to potential scale up issues with this therapeutic [25].

Transfection of ZR-75–1 cells indicated that RALA could prove to be an effective delivery agent for nucleic acids. FKBPL knockdown and overexpression was observed from 0.125 µg siFKBPL and 1 µg pFKBPL, respectively, when delivered with RALA. This suggests RALA complexes can be trafficked to both the cytoplasm and the nucleus; necessary for delivery of siRNA and DNA, respectively [7]. Nucleic acid delivery was more efficient with Oligofectamine and Lipofectamine 2000 than with RALA. However, Oligofectamine and Lipofectamine 2000 are known to be toxic to cells and this was indeed the case in this study which contrasted with the RALA delivery vehicle only (Figure 2D) [28]. Toxicity can be alleviated with cationic peptides that have a low-molecular weight (≤30 residues) and interspersed charged amino acids that are localized on the structure [31]. The RALA cationic peptide contains 7 arginine residues, and is within the ideal range of 6–12 arginine residues to reduce toxicity while maintaining critical membrane penetrating potential [32].

Moreover, the effects of RALA are more promising, compared with previously designed peptide delivery systems such as KALA, the broad pH activity of which [12] could cause toxicity. The McCarthy group have also demonstrated that RALA is nonimmunogenic, even after repeated administration; making RALA a promising in vivo delivery vehicle [14]. It also has the advantage that it has demonstrated efficacy to deliver both DNA and RNA, so only one transfection agent is necessary.

Significant in vivo gene transfer using peptide vectors was first shown by Rittner et al.; toxicity was observed but to a lesser extent than lipid and polymer systems [33], in line with our findings. In vivo intratumoral administration of RALA-siFKBPL complexes did not affect ZR-75–1 tumor growth rate. However, immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining for FKBPL revealed a reduction in FKBPL staining in treated regions compared with control, indicating that knockdown had been achieved. It is likely that the effect of siFKBPL knockdown on tumor growth could not be detected in this tumor model as it is a fast growing tumor, although another possibility is that because siRNA is trafficked to the cytoplasm, it does not stay in the cell long enough to exhibit its full effects. This could be rectified by delivery of shRNA which would be trafficked to the nucleus, so having a lower rate of degradation and turnover, and remaining in the cell for at least 7 days. However, the possible liver toxicity observed following high levels of shRNA would have to be balanced with maintenance of knockdown [34]. shRNA has already shown promise as a safe and efficacious cancer vaccine by targeting furin, and so reducing the expression of several tumor-related genes such as TGF-β [35]. In vivo intratumoral administration of RALA-pFKBPL complexes significantly prolonged survival and reduced tumor growth rate as predicted in comparison to our previous data using MDA-MB-231 xenografts, where we demonstrated inhibition of tumor growth due to FKBPL-mediated inhibition of angiogenesis [20]. However, the effect of overexpression in this ER-dependant breast xenograft, ZR-75–1 has not been reported. This is important considering that FKBPL regulates ER signaling, sensitizes cells to tamoxifen and mediates effects on cell growth via its interaction with HSP90-p21-ER complex [17]. IHC staining for FKBPL and H&E revealed tumor necrosis at the experimental end point. This is consistent with the antiangiogenic effects of FKBPL overexpression reported using a MDA-MB-231 (A3) xenograft model, stably overexpressing FKBPL [22], where intravital microscopy demonstrated inhibitory effects on MVD. Here, staining of endothelial cells with an antibody detecting CD34 was used to quantify blood vessels [36,37] to detect any changes in MVD, which may have taken place after delivery of RALA complexes. Quantification of MVD by an independent assessor demonstrated a significant 38% increase in vessel numbers in tumors treated with siFKBPL, and a significant 53% decrease in vessel numbers in tumors treated with FKBPL-overexpressing plasmid. This further supports the role of FKBPL in angiogenesis; reduced levels of this antiangiogenic protein increase the number of blood vessels, in other words, angiogenesis in the tumors, while FKBPL overexpression reduces blood vessel number. In summary, we therefore hypothesize that the pFKBPL-mediated inhibition of tumor growth is likely to be due to inhibition of tumor angiogenesis and possibly due to a direct effect on cell proliferation through stabilization of p21 as we have previously reported [19]. The latter is yet to be established, however, the number of live ZR-75–1 cells ex vivo was higher in the siFKBPL group suggesting that endogenous FKBPL behaves as a tumor-suppressor gene inhibiting tumor growth and proliferation, supporting our hypothesis.

Finally, since we have previously demonstrated a role for FKBPL in modulating CD44+ breast cancer stem cells [23], we also assessed ZR-75–1 tumors for stemness in this study, using an ex vivo mammosphere assay. We observed a very significant 56% increase in mammosphere forming efficiency when siFKBPL was delivered compared with nontargeting control. This further supports a role for endogenous FKBPL in inhibiting breast cancer stem cell signaling [23]. Unfortunately, the mammosphere forming efficiency of cells derived from ZR-75–1 tumor xenografts treated with FKBPL overexpressing plasmid could not be assessed due to the extent of necrosis in these tumors, meaning that there was insufficient tumor tissue to process.

Conclusion

This is the first paper from our group that demonstrates the therapeutic application of the RALA system by delivering FKBPL DNA and FKBPL RNAi. This is also the first report of RALA delivering RNAi and follows on from our original RALA paper [14]. We present considerable data demonstrating that RALA successfully delivered both pFKBPL and siFKBPL in vitro and in vivo with minimal toxicity. We also highlight an alternative therapeutic approach to harnessing FKBPL's antiangiogenic and antistemness activity. As such, we believe the data presented here will revolutionize the possibilities with FKBPL as a gene therapy for cancer.

Future perspective

While we have clearly demonstrated efficacy using this novel RALA gene delivery system, future studies could investigate conjugation of a nuclear localization signal (NLS) to aid nuclear trafficking of DNA delivery to the nucleus, or the addition of a scaffold matrix attachment region (S/MAR) within the plasmid to increase the therapeutic efficacy. This could possibly increase transport along microtubules, through the nuclear pore via the importin pathway [38]. An S/MAR is AT-rich, and is found between genes that attach chromosomal DNA to the nuclear scaffold, ensuring that DNA remains lightly wound and active [39]. These techniques could be used for both overexpression and knockdown strategies with shRNA. Knockdown of FKBPL using RALA siFKBPL could be applied in therapeutic strategies to induce angiogenesis in conditions such as wound healing, while systemic delivery of pFKBPL could exploit FKBPL's antiangiogenic activity for the treatment of cancer. A candidate peptide (ALM201) based on the antiangiogenic domain of FKBPL and developed by Almac Discovery, and has entered Phase I/II clinical trials in ovarian cancer patients, with preclinical data indicating it is nontoxic. However, the short half-life of peptides suggests that RALA-mediated delivery of pFKBPL presents a highly attractive therapeutic option, with a number of exciting clinical opportunities also available for RALA-mediated delivery of siFKBPL.

Executive summary.

RALA

Is an 30-amino acid arginine-rich peptide.

It can condense nucleic acids into nanoparticles.

RALA has increased α-helicity at lower pH, facilitating disruption of endosomes and release of the cargo.

FKBPL

Is a potent secreted antiangiogenic protein that inhibits endothelial cell migration, regulates intracellular response to endocrine therapy through associated with ER and p21 and is therefore a potent anticancer agent and an independent prognostic marker to breast cancer survival.

For the first time, we investigate the delivery of both plasmid FKBPL and RNAi FKBPL siRNA (siFKBPL) with the RALA peptide.

Key findings

RALA/pFKBPL and RALA/siFKBPL formed positively charged size suitable nanoparticles <200 nm that were stable in the presence of serum.

RALA/siFKBPL was capable of downregulating FKBPL, while RALA/pFKBPL upregulated FKBPL.

Cells transfected with RALA nanoparticles had a higher viability than both Lipofectamine® and Oligofectamine®.

Delivery of RALA/pFKBPL to breast tumors in vivo, resulted in an increase in FKBPL staining in the tumor tissue, a decrease in angiogenesis and therefore significantly prolonged survival in ZR-75–1.

RALA/siFKBPL had did not affect ZR-75–1 tumor growth rate in vivo, but there was a reduction in FKBPL staining in the tumor tissue and an associated increase in angiogenesis.

There was a significant increase in the population of breast cancer stem cells when siFKBPL was delivered, consistent with the role of this protein in controlling stemness.

Conclusions

RALA is an effective delivery system for both FKBPL DNA and RNAi.

Future effects of downregulation of siFKBPL could be examined with longer-acting shFKBPL.

RALA/pFKBPL significantly prolongs survival in vivo.

pFKBPL reduction of tumor growth is most likely due to inhibition of angiogenesis and/or through stabilization of p21. Future studies will confirm this.

The increase in the proportion of cancer stem cells following FKBPL knockdown provides further evidence for FKBPL's role in cancer stem cell signaling.

Given the short half-life of the FKBPL peptide, the use of FKBPL nucleic acids presents a number of therapeutic opportunities.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff at the Biological Resource Unit (BRU), QUB, for their help and support for all in vivo experiments, and The Northern Ireland – Molecular Pathology Laboratory (NI–MPL), QUB for their help with the processing and scanning of tissue sections.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This project was supported through a BBSRC grant awarded to T Robson (BB/I006958/1) covering salary for A Yakkundi. R Bennett was supported by Department of Employment and Learning PhD studentship. NI–MPL is supported by Cancer Research UK, the Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre Network and the Friends of the Cancer Centre. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. In addition, for investigations involving human subjects, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.Rana TM. Illuminating the silence: understanding the structure and function of small RNAs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:23–36. doi: 10.1038/nrm2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCrudden CM, McCarthy HO. Bioinspired delivery systems. In: Martin F, editor. Gene Therapy – Tools and Potential Applications. InTech; 2013. ISBN: 978–953–51–1014–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCarthy HO, Zholobenko AV, Wang Y, et al. Evaluation of a multi-functional nanocarrier for targeted breast cancer iNOS gene therapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2011;405:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li W, Nicol F, Szoka FC, Jr, et al. GALA: a designed synthetic pH-responsive amphipathic peptide with applications in drug and gene delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2004;56:967–985. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Explains how the amphipathic peptides were designed and function.

- 5.Yang J, Liu H, Zhang X. Design, preparation and application of nucleic acid delivery carriers. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014;32(4):804–817. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noguchi P. Risks and benefits of gene therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:193–194. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp020184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao X, Kim KS, Liu D. Nonviral gene delivery: what we know and what is next. AAPS J. 2007;9:E92–E104. doi: 10.1208/aapsj0901009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoo JW, Irvine DJ, Discher DE, Mitragotri S. Bio-inspired, bioengineered and biomimetic drug delivery carriers. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2011;10:521–535. doi: 10.1038/nrd3499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatakeyama H, Akita H, Harashima H. A multifunctional envelope type nano device (MEND) for gene delivery to tumours based on the EPR effect: a strategy for overcoming the PEG dilemma. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2011;63:152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karjoo Z, McCarthy HO, Patel P, Nouri FS, Hatefi A. Systematic engineering of uniform, highly efficient, targeted and shielded viral-mimetic nanoparticles. Small. 2013;9:2774–2783. doi: 10.1002/smll.201300077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nouri FS, Wang X, Dorrani M, Karjoo Z, Hatefi A. A recombinant biopolymeric platform for reliable evaluation of the activity of pH-responsive amphiphile fusogenic peptides. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14:2033–40. doi: 10.1021/bm400380s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wyman TB, Nicol F, Zelphati O, Scaria PV, Plank C, Szoka FC., Jr Design, synthesis, and characterization of a cationic peptide that binds to nucleic acids and permeabilizes bilayers. Biochemistry. 1997;36:3008–3017. doi: 10.1021/bi9618474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • First paper to synthesize and characterize the KALA peptide.

- 13.Fominaya J, Gasset M, García R, Roncal F, Albar JP, Bernad A. An optimized amphiphilic cationic peptide as an efficient non-viral gene delivery vector. J. Gene Med. 2000;2:455–464. doi: 10.1002/1521-2254(200011/12)2:6<455::AID-JGM145>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCarthy HO, McCaffrey J, McCrudden CM, et al. Development and characterisation of self-assembling nanoparticles using a bio-inspired amphipathic peptide for gene delivery. J. Control. Release. 2014;189:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Explains the synthesis of the RALA peptide used in this study and explains the mechanism of action.

- 15.Galat A. Functional diversity and pharmacological profiles of the FKBPs and their complexes with small natural ligands. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013;70(18):3243–3275. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1206-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jascur T, Brickner H, Salles-Passador I, et al. Regulation of p21(WAF1/CIP1) stability by WISp39, a Hsp90 binding TPR protein. Mol. Cell. 2005;17:237–249. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKeen HD, McAlpine K, Valentine A, et al. A novel FK506-like binding protein interacts with the glucocorticoid receptor and regulates steroid receptor signaling. Endocrinology. 2008;149:5724–5734. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sunnotel O, Hiripi L, Lagan K, et al. Alterations in the steroid hormone receptor co-chaperone FKBPL are associated with male infertility: a case-control study. Repro. Biol. Endocrinol. 2010:8–22. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-8-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKeen HD, Byrne C, Jithesh PV, et al. FKBPL regulates estrogen receptor signaling and determines response to endocrine therapy. Cancer Res. 2010;7:1090–1100. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valentine A, O'Rourke M, Yakkundi A, et al. FKBPL and Peptide derivatives: FKBPL and peptide derivatives: novel biological agents that inhibit angiogenesis by a CD44-dependent mechanism. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;17(5):1044–1056. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Demonstrates the antiangiogenic effects of FKBPL.

- 21.Yakkundi A, Bennett R, Hernàndez-Negrete I, et al. FKBPL is a critical antiangiogenic regulator of developmental and pathological angiogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2015;35(4):845–854. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Endogenous FKBPL is a potent antiangiogenic and has a crucial role in development.

- 22.Yakkundi A, McCallum L, O'Kane A, et al. The anti-migratory effects of FKBPL and its peptide derivative, AD-01: regulation of CD44 and the cytoskeletal pathway. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e55075. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McClements L, Yakkundi A, Papaspyropoulos A, et al. Targeting treatment resistant breast cancer stem cells with FKBPL and its peptide derivative, AD-01, via the CD44 pathway. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;19(14):3881–3893. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• FKBPL-based therapy also targets treatment-resistant cancer stem cells.

- 24.Nelson L, McKeen HD, Marshall A, et al. Evaluating the prognostic potential of FKBPL: a novel breast cancer biomarker. Oncotarget. 2015;6(14):12209–12223. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• FKBPL is prognostic and could act as a predictive marker of response to an FKBPL-based therapy.

- 25.Davis ME. Non-viral gene delivery systems. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2002;13:128–131. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(02)00294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ansar M, Serrano D, Papademetriou I, Bhowmick TK, Muro S. Biological functionalization of drug delivery carriers to bypass size restrictions of receptor-mediated endocytosis independently from receptor targeting. ACS Nano. 2013;7:10597–10611. doi: 10.1021/nn404719c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rejman J, Oberle V, Zuhorn IS, Hoekstra D. Size-dependent internalization of particles via the pathways of clathrin- and caveolae-mediated endocytosis. Biochem. J. 2004;377:159–169. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akhtar S, Benter IF. Nonviral delivery of synthetic siRNAs in vivo . J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:3623–3632. doi: 10.1172/JCI33494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morris MC, Chaloin L, Heitz F, Divita G. Translocating peptides and proteins and their use for gene delivery. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2000;11:461–466. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(00)00128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang JP, Huang L. Overcoming the inhibitory effect of serum on lipofection by increasing the charge ratio of cationic liposome to DNA. Gene Ther. 1997;9:950–960. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hwang SJ, Bellocq NC, Davis ME. Effects of structure of beta-cyclodextrin-containing polymers on gene delivery. Bioconjug. Chem. 2001;12:280–290. doi: 10.1021/bc0001084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakase I, Tanaka G, Futaki S. Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) as a vector for the delivery of siRNAs into cells. Mol. Biosyst. 2013;9:855–861. doi: 10.1039/c2mb25467k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rittner K, Benavente A, Bompard-Sorlet A, et al. New basic membrane-destabilizing peptides for plasmid-based gene delivery in vitro and in vivo . Mol. Ther. 2002;5:104–114. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grimm D, Streetz KL, Jopling CL, et al. Fatality in mice due to oversaturation of cellular microRNA/short hairpin RNA pathways. Nature. 2006;441:537–541. doi: 10.1038/nature04791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Senzer N, Barve M, Nemunaitis J, et al. Long term follow up: Phase I trial of “bi-shRNA furin/GMCSF DNA/autologous tumor cell” immunotherapy (FANG™) in advanced cancer. J. Vaccines Vaccin. 2013;4:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simmons DL, Satterthwaite AB, Tenen DB, Seed B. Molecular cloning of a cDNA encoding CD34, a sialomucin of human hematopoietic stem cells. J. Immunol. 1992;148:267–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin G, Finger E, Gutierrez-Ramos JC. Expression of CD34 in endothelial cells, hematopoietic progenitors and nervous cells in fetal and adult mouse tissues. Eur. J. Immunol. 1995;25:1508–1516. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCarthy HO, Wang Y, Mangipudi SS, Hatefi A. Advances with the use of bio-inspired vectors towards creation of artificial viruses. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2010;7:497–512. doi: 10.1517/17425240903579989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gill DR, Pringle IA, Hyde SC. Progress and prospects: the design and production of plasmid vectors. Gene Ther. 2009;16:165–171. doi: 10.1038/gt.2008.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]