Abstract

Introduction:

The objective of this analysis is to identify, assess the quality and summarize the findings of peer-reviewed articles that used data from the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect (CIS) published since November 2011 and data from provincial oversamples of the CIS as well as to illustrate evolving uses of these datasets.

Methods:

Articles were identified from the Public Health Agency of Canada’s data request records tracking access to CIS data and publications produced from that data. At least two raters independently reviewed and appraised the quality of each article.

Results:

A total of 32 articles were included. Common strengths of articles included clearly stated research aims, appropriate control variables and analyses, sufficient sample sizes, appropriate conclusions and relevance to practice or policy. Common problem areas of articles included unclear definitions for variables and inclusion criteria of cases. Articles frequently measured the associations between maltreatment, child, caregiver, household and agency/referral characteristics and investigative outcomes such as opening cases for ongoing services and placement.

Conclusion:

Articles using CIS data were rated positively on most quality indicators. Researchers have recently focussed on inadequately studied categories of maltreatment (exposure to intimate partner violence [IPV]), neglect and emotional maltreatment) and examined factors specific to First Nations children. Data from the CIS oversamples have been underutilized. The use of multivariate analysis techniques has increased.

Keywords: child maltreatment, child abuse, public health surveillance

Key findings

In this review of 32 peer-reviewed published articles, the majority were of high quality with clearly stated research aims, appropriate control variables, appropriate analyses, sufficient sample sizes, appropriate conclusions and relevance to practice or policy.

Researchers using CIS data have recently focussed on inadequately studied categories of maltreatment, including exposure to intimate partner violence, neglect and emotional maltreatment, and have examined factors specific to First Nations children.

The use of complex multivariate analysis methods has recently increased.

Introduction

The Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect (CIS) has been completed for three cycles—1998,1 2003,2 and 20083—and has provided a wealth of information on investigations of reported child abuse and neglect nationwide.4 The CIS collects data about children who have been reported to child welfare agencies because of allegations of maltreatment.1-3 CIS data can be used as a source of information about children who have experienced alleged and substantiated neglect, exposure to intimate partner violence (IPV), emotional (or psychological) maltreatment, physical abuse and/or sexual abuse. It includes information on the characteristics of the child, caregiver, household and investigating agency as well as short-term service outcomes such as placement. CIS data is used by senior child welfare decision makers to help determine resource allocation, identify at-risk populations, understand reported maltreatment trends, validate findings at individual agencies and direct changes in practice.4 It is also accessed by a broad range of experts in clinical medicine, public health, social work, law and justice, education, sports, recreation, and faith-based groups.5

The CIS–2008: Major Findings report3 details the breadth and scope of the CIS. Each cycle of the CIS contains information on a large sample of maltreatment cases reported to child welfare agencies and opened for investigation. Child welfare workers in selected agencies across Canada completed the CIS survey for each investigation they completed within a three-month data collection period in the fall of the survey year. The participating child welfare workers were given definitions of maltreatment to ensure consistency. A multistage stratified clustered sample from all provinces and territories that included mainstream and First Nations agencies was used. Some provinces and territories provided additional funding to the CIS to obtain data (i.e. oversample) from their respective jurisdictions.

The CIS–2008 study differs from the CIS–1998 and 2003 waves because investigations of risk of future maltreatment were tracked separately from investigations of allegations of specific maltreatment. In addition, definitions of maltreatment have evolved over time. For example, the CIS–2008 tracked three subtypes of exposure to IPV: indirect exposure to physical violence, direct exposure to physical violence and exposure to emotional violence.6 Previously, the CIS captured IPV as a subtype of emotional maltreatment. Differences between provincial and territorial legislation and changes in detection, reporting and investigation procedures over time also influence the CIS findings. This means that changes in estimates may not represent actual changes in the occurrence of maltreatment.

An earlier review7 summarized and critically assessed 37 peer-reviewed analyses of CIS data published before November 2011. Roughly half of the sources were descriptive and half were multivariate. The review assessed the quality of the articles and found the multivariate articles to be generally of good quality; stronger evidence was provided for their objectives compared to the descriptive articles. The review recommended that future research use clear directional hypotheses and multivariate techniques.7

Considering the cyclical nature of the CIS, and especially because the Public Health Agency of Canada decided not to collect data in 2013, this is an opportune time to update the findings from the previous review and ask questions about the relevance of the CIS in terms of policy and practice. Only 3 of the articles in the previous review7 utilized data from CIS–2008. In addition, the information was limited because the data had only recently been released. Furthermore, the previous review7 was critiqued for not including results stemming from oversampling provinces. As more articles utilizing these and earlier waves of data have since been published, our review focusses on CIS-related literature published after November 2011 and analyses of CIS oversample data published at any time.

Knowledge users (decision makers and policy makers) find effectively summarized research useful. The surveillance reports stemming from the CIS have been used as a reference to obtain information quickly.4 Similarly, we hope that this review will provide a quick reference for topics that have been analysed using the CIS data as well as on the quality of these articles. This review may also inspire researchers to further knowledge about child maltreatment and the responses of child welfare agencies. The information may also serve to improve the CIS as a surveillance tool by identifying some gaps in data collection and analysis. Lastly, the information has the potential to increase awareness of this important public health issue.

The specific objectives of this review were to

identify and retrieve all peer-reviewed studies published between November 2011 and the present day that used CIS data or CIS provincial and territorial oversampling data collected since the inception of the study;

assess the quality of those studies;

summarize the findings of those studies; and

illustrate the evolving uses of CIS data.

Methods

We included original research published in peer-reviewed journals as these can be expected to be of the highest quality and include sufficient information on methods and analyses to assess quality. Other sources, such as book chapters and presentations, may not follow a standardized format of presenting information or have specific objectives or hypotheses to test. As such, our quality assessment tool would not be suited to them. In addition, because the review is restricted to peer-reviewed journal articles, interested readers should find it easier to locate and access our primary sources. Table 1 lists all survey waves of the CIS, jurisdictions that oversampled and First Nations samples.

TABLE 1. CIS, CIS oversamples and First Nations studies.

| Population | Cycles |

|---|---|

| Canada | 1998, 2003, 2008 |

| British Columbia | 1998, 2008 |

| Alberta | 2003, 2008, 2013 |

| Saskatchewan | 2008 |

| Ontario | 1993, 1998, 2003, 2008, 2013 |

| Quebec | 1998, 2008, 2014 |

| Northwest Territories | 2003 |

| First Nations | 1998, 2003, 2008 |

Articles were identified through the Public Health Agency of Canada data request records. In addition, we conducted a search for articles published by authors from the CIS research team to ensure completeness. As members of the research team did not need to request permission to use CIS data, their publications would not be captured in data request records.

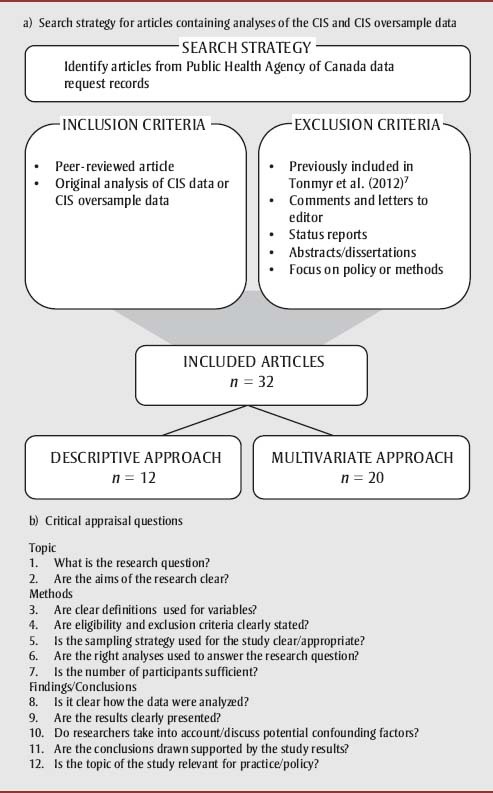

Figure 1 summarizes the article selection strategy (source, inclusion and exclusion criteria) and presents the list of quality assessment questions. The quality assessment questions were the same as those used in the previous review of CIS data7 (discussed above). Two raters independently reviewed each article for inclusion and completed the quality appraisal tool for each. Discrepancies in ratings of the articles were discussed until consensus was reached or after discussion with a third rater. Raters did not review articles they had authored.

Figure 1. Search strategy and article appraisal.

Results

A total of 32 studies were identified for inclusion. Of those, 20 were considered multivariate and 12 descriptive; 24 used national level data and 8 provincial or territorial level data; 5 analyzed data from Quebec and 3 from Ontario; 1 used data from the First Nations component of the CIS–2008.

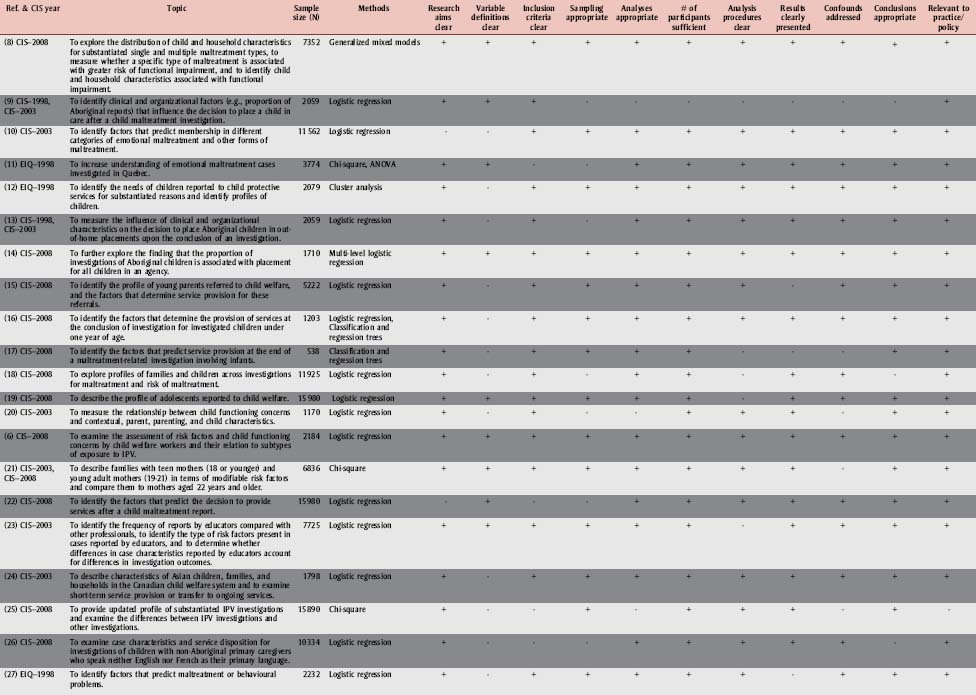

Table 2 shows the objectives, methods and quality assessment results of the included studies. Ninety-one percent of authors clearly described their research aims. In contrast, only 40% clearly defined all variables. Seventy-two percent of the studies provided clear inclusion criteria for cases and 72% described clear and appropriate sampling methods. Seventy-eight percent of analyses were considered appropriate to the authors’ research questions. The number of participants was considered sufficient 91% of the time. Analytical procedures and results were usually clearly explained (72%) and presented (75%). Eighty-one percent of conclusions were considered appropriate, and all but one study was judged to have been about a topic with clear applications for practice or policy.

TABLE 2. Characteristics of articles analyzing CIS and CIS oversample data.

|

Abbreviations:CIS, Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect; EIQ, Quebec Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect; FNCIS, First Naotins Component of the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect; IPV, intimate partner violence; OIS, Ontario Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect.

The objectives of 28% of the articles were to do with particular types of maltreatment. Two were about neglect, three about emotional maltreatment, and two about exposure to IPV. One study was about exposure to IPV, hitting or neglect as sole concerns for investigation. None of the studies had objectives exclusively to do with physical abuse. One paper examined the frequency of joint police and child welfare investigations of sexual abuse cases compared with other maltreatment cases.

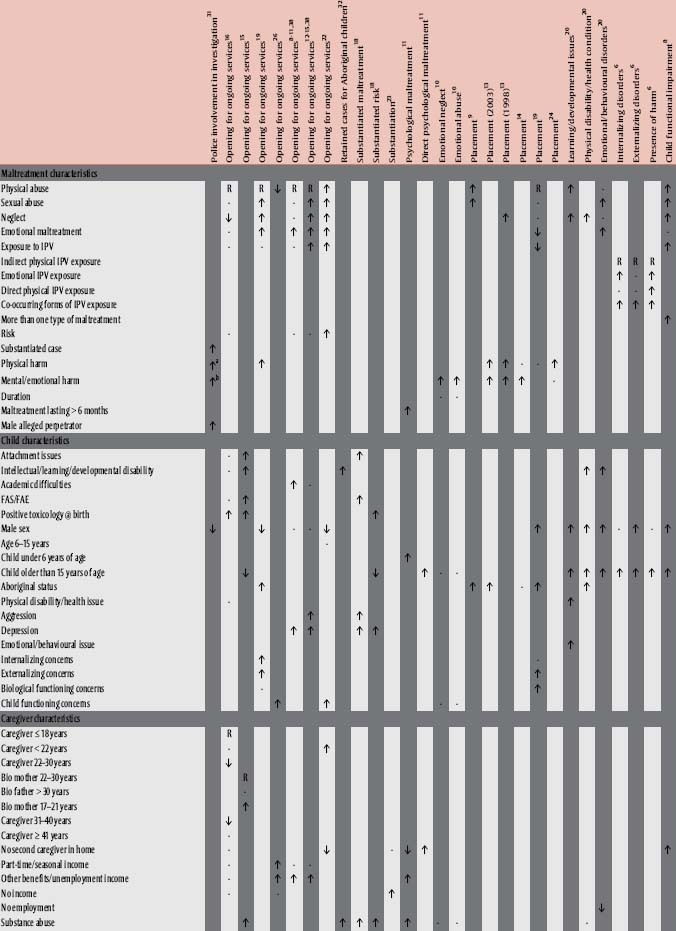

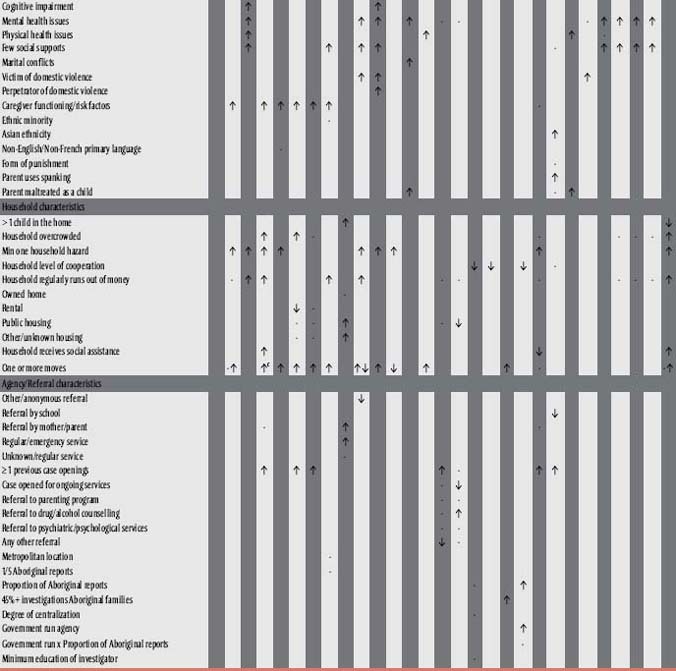

Table 3 summarizes the associations between independent, control and dependent variables measured in the articles presenting multivariate analyses. In this review, we define multivariate analyses as those that simultaneously measure multiple independent and/or dependent variables. For articles that described multiple models, only the final model is included for each dependent variable tested.

TABLE 3. Associations between independent, control, and dependent variables in the articles presenting multivariate analyses.

|

Abbreviations: FAE, fetal alcohol effects; FAS, fetal alcohol syndrome; IPV, intimate partner violence; R, reference group; -, no statistically significant relationship (p > .05); ↓, statistically significant negative relationship (p < .05); , statistically significant positive relationship (p < .05).

Note: Where more than one symbol appears in a cell, that article featured finer grained categories of the variable in question which have been collapsed forocncision and those finer categories had different relationships with the dependent variable.

aThis variable combined physical and emotional harm.

bThis variable combined physical and emotional harm.

cThis variable was two or more moves.

Independent and control variables are grouped into five categories: maltreatment characteristics, child characteristics, caregiver characteristics, household characteristics and agency/referral characteristics. One article that used multivariate techniques was not included in the table because the analyses were classification and regression trees that could not be easily summarized in the structure of the table.

Most analyses that used maltreatment types (i.e. physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, emotional maltreatment and exposure to IPV) as independent variables included more than one maltreatment type. One study included only maltreatment variables representing different types of exposure to IPV, one included only physical abuse and two included only neglect. In addition, two studies considered emotional maltreatment as a dependent variable.

Researchers frequently used child age and sex as independent or control child-related variables. They tended to use some but not all the variables associated with child functioning concerns in their models, sometimes grouping all child functioning concerns together to create one dichotomous variable representing the presence of any of these concerns. The child functioning concerns span physical, mental, behavioural and developmental problems. Caregiver risk factors, especially substance abuse, mental health issues and lack of social support, were the most frequently used caregiver variables. Household hazards, overcrowding, household frequently runs out of money and frequency of moves were the most commonly used household variables. Finally, one or more case openings and a mother or parent as referral source were the most studied agency/referral variables.

The most commonly studied type of dependent variable, used in six articles, was the opening of a case for ongoing services. Researchers measured the associations of a variety of independent and control variables to do with maltreatment and child, caregiver, household and agency/referral characteristics with this outcome variable. The second most commonly studied outcome variable, used in four articles, was placement in out-of-home care. These articles included numerous variables to do with maltreatment, child, household and agency/referral characteristics. However, only two of four articles were about caregiver risk factors and those used few variables from the category. Other outcome variables that were studied, each in three or fewer articles, included retained cases for Aboriginal children, substantiated maltreatment, substantiated risk of maltreatment, emotional maltreatment, harm to the child, and child functioning concern variables including learning/developmental issues, physical disability/health conditions, emotional/behavioural problems, internalizing disorders, externalizing disorders, child functional impairment and police involvement in investigations.

Discussion

Our review summarized findings from the 32 identified articles on the quality and the relationships between variables in peer-reviewed journal articles using CIS data published since November 2011 and CIS oversample data. The majority of the reviewed articles had clearly stated research aims, used appropriate control variables (where studies were multivariate rather than descriptive), conducted appropriate analyses with sufficient sample sizes, had appropriate conclusions and were relevant to practice or policy.

The majority of the studies did not clearly define variables or provide rationales for the inclusion of the variables within analyses. Because most studies included a large number of variables, this may have been due to word limits imposed by publishers rather than a lack of planned rationale by the researchers. Often articles were judged to have unclear inclusion criteria and sampling methods when the authors had not explained how they selected cases for analysis from the full CIS sample and had provided only an overview of the CIS sampling methods. When the number of participants was considered insufficient, the researchers had usually used smaller subsamples of CIS cases for analysis. One strength of the CIS is that the sample size is large enough to conduct complex multivariate analyses, which is likely why this quality indicator was almost always rated positively. Analyses were frequently appropriate and results clearly presented; however, when they were not, it was usually because authors did not describe which analyses they were performing or did not clearly label tables. When analyses were gauged to be inappropriate to the research question, it was often because researchers used univariate analyses when multivariate approaches would have better addressed their research objectives. Studies that were multivariate in nature nearly always used appropriate control variables to account for potential confounding. Other studies used descriptive analyses to explore new topics, so that hypotheses could be generated and more sophisticated techniques could be used in future research. Conclusions were judged to be inappropriate when they extended beyond the scope of the analyses, such as when authors used causal language to describe an association. When an article was judged to be limited in relevance to practice or policy it was because the application of the findings was not clearly expressed, not necessarily because it had no potential application.

Regarding the associations between variables, some articles explored issues to do with substantiating maltreatment and service provision across the full sample of specific CIS waves or provincial subsamples, whereas other articles were concerned with analyses of subgroups of investigations classified by specific characteristics of children and families or specific characteristics of the investigated maltreatment or risk of maltreatment. Analyses tended to include child maltreatment types as variables when predicting opening for services, placement and child functioning concerns or harm but not when predicting substantiation. It is interesting that presence of harm was also not used to predict substantiation, although observable harm as evidence of maltreatment would presumably make maltreatment allegations easier for workers to substantiate.

This review has highlighted new areas relevant to policy. The multiple disciplines involved in child maltreatment were addressed in an article describing teachers’ reporting practices and the response to these by child welfare services.23 This expands upon our knowledge of the reporting practices of different disciplines, in the same way that a similar article in the previous review described health care professionals’ reporting to child welfare agencies.39 In addition, another article was about variables associated with joint police and child welfare worker investigations.31

Although changes to the CIS questionnaire are kept to a minimum between cycles, changes have been made to capture changes in practice. For example, CIS–2008 was changed to collect information on risk-only investigations.3 One of the articles focussed on untangling risk of future maltreatment from past events of maltreatment.18

Uses of the CIS data have evolved over time. In contrast to the previous review,7 in which 54% of studies were multivariate, 62.5% of the studies included in this review used multivariate approaches. Despite the increase in use of multivariate techniques, the objectives of most of the included studies did not include clear directional hypotheses as recommended.

The previous review7 found that physical abuse was the most frequently studied category of maltreatment as a main focus and exposure to IPV was the least. In the present review, nearly all the multivariate articles included either all forms of maltreatment or no forms of maltreatment as independent or control variables. The finding that more papers have focussed on exposure to IPV, emotional maltreatment and neglect is important for policy makers because neglect and exposure to IPV were the first and second most substantiated forms of maltreatment in the CIS–2008 and emotional maltreatment was the fourth.3 The three articles that focussed on neglect identified risk factors,29,33 found a low presence of harm29 and found that fathers are less likely to be present in cases of neglect.28 The three articles that focussed on emotional maltreatment suggested that the increased specificity of definitions in the CIS–2008 helped differentiate between the occurrence and the risk of emotional maltreatment,34 demonstrated that emotional maltreatment often co-occurs with other forms of maltreatment11 and demonstrated that substantiated cases of single form emotional maltreatment are associated with more severe emotional impacts than other forms of maltreatment.10 The three articles that focussed on exposure to IPV described the characteristics of cases of exposure to IPV in single form, exposure to IPV and other maltreatment and exposure to other maltreatment;25 suggested that exposure to different subtypes of IPV may have different associations with child functioning;6 and suggested that investigations of exposure to IPV or hitting only had lower- risk factors and were less likely to remain open compared with other investigations.33

Another notable topic for recent uses of CIS data was investigations involving First Nations children. Five articles explored topics specifically related to First Nations children, including factors influencing overrepresentation at the investigation stage,30 placement decisions9,13,14 and differences from reports on non-Aboriginal children.32 Compared to investigations involving non-Aboriginal children, those involving First Nations children had a greater percentage of every caregiver/household risk factor (except health issues) identified by workers.30 This could indicate a need for increased availability of family support services for First Nations families; however, the possibility exists that increased risk factors for these families are due to assessment bias.

Strengths and limitations

This review had a number of strengths. To increase the accuracy of judgments, all articles were reviewed by at least two raters who were not the authors of the article being evaluated. We used a standardized quality assessment tool used in an earlier review of CIS data usage7 to allow our findings to be compared to theirs. We included recent articles and articles based on oversample data, which broadened our scope.

This review also had a number of limitations. It did not include book chapters, theses, dissertations, government or agency reports, or unpublished manuscripts. It is possible that by excluding these sources we are failing to capture the breadth and depth of the research using CIS and CIS oversample data. We chose to exclude these sources, however, because they are not usually peer reviewed. Although oversample data exists for British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan and the Northwest Territories, to our knowledge analyses stemming from these samples have not been published in peer-reviewed journals. Furthermore, we may have missed some articles from oversampling studies because data requests for these are not necessarily made through the Public Health Agency of Canada. In addition, because we only included published articles, our findings may suffer from publication bias (i.e. statistically significant variable associations may be overrepresented because nonsignificant findings are less likely to be published). Note, however, that most of the articles we included also presented findings of nonsignificant associations between variables. We include these nonsignificant findings in Table 3 to demonstrate the lack of relationships between some independent and dependent variables.

There are also limitations to our findings due to the nature of the CIS data. In reviewing these articles some of the limitations of the data were highlighted. Among these limitations are seasonal variations, the lack of independent verification of the data and the use of proxy-informants. In addition, CIS data only includes children who are reported to and investigated by child welfare agencies. Thus, selection bias may impact the population of children identified in the CIS as some children who experience abuse or neglect (for example, children from low-income families) may be more likely to be the subject of child welfare reports than others.3

Furthermore, the criterion validity of the variables within the CIS data may vary. For example, child welfare workers investigating reports of maltreatment or suspected maltreatment can be expected to be better trained and have greater expertise in assessing maltreatment characteristics compared to assessing child and caregiver functioning concern variables as identifying maltreatment would be their primary objective. As previously noted,40 child functioning concerns may be underestimated because they are assessed using a checklist of issues known or suspected by the child welfare worker rather than a standardized systematic assessment, which would not be feasible in the study. In addition, not all child functioning items are relevant to different age groups. Analyses using the full age range of investigated children could have restricted ages of those included in the analyses to account for this; however, many did not.

Finally, all variables were measured at the time of the investigation. As such, it is impossible to know whether child maltreatment preceded child functioning concerns; nor can causality be established. These limitations are important for knowledge users and for researchers. The latter could study ways of further improving the quality of the data by considering the limiting parameters of the study.

Conclusions

This review has described the evolving nature of the application of the CIS and CIS oversample data to answer questions about substantiation, placement, provision of services and the impact of maltreatment on child functioning. It is clear that a multitude of factors determine these outcomes. Researchers using CIS data have recently focussed on categories of maltreatment (exposure to IPV, neglect and emotional maltreatment) that were previously inadequately studied, and examined factors specific to First Nations children.7 This review has highlighted newly investigated areas relevant to policy. It also suggests that data from the CIS oversamples has generally been underutilized in the peer-reviewed literature. In the future, researchers using CIS data may benefit from this analysis as it identified common pitfalls. The summary of research findings may help researchers identify unexplored topics in the CIS. Future research with CIS and CIS oversample data should continue to utilize sophisticated statistical modelling methods to take advantage of the breadth of information available to address research objectives.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Wendy Hovdestad and Dr. Anne-Marie Ugnat for their help in evaluating some of the articles included in the review.

References

- 1.Trocmé N, MacLaurin B, Fallon B, et al. Canadian incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect: Final report. Ottawa (ON): Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trocmé N, Fallon B, MacLaurin B, et al. Canadian incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect – 2003: major findings. Ottawa (ON): Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Public Health Agency of Canada . Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect 2008: Major findings. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tonmyr L, Jack SM, Brooks S, Williams G, Campeau A, Dudding P. Utilisation of the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect in child welfare agencies in Ontario. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2012;33((1)):29–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tonmyr L, Martin WK. How has child maltreatment surveillance data been used in Canada?. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014;1265((1)):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-12-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonzalez A, MacMillan H, Tanaka M, Jack SM, Tonmyr L. Subtypes of exposure to intimate partner violence within a Canadian child welfare sample: Associated risks and child maladjustment. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38:1934–44. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tonmyr L, Ouimet C, Ugnat AM. A review of findings from the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect (CIS). Can J Public Health. 2012;103((2)):103–12. doi: 10.1007/BF03404212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Afifi TO, Taillieu T, Cheung K, Laurence YK, Tonmyr L, Sareen J. Substantiated reports of child maltreatment from the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect (CIS) 2008: examining child and household characteristics and child functional impairment. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60((7)):315–23. doi: 10.1177/070674371506000704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chabot M, Fallon B, Tonmyr L, MacLaurin B, Fluke J, Blackstock C. Exploring alternate specifications to explain agency-level effects in placement decisions regarding aboriginal children: further analysis of the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect Part B. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37:61–76. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chamberland C, Fallon B, Black T, Trocmé N, Chabot M. Correlates of substantiated emotional maltreatment in the second Canadian Incidence Study. J Fam Viol. 2012;27:201–13. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chamberland C, Laporte L, Lavergne C, et al. Psychological maltreatment of children reported to youth protection services. J Emotional Abuse. 2005;5:65–94. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clément M-E, Chamberland C, Tourigny M, Mayer M. Taxinomie des besoins des enfants dont les mauvais traitements ou les troubles de comportement ont été jugés fondés par la direction de la protection de la jeunesse. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33:750–65. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fallon B, Chabot M, Fluke J, Blackstock C, MacLaurin B, Tonmyr L. Placement decisions and disparities among Aboriginal children: further analysis of the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect Part A: comparisons of the 1998 and 2003 surveys. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37:47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fallon B, Chabot M, Fluke J, Blackstock C, Sinha V, Allan K, MacLaurin B. Child Abuse Negl. 2015. Exploring alternate specifications to explain agency-level effects in placement decisions regarding Aboriginal children: further analysis of the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect Part C. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fallon B, Ma J, Black T, Wekerle C. Characteristics of young parents investigated and opened for ongoing services in child welfare. Int J Ment Health Addiction. 2011;9:365–81. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fallon B, Ma J, Allan K, Pillhofer M, Trocmé N, Jud A. Opportunities for prevention and intervention with young children: lessons from the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2013;7:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fallon B, Ma J, Allan K, Trocmé N, Jud A. Child maltreatment-related investigations involving infants: opportunities for resilience?. Int J Child Adolesc Resil. 2013;1:35–47. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fallon B, Trocmé N, MacLaurin B, Sinha V, Black T. Untangling risk of maltreatment from events of maltreatment: An analysis of the 2008 Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect (CIS-2008). Int J Ment Health Addiction. 2011;9:460–79. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fast E, Trocmé N, Fallon B, Ma J. A troubled group? Adolescents in a Canadian child welfare sample. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2014;46:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feldman M, McConnell D, Aunos M. Parental cognitive impairment, mental health, and child outcomes in a child protection population. J Ment Health Res Intellect Disabil. 2012;5((1)):66–90. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hovdestad W, Shields M, Williams G, Tonmyr L. Vulnerability within families headed by teen and young adult mothers investigated by child welfare in Canada. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev. 2015;35((8/9)):143–50. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.35.8/9.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jud A, Fallon B, Trocmé N. Who gets services and who does not? Multi-level approach to the decision for ongoing child welfare or referral to specialized services. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2012;34:983–8. [Google Scholar]

- 23.King CB, Scott KL. Why are suspected cases of child maltreatment referred by educators so often unsubstantiated?. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee B, Rha W, Fallon B. Physical abuse among Asian families in the Canadian child welfare system. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2014;23:532–51. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lefebvre R, Van Wert M, Black T, Fallon B, Trocmé N. A profile of exposure to intimate partner violence investigations in the Canadian child welfare system: an examination using the 2008 Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect (CIS-2008). Int J Child Adolesc Resil. 2013;1((1)):60–73. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma J, Van Wert M, Lee B, Fallon B, Trocmé N. Non-English/non-French speaking caregivers involved with the Canadian child welfare system: Findings from the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect (CIS-2008). Int J Child Adolesc Resil. 2013;1((1)):23–34. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marcotte J, Cloutier R, Tourigny M, et al. Mauvais traitments ou troubles de comportement: Étude des variables qui distinguent l’appartenance à l’um ou l’autre de ces problémati. ques. Intervention. 2003;119:58–70. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayer M, Dufour S, Lavergne C, Girard M, Trocmé N. Structures familiales, paternité et négligence: des réalités à revisiter. Revue de psychoeducation. 2006;35((1)):155–76. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruiz-Casares M, Trocmé N, Fallon B. Supervisory neglect and risk of harm. Evidence from the Canadian child welfare system. Child Abuse Negl. 2012;36:471–80. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sinha V, Trocmé N, Fallon B, MacLaurin B. Understanding the investigation-stage overrepresentation of First Nations children in the child welfare system: an analysis of the First Nations component of the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect 2008. Child Abuse Negl. 2013;37:821–31. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tonmyr L, Gonzalez A. Correlates of joint child welfare and police child sexual abuse investigations: results from the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect-2008. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev. 2015;35((8/9)):130–7. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.35.8/9.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tourigny M, Domond P, Trocmé N, Sioui B, Baril K. Incidence of maltreatment of Aboriginal children reported to youth protection in Quebec: intercultural comparisons. First Peoples Child Family Rev. 2007;3((3)):103–19. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trocmé N, Fallon B, Sinha V, Van Wert M, Kozlowski A, Maclaurin B. Differentiating between child protection and family support in the Canadian child welfare system’s response to intimate partner violence, corporal punishment, and child neglect. Int J Psychol. 2013;48((2)):128–40. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2013.765571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trocmé N, Fallon B, MacLaurin, et al. Shifting definitions of emotional maltreatment: an analysis child welfare investigation laws and practices in Canada. Child Abuse Negl. 2011;35:831–40. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trocmé N, Fallon B, MacLaurin B, Neves T. What is driving increasing child welfare caseloads in Ontario? Analysis of the 1993 and 1998 Ontario Incidence Studies. Child Welfare. 2005;84((3)):341–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trocmé N, Kyte A, Sinha V, Fallon B. Urgent protection versus chronic need: clarifying the dual mandate of child welfare services across Canada. Soc Sci. 2014;3:483–98. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trocmé N, McPhee D, Tam KK. Child abuse and neglect in Ontario: incidence and characteristics. Child Welfare. 1995;74((3)):563–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Wert M, Ma J, Lefebvre R, Fallon B. An examination of delinquency in a national Canadian sample of child maltreatment-related investigations. Int J Child Adolesc Resil. 2013;1((1)):48–59. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tonmyr L, Li A, Williams G, Scott D, Jack S. Patterns of reporting to child protection services in Canada by healthcare and nonhealthcare professionals. Paediatr Child Health. 2010;15((8)):e25–32. doi: 10.1093/pch/15.8.e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nasserie T. The child functioning items in the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect (CIS) Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; 2014. [Google Scholar]