Abstract

The Hippo-YAP pathway has emerged as a major driver of tumorigenesis in many human cancers. YAP is a transcriptional co-activator and while details of YAP regulation are quickly emerging, it remains unknown what downstream targets are critical for YAP’s oncogenic functions. To determine the mechanisms involved and identify disease-relevant targets, we examined YAP’s role in neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) using cell and animal models. We found that YAP function is required for NF2-null Schwann cell survival, proliferation and tumor growth in vivo. Moreover, YAP promotes transcription of several targets including PTGS2, which codes for COX-2, a key enzyme in prostaglandin biosynthesis, and AREG, which codes for the EGFR ligand, amphiregulin. Both AREG and prostaglandin E2 converge to activate signaling through EGFR. Importantly, treatment with the COX-2 inhibitor Celecoxib significantly inhibited the growth of NF2-null Schwann cells and tumor growth in a mouse model of NF2.

Introduction

The Hippo-YAP signaling pathway has emerged as a major driver of tumorigenesis and metastasis in a wide spectrum of human cancers (1-3). The core of the pathway is composed of a well-defined kinase cascade comprised of the MST1/2 kinases that form a complex with the scaffold protein WW45 and phosphorylate the LATS1/2 kinases. Phosphorylated LATS1/2, in complex with Mob1, bind and phosphorylate YAP, a transcriptional co-activator. The phosphorylation of YAP creates a binding site for 14-3-3 and this prevents p-YAP from entering into the nucleus where it can form transcriptionally active complexes with TEAD and other transcription factors to drive the expression of pro-proliferative or anti-apoptotic genes such as CTGF, Cyr61, Axl, c-Myc and survivin (4).

As a regulator of cell fate, proliferation and death YAP can function as an oncogene. Several examples exist showing that YAP overexpression drives tumorigenesis including mouse models in which liver-specific expression of an activated allele of YAP or knockout of the MST1 and MST2 alleles in the liver lead to development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (5, 6). Additional evidence for an oncogenic role of YAP in human tumors stems from findings demonstrating amplification of genomic region 11q22, to which YAP localizes, in breast cancer and significant upregulation of YAP expression in breast, ovarian, lung, pancreatic, colorectal and liver cancers (7, 8). More recent studies have shown that YAP can function as an oncogene in tumors that are addicted to KRAS. Specifically, in models of KRAS-addicted tumors (pancreatic and lung adenocarcinoma) the inhibition of KRAS leads to cell death, which can be rescued by YAP activation (9, 10). Finally, genetic evidence for an oncogenic role for YAP in human cancer comes from two diseases, uveal melanoma (UM) and neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2). In UM 80% of patients harbor mutations in the GNAQ (Gq) and GNA11 (G11) genes, which code for alpha subunits of heterotrimeric G-proteins. Previous work had indicated YAP can be activated by mutated Gq/11 (11) and subsequently it was found that mutated Gq/11 oncogenic function is mediated via YAP, thus implicating YAP as a potential therapeutic target in UM (12, 13).

NF2 is an inherited disorder with an incidence of approximately 1 in 30,000 births, caused by germline mutations of the NF2 gene. The disease is characterized mainly by development of schwannomas of the eighth cranial nerve (14). The NF2 tumor suppressor gene encodes a 69-kDa protein called Merlin that has been shown to function as a regulator of multiple signaling pathways at the cell membrane and to possess nuclear functions. Merlin was originally shown to function upstream of Hippo in flies and subsequently in mammalian cells. A number of studies demonstrated that Merlin and YAP function antagonistically including in vivo studies in which liver-specific knockout of Yap was sufficient to rescue HCC driven by inactivation of the Nf2 gene (15).

Mechanistic details of Merlin’s function have emerged from studies which demonstrated Merlin acts synergistically with a newly identified Hippo pathway component, Kibra, to promote LATS1/2 phosphorylation (16) and regulate the spatial organization of Hippo pathway components at the cell membrane by directly binding to LATS1/2 and recruiting it to the plasma membrane, where it is phosphorylated and activated by a MST-WW45 complex (17). Merlin has also been shown to have a nuclear function as an inhibitor of the E3 ubiquitin ligase CRL4DCAF1 (18). Recent studies suggest CRL4DCAF1 promotes YAP and TEAD-dependent transcription by inhibition of LATS1/2 in the nucleus and analysis of patient samples indicates this pathway operates in NF2-mutant tumors (19).

Thus, while the evidence cited above strongly suggests YAP function is required downstream of NF2 loss of function in tumorigenesis, the mechanisms underlying the requirement for YAP and which downstream targets are critical to YAP’s oncogenic functions remain unknown. To identify these mechanisms and identify disease-relevant targets we employed a combination of cell-based and in vivo approaches. Our findings indicate YAP function is required in NF2-null Schwann cells to promote cell survival through regulation of an EGFR signaling axis via transcriptional regulation of Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (COX-2) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production. Importantly, our findings suggest treatment with COX-2 inhibitors could prove beneficial in slowing the growth rates of NF2-associated schwannomas.

Materials and methods

Animal Experiments

All animal experiments complied with NIH guidelines and were approved by The Scripps Research IACUC. 5×104 SC4-Luc pLKO or SC4-Luc pLKO-YAP cells were injected intraneurally into the sciatic nerves of NOD/SCID mice (6-8 weeks old). Tumor progression was monitored by bioluminescence imaging (BLI) on an IVIS-200 system (Xenogen, San Francisco, CA). Treatment was commenced after detection of signal correlating to tumor sizes of 1-2 mm3 (total flux ≥ 106 photons/s). For drug treatment, Celecoxib (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) was diluted in vehicle (22.2:66.6:11.2, ethanol:PEG300:water) to a final dose of 100 mg/kg and administered by oral gavage, daily. Control mice received vehicle/DMSO mixture.

Cell lines

SC4 Nf2-null mouse Schwann cells and HEI-193 human NF2-mutant Schwann cells were obtained in 2010 and previously described (20, 21). HSC2λ cells were obtained from the laboratory of Dr. Margret Wallace (U. of Florida) in 2015. These cells are derived from normal human Schwann cells that were immortalized by expression of TERT and CDK4R24C (Wallace, M.R. manuscript in preparation). SC4-Luc cells were previously described (22). SC4, HEI-193 and HSC2λ cells were authenticated by short tandem repeat (STR) DNA profiling (DDC Medical) (March 2015).

Cell Proliferation and Viability

Cell viability was determined by luminescent ATP-dependent assay (CellTiter-Glo, Promega), according to manufacturer’s instructions. For measurement of proliferation, the BrdU Proliferation Assay (Millipore) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed student’s t-test. Each condition at each timepoint represents the mean of 3 experiments in triplicate for a total of 9 wells.

Determination of Caspase activity

Measurement of caspase-dependent cell death was achieved through the use of the Caspase-Glo 3/7 assay following the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega). Briefly, cells were seeded into white, opaque 96-well culture plates at 1500 cells/well and transfected with control or YAP siRNAs. Caspase-Glo reagent was added at 24 or 48 hours and incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes, after which the luminescence was measured.

RNA-Seq

SC4 cells were transfected with control or YAP Smartpool siRNA’s for 48h, and total RNA was extracted using TRIZOL reagent. For analysis, the sequencing reads in color-space were mapped to the mm9 genome using Tophat (23). The number of reads falling into each gene defined in the RefSeq gene annotations was quantified using HTSeq-count (24). The DESeq software (24) was used to detect differentially expressed genes between samples. Samples from three independent experiments were sequenced, combined, and analyzed to produce the final DESeq data. The RNA-Seq data is publicly available through the NCBI GEO database with accession number GSE61528.

RT-PCR

RNAs were extracted using the Qiagen RNeasy kit and reverse-transcribed into cDNA with the SuperScript III kit (Life Technologies). qPCR was performed with SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems). Relative gene expression between control and YAP-KD was calculated with the 2−ΔΔCT method (25). For complete primer sequences please see supplementary table 2.

AREG ELISA

Cell media from SC4 and HEI-193 cells treated with the indicated siRNA’s was collected and diluted 2-fold with provided assay buffer (Mouse AREG ELISA and Human AREG ELISA, Raybiotech). Secreted AREG concentrations were assayed for three independent experiments in triplicate, according to manufacturer’s instructions. AREG concentrations were determined by comparing recorded absorbance readings to a standard curve of diluted AREG.

Results

YAP is required for NF2-null Schwann cell proliferation, survival and tumorigenesis

To examine the role of YAP in NF2-null Schwann cells, three cell lines were used: SC4 – Nf2-null mouse Schwann cells, HEI-193 – NF2-null schwannoma cells isolated from an NF2 patient and HSC2λ cells – immortalized normal human Schwann cells in which two shRNAs were used to knockdown the expression of Merlin (Figure S1A). As expected, the loss of Merlin expression resulted in increased cell numbers over time (Figure S1B).

Using two independent siRNA sequences and siRNA smartpool, the expression of YAP was knocked down and effects on cell numbers were examined. A significant decrease in cell numbers was observed, with numbers reduced 1.5 fold in SC4 cells, 2-fold for HEI-193 cells and 2 to 2.5-fold for HSC2λ cells, over the course of 72 hours, respectively (Figures 1A-B, S1C-E). Next, verteporfin (VP), a known inhibitor of the YAP-TEAD interaction was used to pharmacologically test the requirement of YAP in NF2-null Schwann cells (26). Treatment of SC4 and HEI-193 cells over 72 hours with 1μM VP significantly reduced cell numbers by 3 to 8-fold over 72 hours, respectively (Figure S1F-G).

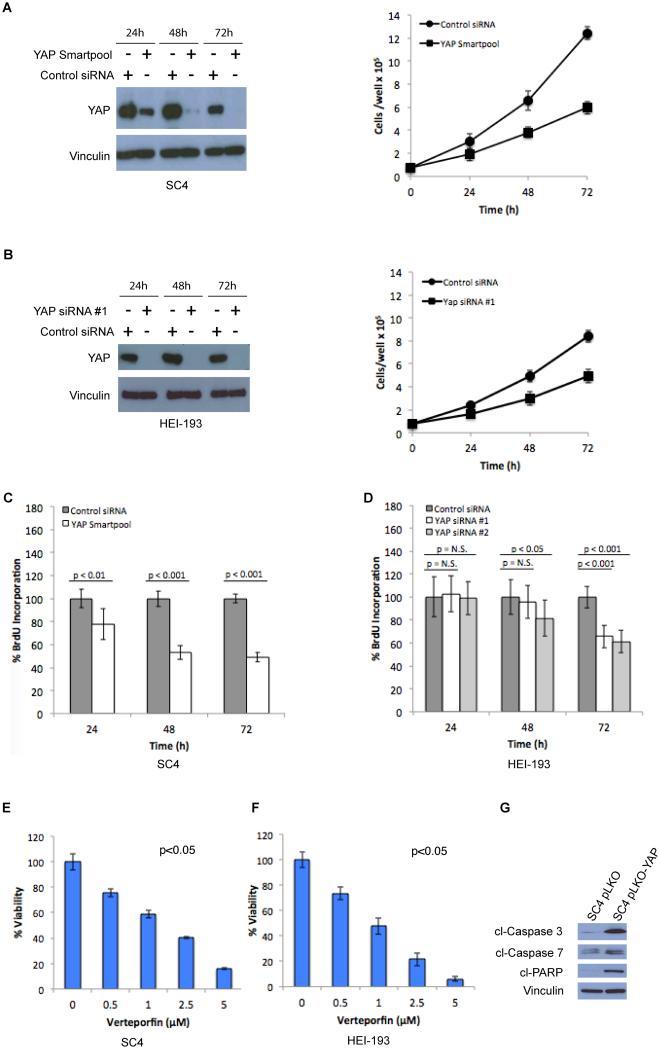

Figure 1. YAP is required for NF2-null Schwann cell proliferation and survival.

(A) SC4 cells were transfected with a control or YAP smartpool siRNA mix and (B) HEI-193 cells were transfected with control or 2 independent YAP siRNAs. YAP levels were assessed by western blot and cell numbers were scored at 24, 48 and 72 hours post-transfection. Proliferation of (C) SC4 or (D) HEI-193 cells were assessed by BrdU incorporation at 24, 48 and 72 hours post-transfection. (E) SC4 or (F) HEI-193 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of Verteporfin (VP) and cell viability measured at 24 hours using the CellTiter-Glo assay. (G) Cells infected with Lentiviral control-shRNA or YAP-shRNA were surveyed for markers of apoptosis. The data shown is the mean of 3 independent experiments, each done in triplicate. Error bars =SD.

To determine if the effects of YAP knockdown are due to reduced cell proliferation or increased cell death rates, we assessed BrdU incorporation in YAP knockdown SC4 and HEI-193 cells. BrdU incorporation was slightly reduced over 72-hours, indicating that YAP knockdown has a relatively small, but reproducible, impact on cell proliferation (Figure 1C-D). To assess the effects of YAP inhibition on cell death, we assessed the viability of SC4 and HEI-193 cells treated with VP in a dose-dependent manner. VP concentrations as low as 1μM caused a 50% reduction in viability of both SC4 and HEI-193 cells, as measured by an ATP-dependent luminescent assay (Figure 1E-F). That inhibition of YAP leads to increased cell death rates is further corroborated by increased levels of apoptotic markers, cleaved Caspase-3, Caspase-7 and PARP in SC4 cells infected with a vector expressing YAP shRNA (SC4 pLKO-YAP) compared to SC4 cells infected with a control shRNA vector (SC4 pLKO) (Figure 1G). Similarly, increased Caspase-3/7 activity was detected in SC4 and HEI-193 cells in which YAP expression was knocked down (Figures S1H-I).

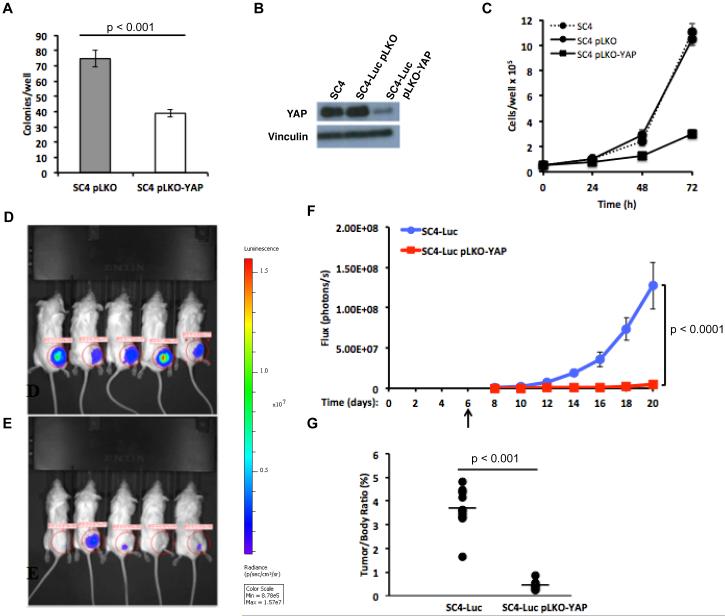

In order to investigate the requirement of YAP for Nf2-null Schwann cell tumorigenesis, we first assessed the ability of cells with YAP knockdown to form colonies in soft agar. SC4 pLKO and SC4 pLKO-YAP cells were plated at equal numbers and colony formation was assessed after 14 days. The knockdown of YAP significantly impaired the ability of SC4 pLKO-YAP cells to form colonies and reduced colony numbers by 2-fold (Figure 2A, S2A). Moreover, assessing colony size revealed a typical size of approximately 50μm for SC4 pLKO-YAP cells compared to approximately 200μm for the SC4 pLKO cells (Figure S2B). To assess the requirement of YAP for Nf2-null Schwann cell tumorigenesis in vivo, luciferase-expressing SC4 cells (SC4-Luc) were infected with either a control vector (SC4-Luc pLKO) or a vector expressing YAP shRNA (SC4-Luc pLKO-YAP) to generate SC4-Luc cells with stable YAP knockdown (Figure 2B), which lead to inhibition of SC4-Luc cell growth in culture (Figure 2C). SC4-Luc pLKO and SC4-Luc pLKO-YAP cells were orthotopically implanted into the sciatic nerves of NOD/SCID mice and schwannoma tumor formation and growth were monitored via bioluminescent imaging. Mice were imaged every other day, starting on day 6, and were sacrificed on day 20. Both control and YAP knockdown cohorts developed measurable tumor signals within 8 to 10 days post-implantation. However, compared to SC4-Luc pLKO controls, YAP knockdown significantly inhibited the growth of the Nf2-null schwannomas in vivo (Figure 2D-F and S2C). Subsequent ex vivo analysis of excised tumors indicated that tumors arising from SC4-Luc pLKO-YAP cells were significantly smaller than tumors in the control cohort (Figure 2G). Taken together, our data indicate that YAP activity is required for the proliferation and survival of Nf2-null Schwann cells in vitro and tumor growth in vivo.

Figure 2. YAP is required for growth of Nf2-null colonies in soft agar and schwannoma in vivo.

(A) Colony formation in soft agar was assessed by plating equal numbers of SC4 pLKO or SC4 pLKO-YAP cells and counting colonies after 14 days. (B) SC4-Luc cells were infected with a Lentiviral vector expressing control (SC4-Luc pLKO) or YAP shRNA (SC4-Luc pLKO-YAP). YAP levels were assessed by western blot 72h post-infection. (C) Cell numbers were assessed by counting at 24, 48 and 72 hours. The data shown in panels A and C is the mean of 3 independent experiments, each done in triplicate. Error bars =SD. (D) Representative images from bioluminescence imaging (BLI) of NOD/SCID mice carrying orthotopic tumors originating from SC4-Luc/pLKO or (E) SC4-Luc/pLKO-YAP at 20 days post surgery. (F) Quantitative analysis of flux reading from implanted cohorts. SC4-Luc pLKO control or SC4-Luc pLKO-YAP cells were implanted into the sciatic nerve (day 0). Animals were monitored every 2 days beginning at day 6 (arrow) after implantation, BLI signal was detected starting on day 8. Comparison of the tumor growth trends indicates the speed of tumor growth in the YAP knockdown group is significantly slower compared to control group. Error bars =SEM (G) Distribution of tumor/body weight ratios in the SC4-Luc/pLKO or SC4-Luc/pLKO-YAP cohorts. The results of t-test with equal variances show the YAP-KD group has significant lower average tumor weight ratio compared to control group. For the in vivo experiments: n=15 in each cohort.

YAP regulates diverse transcriptional programs in Nf2-null Schwann cells

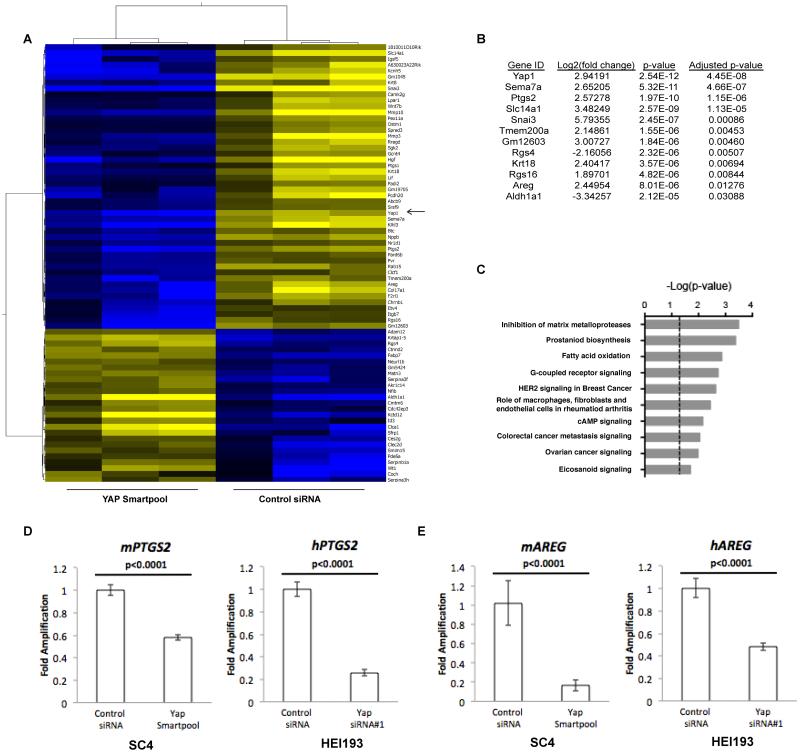

To understand the specific contribution of YAP to the survival of Nf2-null Schwann cells, an RNA sequencing approach was used to identify specific YAP-regulated genes. SC4 cells were treated with either non-targeting or pooled YAP siRNAs for 48 hours, followed by RNA isolation and sequencing. A number of genes were identified as significantly regulated by YAP and classified based on functional annotation including genes involved in regulation of matrix metalloproteases, prostanoid biosynthesis, fatty acid oxidation and G-coupled receptor signaling (Figure 3A-C). We focused on PTGS2, which codes for the COX-2 protein, an enzyme that functions as a catalytic intermediary in the synthesis of prostaglandins from arachidonic acid. PTGS2 was validated as a YAP target by RT-PCR in SC4 and HEI-193 cells, as knockdown of YAP resulted in a two to three-fold reduction in PTGS2 transcription, confirming the RNA-Seq results (Figure 3D). The top 12 genes regulated by YAP also included AREG, which has been previously reported as a YAP target and codes for amphiregulin (AREG), an EGFR ligand (Figure 3B) (27). YAP knockdown in both SC4 and HEI-193 cells resulted in two to five-fold reduction in AREG transcription (Figure 3E). Examination of intracellular levels of COX-2 protein by western blot in the presence or absence of YAP indicates that in response to YAP knockdown, COX-2 levels are drastically reduced. (Figure 4A). To assess levels of AREG, we analyzed the cell culture media for secreted protein employing an ELISA approach. A highly reproducible decrease in secreted AREG was observed in the culture media of SC4 and HEI-193 cells in which YAP or AREG are knocked down (Figures 4B and S3A).

Figure 3. Targets of YAP-dependent transcription.

(A) Hierarchical clustering of differentially expressed genes between SC4 treated with control or YAP siRNA. Three independent RNA preparations were analyzed. YAP indicated by arrow. (B) List of top 12 genes differently expressed between SC4 treated with control or YAP siRNA, ranked by adjusted p-value. (C) Top 10 enriched canonical pathways based on analysis of differentially expressed genes. RT-PCR validation of PTGS2 (D) and AREG (E) as YAP-dependent transcriptional targets in SC4 and HEI-193 cells. The data shown is the mean of 3 independent experiments, each done in triplicate. Error bars =SD.

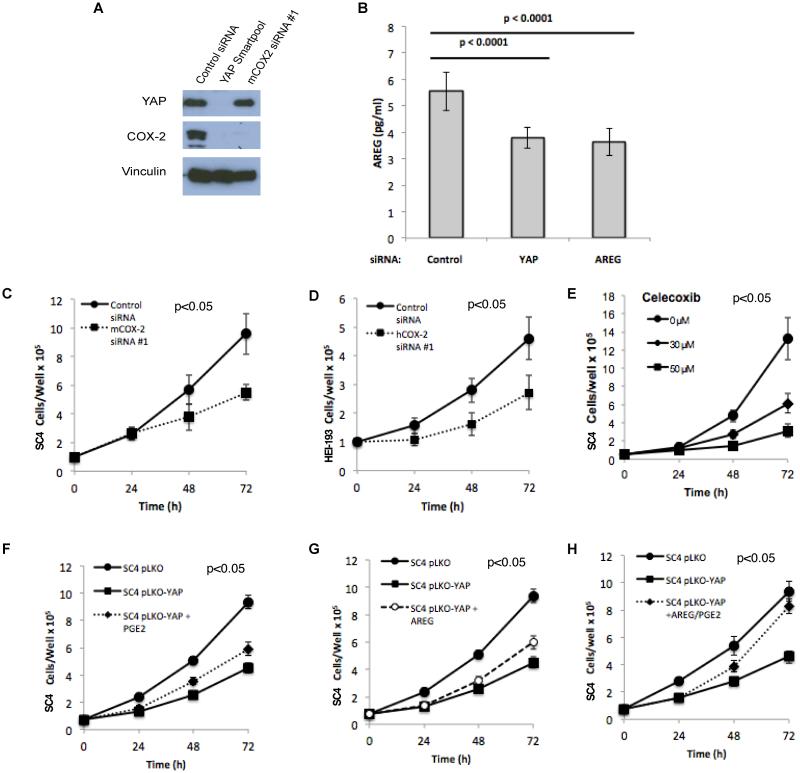

Figure 4. COX-2 is a downstream effector of YAP and is required for NF2-null Schwann cell growth.

(A) Western blot analysis of YAP and COX-2 protein levels in SC4 cells transfected with control siRNA, YAP siRNA Smartpool or COX-2 siRNA. Vinculin used as a loading control. (B) Levels of secreted amphiregulin in culture media of SC4 cells transfected with control, YAP or AREG smartpool siRNA for 48h. (C) SC4 or (D) HEI-193 cells were transfected with control or COX-2 siRNA. Cell numbers were scored at 24, 48 and 72 hours post-transfection. (E) Inhibition of COX-2 with Celecoxib inhibits the proliferation of SC4 cells in a dose-dependent manner. (F) PGE2 (1μM) or (G) AREG (amphiregulin 100ng/ml) partially rescue decreased SC4 cell numbers in response to YAP knockdown. (H) Combined PGE2 and amphiregulin treatment fully rescues decreased SC4 proliferation in response to YAP knockdown. SC4 cells were transfected with control (pLKO) or YAP shRNA (pLKO-YAP) expressing vectors and treated with PGE2, AREG or both every 12 hours. Cell proliferation was assessed by counting 24, 48 and 72 hours after initial PGE2 or amphiregulin treatment. The data shown is the mean of 3 independent experiments, each done in triplicate. Error bars =SD.

COX-2 is a target of YAP required for growth of NF2-null Schwann cells

COX-2 functions as a mediator of prostanoid synthesis, including Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), previously shown to promote proliferation and survival of various types of tumor cells (28). Thus, the identification and confirmation of AREG and PTGS2 as targets of YAP-dependent transcription links two paracrine signaling mediators of cell survival to the Hippo-YAP pathway in NF2-null Schwann cells. To assess the specific role of COX-2 downstream of YAP in NF2-null schwannoma cells, SC4 and HEI-193 cells were treated with control or COX-2 siRNA and the effect on cell numbers was assessed (Figures 4A, 4C-D and S3B-C). In both cell lines, COX-2 knockdown reduced cell numbers by approximately 50% at 72 hours, although this was not as strong as YAP knockdown (compare to Figure 1A-B), implicating additional downstream effectors in mediating YAP activity. To assess the requirement for COX-2 activity in driving YAP-dependent increase in cell numbers, we also employed the COX-2 inhibitor Celecoxib, which significantly inhibited the growth of SC4 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4E).

To determine if the effects of YAP-COX-2 are mediated through PGE2, SC4 pLKO-YAP cells were treated with exogenous PGE2 in an attempt to rescue the phenotype conferred by YAP knockdown. PGE2 treatment was able to partially rescue the effects of YAP knockdown by approximately 30% at 72 hours (Figure 4F). These results indicate COX-2 and PGE2 are essential effectors of YAP activity that are required, at least in part, for Nf2-null Schwann cell growth.

Given the partial rescue of the effects of YAP knockdown by PGE2, we next assessed whether the combination of PGE2 and AREG would result in a greater rescue of the YAP knockdown phenotype. While treatment with PGE2 or AREG alone led to only a partial rescue of the YAP knockdown phenotype, the combined actions of both targets rescued the phenotype, increasing cell numbers to levels comparable to control SC4-pLKO cells (Figure 4F-H). Importantly, treatment of control SC4-pLKO cells with the PGE2-AREG combination did not have a significant impact on cell numbers (Figure S3D). Taken together, these findings strongly indicate that YAP regulates Nf2-null Schwann cell growth by coordinated regulation of AREG and COX-2.

YAP regulates EGFR signaling in NF2-null Schwann cells

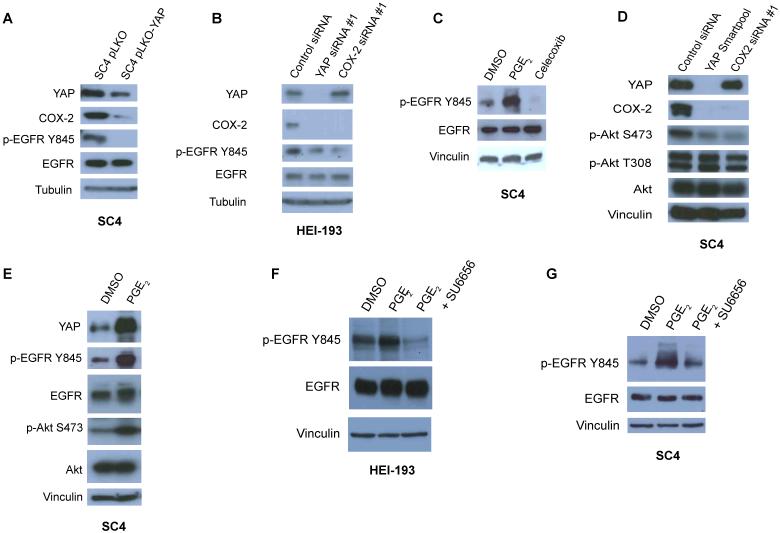

PGE2 is known to promote cell proliferation and inhibit apoptosis through Src-dependent transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and PI3K-AKT activation downstream (28). We therefore examined the levels and status of EGFR phosphorylation in SC4, HEI-193 and HSC2λ-shNF2 cells in the absence of YAP. While total EGFR levels remain unchanged upon YAP knockdown, the activation of EGFR was greatly reduced as indicated by reduced phosphorylation on tyrosine 845 (Figure 5A-B and S4A-B). Similar results were found with knockdown of COX-2 in HEI-193 cells and by treatment of SC4 cells with the COX-2 inhibitor Celecoxib (Figure 5B-C). Examination of the activation status of AKT revealed similar findings. While the levels of total AKT were not significantly affected by the presence or absence of YAP or COX-2, the phosphorylation at serine 473 decreased in a YAP- and COX-2-dependent manner (Figure 5D, S4C). As we previously determined that PGE2 can partially rescue the effects of YAP knockdown at the cellular levels (Figure 4F), we next sought to determine whether the activation of EGFR and AKT by YAP-COX-2 is mediated by PGE2. Indeed, short-term exposure of SC4 cells to PGE2 caused a significant increase in EGFR-Y845 and AKT-S473 phosphorylation (Figure 5E). Interestingly, PGE2 treatment also resulted in elevated YAP levels, suggesting a feedback loop may exist between YAP and COX-2.

Figure 5. YAP signals through multiple downstream effectors to drive proliferation and survival.

(A) Western blot analysis of EGFR levels and activation in SC4 cells transfected with control (pLKO) or YAP shRNA (pLKO-YAP) expressing vectors. (B) Analysis of EGFR levels and activation in HEI-193 cells transfected with control, YAP or COX-2 siRNA. (C) Analysis of EGFR levels and activation in SC4 cells treated with PGE2 (1μM, 10 min) or Celecoxib (20μM, 8 h) (D) Western blot analysis of COX-2, YAP and AKT levels and activation in SC4 cells transfected with control or YAP siRNA Smartpool, or COX-2 siRNA. (E) Western blot analysis of EGFR and AKT levels and activation in SC4 cells treated with PGE2 (1μM, 10 min). (F) HEI-193 and (G) SC4 cells were treated with PGE2 (1μM, 10 min) in the presence or absence of SU6656 pre-treatment (12h, 280 nM). Western blots were used to assess EGFR levels and activation. Vinculin or tubulin used as a loading controls, as indicated. DMSO-treated cells were used as negative controls. The experiments shown are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Since we observed phosphorylation of EGFR on tyrosine 845 in response to treatment with PGE2, we next examined the possible contribution of Src, which is known to phosphorylate EGFR at tyrosine 845 and previously shown to transactivate EGFR in response to PGE2 in colorectal cancer cells (29, 30). Treatment with the Src inhibitor SU6656 alone decreased phosphorylation of EGFR-Y845, which is perhaps expected, given a basal level of EGFR activity supporting cell survival (Figure S4D). Significantly, pretreatment of cells with SU6656 inhibited PGE2-induced EGFR phosphorylation, implicating Src as a mediator of EGFR activation by PGE2 (Figures 5F-G, S4E-F). Taken together, these findings strongly indicate that YAP regulates Nf2-null Schwann cell proliferation and survival through an EGFR-AKT signaling pathway.

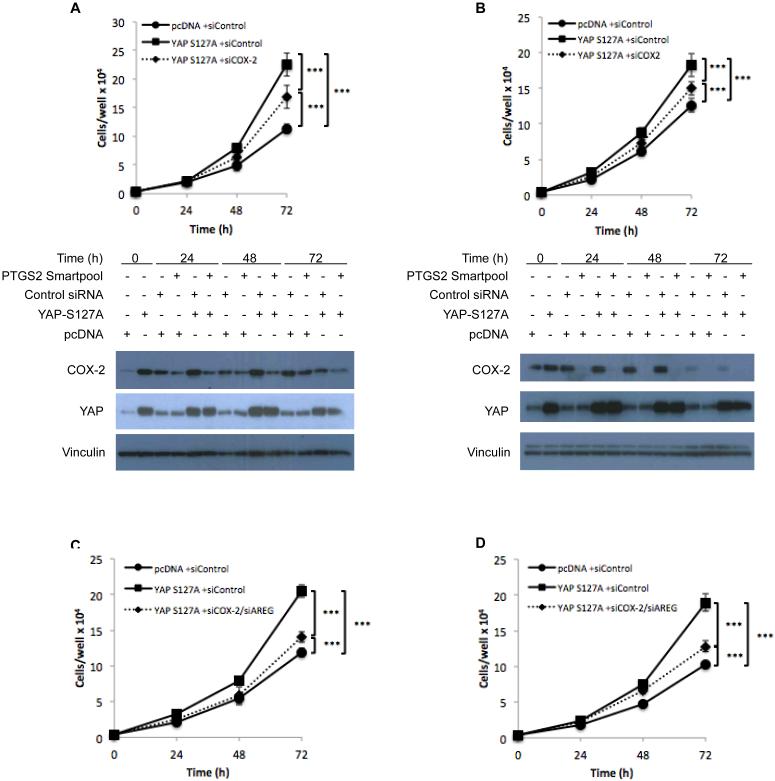

Promotion of NF2-null Schwann cell growth by YAP is mediated through COX-2 and AREG

To determine the extent to which the effects of YAP on NF2-null Schwann cells are mediated by COX-2 and AREG, we employed a gain-of-function approach and assessed consequences of expressing a constitutively activated allele of YAP (YAPS127A) in SC4 and HSC2λ-shNF2 cells. The expression of YAPS127A in both cell lines led to increased expression of COX-2 and AREG (Figure S5A-H and 6A-B). Moreover, the expression of YAPS127A also had a significant effect at the cellular level, as evidenced by increases in SC4 (2.5 fold at 72 hours) and HSC2λ (2 fold at 72 hours) cell numbers over time, compared to control transfected cells (Figure 6A-B). The effects of YAPS127A expression were dependent on COX-2, as knocking down COX-2 expression partially rescued the growth advantage conferred by expression of YAPS127A (Figure 6A-B, S5I-J). Given the partial rescue by COX-2 knockdown, we next assessed whether the combination of COX-2 and AREG knockdown would result in a greater inhibition. Indeed, combined inhibition led to an almost complete rescue of the growth advantage (Figure 6C-D), strongly suggesting that growth advantage conferred by expression of YAPS127A is mediated through coordinated regulation of AREG and COX-2.

Figure 6. Promotion of NF2-null Schwann cell growth by YAP is mediated through COX-2 and AREG.

The requirement for COX-2 and AREG for YAP-driven cell proliferation was assessed in SC4 (A, Top) and HSC2λ-shNF2 71-10 cells (B, Top) by transfection with either pcDNA control or YAPS127A expression vectors. After 24 hours, cells were reverse transfected with either control or COX-2 pooled siRNA’s, seeded, and counted at 24, 48, and 72 hours. Western blotting was used to assess protein levels of YAP and COX-2 (A-B, Bottom). Vinculin used as a loading control. (C) SC4 and (D) HSC2λ shNF2 71-10 cells were transfected with either pcDNA control or YAPS127A expression vectors. After 24 hours, cells were reverse transfected with either control or AREG and COX-2 pooled siRNA’s, seeded, and counted at 24, 48, and 72 hours to assess changes in cell numbers. Data is the mean of 3 experiments with each condition counted in triplicate. Error bars = SD. (*** = p <0.001).

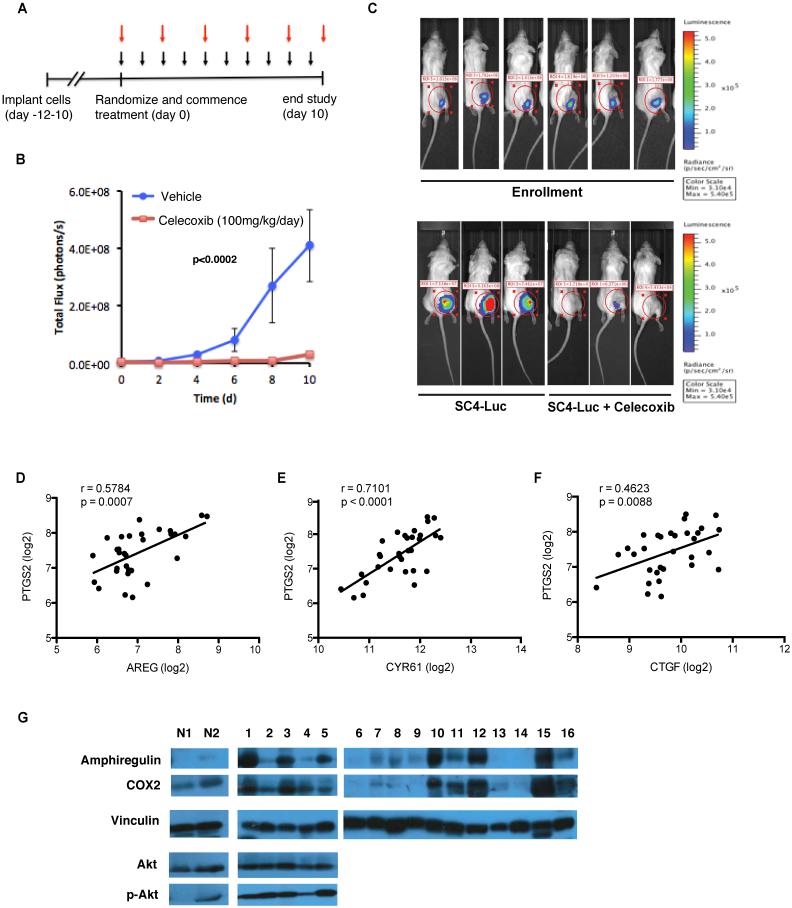

Inhibition of COX-2 slows tumor progression in vivo

Our findings suggest that treatment with a COX-2 inhibitor, such as Celecoxib, could inhibit the growth of Nf2-null schwannomas. To test this hypothesis in vivo, we employed the orthotopic model of Neurofibromatosis Type 2 described above. Tumor progression was monitored every other day by bioluminescence imaging (BLI) and total flux counts were recorded for each animal. Between ten to twelve days post injection, animals reached similar flux readings indicating measurable tumors (flux = 106 counts) and were enrolled randomly into control (vehicle only, oral, once daily) or Celecoxib-treated cohorts (100mg/kg, oral, once daily) for a period of 10 days. Analysis of the flux readings for the animals in the two cohorts demonstrated a significantly slower tumor growth rate in Celecoxib-treated mice compared to control mice (Figure 7A-C). Taken together, these data demonstrate that inhibition of COX-2 significantly impaired Nf2-null Schwann cells growth and tumor formation in vivo.

Figure 7. Outcomes of Celecoxib treatment and analysis of PTGS2/COX-2 and AREG expression in NF2-null schwannomas.

Celecoxib treatment inhibits Nf2-null schwannoma tumor growth in vivo. (A) SC4-Luc cells were implanted into the sciatic nerve of NOD/SCID mice. Animals were randomized and enrolled into control or treatment cohorts when BLI measurements reached 106 flux counts (day 0). Treatment cohorts were dosed with 100 mg/kg Celecoxib daily while control cohorts received vehicle (black arrows). BLI measurements were recorded every other day, for 10 days (red arrows). (B) Quantitative analysis of flux readings from treated cohorts. Comparison of the tumor growth trends indicates the speed of tumor growth in the Celecoxib-treated group is significantly slower than that in control group (p<0.0002). Error bars =SEM. n=15 in each cohort. (C) Representative images from bioluminescence imaging (BLI) of NOD/SCID mice carrying orthotopic tumors originating from SC4-Luc cells at the time of enrollment (day 0) or treated with vehicle only or Celecoxib at 10 days of treatment (Bottom). (D-F) Assessment of the correlation between PTGS2 and YAP target gene expression. The correlation between PTGS2 and AREG (D), Cyr61 (E) or CTGF (F) mRNA expression in vestibular schwannomas (N=31) (G) Western blot analysis of COX-2, amphiregulin, AKT and p-AKT levels in protein extracts prepared from NF2-null schwannoma tissue (1-16) and normal nerve tissue (N1-N2). Vinculin used as a loading control.

COX-2 and AREG expression are correlated in NF2-null schwannomas

Our findings suggest that AREG and PTGS2 should be co-regulated in NF2-null Schwannoma. To assess this, we examined the expression of these genes in an existing expression microarray dataset prepared from 31 vestibular schwannomas (VS) (31). AREG and PTGS2 displayed a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.5784 (P=0.0007), suggesting a correlation exists between expression levels of both alleles at the transcriptional level (Figure 7D). Interestingly, the expression of PTGS2 also shows a statistically significant correlation with CYR61 (r= 0.7101, p<0.0001) and CTGF (r=0.4623, p=0.0088) (Figure 7E-F), which have been previously characterized as YAP target genes (32). To further confirm the correlation between AREG and COX-2 at the protein level, we assessed the levels of AREG and COX-2 in protein extracts prepared from NF2-null schwannomas. AREG and COX-2 are expressed in the majority of tumors examined (10 of 16), and in agreement with the expression array data, the levels of AREG and COX-2 protein appear to correlate in the majority of these tumors (Figure 7G). In a limited number of tumors we were also able to assess the levels of AKT and p-AKT S473, which appear to be consistent between the samples (Figure 7G).

Discussion

While mechanistic details of YAP regulation and downstream targets are emerging, relatively little is known about relevance and function of these targets in cancer. YAP has been shown to drive expression of a number of mRNAs and miRNAs implicated in various aspects of cell proliferation and transformation including connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), the receptor tyrosine kinase Axl, epidermal growth factor receptor ligand amphiregulin (AREG), the cell cycle regulator cyclin D1 and the FoxM1 transcription factor (32-35). Previous studies indicate YAP can suppress PTEN levels through expression of miR-29 and regulate global miRNA biogenesis through microprocessor activity (36, 37). It is likely that YAP regulates many of these targets in a cell and tissue-specific manner, and further work is required to establish the relevance of these targets in YAP-dependent tumors.

Merlin, the product of the NF2 tumor suppressor gene, is well established as an upstream regulator of the Hippo signaling pathway. However, the role of YAP in NF2-null schwannomas has yet to be established. Our findings demonstrate YAP is required for the survival and proliferation of Nf2-null Schwann cells and tumor formation in vivo. From the broad range of transcripts regulated by YAP, we focused on PTGS2, which codes for COX-2, has recently been identified as a direct target of YAP in a model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (38). COX-2 expression is typically low in normal tissue but reported as elevated in multiple types of cancers including pancreatic, lung, head and neck, prostate and breast tumors (28). COX-2 is a critical enzyme in biosynthesis of prostaglandins, of which PGE2 has been identified as playing a major role in promoting tumor growth (39-41).

Prostaglandins impact tumorigenesis through multiple mechanisms including modulation of tumor cell proliferation and apoptosis, as well as modulation of the tumor microenvironment and immune responses. Most relevant to our studies are cell-autonomous functions of PGE2. Specifically, PGE2 promotes cell proliferation in colon and lung cancer cells through the Ras-MAPK and GSK3β-β-catenin signaling pathways (42-44), has been shown to promote colon tumor cell survival through activation of a PI3K-AKT-PPARγ axis (39, 45) and promote colorectal cancer cell migration and invasion through activation of and EGFR-AKT signaling axis, through a β-arrestin/Src-mediated intracellular mechanism (46).

In our studies, we find that PGE2–mediated activation of EGFR-AKT signaling promotes cell survival of Merlin-deficient schwannoma cells (Figure S6). This likely reflects a cell type-specific difference in the role of this signaling axis between CRC and Schwann tumor cells. Indeed, one example of a different roles undertaken by the same PGE2 –activated pathway include recent studies showing that PGE2, through a PI3K-AKT signaling cascade, can protect mouse ES cells from undergoing apoptosis (47). As far as Src involvement, our studies with SU6656 suggest that Src, or another family member, functions as a mediator of the effects of PGE2 and further studies are required to clearly identify the responsible mediator. Interestingly, the effects of YAP knockdown on Nf2-null Schwann cells were only partially rescued by PGE2 treatment and required supplementation of amphiregulin. It has been previously reported that PGE2 –mediated activation of EGFR in CRC cells is dependent on TGF-α, an EGFR ligand (30). Thus, it is possible that in Schwann cells the YAP-coordinated expression of AREG and PTGS2 functions in a similar fashion to what is observed in CRC cells.

Although the Hippo-YAP pathway probably carries out additional functions in NF2-null Schwann cells, EGFR-mediated suppression of apoptosis appears to represent a major function in promotion of schwannoma tumorigenesis, as suggested by rescue of the YAP knockdown phenotype by AREG and PGE2 –mediated activation of EGFR/AKT. Indeed, EGFR has been previously implicated in the pathogenesis of sporadic and NF2-associated schwannomas with consistent overexpression and activation of EGFR family receptors reported (48). It has been suggested that Merlin regulates EGFR internalization and signaling in response to cell:cell contact inhibition (49). Our studies suggest the activation of EGFR is mediated through YAP-coordinated expression of AREG and COX-2-PGE2-EGFR activation (Figure S6). Further studies are required to determine if both mechanisms function in NF2-null Schwann cells.

To establish the relevance of YAP coordinated expression of AREG and COX-2 to NF2 patients, we analyzed the expression of COX-2/AREG in NF2-null schwannomas. COX-2 and AREG expression appeared to be correlated both at the mRNA and protein levels, suggesting they are indeed regulated coordinately. As the number of normal nerve tissue samples in our study is low, it is difficult to determine whether the fact that COX-2/AREG do not appear to be co-regulated in these samples is significant. Interestingly, PTGS2 expression also correlated with the expression of CYR61 and CTGF in patient samples, suggestive of a role for a YAP-regulated transcriptional program in these tumors. Clearly more work is needed to establish the extent of YAP regulated pathways involvement and to determine the significance of the relative levels of COX-2/AREG expression in tumors versus normal tissue. The finding that AKT appears to be activated in all tumor samples examined, compared to normal, is not surprising given the central role of PI3K/AKT signaling in tumorigenesis and the fact that multiple upstream effectors feed into this signaling hub.

Previous studies describe elevated COX-2 expression in VS, which appear to positively correlate with a higher proliferation index (50). Moreover, a retrospective analysis of VS patients demonstrated that aspirin use shows an inverse correlation with tumor growth (51). Our findings identify a tumor cell-intrinsic mechanism, through which the effects of daily administration of Celecoxib elicited a pronounced antitumor effect, and suggest that long-term treatment with NSAIDs could provide a benefit to NF2 patients. A number of reports have indicated Celecoxib has anticancer activity that is COX-2-independent (52). However, the inhibitory effects we observed on Nf2-null Schwann cell proliferation with direct knockdown of COX-2, along with pharmacological inhibition, underscore a significant role for COX-2 in NF2-null schwannomas. Future studies employing immune-competent animal models of NF2 will be required to elucidate the effects of COX-2 inhibition on other well-documented functions of eicosanoids, including the promotion of inflammation and effects on the tumor microenvironment, the role of PGE2 in immune suppression and, perhaps highly relevant to VS, pro-angiogenic activities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. David Lim (House Ear Institute) for sharing HEI-193 cells, Drs. Margaret Wallace and Hua Li (University of Florida) for immortalized human Schwann cells and Dr. Kirill Martemyanov (Scripps Research Institute) for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank the Scripps Genomics Core and Gautam Shankar from the Scripps Informatics Core.

This work was supported by the NIH (NS077952 and CA124495 to J.L. Kissil).

W. Guerrant is a recipient of the YIA from the Children’s Tumor Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Zhao B, Li L, Lei Q, Guan KL. The Hippo-YAP pathway in organ size control and tumorigenesis: an updated version. Genes Dev. 2010;24:862–74. doi: 10.1101/gad.1909210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pan D. The hippo signaling pathway in development and cancer. Dev Cell. 2010;19:491–505. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halder G, Johnson RL. Hippo signaling: growth control and beyond. Development. 2011;138:9–22. doi: 10.1242/dev.045500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson R, Halder G. The two faces of Hippo: targeting the Hippo pathway for regenerative medicine and cancer treatment. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13:63–79. doi: 10.1038/nrd4161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu L, Li Y, Kim SM, Bossuyt W, Liu P, Qiu Q, et al. Hippo signaling is a potent in vivo growth and tumor suppressor pathway in the mammalian liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:1437–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911427107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou D, Conrad C, Xia F, Park JS, Payer B, Yin Y, et al. Mst1 and Mst2 maintain hepatocyte quiescence and suppress hepatocellular carcinoma development through inactivation of the Yap1 oncogene. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:425–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinhardt AA, Gayyed MF, Klein AP, Dong J, Maitra A, Pan D, et al. Expression of Yes-associated protein in common solid tumors. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:1582–9. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harvey KF, Zhang X, Thomas DM. The Hippo pathway and human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:246–57. doi: 10.1038/nrc3458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shao DD, Xue W, Krall EB, Bhutkar A, Piccioni F, Wang X, et al. KRAS and YAP1 converge to regulate EMT and tumor survival. Cell. 2014;158:171–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kapoor A, Yao W, Ying H, Hua S, Liewen A, Wang Q, et al. Yap1 activation enables bypass of oncogenic kras addiction in pancreatic cancer. Cell. 2014;158:185–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu FX, Zhao B, Panupinthu N, Jewell JL, Lian I, Wang LH, et al. Regulation of the Hippo-YAP pathway by G-protein-coupled receptor signaling. Cell. 2012;150:780–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng X, Degese MS, Iglesias-Bartolome R, Vaque JP, Molinolo AA, Rodrigues M, et al. Hippo-Independent Activation of YAP by the GNAQ Uveal Melanoma Oncogene through a Trio-Regulated Rho GTPase Signaling Circuitry. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:831–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu FX, Luo J, Mo JS, Liu G, Kim YC, Meng Z, et al. Mutant Gq/11 Promote Uveal Melanoma Tumorigenesis by Activating YAP. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:822–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gusella JF, Ramesh V, MacCollin M, Jacoby LB. Merlin: the neurofibromatosis 2 tumor suppressor. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1423:M29–36. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(99)00005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang N, Bai H, David KK, Dong J, Zheng Y, Cai J, et al. The Merlin/NF2 tumor suppressor functions through the YAP oncoprotein to regulate tissue homeostasis in mammals. Dev Cell. 2010;19:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu J, Zheng Y, Dong J, Klusza S, Deng WM, Pan D. Kibra functions as a tumor suppressor protein that regulates Hippo signaling in conjunction with Merlin and Expanded. Dev Cell. 2010;18:288–99. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin F, Yu J, Zheng Y, Chen Q, Zhang N, Pan D. Spatial Organization of Hippo Signaling at the Plasma Membrane Mediated by the Tumor Suppressor Merlin/NF2. Cell. 2013;154:1342–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li W, You L, Cooper J, Schiavon G, Pepe-Caprio A, Zhou L, et al. Merlin/NF2 suppresses tumorigenesis by inhibiting the E3 ubiquitin ligase CRL4(DCAF1) in the nucleus. Cell. 2010;140:477–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li W, Cooper J, Zhou L, Yang C, Erdjument-Bromage H, Zagzag D, et al. Merlin/NF2 Loss-Driven Tumorigenesis Linked to CRL4(DCAF1)-Mediated Inhibition of the Hippo Pathway Kinases Lats1 and 2 in the Nucleus. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrison H, Sperka T, Manent J, Giovannini M, Ponta H, Herrlich P. Merlin/neurofibromatosis type 2 suppresses growth by inhibiting the activation of Ras and Rac. Cancer research. 2007;67:520–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hung G, Faudoa R, Li X, Xeu Z, Brackmann DE, Hitselberg W, et al. Establishment of primary vestibular schwannoma cultures from neurofibromatosis type-2 patients. Int J Oncol. 1999;14:409–15. doi: 10.3892/ijo.14.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yi C, Troutman S, Fera D, Stemmer-Rachamimov A, Avila JL, Christian N, et al. A tight junction-associated Merlin-angiomotin complex mediates Merlin's regulation of mitogenic signaling and tumor suppressive functions. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:527–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–11. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu-Chittenden Y, Huang B, Shim JS, Chen Q, Lee SJ, Anders RA, et al. Genetic and pharmacological disruption of the TEAD-YAP complex suppresses the oncogenic activity of YAP. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1300–5. doi: 10.1101/gad.192856.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kimura H, Fischer WH, Schubert D. Structure, expression and function of a schwannoma-derived growth factor. Nature. 1990;348:257–60. doi: 10.1038/348257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang D, Dubois RN. Eicosanoids and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:181–93. doi: 10.1038/nrc2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biscardi JS, Maa MC, Tice DA, Cox ME, Leu TH, Parsons SJ. c-Src-mediated phosphorylation of the epidermal growth factor receptor on Tyr845 and Tyr1101 is associated with modulation of receptor function. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:8335–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.8335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pai R, Soreghan B, Szabo IL, Pavelka M, Baatar D, Tarnawski AS. Prostaglandin E2 transactivates EGF receptor: a novel mechanism for promoting colon cancer growth and gastrointestinal hypertrophy. Nature medicine. 2002;8:289–93. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torres-Martin M, Lassaletta L, San-Roman-Montero J, De Campos JM, Isla A, Gavilan J, et al. Microarray analysis of gene expression in vestibular schwannomas reveals SPP1/MET signaling pathway and androgen receptor deregulation. Int J Oncol. 2013;42:848–62. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao B, Ye X, Yu J, Li L, Li W, Li S, et al. TEAD mediates YAP-dependent gene induction and growth control. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1962–71. doi: 10.1101/gad.1664408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu MZ, Chan SW, Liu AM, Wong KF, Fan ST, Chen J, et al. AXL receptor kinase is a mediator of YAP-dependent oncogenic functions in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2011;30:1229–40. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang J, Ji JY, Yu M, Overholtzer M, Smolen GA, Wang R, et al. YAP-dependent induction of amphiregulin identifies a non-cell-autonomous component of the Hippo pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1444–50. doi: 10.1038/ncb1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mizuno T, Murakami H, Fujii M, Ishiguro F, Tanaka I, Kondo Y, et al. YAP induces malignant mesothelioma cell proliferation by upregulating transcription of cell cycle-promoting genes. Oncogene. 2012;31:5117–22. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tumaneng K, Schlegelmilch K, Russell RC, Yimlamai D, Basnet H, Mahadevan N, et al. YAP mediates crosstalk between the Hippo and PI(3)K-TOR pathways by suppressing PTEN via miR-29. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:1322–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mori M, Triboulet R, Mohseni M, Schlegelmilch K, Shrestha K, Camargo FD, et al. Hippo signaling regulates microprocessor and links cell-density-dependent miRNA biogenesis to cancer. Cell. 2014;156:893–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang W, Nandakumar N, Shi Y, Manzano M, Smith A, Graham G, et al. Downstream of mutant KRAS, the transcription regulator YAP is essential for neoplastic progression to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Sci Signal. 2014;7:ra42. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang D, Wang H, Shi Q, Katkuri S, Walhi W, Desvergne B, et al. Prostaglandin E(2) promotes colorectal adenoma growth via transactivation of the nuclear peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:285–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Myung SJ, Rerko RM, Yan M, Platzer P, Guda K, Dotson A, et al. 15-Hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase is an in vivo suppressor of colon tumorigenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:12098–102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603235103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakanishi M, Montrose DC, Clark P, Nambiar PR, Belinsky GS, Claffey KP, et al. Genetic deletion of mPGES-1 suppresses intestinal tumorigenesis. Cancer research. 2008;68:3251–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang D, Buchanan FG, Wang H, Dey SK, DuBois RN. Prostaglandin E2 enhances intestinal adenoma growth via activation of the Ras-mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Cancer research. 2005;65:1822–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Castellone MD, Teramoto H, Williams BO, Druey KM, Gutkind JS. Prostaglandin E2 promotes colon cancer cell growth through a Gs-axin-beta-catenin signaling axis. Science. 2005;310:1504–10. doi: 10.1126/science.1116221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krysan K, Reckamp KL, Dalwadi H, Sharma S, Rozengurt E, Dohadwala M, et al. Prostaglandin E2 activates mitogen-activated protein kinase/Erk pathway signaling and cell proliferation in non-small cell lung cancer cells in an epidermal growth factor receptor-independent manner. Cancer research. 2005;65:6275–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sheng H, Shao J, Morrow JD, Beauchamp RD, DuBois RN. Modulation of apoptosis and Bcl-2 expression by prostaglandin E2 in human colon cancer cells. Cancer research. 1998;58:362–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buchanan FG, Wang D, Bargiacchi F, DuBois RN. Prostaglandin E2 regulates cell migration via the intracellular activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:35451–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302474200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liou JY, Ellent DP, Lee S, Goldsby J, Ko BS, Matijevic N, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2-derived prostaglandin e2 protects mouse embryonic stem cells from apoptosis. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1096–103. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ammoun S, Cunliffe CH, Allen JC, Chiriboga L, Giancotti FG, Zagzag D, et al. ErbB/HER receptor activation and preclinical efficacy of lapatinib in vestibular schwannoma. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12:834–43. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Curto M, Cole BK, Lallemand D, Liu CH, McClatchey AI. Contact-dependent inhibition of EGFR signaling by Nf2/Merlin. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:893–903. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hong B, Krusche CA, Schwabe K, Friedrich S, Klein R, Krauss JK, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 supports tumor proliferation in vestibular schwannomas. Neurosurgery. 2011;68:1112–7. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318208f5c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kandathil CK, Dilwali S, Wu CC, Ibrahimov M, McKenna MJ, Lee H, et al. Aspirin intake correlates with halted growth of sporadic vestibular schwannoma in vivo. Otol Neurotol. 2014;35:353–7. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jendrossek V. Targeting apoptosis pathways by Celecoxib in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2013;332:313–24. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.