Abstract

Purpose

Recurrent malignant glioma carries a dismal prognosis, and novel therapies are needed. We examined the feasibility and safety of vaccination with irradiated autologous glioma cells mixed with irradiated GM-K562 cells in patients undergoing craniotomy for recurrent malignant glioma.

Patients and Methods

We initiated a phase I study examining the safety of 2 doses of GM-K562 cells mixed with autologous cells. Primary endpoints were feasibility and safety. Feasibility was defined as the ability for 60% of enrolled subjects to initiate vaccination. Dose-limiting toxicity (DTH) was assessed via a 3+3 dose-escalation format, examining irradiated tumor cells mixed with 5×106 GM-K562 cells or 1×107 GM-K562 cells. Eligibility required a priori indication for resection of a recurrent high-grade glioma. We measured biological activity by measuring delayed type hypersensitivity (DTH) responses, humoral immunity against tumor-associated antigens, and T-lymphocyte activation.

Results

11 patients were enrolled. Sufficient numbers of autologous tumor cells were harvested in 10 patients, all of whom went on to receive vaccine. There were no dose-limiting toxicities. Vaccination strengthened DTH responses to irradiated autologous tumor cells in most patients, and vigorous humoral responses to tumor-associated angiogenic cytokines were seen as well. T-lymphocyte activation was seen with significantly increased expression of CTLA-4, PD-1, 4-1BB, and OX40 by CD4+ cells and PD-1 and 4-1BB by CD8+ cells. Activation was coupled with vaccine-associated increase in the frequency of regulatory CD4+ T-lymphocytes.

Conclusion

Vaccination with irradiated autologous tumor cells mixed with GM-K562 cells is feasible, well tolerated, and active in patients with recurrent malignant glioma.

Introduction

Recent clinical research has demonstrated that some patients with advanced malignancies have clinical and radiographic responses to immune checkpoint inhibition with monoclonal antibody-based blockade of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen – 4 (CTLA-4)(1) and the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD1)(2) and its ligand (PD-L1)(3). These clinically impactful immunotherapies come on the heels of Food and Drug Administration approval of Sipleucel T, an autologous cellular vaccine that prolongs survival for patients with advanced castration-resistant prostate cancer(4).

Vaccination with irradiated autologous tumor cells engineered to express granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) – a strategy referred to as “GVAX” - has stimulated vigorous antitumor immunity in subjects with various solid and hematologic malignancies and has prolonged survival in selected patients(5). Vaccination using whole tumor cells drives a polyclonal immune attack against multiple tumor-associated antigens and both reinforces existing humoral and cell-mediated immunity to antigenic epitopes and stimulates new responses to previously undetected tumor-associated antigens.

Glioblastoma is an intracranial malignancy with median overall survival between 14 and 17 months, despite surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy(6, 7). A dire need exists for effective treatments for patients with glioblastoma. Many clinical trials of targeted agents and angiogenesis inhibitors have failed to show efficacy.(8) Bevacizumab is the only FDA -approved drug for patients with recurrent glioblastoma, on the basis of phase II clinical trials showing overall survival of 40 weeks(9).

Despite the blood-brain-barrier, brain tumors interact with the immune system and provoke nascent anti-tumor immune responses. Pallasch has identified antibodies to tumor antigens in the sera of glioblastoma patients and has correlated the presence of a subset of these with prolonged survival(10). Similarly, glioblastoma immunogenicity has been demonstrated by the identification of circulating tumor-specific CD8+ T-lymphocytes amongst the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC’s) of tumor patients. The intratumoral ratio of effector T-lymphocytes to regulatory T-lymphocytes may independently affect survival in glioblastoma patients(11).

Preclinical evidence shows that vaccination can enhance antiglioma immunity and can be effective in intracranial glioma models. In separate reports, Sampson and Herrlinger demonstrated that subcutaneous vaccination with irradiated syngeneic tumor cells expressing cytokines improves survival in mice bearing intracranial tumors. While animals in these studies experienced enhanced survival, the treatments did not cure established tumors. However, vaccination in combination with immune checkpoint blockade has been highly efficacious preclinically(12, 13) and shows promise in early clinical trials(14, 15) in patients with solid tumors. Moving forwards with these combination clinical studies, including for patients with glioma, is a reasonable next step for the field.

The GVAX approach has not been reported in patients with malignant brain tumors. Therefore, prior to proceeding with combination immunotherapy in these patients, we sought to demonstrate the feasibility and safety of vaccinating patients with recurrent malignant glioma with irradiated autologous tumor cells in the context of local GM-CSF expression. The risk of inducing autoimmune encephalitis via autologous whole glioma cell vaccination is a legitimate safety concern. Also, previous efforts at using autologous glioma cell vaccination in this population have shown low feasibility because of tumor progression during vaccine preparation and the challenges inherent to maintaining glioma cells in culture(16).

We mixed irradiated autologous glioma cells with varying numbers of irradiated GM-K562 cells. GM-K562 has been described previously as a GM-CSF producing bystander cell line for use in the formulation of autologous tumor cell-based vaccines(17). The use of a bystander cell line with low immunogenicity allows for in vivo expression of a defined and controllable amount of GM-CSF and permits the design of a true dose-escalation phase I study.

We confirm the feasibility and safety of vaccinating recurrent glioma patients with irradiated autologous tumor cells mixed with up to 1×107 GM-K562 cells. Vaccination engendered an active systemic immune response, as we document enhanced tumor-specific immunity and generalized T-lymphocyte activation.

Methods

The clinical trial protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Dana Farber – Harvard Cancer Center, and is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00694330).

Patients

Patients included adults undergoing elective craniotomy in the setting of recurrent malignant glioma. Full inclusion/exclusion criteria are listed in the supplementary materials.

GM-K562 cells

The GM-K562 cell line was created at the Harvard Gene Vector Laboratory by stably transfecting K562 cells with a plasmid encoding GM-CSF and a puromycin resistance gene. K562 is derived from chronic myelogenous leukemia cells in blast crisis, does not express MHC I and MHC II molecules, and is poorly immunogenic(17, 18). After 100 gray irradiation, GM-K562 cells express 9–13µg of GM-CSF / 1×106 cells / 24 hours.

Clinical Trial Design

This phase I trial was designed in a “3+3” format for examination of the safety of administering up to 1×107 GM-K562 cells mixed with irradiated autologous glioma cells. The first dose cohort was treated with 5 × 106 GM-K562 cells per vaccination. The second cohort (1×107 GM-K562 cells) was expanded in order to treat a total of 10 patients in the study. The number of autologous glioma cells planned per vaccination was a factor of how many were harvested at craniotomy. Vaccines were delivered weekly for 3 weeks, then biweekly, up to a total of 6 vaccinations. Feasibility was defined as the ability to treat ≥60% of enrolled patients with at least 4 vaccinations.

Vaccine Preparation

Autologous tumors were processed into single cell suspension under GMP conditions using collagenase. Cells were aliquoted and cryopreserved at equal number into vials for 6 vaccines, ranging from 1 × 105 cells to 6 × 107 cells. If additional cells were available, two vials of 1×106 cells were set aside for delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) testing.

At time of vaccination, 1 vial of GM-K562 and 1 vial of autologous tumor cells were thawed and extensively washed in saline. Quality control samples were collected for gram stain and sterility evaluation. According to protocol dose, the appropriate number of GM-K562 cells was mixed with the autologous tumor cells, and lethally irradiated at 100 Gray. The vaccine was then delivered to the patient via mixed subcutaneous and intradermal injection.

DTH samples were thawed at time of the first and fourth administration of vaccine, washed extensively in saline, then lethally irradiated at 100 Gray. DTH samples were injected intradermally on the shoulders of consenting subjects.

Immunophenotyping

Immune cell phenotypes in blood were monitored by 5-color flow cytometry. Freshly drawn samples were lysed and stained using monoclonal antibodies specific for T cell co-stimulatory molecules or regulatory T (Treg) cells. The combination of antibodies is listed in the supplementary data. The samples were run on a flow cytometer (FC500 MPL, Beckman Coulter), and data were analyzed using the CXP (Beckman Coulter) software.

ELISA for anti-cytokine antibodies

Details of the ELISA for angiogenic cytokines are as previously described(19),and are also detailed in the supplementary materials.

Biostatistics

Survival analysis was performed by the Kaplan-Meier method. Change in expression of costimulatory molecules and markers on lymphocytes was analyzed by the non-parametric sign-rank test, accounting for small sample size and improbability of normality assumption. P-values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Feasibility

Feasibility was dependent upon the successful harvest and cryopreservation of a sufficient number of viable autologous tumor cells to generate vaccine for 6 injections. The lowest allowable number of tumor cells per vaccination was 1×105, equal to the lowest number of GM-CSF expressing autologous tumor cells associated with biological activity in clinical trials previously conducted at our center. The maximum number of autologous tumor cells per vaccination was set at 6×107, equal to the highest number of GM-CSF expressing tumor cells that had been delivered in the aforementioned studies. Patients had to maintain KPS ≥ 70% until the time of the initial treatment in order to remain study-eligible.

11 patients total were enrolled and underwent craniotomy (Table 1A). Median age was 42 years (range 31- 78).

Table 1.

(A) Clinical characteristics at enrollment for “bystander GVAX” subjects. GBM = glioblastoma; AA = anaplastic astrocytoma, AOA = anaplastic oligoastrocytoma; RT = radiation therapy; TMZ = temozolomide; SRS = stereotactic radiosurgery. (B) Pathology and therapy for “bystander GVAX” subjects undergoing craniotomy for resection of recurrent malignant glioma. N/A = not applicable.

| a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Age | Sex | Initial Diagnosis |

KPS | Time since initial diagnosis (m) |

Recurrence | Pre-op steroids (Y/N?) |

| 1 | 32 | M | GBM | 90 | 12 | 1st | Y |

| 2 | 74 | M | GBM | 70 | 9 | 1st | Y |

| 3 | 31 | M | AA | 100 | 91 | 1st | N |

| 4 | 39 | M | GBM | 90 | 43 | 3rd | N |

| 5 | 63 | M | GBM | 100 | 10 | 1st | N |

| 6 | 42 | F | GBM | 100 | 29 | 3rd | N |

| 7 | AOA | ||||||

| 8 | 51 | M | GBM | 100 | 11 | 1st | N |

| 9 | 32 | M | GBM | 80 | 29 | 3rd | N |

| 10 | 38 | M | GBM | 90 | 18 | 2nd | Y |

| 11 | 78 | M | GBM | 80 | 17 | 1st | N |

| b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Extent of Resection |

Pathology | Viable Tumor cells |

Tumor cells/ vaccination |

Vaccinations received |

Initial Post- vaccination therapy |

| 1 | Subtotal | Glioblastoma | 7.9×107 | 1.2×107 | 6 | Bev/CPT- 11 |

| 2 | Subtotal | Glioblastoma | 1.9×108 | 1.6×107 | 5 | Bev/CPT- 11 |

| 3 | Subtotal | Glioblastoma | 2.0×108 | 3.0×107 | 4 | Bev |

| 4 | Near total | Glioblastoma | 1.6×108 | 2.5×107 | 6 | Bev |

| 5 | Near total | Glioblastoma | 3.0×107 | 4.2×106 | 5 | Bev/CPT- 11 |

| 6 | Near total | Glioblastoma | 9.4×107 | 1.4×107 | 6 | Ang1005 |

| 7 | Gross total | Radiation Necrosis |

N/A | N/A | 0 | |

| 8 | Gross Total |

Glioblastoma | 2.5×108 | 8.2×105 | 6 | None |

| 9 | Gross Total |

Glioblastoma | 5.8×106 | 3.7×107 | 6 | Unknown |

| 10 | Near total | Glioblastoma | 2.5×109 | 3.4×107 |

5 | Sirolimus and Vandetanib |

| 11 | Gross Total |

Glioblastoma | 3.4×107 | 4.80×106 | 6 | Bev |

Sufficient cells were obtained and prepared in 10 of the 11 patients (Table 1B). In a single subject (patient 7), pathology was consistent with treatment effect.

3 patients were enrolled into the first dose cohort (patients 1–3, 5×106 GM-K562 cells per vaccination) and 8 patients into the second (patients 4–11, 1×107 GM-K562 cells per vaccination)

All subjects maintained a KPS of at least 70% after surgery and until the time of the first vaccination. Treatment was initiated at a median of 19.5 days (16–30 days) after craniotomy. All 10 treated patients received at least 4 vaccinations. Patients 1,2, and 3 received 6,5, and 4 vaccinations respectively. Patients 2 and 3 were not treated with the full complement of 6 injections because of radiographic progression of disease and subsequent initiation of bevacizumab. Vaccination of patients undergoing craniotomy for recurrent malignant glioma with a mixture of irradiated autologous tumor cells and GM-K562 cells was deemed feasible by preset criteria.

Safety

All subjects were followed closely for complications associated with vaccine, including adverse neurological effects and autoimmunity. Toxicities were assessed by the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria, version 3.0. Grade 1 and 2 skin reactions were observed at the vaccination sites in all patients, and all resolved spontaneously. There were no grade 3 or 4 toxicities.

The first three patients were treated with 5×106 irradiated GM-K562 cells (50µg GM-CSF / 24 hours) mixed with irradiated autologous tumor cells. There were no dose-limiting toxicities of vaccination in this cohort.

The remaining 7 patients were treated with 1×107 irradiated GM-K562 cells (100µg GM-CSF / 24 hours) mixed with irradiated autologous glioma cells. 5 of 7 treated subjects received 6 vaccinations. 2 of 7 were treated with 5 vaccinations; in both cases, the sixth treatment was held because of concern for progressive disease and initiation of new therapy. There were no dose-limiting toxicities in patients treated at dose-level 2 of GM-K562 cells (1×107 cells).

Patient 5 was evaluated for a low-grade fever and a headache 1 day after initial vaccination. The elevated temperature persisted for 2 days. Work-up included a lumbar puncture, which revealed a mildly elevated protein (124 milligrams/deciliter) and 50 white blood cells (58% polymorphonuclear cells, 27% lymphocytes), possibly consistent with aseptic meningitis. The patient defervesced, and the second vaccination was delayed by one week. Repeat administration of vaccine went forwards without recurrence of fever or headache. This episode was categorized as an adverse event possibly related to treatment, CTC grade 2.

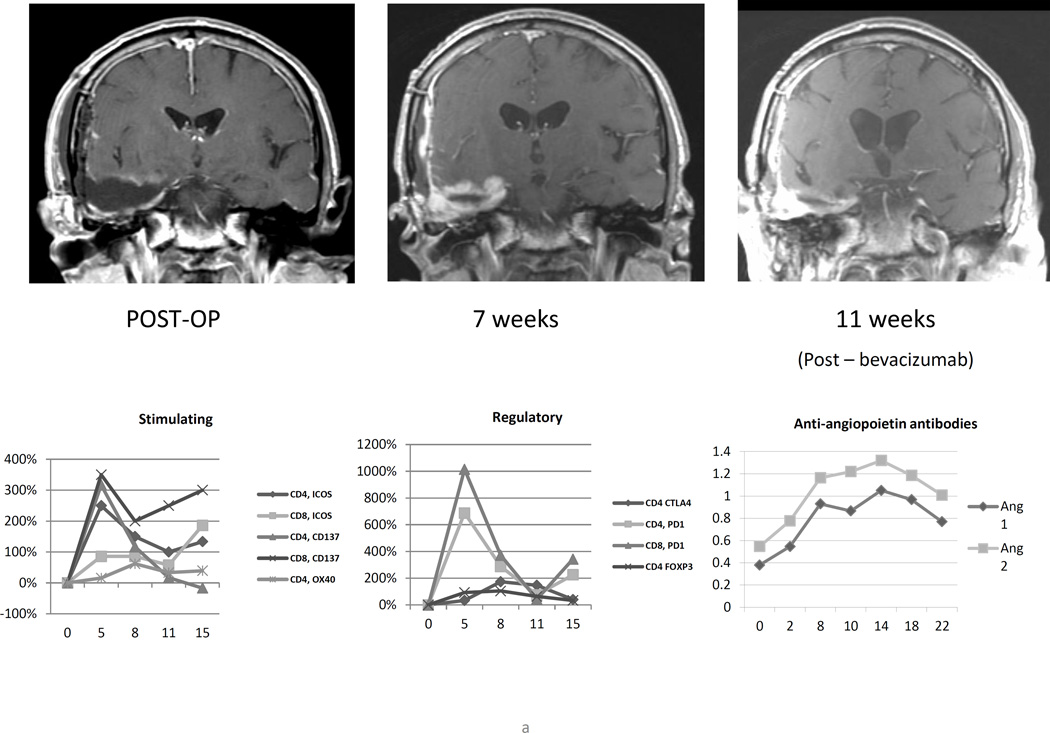

After the 4th vaccination, patient 4 complained of headache and left hemiparesis. Brain MRI showed significant increases in nodular gadolinium enhancement around the right frontal resection cavity and downward mass effect on the lateral ventricles (Figure 3B). Dexamethasone at 4 milligrams daily was initiated with resolution of symptoms, and vaccination continued on schedule. MRI 3 weeks later (week 7 after initiation of therapy) showed reduction in both enhancement and mass effect. Given the presence of central nervous system symptoms that required intervention with oral corticosteroids, this episode is categorized as an adverse event possibly related to therapy, CTC grade 3.

Figure 3.

(A) Serial magnetic resonance imaging of patient 5 demonstrating increased nodular gadolinium enhancement around the resection cavity 7 weeks after initiation of vaccination, shortly after peak T lymphocyte activation and concurrent with rises in plasma antibodies to Ang1 and Ang2. (B) For patient 4, increased gadolinium enhancement at week 4 corresponded with increased expression of T lymphocytes costimulatory molecules and was detected just prior in significant increases to anti-Ang1 and anti-Ang2 antibodies in the patient’s plasma. Dexamethasone was administered and, within 3 weeks, the enhancement had receded.

Toxicity analysis demonstrated that vaccinating patients with subcutaneous and intradermal injections of irradiated autologous glioma cells mixed with up to 1×107 irradiated GM-K562 cells is safe in patients who have undergone craniotomy for recurrent malignant glioma.

Tumor-associated Immunity

Delayed-Type Hypersensitivity

All patients were evaluated for clinical evidence (rash) of vaccination site and DTH reactions between 48 and 72 hours after the first and fourth injections. Consenting patients underwent punch skin biopsies of both vaccination sites and DTH sites, also 48–72 hours after the first and fourth treatments.

Hematoxylin and eosin – stained specimens were evaluated by a senior dermatopathologist who was blinded to patient identification, the dose level, and the timing of the biopsy. The intensity of the inflammatory infiltrates was assessed qualitatively and semi-quantitatively by assignation of a score of 1–4 (+, ++, +++, ++++), with 4 representing the highest degree of inflammation (Details of scoring presented in supplementary data). Results are summarized in Table 2

Table 2.

Semiquantitative assessment of inflammatory responses at punch biopsy sites. GVAX 1,4 = vaccination site biopsies 48–72 hours after 1st and 4th treatments respectively; DTH 1,4 = DTH-site biopsies 48–72 hours after 1st and 4th treatments respectively; ND = not done; eos = eosinophils.

| Patient | GVAX 1 | GVAX 4 | DTH 1 | DTH 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ND | + | Negative | +++ |

| 2 | +++ | +++ | Trace | ++, Eos |

| 4 | ND | +++ | ND | +++ |

| 5 | Focal ++, Eos |

ND | Trace | ND |

| 6 | ++ | ++++ | Negative | ++ |

| 9 | Trace | + | Negative | Negative |

| 11 | ++ | ++++, eos | + | +++, Eos, and Neutrophils |

There was a strong trend towards enhanced histopathologically detectable inflammation at the time of the fourth vaccination as compared to the biopsy sites at the time of the first treatment. This was true at the vaccination sites themselves, but was particularly marked at the biopsied DTH sites. At the time of the first vaccination, there was essentially no inflammatory response to intradermal injection of irradiated autologous tumor cells into the shoulder contralateral to the vaccination site. 48–72 hours after the fourth vaccination, however, clear increases in the intensity of inflammatory cell infiltrates were observed in the DTH punch biopsy specimens of all patients except for patient 9..

Histology examination of DTH sites suggested that by the time of the fourth treatment, vaccination with irradiated autologous glioma cells mixed with irradiated GM-K562 cells has augmented a systemic immune response against the patients’ tumor cells.

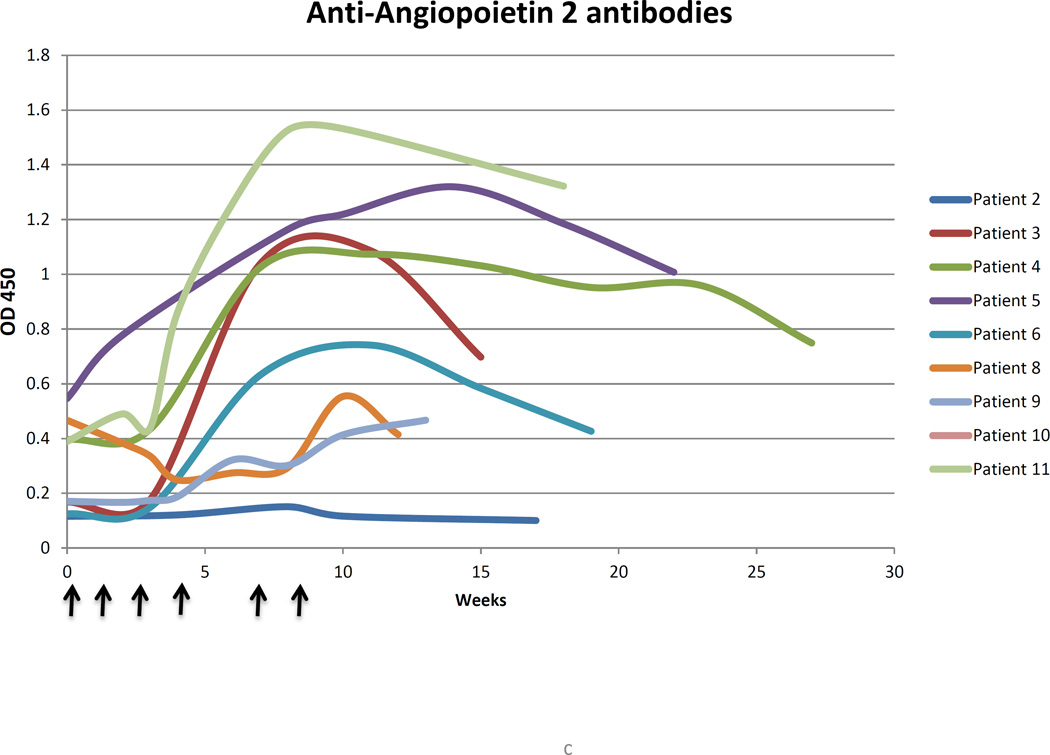

Humoral Antitumor Immunity

To address the lack of antigen-specific immune monitoring associated with our whole cell approach, we extended findings from our group that cancer patients treated with GVAX alone(19) or in combination with CTLA-4 blockade(20) generate antibodies against multiple cytokines associated with tumor angiogenesis, including angiopoietins 1 and 2, as well as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). We established an ELISA panel of angiogenic cytokines and peptides and analyzed reactivity with patient plasma. We studied plasma reactivity to L1-CAM, DEL-1, Angiopoietin 1 (Ang 1), Angiopoietin 2 (Ang 2), Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF), Platelet Derived Growth Factor (PDGF-BB), Progranulin (PGLN), and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor, as our prior work indicated that each may be the target of vaccine-induced antibodies. Peak changes in plasma reactivity to these cytokines, measured by optical density (OD), are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Semiquantitative analysis of antibody response to angiogenic cytokines in vaccinated patients with recurrent malignant glioma. Patients 2,3,4, 5, and 11 received bevacizumab at weeks 7,6,10,10, and 10 respectively.

| Patient number |

L1 | DEL-1 | Ang1 | Ang2 | HGF | PDGF | VEGF-A* | VEGF-A | PGRN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | + | + | +++ | ||||||

| 3 | + | +++ | + | + | +++ | + | |||

| 4 | ++ | +++ | +++ | + | + | +++ | |||

| 5 | ++ | +++ | +++ | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | ||

| 6 | +++ | + | + | ||||||

| 8 | + | + | + | + | |||||

| 9 | +++ | + | |||||||

| 10 | + | +++ | ++ | +++ | |||||

| 11 | ++ | +++ | + | + | + | + |

Note: +, two and one half to 5-fold increases; ++ 5- to 7-fold increases; +++, 8- and greater fold increases

VEGF-A before bevacizumab. Patients 2–5 had blood sampled after bevacizumab administration

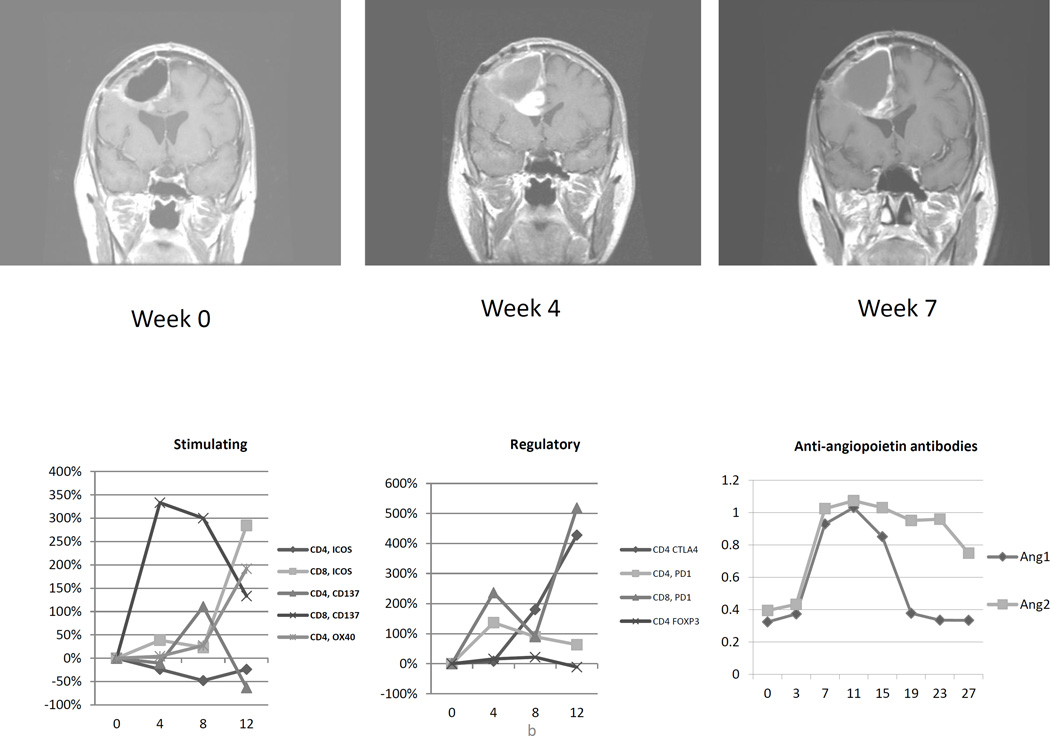

Vaccination increased antibody responses most consistently and significantly to Ang 1 (4/9 patients), Ang 2 (7/9 patients), HGF (6/9 patients), and PDGF (5/9 patients). Changes above baseline were compared to background levels in the assay, and ranged from a minimum of 2.5-fold elevations to more than eight-fold increases. Increases in response were most vigorous for Ang 2. Reactivity tended to peak towards the end of the vaccination course or after it was complete (Figure 1). In patients 3,4, and 5, peak responses to Ang 2 were most intense after commencement of treatment with bevacizumab, which started on weeks 6, 10, and 10 respectively, possibly reflecting an immunostimulatory effect of VEGF-A blockade, consistent with prior studies of combined bevacizumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma patients.(21)

Figure 1.

(A) Measured absorbance of patient plasma in ELISA assay against angiopoietins 1 (Ang1) and 2 (Ang2) vs. week from the time of initial vaccination in patients with recurrent malignant glioma. The blue dashed vertical lines denote the timepoint of the last dose of vaccine per patient.

The aggregate time course and magnitude of anti-Ang1 antibodies (B) and anti-Ang2 antibodies (C) are represented. Vaccinated patient plasma more consistently registered responses to Ang2 peptide, and these were typically of greater intensity than responses to Ang1. Arrows denote delivery of vaccine.

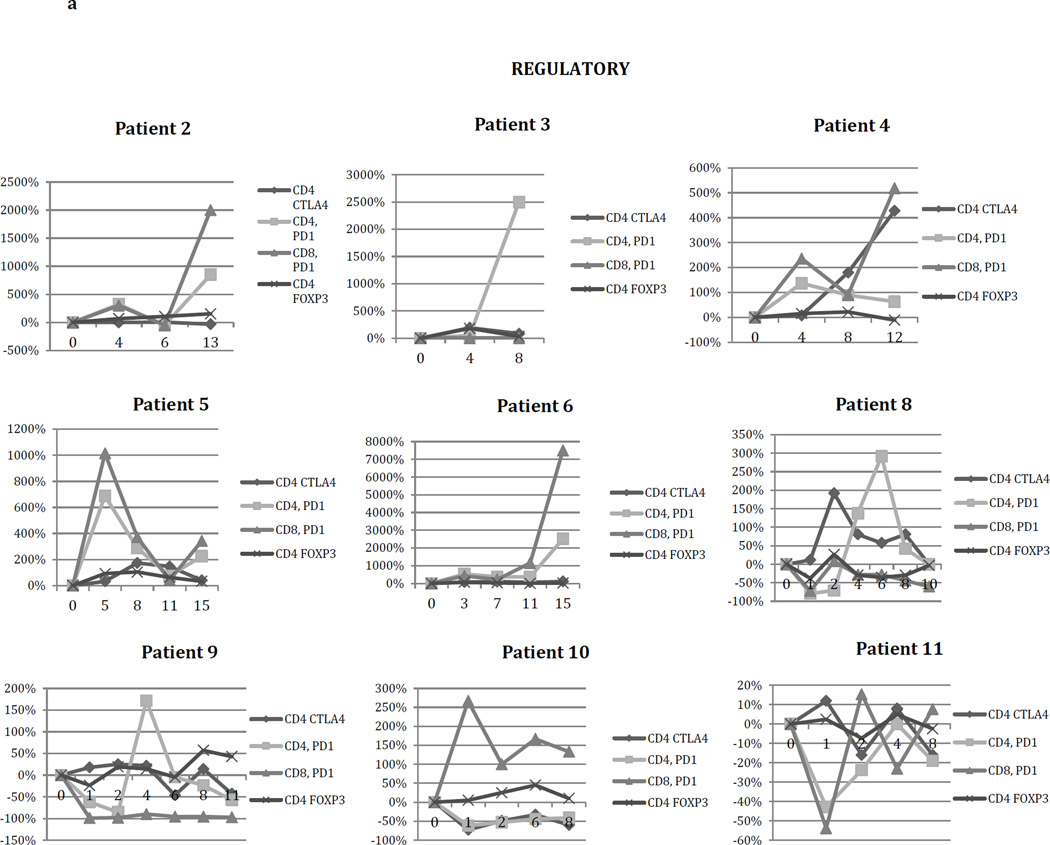

T-lymphocyte Activation

Flow cytometry of leukocyte subsets reveals post-vaccination T lymphocyte activation

We sought to identify trends in vaccination-associated leukocyte activation by performing flow cytometry of white blood cell subsets, using freshly collected whole blood. The full flow cytometry panel is shown in the supplementary data. Expression levels for each marker were followed over time. We calculated the maximum percentage change as compared to the levels measured from blood collected at the time of the initial vaccination, as not all subjects had whole blood processed prior to treatment. We limited our analysis to blood that was collected within the first 12 weeks after vaccination, in order to avoid confounding of data by the impact of additional therapies.

For many of the cellular subsets, there were no distinguishable patterns of change, including in natural killer (NK) cells, NKT cells, and dendritic cell subsets. However, with regard to systemic CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocyte activation, several trends, some of which were statistically significant and temporally related to vaccine initiation, emerged.

We identified changes in the expression of “activating” and “regulatory” co-stimulatory molecules by both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes. Upregulation of these molecules is an indication of initial T-cell activation, and their ligation may be associated with further expansion of lymphocyte proliferation and memory differentiation (“activating”) or fatigue and downregulation of antigen specific immune responses (“regulatory”).

Sufficient blood for flow cytometry analysis was collected in subjects 2,3,4,5,6,8,9,10, and 11. We measured lymphocyte expression of ICOS, CD137, and OX40 (activating); also, as regulatory costimulatory molecules, we examined T-lymphocyte expression of CTLA4 (CD4+ lymphocytes) and PD1, as well as FoxP3 expression on CD4+ cells. Expression of FoxP3 on CD4+ lymphocytes serves as an identifier of the suppressive regulatory T cell (Treg) subset, though it also may be present on some activated conventional T cells.

CTLA-4 expression on CD4+ lymphocytes clearly increased relative to levels at the beginning of vaccination, typically within the first 10 weeks after the initial vaccination. Peak expression of CTLA-4 for one patient (Patient 4), occurred at the 12th week, and the relative increase was particularly high (>5×). There was a clear trend for increased CTLA-4 expression on CD4+ lymphocytes over the course of the vaccination period, with the peak occurring after 7–8 weeks, typically followed by subsequent decline.

Similarly, in 9 of 11 patients, CD4+ T-lymphocyte expression of PD1 generally increased over time after vaccination. While most patients demonstrated peak PD1 expression by CD4+ T lymphocytes between 4 and 6 weeks with a subsequent decline, 3 patients had marked elevations in PD1 expression (9.5×, 26×, and 26.2×) in a delayed fashion (12,12, and 15 weeks after initiation of vaccination).

The percentage of CD4+FoxP3+ T lymphocytes frequently increased after the start of treatment, often peaking, then declining (e.g. patients 3,4,5,6,8, and 10).

Activating co-stimulatory molecules were upregulated in their expression on CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes after vaccination as well. Baseline levels of T-lymphocyte expression of CD137 (4-1BB) were low in these patients. However, both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes more frequently expressed CD137 post-vaccination than at the outset. OX40 expression on CD4+ T lymphocytes was also driven upwards.

We quantified and depicted the change in CD4 lymphocyte expression for Foxp3 and the above T-lymphocyte co-stimulatory molecules (Figure 2). Statistically significant changes were identified for CD4CTLA4, CD4PD1, CD4FoxP3, CD4CD137, CD8CD137, and CD4OX40. The change in expression of PD1 on CD8+ T-lymphocytes trended upwards, but did not achieve statistical significance because of wide variation (Supplementary Data).

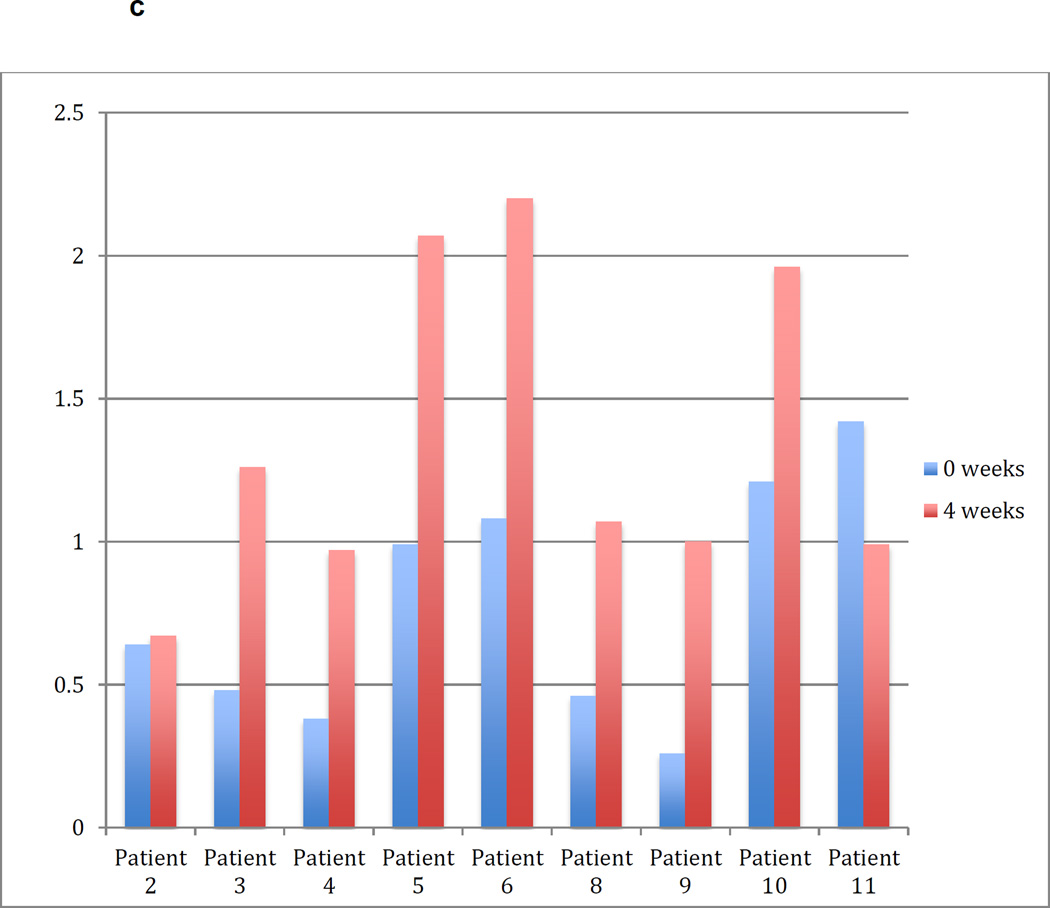

Figure 2.

Per cent change in blood lymphocyte expression of (A) negative regulatory co-stimulatory molecules and FoxP3 (CD4+) and of (B) costimulatory molecules associated with immune intensification vs. weeks after first treatment in vaccinated patients with recurrent malignant glioma. Maximal changes in costimulatory molecule expression varied in timing and significance. X-axes reflect weeks after initiation of therapy.

(C) Frequency of CD4+CD25+CD127- T lymphocytes at the initiation of vaccination (week 0) and 4 weeks later. (D) Percent change in the frequency of CD4+CD25+CD127- T lymphocytes between weeks 0 and 4 of treatment. Red color reflects percentage decrease.

CD4+CD25+CD127- regulatory T lymphocytes

While FoxP3 expression is commonly used to define CD4+ regulatory T cells, it is also transiently expressed as an activation marker on conventional CD4+ T cells. The CD4+CD25+CD127- subset correlates tightly with FoxP3 -expressing regulatory T lymphocytes and can be used as an alternative marker. By 4 weeks after initiation of vaccination, 7 of 9 patients had marked increases in the percentage of these cells within the CD4+ compartment, ranging from 162% – 385%, providing further indication that vaccination with irradiated autologous glioma cells mixed with GM-K562 cells rapidly induces regulatory T-lymphocyte differentiation or systemic mobilization (Figure 2C and 2D).

Survival

By the MacDonald17,criteria, each patient progressed radiographically by the time of the first post-treatment MRI (7–9 weeks). For all patients, median overall survival was 35 weeks (range 21–92). Median overall survival for the 7 patients treated with 1×107 GM-K562 cells was 53 weeks, (range 30–92). Survival was not statistically associated with any of the immune parameters studied.

Case Examples

The small number of patients treated in this phase I study and the heterogeneous clinical presentations preclude meaningful analyses of associations between measured immune parameters and outcome. However, patients 4 and 5 reflect how clinical and radiographic responses may correlate with changes in cellular and humoral immune responses in glioma patients undergoing autologous tumor cell vaccination.

Patient 5

Patient 5 was a 62 year-old man treated with craniotomy, radiation, and temozolomide chemotherapy who presented with nodular enhancement involving and surrounding his prior resection cavity in the right temporal lobe. He was enrolled on the vaccination protocol, and underwent near-total resection of the mass. Substantial numbers of viable tumor cells were harvested and vaccination was initiated, off of corticosteroids, 19 days post-operatively. As described previously, he presented with fever 1 day after the first vaccination. The second treatment was postponed by 1 week, without recurrent fever. After the fifth vaccination (week 7.5), a regularly scheduled MRI demonstrated nodular enhancement, thought to be consistent with disease progression, and bevacizumab/irinotecan was started. While brain MRI at this point showed that the volume of gadolinium-enhancing tissue was increased, cerebral blood volume values and metabolites on MR spectroscopy were decreased, suggestive of treatment-associated changes.

Early imaging response after bevacizumab/irinotecan treatment showed reduced enhancement, which remained stable for more than a year until shortly before he passed away from progressive disease, 21 months after initiation of vaccination.

We retrospectively examined the patient’s immune responses. At week 5 after vaccine initiation – the time of the 4th vaccine injection – there was brisk upregulation of activating and regulatory co-stimulatory molecules on both CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes in the peripheral blood (Figure 3a). The synchronous increase in CD4+FoxP3+ regulatory T-lymphocytes was relatively modest. Subsequently, ELISA of the patient’s plasma revealed a brisk rise in humoral responses to angiopoietins 1 and 2, as well as HGF, PDGF, and Progranulin. These elevated responses began prior to the initiation of bevacizumab/irinotecan at week 9, peaked at week 14 after vaccination began, then persisted and partially subsided. Heightened lymphocyte activation, rising antitumor antibody titers, and advanced MR imaging suggestion of treatment effect raise the possibility that the week 7 scan represented pseudoprogression and that the durable tumor control that followed was related to systemic antitumor immunity.

Patient 4

Patient 4’s clinical course has been detailed in this report in the section on safety of vaccination. During the fifth week, neurological deterioration lead to an MRI, which demonstrated new nodular enhancement with mass effect. DTH analysis at week 5 revealed intense inflammatory infiltrates. Similarly, there was broad CD4+ and CD8+ T -lymphocyte activation with markedly increased expression of PD1, CTLA-4, CD137, and ICOS (Figure 3b). The relative increase in the percentage of CD4+Foxp3+ cells was, as was the case for patient 5, modest. Patient 4 developed antibodies to multiple angiogenic cytokines, particularly against angiopoietin 1 and angiopoietin 2. These antitumor antibody titers continued to rise until week 14. The strength and polyvalence of the immune response at week 5 and beyond supports our retrospective belief that the synchronous MRI was an example of vaccine-induced pseudoprogression. Subsequent MRI’s are difficult to interpret because of treatment with bevacizumab.

Discussion

In this phase I study, we have achieved the primary objectives of demonstrating safety and feasibility of combining autologous irradiated glioblastoma cells with up to 1 × 107 GM- K562 cells as vaccination in patients that had undergone craniotomy for recurrent tumor. Feasibility was readily achieved, and there were no serious adverse events. Feasibility is a highly relevant issue for cellular glioma immunotherapy, particularly for patients with recurrent disease. In a study examining the use of autologous glioma cells alongside patient fibroblasts engineered to express IL-4(16), most enrolled patients did not receive treatment because of disease progression or clinical decline prior to initiation of therapy. Similarly, in a recent phase I study of vaccination of patients undergoing craniotomy for recurrent glioblastoma with autologous tumor-derived peptides bound to the 96 kilodalton chaperone protein derived from the tumor specimens(22), only 12 of 28 enrolled patients were ultimately treated. Patient dropout was secondary to inadequate harvest of viable tumor in 9 patients and progression or clinical deterioration prior to full vaccine administration in 4 patients. In our series, the GM-K562 bystander line facilitated the ready capacity to make vaccine and allowed rapid postoperative turnaround without the need to culture or genetically manipulate harvested specimens.

Consistent with other approaches to glioma immunotherapy(23), there was no evidence of autoimmunity or encephalitis. This is significant for the use of autologous whole glioma cell vaccination, as, while the tumor specimens undergo enzymatic digestion and mechanical separation, there is no process by which normal glial or neuronal elements are excluded, and they may be included in the product.

Clinical use of GM-K562 cells as bystander producers of GM-CSF has been reported previously in the context of vaccination of patients with advanced lung cancer(24, 25) and in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)(25). In the CLL study, 22 subjects were treated with irradiated autologous tumor cells mixed with 1 × 107 GM-K562 cells without adverse events. Vaccination led to development of systemic tumor-specific T-cell responses.

Whole glioma cell vaccination has been examined previously, but not in a manner consistent with GVAX. Plautz, et al. reported adoptive T-lymphocyte transfer in glioblastoma patients, using cells harvested from inguinal lymph nodes harvested 8 – 10 days after a single subcutaneous injection of irradiated autologous tumor cells mixed with 500 micrograms of recombinant GM-CSF(25). More recently, Ishikawa described safe treatment with autologous formalin-fixed tumor vaccine in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma(26). To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first report of the GVAX approach in patients with malignant gliomas.

Pseudoprogression by MRI is a well-known entity in glioblastoma imaging(27) and may be relevant in patients treated with immunotherapy as well. In other solid tumors, standard CT-based imaging criteria such as RECIST have been misleading, and an alternative set of immune response assessment criteria have been promoted(28). We saw early appearance of new gadolinium enhancement on MRI in some patients, followed by subsequent radiographic regression and/or lengthy stabilization of disease. Improved ability to differentiate tumor progression from toxic or inflammatory changes will help practitioners understand which patients are responding to treatment and which patients should be directed towards another therapy. It is worth noting that in the two patient cases described in this report, while the MRI’s and/or the clinical scenarios suggested progression, the accompanying immune studies showed treatment-driven activation, including improved ratios of activated T lymphocytes to regulatory T lymphocytes. It is possible that immune parameters or biomarkers will be more predictive of early response than standard imaging. Also, a relatively delayed onset of effective antitumor activity has been observed previously in cancer vaccination, including in the phase 3 demonstration that Sipleucel-T improved overall survival in patients with advanced hormone-refractory prostate cancer, but did not change progression free survival. As immunotherapy evolves and becomes more effective in patients with brain tumors, management of inflammatory toxicity may have to move away from the use of corticosteroids, which can downregulate T cell responses.

The tracking of relevant biomarkers for assessment of cancer immunotherapies is a complex and dynamic process; the efficacy of the antitumor response is ultimately dependent upon interactions between variable factors related to the host, the tumor itself, and the treatments in question, in addition to any other therapies that may be used in combination or sequentially. Evaluation of DTH sites provides a straightforward assessment of the biological activity of any immunotherapy. In these glioma patients, histology evaluation of punch biopsies of DTH injection sites consistently demonstrated intensification of an inflammatory response within the irradiated tumor deposits after 4 vaccinations. This response was fully lacking in each patient at the time of the first vaccination, prior to the onset of biological effect of the vaccine. DTH studies assess systemic immunoreactivity to a given patient’s tumor within the physical context of the host; however, they do not necessarily represent interactions within the actual tumor milieu and do not provide information about immune cellular function. With further progress in the field of glioma immunotherapy, stereotactic biopsy of the actual tumor sites may become necessary if imaging and serologic biomarkers of response are not consistently representative of antitumor effect.

Lymphocytes are effectors of adaptive antitumor immunity, and analysis of their differentiation and activation status, both as snapshots and over time, may provide associations with responses to immunotherapy. (29),(30),(31) For better understanding of biomarkers and predictors of immune and clinical response in glioma patients, many more patients will have to be treated, including a significant fraction with clinical responses.

In our patients, vaccination with irradiated autologous tumor cells mixed with GM-K562 cells seemed to impact the activation status of T lymphocytes, particularly in the CD4+ subset. While activation of T lymphocytes requires major histocompatibility complex engagement of the T-cell receptor coupled by CD80 or 86 binding of CD28(32), numerous subsequent interactions occur at the APC/T-cell interface that fine-tune the immune response; some are associated with further activation and clonal proliferation, while others are associated with homeostatic negative immune regulation. We have demonstrated statistically significant increases of CD4+ T lymphocyte expression of CTLA-4, PD-1, OX40, and CD137 within 12 weeks of vaccination initiation. CD8+ T-lymphocyte expression of CD137 was significantly increased and many patients saw elevations in PD-1 expression by CD8+ T lymphocytes as well. Overall, these alterations imply a general treatment-associated activation of peripheral lymphocyte responses that peaks after several rounds of vaccination have occurred. We also observed increased frequency of regulatory T-lymphocytes within the CD4+ compartment, a phenomenon which has been described in preclinical models of GM-CSF-expressing irradiated autologous tumor cells(33) and, clinically, in ipilimumab + GM-CSF combination therapy(31). The efficacy of therapy may ultimately depend upon the change in the ratio of effector T-lymphocytes to regulatory T-lymphocytes(15), intratumorally and systemically; we did not collect absolute lymphocyte counts, which precludes precise calculation of these numbers. Nevertheless, it may be beneficial to combine vaccination with agents that counteract regulatory T-lymphocyte activity or suppress their induction, which is partially dependent on GM-CSF levels(34). Furthermore, GM-CSF expression in cancer vaccines has been shown to increase the number of circulating and intratumoral myeloid derived suppressor cells. (35) Combining vaccination with VEGF inhibition may be a way to strengthen antitumor immunity by reduction of MDSC induction.(36) Likewise, co-administration of toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands along with GM-CSF expressing vaccines may reverse MDSC induction and further promote anti-tumor immunity, driving stronger responses .(37) In some clinical studies, however, GVAX immunotherapy has lead to a reduction in circulating MDSCs.(38) The relationship between GM-CSF expression and immunoregulatory mechanisms requires further study.

The time-dependent elevated expression of co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory molecules on the T-lymphocyte surface may highlight the optimal points at which to administer “checkpoint-active” therapies after vaccination. Along these lines, in a murine intracranial glioma model, we have demonstrated synergistic efficacy following syngeneic GM-CSF expressing tumor cell vaccination with CTLA-4 blockade(12). In these studies, sequential delivery of these immunotherapies provoked stronger antitumor effect than giving them concurrently (unpublished data). Blockade of PD-1 function(39) and agonist ligation of OX-40(40) and 4-1BB (CD137)(41) have shown promising activity in combination with vaccination in preclinical glioma models. Vaccine-associated activation and upregulation of these “druggable” targets on T lymphocytes may provide an opportunity for increasing the efficacy of these therapeutics.

Measuring T-lymphocyte activation, as above, does not clarify the antigen-specificity of the response. A whole-tumor cell approach creates a challenge for antigen-specific immunomonitoring. The CD137 expressing subset of T-lymphocytes has been shown to harbor specifically activated cells, and may serve as a means of identifying the repertoire of the antigen-specific cells amidst a heterogeneous population(42).

Our assay of humoral responses to angiogenic cytokines has the potential to provide immunomonitoring across cancer types and immunotherapies. Amongst vaccinated glioblastoma patients, we revealed increases in antibody titers to angiopoietins 1 and 2 amongst other angiogenic cytokines. These antibody responses were not detectable prior to vaccination. The induction of antibody responses to angiogenic cytokines may have several ramifications. Fundamentally, this illustrates the vaccine-driven presence of humoral antitumor immunity, in temporal coordination with the T-lymphocyte activation catalogued by immunophenotyping studies. Schoenfeld demonstrated that sera of vaccinated cancer patients with detectable antibodies to angiogenic cytokines exhibits functional angiogenesis inhibition in vitro(20). Vaccinated leukemia patients with early development of antibodies to two or more angiogenic cytokines saw improved survival compared to those with measureable detection of one or fewer cytokines on the same panel. Angiogenic cytokines, including angiopoietins, may inhibit immune function, and their blockade may thereby further enhance intratumoral lymphocyte infiltration, leading to increased antitumor cytotoxic effect and subsequent immunogenicity. The immune targeting of multiple angiogenic proteins may allow synergy with current angiogenesis inhibitors. The mechanism by which this vaccine-induced targeting of the tumor vasculature occurs and its therapeutic consequences requires further investigation, but supports the rationale for combination approaches with autologous cell-based vaccination and angiogenesis inhibitors.

In summary, vaccination of patients undergoing craniotomy for recurrent malignant glioma with irradiated autologous tumor cells mixed with GM-K562 cells was feasible and safe. Via histology evaluation of delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions, phenotypic demonstration of T-lymphocyte activation, and the identification of elevated titers of antibodies to angiogenic cytokines, “bystander GVAX” vaccination has biological activity in these patients, and we have strengthened the rationale for a variety of combination approaches. These strategies may include augmenting vaccination with monoclonal antibodies targeting T-lymphocyte co-stimulatory molecules, agents that suppress regulatory T-lymphocytes, and inhibitors of angiogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: William Curry, MD was partially supported by a grant from the Harold Amos Faculty Development Program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: none relevant

References

- 1.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. PubMed PMID: 20525992; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3549297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Grob JJ, Cowey CL, Lao CD, et al. Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab or Monotherapy in Untreated Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(1):23–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504030. PubMed PMID: 26027431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sunshine J, Taube JM. PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2015;23:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2015.05.011. PubMed PMID: 26047524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, Berger ER, Small EJ, Penson DF, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(5):411–422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001294. PubMed PMID: 20818862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dranoff G. GM-CSF-secreting melanoma vaccines. Oncogene. 2003;22(20):3188–3192. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206459. PubMed PMID: 12789295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, Hamou MF, de Tribolet N, Weller M, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):997–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043331. PubMed PMID: 15758010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilbert MR, Dignam JJ, Armstrong TS, Wefel JS, Blumenthal DT, Vogelbaum MA, et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):699–708. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308573. PubMed PMID: 24552317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jahangiri A, De Lay M, Miller LM, Carbonell WS, Hu YL, Lu K, et al. Gene expression profile identifies tyrosine kinase c-Met as a targetable mediator of antiangiogenic therapy resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(7):1773–1783. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1281. PubMed PMID: 23307858; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3618605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vredenburgh JJ, Desjardins A, Herndon JE, Marcello J, Reardon DA, Quinn JA, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(30):4722–4729. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2440. PubMed PMID: 17947719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pallasch CP, Struss AK, Munnia A, König J, Steudel WI, Fischer U, et al. Autoantibodies against GLEA2 and PHF3 in glioblastoma: tumor-associated autoantibodies correlated with prolonged survival. Int J Cancer. 2005;117(3):456–459. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20929. PubMed PMID: 15906353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sayour EJ, McLendon P, McLendon R, De Leon G, Reynolds R, Kresak J, et al. Increased proportion of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in tumor infiltrating lymphocytes is associated with tumor recurrence and reduced survival in patients with glioblastoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1651-7. PubMed PMID: 25555571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agarwalla P, Barnard Z, Fecci P, Dranoff G, Curry WT. Sequential immunotherapy by vaccination with GM-CSF-expressing glioma cells and CTLA-4 blockade effectively treats established murine intracranial tumors. J Immunother. 2012;35(5):385–389. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3182562d59. PubMed PMID: 22576343; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3352987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quezada SA, Peggs KS, Curran MA, Allison JP. CTLA4 blockade and GM-CSF combination immunotherapy alters the intratumor balance of effector and regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(7):1935–1945. doi: 10.1172/JCI27745. PubMed PMID: 16778987; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1479425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh H, Madan R, Dahut W. Genitourinary Cancers Symposium. Vol. 26. Orlando: Florida; 2015. Feb, al. e. Combining active immunotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors in prostate cancer. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hodi FS, Butler M, Oble DA, Seiden MV, Haluska FG, Kruse A, et al. Immunologic and clinical effects of antibody blockade of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 in previously vaccinated cancer patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(8):3005–3010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712237105. PubMed PMID: 18287062; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2268575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okada H, Lieberman FS, Walter KA, Lunsford LD, Kondziolka DS, Bejjani GK, et al. Autologous glioma cell vaccine admixed with interleukin-4 gene transfected fibroblasts in the treatment of patients with malignant gliomas. J Transl Med. 2007;5:67. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-5-67. PubMed PMID: 18093335; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2254376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borrello I, Sotomayor EM, Cooke S, Levitsky HI. A universal granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-producing bystander cell line for use in the formulation of autologous tumor cell-based vaccines. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10(12):1983–1991. doi: 10.1089/10430349950017347. PubMed PMID: 10466632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burkhardt UE, Hainz U, Stevenson K, Goldstein NR, Pasek M, Naito M, et al. Autologous CLL cell vaccination early after transplant induces leukemia-specific T cells. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(9):3756–3765. doi: 10.1172/JCI69098. PubMed PMID: 23912587; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3754265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piesche M, Ho VT, Kim H, Nakazaki Y, Nehil M, Yaghi NK, et al. Angiogenic cytokines are antibody targets during graft-versus-leukemia reactions. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(5):1010–1018. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1956. PubMed PMID: 25538258; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4348150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schoenfeld J, Jinushi M, Nakazaki Y, Wiener D, Park J, Soiffer R, et al. Active immunotherapy induces antibody responses that target tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2010;70(24):10150–10160. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1852. Epub 2010/12/17. PubMed PMID: 21159637; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc3057563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hodi FS, Lawrence D, Lezcano C, Wu X, Zhou J, Sasada T, et al. Bevacizumab plus ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2(7):632–642. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0053. PubMed PMID: 24838938; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4306338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crane CA, Han SJ, Ahn B, Oehlke J, Kivett V, Fedoroff A, et al. Individual patient-specific immunity against high-grade glioma after vaccination with autologous tumor derived peptides bound to the 96 KD chaperone protein. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(1):205–214. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3358. PubMed PMID: 22872572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reardon DA, Freeman G, Wu C, Chiocca EA, Wucherpfennig KW, Wen PY, et al. Immunotherapy advances for glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16(11):1441–1458. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou212. PubMed PMID: 25190673; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4201077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nemunaitis J, Jahan T, Ross H, Sterman D, Richards D, Fox B, et al. Phase 1/2 trial of autologous tumor mixed with an allogeneic GVAX vaccine in advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 2006;13(6):555–562. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700922. PubMed PMID: 16410826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Creelan BC, Antonia S, Noyes D, Hunter TB, Simon GR, Bepler G, et al. Phase II trial of a GM-CSF-producing and CD40L–expressing bystander cell line combined with an allogeneic tumor cell-based vaccine for refractory lung adenocarcinoma. J Immunother. 2013;36(8):442–450. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3182a80237. PubMed PMID: 23994887; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3846277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishikawa E, Muragaki Y, Yamamoto T, Maruyama T, Tsuboi K, Ikuta S, et al. Phase I/IIa trial of fractionated radiotherapy, temozolomide, and autologous formalin-fixed tumor vaccine for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J Neurosurg. 2014;121(3):543–553. doi: 10.3171/2014.5.JNS132392. PubMed PMID: 24995786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jahangiri A, Aghi MK. Pseudoprogression and treatment effect. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2012;23(2):277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2012.01.002. viii-ix. PubMed PMID: 22440871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolchok JD, Hoos A, O’Day S, Weber JS, Hamid O, Lebbé C, et al. Guidelines for the evaluation of immune therapy activity in solid tumors: immune-related response criteria. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(23):7412–7420. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1624. PubMed PMID: 19934295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fong B, Jin R, Wang X, Safaee M, Lisiero DN, Yang I, et al. Monitoring of regulatory T cell frequencies and expression of CTLA-4 on T cells, before and after DC vaccination, can predict survival in GBM patients. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e32614. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032614. PubMed PMID: 22485134; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3317661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santegoets SJ, Stam AG, Lougheed SM, Gall H, Scholten PE, Reijm M, et al. T cell profiling reveals high CD4+CTLA-4 + T cell frequency as dominant predictor for survival after prostate GVAX/ipilimumab treatment. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62(2):245–256. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1330-5. PubMed PMID: 22878899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwek SS, Lewis J, Zhang L, Weinberg V, Greaney S, Harzstark A, et al. Pre-existing levels of CD4 T cells expressing PD-1 are related to overall survival in prostate cancer patients treated with ipilimumab. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015 doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0227. PubMed PMID: 25968455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwartz RH. Costimulation of T lymphocytes: the role of CD28, CTLA-4, and B7/BB1 in interleukin-2 production and immunotherapy. Cell. 1992;71(7):1065–1068. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80055-8. PubMed PMID: 1335362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.LaCelle MG, Jensen SM, Fox BA. Partial CD4 depletion reduces regulatory T cells induced by multiple vaccinations and restores therapeutic efficacy. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(22):6881–6890. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1113. PubMed PMID: 19903784; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2784281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jinushi M, Nakazaki Y, Dougan M, Carrasco DR, Mihm M, Dranoff G. MFG-E8-mediated uptake of apoptotic cells by APCs links the pro- and antiinflammatory activities of GM-CSF. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(7):1902–1913. doi: 10.1172/JCI30966. PubMed PMID: 17557120; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1884688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Serafini P, Carbley R, Noonan KA, Tan G, Bronte V, Borrello I. High-dose granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-producing vaccines impair the immune response through the recruitment of myeloid suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64(17):6337–6343. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0757. PubMed PMID: 15342423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guislain A, Gadiot J, Kaiser A, Jordanova ES, Broeks A, Sanders J, et al. Sunitinib pretreatment improves tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte expansion by reduction in intratumoral content of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in human renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2015;64(10):1241–1250. doi: 10.1007/s00262-015-1735-z. PubMed PMID: 26105626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fernández A, Oliver L, Alvarez R, Fernández LE, Lee KP, Mesa C. Adjuvants and myeloid-derived suppressor cells: enemies or allies in therapeutic cancer vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(11):3251–3260. doi: 10.4161/hv.29847. PubMed PMID: 25483674; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4514045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lipson EJ, Sharfman WH, Chen S, McMiller TL, Pritchard TS, Salas JT, et al. Safety and immunologic correlates of Melanoma GVAX, a GM-CSF secreting allogeneic melanoma cell vaccine administered in the adjuvant setting. J Transl Med. 2015;13:214. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0572-3. PubMed PMID: 26143264; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4491237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeng J, See AP, Phallen J, Jackson CM, Belcaid Z, Ruzevick J, et al. Anti-PD-1 blockade and stereotactic radiation produce long-term survival in mice with intracranial gliomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;86(2):343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.12.025. Epub 2013/03/07. PubMed PMID: 23462419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schreiber TH, Wolf D, Bodero M, Gonzalez L, Podack ER. T cell costimulation by TNFR superfamily (TNFRSF)4 and TNFRSF25 in the context of vaccination. J Immunol. 2012;189(7):3311–3318. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200597. Epub 2012/09/08. PubMed PMID: 22956587; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc3449097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin X, Zhou C, Wang S, Wang D, Ma W, Liang X, et al. Enhanced antitumor effect against human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) by vaccination with chemotactic-hTERT gene-modified tumor cell and the combination with anti-4-1BB monoclonal antibodies. Int J Cancer. 2006;119(8):1886–1896. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22048. Epub 2006/05/19. PubMed PMID: 16708388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolfl M, Kuball J, Ho WY, Nguyen H, Manley TJ, Bleakley M, et al. Activation-induced expression of CD137 permits detection, isolation, and expansion of the full repertoire of CD8+ T cells responding to antigen without requiring knowledge of epitope specificities. Blood. 2007;110(1):201–210. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-056168. PubMed PMID: 17371945; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1896114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.