Abstract

Promoting physical activity using environmental, policy, and systems approaches could potentially address persistent health disparities faced by American Indian and Alaska Native children and adolescents. To address research gaps and help inform tribally-led community changes that promote physical activity, this review examined the methodology and current evidence of physical activity interventions and community-wide initiatives among Native youth. A keyword guided search was conducted in multiple databases to identify peer-reviewed research articles that reported on physical activity among Native youth. Ultimately, 20 unique interventions (described in 76 articles) and 13 unique community-wide initiatives (described in 16 articles) met the study criteria. Four interventions noted positive changes in knowledge and attitude relating to physical activity but none of the interventions examined reported statistically significant improvements on weight-related outcomes. Only six interventions reported implementing environmental, policy, and system approaches relating to promoting physical activity and generally only shared anecdotal information about the approaches tried. Using community-based participatory research or tribally-driven research models strengthened the tribal-research partnerships and improved the cultural and contextual sensitivity of the intervention or community-wide initiative. Few interventions or community-wide initiatives examined multi-level, multi-sector interventions to promote physical activity among Native youth, families and communities. More research is needed to measure and monitor physical activity within this understudied, high risk group. Future research could also focus on the unique authority and opportunity of tribal leaders and other key stakeholders to use environmental, policy, and systems approaches to raise a healthier generation of Native youth.

Keywords: American Indians, Alaskan Natives, active living, physical activity, exercise, obesity

Introduction

The rapid rise in the multigenerational occurrence of chronic disease among American Indians and Alaska Natives has grave implications for the vitality and sustainability of our nation’s Indigenous people.1,2 One of the first nationally representative studies to estimate the prevalence of obesity among American Indian/Native Alaskan preschoolers estimated 31.2%, which was notably higher than the following four racial/ethnic groups: Asian (12.8%), non-Hispanic white (15.9%), non-Hispanic black (20.8%), and Hispanic (22.0%).3 To understand what may be contributing to these differences, investigators recommended future studies examine the role of community context, particularly as it relates to possible differences in eating and physical activity behaviors. Nevertheless, research on correlates, determinants or interventions specific to physical activity among American Indian and Alaska Native children and adolescents is limited.4–6 A systematic review of articles reporting on physical activity levels in Native American populations in Canada and the United States (US) published between 1960 to 2011 found that 26.5% (based on self-report) to 45.7% (based on pedometry and accelerometry) of children met physical activity recommendations put forth by Canada and the World Health Organization, among others.6

Exploring environmental, policy, and systems approaches to promote physical activity and obesity prevention among tribal communities may be particularly powerful since research has indicated health disparities may be partially explained by low-income, racial/ethnic minority and rural neighborhood environments with less access to public parks, open space, and private recreation facilities.7–10 Limited research, however, has examined the associations between the built environment and chronic diseases that focused exclusively on American Indian and Alaska Native communities.11,12 Even less direct observational research has been conducted to explore the features of the built environment that influence physical activity among tribal communities.4,13–16 Likewise, few studies have explored the role of tribal government in promoting or inhibiting physical activity through its courses of action, funding priorities, regulatory measures, laws and policies, and tribal resolutions (a common term used to describe an official expression of the opinion or will of a tribal government and may have the effect of law within the tribe’s jurisdiction).17,18

To address research gaps and help inform tribally-led community changes that promote physical activity, this review examined the methodology and current evidence of physical activity interventions and community-wide initiatives among American Indian and Alaska Native children and adolescents (Native youth). For our purposes, an intervention consisted of field trials or hypothesis-driven studies conducted by researchers often examining physical activity related outcomes at the individual level. A community-wide initiative generally consisted of projects or programs undertaken that were not necessarily using rigorous research designs and tended to focus more on environmental, policy, and system approaches at the community level.

Methods

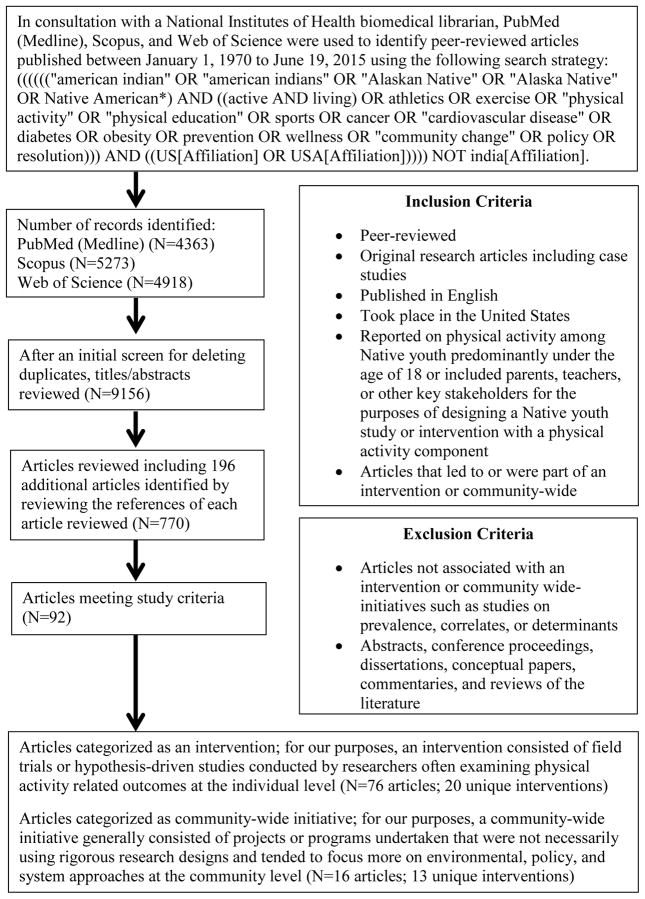

In consultation with a National Institutes of Health biomedical librarian, PubMed (Medline), Scopus, and Web of Science were used to identify peer-reviewed articles published between January 1, 1970 to June 19, 2015. In all three databases, the following search strategy was used: ((((((“american indian” OR “american indians” OR “Alaskan Native” OR “Alaska Native” OR Native American*) AND ((active AND living) OR athletics OR exercise OR “physical activity” OR “physical education” OR sports OR cancer OR “cardiovascular disease” OR diabetes OR obesity OR prevention OR wellness OR “community change” OR policy OR resolution))) AND ((US[Affiliation] OR USA[Affiliation])))) NOT india[Affiliation]. The references of each article were reviewed to identify any additional articles. Peer-reviewed original research articles including case studies published in English that took place in the US were considered if they reported on physical activity among Native youth predominantly under the age of 18. Articles were also considered if they included parents, teachers, or other key stakeholders for the purpose of designing a Native youth study or intervention with a physical activity component. Articles that led to or were part of an intervention or community-wide initiative were included. Emphasis was placed on interventions and initiatives using or providing insights on tribally-led environmental, policy, and system approaches to fostering active living; therefore, as one example, a national campaign tailored to American Indian children and parents, among other ethnic minority groups, was excluded (e.g., the VERB™ campaign19). Articles not associated with an intervention or community-wide initiative such as studies on prevalence, correlates, or determinants were excluded. In addition, abstracts, conference proceedings, dissertations, conceptual papers, commentaries, and reviews of the literature were excluded.

When possible, the following information was extracted from each article: year of publication, year of data collection, sample age, sample size used for final analyses, study setting, study design, measures and methods, data sources, psychometric properties, intervention strategies, outcomes, covariates, results, funding source, author identified strengths and limitations, and author identified lessons learned particular to conducting research and promoting physical activity among American Indians and Alaska Natives. Lead authors were contacted when necessary to obtain missing information. Inter-rater reliability was conducted with high agreement across all information extracted with minor reconciliations (SF’s codes were compared with RC’s codes for 74 articles and SF’s codes were compared with ER’s codes on 34 different, additional articles).

Results

770 articles were identified from the search strategy that reported on American Indian and/or Alaska Native health. Ultimately, 92 articles met the aforementioned study criteria. The following results summarize the methodology and current evidence of physical activity interventions (n=20 unique interventions; 76 articles) and then community-wide initiatives (n=13 unique initiatives; 16 articles) among Native youth (See Figure 1 along with Tables 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Overview of systematic search process

Table 1.

By targeted setting, interventions reporting on physical activity among Native youth (n=20 unique interventions; 76 articles)

|

Intervention Target Age Group Geographic Setting Sample Size |

Brief Description |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Childcare-based | |

|

| |

| The Child Health Initiative for Lifelong Eating and Exercise (CHILE)30,45,86,87 | Used a socio-ecological approach to design an intervention including classroom curriculum, teacher and food service training, family engagement, grocery store participation, and health care provider support. Reported on lessons learned and concluded Head Start could play an important role in improving physical activity among preschool children. |

| Preschool (Head Start) | |

| Southwest (6 rural Pueblos, New Mexico) 1879 | |

|

| |

| Church-based | |

|

| |

| Native Proverbs 31 Health Project39 | Conducted formative research to develop weekly classes during a 4-month period in 4 churches (2 primary churches and 2 delayed intervention churches) that were led by community lay health educators. Reported churches were receptive to the program including hosting a walking club. |

| Multiple Age Ranges (Adult Women and Girls > 12 years old) | |

| Southeast (Robeson County, North Carolina, homeland of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina) | |

| 4 Lumbee churches (64 women and 11 girls in 2 primary intervention churches; 82 women and 8 girls in 2 delayed intervention churches) | |

|

| |

| Family-based | |

|

| |

| Healthy Children, Strong Families18,31,68,88–93 | Conducted a randomized controlled trial of a healthy lifestyles intervention. Reported on how the community advisory boards established in each of the participating communities were highly effective at improving community environments including increasing people’s choices for engaging in physical activity. |

| Preschool (2 to 5 years) | |

| Midwest (four Wisconsin tribes) | |

| 120 families | |

|

| |

| Healthy Hearts Across Generations35 | Conducted a randomized controlled trial designed to evaluate a culturally appropriate cardiovascular disease risk prevention program for American Indian parents that included motivational interviewing counseling followed by personal coach contacts and family life-skills classes. Noted environmental interventions such as footpaths are being discussed with the community for future planning efforts. |

| Multiple (child closet to 5 years if multiple minors) | |

| Pacific Northwest | |

| 135 | |

|

| |

| Obesity Prevention Plus Parenting Support36 | Randomly assigned mothers to a 16-week intervention that was delivered one-on-one in homes by an Indigenous peer educator. Reported a trend towards significance for weight-for-height z scores increasing among the intervention group. |

| Early Infancy (ages of 9 months and 3 years) | |

| Northeast (St. Regis Mohawk community of Akwesasne located along the St. Lawrence River in northern New York State and Ontario and Quebec, Canada) | |

| 43 | |

|

| |

| Prevention of Toddler Obesity and Teeth Health Study29 | Conducted a randomized controlled trial designed to prevent obesity beginning at birth in American Indian children that was designed to promote breastfeeding, reduce sugar-sweetened beverage consumption, appropriately time the introduction of healthy solid foods, and counsel parents to reduce sedentary lifestyles in their children. Reported strengths and weaknesses of study design. |

| Early Infancy (birth cohort followed for two years) | |

| Pacific Northwest (five tribes who are members of the Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board (Idaho, Oregon and Washington)) | |

| 577 | |

|

| |

| The Indian Family Wellness Project38,94 | Described four tribal participatory research mechanisms with applicability to family-centered prevention research. Reported high participation and retention rates in research component of project. |

| Preschool (Head Start) | |

| Pacific Northwest (a tribe) | |

| Not specifically reported; noted more than 80% of enrolled families at four tribal Head Start sites participated | |

|

| |

| The Toddler Overweight and Tooth Decay Prevention Study34 | Tested the feasibility of community-tailored intervention using trained community health workers to deliver a family intervention through home visits. Reported family plus community-wide intervention may help attenuate body mass index rise in American Indian toddlers. |

| Early Infancy (birth cohort followed for two years) | |

| Pacific Northwest (three tribes who are members of the Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board) | |

| 178 | |

|

| |

| School-based | |

|

| |

| Bright Start20,95–100 | Conducted group-randomized trial that aimed to increase physical activity at school to at least 60 min/day; modify school meals and snacks; and involve families in making behavioral and environmental changes at home. Reported that changes in school physical activity were not significant and intervention children experienced a 13.4% incidence of overweight, whereas the control children experienced a corresponding incidence of 24.8%. |

| Elementary (Kindergarten to First Grade) | |

| Midwest (Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota) | |

| 454 | |

|

| |

| Cherokee Choices25 | Developed a program with three main components: elementary school mentoring, worksite wellness for adults, and church-based health promotion. Reported school policy was altered to allow more class time and after-school time devoted to health promotion activities. |

| Elementary (Kindergarten through Sixth Grade) | |

| Southeast (Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, North Carolina) | |

| ~600 | |

|

| |

| Pathways22,33,42,47,48,79–84,101–124 | Conducted a randomized controlled intervention trial over 3 consecutive years that had four components: change in dietary intake, increase physical activity, a classroom curriculum focused on healthy eating and lifestyle, and a family-involvement program. Reported no significant reduction in percentage body fat. Motion sensor data showed similar activity levels in both the intervention and control schools. |

| Elementary (Third through Fifth Grade) | |

| Multiple (seven American Indian communities) | |

| 1704 | |

|

| |

| Quest21 | Implemented a program that had four components: biochemical and anthropometric assessments, classroom instruction about diabetes, increased daily physical activity at school, and a structured school breakfast and lunch program. Reported preliminary results indicated that a school could provide a stable environment for behavior change that slows weight gain in early childhood. |

| Elementary (Kindergarten through Second Grade) | |

| Southwest (Gila River Indian community, Arizona) | |

| >200 | |

|

| |

| The Checkerboard Cardiovascular Curriculum23,37 | Pilot-tested a cardiovascular health education curriculum. Reported significant increases in knowledge about the cardiovascular system, exercise, nutrition, obesity, tobacco use, and habit change. |

| Elementary (Fifth Grade) | |

| Southwest (Navajo & Pueblo tribes, New Mexico) | |

| 218 | |

|

| |

| The Southwestern Cardiovascular Curriculum24 | Conducted a delayed intervention with three stages of intervention: basic curriculum only, basic curriculum plus peer pressure unit, and control (no intervention). Reported preliminary data indicated students experienced positive changes in health knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. |

| Elementary (Fifth Grade) | |

| Southwest (Navajo & Pueblo tribes, New Mexico) | |

| Not reported | |

|

| |

| Youth Wellness Program28,43 | Trained community members to lead in-school physical activity classes two times per week. Reported over the two year study period the percentage of youth with a high fasting blood glucose level of more than 125 mg/dL decreased concurrently with significant improvements in fitness measures. |

| Elementary (Third through Eighth Grade) | |

| Southwest (The Hualapai Tribe, Arizona) | |

| 71 | |

|

| |

| Zuni Diabetes Prevention Program32,44 | Used a multiple cross-sectional design to compare outcome measures of a diabetes prevention program including an educational component and a youth-oriented fitness center against an Anglo comparison group. Reported plasma glucose levels were normal at baseline for Zuni and Anglo youth and did not significantly change throughout the study. |

| High School (Juniors and Seniors) | |

| Southwest (Zuni Pueblo, New Mexico) | |

| 72 | |

|

| |

| Summer Day Camp | |

|

| |

| Healthy Living in Two Worlds26 | Developed a wellness curriculum to increase physical activity, decrease or prevent recreational tobacco use, and increase healthy eating practices in a summer day camp format. Reported program participants appeared to be physically active and their activity seemed to have increased after the program. |

| Elementary (9 to 13 years) | |

| Northeast (urban Northeastern population) | |

| 16 | |

|

| |

| Supervised Classes | |

|

| |

| Journey to Native Youth Health27,46 | Modified the diabetes prevention program to be developmentally and culturally appropriate for Native youth and delivered program through randomized small groups led by community members. Reported changes favoring the program were observed in measures of physical activity, knowledge, attitude and beverages, and kilocalories from fat consumed but no overall effect on body mass index was found after the short (three-month) duration of treatment. |

| Elementary (10 to 14 years) | |

| Northern Plains (two Montana Indian reservations) | |

| 64 | |

|

| |

| The Ho-Chunk Youth Fitness Program40 | Conducted a 24-week intervention that consisted of twice weekly classes with supervision for both nutrition and exercise. Reported mean fasting plasma insulin decreased after 24 weeks of training but percent body fat, glucose, and total cholesterol remained unchanged during this time. |

| Multiple (6 to 18 years) | |

| Midwest (Ho-Chunk Tribe, Wisconsin) | |

| 38 | |

|

| |

| Workshop | |

|

| |

| STOP Diabetes!41 | Piloted an educational intervention about diabetes. Reported positive post-workshop knowledge scores and 90% of the participants reported positive workshop experience. |

| High School (13 to 18 years) | |

| Midwest (Winnebago Indian Reservation, Nebraska) | |

| 28 | |

Table 2.

Community-wide initiatives reporting on physical activity among Native youth (n=13 unique initiatives; 16 articles)

|

Community-Wide Initiatives Geographic Setting |

Brief Description |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Chokka-Chaffa’ Kilimpi’, Chikashshiyaakni’ Kilimpi’58 | Conducted qualitative study to understand the meaning of health and well-being for Chickasaw families. Reported how traditional and contemporary contexts influenced participants’ responses. |

| Chickasaw Nation, south central Oklahoma | |

|

| |

| Communities Putting Prevention to Work50 | Provided training support through a workshop for analyzing, writing, and publishing Communities Putting Prevention to Work initiative findings. Reported participants viewed the workshop positively and one tribe has submitted a manuscript for publication. |

| Multiple study regions three tribes | |

|

| |

| Community Based Participatory Research Program Evaluation and Development Project59 | Created a community advisory board and developed an exercise survey to assess physical activity patterns, preferences, and determinants. Reported youth distinguished between sports and exercise with each possessing different determinants. Youth identified common motivators including friends, coach, and school. Barriers discussed included lack of programs and school or work. None of the youth reported meeting the recommended 60 minutes of strenuous exercise daily. |

| Rural tribal reservation in Washington | |

|

| |

| Community Coalitions54 | Described how community coalitions were formed, implemented, and maintained to teach culturally appropriate fitness activities to groups of community members. Reported how successful institutionalization of community events by tribal governments and American Indian agencies resulted in ongoing support in various communities for events that promote physical activity. |

| Four rural and three urban tribal communities including multiple Rancheria and an Indian reservation in Northern California | |

|

| |

| Community Readiness Model56 | Used a Community Readiness Model to assess and engage the community in addressing cardiovascular disease. Reported how using this model enabled the Choctaw Nation to make strong “inroads” into its respective service area through successful community engagement. |

| Choctaw Nation, south central Oklahoma | |

|

| |

| Health Impact Assessment55 | Described application of Health Impact Assessment to inform trail decisions affecting Cuba. Reported how assessment recommendations were being integrated into the public lands National Environmental Policy Act process for planning access to a new segment of the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail. |

| Cuba, New Mexico (rural, under-resourced, American Indian, Hispanic and Anglo community) | |

|

| |

| Healthy Native North Carolinians Network17,125 | Informed by the American Indian Healthy Eating Project, Healthy Native North Carolinians provides direct support to participating tribal communities to develop, implement, evaluate, disseminate, and sustain community changes that promote active living and healthy eating. |

| Seven American Indian tribes and four urban Indian organizations in North Carolina | |

|

| |

| Jemez Pueblo13 | Used participatory research to uncover sociocultural and environmental factors that indicate capacity for improving health including developing a tribal advisory committee, conducting focus groups, and interviewing key informants. Reported how built environment decisions are dominated by traditional connections to the natural environment and culture. |

| Pueblo of Jemez in rural New Mexico | |

|

| |

| Physical Activity Kit51 | Described the implementation of an across-the-lifespan train-the-trainer program that has trained more than 600 trainers in American Indian communities nationwide. |

| Multiple study regions | |

|

| |

| Pieiryaratgun Calritllerkaq (Healthy Living Through a Healthy Lifestyle)52 | Through a community-academic collaboration, project worked to use strategic planning and organizational development principles for health promotion; specifically working to develop goals, objectives, action and evaluation plans that integrated local traditions, Yup’ik culture, and research. Reported that physical activity was one of the focal areas. |

| Yup’ik village in rural Alaska | |

|

| |

| SNAP-Ed Social Marketing Program57 | Conducted formative research to identify Indigenous views of product, promotion, price, and place related to SNAP-Ed behavioral objectives. Reported major theme for product was diabetes prevention and participants indicated a preference for family-based education with promotion by elders, tribal leaders, and “everyday people”. |

| Chickasaw Nation, south central Oklahoma | |

|

| |

| Steps to a HealthierUS49,126,127 | Enabled funded communities to implement chronic disease prevention and health promotion efforts to reduce the burden of diabetes, obesity, asthma, and related risk factors. Found tribal communities were successfully able to tailor intervention to their specific cultural and community needs. |

| Multiple study regions | |

|

| |

| Tool for Health and Resilience in Vulnerable Environments53 | Conducted a community assessment, along with digital storytelling through a series of focus groups to identify and address upstream causes of food security on the reservation. Reported how tribal council and the health clinic wrote a grant to create a place for Native community members to engage in physical activity. The proposed walking and bike path would include culturally appropriate art and educational exhibits designed by Native American community members. The health clinic also created ‘Bike Wednesdays’ featuring group rides and free bike repair. |

| Round Valley, California (rural reservation, geographically isolated community located within a dense mountain range in Mendocino County in Northern California) | |

Interventions

For the 20 interventions identified (See Table 1), the following summarizes the study populations, theoretical frameworks, research design and methods, formative research and process evaluation, targeted settings and intervention strategies, and outcomes.

Study Populations

Almost half of the intervention trials identified (n=9; 45%) focused on elementary school-aged children.20–28 More recent interventions targeted early infancy (e.g., Prevention of Toddlers and Teeth Health Study29) and the preschool-aged period (e.g., CHILE30 and Healthy Children, Strong Families31). All of the interventions were based in rural tribal communities except Healthy Living in Two Worlds26, which was based in an urban setting. One-third (30%) of the interventions were based in the southwest region of the US.21,23,24,28,30,32 Eight interventions (40%) worked with more than one tribal community (e.g., Pathways33 worked with seven American Indian tribes residing in Arizona, New Mexico and South Dakota).23,24,27,29–31,33,34 Only four interventions had a sample size or recruitment goal greater than 500 participants.22,25,29,30

Theoretical Frameworks

Nine interventions (45%) noted being informed by a specific theoretical framework.20,22,23,26,27,30,31,35,36 Social learning theory22,26,35, social cognitive theory20,36, and grounded theory27,30 were mentioned most frequently. Others cited health promotion theory23,37 and theory of planned behavior31.

Research Design and Methods

Half of the interventions (n=10; 50%) explicitly noted using a participatory research approach such as a tribal-research partnership or community-based participatory research.22,25,27–31,35,38,39 As one example, Adams, et al.31 explained how their team used community-based participatory research, along with their history of university-tribal partnerships to jointly design Healthy Children, Strong Families.

Regarding study design, about one-third of the interventions (n=7; 35%) used a randomized controlled trial.20,22,24,29–31,35 The remaining two-thirds of the interventions were non-randomized trials (n=5; 25%)25,28,32,38,40 or pilot/feasibility studies (n=8; 40%)21,23,26,27,34,36,39,41. Three of the non-randomized trials discussed why using a randomized controlled trial would not be appropriate within their community contexts.28,32,38 Three self-described pilot studies used randomization.23,27,36 Additionally, Bright Start20, Pathways22, and the Zuni Diabetes Prevention Program32 mentioned conducting pilot and feasibility phases before implementing the interventions. Only four studies (20%) included a non-Native comparison sample.23,30,32,40

Formative Research and Process Evaluation

Formative assessments were described in almost half of the interventions (n=9; 45%).20,25,31,39,42–46 Most of the formative assessments used a mixed methods approach including qualitative methods such as key informant interviews and focus groups. Pathways also conducted direct observations42 while the Youth Wellness Program43 used a school self-assessment and a locally generated environmental inventory. Other interventions gathered formative research through youth health assessments, youth surveys or parent surveys (e.g., Healthy Children, Strong Families31 and Zuni Diabetes Prevention Program44). Similarly, process evaluation or measures were discussed by less than half of the interventions (n=9; 45%).20,26,27,29–31,34,39,47 Whether or not an intervention formally conducted formative assessments or a process evaluation, all but one intervention40 discussed their aim to develop a culturally appropriate intervention. Many of the physical activity cultural adoptions made emphasized cultural values to be fit both physically and spiritually and incorporated culturally relevant activities such as fishing, hiking, as well as traditional Native dancing and games. For instance, Brown et al.46 used community feedback to adapt the Diabetes Prevention Program and to develop and pilot Journey to Native Youth Health, which included traditional activities such as berry picking, nature walks, gardening, horseback riding and dancing, along with seasonal activities such as hunting, hiking, camping, sledding, skiing, and winter hockey.

Targeted Settings and Intervention Strategies

The targeted settings of the interventions were as follows: school-based (n=8; 40%), family-based (n=6; 30%), childcare-based (n=1; 5%), church-based (n=1; 5%), summer day camp (n=1; 5%), supervised classes (n=2; 10%), and workshop (n=1; 5%). In addition to the variation in targeted settings, the interventions used several types of strategies to promote physical activity among Native youth, usually incorporating more than one approach. All of the interventions used an educational or knowledge-based approach.20–32,34–36,38–41 Seventeen interventions (85%) included a train-the-trainer aspect as well that focused on training teachers, peer-educators, or other stakeholders how to deliver educational messages to the targeted audience.20,22,24–32,34–36,38,39,41 Almost two-thirds of the interventions (n=12; 60%) integrated a family- or household-based activity such as home visits, parent/caregiver lessons, and motivational interviewing for the parent/caregiver.20–22,26,27,29–31,34–36,38 Just over half of the interventions (n= 13;65%) enhanced opportunities to be physically active through environmental, policy, or system approaches such as increasing recess time, adding in class “action breaks”, or improving activity spaces or equipment.20–23,25,26,28,30–32,35,39,40 One school-based intervention offered fitness opportunities for the school’s faculty.25 Some of the interventions included multi-sector strategies that involved more than one setting (i.e., school, church and worksites)25,29,30,34 and/or integrated media-based approaches25,29,32,34. Regarding levels of and length of intervention studies, wide variation was found. As one example, one intervention was as short as a half-day41 workshop while another intervention provided more than three years of targeted intervention exposure22. However, the interventions were not always explicit about the levels of or length of the intervention. Put another way, interventions reviewed varied on discussing intervention dose or clarifying the length of their intervention versus providing the dates of their entire study period including design and manuscript development, the length of the follow-up period – if any, or the time devoted to the partnership process.

Outcomes

This section summarizes the physical activity relevant outcomes reported by the 20 interventions by individual, family/household, and environmental, policy, and systems approaches.

At the individual level, four interventions (20%) noted positive changes in knowledge and attitude relating to physical activity.22–24,41 Ten interventions (50%) discussed collecting physical activity behavior related data22,24,26–28,31,35,36,39,40; granted only four used accelerometers22,27,31,36 and only three reported post-intervention findings22,26,27. In Pathways22, based on accelerometry data, intervention schools were more active than control schools at three of the four sites examined, although the overall difference was not statistically significant. In Journey to Native Youth Health27, both the Journey Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) and health-oriented comparison condition group performed worse on accelerometer measures at the end of the program compared to baseline. The change in average daily minutes of moderate to vigorous activity for the Journey DPP group were small and not statistically significant while the comparison group had more substantial declines in daily moderate to vigorous activity. Finally, in Healthy Living in Two Worlds26, at post-test, youth reported exercising, on average, six of the past seven days. This finding was higher than the five days reported at pre-test. Participants in Healthy Living in Two Worlds also reported engaging in physical activity that burned between 400 and 499 calories per hour at post-test, which was 100 calories per hour higher than pre-test.

More than half of the interventions (n=14; 70%) mentioned calculating body mass index (BMI), predominantly using measured height and weight.20–22,24,27–31,34,36,39–41 Five interventions (25%) also collected body composition data such as percent body fat.20,22,24,40,41 Four interventions (20%) measured fasting blood glucose28,32,40,41 and only one of these three interventions did not measure plasma insulin levels28. One study measured blood pressure24 and another measured plasma cholesterol40. Nevertheless, only eight of these interventions (40%) ultimately reported on the weight (e.g., BMI or percent body fat) or health-related (e.g., blood glucose) data gathered as outcome measures post-intervention20,27,28,32–34,36,40 and none reported statistically significant improvements on weight-related outcomes.

At the family/household level, less than half of the interventions (n=8; 40%) examined parental level measures.20,29–31,33–36 Most of these interventions focused on a parent or primary care giver’s involvement in intervention study’s family-oriented events or child feeding practices (e.g., examined how a parent determines the foods and portion sizes their child(ren) are offered). Both Bright Start20 and Pathways48 reported low parental involvement in the intervention family events and indicated efforts to engage parents needed to be strengthened. Three interventions collected information about parent/caregiver height and weight but none published specific post-intervention findings on this data20,31,35.

Less than half of the interventions (n=9; 45%) examined environmental, policy, and systems approaches to promoting physical activity.20,21,25,28–30,33,34,39 Five interventions (25%) examined school-specific environmental or policy approaches that promote physical activity.20,21,25,28,33 CHILE focused on changes within childcare centers but also explored healthy eating intervention strategies targeting the local grocery stores.30 Two evaluated community-wide intervention completion plans primarily intended to help support breastfeeding initiation and duration.29,34 Only six interventions (30%) reported actually implementing environmental, policy, and system approaches relating to promoting physical activity.20,22,25,31,35,39 As one example, in Healthy Children, Strong Families, the Community Advisory Board component of the intervention was credited with decreasing environmental barriers to being physical activity such as instituting dog control regulations, building an environmentally friendly playground, and providing access to recreational facilities and community gardening.31 Cherokee Choices briefly noted “system changes in the school have generated increased physical activity among students and staff” and credited the intervention with increased faculty and student interest in activity related events and celebrations.25 While not much was mentioned about the sustained change of the Pathways physical activity intervention, standardization of the training was deemed to be critical to increasing the amounts of activity in students.22 Bright Start reported a trend, although not statistically significant, for increased duration in combined time in recess and physical education classes associated with the intervention.20 The study investigators discussed how such a trend indicates schools were changing their scheduling in response to the intervention. Moreover, the study investigators of Healthy Hearts Across Generations discussed how environmental interventions were being discussed with the community for future planning efforts with the hope that their intervention results would point to which strategies would be most effective and relevant for their families.35

Community-Wide Initiatives

For the 13 community-wide initiatives identified (See Table 2), the following summarizes the study populations, theoretical frameworks, research design and methods, and intervention strategies.

Study Populations

The targeted geographical regions of these community-wide initiatives varied. Specifically, initiatives examined multiple study regions49–51 or a tribal community or communities in Alaska52, California53,54, New Mexico13,55, North Carolina17, Oklahoma56–58, or Washington59.

Theoretical Frameworks

All of the initiatives mentioned being informed by theory or explicitly noted a theoretical framework guiding their study design, data analysis or interpretation processes. Wide variation was found in the types of theory mentioned and the extent to which theory was discussed. Social cognitive theory17 and grounded theory13,57 were mentioned, along with concepts or conceptual frameworks that emphasized biculturalism58, cultural humility50 and using a holistic approach51.

Research Design and Methods

All but one57 of the initiatives used some form of tribal participatory or partnership building approach to develop, implement, evaluate, or disseminate their initiative. Similarly, all of the community-wide initiatives were predominantly in the formative stages of partnership development. These manuscripts also provided preliminary insights on the initiative’s development, dissemination, and institutionalization processes and outcomes. Seven initiatives (54%) gathered qualitative data to garner insights using various qualitative and/or quantitative data collection strategies.13,17,53,56–59 Three initiatives (23%) used some form of community assessment17,53,55; however, two of these initiatives focused predominantly on evaluating the food environment versus the one that evaluated environmental and policy factors influencing physical activity53. Various culturally competent approaches were discussed including using digital storytelling53, a modified Talking Circle17, and a workshop series integrating Indigenous evaluation methods50. Only one initiative had some form of non-Native comparison group49 but more than a third (n=5; 38%) included more than one tribe17,49–51,54.

Strategies Used to Promote Physical Activity

While extensive detail and discussion were not provided on the strategies used within the targeted tribal communities to promote physical activity, six initiatives (46%) provided insights on promising areas such as improving environmental access to recreational areas and facilities and instituting school and worksite activity policies.13,17,49,53–55 For example, Davis et al.55 discussed how recommendations developed through their health impact assessment are being integrated into a public lands National Environmental Policy Act process for planning access to a new segment of the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail. Another initiative reported on the successful development of cultural fitness events for tribal communities designed by community coalitions.54 The Healthy, Native North Carolinians initiative was awarded a grant that supported tribally-led community changes to foster active living and healthy eating.17 Similarly, a tribal council and health clinic of a California tribal community used insights from their participatory research project to write a grant that would support the construction of a walking and bike path featuring culturally appropriate art and educational exhibits.53

Discussion

The aim of this review was to examine the methodology and current evidence of physical activity interventions and community-wide initiatives among Native youth. The following summarizes our findings from the 20 unique interventions and 13 unique community-wide initiatives examined for this review, identifies research gaps and opportunities, and provides recommendations for advancing tribally-led community changes that promote physical activity.

Study Populations

The majority of the interventions and community-wide initiatives occurred on Federal Indian reservations in rural areas. Small sample sizes were a challenge for most of the analyses and few had non-Native comparative samples. Since an effective intervention or community-wide initiative in one tribal community may not be effective in another tribal community, more research is needed to explore similarities and differences across tribal communities (e.g., by size, region, and urbanization).60,61 For example, several interventions such as Healthy Children, Strong Families31 or Pathways33, as well as community-wide initiatives such as Healthy, Native North Carolinians17 showed promise in collaborative, cross-tribal approaches. Equally as important is future work that explores similarities and differences between tribal communities and other ethnic minority, low-income, or rural communities.62–65 As one example, comprehensive research briefs examining physical activity among Native youth could be compared and contrasted with syntheses generated through Salud America! (https://salud-america.org) that focuses on reducing Latino childhood obesity or the African American Collaborative Obesity Research Network (www.aacorn.org) that focuses on weight-related issues in African American communities.

Theoretical Frameworks

Interventions and community-wide initiatives guided by social learning theory22,26,35, social cognitive theory17,20,36, or grounded theory13,27,30,57 generally discussed the value these theories had in shaping their study design, data analysis or interpretation processes. Concepts or conceptual frameworks emphasizing cultural traditions and a holistic approach were also discussed as valuable.50,51,58 Still, little is known about the theoretical underpinnings of increasing physical activity among Native youth in a specific tribe and generally among American Indian and Alaska Native communities. This is problematic because it limits developing interventions using socio-ecological models that target intersections between individual behavior changes and environmental, policy, and systems approaches. More longitudinal data gathered during longer invention periods or longer follow-up periods could help validate and extend theoretical findings among Native youth. In addition, future studies could explore further how best to construct theoretical and conceptual frameworks for guiding obesity prevention among Native youth that integrates what is known about promoting both active living and healthy eating.

Research Designs and Methods

Similar to prior findings66,67, community-based participatory research or tribally-driven research models were often utilized by reviewed studies and were generally described as effective at building trusting tribal-research partnerships. Another important approach identified was conducting formative research using mixed methods over multiple stages, which was generally recognized as a means of strengthening tribal-research partnerships, improving the design of more culturally and contextually sensitive methods and intervention strategies, and fostering a sense of community ownership for the intervention or community-wide initiative.68

Not surprising given findings from interventions including physical activity components focused on American Indian adults69,70, cultural adoptions made by the interventions and community-wide initiatives reviewed enhanced acceptability. These modifications generally included: emphasizing the close-knit nature of tribal communities (e.g., used alternative study designs to randomized controlled trials), integrating long-held Indigenous knowledge and value systems (e.g., recognized a holistic sense of body, mind, and spirit, along with relationships between human beings and their environments), and incorporating cultural traditions, norms, and sense of pride (e.g., encouraged Native dance, traditional games, hunting, and storytelling by community elders). Future research could test further the role of traditional and contemporary held beliefs and practices among Native youth, especially as more community- and youth-oriented work focuses on asset-based approaches, social media grows as a powerful medium to engage youth and relevant stakeholders across Indian Country, and as storytelling increasingly becomes digital.

Targeted Settings and Intervention Strategies

Based on our findings, interventions and community-wide initiatives aiming to increase physical activity among Native youth appear to be a culturally and contextually feasible approach to address their disproportionate risk of developing type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and obesity. Nevertheless, more research among Native youth is needed to identify specific contributors of physical activity-based strategies to health promotion and disease prevention including depression71, substance abuse72,73, and suicide prevention74. In addition, further work is needed to advance our understanding of the role of environmental, policy, and systems approaches in promoting physical activity among Native youth, families, and communities including the potential of multi-level and multi-sector approaches.75 Specifically, build on Pathways33, Bright Start20, and the Youth Wellness Program28 and evaluate further how environmental, policy, and systems approaches within and surrounding school settings can be maximized to increase physical activity among Native youth before, during, and after school, as well as on and off the school campus. Another research opportunity is building on findings from CHILE30 and Healthy Children, Strong Families31 to understand how to improve physical activity among children ages 0 to 5 years-old in the household, childcare setting, healthcare system, and other relevant settings. This includes exploring further lessons learned from Healthy Children, Strong Families on instituting dog control regulations31 since the average annual dog bite hospitalization rates have been shown to be higher among American Indian and Alaska Native children compared with the general US child population and may discourage outdoor play among Native youth.76 Aside from schools and childcare centers, more work is needed to understand how best to leverage intersections between community approaches and clinical services; as one example, further developing and disseminating best practices through the Indian Health Service (IHS) Special Diabetes Program for Indians and the IHS Health Promotion/Disease Prevention program.77 For some tribal communities, collaborations with churches may also be promising.39

To successfully identify potential environmental, policy, and systems approaches and gain the full participation of Native youth, families, and communities, future research could explore youth-oriented formative research formats46,59, community coalitions with youth representatives18,54, and capacity building workshops and technical assistance targeting key sectors17,50. Also helpful will be researchers and practitioners who focus on identifying, developing, implementing, evaluating, disseminating, and sustaining tribally-led environmental, policy, and systems approaches that recognize tribal leaders’ unique authority and opportunity to raise a healthier generation of American Indian and Alaska Native children. Recent initiatives encourage tribal leader action on promoting physical activity in addition to providing specialized funding and resources to support tribal leaders in making these types of changes such as the Healthy Native North Carolinians Network (http://americanindianhealthyeating.unc.edu/healthy-native-north-carolinians-2/), The Notah Begay III Foundation Native Strong Program (http://www.nb3foundation.org/our-work/programs/), and Let’s Move! in Indian Country (http://lmic.ihs.gov/). Dissemination research specific to tribal communities will be a critical component to understanding how to spread, apply, and tailor what works.78

Outcomes

The interventions and community-wide initiatives examined for this review were predominantly in the formative stages, relied on self-reported physical activity data, and often only shared anecdotal information about the environmental, policy, and systems approaches tried. To advance our understanding of physical activity among Native youth in general and specifically on the role of environmental, policy, and systems approaches, more research is needed to measure and monitor physical activity within this understudied, high risk group. This work would include improving how to measure and monitor physical activity within this population, since only Pathways extensively examined the psychometric properties (e.g., validity and reliability) of their evaluation instruments.22,33,79–84 Moreover, further work is needed to understand the prevalence, correlates, and determinants of physical activity among Native youth. As one example, national surveillance systems could be enriched with American Indian and Alaska Native children and adolescents under the age of 18 years. Care must be taken to ensure surveillance systems accurately account for Native youth who identify as mixed race.

Taking a life-course approach and exploring further how economic conditions interact with genetic and evolutional biology could potentially provide meaningful insights for designing long-term interventions.1,85 Another research opportunity is examining the effects of physical activity interventions on other outcomes such as depression, self-esteem, identify, cultural and traditional connectedness, substance use, and suicidal ideation. In addition, more rigorous research could expand our understanding of the effects of physical activity among Native youth on motor skill development, academic achievement, leadership development, and civic engagement.

Funding

Specialized funding from government and non-government sources plays a critical role in supporting culturally appropriate research and evaluation of physical activity interventions and community-wide initiatives targeting Native youth. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) was the primary support for 15 interventions (75%).20,22–24,26–32,35,36,38,39 Three of the remaining interventions acknowledged the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)25, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)40, and the American Medical Association41. About half of the community-wide initiatives were supported by the CDC (n=6; 46%)13,49–51,55,56; other funding sources acknowledged included the Indian Health Service (IHS)59, the NIH51,52, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA)57, state governmental agencies53,54, and foundations17,53,55. Future funding initiatives could focus on developing the next generation of American Indian and Alaska Native researchers and practitioners, ensuring strong skills in conducting community-based participatory research or tribally-driven research models. Another potential funding area that could be stimulated and strengthened is multi-level, multi-sector interventions to promote physical activity among Native youth. A call for data on the cost-effectiveness of implementing and sustaining interventions and community-wide initiatives targeting physical activity among Native youth will be instrumental in encouraging tribal leaders to explore these types of strategies and in advancing our understanding of how to bring effective approaches to scale in Indian Country. Similarly, more work with tribal leaders will help advance our understanding of how to encourage them to use environmental, policy, and systems approaches to promote physical activity and address any specific data needs they have to make informed decisions on these matters.

Conclusions

Few interventions noted positive changes in knowledge and attitude relating to physical activity and none reported statistically significant improvements on weight-related outcomes. Some interventions and community-wide initiatives discussed implementing environmental, policy, and system approaches relating to promoting physical activity but generally only shared anecdotal information about the approaches tried. Using community-based participatory research or tribally-driven research models could strengthen tribal-research partnerships and improve the cultural and contextual sensitivity of the intervention or community-wide initiative. More research is needed to better understand what to focus on to promote physical activity among Native youth. Future research could also focus on the unique authority and opportunity of tribal leaders and other key stakeholders to use environmental, policy, and systems approaches to raise a healthier generation of American Indian and Alaska Native children.

Table 3.

Study demographics and methods used for the 20 interventions with physical activity components among Native youth

| n (% of total) | Citation(s) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Target Age Group | ||

| Early Infancy (0–2 years) | 3 (15) | 29,34,36 |

| Preschool-Aged (2–5 years) | 3 (15) | 30,31,38 |

| Elementary School-Aged | 9 (45) | 20–28 |

| High School-Aged | 2 (10) | 32,41 |

| Multiple Age Ranges | 3 (15) | 35,39,40 |

|

| ||

| Geographic Setting (specific States examined) | ||

| Midwest (NE, SD, WI) | 4 (20) | 20,31,40,41 |

| Northeast (NY) | 2 (10) | 26,36 |

| Northern Plains (MT) | 1 (5) | 27 |

| Pacific Northwest (ID, OR, WA) | 4 (20) | 29,34,35,38 |

| Southeast (NC) | 2 (10) | 25,39 |

| Southwest (AZ, NM) | 6 (30) | 21,23,24,28,30,32 |

| Multiple Study Regions | 1 (5) | 22 |

| More than One Tribal Community | 8 (40) | 23,24,27,29–31,33,34 |

| Rural Setting | 19 (95) | 20–25,27–32,34–36,38–41 |

| Urban Setting | 1 (5) | 26 |

|

| ||

| Sample Size | ||

| <100 | 8 (40) | 26–28,32,36,39–41 |

| >100 but ≤500 | 6 (30) | 20,21,23,31,34,35 |

| >500 | 4 (20) | 22,25,29,30 |

| Not Reported | 2 (10) | 24,38 |

|

| ||

| Theoretical Framework | ||

| Informed by a Specific Theoretical Framework | 9 (45) | 20,22,23,26,27,30,31,35,36 |

|

| ||

| Methods | ||

| Used Participatory Research Approach | 10 (50) | 22,25,27–31,35,38,39 |

| Randomized Study Participants | 7 (35) | 20,22,24,29–31,35 |

| Non-Native American Comparison Group | 4 (20) | 23,30,32,40 |

| Conducted Formative Assessment or Research | 9 (45) | 20,25,31,39,42–46 |

| Included a Process Evaluation | 9 (45) | 20,26,27,29–31,34,39,47 |

| Mentioned Specific Cultural Tailoring Efforts | 19 (95) | 20–32,34–36,38,39,41 |

Table 4.

Targeted settings and intervention strategies for the 20 interventions with physical activity components among Native youth

| n (% of total) | Citation(s) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Targeted Setting | ||

| Childcare-based | 1 (5) | 30 |

| Church-based | 1 (5) | 39 |

| Family-based | 6 (30) | 29,31,34–36,38 |

| School-based | 8 (40) | 20–25,28,32 |

| Summer Day Camp | 1 (5) | 26 |

| Supervised Classes | 2 (10) | 27,40 |

| Workshop | 1 (5) | 41 |

|

| ||

| Intervention Strategies | ||

| Educational (e.g., knowledge-based activity) | 20 (100) | 20–32,34–36,38–41 |

| Enhanced Opportunities to Be Active | 13 (65) | 20–23,25,26,28,30–32,35,39,40 |

| Family- or Household-Component | 12 (60) | 20–22,26,27,29–31,34–36,38 |

| Integrated Other Sectors | 4 (20) | 25,29,30,34 |

| Media-based | 4 (20) | 25,29,32,34 |

| Training-the-Trainer (e.g., peer educators or staff) | 17 (85) | 20,22,24–32,34–36,38,39,41 |

|

| ||

| Length of Intervention, Partnership or Project | ||

| Less than Six Months | 7 (35) | 23,26,32,36,39–41 |

| One to Two Years | 8 (40) | 20,21,27–29,31,34,35 |

| Greater than Two Years | 5 (25) | 22,24,25,30,38 |

|

| ||

| Outcome Data Interventions Planned to or Reported Gathering1 | ||

| Physical Activity Related Knowledge and Attitude | 4 (20) | 22–24,41 |

| Physical Activity Related Behaviors | 10 (50) | 22,24,26–28,31,35,36,39,40 |

| Used Accelerometers | 4 (20) | 22,27,31,36 |

| Weight or Health-Related | 8 (40) | 20,27,28,32–34,36,40 |

| Environmental, Policy, and Systems Approaches | 6 (30) | 20,22,25,31,35,39 |

Includes outcomes the intervention planned to collect or gathered (e.g., BMI); however, not all of these interventions ultimately reported on the results of these data.

Acknowledgments

Verma Walker was of great assistance to us on developing our systematic search process. Support for preliminary data gathering and analysis for this review was provided in part by Healthy Eating Research, a national program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) (ID #66958); National Institutes of Health (NIH) University of North Carolina Interdisciplinary Obesity Training Grant (T 32 MH75854-03); and Kate B. Reynolds Charitable Trust (KBR).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the RWJF, NIH or KBR.

Contributor Information

Sheila Fleischhacker, Email: sheila.fleischhacker@nih.gov, Senior Public Health & Science Policy Advisor, Office of Nutrition Research, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, Two Democracy Plaza, Room 635, 6707 Democracy Boulevard MSC 5461, Bethesda, Maryland 20892-5461, – office 301-594-7440, mobile – 301-640-1396, fax – 301-480-3768.

Erica Roberts, Email: eblue@umd.edu, Doctoral Candidate, University of Maryland School of Public Health, Department of Behavioral and Community Health, 7923 Eastern Ave, Apt 1001, Silver Spring, MD 20910, voice – 410-236-7016.

Ricky Camplain, Email: camplain@email.unc.edu, Doctoral Student, University of North Carolina, Gillings School of Global Public Health, Department of Epidemiology, 137 East Franklin Street, Suite 303A, Chapel Hill, NC 27514, voice – 505-658-5262.

Kelly R. Evenson, Email: kelly_evenson@unc.edu, Research Professor of Epidemiology, University of North Carolina, Gillings School of Global Public Health, Department of Epidemiology, 137 E Franklin Street, Suite 306, Chapel Hill, NC 27514, voice – 919-966-4187.

Joel Gittelsohn, Email: jgittels@jhsph.edu, Johns Hopkins University, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Department of International Health, Center for Human Nutrition, 615 N. Wolfe Street, Rm W2041, Baltimore, MD 21205, voice – 410-955-3927.

References

- 1.Schell L, Gallo M. Overweight and obesity among North American Indian infants, children, and youth. Am J Hum Biol. 2012;24:302–313. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindberg S, Adams A, Prince R. Early predictors of obesity and cardiovascular risk among American Indian children. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(9):1879–1886. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1024-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson S, Whitaker R. Prevalence of obesity among US preschool children in different racial and ethnic groups. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(4):344–348. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teufel-Shone N, Fitzgerald C, Teufel-Shone L, Gamber M. Systematic review of physical activity interventions implemented with American Indian and Alaska Native populations in the United States and Canada. Am J Health Promot. 2009;23(6):S8–S32. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.07053151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer U, Plescia M. Addressing disparities in the health of American Indian and Alaska Native people: The importance of improved public health data. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(S3):S255–S257. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foulds H, Warburton D, Dredin S. A systematic review of physical activity levels in Native American populations in Canada and the United States in the last 50 years. Obes Rev. 2013;14:593–603. doi: 10.1111/obr.12032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan L, Sobush K, Keener D, et al. Recommended community strategies and measurements to prevent obesity in the United States. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009;58(RR-7):1–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bunnell R, O’Neil D, Soler R, Payne R, Giles WH, Collins J, Bauer U Communities Putting Prevention to Work Program Group. Fifty communities putting prevention to work: Accelerating chronic disease prevention through policy, systems and environmental change. J Community Health. 2012;37(5):1081–1090. doi: 10.1007/s10900-012-9542-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abercrombie L, Sallies J, Conway T, Frank L, Saelens B, Chapman J. Income and racial disparities in access to public parks and private recreation facilities. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sallis J, Cervero R, Ascher W, Henderson K, Kraft M, Kerr J. An ecological approach to creating active living communities. Ann Rev Public Health. 2005;27(14):1–14. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Connell M, Buchwald D, Duncan G. Food access and cost in American Indian communities in Washington State. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:1375–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fleischhacker S, Rodriguez D, Evenson K, et al. Evidence for validity of five secondary data sources for enumerating retail food outlets in seven American Indian communities in North Carolina. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:137. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallerstein N, Duran B, Aguilar J, et al. Jemez Pueblo: Built and social-cultural environments and health within a rural American Indian community in the Southwest. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(9):1517–1518. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King A, Castro C, Wilcox S, Eyler A, Sallis J, Brownson R. Personal and environmental factors associated with physical inactivity among different racial-ethnic groups of the U.S. middele-aged and older-aged women. Health Psychol. 2000;19:354–364. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.4.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coble J, Rhodes R. Physical activity and Native Americans: A review. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(1):36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teufel-Shone N. Promising strategies for obesity prevention and treatment within American Indian communities. J Transcult Nurs. 2006;17:224. doi: 10.1177/1043659606288378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleischhacker S, Byrd R, Ramachandran G, et al. Tools for Healthy Tribes: Improving access to healthy foods in Indian Country. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(3 Suppl 2):S123–S129. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams A, Scott J, Prince R, Williamson A. Using community advisory boards to reduce environmental barriers to health in American Indian communities, Wisconsin, 2007–2012. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11(E160):1–11. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huhman M, Berkowitz J, Wong F, et al. The VERB™ campaign’s strategy for reaching African-American, Hispanic, Asian, and American Indian children and parents. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(6S):S194–S209. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Story M, Hannan P, Fulkerson J, et al. Bright Start: Description and main outcomes from a group-randomized obesity prevention trial in American Indian children. Obesity (Sliver Spring) 2012;20(11):2241–2249. doi: 10.1038/oby.2012.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cook V, Hurley J. Prevention of type 2 diabetes in childhood. Clin Pediatr. 1998;37:123–130. doi: 10.1177/000992289803700210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Going S, Thompson J, Cano S, et al. The effects of the Pathways Obesity Prevention Program on physical activity in American Indian children. Prev Med. 2003;37:S62–S69. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris M, Davis S, Ford V, Tso H. The Checkerboard Cardiovascular Curriculum: A culturally oriented program. J Sch Health. 1988;58(3):104–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1988.tb05842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis S, Gomez Y. The Southwestern Cardiovascular Curriculum Project. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;699:265–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb18860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bachar J, Lefler L, Reed L, McCoy T, Bailey R, Bell R. Cherokee Choices: A diabetes prevention program for American Indians. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(3):1–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weaver H. Healthy Living in Two Worlds: Testing a wellness curriculum for urban Native youth. Child Adolesc Social Work J. 2010;27(3):231–244. doi: 10.1007/s10560-010-0197-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown B, Noonan C, Harris K, et al. Developing and piloting the Journey to Native Youth Health Program in Northern Plains Indian communities. Diabetes Educ. 2013;39(1):109–118. doi: 10.1177/0145721712465343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teufel-Shone N, Gamber M, Watahornigie H, Siyuja T, Crozier L, Irwin S. Using a participatory research approach in a school-based physical activity intervention to prevent diabetes in the Hualapai Indian community, Arizona, 2002–2006. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11(E166):1–11. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karanja N, Aickin M, Lutz T, et al. A community-based intervention to prevent obesity beginning at birth among American Indian children: Study design and rationale for the PTOTS Study. J Primary Prevent. 2012;33:161–174. doi: 10.1007/s10935-012-0278-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis S, Sanders S, Fitzgerald C, Keane P, Canaca G, Volker-Rector R. CHILE: An evidence-based preschool intervention for obesity prevention in Head Start. J Sch Health. 2013;83(3):223–229. doi: 10.1111/josh.12018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adams A, LaRowe T, Cronin K, et al. The Healthy Children, Strong Families Intervention: Design and community participation. J Primary Prevent. 2012;33:175–185. doi: 10.1007/s10935-012-0275-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ritenbaugh C, Teufel-Shone N, Aickin MJ, JR, et al. A lifestyle intervention improves plasma insulin levels among Native American high school youth. Prev Med. 2003;36:309–319. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(02)00015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caballero B, Clay T, Davis S, et al. Pathways: A school-based, randomized controlled trial for the prevention of obesity in American Indian schoolchildren. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:1030–1038. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.5.1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karanja N, Lutz T, Ritenbaugh C, et al. The TOTS community intervention to prevent overweight in American Indian toddlers beginning at birth: A feasibiltiy and efficacy study. J Community Health. 2010;35:667–675. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9270-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walters K, LaMarr J, Levy R, et al. Project heli?dxw/Healthy Hearts Across Generations: Development and evaluation design of a tribally based cardiovascular disease prevention intervention for American Indian families. J Primary Prevent. 2012;33:197–207. doi: 10.1007/s10935-012-0274-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harvey-Berino J, Rourke J. Obesity prevention in preschool Native American children: A pilot study using home visiting. Obes Res. 2003;11(5):606–611. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davis S, Gomez Y, Lambert L, Skipper B. Primary prevention of obesity in American Indian children. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;699:167–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb18848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fisher P, Ball T. The Indian Family Wellness Project: An application of the tribal participatory model. Prev Sci. 2002;3(3):235–240. doi: 10.1023/a:1019950818048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kimes C, Golden S, Maynor R, Spangler J, Bell R. Lessons learned in community research through The Native Proverbs 31 Health Project. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:130256. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carrel A, Meinen A, Garry C, Storandt R. Effects of nutrition education and exercise in obese children: The Ho-Chunk Youth Fitness Program. WMJ. 2005;104(5):44–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marlow E, D’Eramo G, Bosma A. STOP Diabetes! An educational model for Native Ameican adolescents in the prevention of diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 1998;24(4):441–443. 446–450. doi: 10.1177/014572179802400403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gittelsohn J, Evans M, Helitzer D, et al. Formative research in a school-based obesity prevention program for Native American school children (Pathways) Health Educ Res. 1998;13(2):251–265. doi: 10.1093/her/13.2.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Teufel-Shone N, Siyuja T, Watahomigie H, Irwin S. Community-based participatory research: Conducting a formative assessment of factors that influence youth wellness in the Hualapai community. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(9):1623–1628. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Teufel N, Ritenbaugh C. Development of a primary prevention program: Insight gained in the Zuni Diabetes Prevention Program. Clin Pediatr. 1998;37:131–141. doi: 10.1177/000992289803700211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sussman A, Davis S. Integrating formative assessment and participatory research: Building healthier communities in the CHILE Project. Am J Health Educ. 2010;41(4):244–249. doi: 10.1080/19325037.2010.10599150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown B, Harris K, Harris J, Parker M, Ricci C, Noonan C. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program for Northern Plains Indian youth through community-based participatory research methods. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36(6):924–935. doi: 10.1177/0145721710382582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steckler A, Ethelbah B, Jane Martin C, et al. Pathways process evaluation results: A school-based prevention trial to promote healthful diet and physical activity in American Indian third, fourth, and fifth grade students. Prev Med. 2003;37:S80–S90. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gittelsohn J, Davis S, Steckler A, et al. Pathways: Lessons learned and future directions for school-based interventions among American Indians. Prev Med. 2003;27:S107–S112. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nichols P, Ussery-Hall A, Griffin-Blake S, Easton A. The evolution of the Steps Program, 2003–2010: Transforming the Federal Public Health Practice of Chronic Disease Prevention. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E50. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.110220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jernigan V, Brokenleg I, Burkhart M, Magdalena C, Sibley C, Yepa K. The implementation of a participatory manuscript development process with Native American tribal awardees as part of the CDC Communities Putting Prevention to Work initiative: Challenges and opportunities. Prev Med. 2014;67:S51–S57. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Page-Reeves J, Davis S, Romero C, Chrisp E. Understanding “agency” in the translation of a health promotion program. Prev Sci. 2015;16(1):11–20. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0433-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lardon C, Soule S, Kernak D, Luple H. Using strategic planning and organizational development principles for health promotion in an Alaska Native community. J Prev Interv Community. 2011;39(1):65–76. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2011.530167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jernigan V, Salvatore A, Styne D, Winkleby M. Addressing food security in a Native American reservation using community-based participatory research. Health Educ Res. 2012;27(4):645–655. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pargee D, Lara-Albers E, Puckett K. Building on tradition: Promoting physical activity with American Indian community coalitions. J Health Educ. 1999;30(2):S37–S43. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Davis S, Cruz T, Korzoll R. Health impact assessment, physical activity and Federal lands trail policy. Health Behav & Policy Rev. 2014;1(1):82–95. doi: 10.14485/HBPR.1.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peercy M, Gray J, Thurman P, Plested B. Community readiness: An effective model for tribal engagement in pevention of cardiovascular disease. Fam Community Health. 2010;33(3):238–247. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3181e4bca9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parker S, Hunter T, Briley C, et al. Formative assessment using social marketing principles to identify health and nutrition perspectives of Native American women living within the Chickasaw Nation Boundaries in Oklahoma. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2011;43:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Deacon Z, Pendley J, Hinson W, Hinson J. Chokka-Chaffa’ Kilimpi’ Chikashshiyaakni’ Kilimpi’: Strong Family, Strong Nation. Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 2011;18(2):41–63. doi: 10.5820/aian.1802.2011.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Perry C, Hoffman B. Assessing tribal youth physical activity and programming using a community-based participatory research approach. Public Health Nurs. 2010;27(2):104–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sallis J. Measuring physical activity: Practical approaches for program evaluation in Native American communities. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2010;16(5):404–410. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181d52804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hodge F, Weinmann S, Roubideaux Y. Recruitment of American Indians and Alaska Natives into clinical trials. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10(8 Suppl):S41–S48. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00196-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Branscum P, Sharma M. A systematic analysis of childhood obesity interventions targeting Hispanic children: Lessons learned from the previous decade. Obes Rev. 2011;12(5):e151–e158. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Conn V, Chan K, Banks J, Ruppar T, Scharff J. Cultural relevance of physical activity intervention research with underrepresented populations. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2013;34(4):391–414. doi: 10.2190/IQ.34.4.g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brownson R, Housemann R, Brown D, et al. Promoting physical activity in rural communities: Walking trail access, use, and effects. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(3):235–241. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bock C, Jarczok M, Litaker D. Community-based efforts to promote physical activity: A systematic review of interventions considering mode of delivery, study quality and population subgroups. J Sci Med Sport. 2014;17(3):276–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.LaVeaux D, Christoper S. Contextualizing CBPR: Key principles of CBPR meet the indigenous research context. J Aboriginal Indigenous Comm Health. 2009;7(1):1–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mariella P, Brown E, Carter M, Verri V. Tribally-driven participatory research: State of the practice and potential strategies for the future. J Health Disparities Research Practice. 2009;3(2):41–58. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Adams A. Understanding community and family barriers and supports to physical actvity in American Indian children. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2010;16(5):401–403. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181f51636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Narayan K, Hoskin M, Kozak A, et al. Randomized clinical trial of lifestyle interventions in Pima Indians: A pilot study. Diabet Med. 1998;15(1):66–72. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199801)15:1<66::AID-DIA515>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Welch V, Casper M, Rith-Najarian S. Correlates of hypertension among Chippewa and Menominee Indians, the Inter-Tribal Heart Project. Ethn Dis. 2002;12(3):398–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roshanaei-Moghaddam B, Katon W, Russo J. The longitudinal effects of depression on physical activity. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2009;31:306–315. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dickerson D, Johnson C. Design of a behavioral health program for urban American Indian/Alaska Native youths: A community informed approach. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2011;43(4):337–342. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2011.629152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]