Abstract

Objectives

There is little knowledge about how emotional regulation contributes to vulnerability versus resilience to substance use disorder. With younger adolescents, we studied the pathways through which emotion regulation attributes are related to predisposing factors for disorder.

Methods

A sample of 3,561 adolescents (M age 12.5 years) was surveyed. Measures for emotional self-control (regulation of sadness and anger), emotional dysregulation (angerability, affective lability, and rumination about sadness or anger), and behavioral self-control (planfulness and problem solving) were obtained. A structural model was analyzed with regulation attributes related to six intermediate variables that are established risk or protective factors for adolescent substance use (e.g., academic involvement, stressful life events). Criterion variables were externalizing and internalizing symptomatology and positive well-being.

Results

Indirect pathways were found from emotional regulation to symptomatology through academic competence, stressful events, and deviance-prone attitudes and cognitions. Direct effects were also found: from emotional dysregulation to externalizing and internalizing symptomatology; emotional self-control to well-being; and behavioral self-control (inverse) to externalizing symptomatology. Emotional self-control and emotional dysregulation had independent effects and different types of pathways.

Conclusions

Adolescents scoring high on emotional dysregulation are at risk for substance dependence because of more externalizing and internalizing symptomatology. Independently, youth with better behavioral and emotional self-control are at lower risk. This occurs partly through relations of regulation constructs to environmental variables that affect levels of symptomatology (e.g., stressful events, poor academic performance). Effects of emotion regulation were found at an early age, before the typical onset of substance disorder.

Keywords: emotion regulation, behavioral self-control, symptomatology, mediation, adolescents

1. INTRODUCTION

Self-regulation has been an increasingly prominent theme in research on substance use and abuse (Wills et al., 2015b). Self-regulation measures have been linked to early-onset substance use and to substance use problems in late adolescence and early adulthood (Patock-Peckham et al., 2001; Simons et al., 2009, 2010; Tarter et al., 2003; Wills et al., 2011). Furthermore, life-span studies have shown that early observations of self-regulation predict mental and physical health outcomes over considerable time periods (Martin et al., 2007; Moffitt et al., 2011). Recent neuroimaging studies are showing structural and functional brain anomalies suggestive of emotion-regulation deficits among individuals with drug use disorders (Ersche et al., 2013; Kober, 2014). However, reviewers point out that it is not known whether emotion-regulation differences predate the onset of the disorder (Cheetham et al., 2010; Goldstein and Volkow, 2011). In this paper, we discuss evidence on behavioral and emotional regulation and report data on how emotion regulation is related to established risk and protective factors for substance use disorders. The data were obtained in early adolescence (11–14 years of age), before the typical age of emergence for substance disorder.

1.1. Behavioral regulation and substance use

A considerable body of evidence has accumulated on behavioral self-control and dysregulation. Behavioral self-control (also termed planfulness or reflectiveness) is typically indexed by measures such as planning, persistence, and problem solving (Wills and Dishion, 2004), linking behaviors and consequences over time (Zimbardo and Boyd, 1999), and monitoring progress toward goals (Hofmann et al., 2009). Behavioral self-control has consistently shown inverse relations to substance use (e.g., Audrain-McGovern et al., 2006; Brody and Ge, 2001; Wills et al., 2000a, 2001a,b; 2004a, 2007a,b; Wills and Stoolmiller, 2002; Zimbardo and Boyd, 1999) and some moderation effects have been demonstrated (e.g., Wills et al., 2002a, 2008). Behavioral dysregulation, indexed by measures tapping the tendency to act without thinking, be unable to inhibit prepotent responses, or have a tendency to rapidly discount the value of future rewards compared with present rewards, is positively related to likelihood/intensity of substance use (for reviews see Dawe and Loxton, 2004; Lejuez et al., 2010; Madden and Bickel, 2010; Perry and Carroll, 2008). In general, this research has studied self-regulation without reference to current or dispositional emotion. While the participants in these studies may have experienced positive or negative emotions at some time, studies relating behavioral self-control or impulsiveness to substance use have generally been conducted without reference to emotional states, though it has been recognized that decision making may be influenced by emotion (Cyders et al., 2007; Lieberman, 2007a; Metcalfe and Mischel, 1999; Steinberg, 2007).

The present research was based on a dual-process model of regulation. The dual-process approach posits that two distinct systems are involved in responding to environmental cues and regulating behavior. The two systems are alternatively termed automatic vs. controlled (Lieberman, 2007b; Wiers et al., 2007), reflective vs. impulsive (Hoffman et al., 2009), reasoned vs. reactive (Gerrard et al., 2008), or self-control and dysregulation (Wills et al., 2015b). The basic findings supporting the dual-process approach are (a) confirmatory studies of regulation measures show that a two-factor solution fits better than a one-factor solution, (b) measures of self-control and dysregulation show independent contributions (in opposite directions) to prediction of substance use, and (c) the two systems have different types of pathways to substance abuse (Wills and Ainette, 2010; Wills et al., 2011, 2013). This approach has heuristic value for clarifying SUD etiology because greater predictive power is obtained when considering both systems rather than only one (Gibbons et al., 2009; Hoffman et al., 2009) and the dual-process model helps to delineate multiple pathways to substance use problems (Simons et al., 2009; Wills et al., 2011). Previous studies with dual-process models have focused on behavioral regulation; in the present research we extend this approach to the study of emotional regulation.

1.2 Emotional regulation and substance use

Theory on emotion regulation has been available (e.g., Calkins, 1994; Eisenberg and Fabes, 1992; Southam-Gerow and Kendall, 2002), but generally has not been a prominent theme in substance abuse research. The exception is the self-medication model of Khantzian (1990), which proposes that poor regulation of negative emotional states (particularly anger) is an underlying factor in vulnerability to substance use disorder. This theory has influenced research on stress and coping motives for substance use (Audrain-McGovern et al., 2009; Cheetham et al., 2010; Sinha, 2008; Weinstein and Mermelstein, 2013a; Wills et al., 1999a, 2001c, 2002b; 2004b) and diagnostic studies have consistently shown that affective disorders (anxiety disorder and depressive disorder) tend to co-occur with substance use disorders (Kober, 2014). However, the temporal ordering of affective and substance use disorders remains unclear (Cheetham et al., 2010); the fact that negative mood is elevated among substance abusers does not necessarily show how they are causally linked (Kassel and Veilleux, 2010); and experience sampling studies have not consistently found a real-time relation between negative affect and drinking (see Mohr et al., 2010). Thus support for the self-medication model remains in flux. New studies have suggested alternate conceptions of affectivity and drug use, including reduced sensitivity to natural rewards (Audrain-McGovern et al., 2011, 2012); mood variability (Simons and Carey, 2002; Simons et al., 2009; Weinstein and Mermelstein, 2013b); and distinguishing situational and dispositional aspects for positive and negative affect (Colder et al., 2010; Simons et al., 2014).

Studies relating measures of emotional regulation to psychiatric or substance use disorders have mainly been conducted with adult substance abusers and focused on emotional dysregulation (e.g., Berking et al., 2011; Berking and Wupperman, 2012; Bonn-Miller et al., 2011; Fox et al., 2008; Fucito et al., 2010; Volkow et al., 2010). However, in our view the major issue is that most studies have not determined how emotion regulation is related to substance abuse. We think it is essential to determine the processes through which emotion regulation is linked to outcomes. Though regulation processes may be directly related to outcomes, some research with adolescents has shown that the linkage of behavioral self-regulation to substance use/abuse occurs through relations to intermediate variables (Wills and Ainette, 2010). Here, we adopt this approach for emotion regulation, assessing likely social/environmental and cognitive/attitudinal mediators and using structural equation modeling to determine how emotion regulation is related to substance-relevant outcomes.

Previous studies with adolescents have demonstrated a consistent measurement structure for behavioral and emotional regulation (Wills et al., 2006) and have related behavioral and emotional regulation to substance use problems (Wills et al., 2011). However these studies have assessed a limited range of mediators and have not determined the relation of emotional-regulation measures to externalizing or internalizing symptomatology, which are among the most-studied predictors of substance use disorder (Wills et al., 2005). Longitudinal studies have shown externalizing symptomatology in early adolescence (conduct-disorder related) to be a robust predictor of substance use disorder in late adolescence and early adulthood (e.g., Brook et al., 1995; Chassin et al., 1999; Englund et al., 2008; Fergusson et al., 2007; Guo et al., 2001; Pulkkinen and Pitkänen, 2004; White et al., 2001; Windle, 1990). Findings on internalizing symptomatology (depressive or anxiety-disorder related) are less consistent (for reviews see Cheetham et al., 2010; Colder et al., 2010). Though some studies have shown positive relations of internalizing symptomatology to substance use, results may vary by substance (King et al., 2004; Maskowsky et al., 2014; Tarter et al., 2007) and extent of comorbidity (Colder et al., 2013; Goodman, 2010; King and Chassin, 2007; Pardini et al., 2007; Roberts et al., 2007; Scalco et al., 2014; Schuckit and Smith, 2006; Wittchen et al., 2007).

1.3. Rationale for present research

To gain more understanding of how emotional regulation contributes to risk for substance use disorder, we conducted a study in early adolescence, a time when few if any persons have developed a disorder. We used a dual-process approach, positing that emotional self-control and dysregulation are distinct constructs that make independent contributions to outcomes. We assessed how participants dealt with feelings of sadness or anger (i.e., emotional self-control) and obtained measures on affective variability, rumination, and inability to control anger in problem situations (i.e., emotional dysregulation). Our analytic approach addressed the empirical finding in our previous studies that measures of behavioral and emotional self-control are substantially correlated (Wills et al., 2006, 2011) by including behavioral self-control in the model. We also wanted to emphasize the concept that self-control is partly a social phenomenon which originates in parental socialization and is actualized in social relationships with peers, teachers, and other adults (Sussman and Ames, 2008; Sussman et al., 2003; Wills et al., 2014). Hence, we included paths from parental variables to self-control in the model in order to recognize the social background of self-regulation. We tested for pathways from regulation variables to outcomes through established risk and protective factors for adolescent substance use (Scheier, 2010). These include developed competencies, life stress, deviance-prone attitudes, perceptions of substance users, and perceived risk from substance use (Bryant et al., 2003; Gerrard et al., 2003; Gibbons et al., 2015; Jessor and Jessor, 1977; Wills et al., 2002b, 2004b). The criterion variables were externalizing symptomatology and internalizing symptomatology because of their place in affective models of risk for substance use disorder (Kassel et al., 2010). We also included a measure of positive well-being because recent reviews have emphasized its likely importance as a protective factor but noted that there is a lack of research on the role of positive affect in vulnerability for substance abuse (Cheetham and Allen, 2010; Colder et al., 2010; Gilbert, 2012).

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants and procedure

This research was conducted with middle school students in Hawaii. Prior research has demonstrated that predictive effects found with adolescents in Hawaii are similar to findings obtained elsewhere (Isasi et al., 2013; Wills et al., 2013, 2015a). The participants were 3,561 students (74% response rate) in ten public middle schools (80% of invited schools participated) on Oahu, Hawaii. The sample was 52% female and mean age was 12.49 years (SD 0.86); 11% of the participants were 6th graders, 47% were 7th graders, and 42% were 8th graders. Regarding race/ethnicity, 34% of the participants were of Asian-American background (Chinese, Japanese, or Korean), 8% were Caucasian, 29% were Filipino-American, 23% were Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and 6% were of other race/ethnicity (mainly African-American or Hispanic). Regarding family structure, 20% of participants were living with a single parent, 8% were in a stepparent family, 56% were with two biological parents, and 16% were in an extended family structure (two parents + one or more relatives). The mean parental education on a 1–6 scale was 4.2 years (SD 1.2), indicating some education beyond high school.

Data were obtained through a self-report questionnaire administered to students in classrooms by trained research staff. The procedure was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board for the University of Hawaii and by the Hawaii Department of Education. A consent form sent through the school to parents informed the parent about the purpose and nature of the research. The parent was asked to indicate whether his/her child would be allowed to participate in the research and return the form to the school. Prior to survey administration, students with parental consent were similarly informed about the purpose and nature of the research, were instructed that participation was voluntary, and signed an assent form if they decided to participate. Initial instructions to participating students emphasized confidentiality and stated that the student should not write his/her name on the survey. Methodological studies have shown that when participants are assured of confidentiality, self-reports of substance use have good validity (e.g., Brener et al., 2003; Patrick et al., 1994).

2.2 Measures

Measures were scored such that a higher score indicates more of the attribute named in the variable label. Distal variables and intermediate variables are summarized in Table 1. Regulation and symptomatology measures are described below in more detail.

Table 1.

Description of distal and intermediate variables

| Variable | Items | Alpha | Sample item |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1 | B | Are you: (female) (male. |

| Age | 1 | B | Write in your age in years. |

| Ethnicity | 14 | -- | What would you say you are? (14 options) |

| Family structure | 9 | -- | What adults do you live with now? (9 options) |

| Parental education | 2 | B | What is the highest level of education your father |

| has completed? (Grade School - Post College) |

|||

| Parental support | 10A | .90 | When I feel bad about things, my parent will listen. |

| Parent-child conflict | 3A | .82 | I have a lot of arguments with my parent. |

| Academic involvement | 8A | .82 | Getting good grades is important to me. |

| Academic alienation | 7A | .69 | Usually, school bores me. |

| Negative life events | 20B | B | Subscales for adolescent events, family events. |

| Tolerance for deviance | 10C | .96 | How wrong do you think it is: To take things that don=t belong to you. |

| Prototypes of sub. users | 15D | .92 | Think about the type of kid your age who smokes. Circle a number to show your image of kids who smoke. (popular, smart, cool) |

| Perceived harm | 6E | .89 | How much do you think people would be harming themselves if the smoke 1 pack of cigarettes a day? |

| Perceived risk | 3F | .92 | If you smoked cigarettes, do you think in the future you could get a sickness that comes from smoking? |

Note: For analysis, perceived harm and perceived risk were combined in a single score on Cognitive Risk. For sources see Bryant et al., 2003; Gerrard et al., 2003; Gibbons et al., 2015; Jessor and Jessor, 1977; Wills et al., 2004b, 2011; 2013, 2014.

1–5 Likert scale, Not at all true for me - Very true for me.

1–5 scale, Not at all wrong - Very wrong.

0–1 scale, No - Yes.

1–5 scale, Not at all - Very.

Categorical responses, Not harming themselves at all - Will be harming themselves a lot.

Categorical responses, Definitely wouldn=t get it - Definitely would get it.

2.2.1 Regulation measures

Items for the regulation measures were introduced with the stem: “Here are some things that people may say about themselves. Circle a number to show what is true for you.” The items had 5-point Likert response scales (Not at all True - Very True). For behavioral self-control, measures were derived from previous inventories (Kendall and Wilcox, 1979; Wills et al., 2001c; Zimbardo and Boyd, 1999). A composite score was based on a 7-item subscale on planning and persistence (e.g., “I like to plan things ahead of time,” “I stick with what I=m doing until it=s finished”), a 5-item scale on future time perspective (“Thinking about the future is pleasant for me”), and a 6-item subscale on problem solving (“When I have a problem, I think about the choices before I do anything”). For emotional self-control, measures were derived from the noted sources plus an inventory for emotional regulation Zeman et al. (2001). A composite score was based on a 5-item scale on soothability (e.g., “I can calm down when I am excited or wound up”), 4-item subscale for sadness control (“When I=m feeling down, I can control my sadness and carry on with things”), and a 4-item subscale for anger control (“When I=m feeling mad, I can control my temper”). For emotional dysregulation, measures were from the noted sources plus a scale on affective lability (Simons and Carey, 2002). A composite score was based on a 6-item subscale on angerability (e.g., “When I have a problem at school or at home, I get mad at people”), a 5-item scale on affective lability (“My moods change a lot from day to day”), and 3-item scales on sadness rumination (“I often get sad thinking about things that have happened in the past”) and anger rumination (“When people do something to make me angry, I don=t forget about it”).

2.2.2 Symptomatology and well-being

Items all had a 30-day time frame and 5-point Likert response scales (Not at all True - Very True). Externalizing symptomatology (from Achenbach, 1991) was a 7-item scale with items indexing arguing, destructiveness, disobedience, and fighting. Internalizing symptomatology (Achenbach, 1991) was a 5-item scale with items indexing loneliness, anxiety, and sadness. Positive well-being (Veit and Ware, 1983) was a 5-item scale indexing happiness, energy, and friendliness.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Structural equation modeling analysis was conducted in Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, 2010), using the maximum likelihood method with robust estimates of standard errors to adjust for any nonnormality in the variables, and with school included as a clustering factor. The model was specified with parental support, parent-child conflict, and two demographic variables (gender and parental education) as exogenous, with all their covariances included in the model. Behavioral self-control and the two emotional regulation measures were specified as endogenous, with covariances of their error terms. The six variables hypothesized to mediate the effects of regulation were specified subsequent to the regulation measures, again with all their residual covariances. Externalizing and internalizing symptomatology and positive well-being were specified as the criterion variables. The model was initially estimated with all paths from distal variables to the regulation measures, all paths from the regulation measures to the intermediates, and all paths from intermediates to the criterion variables. Nonsignificant paths were dropped from the initial model using a conservative criterion (p > .01) because of the large sample size. Direct effects to mediators or criteria were then added on the basis of modification indices > 20.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics for the regulation measures (Table 2) showed behavioral self-control and emotional self-control had distributions close to normal; there was a slight shift of emotional dysregulation toward lower values but the skewness value (positive by convention) was moderate. The zero-order correlation of emotional self-control and emotional dysregulation was r = −.33, consistent with the dual-process model. The zero-order correlation of emotional and behavioral self-control was r = .50, consistent with prior research.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for regulation and symptomatology variables

| Variable | Range | M | SD | Skewness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral self-control | 18–90 | 62.61 | 12.21 | −0.18 |

| Emotional self-control | 13–65 | 42.27 | 10.42 | −0.04 |

| Emotional dysregulation | 14–70 | 31.91 | 10.21 | 0.74 |

| Externalizing symptomatology | 7–35 | 13.55 | 5.74 | 1.14 |

| Internalizing symptomatology | 5–25 | 11.70 | 5.53 | 0.69 |

| Positive well-being | 5–25 | 19.35 | 4.30 | −0.61 |

Distributions for externalizing symptomatology and internalizing symptomatology (Table 2) were somewhat shifted toward lower values but there was considerable variance in the symptomatology scores and skewness values were moderate. Participants tended to endorse relatively good levels of well-being, but again there was considerable variance of scores and the skewness value (negative by convention) was moderate.

3.2 Structural modeling analysis

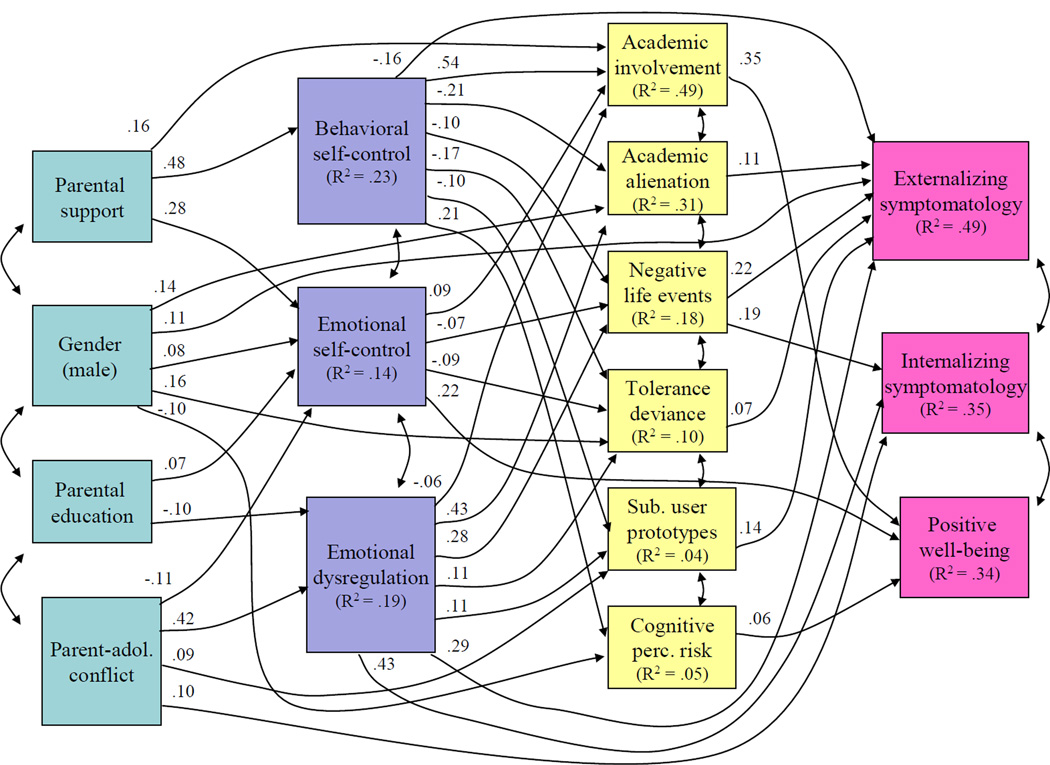

The final model is presented in Figure 1 with standardized coefficients; all coefficients in the figure are significant at p < .01. The model had chi-square (48 df, N = 3,561) = 207.37, Comparative Fit Index = .99, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation of .031 (90% Confidence Interval .026 − .035), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual = 0.026, all parameters indicating excellent fit. Several paths that were excluded from Figure 1 for graphical simplicity are presented in Table 3. For residual correlations among intermediate variables the mean |r| was .14 (range −.35 to .20). Prior variables accounted for different amounts of explained variance in the hypothesized mediators, with R-squares ranging from .49 (academic involvement) to .05 (for prototypes of users and perceived risk of use). Together the variables in the model accounted for 49% of the variance in externalizing symptomatology, 35% of the variance in internalizing symptomatology, and 34% of the variance in positive well-being.

Figure 1.

Structural model of distal, intermediate, and criterion variables. Straight single-headed arrows represent path effects, curved double-headed arrows represent covariances. Values are standardized coefficients; all are significant at p < .01. All covariances among the distal variables, the regulation variables, and the intermediate variables were included in the model but these three sets of covariances are represented only schematically in the figure. R2 figures indicate the variance accounted for in a given construct by all constructs to the left of it in the model. Six paths that were included in the model but were excluded from the figure, for graphical simplicity, are in Table 3.

Table 3.

Significant paths included in model but not graphed in Figure 1

| Path | Beta | p |

|---|---|---|

| Parental support - Positive well-being | 0.13 | < .0001 |

| Male gender - Academic Involvement | −0.07 | < .001 |

| Male gender - Internalizing symptomatology | −0.10 | < .0001 |

| Parent conflict - Academic alienation | 0.10 | < .0001 |

| Parent conflict - Negative life events | 0.13 | < .0001 |

| Parent conflict - Externalizing symptomatology | 0.13 | < .0001 |

Note: These paths were significant in the model but were excluded from the figure for graphical simplicity

Overall the results were consistent with our predictions. The three regulation measures had indirect effects to criterion variables through the hypothesized mediators. A summary of the direct and indirect effects is presented in Table 4. All of the indirect effects were significant, with the Critical Ratio (analogous to a t test) ranging from 3.28 (p < .001) to 17.11 (p < .0001). Four direct effects were also found: behavioral self-control to (less) externalizing symptomatology, emotional self-control to (more) positive well-being, and emotional dysregulation to more externalizing and internalizing symptomatology. The following sections summarize the findings in a theoretical order. Note that all the findings reported here are independent effects because the residual correlations among regulation variables and mediators were partialled in any effects noted to subsequent variables in the model.

Table 4.

Indirect and direct effects for regulation variables to symptomatology (b’ and SE), with Critical Ratio (CR)

| Total | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From | To | indirect | CR | direct | CR |

| Behavioral SC | Externalizing Sx | −0.033 (.004) | 9.23**** | −0.073 (.007) | 10.12**** |

| Internalizing Sx | −0.016 (.003) | 4.71**** | .--- | ||

| Pos. well-being | 0.143 (.008) | 17.11**** | .--- | ||

| Emotional SC | Externalizing Sx | −0.012 (.003) | 4.35**** | .--- | |

| Internalizing Sx | −0.013 (.004) | 3.28*** | .--- | ||

| Pos. well-being | 0.027 (.005) | 5.58**** | 0.182 (.014) | 13.04**** | |

| Emotional Dysreg |

Externalizing Sx | 0.090 (.007) | 13.45**** | 0.197 (.012) | 16.14**** |

| Internalizing Sx | 0.067 (.008) | 8.81**** | 0.553 (.024) | 23.51**** | |

| Pos. well-being | −0.023 (.005) | 4.17**** | .--- | ||

Note: SC = self-control; Sx = symptomatology; pos. = positive; dysreg = dysregulation.

indicates p < .001

indicates p < .0001.

3.2.1 Regulation variables

Emotional self-control had the fewest unique effects as its substantial correlation with behavioral self-control was partialled. It did have statistically significant paths to more academic involvement, fewer life events, and less tolerance for deviance; it also had a substantial direct effect to positive well-being. In contrast, emotional dysregulation had effects to most subsequent variables, with an inverse path to academic involvement and substantial paths to more academic alienation and more negative life events, as well as more tolerance for deviance and favorable perceptions of substance users. Dysregulation also had direct effects to both externalizing symptomatology and internalizing symptomatology. Behavioral self-control was an important variable in this model, with substantial paths to more academic involvement and less alienation, and inverse paths noted to the risk factor mediators (life events, tolerance for deviance, and prototypes of users) plus a positive path to more perceived risk. Behavioral self-control also had an inverse direct effect to externalizing symptomatology thus adding to its status as a protective factor.

3.2.2 Mediator variables

Academic domains were important parts of the risk and protection process. Academic involvement had a substantial path to more positive well-being and academic alienation had an inverse path to externalizing symptomatology. Stress-coping aspects of the data are evident in the paths from negative life events to both externalizing symptomatology and internalizing symptomatology. Attitudinal and cognitive factors were less important in the model, but there were paths from deviant attitudes and perceptions of users to externalizing symptomatology, and perceived risk showed a positive relation to well-being.

3.2.3 Background variables

Parental support had substantial paths to behavioral and emotional self-control and a direct effect to academic involvement (independent of its pathways through self-control). In contrast, parent-child conflict had a large positive path to emotional dysregulation and an inverse path to emotional self-control, as well as a direct effect to internalizing symptomatology. Paths from male gender to more academic alienation and tolerance for deviance and less perceived risk, as well as a direct effect to externalizing symptomatology, reflect multiple aspects of the higher risk accruing for boys during adolescence. Higher parental education was related to more emotional self-control and less emotional dysregulation.

4. DISCUSSION

The purpose of this research was to clarify how emotional regulation is involved in contributing to externalizing and internalizing symptomatology, which are major risk factors for later substance use problems. We also assessed positive well-being, an understudied protective factor in adolescent psychopathology (Colder et al., 2010; Gilbert, 2012). We found that the emotional regulation variables had both direct and indirect effects to symptomatology dimensions, controlling for demographic characteristics and parenting. Moreover, emotional self-control and emotional dysregulation made independent contributions to intermediate risk and protective factors, supporting a dual-process approach that has been proposed at the behavioral level (Gerrard et al., 2008; Wills et al., 2011) and the neurological level (Smith and Graybiel, 2013; Volkow and Baler, 2012).

4.1 Direct and indirect pathways

The substantial number of indirect pathways to symptomatology were mainly through positive relations of emotional (and behavioral) self-control to academic variables and cognitive variables such as perceived risk. It should be noted, though, that inverse paths were also found from these variables to lower levels of negative life events and tolerance for deviance. Thus the pathways of operation for emotional self-control include both developed competencies, cognitive variables, and stress-related factors to some extent. Emotional dysregulation showed strong paths to alienation from academics and occurrence of negative life events. However, it was also related to tolerance for deviance and favorable perceptions of substance users, so again the effects of emotion regulation include cognitive as well as stress-related factors. The indirect paths suggest that regulation of behavior and emotion have effects that extend beyond an influence on individual substance use decisions. Substance use itself is sometimes viewed as a failure of self-control or a maladaptive attempt to regulate emotion. Though this may be true to some extent, the current findings indicate that self-control and dysregulation have more distal and subtle effects through shaping a developmental trajectory and a socio-environmental context that either encourages or discourages substance use and its associated problems.

Several direct effects to symptomatology dimensions were noted for the regulation variables. A straightforward interpretation is that these symptomatology syndromes represent, in part, disorders of regulation: persons in the high range on externalizing are more reactive to provocations and cannot inhibit inappropriate behaviors, while persons scoring high on internalizing have difficulty managing negative emotions and cannot get depressive thoughts out of their heads. Though this conceptualization seems straightforward, the present results indicate that it is only part of the picture. For example persons with high scores on externalizing feel alienated from school, have relatively favorable attitudes toward smokers/drinkers, and view typical antisocial behaviors as not being very wrong. The causal orderings in these relations may have some complexity; for example, students who fight with others are likely to be disciplined, which would sour their (already negative) attitude toward school. It is undoubtedly more complex to predict symptomatology syndromes rather than individual variables, but the present research helps us understand the range of cognitive, attitudinal, and stress-related factors through which these syndromes come about.

4.2 Other questions

We found that the predictors of positive well-being were different from those for negative outcomes, consistent with research on positive and negative affect (cf. Cheetham et al., 2010; Gilbert, 2012). Indeed, the strongest effect noted for emotional self-control was a direct effect to well-being. Because of the protective effects noted for long-term positive mood in relation to substance use (Colder and Chassin, 1997; Simons et al., 2014; Wills et al., 1999b) this indicates an important pathway for the positive aspects of emotional regulation. Also noteworthy was the large path from academic involvement to well-being. Being accepted and valued for academic performance, and affiliating with peers who value academics (Sussman et al., 2007) is a significant benefit for teenagers. Thus there is a rationale for attention to emotion regulation as a means for enhancing positive affect and academic involvement (Wills et al., 2015b).

Two additional questions about self-regulation are: How does complex self-control ability develop? and Why are behavioral and emotional self-control strongly correlated? We suspect that these issues are related. Complex self-control abilities are based on a substrate of simple temperament dimensions that, in transactions with parental supportiveness, shape the development of self-control (Farley and Kim-Spoon, 2014; Tarter et al., 1999; Wills and Dishion, 2004). Note, however, that correlations between parental attributes and adolescent attributes may be attributable in part to shared genetic characteristics, and this should be considered for interpreting parent-child correlations (Farley and Kim-Spoon, 2014; Rutter et al., 1997).

Regarding the correlation between behavioral and emotional control, attentional control is a component of behavioral self-control (Wills et al., 2015b) and is relevant for both behavioral and emotional regulation (Rothbart and Ahadi, 2000; Rothbart et al., 2015). In addition, problem situations in adolescence involve both provocation and problem solving, and thus require both behavioral and emotional control. Therefore we think the correlation of these dimensions is partly based in the situational context of self-control and is learned in situations involving parents or peers (Sussman et al., 2003; Wills et al., 2011). The results pose several intriguing questions about self-control that are not definitively answered here but may be pursued in further research.

Preventive interventions derived from self-control research may use explicit training in cognitive-behavioral approaches for managing emotions and identifying situations that are triggers for loss of control of emotion (Conrod et al., 2013; Siegel, 2010; Southam-Gerow, 2013) as well as increasing access to alternative reinforcers (Audrain-McGovern et al., 2011). Another approach is to use self-control training on simple tasks, such as squeezing a hand grip, on the rationale that enhanced confidence in self-control will generalize to more complex situations (Muraven, 2010). Approaches for clinic settings based on implicit cognitions may use evaluative conditioning to instill negative affective reactions to alcohol cues (Houben et al., 2010; Wiers et al., 2011) or use cognitive bias modification to make positive emotions more cognitively accessible (Hertel and Matthews, 2011). School-based training may use games and exercises to build working memory and complex executive functions as scaffolding for the development of enhanced self-control (Berkman et al., 2012; Diamond et al., 2011; Ursache et al., 2011). Training in specific emotion-regulation strategies shown effective in laboratory studies (Aldao et al., 2010) and in complex packages such as mindfulness meditation (Brewer et al., 2013; Elwafi et al., 2013) are unexplored but promising areas. Such prevention-oriented research can expand the scope and effectiveness of treatment for substance dependence as well as testing the theoretical basis for emotion-regulation constructs in school and clinical settings.

4.3 Limitations

Some aspects of this study could be noted as possible limitations. The measures of emotional regulation were relatively brief ones and were obtained through self-reports. Further research could index emotional regulation through multiple methods including performance measures (though see Meda et al., 2010; Reynolds et al., 2006). Also, the measures of emotion regulation focused on ability to control emotion but did go into extensive detail on specific strategies of regulation. Further research using epidemiological methods or experience sampling designs could test hypotheses about the effectiveness of particular emotion regulation strategies in general populations (Webb et al., 2012). Finally, this study was cross-sectional so the directionality of some effects is not definitively demonstrated and there may be dynamic relations between stress and self-regulation over time (cf. Gibbons et al., 2012; Simons et al., 2015). Longitudinal research would be desirable to test for reciprocal relationships among constructs and address the full complexity of relations between self-control and symptomatology.

4.4. Conclusions

Emotional regulation was found to be quite relevant for the processes that produce early vulnerability versus resilience to substance use. This was observed at an age when few if any participants had developed a disorder; therefore, emotion regulation differences precede the onset of disorder. Emotional self-control and emotional dysregulation had independent effects hence are distinct constructs and not simply opposite ends of one dimension. Emotion regulation operates in part through influencing exposure to intermediate risk and protective factors, which points out several pathways for preventive intervention.

Highlights.

Emotional self-control and dysregulation were assessed before onset of substance use disorder.

Self-control and dysregulation made independent contributions to known predictors of disorder.

Emotional regulation measures were related to several risk/protective factors for substance use.

Emotional regulation measures had both indirect effects and direct effects to outcomes.

Deficits in emotional regulation are antecedent to the development of substance use disorder.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Superintendent of the Hawaii Department of Education and the Principals of the schools for their support, the participating parents and students for their cooperation, and Zalydmar Cortez, Russel Fisher, Melissa Jasper, and Mercedes Harwood-Tappé for their able assistance with data collection.

Role of funding sources

This research was supported by grant R01 DA021856 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (TW). Preparation of the manuscript was supported in part by grant P30 CA071789 from the National Cancer Institute (TW), grant R01 AA020519 from the National Institute on Alcohol abuse and Alcoholism (JS), and grants R01 DA020138 and R01 DA 033296 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (SS). The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health. The study sponsors had no role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; writing of the report; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

Thomas Wills conceptualized and supervised the study, analyzed the data, drafted the manuscript, and coordinated the submission of the final manuscript. Jeffrey Simons and Steve Sussman assisted in the design of the study and reviewed the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Rebecca Knight supervised the data collection and data processing and reviewed the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

No conflicts declared.

Contributor Information

Thomas A. Wills, Email: twills@cc.hawaii.edu.

Jeffrey S. Simons, Email: jeffrey.simons@usd.edu.

Steve Sussman, Email: ssussma@usc.edu.

Rebecca Knight, Email: rknight@cc.hawaii.edu.

REFERENCES

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Youth Self-report and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010;30:217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Kassel J. Adolescent smoking and depression: evidence for self-medication and peer smoking mediation. Addiction. 2009;104:1743–1756. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02617.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Rodgers K, Cuevas J. Declining alternative reinforcers link depression to young adult smoking. Addiction. 2011;106:178–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03113.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Tercyak KP, Nenner G, Moss HB. The impact of self-control indices on peer smoking and adolescent smoking progression. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2006;21:139–151. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Leventhal AM, Cuevas J, Rodgers K, Sass J. Low hedonic capacity predicts smoking onset and escalation. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2012;14:1187–1196. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berking M, Margraf M, Ebert D, Wupperman P, Hofmann SG, Junghannis K. Deficits in emotion regulation skills predict alcohol use during and after cognitive behavioral therapy for alcohol dependence. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2011;79:307–318. doi: 10.1037/a0023421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berking M, Wupperman P. Emotion regulation and mental health: recent findings, current challenges, and future directions. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2012;25:128–134. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283503669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman ET, Graham AM, Fisher PA. Training self-control: a domain-general neuroscience approach. Child Dev. Perspect. 2012;6:374–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, Boden MT, Gross JJ. Posttraumatic stress, difficulties in emotion regulation, and coping marijuana use. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2011;40:34–44. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2010.525253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener ND, Billy JOG, Grady WR. Assessment of factors affecting the validity of self-reported health risk behavior among adolescents: evidence from the scientific literature. J. Adolesc. Health. 2003;33:436–457. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer JA, Elwafi HM, Davis JH. Craving to quit: psychological models and neurobiological mechanisms of mindfulness training as treatment for addictions. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2013;27:366–379. doi: 10.1037/a0028490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Ge X. Linking parenting processes and self-regulation to psychological functioning and alcohol use during early adolescence. J. Fam. Psychol. 2001;2001:82–94. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Whiteman M, Cohen P, Shapiro J, Balka E. Longitudinally predicting late adolescent and young adult drug use: childhood and adolescent precursors. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 1995;34:1230–1238. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199509000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant AL, Schulenberg J, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. How academic achievement and attitudes relate to the course of substance use during adolescence. J. Res. Adolesc. 2003;13:361–397. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SA. Origins and outcomes of individual differences in emotion regulation. Monog. Soc. Res. Child Devel. 1994;59:53–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Pitts SC, DeLucia C, Todd M. A longitudinal study of children of alcoholics: predicting oung adult substance usedisorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1999;108:106–119. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheetham A, Allen NB, Yücel M, Lubman DI. The role of affective dysregulation in drug addiction. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010;30:621–634. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Chassin LM. Affectivity and impulsivity: temperamental risk for alcohol involvement. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 1997;11:83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Chassin L, Lee MR, Villalta IK. Developmental perspectives: affect and adolescent substance use. In: Kassel JD, editor. Substance Abuse and Emotion. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 109–135. [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Scalco M, Trucco EM, Read JP, Lengua LJ, Wieczorek WF, Hawk LW. Prospective associations of externalizing and internalizing problems and their cooccurrence with early adolescent substance use. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2013;41:667–677. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9701-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, O’Leary-Barrett M, Newton N, Toper L, Castelanos-Ryan N, Mackie C, Girard A. Selective personality-targeted prevention program for adolescent alcohol use and misuse: a cluster randomized controlled trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:334–342. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MS, Smith GT, Spillane NS, Fischer S, Annus AM, Peterson C. Development of a measure of positive urgency. Psychol. Assess. 2007;19:107–118. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawe S, Loxton NJ. The role of impulsivity in the development of substance use and eating disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2004;28:43–351. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A, Lee K. Interventions shown to aid executive function development in children 4 to 12 years old. Science. 2011;333:959–964. doi: 10.1126/science.1204529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA. Emotion regulation and the development of social competence. In: Clark MS, editor. Review of Personality and Social Psychology (Vol. 14): Emotion and Social behavior. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1992. pp. 119–150. [Google Scholar]

- Elwafi HM, Witkiewitz K, Mallik S, Thornhill TA, Brewer JA. Mindfulness training for smoking cessation: moderation of the relationship between craving and cigarette use. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 2013;130:222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund MM, Egeland B, Oliva EM, Collins WA. Childhood and adolescent predictors of heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders in early adulthood: a longitudinal developmental analysis. Addiction. 2008;103(Suppl. 1):23–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ersche KD, Williams GB, Robbins TW, Bullmore ET. Meta-analysis of structural brain abnormalities associated with stimulant drug dependence and neuroimaging of addiction vulnerability and resilience. Curr. Opinion Neurobiol. 2013;23:615–624. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farley JP, Kim-Spoon J. The development of adolescent self-regulation: reviewing the role of parent and peer relationships. J. Adolesc. 2014;37:433–440. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM. Conduct and attentional problems in childhood and adolescence and later substance use, abuse, and dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:S14–S26. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Hong KA, Sinha R. Difficulties in emotion regulation and impulse control in recently abstinent alcoholics compared with social drinkers. Addict. Behav. 2008;33:388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fucito LM, Juliano LM, Toll BA. Cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression emotion regulation strategies in cigarette smokers. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2010;12:1156–1161. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Gano M. Adolescents’ risk perceptions and behavioral willingness: implications for intervention. In: Romer D, editor. Reducing Adolescent Risk: Toward an Integrated Approach. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 2003. pp. 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Houlihan AE, Stock ML, Pomery EA. A dual-process approach to health risk decision making. Devel. Rev. 2008;28:29–61. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, O’Hara RE, Stock ML, Gerrard M, Weng C-Y, Wills TA. The erosive effects of racism: reduced self-control mediates the relation between racial discrimination and substance use in African American adolescents. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012;102:1089–1104. doi: 10.1037/a0027404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Stock ML, Gerrard M, Finneran S. The prototype-willingness model. In: Conner M, Norman P, editors. Predicting and Changing Health Behaviour: Research and Practice with Social Cognition Models. 3rd. Berkshire, UK: Open University Press; 2015. pp. 189–224. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Houlihan AE, Gerrard M. Reason and reaction: the utility of a dual-focus perspective on prevention of adolescent health risk behavior. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2009;14:231–248. doi: 10.1348/135910708X376640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert KE. The neglected role of positive emotion in adolescent psychopathology. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2012;32:467–481. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND. Dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex in addiction: neuroimaging findings and clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Neurosc. 2011;12:652–669. doi: 10.1038/nrn3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A. Substance use and common mental health problems: examining longitudinal associations in a British sample. Addiction. 2010;105:1484–1496. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Hawkins JD, Hill KG, Abbott RD. Childhood and adolescent predictors of alcohol abuse and dependence in young adulthood. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2001;62:754–762. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertel PT, Mathews A. Cognitive bias modification: past perspectives, current findings, and future applications. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011;6:521–536. doi: 10.1177/1745691611421205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman W, Friese M, Strack F. Impulse and self-control from a dual-systems perspective. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2009;4:162–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houben K, Schoenmakers TM, Wiers RW. I didn’t feel like drinking but I don’t know why: the effects of evaluative conditioning on alcohol-related attitudes, craving and behavior. Addict. Behav. 2010;35:1161–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isasi CR, Ostrovsky NW, Wills TA. The association of emotion regulation with lifestyle behaviors among inner-city adolescents. Eating Behav. 2013;14:518–521. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor S. Problem Behavior and Psychosocial Development. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Hussong AM, Wardle MC, Veilleux JC, Heinz A, Greenstein JE, Evatt DP. Affective influences in drug use etiology. In: Scheier L, editor. Handbook of Drug Use Etiology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 183–205. [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Veilleux JC. Introduction: the complex interplay between substance abuse and emotion. In: Kassel JD, editor. Substance Abuse and Emotion. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Wilcox LE. Self-control in children: development of a rating scale. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1979;47:1020–1029. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.6.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ. Self-regulation and self-medication factors in alcoholism and the addictions. In: Galanter M, editor. Recent Developments in Alcoholism. Vol. 8. New York: Plenum Press; 1990. pp. 255–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King KM, Chassin L. Adolescent stressors, psychopathology, and young adult substance dependence: a prospective study. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69:629–638. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King SM, Iacono WG, McGue M. Childhood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology in the prediction of early substance use. Addiction. 2004;99:1548–1559. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kober H. Emotion regulation in substance use disorders. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook Of Emotion Regulation. 2nd. New York: Guilford; 2014. pp. 428–446. [Google Scholar]

- Lejeuz CW, Magidson JF, Mitchell SH, Sinha R, Stevens MC, de Wit H. Behavioral and biological indicators of impulsivity in the development of alcohol use, problems, and disorders. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2010;34:1334–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman MD. Social cognitive neuroscience: a review of core processes. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2007a;58:259–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman MD. The X- and C-systems: the neural basis of automatic and controlled social cognition. In: Harmon-Jones E, Winkelman P, editors. Integrating Biological and Psychological Explanations of Social behavior. New York: Guilford; 2007b. pp. 290–315. [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Bickel WK. Impulsivity: The Behavioral and Neurological Science of Discounting. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Martin LR, Friedman HS, Schwartz JE. Personality and mortality across the life span: the importance of conscientiousness. Health Psychol. 2007;26:428–436. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.4.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maskowsky J, Schulenberg JE, Zucker RA. Influence of conduct problems and depressive symptomatology on adolescent substance use: developmentally proximal versus distal effects. Dev. Psychol. 2014;50:1179–1189. doi: 10.1037/a0035085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meda SA, Stevens MC, Potenza MN, Pittman B, Gueorguieva R, Andrews MM, Thomas AD, Muska C, Hylton JL, Pearlson GD. Investigating behavioral and self-report constructs of impulsivity using principal component analysis. Behav. Pharmacol. 2009;20:390–399. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32833113a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe J, Mischel W. A hot/cool-system analysis of delay of gratification: the dynamics of willpower. Psychol. Rev. 1999;106:3–19. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Arsenault L, Belsky D, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, Houts R, Poulton R, Roberts BW, Ross S, Sears MR, Thomson WM, Caspi A. A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:2693–2698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010076108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr C, Armeli S, Tennen H, Todd M. The complexities of modeling mood-drinking relationships: lessons learned from daily process research. In: Kassel JD, editor. Substance Abuse and Emotion.: American Psychological. Washington, DC: Association; 2010. pp. 189–216. [Google Scholar]

- Muraven M. Practicing self-control lowers the risk of smoking lapse. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2010;24:446–452. doi: 10.1037/a0018545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus User’s Guide. Los Angeles, CA: Author; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pardini D, White HR, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Early adolescent psychopathology as a predictor of alcohol use disorders in young adulthood. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:S38–S49. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham JA, Cheong J-W, Balhorn ME, Nagoshi CT. A model of parenting styles, self-regulation, perceived drinking control, and alcohol use and problems. Alcohol. Exp. Clin. Res. 2001;25:1284–1292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick DL, Cheadle A, Thompson D, Diehr P, Koepsell T, Kinne S. The validity of self-reported smoking. Am. J. Public Health. 1994;84:1086–1093. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.7.1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JL, Carroll ME. The role of impulsive behavior in drug abuse. Psychopharmacology. 2008;200:1–26. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulkkinen L, Pitkänen T. A prospective study of the precursors to problem drinking in young adulthood. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1994;55:578–587. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B, Ortengren A, Richards JB, de Wit H. Dimensions of impulsive behavior: personality and behavioral measures. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2006;40:305–315. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Xing Y. Comorbidity of substance use disorders and other psychiatric disorders among adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:S4–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Evans DE. Temperament and personality: origins and outcomes. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000;78:122–135. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.78.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Sheese E, Posner MI. Temperament and emotion regulation. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. 2nd. New York: Guilford; 2015. pp. 305–320. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Dunn J, Plomin R, Simonoff E, Pickles A, Eaves L. Integrating nature and nurture. Dev. Psychopathol. 1997;9:335–364. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497002083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalco M, Colder CR, Hawk LW, Read JP, Wieczorek WF, Lengua LJ. Internalizing and externalizing problem behavior and early adolescent substance use: a test of a latent variable interaction model and conditional indirect effects. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2014;23:828–840. doi: 10.1037/a0035805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier LA, editor. Handbook of Adolescent Drug Use Prevention: Research, Intervention, and Practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL. An evaluation of externalizing symptoms and depressive symptoms as predictors of alcoholism. J. Stud. Alcohol. 2006;67:215–277. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel J. Stop Overreacting: Effective Strategies For Calming Your Emotions. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Carey KB. Risk and vulnerability for marijuana use problems: the role of affect dysregulation. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2002;16:72–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Carey KB, Wills TA. Alcohol abuse and dependence: multidimensional model of common and specific etiology. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2009;23:415–427. doi: 10.1037/a0016003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Dvorak RD, Batien BD, Wray TB. Event-level associations between affect, alcohol intoxication, and acute dependence symptoms: effects of urgency, self-control, and drinking experience. Addict. Behav. 2010;35:1045–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Wills TA, Emery NN, Spellman P. Keep calm and carry on: maintaining self-control when intoxicated, upset, or depleted. Cogn. Emot. 2015 doi: 10.1080/02699931.2015.1069733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Wills TA, Neal DJ. The many faces of affect: a multilevel model of drinking frequency/quantity and alcohol dependence symptoms among young adults. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2014;123:676–694. doi: 10.1037/a0036926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2008;1141:105–130. doi: 10.1196/annals.1441.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KS, Graybiel AM. A dual-operator view of habitual behavior reflecting cortical and striatal dynamics. Neuron. 2013;79:361–374. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southam-Gerow MA, Kendall PC. Emotional regulation and understanding: implications for child psychopathology. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2002;22:189–222. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00087-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southam-Gerow MA. Emotion Regulation In Children And Adolescents: A Practitioner’s Guide. New York: Guilford; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Risk taking in adolescence: new perspectives from brain and behavioral science. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2007;16:55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S, Ames SL. Drug Abuse: Concepts, Prevention, and Cessation. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S, McCuller WJ, Dent C. The association of social self-control and personality disorders with drug use in a sample of high risk youth. Addict. Behav. 2003;28:1159–1166. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00222-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S, Pokhrel P, Ashmore RD, Brown BB. Adolescent peer group identification and characteristics: a review of the literature. Addict. Behav. 2007;32:1602–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter R, Kirisci L, Mezzich A, Cornelius J, Pajer K, Vanyukov M, Gardner W, Blackson T, Clark D. Neurobehavioral disinhibition in childhood predicts early onset of substance use disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2003;160:1078–1085. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Feske U, Vanyukov M. Modeling the pathways linking childhood hyperactivity and substance use disorder in young adulthood. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2007;21:266–271. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.2.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter R, Vanyukov M, Giancola P, Dawes M, Blackson T, Mezzich A, Clark D. Etiology of early age onset substance use disorder: A maturational perspective. Dev. Psychopathol. 1999;11:657–683. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursache A, Blair C, Raver CC. The promotion of self-regulation as a means for enhancing school readiness and early achievement in children at risk for school failure. Child Devel. Perspect. 2012;6:122–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veit CT, Ware JE. Structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1983;51:730–742. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.5.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Baler RD. To stop or not to stop? Science. 2012;335:546–548. doi: 10.1126/science.1218170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler J, Wang G, Telang F, Logan J, Jayne M, Ma Y, Pradhan K, Wong C, Swanson JM. Cognitive control of drug craving inhibits brain reward regions in cocaine abusers. Neuroimage. 2010;49:2536–2543. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb TL, Miles E, Sheeran P. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of strategies derived from the process model of emotion regulation. Psychol. Bull. 2012;138:775–808. doi: 10.1037/a0027600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein SM, Mermelstein M. Dynamic associations of negative mood and smoking in the development of smoking in adolescence. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2013a;42:629–642. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.794698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein SM, Mermelstein RJ. Influences of mood variability and negative moods, and depression on adolescent smoking. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2013b;27:1068–1078. doi: 10.1037/a0031488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiers R, Bartholow B, van den Wildenberg E, Thush C, Engels R, Sher K, Grenard J, Ames S, Stacy A. Automatic and controlled processes and the development of addictive behaviors in adolescents. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2007;86:263–283. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiers RW, Eberl C, Rinck M, Becker ES, Lindenmeyer J. Retraining automatic action tendencies changes alcohol patients’ approach bias for alcohol and improves treatment outcome. Psychol. Sci. 2011;22:490–497. doi: 10.1177/0956797611400615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Xie M, Thompson W, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Psychopathology as a predictor of adolescent drug use trajectories. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2001;15:210–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Ainette MG. Temperament, self-control, and adolescent substance use: a two-factor model of etiological processes. In: Scheier LM, editor. Handbook of Drug Use Etiology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 127–146. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Ainette MG, Mendoza D, Gibbons FX, Brody GH. Self-control, symptomatology, and substance use precursors: test of a theoretical model in a community sample of 9-year-old children. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2007b;21:205–215. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Ainette MG, Stoolmiller M, Gibbons FX, Shinar O. Good self-control as a buffering agent for adolescent substance use: an investigation in early adolescence with time-varying covariates. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2008;22:459–471. doi: 10.1037/a0012965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Bantum EO, Pokhrel P, Maddock JE, Ainette MG, Morehouse E, Fenster B. A dual-process model of early substance use: tests in two diverse populations of adolescents. Health Psychol. 2013;32:533–542. doi: 10.1037/a0027634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Cleary SD, Filer M, Shinar O, Mariani J, Spera K. Temperament related to early-onset substance use: test of a developmental model. Prev. Sci. 2001a;2:145–163. doi: 10.1023/a:1011558807062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Dishion T. Temperament and adolescent substance use: an analysis of emerging self-control. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2004;33:69–81. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Forbes M, Gibbons FX. Parental and peer support: an analysis of their relations to adolescent substance use. In: Scheier LW, Hansen WB, editors. Parenting and Teen Drug Use. New York: Oxford; 2014. pp. 148–165. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Brody G. Protection and vulnerability processes for early substance use: a test among African-American children. Health Psychol. 2000a;19:253–263. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Knight R, Williams R, Pagano I, Sargent JD. Risk factors for E-igarette use and dual E-cigarette and tobacco use in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2015a;135:e43–e51. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Murry V, Brody G, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Walker C, Ainette M. Ethnic pride, self-control, and protective/risk factors. Health Psychol. 2007a;26:50–59. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Pokhrel P, Morehouse E, Fenster B. Behavioral and emotional regulation and adolescent substance use problems: a test of moderation effects in a dual-process model. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2011;25:279–292. doi: 10.1037/a0022870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Resko J, Ainette M, Mendoza D. The role of parent and peer support in adolescent substance use: a test of mediated effects. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2004a;18:122–134. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Resko J, Ainette M, Mendoza D. Smoking onset in adolescence: a person-centered analysis with time-varying predictors. Health Psychol. 2004b;23:158–167. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Shinar O. Cloninger’s constructs related to substance use level and problems in late adolescence: a mediational model based on self-control and coping motives. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1999a;7:122–134. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.2.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Shinar O, Yaeger A. Contributions of positive and negative affect to adolescent substance use. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 1999b;13:327–338. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Yaeger A. Temperament and adolescent substance use: an epigenetic approach to risk and protection. J. Pers. 2000b;68:1127–1152. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Yaeger A. Time perspective and early-onset substance use: a model based on stress-coping theory. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2001b;15:118–125. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.2.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Yaeger A. Moderators of the relation between substance use level and problems: test of a self-regulation model. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2002a;111:3–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Yaeger AM. Stress and smoking in adolescence: a test of directional hypotheses with latent growth analysis. Health Psychol. 2002b;21:122–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sandy JM, Yaeger AM, Cleary SD, Shinar O. Coping, life stress, and adolescent substance use: a latent growth analysis. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2001c;110:309–323. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Simons JS, Gibbons FX. Self-control and substance use prevention. In: Scheier LA, editor. Handbook of Adolescent Drug Use Prevention: Research, Intervention, and Practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2015b. pp. 121–139. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Stoolmiller M. Role of self-control in early escalation of substance use: a time-varying analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2002;70:986–997. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Walker C, Mendoza D, Ainette MG. Behavioral and emotional self-control: relations to substance use in samples of middle- and high-school students. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2006;20:265–278. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Walker C, Resko JA. Longitudinal studies of drug use and abuse. In: Sloboda Z, editor. Epidemiology of Drug Abuse. New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 177–192. [Google Scholar]

- Windle M. A longitudinal study of antisocial behaviors in early adolescence as predictors of late adolescent substance use. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1990;99:86–91. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen H-U, Fröhlich C, Behrendt S, Günther A, Rehm J, Zimmerman P, Lieb R, Perkonigg R. Cannabis use and disorders and their relation to mental disorders: a 10-year prospective-longitudinal study in adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:S60–S70. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeman J, Shipman K, Penza-Clyve S. Development and validation of the Children’s Sadness Management scale. J. Nonverbal Behav. 2001;25:187–205. [Google Scholar]

- Zimbardo PG, Boyd JN. Time perspective: a valid, reliable individual-differences metric. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999;77:1271–1288. [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A, Vujanovic AA. Distress Tolerance: Theory, Research, And Clinical Applications. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]