Abstract

Calcium ion is an intracellular messenger that plays a central role in signal transduction pathways. Calcineurin B-like proteins (CBLs) and CBL-interacting protein kinases (CIPKs) signal network have shown different functions in the Ca2+ signaling process. In this work, we identified the entire soybean (Glycine max) CIPK gene family, which comprised 52 genes and divided into four subgroups (I to IV) based on phylogeny. The gene structural analysis separated these 52 genes into an intron-rich clade and an intron-poor clade. Chromosomal location analysis resulted in the identification of 22 duplicated blocks and six tandem duplication events. Phylogenetic classification of 193 CIPK proteins from representative plant species suggested that the intron-poor clade of CIPKs originated in seed plants. Analysis of global gene expression patterns of soybean CIPK family revealed that most intron-poor soybean CIPK genes are drought-inducible; a finding that was further confirmed using qRT-PCR. Our study provides a foundation for further functional analysis to reveal the roles that CIPKs and more specifically the intron-poor clade play in drought tolerance in soybean.

Soybean (Glycine max) is one of the most important legume crops for edible oil and protein source for human consumption and animal feed1. However, environmental factors such as drought, salt, heat and heavy metals may severely affect soybean growth and crop production2. Among those environmental stresses drought can severely inhibit all stages of soybean growth and productivity.

Global climate changes, driven by greenhouse gas emissions, can induce severe drought3,4. To cope with drought, higher plants have developed numerous mechanisms in responding to drought stress. Several genome-wide gene expression profiling pointed to a role of various protein kinase gene families in providing an efficient, fast-acting, and reversible response to drought stress5,6,7,8,9.

Calcium is an important signaling messenger in the course of plant response to environmental stresses and plant growth and development10. Four major Ca2+ sensors have been identified in Arabidopsis, including calcium-dependent protein kinase (CDPK), calcineurin B-like protein (CBL), calmodulin (CAM), and calmodulin-like protein (CML)11. With the exception of CDPKs, which contain a kinase domain, the other three Ca2+ sensors had no enzymatic domain, implying a role of their interactors in transmitting cellular signals to their downstream targets. CBLs modulate the activity of CBL-interacting protein kinases (CIPKs), also known as sucrose non-fermenting 1 related kinase 3 (SnRK3)12. CIPK family members frequently have a serine/threonine protein kinase domain in the N-terminus and a self-inhibitory NAF domain in C-terminus13. Activation of CIPKs is frequently mediated through the interaction of NAF domain with CBLs14.

The CBL and CIPK proteins form a calcium decoding signaling network and play an important role in plant responses to abiotic stresses. Among the 26 CIPK genes identified in Arabidopsis, several genes have been characterized15. For example, AtCIPK24 (known as Arabidopsis SOS2) and AtCBL4 (known as Arabidopsis SOS3) contribute to salt stress by activating the Na+/H+ antiporter, AtSOS1 in order to maintain Na+ at low level16. AtCBL1 and AtCBL9 were reported to form a complex with AtCIPK23 to regulate potassium homeostasis under low potassium stress17. A role of AtCIPK7 in cold tolerance has been reported18. Certain CIPKs in other plant species have also been characterized. For example, overexpression of OsCIPK23 improved rice drought tolerance by enhancing the expression level of drought-related genes19. A cotton CIPK gene, GhCIPK6, was induced by drought, and was found to enhance plant tolerance to drought when was overexpressed in Arabidopsis20. These findings suggest that CIPK family plays important roles bringing about plant tolerance to environmental stresses.

The CIPK gene family has been analyzed in Arabidopsis21,22, poplar (Populus trichocarpa)22, maize (Zea mays)23, rice (Oryza sativa)24, and canola (Brassica napus)25. These studies reported that the CIPK gene family could be divided into an intron-rich clade and an intron-poor clade, in which a subgroup in Arabidopsis, maize, rice and canola CIPK genes were induced by drought23,24,25,26. Although soybean (Glycine max var. Williams 82) has been sequenced1, no specific study has been reported on characterization of the CIPK gene family at the genome level to obtain a general perspective into their potential biological functions, especially in response to drought stress. In this study, we identified 52 soybean CIPK family members and found that intron-poor CIPK genes might be originated in seed plants. We also analyzed the gene expression patterns of the CIPK genes using publicly available microarray data and found that several CIPK genes are drought-inducible, from which 18 genes were confirmed using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). Taken together, our data implicate soybean CIPK gene family in drought tolerance and point into several candidate genes for further functional characterization towards improving drought tolerance in soybean.

Materials and Methods

Genome-wide identification of CIPK gene family in soybean

To identify soybean CIPK proteins, all protein sequences were downloaded from the soybean genome (Wm82.a2.v1) from Phytozome V10 (http://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html#!info?alias=Org_Gmax). Hidden Markov Models were used to search for putative soybean CIPK proteins. A HMM profile of the NAF domain (PF03822), the signature domain of CIPKs, was first downloaded from Pfam (http://pfam.xfam.org/)27 and used to search for soybean CIPKs by HMMER 3.028. Each CIPK candidate sequence was examined for the presence of the NAF domain and protein kinase domain to be considered as a member of soybean CIPK family. The putative CIPK family members were further examined using Pfam and SMART domain detection softwares (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/smart/set_mode.cgi?GENOMIC=1)29. Molecular weight (MW) and isoelectric point (pI) of each protein sequence were calculated using ExPASy (http://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/)30.

Multiple alignment and phylogenetic tree construction

The protein sequences of all the 52 GmCIPK family members were aligned with ClustalX and constructed using Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method by MEGA6.0631. The bootstrap values for phylogenetic tree were based on 1000 replicates. Protein sequences from soybean, Arabidopsis, grape, rice, amborella, gymnosperm plants (pine, gnetum, ephedra, welwitschia and ginkgo), spikemoss, fern, moss and green algae were aligned with ClustalX. The phylogenetic tree was constructed with MEGA6.06 using the NJ method, and bootstrap analysis using 1000 replicates with the pairwise deletion and Poisson model.

Exon-Intron structure analysis and identification of conserved motifs

Gene structure analysis of GmCIPK subgroup was performed using Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS 2.0, http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/)32 by aligning the cDNAs with the corresponding genomic DNA sequences. Motifs analysis was performed with the MEME program (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme)33. The parameters were as follows: number of repetitions, any; maximum numbers of motifs, 30; and the optimum motif widths, between 6 and 200 residues.

Chromosomal location and gene duplication

The chromosomal location image of soybean CIPK genes was generated by Mapchart 2.30 (www.wageningenur.nl/en/show/Mapchart-2.30.htm). The chromosomal position information of soybean CIPK genes was collected from the phytozome database (http://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html). Duplication patterns of GmCIPK genes were assigned based on their locations. The tandem duplicated genes were defined as an array of two or more genes located on the same chromosome and separated by five or fewer genes in a 100-kb region34. Genes located on duplicated chromosomal blocks were considered as segmental duplication. The information for segmental duplication was obtained from the SoyBase browser (http://soybase.org/gb2/gbrowse/gmax2.0/)35.

Microarray analysis of soybean CIPK genes expression

Gene expression pattern of soybean CIPK gene family under drought stress, were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The two microarray data sets represented expressions of 48 CIPK genes in soybean leaves at a vegetative stage (GSE29663) and a reproductive stage (GSE40604) under drought. The heatmap of soybean CIPKs was generated using Multi experiment viewer 4.8 (MeV 4.8) software (http://www.tm4.org/mev.html)36.

Plant materials, growth conditions and drought treatment

Soybean (var. Williams 82) was used in this study. Soybean seedlings were grown in a growth chamber at 25 °C with a photoperiod of 12 h/12 h, and a light intensity of 180 μmol m−2 s−1. The seedlings were watered every two days before drought treatment20. At 15 days post germination, drought treatment was initiated and this was set as the 0 day of drought treatment. Leaves, stems and roots samples were collected at 0, 4, 8 and 12 days, respectively, after as the initiation of drought stress (Figure S2). Control seedlings were continuously watered every two days. The collected samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately and stored at −80 °C for further analysis. Three biological replicates, each contained three plants, were used for each treatment or control.

RNA extraction and gene expression assay by qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from leaves, stems and roots using the PureLink Plant RNA Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then RNA was treated with DNase I (RNase-free DNase set, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) to eliminate trace of DNA, and RNA quality and concentration were measured using NanoDrop 1000 (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE). First strand cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg total RNA using cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA) with RNase Inhibitor (RNase out, Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Specific primers for the 18 soybean CIPK genes (Table S1) were designed using Primer 3 software (http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3/). Ribosomal protein s20e gene (RSP s20e, Glyma.03G142300) was used as a reference gene37. The real-time qRT-PCR was conducted using a Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA) on an ABI 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA). The PCR reactions were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The PCR conditions were as follows: 95 °C 10 min, 40 cycles of 15 sec at 95 °C and 1 min at 60 °C, at the end, the melting curve analysis was executed for verifying the specificity of the primer with the following stage: 95 °C for 15 sec, 60 °C for 1 min, 95 °C for 15 sec. Three biological replicates were used per treatment or control. Quantification of gene expression changes in stressed plants relative to control were performed using the 2−ΔΔCT method38.

Statistical analysis

Values are means ± SE of three different experiments with three replicated measurements. Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t test (P < 0.05).

Results

Soybean genome encodes 52 CIPK genes

We identified 52 CIPK gene family members (GmCIPK1 to GmCIPK52) that contain both NAF and kinase domains, the characteristic features of CIPK proteins (Table 1). The 52 CIPK genes are distributed across 19 chromosomes (chromosome 1–20, except chromosome 12) (Table 1). These proteins range in size between 306 to 528 amino acids. The relative molecular weights of these CIPK kinase proteins varied from 35.14 to 59.71 kD. Most of these proteins (82.69%) have high isoelectric points (pI > 7.0). The detail information about other parameters was provided in Table 1.

Table 1. List of 52 CIPK genes identified in soybean and their sequence characteristics.

| Name | Gene ID (phytozome) | Chromosomal localization | Gene length (bp) | Amino acid length (aa) | PI | MW (kD) | Exons | CDS length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GmCIPK1 | Glyma.01g131500 | Gm01: 44789012–44792912 | 3901 | 467 | 8.69 | 52.85 | 1 | 1404 |

| GmCIPK2 | Glyma.02g202900 | Gm02: 38802831–38805349 | 2519 | 430 | 9.10 | 48.36 | 1 | 1293 |

| GmCIPK3 | Glyma.02g217300 | Gm02: 40416767–40423408 | 6642 | 444 | 6.11 | 50.45 | 14 | 1335 |

| GmCIPK4 | Glyma.02g234800 | Gm02: 42228835–42231757 | 2923 | 463 | 8.85 | 52.87 | 1 | 1392 |

| GmCIPK5 | Glyma.02g235100 | Gm02: 42255452–42257724 | 2273 | 442 | 7.12 | 49.25 | 1 | 1329 |

| GmCIPK6 | Glyma.02g275900 | Gm02: 45882082–45889538 | 7457 | 472 | 8.06 | 53.77 | 13 | 1419 |

| GmCIPK7 | Glyma.03g036900 | Gm03: 4497651–4498973 | 1323 | 413 | 8.63 | 46.46 | 3 | 1242 |

| GmCIPK8 | Glyma.03g260200 | Gm03: 45407900–45415032 | 7133 | 440 | 8.45 | 49.93 | 12 | 1323 |

| GmCIPK9 | Glyma.04g061500 | Gm04: 5015260- 5017719 | 2460 | 434 | 8.96 | 48.78 | 2 | 1305 |

| GmCIPK10 | Glyma.04g090500 | Gm04: 7961747–7967803 | 6057 | 446 | 6.65 | 50.80 | 14 | 1341 |

| GmCIPK11 | Glyma.05g158700 | Gm05: 35076361–35078476 | 2116 | 517 | 7.23 | 58.42 | 1 | 1554 |

| GmCIPK12 | Glyma.06g062100 | Gm06: 4677276–4680311 | 3036 | 453 | 8.51 | 50.60 | 1 | 1362 |

| GmCIPK13 | Glyma.06g092300 | Gm06: 7283361–7289264 | 5904 | 446 | 7.16 | 50.81 | 14 | 1341 |

| GmCIPK14 | Glyma.07g023500 | Gm07: 1804676–1807191 | 2516 | 441 | 9.07 | 50.46 | 1 | 1326 |

| GmCIPK15 | Glyma.07g051000 | Gm07: 4401020–4408559 | 7540 | 438 | 8.89 | 49.91 | 14 | 1317 |

| GmCIPK16 | Glyma.08g116500 | Gm08: 8961418–8963555 | 2138 | 528 | 7.24 | 59.71 | 1 | 1587 |

| GmCIPK17 | Glyma.08g218400 | Gm08: 17747795–17750917 | 3123 | 430 | 9.25 | 48.77 | 1 | 1293 |

| GmCIPK18 | Glyma.08g252100 | Gm08: 22112310–22118088 | 5779 | 467 | 9.00 | 53.63 | 10 | 1404 |

| GmCIPK19 | Glyma.09g079400 | Gm09: 8955776–8963586 | 7811 | 448 | 6.26 | 50.53 | 12 | 1347 |

| GmCIPK20 | Glyma.09g089700 | Gm09: 11977305–11986209 | 8905 | 462 | 8.94 | 51.70 | 15 | 1389 |

| GmCIPK21 | Glyma.09g098000 | Gm09: 16564068–16566202 | 2135 | 440 | 9.28 | 49.65 | 1 | 1323 |

| GmCIPK22 | Glyma.09g276600 | Gm09: 49206095–49207881 | 1787 | 438 | 6.15 | 48.82 | 1 | 1317 |

| GmCIPK23 | Glyma.09g277000 | Gm09: 49243593–49247135 | 3543 | 460 | 8.52 | 52.36 | 1 | 1383 |

| GmCIPK24 | Glyma.10g001700 | Gm10: 165788–167599 | 1812 | 431 | 8.90 | 48.12 | 1 | 1296 |

| GmCIPK25 | Glyma.10g179600 | Gm10: 41288232–41290368 | 2137 | 437 | 9.10 | 48.53 | 1 | 1314 |

| GmCIPK26 | Glyma.11g161300 | Gm11: 14868303–14871145 | 2843 | 462 | 8.77 | 52.46 | 1 | 1389 |

| GmCIPK27 | Glyma.11g235300 | Gm11: 33029240–33033627 | 4388 | 452 | 8.73 | 50.88 | 1 | 1359 |

| GmCIPK28 | Glyma.13g069500 | Gm13: 16957654–16960090 | 2437 | 456 | 6.53 | 46.88 | 2 | 1371 |

| GmCIPK29 | Glyma.13g119500 | Gm13: 23212628–23212628 | 5830 | 446 | 8.45 | 50.08 | 12 | 1341 |

| GmCIPK30 | Glyma.13g166100 | Gm13: 28076313–28083963 | 7651 | 446 | 9.01 | 50.82 | 14 | 1341 |

| GmCIPK31 | Glyma.13g228400 | Gm13: 34069476–34071724 | 2249 | 512 | 6.70 | 57.53 | 1 | 1539 |

| GmCIPK32 | Glyma.13g228500 | Gm13: 34080809–34082788 | 1980 | 451 | 9.20 | 51.53 | 1 | 1356 |

| GmCIPK33 | Glyma.13g370000 | Gm13: 45542607–45543980 | 1374 | 425 | 8.87 | 47.35 | 2 | 1278 |

| GmCIPK34 | Glyma.14g040200 | Gm14: 3012174–3018140 | 5967 | 462 | 7.65 | 53.00 | 15 | 1389 |

| GmCIPK35 | Glyma.14g203000 | Gm14: 46787303–46790554 | 3252 | 439 | 7.52 | 48.63 | 1 | 1320 |

| GmCIPK36 | Glyma.15g003400 | Gm15: 309074–311683 | 2610 | 461 | 9.05 | 51.77 | 1 | 1386 |

| GmCIPK37 | Glyma.15g084000 | Gm15: 6435171–6436213 | 1043 | 306 | 8.74 | 35.14 | 2 | 921 |

| GmCIPK38 | Glyma.15g084100 | Gm15: 6445126–6447384 | 2259 | 510 | 6.75 | 57.27 | 1 | 1533 |

| GmCIPK39 | Glyma.15g187400 | Gm15: 19503493–19511425 | 7933 | 437 | 7.58 | 49.17 | 12 | 1314 |

| GmCIPK40 | Glyma.15g203700 | Gm15: 26165280–26167502 | 2223 | 438 | 9.31 | 49.51 | 1 | 1317 |

| GmCIPK41 | Glyma.16g020200 | Gm16: 1828561–1835982 | 7422 | 438 | 9.05 | 49.86 | 14 | 1317 |

| GmCIPK42 | Glyma.17g040700 | Gm17: 3002793–3008282 | 5490 | 448 | 8.75 | 50.39 | 12 | 1347 |

| GmCIPK43 | Glyma.17g066300 | Gm17: 5105100–5109101 | 4002 | 467 | 8.82 | 52.82 | 15 | 1404 |

| GmCIPK44 | Glyma.17g074800 | Gm17: 5871870–5874213 | 2344 | 422 | 9.17 | 47.60 | 1 | 1269 |

| GmCIPK45 | Glyma.17g113700 | Gm17: 8997933–9005687 | 7755 | 446 | 9.06 | 50.83 | 14 | 1341 |

| GmCIPK46 | Glyma.18g021600 | Gm18: 1584996–1589570 | 4575 | 449 | 8.99 | 50.31 | 1 | 1350 |

| GmCIPK47 | Glyma.18g054600 | Gm18: 4749616–4752421 | 2806 | 450 | 6.18 | 50.12 | 2 | 1353 |

| GmCIPK48 | Glyma.18g055000 | Gm18: 4773932–4777530 | 3599 | 462 | 8.80 | 52.40 | 1 | 1389 |

| GmCIPK49 | Glyma.18g212200 | Gm18: 49872222–49875889 | 3668 | 462 | 8.85 | 52.65 | 1 | 1389 |

| GmCIPK50 | Glyma.18g212700 | Gm18: 49942123–49944169 | 2047 | 443 | 6.41 | 49.71 | 1 | 1332 |

| GmCIPK51 | Glyma.19g111300 | Gm19: 36555752–36557117 | 1366 | 426 | 7.99 | 48.84 | 3 | 1281 |

| GmCIPK52 | Glyma.20g210800 | Gm20: 44730135–43731825 | 1691 | 436 | 9.22 | 48.62 | 1 | 1311 |

bp, base pair; aa, amino acids; PI, isoelectric point; MW, molecular weight; kD, kilo Dalton.

Phylogenetic and gene structural analysis of the soybean CIPK gene family

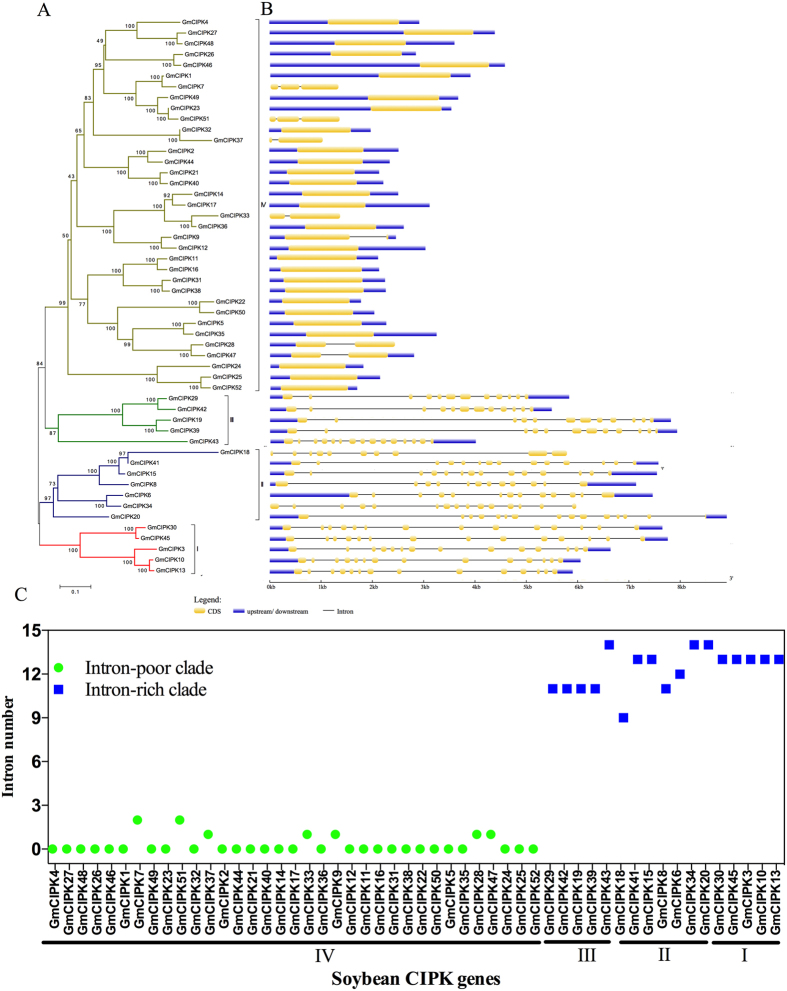

The evolutionary relationship among the 52 soybean CIPK members is shown in Fig. 1A. The phylogenetic analysis classified the 52 CIPK family members into four subgroups; I, II, III and IV (Fig. 1A). Subgroup IV is the largest one and contains 35 members. The other three subgroups contain 17 members in total (5 in subgroup I, 7 in subgroup II, and 5 subgroup III).

Figure 1. Phylogenetic relationship of soybean CIPK proteins and gene structure.

The phylogenetic tree was generated using the MEGA6.06 software with the 52 full-length soybean CIPKs protein sequences (A). Neighbor-joining method was used with 1000 bootstrap replicates. These soybean CIPK genes were divided into four subgroups (I–IV) with different colored branches. Exon and intron analysis was performed using GSDS2.0 (B). The yellow boxes represent exons and the black lines represent introns. The blue boxes represent upstream/downstream-untranslated regions. The scale bars of introns, exons and untranslated regions are included at the bottom of the graph. (C) Classification of CIPK genes into intron-poor clade (green dots) and intron-rich clades (blue squares). Genes with intron number less than 3 were grouped into the intron-poor clade, and genes with intron number more than 8 were grouped into the intron-rich clade.

To further investigate the structural diversity of the CIPK genes in soybean, the exon/intron organization of the GmCIPK genes was analyzed. The GmCIPK gene members were clearly divided into an intron-rich clade (>8 introns per gene) and an intron-poor clade (<3 introns per gene)23,26. All the intron-poor clade members belong to subgroup IV and all intron-rich members relate to subgroup I, II and III (Fig. 1B). In subgroup IV, only GmCIPK7 and −51 contain two introns; GmCIPK9, −28, −33, −37 and −47 contain one intron; the other members in subgroup IV are intronless. Most members in subgroup III contain 11 introns except GmCIPK43, which contains 14 introns. Seven members in subgroup II varied in intron numbers from 9 (GmCIPK18) to 14 (GmCIPK20 and −34). All genes in subgroup I contain 13 introns (Fig. 1C).

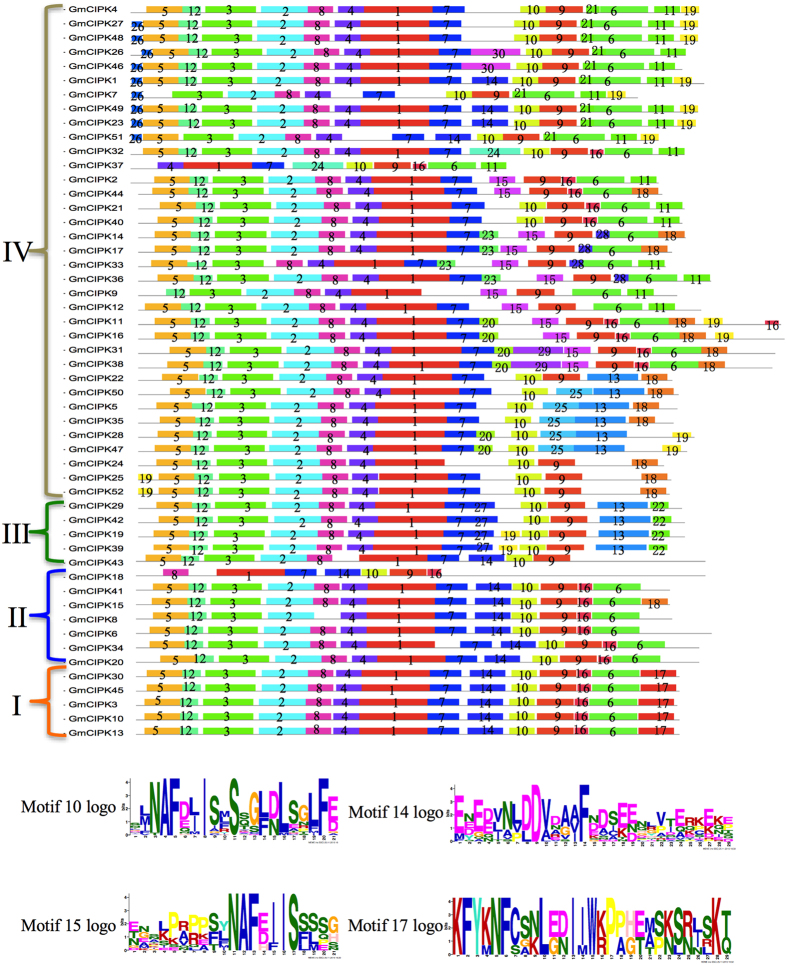

Conserved motifs were also analyzed for all the 52 soybean CIPK proteins using MEME software33. Totally thirty motifs were identified (Fig. 2) and the details of each motif were shown in Figure S1. All soybean CIPK proteins contained motif 10 or motif 15 annotated as the NAF domain. All proteins in subgroup I and II contain motif 14, but only 4 CIPK proteins in the subgroup IV, CIPK1, −23, −49 and −51, have motif 14. Only five proteins all in subgroup I, contain motif 17 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Conserved motifs in soybean CIPK proteins.

The MEME program was used to investigate all relative motifs of soybean CIPK proteins. Each colored box represents a motif in soybean CIPK proteins. The relate name was on the left of each protein and the number of the motifs were showed in the boxes. Sequences logos of motif 10, 14, 15 and 17 were represented. Box length corresponded to motif length. Details of each motif were presented in Figure S1.

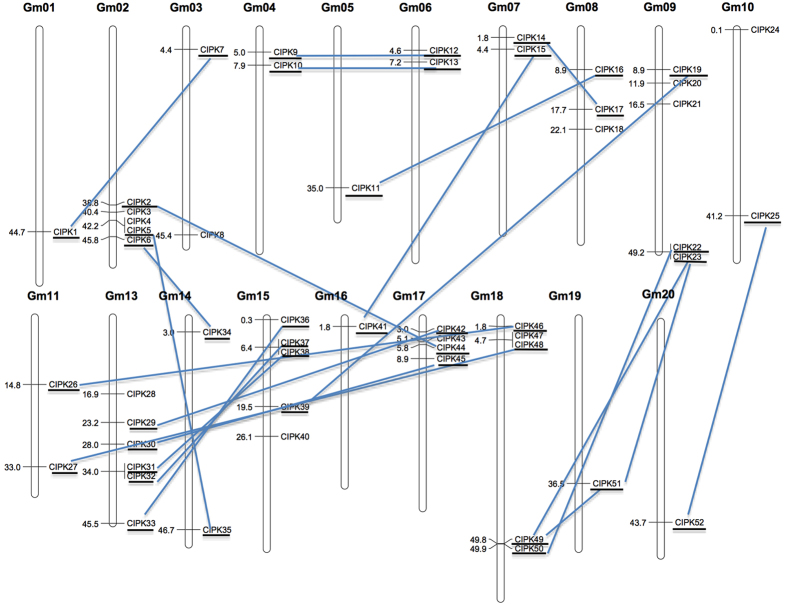

Chromosomal location analysis and gene duplication

To determine chromosomal locations and duplication events, all the 52 CIPK genes were mapped to 19 out of the 20 soybean chromosomes, except chromosome 12 (Fig. 3). The 52 CIPK genes were not distributed evenly in these 19 chromosomes. Chromosomes 1, 5, 16, 19 and 20 contain one CIPK gene, while chromosome 13 contains most CIPK genes (6) among all soybean chromosomes.

Figure 3. Chromosomal locations of soybean CIPK genes.

The 52 soybean CIPK genes were mapped to 19 chromosomes. The duplicated CIPK gene pairs in the segmental duplicated blocks are underlined and connected by lines.

Gene duplication events have driven the expansion of soybean CIPK genes, with 41 genes found in 22 duplicated blocks and only 11 GmCIPK genes located outside of the duplicated blocks (Fig. 3). Six pairs of genes, including GmCIPK4/−5, 22/−23, 31/−32, 37/−38, 47/−48, and 49/−50, were separated by less than a 100-kb region on chromosome 2, 9, 13, 15 and 18, respectively, which were resulted from tandem duplications and were all intron-poor genes.

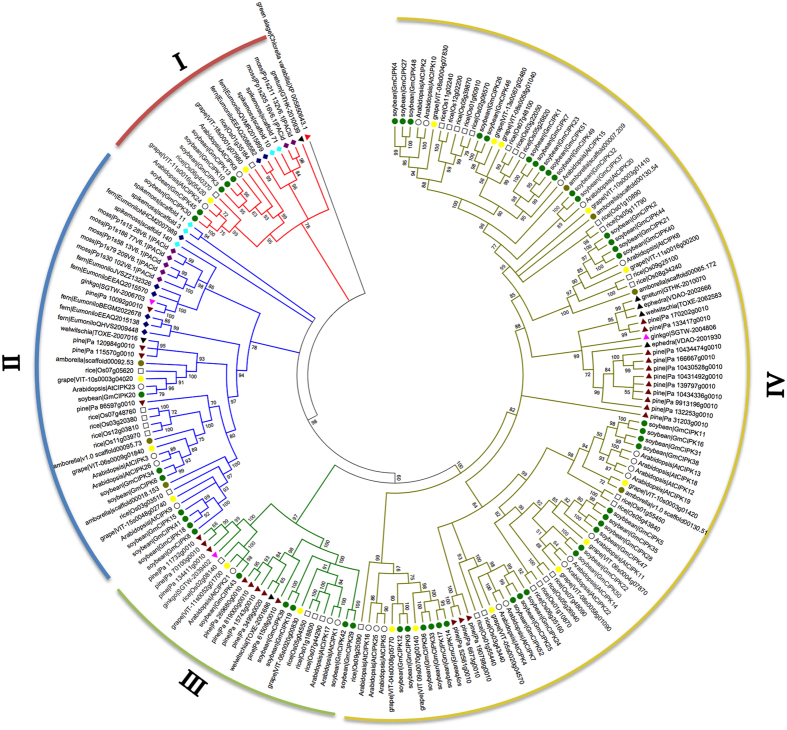

Evolution analysis of CIPK in plants

To investigate the origin and evolution of CIPKs, we built a NJ phylogenetic tree using 193 full-length protein sequences containing a NAF (PF03822) domain from 14 representative plant species. Among the 193 proteins, only one CIPK protein was found in green algae, 7 in moss, 8 in fern, 5 in spikemoss, 26 in pine, 3 in ginkgo, 2 in gnetum, 3 in welwitschia, 2 in ephedra, 33 in rice, 7 in amborella, 18 in grapevine, 26 in Arabidopsis, and 52 in soybean. The CIPK proteins in rice, Arabidopsis, soybean and grapevine, all being angiosperm, were divided into four subgroups (Fig. 4). However, CIPK proteins in a green algae, moss, fern, and spikemoss were all grouped in subgroup I and II. All the 35 soybean intron-poor genes were clustered in subgroup IV (Fig. 1A). In addition, we found that some of gymnosperms plants (pine, ginkgo, gnetum, welwitschia and ephedra), amborella, rice, Arabidopsis and grapevine CIPK genes were assembled in subgroup IV. This result might represent plant intron-poor CIPK genes originated in seed plants.

Figure 4. Evolution analysis of soybean CIPK proteins.

The full-length of 193 CIPK protein sequences from soybean, grape, Arabidopsis, rice, amborella, ginkgo, pine, gnetum, ephedra, welwitschia, fern, spikemoss, moss and green algae were used to construct the phylogenetic tree using MEGA with the Neighbor-joining (NJ) method. Bootstrap values (on nodes) were calculated using 1000 replicates. Subfamilies are highlighted with different colors. The CIPK proteins in soybean were marked by green dots. A green algae CIPK protein was used as an outgroup and marked with a red triangle. Eudicot CIPK proteins were marked with dots. Monocotyledons were marked with squares.

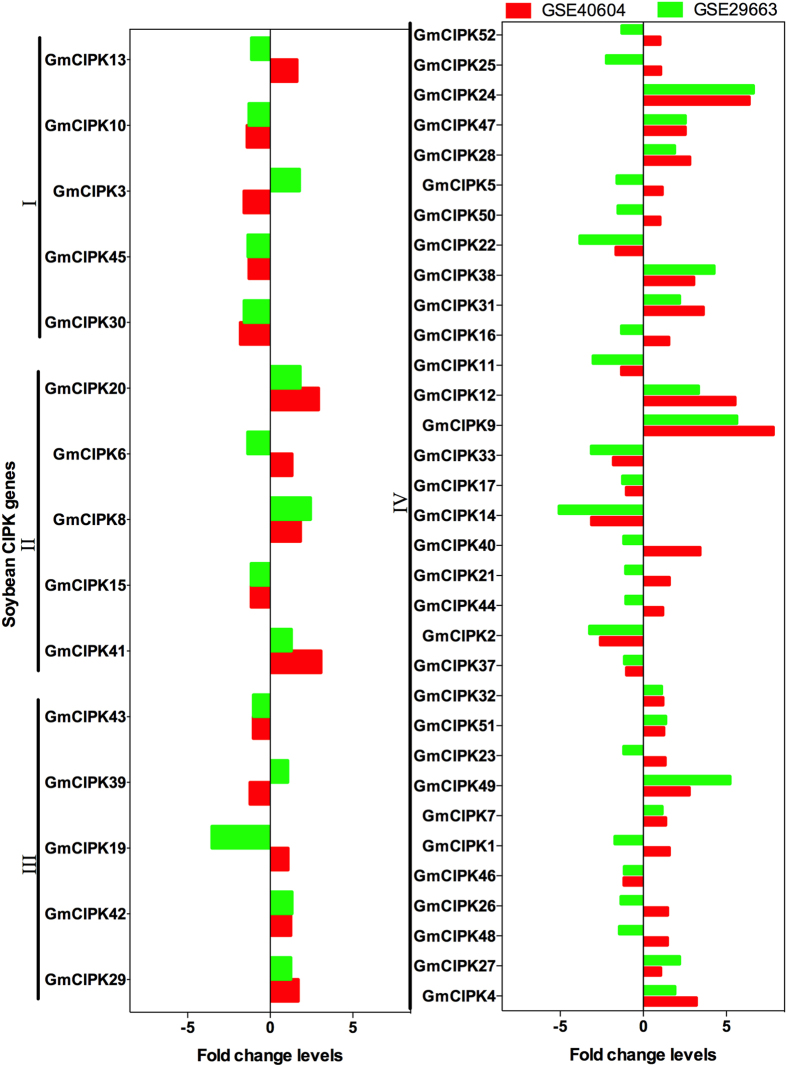

Global expression of soybean CIPK genes under drought

To investigate gene expression change of the soybean CIPK family members under drought, we analyzed gene expression profiles of individual CIPK genes using publicly available Affymetrix microarray datasets. GSE29663 and GSE40604 datasets provide gene expression profiling of soybean leaves at early and late developmental stages under drought stress, respectively9. Gene expression data were available only for 48 CIPK genes, which have probes in this microarray platform (Fig. 5). Twenty genes were found to be up-regulated and 28 were down-regulated in the leaves during the vegetative growth stage in response to drought. During the reproductive stage, 33 were found to be up-regulated and 15 down-regulated, in the leaves in response to drought stress. Eighteen genes were up-regulated in both developmental stages under drought, including 3 in subgroup II (GmCIPK8, 20 and −41), 2 in subgroup III (GmCIPK29 and −42), and 13 in subgroup IV (GmCIPK4, −7, −9, −12, −24, −27, −28, −31, −32, −38, −47, −49 and −51). In contrast, 13 genes showed constant down-regulation during both developmental stages. These genes included 3 in subgroup I (GmCIPK10, 30 and −45), 1 in subgroup II (GmCIPK15), 1 in subgroup III (GmCIPK43), and 8 in subgroup IV (GmCIPK2, −11, −14, −17, −22, −33, −37 and −46). The remaining 17 genes showed opposite expression patterns at both developmental stages (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Expression levels of soybean CIPK genes under drought stress using publicly Affymetrix microarray datasets.

Data are extracted from GSE29663 (green bars) and GSE40604 (red bars) datasets, which represent expression profiles in leaves under drought stress during early and late developmental stages, respectively.

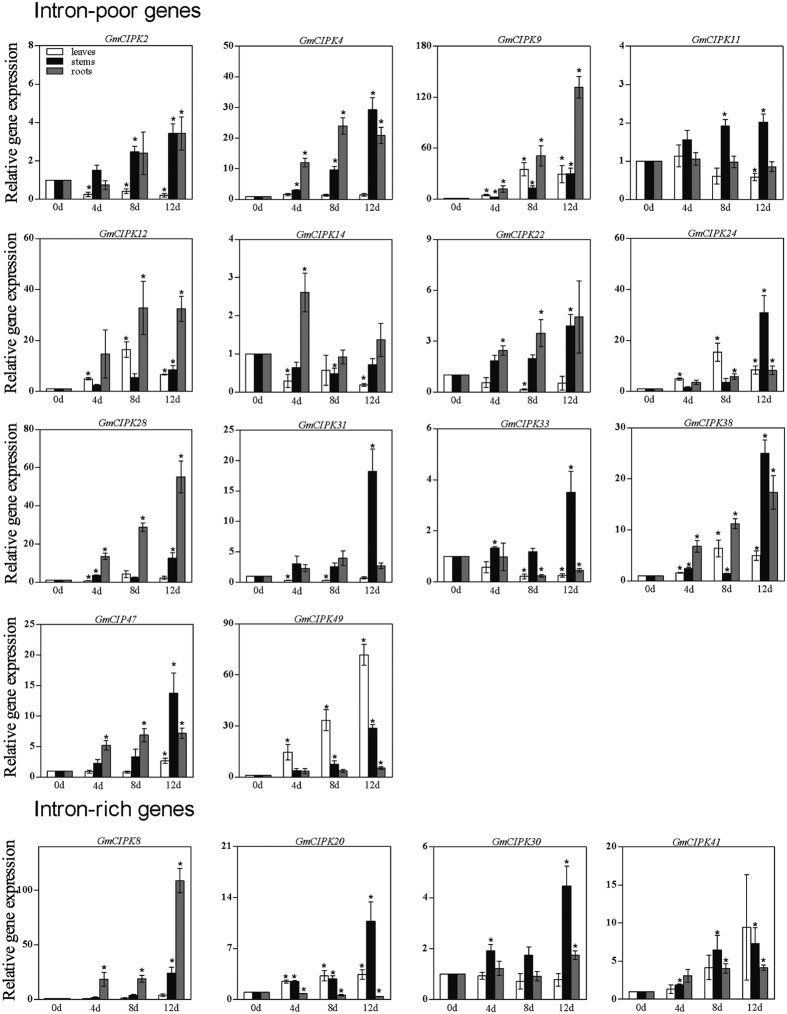

qRT-PCR quantification of CIPK gene expression levels in leaves, stems and roots under drought stress

Based on the microarray data (Fig. 5), we selected 18 candidate genes (GmCIPK2, −4, −8, −9, −11, −12, −14, −20, −22, −24, −28, −30, −31, −33, −38, −41, −47, and −49) for further confirmation using qRT-PCR in leaves, stems and roots at 4-, 8-, and 12-days after imposing drought stress (Figure S2). The qRT-PCR results showed that all these 18 selected CIPK genes are drought-responsive and expressed differently in three different tissues under drought treatment (Fig. 6). In leaf samples, GmCIPK2, −14, −31 and −33 genes were down-regulated in the entire period tested under drought stress. However, GmCIPK9, −12, −20, −24, −38, and −49 were up-regulated during all the three time points. Notably, GmCIPK49 was induced gradually and showed the highest gene expression (>60-fold) after 12 days of drought application. Seven genes, including GmCIPK9, −12, −20, −24, −38, −41, and −49, were highly up-regulated at 8-day and 12-day time points. In the stem samples, GmCIPK4, −8, −9, −24, −38, and −49 all showed higher gene expression levels (>20-fold) at 12-day than the untreated control. With the exception of GmCIPK14, which showed down-regulation, the remaining 17 genes exhibited up-regulation at the 3 time points tested. In root tissues, GmCIPK9 showed the highest gene expression level at 12-day point, or 120-fold of that in the control. Most of these 18 genes were up-regulated at 8-day and 12-day drought treatment except GmCIPK11, −14, −20 −30 and −33. While our qRT-PCR data are overall consistent with the microarray results (Fig. 5), a few genes displayed distinct expression patterns. This includes, for example, GmCIPK31, which was down-regulated in qRT-PCR assays of leave samples, but was up-regulated in the two microarray experiments.

Figure 6. Quantification of gene expression levels of 18 selected soybean CIPK genes under drought stress using qRT-PCR.

Fifteen-day-old plants were subjected to drought stress by withholding water for 0 (control), 4, 8 and 12 days. Leaf, stem and root samples were collected at these four time points for RNA extraction and qRT-PCR quantification of the expression levels of 14 intron-poor genes (top panels) and 4 intron-rich genes (bottom panels). Ribosomal protein s20e gene (Glyma.03G142300) was used as an internal control to normalize gene expression levels. The fold-change values represent changes of mRNA levels in drought stressed samples relative to non-stressed control samples. Data are average of three independent biological samples ± SE. Mean values significantly different from the control plants were determined by t tests (P < 0.05) and are indicated by an asterisk.

Discussion

Calcium plays a key role in plant signal transduction responding to environment stresses. Plant protein kinases such as calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs) play central role in mediating plant response to stress signaling39,40. The calcium sensor calcineurin B-like proteins (CBLs) and their target kinase CBL-interacting protein kinases (CIPKs) system function together to regulate plant environmental stresses, such as drought10. Arabidopsis CBL1- and CBL9-CIPK23 complexes control abscisic acid (ABA)-regulated drought tolerance41.

CIPK family had been analyzed in some model plants and major crops22,23,24,25,26, but no detailed information about soybean CIPK gene family is available. In this study, we identified 52 GmCIPK genes in soybean (Table 1), which is twice as much as that in Arabidopsis, and more than that in most of the other plant species with sequenced Genomes. The large size of the CIPK gene family in soybean could be attributed to the whole-genome duplication events occurred approximately 59 and 13 million years ago (Mya)1.

The soybean CIPK gene family has significantly expanded in its evolutionary history. Similar to Arabidopsis26 and maize23, the soybean CIPK proteins were divided into four subgroups based on the phylogenetic classification (Fig. 1A). The soybean CIPK genes are clearly divided into intron-rich (subgroups I, II and III) and intron-poor (subgroup IV) clades (Fig. 1). This finding suggests that similar intron gain and loss events contributed to the structural evolution of the CIPK gene family before the eudicot–monocot divergence. All of the 52 GmCIPK proteins contain the signature NAF domain (Fig. 2)13. Our analysis of chromosomal locations and duplication events implicates gene duplication, especially segmental duplication and tandem duplication as the major evolutionary mechanisms responsible for soybean CIPK expansions (Fig. 3). Interestingly, all genes contributed by tandem duplication events were intron-poor genes. However, segmental duplication events occurred both in intron-poor genes and intron-rich genes, an observation similar to what was previously reported in Arabidopsis26. Tandem duplications have been found to be associated with gene families that regulate plant responses to stresses42, but little information is available with regard to the relationship between intron-poor gene clade and plant adaptation to environmental stresses.

Our phylogenetic analysis suggests that CIPKs originated in green algae, but expanded along the evolutionary trajectory to angiosperms. It is interesting that the intron-poor CIPK group was evolved much later, first appeared in the seed plants, very likely derived from loss of introns in the intron-rich members, as the CIPKs in the more ancient lineages, such as in green algae14, moss, fern and spikemoss were all in the intron-rich group (Fig. 4). This may suggests that when seed plants evolved, there was a great force for environmental stress adaptation. It has been previously reported that the intron-poor clade of the Hsp90 gene family in Populus displayed differential expression patterns upon exposure to various abiotic stresses, particularly drought stress43.

Plant CIPK genes could be induced by different stresses, such as drought23,44, salt45, and cold18. Various functional studies of plant CIPK genes provided clear evidence for their implication in stress responses. For example, overexpression of SiCIPK24(SISOS2) in tomato enhanced salt tolerance46. In Similarly, overexpression of GhCIPK6 in Arabidopsis significantly increased the tolerance to drought, salt, and ABA20. Chaves-Sanjuan et al.47 described the CIPK protein structure and its regulatory mechanism during plant response to environmental stimuli. Consistent with a role of CIPK gene family in drought tolerance, a substantial number of soybean CIPKs changed mRNA abundance upon drought application as revealed by microarray analysis (Fig. 5). This was further verified in qRT-PCR assays (Fig. 6). The detailed gene expression analysis of soybean CIPK gene family in different tissues provided intriguing insight into their roles in responding to drought stress. Our qRT-PCR data showing differential expression patterns of 18 CIPK genes in three diverse tissues provide an indication of distinctive functional roles in of soybean CIPKs in different tissues in response to drought. In this context it may be important to mention that the unique and overlapping biological functions of CIPK gene family in different tissues are still unexplored24,48. Interestingly, we found the majority of drought-responsive CIPK genes in our qRT-PCR assays belong to the intron-poor gene clade in subgroup IV. This result suggests that expansion of intron-poor clade of CIPK genes may be an adaptive feature for drought stress26, but the mechanism underlying this adaptation remains elusive.

Among the up-regulated GmCIPK genes, we identified CIPK9, −12, −24, and −49 as the most highly expressed genes under drought stress in the three tissues tested. These genes represent bona find targets for improving soybean tolerance to drought and deserve further analysis to reveal their functional roles in drought response and the underlying molecular mechanisms, which is currently underway.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Zhu, K. et al. Evolution of an intron-poor cluster of the CIPK gene family and expression in response to drought stress in soybean. Sci. Rep. 6, 28225; doi: 10.1038/srep28225 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Tennessee soybean promotion Board project 15–82-R to Z. –M. C., and T. H. and by Tennessee Agricultural Experiment Station Hatch Project.

Footnotes

Author Contributions K.Z., F.C., J.L. and Z.-M.C. designed this research. K.Z. and X.C. did the experiments and collected the data. K.Z., F.C. and J.L. analyzed the data. K.Z. wrote the paper. T.H. and Z.-M.C. modified this manuscript.

References

- Schmutz J. et al. Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature 463, 178–183 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima K., Ito Y. & Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Transcriptional regulatory networks in response to abiotic stresses in Arabidopsis and grasses. Plant Physiol. 149, 88–95 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trenberth K. E. et al. Global warming and changes in drought. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 17–22 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Feng S. et al. Projected climate regime shift under future global warming from multi-model, multi-scenario CMIP5 simulations. Global Planet. Change 112, 41–52 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Roche J., Hewezi T., Bouniols A. & Gentzbittel L. Transcriptional profiles of primary metabolism and signal transduction-related genes in response to water stress in field-grown sunflower genotypes using a thematic cDNA microarray. Planta 226, 601–617 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche J., Hewezi T., Bouniols A. & Gentzbittel L. Real-time PCR monitoring of signal transduction related genes involved in water stress tolerance mechanism of sunflower. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 47, 139–145 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki K. & Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Gene networks involved in drought stress response and tolerance. J Exp. Bot. 58, 221–227 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadiarto T. & Tran L.-S. P. Progress studies of drought-responsive genes in rice. Plant Cell Rep. 30, 297–310 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le D. T. et al. Differential gene expression in soybean leaf tissues at late developmental stages under drought stress revealed by genome-wide transcriptome analysis. PLoS One 7, e49522 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan S. The CBL–CIPK network in plant calcium signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 14, 37–42 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L., Lan W., Chen B., Fang W. & Luan S. A Calcium Sensor-Regulated Protein Kinase, CALCINEURIN B-LIKE PROTEIN-INTERACTING PROTEIN KINASE19, is required for pollen tube growth and polarity. Plant Physiol. 167, 1351–1360 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J. et al. Novel protein kinases associated with calcineurin B–like calcium sensors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 11, 2393–2405 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht V., Ritz O., Linder S., Harter K. & Kudla J. The NAF domain defines a novel protein–protein interaction module conserved in Ca2+ regulated kinases. EMBO J. 20, 1051–1063 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleist T. J., Spencley A. L. & Luan S. Comparative phylogenomics of the CBL-CIPK calcium-decoding network in the moss Physcomitrella, Arabidopsis, and other green lineages. Front Plant Sci. 5, 187 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batistič O. & Kudla J. Plant calcineurin B-like proteins and their interacting protein kinases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1793, 985–992 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy A. S., Ali G. S., Celesnik H. & Day I. S. Coping with stresses: roles of calcium-and calcium/calmodulin-regulated gene expression. Plant Cell 23, 2010–2032 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J. et al. A protein kinase, interacting with two calcineurin B-like proteins, regulates K+ transporter AKT1 in Arabidopsis. Cell 125, 1347–1360 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Ding S., Zhang H., Du H. & An L. CIPK7 is involved in cold response by interacting with CBL1 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Sci. 181, 57–64 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W. et al. Calcineurin B-like interacting protein kinase OsCIPK23 functions in pollination and drought stress responses in rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Genet. Genomics 35, 531–532 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L. et al. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of a novel cotton CBL-interacting protein kinase gene (GhCIPK6) reveals its involvement in multiple abiotic stress tolerance in transgenic plants. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 435, 209–215 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolukisaoglu Ü., Weinl S., Blazevic D., Batistic O. & Kudla J. Calcium sensors and their interacting protein kinases: genomics of the Arabidopsis and rice CBL-CIPK signaling networks. Plant Physiol. 134, 43–58 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y., Xia X., Yin W. & Zhang H. Comparative genomic analysis of CIPK gene family in Arabidopsis and Populus. Plant Growth Regul. 52, 101–110 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. et al. Identification and characterization of putative CIPK genes in maize. J. Genet. Genomics 38, 77–87 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwar P. et al. Comprehensive structural, interaction and expression analysis of CBL and CIPK complement during abiotic stresses and development in rice. Cell calcium 56, 81–95 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. et al. Identification and characterization of CBL and CIPK gene families in canola (Brassica napus L.). BMC Plant Biol. 14, 8 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye C.-Y., Xia X. & Yin W. Evolutionary analysis of CBL-interacting protein kinase gene family in plants. Plant Growth Regul. 71, 49–56 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Finn R. D. et al. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D222–D230 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy S. R. Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics 14, 755–763 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I. et al. SMART 4.0: towards genomic data integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, D142–D144 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasteiger E. et al. ExPASy: the proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3784–3788 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A. & Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B. et al. GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 31, 1296–1297 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T. L., Johnson J., Grant C. E. & Noble W. S. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W39–W49 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L. et al. Expression profiling and integrative analysis of the CESA/CSL superfamily in rice. BMC Plant Biol. 10, 282 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant D., Nelson R. T., Cannon S. B. & Shoemaker R. C. SoyBase, the USDA-ARS soybean genetics and genomics database. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, D843–846 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed A. I. et al. TM4 microarray software suite. Methods Enzymol. 411, 134–193 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severin A. J. et al. RNA-Seq Atlas of Glycine max: a guide to the soybean transcriptome. BMC Plant Biol. 10, 160 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J. & Schmittgen T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−ΔΔCT) method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F. et al. The evolutionary history and diverse physiological roles of the grapevine calcium-dependent protein kinase gene family. PLoS One 8, e80818 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan J., Matschi S., Romeis T. & Zipfel C. The calcium-dependent protein kinase CPK28 negatively regulates the BIK1-mediated PAMP-induced calcium burst. Plant signal. behav. 10, e1018497 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong Y. H. et al. Two calcineurin B‐like calcium sensors, interacting with protein kinase CIPK23, regulate leaf transpiration and root potassium uptake in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 52, 223–239 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanada K., Zou C., Lehti-Shiu M. D., Shinozaki K. & Shiu S.-H. Importance of lineage-specific expansion of plant tandem duplicates in the adaptive response to environmental stimuli. Plant Physiol. 148, 993–1003 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. et al. Genome-wide analysis of the Populus Hsp90 gene family reveals differential expression patterns, localization, and heat stress responses. BMC Genomics 14, 532 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W. et al. Genome-wide gene phylogeny of CIPK family in cassava and expression analysis of partial drought-induced genes. Front Plant Sci. 6, 914 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D.-G. et al. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of MdSOS2 reveals its involvement in salt tolerance in apple callus and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 31, 713–722 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huertas R. et al. Overexpression of SlSOS2 (SlCIPK24) confers salt tolerance to transgenic tomato. Plant Cell Environ. 35, 1467–1482 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaves-Sanjuan A. et al. Structural basis of the regulatory mechanism of the plant CIPK family of protein kinases controlling ion homeostasis and abiotic stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, E4532–E4541 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T. et al. Identification and comprehensive analyses of the CBL and CIPK gene families in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 15, 269 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.