Abstract

The transcription factor BCL11B/CTIP2 is a major regulatory protein implicated in various aspects of development, function and survival of T cells. Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-mediated phosphorylation and SUMOylation modulate BCL11B transcriptional activity, switching it from a repressor in naive murine thymocytes to a transcriptional activator in activated thymocytes. Here, we show that BCL11B interacts via its conserved N-terminal MSRRKQ motif with endogenous MTA1 and MTA3 proteins to recruit various NuRD complexes. Furthermore, we demonstrate that protein kinase C (PKC)-mediated phosphorylation of BCL11B Ser2 does not significantly impact BCL11B SUMOylation but negatively regulates NuRD recruitment by dampening the interaction with MTA1 or MTA3 (MTA1/3) and RbAp46 proteins. We detected increased phosphorylation of BCL11B Ser2 upon in vivo activation of transformed and primary human CD4+ T cells. We show that following activation of CD4+ T cells, BCL11B still binds to IL-2 and Id2 promoters but activates their transcription by recruiting P300 instead of MTA1. Prolonged stimulation results in the direct transcriptional repression of BCL11B by KLF4. Our results unveil Ser2 phosphorylation as a new BCL11B posttranslational modification linking PKC signaling pathway to T-cell receptor (TCR) activation and define a simple model for the functional switch of BCL11B from a transcriptional repressor to an activator during TCR activation of human CD4+ T cells.

INTRODUCTION

Posttranslational modifications (PTMs) of transcription regulatory proteins allow the integration of various signaling and environmental cues into highly dynamic and controlled responses, thereby achieving coordinated gene expression programs essential for cell proliferation or differentiation.

The transcription factor BCL11B/CTIP2 was independently isolated as an interacting partner of chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor (COUP-TF) in neurons and as a tumor suppressor gene in mouse models of gamma ray-induced thymic lymphomas (1–3). Besides its expression in the central nervous system (CNS), BCL11B was shown to be widely expressed in all T-cell subsets, starting from the double-negative stage 2 (DN2 stage) and to be involved in various aspects of development, function, and survival of T cells (4). Indeed, BCL11B is a focal point essential for several checkpoints involved in T-cell commitment in early progenitors, selection at the DN2 stage, and differentiation of peripheral T cells (5–9). Furthermore, monoallelic BCL11B deletions or missense mutations have been identified in the major molecular subtypes of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (10). Therefore, these observations together with the occurrence of deletions and mutations in gamma ray-induced thymomas in mice identify BCL11B as a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor gene (11).

BCL11B is essential for T-cell development and is considered a “guardian of T cell fate” (12). Its closely related paralog BCL11A is essential for normal lymphopoiesis and hemoglobin switching during erythroid differentiation (13–15). Thus, these two transcription factors appear to be key regulators of fundamental differentiation programs during normal hematopoiesis.

BCL11B represses transcription of its target genes through interaction with several chromatin remodelling complexes and notably recruits NuRD complexes (nuclear remodeling and deacetylation complexes) via interaction with MTA1 and MTA2 (4, 11, 16–18). Although originally characterized as a sequence-specific transcriptional repressor, BCL11B also behaves as a context-dependent transcriptional activator of the IL-2 and Cot kinase genes in CD4+ T-cell activation (19, 20).

This dual behavior of BCL11B as a transcriptional repressor and activator is not fully understood but clearly relies on a dynamic cross talk between BCL11B PTMs. Indeed, mass spectrometry analyses of thymocytes isolated from 4- to 8-week-old mice and stimulated with a mixture of phorbol ester and calcium ionophore used as an in vitro model mimicking T-cell receptor (TCR) activation identified several mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) phosphorylation sites of BCL11B and confirmed its SUMOylation on lysine 679 (21). These phosphorylation events then initiate a rapid and complex cycle of BCL11B PTMs including deSUMOylation, rephosphorylation, and reSUMOylation, allowing recruitment of the transcriptional coactivator P300 to activate Id2 transcription (21, 22).

Here, we found that BCL11B interacts with the three MTA (metastasis-associated gene) family members through its conserved N-terminal MSRRKQ motif, which is embedded in a potential protein kinase C (PKC) phosphorylation consensus site. We demonstrated that an S2D phosphomimetic point mutation is sufficient to abolish the interaction of BCL11B with all MTA corepressors and hence with a wide range of NuRD complexes. Through generation of phosphospecific antibodies, we identified in vivo serine 2 phosphorylation of endogenous BCL11B proteins. We found that activation of transformed Jurkat or primary human CD4+ T cells results in a rapid and transient PKC-induced phosphorylation of this BCL11B Ser2 culminating at 30 min of treatment. In contrast with the MAPK-induced phosphorylations in late T-cell development, this PKC phosphorylation peak precedes and does not affect the SUMOylation peak during activation of CD4+ T cells. After prolonged activation (5 h), the decrease of BCL11B protein levels observed is due to the direct transcriptional repression of BCL11B by KLF4. As shown by coimmunoprecipitation of endogenous proteins and chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments, this BCL11B Ser2 phosphorylation through decreased interaction with MTA1 and concomitant increased interaction with P300 contributes to a strong transcriptional upregulation of Id2 and IL-2, two BCL11B direct target genes, during CD4+ T-cell activation. A PKC inhibitor, Gö6983 abolishes this corepressor/coactivator switch in Jurkat cells. Thus, our findings identify BCL11B Ser2 phosphorylation as a new mandatory step in the interconnected posttranslational modifications converting BCL11B from a transcriptional repressor to an activator and provide compelling evidence that together with SUMOylation this PKC-mediated phosphorylation is essential for transcriptional activation of IL-2 during human CD4+ T-cell activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

HEK293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), nonessential amino acids, and gentamicin. Jurkat and MOLT4 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FCS, nonessential amino acids, and penicillin-streptomycin.

Isolation and activation of human CD4+ T lymphocytes.

Donor blood samples were provided by Etablissement Français du Sang (EFS) (Nord de France), in agreement with the official ethics statement between EFS and the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS)–Délégation Nord Pas-de-Calais et Picardie. The study was approved by the Institut de Biologie de Lille (CNRS) and EFS Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was obtained in writing for each donor. Isolation of human CD4+ T cells was performed as previously described (23). Briefly, human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by Ficoll Hypaque density gradient centrifugation (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) and CD4+ T cells were obtained by negative selection using CD4+ T cell isolation kit II according to the manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotec). The purity was determined by flow cytometry, and was always ≥95%. CD4+ cells (106 cells/ml) were cultured in complete RPMI 1640 medium (RPMI 1640 medium [Gibco, Carlsbad, CA], 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum ]Gibco], 2 mM l-glutamine) and stimulated or not stimulated in 96-well flat-bottomed microculture plates coated with anti-CD3 antibodies (10 μg/ml; OKT3 clone) and soluble anti-CD28 antibodies (2 μg/ml; BD Biosciences) for 24 h or with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (50 ng/ml) and ionomycin (1 μg/ml) for 5 h. Cells were then recovered by centrifugation for further analyses.

Plasmids and chemicals.

The MTA1, MTA3, SENP2, and BCL11A expression vectors were kind gifts of R. Kumar, P. Wade, R. Hay, and P. Tucker, respectively. The various BCL11B-Gal4 expression constructs used in this study were generated as follows. Using the wild-type (WT) pcDNA3-FLAG-BCL11B plasmid (17, 24) as a template and using relevant oligonucleotides, we PCR amplified fragments corresponding to amino acids 1 to 20 and 1 to 58 of wild-type BCL11B as well as 1 to 20 fragments with point mutations of serine 2 (S2A, S2D, and S2T). Next, these fragments were cloned in frame with a C-terminal Gal4 DNA-binding domain followed by a nuclear localization signal (NLS) and a hemagglutinin (HA) epitope into the pSG5-Gal4-NLS-HA eukaryotic vector to mimic their location in the full-length protein (25). The point (S2A and S2D) and deletion (ΔMSRRKQ) mutants of BCL11B were PCR amplified from the WT BCL11B plasmid with relevant oligonucleotides and subcloned in pcDNA3-FLAG-BCL11B using standard procedures. All constructs were verified by sequencing. PMA and ionomycin (both from Sigma-Aldrich) were used at a final concentration of 50 ng/ml and 1 μg/ml, respectively. Bisindolylmaleimide II (BIMII) (used at a final concentration of 10 μM for 30 min) and Gö6983 (used at a final concentration of 1 μM for 15 min) which are general inhibitors of protein kinase C (PKC) subtypes were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and Selleckchem, respectively (26–28). The MEK inhibitor U0126 was purchased from Merck Millipore and used at a final concentration of 10 μM for 30 min. Okadaic acid (OA) and calyculin A (Cal. A), which are potent inhibitors of all three type 2A Ser/Thr phosphatases (PP1, PP2A, and PP6) (29), were both obtained from Santa Cruz. Okadaic acid and calyculin A were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and used at a final concentration of 1 μM and 50 nM, respectively. Calyculin A also inhibits arsenic-induced PML (promyelocytic leukemia protein) SUMOylation (30) and BCL11B SUMOylation (21, 31). The SUMOylation inhibitors 2-D08 [2′,3′,4′-trihydroxy-flavone, 2-(2,3,4-trihydroxyphenyl)-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one], which is specific and blocks SUMO (small ubiquitin-like modifier) transfer from the Ubc9-thioester complex to the substrates (32), and anacardic acid, which blocks SUMOylation without affecting ubiquitination (33), were both obtained from Sigma and used at a final concentration of 50 μM (34). Anacardic acid is also a potent inhibitor of several histone acetyltransferase (HATs) such as PCAF (P300/CBP-associated factor), P300, and TIP60 (35).

Transfection, immunoprecipitation, and coimmunoprecipitation.

Cells were transfected in Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) by the polyethylenimine (PEI) method using ExGen 500 (Euromedex), as previously described with 2.5 μg of DNA corresponding to the relevant expression vectors or the empty vector used as a control. Cells were transfected for 6 h and then incubated in fresh complete medium. After 48 h of transfection, cells were rinsed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in cold IPH buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40, protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche]) for coimmunoprecipitation. Cell lysates were sonicated briefly and cleared by centrifugation (14,000 rpm, 4°C, 15 min). The supernatants were precleared with 15 μl of protein A/G-Sepharose beads (Amersham Bioscience) incubating for 1 h on a rotator at 4°C. Then, lysates were incubated with 2 μg of antibody on a rotator at 4°C overnight. Later, 20-μl volumes of protein A/G beads were added and incubated for 30 min at 4°C. Finally, the beads were washed three times with IPH buffer. Bound proteins were eluted by boiling in Laemmli buffer (36).

To detect SUMOylation of endogenous BCL11B proteins by immunoprecipitation studies, Jurkat cells were lysed in a lysis buffer containing 1% SDS, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 10% glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 15 mM N-ethylmaleimide (NEM). These cell extracts were immediately boiled for 10 min and diluted in 9 volumes of radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 0.5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 10% glycerol) supplemented with 10 mM NEM and protease inhibitor cocktail for immunoprecipitation with anti-BCL11B antibodies (37).

To detect endogenous interactions between BCL11 (BCL11A or -B) and MTA (MTA1 or -3) proteins, we prepared the combined cytoplasmic and nucleoplasmic fractions and the micrococcal nuclease-solubilized chromatin fractions as previously described (36, 38, 39). Two chromatin fractions prepared in parallel from the same number of cells were analyzed in coimmunoprecipitation assays as described above, with control rabbit IgG or MTA1- and MTA3-specific antibodies.

Transfection and luciferase transactivation test.

HEK293T cells were plated in 12-well CellBind plates (Corning) and transfected with 500 ng of DNA for 6 h in triplicate with the luciferase reporter plasmid pGL3-5xGal4 RE-tk luc (luciferase expression under the control of Gal4-responsive elements) or the pGL3-empty vector in combination with various BCL11B-Gal4 constructs and then incubated in fresh complete medium. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were rinsed with ice-cold PBS and lysed in the luciferase assay buffer. After normalization to the β-galactosidase activity, the data were expressed as the luciferase activity relative to the activity of pGL3-Luc with pSG5-Gal4-NLS-HA, which represents the basal condition and was given an arbitrary value of 1. The results represent the mean values from three independent transfections in triplicate. Luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were measured using, respectively, beetle luciferin (Promega) and the Galacto-Light kit (Tropix) with a Berthold chemiluminometer (36).

Antibodies and Western blot analyses.

To generate polyclonal antibodies against phosphorylated serine 2 of BCL11B, control and phosphorylated peptides corresponding to amino acids 1 to 19 of human BCL11B [H2N-MS(PO3H2)RRKQGNPQHLC-CONH2] peptide were synthesized, coupled to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) and used to immunize rabbit (Eurogentec, Belgium). Control and phosphospecific antibodies were purified by affinity chromatography using standard protocols. The following commercial antibodies were used: anti-FLAG M2 from Sigma; anti-HA from BABCO; anti-BCL11B (ab18465 for Western blotting [WB], ab28448 for immunoprecipitation [IP] and chromatin immunoprecipitation [ChIP], and A300-383A for IP) from Abcam and Bethyl Laboratories; anti-phospho-Erk1/2 (9106) from Cell Signaling; antiactin (sc-1616R); anti-MTA1 (sc-9445 for WB, sc-10813 for IP, and sc-10813 or ab50263 for ChIP) from Santa Cruz and Abcam; anti-MTA3 (ab87275) from Abcam; anti-Erk2 (sc-154) from Santa Cruz; anti-HDAC2 (sc-7899 H-54) from Santa Cruz; anti-CHD4 (ab70469) from Abcam; anti-RbAP46 (sc-8272) from Santa Cruz; anti-RbAP48 (C15200206 for ChIP) from Diagenode; anti-phospho-PKC substrate (2261) from Cell Signaling; anti-KLF4 (ab106629) and anti-RanGAP1 (ab92360) from Abcam.

Western blotting was performed as previously described (40). The secondary antibodies were horseradish peroxidase-linked antibodies against rabbit, rat, goat, and mouse immunoglobulins (Amersham Biosciences) and goat immunoglobulins (Southern Biotech).

To analyze the SUMOylation of BCL11B proteins by Western blotting analyses, transfected HEK293T cells or Jurkat and human CD4+ T cells pelleted by centrifugation were directly lysed in Laemmli loading buffer, boiled for 10 min, and processed for Western blotting as described above.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation.

Control or activated Jurkat and primary human CD4+ T cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in 0.5 ml PBS for 5 × 106 cells. Then, cells were fixed by adding formaldehyde to a final concentration of 1% for 8 min at room temperature. To stop fixation, glycine was added to a final concentration of 0.125 M. After 5 min at room temperature, cells were collected by centrifugation (1,500 rpm at 4°C for 5 min). The supernatants were removed and cells were lysed by resuspension in chilled cell lysis buffer for 10 min on a rotator at 4°C. Then, the samples were pelleted, resuspended in 200 μl nucleus lysis buffer and sonicated to chromatin with an average size of 250 bp using a cooling BioRuptor (Diagenode, Belgium). Twenty micrograms of chromatin was immunoprecipitated with the antibodies indicated in the figures, and real-time PCR analyses were performed as described previously (36). The primers used are summarized in Table S1 in the supplemental material. For the IL-2 promoter, we designed primers around the BCL11B US1 (upstream site 1) binding sites (19). For the Id2 promoter, the transcription start site (TSS) is derived from the Id2 human locus found in the NCBI Nucleotide database (gi: 568815596). The region just upstream of the TSS contains several BCL11B binding sites as shown by chromatin immunoprecipitation-sequencing (ChIP-Seq) analyses of BCL11B binding in double-positive human thymocytes (9). Clustal alignments of the corresponding human and murine regions highlighted a conserved potential BCL11B direct binding site, TGGGC, which has been analyzed in ChIP-quantitative PCR (qPCR) experiments using relevant oligonucleotides. Similar analyses identified a potential KLF4 binding site in the BCL11B promoter. For the ChIP in the presence of the PKC inhibitors, Jurkat cells were first incubated with Gö6983 (1 μM for 15 min) before the relevant activation treatment.

Real-time and quantitative PCR.

Total RNAs were reverse transcribed using random primers and MultiScribe reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems). Real-time PCR (RT-PCR) analyses were performed by Power SYBR green (Applied Biosystems) in a MX3005P fluorescence temperature cycler (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Results were normalized to the values for 18S RNA used as a internal control. The primers used are summarized in Table S2 in the supplemental material.

Statistics.

Experiments were performed at least two or three times independently. Statistical analyses were performed by Student's t test.

RESULTS

BCL11B interacts with the three MTA proteins.

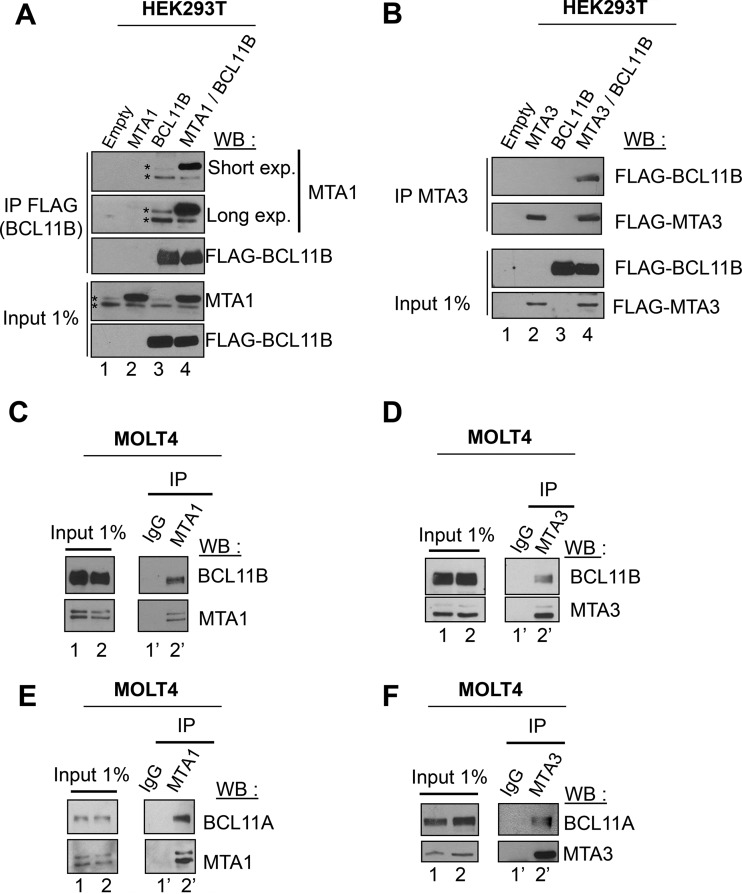

The three MTA proteins, MTA1, MTA2, and MTA3, are found in a mutually exclusive manner in different specialized NuRD complexes (41, 42). BCL11B interacts with the closely related MTA1 and MTA2 proteins (18). Therefore, we investigated whether BCL11B also interacts with the functionally distinct MTA3 protein. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments (Co-IPs) in transiently transfected HEK293T cells (Fig. 1A and B) or between endogenous proteins in the human acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell line MOLT4 (Fig. 1C and D) and in the human CD4+ T-cell line Jurkat (see Fig. S1A and B in the supplemental material) (19) demonstrated that BCL11B interacts with MTA1 and MTA3. Unlike Jurkat cells, MOLT4 cells express both BCL11B and BCL11A but with lower levels of MTA1 and MTA3 (see Fig. S1C to F) (43, 44). Similarly, we unraveled an interaction between BCL11A and MTA1 or MTA3 proteins either ectopically expressed in HEK293T cells (see Fig. S1G and H) or endogenously expressed in MOLT4 cells (Fig. 1E and F). Taken together, these results demonstrate that BCL11B and BCL11A can interact with the MTA1 or MTA2 (MTA1/MTA2) and MTA3 proteins and hence with a wide variety of NuRD complexes.

FIG 1.

BCL11A and BCL11B interact with MTA1 and MTA3. (A) MTA1 interacts with BCL11B. HEK293T cells were transfected with MTA1 and BCL11B expression vectors. Whole-cell extracts incubated with anti-FLAG antibodies (immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies [IP FLAG]) and 1% of each lysate (Input 1%) were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. FLAG-BCL11B coimmunoprecipitated endogenous MTA1 proteins (lane 3) visualized as a doublet (indicated by an asterisk). Short and long exposures (exp.) for Western blotting (WB) are indicated. (B) BCL11B interacts with MTA3. A similar experiment was conducted in HEK293T cells with BCL11B and MTA3 expression vectors. (C) Endogenous BCL11B and MTA1 proteins interact. Solubilized chromatin fractions were prepared in duplicate from the same number of MOLT4 cells, and 1% was retained for direct analyses by Western blotting (Input 1%). The interaction between BCL11B and MTA1 was evaluated by coimmunoprecipitation assays. (D to F) Endogenous BCL11B and MTA3 (D), BCL11A and MTA1 (E), and BCL11A and MTA3 (F) proteins interact in MOLT4 cells. The same procedure was used for panels C to E.

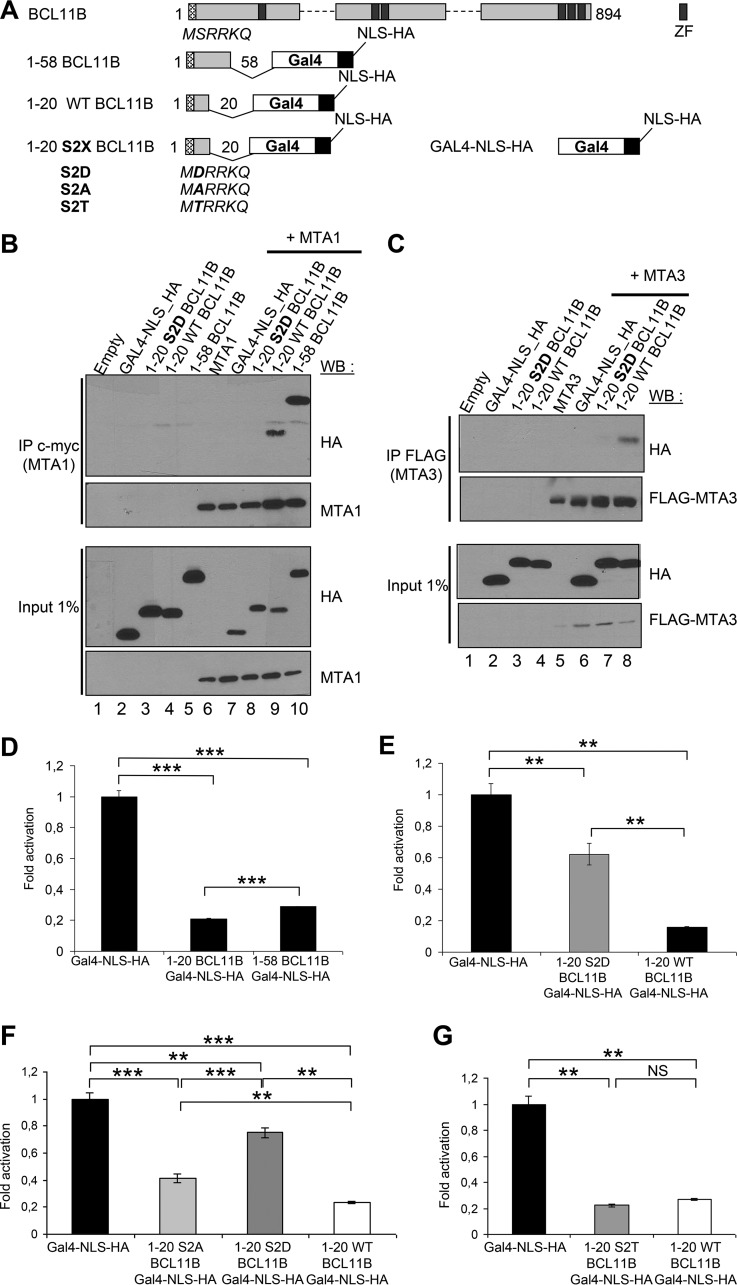

Mimicked phosphorylation of the BCL11B N-terminal domain (S2D) disrupts its interaction with MTA proteins and relieves its transcriptional repression activity.

Amino acids 1 to 45 of BCL11B containing the MSRRKQ motif shared with FOG1 and SALL1 are sufficient for the interaction with MTA1 in glutathione S-transferase (GST) pulldown experiments (18, 26, 45, 46). To assess this interaction in vivo, we fused amino acids 1 to 20 or amino acids 1 to 58 of BCL11B in frame with a C-terminal Gal4 DNA-binding domain (Fig. 2A). Transient-transfection assays in HEK293T cells demonstrated that these 1-20- and 1-58-BCL11B-Gal4 chimeras are nuclear, interact with MTA1 and MTA3 and mediate strong transcriptional repression in luciferase reporter assays (Fig. 2B to D) (see Fig. S2A to C in the supplemental material). Serine 2 (Ser2) of the conserved MSRRKQ motif is embedded in a potential consensus site (S/T-X2–0-R/K1–3) for phosphorylation by protein kinase C (PKC), a family of serine/threonine kinases involved in many cellular functions, including T-cell activation (47, 48). To study the importance of Ser2 and the effect of its potential phosphorylation, we constructed several point mutants of Ser2 (S2X) in the 1-20-BCL11B-Gal4 chimera (Fig. 2A). First, the phosphomimetic S2D mutant is unable to coimmunoprecipitate MTA1 or MTA3 protein, and in luciferase transactivation assays, its repression activity is significantly inhibited (Fig. 2B to F; see Fig. S2). In addition, the repression activity of the phosphodeficient S2A mutant is also inhibited (49), whereas a serine-to-threonine substitution (S2T) has no significant impact on the repression potential of the BCL11B-Gal4 chimera (Fig. 2F and G; see Fig. S2).

FIG 2.

Ser2 in the conserved N-terminal motif of BCL11B is essential for its interaction with MTA1 and MTA3 and for its transcriptional repression activity. (A) Schematic drawing of the BCL11B-Gal4 (DNA-binding domain)-NLS (nuclear localization signal)-HA fusion proteins. ZF, zinc finger. (B) A phosphomimetic point mutation S2D in the BCL11B N-terminal domain inhibits its interaction with MTA1. After transfection with the indicated expression vectors, HEK293T cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-c-myc antibodies (IP c-myc). Immunoprecipitated samples and 1% of whole-cell extracts (Input) were analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (C) The BCL11B-MTA3 interaction is also negatively regulated by the S2D mutation. A similar experiment was performed in HEK293T cells with a FLAG-MTA3 plasmid and the BCL11B-Gal4 chimeras. (D) The conserved BCL11B N-terminal domain represses transcription. The transcriptional activity of BCL11B-Gal4 constructs was tested by transient luciferase reporter assays in HEK293T cells. The results represent the mean values from three independent transfections in triplicate. (E) The S2D phosphomimetic mutation in the BCL11B N-terminal domain partially inhibits its transcriptional repression potential. A similar luciferase reporter assay was conducted in HEK293T cells with the wild-type (WT) 1-20 BCL11B and the S2D point mutant. (F and G) Repression potential of the various S2X point mutants BCL11B N-terminal domain. Luciferase reporter assays were conducted with the S2A, S2D, S2T, and WT BCL11B-Gal4 constructs as described above. Values that are statistically significantly different are indicated by bars and asterisks as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Values that are not statistically significantly different (NS) are also indicated.

Thus, the first 20 amino acids of BCL11B, including the conserved MSRRKQ motif, are sufficient to interact with MTA1 or MTA3 and have autonomous repression activity. Ser2 is important for these two properties, which are severely impaired by a phosphomimetic point mutation, S2D.

A phosphomimetic mutation of BCL11B Ser2, S2D, impedes NuRD recruitment.

We engineered an S2D and S2A full-length BCL11B point mutant and a deletion mutant, BCL11B ΔMSRRKQ (Fig. 3A). They all display a nuclear localization (see Fig. S2G in the supplemental material). In Co-IPs, the phosphomimetic S2D mutant weakly interacts with MTA1 and MTA3 overexpressed in HEK293T cells (Fig. 3B and C). Similarly, Co-IP assays demonstrated that the S2A and S2D point mutants ectopically expressed in HEK293T cells still weakly interact with endogenous MTA1 proteins, whereas the ΔMSRRKQ deletion mutant is unable to do so (Fig. 3D). The MSRRKQ motif of FOG1 also interacts with RbAp48 (49). We thus investigated the interaction of these mutants with other endogenous components of NuRD. We demonstrated that the S2A mutant still significantly interacts with MTA1, MTA3, and RbAp46 compared to wild-type (WT) BCL11B (Fig. 3E). In contrast, the S2D mutant is totally unable to interact with endogenous RbAp46, whereas it weakly interacts with MTA1, MTA3, CHD4, and HDAC2 (Fig. 3E and F). These results are in close agreement with the crystallographic structure of the FOG (friend of GATA) peptide consisting of amino acids 1 to 15 bound to RbAp48, since Ser2 is engaged in hydrogen bond interaction, whereas the adjacent Arg3, Arg4, and Lys5 participate in ion pair contacts with Glu residues in RbAp48 (49). Thus, an S2D phosphomimetic mutation in the N-terminal MSRRKQ motif of BCL11B negatively regulates the interactions with several endogenous NuRD components.

FIG 3.

The phosphomimetic S2D mutation in BCL11B inhibits NuRD recruitment. (A) Schematic drawing of the full-length BCL11B proteins tested. (B) The interaction with MTA1 is impaired by the S2D phosphomimetic mutation of BCL11B. HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated combination of expression vectors, and Co-IP assays followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies were performed. (C) The BCL11B-MTA3 interaction is also strongly reduced by the S2D phosphomimetic mutation. A similar Co-IP experiment was performed with HEK293T cells but with the FLAG-MTA3 expression vector. Relevant pieces of the membranes were cut (around the 80-kDa marker) to separate the MTA3 and BCL11B proteins and probed with anti-FLAG antibodies. (D) Interaction of wild-type (WT), S2A, S2D, and ΔMSRKKQ BCL11B with endogenous MTA1 proteins. Total extracts of HEK293T cells transfected with the indicated plasmids were analyzed by Co-IP with anti-FLAG antibodies and immunoblotted with MTA1 and FLAG antibodies. (E and F) Interaction of the S2A and S2D BCL11B point mutants with endogenous NuRD components. Co-IP experiments followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies were performed as in panel D with the S2A and S2D (E) or S2D (F) BCL11B mutants.

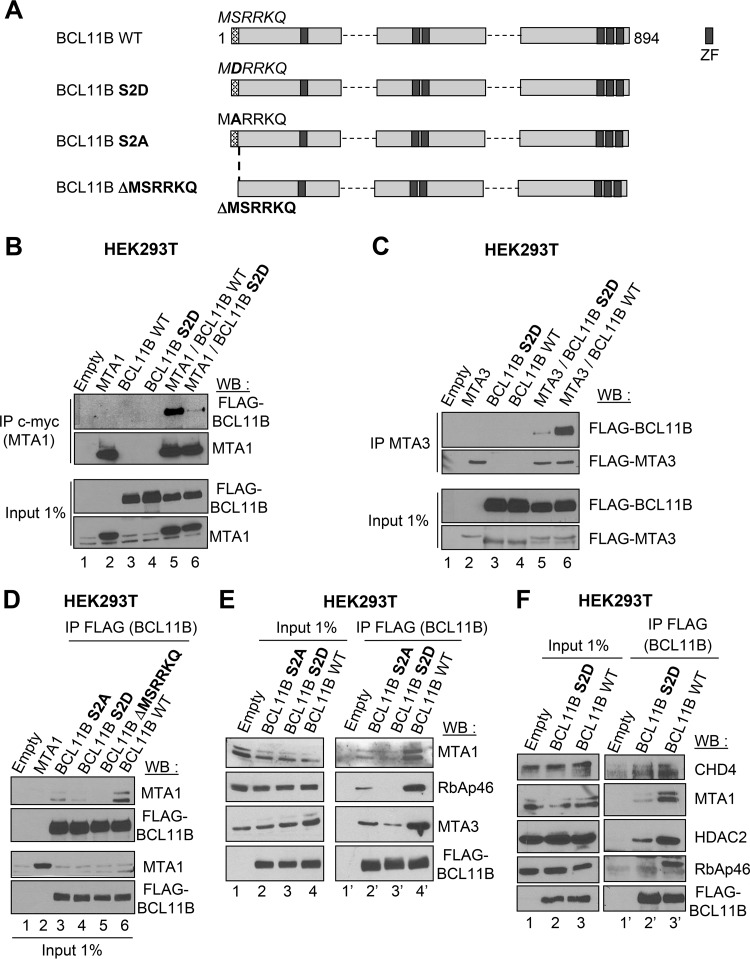

BCL11B is phosphorylated by PKC on Ser2 upon PMA activation of HEK293T cells and is SUMOylated.

Next, we raised antibodies against phospho-Ser2 BCL11B that were able to detect phosphorylation of BCL11B on the Ser2 residue in transfected HEK293T cells treated with PMA, a potent PKC activator (48) (Fig. 4A) (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). These antibodies detected strong induction of Ser2 phosphorylation after overexpression of WT BCL11B but not of the S2A mutant in PMA-treated HEK293T cells, thereby demonstrating their specificity (Fig. 4B). Finally, addition of BIMII, a PKC inhibitor decreased BCL11B phosphorylation on Ser2, whereas okadaic acid, a Ser/Thr phosphatase inhibitor, increased it (Fig. 4C and D).

FIG 4.

Phosphorylation of BCL11B Ser2 in HEK293T cells upon PKC activation. (A) PMA-induced in vitro phosphorylation of BCL11B Ser2. HEK293T cells transfected with FLAG-BCL11B were mock treated (−) or incubated with vehicle (DMSO) or with PMA (1 μM) for 20 min. Immunoprecipitated samples (IP FLAG) and input lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for phosphorylated Ser2 (pSer2 BCL11B) and FLAG as a control. (B) Specificity of the anti-pSer2 BCL11B antibodies. A similar experiment was performed to compare the BCL11B S2A mutant and WT BCL11B in the three conditions. The position of a nonspecific band is indicated by an asterisk. (C) PKC is implicated in BCL11B Ser2 phosphorylation. HEK293T cells were transfected with BCL11B and activated exactly as in panel A. One plate was preincubated with the pan-PKC inhibitor BIMII before PMA activation. The PKC inhibitor also partially inhibits Erk activation as previously shown (50). (D) The phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid (OA) allows detection of BCL11B Ser2 phosphorylation in basal conditions. HEK293T cells transfected with the indicated expression vectors were incubated with DMSO (+) or treated with OA (+). Total cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies.

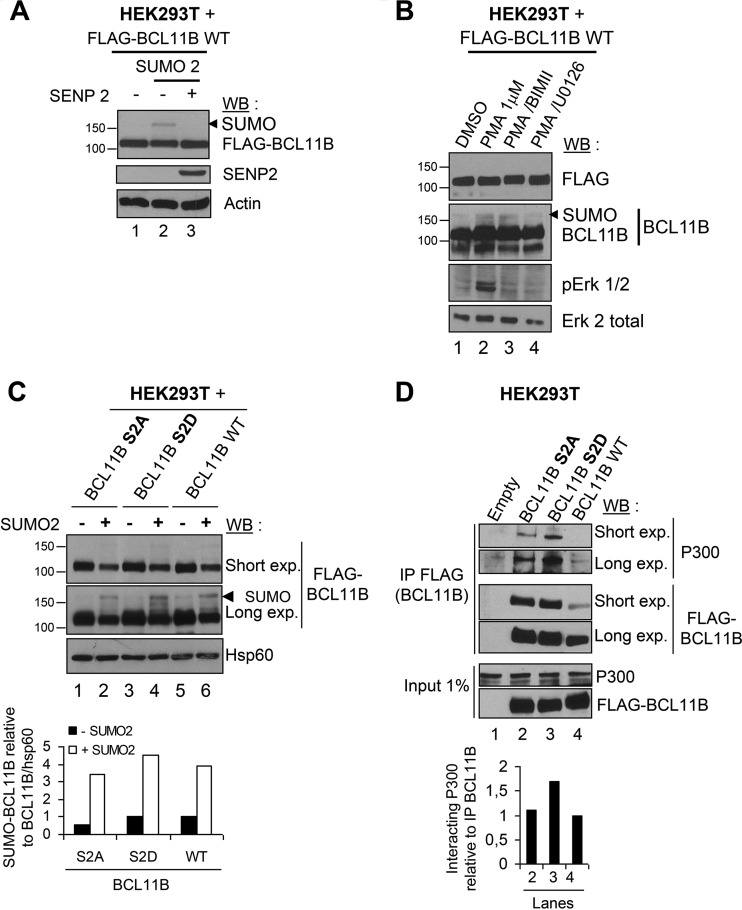

In phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate and A23187 (P/A)-stimulated murine thymocytes, BCL11B is SUMOylated (21). In PMA-activated HEK293T cells transfected with BCL11B, we also observed a slowly migrating band (above the 150-kDa marker) which corresponds to the SUMOylation of BCL11B, since it totally disappeared upon cotransfection of the deSUMOylase SENP2 (Fig. 5A) (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). In addition, the PKC inhibitor BIMII seems to have no significant effect on the SUMOylation level of BCL11B, while the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) inhibitor U0126 seemed to slightly reduce it (Fig. 5B). The PKC inhibitor also partially inhibits Erk activation as previously shown (50). BCL11B SUMOylation is important for its interaction with p300 (21). Interestingly, whereas the S2A and S2D point mutants are severely affected in their interaction with MTA1 compared with WT BCL11B (Fig. 3), they display similar levels of SUMOylation and hence of interaction with endogenous p300 proteins (Fig. 5C and D), correlating the lack of significant effects of the PKC inhibitor on BCL11B SUMOylation.

FIG 5.

BCL11B SUMOylation in HEK293T cells is independent of Ser2 phosphorylation. (A) BCL11B is SUMOylated. Total cell extracts of HEK293T cells transfected with the indicated combinations of BCL11B, SUMO2, and the deSUMOylase SENP2 were prepared in denaturing conditions and immunoblotted with indicated antibodies. The position of the SUMOylated form of BCL11B is indicated by the arrowhead. The positions of molecular markers are indicated to the left of the blot. (B) The PKC pathway does not affect BCL11B SUMOylation in contrast with the ERK pathway. HEK293T cells were transfected with BCL11B and preincubated with the PKC inhibitor BIMII or with the Erk1/2 inhibitor U0126 before PMA activation. The PKC inhibitor also partially inhibits Erk activation as previously shown (50). Total cell extracts prepared in denaturing conditions were immunoblotted as indicated. (C) The S2D and S2A point mutations have no significant impact on BCL11B SUMOylation. HEK293T cells were transfected as indicated, lysed in denaturing conditions, and immunoblotted with anti-FLAG antibodies to detect BCL11B and its SUMOylated forms. Hsp60 was used to quantify the ratio of SUMOylated BCL11B to total BCL11B using Fujifilm MultiGauge software. The value obtained for BCL11B WT in the absence of SUMO2 (lane 5) was set at 1. (D) The S2D and S2A point mutations do not affect BCL11B interaction with endogenous P300 proteins. HEK293T cells transfected with the indicated plasmids were subjected to Co-IP analyses with anti-FLAG antibodies followed by immunoblotting with P300 or FLAG antibodies. The ratio of interacting P300 relative to BCL11B was measured as described above for panel C.

Thus, the PKC-mediated phosphorylation of BCL11B in HEK293T cells impinges on its interaction with MTA1 but not on its SUMOylation and interaction with P300.

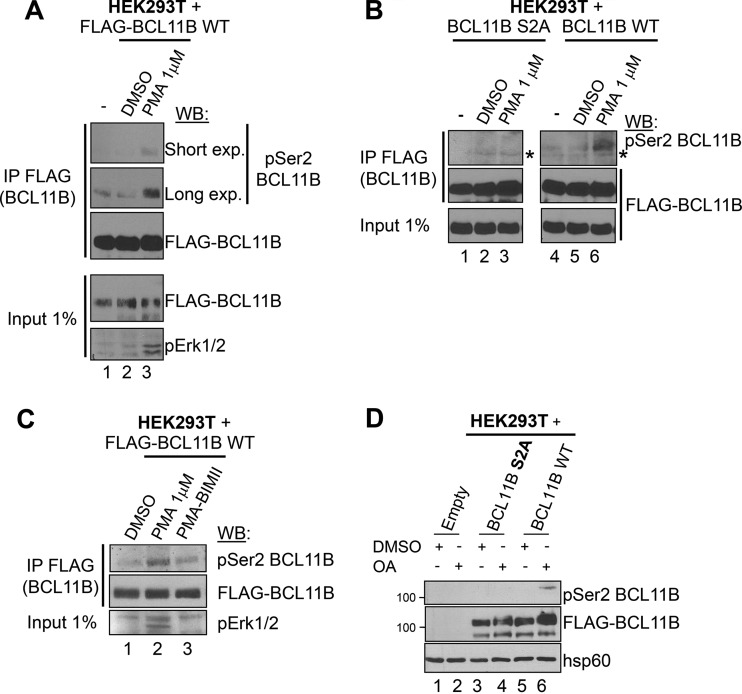

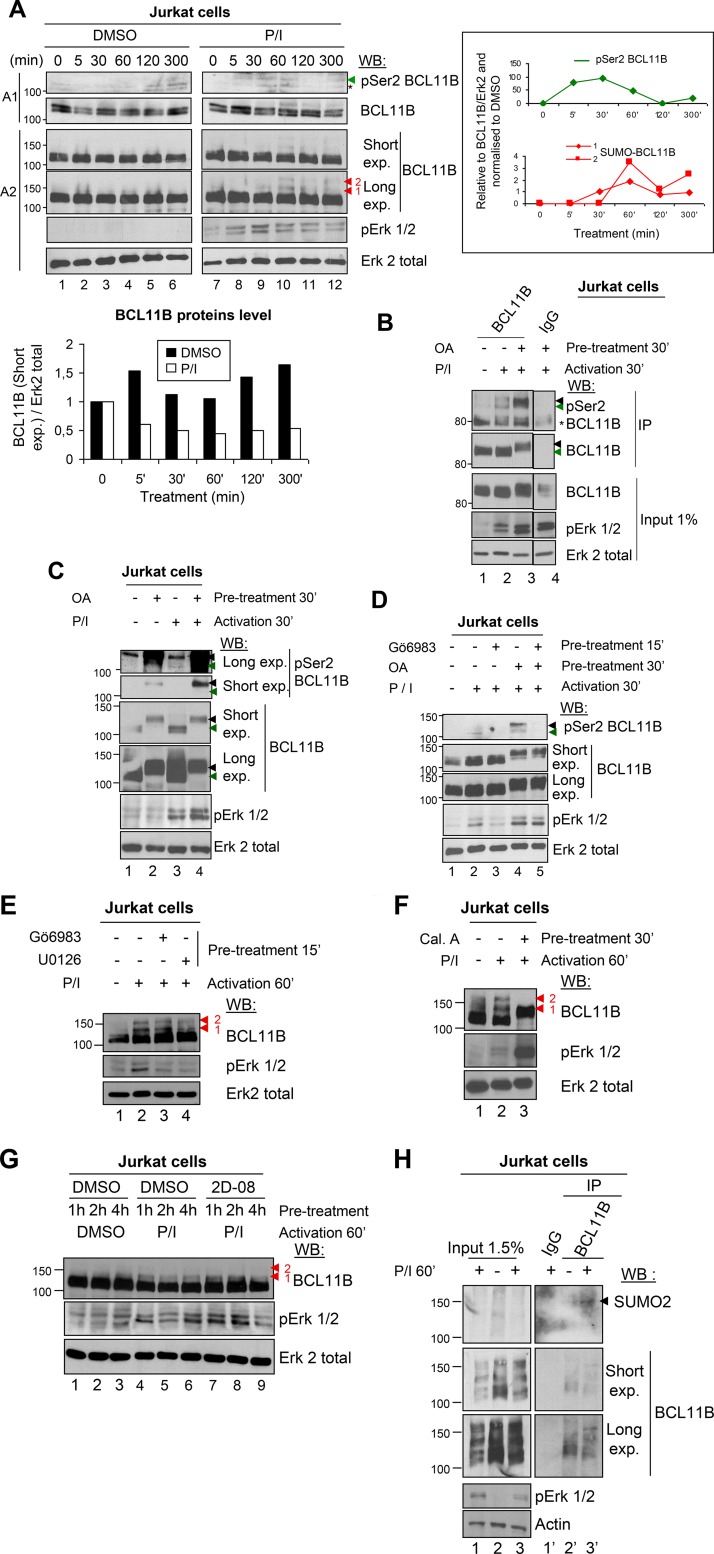

PKC-mediated Ser2 phosphorylation of endogenous BCL11B proteins upon PMA-ionomycin activation of Jurkat cells has no impact on its SUMOylation.

We next addressed this PKC-mediated Ser2 phosphorylation on endogenous BCL11B proteins during human CD4+ T-cell activation. Western blot analyses of Jurkat cell extracts with the anti-pSer2 BCL11B serum confirmed a peak of transient phosphorylation of BCL11B Ser2 after 30 min of activation with PMA-ionomycin (P/I) (Fig. 6A). Immunoprecipitation of Jurkat cell extracts by a C-terminal BCL11B antibody followed by Western blotting analyses with the anti-pSer2 BCL11B serum identified BCL11B proteins phosphorylated on serine 2 upon T-cell activation, notably in the presence of the phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid (Fig. 6B). Treatment with okadaic acid induced a supershift of BCL11B both in basal and activated conditions due to its phosphorylation by ERK and PKC pathways as detected by the anti-pSer2 antibodies (Fig. 6B, lane 3, and Fig. 6C, lanes 2 and 4). Furthermore, Ser2 phosphorylation observed in the presence of okadaic acid is lost if, before activation, cells are treated with the PKC inhibitor Gö6983, whereas the supershift of BCL11B is still observed (Fig. 6D, lanes 4 and 5).

FIG 6.

Endogenous BCL11B proteins are phosphorylated on Ser2 and SUMOylated in PMA-ionomycin-activated Jurkat cells. (A) Activation of Jurkat cells with PMA-ionomycin (P/I) induces Ser2 phosphorylation of endogenous BCL11B proteins. Jurkat cells were treated with P/I in a time-dependent manner, and cell extracts prepared in denaturing conditions were analyzed by immunoblotting of two different SDS-polyacrylamide gels. In gel A1, the position of pSer2 BCL11B is indicated by a green arrowhead and the position of a nonspecific band is indicated by an asterisk. In gel A2, the positions of slowly migrating BCL11B-SUMOylated species are indicated by red arrowheads. Quantification of total BCL11B proteins in DMSO versus P/I conditions (bottom graph) and of Ser2-phosphorylated and SUMO-BCL11B to BCL11B (right graphs) were performed with Fujifilm MultiGauge software. (B) Detection of pSer2 BCL11B in activated Jurkat cells by IP/WB. Jurkat cells were treated with DMSO or activated for 30 min (30′) and pretreated with the phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid (OA) (+) or not pretreated with OA (−). Total cell extracts were immunoprecipitated by BCL11B and immunoblotted with the pSer2 BCL11B-specific antibodies. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with anti-BCL11B antibodies. The green arrowheads indicate the position of pSer2-BCL11B, and the black arrowheads indicate the supershift of phosphorylated BCL11B observed with OA. (C) The phosphatase inhibitor OA favors detection of pSer2 BCL11B and induces a supershift of BCL11B upon P/I activation of Jurkat cells. Cells were treated with DMSO (−) or activated with P/I for 30 min and pretreated or not with OA. Total cell extracts were prepared and immunoblotted as indicated. The green arrowheads indicate the position of BCL11B, and the black arrowheads indicate the supershift of phosphorylated BCL11B observed with OA. (D) The PKC inhibitor Gö6983 abolishes Ser2 phosphorylation but not the supershift of BCL11B upon P/I activation. An experiment was conducted essentially as described above for panel C but with pretreatment with Gö6983. (E) SUMOylation of endogenous BCL11B proteins is not affected by PKC inhibition. Jurkat cells were treated with DMSO or activated for 60 min to favor SUMOylation and treated with Gö6983 and U0126 or not treated with Gö6983 and U0126. Total cell extracts prepared in denaturing conditions were immunoblotted as indicated. (F) The SUMOylation inhibitor calyculin A inhibits BCL11B SUMOylation. Jurkat cells were treated with DMSO or activated for 60 min and pretreated with the SUMOylation inhibitor calyculin A (Cal A) or not treated with calyculin A. Calyculin A is also a phosphatase inhibitor and thus induces a supershift for BCL11B. The positions of SUMOylated forms of BCL11B are indicated by arrowheads. (G) The specific SUMOylation inhibitor 2-D08 slightly inhibits BCL11B SUMOylation. A similar experiment was performed with Jurkat cells pretreated with 2-D08 or not pretreated with 2-D08 for the indicated times. (H) Detection of endogenous BCL11B SUMOylation in Jurkat cells by immunoprecipitation analyses. Jurkat cells were treated with DMSO or P/I for 1 h to favor SUMOylation. To detect SUMOylated proteins, the cells were lysed in 1 volume of 1% SDS. The lysates were immediately boiled for 10 min, then diluted with 9 volumes of RIPA buffer without SDS, and immunoprecipitated with anti-BCL11B antibodies. The immunoprecipitates were then analyzed by Western blotting with anti-SUMO2 (top gels). The position of SUMOylated BCL11B proteins is indicated by an arrowhead. The membranes were stripped and reprobed with anti-BCL11B antibodies. Please note that in contrast with the other gels in this figure, this gel is a 6% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, which might explain the “ladder-like” aspect of the BCL11B bands.

In activated Jurkat cells, BCL11B phosphorylation is transient and precedes its SUMOylation (Fig. 6A). As observed in HEK293T cells, the PKC inhibitor seems to have no significant effects on BCL11B SUMOylation after 60 min of activation, whereas ERK inhibition by U0126 seems to slightly decrease it (Fig. 6E). Another Ser/Thr phosphatase inhibitor, calyculin A, is also a SUMOylation inhibitor as initially shown for PML (30) and later for BCL11B (21, 31). Upon activation and calyculin A treatment of Jurkat cells, we observed an electromobility shift for the major BCL11B proteins, whereas the slowest migrating BCL11B-SUMO band totally disappeared (Fig. 6F), as shown in murine thymocytes (21). Similar results were obtained with the specific SUMOylation inhibitor 2-D08 (32, 34) (Fig. 6G) and with anacardic acid (AA), an inhibitor of SUMOylation (33) and of various histone acetyltransferase (HATs) (35). This might explain through transcriptional inhibition, the decrease of BCL11B protein levels as well as of several SUMOylated proteins observed with AA (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Finally, Western blot analyses with anti-SUMO-2 after immunoprecipitation of endogenous BCL11B proteins under denaturing conditions allowed the detection of SUMOylated BCL11B proteins in activated Jurkat cells (Fig. 6H) (37). As a whole, these data identify phosphorylation of BCL11B Ser2 by PKC as a new posttranslational modification of BCL11B during human CD4+ T-cell activation, preceding and acting independently of its SUMOylation.

KLF4 directly represses BCL11B transcription upon PMA-ionomycin activation of Jurkat cells.

SUMOylation of BCL11B in P/A-treated murine thymocytes ultimately results in its ubiquitination and degradation (21). However, whereas prolonged stimulation of Jurkat cells with P/I also resulted in a decrease of BCL11B protein levels after 5 h (Fig. 6A), this correlated with transcriptional repression of BCL11B, rather than degradation after ubiquitination (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). Indeed, real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analyses demonstrated a strong decrease of BCL11B mRNAs starting at 2 h of stimulation (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, BCL11B proteins levels decreased after 5 h of P/I stimulation, even in the presence of three different proteasome inhibitors, MG132, acetyl-Leu-Leu-Nle-aldehyde (ALLN), or lactacystin (Fig. 7B). Inducible overexpression of the transcriptional repressor KLF4 in Jurkat cells inhibits the expression of T-cell-associated factors including BCL11B and induces its degradation after 48 h (31). These results prompted us to further investigate the relationship between KLF4 and BCL11B. In Jurkat cells, RT-qPCR analyses detected a strong induction of KLF4 expression peaking 30 to 60 min after activation (Fig. 7C) and thus preceding the repression of BCL11B expression (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, in silico analyses of the BCL11B promoter identified a conserved KLF4 binding site upstream of the TSS (Fig. 7D). ChIP analyses demonstrated the direct binding of KLF4 on the BCL11B promoter and on CXCR4, a bona fide KLF4 direct target gene (31) (Fig. 7E) after 5 h of activation when BCL11B and CXCR4 expression are severely repressed (Fig. 7A) (see Fig. S6A and B in the supplemental material).

FIG 7.

Activation of Jurkat cells induces BCL11B downregulation by direct transcriptional repression mediated by KLF4. (A) Prolonged activation of Jurkat cells induces downregulation of BCL11B expression. Jurkat cells were treated with DMSO or activated with P/I for the indicated times. BCL11B mRNAs levels were determined by real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analyses. (B) BCL11B proteins are not targeted for degradation by ubiquitination. Jurkat cells were pretreated with different proteasome inhibitors for 1 h before activation and activated for 5 h as indicated. Total cell extracts were immunoblotted with anti-BCL11B antibodies. (C) KLF4 expression is induced in activated Jurkat cells. KLF4 mRNA levels were analyzed by RT-qPCR in the samples used in panel A for BCL11B. (D) Schematic drawing of the human BCL11B proximal promoter region. The transcription start site (TSS), the conserved potential KLF4 binding site (underlined), and the oligonucleotides used in ChIP-qPCR experiments are shown. Mu, murine; Hu, human. (E) KLF4 binds the BCL11B promoter. Chromatin was prepared from DMSO-treated and P/I-activated Jurkat cells, and ChIP analyses were performed for KLF4 or IgG at KLF4 binding sites in BCL11B and CXCR4 promoters. GAPDH was used as a nonbinding control. Values that are statistically significantly different are indicated by bars and asterisks as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Values that are not statistically significantly different (NS) are also indicated.

Thus, BCL11B is a new direct target gene of the transcriptional repressor KLF4 during human CD4+ T-cell activation.

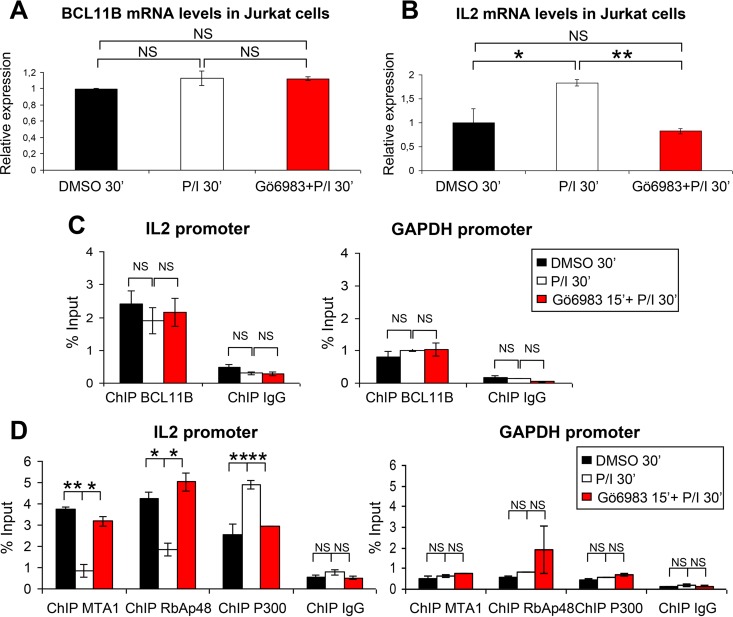

Endogenous BCL11B binds the IL-2 and Id2 promoters but with the MTA1 corepressor or the P300 coactivator in resting versus PMA-ionomycin-activated Jurkat T cells.

BCL11B participates through interaction with the P300 coactivator in the transcriptional activation of IL-2 and of Id2 (19, 21). Activation of Jurkat cells with P/I induced a huge upregulation of IL-2 gene expression starting as early as 30 min of treatment and a significant, albeit slightly delayed upregulation of Id2 around 120 min (Fig. 8A and B; see Fig. S6C in the supplemental material), whereas BCL11B mRNA levels decreased after 2 h of treatment (Fig. 7A). Coimmunoprecipitation of BCL11B with MTA1 or P300 endogenous proteins in Jurkat cells treated for 30 min with P/I demonstrated that the peak of BCL11B Ser2 phosphorylation we reproducibly observed (Fig. 6A) is concomitant with a slight decrease of BCL11B-MTA1 interaction and a clear increase of BCL11B-P300 interaction (Fig. 8C).

FIG 8.

BCL11B-mediated repression of IL-2 expression through MTA1 or MTA3 recruitment in unstimulated cells is lost during Jurkat cell activation by P/I treatment. (A and B) Activation of human Jurkat CD4+ T cells by P/I induced an increase of IL-2 and Id2 expression. Jurkat cells were treated with DMSO or activated with P/I for the indicated times. Total RNAs were extracted and RT-qPCR experiments were performed to analyze the increase of IL-2 (A) and Id2 (B) expression levels after activation of Jurkat cells. Due to the huge induction of IL-2 expression after prolonged stimulation, the IL-2 expression levels measured after 2 and 5 h of treatment are shown with a different scale as Fig. S6C in the supplemental material. (C) Endogenous P300 preferentially interacts with BCL11B in activated Jurkat T cells. Cells were activated with P/I (+) or not activated with P/I (−), lysed in IPH buffer, and immunoprecipitated with anti-BCL11B. As a control, P/I-treated cells were immunoprecipitated with rabbit IgG. The immunoprecipitates were then analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. (D) Schematic drawing of the human Id2 proximal promoter region with the transcription start site (TSS) and the conserved potential BCL11B direct binding site, TGGGC. The positions of the oligonucleotides used in ChIP-qPCR experiments are shown as arrows. (E to I) ChIP experiments were performed on chromatin from Jurkat cells treated with DMSO (D) or activated with P/I with antibodies against BCL11B, MTA1, MTA3, and rabbit IgG (E to H) or against P300 and mouse IgG (I). The bound material was eluted and analyzed by quantitative PCR using primers flanking the US1 BCL11B binding site in IL-2 (19) and the newly identified BCL11B binding in Id2. For each promoter and antibody, GAPDH was used as an internal nonbinding control. Values that are statistically significantly different are indicated by bars and asterisks as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Values that are not statistically significantly different (NS) are also indicated.

To correlate these results with promoter occupancy, we first performed pilot ChIP experiments with chromatin prepared from Jurkat cells and showed that BCL11B and MTA1 are bound on upstream site 1 (US1) of the IL-2 promoter (19) and on the Id2 promoter on a newly identified and conserved BCL11B binding site located just upstream of the transcription start site (Fig. 8D; also see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material). ChIP experiments conducted with Jurkat cells treated with DMSO or with P/I for 30 min failed to detect any significant differences in BCL11B binding to the IL-2 and Id2 promoters (Fig. 8E and F). In contrast, in Jurkat cells activated for 30 min to induce the peak of BCL11B Ser2 phosphorylation (Fig. 6), IL-2 and Id2 promoter occupancy by MTA1 and MTA3 was markedly decreased compared to the steady-state levels (Fig. 8E to H). This effect was not due to a downregulation of MTA1 expression, since the levels of MTA1 RNAs (see Fig. S6) are slightly increased by the treatment. Conversely and in agreement with the Co-IP experiments, recruitment of the P300 coactivator at the IL-2 and Id2 promoters is significantly increased in activated Jurkat cells (Fig. 8I). As a control, none of these proteins were detected on the GAPDH promoter (Fig. 8G to I).

Ectopic expression of S2D and S2A BCL11B mutants in Jurkat cells to directly address the impact of Ser2 phosphorylation on this MTA1/P300 switch is not feasible. Indeed, the prior inactivation of the highly expressed endogenous BCL11B proteins will rapidly inhibit the proliferation of Jurkat cells and induce apoptosis (51, 64). To obtain further evidence of the specific involvement of PKC in regulating BCL11B interactions with MTA1 and P300, Jurkat cells were activated in the presence of a pan-PKC inhibitor, Gö6983. Pretreatment of Jurkat cells with Gö6983 has no effect on BCL11B or MTA1 and RbAp48 expression levels but blocked the P/I-induced activation of IL-2 expression (Fig. 9A and B) (see Fig. S6G and H in the supplemental material). Furthermore, in the presence of the PKC inhibitor, similar levels of BCL11B are bound to the IL-2 promoter, but MTA1 and RbAp48 are not released from the promoter (Fig. 9C and D). Conversely, Gö6983 inhibits the P/I-induced increase of P300 binding on the IL-2 US1 site (Fig. 9D).

FIG 9.

The PKC inhibitor Gö6983 abolishes the corepressor-coactivator switch of BCL11B on the IL-2 promoter. (A and B) Jurkat cells were treated with DMSO or activated with P/I for 30 min without or with preincubation with the PKC inhibitor Gö6983. RT-qPCR experiments were performed to analyze the expression levels of BCL11B and IL-2. (C and D) Relative occupancy of BCL11B, MTA1, RbAp48, and P300 on IL-2 promoter during Jurkat cell activation with or without treatment with the PKC inhibitor Gö6983. The level of binding was assessed by ChIP-qPCR experiments in triplicate before and after activation and inhibitor treatment as described for panels A and B. Error bars indicate standard deviations. The ChIP results for the US1 site in the IL-2 promoter are shown on the left, whereas those for the GAPDH promoter used as a nonbinding control are shown on the right. Values that are statistically significantly different are indicated by bars and asterisks as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Values that are not statistically significantly different (NS) are also indicated.

Together, these data show that P/I treatment does not affect direct BCL11B binding to IL-2 and Id2 promoters but induces its phosphorylation on Ser2 by PKC to disrupt interaction with NuRD repressive complexes and to mediate interaction with P300, thereby participating to its transcriptional activation.

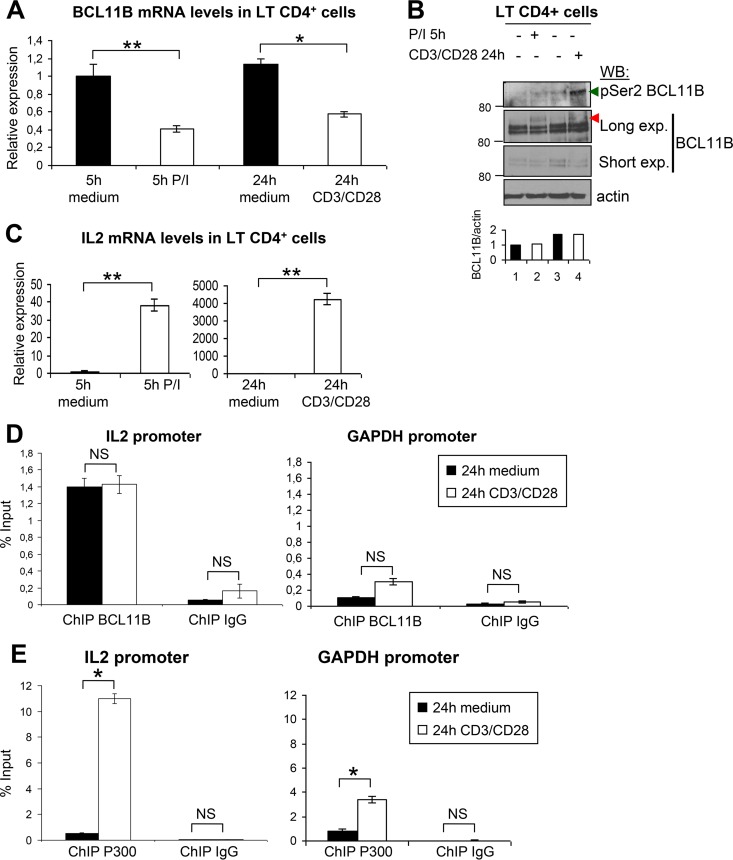

Activation of primary human CD4+ T cells switches BCL11B from a transcriptional repressor to a transcriptional activator of IL-2.

Primary human CD4+ T cells were activated with P/I for 5 h or with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24 h to induce TCR stimulation (23). We observed a twofold repression of BCL11B mRNA levels under both conditions, whereas BCL11B protein levels were roughly identical, suggesting some posttranslational stabilization mechanisms (Fig. 10A and B). Interestingly, a concomitant increase of BCL11B Ser2 phosphorylation and SUMOylation nicely correlating with transcriptional activation of IL-2 was observed, especially with the anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies (Fig. 10B). ChIP analyses were thus performed after 24-h stimulation with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies, a treatment mimicking the canonical activation of T cells through antigen-presenting cells, since IL-2 induction was particularly efficient (ca. 4,000-fold) under these conditions (Fig. 10C). In these conditions, MTA1, MTA3, and RbAp48 mRNA levels also increased (see Fig. S8 in the supplemental material). This activation had no effect on the binding of BCL11B on the IL-2 promoter but led to a strongly increased recruitment of P300 to this region, concomitant with the transcriptional activation of IL-2 (Fig. 10D and E).

FIG 10.

Activation of primary human CD4+ T cells induces phosphorylation of BCL11B Ser2 and the corepressor-coactivator switch on the IL-2 promoter. (A) Activation of primary human CD4+ T cells by P/I or by anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies induced downregulation of BCL11B expression. RT-qPCR experiments were performed to analyze BCL11B expression. (B) Analyses of endogenous BCL11B phosphorylation on Ser2 and SUMOylation in activated human CD4+ T cells. CD4+ T cells were directly lysed in Laemmli buffer, boiled, and analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies, 5 h or 24 h after P/I or anti-CD3/CD28 treatment, respectively. The position of SUMOylated BCL11B proteins is indicated by the red arrowhead. (C) Increase of IL-2 expression in activated human CD4+ T cells. RT-qPCR experiments were performed to analyze IL-2 expression upon activation with P/I (left panel) or anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies (right panel). (D and E) Relative occupancy of BCL11B and P300 on the IL-2 promoter during human CD4+ T-cell activation. BCL11B (D) and P300 (E) occupancy on the US1 site in the IL-2 promoter (19) was analyzed by ChIP-qPCR experiments in human CD4+ T cells with and without activation. Error bars indicate standard deviations. Similar ChIP experiments were performed with control IgG. For each antibody, the ChIP results for the GAPDH promoter used as a nonbinding control are shown. Values that are statistically significantly different are indicated by bars and asterisks as follows: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Values that are not statistically significantly different (NS) are also indicated.

These results therefore show that upon physiological activation of primary human CD4+ T cells, BCL11B through phosphorylation of Ser2 in its N-terminal repression domain is switched from a transcriptional repressor to an activator of IL-2 expression.

DISCUSSION

Multiple posttranslational modifications (PTMs) of a given protein substrate can occur simultaneously or sequentially to modulate its function, localization, and stability through cooperative or antagonizing effects on interacting partners. BCL11B is essential for T-cell development. Recently, BCL11B function was shown to be finely regulated during TCR activation of resting murine thymocytes by a MAPK-initiated dynamic sequence of PTMs. Indeed, treatment with phorbol ester and calcium ionophore resulted in rapid phosphorylation on 23 proline-directed serine/threonine kinase (S/TP) sites, deSUMOylation, dephosphorylation, reSUMOylation, ubiquitination, and ultimately degradation of BCL11B (21, 22, 52). Importantly, this complex pathway facilitates derepression of repressed direct target genes of BCL11B, as shown for Id2, when immature thymocytes need to initiate differentiation programs (21).

Here, we describe a different and much simpler PKC-mediated pathway which through phosphorylation of Ser2 in the BCL11B conserved MSRKKQ motif participates in the upregulation of IL-2, another BCL11B direct target gene, during activation of human CD4+ T cells by PMA-ionomycin (P/I) or by anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies as a surrogate for canonical activation of T cells through antigen-presenting cells (Fig. 11). Notably, this is the first description at the endogenous level of a PTM targeting this important MSRRKQ repression motif shared by several distinct nuclear proteins. The phosphorylation of BCL11B Ser2 has not been detected during differentiation of resting murine thymocytes (90% being double-positive [DP] cells) (21), a population clearly distinct from the human CD4+ T cells analyzed here. However, the N-terminal region was not present in the coverage map of BCL11B (21) since trypsin digests which cut after Arg and Lys residues are predicted to generate hardly detectable MSR peptides.

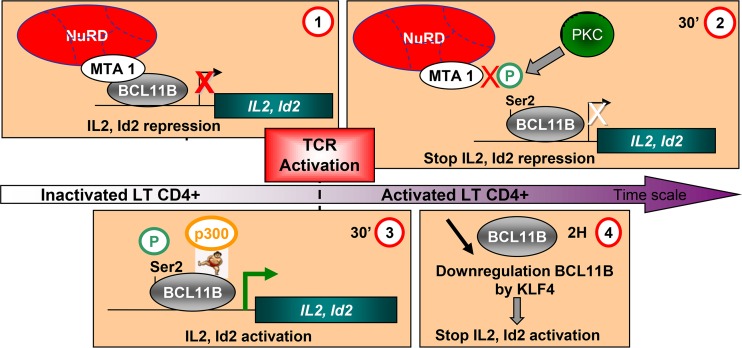

FIG 11.

Working model of the corepressor/activator switch on BCL11B target genes during activation of Jurkat cells or primary human CD4+ T cells. (Step 1) In unstimulated Jurkat or primary human CD4+ T cells isolated from PBMCs from healthy donors, BCL11B bound with MTA1, and NuRD complex represses transcription of direct target genes such as IL-2 and Id2. (Step 2) Upon activation, phosphorylation of Ser2 in the conserved N-terminal repression domain allows disruption of the interaction with MTA1 and hence NuRD repressive complexes, while BCL11B remains bound to the IL-2 and Id2 promoters. (Step 3) Then, SUMOylation on Lys679 in the C-terminal end of BCL11B allows the recruitment of P300 to activate transcription. (Step 4) After 2 to 5 h of treatment, a transcriptional downregulation of BCL11B by KLF4 would stop and/or limit the IL-2 and Id2 activation.

The Ser2 phosphorylation peak in Jurkat cells precedes the SUMOylation peak, but a specific PKC inhibitor has no effect on the SUMOylation of BCL11B (Fig. 6). In contrast, the multiple phosphorylation events induced by the MAPK pathway in murine thymocytes favor the interaction of BCL11B with the deSUMOylase SENP1 (21). Another major difference is the lack of ubiquitination of human BCL11B after prolonged P/I treatment of Jurkat cells. In fact, the decrease in BCL11B protein levels observed after 5 h of activation seems to rely mainly on direct transcriptional repression of BCL11B by KLF4 rather than on BCL11B protein degradation by the proteasome (Fig. 7).

However, these different MAPK- or PKC-mediated pathways both orchestrate the transcriptional activity of BCL11B to allow derepression of direct target genes, albeit through strikingly different mechanisms. Indeed, by performing quantitative ChIP experiments with activated Jurkat cells or purified normal human CD4+ T cells, we observed similar levels of binding of BCL11B to the IL-2 promoter compared to basal conditions. However, in these activating conditions, which result in BCL11B Ser2 phosphorylation, the levels of MTA1 are severely reduced at the IL-2 promoter, whereas P300 levels reciprocally increase in line with the induction of IL-2 expression (Fig. 8 to 10). In the Co-IP experiments (Fig. 8C) where a net increase of BCL11B-P300 interaction is clearly seen, the impact of T-cell activation on BCL11B-MTA1 interaction is relatively low. However, in contrast with Co-IPs, the ChIP experiments were performed on chromatin and are thus more likely to reflect the function of a transcription factor and of its different partners in their natural context (53, 54). In developing murine thymocytes, BCL11B and MTA1 remained associated at the Id2 promoter both in basal conditions and activating conditions, as shown by ChIP experiments (21). However, as stated by these authors, the possibility that MTA1 and/or other NuRD component proteins became posttranslationally modified as a consequence of this treatment has not been investigated in detail. This is an important issue since the C-terminal end of MTA proteins involved in the interaction with MSRRKQ proteins is subject to extensive posttranslational modifications. Notably, the methylation-demethylation of MTA1 lysine 532 regulates its cyclical and signaling-dependent association with NuRD corepressor or nucleosome remodeling factor (NuRF) coactivator complexes, respectively (55). The transcriptional cofactor FOG1 (friend of GATA) also interacts with NuRD through a N-terminal MSRRKQ motif, and this interaction plays a key role for lineage commitment during erythropoiesis and megakaryopoiesis (45, 56, 57). Strikingly, ChIP experiments revealed that NuRD components are present at both repressed and active GATA1/FOG1 target genes (58). These results suggest two possible mechanisms for interaction of MTA1 with different transcription factors depending on the cellular context: (i) binding of MTA1 to the target genes both in active or repressive conditions but with PTMs fine-tuning its interaction with repressive or activating complexes as reported for GATA1/FOG1 or (ii) present only in repressive conditions and loss of interaction in activating conditions due to specific PTMs in short MTA1-interacting motifs, as shown here for PKC-mediated phosphorylation of BCL11B in CD4+ T cells.

Here, we demonstrated that this short motif is necessary and sufficient to mediate binding of BCL11A and BCL11B to the three members of the MTA corepressor family, thus enabling BCL11A, BCL11B, and more generally MSRRKQ-containing proteins to interact with the complete range of NuRD complexes. This highlights their flexibility to participate in various differentiation programs involved in the development of the immune and central nervous systems and to regulate tissue-specific gene expression in many distinct cellular types including T and B cells, ameloblasts or keratinocytes for BCL11B (16), or lymphopoiesis and erythroid precursors for BCL11A (15). Interestingly, the interaction of the BTB/POZ transcriptional repressors HIC1 and BCL6 with MTA1 and MTA3, respectively, are inhibited by acetylation of a lysine residue in different conserved peptidic interaction motifs. HIC1 acetylation on K314 in the MKHEP SUMOylation/acetylation motif negatively regulates its interaction with MTA1, whereas its SUMOylation favors it, notably in the DNA damage response (40, 59). BCL6 acetylation on K379 in the KKYK motif abrogates its ability to interact with MTA3, which is a major repression mechanism controlling germinal center B-cell differentiation (60–62) as well as CD4+ T-cell fate and function (63).

Although our studies have been focused on BCL11B, it is tempting to speculate that similar PTMs could be identified in other MSRRKQ-containing nuclear proteins. Indeed, the developmental regulator SALL1 is certainly regulated by PKC phosphorylation on Ser2, as suggested by in vitro studies (27). For FOG1, the role of Ser2 has been investigated only through alanine scanning experiments which demonstrated that this S2A mutation did not affect the repression potential of a FOG1 1-12-Gal4 chimera (56). However, these in vitro studies or in vivo knock-in models in mice and the crystal structure of RbAp48 (another NuRD component) bound to the 15 N-terminal amino acids of FOG1 have provided compelling pieces of evidence for the key role played by the RKK residues in the conserved MSRRKQ motif (45, 56–58). Whereas Ser2 is involved only in hydrogen bond interaction, these RKK residues are engaged both in hydrogen bond interaction and in ion pair contacts with acidic Glu residues in RbAp48 (49). These strong interactions could be impaired by the negative charge brought by PKC-mediated phosphorylation of the adjacent Ser2 residue as shown for the interaction between the phosphomimetic S2D BCL11B mutant and the related RbAp46 protein (Fig. 3E). Recently, ZNF827 was shown to recruit NuRD to telomeres in cells using alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT) to enable telomere extension. This recruitment relies on RRK residues found in an N-terminal MPRRKQ motif highly homologous to the motif found in FOG, SALL1, and BCL11A/B except for the replacement of Ser2 by a Pro residue (65). Thus, the PKC-mediated phosphorylation of Ser2 that we have demonstrated here for BCL11B would provide to these MSRRKQ-containing proteins a rapid and efficient mechanism to fine tune their interaction via a RRK motif with NuRD.

In conclusion, we have identified a novel mechanism for how the essential regulator of T-cell development BCL11B is regulated by PKC-mediated phosphorylation of Ser2 in its conserved N-terminal repression domain during activation of CD4+ T cells. In addition, this BCL11B N-terminal domain is essential for the transcriptional repression of HIV-1 long terminal repeat (LTR) sequences which thus affects both HIV-1 replication and virus production in CD4+ T lymphocytes (66). In future studies, it would be interesting to explore whether this switch between transcriptional repression and activation by phosphorylation in their MSRRKQ motifs could be generalized to other NuRD-interacting proteins, in particular to BCL11A or FOG1, two important regulators of differentiation programs during normal hematopoiesis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Marion Dubuissez and Sonia Paget are supported by predoctoral fellowships from the University of Lille.

We thank Capucine Van Rechem for critically reading the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.00062-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Avram D, Fields A, Pretty On Top K, Nevrivy DJ, Ishmael JE, Leid M. 2000. Isolation of a novel family of C(2)H(2) zinc finger proteins implicated in transcriptional repression mediated by chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor (COUP-TF) orphan nuclear receptors. J Biol Chem 275:10315–10322. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avram D, Fields A, Senawong T, Topark-Ngarm A, Leid M. 2002. COUP-TF (chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor)-interacting protein 1 (CTIP1) is a sequence-specific DNA binding protein. Biochem J 368:555–563. doi: 10.1042/bj20020496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wakabayashi Y, Inoue J, Takahashi Y, Matsuki A, Kosugi-Okano H, Shinbo T, Mishima Y, Niwa O, Kominami R. 2003. Homozygous deletions and point mutations of the Rit1/Bcl11b gene in gamma-ray induced mouse thymic lymphomas. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 301:598–603. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)03069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avram D, Califano D. 2014. The multifaceted roles of Bcl11b in thymic and peripheral T cells: impact on immune diseases. J Immunol 193:2059–2065. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wakabayashi Y, Watanabe H, Inoue J, Takeda N, Sakata J, Mishima Y, Hitomi J, Yamamoto T, Utsuyama M, Niwa O, Aizawa S, Kominami R. 2003. Bcl11b is required for differentiation and survival of alphabeta T lymphocytes. Nat Immunol 4:533–539. doi: 10.1038/ni927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albu DI, Feng D, Bhattacharya D, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Liu P, Avram D. 2007. BCL11B is required for positive selection and survival of double-positive thymocytes. J Exp Med 204:3003–3015. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li L, Leid M, Rothenberg EV. 2010. An early T cell lineage commitment checkpoint dependent on the transcription factor Bcl11b. Science 329:89–93. doi: 10.1126/science.1188989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li P, Burke S, Wang J, Chen X, Ortiz M, Lee SC, Lu D, Campos L, Goulding D, Ng BL, Dougan G, Huntly B, Gottgens B, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Colucci F, Liu P. 2010. Reprogramming of T cells to natural killer-like cells upon Bcl11b deletion. Science 329:85–89. doi: 10.1126/science.1188063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kastner P, Chan S, Vogel WK, Zhang LJ, Topark-Ngarm A, Golonzhka O, Jost B, Le Gras S, Gross MK, Leid M. 2010. Bcl11b represses a mature T-cell gene expression program in immature CD4(+)CD8(+) thymocytes. Eur J Immunol 40:2143–2154. doi: 10.1002/eji.200940258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gutierrez A, Kentsis A, Sanda T, Holmfeldt L, Chen SC, Zhang J, Protopopov A, Chin L, Dahlberg SE, Neuberg DS, Silverman LB, Winter SS, Hunger SP, Sallan SE, Zha S, Alt FW, Downing JR, Mullighan CG, Look AT. 2011. The BCL11B tumor suppressor is mutated across the major molecular subtypes of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 118:4169–4173. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-318873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kominami R. 2012. Role of the transcription factor Bcl11b in development and lymphomagenesis. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci 88:72–87. doi: 10.2183/pjab.88.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Santo JP. 2010. Immunology. A guardian of T cell fate. Science 329:44–45. doi: 10.1126/science.1191664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu P, Keller JR, Ortiz M, Tessarollo L, Rachel RA, Nakamura T, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. 2003. Bcl11a is essential for normal lymphoid development. Nat Immunol 4:525–532. doi: 10.1038/ni925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sankaran VG, Xu J, Ragoczy T, Ippolito GC, Walkley CR, Maika SD, Fujiwara Y, Ito M, Groudine M, Bender MA, Tucker PW, Orkin SH. 2009. Developmental and species-divergent globin switching are driven by BCL11A. Nature 460:1093–1097. doi: 10.1038/nature08243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bauer DE, Kamran SC, Orkin SH. 2012. Reawakening fetal hemoglobin: prospects for new therapies for the beta-globin disorders. Blood 120:2945–2953. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-292078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Douce V, Cherrier T, Riclet R, Rohr O, Schwartz C. 2014. The many lives of CTIP2: from AIDS to cancer and cardiac hypertrophy. J Cell Physiol 229:533–537. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marban C, Suzanne S, Dequiedt F, de Walque S, Redel L, Van Lint C, Aunis D, Rohr O. 2007. Recruitment of chromatin-modifying enzymes by CTIP2 promotes HIV-1 transcriptional silencing. EMBO J 26:412–423. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cismasiu VB, Adamo K, Gecewicz J, Duque J, Lin Q, Avram D. 2005. BCL11B functionally associates with the NuRD complex in T lymphocytes to repress targeted promoter. Oncogene 24:6753–6764. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cismasiu VB, Ghanta S, Duque J, Albu DI, Chen HM, Kasturi R, Avram D. 2006. BCL11B participates in the activation of IL2 gene expression in CD4+ T lymphocytes. Blood 108:2695–2702. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cismasiu VB, Duque J, Paskaleva E, Califano D, Ghanta S, Young HA, Avram D. 2009. BCL11B enhances TCR/CD28-triggered NF-kappaB activation through up-regulation of Cot kinase gene expression in T-lymphocytes. Biochem J 417:457–466. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang LJ, Vogel WK, Liu X, Topark-Ngarm A, Arbogast BL, Maier CS, Filtz TM, Leid M. 2012. Coordinated regulation of transcription factor Bcl11b activity in thymocytes by the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways and protein sumoylation. J Biol Chem 287:26971–26988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.344176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Filtz TM, Vogel WK, Leid M. 2014. Regulation of transcription factor activity by interconnected post-translational modifications. Trends Pharmacol Sci 35:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azzaoui I, Yahia SA, Chang Y, Vorng H, Morales O, Fan Y, Delhem N, Ple C, Tonnel AB, Wallaert B, Tsicopoulos A. 2011. CCL18 differentiates dendritic cells in tolerogenic cells able to prime regulatory T cells in healthy subjects. Blood 118:3549–3558. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-338780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cherrier T, Le Douce V, Eilebrecht S, Riclet R, Marban C, Dequiedt F, Goumon Y, Paillart JC, Mericskay M, Parlakian A, Bausero P, Abbas W, Herbein G, Kurdistani SK, Grana X, Van Driessche B, Schwartz C, Candolfi E, Benecke AG, Van Lint C, Rohr O. 2013. CTIP2 is a negative regulator of P-TEFb. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:12655–12660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220136110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stankovic-Valentin N, Deltour S, Seeler J, Pinte S, Vergoten G, Guerardel C, Dejean A, Leprince D. 2007. An acetylation/deacetylation-SUMOylation switch through a phylogenetically conserved psiKXEP motif in the tumor suppressor HIC1 regulates transcriptional repression activity. Mol Cell Biol 27:2661–2675. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01098-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lauberth SM, Rauchman M. 2006. A conserved 12-amino acid motif in Sall1 recruits the nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase corepressor complex. J Biol Chem 281:23922–23931. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lauberth SM, Bilyeu AC, Firulli BA, Kroll KL, Rauchman M. 2007. A phosphomimetic mutation in the Sall1 repression motif disrupts recruitment of the nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase complex and repression of Gbx2. J Biol Chem 282:34858–34868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703702200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen L, Meng Q, Jing X, Xu P, Luo D. 2011. A role for protein kinase C in the regulation of membrane fluidity and Ca(2)(+) flux at the endoplasmic reticulum and plasma membranes of HEK293 and Jurkat cells. Cell Signal 23:497–505. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prickett TD, Brautigan DL. 2006. The alpha4 regulatory subunit exerts opposing allosteric effects on protein phosphatases PP6 and PP2A. J Biol Chem 281:30503–30511. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601054200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muller S, Matunis MJ, Dejean A. 1998. Conjugation with the ubiquitin-related modifier SUMO-1 regulates the partitioning of PML within the nucleus. EMBO J 17:61–70. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li W, Jiang Z, Li T, Wei X, Zheng Y, Wu D, Yang Y, Chen S, Xu B, Zhong M, Jiang J, Hu Y, Su H, Zhang M, Huang X, Geng S, Weng J, Du X, Liu P, Li Y, Liu H, Yao Y, Li P. 2015. Genome-wide analyses identify KLF4 as an important negative regulator in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia through directly inhibiting T-cell associated genes. Mol Cancer 14:26. doi: 10.1186/s12943-014-0285-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim YS, Nagy K, Keyser S, Schneekloth SJ Jr. 2013. An electrophoretic mobility shift assay identifies a mechanistically unique inhibitor of protein sumoylation. Chem Biol 20:604–613. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukuda I, Ito A, Hirai G, Nishimura S, Kawasaki H, Saitoh H, Kimura K, Sodeoka M, Yoshida M. 2009. Ginkgolic acid inhibits protein SUMOylation by blocking formation of the E1-SUMO intermediate. Chem Biol 16:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoellein A, Fallahi M, Schoeffmann S, Steidle S, Schaub FX, Rudelius M, Laitinen I, Nilsson L, Goga A, Peschel C, Nilsson JA, Cleveland JL, Keller U. 2014. Myc-induced SUMOylation is a therapeutic vulnerability for B-cell lymphoma. Blood 124:2081–2090. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-584524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hemshekhar M, Sebastin Santhosh M, Kemparaju K, Girish KS. 2012. Emerging roles of anacardic acid and its derivatives: a pharmacological overview. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 110:122–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2011.00833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boulay G, Dubuissez M, Van Rechem C, Forget A, Helin K, Ayrault O, Leprince D. 2012. Hypermethylated in cancer 1 (HIC1) recruits polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) to a subset of its target genes through interaction with human polycomb-like (hPCL) proteins. J Biol Chem 287:10509–10524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.320234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu CS, Ouyang J, Mori E, Nguyen HD, Marechal A, Hallet A, Chen DJ, Zou L. 2014. SUMOylation of ATRIP potentiates DNA damage signaling by boosting multiple protein interactions in the ATR pathway. Genes Dev 28:1472–1484. doi: 10.1101/gad.238535.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Dessel N, Beke L, Gornemann J, Minnebo N, Beullens M, Tanuma N, Shima H, Van Eynde A, Bollen M. 2010. The phosphatase interactor NIPP1 regulates the occupancy of the histone methyltransferase EZH2 at Polycomb targets. Nucleic Acids Res 38:7500–7512. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boulay G, Rosnoblet C, Guerardel C, Angrand PO, Leprince D. 2011. Functional characterization of human Polycomb-like 3 isoforms identifies them as components of distinct EZH2 protein complexes. Biochem J 434:333–342. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dehennaut V, Loison I, Dubuissez M, Nassour J, Abbadie C, Leprince D. 2013. DNA double-strand breaks lead to activation of hypermethylated in cancer 1 (HIC1) by SUMOylation to regulate DNA repair. J Biol Chem 288:10254–10264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.421610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dege C, Hagman J. 2014. Mi-2/NuRD chromatin remodeling complexes regulate B and T-lymphocyte development and function. Immunol Rev 261:126–140. doi: 10.1111/imr.12209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manavathi B, Singh K, Kumar R. 2007. MTA family of coregulators in nuclear receptor biology and pathology. Nucl Recept Signal 5:e010. doi: 10.1621/nrs.05010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Satterwhite E, Sonoki T, Willis TG, Harder L, Nowak R, Arriola EL, Liu H, Price HP, Gesk S, Steinemann D, Schlegelberger B, Oscier DG, Siebert R, Tucker PW, Dyer MJ. 2001. The BCL11 gene family: involvement of BCL11A in lymphoid malignancies. Blood 98:3413–3420. doi: 10.1182/blood.V98.12.3413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Durum SK. 2003. Bcl11: sibling rivalry in lymphoid development. Nat Immunol 4:512–514. doi: 10.1038/ni0603-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hong W, Nakazawa M, Chen YY, Kori R, Vakoc CR, Rakowski C, Blobel GA. 2005. FOG-1 recruits the NuRD repressor complex to mediate transcriptional repression by GATA-1. EMBO J 24:2367–2378. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alqarni SS, Murthy A, Zhang W, Przewloka MR, Silva AP, Watson AA, Lejon S, Pei XY, Smits AH, Kloet SL, Wang H, Shepherd NE, Stokes PH, Blobel GA, Vermeulen M, Glover DM, Mackay JP, Laue ED. 2014. Insight into the architecture of the NuRD complex: structure of the RbAp48-MTA1 subcomplex. J Biol Chem 289:21844–21855. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.558940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kennelly PJ, Krebs EG. 1991. Consensus sequences as substrate specificity determinants for protein kinases and protein phosphatases. J Biol Chem 266:15555–15558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kong KF, Altman A. 2013. In and out of the bull's eye: protein kinase Cs in the immunological synapse. Trends Immunol 34:234–242. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lejon S, Thong SY, Murthy A, AlQarni S, Murzina NV, Blobel GA, Laue ED, Mackay JP. 2011. Insights into association of the NuRD complex with FOG-1 from the crystal structure of an RbAp48.FOG-1 complex. J Biol Chem 286:1196–1203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.195842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Puente LG, Stone JC, Ostergaard HL. 2000. Evidence for protein kinase C-dependent and -independent activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in T cells: potential role of additional diacylglycerol binding protein. J Immunol 165:6865–6871. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.6865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang X, Shen Q, Chen S, Chen S, Yang L, Weng J, Du X, Grabarczyk P, Przybylski GK, Schmidt CA, Li Y. 2011. Gene expression profiles in BCL11B-siRNA treated malignant T cells. J Hematol Oncol 4:23. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-4-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vogel WK, Gafken PR, Leid M, Filtz TM. 2014. Kinetic analysis of BCL11B multisite phosphorylation-dephosphorylation and coupled sumoylation in primary thymocytes by multiple reaction monitoring mass spectroscopy. J Proteome Res 13:5860–5868. doi: 10.1021/pr5007697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li X, Wang W, Wang J, Malovannaya A, Xi Y, Li W, Guerra R, Hawke DH, Qin J, Chen J. 2015. Proteomic analyses reveal distinct chromatin-associated and soluble transcription factor complexes. Mol Syst Biol 11:775. doi: 10.15252/msb.20145504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ji Z, Sharrocks AD. 2015. Changing partners: transcription factors form different complexes on and off chromatin. Mol Syst Biol 11:782. doi: 10.15252/msb.20145936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nair SS, Li DQ, Kumar R. 2013. A core chromatin remodeling factor instructs global chromatin signaling through multivalent reading of nucleosome codes. Mol Cell 49:704–718. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lin AC, Roche AE, Wilk J, Svensson EC. 2004. The N termini of Friend of GATA (FOG) proteins define a novel transcriptional repression motif and a superfamily of transcriptional repressors. J Biol Chem 279:55017–55023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411240200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]