Abstract

In 2008, Texas A&M University Baylor College of Dentistry launched a comprehensive four-year curriculum in evidence-based dentistry (EBD) along with a series of faculty development initiatives to create an EBD culture. The aim of this study was to determine the institution's success in achieving this goal. The assessment tool used was the PEAK instrument, which measures respondents’ EBD Practices, Experience, Attitudes, and Knowledge. Two EBD-trained classes of students and one class untrained in EBD (approximately 100 students in each class) were assessed annually. The faculty were assessed before and after completion of the initiative. Nearly all students responded, with samples ranging from 87 to 102; the faculty response rates were 53% (62/117) in 2009 and 66% in 2013 (81/123). In the results, the trained students scored significantly higher in knowledge than the untrained students at each of the first three PEAK administrations (p≤0.001). Regarding confidence in appraising a research report, the first trained group significantly gained in appropriate use of statistical tests (p<0.001), while the second trained group significantly gained in this aspect and five others (p≤0.032). At the final PEAK administration, the second trained group agreed more than the untrained group that EBD was important for the practice of dentistry (p<0.001). Faculty comfort level with reading peer-reviewed articles increased significantly from 2009 to 2013 (p=0.039). Faculty members who participated in the summer EBD Fundamentals course (n=28) had significantly higher EBD knowledge scores than those who did not participate (p=0.013), and their EBD attitudes and practices were more positive (p<0.05). Students and faculty trained in EBD were more knowledgeable and exhibited more positive attitudes, supporting a conclusion that the college has made substantial progress towards achieving an EBD culture.

Keywords: dental education, evidence-based dentistry, dental curriculum, curriculum development, clinical research, program assessment

Evidence-based care—the integration of the best evidence along with patient preferences and clinical judgment into a treatment decision—is now considered the “gold standard” in delivery of health care.1 Although the introduction of evidence-based dentistry (EBD) into dental curricula in the United States continues to grow, dental school faculty display significant misperceptions about EBD and express concern over perceived barriers to teaching EBD.2 General practitioners in private practice report similar misconceptions and concerns about EBD,3 such that mean concordance between clinical practice and published evidence is only 62% with a range from 8% to 100% depending on the procedure.4 Moreover, relatively few descriptions of curricula that might be instructive for schools considering EBD inclusion have been published.5-9 As with any novel addition to the curriculum, evaluation of the outcomes of the change is critical to determining its effectiveness.10 However, most articles do not present a global view of an EBD curriculum with an evaluation of outcomes.11,12

In 2008, Texas A&M University Baylor College of Dentistry was one of a relatively small number of dental schools awarded an Oral Health Research Education Grant (R25) from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The primary goals of our grant were to implement EBD content in all four years of the curriculum and to familiarize faculty with the EBD principles and methods necessary to effectively interact with students. The overarching aim of these endeavors was to incubate an EBD culture, in which EBD ceased to be something novel or intrusive but rather became an accepted and pervasive part of how our school functioned. After three years of implementation, we described our progress in developing EBD courses and experiences for most of the curriculum as well as progress to date for other faculty and student initiatives.6 With grant funds expended and the products of our EBD efforts having reached a degree of maturity, the goal of this article is to provide a qualitative and quantitative characterization of our successes and our challenges in training our students and in faculty development.

Specifically, the aim of our study was to answer whether all our efforts have resulted in an improvement/increase in EBD attitudes, knowledge, and practices on the part of both students and faculty. It is our hope that this retrospective evaluation will be helpful to those institutions now implementing or planning to implement EBD-based experiences in their curricula.

Materials and Methods

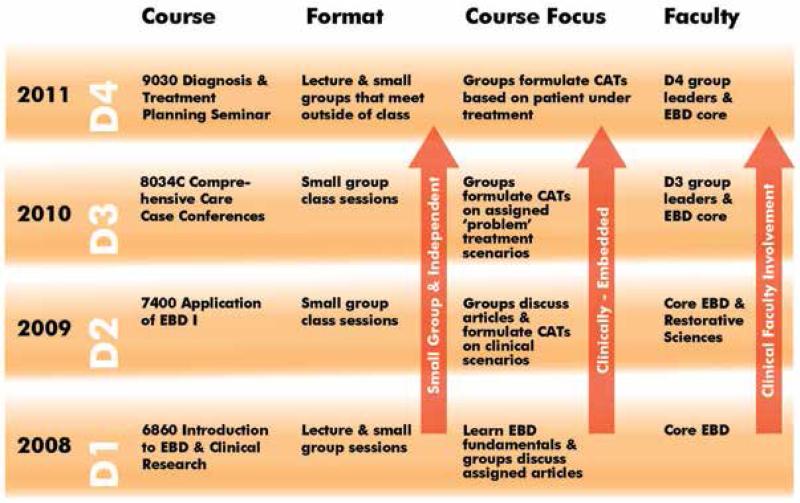

This research was granted exempt status by the Texas A&M University Baylor College of Dentistry Institutional Review Board (IRB protocol #09-27). We chose to introduce our EBD content into the curriculum one year at a time (Figure 1). This process enabled us to focus our efforts on developing only one new course or experience, and it provided a buffer period to build interest in and enthusiasm for this new initiative among the clinical faculty.

Figure 1.

EBD curriculum timeline

An initial didactic course was jointly constructed by an epidemiologist from the Department of Public Health Sciences and a basic scientist trained in the clinical research program at UT Southwestern Medical School. The objective of this first-year EBD course was to introduce students to EBD principles and tools that are the foundation for evaluating the clinical research literature. This two-semester D1 course combined one hour of lecture per week (made interactive via the use of clickers) with nine small-group discussion sessions (two the first semester and seven the second semester). The discussion sessions served as “EBD labs” in which students evaluated clinical research papers that were exemplary of research designs they had studied. The sessions concluded at the end of the second semester with the students presenting Critically Appraised Topics (CATs).

Since it was our core belief that exposing students to EBD throughout their education was important for establishing an EBD culture, EBD experiences were then introduced serially for the D2, D3, and D4 years. For the D2 year, an EBD experience was created to reinforce EBD skills presented in the D1 course. The D2 experience consisted of seven small-group discussions spread over the academic year, in which students discussed articles based on their current coursework and prepared two CATs on scenarios written by D2 faculty. Time for EBD was found in the packed D2 curriculum by slotting students into discussion groups on those afternoons in which they were not scheduled for rotations.

The D3 and D4 EBD experiences represented the crucial transition of EBD into a clinical context. As such, both were incorporated into existing clinical courses. An EBD module was included in six critical thinking scenarios as part of the D3 case conferences in which students present patients they are currently treating. Each scenario dealt with a challenging issue bearing on treatment; as part of this exercise, students were asked to evaluate the evidence for an issue pertinent to the scenario. The D4 EBD experience is a part of the treatment planning course taken by rising D4 students in the summer prior to their final year. Students are expected to work in groups of four or five to identify a clinical question generated by a patient under their treatment. They then interact with each other (using course faculty as advisers) via learning management software (Blackboard) to produce a CAT bearing on the clinical question. All groups then present their CATs to the D4 class and course faculty later in the semester.

Overall, our EBD curriculum has several features of note. First, it takes advantage of the few open spaces in the always crowded curriculum or residing within existing clinical courses. Second, it is delivered mostly in small-group discussion sessions facilitated by faculty, with only the first-year course having a didactic component. Third, it transitions from reading clinical research articles chosen to illustrate a type of research design in D1 to doing a CAT on scenarios written by clinical faculty (end of D1, D2, and D3) to student-driven clinical questions in D4. Finally, along with this increasing clinical embedding of EBD, a greater role in the D3 and D4 years is assumed by clinical faculty, with the EBD core faculty (mostly basic science and public health faculty members) who were active in D1 and D2 serving in a secondary capacity. Figure 1 also summarizes the gradient of increasingly complex EBD skills taught in our dental classes.

Schoolwide events further showcase the EBD efforts of our students. D2 students with the best CATs are encouraged to present them at the annual Scholars Day held in April. This event is a transformed version of our former Research Day, at which basic science presentations by D1 students were attended largely by basic science faculty members. Scholars Day has broadened attendance by expanding the spectrum of presentations to include D2 CATs and clinical case presentations by D3 and D4 students. The inclusion of student-created CATs in this event serves to remind students and faculty alike of the role played by EBD in our curriculum, much as has the inclusion of an EBD update in each faculty retreat beginning in 2009.

Faculty Development for EBD Implementation

From the beginning of our initiative, we knew that convincing our clinical faculty to acquire the tools of EBD and to appreciate its value would be an even more difficult task than devising and implementing the EBD curriculum. We were concerned that many clinical faculty members would have lukewarm enthusiasm at best for EBD and some would be highly skeptical of its value to themselves or the curriculum. Because they must model EBD during the D3 and D4 years, we realized that participation and buy-in by clinical faculty would be a critical determinant of whether EBD became an integral part of the school culture or was viewed as just another hoop to jump through.

With this in mind, we designed a course for clinical faculty members on the fundamentals of EBD with the goals of equipping them to effectively interact with students and to introduce EBD content into their teaching. A hallmark of the course structure was the incorporation of adult learning techniques (discussion, hands-on experiences) wherever possible. This summer course focused on tools needed to assess research rather than to perform research, e.g., only those elements of statistics and epidemiology important to assessing research results while also stressing research design and the hierarchy of evidence. Topics and activities covered in a typical summer faculty EBD Fundamentals course (about 23 hours, total) are shown in Table 1. Further details of our approach were provided in an American Dental Education Association Commission on Change and Innovation in Dental Education (ADEA CCI) commentary by one of the authors.13

Table 1.

Topics covered in EBD Fundamentals course for faculty

| Session | Topic |

|---|---|

| 1 | What is EBD? What constitutes good evidence? |

| 2 | Formulation of a focused question: what is a PICO? |

| 3 | How to search using PubMed |

| 4 | How to evaluate a study: five questions to answer |

| 5 | Are appropriate methods used to infer differences between groups or associations between variables? |

| 6 | Is the sample size appropriate to answer the question? |

| 7 | To what extent are sources of bias and confounding controlled? |

| 8 | How good is the quality of evidence presented? |

| 9 | What is a Critically Appraised Topic (CAT)? |

| 10 | Are the results generalizable and/or applicable to clinical practice? |

| 11 | Participants discuss articles: case studies, observational studies |

| 12 | Participants discuss articles: case control, cohort studies |

| 13 | Participants discuss articles: randomized clinical trials, systematic reviews |

| 14-16 | Participants present CATs |

We encouraged faculty interest in EBD by using grant funds to support faculty attendance at the American Dental Association (ADA) Champions Conference, the Forsyth EBD course, EBD/prosthodontics meetings, and a course for faculty training to perform systematic reviews. In addition, each annual faculty retreat since 2009 has included a progress report on the initiative (the EBD Update), and the 2012 retreat was entirely devoted to “The Benefits of Evidence-Based Dentistry for Patient Care.” Most recently, the 2013 Faculty Calibration Workshop prompted a series of faculty EBD presentations on controversial clinical topics (Table 2), an occurrence that would never have happened prior to 2009.

Table 2.

Faculty EBD presentations, 2012-13

| Topic |

|---|

| • Clinical Research: Making It Happen at BCD |

| • Sealants vs. Preventive Resin Restorations vs. Definitive Restorations |

| • Amalgam vs. Composite Restorations for Posterior Teeth |

| • The Need for Survey Crowns With Removable Partial Dentures |

| • Do Dental Radiographs Increase Risk of Meningioma? |

| • Benefits and Risks of Prophylactic Third Molar Extractions |

| • Posts vs. No Posts |

| • Vital Pulp Therapy |

| • Endodontics: Retreatment vs. Implant Placement |

| • All Ceramic Restorations for Posterior Teeth |

| • Managing Oral Health in Patients with Systemic Disease and Disorders |

PEAK Instrument Development

Our primary tool for assessing change was the PEAK instrument, which measures Practices, Experience, Attitudes, and Knowledge about EBD (the instrument is available from the corresponding author). The four sections had questions relating to the sources of information typically accessed by faculty or student respondents (practices), their previous experience with critical thinking and research, their attitudes about research and evidence-based practice related to dentistry, and finally a test of their knowledge of EBD principles. There were 17 practice questions, 10 prior experience questions, 19 attitude questions, and 10 knowledge questions. Some of the questions related to attitudes and practices were adapted from an earlier version of an EBD instrument (J. Rugh, personal communication, 2008; later described in Hendricson et al.10). Our knowledge questions were unique to the instrument and addressed the meaning or interpretation of a paragraph adapted from a published report on a topic of clinical interest. Answers to all knowledge questions included “don't know” as an option to discourage guessing.

The development of the PEAK occurred in the first year of the project (2008-09). Three project leaders, who were EBD and assessment experts, developed the initial questions, and the PEAK was then pretested by the entire project Steering Committee (n=10). An additional pretesting was conducted with the D1 students (n=104) in spring 2009. In subsequent versions of the survey, the knowledge questions were revised by EBD faculty members (three each year) to accurately reflect our D1 course content at a moderate to high level of difficulty. As these were the faculty who taught the EBD courses, this process strengthened the validity of the instrument. All other questions in the various sections remained the same over the course of the project, although the experience questions were used only for incoming D1 students. The faculty PEAK instrument had minor differences in question wording, with the knowledge items being exactly the same.

The internal consistency or reliability of the knowledge questions was measured with the Cronbach's alpha test. The first pretesting administration had a low reliability of 0.247, so the knowledge section was modified for subsequent administrations. The reliability scores were 0.801 for the second year, 0.828 for the third year, and 0.788 for the fourth year. With the obvious exception of the first-year alpha score (which almost certainly reflects our learning curve in how to construct these tests), these scores indicate that the results were a reliable measure of student knowledge of the EBD principles they were being taught in the curriculum.

Research Design and Analysis

At the beginning of the project in fall 2008, we had a natural untrained (i.e., EBD-naïve) cohort of D2 students who had not received any training in their D1 year; this group served as a control for the trained D1 students. The PEAK was administered to students in the fall for each beginning D1 class and then in the spring for D2, D3, and D4 (approximately 100 for each class). The only exception was year one in which the first administration was not conducted until spring 2009 due to the time needed to develop the instrument. Since there was an additional EBD-trained class that started in fall 2009, the PEAK was administered a total of five times over the course of the project. The PEAK was administered to the full-time faculty (80% FTE or higher) as a baseline in 2009, prior to the beginning of the first summer faculty EBD Fundamentals course and again in 2013 at the end of the project.

The research question for both students and faculty was whether EBD attitudes, knowledge, and practices had improved/increased over the project period. To analyze knowledge, the knowledge score for each student member was summed into a total score, and the average of those was compared between classes and over the project period. Faculty scores were summed in the same manner. Most outcome variables were ordinal and/or non-normally distributed, so Mann-Whitney tests were used throughout for between-group comparisons (α=0.05). When comparing student scores at more than two time points, Bonferroni corrections were used to maintain overall (experiment-wise) α-levels of 0.05.

Results

As students were required to complete the PEAK, nearly all students responded, with samples ranging from 87 to 102; each class was sampled annually for three years, except for the first trained cohort, which was tested over four years. As faculty members could only be strongly encouraged to participate, the faculty response rates were 53% (62/117) in 2009 and 66% in 2013 (81/123).

Students’ EBD Knowledge

Figure 2 shows the average percentage of correct scores on the knowledge portion of the PEAK as students progressed from their D1 year to their D3 or D4 year. The class scores in red are for the cohort that started its D1 year prior to implementation of the EBD initiative, i.e., the EBD-naïve group. Their mean scores changed relatively little from when they were first tested as D2s through their graduation.

Figure 2. Student knowledge scores from PEAK.

Note: Symbols represent mean scores for each class. All between-class differences at each test administration (PEAK1, PEAK2, etc.) were highly significant, after Bonferroni corrections (p≤0.001), with the exceptions of the differences between the two trained groups in 2011 and between the two untrained groups at its first administration (PEAK1). Thus, despite a decline in the Trained 1 group after the D2 year, the two trained groups maintained significant gains over their untrained counterparts. The gains in the Trained 2 group from D2 to D3 are particularly encouraging.

The green line on the figure reflects the first group of trained students. The knowledge scores, initially twice as high as the EBD-naïve cohort, rose about 15% in the D2 year and then dropped about 20% to a plateau in the D3 and D4 years. Our second trained cohort, represented by the yellow line, shows a different, and potentially more promising, trajectory. However, the reason that the rise in mean score appears so dramatic is because the score for the D1 year reflects the PEAK administered prior to the EBD course, i.e., a pre-training assessment. Although this makes the rise in the D2 score more pronounced, it should be noted that the D1 score in this cohort is almost exactly equal to that in the untrained group depicted in red.

The Mann-Whitney U-tests demonstrated highly significant differences between the trained classes and their untrained counterparts at each of the three administrations of the PEAK and between the trained D3s and D4s at the last administration of the PEAK (p≤0.001; all still significant even after a stringent Bonferroni corrected α of 0.0083 was used for pairwise comparisons). These data clearly indicate that the EBD courses and experiences implemented beginning in 2009 have increased the EBD knowledge base of our students, albeit with some fluctuation over the course of their education.

Students’ EBD Attitudes

Of paramount importance are the attitudes regarding EBD that our graduates take with them as they embark on practice. Various attitudes were compared between the first and last administrations of the PEAK instrument to identify changes over time. In terms of confidence in appraising various aspects of a published research report, the first trained group only significantly improved in the area of appropriate use of statistical tests (p<0.001). However, the second trained group significantly improved in confidence in all aspects of appraising a research report. For this group, all the following aspects were significant or highly significant: appropriateness of the study design (p<0.001); sources of bias in the study design (p=0.004); adequacy of the sample size (p=0.032); generalizability of the findings (p<0.001); appropriate use of statistical tests (p=0.030); and overall value of the research report (p<0.001).

Although we did not see an increased level of agreement with evidence-based concepts in the first trained group over the project period, there was clearly an increased level of support in the second trained group. The second trained group agreed more than untrained students with all of the following concepts at the final administration of the PEAK with p-values <0.001: evidence-based dentistry should be an integral part of the dental school curriculum; evidence-based practice improves the quality of patient care; I support evidence-based dentistry principles more than I did a year ago; and the critical appraisal skills pertinent to evidence-based dentistry have changed the way I read clinical articles.

The first inclusion of EBD-related questions in the college's 2013 survey of graduating dental students suggests progress in developing positive attitudes toward EBD skills and practices (Figure 3). This survey indicated that almost all of the 101 students polled felt confident in their ability to seek out and evaluate evidence and to apply these skills to clinical dilemmas, and 94% agreed that the EBD training they received would make them better dentists.

Figure 3.

2013 dental students’ graduation survey after four years of EBD (n=101)

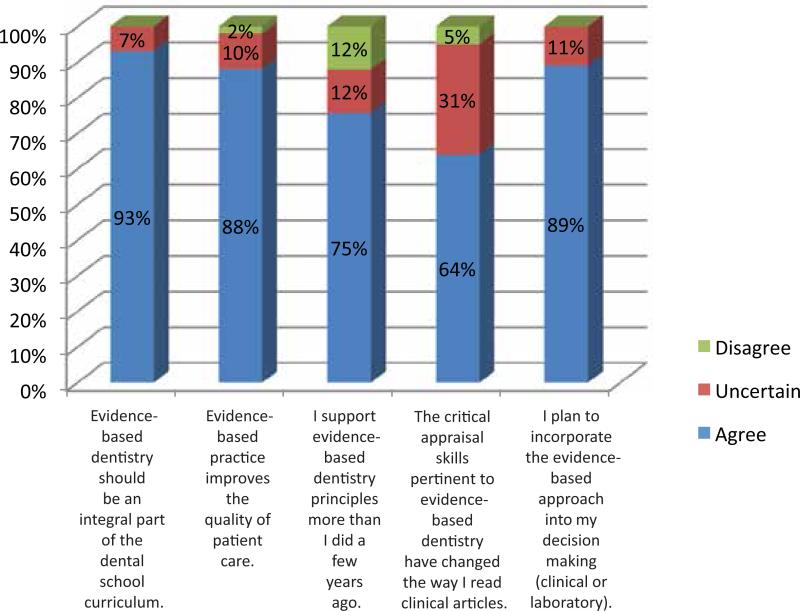

Faculty EBD Knowledge and Attitudes

For the faculty members, their high level of support for EBD principles in the 2013 administration of PEAK is shown in Figure 4 (all full-time faculty respondents, n=81/115). Their belief that EBD should be an integral part of the dental curriculum (93%), that it improves the quality of patient care (88%), and their support for EBD principles (75%) all increased over time, albeit not to a significant extent. There was also no significance difference in mean knowledge score from 2009 to 2013. However, these faculty members’ comfort level with reading peer-reviewed articles did increase significantly from 2009 to 2013 (p=0.039).

Figure 4.

2013 faculty PEAK results (n=81/115, 70% response)

Over time, knowledge and support for EBD were considerably strengthened among faculty members who participated in the summer EBD Fundamentals course. In the subset of faculty who had been trained when the 2013 PEAK was administered (n=28/34), EBD knowledge scores were significantly higher (p=0.013) than the untrained faculty (n=53). In addition, attitudes towards EBD (comfort level with reading research articles and with pertinent critical appraisal skills needed for reading research articles) and EBD practices (read peer-reviewed journals more) were significantly higher in this cohort of faculty (p<0.05). Although EBD-trained faculty members were more positive about incorporating clinical research into their practice or teaching than their untrained counterparts, this difference was not statistically significant.

Other Outcomes of Faculty Development

Over five years (as of September 2014), 43 full-time faculty members and one alumnus have participated in the summer EBD Fundamentals course, including the chair of our largest department (Restorative Sciences), the associate dean for clinical affairs, and most of the group leaders in the D3 and D4 courses. Faculty graduates of this course have been instrumental in creating the D3 and D4 EBD experiences, devising EBD content and experiences for dental hygiene seniors, and presenting a continuing education course on EBD to alumni. In addition, individual faculty members have introduced EBD-related exercises into their courses, as they indicated in the 2013 PEAK administration. A few examples include: article-based case studies in gross anatomy combining both EBD and gross anatomy content; presentation of a CAT in fixed prosthodontics evaluating the evidence for “Posts vs. No Posts in Anterior Root Canal-Treated Teeth That Need Crowns”; presentation of EBD-based guidelines for treatment of patients taking bisphosphonates, hip implants, and with implantable electrical cardiac devices (dental courses); and presentation of EBD-based guidelines for fluoride use and interproximal aids in ultrasonic treatment (dental hygiene).

The EBD initiative, originally designed for the dental curriculum, has also generated salutary effects in our dental hygiene curriculum. Based largely on efforts by dental hygiene faculty who were participants in our EBD Fundamentals course, additional lecture content in research design was added to the Research Methods course taken by DH2 students. In addition, beginning in 2012, groups of DH2 students now are required to present CATs based on clinical scenarios devised by dental hygiene faculty to their classmates and faculty in the Theory of Dental Hygiene Practice course.

Discussion

In our earlier assessments, the trained students in 2009 were significantly more supportive of EBD principles, believed that EBD had changed the way they read clinical articles, and as expected, performed much better than the untrained D2 students on the knowledge portion of the PEAK. A follow-up comparison of the same groups two years later indicated that the knowledge gap was maintained.14 Also, the trained students reported more confidence in appraising all aspects of research reports.6 In this longitudinal view of our five-year project, these results continue to hold up. The trained students had greater EBD knowledge, greater confidence in appraising research reports, and a stronger belief that EBD was important for dental practice.

From the initiation of this project, we have employed a wide variety of measures to encourage student and faculty participation in EBD-related activities and training and to maintain this emphasis throughout the four-year curriculum. Our goal was to instill an EBD culture in which EBD is a normal or accepted component of clinical decision making. The qualitative judgment of most EBD core faculty (about six in any given year) is that each class contains a subset of students who really “get” EBD and like it, a subset that does not see much point in it, and a large middle subset that sees the relevance but is unenthusiastic about it. Our quantitative assessments demonstrate what might be the outcome of such a mix: modest increases in EBD knowledge scores overall from 2009 to 2013 that clearly exceed those in untrained students predating the introduction of EBD. However, more recent assessments provide a more encouraging note: PEAK surveys of D3 and D4 students in 2012 and of graduating seniors in 2013 suggest that these students have absorbed the importance of EBD principles and feel confident that they can and will employ EBD as needed in practice.

Although mean EBD knowledge scores for all faculty did not improve significantly from 2009 to 2013, the subset of faculty members who had attended the EBD Fundamentals course did experience significant gains. They had significantly higher knowledge scores, read more peer-reviewed articles, and were more confident about appraising research articles than faculty members who had not attended the course. This points to the importance of intensive training for faculty in EBD.

We are not aware of many studies that have attempted to make assessments comparable to those described in our study. The closest approximation appears to be the research conducted by Hendricson et al., who devised an assessment instrument to assess knowledge, attitudes, access, and confidence regarding EBD.10 They found that EBD faculty attitudes and knowledge were considerably more positive than those of D2 students or residents prior to training, but that the attitudes toward and knowledge of EBD increased significantly in both D2 students and residents following training via EBD coursework. Although our study utilized a different design (with comparison of trained versus untrained cohorts and change in the same cohort over time), our overall results are similarly positive but are distinctive in their consideration of change over multiple years. In our study, faculty knowledge scores and attitudes increased over time, but only to a significant extent among faculty who attended our summer EBD Fundamentals course. In an evaluation of EBD training at a different dental school, Teich et al. reported that 46% of D3 students who had received EBD training in their D1 year expressed doubts about the use of literature in supporting clinical aspects of the treatment plan and only 40% chose articles with a high level of evidence in support of a treatment plan.12 Although our data do not directly address their findings, our D3 knowledge scores in the second (but not the first) trained group were increased, and our graduating seniors showed very positive attitudes regarding the utility of EBD in clinical practice.

There were some problems associated with starting a whole new EBD curriculum. The first-year course was not very popular overall at its inception because it was a one-credit-hour course that students regarded as taking time away from the heavyweight basic science courses. The discussion sessions were received more favorably than the lectures. However, reconsideration of course content and sequencing of topics, in some instances prompted by student comments, has resulted in a gradual but steady improvement in ratings of the course by students (from 2.9/5.0 in 2009 to 4.1/5.0 in 2013). The addition of a statistics course as a required prerequisite for admission has also helped student preparation for the demands of this unusual course.

Although knowledge scores for the first trained cohort were elevated over the untrained students in all four years, there was a drop-off in years D3 and D4. This may represent growing pains associated with placing the new EBD modules in clinical courses. Compared to the more structured nature of the D1 and D2 courses and the reinforcement of EBD knowledge in faculty-facilitated small groups, the insertion of the EBD experience into courses with a largely clinical focus may have diluted the attention from EBD. The continuously improving knowledge performance of the second trained group may indicate that EBD is gaining in importance in the clinical course.

Another problem centers on the perpetual struggle for time in the crowded dental curriculum. A promising attempt to use residents as facilitators in the D2 small-group sessions failed because of scheduling and availability considerations. More time for EBD in the D4 year is needed. The total faculty time required to staff the small-group sessions in the D1-D4 years was 748 hours per year (divided equally between the fall and winter semesters), a possibly unsustainable number that has been shouldered largely by the core EBD faculty in basic sciences and public health sciences. This could be alleviated, and the EBD experience strengthened, by clinical faculty assuming primary responsibility for the D3 and D4 EBD experiences. Finally, we clearly need to persuade more clinical faculty members to participate in the summer EBD Fundamentals course.

Although in our judgment we have not fully achieved the EBD culture we envisioned, we have made clear progress toward this goal. Our assessments indicate that this initiative has increased/improved the EBD knowledge, attitudes, and practices of our students and faculty. Additionally, the course director of the summer EBD Fundamentals course for faculty has observed that (after more than 100 hours) basic science participants have been compelled to learn more about dentistry and clinical research. Similarly, participating clinicians have had to delve into dental specialty areas beyond their usual comfort zone. Moreover, this initiative has enhanced communication among faculty members and perhaps even increased their understanding of and respect for one another.

In future developments, aside from the curricular and faculty development aspirations noted above, connecting our EBD initiative to extramural efforts with common goals could enrich the experience for our faculty and students. For example, practice-based research networks (PBRNs), established to use calibrated private dental practices to investigate questions of importance to clinicians, are now almost ten years old15 and organized regionally.16 Finding a way to inform our students and perhaps involve our faculty in the work of our regional PBRN would demonstrate a “real-world” use of EBD that could invigorate our faculty and alert our students to future possibilities for clinical research involvement. As clinical research articles from PBRN-directed studies have increased in the last couple of years, the use of these articles in our D1 and D2 courses should reinforce student knowledge of the PBRNs and the possibility of future participation. Also, our dental students might start learning about PBRNs closer to home, because Baylor's Department of Orthodontics currently operates its own intramurally funded PBRN.17 Finally, a truly worthy long-term goal would be to incorporate questions about use of EBD in practice into our five-year alumni surveys. Whether EBD becomes a functional tool for practicing dentists or merely a fashionable buzzword will ultimately be decided in this setting.

It would not have been possible to achieve the successes we describe above without the efforts of faculty champions for EBD. As one might imagine, early on in this endeavor, the naysayers were loud and influential. It took the dogged persistence of several faculty members, who took it upon themselves to become well versed in EBD, to shift the perception of EBD from “intrusive novelty” to “rational approach to improving oral health care.” Garnering consistent administrative support, especially from the dean, for facilitating and advancing this initiative, was also critical. Additionally, the most recent accreditation standards that mandated the inclusion of EBD in the curriculum have served to reinforce the perceived value of our EBD initiative among faculty and administrators.

Conclusion

Using an Oral Health Research Education Grant (R25) from the NIDCR, we developed considerable student and faculty activities for infusing EBD into our curricula and culture. The outcomes were that students and faculty became increasingly knowledgeable about EBD and supportive of teaching and using EBD in dental practice. One of the most consistent outcomes was the increased confidence that students and faculty members gained in appraising research reports. This is important because dentists need this skill to find and apply the best possible evidence to their clinical decision making. The activity that had the most impact on faculty knowledge and support was the summer EBD Fundamentals course. The college has made significant progress towards achieving an EBD culture, but it is an ongoing effort that has required substantial curriculum time, faculty effort, and administrative support. Ultimately, we believe that this educational effort will improve the quality of oral health care provided by our graduates.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIDCR grant DE18883. The major curricular initiative and its evaluation described in this article could not have been accomplished without the substantial efforts of many dedicated individuals. We would like to thank those Texas A&M University Baylor College of Dentistry faculty members who were instrumental in the development of the grant and the curricular and/or extracurricular components (listed alphabetically): Hoda Abdellatif, Charles Berry, Janice DeWald, Rena D'souza, Lavern Holyfield, Bob Hutchins, Dan Jones, Steve Karbowski, Kathy Muzzin, Susan Roshan, Robert Spears, and Beverly York.

Footnotes

Disclosure

None of the authors has any relevant conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Dr. Robert J. Hinton, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Texas A&M University Baylor College of Dentistry.

Dr. Ann L. McCann, Academic Affairs, Texas A&M University Baylor College of Dentistry.

Dr. Emet D. Schneiderman, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Texas A&M University Baylor College of Dentistry.

Dr. Paul C. Dechow, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Texas A&M University Baylor College of Dentistry..

REFERENCES

- 1.Kishore M, Panat SR, Aggarwal A, et al. Evidence-based dental care: integrating clinical expertise with systematic research. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:259–62. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/6595.4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marshall TA, Straub-Morarend, Qian F, Finkelstein MW. Perceptions and practices of dental school faculty regarding evidence-based dentistry. J Dent Educ. 2012;77(2):146–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Straub-Morarend CL, Marshall TA, Holmes DC, Finkelstein MW. Toward defining dentists’ evidence-based practice: influence of decade of dental school graduation and scope of practice in implementation and perceived obstacles. J Dent Educ. 2013;77(2):137–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norton WE, Funkhouser E, Makhija SK, et al. Concordance between clinical practice and published evidence: findings from the national dental practice-based research network. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145:22–31. doi: 10.14219/jada.2013.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rugh JD, Hendricson WD, Hatch JP, Glass BJ. The San Antonio CATS initiative. J Am Coll Dent. 2010;77:16–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hinton RJ, Dechow PC, Abdellatif H, et al. The winds of change: creating an EBD culture at Baylor College of Dentistry. J Dent Educ. 2011;75(2):279–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palcanis KG, Geiger BF, O’Neal MR, et al. Preparing students to practice evidence-based dentistry: a mixed methods conceptual framework for curriculum enhancement. J Dent Educ. 2012;76(12):1600–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stafford GL. Fostering dental faculty collaboration with an evidence-based decision making model designed for curricular change. J Dent Educ. 2014;78(3):349–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marshall TA, Straub-Morarend CL, Handoo N, et al. Integrating critical thinking and evidence-based dentistry across a four-year dental curriculum: a model for independent learning. J Dent Educ. 2014;78(3):359–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hendricson WD, Rugh JD, Hatch JP, et al. Validation of an instrument to assess evidence-based practice knowledge, attitudes, access, and confidence in the dental environment. J Dent Educ. 2011;75(2):131–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rugh JD, Sever N, Glass BJ, Matteson SR. Transferring evidence-based information from dental school to practitioners: a pilot “academic detailing” program involving dental students. J Dent Educ. 2011;75(12):1316–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teich ST, Demko CA, Lang LA. Evidence-based dentistry and clinical implementation by third-year dental students. J Dent Educ. 2012;77(11):1286–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hinton RJ. Guest perspective: teaching evidence-based dentistry to clinical faculty. [22 Apr. 2014];ADEA-CCI Liaison website. 2012 Nov; At: www.adea.org/Secondary.aspx?id=17344.

- 14.Higginbotham MG, McCann AL, Schneiderman ED, et al. Improving the EBD skills of dental students through curricular innovation.. American Association for Dental Research Annual Meeting; Tampa, FL. March 2012; Abstract #156901. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benjamin P. Promoting evidence-based dentistry through “the dental practice-based research network.”. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2009;9:194–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilbert GH, Williams OD, Korelitz JJ, et al. Purpose, structure, and function of the United States national dental practice-based research network. J Dent. 2013;41:1051–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown MD. Master's thesis in Oral Biology. Texas A&M University Health Science Center (UMI 1539086); 2013. A practice-based research approach evaluating the prevalence and predisposing etiology of white spot lesions. [Google Scholar]