Abstract

The human long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) HOTAIR acts in trans to recruit the Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) to the HOXD gene cluster and to promote gene silencing during development. In breast cancers, overexpression of HOTAIR increases metastatic potential via the repression of many additional genes. It has remained unclear what factors determine HOTAIR-dependent PRC2 activity at specific genomic loci, particularly when high levels of HOTAIR result in aberrant gene silencing. To identify additional proteins that contribute to the specific action of HOTAIR, we performed a quantitative proteomic analysis of the HOTAIR interactome. We found that the most specific interaction was between HOTAIR and the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) A2/B1, a member of a family of proteins involved in nascent mRNA processing and RNA matchmaking. Our data suggest that A2/B1 are key contributors to HOTAIR-mediated chromatin regulation in breast cancer cells: A2/B1 knockdown reduces HOTAIR-dependent breast cancer cell invasion and decreases PRC2 activity at the majority of HOTAIR-dependent loci. We found that the B1 isoform, which differs from A2 by 12 additional amino acids, binds with highest specificity to HOTAIR. B1 also binds chromatin and associates preferentially with RNA transcripts of HOTAIR gene targets. We furthermore demonstrate a direct RNA–RNA interaction between HOTAIR and a target transcript that is enhanced by B1 binding. Together, these results suggest a model in which B1 matches HOTAIR with transcripts of target genes on chromatin, leading to repression by PRC2.

Keywords: long noncoding RNAs, HOTAIR, RNA matchmaking, chromatin, Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2)

INTRODUCTION

The regulated expression of the genome requires the formation of facultative heterochromatin (fHC) (Trojer and Reinberg 2007), which stably represses transcription. Although heterochromatin is essential for normal human development, dysregulation can promote cancer by altered expression of oncogenic and tumor suppressor genes. One critical fHC component in both normal development and cancer is the Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) (Margueron and Reinberg 2011). The recruitment of PRC2 to target genes results in the methylation of lysine 27 on histone 3 (H3K27me), a histone mark that triggers formation of repressed chromatin (Simon and Kingston 2009). PRC2 components are frequently up-regulated in multiple cancer types and can promote neoplastic transformation (Varambally et al. 2002; Bracken et al. 2003; Kleer et al. 2003). The mechanism of aberrant fHC initiation is poorly understood, because human PRC2 does not bind to a specific DNA sequence in the genome (Simon and Kingston 2013). Recent work has shown that PRC2 can be directed by certain long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) to key genomic loci regulated by the formation of facultative heterochromatin (Rinn et al. 2007; Gupta et al. 2010; Margueron and Reinberg 2011; Davidovich and Cech 2015). However, PRC2 also readily binds to the nascent transcripts of actively transcribed genes (Davidovich et al. 2013; Kaneko et al. 2013), which suggests additional factors are required to regulate the targeted silencing activity of PRC2.

One of the most intriguing trans-acting lncRNAs that regulates PRC2 localization is HOTAIR, a ∼2200-nt transcript derived from the HOXC gene cluster (Rinn et al. 2007). During normal developmental patterning, HOTAIR is involved in silencing a 40-kb region of the HOXD cluster, located on a separate chromosome from HOXC (Rinn et al. 2007; Li et al. 2013a). More recently, this lncRNA has been shown to associate with hundreds of additional sites in the genome and to initiate broad changes in gene expression when overexpressed (Gupta et al. 2010; Tsai et al. 2010; Chu et al. 2011). HOTAIR is a critical regulator of metastasis: In breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma, and other cancers, HOTAIR is frequently overexpressed and is associated with poor survival and increased metastases (Gupta et al. 2010; Li et al. 2013b; Liu et al. 2013; Tang et al. 2013). The functional importance of HOTAIR has also been demonstrated in multiple breast cancer cell lines, in which HOTAIR overexpression increases invasion and metastasis (Gupta et al. 2010).

HOTAIR has been demonstrated to interact with two histone modifying complexes: The 3′ end of HOTAIR binds the LSD1/Co-rest/REST demethylase complex, while the 5′ portion of HOTAIR binds PRC2 (Tsai et al. 2010). HOTAIR has been suggested to recruit both complexes to target sites to generate a repressed chromatin state (Gupta et al. 2010; Tsai et al. 2010). However, the mechanism by which HOTAIR localizes to the genome and enables PRC2 activity is not known, suggesting that additional factors may contribute to the specificity of HOTAIR-mediated gene silencing. Using quantitative mass spectrometry, we profiled the proteins that associate with the HOTAIR RNA. Our work reveals that the heterogenous ribonucleoproteins A2/B1 interact with HOTAIR and regulate its activity. Although the two isoforms differ only by a 12-amino acid amino-terminal sequence (Burd et al. 1989), the B1 isoform preferentially associates with HOTAIR. A2/B1 have been previously implicated in lncRNA-dependent gene repression (Carpenter et al. 2013), but the mechanism is unknown. We determined that hnRNP A2/B1 are required for HOTAIR-dependent cellular invasion and methylation of H3K27 at HOTAIR-regulated genomic loci, and thus identified A2/B1 as a critical new regulator of HOTAIR activity. To begin to understand the molecular mechanism of A2/B1 in HOTAIR regulation, we demonstrate that the B1 isoform broadly binds to chromatin but HOTAIR specifically stimulates chromatin association of B1. We additionally find that B1 interacts preferentially with the RNA transcripts of HOTAIR target genes compared with other mRNAs. HnRNP A/B family proteins are RNA–RNA matchmakers that can promote RNA annealing of snRNAs and their specific pre-mRNA splicing targets (Kumar and Wilson 1990; Munroe and Dong 1992; Mayeda et al. 1994; Portman and Dreyfuss 1994; Weighardt et al. 1996). We therefore examined the role of B1 in lncRNA–mRNA association, and found that HOTAIR can make an intermolecular RNA–RNA interaction with a target gene RNA, which is enhanced by B1. Our results suggest a model where B1 acts on chromatin to match HOTAIR and the transcripts of HOTAIR target genes to promote specific initiation of PRC2-dependent heterochromatin.

RESULTS

In vitro identification of HOTAIR-interacting proteins

To identify proteins that specifically interact with HOTAIR, we performed in vitro RNA pulldown experiments. We generated in vitro transcripts of full length, spliced HOTAIR or, as a control lncRNA, the antisense sequence to the firefly luciferase mRNA (anti-Luc), which is of similar length and GC content as HOTAIR. The transcripts also included 10 tandem copies of a MS2 RNA aptamer at their 3′ ends to allow purification of the RNA via MS2-Maltose binding protein (MS2-MBP) conjugated to amylose resin (Fig. 1A; Lee et al. 2012). We incubated the tagged in vitro transcripts with nuclear extracts from HeLa or MDA-MB-231 cells, and purified proteins associating with the HOTAIR or the anti-Luc lncRNAs and a no RNA control. qRT-PCR confirmed that our pulldown strategy consistently recovered ∼40% of the HOTAIR in vitro transcript and similar amounts of the tagged anti-Luc transcript used as a negative control (Supplemental Fig. S1A,B). When we examined the proteins associated with these transcripts, we found that the HOTAIR transcript readily bound to its previously identified interaction partner, EZH2 (Supplemental Fig. S1C). However, EZH2 also bound to the anti-Luc RNA (Supplemental Fig. S1C) and did not show specificity for HOTAIR. These results are consistent with recent studies that revealed the promiscuous binding of PRC2 to numerous long RNA molecules (Davidovich et al. 2013; Kaneko et al. 2013). We therefore reasoned that there is likely an unidentified protein that interacts specifically with HOTAIR RNA to dictate its activity at target genes.

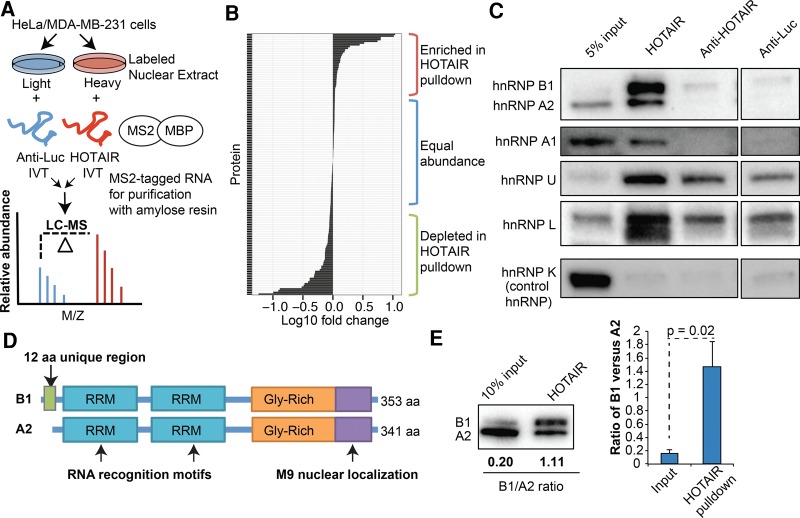

FIGURE 1.

SILAC mass spectrometry identifies proteins that specifically interact with HOTAIR. (A) In vitro transcripts were 3′ tagged with the MS2 RNA aptamer, incubated with labeled nuclear extracts, and recovered via the fusion protein MS2-MBP bound to amylose resin. Proteins stably associated with the transcripts were combined and subjected to LC/MS. (B) The enrichment of proteins recovered from HeLa nuclear extracts in the HOTAIR versus anti-Luc samples were calculated using MaxQuant. Ratios of all identified proteins were plotted. (C) Western blot validation of HOTAIR-interacting proteins in HeLa nuclear extracts. In vitro transcripts for anti-Luc and an antisense HOTAIR sequence were used as negative controls (all lanes from same blot). hnRNP K was used as a negative control protein. (D) Schematic of the A2 and B1 proteins, which differ only by the unique B1 N-terminal domain encoded by exon 2. (E) The enrichment of B1 versus A2 in HOTAIR RNA pulldowns from HeLa nuclear extracts was analyzed by Western blot. The graph depicts the mean ± SD ratio of B1 versus A2 (n = 3, two-tailed t-test).

Quantitative mass spectrometry identifies new specific HOTAIR–protein interactions

To identify new interaction partners of HOTAIR that may govern its activity, we performed an unbiased comparative mass spectrometry analysis of all stably associated proteins in the RNA pulldown experiment (Fig. 1A). We generated nuclear extracts from HeLa and MDA-MB-231 cells after performing stable isotope labeling of amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) (Ong et al. 2002). By quantitatively comparing the abundance of proteins associated with HOTAIR or a lncRNA control, we identified proteins that interact with HOTAIR and do not show indiscriminate binding to an abundant RNA (Fig. 1B). Multiple proteins were reproducibly enriched in the HOTAIR pulldown across mass spectrometry experiments in HeLa and MDA-MB-231 cells (Supplemental Table S1), including a number of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) (Supplemental Fig. S1D). We validated the interactions with HOTAIR via Western analysis after RNA pulldown using two control lncRNAs: the anti-Luc in vitro transcript in addition to a tagged antisense version of the HOTAIR transcript. The most specifically enriched interaction observed was between HOTAIR and the hnRNP A2/B1 protein isoforms (Fig. 1C). Western analysis also validated the putative interactions between HOTAIR and hnRNP A1, U, and L, though the enrichment and/or specificity was less pronounced compared to A2/B1. HOTAIR did not interact with hnRNP K, which has previously been shown to interact with other lncRNAs that regulate chromatin (Huarte et al. 2010; Chu et al. 2015) and is highly abundant in the nuclear extracts used. Therefore, the quantitative in vitro RNA pulldown strategy successfully identified a novel candidate protein that can selectively discriminate HOTAIR from similar RNA transcripts.

hnRNP A2/B1 interacts with the HOTAIR lncRNA

We focused our efforts on the interaction between the HOTAIR RNA and hnRNP A2/B1 proteins. The two protein isoforms generated by the HNRNPA2B1 gene, hnRNP A2 and hnRNP B1, are regulators of mRNA processing and splicing (Mayeda et al. 1994; Weighardt et al. 1996). Recently, A2/B1 have also been implicated in transcriptional repression via interaction with the immune response-up-regulated lincRNA-Cox2 (Carpenter et al. 2013), although the mechanism is not well understood. B1 differs from its A2 isoform solely by the inclusion of an exon encoding twelve amino acids at the N-terminus (Fig. 1D; Burd et al. 1989). The A2 isoform is more abundant in most tissues, but the division of labor between the two isoforms is poorly understood (Kamma et al. 1999). In HeLa cells, B1 is the minor isoform, yet surprisingly we found that the B1 isoform has a distinct preference for the HOTAIR RNA compared with A2 (Fig. 1E). Western analysis using an antibody raised to the shared portion of A2 and B1 demonstrated the ratio of B1 versus A2 is significantly increased in the HOTAIR pulldowns compared to the HeLa input cell lysates (Fig. 1E, two-tailed t-test, P = 0.02, n = 3). Additional experiments performed in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer and LOUCY acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells also confirmed A2/B1 association with HOTAIR in multiple cell types (Supplemental Fig. S1E). We next asked which portion of HOTAIR is required for the interaction with the A2/B1 proteins. Previous work has demonstrated that the catalytic component of PRC2, EZH2, binds to the first 300 nt of HOTAIR and the LSD1 histone demethylase binds to the 3′ end (Tsai et al. 2010; Wu et al. 2013). When we tested the ability of two truncated MS2-tagged HOTAIR in vitro transcripts to recover A2/B1, we observed the greatest hnRNP A2/B1 enrichment with full-length HOTAIR transcript (Supplemental Fig. S1F). Additionally, a 3′ 360-2148 HOTAIR transcript recovered more hnRNP A2/B1 than the short 5′ 1-360 HOTAIR transcript. These results suggest that A2/B1 interact with multiple regions of the HOTAIR primary sequence and/or require the region around nucleotide position 360 in HOTAIR, and that the PRC2 binding site of HOTAIR is insufficient for stable A2/B1 association.

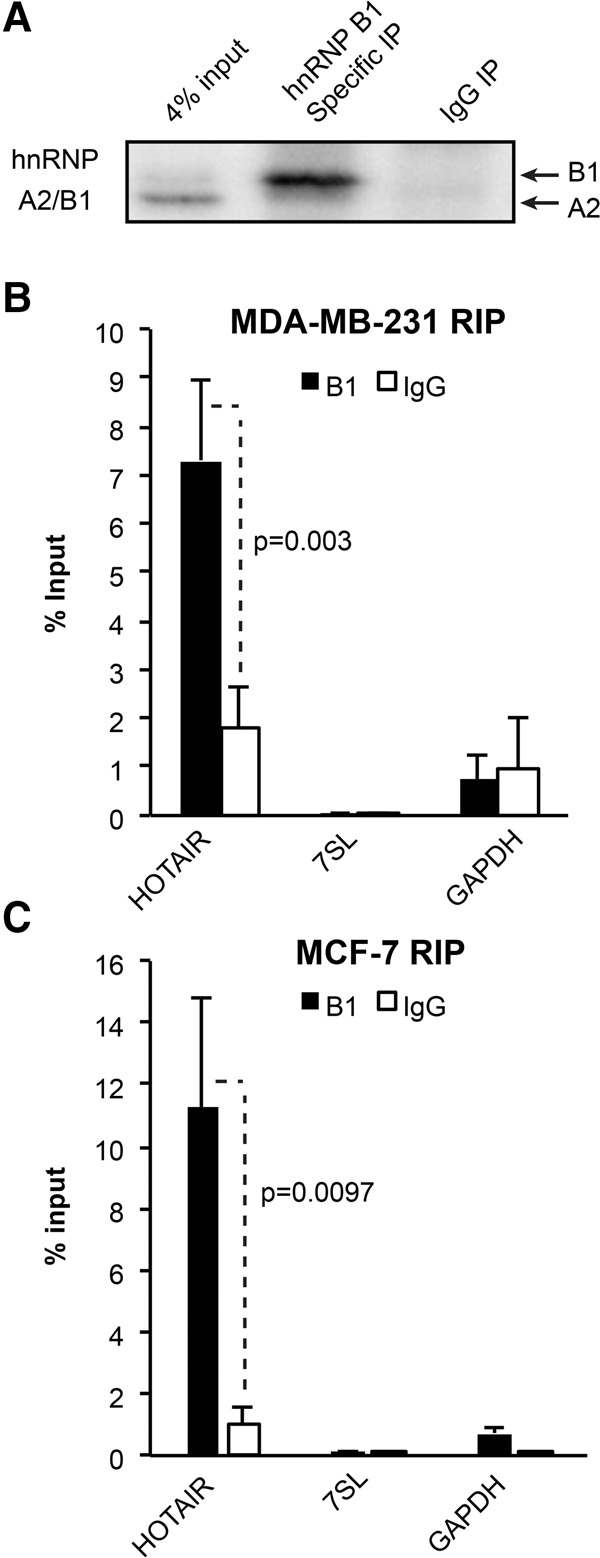

hnRNP A2/B1 and HOTAIR interact in vivo

To expand our in vitro work to a more physiological context, we asked whether hnRNP A2/B1 and HOTAIR interact in MDA-MB-231 cells. Overexpression of HOTAIR has previously been implicated in driving metastasis in this cell line (Gupta et al. 2010). Overexpression of the lncRNA is necessary for cell lines to achieve the levels of HOTAIR observed in breast cancer patient samples, which express much higher levels of HOTAIR than observed in breast cancer cell lines (Gupta et al. 2010). We therefore generated MDA-MB-231 cells that stably overexpress HOTAIR cDNA or the anti-Luc control. RT-qPCR indicated that HOTAIR was overexpressed ∼150× relative to endogenous HOTAIR, which is expressed at very low levels in this cell line (Supplemental Fig. S2A). We next performed native RNA immunoprecipitations (RIPs) of the hnRNP A2 and B1 proteins using an antibody specific to the B1 isoform and an antibody that recognizes both proteins. After confirming protein IP via Western blot analysis (Fig. 2A), we used qRT-PCR to assess the recovery of RNAs from the A2/B1 IPs versus IgG antibody control RIPs. We found that the B1 IP was significantly enriched for the HOTAIR RNA versus the IgG control IP (P = 0.003, two-tailed t-test, n = 4, Fig. 2B). As a control, we examined the recovery of the abundant RNAs 7SL and GAPDH, which did not show significant association with hnRNP B1 (P > 0.05, two-tailed t-test, B1 versus IgG, n = 4, Fig. 2B). When we immunoprecipitated with the shared A2/B1 antibody, we again found strong association of A2/B1 with HOTAIR and minimal association with abundant control RNAs (Supplemental Fig. S2B). In MDA-MB-231 cells that overexpress the anti-Luc control lncRNA, immunoprecipitation of hnRNP B1 did not recover substantial amounts of anti-Luc RNA (Supplemental Fig. S2C). We next expanded these studies to MCF-7 breast cancer cells, which express ∼12× more endogenous HOTAIR than MDA-MB-231 cells (Supplemental Fig. S2D). We found that immunoprecipitation of B1 led to the significant recovery of endogenous HOTAIR (P = 0.0097, two-tailed t-test versus IgG, n = 4), and minimal recovery of the GAPDH and 7SL control RNAs (Fig. 2C). The association of hnRNP A2 and B1 with HOTAIR in native immunopurified complexes is consistent with a cross-linking immunoprecipitation high-throughput sequencing (CLIP-seq) study in 293T cells that included IP using the A2/B1 antibody (Huelga et al. 2012). Two peaks of HOTAIR RNA tags occur in the A2/B1 CLIP, both in the last exon, confirming the direct interaction of either A2 or B1 with HOTAIR in vivo (Supplemental Fig. S2E).

FIGURE 2.

RNA immunoprecipitation of hnRNP B1 recovers HOTAIR. (A) Western analysis demonstrating isolation of the B1 isoform and not the A2 isoform by B1-specific antibody in MDA-MB-231 cells. (B) Recovery of HOTAIR, 7SL, and GAPDH RNA was assessed by RT-qPCR following RIP of hnRNP B1 versus an IgG control in HOTAIR-overexpressing MDA-MB-231 cells. The graph depicts the average recovery ± SD (two-tailed t-test, n = 4). (C) Recovery of HOTAIR, 7SL, and GAPDH RNA was assessed by RT-qPCR following RIP of hnRNP B1 versus an IgG control in MCF-7 cells expressing only endogenous HOTAIR. The graph depicts the average recovery ± SD (two-tailed t-test, n = 4).

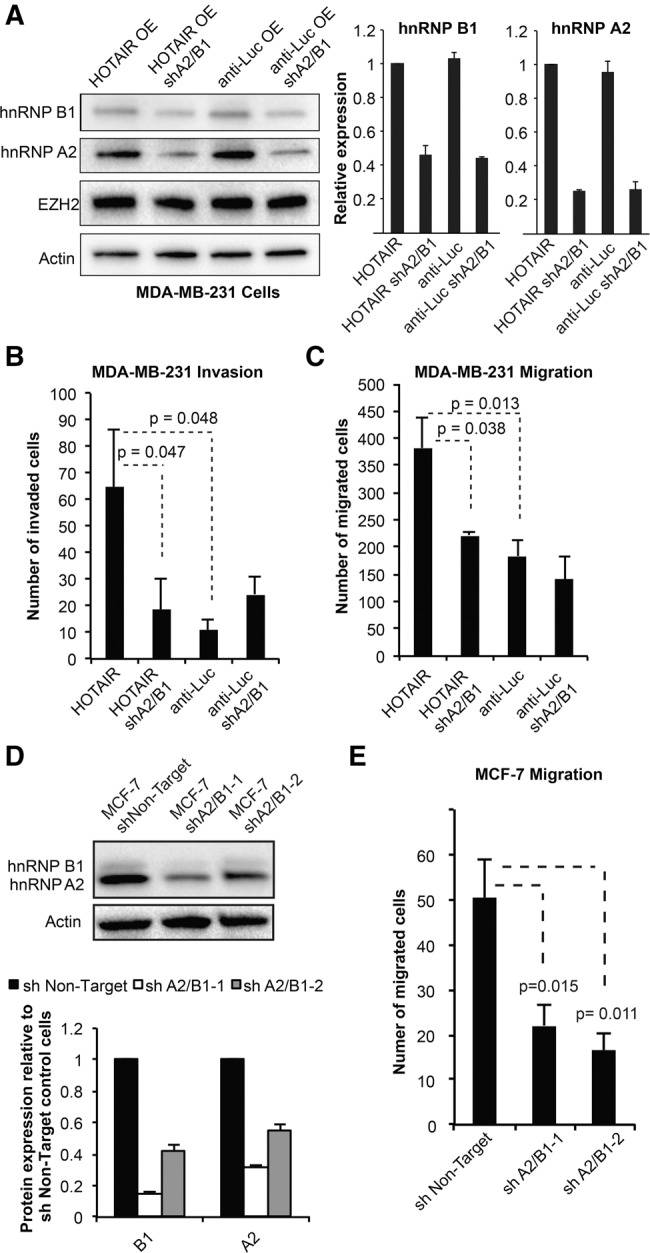

hnRNP A2/B1 is required for HOTAIR-induced invasion of breast cancer cells

Because HOTAIR expression drives metastasis in MDA-MB-231 cells (Gupta et al. 2010), we next investigated the dependence of metastatic potential on the A2/B1-HOTAIR interaction. We generated MDA-MB-231 cells that overexpress HOTAIR or the anti-Luc control and are knocked down for hnRNP A2/B1. Gene expression analysis via RT-qPCR confirmed that A2/B1 knockdown does not affect HOTAIR or anti-Luc transgene expression (Supplemental Fig. S3A). Western analysis demonstrated partial knockdown of both the A2 and B1 proteins, with an ∼75% decrease in A2 and a 60% decrease in B1 (Fig. 3A). Notably, more complete silencing of A2/B1 was initially achieved; however, protein suppression yielded a negative selective pressure on the cells, and thus only partial knockdown could be stably maintained. Previous work has demonstrated that overexpression of HOTAIR increases the invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells through a matrix that mimics the basement membrane of the epithelium (Gupta et al. 2010). We confirmed that overexpression of HOTAIR led to a significant increase in invasion compared to the anti-Luc control overexpression cells in 6-h assays performed using cell culture inserts with 8-µm pores coated with Matrigel extracellular matrix (Fig. 3B, two-tailed t-test, n = 3; representative images shown in Supplemental Fig. S3B). As an additional control, we also demonstrated that anti-Luc overexpression did not affect the invasion of unmodified MDA-MB-231 cells (Supplemental Fig. S3C).

FIGURE 3.

hnRNP A2/B1 is required for HOTAIR-mediated migration and invasion. (A) Western analysis confirms the knockdown of A2 and B1 in MDA-MB-231. The graphs show the quantification of knockdown from two replicates, each normalized using the loading control. (B) The invasion of MDA-MB-231 cells through Matrigel was quantified after 6 h using three biological replicates for each cell line. For each replicate, cells that invaded the Matrigel and through the chamber pores were counted from six 10× fields using the ImageJ software. The graphs show the average ± SD across three replicate experiments (two-tailed t-test used to calculate P-values). Representative images of invasion are supplied in Supplemental Figure S3B. (C) The migration of MDA-MB-231 cells through 8-µm pores was quantified after 6 h. The graph shows the average migrated cells ± SD (two-tailed t-test used to calculate P-values, n = 3). (D) Western blot confirms knockdown of A2 and B1 in MCF-7 cells (shA2B1-1 was used for knockdowns in MDA-MB-231 cells). Actin was used as a loading control. The graph depicts Western blot quantification of the average knockdown from two replicates ± SD. (E) Migration of MCF-7 cells through 8-µm pores was quantified after 6 h, using three biological replicates for each cell line. The graph shows the average migrated cells ± SD (P-values derived from two-tailed t-test versus shNon-Target control, n = 3).

To determine whether the hnRNP A2/B1 proteins are required for HOTAIR-mediated invasion, we performed invasion assays on MDA-MB-231 ± hnRNP A2/B1 knockdown and with either HOTAIR or anti-Luc overexpression. We found that suppression of hnRNP A2/B1 in the HOTAIR overexpression line reduced invasion to similar levels as observed in the anti-Luc overexpression lines with and without hnRNP A2/B1 knockdown (P > 0.05, two-tailed t-test, n = 3, Fig. 3B, representative images in Supplemental Fig. S3B). Similar results were seen in migration assays, which demonstrated a significant decrease in migration with hnRNP A2/B1 knockdown in a HOTAIR-dependent manner (Fig. 3C, two-tailed t-test, n = 3). To ensure the changes in invasion and migration were not driven by altered proliferation, we quantitatively monitored the growth of all four cell lines. We found no difference in cell growth at the 6-h time point used for the invasion and migration assays, and observed a small but significant decrease in proliferation in the hnRNP A2/B1 knockdown lines at 53 and 94 h (Supplemental Fig. S3D). Finally, to further confirm the importance of hnRNP A2/B1 across multiple cell lines, we generated MCF-7 cells with stable hnRNP A2/B1 knockdown (Fig. 3D). Previous work has shown that MCF-7 cells express a substantial amount of endogenous HOTAIR and that knockdown of HOTAIR decreases invasion (Gupta et al. 2010). We found that partial suppression of hnRNPA2B1 with two different shRNAs both significantly decreased the migration of MCF-7 cells (Fig. 3E, two-tailed t-test, P < 0.02 for both shRNAs versus nontargeting control, n = 3). Therefore, the A2 and B1 proteins are important for the invasion and migration of breast cancer cells.

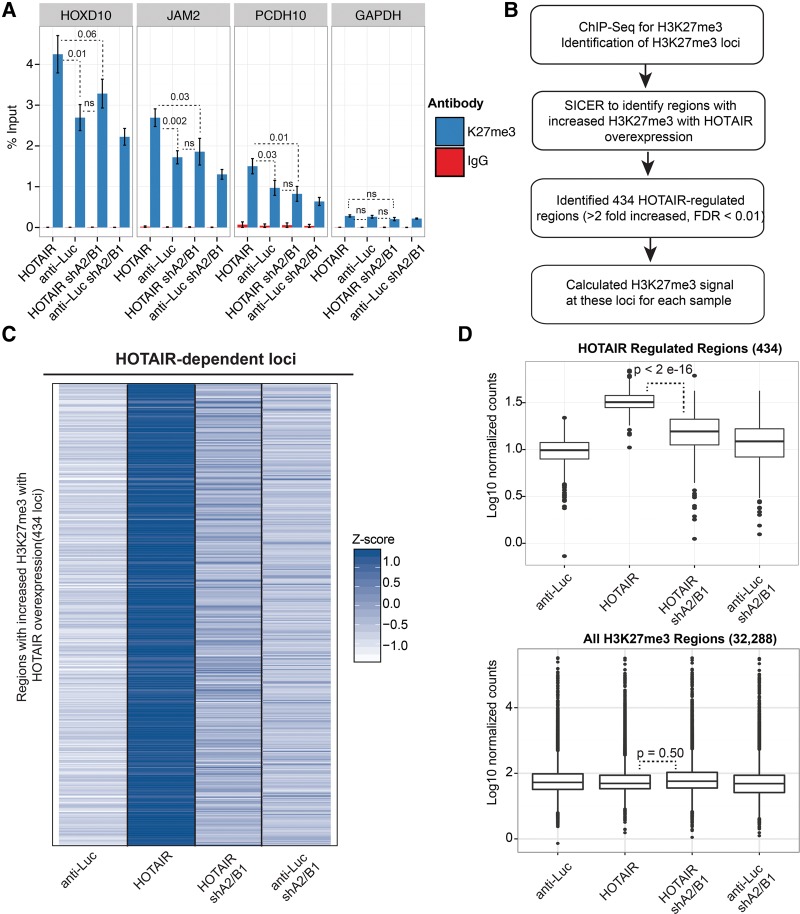

hnRNP A2/B1 regulates H3K27me3 at HOTAIR-target genes

To understand the mechanism by which A2/B1 knockdown disrupts HOTAIR function, we asked whether A2/B1 is necessary for HOTAIR-directed PRC2 activity. To determine the importance of A2/B1 in generating the H3K27me3 silencing mark, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation in MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressing HOTAIR or anti-Luc and ±A2/B1 knockdown. We first assessed H3K27me3 enrichment at three previously identified HOTAIR target genes in MDA-MB-231 cells (Gupta et al. 2010): HOXD10, Junctional Adhesion Molecule 2 (JAM2), and Protocadherin 10 (PCDH10), in addition to the control GAPDH locus. We observed that overexpression of HOTAIR resulted in modest but significant increases in H3K27me3 at these targets compared to control cells overexpressing anti-Luc (Fig. 4A, n = 6, one-tailed t-test, P < 0.05 for all three targets). Knockdown of hnRNP A2/B1 in cells overexpressing HOTAIR led to a significant reduction in H3K27me3 at the PCDH10 and JAM2 loci, and yielded H3K27me3 levels not significantly different than the control anti-Luc cell line at all three HOTAIR targets (Fig. 4A, P > 0.05, one-tailed test, n = 6). We did not observe HOTAIR-induced H3K27me3 changes at the GAPDH negative control locus (Fig. 4A).

FIGURE 4.

hnRNP A2/B1 regulates HOTAIR-dependent H3K27me3. (A) ChIP of H3K27me3 or IgG at HOTAIR target genes. qPCR was used to assess the enrichment of HOTAIR targets. GAPDH was used as a control locus. The bar graphs depict the average % input recovered ± SEM (n = 6 for the H3K27me3 antibody; n = 2 for IgG; P-value from one-tailed t-tests versus anti-Luc expressing cells. (ns) Not significant changes (P > 0.05). (B) H3K27me3 ChIP-seq was performed with each of the four MDA-MB-231 cell lines (n = 2 for each cell line). (C) Heatmap depicts the normalized signal accumulation at 434 regions at which HOTAIR increased H3K27me3 (greater than twofold increased, FDR < 0.01). The heatmap is normalized per row by calculating a Z-score for each sample. (D) Boxplots depict the average H3K27me3 signal accumulation at the 434 HOTAIR regulated loci (top) and at all loci that showed H3K27me3 above background in any of the four cell lines (bottom). The boxplots demonstrate that HOTAIR-mediated increases in H3K27me3 are restricted to a subset of loci and that HOTAIR shA2/B1 cells do not show global decreases in H3K27me3. P-values were derived from two-tailed t-tests performed between the HOTAIR and HOTAIR sh A2/B1 samples, using the normalized accumulation of H3K27me3 at each locus.

The modest effect of HOTAIR on the H3K27me3 silencing mark of previously identified target loci prompted us to more broadly assess the effects of A2/B1 on HOTAIR-mediated H3K27me3. We performed next-generation sequencing of the H3K27me3 ChIP samples (n = 2 for each of the four cell lines). We used the program SICER to identify islands of H3K27me3 enrichment, and performed differential analysis of the H3K27me3 levels of cells expressing anti-Luc versus HOTAIR lncRNA (Fig. 4B). We identified a list of 434 regions significantly increased in H3K27me3 with HOTAIR versus anti-Luc overexpression (using a twofold enrichment cutoff and FDR < 0.01). The regions we identified did not include the target genes we analyzed in Figure 4A; however, this genome-wide result is consistent with the large and relatively nonoverlapping repertoires of targets for HOTAIR that have been identified in multiple previous studies (Gupta et al. 2010; Tsai et al. 2010; Chu et al. 2011; Ge et al. 2013; Heubach et al. 2015). This may suggest that HOTAIR effects on H3K27me3 levels across the genome have a degree of heterogeneity that reflect a complex mechanism for PRC2 activity such as the model we propose (see Discussion).

To determine whether A2/B1 is required for HOTAIR-mediated H3K27me3 enrichment, we compared the read pileup (normalized for total number of reads) at these HOTAR-regulated regions in the HOTAIR and anti-Luc A2/B1 knockdown lines (Fig. 4C,D). Of the 434 HOTAIR-regulated H3K27me3 loci, 366 of these (84%) were significantly decreased in H3K27me3 in the HOTAIR shA2/B1 versus HOTAIR overexpression cells (SICER differential analysis, FDR < 0.01) (Fig. 4C, list of annotated regions in Supplemental Table S2). Two examples of this trend are depicted in Supplemental Figure S4, which displays an increase in H3K27me3 at the FOXB1 and HSF5 genes in HOTAIR overexpression cells that is disrupted by A2/B1 knockdown across two biological replicates. As a control to verify that HOTAIR and A2/B1 do not globally affect H3K27me3 levels, we plotted the average H3K27me3 signal at all loci that showed H3K27me3 enrichment above background in any of the samples (n = 32,288 loci) (Fig. 4D). These data demonstrate that HOTAIR regulates the H3K27me3 of only a subset of loci, and that the effects of A2/B1 knockdown on these HOTAIR-enriched regions is not a result of global H3K27me3 depletion in the HOTAIR shA2/B1 sample. When we examine the H3K27me3 of regions that are not regulated by HOTAIR (31,854 regions that do not meet a twofold, FDR < 0.01 HOTAIR versus anti-Luc cutoff), we find only 4% of these regions twofold decreased in H3K27me3 in the HOTAIR shA2/B1 versus HOTAIR cells. This fraction of loci is significantly less than the 48% of HOTAIR regulated loci that show significant, twofold decreases in H3K27me3 in the HOTAIR shA2/B1 versus HOTAIR cells (χ2 test, P < 0.0001). Together, these results demonstrate that hnRNP A2/B1 is required for HOTAIR-regulated repressive chromatin marks at specific loci in the genome.

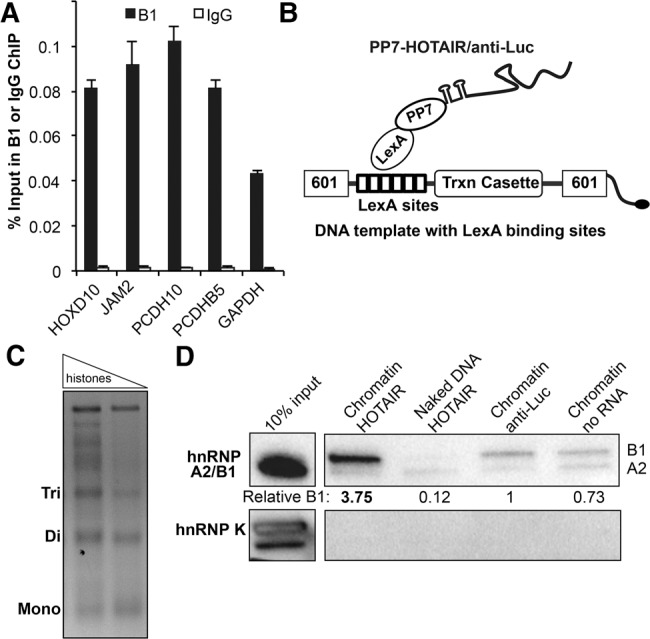

hnRNP A2/B1 are broadly recruited to chromatin

The impact of A2/B1 on chromatin modifications raises the question of how proteins primarily implicated in mRNA processing affect histone modifications. We hypothesized that A2/B1 may interact with HOTAIR on chromatin to modulate PRC2 activity. To determine whether hnRNP A2/B1 bind the genomic loci of HOTAIR targets, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation on formaldehyde cross-linked MDA-MB-231 cells. Using an isoform-specific antibody for B1, we found significant enrichment of B1 versus the IgG control at multiple HOTAIR targets, including HOXD10, JAM2, PCDH10, and PCDHB5. However, B1 enrichment was also observed at the GAPDH control locus, suggesting broad B1:chromatin interaction (Fig. 5A). To determine whether HOTAIR expression affects B1 localization, we also performed ChIP experiments in MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressing either HOTAIR or the anti-Luc control lncRNA. B1 demonstrated nearly identical recruitment to HOTAIR targets in both cell lines, which indicates that HOTAIR overexpression does not direct B1 localization to chromatin (Supplemental Fig. S5A). Additionally, to determine whether RNA is required for B1 interaction with chromatin, we repeated our B1 ChIP experiments in MDA-MB-231 cell lysates ± RNase treatment (Supplemental Fig. S5B). We found that RNase treatment led to improved B1 enrichment at HOTAIR targets and at the GAPDH control locus, potentially by increasing the accessibility of the antibody to its epitope (the B1-specific exon). These results also suggest that B1 can be crosslinked directly to chromatin after recruitment. We also performed chromatin immunoprecipitation with an antibody that binds both A2 and B1, which again showed recruitment of the proteins to both HOTAIR targets and actively transcribed loci such as GAPDH (Supplemental Fig. S5C). These results suggest that A2/B1 have the capacity to associate stably on chromatin, but that direct recognition of DNA sequence is unlikely to be sufficient to dictate A2/B1 regulation of H3K27 methylation at HOTAIR targets.

FIGURE 5.

HnRNP B1 localizes to chromatin and interacts preferentially with HOTAIR. (A) ChIP of B1 at HOTAIR-target genes and the GAPDH control with an isoform-specific antibody. IgG was used as a negative control antibody. Graphs show the average % input recovered ± SD (n = 2). (B) Biotinylated DNA template for chromatin reconstitution. Six tandem LexA binding sites allow RNA tethering of transcripts to chromatin or naked DNA. (C) Reconstituted human chromatin was produced by enzymatic assembly and confirmed by micrococcal nuclease digestion. (D) Naked DNA or chromatin with tethered HOTAIR or anti-Luc in vitro transcripts were incubated with nuclear extract from HeLa cells. Western analysis using the pan-A2/B1 antibody was used to determine the level of B1 and A2 recruitment to the chromatin and naked DNA substrates. hnRNP K is an abundant hnRNP protein used as a negative control. The efficiency of RNA tethering and additional results from MDA-MB-231 cells are provided in Supplemental Figure S5D,E.

In vitro chromatin reconstitution of A2/B1–HOTAIR interaction

To more directly examine the interactions of A2/B1 and HOTAIR on chromatin, we used a reconstituted system. The mechanism by which HOTAIR associates with the genome is unclear; therefore, we artificially tethered HOTAIR to a chromatin substrate to place HOTAIR in a chromatin context. We generated nucleosome arrays containing human histone octamers as previously described and confirmed chromatin reconstitution by micrococcal nuclease digestion. (Fig. 5B,C; Luger et al. 1999; An and Roeder 2004; Vary et al. 2004). The DNA template contained six LexA binding sites, which can be bound by a LexA protein fused to an RNA-binding protein (Fig. 5B). After testing multiple RNA binding proteins, the PP7 phage protein was determined to be the most efficient at tethering HOTAIR RNA, tagged with a tandem PP7 and tobramycin-binding aptamer (termed the RAT tag [Hogg and Collins 2007]), to DNA and chromatin (Supplemental Fig. S5D). The DNA template is biotinylated, allowing the chromatin substrate to be purified with magnetic streptavidin beads.

To assay the recruitment of proteins to the HOTAIR-chromatin assembly, we first incubated tagged HOTAIR in vitro transcript with chromatin bound by the recombinant LexA-PP7 fusion protein. We next added the HOTAIR-chromatin assembly to nuclear extracts from HeLa cells and, following streptavidin purification, assessed protein and RNA recovery (Fig. 5D; Supplemental Fig. S5D). As controls, we performed parallel experiments with a RAT-tagged anti-Luc in vitro transcript, and with the naked DNA template that does not contain histones, but is bound by RAT-tagged HOTAIR. We found that, in the absence of tethered RNA, B1 bound to chromatin (Fig. 5D), which is consistent with our observation of B1 enrichment at multiple genomic loci by ChIP, even in the absence of HOTAIR overexpression. Importantly, we also observed that chromatin with tethered HOTAIR led to a nearly fourfold enrichment of hnRNP B1, compared to tethered anti-Luc RNA. We observed greater enrichment of B1 than A2 on chromatin templates with and without HOTAIR, which again suggests B1 and A2 have differing substrate affinities. We confirmed these results with nuclear extracts from the MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line, which also demonstrated B1 recruitment to chromatin in a HOTAIR-dependent manner (Supplemental Fig. S5E). Taken together, our results show that B1 can specifically engage HOTAIR on chromatin and chromatin context clearly promotes B1–HOTAIR interaction. However, this chromatin context was artificially induced by tethered HOTAIR. These results raise the question: How do B1 and HOTAIR normally engage chromatin? We hypothesized that the ability of this family of proteins to bind multiple nucleic acid molecules simultaneously (Ding et al. 1999) may contribute to the productive engagement of HOTAIR for the regulation of chromatin.

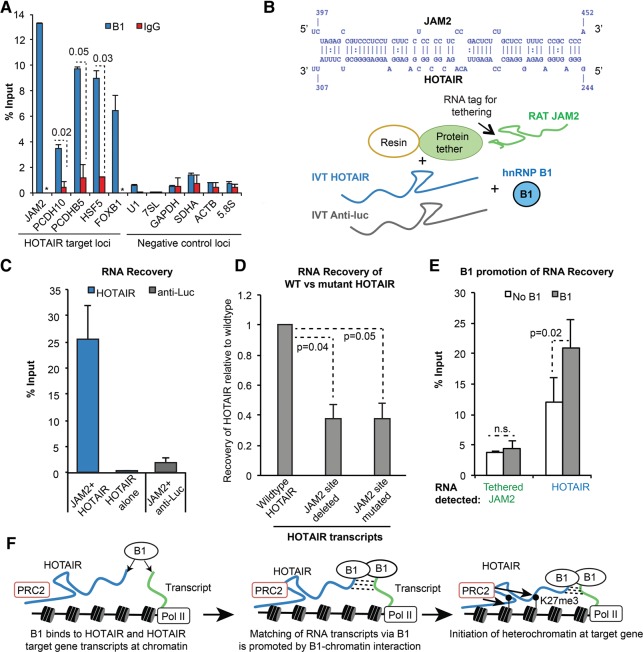

hnRNP B1 binds the RNA transcripts of HOTAIR targets

hnRNP A2/B1 are splicing regulators that can bind nascent mRNA precursors cotranscriptionally (Martinez-Contreras et al. 2007). Based on this function, we asked whether B1 can bind the RNA transcripts of HOTAIR target genes. We found that in the same RNA-IP experiments that detected HOTAIR, the B1 protein also recovers significant amounts of the HOTAIR target RNAs JAM2, PCDH10, and PCDHB5 (Fig. 6A, two-tailed t-test, B1 versus IgG, n = 2). We also found that B1 bound to the HSF5 and FOXB1 RNA transcripts, two genes we identified as HOTAIR H3K27me3 targets in our ChIP-seq experiments. B1 IP did not show enrichment for abundant cellular RNAs (U1, 7SL, GAPDH, SDHA, ACTB, and 5.8S). In contrast, RNA-IP using a pan-A2/B1 antibody recovered HOTAIR targets, but also showed enrichment for multiple control RNAs including GAPDH, ACTB, and 5.8S that B1 did not bind (Supplemental Fig. S6A). These results suggest that B1 may discriminately bind a subset of RNA transcripts. Our data are consistent with the previous A2/B1 CLIP-seq data (Huelga et al. 2012), which demonstrate that A2/B1 interact with the 5′ end of the HOTAIR targets PCDH10, JAM2, and HOXD10 (Supplemental Fig. S6B).

FIGURE 6.

hnRNP B1 binds to the RNA transcripts of HOTAIR target genes and enhances HOTAIR–RNA interaction. (A) Native RNA immunoprecipitation of B1 versus IgG in MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressing HOTAIR. RT-qPCR was used to assess the enrichment of HOTAIR target RNA transcripts versus a panel of control RNAs. Graphs depict the average percent input recovered ±SD (P-value from two-tailed t-test versus IgG, n = 2). (*) Indicates IgG samples in which no signal could be detected by qRT-PCR. HOXD10 RNA was not detectable in the input samples. (B) RNA–RNA interaction between HOTAIR and JAM2 predicted by IntaRNA (Wright et al. 2014). Schematic of RNA–RNA interaction experiment is shown below. RAT-tagged JAM2 was incubated with HOTAIR or an anti-Luc control RNA in the presence and absence of B1, and then purified via a protein tether. (C) The association of HOTAIR and anti-Luc RNA with JAM2 was quantified by RT-qPCR (n = 3, graphs depict mean ±SD). “HOTAIR alone” indicates an assay with no JAM2 RNA. (D) The predicted JAM2 interaction region within the HOTAIR full-length transcript was deleted or mutated, and HOTAIR association with JAM2 was assessed by RT-qPCR. The graph depicts the average recovery ±SD of the two mutant transcripts relative to the wild-type HOTAIR sequence (n = 3, P-values represent two-tailed t-tests of nanograms of WT versus mutated HOTAIR recovered). HOTAIR recovery was normalized to the recovery of the JAM2 transcript (see Materials and Methods for more detail). (E) The recovery of JAM2 and HOTAIR in the absence and presence of the B1 protein was assessed by RT-qPCR. Graphs depict the mean ± SD from four biological replicates (P-value from two-tailed t-test). (F) A model for B1 as a matchmaker for HOTAIR and the transcripts of HOTAIR target genes, promoting subsequent PRC2 activity.

HOTAIR can associate directly with target gene RNA

To begin to address whether HOTAIR can be matched with its targets via intermolecular RNA pairing, we used the RNA–RNA prediction program IntaRNA (Wright et al. 2014) to query HOTAIR versus the ∼1000-nt sequence surrounding the A2/B1 CLIP-seq peak in the 5′ end of JAM2 (Supplemental Fig. S6C). This analysis identified a 48-bp interaction region between HOTAIR and its target (Fig. 6B), which also overlaps the JAM2 CLIP-seq peak. We next performed in vitro RNA–RNA interaction assays (Fig. 6B) to determine whether the JAM2 region could interact directly with HOTAIR in the presence or absence of purified hnRNP B1. We found that an RNA transcript of the JAM2 interaction region, tethered by the RNA RAT tag to resin, was able to recover HOTAIR greater than eightfold more efficiently than the anti-Luc control RNA (Fig. 6C). To assess whether the predicted JAM2:HOTAIR interaction region was important for this association, we generated two mutated full-length HOTAIR transcripts: a transcript with the JAM2 binding site deleted, and a HOTAIR transcript in which each base of the JAM2 interaction region was mutated to its complementary base. When we assessed the JAM2 recovery of mutated versus wild-type HOTAIR, we found that both deletion and mutation of the predicted interaction region led to a decrease in HOTAIR recovery (Fig. 6D, n = 3, two-tailed t-test between WT and mutant HOTAIR IVT recovered). We also found that when we introduced purified, recombinant hnRNP B1, JAM2 was able to recover increased amounts of HOTAIR (Fig. 6E, two-tailed t-test, P = 0.02, n = 4). These results demonstrate that HOTAIR can specifically interact with the RNA of its target gene and raise the possibility that B1 participates in the RNA–RNA interaction between the lncRNA and RNA target (Fig. 6F).

DISCUSSION

Our studies have identified a new interaction partner of the HOTAIR lncRNA and determined its importance in HOTAIR-mediated heterochromatin formation. Our data support a model where RNA matchmaking between HOTAIR and target gene transcripts occurs on chromatin and is facilitated by the hnRNP B1 isoform, which binds to HOTAIR and target gene RNAs preferentially.

Implications for hnRNP-induced lncRNA–mRNA matchmaking

The fact that hnRNP B1 engages both HOTAIR and the RNA transcripts of target genes suggests that B1 may serve as a specificity factor for the lncRNA and its genomic targets. The hnRNP A/B proteins have been shown to bind multiple sites within a single RNA molecule to influence alternative splicing (Martinez-Contreras et al. 2006). Previous work has shown that the closely related family member hnRNP A1 possesses intermolecular RNA–RNA annealing activity, and thus can serve as a matchmaker between multiple RNAs (Munroe and Dong 1992). Our data support a similar model where B1 preferentially binds to both HOTAIR and target RNA to match the two on chromatin for PRC2-mediated repression (Fig. 6F). We provide further evidence for direct RNA–RNA base-pairing by demonstrating that the RNA-binding site for A2/B1 in JAM2 has extensive pairing capability with HOTAIR and can directly associate with the lncRNA.

Recent work has shown that lncRNAs and mRNAs can interact (Kretz et al. 2013) in the cytoplasm, and in some cases through RNA–RNA interactions with nascent transcripts on chromatin (Engreitz et al. 2014; Lee et al. 2015), yet the mechanism behind these associations is in most cases unclear. Our work suggests that B1 may serve as an adaptor between a lncRNA and its specific targets in the genome. Our data are consistent either with RNA matchmaking as a means to target HOTAIR and/or to promote PRC2 activity on chromatin, perhaps by relieving the catalytic inhibition of PRC2 by RNA binding (Cifuentes-Rojas et al. 2014; Herzog et al. 2014; Kaneko et al. 2014b). Future work will be necessary to address these possibilities. Notably, the RNA matchmaking model suggests a mechanism for de novo gene silencing, where the product of active transcription is a requirement to eventually lead to transcriptional repression. This event would be an intermediate step of a mechanism in which the inhibitory activity of nascent RNA on PRC2 activity is relieved and H3K27me3 is established (Kaneko et al. 2014b). Additional factors then contribute to maintenance of PRC2 within established fHC, such as JARID2 (Kaneko et al. 2014a) and binding of PRC2 to pre-established H3K27me3 (Hansen et al. 2008; Margueron et al. 2009).

Proteomic analysis of the HOTAIR interactome

Our SILAC-based proteomic approach allowed us to discover lncRNA-associated proteins in a quantitative and unbiased manner. Because our technique uses an RNA aptamer tag, recovery of lncRNAs and associated proteins is independent of the accessibility of the RNA sequence, which is required for oligo capture approaches for RNA purification (Simon et al. 2011; Chu et al. 2012; Engreitz et al. 2013). HOTAIR features an elaborate secondary structure with multiple protein binding domains (Somarowthu et al. 2015). Therefore, purification via an RNA tag outside of these motifs avoids relying on the accessibility of these regions for RNP isolation. While we have focused our studies on HOTAIR, these techniques can be broadly applied to other lncRNAs in order to identify their repertoires of interacting proteins, as has previously been performed on both snRNA and viral RNAs (Hogg and Collins 2007; Lee et al. 2012). We expect that different lncRNAs will associate with unique cofactors, as evidenced by recent demonstrations of associations between hnRNP L and the lncRNA THRIL (Li et al. 2014); hnRNP K and lincRNA-p21 (Huarte et al. 2010); hnRNP I and the lncRNA-RoR (Zhang et al. 2013); and hnRNP U, hnRNP K, Spen/SHARP, and additional cohesion and chromatin remodelers with Xist (Hasegawa et al. 2010; Chu et al. 2015; McHugh et al. 2015; Minajigi et al. 2015). Together, these studies and our work support previously proposed models of hnRNP function that emphasized the capacity of hnRNPs for transcript selectivity, but also the ability of the proteins to scaffold both RNAs and protein to gain increased regulatory complexity in RNA metabolism (Weighardt et al. 1996; Dreyfuss et al. 2003).

Transcript-specific recruitment of the B1 isoform

The enrichment of B1 versus A2 in association with HOTAIR raises the question of how RNA specificity is achieved. Several binding motifs have been proposed for the hnRNP A2/B1 proteins: hnRNP A2/B1 preferentially bind the telomeric ssDNA repeat TTAGGG, in addition to the RNA UUAGGG motif (McKay and Cooke 1992). Recently, A2/B1 were found to bind a 19-mer AU-rich motif (Goodarzi et al. 2012), and also to bind N6-methyladenosine-modified (m6A) transcripts and affect microRNA processing (Alarcón et al. 2015). We analyzed recently published m6A CLIP data (Linder et al. 2015) that provides single-nucleotide resolution of the m6A modifications in the HEK293 transcriptome. No peaks of m6A enrichment were found within the HOTAIR transcript. However, multiple peaks of m6A enrichment were identified within the 5′ ends of PCDH10 and HOXD10 transcripts, two targets of HOTAIR, which suggests that the modification could play a role in hnRNPA2/B1 selection of specific RNA transcripts. Since hnRNP A2 and B1 are identical in their RNA recognition motifs, they have primarily been described as regulating the same targets, although the B1 isoform shows stronger affinity than A2 for telomeric DNA (Kamma et al. 2001). The unique 12-amino acid region of the B1 isoform may also confer structural changes that enable stronger interaction with HOTAIR. Although A2 and B1 have not been crystallized, studies of the tandem RNA-recognition motifs of hnRNP A1, which is highly homologous to that of A2/B1, showed binding to two anti-parallel strands of ssDNA (Ding et al. 1999). Therefore, our data suggest that B1-HOTAIR interaction requires multiple nucleotide recognition motifs within HOTAIR, which may allow B1 to preferentially bind to HOTAIR.

hnRNP B1 as a new regulator of HOTAIR

We have identified a new lncRNA–protein interaction that occurs preferentially on chromatin and may be a key event in dictating lncRNA-dependent fHC initiation. HnRNP B1, an isoform of a broadly acting family of proteins, interacts with HOTAIR to contribute to the regulation of gene silencing and metastatic potential in breast cancer cells. The B1 isoform is frequently overexpressed in breast, lung, and hepatocellular carcinomas, and can serve as an important diagnostic and prognostic parameter (Sueoka et al. 1999; Zhou et al. 2001; Zech et al. 2006; Cui et al. 2010). Our work reveals a key role for A2/B1 in HOTAIR-mediated heterochromatin formation that promotes cell invasion. B1 may facilitate action of HOTAIR at specific sites in the genome by serving as a matchmaker for RNA transcripts of HOTAIR target genes, leading to PRC2 activity. Therefore, our work reveals a B1-HOTAIR interaction that repurposes the hnRNP for targeted heterochromatin initiation, and in this context may serve as an important regulator of breast cancer metastasis. Our work has broad implications for lncRNA biology by providing evidence for a potential mechanism of lncRNA targeting that may extend to additional lncRNAs known to regulate the genome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

HeLa and MDA-MB-231 cells were maintained in DMEM and RPMI media (Gibco), respectively, with 10% FBS and Pen-Strep (Life Technologies). For SILAC experiments with HeLa cells, we used SILAC DMEM media (Gibco) supplemented with 10% dialyzed FBS (Gibco; Life Technologies), 4 mM glutamine, 0.339 mM L-Arginine HCL (Sigma), and 0.798 mM of either heavy (L-Lysine 2HCL [13C6, 15N2], Cambridge Isotopes) or normal lysine (L-Lysine 2HCL, Sigma). For MDA-MB-231 cells, we used SILAC RPMI media from Thermo supplemented with 10% dialyzed FBS (Gibco; Life Technologies), 1.16 mM L-Arginine, and 0.274 mM either normal L-Lysine 2HCL (Sigma) or heavy (L-Lysine 2HCL [13C6, 15N2], Cambridge Isotopes). Cells were grown in SILAC media for at least one week prior to nuclear extract preparation.

MDA-MB-231 cells overexpressing HOTAIR or anti-Luciferase were generated by retroviral transduction following the transfection of pBABE-puro constructs into 293 packaging cells that express the pCL-10A viral envelope. Selection was performed using 1 µg/µL puromycin (Sigma). Stable hnRNPA2B1 knockdown was performed by lentiviral infection of the MDA-MB-231 HOTAIR and anti-Luc expressing cells. Lentivirus was generated via FugeneHD (Promega) transfection of 293T cells with pVSVG, pCMV-delta R.8, and the pLKO.1-blasticidin shRNA constructs. shRNA for A2B1 included: #1 TRCN0000001059 and #2 TRCN0000001058. Cells were selected with 5 µg/mL blasticidin (Life Technologies). The nontargeting shRNA pLKO.1-blast-SCRAMBLE was obtained from Addgene (Catalog # 26701).

Plasmid construction

The spliced HOTAIR transcript (NR_003716.3) was synthesized by GenScript, and cloned into the pTRE3G vector (Clonetech). The 10× MS2 cassette was synthesized by Genewiz and inserted at the 3′ end of HOTAIR. An antisense transcript of the firefly luciferase gene (anti-Luc) was amplified from the pTRE3G-Luciferase plasmid (Clonetech), then cloned into the pTRE3G 10× MS2 vector in place of HOTAIR. The HOTAIR and anti-Luc sequences were also cloned into the pBABE-puro retroviral vector, in addition to a modified version of the pLPCX plasmid obtained from Addgene (#27549 from [Hogg and Collins 2007]) to generate RAT-tagged RNAs. Plasmids for the knockdown of hnRNPA2B1 were generated by cloning the shRNA (RNAi Consortium shRNA Library) from pLKO-1.puro into the pLKO-1.blast backbone (Addgene #26655). Human histone protein genes were synthesized and cloned into plasmids by GenScript. Untagged H2A, H2B, and H3.1 were cloned into pET3a. A codon-optimized H4 gene was synthesized with an N-terminal hexahistidine tag and TEV protease cleavage site. LexA-PP7 was cloned into pGEX-6P-1 (GE Healthcare). The hnRNP B1 ORF was synthesized by GenScript and then cloned into pGEX-6P-1.

In vitro transcription of RNA

PCR with the Phusion polymerase was used to add 5′ T7 promoter sequences and generate templates for in vitro transcription, using pTRE3G and pLPCX plasmids containing the anti-Luc and HOTAIR sequences. Primers are given in Supplemental Table S3. Following PCR cleanup with the E.Z.N.A. Cycle Pure Kit (Omega Biotek), in vitro transcription was performed using the T7 enzyme (NEB) for 4 h at 37°C. RNA was treated with DNase1 (Ambion) for 15 min, and RNA was purified with the RNeasy kit (QIAGEN).

Protein preparation

MS2-MBP was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified via amylose and heparin chromatography as previously described (Zhou and Reed 2003). Histone proteins were expressed individually in E. coli, purified, and assembled into octamers as previously described (Luger et al. 1999), with the exception of a Ni-NTA (QIAGEN) purification for His-TEV-H4 as previously described (Ruthenburg et al. 2011). N-terminal hexahistidine-tagged human histone chaperone Nap1 (NAP1L1) (plasmid courtesy of J. Nyborg and H. Scherman, Colorado State University) was expressed in E. coli and purified through Ni-NTA and HiTrap Q (GE Healthcare) chromatography, essentially as described for dNAP1 (Fyodorov and Kadonaga 2003). Isw1a complex was obtained from an IOC3-TAP yeast strain as previously described (Vary et al. 2004). LexA-PP7 was expressed and purified as an N-terminal fusion protein by standard glutathione–agarose resin (Thermo Fisher) chromatography and PreScission Protease cleavage. The Protein A-PP7 fusion protein was purified as previously described from E. coli after transformation with Addgene plasmid #27548 (Hogg and Collins 2007). Recombinant hnRNP B1 in pGEX-6P-1 was expressed in BL21(DE3) pLysS E. coli, and induced with 0.2 mM IPTG for 16 h at 16°C. The bacterial pellet was washed in PBS with 500 mM NaCl. Cells were lysed by sonication in urea purification buffer (700 mM NaCl, 5% Glycerol, 0.5 M Urea, 2% Triton X-100, 15 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF in PBS). Low concentration of urea was included to aid purification as described for the FUS RNA binding protein (Schwartz et al. 2013). Extracts were centrifuged at 32,000g for 30 min at 4°C. Soluble extract was subjected to affinity chromatography on glutathione–agarose resin (Thermo) according to manufacturer's instructions using wash buffer (500 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM Urea, 2% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF in PBS). Resin was mutated overnight at 4°C in Protease Cleavage buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7, 350 mM NaCl, 0.5M Urea, 0.5% Triton X-100, 5% Glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT) with PreScission Protease (GE Healthcare). Protein was eluted in Protease Cleavage buffer. Protein was dialyzed for 3 h in Dialysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7, 350 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 5% Glycerol, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT) to remove urea.

RNA pulldown experiments

Nuclear extracts were generated from HeLa and MDA-MB-231 cells as previously described (Zhou and Reed 2003). Three micrograms of in vitro transcribed RNA in 1× TE was heated to 90°C for 2 min, incubated on ice for 2 min, and then placed at RT for 15 min in RNA structure buffer at a final concentration of 10 mM Tris pH 7.4, 0.1 M KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, as previously described (Tsai et al. 2010). The RNA was then incubated with 100 µg of nuclear extract at 4°C in the presence of 40 U RNase inhibitor (Promega) in lysis buffer (10 mM Hepes 7.4, 150 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM PMSF, 10% glycerol with protease inhibitors [Roche]) (Lee et al. 2012). For each pulldown, 10 µg MS2-MBP was prebound to 20 µL of amylose resin (NEB) for 2 h at 4°C. The MS2-MBP amylose resin was then added to each IVT-Nuclear Extract sample, and incubated an additional 2 h at 4°C. Resin was washed 4× in wash buffer (20 mM Tris at pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM DTT), and then associated proteins were identified via mass spectrometry or Western blots.

Western blots

For Western analysis, proteins were resolved on Tris–Glycine gels, transferred to nitrocellulose or PVDF membranes (Millipore), and probed with the following antibodies: hnRNP A2/B1 (Novus NB120-6102), hnRNP K (Novus NBP2-24531), hnRNP A1 (Cell Signaling K350), hnRNP U (Abcam 180952), hnRNP L (Abcam 6106), β-actin (Thermo MA5-15739), EZH2 (Cell Signaling 3147), and α-tubulin (Santa Cruz sc-5286). Immobilon Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate from Millipore was used for detection using a BioRad ChemiDoc system. ImageJ was used to quantify each blot.

Mass spectrometry

Proteins were eluted from the amylose resin by boiling in 30 µL of 4% SDS, 0.1 M Tris pH 8.5, 10 mM TCEP. Samples were prepared for mass spectrometry using a modified FASP protocol (Wiśniewski et al. 2009). Samples were processed in urea, alkylated with 25 mM iodoacetamide for 30 min, and placed in a YM-30 Microcon column (Sigma). Samples were washed twice with 8 M urea, twice with 2 M urea, and then digested with 0.5 µg of lysyl endopeptidase (Wako Chemicals MS Grade) in 2 M urea overnight at room temperature. Samples were then digested with 0.5 µg of trypsin (Promega MS grade) with 0.2 µL of 0.5 M CaCl2 at 37°C for 6 h, and eluted by centrifugation. A second elution was performed with 0.5 M NaCl, and combined with the first elution. The samples were acidified with 1% formic acid, and desalted using C-18 columns (Pierce). The samples were eluted from the C-18 resin in 70% acetonitrile, 0.1% tri-fluoroacetic acid and placed in a Speedvac. Samples were analyzed on an LTQ Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to an Eksigent nanoLC-2D system through a nanoelectrospray LC–MS interface as previously described (Hill et al. 2015). A volume of 8 µL of sample was injected into a 10 µL loop using the autosampler. To desalt the sample, material was flushed out of the loop and loaded onto a trapping column (ZORBAX 300SB-C18, dimensions 5 × 0.3 mm 5 µm) and washed with 0.1% FA at a flow rate of 5 µL/min for 5 min. The analytical column was then switched on-line at 600 nL/min over an in-house-made 100 µm i.d. × 200 mm fused silica capillary packed with 4 µm 80 Å Synergi Hydro C18 resin (Phenomex). After 10 min of sample loading, the flow rate was adjusted to 350 nL/min, and each sample was run on a 240-min linear gradient of 2%–40% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid to separate the peptides. LC mobile phase solvents and sample dilutions used 0.1% formic acid in water (Buffer A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (Buffer B) (Chromasolv LC–MS grade, Sigma-Aldrich). Data acquisition was performed using the instrument supplied Xcalibur (version 2.1) software. The mass spectrometer was operated in the positive ion mode. Each survey scan of m/z 400–2000 was followed by collision-assisted dissociation (CAD) MS/MS of the 20 most intense precursor ions. Singly charged ions were excluded from CID selection. Normalized collision energies were employed using helium as the collision gas.

The resulting raw files were processed, quantified and searched using MaxQuant version 1.3.0.51 (Cox et al. 2009) and the Andromeda peptide search engine searching against the Uniprot human database. Parameters defined for the search were: Endoproteinase LysC as digesting enzyme, allowing two missed cleavages; a minimum length of 6 amino acids; fixed modifications of +8 on lysine residues (13C615N2 L-lysine), carbamidomethylation at cysteine residues as fixed modification, oxidation at methionine and protein N-terminal acetylation as variable modifications. The maximum allowed mass deviation was 10 ppm for the MS and 0.5 Da for the MS/MS scans.

hnRNP RIP experiments

MDA-MB-231 or MCF-7 cells were washed in PBS and lysed in 10 mM Hepes 7.4, 150 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM PMSF, 10% glycerol with protease and RNase inhibitors (Roche). Immunoprecipitations were performed overnight at 4°C with 500–1000 µg of lysate and 5 µg of the following antibodies: Rabbit or Mouse Total IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), hnRNP B1 (Immuno-Biological Laboratories Co. #18941), and hnRNP A2/B1 (Novus NB120-6102). For each IP, 25 uL of Protein A/G magnetic beads (Thermo-Fisher) were added to each sample and incubated an additional 2 h. Beads were washed 5× with the lysis buffer specified above, and split for RNA and protein analysis.

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

RNA was isolated with 500 µL TRIzol (Life Technologies), with extraction in 100 µL chloroform, followed by purification with the RNeasy kit (QIAGEN). Samples were DNase treated using the TURBO DNase kit (Ambion). Reverse transcription was performed using the cDNA High Capacity Kit (Life Technologies). Standard curves using in vitro transcribed HOTAIR or anti-Luciferase were used to calculate copies of each molecule recovered. RT-qPCR was performed using Sybr Green master mix (Takyon; AnaSpec Inc.) using the primers listed in Supplemental Table S3 on a Roche LightCycler 480 qPCR machine. Two qPCR replicates were performed for each sample, and these technical replicates were averaged prior to analysis of biological replicates.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

We performed chromatin immunoprecipitations of MDA-MB-231 cells cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde. Nuclear extracts were prepared as previously described (Aparicio et al. 2005). Lysates were MNase (NEB) treated with 50 U for 10 min at 37°C, and then sonicated for 5 min on a Branson sonicator at 4.5 power, 60% duty cycle. The samples were diluted fivefold with ChIP lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 0.5% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA) (Nelson et al. 2006). Immunoprecipitations were performed overnight using 400 µg of extract and 5 µg of the following antibodies: H3K27me3 (Abcam 6002 for ChIP-qPCR, Millipore 07-449 for ChIP-seq), IgG (Mouse and Rabbit from Santa Cruz), or hnRNPB1 (Immuno-Biological Laboratories Co.). For ChIP experiments including RNase treatment, 5 μg of DNase-free RNase (Roche) was added to each sample and incubated at RT for 15 min prior to the addition of antibodies for IP. Of note, 25 µL of Protein A/G beads (Thermo) were added to each IP for 2 h. The beads were washed 5× with ChIP lysis buffer, and associated DNA was de-crosslinked overnight and purified with the E.Z.N.A Cycle Pure DNA Purification kit (Omega Bio-tek). qPCR was performed as described above.

ChIP-seq library preparation and data analysis

DNA from IP samples was treated with the Epicentre End-Repair Kit. A-base addition was performed with NEB Klenow exo-, and the Illumina TruSeq universal adapter was added by overnight ligation with T4 DNA ligase (NEB). Reaction cleanup and size selection was performed using AMPure XP SPRI beads (Beckman Coulter Genomics). PCR to add indexed primers was performed with 18 cycles using Phusion polymerase. DNA was quantified by Qubit (Invitrogen), and pooled for sequencing with HiSEQ 2500 HT Mode V4 Chemistry (single 50-bp reads). Each of the eight samples yielded between 26–30 million reads. Following barcode removal, sequences were mapped to the human genome (hg19) using Bowtie 2 (Langmead and Salzberg 2012) with the default local settings. Of note, >99% of the trimmed reads for each sample aligned to the genome. Up to five reads with the same unique genomic location were retained for the analysis. The clustering program SICER (Zang et al. 2009) was used to identify H3K27me3 peaks in each sample. Biological replicates were pooled for SICER analysis in order to more successfully identify regions of enrichment for a broad histone mark. SICER parameters included: window size of 200, gap size of 1000, DNA fragment length of 300 bp, and E-value of 500. For differential analysis of samples, we used the SICER-df-rb.sh script, using a false discovery rate of 0.01 to identify significantly increased and decreased regions of H3K27me3. Genomic loci of interest were annotated with the ChIPseeker R package (Yu et al. 2015), using the UCSC.hg19.Knowngenes database. To visualize these data, we generated pileup profiles that display the counts per base pair normalized to 1 million total reads per sample. Bedtools (Quinlan and Hall 2010) was used to calculate the H3K27me3 signal across particular genomic loci of interest, and to determine the overlap between samples. The ggplot2 package of R (Wickham 2009) was used to generate the heatmaps and boxplots comparing the cumulative H3K27me3 signal at HOTAR-regulated loci. Values were scaled by row by converting each value into a Z-score using the average and SD for each row as follows: Z-score = (value − mean)/SD. ChIP-seq raw and processed data were deposited in GEO under accession: GSE73702.

Invasion and migration assays

Invasion assays were performed with precoated Matrigel invasion chambers with 8-µm pores (Corning Inc.). MDA-MB-231 cells were serum starved overnight, and 5 × 104 cells were plated onto triplicate wells. After 6 h, cells were fixed with the Kwik-Diff staining kit (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer's directions. For migration assays, we performed identical experiments using uncoated cell culture inserts with 8-µm pores (Corning). To quantify invasion and migration, six 10× images per filter were taken, and cell counts were determined using ImageJ software.

Chromatin reconstitution

To generate a DNA substrate for chromatin reconstitution, a PCR product consisting of a 601 positioning sequence (Li and Widom 2004), six LexA binding sites, five Gal4 DNA binding sites, and a viral E4 promoter were cloned into pGEM3z/601 vector backbone via isothermal assembly. PCR with a biotinylated reverse primer was used to add a biotin tag to the 3′ end of the 1.1-kb DNA substrate. Chromatin was reconstituted through a previously developed enzymatic assembly method (An and Roeder 2004; Vary et al. 2004). Biotinylated DNA, human histone octamers, human histone chaperone Nap1, nucleosome positioning factor Isw1a, and an ATP-regeneration system (final concentrations: 30 mM creatine phosphate, 3 mM ATP, 4.1 mM MgCl2, and 6.4 μg/mL creatine kinase) were incubated at 30°C for 5 h in R+ Buffer (10 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 500 µM EGTA, 10% Glycerol, 2.5 mM β-glyerophosphate, 200 µM PMSF, 1 mM DTT). Chromatin was subsequently conjugated to streptavidin magnetic beads (Life Technologies) for 2 h at RT as previously described (Johnson et al. 2009).

RNA tethering and chromatin pulldown

Equal molar quantities of 5′ RAT-tagged HOTAIR (5.6 µg) or 5′ RAT-tagged anti-luciferase (4.4 µg) IVT RNA were incubated with 250 ng LexA-PP7 fusion protein for 1 h at RT to prebind. Prebound RNA-LexA-PP7 fusion protein was incubated with 400 ng biotinylated chromatin for 1 h at RT to bind chromatin. All samples were incubated in RB buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 500 µM EGTA, 0.01% NP-40). RNA–chromatin substrates were incubated with 150 µg HeLa cell nuclear extracts for 2 h at 4°C in PB100 buffer (50 mM Hepes pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgOAc, 100 µM EDTA, 0.02% NP-40, 5% Glycerol, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM PMSF, and 1 mM DTT). All incubations were performed in an Eppendorf Thermoshaker at max RPM.

RNA–RNA interaction predictions and assays

The IntaRNA program (Wright et al. 2014) (web-based version, http://rna.informatik.uni-freiburg.de/IntaRNA/Input.jsp, default parameters) was used to query the HOTAIR sequence (the first 2000 nt, as limited by the program) versus ∼1000 nt surrounding the A2/B1 CLIP-seq peak in the 5′ region of the JAM2 RNA transcript (Huelga et al. 2012) (chromosomal position Chr21:27,011,598-27,012,594). We identified a 48-bp region with extensive complementarity between JAM2 and HOTAIR. We synthesized a 62-bp JAM2 DNA template that encompassed the 48-bp region and the adjacent A2/B1 CLIP-seq peak (gBlock, IDT) with a 5′ RAT tag and generated an IVT RAT-JAM2 RNA. RNA–RNA interaction assays were carried out in HLB-300 buffer (20 mM Hepes pH 7.9, 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1% NP-40, 10% Glycerol, 0.1 mM PMSF, 0.5 DTT). We prebound 125 nM RAT-JAM2 with 500 nM PP7-Protein A fusion protein by incubating them at RT for 1 h thermoshaking. Prebound JAM2-PP7 was incubated with Sepharose IgG beads (GE Healthcare) for 1 h with thermoshaking at RT to bind to resin. When present, 40 nM recombinant hnRNP B1 was prebound with 5 nM full-length IVT HOTAIR for 1 h thermoshaking at RT. JAM2-PP7 bound to resin was incubated with prebound HOTAIR-B1 or HOTAIR alone for 10 min thermoshaking at RT. The complex bound to resin was washed with either 3× HLB-300 or 5× HLB-500 (in assays where B1 was present) (20 mM Hepes pH 7.9, 500 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1% NP-40, 10% Glycerol, 0.1 mM PMSF, 0.5 DTT) and RNA was isolated for RT-qPCR analysis as described above.

To evaluate the necessity of the predicted JAM2:HOTAIR interaction region, we synthesized two mutant versions of HOTAIR with the 62 bp JAM2 region (nucleotides 244–306) either (i) deleted or (ii) mutated at every position to its complement base (gBlock, IDT). gBlocks were cloned into the full-length HOTAIR-pTRE3G plasmid and HOTAIR mutant IVTs were generated via the MEGAscript T7 kit (Ambion). RNA–RNA interaction assays were carried out in HLB-300 buffer, where 125 nM RAT-JAM2 RNA was incubated with 500 nM PP7-Protein A fusion protein for 1 h thermoshaking at RT. Prebound JAM2-PP7 was incubated with Sepharose IgG beads (GE Healthcare) for 1 h with thermoshaking at RT to bind to resin. JAM2-PP7 bound to resin was washed with HLB-300 and then incubated with wild-type or mutated HOTAIR IVTs for 10 min thermoshaking at RT. The complex bound to resin was washed 5× with HLB-500 and RNA was isolated for RT-qPCR analysis as described above. To account for potential variation in RNA isolation and reverse transcription efficiency, HOTAIR and JAM2 recovery were normalized to a control GFP IVT that was spiked into each sample before RNA isolation. To control for variation in the JAM2 pulldowns, JAM2 RNA recovery was used to normalize the amount of HOTAIR recovered. Two-tailed t-tests were performed on the nanograms of HOTAIR recovered from the mutant versus wild-type samples (using GFP and JAM2 normalized values). Recovery of mutant HOTAIR is displayed relative to wild-type recovery from three replicate experiments.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material is available for this article.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a DOD Breast Cancer Postdoctoral Fellowship to E.K.M. and NIGMS R00GM094291 to A.M.J. We thank E. Nguyen and J. Hesselberth for assistance with data analysis. We thank K. Hansen and M. Dzieciatkowska of the University of Colorado Denver Proteomics Core Facility for assistance with mass spectrometry. D. Neelakantan and H. Ford provided assistance with the invasion assays. M. Motamedi, D. Bentley, and R. Davis provided helpful feedback on our manuscript. We thank the Functional Genomics Core for the pLKO.1 shRNAs. The 293 cell line expressing the 10A envelope was a gift from C. Liu. MDA-MB-231 cells were a gift from H. Ford. The MS2-MBP expression construct was obtained from R. Reed. His-hNap1 plasmid was a gift from J. Nyborg and H. Scherman through the Colorado State Protein Production and Characterization Facility.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.055830.115.

REFERENCES

- Alarcón CR, Goodarzi H, Lee H, Liu X, Tavazoie S, Tavazoie SF. 2015. HNRNPA2B1 is a mediator of m6A-dependent nuclear RNA processing events. Cell 162: 1299–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An W, Roeder RG. 2004. Reconstitution and transcriptional analysis of chromatin in vitro. Methods Enzymol 377: 460–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio O, Geisberg JV, Sekinger E, Yang A, Moqtaderi Z, Struhl K. 2005. Chromatin immunoprecipitation for determining the association of proteins with specific genomic sequences in vivo. Curr Protoc Mol Biol 69: 21.3.1–21.3.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracken AP, Pasini D, Capra M, Prosperini E, Colli E, Helin K. 2003. EZH2 is downstream of the pRB-E2F pathway, essential for proliferation and amplified in cancer. EMBO J 22: 5323–5335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burd CG, Swanson MS, Görlach M, Dreyfuss G. 1989. Primary structures of the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2, B1, and C2 proteins: a diversity of RNA binding proteins is generated by small peptide inserts. Proc Natl Acad Sci 86: 9788–9792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter S, Aiello D, Atianand MK, Ricci EP, Gandhi P, Hall LL, Byron M, Monks B, Henry-Bezy M, Lawrence JB, et al. 2013. A long noncoding RNA mediates both activation and repression of immune response genes. Science 341: 789–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Qu K, Zhong FL, Artandi SE, Chang HY. 2011. Genomic maps of long noncoding RNA occupancy reveal principles of RNA-chromatin interactions. Mol Cell 44: 667–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Quinn J, Chang HY. 2012. Chromatin isolation by RNA purification (ChIRP). J Vis Exp 3912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Zhang QC, da Rocha ST, Flynn RA, Bharadwaj M, Calabrese JM, Magnuson T, Heard E, Chang HY. 2015. Systematic discovery of Xist RNA binding proteins. Cell 161: 404–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes-Rojas C, Hernandez AJ, Sarma K, Lee JT. 2014. Regulatory interactions between RNA and polycomb repressive complex 2. Mol Cell 55: 171–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, Matic I, Hilger M, Nagaraj N, Selbach M, Olsen JV, Mann M. 2009. A practical guide to the MaxQuant computational platform for SILAC-based quantitative proteomics. Nat Protoc 4: 698–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui H, Wu F, Sun Y, Fan G, Wang Q. 2010. Up-regulation and subcellular localization of hnRNP A2/B1 in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer 10: 356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidovich C, Cech TR. 2015. The recruitment of chromatin modifiers by long noncoding RNAs: lessons from PRC2. RNA 21: 2007–2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidovich C, Zheng L, Goodrich KJ, Cech TR. 2013. Promiscuous RNA binding by polycomb repressive complex 2. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20: 1250–1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J, Hayashi MK, Zhang Y, Manche L, Krainer AR, Xu RM. 1999. Crystal structure of the two-RRM domain of hnRNP A1 (UP1) complexed with single-stranded telomeric DNA. Genes Dev 13: 1102–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfuss G, Matunis MJ, Pinol-Roma S, Burd CG. 2003. hnRNP proteins and the biogenesis of mRNA. Annu Rev Biochem 62: 289–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engreitz JM, Pandya-Jones A, McDonel P, Shishkin A, Sirokman K, Surka C, Kadri S, Xing J, Goren A, Lander ES, et al. 2013. The Xist lncRNA exploits three-dimensional genome architecture to spread across the X chromosome. Science 341: 1237973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engreitz JM, Sirokman K, McDonel P, Shishkin AA, Surka C, Russell P, Grossman SR, Chow AY, Guttman M, Lander ES. 2014. RNA-RNA interactions enable specific targeting of noncoding RNAs to nascent pre-mRNAs and chromatin sites. Cell 159: 188–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyodorov DV, Kadonaga JT. 2003. Chromatin assembly in vitro with purified recombinant ACF and NAP-1. Methods Enzymol 371: 499–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X-S, Ma H-J, Zheng X-H, Ruan H-L, Liao X-Y, Xue W-Q, Chen Y-B, Zhang Y, Jia W-H. 2013. HOTAIR, a prognostic factor in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, inhibits WIF-1 expression and activates Wnt pathway. Cancer Sci 104: 1675–1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodarzi H, Najafabadi HS, Oikonomou P, Greco TM. 2012. Systematic discovery of structural elements governing stability of mammalian messenger RNAs. Nature 485: 264–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, Kim J, Horlings HM, Wong DJ, Tsai M-C, Hung T, Argani P, Rinn JL, et al. 2010. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature 464: 1071–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen KH, Bracken AP, Pasini D, Dietrich N, Gehani SS, Monrad A, Rappsilber J, Lerdrup M, Helin K. 2008. A model for transmission of the H3K27me3 epigenetic mark. Nat Cell Biol 10: 1291–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa Y, Brockdorff N, Kawano S, Tsutui K, Tsutui K, Nakagawa S. 2010. The matrix protein hnRNP U is required for chromosomal localization of Xist RNA. Dev Cell 19: 469–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog VA, Lempradl A, Trupke J, Okulski H, Altmutter C, Ruge F, Boidol B, Kubicek S, Schmauss G, Aumayr K, et al. 2014. A strand-specific switch in noncoding transcription switches the function of a Polycomb/Trithorax response element. Nat Genet 46: 973–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heubach J, Monsior J, Deenen R, Niegisch G, Szarvas T, Niedworok C, Schulz WA, Hoffmann MJ. 2015. The long noncoding RNA HOTAIR has tissue and cell type-dependent effects on HOX gene expression and phenotype of urothelial cancer cells. Mol Cancer 14: 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill RC, Calle EA, Dzieciatkowska M, Niklason LE, Hansen KC. 2015. Quantification of extracellular matrix proteins from a rat lung scaffold to provide a molecular readout for tissue engineering. Mol Cell Proteomics 14: 961–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg JR, Collins K. 2007. RNA-based affinity purification reveals 7SK RNPs with distinct composition and regulation. RNA 13: 868–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huarte M, Guttman M, Feldser D, Garber M, Koziol MJ, Kenzelmann-Broz D, Khalil AM, Zuk O, Amit I, Rabani M, et al. 2010. A large intergenic noncoding RNA induced by p53 mediates global gene repression in the p53 response. Cell 142: 409–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelga SC, Vu AQ, Arnold JD, Liang TY, Liu PP, Yan BY, Donohue JP, Shiue L, Hoon S, Brenner S, et al. 2012. Integrative genome-wide analysis reveals cooperative regulation of alternative splicing by hnRNP proteins. Cell Rep 1: 167–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A, Li G, Sikorski TW, Buratowski S, Woodcock CL, Moazed D. 2009. Reconstitution of heterochromatin-dependent transcriptional gene silencing. Mol Cell 35: 769–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamma H, Horiguchi H, Wan L, Matsui M, Fujiwara M, Fujimoto M, Yazawa T, Dreyfuss G. 1999. Molecular characterization of the hnRNP A2/B1 proteins: tissue-specific expression and novel isoforms. Exp Cell Res 246: 399–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamma H, Fujimoto M, Fujiwara M, Matsui M, Horiguchi H, Hamasaki M, Satoh H. 2001. Interaction of hnRNP A2/B1 isoforms with telomeric ssDNA and the in vitro function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 280: 625–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko S, Son J, Shen SS, Reinberg D, Bonasio R. 2013. PRC2 binds active promoters and contacts nascent RNAs in embryonic stem cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20: 1258–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko S, Bonasio R, Saldaña-Meyer R, Yoshida T, Son J, Nishino K, Umezawa A, Reinberg D. 2014a. Interactions between JARID2 and noncoding RNAs regulate PRC2 recruitment to chromatin. Mol Cell 53: 290–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko S, Son J, Bonasio R, Shen SS, Reinberg D. 2014b. Nascent RNA interaction keeps PRC2 activity poised and in check. Genes Dev 28: 1983–1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleer CG, Cao Q, Varambally S, Shen R, Ota I, Tomlins SA, Ghosh D, Sewalt RGAB, Otte AP, Hayes DF, et al. 2003. EZH2 is a marker of aggressive breast cancer and promotes neoplastic transformation of breast epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 11606–11611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretz M, Siprashvili Z, Chu C, Webster DE, Zehnder A, Qu K, Lee CS, Flockhart RJ, Groff AF, Chow J, et al. 2013. Control of somatic tissue differentiation by the long non-coding RNA TINCR. Nature 493: 231–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Wilson SH. 1990. Studies of the strand-annealing activity of mammalian hnRNP complex protein A1. Biochemistry 29: 10717–10722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Salzberg SL. 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods: 9: 357–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N, Pimienta G, Steitz JA. 2012. AUF1/hnRNP D is a novel protein partner of the EBER1 noncoding RNA of Epstein-Barr virus. RNA 18: 2073–2082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N, Moss WN, Yario TA, Steitz JA. 2015. EBV noncoding RNA binds nascent RNA to drive host PAX5 to viral DNA. Cell 160: 607–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Widom J. 2004. Nucleosomes facilitate their own invasion. Nat Struct Mol Biol 11: 763–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Liu B, Wapinski OL, Tsai M-C, Qu K, Zhang J, Carlson JC, Lin M, Fang F, Gupta RA, et al. 2013a. Targeted disruption of Hotair leads to homeotic transformation and gene derepression. Cell Rep 5: 3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Wu Z, Mei Q, Guo M, Fu X, Han W. 2013b. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR, a driver of malignancy, predicts negative prognosis and exhibits oncogenic activity in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer 109: 2266–2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Chao T-C, Chang K-Y, Lin N, Patil VS, Shimizu C, Head SR, Burns JC, Rana TM. 2014. The long noncoding RNA THRIL regulates TNFα expression through its interaction with hnRNPL. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111: 1002–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder B, Grozhik AV, Olarerin-George AO, Meydan C, Mason CE, Jaffrey SR. 2015. Single-nucleotide-resolution mapping of m6A and m6Am throughout the transcriptome. Nat Methods 12: 767–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X-H, Liu Z-L, Sun M, Liu J, Wang Z-X, De W. 2013. The long non-coding RNA HOTAIR indicates a poor prognosis and promotes metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer 13: 464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luger K, Rechsteiner TJ, Richmond TJ. 1999. Expression and purification of recombinant histones and nucleosome reconstitution. Methods Mol Biol 119: 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margueron R, Reinberg D. 2011. The polycomb complex PRC2 and its mark in life. Nature 469: 343–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]