Abstract

For a world-wide, Internet-based study on HIV/AIDS and HIV testing knowledge, we compared the yields, speed and costs of recruitment and participant diversity across free postings on 13 Internet or social media platforms, paid advertising or postings on 3 platforms, and separate free postings and paid advertisements on Facebook. Platforms were compared by study completions (yield), time to completion, completion to enrollment ratios (CERs), and costs/ completion; and by participants’ demographic characteristics, HIV testing history, and health literacy levels. Of the 482 English-speaking participants, Amazon Mechanical Turk yielded the most participants, recruited participants at the fastest rate and had the highest CER (0.78) and lowest costs / completion. Of the 335 Spanish-speaking participants, Facebook yielded the most participants and recruited participants at the fastest rate, although Amazon Mechanical Turk had the highest CER (0.72) and lowest costs/completion. Across platforms participants differed substantially according to their demographic characteristics, HIV testing history and health literay skills. The study results highlight the need for researchers to strongly consider choice of Internet or social media plaforms when conducting Internet-based research. Because of the sample specifications and cost restraints of studies, specific Internet/ social media or participant selection plaforms will be much more effective or appropriate than others.

Keywords: Social media, recruitment, Internet, health education, health surveys, health literacy, HIV, AIDS, HIV testing

Introduction

By the end of 2014, there were approximately three billion Internet users worldwide, and 44% of all households worldwide had Internet access (International Telecommunication Union, 2014). Of all Internet users in 2014, two-thirds were from developing countries, whose population of Internet users has doubled since 2009. It is no surprise that with this massive user population that the Internet is considered a valuable tool for both health information dissemination and for researchers seeking to recruit a global sample of participants.

The advantages of Internet or social media-based research include low research costs for gathering data, short turnaround time for study completion, the ability to reach people in geographically remote areas and the opportunity to include individuals who may be hard to access through other recruitment methods (Wright, 2005). Potential disadvantages of using the Internet for study recruitment include difficulty reaching populations appropriate to the goals of the study and lack of representativeness among the accessed population, which can affect the external validity of the study findings (Heiervang & Goodman, 2011). The Internet has an overwhelming number of platforms through which people can be recruited. Few studies have sought to compare yield of participants, cost of advertising, speed of solicitation, and demographic characteristics of those recruited using different Internet recruiting strategies. Understanding these aspects is vital for Internet-based research since, depending on the effectiveness of recruitment, results of the research study can be adversely impacted by even well-intentioned strategies. Therefore, there exists a need for researchers to know how to identify the websites and methods that can reach the greatest number of people appropriate to the goals of the study, are the most cost effective, and produce an appropriate sample for the research in question.

The Internet and social media appear to be enticing means of widely disseminating information about HIV/AIDS and HIV testing, perhaps particularly for those who use these media as their primary resource for information, are geographically isolated, or are hesitant to seek sensitive information in person or from other traditional sources. Accurate and engaging HIV/AIDS and HIV testing information presented through free, easy-to-access digital technologies offer new and broader ways to access communities who would benefit from this information (Singh & Walsh, 2012). Opening this avenues permits empowerment through knowledge whether for prevention, self-understanding of risk and behavior, encouragement of testing, or with hope, reduction of HIV/AIDS stigma without compromising anonymity. One such Internet-based open distance and flexible learning program is Frontline TEACH (Treatment Education Activists Combatting HIV), an adaptation of Project TEACH in Philadelphia (Sowell, Fink, & Shull, 2012). This interactive website has been offered HIV information and education since 2009, although as its authors note, its full impact has not yet been fully measured.

We recently studied the efficacy of an informational HIV/AIDS and HIV testing animated and live-action video (the “parent study”, (Shao et al., 2014)), available at http://biomed.brown.edu/hiv-testing-video/, among a global English- and Spanish-speaking Internet audience. We found that the video was able to improve knowledge about HIV/AIDS and HIV testing information among this worldwide Internet and social media-using population. While conducting this study, we utilized a myriad of Internet and social media platforms to recruit participants and through the study disseminate HIV/AIDS and HIV testing information. However, we observed that there were few prior studies that examined best practices on recruiting participants through Internet and social media platforms. Thus, we wanted to analyze our results from the parent study to show which platforms and recruitment strategies can be most effective in yielding better participation rates, yet are not cost prohibitive and yield participant samples appropriate to the goals of the study.

Our primary objective in this current investigation was to determine for a global sample of English- or Spanish- speakers which Internet or social media platforms and recruitment strategies yielded the most study completions within the shortest time, highest level of completions to enrollments (total completions/clicks or completion to enrollment ratios [CERs]), and lowest costs/completion for a study examining the efficacy of an informational HIV/AIDS and HIV testing animated and live-action video. Our secondary objective was to assess the extent to which participant demographic characteristics, HIV testing history, and health literacy varied among the samples recruited across these different Internet or social media platforms and strategies.

Methods

Design and purpose of the current investigation

This investigation examined the yield and speed of recruitment (the number of completed responses solicited from each Internet or social media platform), estimated the costs of advertising, and compared participant characteristic differences from a worldwide Internet-based study on HIV/AIDS and HIV testing knowledge. The study was approved by the investigators’ Institutional Review Board.

Parent study on which the current investigation is based

The parent study was a pre- vs. post-video knowledge improvement investigation among a global sample of English- or Spanish-speaking Internet and social media users of any age. The objectives were to determine if a fifteen-minute, live-action and animated video “What do you know about HIV/AIDS and HIV testing?” (English-language version)/”?Qué sabes sobre el VIH y sobre las Pruebas del VIH?” (Spanish-language version) (Merchant, Clark, Santelices, Liu, & Cortes, 2015) improved HIV/AIDS and HIV testing knowledge (Shao et al., 2014). The video used in this study were developed by members of the research team and described in detail previously. (Merchant et al., 2015) In brief, the fifteen-minute animated and live-action video contains United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-recommended elements of HIV/AIDS and HIV testing information (Centers for Disease & Prevention, 2001), as well as information about acute HIV infection and current methods of HIV testing. The narrated video follows two characters, racially and ethnically ambiguous male and female protagonists, as they receive information about HIV/AIDS and HIV testing and proceed through the HIV testing process. The characters are not named so to appeal to a wider audience and avoid social labels. Throughout the video, animation, graphics, images, still shots, text, and live-action segments are used to emphasize the topics presented. The English- and Spanish-language versions of the video contain equivalent content.

For the parent study, we created a study website which hosted English and Spanish versions of the study consent form; demographic characteristics, HIV testing history and health literacy questionnaires; identical pre- and post-video versions of a 25-item questionnaire that measured improvement in HIV/AIDS and HIV testing knowledge after watching the video (the “HIV/AIDS and HIV testing knowledge questionnaire”); and the video. English-language versions of the study questionnaires are provided in Appendix 1. The “HIV/AIDS and HIV testing knowledge questionnaire” contains five domains that examine understanding of and parallel the video’s content: the definition, nature, and distinction between HIV/AIDS; HIV transmission; HIV prevention; HIV testing methods; and the interpretation and meaning of HIV test results. The questionnaire’s development and evaluation have been described previously. (Merchant et al., 2015) The testing knowledge questionnaire was used as an objective assessment of improvement in knowledge before vs. after watching the video.

English or Spanish-speaking Internet users were solicited online to participate in the study across seventeen paid and free Internet or social media platforms. English- or Spanish-speaking Internet or social media users of any age who accessed the website were study eligible if they were not known to be HIV infected (by self-report), could complete the study via separate but linked English or Spanish language portals, and consented to participate. Participants were asked to give their consent on the first page of the website. Next they answered questions about their demographic characteristics, HIV testing history, the health literacy questions, a self-perceived knowledge question (which assessed subjective improvement in knowledge) and then the “HIV/AIDS and HIV testing knowledge questionnaire.” Next, they watched the video. The study website did not allow participants to fast-forward through the video to the post-video questionnaire and did not allow them to watch the video again. Afterwards they answered the self-perceived knowledge question and the “HIV/AIDS and HIV testing knowledge questionnaire” again. After completing the study, all participants were offered the chance to enter a lottery for one of four $50 Amazon.com gift cards.

Recruitment strategies

Seventeen Internet or social media platforms were used to solicit participants (Table 1) with either free postings or paid advertising. A mix of the top social networking websites by user traffic (eBiz, 2014), commerce websites, blogs, bookmarking, research solicitation websites and a general search engine were used. Platforms were selected based on their user penetration and recognition (i.e., the top sites used most frequently globally). Social bookmarking sites were selected based on number of users and ease of access (Alexa, 2014). We created a different Uniform Resource Locator (URL) for each Internet or social media platform, which allowed us to identify which platform participants used to reach the study and to track the number of times people clicked on each platform’s post. English and Spanish versions of each post were created for every platform.

Table 1.

Description of recruitment Internet or social media platforms utilized in the study

| Platforms | Type | Description | Number of Users |

|---|---|---|---|

| FREE PLATFORMS | |||

| Tumblr | Blog | Enables sharing and reposting of content | 110M |

| Craigslist | Commercial | Displays classified advertisements | 50M |

| Facebook** | Social Media | Enables sharing of photos, videos, pages, and apps | 1.3 Bn |

| LmkedIN | Social Media | Networking business and professional | 200M |

| MySpace | Social Media | Enables sharing of photos, videos, pages, and apps | 30M |

| Social Media | Enables Micro-Hogging, RSS*, updates, following organizations and individuals | 600M | |

| 4Chan | Social Bookmarking | Enables rapid sharing of content and images | N/A |

| Blinklist | Social Bookmarking | Enables tracking, saving and sharing of website links | N/A |

| Chime.in | Social Bookmarking | Aggregates news and links | N/A |

| De.li.cious | Social Bookmarking | Enables storing, sharing, and discovering web bookmarks | 5.3M |

| Digg | Social Bookmarking | Aggregates news | N/A |

| Social Bookmarking | Enables sharing of images, website, content | 48.7M | |

| Social Bookmarking | Enables sharing of images and website and aggregating news | N/A | |

| Stumbleupon | Social Bookmarking | Enables storing, sharing, and discovering web bookmarks | N/A |

| PAID PLATFORMS | |||

| General | Enables content searching | lBn+ | |

| Findparticipants | Research Specific | Enables connecting academic researchers with research participants worldwide | N/A |

| Facebook** | Social Media | Enables sharing of photos, videos, pages, and apps | 1.3 Bn |

| Amazon Mechanical Turk | Commercial | Enables crowdsourcing of Internet marketplace and completion of tasks for a small fee | 100K |

Bn=Billion, M=Million, K=Thousand, N/A=not applicable, RSS=Rich Site Summary

Facebook was used as both a free and paid platform

Free and paid platforms

We first posted a short explanation of our study and a link to the study website on platforms that did not require posting costs or paid advertising (i.e., “free” platforms). Next, we paid for advertisements on four Internet or social media platforms: Facebook, Amazon Mechanical Turk, Google, and FindParticipants (Table 2). Google and Facebook were selected due to their status as the most used websites in the world (Facebook, 2013; NationMaster, 2014). FindParticipants and Amazon Mechanical Turk are websites specifically designed to locate participants for research studies. According to previous studies, participant recruitment on Amazon Mechanical Turk was found to be at least as reliable as traditional study recruitment methods (Berinsky, Huber, & Lenz, 2012; Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011).

Table 2.

Paid platform descriptions, costs, and recruitment duration

| Platforms | Population to whom advertisement was visible |

Budget (per language) |

Cost method |

Cost details |

Duration of recruitment |

Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top 20 English- and top 20 Spanish-speaking countries by population |

$50/day | Cost per click | $.50/click | 11 days | Separate English- and Spanish- language campaigns, each with two advertisements: one linking to Facebook page, one linking to study website directly. Users could share the Facebook page to invite others to the study. |

|

| All website users | $56.63/day | Bid per click | <$2/click | 4 days | Advertisements appear as people searched for relevant topics. Link also provided to study’s Google+ page. |

|

| Amazon Mechanical Turk |

All website users | See cost details | Payment per completion |

1) 240 participants solicited per language at $0.50/completion; (2) 95 participants solicited per language at $1.00/completion; and (3) 50 Spanish-speaking participants solicited at $2.00/completion |

14 days | Posted “task” (completion of study) in English and Spanish languages. |

| FindParticipants | All registered participants |

$20 total | Lump-sum subscription |

Lump-sum subscription |

30 days | English version of a recruitment email sent to 1000 participants. Spanish version sent to 53 participants. |

For Facebook, we made our paid advertisements visible to the top 20 English-speaking and Spanish-speaking countries by population (NationMaster, 2014). No other characteristics were targeted or specified in the Facebook advertising campaign (i.e., no specific interests, age groups, gender or other attributes were selected to narrow the scope of those who could see the advertisements). Separate advertisement campaigns were created for the English and Spanish languages. For each language, we created two advertisements on Facebook. One advertisement linked directly to the study website, and the other linked to our Facebook page (which also hosted a link to the study website). Participants could access the study on Facebook either directly through an advertisement, through our Facebook page (which they also could access through an advertisement), or by seeing the Facebook page through a friend’s activity (a “like” of our page).

For Amazon Mechanical Turk, we posted a link to the study on that website and advertised payment offers for every completed response. Payment offers are bids that are advertised to viewers on the website which pay participants to complete a task, such as our study. We made separate posts in English and Spanish, which constituted different participant pools. Based on previous research, a $0.50 payment offer on Amazon Mechanical Turk could solicit participants from the United States (Berinsky et al., 2012). We experimented with increasing payment offers during the study to examine their effects on the speed and yield of recruitment (Table 2). For Google Adwords, we launched two advertising campaigns (in English and in Spanish) which linked to our study website. For FindParticipants, we paid a fixed subscription cost for the ability to solicit participants via this platform and direct them to complete the study on our study website.

Data analysis

Completions, completions/day, CERs, and cost/completions were measured by language (English or Spanish). We recorded the number of times people clicked on our posts (if these data were available), the number of people who began the study, and the number of people who completed the study, as stratified by Internet or social media platforms. For each platform, we also calculated the average number of completed surveys per day (averaged throughout the duration of the post) to determine the speed of successful recruitment for each platform. For the paid platforms, we estimated the average cost of each completed survey by platform.

We compared the distributions of demographic characteristics, HIV testing history, and health literacy levels of the participants recruited across platforms by language. For English speakers, we compared these aspects among Facebook, Amazon Mechanical Turk, versus all other platforms combined. For Spanish speakers, we compared these aspects between Facebook and Amazon Mechanical Turk due to the small number of participants recruited on other platforms. Outcomes were reported as median and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. ANOVA testing was used for comparing continuous variables among multiple groups and the Kruskal-Wallis test for categorical variables.

Results

Yield and cost of recruitment across Internet or social media platforms

English speakers

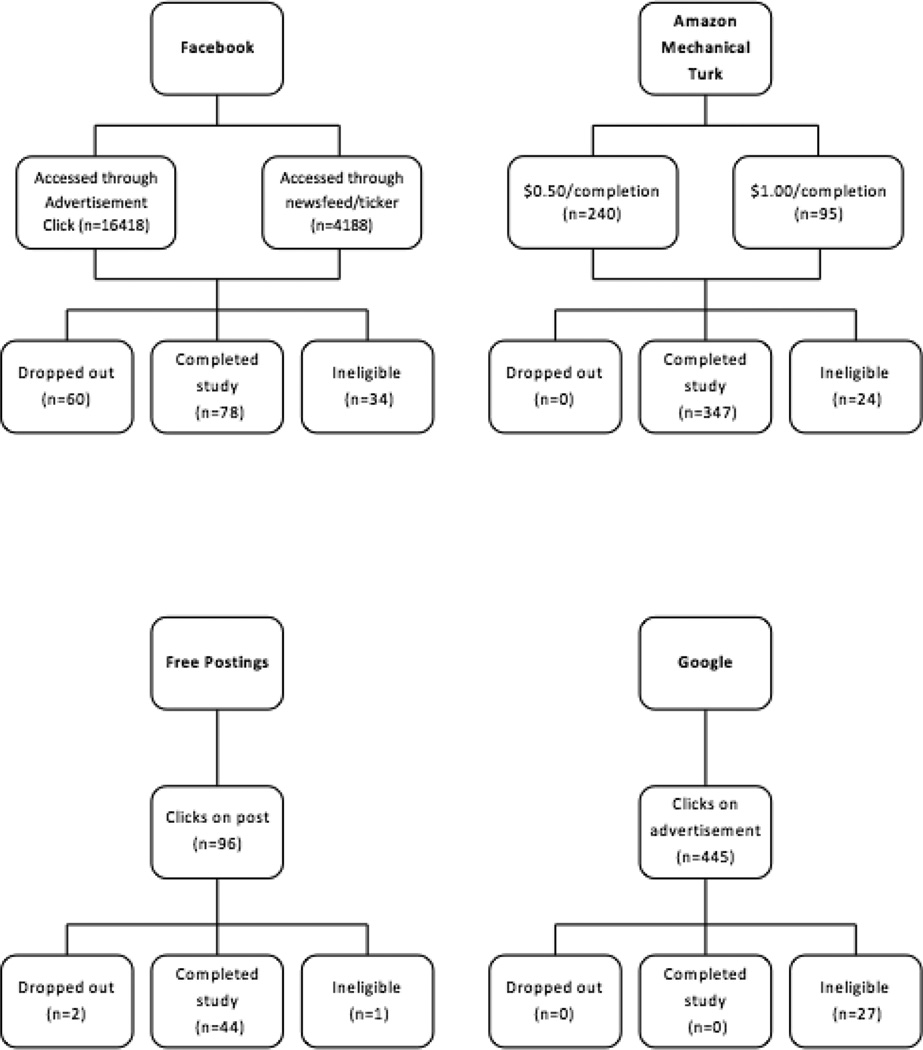

Amazon Mechanical Turk had the highest yield for recruiting English-speaking participants (Figure 1, Table 3a). It had the highest CER, no refusals, and the fewest incomplete responses. Mechanical Turk recruited participants at the fastest rate and was the most cost effective (measured in average cost/completion) platform (Table 4). Paid Facebook advertising had the greatest visibility in that more Internet users saw the advertisement on this venue as compared to the other platforms. A large number of people also accessed our study through a newsfeed or ticker update because their friends “liked” our Facebook page after the launch of the advertisement campaign. Paid Facebook advertising was the second most effective for English speakers in terms of aggregate number of those recruited. Paid Facebook advertising also yielded the most refusals and ineligible participants, the CER was much lower than the other platforms, and cost/completion was significantly higher than that of Mechanical Turk (but lower than the other two paid platforms).

Figure 1.

Summary of English-speaking participant recruitment enrolment

Table 3.

| a: English-speaking participant recruitment by platform | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advertising route | Duration of recruitment (days) |

Dollars (USD) spent |

Number of clicks |

Cost/click | Completed responses |

Incomplete responses |

Refusals | Ineligibles | Cost/ attempt |

Cost/ Completion |

| Free advertising | 42 | 0 | >96 | 0 | 44 | 56 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Delicious | 42 | 0 | 5 | 0 | ||||||

| 42 | 0 | >50 | 0 | >10 | ||||||

| 42 | 0 | >34 | 0 | |||||||

| Tumblr | 42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Blinklist | 42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Classified Ad | 42 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| Chime.in | 42 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| Digg | 42 | 0 | 2 | 0 | ||||||

| craigslist | 42 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| LmkedIN | 42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| 4chan | 42 | 0 | 2 | 0 | ||||||

| 42 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||||

| Unadvertised Facebook Page (friend invitation) |

42 | 0 | >14 | 0 | 14 | |||||

| Myspace | 42 | 0 | 2 | 0 | ||||||

| Paid advertising | ||||||||||

| Findpartcipants.com | 30 | 20 | N/A | 0 | 13 | 19 | 2 | 0 | N/A | N/A |

| Facebook Advertising | 11 | 550 | 16148 | 0.034 | 78 | 728 | 60 | 34 | 0.61 | 6.9 |

| Google Advertising | 4 | 226.5 | 445 | 0.508 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 27 | 6.66 | N/A |

| Amazon Mechanical Turk | 14 | 247.5 | N/A | N/A | 347 | 78 | 0 | 24 | 0.55 | 0.7 |

| TOTAL | 1044 | 482 | 908 | 71 | 59 | |||||

| b: Spanish-speaking participant recruitment by platform | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advertising route | Duration of recruitment (days) |

Dollars (USD) spent |

Number of clicks |

Cost/click | Completed | Incomplete responses |

Refusals | Ineligibles | Cost/ attempt |

Cost/ Completions |

| Free advertising | 42 | 0 | >25 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Delicious | 42 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| 42 | 0 | 10 | 0 | |||||||

| 42 | 0 | 7 | 0 | |||||||

| Tumblr | 42 | 0 | 3 | 0 | ||||||

| Blinklist | 42 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| Classified Ad | 42 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| Chime.in | 42 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| Digg | 42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| craigslist | 42 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| LmkedIN | 42 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| 4chan | 42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| 42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| Unadvertised Facebook Page (friend invitation) |

42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Myspace | 42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Paid advertising | ||||||||||

| Findpartcipants.com | 30 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 20 |

| 11 | 550 | 2424 | 0.036 | 173 | 501 | 29 | 25 | 0.753 | 3.14 | |

| 4 | 226.5 | 492 | 0.46 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 39 | 5.033 | 37.75 | |

| Amazon Mechanical Turk | 14 | 209.5 | N/A | N/A | 156 | 50 | 2 | 9 | 0.95 | 1.31 |

| TOTAL | 1006 | 335 | 591 | 31 | 34 | |||||

USD=United States dollars, N/A=not applicable

Table 4.

English- and Spanish-speaking participant paid Internet or social media platform recruitment summary

| English | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platform | Completion/Day | Cost/Completion | Clicks | CER |

| Paid Advertising | 7.1 | $6.90 | 16148 | 0.09 |

| Free Advertising | 0.33 | $0.00 | 18 | 0.09 |

| Amazon Mechanical Turk | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.78 |

| $0.50/completion | 120 | $0.50 | 331 | 0.73 |

| $1.00/completion | 107 | $1.00 | 123 | 0.87 |

| 0 | N/A | 445 | 0.0 | |

| Free Resources | 1.05 | N/A | 50 | 0.39 |

| Spanish | ||||

| Platform | Completion/Day | Cost/Completion | Clicks | CER |

| Paid Advertising | 15.9 | $3.14 | 15101 | 0.24 |

| Free Advertising | 0.02 | 0 | 0.24 | |

| Amazon Mechanical Turk | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.72 |

| $0.50/completion | 2.14 | $0.50 | 25 | 0.6 |

| $1.00/completion | 10.57 | $1.00 | 96 | 0.77 |

| $2.00/completion | 50 | $2.00 | 99 | 0.51 |

| 1.5 | $37.75 | 445 | 0.13 | |

| Free Resources | 0 | N/A | 3 | 0.0 |

CER=Total Completion/Clicks, N/A=not applicable

Google was the least effective of our paid platforms for English-speaking participants, having generated no completions. It also solicited a significant number of ineligible participants. Of the free platforms (Table 3a), Facebook (the page and shares before the launch of the advertisement campaign) and Reddit had the most number of completions among English speakers. Few of the free platforms had more than 20 clicks on the posts about the study.

Spanish speakers

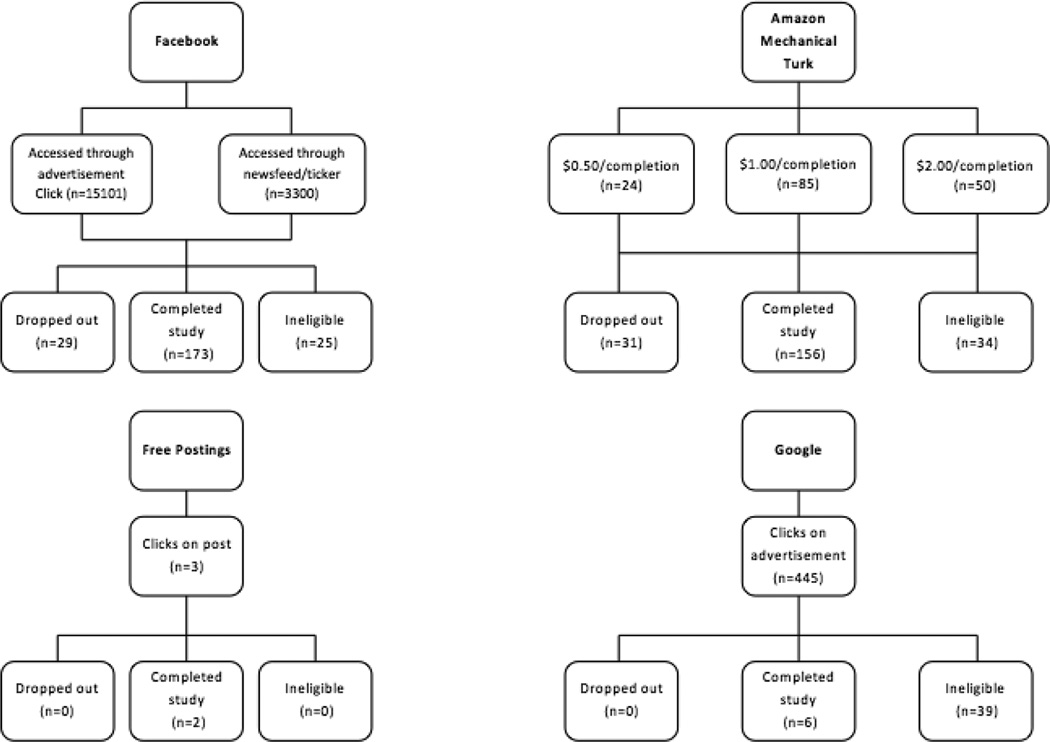

Facebook yielded the most completed responses for the Spanish-speaking participants (Figure 2, Table 3b) and the fewest ineligible responses across all recruitment platforms.

Figure 2.

Spanish-speaking participant recruitment enrollment summary

Facebook solicitation was faster for Spanish than for English-speakers, and was the fastest method of solicitation across all platforms for Spanish-speaking participants (Table 4). Mechanical Turk had the second most completed responses and was the most cost effective for Spanish speakers. Solicitation, however, was not successful until we offered $2.00 per completion. CER was higher for Mechanical Turk than other platforms. Google solicited four completed responses from Spanish-speakers, the second lowest of the paid platforms (FindParticipants had zero). It also solicited the most number of ineligible responses. Free advertising was ineffective for Spanish-speaker recruitment, having only solicited three clicks and two completed responses.

Participant differences across Internet or social media platforms

English speakers

Across platforms, approximately half of English-speaking participants were in their mid-twenties in age, most had received formal education after high school, and most self-described themselves as having strong English-language skills (Table 5a). There were notable differences in participants across platforms. As compared to the other platforms, English-speaking participants from Amazon Mechanical Turk were slightly older, had more years of formal education and had higher health literacy skills. Participants from Facebook were more likely to be male, had lower self-described English language skills, were less likely to have ever been tested for HIV (but more likely to have been tested recently), and had lower health literacy skills. Participants from all other sites were more likely to be female, have fewer years of education (high school or less), have stronger self-described English-language skills, and have been tested previously for HIV.

Table 5.

| a: English-speaking participants demographic characteristics comparison | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amazon Mechanical Turk |

Others | p-value | ||

| n=78 | n=347 | n=57 | P< | |

| Age (years; median, IQR) | 25.5 (20.0, 36) | 28.0 (25.0, 37.0) | 25.0 (20.0, 33.0) | 0.00 |

| % | % | % | ||

| Gender (female) | 29.5 | 44.1 | 57.9 | 0.00 |

| Education | 0.43 | |||

| No school | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Elementary | 1.3 | 0.3 | 1.8 | |

| High school | 3.8 | 2.4 | 3.5 | |

| General equivalency diploma | 6.4 | 8.9 | 14.1 | |

| College | 20.5 | 26.5 | 33.3 | |

| Bachelor degree | 48.7 | 45.5 | 31.6 | |

| Graduate school or higher | 9.2 | 16.4 | 15.8 | |

| Language skills | 0.00 | |||

| Very well | 59.0 | 82.4 | 93.0 | |

| Well | 34.6 | 17.6 | 7.1 | |

| Somewhat | 3.9 | 0.0 | 0.9 | |

| Not well | 2.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Self-reported HIV test | ||||

| Have ever tested for HIV | 21.8 | 38.6 | 45.6 | |

| Last HIV test | 0.02 | |||

| Less than 6 months ago | 52.9 | 17.2 | 23.1 | |

| Less than 1 year ago | 5.9 | 16.4 | 15.4 | |

| Less than 2 years ago | 29.4 | 18.4 | 26.9 | |

| Less than 5 years ago | 0.0 | 20.9 | 26.9 | |

| More than 5 years ago | 11.8 | 26.1 | 7.7 | |

| Health literacy | ||||

| Confidence with completing forms | 0.00 | |||

| Not at all | 12.8 | 0.9 | 1.8 | |

| A litte bit | 12.8 | 6.6 | 5.3 | |

| Somewhat | 14.1 | 17.3 | 21.1 | |

| Quite a bit | 28.2 | 32.0 | 43.9 | |

| Extremely | 32.0 | 43.2 | 28.1 | |

| Difficulty reading/understanding forms | 0.02 | |||

| Most of the time | 2.6 | 3.8 | 7.0 | |

| Some of the time | 15.4 | 21.0 | 7.0 | |

| A little of the time | 39.7 | 32.3 | 22.8 | |

| None of the time | 42.3 | 43.0 | 63.2 | |

| Needing help with forms | 0.00 | |||

| Most of the time | 7.7 | 5.8 | 5.3 | |

| Some of the time | 20.5 | 17.9 | 3.5 | |

| A little of the time | 29.5 | 32.9 | 21.1 | |

| None of the time | 43.5 | 70.2 | 70.10 | |

| b: Spanish-speaking participants demographic characteristics comparison | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Amazon Mechanical Turk |

p-value | ||

| n=173 | n=156 | P< | |

| Age (years; median and IQR) | 27.0 (21.0, 38) | 29.5 (25.0, 36.0) | 0.02 |

| % | % | ||

| Gender (female) | 49.7 | 47.4 | 0.00 |

| Education | 0.00 | ||

| No school | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Elementary | 1.2 | 0.0 | |

| High school | 9.8 | 1.3 | |

| General equivalency diploma | 16.2 | 8.3 | |

| College | 37.0 | 28.2 | |

| Bachelor degree | 27.8 | 49.4 | |

| Graduate school or higher | 8.1 | 12.8 | |

| Language skills % | 0.00 | ||

| Very well | 91.3 | 78.2 | |

| Well | 8.7 | 18.0 | |

| Somewhat | 0.0 | 1.9 | |

| Not well | 0.0 | 1.9 | |

| Self-reported HIV test | |||

| Have ever tested for HIV | 55.0 | 52.0 | |

| Last HIV test | 0.60 | ||

| Less than 6 months ago | 24.2 | 22.2 | |

| Less than 1 year ago | 19.0 | 24.7 | |

| Less than 2 years ago | 14.7 | 19.8 | |

| Less than 5 years ago | 28.4 | 19.8 | |

| More than 5 years ago | 13.7 | 13.6 | |

| Health literacy | |||

| Confidence with completing forms | 0.00 | ||

| Not at all | 14.5 | 18.0 | |

| A little bit | 20.3 | 7.7 | |

| Somewhat | 30.1 | 23.7 | |

| Quite a bit | 27.8 | 32.7 | |

| Extremely | 7.5 | 18.0 | |

| Difficulty reading/understanding forms | 0.20 | ||

| Most of the time | 2.9 | 2.6 | |

| Some of the time | 19.1 | 14.1 | |

| A little of the time | 31.2 | 42.3 | |

| None of the time | 46.8 | 41.0 | |

| Needing help with forms | 0.06 | ||

| Most of the time | 4.6 | 0.0 | |

| Some of the time | 15.6 | 17.3 | |

| A little of the time | 25.4 | 26.9 | |

| None of the time | 54.3 | 55.8 | |

IQR=interquartile range

Spanish speakers

Across platforms, Spanish-speaking participants were in the latter twenties in age, mostly male, and most had received formal education after high school, yet many indicated that they had lower health literacy skills. Compared to those recruited through Facebook, Spanish-speaking participants from Mechanical Turk were slightly older, more likely to be male, and were more likely to have college degrees. Participants from Facebook indicated better Spanish-language proficiency than those recruited from the other platforms. There were no differences between the platforms in participants’ HIV testing history and for two of the health literacy measures (Table 5b).

Geographic diversity

Among English speakers who completed the study, a majority came from Asia, primarily from India (Table 6). North America was the second most represented region. Of the Spanish-speaking participants, a majority was recruited from South America, with Venezuela, Colombia, and Ecuador being the most represented countries. Of those who came from Mechanical Turk, an overwhelming majority resided in India, with some from the Philippines or Pakistan. Facebook recruits were from a much more diverse geographic region, spanning an even distribution over several Latin American countries among Spanish-speaking recruits.

Table 6.

Recruitment by region and country

| Regions | Accessed in English and Spanish (Total) |

English | Spanish | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accessed study (total) |

Refused | Ineligible | Incomplete | Complete | Accessed study (total) |

Refused | Ineligible | Incomplete | Complete | ||

| North America | 285 | 182 | 0 | 2 | 73 | 182 | 103 | 1 | 1 | 46 | 103 |

| Canada | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Cuba | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| United States | 267 | 178 | 0 | 2 | 66 | 178 | 89 | 1 | 1 | 34 | 89 |

| Mexico | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 14 |

| Central America | 32 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 31 | 0 | 5 | 50 | 31 |

| Anguilla | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Aruba | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Bahamas | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Belize | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Costa Rica | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Dominican Republic | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 3 | 20 | 17 |

| El Salvador | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 5 |

| Guatemala | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Honduras | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Nicaragua | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 5 |

| South America | 151 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 150 | 2 | 18 | 237 | 150 |

| Argentina | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 8 |

| Brazil | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Bolivia | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 1 | 27 | 14 |

| Chile | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 19 | 6 |

| Colombia | 32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 0 | 2 | 47 | 32 |

| Ecuador | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 0 | 1 | 34 | 28 |

| Paraguay | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 43 | 8 |

| Peru | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 11 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Uruguay | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Venezuela | 38 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 2 | 8 | 42 | 38 |

| Europe | 26 | 14 | 0 | 2 | 12 | 14 | 12 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 12 |

| Albania | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Andorra | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Austria | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Bulgaria | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Greece | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Italy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Lithuania | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Macedonia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Netherlands | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Norway | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Portugal | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Romania | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Spain | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| Switzerland | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Ukraine | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| UK and Northern Ireland | 5 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asia | 306 | 268 | 0 | 43 | 363 | 268 | 38 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 38 |

| Afghanistan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bahrein | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Bangladesh | 2 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 81 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| China | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| India | 236 | 202 | 0 | 22 | 74 | 202 | 34 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 34 |

| Indonesia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Iran | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Israel | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Japan | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Malaysia | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Myanmar | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Oman | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pakistan | 19 | 19 | 0 | 9 | 115 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Philippines | 38 | 36 | 0 | 4 | 80 | 36 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Qatar | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Saudi Arabia | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| UAE | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vietnam | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Greater Australia | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Papua New Guinea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Australia | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Africa | 17 | 16 | 0 | 2 | 28 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Algeria | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Botswana | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Egypt | 14 | 13 | 0 | 1 | 21 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Kenya | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Morocco | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nigeria | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| South Africa | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Zambia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pacific | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| French Polynesian Islands | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Other | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Antarctica | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Discussion

This investigation provides important insight into differences in recruitment across Internet or social media platforms in terms of their yield, cost, and participant characteristics for a global study of English- or Spanish-speakers about increasing HIV/AIDS and HIV testing knowledge. Each platform used in this study exhibited advantages and disadvantages in regards to recruitment and participant diversity, which have implications for future research when using the Internet or social media for studies such as these.

Amazon Mechanical Turk and Facebook exhibited the greatest overall recruitment results. Amazon Mechanical Turk was the most effective in recruiting English-speakers in terms of cost effectiveness, CER, and total yield. This was likely due to participants being guaranteed a payment for each complete response. However, one might be concerned that participants from this platform are trained in completing online questionnaires for payment. As such, this group of participants might be less interested in learning about the topic, as compared to those who might seek information about HIV/AIDS and HIV testing for their own knowledge empowerment. We cannot gauge, however, motivation to complete the study, as that was not measured outcome. Researchers should be mindful that although websites such as Amazon Mechanical Turk might be very useful in finding participants, the applicability of the research findings to other populations might be questioned. This caution might particularly be relevant for investigations that measure the impact of educational or informational media, such as examined in the parent study on the utility of the HIV/AIDS and HIV testing video. In this study, Amazon Mechanical Turk participants could have been less engaged in the topic, which could have reduced the measured utility of the video. However, as noted, the video was shown to improve knowledge among participants (Shao et al., 2014). Future researchers examining other digital educational interventions might not be as fortunate.

Paid Facebook advertising was not as cost effective, but reached a more diverse sample geographically and demographically. Paid Facebook advertising was also more effective at reaching a Spanish-speaking audience. Another advantage in using Facebook was in the organic capabilities of content sharing. Many participants engaged in our Facebook page left comments and further questions, indicating interest in the subject beyond the scope of the parent study. In addition, participants or visitors to our page also “Liked” and “Shared” our page throughout the duration of the study, and activity on the page continued even after the advertisement campaigns ceased. These activities let to increasing the spread of the study which led to further recruitment possibilities. Further, “liking” and “sharing” led to further dissemination of the video, which is a highly useful aspect of social media networking and commensurate with the underlying goal of improving HIV/AIDS and HIV testing knowledge.

Amazon Mechanical Turk and Facebook, however, had other significant limitations despite their greater total yield and cost effectiveness. Amazon Mechanical Turk included primarily well-educated participants from South and Southeast Asia, and future researchers should expect this trend as well. There were also not as many Spanish-speakers with access to Amazon Mechanical Turk, so those wishing to recruit Spanish-speakers should investigate Facebook as an option instead. Yet, Facebook had a much lower completion rate in relation to the amount of people who accessed the study. If researchers are purely looking for quick survey completions without regards to specific demographic representation concerns, Amazon Turk would be preferable. However, this choice comes with costs and the aforementioned concerns regarding internal and external validity of the study findings.

For researchers who plan to use the Internet or social media to recruit participants, it is important to anticipate challenges during the study planning stages and consider how certain platforms might be better suited for one’s budget, demographic targets, and research goals. As demonstrated in this investigation, the reach of the study (i.e., who will see it) and conversion of views to completions differs among the platforms and can vary significantly depending on the amount of money spent for advertising and offered compensation. If a researcher is unable to spend money on recruiting, free platforms can be used, but as shown by this study’s results these platforms might be less effective at recruiting participants and time elapsed to completing recruitment goals might be longer.

The online platforms chosen for participant solicitation for studies can have significant implications on a researcher’s findings. There is a potential to reach a large, global audience, yet there also is the possibility of obtaining inappropriate or non-representative samples. Researchers should be explicit in their participant demographic characteristic needs and plan Internet-based recruitment strategies carefully, so not to discover after recruitment that the sample collected is not representative of the targeted population. Researchers also need to keep in mind that some platforms may not be fully globally accessible. Both Google and Facebook, for instance, are currently blocked in China, providing limited access to that population (Frizell, 2014). Facebook also has experienced censorship in Cuba, North Korea, and Syria. Google and YouTube have faced restrictions in China, Iran, and Pakistan (Google, 2015). Facebook and Google also are not the most used social media and search engines in all countries. There also exist popular social media websites in Latin America that are not readily used in the United States. Researchers may be interested in expanding availability of content to these other large platforms, particularly in areas experiencing censorship. Based on our experience with this study, we recommend that whenever possible researchers should examine Internet or social media platforms on their projected recruitment yields, cost of advertising and characteristics of the platform’s users. We also recommend that studies provide explicit details on their recruitment yields and participant characteristics when using multiple Internet or social media platforms to help inform future researchers on best pathways to achieve their goals.

Limitations

Given the study topic and the platforms chosen for recruitment, the findings from this study may not apply to other types of research that targets specific groups, solicits participants with other demographic characteristics or spoken languages, addresses different topics, uses other study formats or involve other Internet or social media platforms. Also, because our aim was to recruit as many participants as possible, this was an observational study, and so the platforms were not randomly chosen; the study findings (e.g., yield, costs of recruitment, recruitment diversity) were undoubtedly influenced by these factors. However, we believe that the observations were valid for the platforms chosen and study design employed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we observed significant variations in study completions, time to study completions, level of completions to enrollments and costs/completion across Internet and social media platforms in this global study of increasing HIV/AIDS and HIV testing knowledge through an animated and live-action video. In addition, we observed that participant demographic characteristics, HIV testing history, and health literacy varied among the samples recruited across Internet or social media platforms. Some platforms led to quick recruitment, yet had costs and potential concerns about internal and external validity of the study findings. Other platforms provided slower recruitment, but enabled opportunities to spread knowledge opportunities through social networking. As shown by the results of this study, there is an inherent trade-off between the rate of data collection and the diversity of participants recruited for Internet-based research. Depending on research needs in terms of speed, completions, and participant language, the choice of recruiting strategies through social media and the Internet can have very different yields, costs, and resultant participant characteristics. Researchers choosing Internet-based recruitment for studies should consider these aspects and invest their resources wisely in light of their study goals. Public health workers and advocates outside of academia concerned with information dissemination and survey work should also consider appropriate Internet and social media platforms commensurate with their objectives.

Biographies

Winnie Shao is an undergraduate student at Brown University. She completed this study as part of an independent study project. She was supported by a summer undergraduate research opportunity from the Lifespan/Tufts/Brown Center for AIDS Research (P30AI042853), which is supported by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy And Infectious Diseases.

Wentao Guan is a biostatistics graduate student at the Brown University School of Public Health. He was supported by a graduate assistantship from the Brown University Department of Emergency Medicine.

Melissa A. Clark is Professor of Epidemiology of the Brown University School of Public Health and Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Alpert Medical School of Brown University.

Tao Liu is Assistant Professor of Biostatistics of the Brown University School of Public Health.

Claudia C. Santelices is Associate Research Scientist of the Northeastern University Institute on Urban Health Research and Practice.

Dharma E. Cortés is Adjunct Assistant Professor of the Northeastern University Institute on Urban Health Research and Practice.

Roland C. Merchant is an emergency medicine physician and researcher in the Department of Emergency Medicine of Rhode Island Hospital, and Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine, Alpert Medical School of Brown University, and Epidemiology, Brown University School of Public Health.

Appendix 1: HIV/AIDS and HIV Testing Internet and Social Media Study Questionnaire

Hello! Thank you for taking the time to look at our research study. The purpose of the study is to find out how well a video we created helps people learn more about HIV/AIDS and HIV testing. This study is being conducted by researchers at Rhode Island Hospital and Brown University. First, we will ask you a few questions to see if you can be in the study. We will ask if you ever have been tested for HIV and if you ever have had a positive HIV test. We are interested in what people who do not have an HIV infection know about HIV testing. For this reason, you can be a part of this study if you have never had a positive HIV test.

For this study, we will ask you a few questions about yourself and how comfortable you are with reading and understanding health information. Next, we will ask you to answer a short quiz about what you know about HIV/AIDS and HIV testing.

Afterwards, you will watch a short video, and then answer the same short quiz to see what you learned from the video. The entire study will take about 25–30 minutes. If you leave in the middle of the study, you will be able to return to where you left off if you continue on the same computer or electronic device. If you complete the study, you have the option to enter a lottery for one of several $50 gift cards from Amazon.com. Because we are interested in how well the video helps people learn more about HIV/AIDS and HIV testing, you can only enter the study once. You can encourage your friends to enter the study!

For this study, you do not have to tell us your name. At the end of the study, if you want to enter the lottery for the Amazon.com gift card, we will ask for your email address. If you do not want to be in the lottery, then you do not have to give us your email address. You do not have to give us your email address to be a part of the study. Answering these questions and being in this study is voluntary. You can quit at any time. We do not anticipate any discomforts or risks for being in the study. There are also no benefits to you for being in the study. However, we expect that your participation will help us to understand the usefulness of our video. If you have any questions or concerns about this research study, please feel free to contact XXX at XXX. If you have any questions about your rights as a research subject please contact the XXX at XXX. Would you like to be a part of this study?

-

○

Yes(1)

-

○

No (2)

If No Is Selected, Then Skip To No problem! You are welcome to come b…If Yes Is Selected, Then Skip To End of Block

Q31 No problem! You are welcome to come back later to this website and see if you can be a part of the study. We would love to hear from you!

-

○

End(1)

If End Is Selected, Then Skip To End of Survey

-

1What is your age?

-

○1(1)

-

○2(2)

-

○3(3)

-

○4(4)

-

○5(5)

-

○6(6)

-

○7(7)

-

○8(8)

-

○9(9)

-

○10(10)

-

○11(11)

-

○12(12)

-

○13(13)

-

○14(14)

-

○15(15)

-

○16(16)

-

○17(17)

-

○18(18)

-

○19(19)

-

○20(20)

-

○21(21)

-

○22(22)

-

○23(23)

-

○24(24)

-

○25(25)

-

○26(26)

-

○27(27)

-

○28(28)

-

○29(29)

-

○30(30)

-

○31(31)

-

○32(32)

-

○33(33)

-

○34(34)

-

○35(35)

-

○36(36)

-

○37(37)

-

○38(38)

-

○39(39)

-

○40(40)

-

○41(41)

-

○42(42)

-

○43(43)

-

○44(44)

-

○45(45)

-

○46(46)

-

○47(47)

-

○48(48)

-

○49(49)

-

○50(50)

-

○51(51)

-

○52(52)

-

○53(53)

-

○54(54)

-

○55(55)

-

○56(56)

-

○57(57)

-

○58(58)

-

○59(59)

-

○60(60)

-

○61(61)

-

○62(62)

-

○63(63)

-

○64(64)

-

○65(65)

-

○66(66)

-

○67(67)

-

○68(68)

-

○69(69)

-

○70(70)

-

○71(71)

-

○72(72)

-

○73(73)

-

○74(74)

-

○75(75)

-

○76(76)

-

○77(77)

-

○78(78)

-

○79(79)

-

○80(80)

-

○81(81)

-

○82(82)

-

○83(83)

-

○84(84)

-

○85(85)

-

○86(86)

-

○87(87)

-

○88(88)

-

○89(89)

-

○90(90)

-

○91(91)

-

○92(92)

-

○93(93)

-

○94(94)

-

○95(95)

-

○96(96)

-

○97(97)

-

○98(98)

-

○99(99)

-

○100(100)

-

○

-

2What is your gender?

-

○Male(1)

-

○Female (2)

-

○Transgender (identify as male) (3)

-

○Transgender (identify as female) (4)

-

○

-

3Do you consider yourself Hispanic/Latino?

-

○No(0)

-

○Yes(1)

-

○

Answer If Do you consider yourself Hispanic/Latino? Yes Is selected

-

3aWhich one of these groups would you say best represents your race? (Choose one)

-

○White Hispanic (1)

-

○Black Hispanic (2)

-

○Other(9)

-

○

Answer If Do you consider yourself Hispanic/Latino? No Is Selected

-

3bWhich one of these groups would you say best represents your race? (Choose one)

-

○White (1)

-

○Black/African-American (2)

-

○Asian (3)

-

○Pacific Islander (4)

-

○Alaskan Native (5)

-

○Native American/American Indian (6)

-

○Other(7)

-

○

-

4What is the highest grade or year of school you completed? (Choose one)

-

○No School/Kindergarten (1)

-

○Grades 1–8 (elementary) (2)

-

○Grades 9–11 (some high school) (3)

-

○Grade 12 or General Equivalency Diploma (GED) (4)

-

○College 1–3 years (some college/associate degree) (5)

-

○College 4 years (college graduate/bachelor’s degree) (6)

-

○Graduate School/other higher education (7)

-

○

-

5In what country do you live? (Choose one)

-

○Afghanistan (1)

-

○Albania (2)

-

○Algeria (3)

-

○Andorra (4)

-

○Angola (5)

-

○Antigua and Barbuda (6)

-

○Argentina (7)

-

○Armenia (8)

-

○Australia (9)

-

○Austria (10)

-

○Azerbaijan (11)

-

○Bahamas (12)

-

○Bahrain (13)

-

○Bangladesh (14)

-

○Barbados(15)

-

○Belarus (16)

-

○Belgium (17)

-

○Belize (18)

-

○Benin (19)

-

○Bhutan(20)

-

○Bolivia (21)

-

○Bosnia and Herzegovina (22)

-

○Botswana (23)

-

○Brazil (24)

-

○Brunei Darussalam (25)

-

○Bulgaria (26)

-

○Burkina Faso (27)

-

○Burundi(28)

-

○Cambodia (29)

-

○Cameroon (30)

-

○Canada (31)

-

○Cape Verde (32)

-

○Central African Republic (33)

-

○Chad (34)

-

○Chile (35)

-

○China (36)

-

○Colombia (37)

-

○Comoros (38)

-

○Congo, Republic of the… (39)

-

○Costa Rica (40)

-

○Côte d’lvoire (41)

-

○Croatia (42)

-

○Cuba (43)

-

○Cyprus(44)

-

○Czech Republic (45)

-

○Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (46)

-

○Democratic Republic of the Congo (47)

-

○Denmark (48)

-

○Djibouti (49)

-

○Dominica (50)

-

○Dominican Republic (51)

-

○Ecuador (52)

-

○Egypt(53)

-

○El Salvador (54)

-

○Equatorial Guinea (55)

-

○Eritrea (56)

-

○Estonia (57)

-

○Ethiopia (58)

-

○Fiji (59)

-

○Finland (60)

-

○France (61)

-

○Gabon (62)

-

○Gambia (63)

-

○Georgia (64)

-

○Germany (65)

-

○Ghana (66)

-

○Greece (67)

-

○Grenada(68)

-

○Guatemala (69)

-

○Guinea (70)

-

○Guinea-Bissau (71)

-

○Guyana(72)

-

○Haiti (73)

-

○Honduras (74)

-

○Hong Kong (S.A.R.) (75)

-

○Hungary (76)

-

○Iceland (77)

-

○India (78)

-

○Indonesia (79)

-

○Iran, Islamic Republic of… (80)

-

○Iraq (81)

-

○Ireland (82)

-

○Israel (83)

-

○Italy (84)

-

○Jamaica (85)

-

○Japan (86)

-

○Jordan (87)

-

○Kazakhstan (88)

-

○Kenya (89)

-

○Kiribati (90)

-

○Kuwait (91)

-

○Kyrgyzstan (92)

-

○Lao People’s Democratic Republic (93)

-

○Latvia (94)

-

○Lebanon (95)

-

○Lesotho (96)

-

○Liberia (97)

-

○Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (98)

-

○Liechtenstein (99)

-

○Lithuania (100)

-

○Luxembourg (101)

-

○Madagascar (102)

-

○Malawi (103)

-

○Malaysia (104)

-

○Maldives (105)

-

○Mali (106)

-

○Malta (107)

-

○Marshall Islands (108)

-

○Mauritania (109)

-

○Mauritius (110)

-

○Mexico (111)

-

○Micronesia, Federated States of… (112)

-

○Monaco (113)

-

○Mongolia (114)

-

○Montenegro (115)

-

○Morocco (116)

-

○Mozambique (117)

-

○Myanmar(118)

-

○Namibia (119)

-

○Nauru(120)

-

○Nepal (121)

-

○Netherlands (122)

-

○New Zealand (123)

-

○Nicaragua (124)

-

○Niger (125)

-

○Nigeria (126)

-

○Norway (127)

-

○Oman (128)

-

○Pakistan (129)

-

○Palau (130)

-

○Panama (131)

-

○Papua New Guinea (132)

-

○Paraguay(133)

-

○Peru(134)

-

○Philippines (135)

-

○Poland (136)

-

○Portugal (137)

-

○Qatar (138)

-

○Republic of Korea (139)

-

○Republic of Moldova (140)

-

○Romania (141)

-

○Russian Federation (142)

-

○Rwanda (143)

-

○Saint Kitts and Nevis (144)

-

○Saint Lucia (145)

-

○Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (146)

-

○Samoa (147)

-

○San Marino (148)

-

○Sao Tome and Principe (149)

-

○Saudi Arabia (150)

-

○Senegal (151)

-

○Serbia (152)

-

○Seychelles (153)

-

○Sierra Leone (154)

-

○Singapore (155)

-

○Slovakia (156)

-

○Slovenia (157)

-

○Solomon Islands (158)

-

○Somalia (159)

-

○South Africa (160)

-

○Spain (161)

-

○Sri Lanka (162)

-

○Sudan (163)

-

○Suriname (164)

-

○Swaziland (165)

-

○Sweden (166)

-

○Switzerland (167)

-

○Syrian Arab Republic (168)

-

○Tajikistan (169)

-

○Thailand (170)

-

○The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (171)

-

○Timor-Leste (172)

-

○Togo (173)

-

○Tonga(174)

-

○Trinidad and Tobago (175)

-

○Tunisia (176)

-

○Turkey(177)

-

○Turkmenistan (178)

-

○Tuvalu (179)

-

○Uganda(180)

-

○Ukraine (181)

-

○United Arab Emirates (182)

-

○United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (183)

-

○United Republic of Tanzania (184)

-

○United States of America (185)

-

○Uruguay(186)

-

○Uzbekistan (187)

-

○Vanuatu(188)

-

○Venezuela, Bolivarian Republic of… (189)

-

○Viet Nam (190)

-

○Yemen (191)

-

○Zambia (192)

-

○Zimbabwe (193)

-

○

Q77 How well do you read English?

-

○

Very well (1)

-

○

Well (2)

-

○

Somewhat (3)

-

○

Not Well (4)

Answer If How well do you read English? Not Well Is Selected Or How well do you read English? Somewhat Is Selected

Q32 Would you prefer to take the quiz in Spanish? You can find the link here: XXX If not, please continue

Q78 How well informed do you think you are about HIV/AIDS and HIV testing?

-

○

Very well informed (1)

-

○

Well informed (2)

-

○

Somewhat informed (3)

-

○

Not informed (4)

-

6Have you ever been tested for HIV?

-

○No(0)

-

○Yes(1)

-

○I don’t know (97)

-

○

Answer If Have you ever been tested for HIV? Yes Is selected

-

7When was your last HIV test?

-

○Less than 6 months ago (1)

-

○More than 6 months ago, but less than one year ago (2)

-

○More than 1 year ago, but less than two years ago (3)

-

○More than 2 years ago, but less than five years ago (4)

-

○More than 5 years ago (5)

-

○Don’t know (97)

-

○

-

8Have you ever tested positive for HIV?

-

○No(0)

-

○Yes(1)

-

○

If No Is Selected, Then Skip To How did you find out about this survey? If Yes Is Selected, Then Skip To Thank you for answering the questions…

Q75 Thank you for answering the questions we asked. Based upon what you told us, you will not be able to be a part of this study. We appreciate the time you have taken on this, and we wish you well!

-

○

Finish (1)

If Finish Is Selected, Then Skip To End of Survey

Q80 How did you find out about this survey?

-

○

Someone told me about it (1)

-

○

Came across it online while searching for more information on a related topic (HIV/AIDS, sexual health, etc) (2)

-

○

Came across it online while searching for/ doing something else (3)

-

○

Contacted by an organization (Lifespan, community group, etc.) (4)

-

○

Saw it on a friend’s profile or page (5)

-

○

Other(6)

Q75 How confident are you in filling out medical forms by yourself?

-

○

Not at all (0)

-

○

A little bit (1)

-

○

Somewhat (2)

-

○

Quite a bit (3)

-

○

Extremely (4)

Q74 How often do you have problems learning about your medical condition or health because of difficulty reading and understanding written information given to you by the hospital, clinic, or your healthcare provider?

-

○

None of the time (0)

-

○

A little of the time (1)

-

○

Some of the time (2)

-

○

Most of the time (3)

Q19 How often do you have someone, such as a family member, friend, hospital or clinic worker, caregiver or anyone else, help you read materials given to you by the hospital, clinic, or your healthcare provider?

-

○

None of the time (0)

-

○

A little of the time (1)

-

○

Some of the time (2)

-

○

Most of the time (3)

Q76 Thank you for answering those questions! Now we would like you to take a short quiz to show us what you already know about HIV/AIDS and HIV testing. Next, you will watch a short video about HIV/AIDS and HIV testing. Afterwards, you will take the quiz again to show us what you learned from the video. At the end, we will show you how well you answered the quiz. Are you ready? Let’s go!

Q75 Please answer ALL of the following Questions

| No(0) | Yes (1) | Don’t Know (97) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. If a pregnant woman has HIV, will her baby definitely have HIV, too? (1) |

○ | ||

| 2. If you were infected with HIV one week ago, could your HIV test result be negative? (2) |

○ | ||

| 3. Can a woman who no longer gets her period get infected with HIV? (3) |

○ | ||

| 4. Can you prevent an HIV infection by using new (unused) needles to inject drugs? (4) |

○ | ||

| 5. Is it possible to be infected with HIV for many years and not know it? (5) |

○ | ||

| 6. If you get infected with HIV, can you completely remove HIV from your body by taking medications? (6) |

○ | ||

| 7. Can you get HIV by using the same bathroom as someone who has HIV? (7) |

○ | ||

| 8. Can oral fluids be used to test you for HIV? (8) |

○ | ||

| 9. If someone with HIV kisses you, can they infect you with HIV? (9) |

○ | ||

| 10. If the person you are having sex with tells you that he or she does not have HIV, should you still get tested? (10) |

○ | ||

Q27 Please answer ALL of the following questions

| No(0) | Yes (1) | Don’t know (97) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11. If your partner has HIV, can using condoms protect you from getting HIV? (1) |

○ | ||

| 12. Does a preliminary positive HIV test result mean that you could infect others with HIV? (2) |

○ | ||

| 13. If a mother has HIV, is her breast milk safe for her baby? (3) |

○ | ||

| 14. Is it necessary to wait 1 to 2 weeks to receive the results of a rapid HIV test? (4) |

○ | ||

| 15. If your HIV test result is negative, does that mean that it is impossible for you to get infected with HIV in the future? (5) |

○ | ||

| 16. Is it always possible to tell if someone has HIV because of the way they look?(6) |

○ | ||

| 17. If a mosquito bites someone with HIV and then bites you, can you get infected with HIV? (7) |

○ | ||

| 18. Can you prevent an HIV infection by using a mask over your mouth and nose?(8) |

○ | ||

| 19. If your final HIV test result is positive, can this test result change to negative if you are tested again in 3 months? (9) |

○ | ||

| 20. Is there a difference between being infected with HIV and having AIDS? (10) |

○ | ||

Q28 Please answer ALL of the following questions

| No(0) | Yes (1) | Don’t know (97) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21. Can you get HIV from someone who is infected but has no symptoms? (1) |

○ | ||

| 22. Do you have to be infected with HIV to get AIDS? (2) |

○ | ||

| 23. If someone has HIV and takes medication to treat it, will this mean they will have a shorter life? (3) |

○ | ||

| 24. Is a special HIV test only necessary for those who have been infected with HIV for many years? (4) |

○ | ||

| 25. Does washing your genitals or private parts help to prevent you from getting HIV? (5) |

○ | ||

Q14 Please watch this video before proceeding to the next part (the “next” button will appear after the entire video is played)

Q76 Please answer ALL of the following questions

| No (0) | Yes (1) | Don’t know (97) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. If a pregnant woman has HIV, will her baby definitely have HIV, too? (1) |

○ | ||

| 2. If you were infected with HIV one week ago, could your HIV test result be negative? (2) |

○ | ||

| 3. Can a woman who no longer gets her period get infected with HIV? (3) |

○ | ||

| 4. Can you prevent an HIV infection using only new (unused) needles to inject drugs? (4) |

○ | ||

| 5. Is it possible to be infected with HIV for many years and not know it? (5) |

○ | ||

| 6. If you get infected with HIV, can you completely remove HIV from your body with medications? (6) |

○ | ||

| 7. Can you get HIV by using the same bathroom as someone who has HIV? (7) |

○ | ||

| 8. Can oral fluids be used to test you for HIV? (8) |

○ | ||

| 9. If someone with HIV kisses you, can they infect you with HIV? (9) |

○ | ||

| 10. If the person you are having sex with tells you that he or she does not have HIV, should you still get tested? (11) |

○ | ||

Q29 Please answer ALL of the following questions

| No(0) | Yes (1) | Don’t know (97) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11. If your partner has HIV, can using condoms protect you from getting HIV? (1) |

○ | ||

| 12. Does a preliminary positive HIV test result mean that you could infect others with HIV? (2) |

○ | ||

| 13. If a mother has HIV, is her breast milk safe for her baby? (3) |

○ | ||

| 14. Is it necessary to wait 1 to 2 weeks to receive the results of a rapid HIV test? (4) |

○ | ||

| 15. If your HIV test result is negative, does that mean that it is impossible for you to get infected with HIV in the future? (5) |

○ | ||

| 16. Is it always possible to tell if someone has HIV because of the way they look?(6) |

○ | ||

| 17. If a mosquito bites someone with HIV and then bites you, can you get infected with HIV? (7) |

○ | ||

| 18. Can you prevent an HIV infection by using a mask over your mouth and nose?(8) |

○ | ||

| 19. If your final HIV test result is positive, can this test result change to negative if you are tested again in 3 months? (9) |

○ | ||

| 20. Is there a difference between being infected with HIV and having AIDS? (10) |

○ | ||

Q30 Please answer ALL of the following questions

| No(0) | Yes (1) | Don’t know (97) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21. Can you get HIV from someone who is infected but has no symptoms? (1) |

○ | ||

| 22. Do you have to be infected with HIV to get AIDS? (2) |

○ | ||

| 23. If someone has HIV and takes medication to treat it, will this mean they will have a shorter life? (3) |

○ | ||

| 24. Is a special HIV test only necessary for those who have been infected with HIV for many years? (4) |

○ | ||

| 25. Does washing your genitals or private parts help prevent you from getting HIV? (5) |

○ | ||

Q79 How informed do you think you are about HIV/AIDS?

-

○

Very well informed (1)

-

○

Well informed (2)

-

○

Somewhat informed (3)

-

○

Not informed (4)

Q72 Thank you for helping us today by being a part of this study. We really appreciate you taking the time to answer the questions we asked. To show our gratitude to you, we would like to invite you to enter a lottery for one of several $50 gift cards to Amazon.com. The total number of gift cards available in the drawing depends on the number of participants in the study. You are not required to be a part of this lottery; it is voluntary and optional. If you would like to be in the lottery, please provide us with your email address. At a later date, we will select the winners of the gift cards and notify them by email. We fully understand if you would not like to provide your email address to us. Unfortunately, that is the only way to select winners of the gift cards. But even if you don’t join in the contest, we still are very grateful to you for your help!

-

○

I would like to enter the lottery for the $50 gift cards to Amazon.com. I understand that this is a lottery, and that I might not be selected. I enter this lottery voluntarily, and am free to remove my participation in the contest at any time. Also, I understand that I can only enter this contest once. If I try to enter the contest multiple times, even with different email addresses, my entries will be disqualified. I understand that this contest can be ended at any time for any reason by the study contest organizers. Final decisions regarding qualification for the study and the contest will be made by the study contest organizers. I understand that I will need to provide my email address for this contest. I also know that I might be contacted later regarding the contest, but my email address will not be shared with any other group and will not be sold. I understand that my email address could indicate my identity, but that the study contest organizers will keep my information confidential. (1)

-

○

No, I do not want to enter the drawing (2)

If I would like to enter the I… Is Selected, Then Skip To Email If No, I do not want to enter… Is Selected, Then Skip To End of Survey

Q76 Email

References

- Alexa. The top 500 sites on the web. 2014 Retrieved from: http://www.alexa.com/topsites.

- Berinsky AJ, Huber GA, Lenz GS. Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk. Political Analysis. 2012;20:351–368. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A New source of Inexpensive, Yet High Quality, Data? Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6(1):3–5. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease, C, & Prevention. Revised guidelines for HIV counseling, testing, and referral. MMWR. Recommendations and reports: Morbidity and mortality weekly rport. Recommendations and reports / Centers for Disease Control. 2001;50(RR-19):1–57. quiz CE51-19a51-CE56-19a51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- eBiz. Top 15 Most Popular Social Networking Sites. eBi% the MBA Guide. 2014 Retrived from: http://www.ebizmba.com/articles/social-networking-websites.

- Facebook. Facebook Reports Second Quarter 2013 Results. [2013/07/24/];Investor Relations. 2013 Retrieved from: http://investor.fb.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=780093.

- Frizell S. Here Are 6 Huge Websites China is Censoring Right Now. 2014 Retrieved from: http://time.com/2820452/china-censor-web/

- Google I. Known disruptions of traffic to Google products and services. Tranpareny report. 2015 Retrieved from: https://www.google.com/transparencyreport/traffic/disruptions/#expand=Y2015.

- Heiervang E, Goodman R. Advantages and limitations of web-based surveys: evidence from a child mental health survey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2011;46(1):69–76. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Telecommunication Union. ICT Facts and Figures. Geneva, Switzerland: International Telecommunication Union; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Merchant RC, Clark MA, Santelices CA, Liu T, Cortes DE. Efficacy of an HIV/AIDS and HIV Testing Video for Spanish-Speaking Latinos in Healthcare and Non-Healthcare Settings. AIDS and behavior. 2015;19(3):523–535. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0889-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NationMaster. Countries Compared by Language. International Statistics at NationMaster.com. NationMaster.com. 2014 Retrieved from: http://www.nationmaster.com/country-info/stats/Language/Spanish-speakers.

- Shao W, Merchant RC, Clark MA, Liu T, Guan W, Santelices CA, Cortes DE. Does a video improve HIV/AIDS and HIV testing knowledge among a global sample of internet and social media users? [abstract]. Paper presented at the National Conference on Health Communication, Marketing and Media; Atlanta, GA. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Singh G, Walsh CS. Prevention is solution: Building the HIVe. Digital Culture and Education. 2012;4(1):5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sowell V, Fink J, Shull J. Innovative digital HIV and AIDS education and prevention for marginalised communities: Philadelphia’s Frontline TEACH. Digital Culture and Education. 2012;4(1):110–126. [Google Scholar]

- Wright KB. Researching Internet-Based Populations: Advantages and Disadvantages of Online Survey Research, Online Questionnaire Authoring Software Packages, and Web Survey Services. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2005;10(3):00–00. [Google Scholar]