Abstract

Despite the development of a variety of efficacious alcohol intervention approaches for college students, few student drinkers seek help. The present study assessed students’ history of help-seeking for alcohol problems as well as their estimates of how likely they would be to use various help-seeking resources, should they wish to change their drinking. Participants were 197 college students who reported recent heavy drinking (46% male, 68.5% White, 27.4% African-American). Participants completed measures related to their drinking and their use (both past use and likelihood of future use) of 14 different alcohol help-seeking options. Repeated measures ANOVAs revealed that students preferred informal help-seeking (e.g., talking to friends and family) over formal (e.g., talking with a counselor or medical provider) and anonymous resources (e.g., internet- or computer-based programs). Higher self-ideal discrepancy, greater depressive symptoms, and more alcohol-related consequences were positively associated with actual past help-seeking. Alcohol-related problems and normative discrepancy were negatively associated with hypothetical likelihood of utilizing all three help-seeking resources. These results suggest that heavy drinking college students prefer low-threshold intervention options including peer, family, computerized, and brief motivational interventions. Only 36 participants (18.3% of the sample) reported that they had utilized any of the help-seeking options queried, suggesting that campus prevention efforts should include both promoting low-threshold interventions and attempting to increase the salience of alcohol-related risk and the potential utility of changing drinking patterns.

Keywords: help-seeking, college students, alcohol intervention, brief interventions, motivation to change

There are over nine million US college students, and according to a recent survey 45% reported engaging in heavy episodic drinking (defined as at least 5+ drinks in one sitting for men and 4+ drinks in one sitting for women) at least once in a two week period (Hingson, Zha, & Weitzman, 2009). Heavy drinking increases the risk of alcohol-related negative consequences such as blackouts, injuries, and risky sexual behavior. In 2001 college drinking was associated with approximately 600,000 injuries, almost 500,000 instances of unprotected sex, 97,000 sexual assaults, and 700,000 physical assaults (Hingson, Heeren, Winter, & Wechsler, 2005). In 2005 approximately 1,825 college students died from alcohol related causes (Hingson et al., 2009).

The development of a variety of brief and efficacious interventions has been a priority for researchers in the area (e.g., Barnett, Murphy, Colby, & Monti, 2007; Carey, Carey, Maisto, & Henson, 2006; Carey, Hensen, Carey, & Maisto, 2009; DeJong, Larimer, Wood, & Hartman, 2009; Walters, Vader, Harris, Field, & Jouriles, 2009). The most thoroughly investigated evidence-based approaches are counselor- or computer-delivered interventions that often include personalized normative feedback on drinking patterns and risk that is intended to enhance motivation to change and advice on reducing risky drinking practices (e.g., information on standard drinks and blood alcohol levels). In addition to these popular brief motivational interventions (BMIs), students may also pursue a variety of other avenues for help related to their drinking, ranging from low threshold options such as obtaining psychoeducational materials on campus or on the internet, talking with family and friends, or talking with health care providers or clergy, to more formal interventions such as Alcoholics Anonymous or psychotherapy from campus or community providers (Black & Costar, 1994; Klein, 1989; Palmer, Kilmer, & Larimer, 2006).

Despite the implications and consequences of college alcohol consumption and the availability of relatively inexpensive and efficacious interventions, only a small percentage of students actually seek help for problem drinking. For example, one study of college drinkers found that only 3% reported having sought help for alcohol-related problems (Cellucci, Krogh, & Vik, 2006). Most studies that have evaluated brief intervention approaches have used samples of students who were either screened based on alcohol consumption and compensated (via course credit or payments) for their participation (e.g., Carey et al., 2006; Walters et al., 2009), or mandated by their universities as a sanction for an alcohol-related infraction (e.g., Barnett et al., 2007; Carey et al., 2009). Thus, although there are now well-established brief and efficacious interventions for heavy-drinking college student, they are apparently underutilized.

To our knowledge, only two published studies have examined college students’ self-reported likelihood to seek help by specific alcohol intervention options. Klein (1989) investigated help-seeking likelihood in a sample of 526 college students. Out of 13 help-seeking options, students were most likely to seek help from friends, substance abuse counselors, and printed information (e.g., pamphlets on alcohol use). Overall, students were less likely to seek help through more general mental health venues such as student counseling services, peer counseling centers, and university health services. This study did not examine the computerized or counselor-delivered brief intervention approaches now available on many college campuses. Another study, with a mixed sample of college students and staff, looked at willingness to seek help via low contact (e.g., videotapes, audiotapes, books) versus high contact interventions (e.g., group therapy, individual counseling) and found that participants were more willing to participate in low versus high contact strategies (Werch, 1991).

Several studies have looked at a variety of correlates of either likelihood of help-seeking or actual help-seeking among college students (Cellucci et al., 2006; Freyer, Tonigan, Keller, Rumph, John, & Hapke, 2005; Kaskutas, Weisner, & Caetano, 1997; Klein, 1989; Phillips & Hessacker, 1992; Yu, Evans, & Perfetti, 2003). These studies have addressed correlates such as (a) motivation or readiness to change, (b) gender, (c) level of alcohol use, (d) frequency of alcohol consequences, (e) problem recognition, and (f) depression. Results have generally suggested that help-seeking among college students is related to higher levels of motivation to change and problem recognition, female gender, less alcohol use, and fewer alcohol-related consequences (Cellucci et al., 2006; Klein, 1989; Yu et al., 2003). Neighbors, Palmer, and Larimer (2004) found a non-linear relation between interest in enrolling in a brief motivational intervention study to reduce risky drinking and alcohol use, such that the lightest and the heaviest college student drinkers were the least likely to express interest in participation. In the general adult population higher levels of problem recognition, along with social factors (e.g., drinking interfering with relationships), are associated with higher rates of help-seeking (Jordan & Oei, 1989). Among college students, several studies have shown a positive relationship between problem recognition and likelihood of help-seeking (Cellucci et al., 2006; Phillips & Hessacker, 1992), while one found a negative relationship (Yu et al., 2003). Cellucci and colleagues (2006) reported a positive relationship between depressive symptoms and likelihood of help-seeking in one sample and no relationship in a different sample. Interestingly, the finding that college women and students with less severe alcohol problems are more likely to seek help is inconsistent with findings from samples of adult help seekers indicating greater help-seeking among men and individuals with more severe alcohol related problems (Freyer et al., 2005; Kaskutas et al., 1997).

There are several characteristics to these studies that might explain some of the contradictory and/or counterintuitive findings. First, the various methods of both defining and measuring help-seeking may contribute to the inconsistent findings in this area. Help-seeking by low threshold and informal methods such as talking to friends and family member might have different correlates than seeking out information about ones alcohol risk from anonymous health resources (e.g., pamphlets or brochures, the internet), and seeking formal treatment from health care provide or a self help group might have additional distinct correlates. Previous research has not examined willingness to seek help across different types of intervention formats. It is possible that students who might be inclined toward a relatively low-threshold intervention like alcohol-related psychoeducational information might be disinclined to seek a more intense intervention like Alcoholics Anonymous or individual counseling. Furthermore, previous research has not examined likelihood or intentions to help-seek and actual help-seeking simultaneously, and the correlates of these phenomena might be distinct. Finally, the inconsistent findings regarding problem recognition may be related to inconsistent or inadequate measurement of that construct. For example, Phillips and Hessacker (1992) measured “problem recognition related to alcoholism,” which may be inappropriate for the college drinking population in light of the fact that most college students drink episodically and might show little concern about a progression to alcoholism.

Recently the construct of discrepancy or cognitive dissonance related to one’s level of drinking relative to peers (normative discrepancy) and the impact of drinking on important life domains (self-ideal discrepancy) has emerged as potential theoretically-based precursor of change in brief motivational interventions (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). Motivational theory posits that individuals will be motivated to change when they perceive that they drink more than others or when their drinking results in life problems (Apodaca & Longabaugh, 2009; McNally, Palfai, & Kahler, 2005; Neal & Carey, 2004). Indeed, drinking-related disruption of important life domains, more so than consumption levels, is an established predictor of help-seeking in samples of adult problem drinkers (Tucker & King, 1999). Students’ level of discrepancy, measured continuously across multiple domains, and without reference to concern related to alcoholism or severe problems (Neal & Carey, 2004), might be an important predictor of their interest in participating in an alcohol-related intervention.

Therefore, the purposes of the present study were a) to examine the rates of past help-seeking among heavy-drinking college students, b) to examine students’ reported likelihood of seeking a variety of different forms of help under the hypothetical condition that they wished to make a change in their drinking, and c) to examine student characteristics associated with both past engagement in alcohol help-seeking and likelihood of help-seeking, including gender, alcohol use patterns, alcohol problems, depression, motivation to change, and variables related to problem recognition such as normative and self-ideal discrepancy. This study extends previous research by examining college students’ self-reported likelihood to seek help by a variety of specific alcohol intervention options (including newer options such as brief motivational interventions and computer/web-based options) and evaluating a variety of predictors of both likelihood to engage in and actual past use of these alcohol intervention options. We hypothesized that students would prefer more informal help-seeking resources (i.e. talking to a friend or family member) over formal resources (i.e., seeking professional help from campus or community resources), and that female gender, greater motivation to change, greater depressive symptoms, lower alcohol use and problems, and greater discrepancy would be associated with greater likelihood of help-seeking and participation in past help-seeking.

Method

Participants

Participants were 197 undergraduate students (54% female, 46% male; Mean age = 19.42, SD = 1.92) from a large metropolitan public university in the southern United States. The sample was ethnically diverse: 68.5% of participants self-identified as White/Caucasian, 27.4% as Black/African-American, 3.0% as Hispanic/Latino, 1.5% as Asian, and 0.5% as Hawaii/Pacific Islander and Native American. Participants were allowed to choose multiple ethnic identities. The sample was representative of the university in terms of gender, and ethnicity, but included a disproportionate number of first year students (68.5%). About one-fourth (24.4%) of the sample reported participating in Greek life. Participants were eligible to participate in the study if they reported one or more heavy drinking episodes (5/4 or more drinks in one occasion for a man/woman) in the past month.

Procedure

All procedures were approved by the university’s institutional review board, and all participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study. Data for this study were derived from the baseline assessment of two randomized controlled trials of brief interventions for college student drinking. Participants in the first study were recruited from the on-campus health center (34.5% of total participants; all students other than second semester seniors were potentially eligible). Participants in the second study were recruited from a required university-wide course for first year students (65.5% of total participants). Eight-hundred fifty students were screened from the campus health center, 130 were eligible, and 74 were enrolled in the study. Regarding study two, eleven-hundred students were screened in first-year classrooms, 219 were eligible, and 133 were enrolled in the trial. Ten participants were excluded from the present analyses due to missing data. Students in both studies completed a screening evaluation, and if eligible they were invited to participate in a research study on college health. They were told that their participation would entail completing surveys and possibly completing a computer program or a one-on-one discussion/information session regarding alcohol use. Given the low-threshold and flexible nature of the MI and computerized session, and the fact that participants were not seeking help and reported only mild to moderate levels of drinking problems, the sessions were described to participants as an opportunity to discuss their drinking and to receive some information, but not as “interventions.” Participants completed all study measures during a baseline assessment session in the laboratory and prior to being randomized to an intervention condition. Participants from the two studies not differ in terms of likelihood or actual engagement in any of the help-seeking options (ps = .549, .491, & .612 for informal, formal and anonymous resources, respectively).

Measures

Alcohol consumption

Number of drinks per week was assessed using the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985). Respondents were informed about standard drink equivalents (i.e., one standard drink=12 ounces of beer, 5 ounces of wine, or 1.5 ounces of liquor) and were asked to estimate the total number of standard drinks they consumed on each day during a typical week in the past month. The DDQ has been used frequently with college students and is a reliable measure that is highly correlated with self-monitored drinking reports (Kivlahan, Marlatt, Fromme, Coppel, & Williams, 1990). Participants were also asked the number of times in the past month that they engaged in a heavy drinking episode (5/4 drinks per occasion for men/women) as well as the number of times they had been drunk/intoxicated. We created a composite variable by averaging the standardized score for the three alcohol consumption variables (e.g., drinks per week, binge episodes, times drunk) because they were highly correlated (rs > .68). We used this variable to represent consumption in all of our analyses.

Help-seeking

After consulting the college drinking literature we developed a measure to assess the hypothetical likelihood of engaging in 14 different help-seeking options, as well as actual past help-seeking using each of these options. These help-seeking options were modeled after commonly used interventions with college student drinkers and described in some detail (see Table 1 for a list of items; factor analysis results will be discussed in results section). Students were given the following instructions, “Imagine that you wanted to change your drinking habits. How likely would you be to do the following? Also indicate if you have done any of these things. Do not include your participation in this study.” For items assessing programs that students might not be aware of such as campus based brief in-person or CD-ROM interventions, or web-based interventions, participants were provided with the additional instruction to “assume that you were made aware of the program.” Also, in cases where cost of the method might be ambiguous (e.g., a session with a counselor from the community), students were told how much to assume they would have to pay or if the service was free. Students then rated how likely they would be to engage in a number of behaviors on a four-point Likert-type scale (1 = Very Unlikely, 2 = Somewhat Unlikely, 3 = Somewhat Likely, 4 = Very Likely). The internal consistency for these 14 items was .90. Each item also included an additional response option indicating that the student had “Done this in the Past.” Participants did not complete a likelihood estimate for options that they had done in the past.

Table 1.

Help-Seeking Items, Item Factor Loadings, Means, and Standard Deviations for the Help-Seeking Scale and Likelihood of Seeking Help by Method

| Item | Factor Loadings | Percentage of students somewhat or very likely to seek help |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | M | SD | ||

| 1. Decide on your own to call and make an appointment with the campus counseling center (free of charge) |

.12 | .76 | −.01 | 1.83 | 1.09 | 27.41% |

| 2. Attend an Alcoholics Anonymous Meeting | −.18 | .95 | .01 | 1.59 | .98 | 21.83% |

| 3. Make an appointment with a counselor/ psychologist in the community (assume fee of approx $100 per session unless you have insurance) |

−.15 | .82 | −.01 | 1.40 | .83 | 25.89% |

| 4. Talk to a friend | .06 | −.03 | .85 | 3.32 | .87 | 72.08% |

| 5. Talk to a relative | −.11 | .08 | .76 | 2.81 | 1.05 | 58.88% |

| 6. Search the internet for ways to reduce your drinking | .30 | −.02 | .35 | 2.65 | 1.15 | 54.82% |

| 7. Talk to a clergy member, minister | .07 | .38 | .14 | 1.66 | .94 | 21.32% |

| 8. Talk to your doctor or nurse at the Campus Health Center | .31 | .45 | .05 | 1.96 | 1.08 | 34.01% |

| 9. Complete a program via email | .86 | −.09 | .02 | 2.12 | 1.04 | 37.56% |

| 10. Complete a program that entailed several telephone conversations with a counselor |

.57 | .28 | −.06 | 1.83 | .95 | 27.4% |

| 11. Complete a one-hour counseling session that provided information/feedback about drinking at a convenient but private location on campus such as the medical clinic, dorms, or student center |

.27 | .63 | −.03 | 2.14 | 1.14 | 42.13% |

| 12. Complete a brief online program that provided information/feedback about drinking |

.95 | −.06 | −.09 | 2.35 | 1.17 | 47.21% |

| 13. Read a pamphlet or book that provides information about reducing alcohol use |

.62 | −.05 | .19 | 2.63 | 1.25 | 54.31% |

| 14. Complete a one-hour interactive program on a computer (CD-ROM) that was available on campus (assuming you were aware of such a program, invited to do so, and it was free) |

.84 | .00 | −.04 | 2.19 | 1.19 | 39.09% |

Note. A three-factor solution was found: formal, informal, and anonymous help-seeking resources. Eigenvalues for the first three factors (6.28, 1.67, and 1.33, respectively) were larger than what would be expected by chance given the number of items and the sample size, whereas the fourth eigenvalue (0.83) was much smaller than what would be expected by chance. This solution accounted for 66.31% of the initial variance and 58.01% of the extracted variance.

Alcohol-related problems

Alcohol-related problems were assessed using the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (YAACQ; Read, Kahler, Strong, & Colder, 2006). Participants are given a list of 49 potential problems related to their alcohol use and asked to indicate whether or not they have experienced that problem in the past 6 months. The YAACQ has demonstrated strong psychometric properties including predictive validity (Read, Merrill, Kahler, & Strong, 2007). Internal consistency for the YAACQ was .92 in our sample.

Motivation to change

Motivation to change alcohol use was measured using The Contemplation Ladder (Biener & Abrams, 1991), a continuous measure that asks participants to rate what thoughts they have on changing their drinking. Participants circle a rung on the ladder ranging from 0 = “No thought of changing my drinking” to 10 = “Taking action to change”.

Alcohol-Related Discrepancy

Discrepancy was measured using the Discrepancy Ratings Questionnaire (DRQ; Neal & Carey, 2004). To assess normative discrepancy, participants answered five questions that assessed their perception of their drinking level compared to that of other college students. Normative discrepancy items assessed frequency of drinking, typical quantity, maximum quantity, binge drinking, and drinking-related problems (e.g., “How frequently do you drink compared to the average college student?”). Responses ranged from less (“substantially less”) to more discrepancy (“substantially more”) on a seven-point Likert-scale. Self-ideal discrepancy was assessed by asking participants to answer five questions about how alcohol was affecting their relationships with friends, relationships with family, school-work, health, and appearance (e.g, “How is your alcohol use affecting your relationships with friends?”). Responses ranged from less (“substantially helping”) to more discrepancy (“substantially hurting”) on a seven-point Likert-scale. Internal consistency values were excellent for normative discrepancy and adequate for self-ideal discrepancy subscales (α = .91 and .67, respectively).

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). Participants were given 20 statements (e.g., “I felt depressed”) and rate how often in the past week they have felt that way ranging from 0 = Rarely or none of the time (“less than 1 day”) to 3 = Most or all of the time (“5–7 days”). Internal consistency for the CES-D was .98 in our sample.

Data Analysis Plan

First, descriptive analyses were conducted in order to examine rates of past help-seeking and “likelihood to seek help” for the 14 intervention options. Because participants did not complete a likelihood estimate for options that they had done in the past, those participants who reported that they had sought help using a given method were excluded from any analysis related to likelihood of future help seeking for that particular method. Next, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis to evaluate whether or not the 14 help-seeking options clustered into meaningful units that could then be used to evaluate, more parsimoniously, our hypotheses related to student preferences among help-seeking options and correlates of help-seeking. We then conducted a repeated-measures ANOVA to evaluate differences in level of likelihood to seek help across the intervention types, and to evaluate the possibility of gender interactions. We conducted separate hierarchical regression analyses to evaluate the associations between demographic variables, drinking, alcohol problems, motivation to change, discrepancy, depression, and future help-seeking likelihood. Finally, we conducted t and chi-square tests to evaluate whether or not these variables differed between students who had sought help in the past versus those who had not.

Results

Sample Characteristics and Descriptive Statistics on Help-Seeking

Participants reported drinking an average of 16.10 standard drinks during a typical week in the past month (SD = 13.06) and 5.78 (SD = 4.82) past month heavy drinking episodes. Almost every participant (97.5%) noted one or more alcohol-related problems (M = 12.59, SD = 8.55). Thirty six students (18.3% of the sample) reported engaging in some form of alcohol-related help-seeking in the past. Talking to friends (13%) and talking to relatives (10%) were the most frequently endorsed help-seeking options. Resources such as searching the internet (4.3%) and speaking with a clergy member or attending an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting (3%) were less frequently endorsed. All of the other help-seeking methods were utilized by fewer than 3% of students.

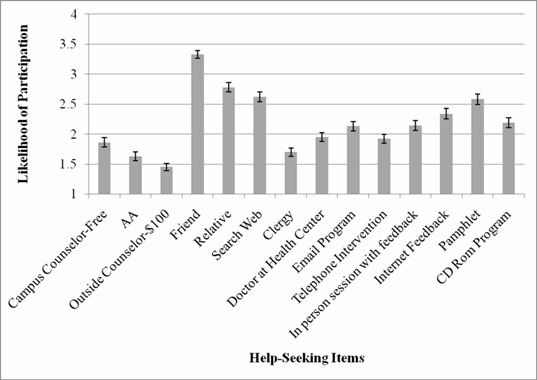

Figure 1 shows the mean likelihood of engaging in help-seeking ratings (for students who had not sought help using a particular option) for each of the 14 help-seeking options. Students reported that they would be most likely to talk to a friend (M = 3.33) or talk to a relative (M = 2.78) if they were interested in changing their drinking habits. Students reported that they would be least likely to utilize more formal resources such as making an appointment with a community counselor or psychologist (M =1.45) or attending Alcoholics Anonymous (M = 1.63). Students reported intermediate, moderate levels of likelihood to utilize anonymous resources for help-seeking such as pamphlets and internet sites, as well as brief computerized- and counselor-delivered interventions. We also examined the percentage of students reporting a score of at least three on each item, indicating that they would be “somewhat likely” or “likely” to seek help using that method (see Table 1).

Figure 1.

Means (± standard error) of ratings of the future likelihood of seeking help from different helping resources among college students. Hypothetical likelihood to seek help was measured using a 4-point scale: 1 = very unlikely, 2 = somewhat unlikely, 3 = somewhat likely, 4 = very likely. Ratings below 2.5 indicate a low mean likelihood of seeking help via each method.

Factor Analysis of the Help-Seeking Items

To determine if the help-seeking items clustered into identifiable factors we conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA), the results of which are displayed in Table 1. We used maximum likelihood extraction and an oblique rotation method (promax), because we anticipated that any factors that emerged would likely be correlated with each other. Parallel analysis (Horn, 1965) indicated that the eigenvalues for the first three factors (6.28, 1.67, and 1.33, respectively) were larger than what would be expected by chance given the number of items and the sample size, whereas the fourth eigenvalue (0.83) was much smaller than what would be expected by chance. The scree plot also supported a three-factor solution. Thus, we concluded that a three-factor solution provided the best fit to the data. This solution accounted for 66.31% of the initial variance and 58.01% of the extracted variance.

All but two of the items loaded cleanly onto a single factor (i.e., > .40 loading on its primary factor and < .35 loadings on the other factors). One item, “Search the internet for ways to reduce your drinking,” had a relatively low loading and cross-loaded onto two factors (.29 and .36). However, given the potential importance of searching the internet as a help-seeking process among college students, we decided to retain this item and made a rational decision to assign it to a factor we labeled “anonymous help-seeking” as the five other items on this factor involve help-seeking without in-person contact (e.g., “Complete a brief online program that provides information/feedback about drinking,” “Read a pamphlet or book that provides information about reducing alcohol use”). A second item, “Talk to a clergy member or minister,” only loaded .38 on its primary factor, but its loadings on other factors were quite low (< .15). Therefore, we also chose to retain this item on its primary factor. We labeled the second factor “formal help-seeking,” as the six items on the factor involve help-seeking from a professional or other formal source. Finally, we labeled the third factor “informal help-seeking,” as the two items on the factor involve help-seeking from non-professional sources (friends and family). The internal consistencies for the help-seeking subscales were .76 (informal help-seeking), .87 (formal help-seeking), and .86 (anonymous help-seeking) in our sample. Pearson r results revealed significant correlations between all three scales (r = .36 – .56, p < .01).

Preferences among Help-Seeking Domains

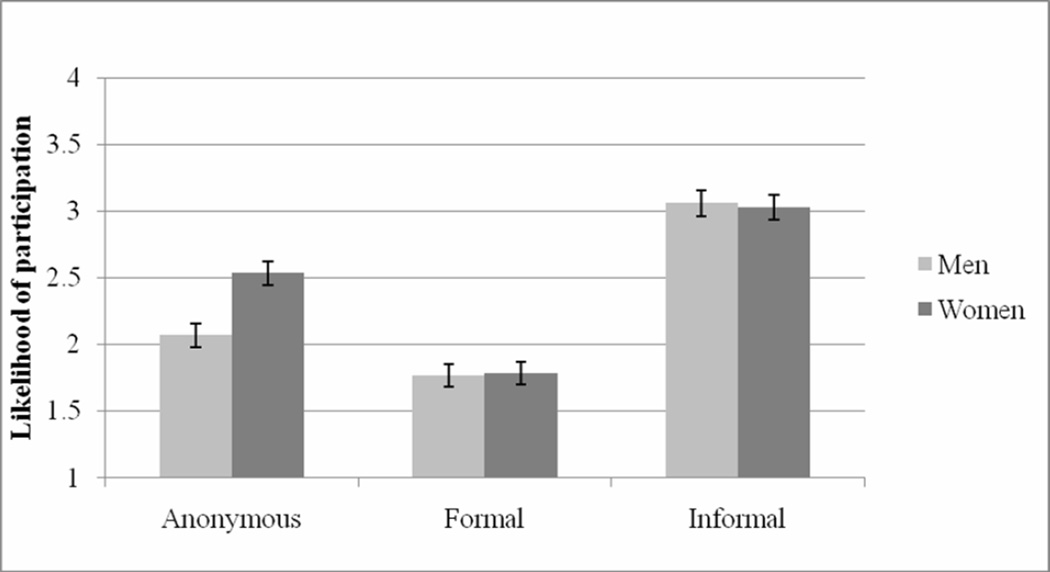

We conducted a 3 × 2 repeated measure ANOVA to evaluate differences in likelihood of help-seeking across the three domains, as well as possible interactions between preference and gender. The ANOVA results revealed significant differences between the three help-seeking domains (F (2, 179) = 180.36, p <.001). Pairwise comparisons indicated that students were more likely to utilize informal resources (M = 3.04, SD = .91) over anonymous (M = 2.32, SD = .88) and formal (M = 1.78, SD = .79) resources (ps <.001), and that anonymous resources were preferred over formal resources (p < .001). There was also a significant help-seeking domain by gender interaction, F (2, 157) = 8.41, p =.004. Women rated the anonymous help-seeking resources higher than did men (Ms = 2.53 & 2.07, respectively, p < .001, see Figure 2). An exploratory repeated measure ANOVA revealed that there was not a significant interaction between help-seeking domains and ethnicity. White (n = 126) and African-American (n = 47) students reported nearly identical preference ratings across the three help-seeking domains.

Figure 2.

Mean (± 1 standard error) of hypothetical likelihood to seek help by informal, anonymous, and formal resources among men and women. Hypothetical likelihood to seek help was measured using a 4-point scale: 1 = very unlikely, 2 = somewhat unlikely, 3 = somewhat likely, 4 = very likely. Men and women reported almost identical likelihood to utilize formal and informal resources for help-seeking. However, there was a significant difference between men and women and likelihood to seek help via anonymous resources. Women rated themselves as more likely to seek help via these resources than did men.

Characteristics of Students who Sought Help for Alcohol in the Past

Thirty-six students reported actually engaging in one or more help-seeking option. The relatively small number of help seekers did not allow us to examine the characteristics of help-seeking in each domain with adequate power, so we instead compared students who reported any past help-seeking to students who reported no past help-seeking. A series of t-tests indicated that help-seekers reported greater levels of alcohol problems, self-ideal discrepancy, and depression than students who have never sought help for an alcohol problem (see Table 2). There were no significant differences on drinking, motivation to change, or normative discrepancy. There were no gender differences in rates of help-seeking, χ2 (1, N = 179) = 0.15, p = .90.

Table 2.

Help-seeking, Drinking Variables, and Depression in Help-Seekers Versus Non-Help-Seekers

| Help-Seeking | t-statistic | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n = 36 M (SD) |

No n = 161 M (SD) |

(df) | |

| Typical week drinking | 16.82 (12.74) | 15.93 (13.16) | t (195) = −0.37 |

| Binge episodes | 6.56(5.14) | 5.59 (4.74) | t (195) = −1.08 |

| Number of times drunk | 7.08 (6.48) | 5.54 (4.85) | t (44.2) = −1.35a |

| Drink Composite | 0.38 (1.01) | 0.18 (.90) | t (194) = −1.21 |

| Motivation to Change | 4.06 (3.33) | 3.03 (2.64) | t (43.81) = −1.71a |

| Negative consequences | 15.64 (9.58) | 11.91 (8.18) | t (195) = −2.40* |

| Depression scale total | 15.86 (9.29) | 12.33 (7.34) | t (193) = −2.47* |

| Normative Discrepancy | 19.11 (6.52) | 18.02 (6.55) | t (195) = −0.90 |

| Self-Ideal Discrepancy | 21.89 (2.45) | 20.70 (1.99) | t (45.91) = −2.73*a |

p < .05

Note equal variances could not be assumed for these values

Predictors of Likelihood of Engaging in Future Helping-Seeking

We examined the associations between reported likelihood of hypothetical help-seeking on each of three domains (informal, anonymous, and formal) and variables related to alcohol consumption, alcohol problems, cognitive variables (motivation to change and discrepancy), and depression (Table 3). In the hierarchical regression model, the drinking composite score was entered into step one, followed by alcohol problems in step two, and then each independent variable was entered individually into step three for a total of 18 separate regression models (six for each method of help-seeking). Greater likelihood to engage in informal help-seeking was related to lower levels of normative discrepancy, β = −.215, p = .043 and lower level of alcohol-related problems, β = −.178, p = .036. Greater likelihood to engage in formal help-seeking was related to lower levels of normative discrepancy, β = −.282, p = .003, and lower levels of alcohol-related problems, β = −.308, p = .002. Greater likelihood to utilize anonymous help-seeking resources was related to lower levels of normative discrepancy, β = −.198, p = .043, lower levels of alcohol-related problems, β = −.244, p = .003, and higher levels of depression, β = .157, p = .030. We also evaluated a quadratic model that included the square of the drinking composite variable as an additional predictor of help-seeking (Neighbors et al., 2004). However, the quadratic term was not significant. Finally, to determine if these relations were related to demographic variables, we computed bivariate correlations between several demographic variables (gender, age, year in school, ethnicity) and the help-seeking likelihood ratings. The only significant association was between gender and anonymous help-seeking (females reported higher likelihood of engaging in anonymous help-seeking). Based on this finding, we then conducted the anonymous help-seeking regression equations again using gender as a covariate and found that the depression finding was the only one that was no longer significant.

Table 3.

Help-seeking Subscales Predicting Alcohol Problems, Motivation, Depression, and Discrepancy†

| Type of Help-Seeking Resource |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informal | Formal | Anonymous | ||||

| Predictor | ∆R2 | β | ∆R2 | β | ∆R2 | β |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Drinking Composite | 0.0 | .025 | .010 | |||

| Step 2 | ||||||

| Alcohol Problems | .025 | −.178* | .045 | −.247** | .045 | −.244** |

| Step 3 | ||||||

| Motivation to Change | .013 | −.125 | .014 | −.134 | .001 | .035 |

| Step 3 | ||||||

| Self-Ideal Discrepancy | 0.0 | .019 | 0.0 | .004 | .009 | .107 |

| Step 3 | ||||||

| Normative Discrepancy | .022 | −.215* | .041 | −.282** | .02 | −.198* |

| Step 3 | ||||||

| Depression | .015 | −.125 | .015 | .124 | .023 | .157* |

Each regression model included the drinking composite variable as a covariate. Separate analyses were conducted with motivation to change, self-ideal discrepancy, normative discrepancy, and depression as predictor variables and also included alcohol problems as a covariate.

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01

Discussion

In terms of hypothetical future help-seeking preferences, student drinkers preferred “informal” help-seeking resources (e.g., talking to a friend or family member) over “anonymous” resources (e.g., participating in an online intervention program; reading an educational pamphlet about alcohol use), which were in turn preferred over “formal” resources (e.g., attending an AA meeting; discussing alcohol use with a doctor). Within the category of formal resources, single-session brief motivational interventions (BMIs) that occur on campus were rated substantially higher than community based counseling or Alcoholics Anonymous. It is important to note that on average, participants reported that they would be somewhat or very likely to seek help via only four resources (e.g., talking to friends and family, searching the internet, and reading a pamphlet), and most of the resources received low likelihood ratings.

Consistent with results from the adult help-seeking literature, the 18.3% of students who had sought help for alcohol experienced more negative effects of drinking (even at similar levels of consumption to non-help-seekers), perceived that drinking had a more negative impact on important life domains, and reported experiencing more subjective distress/depression. In contrast to the results with actual help seekers, hypothetical future help-seeking was either not associated with or negatively associated with the alcohol use, alcohol problems, and discrepancy variables. Alcohol-related problems and normative discrepancy were negatively associated with likelihood of utilizing anonymous help-seeking resources, whereas depression was positively related to likelihood to seek help. Alcohol use, alcohol-related problems, and normative discrepancy were negatively associated with likelihood of utilizing formal help-seeking resources. Normative discrepancy and alcohol consequences were negatively associated with likelihood of utilizing informal help-seeking resources. Therefore, students who reported more alcohol-related problems and higher levels of discrepancy endorsed lower levels of likelihood to seek help across all three resources. These results are consistent with previous research with college students indicating that lower levels of alcohol-related problems are associated with an increased likelihood to seek help (Cellucci et al., 2006; Klein, 1989). Other than the positive association between depression and anonymous help-seeking, these findings are inconsistent with findings from the adult help-seeking literature indicating a positive relation between problem severity and help-seeking (Tucker & King, 1999).

There are several possible explanations for these findings, some of which are counterintuitive. Research with adult problem drinkers suggests that a) help-seeking usually occurs in the later stages of problem development, some time after the initial problem recognition, b) heavy substance use itself is not reliably associated with help-seeking among adults, and that c) help-seeking is often preceded by psychosocial problems, especially interpersonal problems, related to substance use and by receiving social messages that one might need to seek help (Marlatt, Tucker, Donovan, & Vuchinich, 1997; Tucker & King, 1999). Thus, although general impairment such as depression may stimulate interest in seeking help, the presence of heavy drinking, alcohol problems, and even problem recognition (discrepancy), may not be enough to encourage help seeking in college students, many of whom have only recently begun drinking. Moreover, given the normative nature of heavy drinking on college campus (e.g., Wechsler, Lee, Kuo, Seibring, Nelson et al., 2002), there may be minimal social sanctions against heavy drinking; students may not face stigma or disapproval for levels of drinking and consequences that would likely elicit disapproval from family or friends in other social/developmental contexts (e.g., in high school, or the post-college years). There may also be institutional factors that actually mitigate students’ experiences of negative outcomes associated with drinking (Borsari, Murphy, & Barnett, 2007). For example, punishment for alcohol-related incidents or injuries may be handled through campus police and medical personal, which often insulates students from arrests or medical bills. These factors may increase the threshold for problem severity necessary for students to consider seeking alcohol-related services. It is also possible that heavy-drinking students do not seek help, despite severe consequences, due to lack of knowledge about help-seeking options, stigma associated with help-seeking, or lack of willingness to accept the label of a “problem drinker,” which they might believe is necessary criterion for seeking help (Cellucci et al., 2006). Unfortunately we did not assess stigma or identification with the “problem drinker” label in this sample.

The finding that heavier drinking college students are paradoxically less interested in alcohol interventions than relatively lighter drinking students (all students in this sample were heavy drinkers) may suggest that students who choose to drink relatively moderately in the college context may be very aware of the potential problems associated with drinking and thus more amenable to the possibility of help-seeking should they experience those problems. There is also evidence that heavy drinkers experience more social benefits associated with drinking than lighter drinkers which might lead to lower interest in help-seeking (Murphy, McDevitt-Murphy, & Barnett, 2005; Skidmore & Murphy, in press). Although we did not observe a curvilinear relation between drinking level and help-seeking, our finding is partially consistent with the results of a previous study which demonstrated that student with moderate drinking levels were more likely than heavy drinkers to enroll in a brief intervention trial (Neighbors et al., 2004).

Nevertheless, the present results suggest that the minority of students who actually do seek help (18.3% of our sample) are in fact experiencing more depression, alcohol problems, and discrepancy about the impact of drinking on life domains than other students and that they tend to seek help primarily by talking to friends and family. It is also noteworthy that although the rate of help-seeking in our sample was relatively low, it was about six times the rate reported in the Cellucci and associates (2006) study. It might be that our rate was higher due to the fact that we included only heavy drinkers and asked about a wide range of help-seeking resources, including lower threshold resources (e.g., talking to friends and family members, searching the internet for alcohol information) that accounted for the majority of help-seeking.

Our study has at least three important implications for alcohol-related help-seeking among college students. The first is that students seem to be most likely to turn to friends and family for help with alcohol problems. Some parent-based interventions have been shown to be effective at reducing college student alcohol use (e.g., Turrisi, Jaccard, Taki, Dunnam, & Grimes, 2001; Turrisi, Larimer, Mallett, Kilmer, Ray et al., 2009), so these may reflect a particularly promising strategy given college students’ willingness to talk to relatives should they decide to seek help regarding their alcohol use. Similarly, at least one trial has shown that incorporating peers into brief alcohol interventions may enhance their effectiveness (Tevyaw, Borsari, Colby, & Monti, 2007), and the positive relationship between perception of friends’ drinking and one’s own alcohol use is well-established (Borsari & Carey, 2003). Thus, another potentially promising avenue for reducing high-risk drinking would be developing effective peer-based or peer-delivered programs (Fromme & Corbin, 2004). Finally, educational campaigns that provide people with information about how to help their friends and family members overcome a drinking problem may be a worthwhile investment (Turrisi et al., 2001), given that conversations with parents/friends about drinking-related concerns seem to be useful and would typically happen outside of a formal intervention context.

A second important implication is that these results provide support for distributing and publicizing alcohol related information on campus via pamphlets and web-sites, as students noted a high likelihood that they would use this information should they want to change their drinking. There is substantial evidence for the efficacy of self-help or bibliotherapy for alcohol problems (Apodaca & Miller, 2003). However, because there is some evidence that educational approaches are typically not efficacious on their own (DeJong et al., 2009), colleges and universities should use these low threshold media to further enhance problem recognition (e.g., by including normative drinking data or self-report alcohol problem scales) and to provide links to more efficacious, personalized brief intervention modalities, such as brief counselor or computer-administered drinking feedback.

A final implication in this area is that college students may be fairly receptive to several brief intervention approaches with demonstrated efficacy, including both counselor and computer-delivered personalized feedback based approaches. Despite the fact that the mean likelihood rating suggested that overall students are unlikely to utilize these resources, they preferred both of these formats to telephone based interventions. In contrast to the ratings for BMIs, students reported a very low likelihood of attending Alcoholics Anonymous, community counseling, or having discussion with a clergy member if they were interested in changing their drinking. Although women reported greater likelihood to engage in computerized and other anonymous intervention approaches than men, men and women otherwise reported similar likelihood of future help-seeking, and similar rates of past help-seeking. Women may be especially receptive to opportunities to receive drinking information and feedback privately, without formal help-seeking. The overall gender similarity in help-seeking is somewhat surprising given the fact that undergraduate women report more positive attitudes toward help-seeking for alcohol-related problems (Cellucci et al., 2006), and greater levels of help-seeking across a range of physical and psychiatric problems (Mansfield, Addis, & Courtenay, 2005).. The present study is the first to examine help-seeking preferences in a sample consisting of over 25% African-American students, who appear to have very similar alcohol help-seeking preferences as White students.

There were a few limitations to the study that warrant attention. Although our sample was diverse with respect to gender and ethnicity, generalizability of the findings is limited by the fact that data were collected at a single university. Additionally, because we measured likelihood of engaging in future help-seeking via primarily informal resources, results may not generalize to formal alcohol treatment help-seeking models (e.g., Orford, Kerr, Copello, Hodgson, Alwyn et al., 2006) and likelihood to engage may not be predictive of actual help-seeking. Another limitation is our reliance on self-report data although this concern is mitigated by evidence suggesting that self-report alcohol-related data are generally reliable and valid (e.g., Babor, Steinberg, del Boca, & Anton, 2000). Furthermore, our measure was limited to only 14 options for help-seeking and future research should study preferences for additional intervention options including inpatient treatment and pharmacotherapy. Additionally, this study is cross-sectional and is therefore limited in establishing causal relations among variables. It is possible, for example, that the greater self-ideal discrepancy observed among help seekers is a consequence of rather than a contributor to help-seeking. Finally, the number of students who had actually engaged in help-seeking behaviors was low (36), which may limit the conclusions that can be made from analyses addressing that particular topic.

Despite these limitations, this study addresses several important yet understudied topics related to college student drinking. To our knowledge, it is the first study to examine both preference for different types of very specific help-seeking behaviors (including personalized feedback and web-based approaches) and variables that predict likelihood or actual engagement in such behaviors. The inclusion of likelihood of future help-seeking is important in light of the low base-rate of help-seeking in this population and the fact that using actual engagement as a proxy for help-seeking preference assumes that all intervention types are equally available and publicized. Indeed, most students probably have only minimal knowledge of or access to effective and user friendly brief interventions. We encourage researchers and college personnel to consider students’ stated preferences for the various intervention approaches when considering which programs to evaluate and/or disseminate.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by research grants from the Alcohol Research Foundation (ABMRF; JGM) and the National Institutes of Health (AA016304 JGM; AA016120 MEM).

References

- Apodaca TR, Longabaugh R. Mechanisms of change in motivational interviewing: A review and preliminary evaluation of the evidence. Addiction. 2009;104:705–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apodaca TR, Miller WR. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of bibliotherapy for alcohol problems. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;59:289–304. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Steinberg K, Del Boca F, Anton R. Talk is cheap: Measuring drinking outcomes in clinical trials. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:55–63. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Murphy JG, Colby SM, Monti PM. Efficacy of counselor vs. computer-delivered intervention with mandated college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2529–2548. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biener L, Abrams DB. The Contemplation Ladder: Validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychology. 1991;10:360–365. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.5.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DR, Smith MA. Reducing alcohol consumption among university students: Recruitment and program design strategies based on social marketing theory. Health Education Research. 1994;9:375–384. doi: 10.1093/her/9.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Murphy JG, Barnett NP. Predictors of alcohol use during the first year of college: Implications for prevention. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2062–2086. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Carey MP, Maisto SA, Hensen JM. Brief motivational interventions for heavy college drinkers: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:943–954. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Hensen JM, Carey MP, Maisto SA. Computer versus in-person intervention for students violating campus alcohol policy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:74–87. doi: 10.1037/a0014281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cellucci T, Krogh J, Vik P. Help-seeking for alcohol problems in a college Population. The Journal of General Psychology. 2006;133:421–433. doi: 10.3200/GENP.133.4.421-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJong W, Larimer ME, Wood MD, Hartman R. NIAAA’s rapid response to college drinking problems initiative: reinforcing the use of evidence-based approaches in college alcohol prevention. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, supplement. 2009;16:5–11. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyer J, Tonigan JS, Keller S, Rumpf H-J, John J, Hapke U. Readiness for change and readiness for help-seeking: A composite assessment of client motivation. Alcohol & Alcoholism. 2005;40:540–544. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Corbin WR. Prevention of heavy drinking and associated negative consequences among mandated and voluntary college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:1038–1049. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter M, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24: Changes from 1998–2001. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:259–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24: Changes from 1999–2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, Supp. 2009;16:12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn JL. A rationale and test for the number of factors in a factor analysis. Psychometrica. 1965;30:179–185. doi: 10.1007/BF02289447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan CM, Oei TPS. Help-seeking behaviour in problem drinkers: A review. British Journal of Addiction. 1989;84:979–988. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaskutas LA, Weisner C, Caetano R. Predictors of help-seeking among a longitudinal sample of the general population, 1984–1992. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:155–161. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA, Fromme K, Coppel DB, Williams E. Secondary prevention with college drinkers: Evaluation of an alcohol skills training program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:805–810. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.6.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein H. Helping the college student problem drinker. Journal of College Student Development. 1989;30:323–331. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield AK, Addis ME, Courenay W. Measurement of men’s help seeking: Development and evaluation of the barriers to help seeking scale. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2005;6:95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Tucker JA, Donovan DM, Vuchinich RE. Help-seeking by substance abusers: The role of harm reduction and behavioral-economic approaches to facilitate treatment entry and retention. In: Onken LS, Blaine JD, Boren JJ, editors. Beyond the therapeutic alliance: Keeping the drug-dependent individual in treatment (NIDA Research Monograph No. 165) Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1997. pp. 44–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally AM, Palfai TP, Kahler CW. Motivational interventions for heavy drinking college students: Examining the role of discrepancy-related psychological processes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:79–87. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, McDevitt-Murphy ME, Barnett N. Drink and be merry? Gender, life satisfaction, and alcohol consumption among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:184–191. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal DJ, Carey KB. Developing discrepancy within self-regulation theory: Use of personalized normative feedback and personal strivings with heavy-drinking college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:281–297. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Palmer RS, Larimer ME. Interest and participation in a college student alcohol intervention study as a function of typical drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:736–740. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orford J, Kerr C, Copello A, Hodgson R, Alwyn T, Black R, Slegg G. Why people enter treatment for alcohol problems: Findings from UK alcohol treatment trial pre-treatment interviews. Journal of Substance Use. 2006;11:161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RS, Kilmer JR, Larimer ME. If you feed them will they come? The use of social marketing to increase interest in attending a college alcohol program. Journal of American College Health. 2006;55:47–52. doi: 10.3200/JACH.55.1.47-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JC, Heesacker M. College student admission of alcoholism and intention to change alcohol-related behavior. Journal of College Student Development. 1992;33:403–410. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Colder CR. Development and preliminary validation of the young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:169–177. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Merrill JE, Kahler CW, Strong DR. Predicting functional outcomes among college drinkers: Reliability and predictive validity of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2597–2610. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skidmore JR, Murphy JG. Relations between heavy drinking, gender, and substance-free reinforcement. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. doi: 10.1037/a0018513. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tevyaw TA, Borsari B, Colby SM, Monti PM. Peer Enhancement of a brief motivational intervention with mandated college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:114–119. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.1.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JA, King MP. Resolving alcohol and drug problems: Influences on addictive behavior change and help-seeking processes. In: Tucker JA, Donovan DM, Marlatt GA, editors. Changing addictive behavior: Bridging clinical and public health perspectives. New York: Guilford; 1999. pp. 97–126. [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Jaccard J, Taki R, Dunnam H, Grimes J. Examination of the short-term efficacy of a parent intervention to reduce college student drinking tendencies. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:366–372. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Larimer ME, Mallett KA, Kilmer JR, Ray AE, et al. A randomized clinical trial evaluating a combined alcohol intervention for high-risk college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:555–567. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Vader AM, Harris TR, Field CA, Jouriles EN. Dismantling motivational interviewing and feedback for college drinkers: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:64–73. doi: 10.1037/a0014472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in alcohol use, related problems and experience of prevention efforts among U.S. college students 1993–2001: Results from the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study. Journal of American College Health. 2002;5:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werch C. How much is enough? Willingness to participate in alcohol interventions. Journal of American College Health. 1991;39:269–274. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1991.9936244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Evans PC, Perfetti L. Attitudes toward seeking treatment among alcohol-using college students. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2003;29:671–690. doi: 10.1081/ada-120023464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]