Abstract

Cytomegalovirus (CMV)-associated gastroduodenal ulcers (GDU) are a rare digestive disease, which principally affect immunocompromised patients. We recently experienced CMV-associated GDU occurring in a seemingly immunocompetent patient. The rarity of such a condition was inimical to a correct clinical diagnosis.

A 77-year-old woman with Alzheimer's disease was admitted to our hospital because of vomiting and anorexia. Her general condition was extremely poor due to severe dehydration. Any invasive procedures including gastroduodenal endoscopy could not be performed. Laboratory test results showed electrolyte imbalance, hyperglycemia, and hypercortisolemia. The plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone level was rather low. On her 11th day in hospital, she suddenly fell into shock status. Despite intensive care, the patient could not be rescued. An autopsy was performed and revealed that she had suffered from CMV-associated GDU and died of candidemia that invaded through the ulcer. Her adrenal glands showed neither neoplasm nor hyperplasia, suggesting that her hypercortisolism was a purely functional disorder. We concluded that the severe opportunistic infections were developed in association with functional hypercortisolism.

This case suggests that functional hypercortisolism, even though transient, can cause a patient to be immunocompromised.

INTRODUCTION

Endogenous hypercortisolism usually presents in association with neoplastic or hyperplastic disorders, such as pituitary adenomas, ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-producing neoplasm, and adrenal tumors or hyperplasia.1 Its principal symptoms and signs are central obesity, hyperglycemia, hypertension, electrolyte imbalance, and so on, and are known as Cushing's disease or Cushing's syndrome.1 Excess endogenous steroids, as well as exogenous/iatrogenic ones, potentially induce opportunistic infections.2 Cortisol is primarily “the stress hormone.” Its secretion is increased via activation of hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis by diverse stresses. In critically ill patients, its secretion can reach abnormal levels.3 This pathophysiological phenomenon is known as functional hypercortisolism or pseudo-Cushing's syndrome, which can be differentiated from “true” Cushing's syndrome by a dexamethasone suppression test.4,5 Although it is considered a kind of adaptive reaction against severe stresses, it may introduce unfavorable effects to patients in the same manner as “true” Cushing's syndrome.6,7

Recently, we experienced a case of severe opportunistic infections associated with functional hypercortisolism. The patient died of candidiasis that superinfected on gastroduodenal ulcers (GDU) associated with cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. To our knowledge, this is the first case report of its kind. In the light of its clinical importance, we report herein this case.

CASE REPORT

A 77-year-old woman with Alzheimer's disease was admitted to our hospital because of vomiting and anorexia persisting for over a month. She had been managed as an outpatient of our hospital from January 2013 due to hiatal hernia and iron-deficiency anemia. GDU was suspected, but endoscopic examination revealed no lesions in her stomach and duodenum. Despite detailed examinations, an etiology of her iron-deficiency anemia was not determined. She was treated by transfusion and administration of iron supplements. Simultaneously, her Alzheimer's disease worsened, and oral intake of donepezil was initiated from November 2013. Subsequently, she complained of nausea, which was supposed to be attributed to donepezil, and rivastigmine patches were begun instead of donepezil. However, her sickness had become severe, and she developed uncontrollable anorexia and vomiting. She was admitted to our hospital on February 5, 2014.

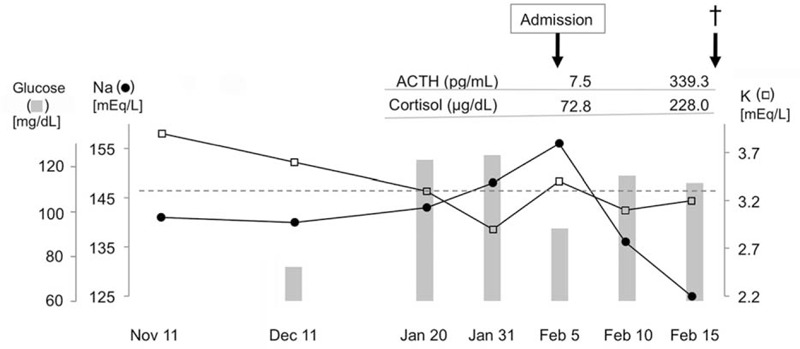

On admission, she appeared to be severely dehydrated and exhausted. Her abdomen was flat and soft, and no tenderness was found. The radiological examination revealed moderate amounts of ascites and pleural effusion besides already-known scoliosis and hiatal hernia. Laboratory test results demonstrated hypernatremia (156 mEq/L), hypokalemia (3.4 mEq/L), hypoalbuminemia (2.8 g/dL), and mild leukocytosis (9400/mm3). The physicians were aware that there had been electrolyte imbalance since 1 week ago and hyperglycemia appeared 2 weeks ago (Fig. 1). To identify the cause of these laboratory test abnormalities, hormonal tests were performed and revealed the elevated plasma cortisol level (78.2 μg/dL [normal range, 3.9–18.1 μg/dL]) accompanied by the low plasma ACTH level (7.5 pg/mL [normal range, 7.7–63.1 pg/mL]).

FIGURE 1.

Transitions in laboratory test results of the patient.

To alleviate the critical condition, the physicians decided to correct her dehydration and electrolyte imbalance first, and planned to perform a dexamethasone suppression test and detailed gastrointestinal examinations later. Needless to say, the rivastigmine patch was halted.

Although strict intravenous infusion therapy was continued, the patient's general condition and laboratory data did not improve. Oral intake was initiated on the 8th hospital day, but no nutritional efficacy was obtained. The amounts of ascites and pleural effusion progressively increased, and her respiratory condition worsened. On the 11th hospital day, she complained of severe abdominal pain, and suddenly fell into shock status. A markedly elevated serum level of C-reactive protein (11.73 mg/dL) suggested that she was suffering from a critical infectious/inflammatory disorder. At that time, both the plasma cortisol (228.0 μg/dL) and ACTH (339.3 pg/mL) levels were remarkably elevated (Fig. 1). Antibiotic administration was immediately instituted, but we could not rescue the patient. An autopsy was performed to clarify what had happened in her body during these couple of months.

METHODS AND PATHOLOGIC FINDINGS

The autopsy was performed 3 h postmortem. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's family, and this case study was approved by the hospital ethical committee. First, a blood specimen was obtained aseptically and examined on bacterial culture. Then, every thoraco-abdominal organ was removed, examined macroscopically, and fixed in buffered formalin. Paraffin-embedded tissue specimens were sectioned in 3 μm thick and stained with hematoxylin-eosin, periodic acid-Schiff, and immunoperoxidase for cytomegalovirus (Dakopatts, Glostrup, Denmark).

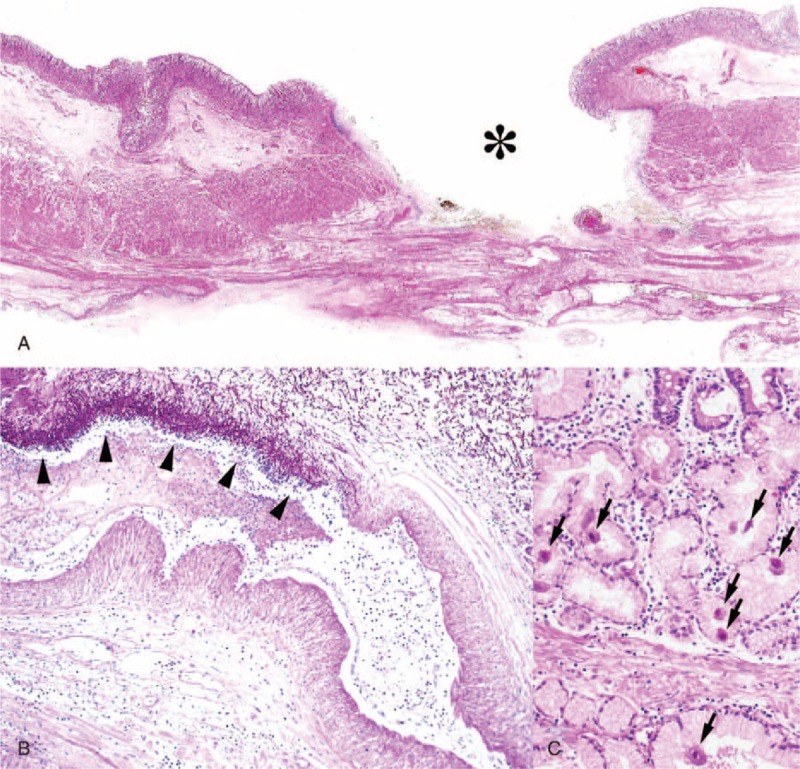

The autopsy findings, including results of the blood culture, indicated that the cause of her death was candidemia. Macroscopic examination revealed multiple deep GDU in her gastric antrum and duodenal bulb. Candida albicans had invaded into the bloodstream via exposed vessels in the lesions of GDU, which was associated with CMV infection (Fig. 2). CMV-infected cells were also seen in the lungs, colon, uterus, and lymph nodes. The CMV infection was confirmed immunohistochemically (not shown). No neoplastic/hyperplastic changes were found in any examined organs including adrenal glands (Fig. 3), suggesting that her hypercortisolism was a purely functional disorder.

FIGURE 2.

Histopathological findings at autopsy. (A) A deep gastric ulcer (asterisk) associated with fungal colonization (hematoxylin-eosin; loupe magnification). (B) Fungi invading the vascular lumen (arrowheads) in the ulcer bed (periodic acid-Schiff stain; low magnification). (C) Many CMV-infected cells (arrows) in mucosa adjacent to the ulcer (hematoxylin-eosin; high magnification).

FIGURE 3.

Cut-surfaces of the adrenal glands. No neoplastic/hyperplastic changes are seen.

Final pathologic diagnoses were: (1) functional hypercortisolism (pseudo-Cushing's syndrome), (2) CMV-associated GDU, and (3) candida superinfection in GDU and candidemia (cause of death).

DISCUSSION

Unfortunately, we could not rescue the patient. To convert this negative experience to future success, we thoroughly reviewed the clinical and pathological findings, guessed the pathophysiology, and pondered how we should have managed the patient.

The patient presented with severe exhaustion, dehydration, and cause-undetermined hypercortisolism. Detailed endocrinological examinations were planned but could not be performed because her general condition rapidly worsened. No diagnostic procedures and radical therapies could be done, and all our treatment approaches to her were conservative and symptomatic. She suddenly fell into shock and died, and during this short period we couldn’t understand what had happened. The post-mortem examination revealed that the patient had died of candidemia that had occurred as an unimaginable incidental complication of CMV-associated GDU (Fig. 2). We were surprised that such seemingly immunocompetent patient suffered from the severe opportunistic infections.

In general, it is recognized that CMV-associated GDU is caused mostly in immunocompromised patients, especially patients receiving immunosuppressive therapies.8,9 Alternatively, there are several reports of CMV-associated GDU developed in immunocompetent patients.10–13 However, since their precise immune conditions were not fully examined, they might have been in immunocompromised settings. In our patient, hypercortisolism possibly affected her immune condition and contributed to development of the life-threatening opportunistic infections. Her hypercortisolism at least was related to worsening of the infectious disorders. In fact, endogenous hypercortisolism is considered an important etiologic factor in immunosuppression.2

As described above, endogenous hypercortisolism is usually associated with neoplastic or hyperplastic disorders. Our patient's hypercortisolism was considered a purely functional disorder, namely pseudo-Cushing syndrome. Anorexia, probably adverse effects of donepezil and the use of rivastigmine patches,14 is thought to have been strongly stressful for her both physically and psychologically. This highly stressful condition continued for a couple of months and was thought to have led to increased cortisol secretion via activation of hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis.7,15 A dexamethasone suppression test would have clarified and classified her raised adrenocortical activity.4,5

Functional hypercortisolism has been considered a secondary disorder that is induced in association with anorexia, diabetes, alcoholism, and critically ill conditions, and so on.7,15 Hence this has not been a subject for active therapeutic interventions. However, accumulating evidence has revealed its harmful effects comparable with those of true Cushing syndrome and benefits of correction of the patients’ plasma cortisol levels.6,7 We should have considered an active hormonal intervention when we noticed her hypercortisolism.

A more critical issue during the hospitalization was the insufficient gastrointestinal examination. If gastroduodenal endoscopy had been repeatedly carried out, we would have found the GDU and made a correct diagnosis in time. In actual fact, her severe general condition did not allow us to perform detailed gastrointestinal examinations. Moreover, treatment of CMV-associated GDU requires antiviral drugs,16,17 which cannot be used without pathologic evidence of CMV infection shown in gastroduodenal biopsy specimens. A chance of making a correct diagnosis and choosing curable treatments is thought to have been extremely low. Premortem diagnosis of CMV-associated GDU in a patient in a severe condition is quite difficult even by modern medical technologies.18

In conclusion, we experienced CMV-associated GDU caused in a patient with functional hypercortisolism. This case suggested that functional hypercortisolism, even though transient, can cause a patient to become immunocompromised. Functional hypercortisolism is considered a subject of active therapeutic interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank Dr. J. Aidan Carney, Emeritus Professor of Pathology, Mayo Clinic, for giving valuable comments on adrenal gland pathology.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ACTH = adrenocorticotropic hormone, CMV = cytomegalovirus, GDU = gastroduodenal ulcers.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maitra A. Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC, Perkins JA. Adrenocortical Hyperfunction (Hyperadrenalism). Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease (9th ed). Philadelphia, PA:Elsevier Saunders; 2015. 1123–1129. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lionakis MS, Kontoyiannis DP. Glucocorticoids and invasive fungal infections. Lancet 2003; 362:1828–1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vermes I, Beishuizen A. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal response to critical illness. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001; 15:495–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gatta B, Chabre O, Cortet C, et al. Reevaluation of the combined dexamethasone suppression-corticotropin-releasing hormone test for differentiation of mild cushing's disease from pseudo-Cushing's syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007; 92:4290–4293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alwani RA, Schmit Jongbloed LW, de Jong FH, et al. Differentiating between Cushing's disease and pseudo-Cushing's syndrome: comparison of four tests. Eur J Endocrinol 2014; 170:477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kem DC, Metcalf JP, Cornea A, et al. Is pseudo-Cushing's syndrome in a critically ill patient “pseudo”? Hypothesis and supportive case report. Endocr Pract 2007; 13:153–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tirabassi G, Boscaro M, Arnaldi G. Harmful effects of functional hypercortisolism: a working hypothesis. Endocrine 2014; 46:370–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoshino K, Shibata D, Miyagi T, et al. Cytomegalovirus-associated gastric ulcers in a patient with dermatomyositis treated with steroid and cyclophosphamide pulse therapy. Endoscopy 2011; 43 Suppl 2:E277–E278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tamura J, Arakaki S, Shibata D, et al. Cytomegalovirus-associated gastric ulcer: a diagnostic challenge in a patient of fulminant hepatitis with steroid pulse therapy. BMJ Case Rep 2013; 2013: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnar DO, Gudmundsson G, Theodors A, et al. Primary cytomegalovirus infection and gastric ulcers in normal host. Dig Dis Sci 1991; 36:108–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinoshita Y, Tojo M, Yano T, et al. Cytomegalovirus mononucleosis-associated gastric ulcers in normal host. Gastroenterol Jpn 1993; 28:88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshinaga M, Nakate S, Motomura S, et al. Cytomegalovirus-associated gastric ulcerations in a normal host. Am J Gastroenterol 1994; 89:448–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suzuki M, Ochi Y, Hosokawa S, et al. A multiple gastric ulcer case caused by cytomegalovirus infection. Tokushima J Exp Med 1996; 43:173–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pratt RD, Perdomo CA, Surick IW, et al. Donepezil: tolerability and safety in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Clin Pract 2002; 56:710–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawson EA, Donoho D, Miller KK, et al. Hypercortisolemia is associated with severity of bone loss and depression in hypothalamic amenorrhea and anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 94:4710–4716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howaizi M, Abboura M, Sbai-Idrissi MS, et al. Cytomegalovirus-associated perforated gastric ulcer healing under antiviral therapy. Dig Dis Sci 2002; 47:2380–2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monrobel A, Chicano M, Navarrese A, et al. Gastrointestinal affectation with cytomegalovirus in an immunocompetent patient. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2006; 98:881–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell DA, Piercey JR, Shnitka TK, et al. Cytomegalovirus-associated gastric ulcer. Gastroenterology 1977; 72:533–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]