Abstract

Patient: Female, 60

Final Diagnosis: UPSC with adrenal metastasis

Symptoms: Post menopausal bleeding

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Adrenalectomy

Specialty: Oncology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC) is a highly malignant form of endometrial cancer with a high propensity for metastases and recurrences even when there is minimal or no myometrial invasion. It usually metastasizes to the pelvis, retroperitoneal lymph nodes, upper abdomen, and peritoneum. However, adrenal metastases from UPSC is extremely rare. Here, we present a case of UPSC with adrenal metastasis that occurred 6 years after the initial diagnosis.

Case Report:

A 60-year-old woman previously diagnosed with uterine papillary serous carcinoma at an outside facility presented in September of 2006 with postmenopausal bleeding. She underwent comprehensive surgical staging with FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) stage 2. Post-operatively, the patient was treated with radiation and chemotherapy. The treatment was completed in April of 2007. The patient had no evidence of disease until July 2009 when she was found to have a mass highly suspicious for malignancy. Subsequently, she underwent right upper lobectomy. The morphology of the carcinoma was consistent with UPSC. She refused chemotherapy due to a previous history of chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. The patient was followed up with regular computed tomography (CT) scans. In October 2012 a new right adrenal nodule was seen on CT, which showed intense metabolic uptake on positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan. The patient underwent right adrenalectomy. Pathology of the surgical specimen was consistent with UPSC.

Conclusions:

UPSC is an aggressive variant of endometrial cancer associated with high recurrence rate and poor prognoses. Long-term follow-up is needed because there is a possibility of late metastases, as in this case.

MeSH Keywords: Adrenalectomy, Neoplasm Metastasis, Uterine Neoplasms

Background

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy and the second most common cause of death from gynecologic cancers. It is estimated that there were 52 630 cases of uterine cancer in the United States in 2014, resulting in 8590 deaths [1]. Uterine adenocarcinoma is a morphologically heterogeneous group of neoplasms. The most common (80–90%) are type I, or endometrioid; Type II poorly differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinomas are less common. Type II comprises clear cell and serous cell types [2]. Uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC) was first described by Hendrickson et al. in 1982 as a highly malignant form of endometrial cancer [3].

UPSC is characterized by p53 gene mutations, p16 gene inactivation, low E-cadherin expression, and HER-2/neu overexpression. UPSC, unlike Type I endometrioid adenocarcinoma, arises in the background of atrophic endometrium and has not been found to have significant association with endocrine and metabolic abnormalities like diabetes, obesity, excess estrogen supplementation, or thyroid diseases [4].

The tumor has a high propensity for metastases and recurrences even when there is minimal or no myometrial invasion [5]. Metastases from gynecological neoplasms to the adrenals are uncommon. The primary tumors that metastasize to the adrenals, in order of frequency, are lung cancer, breast cancer, gastrointestinal tumors, malignant melanoma, and thyroid neoplasms [6]. UPSC has been reported to metastasize to the pericardium [7], abdominal wall [8], skin [9], and brain [10]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no report in the English literature of adrenal metastasis that developed from UPSC. Here, we present a case of UPSC in a 60-year-old woman who developed adrenal metastases 6 years after initial diagnosis.

Case Report

A 60-year-old Trinidadian woman presented in September of 2006 with a history of postmenopausal bleeding of several weeks’ duration. She had undergone an endometrial biopsy in August of 2006 at an outside facility, which revealed uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC). Her physical examination was unremarkable. In October of 2006, the patient underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy, and omentectomy. Biopsies of the left and right diaphragms and the pelvis were taken. Intra-operative findings did not reveal any evidence of tumor beyond the uterus. The pathology findings were consistent with UPSC with 1.5 cm of myometrial invasion. The tumor extended to the glandular epithelium of the endocervix and was 1.6 cm from the ectocervical resection margin. Lymphovascular invasion was indeterminate. The rest of the staging pathology specimens were negative, FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) stage 2. Cancer antigen (CA) 125 were within normal limits prior to and after the surgery.

Postoperatively, the patient was treated with external radiation therapy to the pelvis as well as brachytherapy to the vagina. Following completion of radiation therapy, the patient received 3 cycles of chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel. The treatment was completed in April 2007. A follow-up nuclear whole-body scan showed no evidence of skeletal metastatic disease.

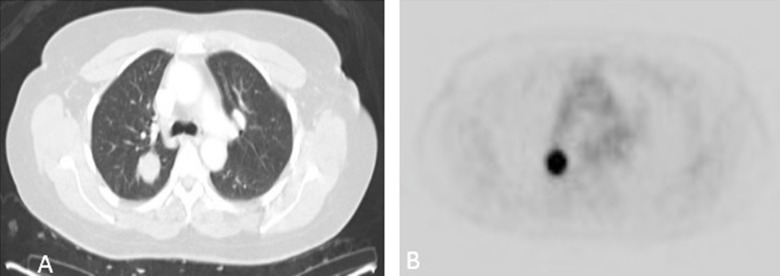

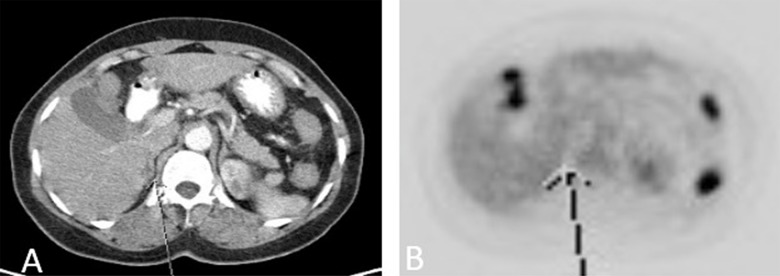

The patient had no evidence of disease until July 2009, when she was admitted due to abdominal pain. The abdomen/pelvis CT showed a lobulated mass in the right upper lobe measuring 2.5×2.2×2.2 cm, which was confirmed with chest CT. A whole-body PET scan in August 2009 showed a 2-[fluorine-18] fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose (FDG) avid 2.3 cm right upper-lung nodule highly suspicious for malignancy. The rest of the PET CT was negative (Figure 1A, 1B).

Figure 1.

(A, B) Metabolically active right lung nodule seen on PET/CT obtained 3 years after diagnosis and surgery for endometrial cancer.

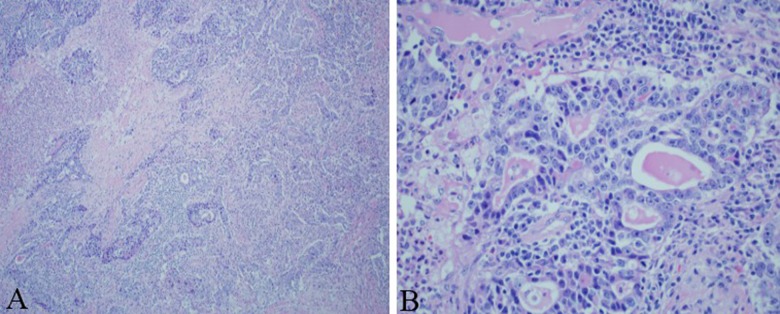

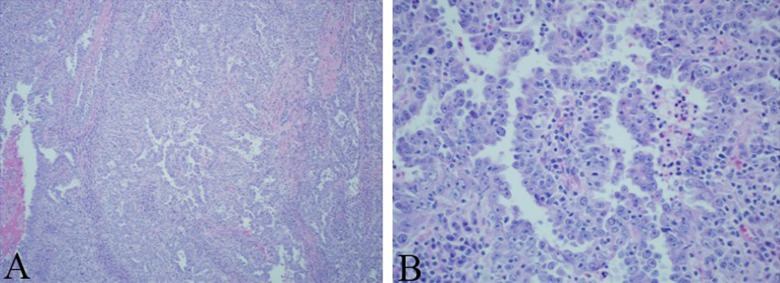

The patient underwent right upper lobectomy, and the morphology of the surgical specimen was consistent with UPSC (Figure 2A, 2B). Chemotherapy with another 3 cycles of paclitaxel and carboplatin was planned postoperatively, but the patient refused.

Figure 2.

(A) Low power and (B) high power: Right upper lobectomy surgical specimen revealing pathology consistent with UPSC.

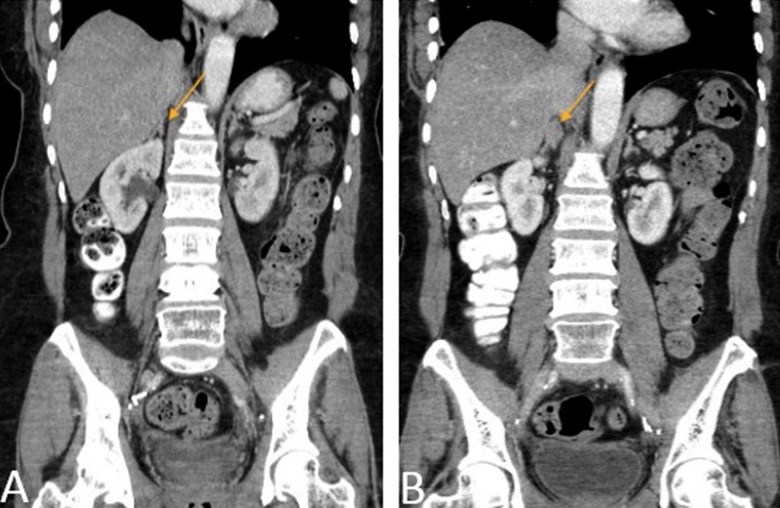

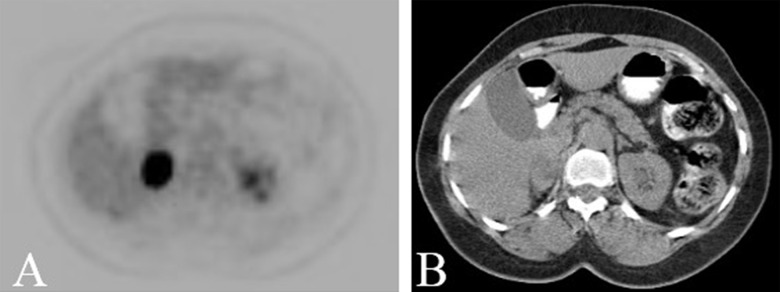

The patient was followed up with regular CT scans. In October 2012, a new right adrenal nodule measuring 1.4 cm was seen on CT (Figure 3A, 3B). PET/CT showed intense metabolic uptake in the right adrenal mass measuring 2.3×3.5 cm (Figure 4A, 4B). PET/CT done in August 2009 did not show any metabolic or anatomic abnormality (Figure 5A, 5B). Pheochromocytoma was ruled out and the patient underwent right adrenalectomy in April 2013. Pathology of the surgical specimen was consistent with UPSC (Figure 6A, 6B). The patient was offered chemotherapy postoperatively, but she again refused.

Figure 3.

(A, B) Coronal reformatted CT images obtained approximately 3 and 6 years, respectively, after initial diagnosis of endometrial cancer, demonstrates a new right adrenal nodule (orange arrow).

Figure 4.

(A, B): PET/CT demonstrates a metabolically active right adrenal nodule. This had grown in size and was significantly more intense than hepatic background and was consistent with malignancy.

Figure 5.

(A, B): The right adrenal demonstrates no metabolic or anatomic abnormality in right adrenal on this PET/CT obtained 3 years after initial diagnosis (arrow).

Figure 6.

(A) Low power and (B) high power: Right adrenalectomy surgical specimen revealing pathology consistent with UPSC.

On the follow-up CT in September 2013, a 1.5-cm soft tissue attenuation focus at the upper pole of the right kidney was seen. It was reported to be a postoperative change versus metastatic disease. The patient continued to refuse chemotherapy and follow-up imaging studies. A PET scan in March 2014 showed intense metabolic uptake in the post-surgical bed of the right adrenalectomy site and in soft tissue nodules along the right psoas/quadrates muscle not seen on the prior PET scan, consistent with metastatic deposits. The patient agreed to palliative chemotherapy with carboplatin/Taxotere/Neulasta.

She received the first cycle of chemotherapy in May 2014 but refused any further chemotherapy secondary to the adverse effects of the chemotherapy. She returned to her home country to be with her family.

Discussion

Uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC) was first described by Hendrickson et al. in 1982 as a particularly virulent histologic type of endometrial cancer [3]. UPSC is unique because of its distinct clinicopathological behavior, which distinguishes it from type I endometrioid adenocarcinoma. It tends to occur in postmenopausal women with a median age of 62 years, which is older than the reported median age of women with endometrioid carcinoma. Most frequently (60–70%), patients with UPSC present with disease outside the uterus [4]. UPSC accounts for approximately 10% of the cases of uterine cancers, but is responsible for more than 50% of the relapses and deaths in endometrial cancers [2].

UPSC histologically and clinically resembles ovarian papillary serous tumors. UPSC typically has a papillary growth pattern with tufted stratification and sometimes hobnail configuration. It has a high degree of cytologic anaplasia [3]. Psammoma bodies are found in 60% of UPSC cases; however, their absence does not rule out UPSC. Tumor necrosis is often a prominent feature. Lymphovascular invasion is common [2].

The pattern of spread of UPSC is prominently via lymphovascular invasion [3]. It usually metastasizes to the pelvis, retroperitoneal lymph nodes, and upper abdomen and has peritoneal spread. However, adrenal metastases from UPSC is extremely rare [11]. The primary tumors that metastasize to the adrenals, in order of frequency, are lung cancer, breast cancer, gastrointestinal tumors, malignant melanoma, and thyroid neoplasms [6]. An extensive search of the literature found no report of UPSC metastasizing to the adrenals.

Because UPSC histologically and clinically resembles ovarian papillary serous tumors, metastatic UPSC is difficult to distinguish from metastatic ovarian serous carcinoma. In the present case, the histopathology finding of the surgical specimen of the ovary was negative. Histopathology findings of the metastatic adrenal lesions showed a pattern similar to uterine carcinoma, which suggests the diagnoses of the adrenal lesion as metastatic UPSC.

It is recommended that patients with UPSC receive multimodal treatment consisting of adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy to reduce the risk of recurrence and to prolong survival. Surgery is the initial part of the management of both early-stage (for comprehensive staging) and advanced-stage disease (as a debulking procedure). Since metastases occur even in the absence of myometrial invasion or lymphovascular space involvement, patients should undergo comprehensive surgical staging. Most patients tend to be upstaged after a comprehensive surgical staging [4]. Hui et al. reported that out of 21 patients who had the tumor confined to a polyp, 8 (38%) had extrauterine disease [12]. Growdon et al., in a study of 84 patients with clinical stage I UPSC, reported that women undergoing comprehensive surgical staging had survival benefits compared to women who underwent only hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (16.4 years vs. 2.76 years, respectively; P<0.0001) [13]. Mixed tumors containing any UPSC element have similar clinical behavior as pure UPSC [2]. Therefore, comprehensive surgical staging is recommended even in cases of mixed tumors. For advanced-stage UPSC, maximum cytoreduction should be performed at the time of primary surgery because studies have demonstrated survival benefits with optimal surgical resection [4].

Feder et al. found that platinum/taxane-based chemotherapy significantly improved the recurrence and overall survival rates in 59 out of 95 women with surgical stage I UPSC. Addition of radiation therapy to chemotherapy in another 36 out of 95 patients did not reduce the risk of recurrence [14]. Feder et al., in a retrospective study of 55 women with stage II UPSC, reported that the recurrence rate in women treated with adjuvant chemotherapy ± radiation therapy was 11%, in contrast to 50% in women treated with radiation alone (p=0.013) [15]. Hoskins et al., in a study of 19 subjects, reported that advanced or recurrent UPSC has a response rate of 60% and 50%, respectively, when treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel with or without radiation therapy [16]. Gehrig et al. reported that radiation therapy appears to control locoregional recurrence [17]. We therefore recommend multimodal treatment with adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy in advanced-stage UPSC.

Since stage is the strongest prognostic variable, meticulous surgical staging is important for predicting the prognosis of UPSC. Slomovitz et al., in their review of 129 patients with UPSC, reported 5-year survival rates of 62.9%, 37.3%, and 19.9% for stages I, III, and IV (P<0.01), and 60.5% and 26.3% for negative nodes and positive nodes, respectively [18].

Long-term follow-up is needed due to the highly recurrent behavior of this tumor. In a retrospective study of 119 patients with diagnoses of UPSC by Huang et al., 40% of the patients (n=48) experienced recurrence even after receiving postoperative adjuvant therapy consisting of radiation, chemotherapy, or a combination of both [19]. CT is widely used for surveillance following treatment with surgery and chemotherapy/radiation therapy. CT reliably distinguishes an adrenal mass as benign or metastatic. However, size >50 mm, growing mass on follow-up CT scan, and invasion into adjacent tissue can help to distinguish a malignant lesion from adenoma. F-FDG PET has a sensitivity of 100%, a specificity of 94%, and an accuracy of 96% in differentiating benign from metastatic adrenal lesions detected on CT [6].

Conclusions

UPSC is an aggressive variant of endometrial cancer associated with high recurrence rate and poor prognoses. Optimum cytoreductive surgery along with platinum and taxane-based chemotherapy appears to improve outcome and survival in patients with UPSC. Systemic chemotherapy should be administered as a post-operative adjuvant therapy even when UPSC is confined to the endometrium without regional lymph node spread or lymphovascular invasion. The present case also emphasizes the aggressive behavior of this variant of endometrial adenocarcinoma, along with the need for long-term follow-up due to the possibility of late metastasis.

Footnotes

Statement

There are no financial grants or funding sources to declare. There is no conflict of interest for the authors of this manuscript.

References:

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naumann RW. Uterine papillary serous carcinoma: state of the state. Curr Oncol Rep. 2008;10(6):505–11. doi: 10.1007/s11912-008-0076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hendrickson M, Ross J, Eifel P, et al. Uterine papillary serous carcinoma: a highly malignant form of endometrial adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1982;6(2):93–108. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198203000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.del Carmen MG, Birrer M, Schorge JO. Uterine papillary serous cancer: a review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127(3):651–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bokhman JV. Two pathogenetic types of endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1983;15(1):10–17. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(83)90111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baron M, Hamou L, Laberge S, et al. Metastatic spread of gynaecological neoplasms to the adrenal gland: case reports with a review of the literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2008;29(5):523–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramirez PT, Ramondetta LM, Burke TW, et al. Metastatic uterine papillary serous carcinoma to the pericardium. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;83(1):135–37. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park JW, Hwang SO. Abdominal wall metastasis of uterine papillary serous carcinoma in a post-menopausal woman: a case report. J Menopausal Med. 2014;20(1):35–38. doi: 10.6118/jmm.2014.20.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim ES, Lee DP, Lee MW, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27(5):436–38. doi: 10.1097/01.dad.0000178002.19337.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gulsen S, Terzi A. Multiple brain metastases in a patient with uterine papillary serous adenocarcinoma: Treatment options for this rarely seen metastatic brain tumor. Surg Neurol Int. 2013;4:111. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.117176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicklin JL, Copeland LJ. Endometrial papillary serous carcinoma: patterns of spread and treatment. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1996;39(3):686–95. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199609000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hui P, Kelly M, O’Malley DM, et al. Minimal uterine serous carcinoma: a clinicopathological study of 40 cases. Mod Pathol. 2005;18(1):75–82. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Growdon WB, Rauh-Hain JJ, Cordon A, et al. Prognostic determinants in patients with stage I uterine papillary serous carcinoma: a 15-year multi-institutional review. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012;22(3):417–24. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31823c6e36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fader AN, Drake RD, O’Malley DM, et al. Platinum/taxane-based chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy favorably impacts survival outcomes in stage I uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Cancer. 2009;115(10):2119–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fader AN, Nagel C, Axtell AE, et al. Stage II uterine papillary serous carcinoma: Carboplatin/paclitaxel chemotherapy improves recurrence and survival outcomes. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112(3):558–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoskins PJ, Swenerton KD, Pike JA, et al. Paclitaxel and carboplatin, alone or with irradiation, in advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer: a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(20):4048–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.20.4048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gehrig PA, Morris DE, Van Le L. Uterine serous carcinoma: a comparison of therapy for advanced-stage disease. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004;14(3):515–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1048-891x.2004.14313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slomovitz BM, Burke TW, Eifel PJ, et al. Uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC): a single institution review of 129 cases. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;91(3):463–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang CY, Tang YH, Chiang YC, et al. Impact of management on the prognosis of pure uterine papillary serous cancer – a Taiwanese Gynecologic Oncology Group (TGOG) study. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;133(2):221–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]