Abstract

Library methods are widely used to study protein-protein interactions, and high-throughput screening or selection followed by sequencing can identify a large number of peptide ligands for a protein target. In this chapter we describe a procedure called "SORTCERY" that can rank the affinities of library members for a target with high accuracy. SORTCERY follows a three-step protocol. First, fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) is used to sort a library of yeast displayed peptide ligands according to their affinities for a target. Second, all sorted pools are deep sequenced. Third, the resulting data are analyzed to create a ranking. We demonstrate an application of SORTCERY to the problem of ranking peptide ligands for the anti-apoptotic regulator Bcl-xL.

Keywords: yeast surface display, deep sequencing, high-throughput assay, protein-protein interaction, Bcl-2 family

1. Introduction

High-throughput analysis of functional mutations in proteins, peptides or DNA by deep sequencing is emerging as a powerful technique. Properties such as protein stability, enzymatic activity and peptide ligand or DNA binding have been studied [1–16]. The general approach involves screening a library of mutants or performing a selection for a desired function. Library sequences in pre- and post-selected pools are then identified by next-generation sequencing, and computational routines are used to extract information about how sequence relates to function.

Many selection or screening processes have been employed for these types of studies, including in vitro assays, phage display, yeast-surface display in combination with fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS), and in vivo assays. Some studies have used the observed frequencies of mutant variants in selected pools to infer sequence-function relationships [1–5]. As an alternative measure, enrichment scores have been calculated from the ratio of pre- and post-selection frequencies [6–14]. The effects of mutations in particular sequence positions have been investigated, either by experimentally screening single-mutant libraries or by assuming positional independence during computational post-processing. Position weight matrices have been built that score binding, stability, and function from sequence using this approach, sometimes with correction for non-specific binding or consideration of enrichment changes over multiple selection rounds [5,12,13]. Analyzing single-residue substitutions benefits from enhanced statistical power, because it is easy to saturate a single-position sequence space. But important context dependent effects may be neglected in this type of analysis.

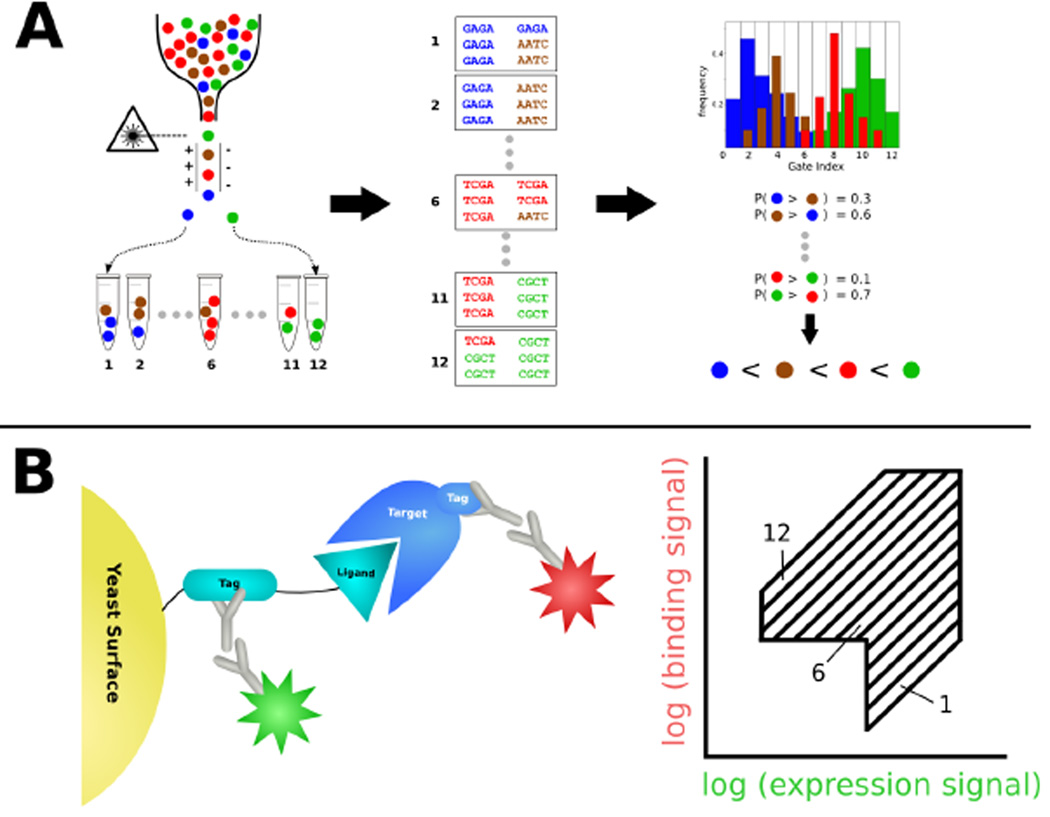

In this chapter we introduce a high-accuracy alternative to enrichment-based methods for probing mutational effects on the affinity of peptide ligands. Our protocol “SORTCERY” comprises the three steps of selection, deep sequencing and computational analysis (Figure 1 A). The selection process involves two-color cell sorting of a yeast-surface displayed library based on the expression levels of displayed peptides and levels of binding to a target (Figure 1 B). Our sorting protocol builds on reports that two-color FACS can accurately distinguish between binders of different affinities [15–19] and agrees with a theoretical model describing the expected signals for clones expressing peptides with a range of binding strengths [20]. This model can guide sorting of a library into pools according to binding affinity, and the pools can then be deep-sequenced to obtain information about individual library member affinities. SORTCERY extracts information from deep-sequenced library pools using computational routines that rank observed mutant sequences according to binding strength.

Figure 1.

A) SORTCERY combines experimental and computational protocols to rank peptide ligands according to their affinity for a target. Yeast-displayed peptides are sorted into pools that include ligands of similar affinity using FACS. Deep sequencing information is generated for each sample and the distribution of each sequence over the FACS gates is determined. Pairwise comparison of distributions permits the calculation of the probability that one peptide binds more strongly than another for each pair of peptides. A global rank order of affinities is computed from the probabilities. B) SORTCERY's yeast-display and gate-setting scheme. Peptide expression and target binding are detected via tags that are recognized by pairs of primary and fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies. Two-color cell sorting is based on these two signals. Gates are set to optimally separate binders of different affinities and to exclude non-binders and non-expressing cells.

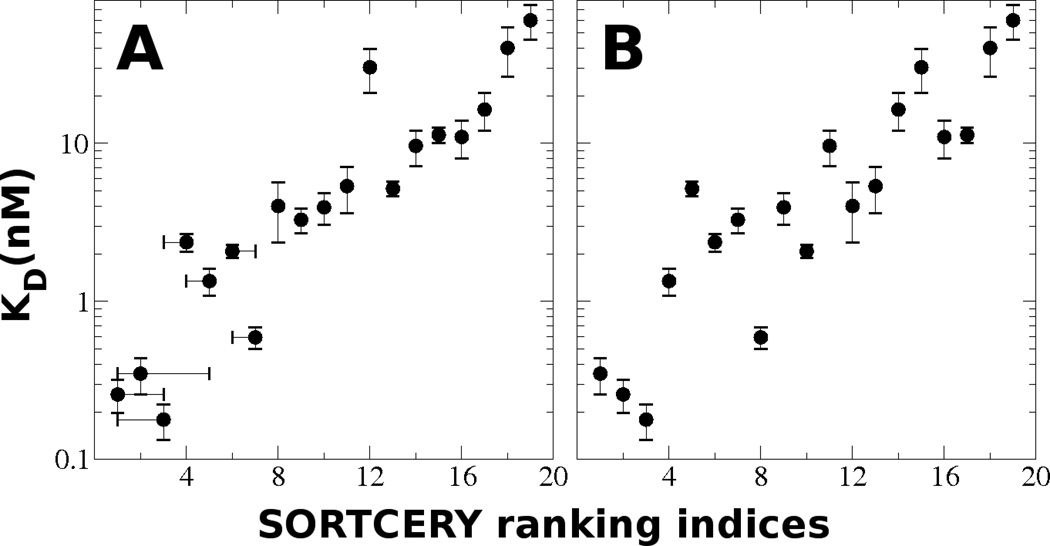

Applying SORTCERY to study helical peptide affinities for the apoptosis-regulating protein Bcl-xL, we obtained extremely accurate rankings for ~1000 sequences over a range of dissociation constants from 0.1 nM to 60 nM (Figure 2 A). Our study is described in reference [20] and the reader is referred to that paper for in-depth exposition of the theory underlying SORTCERY, the results when applied to Bcl-xL, and further discussion of strengths and limitations of this method. A special variant of our approach is described here (Figure 2 B, Note 9), that can potentially be used to analyze much larger libraries.

Figure 2.

A) Individually measured dissociation constants vs. SORTCERY ranking indices for 19 sequences from a ranking of ~1000 sequences. Clones have been reindexed from 1 to 19. Error bars for rank indices are 95% bootstrap confidence intervals: error bars for dissociation constants indicate standard deviations for four individual measurements. B) Ranking indices for the same 19 clones as determined by convoluted SORTCERY (see Note 9).

2. Materials

2.1. Cell Culture Media

SD+CAA/SG+CAA: Dissolve 5 g casamino acids, 1.7 g yeast nitrogen base, 5.3 g ammonium sulfate, 10.2 g Na2HPO4-7H2O and 8.6 g NaH2PO4-H2O in 700 ml water and autoclave for 15 min at 22 psi and 120 °C. For growth media (SD + CAA), dissolve 50 g glucose in 50 ml water then sterilize with a 0.2 µm filter. Add 40 ml of this 50% glucose solution to the autoclaved media and fill up to 1 l with sterile water. For induction media (SG + CAA), dissolve 20 g galactose in 100 ml water then sterilize with a 0.2 µm filter. Add 100 ml of this 20% galactose solution to the autoclaved media and fill up to 1 l with sterile water.

2.2 Fluorescence activated cell sorting

Low protein binding 0.45 µm filter plates or bottle-top filters

BSS pH 8.0: 50 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mg/ml BSA

Primary antibody mixture: anti-HA (Roche) 1:100 dilution and anti-Myc (Sigma) 1:100 dilution in BSS

Secondary antibody mixture: APC-labeled anti-mouse (BD Biosciences) 1:40 dilution and PE-labeled anti-rabbit (Sigma) 1:100 dilution in BSS

2.3 Deep Sequencing Sample Preparation (see Note 1)

Zymoprep Yeast Plasmid Miniprep I (Zymo Research)

Isopropanole

High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (e.g. Phusion)

Thermocycler

Gel equipment

PCR purification and gel extraction kits (QiaGen)

MmeI (New England Biolabs): MmeI restriction enzyme, NEB Cut Smart Buffer, 1 mM SAM

T4 Ligase

Primers and oligos

3. Methods

3.1 Cell growth and induction of yeast-surface display library (see Note 2)

Dilute cells to OD600 of 0.05 in SD + CAA and grow for 8 h at 30 °C.

Dilute cells to OD600 of 0.005 in SD + CAA and grow to OD of 0.1 – 0.4 at 30 °C.

Dilute cells to OD600 of 0.025 in SG + CAA and grow to OD of 0.2 – 0.5 at 30 °C for induction of peptide expression.

3.2 Gate setting

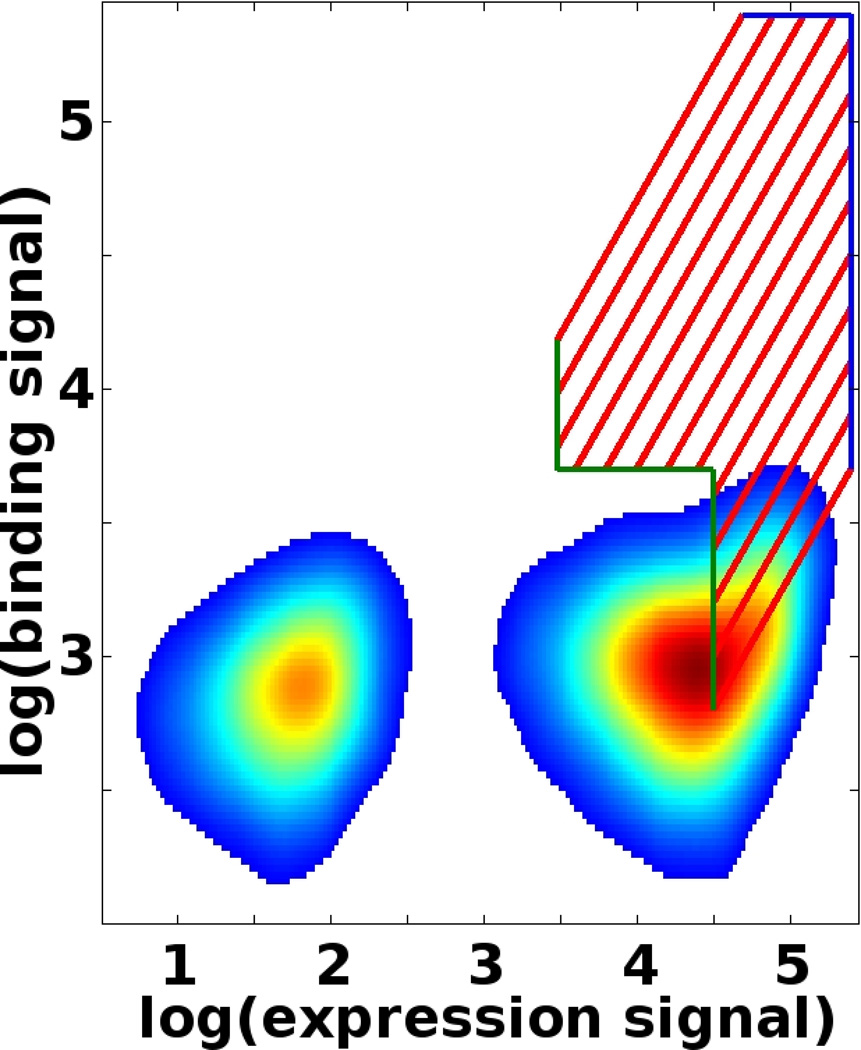

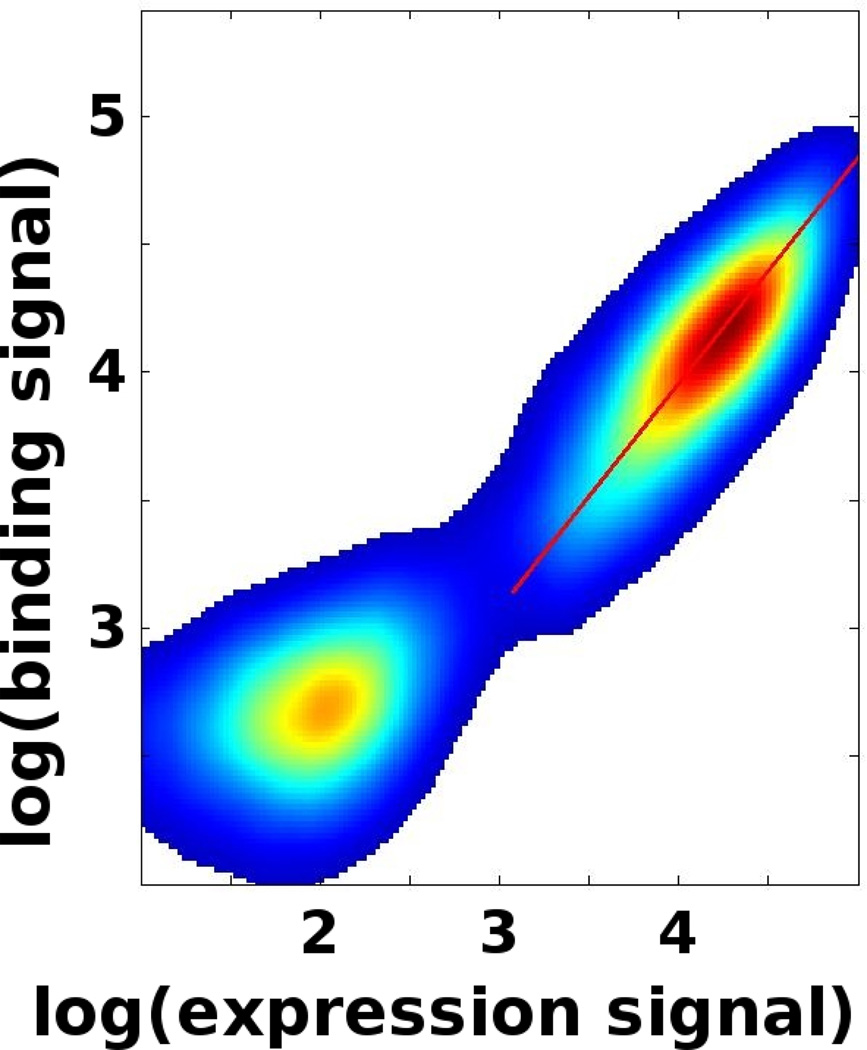

SORTCERY uses a two-color FACS setup to monitor expression (Fe) and binding (Fb) signals on a log/log or biexponential scale. On a log(Fb) vs. log(Fe) plot, points of equal binding strength lie on a line with a slope of 1 [20]. Subdivide the log/log plot accordingly into areas (gates) of different affinities by dissecting it with lines of slopes of 1 (red lines in Figure 3). The number, position and spacing of the lines will affect the performance of the procedure. We recommend an equal spacing between lines as this will result in optimal resolution between binders of different affinities. The number of lines (and the resulting gates) depends on the required resolution. This can be determined by measuring the FACS profiles of several yeast-displayed standards (see Note 3). Lines should be positioned such that the gates cover an area from the strongest binders to the baseline signal of binding. FACS profiles of standards can help determine whether the experimental setup will generate samples with quality appropriate for a SORTCERY sort (see Note 4).

Gate boundaries should be set to exclude cells without significant expression signal and to prevent cells in the binding baseline from being captured in gates for higher affinities. Cutoffs can be established by monitoring the FACS profile of a non-binding yeast clone and noting: (1) the position of non-expressing cells (blob in the lower left corner of Figure 3), and (2) the binding baseline (lower right area in Figure 3). Determine appropriate cutoffs and set gate lower-edge boundaries accordingly (see example: green edges in Figure 3).

Cell sorters assign maximum signal values to any signal intensity above their scale of measurement. Such signals have, therefore, not been accurately determined. Exclude the maximum expression and binding signal areas from the gates by setting gate boundaries accordingly (see example: blue edges in Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Gate-setting for an affinity sort with 12 gates. The red, diagonal lines subdivide the axis of affinity into different intervals and thus insure that each gate corresponds to a unique range of dissociation constants. The green, lower- left borders exclude non-binding cells from higher-affinity gates and exclude non-expressing cells from all gates. The depicted FACS profile of a non-binder illustrates this. The blue, upper-right borders exclude cells with the maximum possible expression or binding signal, because affinities cannot be accurately estimated from such signals.

3.3 Cell sorting

Filter grown and induced yeast cells (step 3.1) and wash twice with BSS.

Incubate cells with target molecule in BSS for 2 h at 21 °C (see Notes 5 & 6). Shake gently during incubation.

Filter cells and wash twice with BSS.

Incubate with mixture of primary antibodies (20 µl per 106 cells, see Notes 7 & 8) at 4 °C.

Filter cells and wash twice with BSS.

Incubate with mixture of secondary antibodies at 4 °C.

Filter cells and wash twice with BSS. Resuspend cells in BSS for sorting.

Sort cells into each individual gate and retain sorted pools for deep sequencing analysis (see Notes 9 & 10). Note the number of cells sorted into each pool. Also record the library distribution across all gates by recording how many cells hit each gate during a set time interval, e.g. a minute. This information is important for the deep sequencing analysis (section 3.5, point 4).

3.4 Deep sequencing sample preparation

3.4.1 DNA extraction

If >80,000 cells are sorted, spin cells down, aspirate supernatant and add 150 µl of solution 1 from the Zymoprep kit + 2 µl Zymolase. For smaller numbers of cells, directly add 50 µl of solution 1 per 100 µl cell suspension + 2 µl Zymolase per 150 µl total volume.

Incubate at 37 °C for 1 h on a shaker.

Successively add 150 µl of solutions 2 and 3 per 150 µl incubation volume and vortex after each addition, spin down precipitate and retain supernatant.

Add 1 volume isopropanol and 0.1 volume 3 M NaOAc to each volume of DNA extract. Store at −20 °C over night.

Spin at 13000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min. Carefully remove supernatant. Resuspend DNA pellet in 20 µl sterile water (pellet may not be visible for small numbers of sorted cells).

3.4.2 DNA Amplification and adapter attachment

Most of this section is based on the excellent preparation protocol in [21].

For each sorted sample, separately, amplify DNA sequences encoding the peptide ligands out of plasmids by PCR. The 5' end of the forward primer needs to contain a binding site for the MmeI restriction enzyme: 5' GGGACCACCACCTCCGAC 3' (see Note 11). The 5' end of the reverse primer has to consist of a part of the Illumina adapter sequence: 5' CGGTCTCGGCATTCCTGC 3' (see Notes 12 & 13).

Purify PCR products with the Qiagen PCR-purification kit. Elute in 30 µl sterile water.

- Digest the PCR product with the MmeI restriction enzyme. Incubate the digestion mixture for 1 h at 37 °C, then heat inactivate for 20 minutes at 80 °C (see Note 14).

digestion reagents PCR product 12.5 µl 1mM SAM 2.5 µl NEB Cut Smart Buffer 5 µl MmeI 5 µl per 8.6 pmol PCR product sterile water fill up to 50 µl Prepare double-stranded adapters by annealing single-stranded oligos. The forward strand should contain the standard Illumina read binding site [22], a unique barcode for multiplexing (Note 15) and a 3' TC, giving : 5' ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTbarcodeTC 3'. The reverse complement strand should be 5' phosphorylated and lack the 5' GA 3' that would be complementary to the TC of the forward strand.

Ligate each digestion product with an adapter containing a unique barcode. Ligate for 30 minutes at 20 °C, then heat inactivate for 10 minutes at 65 °C.

Run the products of the ligation reaction on a gel. Gel purify the bands of correct size with the Qiaquick gel purification kit. Elute in 30 µl sterile water.

-

PCR-amplify the ligation product. Primers should contain overhangs that complete the Illumina adapter sequences.

Forward: 5' AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCT 3'

Reverse: 5' CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATCGGTCTCGGCATTCCTGCATCTT 3'

15 PCR cycles should be sufficient using Phusion polymerase.

Purify PCR products with the Qiagen PCR-purification kit. Elute in 30 µl sterile water.

Combine samples and perform a multiplexed deep sequencing run on an Illumina sequencer with the standard forward Illumina read primer: 5' ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCT 3'. If a reverse read is also to be carried out use a custom primer (see Note 16).

3.5 Computational analysis

Filter the Illumina data by only considering sequences with a high Phred score for the mutated positions and a low number of read errors in unmutated positions (see Note 17). If a reverse read has been performed that overlaps the forward read, compare complementary mutant codons and choose the version with the higher Phred score.

Assign each Illumina read to its sorted pool/gate by barcode identification.

Count the copies of each unique sequence across all pools. Discard sequences with low copy numbers when summing up counts from all gates. Calculate the number of sorted cells that each unique sequence likely originated from. Dividing the number of cells that were sorted into a pool by the number of sequence reads for this sample provides a rough estimate of the cells per read. As a rule of thumb, require at least 100 sorted cells for each observed sequence.

-

If a convoluted sort strategy was used, see Note 18. Otherwise, calculate the distribution over the gates for each unique sequence.

Here, fxj is the normalized frequency of sequence j in gate x, nxj is the number of reads of sequence j in deep sequencing data set x (which corresponds to gate x), zx is the number of cells that hit gate x when measuring the distribution of cells across all gates.

-

Calculate all possible pairwise probabilities that a peptide A is a stronger binder than a peptide B and vice versa:

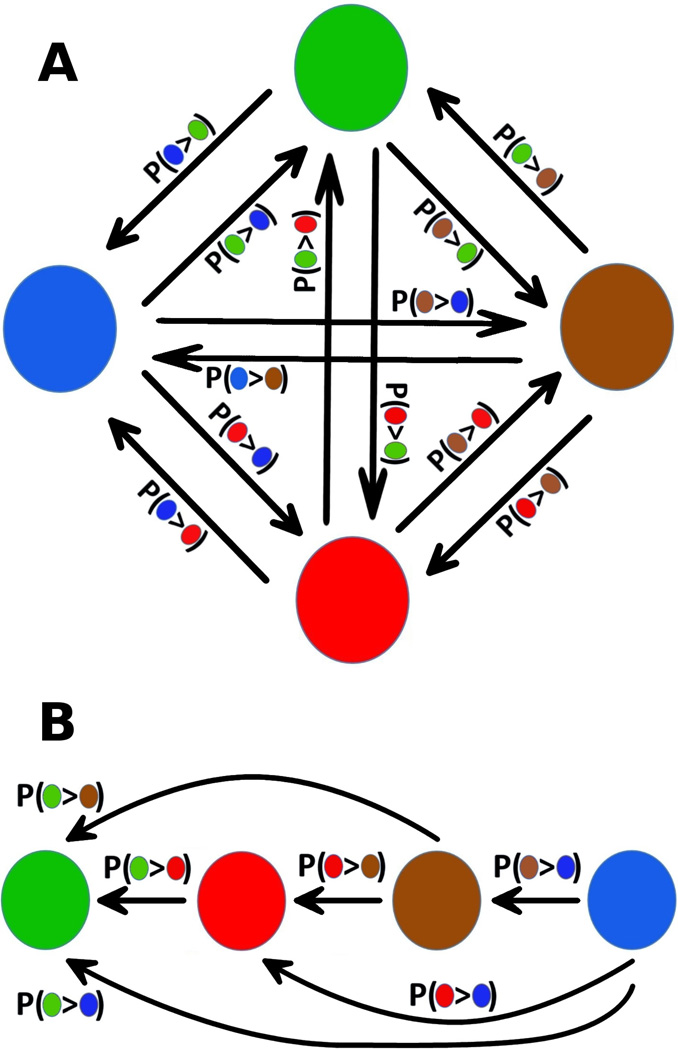

Note that gate indices x and y are assigned from lowest to highest affinity gates, i.e. in the equation the sum over y runs over all gates that are smaller in affinity than gate x. Assign these probabilities as weights to the edges of a directed graph. The vertices of the graph represent peptides and the directed edge running from vertex B to vertex A indicates the assumption that peptide A is a stronger binder than peptide B(Figure 5 A).

Find the maximum linear subgraph by first applying the method described in [23]. To do this, randomly chose a peptide/vertex A. For each other peptide/vertex B, compare the edge weights of the two edges that connect it to A. If p(A>B) > p(B>A), ), then B is considered a worse binder than A, if p(B>A) > p(A>B) then B is considered a better binder than A. Group all peptides according to whether they are better vs. worse binders than A. Then, within each group, repeat the procedure of randomly choosing one peptide and evaluating all others with respect to it, continuing to subdivide the groups until an ordering from best to worst binder has been constructed. Determine the likelihood score for this ordering by summing up the logarithms of the edge weights for all directed edges that agree with the ordering (Figure 5 B). Repeat the procedure of constructing an ordering several times and retain the one with the best score. Further refine this ordering by inserting each individual peptide into all possible positions and keeping the new position if a better score is obtained. Run the routine several times, alternately starting with the best and the worst binding peptide. Finally, run a Monte-Carlo search in which moves correspond to exchanging the positions of two peptides in the ordering. The final result represents an affinity ranking of all peptides.

Figure 5.

A) A directed graph representing four peptide ligands and assumptions about their relative binding strengths. Each edge is weighted by the probability that the ligand at its base is a weaker binder than the ligand at its head. B) A linear subgraph of A). Note that no conflicting assumptions about binding strengths exist.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Vincent Xue for preparing figure 1. The authors express their gratitude to the Swanson Biotechnology Center Flow Cytometry Facility and the MIT BioMicro Center for technical support.

This protocol was developed with support from NIGMS under award GM096466. It was also funded by grant no. RE 3111/1-1 of the German Merit Foundation to LR.

Figures 2A, 3 and 4 were reprinted from Publication “SORTCERY – a high-throughput method to affinity rank peptide ligands”; Reich L, Dutta S, Keating AE; JMB; DOI: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.09.025 with permission from Elsevier.

Figure 4.

FACS profile for a BH3 peptide ligand binding to Bcl-xL. The red line indicates the orientation of the first principle component for the expressing cells.

Footnotes

We fine-tuned the protocols described in section 3.4 using material from the specified suppliers. We have not tested corresponding products from other suppliers and it is possible that these will work too for deep sequencing sample preparation. Experimenters may need to adjust protocols according to the specific products they use.

This growth protocol has been optimized for EBY100 cells that have been transformed with a pCTCON2 plasmid [17]. The experimenter may have to choose other parameters for a different setup. In the authors' experience, cell densities may have an impact on the quality of FACS profiles. Low quality FACS profiles can lead to sub-optimal sorts with respect to affinity. Users of the procedure should strictly monitor cell densities. The first growth step in this protocol ensures that samples contain mostly live and healthy cells for correct measurements of ODs. It may be possible to skip this step if cells are not grown up from frozen stocks or plates.

The number and position of gates can be chosen based on a set of standards. Record the FACS profiles of several yeast-displayed standards in a same-day experiment at a target concentration chosen based on anticipated affinities. Construct a set of gates to be tested for adequate resolution. Determine for each FACS profile how many cells would have hit each gate. This provides a distribution over the gates for each standard. Then, simulate an experiment by drawing random samples with a size of ten cells for each standard. (Note that clones should be sampled more often than this during an actual SORTCERY sort. However, real samples may experience additional experimental noise during preparation for deep sequencing. Thus, we find 10 cells in this procedure provides useful information.) Use the random sample to calculate for each standard X and gate i, calculate the normalized frequency, fiX, with which the standard would be observed in the gate. Calculate the probability that standard X is a better binder than standard Y based on the random samples, using the formula given in section 3.5 point 5. Compare the result to the actual affinities of the standards. Repeat this many times to determine the range of values the probability can take. Sufficient resolution, i.e. a sufficient number and appropriate placement of gates, will be indicated by mostly high probabilities for the correct ordering of standards.

Record several FACS profiles for standards. Consider data for expressing cells that have binding signals mostly above the baseline. Use a cutoff line with a slope of −1 to separate expressing from non-expressing cells; Using other cutoffs may bias the analysis. Adjust the retained data by subtracting the average binding and expression signals from each data point. Calculate the covariance matrix of the data. Determine the first principal component by calculating the matrix's eigenvectors and eigenvalues. The vector with the largest corresponding eigenvalue indicates the orientation of the first principle component. Determine the first principle component's slope, i.e. the slope of the vector. High quality FACS profiles should result in a value close to 1 (Figure 4). Reduction in quality can have many different experimental origins, such as inappropriate growth protocols (see Notes 1 and 2), excess dissociation of target molecule during washing steps (see Note 8) or non-specific binding to tube walls (see Note 5).

BSA is used as a blocking agent to prevent non-specific binding to the cells and, more importantly, the test tube walls. Adsorption to the tube walls may lead to significant depletion of target molecules and distortion of FACS profiles.

The number of target molecules should be in excess of the number of surface-displayed peptides. E.g. our yeast strain expresses about 30,000 peptides per cell [24]. If 106 cells are incubated in 700 µl of 1 nM target molecule solution, then at most ~10% of the target molecules are bound. Adjust your incubation volume accordingly. Choose the concentration of target molecule appropriately to investigate a specific range of affinities (see Note 3).

We have used an HA tag for detection of expression and a Myc tag for detection of binding. However, other tags may work with our protocol and may be preferred by the experimenter. Required antibody concentrations may depend on the exact choice. Always test whether the antibodies provide high quality FACS profiles (see Note 3).

Swift application of antibodies is crucial because washing steps can disturb the equilibrium between free and bound target molecules. We have found that fully prepared samples are relatively stable, possibly because the antibodies crosslink the bound target molecules and thereby dramatically decrease dissociation.

Because gate setting requires a significant amount of time gates should be drawn prior to sample preparation. Adjust PMT voltages so that the library's FACS profile largely covers the pre-set gates. Adjustments may be guided by a set of standards.

If the number of chosen gates exceeds the number of sample tubes that the cell sorter can sort into at the same time, gates have to be sampled successively. This may waste a huge number of labeled cells, because cells that hit unselected gates will be discarded. The experimenter can adopt an alternative, convoluted sorting strategy instead that permits sorting into all gates simultaneously. In this approach, cells from different gates are sorted into the same sample tubes. Successive sorts that combine different sets of gates can be carried out, which enables back-calculation of the number of cells in each gate for each clone in the subsequent analysis (see Note 17). For N gates, prepare N unique combinations of gates. A gate must not be paired with any other gate more than once in these combinations. Sort orthogonal sets of combinations successively. For example, if 12 gates are chosen and the sorter can only sort into four sample tubes at the same time, the following set of combinations would be appropriate: {1,2,3}, {4,5,6}, {7,8,9}, {10,11,12}, {1,4,7}, {2,5,10}, {3,8,11}, {6,9,12}, {1,5,8}, {2,4,11}, {3,9,10}, {6,7,12}. Note that any pair of two gate indices appears together at most once. This set of combinations could be processed in three successive sorts collecting four pools of cells (each pool derived from three gates, all pools sorted into individual sample tubes) at a time: first {1,2,3}, {4,5,6}, {7,8,9}, {10,11,12}, then {1,4,7}, {2,5,10}, {3,8,11}, {6,9,12}, then {1,5,8}, {2,4,11}, {3,9,10}, {6,7,12}.

MmeI recognizes the sequence 5' TCCRAC 3'. Additional nucleotides 5' of the binding site can improve binding (e.g. 5' GGGACCACCACC 3' in point 1, section 3.4.2). MmeI cuts 20 nucleotides 3' of its binding sequence.

Use high fidelity polymerase and as few PCR cycles as possible in order to reduce errors and amplification bias. 25 cycles generally suffice with the Phusion Polymerase standard protocol.

High salt content from the DNA extraction step may prove inhibitory to sufficient amplification. 5 µl DNA extract in a 100 µl reaction mixture generally provides enough dilution to obtain satisfactory results.

Excess MmeI may block digestion. MmeI activity also gets curbed by high amounts of salt. Excess salt may enter the reaction mixture via the PCR product from the PCR purification step. In addition, MmeI has a very low turnover and stoichiometric amounts of MmeI are required for sufficient digestion. Experimenters need to take special care to use the exact amounts of PCR product and MmeI indicated in the Materials section.

Diverse barcodes at the beginning of a deep sequencing read are required to ensure proper calibration of the base calling algorithm. Barcodes need to be at least 5 nucleotides long, and deep sequencing runs should be multiplexed with at least 20 different barcodes. Barcode sequences should vary such that all bases appear in each position with roughly the same frequency.

Sequencing a library can be a difficult task for Illumina sequencers, because current base calling algorithms expect significant sequence variety for all positions of a sample whereas library samples generally contain regions of constant sequence. Spiking PhiX genome into the sample may help alleviate problems, as may running a reference lane with PhiX genome on the same flow cell.

MmeI sometimes cuts 19 or 21 bases 3' of its binding site. Furthermore, the TC 3' of the barcode may be missing in some reads. A small fraction of undigested by ligated sample may also be observed.

References

- 1.Hietpas RT, Jensen JD, Bolon DNA. Experimental illumination of a fitness landscape. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:78967901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016024108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeKosky BJ, Ippolito GC, Deschner RP, Lavinder JJ, Wine Y, Rawlings BM, et al. High-throughput sequencing of the paired human immunoglobulin heavy and light chain repertoire. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:166–169. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ernst A, Gfeller D, Kan Z, Seshagiri S, Kim PM, Baderet GD, et al. Coevolution of PDZ domain-ligand interactions analyzed by high-throughput phage display and deep sequencing. Mol Biosyst. 2010;6:1782–1790. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00061b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeBartolo J, Dutta S, Reich L, Keating AE. Predictive Bcl-2 Family Binding Models Rooted in Experiment or Structure. J Mol Biol. 2012;422:124–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jolma A, Kivioja T, Toivonen J, Cheng L, Wei G, Enge M. Multiplexed massively parallel SELEX for characterization of human transcription factor binding specificities. Genome Research. 2010;861:861–873. doi: 10.1101/gr.100552.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reynolds KA, McLaughlin RN, Ranganathan R. Hot Spots for Allosteric Regulation on Protein Surfaces. Cell. 2011;147:1564–1575. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLaughlin RN, Jr, Poelwijk FJ, Raman A, Gosal WS, Ranganathan R. The spatial architecture of protein function and adaptation. Nature. 2012;491:138–142. doi: 10.1038/nature11500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fowler DM, Araya CL, Fleishman SJ, Kellogg EH, Stephany JJ, Baker D, et al. High-resolution mapping of protein sequence-function relationships. Nat Methods. 2010;7:741–746. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitehead TA, Chevalier A, Song Y, Dreyfus C, Fleishman SJ, DeMattos C, et al. Optimization of affinity, specificity and function of designed influenza inhibitors using deep sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:543–548. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu J, Larman HB, Gao G, Somwar R, Zijuan Zhang Z, Lasersonet U, et al. Protein interaction discovery using parallel analysis of translated ORFs (PLATO) Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:331–333. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tinberg CE, Khare SD, Dou J, Doyle L, Nelson JW, Schena A, et al. Computational design of ligand-binding proteins with high affinity and selectivity. Nature. 2013;501:212–218. doi: 10.1038/nature12443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Araya CL, Fowler DM, Chen W, Muniez I, Kelly JW, Fields S. A fundamental protein property, thermodynamic stability, revealed solely from large-scale measurements of protein function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:16858–16863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209751109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Starita LM, Pruneda JN, Russell SL, Fowler DM, Kim HJ, Hiatt JB, et al. Activity-enhancing mutations in an E3 ubiquitin ligase identified by high-throughput mutagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013:E1263–E1272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303309110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melamed D, Young DL, Gamble CE, Miller CR, Fields S. Deep mutational scanning of an RRM domain of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae poly(A)-binding protein. RNA. 2013;19:1537–1551. doi: 10.1261/rna.040709.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinney JB, Murugana A, Callan CG, Jr, Cox EC. Using deep sequencing to characterize the biophysical mechanism of a transcriptional regulatory sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:9158–9163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004290107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharon E, Kalma Y, Sharp A, Raveh-Sadka T, Levo M, Zeevi D, et al. Inferring gene regulatory logic from high-throughput measurements of thousands of systematically designed promoters. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:521–530. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chao G, Lau WL, Hackel BJ, Sazinsky SL, Lippow SM, Wittrup KD. Isolating and engineering human antibodies using yeast surface display. Nat Prot. 2006;1:755–768. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang JC, Chang AL, Kennedy AB, Smolke CD. A high-throughput, quantitative cell-based screen for efficient tailoring of RNA device activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:138–142. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dutta S, Koide A, Koide S. High-throughput Analysis of the Protein SequenceStability Landscape using a Quantitative Yeast Surface Two-hybrid System and Fragment Reconstitution. J Mol Biol. 2008;382:721–733. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reich L, Dutta S, Keating AE. SORTCERY - a high-throughput method to affinity rank peptide ligands. J Mol Biol. 2015;427:2135–2150. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hietpas R, Roscoe B, Jiang L, Bolon DNA. Fitness analyses of all possible point mutations for regions of genes in yeast. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:1382–1396. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Illumina. [Accessed 13 Feb 2016];Illumina Adapter Sequences, Document # 1000000002694 v00. 2015 Available on the Illumina web site. http://support.illumina.com/downloads/illumina-customer-sequence-letter.html.

- 23.Ailon N, Charikar M, Newman A. Aggregating Inconsistent Information: Ranking and Clustering. J ACM. 2008;55 article 23. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boder ET, Wittrup KD. Yeast surface display for screening combinatorial polypeptide libraries. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:553–557. doi: 10.1038/nbt0697-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]