Abstract

Factors contributing to the high rate of discard among deceased donor kidneys remain poorly understood and the influence of resource limitations of weekends on kidney transplantation is unknown. To quantify this we used data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients and assembled a retrospective cohort of 181,799 deceased donor kidneys recovered for transplantation from 2000-2013. We identified the impact of the day of the week on the procurement and subsequent utilization or discard of deceased donor kidneys in the United States, as well as report the geographic variation on the impact of weekends on transplantation. Compared to weekday kidneys, organs procured on weekends were significantly more likely to be discarded than transplanted (odds ratio: 1.16; 95% confidence interval 1.13 – 1.19), even after adjusting for organ quality (adjusted odds ratio: 1.13; 95% confidence interval 1.10 – 1.17). Weekend discards were of a significantly higher quality than weekday discards (kidney donor profile index: 76.5 vs 77.3%). Considerable geographic variation was noted in the proportion of transplants that occurred over the weekend. Kidneys available for transplant over the weekend were significantly more likely to be used at larger transplant centers, be shared without payback, and experienced shorter cold ischemia times. Thus, factors other than kidney quality are contributing to the discard of deceased donor kidneys, particularly during weekends. Policy prescriptions, administrative or organizational solutions within transplant programs may potentially mitigate against the recent increase in kidney discards.

Keywords: ischemia reperfusion, chronic kidney disease

INTRODUCTION

Weekends are traditionally a period of limited resources at hospitals and numerous studies have demonstrated the adverse impact of weekends on patient outcomes. For example, higher mortality rates have been observed among patients admitted on weekends for diagnoses where outcomes are associated with time-sensitive interventions, e.g. myocardial infarctions, strokes, and pulmonary embolism (1-5). Similar analyses for diagnoses requiring urgent surgery, such as ruptured aortic aneurysms, have also demonstrated inferior outcomes (6). Previous analyses have suggested that outcomes following kidney and liver transplants performed over the weekend are similar to transplants performed during the week (7-10). However, these analyses examined only the outcomes of organs that were procured and actually transplanted without accounting for the impact of organ selection.

Each year over 5,000 people die waiting for a kidney transplant while annually, nearly 2,700 kidneys that are procured for transplantation are subsequently discarded (11). This high rate of discard is concerning especially given the worsening organ shortage in the United States (U.S.), yet the factors contributing to organ discard remain poorly understood. While the most commonly cited reason for organ discard is biopsy results (despite growing evidence that these findings are not predictive of outcomes), recent analyses suggest that even kidneys of acceptable quality are being discarded at an increasing rate (9, 10, 12). Poor donor kidney function, anatomic abnormalities and concern of donor medical/social history are other highly cited reasons for the discard of deceased donor kidneys procured for transplant(9, 13, 14) . It is important to note that currently, no universal guidelines exist in the U.S. to recommend which kidneys should be utilized and which should be discarded. As result, we hypothesize that there is a significant degree of transplant center-to-center variability, suggesting that factors external to the donor organ, or recipient, may contribute to transplant centers’ decisions not to transplant an organ. However, whether or not resource limitations at transplant centers contribute to the discard of deceased donor kidneys has not been studied. In this study, our objective was to analyze whether the procurement and utilization of deceased donor kidneys in the U.S. varied by day of the week, specifically, if it was different on weekends when compared to weekdays.

RESULTS

In the U.S. from 2000 – 2013, approximately 202,000 deceased donor kidneys were available for procurement (n = 201,956), of which ~90% were procured for transplant (n = 181,799; Table 1; eFigure 1). The number of deaths in the U.S. during that period varied by day of the week and peaked on Friday and Saturday (15). Similarly, the total number of kidneys available for procurement varied by day of the week but the highest numbers were available on Tuesdays (15.1%) and Wednesdays (15.1%) while the lowest numbers were available on Sunday and Monday (13.5 and 13.4%, respectively; Table 1). The average quality of kidneys available for procurement, as measured by the KDPI, also varied significantly by day of the week (p<0.001). Fridays were associated with the lowest rate of procurement of kidneys from the available donor pool (89.3%) and the procured kidneys had the highest average KDPI (value of 53.7%), i.e. the lowest quality, for kidneys procured on any single day of the week. In contrast, Sundays and Mondays were associated with having the highest rates of procurement of donor kidneys but these kidneys also had the lowest KDPI suggesting that the procured kidneys were of a significantly better quality on average (Table 1).

Table 1.

Deceased donor kidneys that are available for procurement, were procured, transplanted or discarded by day of the week of by weekday vs. weekend, 2000 – 2013

| Day of week organ was procured | Weekday vs. Weekend | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kidney Availability and Utilization | Total | Mon | Tues | Wed | Thurs | Fri | Sat | Sun | p | Sun-Thu | Fri-Sat | p |

| Available for procurement | 201,956 | 27,127 | 30,451 | 30,580 | 29,506 | 28,794 | 28,219 | 27,279 | — | 144,943 | 57,013 | — |

| % available for procurement (row %) | 100.0% | 13.4% | 15.1% | 15.1% | 14.6% | 14.3% | 14.0% | 13.5% | (71.8) | (28.2) | ||

| Procured for transplant | 181,799 | 24,620 | 27,528 | 27,451 | 26,377 | 25,713 | 25,320 | 24,790 | <0.001 | 130,766 | 51,033 | <0.001 |

| % procured for transplant each day/period | 90.0% | 90.8% | 90.4% | 89.8% | 89.4% | 89.3% | 89.7% | 90.9% | 90.2% | 89.5% | ||

| Discarded | 30,977 | 3,749 | 4,497 | 4,645 | 4,578 | 4,835 | 4,647 | 4,026 | <0.001 | 21,495 | 9,482 | <0.001 |

| % discarded from each day/period | 17.0% | 15.2% | 16.3% | 16.9% | 17.4% | 18.8% | 18.4% | 16.2% | 16.4% | 18.6% | ||

| Transplanted | 150,822 | 20,871 | 23,031 | 22,806 | 21,799 | 20,878 | 20,673 | 20,764 | <0.001 | 109,271 | 41,551 | <0.001 |

| % Transplanted (row %) | 100.0% | 13.8% | 15.3% | 15.1% | 14.5% | 13.8% | 13.7% | 13.8% | 72.5% | 27.5 | ||

| % transplanted from each day/period | 83.0% | 84.8% | 83.6% | 83.1% | 82.6% | 81.2% | 81.6% | 83.8% | 83.6°% | 81.4% | ||

| Estimated organ quality by mean KDPI (SD) | ||||||||||||

| Available for procurement | 52.2 (30.2) | 50.2 (30.3) | 51.5 (30.3) | 53.0 (30.0) | 53.5 (30.1) | 53.7 (30.1) | 52.9 (30.3) | 50.7 (30.2) | <0.001 | 51.8 (30.2) | 53.3 (30.2) | <0.001 |

| Procured for transplant | 49.5 (29.5) | 47.6 (29.5) | 48.8 (29.6) | 50.2 (29.4) | 50.6 (29.4) | 50.8 (29.4) | 50.2 (29.6) | 48.3 (29.4) | <0.001 | 49.1 (29.5) | 50.5 (29.5) | <0.001 |

| Transplanted | 43.7 (27.5) | 42.3 (27.4) | 43.2 (27.5) | 44.7 (27.4) | 44.9 (27.4) | 44.9 (27.5) | 44.2 (27.6) | 42.8 (27.4) | <0.001 | 49.1 (29.5) | 50.5 (29.5) | <0.001 |

| Discarded | 77.1 (22.6) | 77.2 (22.5) | 77.3 (22.7) | 77.7 (22.2) | 77.7 (22.3) | 76.5 (22.9) | 76.6 (23.0) | 76.5 (22.6) | 0.013 | 77.3 (22.5) | 76.5 (22.9) | 0.018 |

| Characteristics of Transplanted Kidneys | ||||||||||||

| Transplanted at a Large1 Center, (%) | 50.9 | 50.4 | 50.4 | 50.6 | 50.4 | 50.9 | 51.5 | 51.1 | 0.174 | 50.6 | 51.2 | 0.037 |

| Shared Without Payback, (%) | 12.4 | 11.9 | 12.1 | 12.0 | 12.3 | 12.5 | 13.1 | 12.6 | 0.003 | 12.2 | 12.8 | 0.001 |

| Cold Ischemia Time (hours) median (IQR) | 16.0 (11.2) | 16.3 (11.2) | 16.3 (11.3) | 16.0 (11.0) | 16.0 (11.0) | 16.0 (11.0) | 16.0 (11.6) | 16.4 (12.0) | <0.001 | 16.2 (11.3) | 16.0 (11.0) | 0.002 |

Defined as transplant centers that performed, on average, ≥100 living or deceased donor transplants per year over from 2000 - 2013

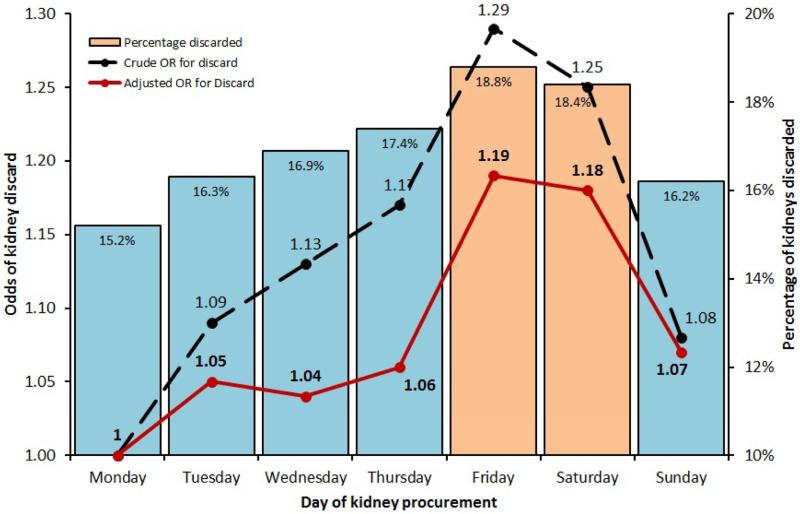

Nearly 80% of kidneys transplanted on the weekend were procured from deceased donors on Fridays and Saturdays (eTable 1). Kidneys procured on Fridays experienced the highest rate of organ discard for the week (Table 1). The rate of kidney procurement on Saturday was marginally higher than that seen on Friday (89.7 vs. 89.3%, p<0.001) while the discard rate for kidneys procured on Saturday (18.4%) was the second highest for the week after kidneys procured on Friday (18.8%). The discard rate was lowest on Monday and increased over the course of the week to peak on Friday (p<0.001; Table 1). The odds of discard of a kidney after procurement tended to increase over the course of the week (reference = Monday), i.e. as the weekend neared, there was an increase in the odds of discard for kidneys procured on Friday and Saturday (Figure 1; Table 2a). The quality of discards also showed an uptrend during the course of the week and peaked on Friday. As a result, the odds of kidney discard on Friday and Saturday remained significantly elevated even after adjustment for the KDPI (aOR = 1.19; 95 confidence interval [CI]: 1.13 – 1.26; p<0.001 and aOR = 1.18; 95% CI: 1.11 – 1.24; p<0.001, respectively; Figure 1; Table 2a). The percentage of kidneys being shared without payback between donor service areas increased from Monday to a peak on Saturday (p=0.003; Table 1). Additionally, kidneys procured on weekends (Friday - Saturday) were more likely to be transplanted at larger transplant centers than kidneys procured on a weekday (Sunday – Thursday; p=0.037).

Figure 1.

Rate and Odds of discard of deceased donor kidneys over the course of the week, 2000 - 2013

Table 2.

Odds of kidney discard after procurement by (a) day of the week procurement and (b) period of the week procurement

| (a) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day of procurement | Crude Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p |

| Monday | Ref | Ref | ||

| Tuesday | 1.09 (1.04-1.14) | 0.001 | 1.05 (0.99-1.10) | 0.087 |

| Wednesday | 1.13 (1.08-1.19) | <0.001 | 1.04 (0.99-1.10) | 0.123 |

| Thursday | 1.17 (1.12-1.23) | <0.001 | 1.06 (1.01-1.12) | 0.024 |

| Friday | 1.29 (1.23-1.35) | <0.001 | 1.19 (1.13-1.26) | <0.001 |

| Saturday | 1.25 (1.19-1.31) | <0.001 | 1.18 (1.11-1.24) | <0.001 |

| Sunday | 1.08 (1.03-1.13) | 0.002 | 1.07 (1.01-1.13) | 0.013 |

| KDPI (per 1% increase) | 1.05 (1.05 – 1.05) | <0.001 | 1.05 (1.05 – 1.05) | <0.001 |

| (b) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p | |

| Weekday (Monday – Thursday) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Weekend (Friday – Saturday) | 1.16 (1.12 - 1.19) | <0.001 | 1.13 (1.10 – 1.17) | <0.001 |

| KDPI (per 1% increase) | 1.05 (1.05 – 1.05) | <0.001 | 1.05 (1.05 – 1.05) | <0.001 |

When considered together, kidneys procured on Friday and Saturday, i.e. kidneys available for transplant on the weekend, were much more likely to be discarded (18.6 vs. 16.4%, p<0.001); these discarded kidneys were more likely to be of a higher quality, i.e. lower KDPI, (76.5 vs 77.3%, p =0.018) than those discarded during the rest of the week (Table 1). Compared to weekday kidneys, organs procured for transplantation on weekends were approximately 1.2 times more likely to be discarded than transplanted (OR = 1.16; 95% CI: 1.13 – 1.19; p<0.001), even after adjusting for organ quality (aOR = 1.13; 95% CI: 1.10 – 1.17;p<0.001); Table 2b). Kidneys available for transplant over the weekend were also more likely to be used at larger transplant centers (p = 0.037), be shared without payback (p = 0.001), and experienced shorter cold ischemia times (p = 0.002; Table 1). However, the majority of transplanted kidneys, regardless of weekday period or day of the week distinction, were transplanted the day after they were procurement (eTable 2) resulting in relatively similar mean cold ischemia times (eTable 2).

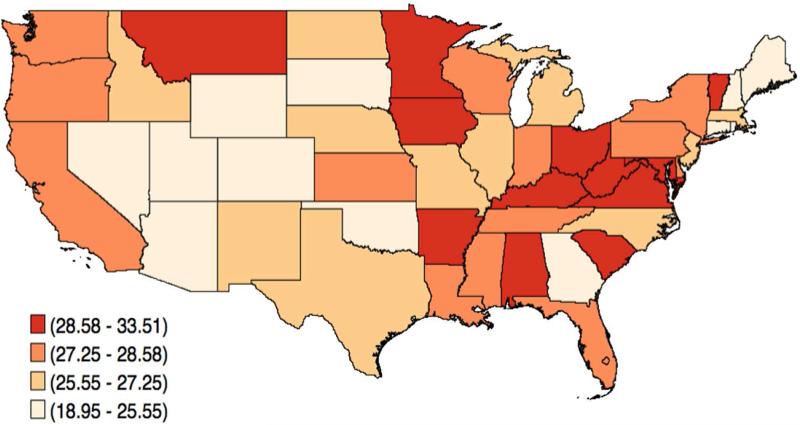

Transplants performed on the weekend were not evenly distributed across the country (Figure 2). Uniform transplantation rates and preferences suggest that, on average, 28.6% (2/7) of all deceased donor kidney transplants in any large geographic area would occur on weekends or, though unlikely, that the proportion of total kidneys transplanted during that time period equaled the proportion of kidneys offered. Considerable geographic variation was noted in the proportion of transplants that occurred over the weekend (Figure 2). The Southeast (e.g. Arkansas, Alabama, South Carolina, Kentucky, West Virginia, Virginia) and Midwest (e.g. Minnesota, Iowa, Ohio) regions performed a greater than expected share of their deceased donor renal transplants on weekends. States located within the Rocky Mountain (e.g. Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, and Nevada) and Southeast regions (e.g. Arizona and Oklahoma) performed the smallest share of their transplants on the weekend (28.58 – 33.51% vs. 18.98 – 25.55%).

Figure 2.

Geographic variation in the proportion of deceased donor kidney transplants performed over the weekend by State, 2000 - 2013

Due to the broad study period, covering 2000-2013, we also analyzed both the percentage of kidneys discarded and the odds of discard over three contiguous time periods (2000-2004, 2005-2009 and 2010-2013; eFigure 2). Additionally, we examined whether the probability of discard by day of the week was observed across time (eFigure 3). Both sub-analyses confirmed that the observed phenomena were not limited to only a part of the study period. Recent studies have also suggested that kidney discard is on the rise, following the introduction of the new kidney allocation system in the U.S. in 2014 (16).

A sensitivity analysis was performed to understand the impact of adjusting our logistic regression models, shown in Table 2, for the 10 individual components of the KDPI measure (e.g. donor age, weight, height, serum creatinine, etc.) instead of the KDPI summary measure. The coefficient estimate for the primary exposure (day of the week) and outcome (discard) relationship was not significantly altered when comparing both approaches and are shown in eTable 3).

DISCUSSION

Weekends are classically associated with limitations on resource availability and appear to negatively impact outcomes for several conditions.(1, 3-5) Outcomes following transplantation over the weekend appear to be a notable exception to these phenomena (7, 8). However, since organ transplantation has a potentially elective component that requires acceptance of an organ by the medical/surgical team, outcomes of transplants performed over the weekend may be biased by potential differences in selection criteria between weekdays and weekends.

Our analysis demonstrates a temporal trend during the week for procurement and discard of kidneys, as well as utilization patterns that reflect how organs are distributed and where they are utilized. We also demonstrated a dramatic adverse impact of weekends on the procurement of, and subsequent discard of, kidneys from deceased donors that were determined to be transplantable at the time of procurement. Kidneys that were procured but not subsequently transplanted over the weekend appear to be of higher quality than kidneys that were procured and similarly discarded during the weekday, suggesting that factors beyond the quality of the kidney were influencing the decision to accept/decline the offer of a deceased donor kidney. This finding, coupled with the increased utilization of deceased donor kidneys at large transplant centers on the weekend, would suggest the contribution of resource limitations that often occur on weekends is a contributing factor. Large transplant centers tend to have more resources, including manpower, and while they may also experience resource constraints over the weekend, the impact may be smaller.

Notably, cold ischemia times for transplanted organs on the weekend were shorter than they were during the weekday, suggesting perhaps an awareness of the increased difficultly in organ acceptance during the weekend and the development of organ offer strategies to mitigate this effect. Alternatively, transplant centers may use lower thresholds for cold ischemia time for accepting a deceased donor kidney over the weekend . For example, centers that routinely accept kidneys with long cold ischemia time and are willing to accept the attendant increased risk of delayed graft function may be less willing to do so on weekends if there are resource limitations that limit the availability of hemodialysis post-operatively. Additionally, we hypothesize that limited surgical manpower on weekends may be a contributing factor, particularly for smaller transplant programs. Surgeons may have to cover multiple services (e.g. liver and kidney), perform organ procurements, and deal with emergencies without the luxury of other attending transplant surgeons for backup on weekends. This may result in an increased reluctance, if not a complete inability to accept organs for transplant during these periods. Increased rates of decline at transplant centers on the weekend may also contribute to longer cold ischemia times accrued on kidneys while attempting to place them, which in turn would adversely affect the likelihood of organ acceptance even at centers with less stringent acceptance criteria. Geographic variation in the percentage of decreased donor transplants that occur on the weekend would suggest systemic factors are contributing to the acceptance/decline of kidneys for transplantation. While center specific resource allocation issues adversely impact organ acceptance on the weekends, transplant surgeons who are engaged in significant elective non-transplant surgeries during the work week may find themselves more willing or able to accept organ offers on the weekend for transplant resulting in centers that do a greater than expected share of their transplants on the weekend.

While there are many strengths of our study, our analysis has some of the limitations that are inherent in observational studies analyzing registry data. First, while SRTR data captures reason for organ discard and disposition, the reporting is subjective. In addition, certain organ and transplant center-level characteristics, such as cold ischemia time for discarded organs, detailed kidney biopsy findings and a center's academic affiliation, were not available in the data set. Thus, the contributions of these factors to organ discard were not measurable in our analysis. Also, although the KDPI has been validated as a reasonable measure of deceased donor organ quality in the U.S., it is an imperfect measure with only moderate predictive power (KDPI c-statistic = 0.60). The KDPI, as currently formulated, does not include certain organ characteristics that would influence the ability to use the organ such as anatomical abnormalities, injury during procurement or even biopsy findings when a biopsy is performed. Lastly, because the SRTR dataset does not include a precise date/time that a kidney is discarded, we chose to define weekend kidneys as organs that would have been transplanted on the weekend rather than those procured on the weekend. Deceased donor kidneys are often transplanted with more than 24 hours of cold storage and as a result, the majority of kidneys procured for transplantation are transplanted on the following day (eTable 1). Thus, most kidneys transplanted on the weekend (Saturday/Sunday) are procured on Friday or Saturday.

In conclusion, our analysis demonstrates a variation in procurement and discard rates that vary over the course of the week and strongly suggest that deceased donor kidneys are more likely to be discarded over the weekend independent of organ quality. This suggests that organizational and systemic factors that extend beyond the quality of the available organ appear to be contributing to the high rate of discard of kidneys from deceased donors in the U.S. Further investigation into the short- and long-term outcomes of recipients transplanted at centers that are high weekend utilizers, could potentially provide an opportunity for quality improvement efforts, as well as changes in policy, to improve organ utilization.

METHODS

Study design and participants

This observational cohort study used data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) and the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), 2000-2013. The SRTR data system includes data on all donor, wait-listed candidates, and transplant recipients in the U.S., submitted by the members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services provides oversight to the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors. The STROBE guidelines were used to ensure the reporting of this observational study (17).

We utilized the SRTR standard analytical file (2014 Quarter 1) to conduct a retrospective cohort study to analyze variation in kidney procurement and utilization during the calendar week (Monday–Sunday) from 2000 to 2013 and measure the impact of weekends, i.e. periods traditionally associated with lower resource availability. After including only deceased donor transplants and excluding donors and recipients <18 years in age, we identified a cohort of 201,956 deceased donor kidneys. For our analysis, we excluded kidneys from donors for whom we were unable to calculate the Kidney Donor Profile Index (KDPI; n=306) such as those with missing height or serum creatinine data. Kidneys of donors with a BMI greater than 50 (n=1,338) were also excluded due to concerns about the validity of anthropometric measurements that could affect the KDPI calculations.

Given that nearly 80% (78.7%) of the organs used for kidney transplants performed on the weekend were procured on Friday and Saturday (eTable 1), we defined weekend kidneys as those that were procured for transplant on either a Friday or Saturday and subsequently discarded. We measured organ quality by calculating the KDPI, which is currently part of the new OPTN allocation policy for kidneys in the U.S. The KDPI is derived from the Kidney Donor Risk Index (KDRI), a measure used to estimate the relative risk of post-transplant kidney graft failure. The KDRI is calculated using 10 donor specific characteristics (age, height, weight, ethnicity, history of hypertension, history of diabetes, cause of death, serum creatinine, HCV status, and donation after cardiac death (DCD) status) and has been validated as a reasonable measure of organ quality in the U.S. as well as in other developed countries (15, 18-21). After calculating the KDRI score, we mapped the values onto a cumulative percentage scale to create the KDPI. Because our analysis identified kidneys recovered from 2000 to 2013, as described by the OPTN, the KDRI was scaled to the median donor from 2013(15). Large transplant centers were defined as those that performed, on average, ≥100 living or deceased donor transplants per year over the duration of the study.

Geographic variation in the percentage of transplants that occurred on the weekends was estimated using the national OPTN Standard Transplant Analysis and Research (STAR) file (based on OPTN data as of June 30, 2014). The spatial representation of the proportion of weekend transplants is limited to recipients whose state of residence was known as of June 2014.

Statistical analysis

Pearson's chi-square tests and the nonparametric Wilcoxon or Kruskal-Wallis tests were performed for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Chi-square tests were used to test equality of distribution between days of the week. We used univariate and multivariable logistic regression models to identify the odds of discard (vs. transplant) of kidneys procurement on different days of the week. The purposeful selection algorithm (PS) was used to evaluate confounding and establish which covariates were included in our regression models. We investigated effect measure modification by transplant center size and kidney procurement era on the relationship between day of the week organ procurement and discard. An interaction term approach, as well as the likelihood ratio test, was used to evaluate the effect medication. Transplant, recipient and donor characteristics were viewed as being potential model parameters. Univariate analysis of each potential covariate was performed; any variable having a significant univariate test, based on the Wald test from logistic regression using a p-value cut-off of 0.25, was considered a potential candidate for the multivariable analysis (22, 23). Known clinical relevance also contributed to the final selection of model parameters.

Prior to our analysis, the model assumptions for logistic regression testing were evaluated and met (including that there was linearity in the logit for the KDPI measure (the only continuous variable in our model and the lack of strongly influence outliers). Our final regression models adjusted the KDPI summary measure. Additionally, a sensitivity analysis was performed to understand the impact of adjusting models by the 10 components of the KDPI measure instead of the KDPI summary measure. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and Stata MP 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Post-covariate selection, statistical significance was identified by a p-value <0.05.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by Health Resources and Services Administration contract 234-2005-37011C. The content is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Abbreviations

- aOR

adjusted odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- DCD

donor after cardiac death

- HRSA

Health Resources and Services Administration

- KDPI

kidney donor profile index

- KDRI

kidney donor risk index

- MMRF

Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation

- OPTN

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

- OR

odds ratio

- SRTR

Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients

- STAR

Standard Transplant Analysis and Research

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

- U.S.

United States

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Part of this analysis was presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrology in San Diego – Renal Week November 2015 (Mohan S, Foley KF, Chiles MC, Dube GK, Crew RJ, Pastan SO, Patzer RE, Cohen DJ. Discard of Deceased Donor Kidneys in the United States: The Weekend. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015;26:918A).

DISCLOSURE

The data reported here have been supplied by the Minneapolis Medical Research Foundation (MMRF) as the contractor for the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the SRTR or the U.S. Government. The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Financial disclosure

The authors have no financial disclosures relevant to this manuscript to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bell CM, Redelmeier DA. Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(9):663–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa003376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nanchal R, Kumar G, Taneja A, Patel J, Deshmukh A, Tarima S, et al. Pulmonary embolism: the weekend effect. Chest. 2012;142(3):690–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saposnik G, Baibergenova A, Bayer N, Hachinski V. Weekends: a dangerous time for having a stroke? Stroke. 2007;38(4):1211–5. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000259622.78616.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar G, Deshmukh A, Sakhuja A, Taneja A, Kumar N, Jacobs E, et al. Acute myocardial infarction: a national analysis of the weekend effect over time. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(2):217–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pathak R, Karmacharya P, Aryal MR, Donato AA. Weekend versus weekday mortality in myocardial infarction in the United States: data from healthcare cost and utilization project nationwide inpatient sample. Int J Cardiol. 2014;174(3):877–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Groves EM, Khoshchehreh M, Le C, Malik S. Effects of weekend admission on the outcomes and management of ruptured aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60(2):318–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dube GK, Pastan SO, Patzer RE, Mohan S. Does Transplant On the Weekend Affect Outcomes After Kidney Transplant? A UNOS Analysis. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(S3):599. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orman ES, Hayashi PH, Dellon ES, Gerber DA, Barritt ASt. Impact of nighttime and weekend liver transplants on graft and patient outcomes. Liver Transpl. 2012;18(5):558–65. doi: 10.1002/lt.23395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanriover B, Mohan S, Cohen DJ, Radhakrishnan J, Nickolas TL, Stone PW, et al. Kidneys at higher risk of discard: expanding the role of dual kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(2):404–15. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohan S, Tanriover B, Ali N, Crew RJ, Dube GK, Radhakrishnan J, et al. Availability, utilization and outcomes of deceased diabetic donor kidneys; analysis based on the UNOS registry. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(8):2098–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04167.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kasiske BL, Stewart DE, Bista BR, Salkowski N, Snyder JJ, Israni AK, et al. The role of procurement biopsies in acceptance decisions for kidneys retrieved for transplant. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2014;9(3):562–71. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07610713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azancot MA, Moreso F, Salcedo M, Cantarell C, Perello M, Torres IB, et al. The reproducibility and predictive value on outcome of renal biopsies from expanded criteria donors. Kidney international. 2014;85(5):1161–8. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shapiro R, Halloran PF, Delmonico FL, Bromberg JS. The 'two, one, zero' decision: what to do with suboptimal deceased donor kidneys. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(9):1959–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matas AJ, Smith JM, Skeans MA, Lamb KE, Gustafson SK, Samana CJ, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2011 Annual Data Report: kidney. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(Suppl 1):11–46. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, United Network for Organ Sharing . In: A Guide to Calculating and Interpreting the Kidney Donor Profile Index (KDPI) Services USDoHH, editor. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Massie AB, Luo X, Lonze BE, Desai NM, Bingaman AW, Cooper M, et al. Early Changes in Kidney Distribution under the New Allocation System. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2015 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015080934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2008;61(4):344–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao PS, Schaubel DE, Guidinger MK, Andreoni KA, Wolfe RA, Merion RM, et al. A comprehensive risk quantification score for deceased donor kidneys: the kidney donor risk index. Transplantation. 2009;88(2):231–6. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181ac620b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Callaghan CJ, Harper SJ, Saeb-Parsy K, Hudson A, Gibbs P, Watson CJ, et al. The discard of deceased donor kidneys in the UK. Clinical transplantation. 2014;28(3):345–53. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pine J, Goldsmith P, Ridgway D, Brady K, Pollard S, Attia M, et al. Validation of the kidney donor risk index (kdri) score in a uk single centre dcd cohort. Transplantation. 2010;90:196. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watson CJ, Johnson RJ, Birch R, Collett D, Bradley JA. A simplified donor risk index for predicting outcome after deceased donor kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2012;93(3):314–8. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31823f14d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bendel RB, Afifi AA. Comparison of Stopping Rules in Forward “Stepwise” Regression. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1977;72(357):46–53. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mickey RM, Greenland S. The impact of confounder selection criteria on effect estimation. American journal of epidemiology. 1989;129(1):125–37. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.