Abstract

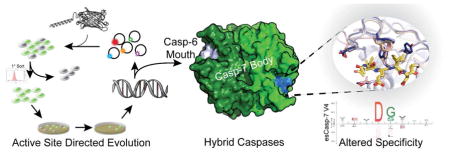

The ability to routinely engineer protease specificity can allow us to better understand and modulate their biology for expanded therapeutic and industrial applications. Here we report a new approach based on a caged green fluorescent protein (CA-GFP) reporter that allows for flow-cytometry-based selection in bacteria or other cell types enabling selection of intracellular protease specificity, regardless of the compositional complexity of the protease. Here we apply this approach to introduce the specificity of caspase-6 into caspase-7, an intracellular cysteine protease important in cellular remodeling and cell death. We found that substitution of substrate-contacting residues from caspase-6 into caspase-7 was ineffective, yielding an inactive enzyme, whereas saturation mutagenesis at these positions and selection by directed evolution produced active caspases. The process produced a number of non-obvious mutations that enabled conversion of the caspase-7 specificity to match caspase-6. The structures of the evolved-specificity caspase-7 (esCasp-7) revealed alternate binding modes for the substrate, including reorganization of an active site loop. Profiling the entire human proteome of esCasp-7 by N-terminomics demonstrated that the global specificity toward natural protein substrates is remarkably similar to that of caspase-6. Because the esCasp-7 maintained the core of caspase-7, we were able to identify a caspase-6 substrate, lamin C, that we predict relies on an exosite for substrate recognition. These reprogrammed proteases may be the first tool built with the express intent of distinguishing exosite dependent or independent substrates. This approach to specificity reprogramming should also be generalizable across a wide range of proteases.

Keywords: apoptosis, conformational change, cysteine protease, caspase reporter, GFP, selection, flow cytometry, exosite, substrate binding, specificity, directed evolution, protease/protein engineering

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Nearly 2% of human genes encode proteases and their inhibitors which underscores their significance in biology.1 Proteases are routinely the targets of therapeutic inhibitors because they play important regulatory functions in a wide range of biological pathways and have tractable active site chemistry. A key advantage of proteases relative to small molecules or other biologics is that they are catalytic, with one protease capable of processing many substrates. To date more than a dozen proteases have been approved by the FDA as protein drugs, largely for altering blood coagulation pathways. First generation therapeutic proteases were derived from natural sources. Subsequent generations have been engineered for improved properties including increased efficacy, increased reaction rates, improved stability and serum half life, decreased oxidation and reduced immunogenic effects (for review, see ref 2). Engineered proteases also play industrially important roles in detergents,3 cleaning solutions, leather processing, milk coagulation for cheese production and meat tenderization (for review, see ref 4) thus proteases with increased stability in organic solvents have also been developed.5 Engineering proteases is promising because in addition to improving their physical properties, proteases can also be engineered to improve specificity or recognize entirely new therapeutically relevant targets. For example, a neprilysin variant has recently been developed to cleave the Aβ peptide in amyloid plaques, which are hallmarks of Alzheimer’s Disease.6 Hepatitis A virus 3C protease has been reengineered to recognize polyglutamine expansions prominent in Huntington disease.7 Development of OmpT with specificity for sulfotyrosine8 and subtilisin bearing specificity for phosphotyrosine9 are notable engineering feats as they both represent non-native protease substrates. Engineering proteases has been accomplished using a wide range of approaches including rational design, random mutagenesis,10 directed evolution with fluorescent peptides,11 phage display,12 computational protein design13 or yeast-based metabolic selections.14,15 Unfortunately many of these selection approaches are not applicable to more complex proteases that are multimeric or intracellular. In addition, successes to date have relied on modest changes to the intrinsic properties of the protease. New approaches that can be used on previously untractable proteases should broaden the therapeutic targets that could be engaged.

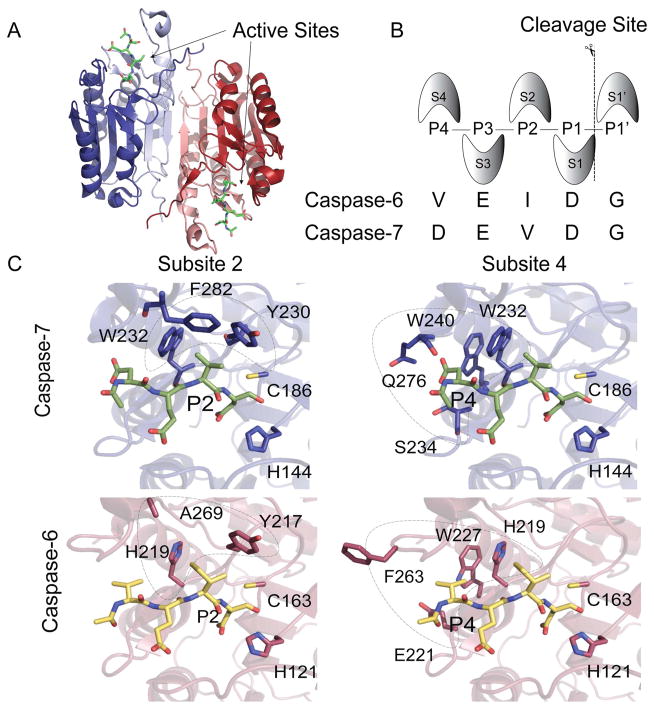

Caspases are one such class of proteases that may be excellent scaffolds for engineering, but are not amenable to current technologies. There are 12 human caspases and we are only beginning to understand and distinguish their cellular roles. Caspases are critical for initiation and execution of apoptotic cell death16,17 and in regulation of inflammation.18 These enzymes also play important roles in other processes, notably including caspase-6 in neurodegeneration.19–21 The apoptotic caspases have traditionally been categorized based on domain architecture and homology as upstream initiators (casp-2, -8, -9 and -10) or downstream executioners (casp-3, -6 and -7). Caspases are expressed as inactive zymogens. The zymogens of executioner caspases are dimeric with zymogen activation requiring cleavage at the intersubunit linker to generate one large and one small subunit in each half of the dimer (Figure 1A). Active caspases have two identical active sites, each composed of four extremely mobile loops; three from one half of the dimer and one from the opposite half. These active site loops are properly ordered for binding and catalysis only upon substrate engagement. Substrate residues (denoted P1-P4) are recognized by the four specificity subsites on the protease (denoted S1–S4)22 (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Four subsites S4-S1 contribute to binding the N-terminal portion of caspase substrates. (A) A surface contour of dimeric casp-7 highlights the two active sites and the allosteric site at the dimer interface. Each half of the dimer is composed of one large subunit (blue, red) and one small subunit (light blue, light red). (B) The Schechter and Berger nomenclature defines S subsites within the protein and P sites within the peptide substrate. The consensus recognition sequences for casp-6 and -7 are listed. (C) Residues in subsites 2 and 4 in casp-7 (blue sticks) bound to DEVD inhibitor (green) or casp-6 (red) bound to VEID inhibitor (yellow) are critical for substrate specificity. The catalytic cys-his dyad residues are also shown.

Caspases display strong selectivity for aspartic acid at the P1 position as well as some acidic side-chain specificity at P4 and P3, depending on the caspase, when profiled using short synthetic peptides.23 For example, the general consensus recognition sequences are DEVD for caspase-3 and -7, VEID for caspase-6,24 IETD for caspase-8,23 and LEHD for caspase-9.25 While strong specificity for substrates have been observed on the P side, very little specificity is contributed by the P′ side23,26,27 due to the orientation of the active site within the core of the protein. For the human caspases, substrate profiling has been performed by a large number of approaches including peptide libraries,23,24,26,27 and on whole proteins using N-terminomics,28,29 Protomap30 and PICS.31 Together these studies have painted a detailed and nuanced view of caspase specificity, and provide useful distinctions between linear peptide specificity and protein cleavage specificity. Some of these differences could derive from exosites, which are substrate binding regions on the caspase outside the conical S4-S3′ sites.25,32 Caspases with engineered specificity could also be useful in identifying exosite elements that govern caspase selectivities.

Due to their key biological roles and their ability to recognize a very precise set of substrates, caspases have emerged as appealing candidates for re-engineering efforts. For example, a BCR-ABL-activated casp-8 was developed to selectively eliminate leukemic cells,33 small-molecule activatable “SNIPer” versions of casp-3, -6 and-7 were built to dissect their non-redundant proteolytic roles,34 a constitutively active and uninhibitable version of casp-3 was developed35 and casp-7 has been handcuffed by an introduced disulfide bond for reversible reactivation only under intracellular reducing conditions.36 All of these re-engineering efforts have relied on rational design because the four-chain nature of active caspases and the resulting hypermobility of the substrate-binding groove prior to substrate binding challenges many of the traditional selection, screening and engineering approaches for altering specificity. To address these difficulties, we used our caged-green fluorescent protein (Caspase Activatable-GFP or CA-GFP) family of reporters37,38 as the basis for a directed evolution selection method, which is compatible with challenging proteases. Using this approach we successfully changed the specificity of casp-7 (DEVD) to mirror the specificity of casp-6 (VEID) both for linear and protein substrates. This altered-specificity caspase, which is the first of its kind, demonstrates the utility of caspases as a platform for development of novel therapeutic proteases that could be delivered by a number of emerging tools.39–41 The altered-specificity caspase also provides a tool to assess whether exosites exist and play a role in substrate selection.

Results and Discussion

In this work we sought to build new caspases that maintained the core of casp-7 but have the active-site specificity of casp-6. Casp-6 was chosen because it is highly homologous to the executioner casp-7 but has a linear peptide specificity closer to the initiator family. Given that the most significant differences in the specificities of these two caspases are for substrate residues at the P2 and P4 peptide sites, we hypothesized that directly substituting the critical residues from the S2 and S4 pockets (Figure 1C) of casp-6 into casp-7 might be sufficient to confer altered recognition to a reengineered casp-7. For other sets of related proteases42,43 and hydrolases,44 interconversion of the specificity of two homologous enzymes is possible by direct replacement of the homologous active-site residues. Based on that work, we reasoned that substituting amino acids from the S2 and S4 subsites of casp-6 into casp-7 could, in principle, generate a protein that maintained a casp-7 body but displayed a casp-6 active-site and substrate binding groove. This direct substitution caspase (dsCasp-7) with three substitutions yielded an enzyme unable to cleave either a casp-6 (Ac-VEID-AMC) nor a casp-7 (Ac-DEVD-AMC) substrate (Supplementary Figure S1). Thus, reprogramming the specificity of casp-7 required an alternative approach such as directed evolution.

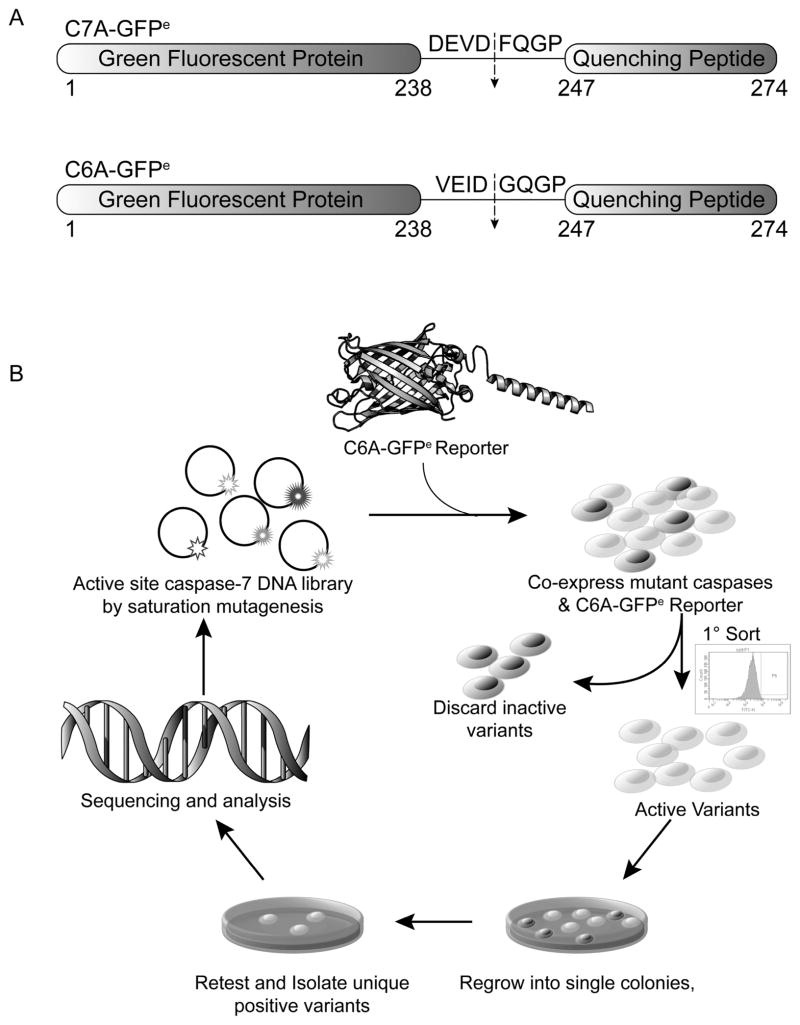

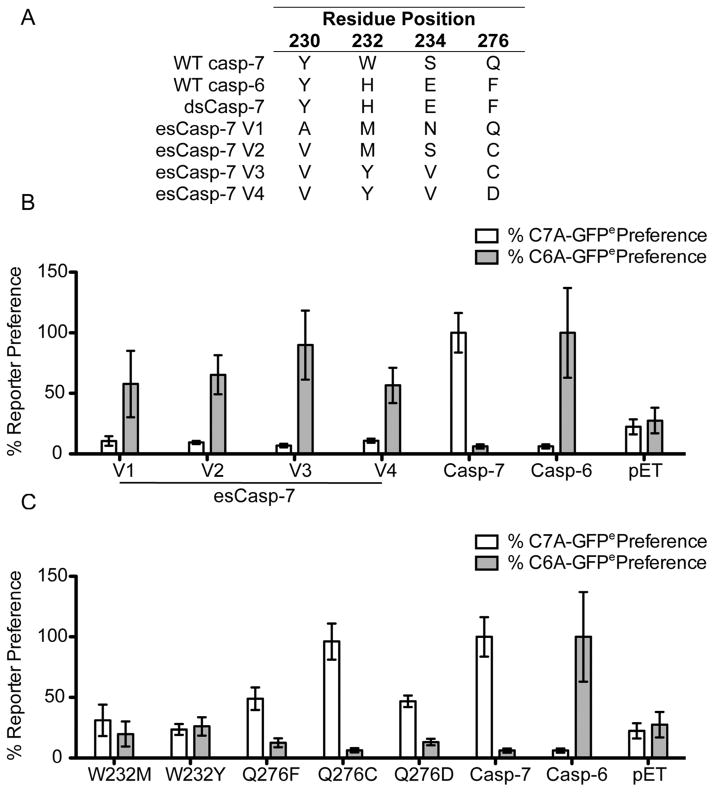

We developed a directed evolution screen based on our family of genetically encoded, dark-to-bright Caspase-7 Activatable-Green Fluorescent Protein (C7A-GFP) reporters.37,38 C7A-GFP encodes a caspase-cleavable linker between GFP and an M2-derived quenching peptide (Figure 2A). Only upon proteolysis of the linker does the GFP chromophore mature, resulting in gain of fluorescence. Replacing the caspase-7 recognition site in the linker with VEID yielded a casp-6-specific reporter, C6A-GFPe.38 To develop evolved specificity caspase (esCasp) variants, libraries of casp-7 genes encoding all possible residues at the 230, 232, 234 sites and Gln, Ala, Cys or Asp at the 276 site within the S2 and S4 pockets were co-expressed with the C6A-GFPe reporter and sorted serially by flow cytometry (Figure 2B). After a single round of directed evolution, four promising candidate esCasp-7 variants (esCasp-7 V1, V2, V3, V4) emerged and were selected based on the similarity of their fluorescent signals to that of native casp-6 (Figure 3A, B). Because multiple substitutions were allowed at positions 232 and 276, we assessed the effect of individual substitutions at those positions on substrate specificity. Interestingly, single mutations at Trp232 were enhanced by surrounding subsite mutations, demonstrating the synergy with surrounding residues (Figure 3C, Supplementary Figure S1). The influence of Gln276 mutations were only evident in combination with other randomized positions, underscoring the need for directed evolution methods.

Figure 2.

Selection strategy for caspases with altered specificities. (A) Casp-7 Activatable GFP (C7A-GFPe) or Casp-6 Activatable GFP (C6A-GFPe) were used for selection of variant caspases with altered specificity. (B) To select casp-7 variants with altered specificity, a library was constructed by saturation mutagenesis at residues 230, 232, 234, and Q/A/C/D at 276 then co-transformed with C6A-GFPe. Active variants were sorted by flow-cytometry, regrown and positive variants were screened using a plate-based assay, selected, and sequenced.

Figure 3.

Selection of esCaspases. (A) Sequences of esCaspases at the four randomized residues. (B) % casp-7 preferences were calculated by dividing the in cell fluorescence response to the C7A-GFPe reporter by their fluorescence response to C6A-GFPe and normalizing it to the fluorescence response of WT casp-7 to C7A-GFPe. Likewise, % casp-6 preferences were calculated by dividing the fluorescence response to C6A-GFPe by the C7A-GFPe response and normalizing it to the fluorescence response of WT casp-6 to C6A-GFPe. (C) Impacts of single amino acid substitutions at positions 232 and 276 on % casp-6 and -7 preferences were assessed as in B.

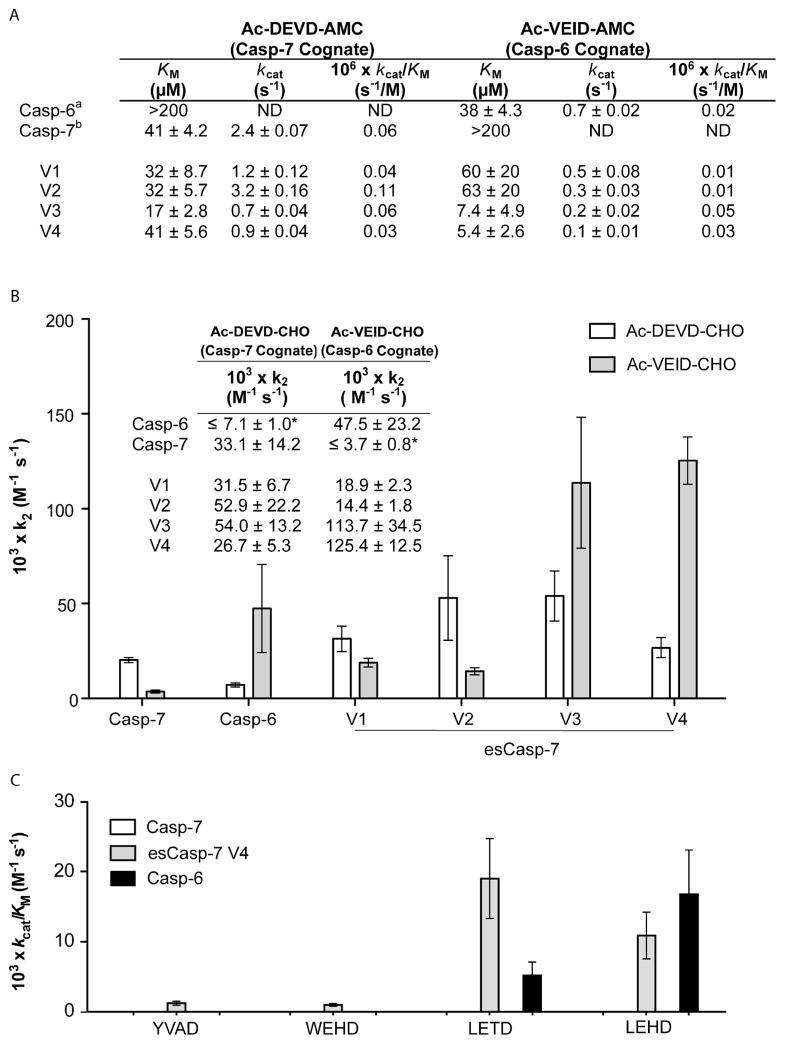

To characterize these evolved caspases, we compared the activity of esCasp-7 variants to WT casp-6 and -7 using synthetic substrates for casp-6 (VEID-AMC) or casp-7 (DEVD-AMC). As expected, WT casp-6 lacked appreciable activity against a DEVD peptide substrate, but robustly cleaved its cognate VEID peptide substrate. Likewise WT casp-7 lacked activity against the VEID substrate, but efficiently cleaved its cognate substrate, DEVD. While the variants maintained casp-7-like activity against peptide substrates, their activity against the VEID substrates improved dramatically (Figure 4A) with kcat/KM values similar to WT casp-6. In this particular sorting procedure, we did not counter select for variants lacking DEVDase activity but recognize that a counter-selection is plausible and may increase specificity for the desired targets in future generations of esCaspases. We subsequently found, based on the profiling of human caspase substrates, as discussed below, that it was not necessary to remove the residual DEVDase activity in order to see a casp-6-like substrate signature. The potency of the cognate and non-cognate peptide-based inhibitors for each variant reflects the specificity for each of the esCasp variants (Figure 4B). For competitive inhibitors, the rate at which the product formation decelerates is proportional to the rate of inhibition. The inhibition rate constant (k2) is a widely used means of interrogating binding efficacy with covalent inhibitors, which preclude the measurement of a Ki.45,46 The higher the k2 value, the higher the affinity of the protease for the inhibitor. Both esCasp-7 V3 and V4 show dramatically more potent k2 values for VEID recognition than the other variants, or surprisingly, than WT casp-6. Cleavage of a panel of substrates for various caspases YVAD (casp-1), WEHD (casp-1, -4, -5), LETD (casp-8) and LEHD (casp-9) suggests that, consistent with prior reports,25,47 casp-6 has a broader intrinsic specificity than caspase-7. esCasp-7 V4 likewise shows a broader specificity, similar to that of casp-6 (Figure 4C). This provides additional evidence for the degree of the altered specificity of these variants.

Figure 4.

Comparative catalytic efficiencies and substrate preferences. (A) Catalytic parameters for caspases were determined by substrate titration using the specified substrates. aas previously reported.57 bas previously reported.36 Errors on KM and kcat are the average of the uncertainty in the fits of weighted hyperbolas for substrate titrations performed on three separate days. N.D. is not detectable; <0.01. (B) Inhibition rate constants (k2) for the covalent aldehyde (CHO) acetyl-capped (Ac) peptide-based inhibitors Ac-DEVD-CHO (casp-7 cognate) or Ac-VEID-CHO (casp-6 cognate) reflect the specificity of WT and engineered specificity caspases. *Because it was impossible to measure a KM accurately, we assumed a KM value of 200 for calculation of k2. (C) Substrate titrations of the indicated tetrapeptide substrates were performed to measure KM and kcat for caspase variants.

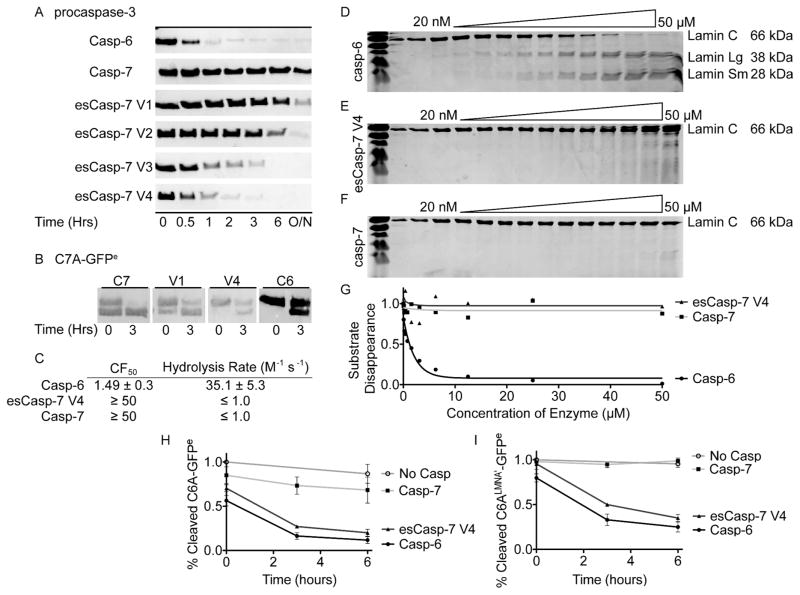

Based on these kinetic and inhibitory parameters, it is clear that several of the esCasp variants have enhanced VEID specificity. To further characterize the specificity of these enzymes, we used an even more stringent evaluation that utilizes fully folded protein substrates to assess additional binding elements on caspase substrates, such as exosites. We handpicked two protein substrates known to have markedly different cleavage by casp-6 and casp-7. WT casp-6 natively cleaves procasp-3 (C163A)48 very effectively, whereas casp-7 cleaves procasp-3 much more slowly (Figure 5A). In comparison, esCasp-7 V1 and V2 cleaved procasp-3 in a similar manner to casp-7, whereas esCasp-7 V3 and V4 cleaved procasp-3 more similarly to WT casp-6. This enhanced cleavage of a natural substrate of WT casp-6 underscores the degree to which substrate preferences were successfully reprogrammed in esCasp-7 V3 and V4 using our directed evolution selection. To assess the degree of residual casp-7 activity present in the esCasp variants, we used C7A-GFPe as a non-native casp-7 substrate. esCasp-7 V1 cleavage of C7A-GFPe again resembled casp-7 proteolysis, whereas esCasp-7 V4 cleavage of C7A-GFP more closely resembled casp-6 cleavage patterns (Figure 5B). These data suggest that amongst the esCaspases, esCasp-7 V4 has the most dramatically altered specificity, closely mimicking that of casp-6. Despite the successful alteration of the specificity, esCasp-7 V4 does not cleave lamin C, a known casp-6-specific substrate (Figure 5 C-G). Because development of esCasp-7 V4 did not include changes in the prime side specificity pockets, the inability of esCasp-7 V4 to cleave lamin C could either be due to the influence of the prime side specificity of casp-7 or to the presence of an exosite on casp-6.

Figure 5.

esCasp-7 variants show casp-6 like specificity for protein substrates. (A) Cleavage kinetics of procasp-3, which is a native substrate of casp-6, reflect the casp-6-like specificity of the evolved specificity caspases. (B) Slow cleavage of CA-GFPe, a casp-7 substrate, by esCasp-7 V1 and V4 reflects their casp-6-like specificity as assessed by anti-GFP immunoblot. (C) The lamin C CF50 (casp-6 concentration at which the cleaved fraction (CF) of lamin C is 50%) and hydrolysis rates from analysis of data in D–F. (D) WT casp-6 efficiently cleaves lamin C into the anticipated 28 and 38 kD fragments. (E) esCasp-7 V4 shows much less propensity to cleave lamin C. (F) WT casp-7 does not effectively cleave lamin C. (G) Fits for hydrolysis rates from data in D–F. Cleavage of C6A-GFPe reporter (H) or the C6ALMNA′-GFPe reporter which contains both the P and P′ sides of the lamin C recognition motif (I), was monitored as function of time.

Recognition of the prime side of caspase substrates has been implicated to various degrees in overall caspase specificity.31 To test the role of the prime side in dictating esCasp-7 V4 specificity, we compared the cleavage of C6A-GFPe, which contains only the P4 to P1 positions of the casp-6 recognition motif from lamin C (VEID

GQGP) to cleavage of a new reporter, C6ALMNA′-GFPe, which contains the entire P4 to P4′ lamin C site (VEID

GQGP) to cleavage of a new reporter, C6ALMNA′-GFPe, which contains the entire P4 to P4′ lamin C site (VEID

NGKQ). If the prime side of the lamin C recognition motif prevents casp-7 from cleaving lamin C, we would expect that esCasp-7 V4 would also be unable to cleave C6ALMNA′-GFPe. We did not observe this. Rather, esCasp-7 V4 cleaved C6ALMNA′-GFPe similarly to WT casp-6 (Figure 5H, I). Thus these data tantalizingly suggest that the presence of an exosite enables recognition of lamin C by casp-6.

NGKQ). If the prime side of the lamin C recognition motif prevents casp-7 from cleaving lamin C, we would expect that esCasp-7 V4 would also be unable to cleave C6ALMNA′-GFPe. We did not observe this. Rather, esCasp-7 V4 cleaved C6ALMNA′-GFPe similarly to WT casp-6 (Figure 5H, I). Thus these data tantalizingly suggest that the presence of an exosite enables recognition of lamin C by casp-6.

In directed evolution, maintaining the physical characteristics of a native protein is critical for achieving useful products. Even single point mutants in caspases can result in dramatic changes to their fold and stability.49 Both esCasp-7 V1, which has the least altered specificity, and esCasp-7 V4, which has the most successfully altered specificity maintained casp-7 wild-type levels of stability in the unliganded (apo) states (Supplementary Figure S2). Upon binding a substrate-based inhibitor, DEVD-CHO, WT casp-7 undergoes a 17°C increase in thermal stability.49 We expected that esCasp-7 variants with casp-6-like activity would be substantially stabilized by binding of VEID. Strikingly, both V1 and V4 are stabilized by 15–18°C when bound to the casp-6 cognate substrate-based inhibitor VEID-CHO. This suggests that binding induces the same structural changes and stabilization in the esCasp-7 variants that DEVD induces in WT casp-7.

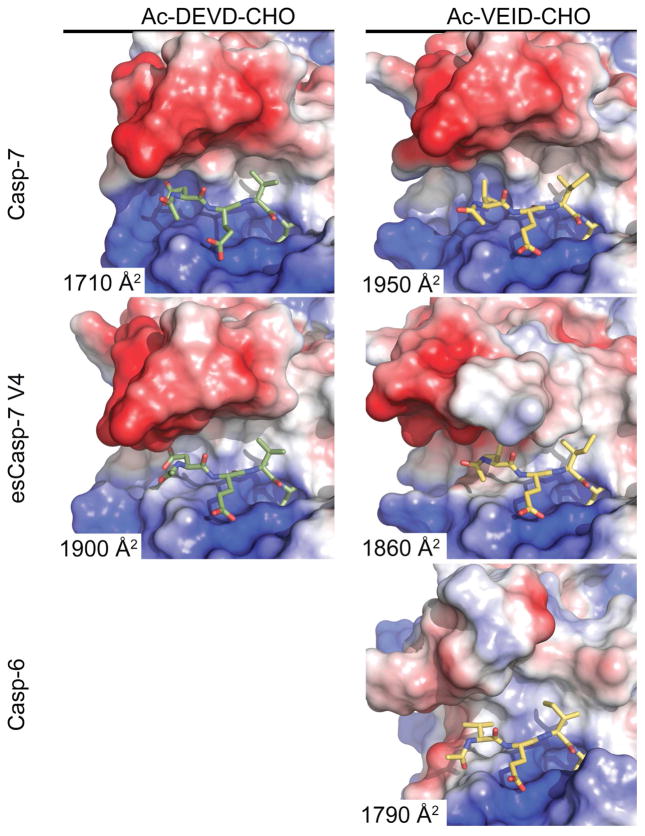

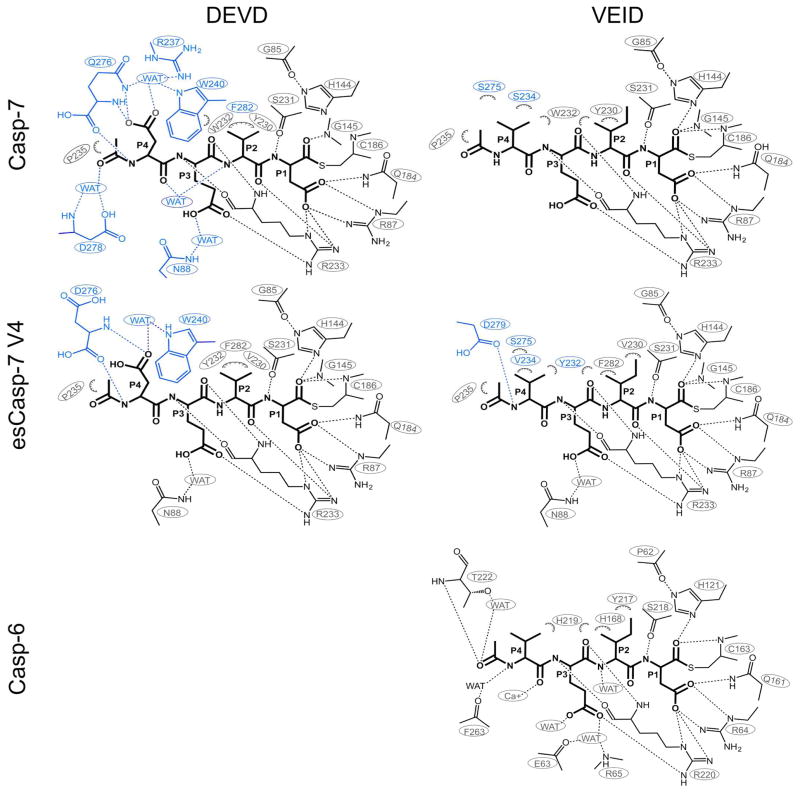

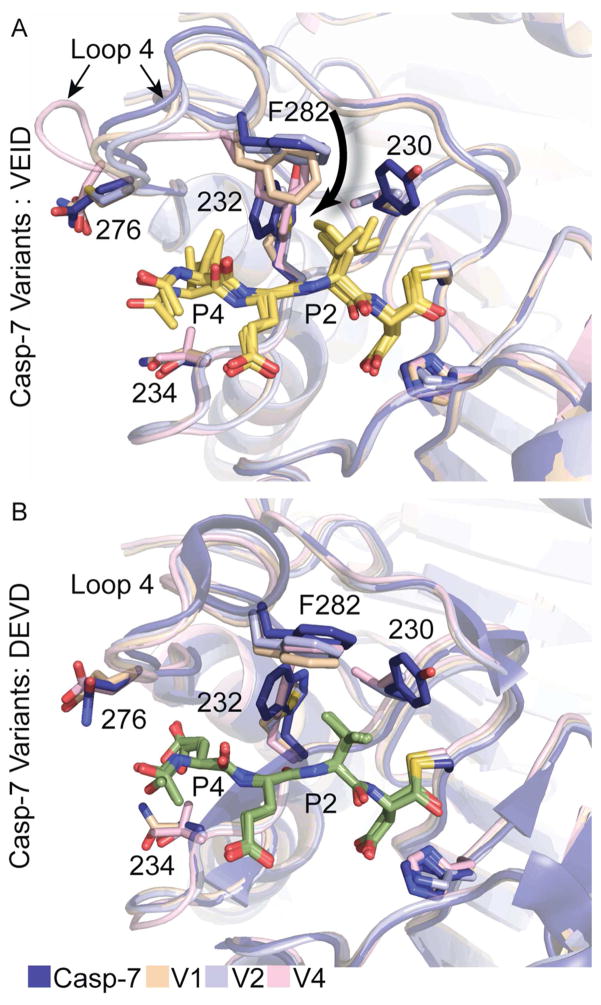

To further characterize these structural changes, we solved seven crystal structures including WT casp-7 bound to VEID-CHO and esCasp-7 V1, V2 and V4 bound to either VEID-CHO or DEVD-CHO. The structural comparison of these caspases reveals the alternative solutions that allow the evolved specificity caspases to recognize the new substrates (Figure 6, Supplementary Table S1, Figure S3). We observed that both the volume and the shapes of the substrate-binding grooves are significantly different in the esCasp variants and are different depending on the substrate bound. Binding of WT casp-7 to its cognate substrate DEVD is achieved by numerous direct and water-mediated interactions with all four of the substrate residues50 (Figure 7, Supplememtary File 1). Binding of casp-7 to the casp-6 cognate substrate, VEID, results in loss of several interactions, particularly those involving Gln276 which have been shown to be critical for casp-7 substrate recognition at the P4 position.51 The unique water-mediated interaction of R23750 with P4 aspartate and the interaction of Phe282 with P2 valine were also lost (Figure 7) with the widening of the substrate binding groove (Figure 6). The loss of these interactions is likely to account for the observed losses in KM and k2, which both reflect the affinity of casp-7 for substrates. Prior work has shown that larger residues can be effectively accommodated at P4 in casp-7 substrates,51 but this structure suggests that smaller, particularly small hydrophobic residues at P4 are not well accommodated by WT casp-7 due to the volume of the S4 pocket.

Figure 6.

Flexibility in the substrate-binding groove promotes recognition of substrates. Changes in the position of the L4 loop impacts the shape and interaction of surface patches of positive (blue) or negative (red) charge or hydrophobic (white) character with DEVD (green sticks) or VEID (yellow) substrates. The solvent assessable surface areas of the interacting residues for each structure are listed.

Figure 7.

Interactions of WT casp-7, esCasp-7 V4 or WT casp-6 upon binding to DEVD or VEID. Projections of substrate were drawn in ChemDraw (CambridgeSoft, PerkinElmer). Hydrophobic interactions of heavy atoms within 4Å are shown as hashed semicircles. Polar interactions within 3.5Å are shown as dashed lines. Interactions that differ between DEVD- and VEID-bound structures are shown in green (none observed here), while those lost are shown in blue.

The structural comparison of esCasp-7 variants highlight the effect of mutating residues in the active site of caspases and the repercussions on substrate binding. esCasp-7 V4, which has the most casp-6-like biochemical properties, also showed the greatest number of new interactions with VEID substrate at both the P4 and P2 positions. In WT casp-6, the S4 pocket is surprisingly unfilled when bound to peptides containing P4 valine. In esCasp-7 V4 the S234V substitution allowed a new, more ideal interaction with P4 valine than observed with the Ser234 Cβ in WT casp-7. In addition, in esCasp-7 V4, loop 4 is completely reoriented relative to WT casp-6 or -7 (Figure 8A). This loop configuration appears to be a bona fide response to the new substrate, as this loop is not involved in crystal contacts. This novel conformation allowed a new interaction between Asp279 and the P4 amide. Additional specificity of esCasp-7 V4 for VEID derives from the P2 interactions. Whereas WT casp-7 forms only two interactions with P2 isoleucine, esCasp-7 V4 supports three interactions with this position (Val230, Tyr232, Phe282). These interactions with P2 are also present in esCasp-7 V1 and V2 (Supplementary Figure S4). The interaction of Phe282 is the centerpiece of VEID binding amongst the esCasp variants. We observed a progressive downward movement of Phe282 (Figure 8A) as the variants increased in affinity for VEID (k2 increase). This movement was coupled to changes in the shape and volume of the substrate-binding groove (Figure 6). The W232Y substitution in esCasp-V4 forms a new T-stack with Phe282, creating the void required for the movement of loop 4. It is therefore not surprising that this mutation was selected for in both esCasp-7 V3 and V4. The movement of Phe282 is missing in all DEVD-bound structures (Figure 8B), suggesting that the loop 4 rearrangements improve affinity for VEID. It appears that the affinity of esCasp-7 V4 for VEID was largely the result of alterations at the P2 site. In addition, even in variants with fewer P4 interactions, KM and k2 for DEVD were not significantly changed. This suggests that P2 is a more critical site for affinity and selectivity than P4. We had observed that while WT casp-6 could cleave a number of casp-7 substrates, the reverse was not true. This suggested that although our selection had only been designed to improve cleavage of VEID substrates, without a counter-selection against DEVD substrates, we appear to have successfully evolved a casp-6-like specificity.

Figure 8.

Interactions with cognate and non-cognate substrates. (A). F282 plays a critical role in the recognition of VEID (yellow sticks) by variant caspases. In V4, Loop 4 is reoriented when bound to VEID. (B). Few conformational changes are observed upon binding of the esCaspases to DEVD (green sticks). Figures show superpositions resulting from alignment of the substrate atoms.

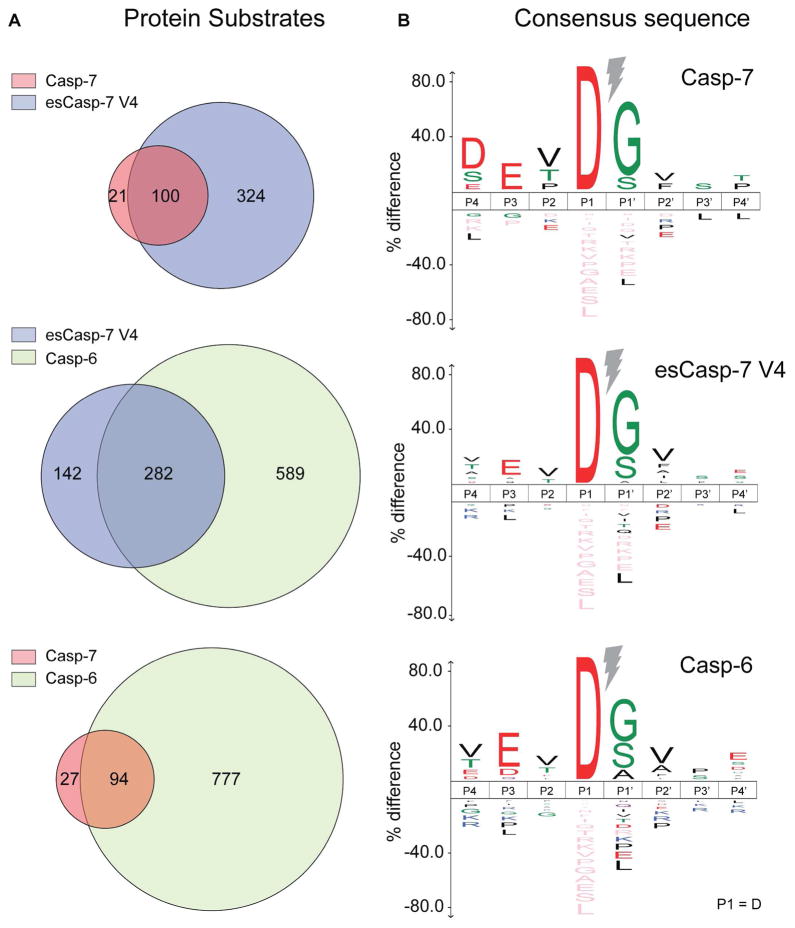

To identify substrates of esCasp-7 and compare them to WT casp-6 and WT casp-7 substrates, we profiled the human proteome using an N-terminomics approach.28,52–54 In short, human Jurkat cell lysates were incubated with a given caspase for 4 hours, and free N-termini created by proteolysis were labeled, captured and trypsinized before identification by LC-MS/MS on a Velos Orbitrap (Supplementary Figure S8). Using a combination of two biological replicates each, we observed a total of 871 substrates for casp-6, 121 substrates for casp-7, and 424 substrates for esCasp-7 V4 (Supplemental Files 2 and 3) showing an aspartate at the P1 position (Figure 9). Two-thirds of the esCasp-7 V4 substrates were also observed as substrates of casp-6 (282/424). In contrast, only one quarter of esCasp-7 V4 substrates were also cleaved by casp-7 (100/424), suggesting that esCasp-7 V4 has been significantly altered to be casp-6-like. From these substrates, sequence logos for esCasp-7 V4, WT casp-6 and casp-7 emerged. Both casp-6 and casp-7 showed the expected VEVD and DEVD specificity profiles, respectively (Figure 9, Supplementary Figure S5). Remarkably, esCasp-7 V4 produced a sequence logo VEVD that very closely mirrors that of WT casp-6, featuring a preference for valine at P4, rather than a preference for aspartate. This emphasizes the degree to which the specificity of V4 has been altered for hundreds of natural protein substrates. As for any positive enrichment methods, the presence of a substrate can be viewed as a positive result, but the absence of a substrate cannot necessarily be interpreted as reflecting a difference in specificity. Thus the biological similarity between casp-6 and esCasp-7 V4 may be even greater than reflected by the two-thirds overlap in substrates observed (Figure 9, Supplementary Figure S5).

Figure 9.

Substrate proteins identified by the N-terminomics assessment of the entire human proteome. The sequence logo for all identified substrates with Asp (D) at P1 for esCasp-7 V4 is very similar to that of casp-6, but divergent from that of casp-7. A cutoff p-value of 0.05 was used for calculation of the sequence logo.

Recent studies support the role of exosites as a critical to substrate recognition by a number of proteases.32,55 We hypothesized that esCasp-7 V4 would maintain exosites from casp-7 but would but lack exosites from casp-6, making it an ideal tool for identifying substrates that are engaged by an exosite. To interrogate potential exosite interactions we assessed the ability of esCasp-7 V4 to cleave known casp-6 substrates (Figure 5C–E). One of these substrates, lamin C has an ideal casp-6 cleavage site, VEIDG, upon which the original casp-6 VEID peptides were based.56 Lamin C was robustly cleaved by WT casp-6 to generate 38 kD and 28 kD fragments with a hydrolysis rate of 35.8 M−1 s−1. WT casp-7 does not cleave the VEID site in lamin C at any of the concentrations tested. It is notable that although esCasp-7 V4 shows specificity for VEID as its preferred global recognition site (Figure 8), it does not cleave the VEID site in lamin C. This finding suggests that recognition, binding and cleavage of lamin C requires engagement of an exosite on casp-6. This type of evolved caspase with altered specificity at the active site may be the first tool that allows direct assessment of the requirements for exosites in selection of substrates by proteases.

In summary, we have shown that this CA-GFP-based directed evolution approach was sufficiently robust to alter the specificity of casp-7 to mirror that of casp-6. This level of change in specificity was achieved by substitution at just four residues and after just one round of selection, minimizing the potential impact on exosites. We note that the esCasp variants each employed alternative solutions to achieve binding of the VEID sequence. Interestingly, these alternate solutions include recognition of substrate side chains by residues at different locations than used in the WT enzymes. In addition, in the most successful variant, structural rearrangement of one substrate binding-groove loop also led to improved binding. In addition to demonstrating the power of this approach for future applications, this method is, to our knowledge, the first that has yielded caspases that contain a casp-7 backbone with casp-6-like active-site specificity. Using esCasp-7 V4 suggests that one casp-6 substrate, lamin C may require an exosite for recognition. esCasps should likewise be useful for identifying other exosite-driven substrates which will ultimately allow identification of substrate-specific exosites. Identification of exosites in the protease cathepsin K allowed development of inhibitors that selectively block cleavage of just a subset of exosite-dependant substrates.55 Additional exosite-directed inhibitors that block cleavage of only a subset of substrates should have major therapeutic implications in many proteases including caspases.

Other protease engineering approaches, such as the exchange of P1 specificity between two related subtilisins by structure-based design, required three mutations and all were in direct contact with substrate.43 The engineering of P1 specificity from trypsin to chymotrypsin by structure-guided mutations required 11 substitutions in both the active site loop and distal in surrounding loops.42 Here, the interconversion of casp-7 specificity to casp-6 specificity at two different sub-sites required just four mutations, all clustered within the active site. Interestingly, the direct contact substitutions did not result in the predicted specificity change. The fact that CA-GFP uses a protein-based substrate for the directed evolution sorting may have positively contributed to the selection of a native-like protease. This CA-GFP approach to protease engineering allows larger libraries to be screened and should be amenable to engineering other challenging protease targets and intracellular proteases.

Methods

A description of the methods used in this work are located in the Supporting Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM80532). DM is supported in part by National Research Service Award T32 (GM08515) from the National Institute of Health. We thank A. Burnside for assistance in developing the CA-GFP-based flow-cytometry sorting procedure, S. Garman for advice regarding structure refinement, and S. Savinov for helpful discussions about analyzing ligand binding in the engineered caspases. We thank V. Stojanoff and E. Lazo for assistance with data collection and acknowledge NSLS X6A, which is funded by the National Institute of Health (GM-0080), and the National Synchrotron Light Source at Brookhaven National Laboratory, which is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DE-AC02-98CH10886). We also thank K. Perry at Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamline 24-ID-E at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Labs, which is funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences from the National Institutes of Health (P41 GM103403, S10 RR029205) and by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. JAW lab research was supported by 2R01GM081051-06A1 and OJ was supported by a Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Government of Canada.

Abbreviations

- CHO

aldehyde

- Ac

acetyl

- AMC

7-amino-4-methylcoumarin

- caspase

casp

- esCasp-7

evolved specificity caspase-7

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: This material is available free of charge via the Internet.

References

- 1.Puente XS, Sánchez LM, Gutiérrez-Fernández A, Velasco G, López-Otín C. A genomic view of the complexity of mammalian proteolytic systems. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:331–334. doi: 10.1042/BST0330331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Q, Yi L, Marek P, Iverson BL. Commercial proteases: present and future. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:1155–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wells JA, Estell DA. Subtilisin - an enzyme designed to be engineered. Trends Biochem Sci. 1988;13:291–297. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(88)90121-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sumantha A, Larroche C, Pandey A. Microbiology and industrial biotechnology of food-grade proteases: A perspective. Food Technol Biotechnol. 2006;44:211–220. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen K, Arnold FH. Tuning the activity of an enzyme for unusual environments: sequential random mutagenesis of subtilisin E for catalysis in dimethylformamide. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1993;90:5618–5622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Webster CI, Burrell M, Olsson LL, Fowler SB, Digby S, Sandercock A, Snijder A, Tebbe J, Haupts U, Grudzinska J, Jermutus L, Andersson C. Engineering neprilysin activity and specificity to create a novel therapeutic for Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sellamuthu S, Shin BH, Han HE, Park SM, Oh HJ, Rho SH, Lee YJ, Park WJ. An engineered viral protease exhibiting substrate specificity for a polyglutamine stretch prevents polyglutamine-induced neuronal cell death. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22554. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varadarajan N, Georgiou G, Iverson BL. An engineered protease that cleaves specifically after sulfated tyrosine. Angew Chemie Int Ed. 2008;47:7861–7863. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knight ZA, Garrison JL, Chan K, King DS, Shokat KM. A remodelled protease that cleaves phosphotyrosine substrates. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:11672–11673. doi: 10.1021/ja073875n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sidhu SS, Borgford TJ. Selection of Streptomyces griseus protease B mutants with desired alterations in primary specificity using a library screening strategy. J Mol Biol. 1996;257:233–245. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varadarajan N, Gam J, Olsen MJ, Georgiou G, Iverson BL. Engineering of protease variants exhibiting high catalytic activity and exquisite substrate selectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:6855–6860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500063102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atwell S, Wells JA. Selection for improved subtiligases by phage display. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96:9497–9502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon SR, Stanley EJ, Wolf S, Toland A, Wu SJ, Hadidi D, Mills JH, Baker D, Pultz IS, Siegel JB. Computational design of an α-gliadin peptidase. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:20513–20520. doi: 10.1021/ja3094795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sellamuthu S, Shin BH, Lee ES, Rho SH, Hwang W, Lee YJ, Han HE, Kim J, II, Park WJ. Engineering of protease variants exhibiting altered substrate specificity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;371:122–126. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yi L, Gebhard MC, Li Q, Taft JM, Georgiou G, Iverson BL. Engineering of TEV protease variants by yeast ER sequestration screening (YESS) of combinatorial libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:7229–7234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215994110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuida K, Zheng TS, Na S, Kuan CY, Yang D, Karasuyama H, Rakic P, Flavell RA. Decreased apoptosis in the brain and premature lethality in CPP32-deficient mice. Nature. 1996;384:368–372. doi: 10.1038/384368a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yuan J, Shaham S, Ledoux S, Ellis HM, Horvitz HR. The C. elegans cell death gene ced-3 encodes a protein similar to mammalian interleukin-1β-converting enzyme. Cell. 1993;75:641–652. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90485-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghayur T, Banerjee S, Hugunin M, Butler D, Herzog L, Carter A, Quintal L, Sekut L, Talanian R, Paskind M, Wong W, Kamen R, Tracey D, Alien H. Caspase-1 processes IFN-γ-inducing factor and regulates LPS-induced IFN-γ production. Nature. 1997;386:619–623. doi: 10.1038/386619a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong BKY, Ehrnhoefer DE, Graham RK, Martin DDO, Ladha S, Uribe V, Stanek LM, Franciosi S, Qiu X, Deng Y, Kovalik V, Zhang W, Pouladi MA, Shihabuddin LS, Hayden MR. Partial rescue of some features of Huntington Disease in the genetic absence of caspase-6 in YAC128 mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;76:24–36. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaushal V, Dye R, Pakavathkumar P, Foveau B, Flores J, Hyman B, Ghetti B, Koller BH, LeBlanc AC. Neuronal NLRP1 inflammasome activation of caspase-1 coordinately regulates inflammatory interleukin-1-beta production and axonal degeneration-associated caspase-6 activation. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22:1676–1686. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramcharitar J, Albrecht S, Afonso VM, Kaushal V, Bennett DA, LeBlanc AC. Cerebrospinal fluid tau cleaved by caspase-6 reflects brain levels and cognition in aging and Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013;72:824–832. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182a0a39f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schechter I, Berger A. On size of the active site in proteases. I Papain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1967;27:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(67)80055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stennicke HR, Renatus M, Meldal M, Salvesen GS. Internally quenched fluorescent peptide substrates disclose the subsite preferences of human caspases 1, 3, 6, 7 and 8. Biochem J. 2000;568:563–568. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Talanian RV, Quinlan C, Trautz S, Hackett MC, Mankovich JA, Banach D, Ghayur T, Brady KD, Wong WW. Substrate specificities of caspase family proteases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9677–9682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.9677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McStay GP, Salvesen GS, Green DR. Overlapping cleavage motif selectivity of caspases: implications for analysis of apoptotic pathways. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:322–331. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goode DR, Sharma AK, Hergenrother PJ. Using peptidic inhibitors to systematically probe the S1′ site of caspase-3 and caspase-7. Org Lett. 2005;7:3529–3532. doi: 10.1021/ol051287d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petrassi HM, Williams JA, Li J, Tumanut C, Ek J, Nakai T, Masick B, Backes BJ, Harris JL. A strategy to profile prime and non-prime proteolytic substrate specificity. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:3162–3166. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahrus S, Trinidad JC, Barkan DT, Sali A, Burlingame AL, Wells JA. Global sequencing of proteolytic cleavage sites in apoptosis by specific labeling of protein N termini. Cell. 2008;134:866–876. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Timmer JC, Salvesen GS. Gel Free Proteomics. Humana Press; New York, NY: 2011. N-terminomics: A high-content screen for protease substrates and their cleavage sites; pp. 243–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dix MM, Simon GM, Wang C, Okerberg E, Patricelli MP, Cravatt BF. Functional interplay between caspase cleavage and phosphorylation sculpts the apoptotic proteome. Cell. 2012;150:426–440. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schilling O, Overall CM. Proteome-derived, database-searchable peptide libraries for identifying protease cleavage sites. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:685–694. doi: 10.1038/nbt1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boucher D, Blais V, Denault JB. Caspase-7 uses an exosite to promote poly(ADP ribose) polymerase 1 proteolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:5669–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200934109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurokawa M, Ito T, Yang CS, Zhao C, Macintyre AN, Rizzieri DA, Rathmell JC, Deininger MW, Reya T, Kornbluth S. Engineering a BCR-ABL-activated caspase for the selective elimination of leukemic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:2300–2305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206551110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gray DC, Mahrus S, Wells JA. Activation of specific apoptotic caspases with an engineered small-molecule-activated protease. Cell. 2010;142:637–646. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walters J, Pop C, Scott FL, Drag M, Swartz P, Mattos C, Salvesen GS, Clark AC. A constitutively active and uninhibitable caspase-3 zymogen efficiently induces apoptosis. Biochem J. 2009;424:335–345. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Witkowski WA, Hardy JA. A designed redox-controlled caspase. Protein Sci. 2011;20:1421–31. doi: 10.1002/pro.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nicholls SB, Chu J, Abbruzzese G, Tremblay KD, Hardy JA. Mechanism of a genetically encoded dark-to-bright reporter for caspase activity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:24977–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.221648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu P, Nicholls SB, Hardy JA. A tunable, modular approach to fluorescent protease-activated reporters. Biophys J. 2013;104:1605–1614. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang R, Kim CS, Solfiell DJ, Rana S, Mout R, Velázquez-Delgado EM, Chompoosor A, Jeong Y, Yan B, Zhu ZJ, Kim C, Hardy JA, Rotello VM. Direct delivery of functional proteins and enzymes to the cytosol using nanoparticle-stabilized nanocapsules. ACS Nano. 2013;7:6667–6673. doi: 10.1021/nn402753y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim CS, Mout R, Zhao Y, Yeh YC, Tang R, Jeong Y, Duncan B, Hardy JA, Rotello VM. Co-delivery of protein and small molecule therapeutics using nanoparticle-stabilized nanocapsules. Bioconjug Chem. 2015;26:950–954. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ventura J, Eron SJ, González-Toro DC, Raghupathi K, Wang F, Hardy JA, Thayumanavan S. Reactive self-assembly of polymers and proteins to reversibly silence a killer protein. Biomacromolecules. 2015;16:3161–3171. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.5b00779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hedstrom L, Szilagyi L, Rutter WJ. Converting trypsin to chymotrypsin: the role of surface loops. Science (80- ) 1992;255:1249–53. doi: 10.1126/science.1546324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wells JA, Cunningham BC, Graycar TP, Estell DA. Recruitment of substrate-specificity properties from one enzyme into a related one by protein engineering. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1987;84:5167–5171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.15.5167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tomasic IB, Metcalf MC, Guce AI, Clark NE, Garman SC. Interconversion of the specificities of human lysosomal enzymes associated with Fabry and Schindler diseases. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:21560–21566. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.118588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tian WX, Tsou CL. Determination of the rate constant of enzyme modification by measuring the substrate reaction in the presence of the modifier. Biochemistry. 1982;21:1028–1032. doi: 10.1021/bi00534a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ekici ÖD, Li ZZ, Campbell AJ, James KE, Asgian JL, Mikolajczyk J, Salvesen GS, Ganesan R, Jelakovic S, Grütter MG, Powers JC. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of aza-peptide Michael acceptors as selective and potent inhibitors of caspases-2, -3, -6, -7, -8, -9, and -10. J Med Chem. 2006;49:5728–5749. doi: 10.1021/jm0601405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benkova B, Lozanov V, Ivanov IP, Mitev V. Evaluation of recombinant caspase specificity by competitive substrates. Anal Biochem. 2009;394:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Allsopp TE, McLuckie J, Kerr LE, Macleod M, Sharkey J, Kelly JS. Caspase 6 activity initiates caspase 3 activation in cerebellar granule cell apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2000;7:984–993. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Witkowski WA, Hardy JA. L2′ loop is critical for caspase-7 active site formation. Protein Sci. 2009;18:1459–68. doi: 10.1002/pro.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wei Y, Fox T, Chambers SP, Sintchak J, Coll JT, Golec JM, Swenson L, Wilson KP, Charifson PS. The structures of caspases-1, -3, -7 and -8 reveal the basis for substrate and inhibitor selectivity. Chem Biol. 2000;7:423–32. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Agniswamy J, Fang B, Weber IT. Plasticity of S2–S4 specificity pockets of executioner caspase-7 revealed by structural and kinetic analysis. FEBS J. 2007;274:4752–4765. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoshihara HAI, Mahrus S, Wells JA. Tags for labeling protein N-termini with subtiligase for proteomics. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:6000–6003. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barkan DT, Hostetter DR, Mahrus S, Pieper U, Wells JA, Craik CS, Sali A. Prediction of protease substrates using sequence and structure features. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1714–1722. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Agard NJ, Mahrus S, Trinidad JC, Lynn A, Burlingame AL, Wells JA. Global kinetic analysis of proteolysis via quantitative targeted proteomics. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:1913–1918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117158109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharma V, Panwar P, O’Donoghue AJ, Cui H, Guido RVC, Craik CS, Brömme D. Structural requirements for the collagenase and elastase activity of cathepsin K and its selective inhibition by an exosite inhibitor. Biochem J. 2015;465:163–173. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takahashi A, Alnemri ES, Lazebnik YA, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Litwack G, Moir RD, Goldman RD, Poirier GG, Kaufmann SH, Earnshaw WC. Cleavage of by Mch2 alpha but not CPP32: multiple interleukin 1 beta-converting enzyme-related proteases with distinct substrate recognition properties are active in apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:8395–8400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Velázquez-Delgado EM, Hardy JA. Phosphorylation regulates assembly of the caspase-6 substrate-binding groove. Structure. 2012;20:742–51. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.