Abstract

We developed a new method to calculate the atomic polarizabilities by fitting to the electrostatic potentials (ESPs) obtained from quantum mechanical (QM) calculations within the linear response theory. This parallels the conventional approach of fitting atomic charges based on electrostatic potentials from the electron density. Our ESP fitting is combined with the induced dipole model under the perturbation of uniform external electric fields of all orientations. QM calculations for the linear response to the external electric fields are used as input, fully consistent with the induced dipole model, which itself is a linear response model. The orientation of the uniform external electric fields is integrated in all directions. The integration of orientation and QM linear response calculations together makes the fitting results independent of the orientations and magnitudes of the uniform external electric fields applied. Another advantage of our method is that QM calculation is only needed once, in contrast to the conventional approach, where many QM calculations are needed for many different applied electric fields. The molecular polarizabilities obtained from our method show comparable accuracy with those from fitting directly to the experimental or theoretical molecular polarizabilities. Since ESP is directly fitted, atomic polarizabilities obtained from our method are expected to reproduce the electrostatic interactions better. Our method was used to calculate both transferable atomic polarizabilities for polarizable molecular mechanics’ force fields and nontransferable molecule-specific atomic polarizabilities.

I. INTRODUCTION

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is an important method for investigating biological systems.1,2 The accuracy of MD simulation depends on the force fields. Most empirical force fields use fixed partial charges on molecules (e.g., TIP3P3 and SPC4). These force fields are nonpolarizable force fields. Though non-polarizable force fields have achieved much success in the past decades, many challenges still remain. For example, one significant drawback of nonpolarizable force fields is that they cannot respond to the change of dielectric environment. However, due to the conformational changes, dielectric environment in biological systems may change significantly in the process of an MD simulation. The polarization effects are also crucial, for example, for the folding of membrane proteins in the lipid environment or RNA folding in the environment of divalent ions.5 In recent years, especially with the increasing power of computers, including polarization effects in MD simulations has been recognized as an effective method to further improve the accuracy of MD simulation results. Reviews accounting for polarization effects in MD simulations have been presented by Yu and van Gunsteren,6 Rick and Stuart,7 and González.8

Three most widely used polarizable models are fluctuating charge model,9,10 Drude model,11–13 and induced dipole model.14,15 The fluctuating charge model uses the chemical potential equalization principle16–18 to calculate the flexible atomic partial charges, which vary with the electrostatic environment. Atomic electronegativity (χ0) and hardness (J), two types of parameters in the fluctuating charge model, can be obtained via quantum mechanical (QM) calculations ( and J = IP − EA, where IP and EA denote the ionization potential and electron affinity).9 The disadvantage of this model is that the polarization effects are restricted by the molecular geometry. For example, for a planar molecule, the fluctuating charge model cannot represent the polarization out of the molecular plane, which needs additional fluctuating dipoles. The Drude model and induced dipole model are essentially equivalent.6,19,20 Both use dipole moments to represent polarization effects. The difference is in the models of the dipole: the induced dipole model uses atom-centered point dipole moments, while for the Drude model, the Drude particles attached to the atom sites through a spring are used to represent the polarization effects. In practice, the Drude model is easier to implement than the induced dipole model. In the present work, the scheme of the induced dipole model is more convenient and was chosen for our current implementation. However, the parameters obtained in the induced dipole model can be easily transformed into those in the Drude model.6

Besides these three main polarizable models, many other types of models have been developed. Within the atomic charge framework, Morita and Kato developed the charge response kernel model in which atomic charges linearly respond to the external potential.21,22 Piquemal et al. developed the SIBFA method which includes non-classical effects such as exchange-polarization.23–31

In the induced dipole model, the induced point dipole at atom site i is proportional to the electric field at the same site (μi = αiEi, where αi is the atomic polarizability of atom i). The atomic polarizabilities are the key parameters in the induced dipole model. In previous studies, the atomic polarizabilities were calculated by fitting to the molecular polarizabilities,20,32–35 which are obtained either from experimental results or from high-quality QM results. Soteras et al. calculated the atomic polarizabilities by fitting the induction energy computed in the perturbation theory.36 Kaminski et al. calculated the atomic polarizabilities by fitting to the electrostatic potential (ESP) produced by dipolar probes which are surrounding the molecules.37 Though fitting to molecular polarizabilities can also reproduce electrostatic interaction well, it is in an indirect way. Calculating atomic polarizabilities by direct fitting to electrostatic potential is what we desired in the present study.

However, the definition of atomic polarizabilities is not unique. Besides the “bare” atomic polarizabilities developed by Applequist,38 another type of distributed polarizabilities, which was first developed by Stone,54,55 is also widely used. Stone’s method combines the susceptibility function of the charge density56 and distributed multipole analysis57 to calculate distributed polarizabilities of an isolated molecule under an external perturbation. For practical purpose, Stone et al.58,59 devised the constrained density-fitting algorithm. Celebi et al.60 calculated the distributed polarizabilities by induction energy fitting.

In the current work, we developed a new method for the development of polarizable force fields, based on the following rationale. All polarizable force fields describe the linear response of the charge distribution of a molecule to the change in the external electrostatic field. Since this linear response is well described by quantum mechanical theory at many levels, we believe that polarizable force fields should be designed to approximate the QM linear response. Instead of using the linear response electron density, the optimal target of approximation is the electrostatic potential generated from the linear response electron density because the electrostatic potential is what enters into the interaction energy of the molecule with its environment. This is similar to the use of electrostatic potential to fit atomic charges in non-polarizable force fields. Thus our method calculates the atomic polarizabilities by ESP fitting within the quantum mechanical linear response theory. With the linear response function within density functional theory,39 QM calculations are only needed once in the fitting process for each molecule. It also makes our ESP fitting results independent of the orientations and magnitudes of the uniform external electric fields applied. These features lead to more efficient ESP fitting and accurate atomic polarizabilities. Both transferable atomic polarizabilities for the purpose of force fields and nontransferable atomic polarizabilities for specific molecules are calculated here. Our development of atomic polarizabilities based on linear response parallels the conventional approach of fitting atomic charges based on electrostatic potentials from the electron density. Our method should be useful for building the next generation of polarizable force fields.

II. METHODS

A. Induced dipole model

We first review the induced dipole model here. Consider a molecule of N atoms in a uniform external electric field. The induced dipoles are placed on each atom site and the induced dipole on atom p is given by

| (1) |

where αp is the atomic polarizability of atom p, Ep is the external electric field at atom p, μq is the dipole moment at atom q, and Tpq is the dipole field tensor,

| (2) |

where I is a 3 × 3 unit matrix, fe and ft are screening functions, rpq is the distance between atoms p and q, and x,y, and z are three components of rpq. In Applequist’s model,38 fe = 1 and ft = 1.

It has been noted that Applequist’s model may cause “polarization catastrophe,” which refers to “the infinite polarization by the cooperative interactions between two nearby induced dipoles.”32 To solve this problem, Thole developed two forms of screening functions to damp the short distance inductions.40 In the linear form,

| (3) |

In the exponential form,

| (4) |

Another form was used by Ren and Ponder,41–49 which was simplified by Wang et al.,32

| (5) |

where αp and αq are the atomic polarizabilities of atoms p and q, a is the screening factor, and rpq is the distance between atoms p and q.

Rearrange formula (1) to the matrix equation,

| (6) |

which can be expressed in compact matrix notation as

| (7) |

Let B = A−1,

| (8) |

Note that each Bij is a three by three matrix, associated with three spacial directions. Define a three by three matrix C as

| (9) |

Then isotropic molecular polarizability is given by

| (10) |

B. Linear response function

The linear response function (χ(r, r′)), defined as , represents the response of the electron density ρ(r) to the change of external electric potential v(r′). Within density functional theory, the analytic expression of χ(r, r′) is given as39

| (11) |

where M is a matrix depending on the approximate density functional chosen, which is given by

| (12) |

where

| (13) |

| (14) |

For explicit functionals of the electron density,

| (15) |

For functionals of the density matrix,

| (16) |

We use i, j, k, … for occupied states, a, b, c, … for unoccupied states, s, t, u, v for general states, and Greek letters σ, τ for spin labels. Details of the derivations of the above formula can be found in Yang’s paper.39 The linear response function only depends on the ground state properties of the molecules. Under a given perturbation δv(r), the change of electron density to first order is then given by

| (17) |

C. ESP fitting

In the current work, we performed the ESP fitting in two different ways to obtain atomic polarizabilities for molecular specific force fields and for general force fields. In the first approach, we fit the ESP for specific molecules. The molecule-specific fitting ensures that the atomic polarizabilities obtained are specifically optimized for a particular molecule. In determining atomic polarizabilities {αp}, we use the object function L, defined as the weighted squared difference between ϕESP, the electrostatic potential from the polarizable force field and ϕQM, that from QM linear response calculations, namely,

where ω(r) is a weight function at grid point r. The details of L are as follows:

| (18) |

where ra is the position of atom a, μa is the induced dipole moment on atom a, is the unit direction vector of the uniform external electric field, A is the matrix defined in Eq. (7), and δE is the magnitude of the uniform external electric field. The integration with respect to the solid angle (Ω) of the external perturbing field allows considering all the orientations of the perturbing field on equal footing.

Since

| (19) |

where are unit vectors in x, y, z directions, separately, we can define the following:

| (20) |

where x″, y″, and z″ are x, y, and z components of r″. Then L can be transformed into

| (21) |

Since the magnitude of the uniform external electric field, δE, can be taken out of the bracket, the ESP fitting results are independent of the magnitude of the uniform electric fields. The analytic gradient of L with respect to atomic polarizabilities {αp} and screening factor a, used in the optimization process, is given by

| (22) |

In the second approach, we fit the ESP for general force fields, which means that we aim to obtain atomic polarizabilities that are transferable. In this case, the total object function L is defined as

| (23) |

where n is the number of molecules in the training set and Li is the object function for molecule i, as defined in Eq. (21). The denominator of the factor represents the sum of weights of all grid points belonging to molecule i. This factor ensures that each molecule has the same weight in the fitting process.

In the conventional approach for developing force fields, atomic charges are fitted to the electrostatic potential generated from the electron density. In complete parallel, within our approach, atomic polarizabilities are fitted to the linear change of the electrostatic potential due to the applied external electric field, which is calculated from the linear response theory. This is the key feature of our work. While we focus on polarizable dipole model presently, our idea of fitting to the linear change of the electrostatic potential due to the applied external electric field, which is calculated from the linear response theory, can be applied to other polarizable models.

D. Computation details

We used the weight function developed by Hu et al. for electrostatic potential fitting of atomic charges,50 which is given by

| (24) |

where is the predefined electron density that is the sum of atomic electron densities, and ρref and σ are two parameters. By adjusting ρref and σ, a Gaussian-like weight function ω(r) is generated which weighs heavily on the points in the desired range. We performed a scanning over a large range of σ and ρref to look for the suitable parameters for dipole ESP fitting. It turns out that the ESP fitting quality is not significantly affected over a broad range of σ and ρref. This conclusion is similar to that in the paper of Hu et al.50 In our work, we chose σ = 1.0 and lnρref = − 11. In the spirit of Hu’s work,50 our object function is defined in the entire molecular volume space instead of discretely selected grid points surrounding the target molecule. The object function is thus rotationally invariant the to molecular orientation and continuously change with respect to the molecular geometry.50 We constructed an integration grid with standard 3D integration method used in density functional calculations and then computed electrostatic potentials on the grid points with the converged electron density.50 In the current work, the standard pruned (75 302) grid implemented in Gaussian was chosen. The small molecule set we used for ESP fitting and testing is the one developed by van Duijnen and Swart,33 which is a widely used molecule set for atomic polarizability parametrization. However, since the weight function of Hu et al.50 was only developed for the elements in the first three periods, molecules containing Br and I in the small molecule set are thus not used for fitting in current work.

Besides introducing the screening functions, excluding 1-2 (bonded) and 1-3 (separated by two bonds) induction can also reduce the risk of “polarization catastrophe.” Thus, we use eight induced dipole models based on whether 1-2 and 1-3 interactions are excluded and different screening functions are used. Table I summarizes the eight models we studied.

TABLE I.

Eight induced dipole models studied in the current work. Class 1 contains four models with 1-2 and 1-3 induction included. Class 2 contains four models with 1-2 and 1-3 induction excluded.

| Model | Class | Screening function | 1-2 (bond) | 1-3 (angle) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NTL | 1 | Thole’s linear model | On | On |

| NTE | 1 | Thole’s exponential model | On | On |

| NRE | 1 | Ren and Ponder’s exponential model | On | On |

| NAP | 1 | Applequist’s model | On | On |

| FTL | 2 | Thole’s linear model | Off | Off |

| FTE | 2 | Thole’s exponential model | Off | Off |

| FRE | 2 | Ren and Ponder’s exponential model | Off | Off |

| FAP | 2 | Applequist’s model | Off | Off |

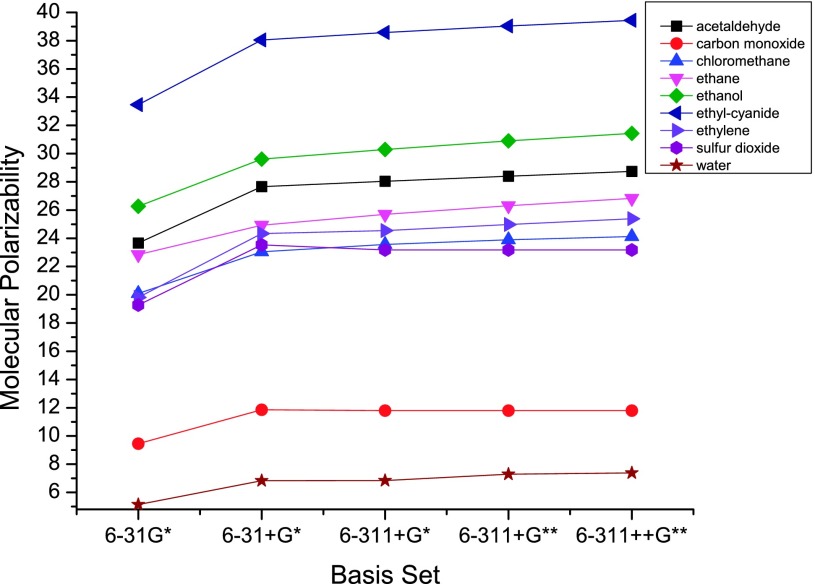

Figure 1 shows that the molecular polarizabilities vary with different basis sets. In the current work, the linear response function was calculated at the level of B3LYP/6-31 + G∗.51,52 All the molecular geometries were optimized at the same level before ESP fitting. Gaussian0353 was used to analytically calculate the molecular polarizabilities at the level of B3LYP/6-31 + G∗ for comparison.51,52

FIG. 1.

Dependence of molecular polarizabilities on the basis sets for nine molecules belonging to nine categories in the molecule set we used.

We used the quasi-Newton BFGS algorithm to optimize the object function, with analytic first order derivatives with respect to the parameters (atomic polarizabilities and screening factors). Though this algorithm cannot guarantee global minimal, we find that the convergence is satisfying after trying different initial guesses.

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The quality of the ESP fitting is assessed by the relative-root-mean-square-deviation (RRMSD), which is defined as

| (25) |

where N is the number of grid points, VESP,i is the electrostatic potential at grid i calculated from the induced dipoles, and VQM,i is the electrostatic potential calculated with the linear response function at grid i. As it is shown in Sec. II, after integrating the orientation in the 3-dimensional physical space, it is equivalent to applying the uniform external electric fields from three different directions. Therefore, summation is over 3N. Though we focus on fitting to the ESP, a physically reasonable set of atomic polarizabilities {αp} and screening factor a should also predict molecular polarizabilities well. Thus, we also calculated the average percentage error (APE) of the molecular polarizabilities, defined as

| (26) |

where αi is the molecular polarizabilities recovered from the atomic polarizabilities for molecule i, is the molecular polarizability for molecule i calculated by QM, and n is the number of molecules.

A. Atomic polarizabilities for force fields

Force fields are usually composed of bonded interaction (such as bond, angle, and dihedreal) and nonbonded interaction (electrostatic and van der Waals interaction). In some force fields, contribution to polarization from 1-2 (bond) and 1-3 (separated by two bonds) is absorbed by long-range polarization.32

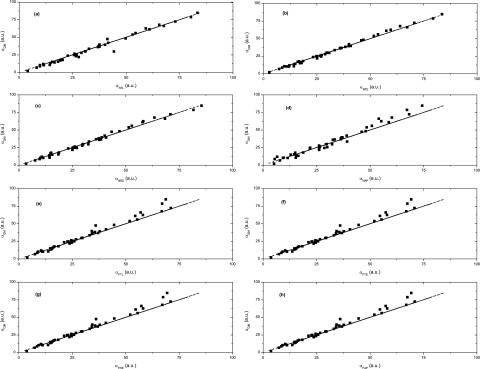

When fitting for the purpose of force fields, transferable atomic polarizabilities were generated by fitting small molecules of different categories together as indicated in Eq. (23). The atomic polarizabilities and screening factors obtained for eight induced dipole models are listed in Table II, in which the classification of atom types is the same as that used by Wang et al.32 For the convenience of comparison, we divide the eight induced dipole models into two classes based on whether 1-2 and 1-3 interactions are included. In many polarizable force fields, “the short range 1-2 and 1-3 interactions are excluded to reduce the potential of polarization catastrophe.”32 Class 1 contains four models (NTL, NTE, NRE, and NAP) including 1-2 and 1-3 interactions. Class 2 contains the other four models (FTL, FTE, FRE, and FAP) excluding 1-2 and 1-3 interactions. The scatter plots of molecular polarizabilities obtained from QM versus ESP fitting for the training set of eight models are shown in Figure 2. Statistical results of the training set are shown in Table III, and those for the testing set are shown in Table IV.

TABLE II.

Atomic polarizabilities and screening factors for eight models (atomic unit).

| Atom type | NTL | NTE | NRE | NAP | FTL | FTE | FRE | FAP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1a | 9.3114 | 7.4259 | 7.7525 | 2.8741 | 6.2867 | 6.2827 | 6.2827 | 6.2834 |

| C2b | 13.4049 | 10.3546 | 11.9081 | 4.5106 | 7.7322 | 7.7990 | 7.7990 | 7.8004 |

| C3c | 9.1352 | 8.2343 | 6.8914 | 5.0019 | 7.6621 | 7.7545 | 7.7599 | 7.7579 |

| H | 2.4456 | 1.4927 | 2.0576 | 1.0257 | 1.6972 | 1.6533 | 1.6547 | 1.6533 |

| NO | 5.7577 | 6.4642 | 5.8198 | 4.8365 | 4.6469 | 4.7016 | 4.7171 | 4.7049 |

| N | 6.9555 | 5.5249 | 6.3731 | 2.9754 | 5.2880 | 5.3217 | 5.3197 | 5.3217 |

| O2d | 5.2833 | 4.3817 | 4.7974 | 2.4841 | 4.0699 | 4.0794 | 4.0740 | 4.0794 |

| O3e | 5.2016 | 4.5349 | 4.2825 | 2.8890 | 3.7244 | 3.7548 | 3.7575 | 3.7561 |

| F | 2.6487 | 2.1237 | 1.8571 | 1.9563 | 2.3127 | 2.3005 | 2.2985 | 2.2998 |

| Cl | 11.8177 | 12.4075 | 11.7414 | 11.3601 | 11.5208 | 11.5376 | 11.5329 | 11.5356 |

| S4f | 15.1662 | 14.5805 | 13.7126 | 10.9094 | 12.9811 | 12.9690 | 12.9797 | 12.9669 |

| Sg | 16.8438 | 17.4161 | 15.2472 | 12.5357 | 15.0339 | 15.0522 | 15.0589 | 15.0488 |

| Screening factor | 1.7350 | 0.4130 | 1.1517 | N/A | 1.0000 | 0.1296 | 0.9959 | N/A |

C1: sp1 carbon.

C2: sp2 carbon.

C3: sp3 carbon.

O2: sp2 oxygen.

O3: sp3 oxygen.

S4: S in sulfone.

S: nonsulfone S.

FIG. 2.

Scatter plots of QM versus calculated molecular polarizabilities for the training set of all eight models. (a) NTL model. (b) NTE model. (c) NRE model. (d) NAP model. (e) FTL model. (f) FTE model. (g) FRE model. (h) FAP model.

TABLE III.

Statistical results of training set for eight models. VRRMSD: relative root mean square deviation. αAPE: average percentage error of molecular polarizabilities.

| Class 1 | Class 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | NTL | NTE | NRE | NAP | FTL | FTE | FRE | FAP |

| VRRMSD | 0.2531 | 0.2334 | 0.2208 | 0.2397 | 0.3657 | 0.3655 | 0.3657 | 0.3656 |

| αAPE (%) | 7.75 | 5.43 | 6.78 | 12.59 | 8.08 | 7.94 | 8.65 | 7.93 |

TABLE IV.

Statistical results of testing set for eight models. VRRMSD: relative root mean square deviation. αAPE: average percentage error of molecular polarizabilities.

| Class 1 | Class 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | NTL | NTE | NRE | NAP | FTL | FTE | FRE | FAP |

| VRRMSD | 0.1960 | 0.1813 | 0.1678 | 0.1822 | 0.3859 | 0.3841 | 0.3645 | 0.3856 |

| αAPE (%) | 4.61 | 2.93 | 4.17 | 8.93 | 9.87 | 9.69 | 8.79 | 9.74 |

Since many molecules in our molecule set are simple molecules, which only contain 1-2 and 1-3 interactions, fitting these molecules with models in Class 2 can cause large error, leading to relatively overall large errors, which is reflected in Tables III and IV. However, this phenomenon only means that models in Class 2 are not suitable for simple molecules. Actually, Wang et al.32 reported that models in Class 2 show lower αAPE when fitted with another molecule set in which molecules are more complex. For this reason, in the following discussion, we will not compare models between Class 1 and Class 2. For Class 1, as we can see from the results of both the training set (Table III) and testing set (Table IV), the three models with screening functions (NTL, NTE, and NRE) have similar αAPE, which is smaller than that of NAP. This means that short distance induction without screening can indeed cause large errors. For Class 2, all four models show similar αAPE, which means these four models have similar accuracy in predicting molecular polarizabilities. It was reported by van Duijnen and Swart33 that when fitting to ab initio molecular polarizabilities with NTL and NTE models using the same training set, αAPE is about 6%, which is of the same order as our results. VRRMSD is the quantity to assess the quality of ESP fitting. As it is shown in Tables III and IV, RRMSD for all eight models is small and about the same order, which means ESP fittings for eight models are all satisfactory. The errors then could be taken as the intrinsic limitation of polarizable dipole models.

It may be more meaningful to separately consider the αAPE for each category of molecules. As it is shown in Tables V and VI, αAPE for different categories varies much. Categories of simple molecules (e.g., diatomics and sulfurs) have much larger αAPE than other categories. This is because simple molecules, even fitted with models in Class 1, have fewer degrees of freedom to fit the ESP.

TABLE V.

Molecular polarizabilities and VRRMSD (relative root mean square deviation) for models in Class 1. αMol denotes the molecular polarizabilities in atomic unit. Molecules in italics are not in the training set.

| QM | NTL | NTE | NRE | NAP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecules | αMol | αMol | VRRMSD | αMol | VRRMSD | αMol | VRRMSD | αMol | VRRMSD | |

| Alcohols | ||||||||||

| 2-propanol | CH3CHOHCH3 | 42.08 | 40.50 | 0.1085 | 40.03 | 0.1192 | 40.32 | 0.0977 | 38.37 | 0.1070 |

| Ethanol | C2H5OH | 29.78 | 30.02 | 0.1574 | 29.59 | 0.1651 | 29.92 | 0.1514 | 28.70 | 0.1636 |

| Methanol | CH3OH | 17.96 | 19.05 | 0.2189 | 18.57 | 0.2051 | 18.80 | 0.1905 | 18.08 | 0.1937 |

| Cyclohexanol | C6H11OH | 72.47 | 68.85 | 0.0897 | 68.28 | 0.1022 | 68.43 | 0.0812 | 63.13 | 0.0957 |

| dev, % | 3.91 | 3.67 | 3.73 | 3.73 | ||||||

| Alkanes | ||||||||||

| Cyclohexane | C6H12 | 67.66 | 63.98 | 0.0924 | 63.79 | 0.1113 | 63.84 | 0.0824 | 59.52 | 0.0834 |

| Cyclopentane | C5H10 | 56.12 | 53.51 | 0.0944 | 53.42 | 0.1179 | 53.17 | 0.0788 | 49.98 | 0.0747 |

| Cyclopropane | C3H6 | 33.58 | 31.73 | 0.0959 | 33.40 | 0.1551 | 33.15 | 0.1123 | 38.43 | 0.3192 |

| Ethane | C2H6 | 25.06 | 25.33 | 0.1639 | 25.28 | 0.1900 | 25.43 | 0.1523 | 25.48 | 0.1791 |

| Hexane | C6H14 | 72.51 | 70.82 | 0.1230 | 70.56 | 0.1386 | 71.48 | 0.1319 | 68.10 | 0.1187 |

| Methane | CH4 | 13.39 | 14.44 | 0.2604 | 14.34 | 0.2669 | 14.31 | 0.2146 | 15.31 | 0.3019 |

| Propane | C3H8 | 37.0 | 36.22 | 0.1323 | 36.09 | 0.1518 | 36.37 | 0.1260 | 35.49 | 0.1275 |

| Dodecane | C12H26 | 144.57 | 143.36 | 142.77 | 145.27 | 135.90 | ||||

| Neopentane | C(CH3)4 | 61.51 | 57.37 | 0.0824 | 56.74 | 0.0914 | 56.77 | 0.0626 | 53.67 | 0.0723 |

| dev, % | 4.06 | 3.69 | 3.54 | 9.15 | ||||||

| Alkenes | ||||||||||

| Benzene | C6H6 | 66.08 | 67.89 | 0.2159 | 67.86 | 0.2110 | 67.68 | 0.2012 | 54.98 | 0.1973 |

| Chlorobenzene | C6H5Cl | 78.79 | 79.43 | 0.2042 | 79.82 | 0.1929 | 80.76 | 0.1888 | 67.90 | 0.1799 |

| Ethylene | C2H4 | 24.50 | 26.62 | 0.3679 | 27.36 | 0.3518 | 26.80 | 0.3368 | 29.27 | 0.6549 |

| Nitrobenzene | C6H5NO2 | 84.57 | 82.76 | 0.1915 | 82.87 | 0.1709 | 84.12 | 0.1677 | 71.77 | 0.1719 |

| Acetylene | C2H2 | 19.19 | 18.12 | 0.3288 | 19.07 | 0.2334 | 18.05 | 0.2106 | 14.82 | 0.2832 |

| m-dichlorobenzene | C6H4Cl2 | 92.34 | 91.17 | 0.1917 | 92.00 | 0.1763 | 94.23 | 0.1754 | 81.09 | 0.1726 |

| o-dichlorobenzene | C6H4Cl2 | 91.09 | 90.22 | 0.1901 | 91.45 | 0.1732 | 93.04 | 0.1771 | 80.11 | 0.1739 |

| dev, % | 3.16 | 2.72 | 3.57 | 16.03 | ||||||

| Carbonyls | ||||||||||

| N-methylformamide | HCONHCH3 | 36.60 | 36.59 | 0.2090 | 36.75 | 0.1828 | 38.24 | 0.2146 | 33.17 | 0.1384 |

| Acetaldehyde | HCOCH3 | 27.79 | 28.53 | 0.2484 | 28.95 | 0.2412 | 29.47 | 0.2677 | 26.38 | 0.1698 |

| Acetamide | CH3CONH2 | 36.17 | 35.81 | 0.1872 | 36.01 | 0.1884 | 37.43 | 0.2292 | 32.11 | 0.1655 |

| Acetone | CH3COCH3 | 39.25 | 39.27 | 0.1865 | 39.91 | 0.2012 | 40.85 | 0.2344 | 36.67 | 0.1097 |

| Formaldehyde | HCOH | 15.22 | 17.90 | 0.4763 | 17.80 | 0.3957 | 18.11 | 0.4387 | 14.67 | 0.2235 |

| Formamide | HCOH | 24.99 | 25.04 | 0.2554 | 25.00 | 0.2152 | 26.00 | 0.2570 | 21.66 | 0.2126 |

| N,N-dimethylformamide | HCON(CH3)2 | 48.22 | 47.61 | 0.1776 | 47.40 | 0.1512 | 49.16 | 0.1734 | 42.63 | 0.1141 |

| N-methylacetamide | CH3CONHCH3 | 47.68 | 47.65 | 0.1673 | 47.74 | 0.1636 | 49.93 | 0.2137 | 43.04 | 0.1253 |

| Carbonyl chloride | COCl2 | 39.06 | 36.91 | 0.2245 | 39.12 | 0.2341 | 39.60 | 0.2092 | 38.34 | 0.2456 |

| dev, % | 3.15 | 2.85 | 5.46 | 8.04 | ||||||

| Cyanides | ||||||||||

| Ethyl cyanide | C2H5CN | 38.34 | 36.71 | 0.1959 | 37.95 | 0.1941 | 37.50 | 0.1650 | 35.64 | 0.1712 |

| Methyl cyanide | CH3CN | 26.42 | 25.60 | 0.2476 | 26.83 | 0.2389 | 26.19 | 0.1958 | 25.59 | 0.2380 |

| Methyl dicyanide | CH2(CN)2 | 39.73 | 37.24 | 0.2374 | 40.04 | 0.2469 | 38.77 | 0.2023 | 36.36 | 0.2364 |

| Tert-butyl cyanide | (CH3)3CCN | 62.5 | 58.26 | 0.1219 | 59.06 | 0.1206 | 58.49 | 0.0921 | 54.26 | 0.1036 |

| Chloromethyl cyanide | CH2ClCN | 38.06 | 36.33 | 0.2132 | 37.63 | 0.2148 | 37.08 | 0.1760 | 35.82 | 0.2112 |

| Isopropyl cyanide | (CH3)2CHCN | 50.46 | 47.63 | 0.1507 | 48.72 | 0.1508 | 48.29 | 0.1231 | 45.26 | 0.1259 |

| Trichloromethyl cyanide | CCl3CN | 64.33 | 57.05 | 0.1550 | 58.81 | 0.1588 | 58.49 | 0.1341 | 56.92 | 0.1677 |

| dev, % | 5.98 | 3.14 | 3.98 | 8.51 | ||||||

| Diatomics | ||||||||||

| Carbon monoxide | CO | 11.93 | 11.92 | 0.3017 | 11.30 | 0.2285 | 10.86 | 0.1872 | 6.68 | 0.4007 |

| Chlorine | Cl2 | 21.81 | 25.35 | 0.3826 | 24.61 | 0.4852 | 24.47 | 0.3786 | 25.14 | 0.3574 |

| Hydrogen | H2 | 2.13 | 3.81 | 1.0352 | 2.85 | 0.7439 | 3.36 | 0.8808 | 3.65 | 0.5667 |

| Hydrogen chloride | HCl | 10.61 | 13.52 | 0.4729 | 14.02 | 0.5244 | 14.07 | 0.5204 | 14.29 | 0.5680 |

| Nitrogen | N2 | 10.5 | 11.06 | 0.411 | 10.48 | 0.2887 | 10.58 | 0.3239 | 8.71 | 0.3509 |

| Nitric oxide | NO | 10.37 | 9.32 | 0.2783 | 10.44 | 0.356 | 9.60 | 0.2553 | 10.83 | 0.5651 |

| Oxygen | O2 | 8.84 | 9.24 | 0.3218 | 8.56 | 0.2649 | 9.19 | 0.2427 | 5.56 | 0.3769 |

| dev, % | 20.37 | 12.58 | 17.67 | 31.99 | ||||||

| Halogens | ||||||||||

| Chloromethane | CH3Cl | 23.12 | 24.92 | 0.2283 | 24.86 | 0.2623 | 24.84 | 0.2132 | 25.06 | 0.2536 |

| Fluoromethane | CH3F | 14.34 | 15.71 | 0.2827 | 14.91 | 0.2562 | 14.64 | 0.2064 | 14.9 | 0.2476 |

| Tetrachloromethane | CCl4 | 61.2 | 55.69 | 0.1206 | 56.49 | 0.143 | 56.87 | 0.1146 | 57.14 | 0.1076 |

| Tetrafluoromethane | CF4 | 17.66 | 18.34 | 0.2398 | 16.66 | 0.1885 | 15.83 | 0.1458 | 15.63 | 0.1112 |

| Trichloromethane | CHCl3 | 48.33 | 45.56 | 0.1406 | 46.07 | 0.1825 | 46.37 | 0.1407 | 46.58 | 0.1407 |

| Trifluoromethane | CHF3 | 16.81 | 17.55 | 0.2431 | 16.07 | 0.2088 | 15.41 | 0.1666 | 15.2 | 0.161 |

| Dichloromethane | CH2Cl2 | 35.25 | 35.31 | 0.187 | 35.49 | 0.2375 | 35.64 | 0.188 | 35.72 | 0.2015 |

| Difluoromethane | CH2F2 | 15.52 | 16.71 | 0.2723 | 15.49 | 0.2388 | 15.02 | 0.1918 | 14.94 | 0.2156 |

| Trichlorofluoromethane | CFCl3 | 49.68 | 46.3 | 0.1281 | 46.7 | 0.1573 | 46.65 | 0.1298 | 47.03 | 0.1234 |

| dev, % | 6.11 | 4.53 | 5.53 | 6.00 | ||||||

| Sulfurs | ||||||||||

| Carbon disulfide | CS2 | 47.47 | 39.23 | 0.4059 | 45.23 | 0.3242 | 40.97 | 0.293 | 44.89 | 0.2038 |

| Sulfur dioxide | SO2 | 23.7 | 22.18 | 0.1954 | 23.15 | 0.1678 | 23.03 | 0.122 | 21.78 | 0.1464 |

| Sulfur hexafluoride | SF6 | 29.74 | 37.95 | 0.3745 | 31.19 | 0.1728 | 32.2 | 0.1923 | 32.45 | 0.1832 |

| dev, % | 17.13 | 3.97 | 8.26 | 7.55 | ||||||

| Various | ||||||||||

| Ammonia | NH3 | 10.71 | 10.93 | 0.2755 | 9.85 | 0.22 | 11.08 | 0.3048 | 8.51 | 0.286 |

| Carbon dioxide | CO2 | 15.01 | 15.52 | 0.3683 | 16.48 | 0.2562 | 15.44 | 0.2271 | 13.45 | 0.2214 |

| Dimethyl ether | CH3OCH3 | 29.93 | 30.27 | 0.177 | 29.78 | 0.1651 | 30.22 | 0.1599 | 28.91 | 0.1279 |

| Ethylene oxide | CH2OCH2 | 25.79 | 25.61 | 0.139 | 26.66 | 0.1909 | 26.42 | 0.1519 | 29.5 | 0.4394 |

| p-dioxane | (CH2)4O2 | 53.81 | 51.82 | 0.1186 | 51.48 | 0.1218 | 51.58 | 0.1046 | 47.85 | 0.1087 |

| Water | H2O | 6.91 | 7.98 | 0.3359 | 7.35 | 0.241 | 7.56 | 0.2974 | 7.34 | 0.4603 |

| Nitrous oxide | N2O | 17.4 | 15.58 | 0.3818 | 15.88 | 0.2363 | 15.94 | 0.2714 | 17.92 | 0.4057 |

| dev, % | 5.28 | 5.88 | 4.52 | 9.86 | ||||||

TABLE VI.

Molecular polarizabilities and VRRMSD (relative root mean square deviation) for models in Class 2. αMol denotes the molecular polarizabilities in atomic unit. Molecules in italics are not in the training set.

| QM | FTL | FTE | FRE | FAP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecules | αMol | αMol | VRRMSD | αMol | VRRMSD | αMol | VRRMSD | αMol | VRRMSD | |

| Alcohols | ||||||||||

| 2-propanol | CH3CHOHCH3 | 42.08 | 40.49 | 0.1952 | 40.44 | 0.1957 | 40.46 | 0.1961 | 40.45 | 0.1958 |

| Ethanol | C2H5OH | 29.78 | 29.28 | 0.2453 | 29.23 | 0.2451 | 29.25 | 0.2456 | 29.24 | 0.2453 |

| Methanol | CH3OH | 17.96 | 18.18 | 0.312 | 18.13 | 0.3103 | 18.14 | 0.3108 | 18.13 | 0.3104 |

| Cyclohexanol | C6H11OH | 72.47 | 82.19 | 0.569 | 81.19 | 0.5305 | 72.8 | 0.2355 | 81.8 | 0.5529 |

| dev, % | 5.02 | 4.68 | 1.77 | 4.88 | ||||||

| Alkanes | ||||||||||

| Cyclohexane | C6H12 | 67.66 | 67.17 | 0.1821 | 67.19 | 0.184 | 67.24 | 0.1846 | 67.21 | 0.1842 |

| Cyclopentane | C5H10 | 56.12 | 55.59 | 0.2169 | 55.6 | 0.2197 | 55.64 | 0.2203 | 55.61 | 0.22 |

| Cyclopropane | C3H6 | 33.58 | 33.19 | 0.2814 | 33.2 | 0.2834 | 33.22 | 0.2839 | 33.21 | 0.2836 |

| Ethane | C2H6 | 25.06 | 25.53 | 0.3016 | 25.45 | 0.301 | 25.47 | 0.3016 | 25.45 | 0.3012 |

| Hexane | C6H14 | 72.51 | 70.73 | 0.2078 | 70.64 | 0.2094 | 70.69 | 0.2099 | 70.66 | 0.2096 |

| Methane | CH4 | 13.39 | 14.45 | 0.406 | 14.37 | 0.4016 | 14.38 | 0.4023 | 14.37 | 0.4018 |

| Propane | C3H8 | 37 | 36.7 | 0.2394 | 36.62 | 0.2395 | 36.64 | 0.2401 | 36.63 | 0.2397 |

| Dodecane | C12H26 | 144.57 | 140.34 | 140.23 | 140.33 | 140.27 | ||||

| Neopentane | C(CH3)4 | 61.51 | 59.23 | 0.1759 | 59.15 | 0.1767 | 59.19 | 0.1771 | 59.16 | 0.1768 |

| dev, % | 2.50 | 2.45 | 2.42 | 2.43 | ||||||

| Alkenes | ||||||||||

| Benzene | C6H6 | 66.08 | 57.07 | 0.3439 | 57.21 | 0.3447 | 57.22 | 0.3447 | 57.22 | 0.3447 |

| Chlorobenzene | C6H5Cl | 78.79 | 67.04 | 0.373 | 67.24 | 0.3739 | 67.24 | 0.3739 | 67.25 | 0.3739 |

| Ethylene | C2H4 | 24.5 | 22.26 | 0.4298 | 22.22 | 0.4299 | 22.22 | 0.43 | 22.22 | 0.43 |

| Nitrobenzene | C6H5NO2 | 84.57 | 68.53 | 0.3823 | 68.79 | 0.3825 | 68.8 | 0.3825 | 68.8 | 0.3825 |

| Acetylene | C2H2 | 19.19 | 15.97 | 0.5453 | 15.87 | 0.5432 | 15.88 | 0.5432 | 15.87 | 0.5432 |

| m-dichlorobenzene | C6H4Cl2 | 92.34 | 77.04 | 0.3956 | 77.31 | 0.3968 | 77.3 | 0.3968 | 77.31 | 0.3968 |

| o-dichlorobenzene | C6H4Cl2 | 91.09 | 77.07 | 0.3896 | 77.34 | 0.3905 | 77.33 | 0.3905 | 77.34 | 0.3905 |

| dev, % | 15.06 | 14.96 | 14.95 | 14.95 | ||||||

| Carbonyls | ||||||||||

| N-methylformamide | HCONHCH3 | 36.6 | 33.37 | 0.3574 | 33.35 | 0.3579 | 33.35 | 0.358 | 33.35 | 0.358 |

| Acetaldehyde | HCOCH3 | 27.79 | 26.27 | 0.331 | 26.27 | 0.3317 | 26.27 | 0.3318 | 26.27 | 0.3318 |

| Acetamide | CH3CONH2 | 36.17 | 33.34 | 0.2965 | 33.32 | 0.2972 | 33.32 | 0.2973 | 33.32 | 0.2973 |

| Acetone | CH3COCH3 | 39.25 | 37.44 | 0.2744 | 37.43 | 0.2755 | 37.44 | 0.2757 | 37.44 | 0.2757 |

| Formaldehyde | HCOH | 15.22 | 15.2 | 0.4736 | 15.19 | 0.473 | 15.18 | 0.4729 | 15.19 | 0.4731 |

| Formamide | HCOH | 24.99 | 22.2 | 0.3774 | 22.17 | 0.3775 | 22.17 | 0.3774 | 22.18 | 0.3775 |

| N,N-dimethylformamide | HCON(CH3)2 | 48.22 | 44.64 | 0.3091 | 44.62 | 0.3102 | 44.63 | 0.3103 | 44.63 | 0.3102 |

| N-methylacetamide | CH3CONHCH3 | 47.68 | 44.61 | 0.2878 | 44.59 | 0.2886 | 44.6 | 0.2888 | 44.6 | 0.2887 |

| Carbonyl chloride | COCl2 | 39.06 | 34.84 | 0.4338 | 34.95 | 0.4356 | 34.94 | 0.4354 | 34.95 | 0.4356 |

| dev, % | 6.97 | 6.98 | 6.98 | 6.97 | ||||||

| Cyanides | ||||||||||

| Ethyl cyanide | C2H5CN | 38.34 | 35.47 | 0.3714 | 35.46 | 0.3718 | 35.47 | 0.3721 | 35.47 | 0.3719 |

| Methyl cyanide | CH3CN | 26.42 | 24.34 | 0.4703 | 24.33 | 0.4702 | 34.34 | 0.4705 | 24.33 | 0.4703 |

| Methyl dicyanide | CH2(CN)2 | 39.73 | 34.25 | 0.4645 | 34.32 | 0.4656 | 34.32 | 0.4657 | 34.32 | 0.4657 |

| Tert-butyl cyanide | (CH3)3CCN | 62.5 | 57.94 | 0.2529 | 57.94 | 0.2539 | 57.97 | 0.2543 | 57.95 | 0.2541 |

| Chloromethyl cyanide | CH2ClCN | 38.06 | 34.18 | 0.4255 | 34.23 | 0.4264 | 34.23 | 0.4265 | 34.23 | 0.4265 |

| Isopropyl cyanide | (CH3)2CHCN | 50.46 | 46.68 | 0.2979 | 46.67 | 0.2987 | 46.69 | 0.299 | 46.68 | 0.2988 |

| Trichloromethyl cyanide | CCl3CN | 64.33 | 53.87 | 0.3238 | 84.05 | 0.3248 | 54.04 | 0.3248 | 54.05 | 0.3249 |

| dev, % | 10.06 | 9.98 | 9.96 | 9.98 | ||||||

| Diatomics | ||||||||||

| Carbon monoxide | CO | 11.93 | 10.36 | 0.2708 | 10.36 | 0.271 | 10.36 | 0.2708 | 10.36 | 0.271 |

| Chlorine | Cl2 | 21.81 | 23.04 | 0.5912 | 23.08 | 0.5923 | 23.07 | 0.592 | 23.07 | 0.5922 |

| Hydrogen | H2 | 2.13 | 3.39 | 1.0817 | 3.31 | 1.064 | 3.31 | 1.0645 | 3.31 | 1.0639 |

| Hydrogen chloride | HCl | 10.61 | 13.22 | 0.5624 | 13.19 | 0.5585 | 13.19 | 0.5582 | 13.19 | 0.5583 |

| Nitrogen | N2 | 10.5 | 10.58 | 0.49 | 10.64 | 0.4956 | 10.64 | 0.4953 | 10.64 | 0.4956 |

| Nitric oxide | NO | 10.37 | 8.72 | 0.4003 | 8.78 | 0.4037 | 8.79 | 0.4045 | 8.78 | 0.4039 |

| Oxygen | O2 | 8.84 | 8.14 | 0.4697 | 8.16 | 0.47 | 8.15 | 0.4698 | 8.16 | 0.47 |

| dev, % | 18.16 | 17.58 | 17.58 | 17.57 | ||||||

| Halogens | ||||||||||

| Chloromethane | CH3Cl | 23.12 | 24.28 | 0.3954 | 24.25 | 0.3947 | 24.26 | 0.395 | 24.25 | 0.3948 |

| Fluoromethane | CH3F | 14.34 | 15.07 | 0.3865 | 15.02 | 0.3841 | 15.02 | 0.3846 | 15.02 | 0.3843 |

| Tetrachloromethane | CCl4 | 61.2 | 53.75 | 0.2703 | 53.9 | 0.2716 | 53.89 | 0.2715 | 53.9 | 0.2716 |

| Tetrafluoromethane | CF4 | 17.66 | 16.91 | 0.3005 | 16.96 | 0.3038 | 16.95 | 0.3037 | 16.96 | 0.3039 |

| Trichloromethane | CHCl3 | 48.33 | 43.92 | 0.3263 | 44.02 | 0.3279 | 44.01 | 0.3278 | 44.02 | 0.3279 |

| Trifluoromethane | CHF3 | 16.81 | 16.3 | 0.3201 | 16.31 | 0.3215 | 16.31 | 0.3216 | 16.31 | 0.3216 |

| Dichloromethane | CH2Cl2 | 35.25 | 34.1 | 0.3826 | 34.14 | 0.3836 | 34.13 | 0.3837 | 34.14 | 0.3837 |

| Difluoromethane | CH2F2 | 15.52 | 15.68 | 0.3577 | 15.66 | 0.3574 | 15.67 | 0.3577 | 15.66 | 0.3575 |

| Trichlorofluoromethane | CFCl3 | 49.68 | 44.54 | 0.2823 | 44.67 | 0.2841 | 44.66 | 0.2841 | 44.67 | 0.2841 |

| dev, % | 5.93 | 5.73 | 5.76 | 5.73 | ||||||

| Sulfurs | ||||||||||

| Carbon disulfide | CS2 | 47.47 | 36.35 | 0.6314 | 36.39 | 0.6315 | 36.40 | 0.6315 | 36.38 | 0.6315 |

| Sulfur dioxide | SO2 | 23.70 | 21.12 | 0.3965 | 21.13 | 0.3965 | 21.13 | 0.3965 | 21.13 | 0.3965 |

| Sulfur hexafluoride | SF6 | 29.74 | 28.91 | 0.1825 | 28.86 | 0.1816 | 28.85 | 0.1815 | 28.85 | 0.1814 |

| dev, % | 12.37 | 12.38 | 12.39 | 12.40 | ||||||

| Various | ||||||||||

| Ammonia | NH3 | 10.71 | 10.38 | 0.3042 | 10.28 | 0.2973 | 10.28 | 0.2974 | 10.28 | 0.2973 |

| Carbon dioxide | CO2 | 15.01 | 14.43 | 0.5783 | 14.44 | 0.5786 | 14.43 | 0.5783 | 14.44 | 0.5787 |

| Dimethyl ether | CH3OCH3 | 29.93 | 29.38 | 0.2601 | 28.33 | 0.2595 | 29.35 | 0.2599 | 29.33 | 0.2596 |

| Ethylene oxide | CH2OCH2 | 25.79 | 25.84 | 0.3183 | 25.88 | 0.3198 | 25.9 | 0.3203 | 25.89 | 0.32 |

| p-dioxane | (CH2)4O2 | 53.81 | 52.28 | 0.1832 | 52.36 | 0.1846 | 52.39 | 0.1851 | 52.37 | 0.1848 |

| Water | H2O | 6.91 | 7.12 | 0.3171 | 7.06 | 0.3094 | 7.07 | 0.3098 | 7.06 | 0.3094 |

| Nitrous oxide | N2O | 17.4 | 14.65 | 0.6124 | 14.72 | 0.6141 | 14.71 | 0.6139 | 14.72 | 0.6141 |

| dev, % | 4.38 | 4.35 | 4.38 | 4.35 | ||||||

B. Molecule specific atomic polarizabilities

For the molecule-specific fitting, atomic polarizabilities and screening factors are optimized for individual molecules. There are nine categories of molecules in the molecule set. In order to compare the results of molecule-specific fitting with force field fitting, we chose nine molecules out, one from each category. Take the NTE model as an example. The fitting results are shown in Table VII. The nine molecules we used for comparison are originally in the training set of force field fitting. As it 1is shown in Table VII, molecule-specific fitting can further improve the accuracy of ESP fitting (i.e., smaller VRRMSD). The relative percentage error of the eight molecules in Table VII (except hydrogen) ranges from 0.7% to 4.8%. This shows comparable accuracy with that obtained in Celebi’s work60 for distributed polarizabilities, which are also calculated in the molecule-specific way. The large relative percentage error of hydrogen is mainly due to its simple structure. Furthermore, molecular polarizabilities obtained from the molecule-specific fitting are better approximations to the QM results. Molecule-specific fitting is particularly useful when the polarization effects of specific molecules need to be accurately evaluated.

TABLE VII.

Comparison between molecule-specific fitting and force field fitting for NTE model. The nine molecules are chosen from nine different categories in the molecule set and are from the training set of the force field fitting. αMol denotes the molecular polarizabilities in atomic unit. VRRMSD: relative root mean square deviation.

| QM | Molecule-specific fitting | Force field fitting | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| αMol | αMol | VRRMSD | αMol | VRRMSD | ||

| Ethanol | C2H5OH | 29.78 | 29.99 | 0.1373 | 29.59 | 0.1651 |

| Ethane | C2H6 | 25.06 | 24.83 | 0.1368 | 25.28 | 0.1900 |

| Ethylene | C2H4 | 24.50 | 24.26 | 0.3064 | 27.36 | 0.3518 |

| Acetaldehyde | HCOCH3 | 27.79 | 27.59 | 0.1620 | 28.95 | 0.2412 |

| Ethyl cyanide | C2H5CN | 38.34 | 37.72 | 0.1673 | 37.95 | 0.1941 |

| Hydrogen | H2 | 2.13 | 2.94 | 0.4206 | 2.85 | 0.7439 |

| Chloromethane | CH3Cl | 23.12 | 22.46 | 0.2059 | 24.86 | 0.2623 |

| Sulfur dioxide | SO2 | 23.70 | 23.38 | 0.1617 | 23.15 | 0.1678 |

| Water | H2O | 6.91 | 7.24 | 0.2185 | 7.35 | 0.2410 |

In the electrostatic potential fitting of atomic charge, due to insufficient number of grids on the ESP surface, atoms buried in molecules are usually not well fitted.61 As our polarizable force field was developed as parallel to the electrostatic potential fitting of atomic charges, it should share this problem. However, the uncertainty of buried charges can be regularized. It was reported that to get around the “buried” atom problem, “the most robust technique consisted of constraining the fitting procedure to reproduce a target charge on non-hydrogen atoms.”61–63 The molecule set we used for training and testing in our paper consisted of small molecules, the “buried” atom problem does not affect our results. For large molecules, similar regularization procedure can be adopted to deal with the “buried” atom problem.

In this work, atomic polarizabilities were calculated by ESP fitting after applying uniform external electric fields. In the ideal situation, atomic polarizabilities calculated should not depend on the magnitudes and orientations of the uniform external electric fields. We took two steps to remove the dependence on the orientation of applied electric fields. First, we used the weight function developed by Hu et al.50 It has been shown that the object function defined in their way shows little molecule orientation dependence.50 Second, the orientation of the applied electric fields was integrated in the 3-dimensional physical space. In order to be independent of the magnitude of the applied electric fields (δE), we fit the ESP within the linear response level. Thus, as indicated by Eq. (21), δE does not affect the optimization of the object function. Actually, there is a deeper reason that the linear response function can be combined with the induced dipole models in the ESP fitting process. The induced dipole model itself is essentially a linear response model (μi = αiEi), which is consistent with the linear response function. But we need to be aware of the limitation with the ESP fitting method. The fitting quality depends on the choice of the basis sets in the quantum mechanical linear response function calculations, the choice of grid points, and the definition of the object function L itself.

IV. CONCLUSION

In summary, we developed a new method of calculating the atomic polarizabilities by ESP fitting with the linear response theory. The method was used for developing atomic polarizabilities for both force fields and specific molecules using eight induced dipole models. Fitting for force fields can generate transferable atomic polarizabilities, which can be used for the construction of new force fields, while fitting for specific molecules can generate nontransferable atomic polarizabilities specifically optimized for individual molecules. With the introduction of the linear response function, atomic polarizabilities can be calculated accurately and efficiently, in parallel to obtaining atomic charges based on fitting electrostatic potentials.

The present method for calculating atomic polarizabilities parallels the method for fitting atomic charges using ESP, which is widely used in force field development. Atomic polarizabilities obtained here can be directly combined with any existing ESP charges without the need to recalculate the ESP charges. We expect our development will provide a very useful tool for developing polarizable force fields.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Lin Shen for helpful discussion. Financial support from National Institutes of Health (Grant No. R01 GM061870-13) is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.van Gunsteren W. F. and Berendsen H. J. C., “Computer simulation of molecular dynamics: Methodology, applications, and perspectives in chemistry,” Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 29(9), 992–1023 (1990). 10.1002/anie.199009921 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karplus M. and McCammon J. A., “Molecular dynamics simulations of biomolecules,” Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 9(9), 646–652 (2002). 10.1038/nsb0902-646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jorgensen W. L., Chandrasekhar J., Madura J. D., Impey R. W., and Klein M. L., “Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water,” J. Chem. Phys. 79(2), 926–935 (1983). 10.1063/1.445869 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berendsen H. J. C., Postma J. P. M., van Gunsteren W. F., and Hermans J., Intermolecular Forces (Springer-Science+business Media, B.V., 1981), pp. 331–342. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cieplak P., Dupradeau F.-Y., Duan Y., and Wang J., “Polarization effects in molecular mechanical force fields,” J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 21(33), 333102 (2009). 10.1088/0953-8984/21/33/333102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu H. and van Gunsteren W. F., “Accounting for polarization in molecular simulation,” Comput. Phys. Commun. 172(2), 69–85 (2005). 10.1016/j.cpc.2005.01.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rick S. W. and Stuart S. J., Potentials and Algorithms for Incorporating Polarizability in Computer Simulations (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2003), pp. 89–146. [Google Scholar]

- 8.González M. A., “Force fields and molecular dynamics simulations,” JDN 12, 169–200 (2011). 10.1051/sfn/201112009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rappé A. K. and Goddard W. A., “Charge equilibration for molecular dynamics simulations,” J. Phys. Chem. 95(8), 3358–3363 (1991). 10.1021/j100161a070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rick S. W., Stuart S. J., and Berne B. J., “Dynamical fluctuating charge force fields: Application to liquid water,” J. Chem. Phys. 101(7), 6141–6156 (1994). 10.1063/1.468398 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drude P., The Theory of Optics (Longmans, Green, and Company, New York, 1902). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang K. and Born M., Dynamic Theory fo Crystal Lattices (Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 1954). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Straatsma T. P. and McCammon J. A., “Molecular dynamics simulations with interaction potentials including polarization development of a noniterative method and application to water,” Mol. Simul. 5(3–4), 181–192 (1990). 10.1080/08927029008022130 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vesely F. J., “N-particle dynamics of polarizable Stockmayer-type molecules,” J. Comput. Phys. 24(4), 361–371 (1977). 10.1016/0021-9991(77)90028-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Belle D., Froeyen M., Lippens G., and Wodak S. J., “Molecular dynamics simulation of polarizable water by an extended Lagrangian method,” Mol. Phys. 77(2), 239–255 (1992). 10.1080/00268979200102421 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mortier W. J., Van Genechten K., and Gasteiger J., “Electronegativity equalization: Application and parametrization,” J. Am. Chem. Soc. 107(4), 829–835 (1985). 10.1021/ja00290a017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mortier W. J., Ghosh S. K., and Shankar S., “Electronegativity-equalization method for the calculation of atomic charges in molecules,” J. Am. Chem. Soc. 108(15), 4315–4320 (1986). 10.1021/ja00275a013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.York D. M. and Yang W., “A chemical potential equalization method for molecular simulations,” J. Chem. Phys. 104(1), 159–172 (1996). 10.1063/1.470886 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmollngruber M., Lesch V., Schroder C., Heuer A., and Steinhauser O., “Comparing induced point-dipoles and drude oscillators,” Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 14297–14306 (2015). 10.1039/C4CP04512B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J., Cieplak P., Cai Q., Hsieh M.-J., Wang J., Duan Y., and Luo R., “Development of polarizable models for molecular mechanical calculations. III. Polarizable water models conforming to thole polarization screening schemes,” J. Phys. Chem. B 116(28), 7999–8008 (2012). 10.1021/jp212117d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morita A. and Kato S., “Ab initio molecular orbital theory on intramolecular charge polarization: Effect of hydrogen abstraction on the charge sensitivity of aromatic and nonaromatic species,” J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119(17), 4021–4032 (1997). 10.1021/ja9635342 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morita A. and Kato S., “The charge response kernel with modified electrostatic potential charge model,” J. Phys. Chem. A 106(15), 3909–3916 (2002). 10.1021/jp014114o [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gresh N., Cisneros G. A., Darden T. A., and Piquemal J.-P., “Anisotropic, polarizable molecular mechanics studies of inter- and intramolecular interactions and ligand-macromolecule complexes. A bottom-up strategy,” J. Chem. Theory Comput. 3(6), 1960–1986 (2007). 10.1021/ct700134r [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antony J., Piquemal J.-P., and Gresh N., “Complexes of thiomandelate and captopril mercaptocarboxylate inhibitors to metallo-β-lactamase by polarizable molecular mechanics. Validation on model binding sites by quantum chemistry,” J. Comput. Chem. 26(11), 1131–1147 (2005). 10.1002/jcc.20245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piquemal J.-P., Cisneros G. A., Reinhardt P., Gresh N., and Darden T. A., “Towards a force field based on density fitting,” J. Chem. Phys. 124(10), 104101 (2006). 10.1063/1.2173256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jenkins L. M. M., Hara T., Durell S. R., Hayashi R., Inman J. K., Piquemal J.-P., Gresh N., and Appella E., “Specificity of acyl transfer from 2-mercaptobenzamide thioesters to the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein,” J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129(36), 11067–11078 (2007). 10.1021/ja071254o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piquemal J.-P., Chelli R., Procacci P., and Gresh N., “Key role of the polarization anisotropy of water in modeling classical polarizable force fields,” J. Phys. Chem. A 111(33), 8170–8176 (2007). 10.1021/jp072687g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piquemal J.-P., Chevreau H., and Gresh N., “Toward a separate reproduction of the contributions to the Hartree-Fock and DFT intermolecular interaction energies by polarizable molecular mechanics with the SIBFA potential,” J. Chem. Theory Comput. 3(3), 824–837 (2007). 10.1021/ct7000182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu J. C., Piquemal J.-P., Chaudret R., Reinhardt P., and Ren P., “Polarizable molecular dynamics simulation of Zn(II) in water using the AMOEBA force field,” J. Chem. Theory Comput. 6(7), 2059–2070 (2010). 10.1021/ct100091j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Q., Rackers J. A., He C., Qi R., Narth C., Lagardere L., Gresh N., Ponder J. W., Piquemal J.-P., and Ren P., “General model for treating short-range electrostatic penetration in a molecular mechanics force field,” J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11(6), 2609–2618 (2015). 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Narth C., Lagardère L., Polack É., Gresh N., Wang Q., Bell D. R., Rackers J. A., Ponder J. W., Ren P. Y., and Piquemal J.-P., “Scalable improvement of SPME multipolar electrostatics in anisotropic polarizable molecular mechanics using a general short-range penetration correction up to quadrupoles,” J. Comput. Chem. 37(5), 494–506 (2016). 10.1002/jcc.24257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang J., Cieplak P., Li J., Hou T., Luo R., and Duan Y., “Development of polarizable models for molecular mechanical calculations. I. Parameterization of atomic polarizability,” J. Phys. Chem. B 115(12), 3091–3099 (2011). 10.1021/jp112133g [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Duijnen P. Th. and Swart M., “Molecular and atomic polarizabilities: Thole’s model revisited,” J. Phys. Chem. A 102(14), 2399–2407 (1998). 10.1021/jp980221f [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang J., Cieplak P., Li J., Wang J., Cai Q., Hsieh M., Lei H., Luo R., and Duan Y., “Development of polarizable models for molecular mechanical calculations. II. Induced dipole models significantly improve accuracy of intermolecular interaction energies,” J. Phys. Chem. B 115(12), 3100–3111 (2011). 10.1021/jp1121382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang J., Cieplak P., Li J., Cai Q., Hsieh M.-J., Luo R., and Duan Y., “Development of polarizable models for molecular mechanical calculations. IV. van der Waals parametrization,” J. Phys. Chem. B 116(24), 7088–7101 (2012). 10.1021/jp3019759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soteras I., Curutchet C., Bidon-Chanal A., Dehez F., Ángyán J. G., Orozco M., Chipot C., and Luque F. J., “Derivation of distributed models of atomic polarizability for molecular simulations,” J. Chem. Theory Comput. 3(6), 1901–1913 (2007). 10.1021/ct7001122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaminski G. A., Stern H. A., Berne B. J., and Friesner R. A., “Development of an accurate and robust polarizable molecular mechanics force field from ab initio quantum chemistry,” J. Phys. Chem. A 108(4), 621–627 (2004). 10.1021/jp0301103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Applequist J., Carl J. R., and Fung K.-K., “Atom dipole interaction model for molecular polarizability. Application to polyatomic molecules and determination of atom polarizabilities,” J. Am. Chem. Soc. 94(9), 2952–2960 (1972). 10.1021/ja00764a010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang W., Cohen A. J., De Proft F., and Geerlings P., “Analytical evaluation of Fukui functions and real-space linear response function,” J. Chem. Phys. 136(14), 144110 (2012). 10.1063/1.3701562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thole B. T., “Molecular polarizabilities calculated with a modified dipole interaction,” Chem. Phys. 59(3), 341–350 (1981). 10.1016/0301-0104(81)85176-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ren P. and Ponder J. W., “Consistent treatment of inter- and intramolecular polarization in molecular mechanics calculations,” J. Comput. Chem. 23(16), 1497–1506 (2002). 10.1002/jcc.10127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grossfield A., Ren P., and Ponder J. W., “Ion solvation thermodynamics from simulation with a polarizable force field,” J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125(50), 15671–15682 (2003). 10.1021/ja037005r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ren P. and Ponder J. W., “Polarizable atomic multipole water model for molecular mechanics simulation,” J. Phys. Chem. B 107(24), 5933–5947 (2003). 10.1021/jp027815+ [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schnieders M. J., Baker N. A., Ren P., and Ponder J. W., “Polarizable atomic multipole solutes in a Poisson-Boltzmann continuum,” J. Chem. Phys. 126(12), 124114 (2007). 10.1063/1.2714528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schnieders M. J. and Ponder J. W., “Polarizable atomic multipole solutes in a generalized Kirkwood continuum,” J. Chem. Theory Comput. 3(6), 2083–2097 (2007). 10.1021/ct7001336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ren P., Wu C., and Ponder J. W., “Polarizable atomic multipole-based molecular mechanics for organic molecules,” J. Chem. Theory Comput. 7(10), 3143–3161 (2011). 10.1021/ct200304d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi Y., Xia Z., Zhang J., Best R., Wu C., Ponder J. W., and Ren P., “Polarizable atomic multipole-based AMOEBA force field for proteins,” J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9(9), 4046–4063 (2013). 10.1021/ct4003702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang C., Lu C., Wang Q., Ponder J. W., and Ren P., “Polarizable multipole-based force field for dimethyl and trimethyl phosphate,” J. Chem. Theory Comput. 11(11), 5326–5339 (2015). 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Laury M. L., Wang L.-P., Pande V. S., Head-Gordon T., and Ponder J. W., “Revised parameters for the AMOEBA polarizable atomic multipole water model,” J. Phys. Chem. B 119(29), 9423–9437 (2015). 10.1021/jp510896n [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu H., Lu Z., and Yang W., “Fitting molecular electrostatic potentials from quantum mechanical calculations,” J. Chem. Theory Comput. 3(3), 1004–1013 (2007). 10.1021/ct600295n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee C., Yang W., and Parr R. G., “Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density,” Phys. Rev. B 37, 785–789 (1988). 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Becke A. D., “Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange,” J. Chem. Phys. 98(7), 5648–5652 (1993). 10.1063/1.464913 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Frisch M. J., Trucks G. W., Schlegel H. B., Scuseria G. E., Robb M. A., Cheeseman J. R., J. A. Montgomery, Jr., Vreven T., Kudin K. N., Burant J. C., Millam J. M., Iyengar S. S., Tomasi J., Barone V., Mennucci B., Cossi M., Scalmani G., Rega N., Petersson G. A., Nakatsuji H., Hada M., Ehara M., Toyota K., Fukuda R., Hasegawa J., Ishida M., Nakajima T., Honda Y., Kitao O., Nakai H., Klene M., Li X., Knox J. E., Hratchian H. P., Cross J. B., Bakken V., Adamo C., Jaramillo J., Gomperts R., Stratmann R. E., Yazyev O., Austin A. J., Cammi R., Pomelli C., Ochterski J. W., Ayala P. Y., Morokuma K., Voth G. A., Salvador P., Dannenberg J. J., Zakrzewski V. G., Dapprich S., Daniels A. D., Strain M. C., Farkas O., Malick D. K., Rabuck A. D., Raghavachari K., Foresman J. B., Ortiz J. V., Cui Q., Baboul A. G., Clifford S., Cioslowski J., Stefanov B. B., Liu G., Liashenko A., Piskorz P., Komaromi I., Martin R. L., Fox D. J., Keith T., Al-Laham M. A., Peng C. Y., Nanayakkara A., Challacombe M., Gill P. M. W., Johnson B., Chen W., Wong M. W., Gonzalez C., and Pople J. A., gaussian 03, Revision D.02, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford, CT, 2004.

- 54.Stone A. J., “Distributed polarizabilities,” Mol. Phys. 56(5), 1065–1082 (1985). 10.1080/00268978500102901 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stone A. J. and Alderton M., “Distributed multipole analysis,” Mol. Phys. 56(5), 1047–1064 (1985). 10.1080/00268978500102891 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maaskant W. J. A. and Oosterhoof L. J., “Theory of optical rotatory power,” Mol. Phys. 8(4), 319–344 (1964). 10.1080/00268976400100371 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stone A. J., “Distributed multipole analysis, or how to describe a molecular charge distribution,” Chem. Phys. Lett. 83(2), 233–239 (1981). 10.1016/0009-2614(81)85452-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Misquitta A. J. and Stone A. J., “Distributed polarizabilities obtained using a constrained density-fitting algorithm,” J. Chem. Phys. 124(2), 024111 (2006). 10.1063/1.2150828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Williams G. J. and Stone A. J., “Distributed dispersion: A new approach,” J. Chem. Phys. 119(9), 4620 (2003). 10.1063/1.1594722 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Celebi N., Angyan J. G., Dehez F., Millot C., and Chipot C., “Distributed polarizabilities derived from induction energies: A finite perturbation approach,” J. Chem. Phys. 112(6), 2709 (2000). 10.1063/1.480845 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rigby J. and Izgorodina E. I., “Assessment of atomic partial charge schemes for polarisation and charge transfer effects in ionic liquids,” Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 1632–1646 (2013). 10.1039/c2cp42934a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bayly C. I., Cieplak P., Cornell W., and Kollman P. A., “A well-behaved electrostatic potential based method using charge restraints for deriving atomic charges: The resp model,” J. Phys. Chem. 97(40), 10269–10280 (1993). 10.1021/j100142a004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cornell W. D., Cieplak P., Bayly C. I., and Kollmann P. A., “Application of resp charges to calculate conformational energies, hydrogen bond energies, and free energies of solvation,” J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115(21), 9620–9631 (1993). 10.1021/ja00074a030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]