Abstract

Length of stay (LOS), 30-day mortality, and 30-day readmission rates have not been compared between Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure (HF) with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and beneficiaries with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), even though HFpEF is common among patients with HF. In order to determine whether type of HF (HFrEF or HFpEF) was associated with length of stay (LOS), 30-day mortality, and 30-day readmission, we used a cohort of 19,477 Medicare beneficiaries admitted to the hospital and discharged alive with a primary discharge diagnosis of HF between 2007 and 2011. Gamma regression, Poisson regression, and Cox proportional hazards with a competing risk for death were used to model LOS, 30-day mortality, and 30-day readmission rate, respectively. All models were adjusted for HF severity, comorbidities, demographics, nursing home residence, and calendar year of admission. Beneficiaries with HFpEF had an LOS 0.02 days shorter than beneficiaries with HFrEF and a nearly identical 30-day readmission rate. Thirty-day mortality was 10% lower in beneficiaries with HFpEF versus HFrEF. In conclusion, readmission rates were as high in those with HFpEF as they are in those with HFrEF, with comparable LOS in the hospital.

Keywords: heart failure, ejection fraction, length of stay, readmission

Although patients with heart failure (HF) with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) make up half of HF hospitalizations,1 treatment is limited.2 In contrast, several therapeutic treatment strategies that reduce mortality and rehospitalizations exist for patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).2 Length of stay (LOS), 30-day mortality, and 30-day readmission are important outcomes for beneficiaries and can affect rates at which Medicare reimburses providers. Previous studies comparing outcomes between patients with HFrEF versus HFpEF have been restricted to patients admitted to hospitals participating in registries with no adjustment for potential confounders3,4 or patients participating in regional Healthcare Maintenance Organizations.5 Recent increases in the use of International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision codes that specify HF type allow the investigation of differences in LOS, 30-day mortality, and 30-day readmission rates between those with HFrEF and HFpEF among Medicare beneficiaries.

Methods

Our study sample consisted of Medicare beneficiaries in a 5% national random sample who: (1) had an inpatient claim for an overnight hospital stay with a primary discharge International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision code for HF between 2007 and 2011; (2) lived in the US for at least 1 year prior to index claim admission date; (3) had continuous fee-for-service coverage for inpatient, outpatient, and pharmacy services for at least 1 year prior to index claim admission date (Medicare parts A, B, and D coverage); (4) were < 110 years old on the index claim admission date; and (5) were discharged alive. Follow up data for this study was available through December 31, 2011. Heart failure type was determined to be either HFpEF (428.30 Diastolic heart failure, unspecified; 428.31 Diastolic heart failure, acute; 428.32 Diastolic heart failure, chronic; and 428.33 Diastolic heart failure, acute or chronic) or HFrEF (428.20 Systolic heart failure, unspecified; 428.21 Systolic heart failure, acute; 428.22 Systolic heart failure, chronic; 428.23 Systolic heart failure, acute or chronic; 428.40 Combined systolic and diastolic heart failure, unspecified; 428.41 Combined systolic and diastolic heart failure, acute; 428.42 Combined systolic and diastolic heart failure, chronic; and 428.23 Combined systolic and diastolic heart failure, acute or chronic). In a validation study of Medicare beneficiaries, 77% of beneficiaries with an International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision code for systolic heart failure (428.2x or 428.4x) had an EF < 45% based upon medical record review.6

Hospital admissions that occurred on the day of a hospital discharge, or the day after hospital discharge with a hospital transfer code, were considered as 1 episode of care. Only the first heart failure hospitalization for each beneficiary was used to determine study eligibility. This hospitalization was not necessarily the beneficiary’s first episode of HF treatment. Only hospitalizations that documented whether the HF was systolic, diastolic, or both (428.2x, 428.3x, and 428.4x) were included.

LOS was defined as the difference between the first day after discharge and admission date. Thirty-day mortality was determined by whether death by any cause occurred within 30 days of hospital discharge. Thirty-day hospital readmission was determined by whether hospitalization for any cause occurred within 30 days of hospital discharge.

Beneficiary characteristics were assessed using the beneficiary summary files, inpatient claims, and outpatient claims. Several potential confounders of the relationship between HF type (HFrEF versus HFpEF) and LOS, 30-day mortality, and 30-day readmission were included as covariates in the statistical models. An intensive care unit stay during hospitalization served as an indicator of disease severity. Therapies for HF included beta-blocker use, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor use, loop diuretics use, and treatment by implanted cardiac devices (cardiac resynchronization therapy – defibrillator, cardiac resynchronization therapy – pacemaker, defibrillator, pacemaker, or no device), determined by claims in the year prior to admission. Indicators of comorbidity burden based upon claims in the year prior to admission were hypertension, chronic kidney disease, stroke, coronary heart disease, malnutrition, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, anemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and the Charlson comorbidity Index (0, 1 – 3, or >=4). Age (years), race (black, white, or other), gender, and US Census region of residence (East North Central, East South Central, Middle Atlantic, Mountain, New England, Pacific, South Atlantic, West North Central, and West South Central) were included as demographic variables. Claims indicating nursing home residence during the year prior to admission were used as an indicator of frailty, as described previously.7 Calendar year of admission was also included in the models.

Summary statistics were calculated for potential confounders and for LOS (median[interquartile range]), 30-day mortality, and 30-day readmission for the total sample, as well as by HF type (HFrEF or HFpEF). We estimated the cumulative incidence functions for 30-day mortality and 30-day readmission by HF type. LOS was modeled using a gamma distribution with a log link function, following the precedence set by a prior study.8 We used Poisson regression with a log link function and robust standard errors to calculate risk ratios for 30-day mortality because the algorithm for performing binomial regression with a log link function did not converge. We used a Fine-Gray model to estimate the risk ratios of 30-day readmission, while accounting for the competing risk of death,9 which took into account that some beneficiaries died before we could observe their readmission. All model parameter estimates for HF type were adjusted for all potential confounders described above. Likelihood ratio tests or score tests were used to determine the statistical significance of variables with multiple categories, with a type 1 error rate of 0.05. Forest plots of the parameter estimates and 95% confidence intervals for all model variables were created for each of the LOS, 30-day mortality, and 30-day hospital readmission models. All statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC). Plot creation was performed in R v. 3.1.310 using the dyplyr11 and ggplot212 packages in the RStudio Integrated Development Environment (IDE).13

This study was determined not to be Human Subjects Research by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Privacy Board approved this study.

Results

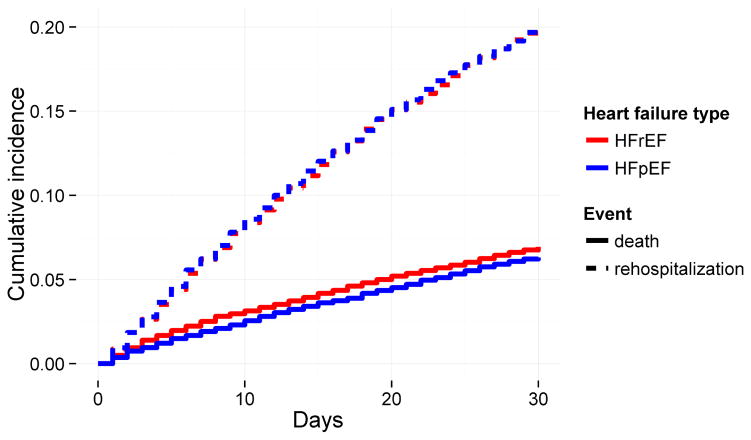

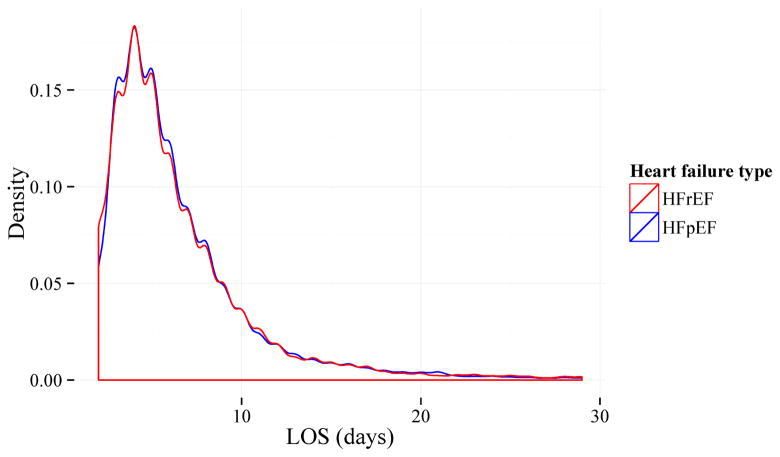

We initially identified 76,555 HF hospitalization episodes that met the inclusion criteria. After excluding HF rehospitalizations (30,971) and hospitalizations with an undocumented type of HF (26,107), we included a cohort of 19,477 beneficiaries for the current analysis (see Supplemental Figure 1). Table 1 provides summary statistics for LOS, 30-day mortality, 30-day readmission, and model covariates for the total cohort, as well as by HF type. Beneficiaries with a diagnosis of HFpEF were slightly older, more likely to be female, hypertensive, anemic, have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and be living in a nursing home than beneficiaries with a diagnosis of HFrEF. Beneficiaries with a diagnosis of HFpEF were less likely to have been taking a beta-blocker or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, less likely to have a defibrillator (with or without cardiac resynchronization), and were less likely to have had coronary heart disease than beneficiaries with a diagnosis of HFrEF. Based upon univariate comparisons, median LOS did not appear to be different between those with HFpEF and those with HFrEF. Crude 30-day mortality and readmission rates were similar between beneficiaries with HFpEF and beneficiaries with HFrEF. There were fewer hospitalizations in 2007 compared to later years because of the increasing trend in use of International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision codes that specified heart failure type since 2008. Figure 1 shows a histogram of LOS by HF type for those with LOS < 30 days, and Figure 2 shows the cumulative incidence functions for 30-day mortality and 30-day readmission by HF type.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure, by heart failure type.

| Variable* | Total sample (N = 19,477) | HFrEF (N = 10,256) | HFpEF (N = 9,221) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intensive care unit stay | 6,543 (34%) | 3,534 (35%) | 3,009 (33%) |

| Beta-blockers | 14,060 (72%) | 7,485 (73%) | 6,575 (71%) |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | 9,419 (48%) | 5,220 (51%) | 4,199 (46%) |

| Loop diuretics | 13,141 (68%) | 6,960 (68%) | 6,181 (67%) |

| Device | |||

| Cardiac resynchronization therapy - defibrillator | 1,096 (6%) | 1,024 (10%) | 72 (0.8%) |

| Cardiac resynchronization therapy - pacemaker | 64 (0.3%) | 53 (0.5%) | 11 (0.1%) |

| Defibrillator | 807 (4%) | 716 (7%) | 91 (1%) |

| Pacemaker | 2,015 (10%) | 994 (10%) | 1,021 (11%) |

| None | 15,495 (80%) | 7,469 (73%) | 8,026 (87%) |

| Hypertension | 16,232 (83%) | 8,204 (80%) | 8,028 (87%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 11,458 (59%) | 6,034 (59%) | 5,424 (59%) |

| Stroke | 1,055 (5%) | 547 (5%) | 508 (6%) |

| Coronary heart disease | 12,357 (63%) | 7,254 (71%) | 5,103 (55%) |

| Malnutrition | 1,616 (8%) | 812 (8%) | 804 (9%) |

| Diabetes | 9,478 (49%) | 4,931 (48%) | 4,547 (49%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 9,039 (46%) | 4,687 (46%) | 4,352 (47%) |

| Anemia | 11,353 (58%) | 5,678 (55%) | 5,675 (62%) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 9,717 (50%) | 4,947 (48%) | 4,770 (52%) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | |||

| 0 | 1,191 (6%) | 624 (6%) | 567 (6%) |

| 1–3 | 3,528 (18%) | 1,897 (19%) | 1,631 (18%) |

| >= 4 | 14,758 (76%) | 7,735 (75%) | 7,023 (76%) |

| Age (years)‡ | 78 (12) | 77 (12) | 79 (12) |

| Women | 12,177 (63%) | 5,433 (53%) | 6,744 (73%) |

| Men | 7,300 (38%) | 4,823 (47%) | 2,477 (27%) |

| Black | 2,779 (14%) | 1,501 (15%) | 1,278 (14%) |

| Other | 1,092 (6%) | 554 (5%) | 538 (6%) |

| White | 15,606 (80%) | 8,201 (80%) | 7,405 (80%) |

| US Census region | |||

| East North Central | 3,519 (18%) | 1,843 (18%) | 1,676 (18%) |

| East South Central | 1,806 (9%) | 1,028 (10%) | 778 (8%) |

| Middle Atlantic | 2,994 (15%) | 1,580 (15%) | 1,414 (15%) |

| Mountain | 674 (4%) | 386 (4%) | 288 (3%) |

| New England | 1,207 (6%) | 523 (5%) | 684 (7%) |

| Pacific | 1,651 (9%) | 886 (9%) | 765 (8%) |

| South Atlantic | 3,800 (20%) | 1,884 (18%) | 1,916 (21%) |

| West North Central | 1,476 (8%) | 795 (8%) | 681 (7%) |

| West South Central | 2,350 (12%) | 1,331 (13%) | 1,019 (11%) |

| Nursing home residence | 3,120 (16%) | 1,431 (14%) | 1,689 (18%) |

| Index year | |||

| 2007 | 1,678 (9%) | 754 (7%) | 924 (10%) |

| 2008 | 3,835 (20%) | 2,122 (21%) | 1,713 (19%) |

| 2009 | 4,432 (23%) | 2,367 (23%) | 2,065 (22%) |

| 2010 | 4,749 (24%) | 2,522 (25%) | 2,227 (24%) |

| 2011 | 4,783 (25%) | 2,491 (24%) | 2,292 (25%) |

| Length of stay (days)† | 5 (4 – 8) | 5 (4 – 8) | 5 (4 – 8) |

| 30-day mortality | 1,294 (7%) | 712 (7%) | 582 (6%) |

| 30-day readmission | 4,405 (23%) | 2,305 (23%) | 2,100 (23%) |

% used unless otherwise specified;

median(quartile 1 - quartile 3);

mean(sd); HFpEF (Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction); HFrEF (Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction); ICU (Intensive Care Unit)

Figure 1. Histogram of length of stay (LOS) for study sample by heart failure type.

Histogram shows extreme right-skewness of LOS, as well as the similar distribution of LOS between those with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) and those with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). For display purposes, sample was restricted to beneficiaries with LOS < 30 days.

Figure 2. Cumulative incidence functions for death and rehospitalization for any cause during the first 30 days after discharge from a heart failure hospitalization, separated by heart failure type.

Thirty-day mortality is slightly higher in those with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) compared to those with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Thirty-day readmission rates are similar between those with HFpEF and those with HFrEF.

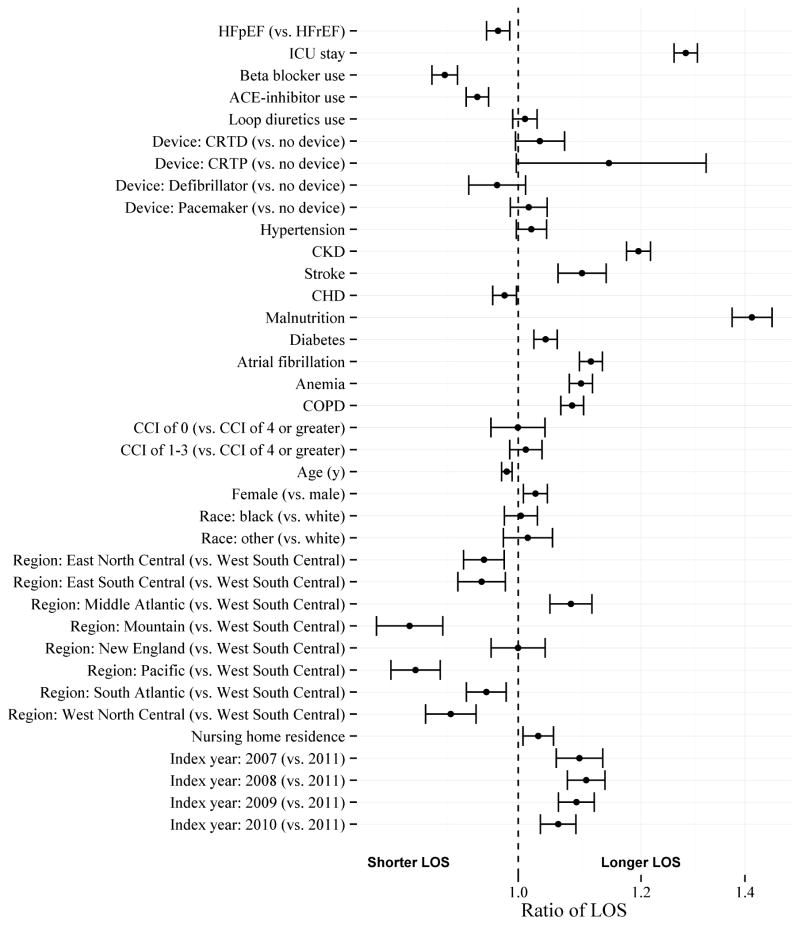

Figure 3 shows the ratio of LOS for those with HFpEF compared to those with HFrEF, as well as the ratios of LOS for each other covariate. Important covariates in the model for LOS were intensive care unit stay, malnutrition, and chronic kidney disease.

Figure 3. Ratios of LOS for heart failure type and covariates.

Parameter estimates include likelihood ratio 95% confidence intervals. Ratio of 1 indicates no association. CCI (Charlson Comorbidity Index); CHD (Coronary Heart Disease); CKD (Chronic Kidney Disease); COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease); CRTD (Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy – Defibrillator); CRTP (Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy – Pacemaker); HFpEF (Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction); HFrEF (Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction); ICU (Intensive Care Unit)

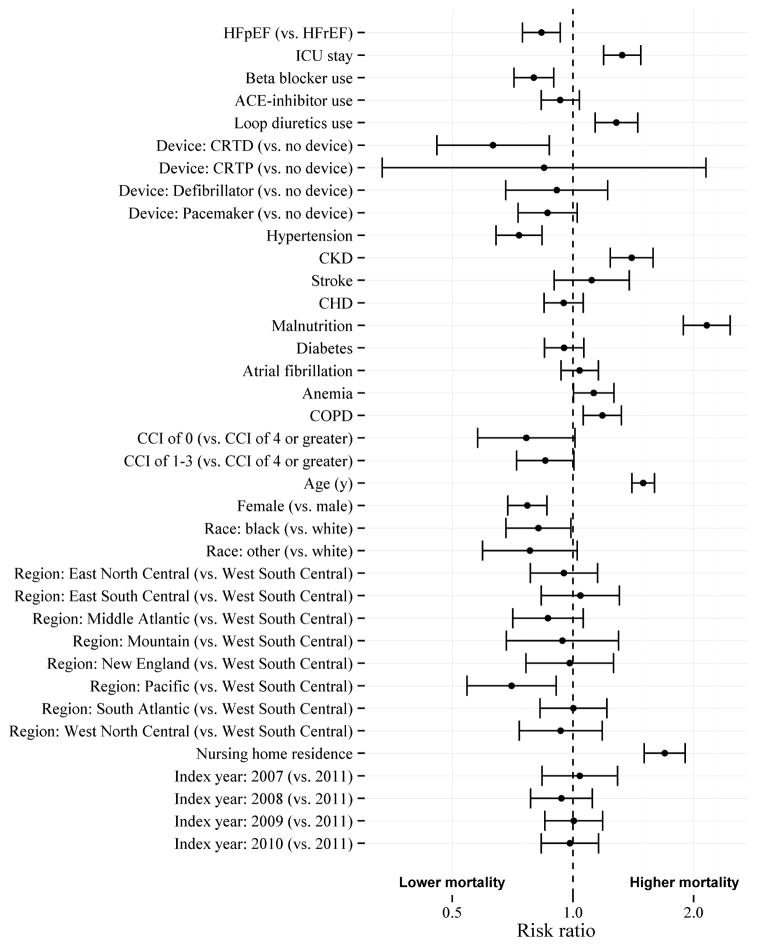

Figure 4 shows the risk ratios for 30-day mortality for those with HFpEF compared to those with HFrEF, as well as the risk ratios for 30-day mortality for each covariate. Important covariates for 30-day mortality were intensive care unit stay, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, malnutrition, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, age, and gender.

Figure 4. Risk ratios for 30-day all-cause mortality for heart failure type and covariates.

Parameter estimates include likelihood ratio 95% confidence intervals. Risk ratio of 1 indicates no association. CCI (Charlson Comorbidity Index); CHD (Coronary Heart Disease); CKD (Chronic Kidney Disease); COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease); CRTD (Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy – Defibrillator); CRTP (Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy – Pacemaker); HFpEF (Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction); HFrEF (Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction); ICU (Intensive Care Unit)

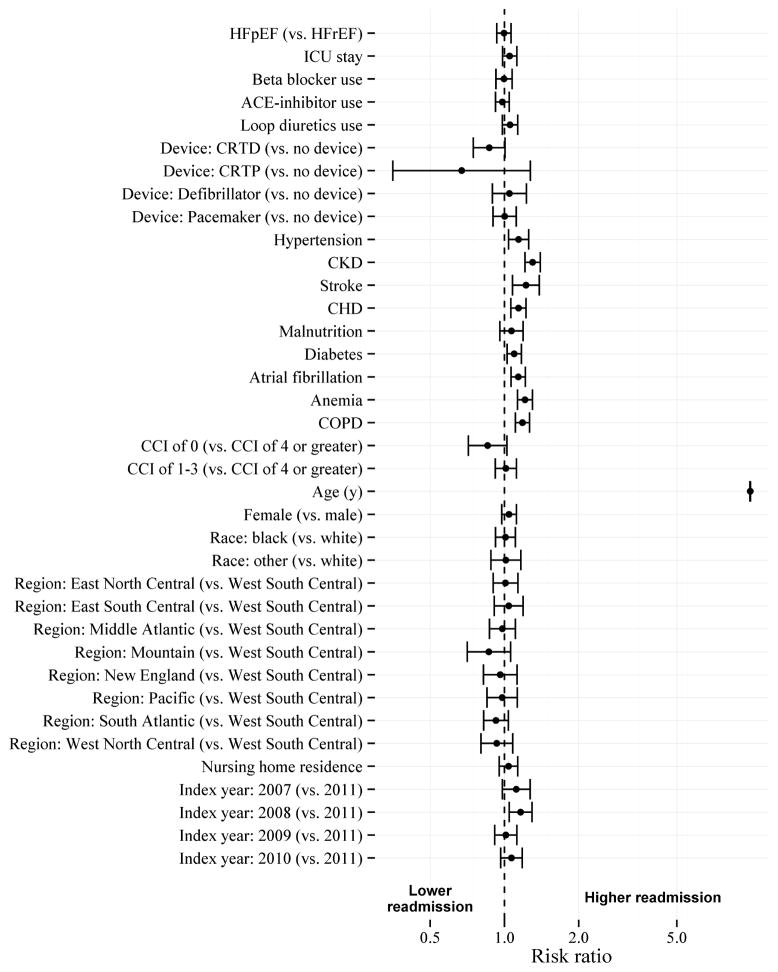

Figure 5 shows the risk ratios for 30-day readmission for those with HFpEF compared to those with HFrEF, as well as the risk ratios for each other covariate.

Figure 5. Risk ratios for 30-day hospital readmission for heart failure type and covariates.

Parameter estimates include likelihood ratio 95% confidence intervals. Risk ratio of 1 indicates no association. CCI (Charlson Comorbidity Index); CHD (Coronary Heart Disease); CKD (Chronic Kidney Disease); COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease); CRTD (Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy – Defibrillator); CRTP (Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy – Pacemaker); HFpEF (Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction); HFrEF (Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction); ICU (Intensive Care Unit)

Discussion

Given our lack of understanding of the association of HF type with LOS, 30-day mortality, and 30-day readmission rates in a general HF population, we investigated differences in these outcomes in a retrospective cohort of Medicare beneficiaries. After adjusting for HF severity, comorbidity burden, demographics, nursing home residence, and calendar year of admission, we found that LOS and 30-day readmission rates were similar between those with HFrEF and those with HFpEF. Thirty-day mortality was lower in those with HFpEF compared to those with HFrEF.

Previous studies of registry populations,3 single hospitals,14 and beneficiaries of regional healthcare maintenance organizations had findings consistent with our study of the Medicare population. Previous comparisons of outcomes in patients with HFrEF by payer type (i.e., commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid) revealed significant differences in in-patient care, LOS, and in-hospital survival depending upon the payer type.8 Thus, we hypothesized that studies of beneficiaries of a regional healthcare maintenance organizations5 might not generalize to the Medicare population. The vast majority of US adults at least 65 years old are covered by Medicare, and have fee-for-service coverage, creating a sample that is broad in terms of geography, demographics, and the types of healthcare systems in which the beneficiaries are seen. Despite similar findings, our study filled a gap in the literature by addressing the relationship between type of HF and LOS, 30-day mortality, and 30-day readmission rate in a general sample of patients with HF. The second most common cause of a hospitalization that Medicare paid for in 2013 was HF,15 partially due to the high rehospitalization rate among Medicare beneficiaries.16 Given that HFpEF makes up approximately half of HF hospitalizations,1 that outcomes are similar between patients with HFrEF versus HFpEF, and that therapies that improve outcomes exist for HFrEF but not for HFpEF, development of secondary-prevention therapies for HFpEF that reduce hospitalizations and mortality would have benefits at the patient and public health levels.

This study has a few limitations worth noting. We did not have direct measurements of ejection fraction because we did not have access to echocardiograms in Medicare claims. High prevalence of treatment by a beta blocker or an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor in those with HFpEF likely represents treatment for other conditions, such as hypertension, because we did not restrict these medications to those specifically indicated for HFrEF. Also, Medicare fee-for-service claims do not include measures of the actual health status of a beneficiary, so there could be misclassification bias in some of the model covariates. For example, from 1999 to 2006 the likelihood that at Medicare beneficiary with systolic dysfunction had a claim documenting systolic dysfunction was 12%.6 Although we were able to use the Charlson comorbidity index as a measure of overall comorbidity burden, we did not have reliable measures of severity for each comorbidity. Thus, we may not have captured the entire relationship between comorbidities and HF type, or between comorbidities and LOS, 30-day mortality, and 30-day readmission. These results apply to only those with documented HF type, which was only 43% of the first HF hospitalizations for participants in our cohort. This exclusion criterion particularly excluded hospitalizations before 2008, when the use of diagnosis codes that specified heart failure type began to increase. We also did not include beneficiaries with Medicare Advantage (20 – 25% of Medicare beneficiaries), since claims were not available for these beneficiaries. A core strength of this study was a large, generalizable sample with extensive information on healthcare utilization.

In conclusion, beneficiaries with HFpEF have similar utilization patterns to beneficiaries with HFrEF, based upon hospital LOS and 30-day readmission rates. Given that hospital readmission rates are as high in those with HFpEF as those with HFrEF, new therapeutic strategies should be investigated to reduce hospitalizations in patients with HFpEF.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: NHLBI 5T32HL00745734 and Amgen Inc. (Thousand Oaks, CA)

Funding Sources

This work was funded by NHLBI 5T32HL00745734 and Amgen Inc. Amgen Inc. provided comments on the design and interpretation of this work. The academic authors conducted all analyses and maintained the rights to publish this manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosures

MSL receives salary support from Amgen Inc. MKVD works in the Center for Observational Research, Amgen Inc. LC, TMB, RWD, and EBL have received research grants from Amgen Inc.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:251–259. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:e147–e239. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sweitzer NK, Lopatin M, Yancy CW, Mills RM, Stevenson LW. Comparison of clinical features and outcomes of patients hospitalized with heart failure and normal ejection fraction (> or =55%) versus those with mildly reduced (40% to 55%) and moderately to severely reduced (<40%) fractions. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:1151–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whellan DJ, Zhao X, Hernandez AF, Liang L, Peterson ED, Bhatt DL, Heidenreich PA, Schwamm LH, Fonarow GC. Predictors of hospital length of stay in heart failure: findings from Get With the Guidelines. J Card Fail. 2011;17:649–656. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nichols GA, Reynolds K, Kimes TM, Rosales AG, Chan WW. Comparison of Risk of Rehospitalization, All-Cause Mortality, and Medical Care Resource Utilization in Patients With Heart Failure and Preserved Versus Reduced Ejection Fraction. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:1088–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Q, Glynn RJ, Dreyer NA, Liu J, Mogun H, Setoguchi S. Validity of claims-based definitions of left ventricular systolic dysfunction in Medicare patients. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:700–708. doi: 10.1002/pds.2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yun H, Kilgore ML, Curtis JR, Delzell E, Gary LC, Saag KG, Morrisey MA, Becker D, Matthews R, Smith W, Locher JL. Identifying types of nursing facility stays using medicare claims data: an algorithm and validation. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol. 2010;10:100–110. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen LA, Smoyer Tomic KE, Wilson KL, Smith DM, Agodoa I. The inpatient experience and predictors of length of stay for patients hospitalized with systolic heart failure: comparison by commercial, Medicaid, and Medicare payer type. J Med Econ. 2013;16:43–54. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2012.726932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 10.R Core Team. R: A language environment for statistical computing. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wickham H, Francois R. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. 2015 Available at: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr.

- 12.Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.RStudio. Rstudio: Integrated development environment for R. 2014 Available at: https://www.rstudio.com/products/rstudio/

- 14.Malki Q, Sharma ND, Afzal A, Ananthsubramaniam K, Abbas A, Jacobson G, Jafri S. Clinical presentation, hospital length of stay, and readmission rate in patients with heart failure with preserved and decreased left ventricular systolic function. Clin Cardiol. 2002;25:149–152. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960250404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agency For Healthcare Research. HCUP Fast Stats. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP); Available at: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/faststats/national/inpatientcommondiagnoses.jsp. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.