Abstract

Background

A psoriasis-like eruption develops in a subset of patients with Kawasaki disease (KD).

Objective

To systematically compare KD-associated psoriasiform eruptions with classic psoriasis and the outcomes of KD in children with and without this rash.

Methods

This was a retrospective study of 11 KD cases with a psoriasiform eruption matched 1:2 by age, gender, and ethnicity with psoriasis-only and KD-only controls. Genotyping was performed in 10 cases for a deletion of two late cornified envelope (LCE) genes, LCE3C_LCE3B-del, associated with increased risk for pediatric-onset psoriasis.

Results

Similar to classic psoriasis, KD-associated eruptions were characterized clinically by well-demarcated, scaly pink plaques and histopathologically by intraepidermal neutrophils, suprabasilar keratin 16 expression, and increased Ki-67 expression. They showed less frequent diaper area involvement, more crust and serous exudate, and an enduring remission (91% vs. 23% with confirmed resolution; p < 0.001). Frequency of LCE3C_LCE3B-del and major KD outcomes were similar between cases and controls.

Limitations

The study was limited by the small number of cases, treatment variation, and availability of skin biopsy specimens.

Conclusions

Although the overall clinical and histopathologic findings were similar to conventional psoriasis, this appears to be a distinct phenotype with significantly greater propensity for remission. No adverse effect on KD outcomes was noted.

Keywords: psoriasis, psoriasiform, Kawasaki disease, keratin 16, Ki-67, LCE3C_LCE3B deletion

Introduction

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute systemic inflammatory illness causing vasculitis and potentially fatal coronary artery aneurysms in 15–25% of untreated children.1 Approximately 90% of patients present with a diffuse polymorphous rash that can have a morbilliform, urticarial, micropustular, or other morphology. A psoriasis-like eruption develops in a small subset of patients during the acute, subacute, or convalescent phases of the disease.2–4 One series suggested a higher prevalence of psoriasiform eruptions among children with KD compared to the general pediatric population (1.9% of 476 children with KD vs. general prevalence estimates of 0.19% to 1.4%).2,5–7 The eruption can have an atypical presentation and does not appear to persist,2,8 creating uncertainty over whether it represents true psoriasis.

We conducted a retrospective, case-control study to systematically compare KD-associated psoriasiform eruptions with classic psoriasis. We performed genotyping for a deletion associated with pediatric-onset psoriasis and compared the course of KD accompanied by this eruption to KD without this rash.

Materials and Methods

The study was approved by the University of California, San Diego and Rady Children’s Hospital (RCHSD) Institutional Review Boards. Patients who developed a psoriasiform eruption during KD illness were identified by searching all RCHSD records from January 1, 1998 through August 1, 2012, using ICD-9 diagnostic codes [selecting those diagnosed with KD (446.1) and psoriasis (696.1) or rash (782.1)]. KD illness was confirmed by chart review using the American Heart Association criteria.1 Occurrence of a psoriasiform eruption was confirmed by photographic documentation, histopathologic documentation, and/or diagnosis by an experienced pediatric dermatologist.

KD subjects with a psoriasiform eruption were matched 1:2 with classic psoriasis patients of similar age, sex, and ethnicity from the same time period, identified by record search using the ICD-9 code for psoriasis (696.1) and confirmed by chart review to never have had KD. Cases were also matched 1:2 with KD patients without a psoriasiform eruption. For adequate assessment of skin disease course, inclusion criteria for psoriasis controls required at least 3 months of dermatology follow-up or documented eruption remission prior to 3 months. Records were reviewed for patient, family, and disease history. Severity of coronary artery dilatation (using the coronary artery Z score = internal diameter normalized for body surface area and expressed as standard deviation units from the mean), peak levels of inflammatory markers, and length of time until their normalization were determined.

Archived skin biopsy specimens were available for 4 of 11 confirmed cases of KD-associated psoriasiform eruption. The histopathologic findings were compared with control specimens consistent with plaque psoriasis (6 specimens), guttate psoriasis (5), and psoriasiform dermatitis (5). A dermatopathologist (A.C.), blinded to patient history and diagnosis, examined and scored the findings. Additionally, tissue samples from the 4 cases were stained for Keratin 16 and Ki-67 antigen as markers of keratinocyte hyperproliferation and compared with findings in conventional psoriasis lesions.9–11

Ten of the 11 cases had archived DNA and genotyping was performed for a deletion of two late cornified envelope (LCE) genes, LCE3C_LCE3B-del, associated with an increased risk for psoriasis, particularly pediatric-onset disease.12 It was of interest as potentially contributing to the development of psoriasiform lesions during KD. This deletion is thought to lead to inappropriate epidermal barrier repair in response to skin injury, which may then promote inflammation.13 Presence of this deletion in the 10 cases and in 146 subjects solely with KD was determined using the tagging single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs4112788.13 DNA was extracted from blood and mouthwash samples as previously described.14 Genotyping of rs4112788 was performed using a Taqman assay following the manufacturer’s instructions (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA; Assay ID C_31910050_10). LCE3C_LCE3B-del was confirmed in the 10 cases using conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods with primers located outside and inside of the deletion (see Supplemental Methods).

Statistical analyses of patient characteristics were performed using the t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test (2×2 comparisons) and the Pearson chi-square test (>2×2 comparisons) for categorical variables. Kaplan-Meier analysis with log-rank testing was used to compare duration of eruptions and inflammatory marker elevation, while Wilcoxon signed-rank tests assessed for differences in Z scores and inflammatory marker levels. Two-sided p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 22 (Armonk, NY).

Results

Eleven of 870 children diagnosed with KD during the 14-year study period developed a psoriasiform eruption (1.3%). The median illness day (day 1 = first day of fever) of eruption onset was day 22. Two children developed psoriasiform lesions during the acute phase of KD (illness day 1–1015), 3 during the subacute phase (illness day 11–21), and 6 during the convalescent phase (illness day 22 or later). Demographic data is shown in Table I. All cases had body mass index (BMI) percentiles in the normal range, while 53% of control psoriasis patients were overweight or obese (p = 0.004).

Table I.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study subjects in the three cohorts.

| KD + psoriasis (n = 11) | KD only (n = 22) | Psoriasis only (n = 22) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 6 (55%) | 6 (55%) | 6 (55%) | Matched |

| Median age [range] at diagnosis of KD or psoriasis, in years | 1.9 [0.3–15.2] | 2.0 [0.2–14.9] | 1.5 [0.08–15.5] | 1 |

| Positive family history of psoriasis, %1 | 22% | 17% | 47% | 0.18 |

| Ethnicity/Race, n (%) | 0.19 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 4 (36%) | 8 (36%) | 10 (45%) | |

| Hispanic White | 6 (55%) | 6 (27%) | 10 (45%) | |

| Asian | 1 (9%) | 5 (23%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Black | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| >1 Race/Other | 0 (0%) | 3 (14%) | 2 (9%) | |

| KD course | ||||

| Illness day2 of KD diagnosis, median [range] | 8 [4–54] | 6 [2–36] | 0.58 | |

| Maximum coronary artery Z score,3 median [range] | 2.7 [0.8–16] | 1.8 [0.6–7] | 0.16 | |

| Number of days to normalization of Z score, median [range] | 11 [4–1502] | 12 [4–2021] | 0.82 | |

| Time of KD treatment, n (%) | 0.12 | |||

| Untreated patients | 2 (18%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Patients treated within 10 illness days | 8 (73%) | 19 (86%) | ||

| Patients treated after illness day 10 | 1 (9%) | 3 (14%) | ||

| KD treatment received, n (%) | 0.08 | |||

| No treatment | 2 (18%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| IVIG and aspirin only | 6 (55%) | 18 (82%) | ||

| IVIG, aspirin, and infliximab | 3 (27%) | 4 (36%) | ||

| Indication for infliximab, n (%) | 0.91 | |||

| Coronary artery dilation | 1 (9%) | 1 (5%) | ||

| IVIG resistance | 1 (9%) | 2 (9%) | ||

| Clinical trial participant randomized to receive infliximab | 1 (9%) | 1 (5%) | ||

KD, Kawasaki disease; IVIG, intravenous immune globulin

Family history was available for 9 cases, 12 KD controls, and 17 psoriasis controls. Percentages reflect the percent of known family histories that were positive for psoriasis (2/9 cases, 2/12 KD controls, 8/17 psoriasis controls).

Illness day 1 defined as first day of fever.

Z score defined as the internal diameter of the coronary artery normalized for body surface area and expressed as standard deviation units from the mean.

Clinical Features

The eruption in 9 KD-associated cases resembled plaque psoriasis, one resembled guttate psoriasis and one had only psoriatic nail pitting and a family history of psoriasis. Of the 22 psoriasis controls, 13 had plaque psoriasis, 5 had guttate disease, and the remainder had isolated inverse or diaper involvement. In both groups, psoriasiform lesions were most commonly located on the diaper area, trunk, extensor extremities, and face (Table II), but diaper lesions were less prevalent amongst KD cases (55% vs. 91% of controls, p = 0.03). KD-associated lesions tended to be well-demarcated, scaly pink plaques, but several subjects had more crusting than is seen in typical psoriasis, and two had fine scaling as opposed to the classic micaceous scale (Figs 1 and 2).

Table II.

Characteristics of Kawasaki disease-associated psoriasiform eruptions compared to conventional psoriasis

| KD + psoriasis (n = 11) | Psoriasis only (n = 22) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psoriasis type, n (%) | 0.15 | ||

| Plaque | 9 (82%) | 13 (59%) | |

| Guttate | 1 (9%) | 5 (23%) | |

| Inverse or diaper area only | 0 (%) | 4 (18%) | |

| Nails only | 1 (9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Sites of involvement, n (%) | |||

| Scalp | 2 (18%) | 9 (41%) | 0.26 |

| Face | 5 (45%) | 15 (68%) | 0.27 |

| Trunk | 6 (55%) | 17 (77%) | 0.24 |

| Extremities, extensor | 6 (55%) | 15 (68%) | 0.47 |

| Extremities, flexor | 3 (27%) | 3 (14%) | 0.38 |

| Axilla and inguinal folds | 2 (18%) | 5 (23%) | 1 |

| Digits | 1 (9%) | 4 (18%) | 0.64 |

| Palms and soles | 0 (0%) | 3 (14%) | 0.54 |

| Diaper | 6 (55%) | 20 (91%) | 0.03 |

| Nails | 2 (18%) | 4 (18%) | 1 |

| Neck | 2 (18%) | 7 (32%) | 0.68 |

| Psoriasis treatment received, n (%) | 0.02 | ||

| No treatment | 3 (27%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Topical corticosteroid only | 3 (27%) | 3 (14%) | |

| Topical calcineurin inhibitor only | 0 (0%) | 1 (5%) | |

| More than one topical agent (corticosteroid, vitamin D analog, calcineurin inhibitor, salicylic acid, coal tar) | 4 (36%) | 18 (82%) | |

| Systemic therapy | 1 (9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Eruption course and remission | |||

| Number with eventual remission, n (%) | 10 (91%) [last case nearly resolved when lost to follow-up] | 5 (23%) | <0.001 |

| Duration of follow-up, in months – median [range] | 46.0 [1.1–160.5] | 26.1 [2.0–71.4] | 0.20 |

| Duration of eruption in those with remission, in months – median [range] | 8.8 [1.6–17.9] | 6.0 [2.0–11.5] | 0.42 |

| Remission duration to date, in months – median [range] | 43.9 [0–146.6] | 8.1 [0–66.3] | 0.25 |

Figure 1.

Psoriasiform eruption in a 5 month-old Hispanic female with KD diagnosed and treated with IVIG and aspirin on illness day 13. Patient received infliximab on day 15 for severe coronary artery dilation. This eruption developed on day 22, consisting of (A) well-demarcated pink-red plaques, with (B) extensive crusting. The skin disease was treated with subcutaneous etanercept for 6 months until resolution, with no recurrence in almost 4 years.

Figure 2.

Psoriasiform eruption in a 3 year-old non-Hispanic White female with KD diagnosed and treated with IVIG and aspirin on illness day 5, followed by infliximab on day 7 due to IVIG nonresponse. Pink plaques with fine white scale (A and B) appeared 2 months later. The eruption was treated with low potency topical steroids, and gradually resolved over 12 months.

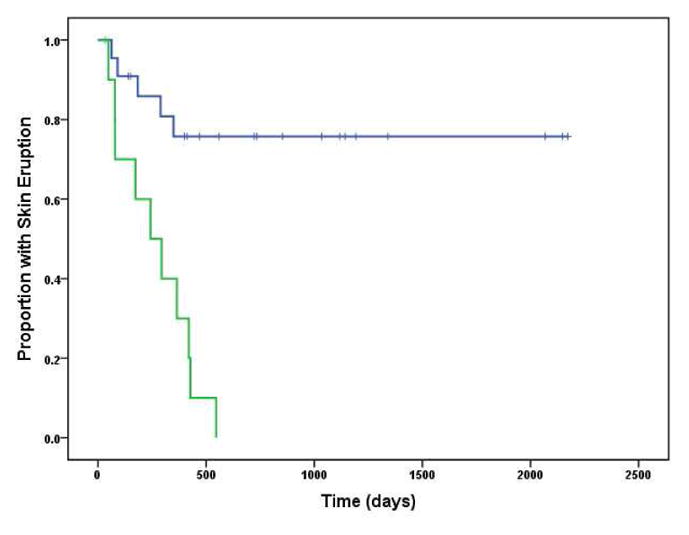

At least 91% of KD-associated psoriasiform eruptions resolved, while only 23% of classic psoriasis patients experienced remission (p < 0.001, Fig 3). The only case without confirmed remission was near resolution when last seen, but was subsequently lost to follow-up. No known recurrence of lesions occurred among the KD cases (median duration of remission of 44 months, with one remission lasting over 12 years). Most were treated with topical corticosteroids +/− other topical therapies or did not require treatment. One case with severe diffuse disease (Fig 1) received weekly subcutaneous etanercept for six months until resolution. Of the 5 control subjects who achieved remission, 3 had plaque psoriasis and 2 had guttate psoriasis. All received only topical therapies.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier plots of eruption duration. The green line represents thegroup with psoriasiform eruptions during Kawasaki disease. The blue line represents the group of matched controls with conventional psoriasis (not associated with KD).

Histopathology and immunostaining

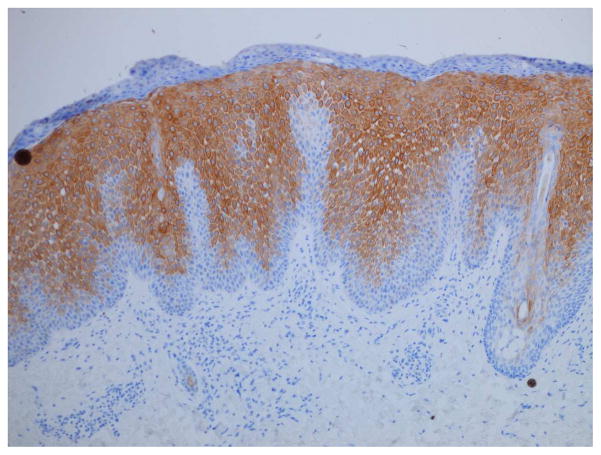

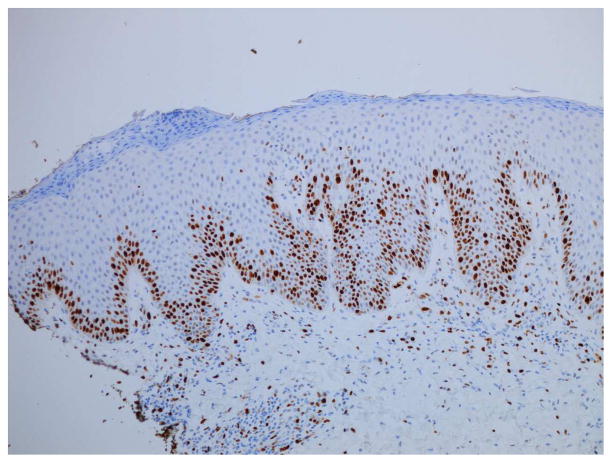

Serous crusting and bacteria in the cornified layer were seen more frequently in KD-associated psoriasiform lesions than in typical psoriasis lesions (Table III). Although not statistically significant, neutrophils were noted more frequently in the subcorneal epidermis of patients with KD, but they were not well formed into spongiform pustules. Eosinophils were generally absent from the dermal infiltrate, as compared to other types of psoriasiform dermatitis. Immunostaining demonstrated significant suprabasilar expression of keratin 16 and increased Ki-67 expression in the lower epidermis in biopsy specimens from KD patients (Fig 4), confirming epidermal hyperproliferation.

Table III.

Comparison of histologic findings of skin biopsies from Kawasaki disease-associated psoriasiform eruptions versus those of typical plaque or guttate psoriasis and other psoriasiform dermatitides (such as chronic spongiotic dermatitides with a psoriasiform pattern or psoriasiform drug eruptions)

| KD + psoriasis (n = 4) | Typical plaque and guttate psoriasis (n = 11) | P-value* | Psoriasiform dermatitis (n = 5) | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serous exudate or crusting | 4 (100%) | 1 (9%) | 0.004 | 1 (20%) | 0.05 |

| Bacteria in the cornified layer | 2 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 0.06 | 1 (20%) | 0.52 |

| Hyperkeratosis | 4 (100%) | 8 (73%) | 0.52 | 5 (100%) | -- |

| Parakeratosis | 4 (100%) | 11 (100%) | --- | 5 (100%) | -- |

| Neutrophils in cornified layer | 3 (75%) | 7 (64%) | 1 | 5 (100%) | 0.44 |

| Munro microabscesses | 2 (50%) | 6 (55%) | 1 | 1 (20%) | 0.52 |

| Regular epidermal hyperplasia | 2 (50%) | 7 (64%) | 1 | 1 (20%) | 0.52 |

| Irregular epidermal hyperplasia | 2 (50%) | 4 (36%) | 1 | 4 (80%) | 0.52 |

| Elongated rete ridges | 4 (100%) | 7 (64%) | 0.52 | 4 (80%) | 1 |

| Thinning suprapapillary plates | 4 (100%) | 6 (55%) | 0.23 | 3 (60%) | 0.44 |

| Diminished granular cell layer | 4 (100%) | 11 (100%) | --- | 5 (100%) | -- |

| Neutrophils in epidermis | 3 (75%) | 3 (27%) | 0.24 | 0 (0%) | 0.05 |

| Kogoj micropustules | 0 (0%) | 3 (27%) | 0.52 | 0 (0%) | -- |

| Increased proliferation index | 4 (100%) | 8 (73%) | 0.52 | 5 (100%) | -- |

| Epidermal spongiosis | 4 (100%) | 10 (91%) | 1 | 4 (80%) | 1 |

| Dilated blood vessels in dermis | 3 (75%) | 9 (82%) | 1 | 4 (80%) | 1 |

| Tortuous capillaries | 3 (75%) | 8 (73%) | 1 | 3 (60%) | 1 |

| Vasculitis | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | --- | 0 (0%) | -- |

| Lymphocytic infiltrate | 4 (100%) | 11 (100%) | --- | 5 (100%) | -- |

| Eosinophilic infiltrate | 1 (25%) | 2 (18%) | 1 | 3 (60%) | 0.52 |

| Dermal edema | 0 (0%) | 4 (36%) | 0.52 | 0 (0%) | -- |

| Vertically oriented collagen bundles | 2 (50%) | 1 (9%) | 0.15 | 3 (60%) | 1 |

| Apoptotic keratinocytes | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | --- | 2 (40%) | 0.44 |

P-values are in comparison to KD-associated psoriasiform (KD + psoriasis) eruptions

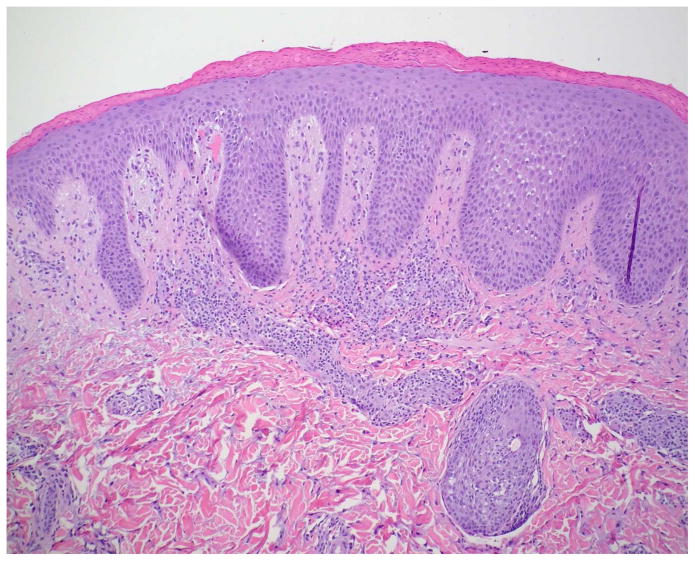

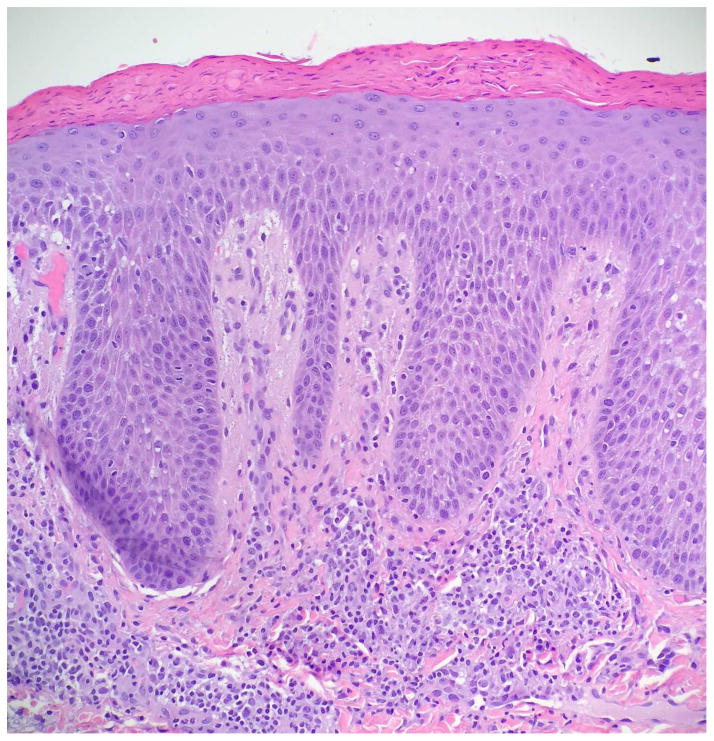

Figure 4.

Histopathologic examination of a KD-associated psoriasiform lesion, demonstrating (A) psoriasiform hyperplasia and focal thinning of the suprapapillary plates (H&E, 40x), with (B) mounds of parakeratosis, neutrophils, and serum in the cornified layer (H&E, 200x). Immunohistochemistry showed (C) suprabasilar keratin 16 staining (100x) and (D) increased Ki-67 antigen expression in the lower epidermis (40x). Non-psoriatic skin typically has keratin 16 staining only in the basal cells and the tips of rete ridges, while Ki-67 expression is scant and at most present at the basal layer.9–11,21

Genotyping for LCE3C_LCE3B-del

PCR assay using primers located within and flanking the deletion was consistent with results obtained from the tagging SNP. Frequency of the deletion was not statistically different between KD subjects with and without psoriasiform eruptions (Table IV).

Table IV.

Presence of the LCE3B and 3C deletion (LCE3C_LCE3B-del) on Chromosome 1.

| KD + psoriasis (n = 10) | KD only (n = 146) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype, n (%) | 0.54 | ||

| deletion/deletion | 5 (50%) | 51 (35%) | |

| deletion/wild type | 4 (40%) | 63 (43%) | |

| wild type/wild type | 1 (10%) | 32 (22%) | |

| Frequency of minor allele (wild type) | 0.30 | 0.43 | 0.35 |

Kawasaki disease course

There was no difference in the maximum Z scores, time required for Z scores to normalize, or peak levels of inflammatory markers (white blood cell count, neutrophil count, platelet count, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate; data not shown) for cases and controls. However, longer time was required for platelets and neutrophils to normalize in patients who had a psoriasiform eruption [median 44 vs. 31 days (p = 0.04) and 22 vs. 10 days (p = 0.02), respectively]. In all but one case, inflammatory markers had normalized by the time of psoriasis remission. There was variation in KD treatments, but the small sample size precluded controlling for these differences. In addition to standard intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and aspirin therapy, some patients received infliximab, a tumor-necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitor, either for severe coronary artery dilatation, inadequate IVIG response, or randomization to the treatment arm of a clinical trial studying its addition to standard therapy.

Discussion

Our study confirms that KD-associated psoriasiform eruptions differ from classic psoriasis. There was less diaper area involvement than is commonly seen in young children and more serous crust in some cases. A. Studies have shown obesity to be co-morbid with psoriasis and a possible risk factor for disease via overproduction of inflammatory mediators.16,17 Our patients were not obese and this mechanism does not appear to be significant in the KD setting. Family history of psoriasis as a risk factor for developing psoriatic lesions18 was documented in only 22% of KD-associated cases; this was not significantly different from our control groups. Psoriasiform eruptions during KD resolved within 18 months and did not recur over a median follow-up period of 3.8 years. This is similar to 18 cases in the published literature, only one of which persisted beyond one year before resolution.19 Such enduring remission contrasts with typical psoriasis. In one study, 35.3% of 223 pediatric-onset psoriasis patients experienced quiescence, but the median longest duration without active lesions was only 9 months.18

Consistent with a recent report of a psoriasiform eruption following treatment of KD with IVIG and infliximab,8 we found histopathologic similarities and differences between KD-associated psoriasiform eruptions and typical psoriasis. Whereas that report noted an absence of neutrophils transmigrating through the epidermis, histopathologic examination of KD-associated skin lesions in our study demonstrated neutrophils in the epidermis or cornified layer. We identified bacteria in some KD-associated lesions but not with typical psoriasis, in which overproduction of antimicrobial peptides and decreased tendency for skin infection are characteristic.20 Nevertheless, the overall findings and immunostaining pattern mirrored that of conventional psoriasis.9–11,21

Psoriasiform eruptions do not appear to be a manifestation of KD vasculitis, as no skin biopsy specimens have shown small or medium vessel vasculitis. Genotyping for LCE3C_LCE3B-del revealed a minor allele frequency (MAF) in the subjects with KD and psoriasiform eruptions similar to that reported by Bergboer et al.12 for pediatric-onset psoriasis (MAF = 0.3 vs. 0.27, both by direct PCR). The 146 children solely with KD had a MAF similar to the non-psoriatic controls in that study (MAF = 0.43 vs. 0.4, by tagging SNP and direct PCR methodology, respectively). Our study lacked sufficient power for robust statistical analysis, and a larger study is warranted to test for increased heritable risk for psoriasis among KD patients who develop this eruption. Overlap in the inflammatory cytokines induced in KD and psoriasis4,16 may explain the development of psoriasis in some KD patients, but without chronic skin disease because KD is self-limited.

A contributory role for infliximab in some cases was considered. Infliximab is known to provoke psoriasis-like rashes in patients with inflammatory bowel disease or rheumatoid arthritis.22 There was no evidence of a psoriasiform drug reaction with eosinophils in biopsy specimens from two children who had received infliximab, but non-eosinophilic psoriasiform drug reactions can occur. One of these children had resolution of her skin lesions after treatment with etanercept, another TNF inhibitor. Therefore, the extent to which these drugs cause or treat psoriasiform eruptions in KD is unclear, and patient counseling should include the possibility of developing such an eruption. Even with TNF inhibitor use, psoriasiform eruptions in KD generally resolve and do not recur, which is important given the growing role of infliximab in KD management.23

In our study, presence of a psoriasiform eruption did not impact major KD outcomes. Further investigation is needed to clarify the role of these skin eruptions relative to factors such as time to KD diagnosis, response to initial IVIG treatment, and treatment with infliximab.

Study limitations include the small sample size, which may not have allowed detection of true differences between groups for some parameters. All the caveats of a retrospective study apply, including variation in treatment and paucity of skin biopsy specimens.

Conclusion

KD-associated psoriasiform eruptions appear to be a distinct phenotype, with a propensity for remission. Further study of this unique overlap between psoriasis and KD may provide additional insight into the pathophysiology of these complex, immune-mediated disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: W. Tom is supported by a Career Development Award (K23AR060274) from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health. E. Haddock was supported by the National Institutes of Health, Grant T35HL007491.

The authors wish to thank James Proudfoot, MSc for statistical review and Viraj Deshpande, PhD for provision of primers for LCE3C_LCE3B deletion analysis.

Abbreviations

- KD

Kawasaki disease

- IVIG

intravenous immune globulin

Footnotes

Study approved by the University of California, San Diego and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego Institutional Review Boards (#121188, 8/23/12)

Portions of this work were presented at the Society for Pediatric Dermatology Annual Meeting in Coeur d’Alene, ID, July 10–12, 2014.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Gerber MA, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a statement for health professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association. Circulation. 2004;110:2747–2771. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145143.19711.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eberhard BA, Sundel RP, Newburger JW, et al. Psoriatic eruption in Kawasaki disease. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2000;137:578–580. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.107840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zvulunov A, Greenberg D, Cagnano E, et al. Development of psoriatic lesions during acute and convalescent phases of Kawasaki disease. J Paediatr Child Health. 2003;39:229–231. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2003.00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayers S, Shulman ST, Paller AS. Kawasaki disease. Journal of American Dermatology. 2013;69:501.e1–501.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Augustin M, Glaeske G, Radtke MA, et al. Epidemiology and comorbidity of psoriasis in children. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:633–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gelfand JM, Weinstein R, Porter SB, et al. Prevalence and Treatment of Psoriasis in the United Kingdom. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1–5. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.12.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu JJ, Black MH, Smith N, et al. Low prevalence of psoriasis among children and adolescents in a large multiethnic cohort in southern California. Journal of American Dermatology. 2011;65:957–964. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kishimoto S, Muneuchi J, Takahashi Y, et al. Psoriasiform skin lesion and supprative acrodermatitis associated with Kawasaki disease followed by the treatment with infliximab: a case report. Acta Paediatrica. 2010;99:1102–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ando M, Kawashima T, Kobayashi H, et al. Immunohistological detection of proliferating cells in normal and psoriatic epidermis using Ki-67 monoclonal antibody. J Dermatol Sci. 1990;1:441–446. doi: 10.1016/0923-1811(90)90014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thewes M, Stadler R, Korge B, et al. Normal psoriatic epidermis expression of hyperproliferation-associated keratins. Arch Dermatol Res. 1991;283:465–471. doi: 10.1007/BF00371784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leigh IM, Navsaria H, Purkis PE, et al. Keratins (K16 and K17) as markers of keratinocyte hyperproliferation in psoriasis in vivo and in vitro. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:501–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb02696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bergboer JGM, Oostveen AM, de Jager MEA, et al. Paediatric-onset psoriasis is associated with ERAP1and IL23Rloci, LCE3C_LCE3Bdeletion and HLA-C*06. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:922–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Cid R, Riveira-Munoz E, Zeeuwen PLJM, et al. Deletion of the late cornified envelope LCE3B and LCE3C genes as a susceptibility factor for psoriasis. Nat Genet. 2009;41:211–215. doi: 10.1038/ng.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burgner D, Davila S, Breunis WB, et al. A Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Novel and Functionally Related Susceptibility Loci for Kawasaki Disease. In: Gibson G, editor. PLoS Genet. Vol. 5. 2009. pp. e1000319–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tremoulet AH, Jain S, Chandrasekar D, et al. Evolution of Laboratory Values in Patients With Kawasaki Disease. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2011;30:1022–1026. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31822d4f56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carrascosa JM, Rocamora V, Fernandez-Torres RM, et al. Obesity and psoriasis: inflammatory nature of obesity, relationship between psoriasis and obesity, and therapeutic implications. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas. 2014;105:31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Setty AR, Curhan G, Choi HK. Obesity, waist circumference, weight change, and the risk of psoriasis in women: Nurses’ Health Study II. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1670–1675. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raychaudhuri SP, Gross J. A comparative study of pediatric onset psoriasis with adult onset psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:174–178. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2000.01746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garty B, Mosseri R, Finkelstein Y. Guttate psoriasis following Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:507–508. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2001.1862002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morizane S, Gallo RL. Antimicrobial peptides in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. The Journal of Dermatology. 2012;39:225–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01483.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amin MM, Azim ZA. Immunohistochemical study of osteopontin, Ki-67, and CD34 of psoriasis in Mansoura, Egypt. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2012;55:56–60. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.94857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wollina U, Hansel G, Koch A, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitor-induced psoriasis or psoriasiform exanthemata: first 120 cases from the literature including a series of six new patients. AM J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:1–14. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200809010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tremoulet AH, Jain S, Jaggi P, et al. Infliximab for intensification of primary therapy for Kawasaki disease: a phase 3 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1731–1738. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62298-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.