Abstract

Objective

Information technology supporting patient self-management has the potential to foster shared accountability for healthcare outcomes by improving patient adherence. There is growing interest in providing alerts and reminders to patients to improve healthcare self-management. This paper describes a literature review of automated alerts and reminders directed to patients, the technology used, and their efficacy.

Methods

An electronic literature search was conducted in PubMed to identify relevant studies. The search produced 2418 abstracts; 175 articles underwent full-text review, of which 124 were rejected. 51 publications were included in the final analysis and coding.

Results

The articles are partitioned into alerts and reminders. A summary of the analysis for the 51 included articles is provided.

Conclusion

Reminders and alerts are advantageous in many ways; they can be used to reach patients outside of regular clinic settings, be personalized, and there is a minimal age barrier in the efficacy of automated reminders sent to patients. As technologies and patients’ proficiencies evolve, the use and dissemination of patient reminders and alerts will also change.

Practice Implications

Automated technology may reliably assist patients to adhere to their health regimen, increase attendance rates, supplement discharge instructions, decrease readmission rates, and potentially reduce clinic costs.

Keywords: automated alerts and reminders, patient-centered care, consumer health informatics, patient adherence, health behavior

1. Introduction

Using information technology (IT) to support patient self-management has the potential to foster shared accountability for healthcare outcomes by improving patient adherence to healthcare regimens. When delivered at the point of care to clinical providers, IT interventions in the form of alerts and reminders have been shown to contribute to improved health outcomes.[1, 2] Currently the majority of alerts have been developed for clinicians to assist them in clinical care management. However, there is growing interest in providing alerts and reminders to patients in order to improve healthcare self-management. Leveraging IT to foster patient engagement in their healthcare regimen may be particularly significant, as a patient only spends a small amount of time in a clinical environment. Increasing the reach of support and guidance of providers from the clinical environment to patient’s daily lives can encourage patients to incorporate health behaviors into their daily routines.[3, 4]

Given that clinical decision support (CDS) elements have benefitted patients when employed in the healthcare environment, it is important to examine the utility when provided to patients outside of the healthcare environment. Providing IT tools to patients and caregivers can facilitate shared accountability for disease management between the healthcare provider and patient.[5] This paper describes a literature review of automated alerts and reminders provided directly to the clinical domains in which they are employed, the technology used, and their efficacy.

1.1 Background

According to the American Medical Informatics Association (2006), CDS provides “clinicians, patients or individuals with knowledge and person-specific or population information, intelligently filtered or presented at appropriate times, to foster better health processes, better individual patient care, and better population health.”[6] CDS enhances decision-making through the use of technology by processing individualized data with an inference mechanism that can generate and deliver relevant information at critical time or interaction points.[7] Alerts and reminders are among the most successful and widely deployed components of CDS that provide timely and relevant information which have the potential to improve health outcomes.[6] A CDS system uses logical software programming that consists of facts and rules, and if conditions are met, an alert or reminder is triggered to notify the intended user of the information contained in the alert. Alerts and reminders are informatics interventions typically delivered through an electronic health record (EHR), a digital record of patient data, but can also include paper mailings and brochures.

Alerts have been used to notify a physician of a contraindicating condition like an allergy, interaction with another medication or supplement (immediate alert), or to prompt a clinician to respond to an abnormal lab value (event-driven alert).[8] Reminders have been used to notify clinicians and patients about appointments like preventive screenings or vaccinations.[9] Alerts and reminders are delivered in several ways that reflect the urgency of the information from a conspicuous pop-up box or text message, which usually indicates that the alert is important, to something as subtle as a change in font that can designate a difference between a generic or brand name medication.[9]

When directly provided to patients, alerts and reminders not only cue patients to complete a desired behavior but can also foster shared accountability and patient autonomy in their heath care management. Currently, there are no reviews that survey direct automated alerts and reminders for patients. This review of the literature on the use of automated alerts and reminders targeted to patients provides an overview of how these interventions have been used, and discusses possible outcomes. Additionally, this review discusses the use of healthcare IT to directly benefit patients.

Medication adherence and management are problematic behaviors for clinicians and researchers to measure and evaluate. However, health IT can improve adherence by both reminding patients to take their medications (execution adherence) and reducing compromised execution of medication use.[10]

2. Methods

2.1 Data Sources and Inclusion Criteria

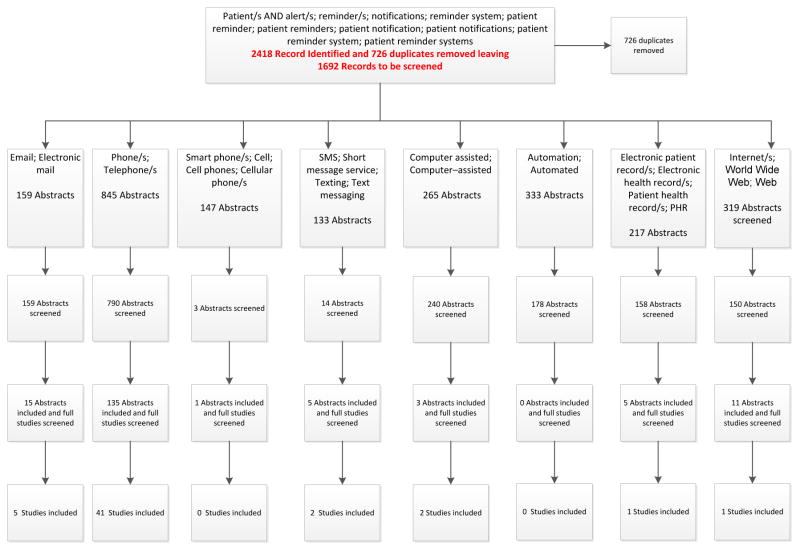

An electronic literature search was conducted in the PubMed database to identify studies on electronic interventions in the form of alerts and reminders targeted specifically for patients. No date filter was initially applied in order to determine the depth of the literature retrieved. The final search was conducted on June 17, 2013. The inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1), search terms (Table 2), and how terms were applied (Figure 1) are displayed below.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion Criteria | English and human |

| Automated approach (alert or reminder had to be programmed to be automatically sent to recipient) | |

Patient alerts or reminders directed to patients or caregivers

| |

| Electronic alerts or reminders that were interventions (implemented) and had an evaluation metric | |

| Exclusion Criteria | Alerts or reminders directed towards clinicians |

| Studies assessing patient preferences or willingness to receive electronic alerts or reminders | |

| Implantable devices that contain information communication technology such as implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) | |

| Articles published before 2003 |

Table 2.

Database Search Terms

| 1 | patient/s |

| 2 | alert/s |

| 3 | reminder/s |

| 4 | notifications, reminder system, patient reminder/s, patient notification/s, patient reminder system/s |

| 5 | internet/s, World Wide Web, Web |

| 6 | electronic patient record/s, electronic health record/s, patient health record/s, PHR |

| 7 | computer/s, computer assisted |

| 8 | short message service, SMS, texting, text messaging |

| 9 | smart phone/s, smartphone/s, cell phone/s, Cellular phone/s |

| 10 | phone/s, telephone/s |

| 11 | email/s, electronic mail |

Figure 1.

Publication selection process

2.2 Data Abstraction

The search produced 2418 abstracts; 726 duplicates were removed, leaving 1692 abstracts (Figure 1). The 1692 abstracts were screened for inclusion by two investigators using the inclusion and exclusion criteria above. Additionally, due to the large number of publications identified for inclusion screening as well as the greater relevance of research on more recent technology, the decision was made to eliminate studies published prior to January 2003. Refinement of our search results yielded a final total of 175 abstracts that were identified for inclusion.

The two raters who evaluated the inclusion/exclusion criteria of each article used a kappa reliability coefficient to determine inter-rater reliability. Both raters determined most articles screened for this review did not meet inclusion criteria. In instances such as this, where the data cluster in one agreement cell (most articles being excluded), the kappa coefficient is known to produce an anomaly that negates its efficacy as a useful statistical test. Therefore, the prevalence-adjusted, bias-adjusted kappa (PABAK) was also calculated, which is not affected by the bunching data pattern.[11] The inter-rater reliability for whether an article did or did not meet the inclusion criteria was acceptably high between the two raters for both tests [kappa = 0.64, 95% CI (0.46, 0.82); prevalence-adjusted bias-adjusted kappa (PABAK) = 0.81, 95% CI (.71, 0.91)].

All articles for the 175 abstracts were pulled and reviewed for final inclusion criteria by four investigators. A total of 51 publications were included in the final analysis and coding.

3. Results

The initial PubMed search yielded 1692 potentially relevant articles. In the title and abstract review 1517 articles were eliminated for not meeting the defined inclusion criteria. The remaining 175 articles underwent full-text review, at which stage 124 articles were rejected because the primary focus of the reminder or alert was aimed at clinicians or the technology intervention used was not automated and/or electronic. A summary of the analysis for the 51 included articles is provided below. The articles are partitioned into alerts and reminders. Alerts are defined as a notice or communications to warn patients of potential harm, problem, or danger with the intention to take action to avoid or address the threat. Reminders are defined as a communication or message to ensure patients remember something, such as an appointment. Many reviewed studies included additional evaluations of the technology, such as usability and cost; however, discussions outside of the feasibility and effect of the alerts and reminders on patient behavior are outside of the scope of this review.

Two manuscripts focused on alerts for patients (Appendix A) and 49 manuscripts were focused on reminders for patients (Appendix B). The majority of study types were quantitative (n=49); two were qualitative and one mixed method study was conducted. 20 types of study designs were used (Table 3) and were conducted in domestic, USA-based (n=24) as well as international (n=27) settings. The range of study participants was 14–271,894.

Appendix A.

Alerts

| Citation | Lawton, (2011)[22] | Cooper, (2010)[21] |

| Clinical Domain | Medications | COPD |

| Reminder Purpose/Technology Intervention | Alert to adverse drug reactions/Mobile phone, web-based application | Weather alert/Automated telephone: |

| Study Objective | Sends customized alert on adverse drug event risk, tailored to participant’s age and condition | Provided calls to participants to warn when the weather forecast for the next few weeks is ‘elevated’. |

| Study n | 18 | 17 |

| Study Design | Semi-structured interview | Qualitative semi-structured telephone interviews |

| Setting | Denmark, hospital clinic in Copenhagen | England, hospital system |

| Measurement | Compared usefulness and utility of web-based application, telephone alert, and paper based medication list. | Qualitative interview |

| Results | The patients found the paper-based medication list useful and comprehensive for control of own prescribed medication. The Web-based prototype also proved to be useful, but drug and lab values were hard to correlate, and the alerts were hard to understand. The cell phone-based prototype proved less useful as the patients were challenged to vision the applicability of the system | Patients perceived the telephone service as appropriate for information delivery. There was variation on perceived usefulness as related to reassurance, medication reminders, and reliability of weather forecasts information. Primary care staff perceived the service as successful, but felt that it lacked participation by hard-to-reach groups (non-English speaking, mild COPD patients). |

Appendix B.

Reminders

| Citation | Martini da Costa, (2010)[24] | Wright, (2008) [13] | Munoz, (2009) [23] | Boman, (2010)[12] |

| Clinical Domain | Primary care | Health Prevention | Health Prevention | Cgnitive Impairment |

| Reminder Purpose/Technology Intervention | Appointment reminder/Text message | Health screening/Tethered Personal Health Records | Healthy behavior/Web-based application, email | Self-care management/Computer home reminder system |

| Study Objective | Assessed efficacy of a text message appointment reminder. | Assessed if sending a health screening reminder via EHR would increase screening. | Assessed efficacy of internet based smoking cessation program. | Assessed if acquired brain injury (ABI) patients could learn to use a set of electronic memory aids integrated in a training apartment, and to identify activities commonly forgotten by patients. |

| Study n | >29000 | 4534 | 1000 | 14 |

| Study Design | Retrospective review | RCT | RCT | Case study |

| Setting | Brazil/Large clinic | USA/11 primary care centers | Worldwide (68 countries)/Internet users enrolled at two websites. | Sweden/TBI clinic |

| Measurement | Appointment non-attendance rates | Number of health screenings sought by patients | Self-reported smoking cessation rates | Number of reminders for activities |

| Results | Non-attendance rates decreased in 3 of 4 clinics: 0.82% (p = .590), 3.55% (p = .009), 5.75% (p = .022), and 14.49% (p = <.001). | Patients significantly increased pap smear screening 1.68 95% CI (1.04–2.70, p < 0.05) - no significant difference for other screenings (p > 0.05). | No significant difference was seen among conditions tested; 7-day abstinence rates over 12 months were 20.2% for Spanish speakers and 21.0% for English speakers. | Participants made significant improvements learning how to use memory aids provided (p < 0.05); no significant correlation was found among the number of kitchen alarms and reminder messages. |

| Citation | Hanauer, (2009)[28] | Dowshen, (2012)[27] | Dokkum, (2012)[26] | DeFrank, (2009)[25] |

| Clinical Domain | Diabetes | HIV | STI | Oncology |

| Reminder Purpose/Technology Intervention | Self-care management/Text message; email | Medication adherence/Text message | Health Screening/Text message; email | Health Screening/Automated telephone call |

| Study Objective | Compared glucose monitoring using email versus text message reminders. | Assessed the effect and feasibility of daily text messages to increase adherence to antiretroviral therapy. | Assessed response rates of chlamydia home testing using mail, email and text message. | Compared efficacy of screening reminders including an automated phone call, mailed letter, and enhanced mailed letter. |

| Study n | 40 | 25 | 93,094 | 3547 |

| Study Design | Randomized sample | Prospective | Case study | RCT |

| Setting | USA/Diabetes center | USA/LGBT focused health center | Netherlands/Public community | USA/North Carolina teacher and state employee database |

| Measurement | Patients entering blood glucose levels on website | Self-reported adherence using the visual analog scale (VAS). | Rate of package return (home chlamydia testing kit) | Appointment attendance rates |

| Results | The text message group requested significantly more reminders (text message group = 180.4, email group = 106.6) and submitted more glucose values (30.0 vs. 6.9 per user, p = 0.04). | Visual analog scale scores increased significantly from a baseline of 74.7 to 93.3 at 12 weeks, p < .001; and 93.1 at 24 weeks, p < .001. | Participation rates increased from 10% to 14% after the email/SMS reminders in round 1, and 7% to 10% in round 2. | Participants receiving automated telephone reminders significantly increased overall repeat mammography adherence following the intervention (17.8% (p<0.0001). |

| Citation | Altuwaijri, (2012)[32] | Holbrook, (2009)[31] | Guy, (2012)[30] | Bourne, (2011)[29] |

| Clinical Domain | Immunization | Diabetes | STI | HIV |

| Reminder Purpose/Technology Intervention | Appointment reminder/Text message | Appointment reminder/Web-based application | Health Screening/Text message | Health Screening/Text message |

| Study Objective | Evaluated the effect of text messaging reminders with electronic medical record on nonattendance rates. | Assessed the impact of electronic shared decision support between the patient and PCP on the quality of diabetes management primary care. | Evaluated text message reminders on chlamydia re-testing rates. | Examined the impact of a text message reminder on HIV/sexually transmitted infection retesting rates among men who have sex with men. |

| Study n | 271,894 | 511 | 338 | 714 |

| Study Design | Retrospective review | RCT | Before and After | Nonrandom cohort comparison |

| Setting | Saudi Arabia/Outpatient clinic of Saudi National Guard | Canada/Community based care providers | Australia/Health center | Australia/Sexual health clinic |

| Measurement | Pre/post intervention attendance rates | A composite score measuring process improvement for mean change in individual patients at baseline and 6 months after randomization. | Chlamydia retesting rates | STI retesting rates |

| Results | Post-intervention non-attendance rates decreased (pre-intervention = 23.9%, post-intervention = 19.7%) 4.13% (p < 0.001, T=4.81). | The intervention group reported process composite scores were significantly higher than the control (1.27, 95% CI 0.79–1.75, p < 0.001); 19.1% improvement was seen in the intervention group (p <0.001); reported satisfaction was higher in the intervention group. | Re-testing was significantly higher in participants after receiving text messages than before (30% vs. 21%, p=0.04); adjusted OR = 1.57 (95% CI 1.01 to 2.46). | HIV/STI re-testing rates were significantly higher in the text message intervention group than the control (64% 30%; P<0.001); HIV/STI re-testing in the intervention group was 4.4 times greater than the control (95% CI 3.5 to 5.5; p < 0.002). |

| Citation | Bender, (2010)[35] | Balato,. (2012)[34] | Arora, (2012)[33] | Armstrong, (2009)[19] |

| Clinical Domain | Asthma | Dermatology | Diabetes | Dermatology |

| Reminder Purpose/Technology Intervention | Medication adherence/Automated telephone call | Treatment adherence/Text message | Healthy behavior/Text message | Healthy behavior/Text message |

| Study Objective | Evaluated the impact of an automated, interactive phone call on adherence to asthma medication. | Determined the impact of text messages on treatment adherence and patient outcomes in psoriasis patients. | Assessed the impact of daily healthy reminders on inner city low income diabetes patients. | Assessed the impact of a text message weather report and reminder to use sunscreen. |

| Study n | 50 | 40 | 23 | 70 |

| Study Design | RCT | RCT | Prospective | RCT |

| Setting | USA/Participants recruited from allergy clinics and through the newspaper | Italy/Dermatology clinics | USA/ED University County Hospital | USA/General population |

| Measurement | Medication adherence | Pre/post intervention self assessment on Psoriasis Area Severity Index, Self-Administered Psoriasis Area Severity Index, body surface area, Physician Global Assessment, Dermatology Life Quality Index, evaluation of patient-physician relationship, adherence to therapy. | Self-reported lifestyle changes, AIC, & self-efficacy | Frequency of sunscreen use |

| Results | Patients in the intervention group had higher adherence by 32% compared to the control group (p = 0.003). Intervention group also had a more favorable shift in perception of inhaled corticosteroids as shown by the BMQ scores (p = 0.003), which also correlated with degree of adherence change (r = 0.342; p = 0.0152). | Intervention group had significant improvement (p < 0.05) in disease severity, quality of life and treatment adherence (p < 0.001). Control group remained stable. | Overall lifestyle improvement was seen following text message reminders (consumption of fruits and vegetables: 56.5% before versus 83% after; exercising: 43.5% before versus 74% after; foot checks: 74% before versus 85% after; self-efficacy increased from 3.9 to 4.2 on the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale). | Daily adherence in the intervention group was significantly higher than the control (56.1% [95% CI, 48.1%–64.1%] versus 30.0% [95% CI, 23.1%–36.9%], p<0.001.) |

| Citation | Chen, (2008)[39] | Britto, (2011)[38] | Bos, (2005)[37] | Boker, (2012)[36] |

| Clinical Domain | Health Screening | Asthma | Orthodontics | Dermatology |

| Reminder Purpose/Technology Intervention | Appointment reminder/Text message; Automated phone call | Customized medical remiders/Text message | Appointment reminder/Text message; Automated phone call | Medication adherence/Text message |

| Study Objective | Compared the effectiveness of text message and phone reminders on appointment attendance rates. | Evaluated feasibility, acceptability, and utility of a text messaging system allowing teenagers to customize medical reminders sent to mobile phones. | Examined multiple types of reminders on orthodontic appointment attendance. | Assessed if daily text reminders increased acne medicine adherence. |

| Study n | 1848 | 19 | 301 | 40 |

| Study Design | RCT | Nonrandomized pilot | RCT | RCT |

| Setting | China/Hospital | USA/Children’s medical center | Netherlands/University dental clinic | USA/Community - university dermatology clinics, medical campus advertisements, and Craigslist.com. |

| Measurement | Appointment attendance rates | Score on asthma control test; a Likert-type scale rating for usefulness and acceptability | Appointment attendance rates | Amount of medication used and severity of acne |

| Results | Attendance rates were highest in the telephone intervention group (88.3%), followed by text message (87.5%) and control (80.5%), showing a significant increase with the text message and telephone groups together (OR 1.698, 95% CI 1.224–2.316, P=0.001; OR1.829, 95% CI 1.333–2.509, P<0.001, respectively) but no significant difference between the two groups (P=0.670). | Participants reported high ratings of usefulness, acceptability, and ease of use. Comparison and intervention group self reported asthma control was similar across the study. | Attendance rates by type of reminder were: mail 90.6%, telephone 90.4%, text 82.4%, and control 83.7%. There was no significant difference in attendance rates (p > 0.05). | There was no significant difference in the adherence rates (p = 0.75) between the intervention group (mean = 33.9%) and the control group (mean = 36.5%); both groups showed improvement in the severity of their acne. |

| Citation | Dick, (2011)[43] | Martini da Costa, (2012)[42] | Corkrey, (2005)[41] | Cocosila, (2008)[40] |

| Clinical Domain | Diabetes | HIV | Oncology | Health prevention |

| Reminder Purpose/Technology Intervention | Self-care management/Text message | Medication adherence/text message | Health screening/Automated interactive telephone call | Adherence to preventative activities/Text message |

| Study Objective | Pilot tested a text messaging system for a diabetes management care adherence system. | Examined the effect and perception of a text messaging reminder system on adherence to antiretroviral medication regimens for HIV-infected women. | Assessed the effect of automated interactive telephone calls delivering screening status and an advisory message on cervical screening rates | Determined the effectiveness of text messaging on healthy behavior adherence. |

| Study n | 18 | 21 | 17,008 | 102 |

| Study Design | Pilot study: surveys and interviews | RCT | RCT | Randomized, unblinded, controlled trial |

| Setting | USA/University primary care group clinics | Brazil/University clinic | Australia/Community | Canada/University-community |

| Measurement | Interview & survey responses | Self-reported adherence, pill counting, microelectronic monitors (MEMS) and a satisfaction interview with respect to incoming messages. | Cervical cancer screening rate | Self-reported healthy behavior adherence and the number of participant text messages |

| Results | Weekly missed medication doses decreased from 1.6 to 0.6 (p = 0.003); confidence significantly increased during and 1 month post-pilot (p = 0.002, p = 0.008); 94 % strongly agreed that text messaging was easy to perform and helped with diabetes self-care; participant response = 80%. | Overall results improved for the intervention group. Self-reported adherence intervention = 100%, control = 84.62%; counting pills compliance intervention = 50%, control = 38.46%; microelectronic monitoring adherence intervention = 75%, control = 46.15%. 81.81% of participants perceived that text messaging assisted with treatment adherence; 90.9% requested to continue to receive text messages after the study. | Intervention group screening rates were 0.43% higher than control. | The intervention group resulted in a larger increase in healthy behavior (246%) than the control group (131%). No significant difference was found in the number of pills missed, a significant correlation was found (coefficient = −0.352, sig. = 0.01) in the intervention group between the average number of text messages sent and number of pills reported missed. |

| Citation | Fischer, (2012)[18] | Feldstein, (2006)[46] | Fairhurst, (2008)[45] | Downer, (2005)[44] |

| Clinical Domain | Diabetes | Primary Care | Primary Care | Outpatient multi-specialty clinics |

| Reminder Purpose/Technology Intervention | Self-care management; Appointment reminder/Text message | Medication adherence/Automated telephone voice message | Appointment reminder/Text message | Appointment reminder/Text message |

| Study Objective | Pilot tested a text messaging system to support self-management behavior for adults with diabetes. | Evaluated automated voice messaging system and lab outreach intervention patient to improve completion of lab monitoring for patients at onset of new study medication. | Evaluated text message appointment reminders for patients who failed to attend two or more appointments in the previous year. | Evaluated the use of automated text messages for outpatient clinic appointment reminders. |

| Study n | 47 | 961 | 173 | 2864 |

| Study Design | Quasi-experimental pilot | Cluster randomized trial | RCT | Cohort study with historical control |

| Setting | USA/Family health clinic | USA/Primary care clinic | Scotland/Inner city general practice | Australia/Children’s hospital |

| Measurement | Patient responses to text and focus group | Quantitative: completion of baseline laboratory testing upon initiation of new study medication. Qualitative: Content analysis. | Appointment non-attendance rates | Appointment attendance rates |

| Results | 1585 text messages were sent with a 68.14% response rate. 98.7% of the responses were correctly formatted. Upon receipt of medical measurement text message requests, 66.4% provided blood sugar values that were correctly formatted. The study was underpowered and no significant changes in study attendance were detected. 8 participants participated in a focus group and reported satisfaction with the program and found the technology easy to use. | Quantitative: Each intervention increased laboratory monitoring: EMR reminder (provider) = 2.5 (95% CI 1.8–3.5), automated voice message reminder (patient) = 4.1 (95% CI 3.0–5.6) lab tech outreach (patient) = 6.7 (95% CI, 4.9–9.0), p < 0.001. Qualitative: Interventions were acceptable to primary care providers and patients. | Non-attendance was lower in the intervention group (=12%) than the control (=17%), however did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.11). | Non-attendance rates were significantly lower in the intervention group than the control (14.2% v 23.4%; p < 0.001). |

| Citation | Gerber, (2009)[50] | Geraghty, (2008)[49] | Franklin, (2008)[48] | Foreman, (2012)[47] |

| Clinical Domain | Weight management | ENT | Diabetes | Medications |

| Reminder Purpose/Technology Intervention | Self-care management/Text message | Appointment reminder/Text message | Self-care management/Two-way text message | Medication adherence/Text message |

| Study Objective | Investigated feasibility of mobile phone text messaging to enable ongoing communication with African-American women participating in a weight management program. | Retrospectively evaluated nonattendance rates after a text reminder system was implemented. | Evaluated utility of the “Sweet Talk” system for type 1 diabetes patients. | Evaluated text message medication reminders on patient’s medication adherence. |

| Study n | 95 | 3981 | 64 | 290 |

| Study Design | Feasibility study | Retrospective review | Descriptive/Qualitative | Retrospective observational cohort analysis |

| Setting | USA/Participants in ORBIT (other) study | UK/Outpatient clinic | UK/Community | USA/Community |

| Measurement | Satisfaction questionnaire and telephone interviews | Appointment non-attendance rates | Frequency of messages sent by patients in response to automated system messages. | Chronic oral medication adherence measured as the proportion of days covered (PDC). |

| Results | Feasibility was demonstrated: 96% of participants reported they read the text messages; 79% reported that the text messages assisted with their weight loss goals. | The text reminder group mean non-attendance rate was 22% (range, 21.9–22.2%) compared to the historical control group of 33.6% (range, 32.1–34.8%) (p < 0.001). | Participants used the Sweet Talk system as a successful communication method with providers. Messages sent in response to the Sweet Talk were almost half of total messages (472/1180). The number of messages participants sent to Sweet Talk was significantly correlated to the number of response messages received by participants (r = .521, P= .01). | Adherence measured by PDC via prescription claims, for the intervention group was significantly higher than the control group (intervention = 85%; control = 77%; p < 0.001). |

| Citation | Hardy, (2011)[20] | Harbig, (2012)[15] | Green, (2013)[52] | Glanz, (2012)[51] |

| Clinical Domain | HIV | Medications | Gastroenterology | Ophthalmology |

| Reminder Purpose/Technology Intervention | Medication adherence/Text message; One way beeper | Medication adherence/Portable electronic reminder service | Health screening/Automated telephone call; EHR linked mailings | Medication adherence; Appointment reminder/Automated interactive telephone call |

| Study Objective | Compared the effects and feasibility of a customized phone-based reminder system versus a one-way pager to motivate and track antiretroviral medication adherence. | Evaluated an electronic reminder system for medication non-adherence with elderly patients with complex health regimens. | Assessed the impact of interventions utilizing electronic health records, automated mailings, and stepped increases in support on colorectal screening adherence. | Evaluated the efficacy of an automated, interactive, telephone based health communication intervention on improvement of glaucoma treatment adherence. |

| Study n | 31 | 168 | 4675 | 312 |

| Study Design | Parallel | RCT | RCT | RCT |

| Setting | USA/Large teaching hospital | Denmark/Patients recruited from National Health Insurance Population Register | USA/21 primary care medical centers | USA/Hospital based ophthalmology clinics |

| Measurement | Medication adherence using multiple measures | Medication adherence monitoring | Proportion of patients current for screening | Medication adherence and appointment attendance rates |

| Results | Phase I resulted in intervention content development. Phase II mean percent adherence rates by pill count, self-report, and medication event monitoring system remained significantly higher in the mobile phone group at weeks 3 and week 6. | A significant difference in overall adherence was found between the automated electronic reminder service (Telesvar) 79% and (control) pill count 92% (p < 0.000), with the most reliable method of medication adherence monitoring was pill count. | The intervention group demonstrated overall significantly more current screenings, including increases by intensity (usual care: 26.3% [95% CI, 23.4–29.2%]; automated: 50.8% [CI, 47.3–54.4%]; assisted: 57.5% [CI, 54.5–60.6%]; navigated: 64.7% [CI, 62.5–67.0%]; p < 0.001). | All 6 adherence measures significantly improved from baseline in both the intervention and control group (p<0.01); participants in the intervention group did provide feedback reporting that the automated message system was easy to use, relevant, and recommended continuation. |

| Citation | LeBaron, (2004)[56] | Koshy, (2008)[55] | Homko, (2012)[54] | Henry, (2012)[53] |

| Clinical Domain | Immunization | Ophthalmology | Diabetes | HIV |

| Reminder Purpose/Technology Intervention | Immunization/Automated telephone call | Appointment reminder/Text message | Medical monitoring parameters documentation/Automated interactive telephone call | Appointment reminder/Automated telephone call |

| Study Objective | Evaluated the impact of registry-based, reminder-recall interventions on immunization rates. | Assessed the efficacy of text message appointment reminders to increase attendance at a hospital based ophthalmology clinic. | Evaluated enhanced telemedicine systems targeting glucose control and pregnancy outcomes for women with gestational diabetes. | Evaluated an automated telephone reminder that was added to the standard set of three HIV clinic appointment reminders to reduce no-shows for HIV primary care appointments. |

| Study n | 3050 | 9959 | 80 | 584 |

| Study Design | RCT | Observational | RCT | Quasi-experimental |

| Setting | USA/County clinics | UK/Hospital-based ophthalmology clinic | USA/Prenatal clinics | USA/VA HIV primary care clinic |

| Measurement | Completion of 24 month vaccination series | Appointment non-attendance rates | Blood glucose level, infant birth weight, communication between provider and patient | Appointment non-attendance rates |

| Results | Overall, all intervention groups resulted in somewhat higher vaccination rates, however only the auto dialer group results were significant for the entire vaccination series (p = 0.02). | The intervention group resulted in a 38% decrease in appointment non-attendance (relative risk of non-attendance = 0.62; 95% CI 0.48 – 0.80, p = 0.0002). | No significant differences were seen between telemedicine and control groups for maternal blood glucose levels (p = 0.53) and infant birth weight (p = 0.3). Data transfer between provider and patient increased significantly however among the telemedicine group (p<0.01) | The intervention did not reduce missed appointments among many of the patient subgroups, and the greatest effect was seen among the least vulnerable populations. Patients who weren’t homeless (OR= 0.77, CI = 0.61–0.98), non depressed patients (OR = 0.65, CI = 0.49–0.86), patients with 5> appointments in 6 months (OR = 0.66, CI = 0.47–0.92) had significantly fewer no-shows post intervention (p < .05). |

| Citation | Perry, (2011)[59] | Parker, (2012)[14] | Parikh, (2010)[58] | Lin, (2012)[57] |

| Clinical Domain | Dental | Medications | Outpatient multi-specialty clinics | Ophthalmology |

| Reminder Purpose/Technology Intervention | Appointment reminder/Text message | Medication adherence/Electronic personal response unit | Appointment reminder/Automated telephone call | Appointment reminder/Text message |

| Study Objective | Examined the use of automated text reminders to improve attendance rates for two dental practices | To determine the usability, acceptability, and effectiveness of an electronic medication reminder system on medication adherence. | Comparison of an automated appointment reminder system, a clinic staff reminder, and no reminder on clinic nonattendance rates. | Evaluated the impact of a text message service targeting improvement on follow-up adherence and procedures completion for parents of children with cataracts. |

| Study n | 150 | 31 | 9835 | 135 |

| Study Design | Retrospective review | Prospective | Prospective, randomized, parallel clinical trial | RCT |

| Setting | Scotland/Dental clinic | New Zealand/GP practices | USA/Academic outpatient clinic | China/Ophthalmic center |

| Measurement | Appointment non-attendance rates | Patient compliance, perception of the service, and health-related quality of life measures. | Appointment non-attendance rates | Appointment attendance rates |

| Results | The non-attendance rate significantly decreased overall (p = 0.001) from 31% (46/150) to 14% (21/150). Both practices individually had significantly reduced non-attendance rates (practitioner A, p = 0.04; practitioner B, p = 0.01). | Rate of self-assessed medication compliance significantly improved from pre (52%) and post (81%) implementation (p = 0.012). There was a significant improvement in perceived self-care at home ability (p = 0.001). The percentage of participants who rated their self-care at home ability as excellent increased from 42% to 68%. | The most effective intervention was a clinic staff reminder followed by an automated reminder; no reminder was least effective (non-attendance rates = 13.6%, 17.3%, and 23.1%, respectively; p=0.004). | Attendance rates for the intervention group were significantly higher than those for the control group (91.3% vs 62.0%, p = 0.005). |

| Citation | Suffoletto, (2012)[63] | Solomon, (2007)[62] | Sims, (2012)[61] | Pop-Eleches, (2011)[60] |

| Clinical Domain | Medications | Osteoporosis | Mental health | HIV |

| Reminder Purpose/Technology Intervention | Medication adherence/Text message | Health screening/Automated telephone call | Appointment reminder/Text message | Medication adherence/Text message |

| Study Objective | Assessed the impact of an automated text messaging system on adherence to post-discharge antibiotic prescriptions. | Tested mailed letters and automated telephone calls designed to improve osteoporosis management among primary care physicians. | Examined the effect of text message reminders on the attendance of appointments at four community mental health clinics. | Examined the impact of text message reminders on anti-retroviral therapy adherence. |

| Study n | 144 | 2407 | 2817 | 431 |

| Study Design | RCT | RCT | Nonrandomized pilot | RCT |

| Setting | USA/Emergency department | USA/Primary care practices | UK/Outpatient mental health clinic | Kenya/Rural clinic |

| Measurement | Patient self-report adherence questionnaire | Undergoing a bone mineral density (BMD) testing or filling a prescription for a boneactive medication during the 10 months of follow-up. | Appointment attendance rates | Medication adherence |

| Results | Adherence rates were not significant between intervention and control groups (57% vs. 45%; p = 0.1). | A statistically significant 4% absolute increase and a 45% relative increase (95% confidence interval 9–93%, p = 0.01) in osteoporosis management was found between groups. | The text message reminder intervention significantly increased appointment attendance (p < .001). | 53% of the weekly SMS reminders group achieved adherence of at least 90%, compared with 40% of participants in the control group (p = 0.03). The weekly reminders group were significantly less likely to experience treatment interruptions exceeding 48h than participants in the control group (81 vs. 90%, p = 0.03). |

| Citation | Suh, (2012)[64] | Suffoletto, (2012)[63] | Solomon, (2007)[62] | Sims, (2012)[61] | Pop-Eleches, (2011)[60] |

| Clinical Domain | Immunization | Medications | Osteoporosis | Mental health | HIV |

| Reminder Purpose/Technology Intervention | Immunization/Automated telephone call | Medication adherence/Text message | Health screening/Automated telephone call | Appointment reminder/Text message | Medication adherence/Text message |

| Study Objective | Assessed the impact of an immunization reminder/recall notification via letter or auto-dialer on increasing immunization rates for TdaP, MCV4, and first dsoe HPV. | Assessed the impact of an automated text messaging system on adherence to post-discharge antibiotic prescriptions. | Tested mailed letters and automated telephone calls designed to improve osteoporosis management among primary care physicians. | Examined the effect of text message reminders on the attendance of appointments at four community mental health clinics. | Examined the impact of text message reminders on anti-retroviral therapy adherence. |

| Study n | 1596 | 144 | 2407 | 2817 | 431 |

| Study Design | RCT | RCT | RCT | Nonrandomized pilot | RCT |

| Setting | USA/Private pediatric practices | USA/Emergency department | USA/Primary care practices | UK/Outpatient mental health clinic | Kenya/Rural clinic |

| Measurement | Receipt of > 1 targeted vaccines and receipt of all targeted vaccines 6 months postintervention. | Patient self-report adherence questionnaire | Undergoing a bone mineral density (BMD) testing or filling a prescription for a boneactive medication during the 10 months of follow-up. | Appointment attendance rates | Medication adherence |

| Results | The intervention group received significantly higher vaccine rates that the control for a minimum of one vaccine (47.1% versus 34.6%, p < 0.0001) and receipt of all vaccines (36.2% versus 25.2%, p < 0.0001). | Adherence rates were not significant between intervention and control groups (57% vs. 45%; p = 0.1). | A statistically significant 4% absolute increase and a 45% relative increase (95% confidence interval 9–93%, p = 0.01) in osteoporosis management was found between groups. | The text message reminder intervention significantly increased appointment attendance (p < .001). | 53% of the weekly SMS reminders group achieved adherence of at least 90%, compared with 40% of participants in the control group (p = 0.03). The weekly reminders group were significantly less likely to experience treatment interruptions exceeding 48h than participants in the control group (81 vs. 90%, p = 0.03). |

Table 3.

Study Designs

| Study Design | Study Type | n |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-post | Quantitative | 1 |

| Case study | Quantitative | 2 |

| Cluster randomized trial | Mixed | 1 |

| Cohort study | Quantitative | 1 |

| Descriptive/Qualitative | Quantitative | 1 |

| Feasibility | Quantitative | 1 |

| Nonrandomized cohort comparison | Quantitative | 1 |

| Nonrandomized pilot | Quantitative | 2 |

| Observational | Quantitative | 1 |

| Parallel study | Quantitative | 1 |

| Pilot surveys/interviews | Qualitative | 1 |

| Prospective | Quantitative | 3 |

| Prospective, randomized, parallel clinical trial | Quantitative | 1 |

| Quasi-experimental | Quantitative (1) Qualitative (1) |

2 |

| Semi-structured interviews | Quantitative | 2 |

| Randomized non-blinded controlled trial | Quantitative | 1 |

| Randomized sample | Quantitative | 1 |

| Randomized control trial | Quantitative | 23 |

| Retrospective review | Quantitative | 4 |

| Retrospective observational cohort analysis | Quantitative | 1 |

| Total | Quantitative | 51 |

Twenty-two clinical domains were identified in the 51 articles included in the review (Table 4). The greatest number of studies were conducted in the domains of diabetes (n=7), HIV (n=6), and medication support (n=5), (defined as interventions designed to support the participant in taking or managing medications).

Table 4.

Clinical Domains

| Domains | n |

|---|---|

| Asthma | 2 |

| Cognitive impairment | 1 |

| Dental | 1 |

| COPD | 1 |

| Dermatology | 3 |

| Diabetes | 7 |

| ENT | 1 |

| Gastroenterology | 1 |

| Health prevention | 3 |

| Health screening | 1 |

| HIV | 6 |

| Immunization | 3 |

| Medication support | 5 |

| Mental health | 1 |

| Oncology | 2 |

| Ophthalmology | 3 |

| Orthodontics | 1 |

| Osteoporosis | 1 |

| Outpatient multispecialty clinics | 2 |

| Primary care | 3 |

| STI | 2 |

| Weight management | 1 |

| Total | 51 |

In 78% (n=40) of the studies reviewed, there was a positive impact resulting from the intervention studied, 15% (n=9) showed no difference, and less than 1% (n=2) of the studies reported a reduced or negative impact from the intervention compared to the control listed in the studies. Some studies targeted multiple intervention purposes; in total, 10 specific types of reminder or alert purposes were identified among the 51 studies (Table 5). Study purposes for appointment reminders (n=12), health screenings (n=8), and medication adherence (n=8) were the most common intervention purposes to have a positive impact; of note, the greatest number of studies overall were also conducted in these same domains (n=16, 8, and 12, respectively). Details of the results by intervention purpose follow in Table 5.

Table 5.

Purposes and Results

| Intervention purpose | Total n | Positive Impact | No Difference | Negative Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appointment reminder | 16 | 12 | 4 | 0 |

| Customized medical reminders | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Healthy behavior | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Health screening | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Immunization | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Medical monitoring | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Medication adherence | 12 | 8 | 3 | 1 |

| Preventive activity adherence | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Self-care management | 8 | 7 | 0 | 1 |

| Treatment adherence | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 51 | 42 | 9 | 2 |

A total of 11 types of automatic technologies were used to remind or alert patients, with several studies utilizing more than one technology type (for example sending a text message and an email to a participant). See Table 6. The most successful studies demonstrated a positive impact by utilizing text messaging (n=27), followed by automated telephone calls (n=10). Text messaging and automated phone messages were also the most frequently used intervention types (n=31, 11, respectively). Details of the results by technology intervention follow in Table 6.

Table 6.

Technology Interventions

| Technology Intervention Type | Total n | Positive Impact | No Difference | Negative Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Automated interactive telephone call | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Automated telephone call | 12 | 10 | 2 | 0 |

| Computer home reminder system | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Electronic medical record linked mailing | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Electronic personal response unit | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| One way beeper | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Portable electronic reminder service | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Text message | 31 | 27 | 4 | 0 |

| Tethered personal health record | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Web-based application | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 56 | 45 | 10 | 2 |

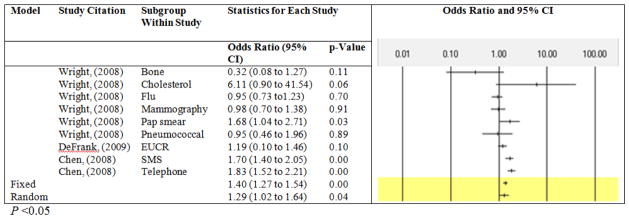

3.1 Meta-Analysis

A meta-analysis was conducted for the randomized controlled studies (RTC). Out of the 51 studies, 23 studies were RTCs. Three out of the 23 RTC studies were included in the meta-analysis (Figure 2). Twenty of the RTC studies were omitted from the meta-analysis because they did not provide sufficient statistics to allow calculation of information about relative probability of the event (Higgins & Green, 2011). Details of the results are presented in Figure 2. Three events (pap smear, SMS, telephone) were found to be statistically significant. Wright et al. (2008) results indicate that the odds of screening is 1.68 (CI:1.04 to 2.71)higher given the presence of a pap smear and was statistically significant (P <0.05). Chen et al. (2008) results indicate that the odds of attendance is 1.70 (CI:1.40 to 2.05) higher given the presence of SMS reminder and1.83 (CI:1.52 to 2.21) given the presence of telephone reminder, and were both statistically significant (P <0.05). The pooled odds ratio indicate that with 95% confidence the odds in favor of attendance or screening were between 1.02 and 1.64 times greater in subjects who received reminders and was statistically significant (P <0.05).

Figure 2.

Meta-Analysis Results

3.2 Notable Technology

Four types of technology interventions are particularly worth noting and are briefly described below.

Computer home reminder system

One study by Boman et al. (2010) targeted patients suffering from memory problems associated with acquired brain injuries (ABI).[12] A set of electronic memory aids was provided in a home-like training apartment to assist patients in remembering forgotten activities. Patients stayed in the apartment for five days, during which time their activities were monitored. Defined activities that were performed were registered into the system and forgotten activities triggered an automated reminder or alarm to remind the patient of the activity. The number of triggered reminders was used to measure changes through the stay. By the completion of the five days, patients demonstrated significant improvements with the use of the memory aids.[12]

Tethered Personal Health Records (EHRs)

Patient Gateway, a patient personal healthcare record (PHR) system was linked to the healthcare organization’s electronic health record (EHR) system. Reminders for seven conditions (bone density testing, cholesterol testing for coronary disease or diabetes, general cholesterol testing, influenza vaccination, mammography, Pap smear and pneumococcal vaccination) were sent to patients from the EHR to the PHR. Tethered PHR systems allow patients to access their own records through a secure portal and view, for example, reminders, lab results, and health screenings history. Study participants in the Pap smear group that opened the reminders completed Pap smear testing significantly more often than matched controls. Reminders for testing for the other conditions were not significant, however the reasons for the differences were not fully explored in this study.[13]

Portable electronic reminder service

A personal response unit was used in one study to remind patients to take medications. The personal response unit (PRU) was a small, portable, battery powered device that was programmed by the patients’ general practitioner in consultation with the pharmacist to send audible and visual medication reminders at designated times throughout the day. The PRU also displayed the date, time, and weather. Once the device sent an alert, the patient pressed a button on the device; otherwise the device sent continuous alerts at designated intervals. The device was programmed in the physician’s office and taken home by the patient. Results demonstrated that physician review of patient compliance status, patient self-assessed medication compliance, and patient perceived self-care ability all significantly improved.[14]

Electronic personal response unit

This study demonstrated a health IT intervention that can support patient’s adherence to prescribed medication. Patients were given an electronic reminder system called Telesvar (TS). About the same size as a cell phone, the TS device used text messaging to receive and send short messages to and from a server. Patients pressed a button to confirm they had taken their medication. If a patient did not confirm that they took their scheduled medication, the server sent a code to the TS device and triggered the reminder signal, which was repeated in 30 minutes if still not confirmed. Electronic reminders, when compared to pill count, were a less reliable method to measure adherence.[15]

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1 Discussion

While the greatest number of studies in this review focused on automated reminders sent to patients to improve attendance rates for appointments, other studies bring to light the efficacy of using automated technologies to help patients achieve improved health outcomes through the use of automated alerts. Recognizing potential benefits to patients and providers, the US government has provided financial incentives for providers to increase use of technology to assist in the delivery of health care. The use of electronic and automated reminders to compliment the use of electronic health records and online health monitoring systems is has become increasingly popular across the globe. Unlike clinician alerts, comparatively few studies have thus far investigated the emerging trends of automated patient alerts, but have become a growing trend. More than half (61%; n = 32) of the studies included in our review were published since 2010.

The majority of the studies that used a behavior reminder intervention targeted chronic conditions such as asthma, obesity, and HIV. The use of automated technologies to remind patients to perform a behavior such as taking medications, eating more fruits and vegetables, or adhering to a complex medication regimen can serve to augment in-clinic education, which can facilitate behavior change. Evidence suggests that patients only comprehend and understand a small percent of what health care providers discuss with them in the clinic setting.[16] Using behavior reminders can help to reiterate and reinforce what was discussed in the clinic setting. It is also important to note that adherence to a prescribed regimen increases patients’ autonomy, self-efficacy, and long-term health outcomes. [17]

When reflecting on the use of text messages patients stated that the messages were a way to feel more connected to their provider and engaged in their health care.[18] Patients also reported that they were more likely to adhere to a suggested regimen or advice if the message was personalized [19] and if the reminder required an action from the patient such as turning off the reminder.[20] However, care must be taken to observe patient privacy and avoid the potential for others to view sensitive messages sent to mobile phones. As technology changes to allow alerts to be presented in a more discrete way this aspect might change. Further, while some patients preferred letters mailed through the postal system, most preferred an individual message sent directly to their personal mobile phone.

Automated reminders and alerts were effective across genders, age groups, and socio-economic status. Appointment reminders increased attendance regardless of the type of appointment. Automated reminders targeted at modifying behaviors were also shown to be effective. Automated appointment reminders increase attendance rates and have the potential to decrease clinic costs due to missed appointments and reduce on the time it takes for clinic staff to contact and remind patients of their appointments. The literature also suggests that text messaging is an effective way to alert patients of an upcoming appointment regardless of their age.

4.2 Limitations

There is an overwhelming amount of literature on the use of specific technology to improve health outcomes. To narrow our findings we restricted our search to automated technology. There are a great number of studies that used text messaging, emails, and/or other technologies to assist patients in adhering to their health regimens that were not automated. For example, studies where nurses, research assistants, or other clinicians sent such notifications manually were excluded. We excluded all studies that did not employ an automated approach to narrow our search results. This limits our findings to a partial picture of the use of health technologies.

4.3 Practice Implications

Use and dependency on technology in healthcare is well established and growing. Our findings indicate that automated technology may reliably assist patients to adhere to their health regimen. Automated appointment reminders, for instance, may increase attendance rates and potentially reduce clinic costs. Automated electronic reminders and alerts may also be used to supplement discharge instructions, increasing adherence and thereby decreasing readmission rates. Sending electronic messages increases patients’ exposure to educational material pertaining to their illness and has the potential to allow patients to reflect on the material in a setting away from the clinician. The use of an automated electronic reminder system may also supplement discharge instructions to decrease readmission rates and encourage adherence to discharge plans.

4.4 Conclusion

Our review indicates that reminders and alerts are advantageous in many ways; they can be used to reach patients outside of regular clinic settings and they can be tailored for individual messages. An unanticipated finding in the literature indicates there is a minimal age barrier in the efficacy of automated reminders sent to patients. As technology and patients’ proficiency with technology evolves, the use and dissemination of patient alerts will change. The predominant type of alert currently used is text messaging by mobile phone. This trend is likely to change as newer technologies emerge, providers broaden their use of alerts to encompass a greater breadth of purposes, and patients become more involved in the management of their own healthcare.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant # R01 AT006548.

We would like to thank Greg Stoddard for advising on the statistical analysis, Douglas Redd for his assistance conducting the meta-analysis, and Carrie Christensen for proof reading this article.

References

- 1.Health Information Technology. Improved Diagnostics & Patient Outcomes. 2014 [cited 2015 May 22]. Available from: http://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/improved-diagnostics-patient-outcomes.

- 2.Health Information Technology. Updated Literature Review Shows that Meaningful Use of Health IT Improves Quality, Safety, and Efficiency Outcomes. 2014 [cited 2015 May 22]. Available from: http://www.healthit.gov/buzz-blog/electronic-health-and-medical-records/meaningful-use-healthit-improves-quality-safety-efficiency-outcomes/

- 3.American Heart Association. Report: Performance Measures Should Include Patient Actions. 2014 [cited 2015 May 22]. Available from: http://newsroom.heart.org/news/report:-performance-measures-should-include-patient-actions.

- 4.Sands DZ. Why participatory medicine? Journal of Participatory Medicine. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams AB. Technology TOotNCfHI, editor. Issue Brief: Medication Adherence and Health IT. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osheroff JA, Teich JM, Middleton B, Steen EB, Wright A, Detmer DE. A roadmap for national action on clinical decision support. Journal Of The American Medical Informatics Association: JAMIA. 2007;14(2):141–5. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Health Information Technology. Clinical Decision Support (CDS) 2013 [cited 2015 June 4]. Available from: http://www.healthit.gov/policy-researchers-implementers/clinical-decision-support-cds.

- 8.HIMSS. Types of Clinical Decision Support: Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society. 2011 [cited 2015 May22]. Available from: http://www.himss.org/files/himssorg/content/files/typescds.pdf.

- 9.Health Information Technology. Advancing Clinical Decision Support: Clinical Decision Support Starter Kit. 2011 [cited 2015 May 22]. Available from: http://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/del-3-7-starter-kit-intro.pdf.

- 10.Health Information Technology. Issue Brief: Medication Adherence and Health IT. 2014 [cited 2015 June 4]. Available from: http://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/medicationadherence_and_hit_issue_brief.pdf.

- 11.Byrt T, Bishop J, Carlin JB. Bias, prevalence and kappa. Journal Of Clinical Epidemiology. 1993;46(5):423–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90018-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boman IL, Lindberg Stenvall C, Hemmingsson H, Bartfai A. A training apartment with a set of electronic memory aids for patients with cognitive problems. Scandinavian journal of occupational therapy. 2010;17(2):140–8. doi: 10.3109/11038120902875144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright A, Poon E, Wald J, Schnipper J, Grant R, Gandhi T, et al. proceedings As, editor. Effectiveness of health maintenance reminders provided directly to patients. 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parker R, Frampton C, Blackwood A, Shannon A, Moore G. An electronic medication reminder, supported by a monitoring service, to improve medication compliance for elderly people living independently. Journal of telemedicine and telecare. 2012 Apr;18(3):156–8. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2012.SFT108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harbig P, Barat I, Damsgaard EM. Suitability of an electronic reminder device for measuring drug adherence in elderly patients with complex medication. Journal of telemedicine and telecare. 2012 Sep;18(6):352–6. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2012.120120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson A, Sandford J. Written and verbal information versus verbal information only for patients being discharged from acute hospital settings to home: systematic review. Health education research. 2005 Aug;20(4):423–9. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horwitz RI, Horwitz SM. Adherence to treatment and health outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153(16):1863–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischer H, Moore S, Ginosar D, Davidson A, Rice-Peterson C, Durfee M, et al. Care by Cell Phone Text Messaging for Chronic Disease Management. American Journal of Managed Care. 2012;18(2):e42–e7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armstrong A, Watson A, Makredes M, Frangos J, Kimball A, Kvedar J. Text-message reminders to improve sunscreen use- a randomized, controlled trial using electronic monitoring. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(11):1230–6. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hardy H, Kumar V, Doros G, Farmer E, Drainoni ML, Rybin D, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a personalized cellular phone reminder system to enhance adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2011 Mar;25(3):153–61. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper R, O’Hara R. Patients’ and staffs’ experiences of an automated telephone weather forecasting service. Journal of health services research & policy. 2010 Apr;15(Suppl 2):41–6. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2009.009101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawton K, Skjoet P. Assessment of three systems to empower the patient and decrease the risk of adverse drug events. Studies In Health Technology And Informatics. 2011;166:246–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Munoz RF, Barrera AZ, Delucchi K, Penilla C, Torres LD, Perez-Stable EJ. International Spanish/English Internet smoking cessation trial yields 20% abstinence rates at 1 year. Nicotine & tobacco research: official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2009 Sep;11(9):1025–34. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.da Costa TM, Salomao PL, Martha AS, Pisa IT, Sigulem D. The impact of short message service text messages sent as appointment reminders to patients’ cell phones at outpatient clinics in Sao Paulo, Brazil. International journal of medical informatics. 2010 Jan;79(1):65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeFrank JT, Rimer BK, Gierisch JM, Bowling JM, Farrell D, Skinner CS. Impact of mailed and automated telephone reminders on receipt of repeat mammograms: a randomized controlled trial. American journal of preventive medicine. 2009 Jun;36(6):459–67. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dokkum NF, Koekenbier RH, van den Broek IV, van Bergen JE, Brouwers EE, Fennema JS, et al. Keeping participants on board: increasing uptake by automated respondent reminders in an Internet-based chlamydia screening in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:176. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dowshen N, Kuhns LM, Johnson A, Holoyda BJ, Garofalo R. Improving adherence to antiretroviral therapy for youth living with HIV/AIDS: a pilot study using personalized, interactive, daily text message reminders. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(2):e51. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanauer DA, Wentzell K, Laffel N, Laffel LM. Computerized Automated Reminder Diabetes System (CARDS): e-mail and SMS cell phone text messaging reminders to support diabetes management. Diabetes technology & therapeutics. 2009 Feb;11(2):99–106. doi: 10.1089/dia.2008.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. updated March 2011. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bourne C, Kinight V, Wand H, Lu H, McNulty A. Short message service reminder intervention doubles sexually transmitted infection-HIV re-testing rates among men who have sex with men. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2011;87:229–31. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.048397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guy R, Wand H, Knight V, Kenigsberg A, Read P, McNulty A. SMS reminders improve re-screening in women and heterosexual men with chlamydia infection at Sydney Sexual Health Centre- a before-and-after study. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2013;89:11–5. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holbrook A, Thabane L, Keshavjee K, Dolovich L, Bernstein B, Chan D, et al. Individualized electronic decision support and reminders to improve diabetes care in the community: COMPETE II randomized trial. CMAJ. 2009 Jul 7;181(1–2):37–44. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altuwaijri M, Sughayr A, Hassan M, AlAzwari F. The effect of integrating short messaging services’ reminders with electronic medical records on non-attendance rates. Saudi Med J. 2012;33(2):193–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arora S, Peters AL, Agy C, Menchine M. A mobile health intervention for inner city patients with poorly controlled diabetes: proof-of-concept of the TExT-MED program. Diabetes technology & therapeutics. 2012 Jun;14(6):492–6. doi: 10.1089/dia.2011.0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balato N, Megna M, Di Costanzo L, Balato A, Ayala F. Educational and motivational support service: a pilot study for mobile-phone-based interventions in patients with psoriasis. The British journal of dermatology. 2013 Jan;168(1):201–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bender BG, Apter A, Bogen DK, Dickinson P, Fisher L, Wamboldt FS, et al. Test of an interactive voice response intervention to improve adherence to controller medications in adults with asthma. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010 Mar-Apr;23(2):159–65. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2010.02.090112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boker A, Feetham HJ, Armstrong A, Purcell P, Jacobe H. Do automated text messages increase adherence to acne therapy? Results of a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012 Dec;67(6):1136–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bos A, Hoogstraten J, Prahl-Andersen B. Failed appointments in an orthodontic clinic. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005 Mar;127(3):355–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Britto MT, Munafo JK, Schoettker PJ, Vockell AL, Wimberg JA, Yi MS. Pilot and feasibility test of adolescent-controlled text messaging reminders. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2012 Feb;51(2):114–21. doi: 10.1177/0009922811412950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen ZW, Fang LZ, Chen LY, Dai HL. Comparison of an SMS text messaging and phone reminder to improve attendance at a health promotion center: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Zhejiang University Science B. 2008 Jan;9(1):34–8. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B071464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cocosila M, Archer N, Haynes RB, Yuan Y. Can wireless text messaging improve adherence to preventive activities? Results of a randomised controlled trial. International journal of medical informatics. 2009 Apr;78(4):230–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corkrey R, Parkinson L, Bates L. Pressing the key pad: trial of a novel approach to health promotion advice. Preventive medicine. 2005 Aug;41(2):657–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.da Costa TM, Barbosa BJ, Gomes e Costa DA, Sigulem D, de Fatima Marin H, Filho AC, et al. Results of a randomized controlled trial to assess the effects of a mobile SMS-based intervention on treatment adherence in HIV/AIDS-infected Brazilian women and impressions and satisfaction with respect to incoming messages. International journal of medical informatics. 2012 Apr;81(4):257–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dick J, Nundy S, Solomon M, Bishop K, Chin M, Peek M. Feasibility and usability of a text message-based program for diabetes self-management in an urban African-American population. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology. 2011;5(5):1246–54. doi: 10.1177/193229681100500534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Downer S, Meara J, Da Costa A. Use of SMS text messaging to improve outpatient attendance. Medical Journal of Australia. 2005;183(7):366–8. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb07085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fairhurst K, Sheikh A. Texting appointment reminders to repeated non-attenders in primary care-randomised controlled study. Qual SAf Health Care. 2008;17:373–6. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2006.020768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feldstein A, Smith D, Perrin N, Yang X, Rix M, Raebel M, et al. Improved therapeutic monitoring with several interventions- a randomized trial. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166:1848–54. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Foreman KF, Stockl KM, Le LB, Fisk E, Shah SM, Lew HC, et al. Impact of a text messaging pilot program on patient medication adherence. Clinical therapeutics. 2012 May;34(5):1084–91. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Franklin VL, Greene A, Waller A, Greene SA, Pagliari C. Patients’ engagement with “Sweet Talk” - a text messaging support system for young people with diabetes. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10(2):e20. doi: 10.2196/jmir.962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Geraghty M, Glynn F, Amin M, Kinsella J. Patient mobile telephone ‘text’ reminder: a novel way to reduce non-attendance at the ENT out-patient clinic. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2008 Mar;122(3):296–8. doi: 10.1017/S0022215107007906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gerber BS, Stolley MR, Thompson AL, Sharp LK, Fitzgibbon ML. Mobile phone text messaging to promote healthy behaviors and weight loss maintenance: a feasibility study. Health informatics journal. 2009 Mar;15(1):17–25. doi: 10.1177/1460458208099865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Glanz K, Beck AD, Bundy L, Primo S, Lynn MJ, Cleveland J, et al. Impact of a health communication intervention to improve glaucoma treatment adherence. Results of the interactive study to increase glaucoma adherence to treatment trial. Archives of ophthalmology. 2012 Oct;130(10):1252–8. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Green B, Wang C, Anderson M, Chubak J, Meenan R, Vernon S, et al. An automated intervention with stepped increases in support to increase uptake of colorectal cancer screening a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:301–11. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303050-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Henry SR, Goetz MB, Asch SM. The effect of automated telephone appointment reminders on HIV primary care no-shows by veterans. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care: JANAC. 2012 Sep-Oct;23(5):409–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Homko CJ, Deeb LC, Rohrbacher K, Mulla W, Mastrogiannis D, Gaughan J, et al. Impact of a telemedicine system with automated reminders on outcomes in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes technology & therapeutics. 2012 Jul;14(7):624–9. doi: 10.1089/dia.2012.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koshy E, Car J, Majeed A. Effectiveness of mobile-phone short message service (SMS) reminders for ophthalmology outpatient appointments: observational study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2008;8:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-8-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.LeBaron C, Starnes D, Rask J. The impact of reminder-recall interventions on low vaccination coverage in an inner-city population. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158:255–61. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin H, Chen W, Luo L, Congdon N, Zhang X, Zhong X, et al. Effectiveness of a short message reminder in increasing compliance with pediatric cataract treatment: a randomized trial. Ophthalmology. 2012 Dec;119(12):2463–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Parikh A, Gupta K, Wilson AC, Fields K, Cosgrove NM, Kostis JB. The effectiveness of outpatient appointment reminder systems in reducing no-show rates. Am J Med. 2010 Jun;123(6):542–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Perry J. A preliminary investigation into the effect of the use of the Short Message Service (SMS) on patient attendance at an NHS Dental Access Centre in Scotland. Primary Dental Care. 2011;18(4):145–9. doi: 10.1308/135576111797512810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pop-Eleches C, Thirumurthy H, Habyarimana JP, Zivin JG, Goldstein MP, de Walque D, et al. Mobile phone technologies improve adherence to antiretroviral treatment in a resource-limited setting: a randomized controlled trial of text message reminders. AIDS. 2011 Mar 27;25(6):825–34. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834380c1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sims H, Jakobsen H, Sanghara H, Tsakanikos E, Hayes D, Okocha C, et al. Text message reminders of appointments a pilot intervention at four community mental health clinics in London. Psychiatric Services. 2012;63:161–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Solomon DH, Polinski JM, Stedman M, Truppo C, Breiner L, Egan C, et al. Improving care of patients at-risk for osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2007 Mar;22(3):362–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0099-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Suffoletto B, Calabria J, Ross A, Callaway C, Yealy DM. A mobile phone text message program to measure oral antibiotic use and provide feedback on adherence to patients discharged from the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2012 Aug;19(8):949–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suh CA, Saville A, Daley MF, Glazner JE, Barrow J, Stokley S, et al. Effectiveness and net cost of reminder/recall for adolescent immunizations. Pediatrics. 2012 Jun;129(6):e1437–45. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]