Abstract

Due to their data-driven nature, multivariate methods such as canonical correlation analysis (CCA) have proven very useful for fusion of multimodal neurological data. However, being able to determine the degree of similarity between datasets and appropriate order selection are crucial to the success of such techniques. The standard methods for calculating the order of multimodal data focus only on sources with the greatest individual energy and ignore relations across datasets. Additionally, these techniques as well as the most widely-used methods for determining the degree of similarity between datasets assume sufficient sample support and are not effective in the sample-poor regime. In this paper, we propose to jointly estimate the degree of similarity between datasets and their order when few samples are present using principal component analysis and canonical correlation analysis (PCA-CCA). By considering these two problems simultaneously, we are able to minimize the assumptions placed on the data and achieve superior performance in the sample-poor regime compared to traditional techniques. We apply PCA-CCA to the pairwise combinations of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), structural magnetic resonance imaging (sMRI), and electroencephalogram (EEG) data drawn from patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls while performing an auditory oddball task. The PCA-CCA results indicate that the fMRI and sMRI datasets are the most similar, whereas the sMRI and EEG datasets share the least similarity. We also demonstrate that the degree of similarity obtained by PCA-CCA is highly predictive of the degree of significance found for components generated using CCA.

Keywords: Multimodal fusion, PCA-CCA, fMRI, sMRI, EEG, Schizophrenia

1. Introduction

The collection of data from multiple modalities has become common in neurological studies, since different modalities are expected to provide complementary views of complicated systems, such as the study of brain activity [18]. Thus, full utilization of all common information forms the fundamental goal of performing a joint analysis on multimodal data. Since little is known about the intermodality relationships, it is important to minimize the underlying assumptions placed on the data and let the data “speak for itself.” Because of this fact and their ability to treat separate modalities in a symmetric manner, multivariate data-driven methods have proven to be quite popular for the fusion of multimodal neurological data, see e.g., [2, 7, 18]. To this end, canonical correlation analysis (CCA), which maximizes the correlation of sources across datasets [16], has proven to be an effective multivariate and data-driven fusion method, see e.g., [2, 11, 14, 34]. However, if the covariances are unknown and must be estimated from the samples, then CCA requires sufficient sample support [27]. This is particularly an issue when performing multimodal data fusion, since the number of samples, i.e. subjects, is typically much less than the dimension of the neurological data that is used. Thus, special attention must be paid both before performing an analysis, i.e., when determining the similarity between datasets and their order—the dimension of the signal subspace—and while performing the analysis itself.

In this paper, we define the similarity between two datasets as the number of common components that both datasets share, i.e., those components that are correlated across datasets, raising the issue of how to determine this number when the sample size is limited. One of the most popular exploratory techniques to estimate the number of common components between two datasets is based on the canonical correlation coefficients (CCCs) calculated using CCA [16] and defining a threshold for the level of the correlation, see e.g., [6, 15, 19, 23]. Other methods for estimating the number of common and distinctive sources include: orthogonal n-way partial least squares (OnPLS) [24], generalized singular value decomposition [4], and distinctive and common components with simultaneous-component analysis (DISCO-SCA) [37]. These methods all assume sufficient sample support and thus perform poorly when the number of samples is not significantly greater than the number of observations. CCA, in particular, suffers greatly in the sample-poor regime, where all CCCs are significantly misestimated [32] and the highest CCCs, usually of greatest interest, may saturate at 1 [27], meaning that they provide no information about the true relationship between the datasets.

Since multimodal data is often quite noisy and of high dimensionality, dimension reduction using principal component analysis (PCA) is a crucial preprocessing step for avoiding the problem of over-fitting in subsequent analyses. However, the effectiveness of PCA is intimately tied to the problem of order selection. For a single dataset, the most popular order selection methods define the order based on information theoretic criteria (ITC) [38], i.e, by using a function of the estimated eigenvalues of the data and the number of model parameters. These methods include: Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) [3], minimum description length (MDL) [29] or Bayesian information criterion (BIC) [31], and extensions of those methods, see e.g., [22]. Though these methods have found widespread application in multimodal fusion, they are not directly applicable for two major reasons. The first is that almost all of these eigenvalue-based methods, with the notable exception of [26], assume sufficient sample support. If this is not true, such as for multimodal fusion using CCA, where the number of subjects is much less than the dimension of the data, the performance of these methods deteriorates rapidly because the eigenvalues cannot be estimated accurately [26]. Additionally, these methods only report on the sources that have greatest energy in each dataset individually. Since we are interested in common components that are linked across datasets, the use of methods that focus solely on a single dataset is not a desirable solution to the question of order selection for multimodal fusion. This provides the incentive to consider the problems of determining the degree of similarity and order jointly. Though not used in the context of medical imaging, there are methods that consider these two problems jointly, see e.g., [17, 40], however these techniques are heuristic and will fail in the sample-poor regime [30].

In this paper, we discuss an effective method, PCA and CCA (PCA-CCA) along with the order selection rule from [32], for jointly determining the number of common sources for datasets and their order, in the sample-poor regime and demonstrate its importance as a preliminary step for multimodal fusion. To the best of our knowledge, this method is the only one that addresses the issues of common source detection and order selection for the sample-poor case encountered when using CCA for multimodal fusion. The versatility and high performance of this technique are first demonstrated through simulations. We then apply this new method to the pairwise combinations of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), structural magnetic resonance imaging (sMRI), and electroencephalogram (EEG) data drawn from 14 patients with schizophrenia and 22 healthy controls performing an auditory oddball (AOD) task and relate these results to the pairwise fusion results obtained using CCA. Through this application, we demonstrate a strong correlation between the number of common components estimated using PCA-CCA, i.e., the similarity between datasets, and number of statistically significant components estimated during the fusion analysis. This technique of investigating the pairwise combinations of datasets drawn from the same subjects provides unique insight into the degree of complementarity between related data of different modalities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theory

2.1.1. Traditional and Sample-poor Hypothesis Test

Let us assume that we have M independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) paired samples of x[1] ∈ ℝn and x[2] ∈ ℝm from the two-channel measurement model [32],

| (1) |

where s[k] ∈ ℝd+f, k = 1, 2, are zero-mean jointly Gaussian random vectors with cross-covariance matrix, Rs1s2 = E{s[1](s[2])T}, given by

where is the unknown standard deviation of signal component and ρi is the correlation coefficient between and . Thus, both s[1] and s[2] have d correlated signals and f uncorrelated signals. Without loss of generality, we assume the auto-covariance matrices of s[1] and s[2] to be diagonal. The noise terms n[1] and n[2] are independent of each other, independent of the signals, and zero-mean Gaussian with unknown covariance matrices. Additionally, without loss of generality we assume that A[1] and A[2] are of full column rank and, like the dimensions d and f, are fixed but unknown.

We collect the M sample pairs into data matrices and . When performing CCA when M < m+n, at least m+n−M of the sample canonical correlation coefficients, k̂i, i = 1, …, q, q = min(m, n), will be identically 1 regardless of the values of ρi and thus do not provide any information about the relationship between s[1] and s[2] [27]. Moreover, even in the case where M is greater, but not significantly greater, than m+n, the sample canonical correlations may significantly overestimate the population canonical correlations [32]. This result provides the incentive to estimate a suitable rank, r, in order to reduce the dimensions of X[1] and X[2], thus allowing accurate estimation of the number of correlated signals.

A classical way of estimating d is by assuming that the sources are drawn from a multivariate Gaussian distribution and applying a sequence of binary hypothesis tests [5, 21]. The test begins with s = 0 and compares the two hypotheses H0 : d = s and H1 : d > s. If the null hypothesis is rejected, then s is increased by one and the test is repeated, until either the null hypothesis is not rejected or s = q. This test is based on the Bartlett-Lawley statistic [5, 21], which is given by

| (2) |

and is asymptotically distributed under H0 as χ2 with (m−s)(n−s) degrees of freedom. The fact that the test statistic is distributed according to the χ2 distribution enables the determination of a threshold, T(s), to meet a given probability of false alarm, PFA, for the test. A major constraint of the traditional framework is the assumption of sufficient samples, i.e., that the k̂i’s are accurate estimates of the true ki’s, making it not applicable for the sample-poor regime.

As proposed in [32], the sample-poor version of the classical hypothesis test selects

| (3) |

where ℛ = {1, …, rmax}, 𝒮 = {0, …, r − 1}, and rmax = min(M/2, q) and the test statistic is

Note in the above expression that the estimated canonical correlations are functions of the reduced rank, r; if r is too big, then k̂i will be over-estimated, while if it is too small, then k̂i will be under-estimated [32].

By limiting the dimension through rmax, we can ensure that none of the estimated canonical correlations will saturate at 1. Note that to guarantee that the rank-reduced statistic under H0 is still asymptotically distributed as χ2 with (r−s)2 degrees of freedom, we must pick rmax “sufficiently” smaller than M/2. This is critical in order to compute the test threshold, T(s, r), for a given probability of false alarm. Based on our numerical simulations, a good value for rmax seems to be ⌊M/3⌋, where ⌊·⌋ is the floor function [32]. However, note that there is a certain degree of robustness of the results to the selection of the value of rmax observed in real data. The value for r that leads to d̂ in (3) is chosen as the PCA rank. Greater detail about the implementation of PCA-CCA to determine the order and similarity between multimodal datasets is found in Appendix B.

2.1.2. CCA for Multimodal Fusion

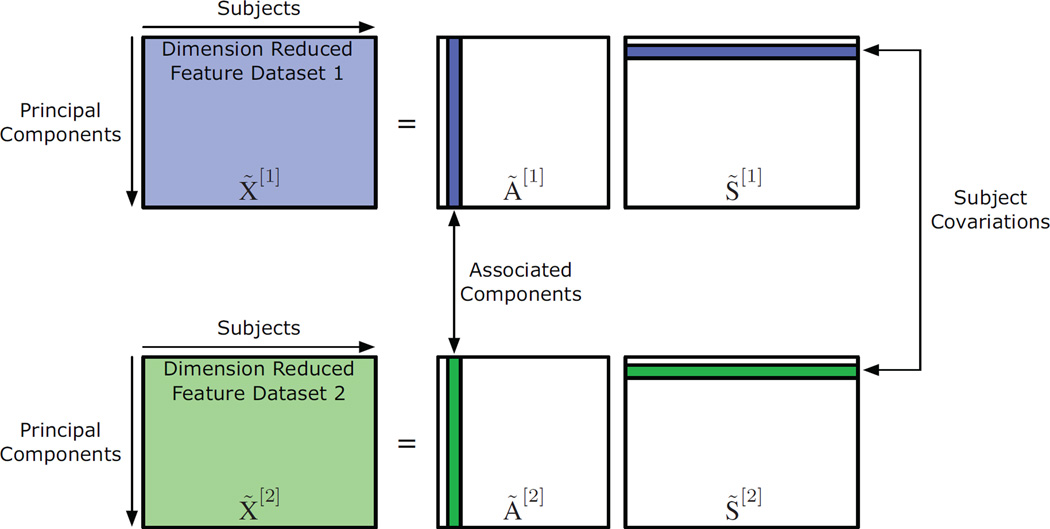

Due to the inherent dissimilarities between different modalities, direct fusion of multimodal data is difficult. Therefore, rather than jointly analyzing the multimodal datasets directly, it is often beneficial to reduce each modality to a feature, a lower-dimensional multivariate representation of the data, for each subject within the study. See Section 3.2 for greater detail about the features used in this study. This reduction enables the exploration of associations across feature sets through the analysis of variations across individuals [7, 9, 10]. Such an investigation of variations between subjects through fused features provides a natural way to explore associations across modalities, since it constructs a common dimension for datasets of otherwise different dimensionality [13, 35]. In addition, due to the dissimilarities between modalities, the subject covariations provide the dimension of coherence in multimodal fusion using CCA, since similarity between covariations across modalities is expected. Figure 1 depicts the model for multimodal fusion using CCA following spatial dimension reduction through PCA; the implementation of CCA for fusion is presented next.

Figure 1.

Generative model for multimodal fusion using CCA. Note that this model is obtained after spatial dimension reduction through PCA, i.e., X̃[1] and X̃[2] are both r × M matrices.

As explained in detail in Appendix B, we apply spatial dimension reduction through PCA, where the order, r, is selected using (3), to obtain dimension reduced feature datasets X̃[1] and X̃[2]. These datasets can be decomposed into the combination of subject covariations, S̃[1] and S̃[2], and associated components, Ã[1] and Ã[2], in the following manner,

| (4) |

By using this decomposition, the relationship across modalities can be evaluated based on the correlation of the subject covariations between the two modalities. We assume that the subject covariations are uncorrelated within each modality and are correlated with at most one subject covariation from the other modality. This enables the exploration of the associations across the modalities. Additionally, note the lack of a noise term in (4), which emphasizes that this analysis occurs following dimension reduction through PCA.

By exploiting the simple form of (4), we can use CCA to identify relations between the subject correlations [14]. CCA seeks to transform these two sets of data in order to maximize their correlation. This can be expressed in the following maximization problem, where in the first stage we obtain the first rows of P[1] and P[2], and , respectively,

| (5) |

where R̂XiXj = X̃[i] (X̃[j])T/M denotes a sample (cross-) covariance matrix and the operation corr(·, ·) refers to the sample correlation between the columns of the given matrices. Subsequent rows of P[1] and P[2] are estimated analogous to (5) with the additional constraint that

The estimated subject covariations are given by,

| (6) |

Greater detail about the implementation of CCA to perform source separation for multimodal data is found in Appendix B.

The rows of Ŝ[k] provide the loadings of each component across subjects. Thus, the p-th row of Ŝ[k], , represents the relative weights of the p-th source estimate, , for all subjects [2]. Since each dataset has been reduced to a feature for each subject, to look for differences in the expression of components between two groups, a two-sample t-test can be performed on the subject covariations, where one group is represented by the subject covariations from the patients with schizophrenia and the second by the subject covariations from the healthy controls [7, 9, 10]. This enables the detection of components that can differentiate patients from controls, providing insight into how brain disorders affect both neurological structure and function.

2.2. Simulation Setup

For real brain data, the ground truth, i.e., the true latent sources and subject covariations, is not available. Thus, in order to test the performance of PCA-CCA, we generate simulated data according to (1) and examine the probability of correctly estimating the true number of correlated components as the dimension of the datasets, m and n, increases from 10 to 10,000. We compare the performance of PCA-CCA to that of two classical ITC-based methods, AIC and MDL. These methods use the AIC and MDL framework in [38] in the PCA step to select r, and then use the AIC and MDL framework described in [33] to estimate the common order. For these simulations, we have M = 50 samples and d = 2 pairs of correlated components each with variance of 2 and correlation coefficients, ρ1 = 0.8 and ρ2 = 0.7. The number of uncorrelated components in s[1] and s[2], f, is 3. The variances of the uncorrelated signals and the white noise are both 1. These parameters were selected to align with properties of real neurological data. The entries of the mixing matrices A[k] are independently drawn from uniformly distributed random numbers between 0 and 1. Additionally, we consider two values, 0.001 and 0.005, for probability of false alarm, PFA. We have also used a minimum description length (MDL) based method, described in Appendix A, which does not require the selection of a probability of false alarm. The plots presented here are the average result of 1000 independent Monte-Carlo simulations, where, for each simulation, every method was used on the same data.

We repeated this simulation three times, changing only the distribution from which the sources, s[k], are drawn. In the first case, we consider sources drawn from a zero mean Gaussian distribution, which aligns with the form typically used in all derivations [5, 21, 22, 32, 38]. The subsequent case considers sources that are uniformly distributed with zero mean and the same variance as the previous case. Such sub-Gaussian or platykurtic sources are a good approximation of the subject covariations, since if there is a difference between the two groups then the distribution describing the subject covariations will be bi-modal and hence sub-Gaussian. Thus, the performance of PCA-CCA in this case is of great interest. The final case considered is where the sources are Laplacian distributed with zero mean and the same variance as the previous distributions. Due to the ability of the Laplacian distribution to provide good approximations of empirical fMRI source distributions [8, 25], studying the performance of PCA-CCA in this regime is of interest for the fusion of two fMRI datasets.

3. Results

3.1. Simulation Results

Figure 2 shows the high level of performance obtained using PCA-CCA together with the order selection rule in [32] for the three source distributions considered. The results indicate that PCA-CCA is robust to model mismatch in the latent source distribution. In all cases, the performance of PCA-CCA improves as the dimensionality of the datasets increases. The reason for this is that as the dimension of the datasets increases, the signal eigenvalues of , where Rsisi is the population covariance matrix of the correlated and uncorrelated signals, N = m = n is the dimension of the system, is the variance of the noise, and IN is a N-dimensional identity matrix, increase, whereas the noise eigenvalues remain unchanged. Thus, the per-component signal-to-noise ratio, i.e, the ratio of signal eigenvalue to the noise eigenvalue, increases as the dimension increases, thus improving the probability of detection. We see that the performance of the classical methods, AIC and MDL, deteriorates rapidly as the datasets become increasingly sample-poor because, in this regime, the eigenvalues cannot be estimated accurately. Finally, note that the MDL-based method consistently has the highest performance, indicating the benefits of its use over that of an arbitrary selection of a probability of false alarm.

Figure 2.

Probability of correctly detecting the number of common components versus the dimension of the datasets, m and n, when the latent sources are (a) Gaussian, (b) uniformly, and (c) Laplacian distributed. Note that for these simulations, m = n.

3.2. Auditory Task and Data Preprocessing

The fMRI (m = 60, 261), EEG (m = 451), and sMRI (m = 306, 626) data used in this study were obtained from 22 healthy controls and 14 patients with schizophrenia, meaning that M is 36. The first two modalities, fMRI and EEG, were obtained individually while the subjects listened to three different types of auditory stimuli: standard (500 Hz occurring with probability 0.80), novel (nonrepeating random digital sounds with probability 0.10), and target (1 kHz with probability 0.10, to which a button press was required). These two modalities provide complementary views of functional neural activity, with fMRI observing the changes in blood-oxygenation levels and EEG measuring electrical activity of neurons through the scalp. The third modality, sMRI, provides structural information about the brain by describing three main tissue types: gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid. Including this final modality permits the exploration of the degree to which neural structure underlies brain function. For more information on the task and the preprocessing of the data, see [14].

FMRI

fMRI preprocessing steps include: slice timing correction to account for the sequential acquisition of the slices, registration to correct subject motion in the scanner, spatial filtering to reduce noise, and spatial normalization to allow comparisons of fMRI data across different individuals. The features used for fMRI data are task-related spatial activity maps calculated by the general linear regression approach [14].

EEG

EEG preprocessing steps include: amplifying the detected signals to correct the minor observed changes and then digitizing the resultant signals. The extracted features, event-related-potentials (ERPs), are formed by averaging epochs (recording periods) of a single channel of the EEG data time matched to the sensory stimulus of the AOD task [14]. For this study, we used the channel corresponding to the midline central (Cz) position because it was the best single channel for the detection of both anterior and posterior sources for the task.

SMRI

sMRI preprocessing steps include: bias field corrections, which correct for intensity changes caused by radio frequency or main magnetic field inhomogeneities, spatial filtering to reduce noise, and spatial normalization to allow comparisons of brains across different individuals. We use non-modulated probabilistically segmented gray matter images as the sMRI features for this fusion study [14].

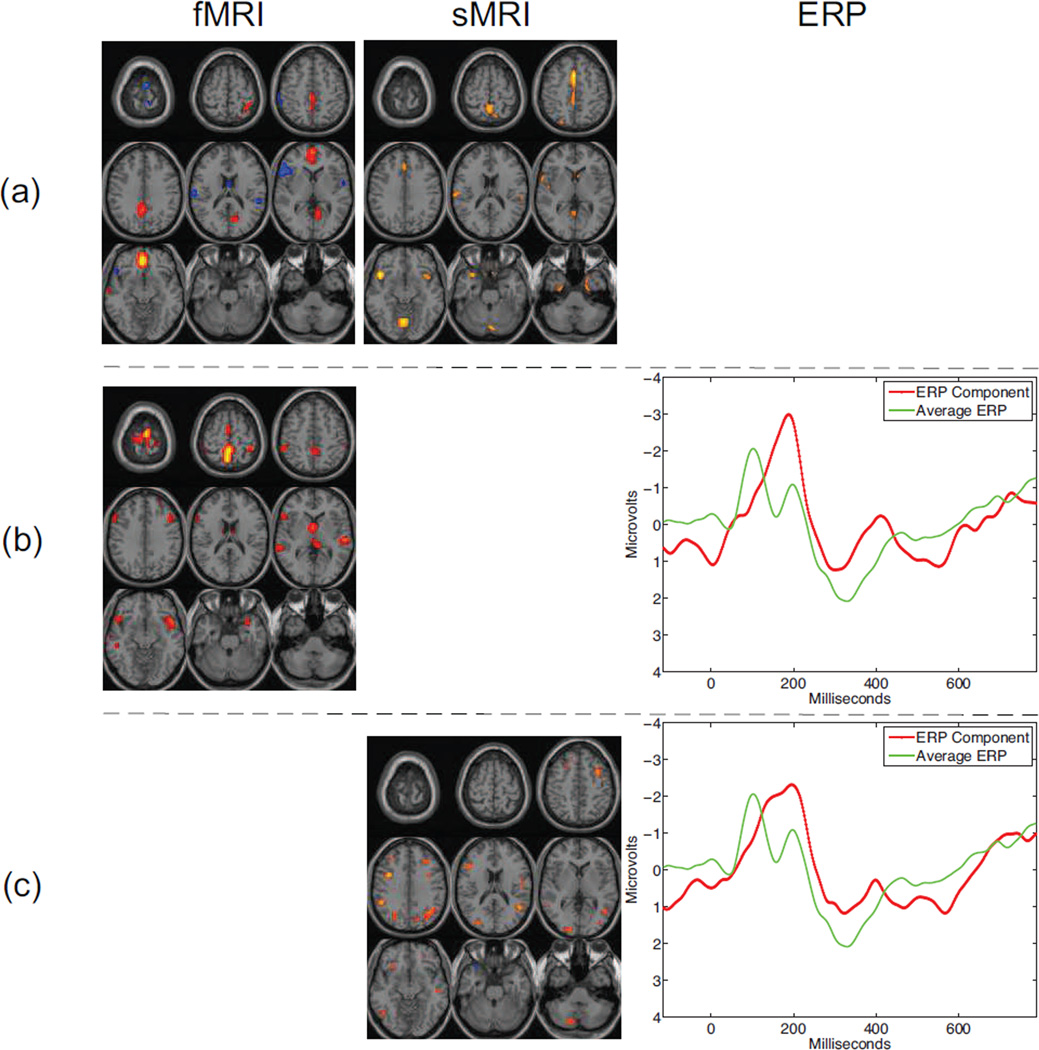

3.3. AOD Fusion Results

The fusion results using CCA are depicted in Figure 3. These components are those that were found to be both biologically meaningful and statistically significant, i.e., they had activations corresponding to biologically meaningful areas and p-values in terms of group differences smaller than 0.05. Biological meaning is assessed based on prior information about the spatial and temporal properties of the components. For fMRI and sMRI components, smooth and focal regions are expected, while ERP components should display a smooth response with peaks corresponding to those in the group response. When using the fMRI and sMRI data together, one component is found. This component corresponds to frontal activation in the fMRI section and motor activation in the sMRI. When the fMRI and ERP data are used in the analysis, a single one component is found that is both statistically significant and physically meaningful. This component corresponds to sensory-motor and auditory activation in the fMRI part and corresponding N2\P3 complex in the ERP. These regions correspond to areas that have been previously noted as affected in schizophrenia. We see a similar N2\P3 complex in the ERP component generated using the sMRI and ERP data. Note that these discriminative components can be leveraged to classify a new subject as either a patient with schizophrenia or a healthy control [28]. By regressing the discriminative components onto the new subject’s feature data, we obtain a set of subject covarations that can be classified using either k-means or a support vector machine.

Figure 3.

Meaningful and statistically significant components generated using CCA with pairwise combinations of the three modalities. The uncorrected significance (p-values) for the components are (a) 0.027 for the fMRI-sMRI component, (b) 0.003 for the fMRI-ERP component, and (c) 0.018 for the sMRI-ERP component. All spatial maps are Z-maps threshold at Z=3.5.

Using PCA-CCA and the MDL criterion described in Appendix A, we can estimate the number of common components for each of the pairwise combinations of the fMRI, sMRI, and ERP data. This estimation of the number of common components allows us to measure the degree of similarity between the datasets in a meaningful way, by defining greater similarity in terms of a greater number of common components. The results of this analysis are displayed in Table 1, where we also show the number of statistically significant components found for each combination of modalities. Components are declared significant if they pass a two-sample t-test run on the rows of the estimated subject covariations, Ŝ[k], k = 1, 2, calculated using CCA. We see that the fMRI and sMRI data have the greatest degree of similarity since they share the greatest number of common components estimated using PCA-CCA. This result makes sense since both modalities are MRI data of spatial nature and thus they would be expected to have a greater degree of similarity. The result also corresponds to the number of significant components found after performing fusion using CCA. Since the fMRI-sMRI combination has the greatest number of significant components, there is a greater number of chances of finding common significant components. This explains why we observe that greatest number of meaningful components using the combination of fMRI and sMRI. Using PCA-CCA, we found that the combination of fMRI and ERP data produced the second greatest number of common components. This result again makes sense since both the fMRI and ERP data describe functional changes in the brain, so they exhibit a fairly large degree of similarity. The result correlates to the results obtained in terms of number of significant components found after performing fusion using CCA on the modality pair of fMRI-ERP. The least similar modalities are the sMRI and ERP. This result is confirmed by the results obtained using PCA-CCA, since the sMRI-ERP combination produced the fewest number of common components. This result makes sense since the sMRI data is structural whereas the ERP data is functional. Thus, using PCA-CCA, we can measure the degree of similarity between datasets and the results can be predictive of the fusion results using CCA.

Table 1.

Number of significant components at two p-values, PCA-CCA estimated common components, d, and estimated order, r, for the three pairwise combinations of modalities. Statistical significance is assessed by a two-sample t-test run on the rows of the estimated subject covariations, Ŝ[k], k = 1, 2, calculated using CCA.

| fMRI-sMRI | fMRI-ERP | sMRI-ERP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of significant components, p = 0.05 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Number of significant components, p = 0.1 | 5 | 4 | 2 |

| Number of common components using PCA-CCA | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Estimated order using PCA-CCA | 17 | 17 | 12 |

4. Discussion

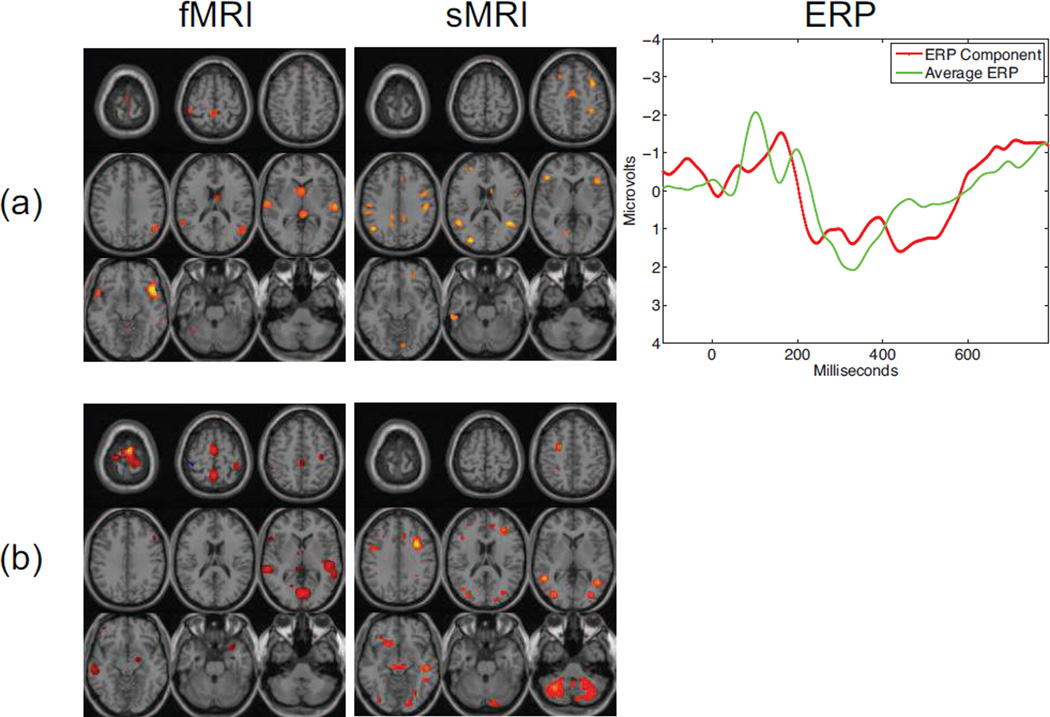

The successful application of PCA-CCA to determine the degree of similarity between pairwise combinations of multimodal datasets naturally leads to the issue of extensions beyond two datasets. For fusion using CCA, the straightforward extension is the use of multiset CCA (MCCA) [20], with one of the five cost functions selected. This technique has been successfully applied to the fusion of three mulimodal datasets, see e.g., [13, 36]. The results of the application of MCCA, using only the generalized variance (GENVAR) cost for brevity, to the fMRI, sMRI, and ERP data in this study is displayed in Figure 4. As expected, we can see a great degree of correlation between the CCA results and those achieved using MCCA. The motor, auditory, and visual activation in the second component bear striking resemblance to those of the fMRI-ERP component. In addition, the N2\P3 activation observed in the ERP components that are generated using CCA is similar to that of the ERP component generated using MCCA.

Figure 4.

Meaningful and statistically significant components generated using MCCA with GENVAR. The uncorrected significance (p-values) for the components are (a) 0.014 for the first component and (b) 0.018 for the second component. All spatial maps are Z-maps thesholded at Z=3.5.

However, a similar extension of PCA-CCA to more than two datasets remains an open problem. This is due to the fact that in the case of two datasets the number of non-zero canonical correlations defines the degree of correlation between the two sets. However, for more than two datasets, the canonical correlations cannot be used to define the number of correlated components.

To understand the reason for this, consider the case where we have three datasets with four independent signals in each. Only the first two sources in dataset 1 are correlated with the first two sources in dataset 2. Similarly, only the first and third sources in dataset 2 are correlated with the first and third sources in dataset 3. Finally, only the first and fourth sources in dataset 1 are correlated with the first and fourth sources in dataset 3. In this example, there are two correlated signals in each pair of datasets but there is just one signal, i.e., the first signal in each dataset that is correlated across all the datasets. In order to identify this common signal, we expect a non-zero correlation between all three pairwise combinations of the first signal components of the three datasets only. However, MCCA would generate non-zero correlations for all pairwise combinations of the four signals from all datasets, regardless of the cost used, indicating that all of the components are common to all datasets, which is not the case.

Though a true multiset extension of PCA-CCA is preferable, an interim solution is the following heuristic method, which can estimate the number of correlated components among all three datasets. Note that this method can be extended to an arbitrary number of datasets, though it is only presented for three datasets here.

For datasets x[1] and x[2], by applying the PCA-CCA approach, we can estimate the number of correlated signals between the first and second datasets, d̂[1,2], and the optimal rank, r[1,2], that PCA should keep for x[1] and x[2]. With these estimates, the canonical sources, and , associated with the d̂[1,2] largest canonical correlations may be obtained from the r[1,2]-approximation of x[1] and x[2], respectively. The above procedure for x[1] and x[2] can be analogously applied for the pairwise combinations x[2] and x[3], as well as x[1] and x[3]. Due to the fact that the canonical source, e.g., some row in , is equal to the corresponding original source, e.g., some row in s[1], up to a scaling factor, we can find three canonical sources, whose cross-correlation matrices, , are all of rank d, where d is the number of common signals among three datasets. Then, the ITC-based detection scheme described in [39] can be used. Applying this method to the fMRI, sMRI, and ERP data, one common signal can be identified. The result using this method corresponds to what is observed with MCCA, where there is only one component that is common to all three modalities.

The collection of multimodal data has become increasingly common in medical studies, raising the issue of how best to combine data that are, fundamentally, different. In this paper, we proposed the use of PCA-CCA and the order selection rule of [32] to determine the degree of similarity between multimodal neurological data. The results using PCA-CCA indicate that this method can not only measure the degree of similarity between dissimilar datasets but also provides an accurate prediction of the significance of components generated by CCA. This predictive capability of PCA-CCA enables the determination of meaningful combinations of modalities prior to analysis. There are several possible directions available for future consideration.

A true multiset extension of PCA-CCA. Though the proposed heuristic method may be used for three datasets, it is not effective for detecting the number of common components in a large number of datasets. A possible solution may lie in tensor decompositions, which have recently been applied to the processing of medical data, see e.g., [12].

An extension of PCA-CCA enabling the detection of components based on higher-order dependence. The limitation of PCA-CCA to detect similar components based solely on correlation has obvious limitations when information about higher-order dependence is available. Exploring the possibility of kernelizing PCA-CCA or using independent vector analysis (IVA) could prove fruitful in exploiting this information [1].

Application of PCA-CCA to multitask data drawn from the same modality. In the same way that PCA-CCA can be used to determine the similarity between modalities, PCA-CCA can be applied to multi-set data, i.e., data of the same type such as multi-task data, in order to determine the degree of similarity between different datasets.

Highlights.

-

►

Signal subspace or order estimation is crucial for studies using neurological data.

-

►

We use PCA-CCA to find the order and quantify similarity for multimodal datasets.

-

►

PCA-CCA has high performance in the sample-poor regime faced in multimodal fusion.

-

►

Similarity between multimodal data is predictive of data fusion results with CCA.

Acknowledgments

The work of Y. Levin-Schwartz, T. Adalı, and V. D. Calhoun was supported by the grants NIH-NIBIB R01 EB 005846 and NSF-IIS 1017718. The work of Y. Song and P. J. Schreier was supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) under grant SCHR 1384 3/1.

Appendix A

A fundamental issue with hypothesis tests is the need to set a probability of false alarm, which determines the test threshold. For different problems, the ideal value for this probability of false alarm and thus the threshold changes, and cannot, in general, be determined for real data. This provides the incentive to use a threshold that is based on ITC. The general MDL expression for detecting the number of correlated components in a two channel model is given by [33]

| (7) |

where the number of correlated components is determined by the value of s which minimizes (7).

We can modify (7) in a similar manner as (2) to account for the PCA step, resulting in the final MDL criterion [32]

| (8) |

The decision rule (3) is thus replaced with

| (9) |

and, because of its desirable performance, as demonstrated in the simulation results, is used to compute the number of common components for the multimodal data considered in this study.

Appendix B

In this section, we describe the pipeline developed in this paper to fuse multimodal data. Consider two sets of multimodal feature data X[1] and X[2] gathered from the same M subjects, whose dimensions are m × M and n × M. In this study, these datasets could be any pairwise combination of the fMRI, sMRI, and EEG data.

The first stage in the pipeline is the calculation of the joint order and degree of similarity between X[1] and X[2]. This is done by performing PCA-CCA on the two datasets using the decision rule specified by (9) and a value of rmax specified in Section 2.1.1. This preliminary analysis produces the joint order of X[1] and X[2], r, as well as the degree of similarity between X[1] and X[2], d. This value of r is used as a preprocessing step for the second stage, where multimodal data fusion is performed using CCA.

Prior to performing data fusion using CCA, dimension reduction is first performed using PCA, with the order specified by r, on each dataset separately, in order to reduce X[1] and X[2] to X̃[1] and X̃[2], respectively, such that

| (10) |

where F[k] are data reduction matrices and are equal to the eigenvectors corresponding to the highest r eigenvalues of the sample covariance matrix of X[k]. Note that both X̃[1] and X̃[2] have the same dimensionality, i.e, r × M. Next, CCA is performed on X̃[1] and X̃[2], producing estimated subject covariations, Ŝ[1] and Ŝ[2], according to (6). Then using (4), the estimated dimension-reduced sources, Ã̂[1] and Ã̂[2], are found. Finally, the full estimated sources, Â[1] and Â[2], are found through back-reconstruction of Ã̂[1] and Ã̂[2] using

| (11) |

Note that when fusing three datasets, the PCA-CCA stage is skipped and the joint order is specified by the mean order found in each of the pairwise combinations of modalities. Additionally, when fusing three datasets, the CCA step is replaced with MCCA using the GENVAR cost [20].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Adalı T, Anderson M, Fu G-S. Diversity in independent component and vector analyses: Identifiability, algorithms, and applications in medical imaging. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine. 2014 May;31(3):18–33. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adalı T, Levin-Schwartz Y, Calhoun VD. Multi-modal data fusion using source separation: Two effective models based on ICA and IVA and their properties. Proceedings of the IEEE. 2015;103(9):1478–1493. doi: 10.1109/JPROC.2015.2461624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akaike H. Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle; Proc. 2nd Int. Symp. on Information Theory; 1973. pp. 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alter O, Brown PO, Botstein D. Generalized singular value decomposition for comparative analysis of genome-scale expression data sets of two different organisms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100(6):3351–3356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530258100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartlett MS. The statistical significance of canonical correlations. Biometrika. 1941;32(1):29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bush JP, Melamed BG, Sheras PL, Greenbaum PE. Mother–child patterns of coping with anticipatory medical stress. Health Psychology. 1986;5(2):137. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.5.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calhoun VD, Adalı T. Feature-based fusion of medical imaging data. IEEE Trans. Inf. Technol. Biomed. 2009 Sep;13(5):711–720. doi: 10.1109/TITB.2008.923773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calhoun VD, Adalı T. Multisubject independent component analysis of fMRI: A decade of intrinsic networks, default mode, and neurodiagnostic discovery. IEEE Reviews in Biomedical Engineering. 2012;5:60–73. doi: 10.1109/RBME.2012.2211076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calhoun VD, Adalı T, Pearlson G, Kiehl K. Neuronal chronometry of target detection: Fusion of hemodynamic and event related potential data. NeuroImage. 2006;30:544–553. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calhoun VD, Allen E. Extracting intrinsic functional networks with feature-based group independent component analysis. Psychometrika. 2013;78(2):243–259. doi: 10.1007/s11336-012-9291-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen X, Wang Z, McKeown M. A three-step multimodal analysis framework for modeling corticomuscular activity with application to parkinson’s disease. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics. 2014 Jul;18(4):1232–1241. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2013.2284480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cichocki A, Zdunek R, Phan AH, Amari S-I. Nonnegative Matrix and Tensor Factorizations: Applications to Exploratory Multi-way Data Analysis and Blind Source Separation. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Correa N, Adalı T, Li Y-O, Calhoun VD. Canonical correlation analysis for data fusion and group inferences. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine. 2010;27(4):39–50. doi: 10.1109/MSP.2010.936725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Correa NM, Li Y-O, Adalı T, Calhoun VD. Canonical correlation analysis for feature-based fusion of biomedical imaging modalities and its application to detection of associative networks in schizophrenia. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Signal Processing. 2008 Dec;2(6):998–1007. doi: 10.1109/JSTSP.2008.2008265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoefs JC. Serum protein concentration and portal pressure determine the ascitic fluid protein concentration in patients with chronic liver disease. The Journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 1983;102(2):260–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hotelling H. Relations between two sets of variates. Biometrika. 1936;28(3/4):321–377. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hwang H, Jung K, Takane Y, Woodward TS. A unified approach to multiple-set canonical correlation analysis and principal components analysis. The British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 2013;66(2):308–321. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8317.2012.02052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.James AP, Dasarathy BV. Medical image fusion: A survey of the state of the art. Information Fusion. 2014;19:4–19. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennedy GJ, Kelman HR, Thomas C. The emergence of depressive symptoms in late life: the importance of declining health and increasing disability. Journal of community health. 1990;15(2):93–104. doi: 10.1007/BF01321314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kettering J. Canonical analysis of several sets of variables. Biometrika. 1971;58:433–451. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawley DN. Tests of significance in canonical analysis. Biometrika. 1959;46(1/2):59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X-L, Adalı T, Anderson M. Noncircular principal component analysis and its application to model selection. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2011 Oct;59(10):4516–4528. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin Z, Zhang C, Wu W, Gao X. Frequency recognition based on canonical correlation analysis for SSVEP-based BCIs. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2006;53(12):2610–2614. doi: 10.1109/tbme.2006.886577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Löfstedt T, Trygg J. OnPLS - a novel multiblock method for the modelling of predictive and orthogonal variation. Journal of Chemometrics. 2011;25(8):441–455. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mckeown MJ, Makeig S, Brown GG, Jung T-P, Kindermann SS, Bell AJ, Sejnowski TJ. Analysis of fMRI Data by Blind Separation Into Independent Spatial Components. Human Brain Mapping. 1998;6:160–188. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1998)6:3<160::AID-HBM5>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nadakuditi RR, Edelman A. Sample eigenvalue based detection of high-dimensional signals in white noise using relatively few samples. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing. 2008;56(7):2625–2638. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pezeshki A, Scharf LL, Azimi-Sadjadi MR, Lundberg M. Empirical canonical correlation analysis in subspaces. 2004 Conference Record of the Thirty-Eighth Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems and Computers. 2004 Nov;1:994–997. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramezani M, Abolmaesumi P, Marble K, Trang H, Johnsrude I. Fusion analysis of functional MRI data for classification of individuals based on patterns of activation. Brain Imaging and Behavior. 2014;9(2):149–161. doi: 10.1007/s11682-014-9292-1. URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11682-014-9292-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rissanen J. Modeling by shortest data description. Automatica. 1978;14:465–471. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roseveare NJ, Schreier PJ. Model-order selection for analyzing correlation between two data sets using CCA with PCA preprocessing; 2015 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2015. pp. 5684–5687. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann. Stat. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song Y, Schreier PJ, Roseveare NJ. Determining the number of correlated signals between two data sets using PCA-CCA when sample support is extremely small; 2015 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2015. pp. 3452–3456. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stoica P, Wong KM, Wu Q. On a nonparametric detection method for array signal processing in correlated noise fields. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing. 1996 Apr;44(4):1030–1032. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sui J, Adalı T, Pearlson G, Yang H, Sponheim SR, White T, Calhoun VD. A CCA+ICA based model for multi-task brain imaging data fusion and its application to schizophrenia. NeuroImage. 2010;51:123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.01.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sui J, Adalı T, Yu Q, Chen J, Calhoun VD. A review of multivariate methods for multimodal fusion of brain imaging data. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2012;204(1):68–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sui J, He H, Pearlson GD, Adalı T, Kiehl KA, Yu Q, Clark VP, Castro E, White T, Mueller BA, Ho BC, Andreasen NC, Calhoun VD. Three-way (n-way) fusion of brain imaging data based on mCCA+jICA and its application to discriminating schizophrenia. NeuroImage. 2013;66:119–132. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Deun K, Smilde A, Thorrez L, Kiers H, van Mechelen I. Identifying common and distinctive processes underlying multiset data. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems. 2013;129(0):40–51. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wax M, Kailath T. Detection of signals by information theoretic criteria. IEEE Trans. Acoust., Speech and Signal Process. 1985 Apr;33(2):387–392. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu Y, Tam K-W, Li F. Determination of number of sources with multiple arrays in correlated noise fields. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing. 2002 Jun;50(6):1257–1260. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zwick WR, Velicer WF. Comparison of five rules for determining the number of components to retain. Psychological bulletin. 1986;99(3):432–442. [Google Scholar]