Abstract

Objective

We investigate whether psoas or paraspinous muscle area measured on a single L4–5 image is a useful measure of whole lean body mass compared to dedicated mid-thigh magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Design

Observational study.

Setting

Outpatient dialysis units and a research clinic.

Subjects

105 adult participants on maintenance hemodialysis. No control group was used.

Exposure variables

Psoas muscle area, paraspinous muscle area, and mid-thigh muscle area (MTMA) were measured by MRI.

Main outcome measure

Lean body mass was measured by dual-energy absorptiometry (DEXA) scan.

Results

In separate multivariable linear regression models, psoas, paraspinous, and mid-thigh muscle area were associated with increase in lean body mass. In separate multivariate logistic regression models, c-statistics for diagnosis of sarcopenia (defined as < 25th percentile of lean body mass) were 0.69 for paraspinous muscle area, 0.81 for psoas muscle area, and 0.89 for mid-thigh muscle area. With sarcopenia defined as < 10th percentile of lean body mass, the corresponding c-statistics were 0.71, 0.92, and 0.94.

Conclusions

We conclude that psoas muscle area provides a good measure of whole body muscle mass, better than paraspinous muscle area but slightly inferior to mid thigh measurement. Hence, in body composition studies a single axial MR image at the L4–L5 level can be used to provide information on both fat and muscle and may eliminate the need for time-consuming measurement of muscle area in the thigh.

Keywords: Magnetic resonance imaging, Lean body mass, Paraspinous muscle area, Psoas muscle area, Muscle mass in hemodialysis patients, Protein-energy wasting

Introduction

Quantification of lean body mass (LBM) is important for research in nutrition and exercise physiology. Total body protein measurement performed by rapid in vivo neutron activation analysis (1) is considered the gold standard for measurement of LBM but is technically cumbersome. Other techniques used to estimate muscle mass in dialysis patients include anthropometry, creatinine kinetics, bio-impedance analysis, dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), and imaging techniques (2). Each of these methods has limitations. Anthropometry provides only a crude estimate of muscle mass. Measurement of muscle mass by serum creatinine kinetics is subject to assumptions about extra-renal creatinine excretion and is affected by factors such as dietary intake of animal skeletal muscle (3, 4). Measurement of non-fat tissue mass with bio-impedance analysis and DEXA can be biased by hydration status (5) and edema (6). Furthermore, DEXA involves ionizing radiation.

Measurement of muscle mass has been performed with cross-section imaging including CT (7) and MRI (8). MRI is advantageous for measurement of muscle mass since it involves no ionizing radiation and therefore does not theoretically increase the risk of cancer as does CT. We have previously used a three-point Dixon MRI fat/water separation method (9) and a soft tissue MRI signal model (10) for lean muscle quantification in the legs (11, 12).

Measurement of intra-abdominal fat volume is especially important in body composition studies, since visceral fat is metabolically more active than subcutaneous fat. Measurement of both muscle and fat compartments for body composition with MRI usually requires imaging of the thigh to measure thigh muscle area and a separate abdominal imaging sequence to measure intra-abdominal fat area. This is cumbersome as this requires different positioning of the patient and the MRI signal reception coils. For this reason we sought to determine whether measurement of psoas or paraspinous muscle area at the same L4–L5 axial slice used for abdominal fat measurement will provide a useful measure of whole body muscle mass. If so, a single MRI section at L4–L5 level could provide clinically relevant information on both muscle and fat compartments in body composition studies.

Subjects and Methods

Study population and study procedures

Protein Intake, Cardiovascular disease and Nutrition In stage V CKD (PICNIC) is a prospective observational study (publicly registered as NCT00566670 at clinicaltrials.gov) examining the impact of nutrient intake on vascular health, body composition and physical functioning in adult (≥18 years) patients on maintenance hemodialysis (MHD) for at least 3 months at the University of Utah outpatient dialysis units. This study is HIPAA compliant and IRB approved, and all subjects have given written informed consent.

The current study included 105 MHD patients at the University of Utah (N=83) and Vanderbilt University (N=22) who underwent, on a non-dialysis day, an MRI examination of the thighs for measurement of mid-thigh muscle area and examination of the abdomen at L4–5 level for measurement of intra-abdominal fat area following a standardized protocol. As water is the primary constituent of muscle, if interstitial edema is present, muscle mass could be overestimated by MRI scan. Trained study coordinators examined each patient for presence of pedal edema the week before the scheduled MRI scan. All of the participants also underwent a dual-energy absorptiometry (DEXA) scan on a non-dialysis day for measurement of LBM. Standardized questionnaire was used to obtain demographic characteristics, medical history, and past/current smoking/alcohol use. Height was measured to the nearest centimeter using a metal rule (200 cm, aluminum model #733; Radiation Products Design, Buffalo, NY) attached to a wall and a standard triangular headboard. The average of three postdialysis weights the week before the study visit was obtained from the dialysis records. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as postdialysis weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Serum albumin measured as part of standard of care monthly dialysis labs was used as a marker of nutrition.

MRI protocol

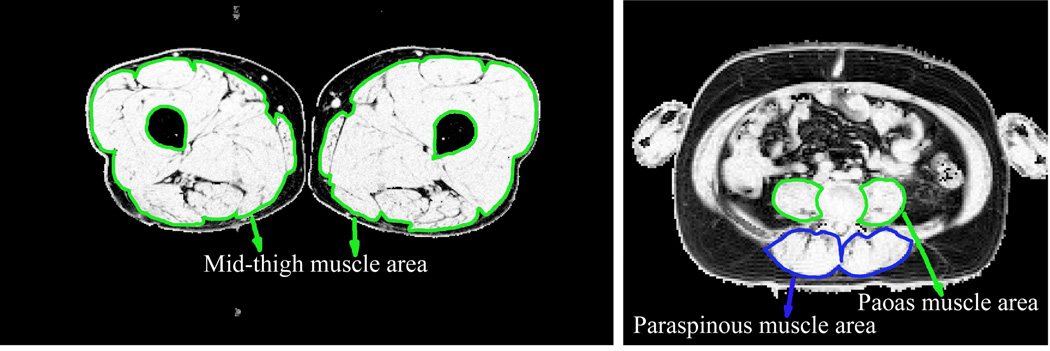

The detailed MRI protocol is described in the Supplemental Appendix. Images of the legs were acquired with a 3.0 Tesla Siemens Trio system at the University of Utah or with a 3.0 Tesla Philips Achieva system at Vanderbilt University using the spine coil incorporated in the scan table posteriorly combined with the torso array coil anteriorly. The midpoint of the thigh was determined on the coronal images as the point equidistant from the top of the femoral head and the bottom of the femoral condyles. Multislice axial imaging was then performed with the three-point Dixon method, with multislice acquisition centered at the midpoint of the thigh. A single axial image was obtained at the L4–5 level for estimation of psoas and paraspinous muscle cross-section. Images were created showing the percent volume fraction of fat and non-fat tissue in each pixel. Representative images of the legs and abdomen are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Typical non-fat volume fraction images of mid-thigh and abdomen at the L4–5 level. Images are calculated from 3-point Dixon images and a tissue signal model. Lean muscle cross-section was calculated by defining a region of interest around the muscles and summing the non-fat volume fraction over the region of interest. Effective muscle cross-sectional area is the sum of the non-fat volume fraction values (each ranging from 0.0 to 1.0) times the area of a single pixel.

DEXA protocol

A Hologic Discovery DEXA scanner with software version 12.3 was used to measure body composition at the University of Utah. A General Electric Lunar iDEXA machine with GE Lunar body composition software was used at Vanderbilt University. Participants were dressed in a gown or T-shirt and scrub pants, and lay supine in the center of the DEXA table. Participants were instructed to relax, breathe and hold still for the scan, which took approximately 2.5 minutes to acquire. The participant’s feet were rotated 45 degrees medially, and surgical tape was used to hold the feet in place for the duration of the scan. Participants who were unable to remain still for the duration of the scan were re-scanned. Note was made of any items that could cause artifact on the scan but were non-removable (such as IV ports, pacemakers, etc.). Trained technicians analyzed each scan using the manufacturer’s recommended analysis guidelines to measure LBM.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics are described for subgroups defined by median values of the psoas and mid-thigh muscle areas. Results are presented by mean and standard deviation or medians and 25th and 75th percentiles for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. Continuous variables between the subgroups were compared by t-test and categorical variables by chi-square test.

Pearson correlation coefficients and scatter plots with fit lines were applied to examine the pairwise relationships between psoas, paraspinous, and mid-thigh muscle area. These were also used to examine the pairwise relationships between the three muscle areas with DEXA measurement of LBM. Separate linear regression analyses were performed to relate each standard deviation (SD) increase in mid-thigh muscle area, psoas muscle area, and paraspinous muscle area with LBM and serum albumin with or without adjustment for age, gender, race and duration of end-stage renal disease. In separate logistic regression models of sarcopenia (muscle wasting) defined as either < 25th percentile or < 10th percentile of DEXA measured LBM, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses were used to examine c-statistics (area under the curve) predicted by mid-thigh, psoas and paraspinous muscle areas adjusted for the same covariates above. Sensitivity analyses were performed by repeating the above models in those without pedal edema (n=85) as well as in the subgroup excluding Vanderbilt participants (n=83). Analyses were performed with STATA 12.

Results

The study population consisted of 105 subjects on maintenance hemodialysis. Participants underwent MRI of the thighs for measurement of mid-thigh muscle cross-section area, MRI of the abdomen at L4–5 for measurement of psoas and paraspinous muscle areas, and DEXA scan to measure whole-body lean mass. Baseline characteristics by the psoas and mid-thigh muscle area groups are summarized in Table 1. In general, younger age, male gender and African-American race were associated with higher muscle area.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics by mid-thigh and psoas muscle groups (N = 105)*

| Mid-thigh muscle area | Psoas muscle area | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 99.8 (cm2) | ≥ 99.8 (cm2) | <9.9 (cm2) | ≥ 9.9 (cm2) | |

| (N = 53)* | (N = 52)* | (N = 53)* | (N = 52)* | |

| Mid-thigh Muscle area, (cm2) Δ, £ | 83.1 ± 12.5 | 128.9 ± 19.2 | 84.9 ± 14.5 | 127.1 ± 21.8 |

| Psoas Muscle Area, (cm2) Δ, £ | 7.9 ± 1.8 | 13.0 ± 3.2 | 7.6 ± 1.5 | 13.3 ± 2.8 |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, (year) # | 54.3 ± 17.8 | 47.5 ± 13.6 | 53.2 ± 18.3 | 48.7 ± 13.4 |

| Men, (%) Δ, £ | 39.6 | 82.4 | 32.1 | 90.2 |

| African American, (%) # | 15.1 | 32.7 | 17.0 | 30.8 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| ESRD duration, (year) | 2.7 (0.8,4.4) | 2.0 (0.9,4.7) | 2.7 (0.8,4.4) | 2.0 (0.9,4.7) |

| Fistula vascular access, (%) | 64.7 | 73.1 | 66.7 | 71.2 |

| Atherosclerosis (%) | 41.5 | 32.7 | 43.4 | 30.8 |

| Congestive Heart Failure (%) | 17.0 | 20.0 | 18.9 | 18.0 |

| Diabetes, (%) | 41.5 | 44.0 | 39.6 | 46.0 |

| Smoking, (%) | 47.2 | 48.1 | 45.3 | 50.0 |

| Alcohol, (%) | 49.1 | 59.6 | 45.3 | 63.5 |

| Pedal Edema, (%) | 15.4 | 21.2 | 19.2 | 17.3 |

| Nutritional characteristics | ||||

| Waist circumference, (cm) Δ, $ | 94 ± 16 | 104 ± 14 | 95 ± 16 | 103 ± 14 |

| Intra- abdominal fat area, (cm2) | 116 ± 77 | 138 ± 71 | 123 ± 82 | 130 ± 67 |

| Body Mass Index, (kg/m2) #,$ | 26.5 ± 6.7 | 29.9 ± 5.8 | 27.1 ± 7.0 | 29.3 ± 5.7 |

| Lean body mass (kg) Δ, £ | 47.0 ± 8.0 | 61.8 ± 7.7 | 47.0 ± 7.7 | 61.9 ± 7.8 |

| Serum albumin, (g/dL) #,$ | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 4.1 ± 0.4 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 4.1 ± 0.3 |

means ± SDs, medians (interquartile range), or proportions are presented p≥0.05 except as specified below

p<0.05 for Mid-thigh muscle area,

p<0.001 for Mid-thigh muscle area

p<0.05 for Psoas muscle area,

p<0.001 for Psoas muscle area

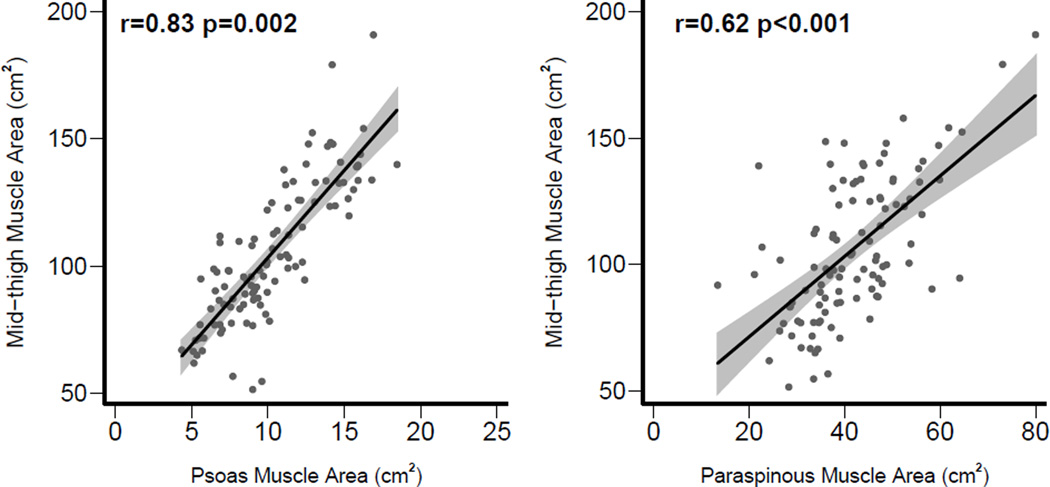

As shown in Figure 2, there was a strong correlation between mid-thigh and psoas muscle areas (r = 0.83, p < 0.001) and moderate correlation between mid-thigh and paraspinous muscle areas (r = 0.62, p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Correlation of mid-thigh muscle area with psoas and paraspinous muscle areas.

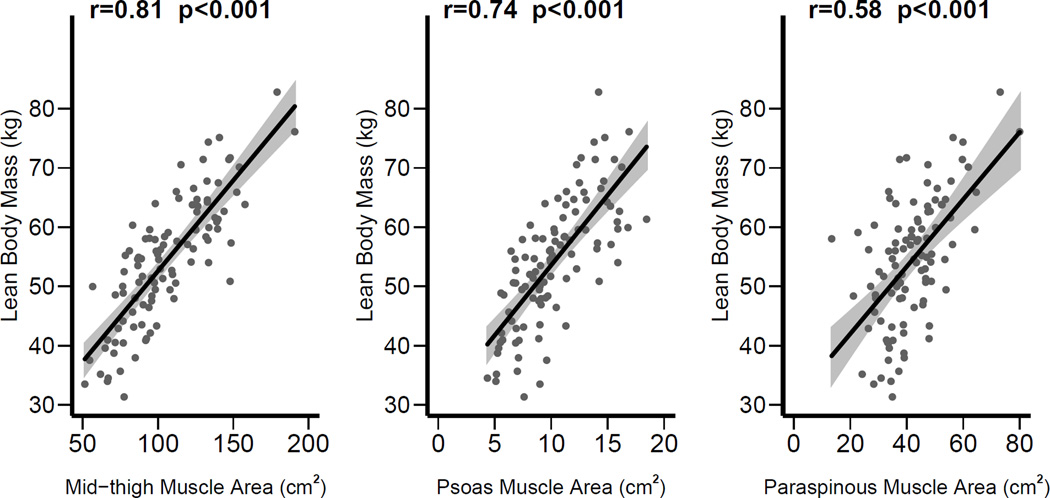

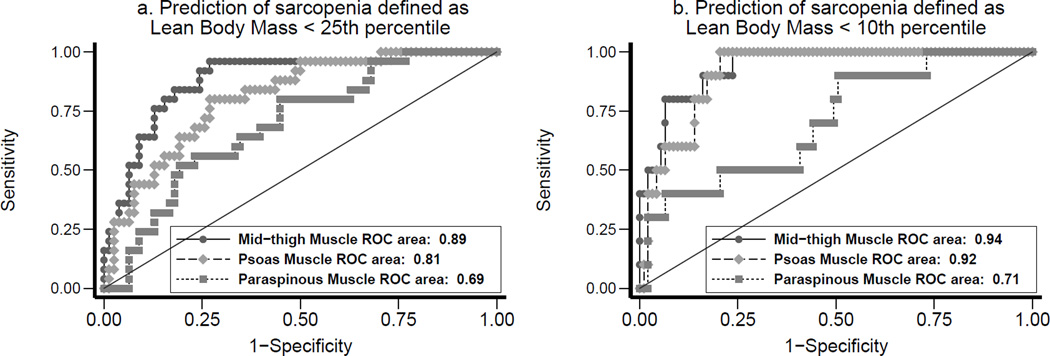

As shown in Figure 3, there was a strong correlation between mid-thigh muscle area and lean body mass (r = 0.81, p<0.001), as well as between psoas muscle area and lean body mass (r = 0.74, p < 0.001). Moderate correlation was seen between paraspinous muscle area and lean body mass (r = 0.58, p < 0.001). In multivariable models (Table 2), adjusted for age, gender, race and duration of ESRD, each SD increase in mid-thigh muscle area was associated with increase in lean body mass (8.2, 95% CI 6.9 to 9.5 kg). Similar association was seen between psoas muscle area and lean body mass (5.6, 95% CI 3.8 to 7.4 kg) and between paraspinous muscle area and lean body mass (3.6, 95% CI 2.2 to 4.9 kg). In logistic regression models of sarcopenia defined as < 25th percentile of lean body mass (Figure 4a), c-statistic was 0.89 for mid-thigh muscle area, 0.81 for psoas muscle area, and 0.69 for paraspinous muscle area. In similar logistic regression models of sarcopenia defined as < 10th percentile of lean body mass (Figure 4b), c-statistic was 0.94 for mid-thigh muscle area, 0.92 for psoas muscle area, and 0.71 for paraspinous muscle area.

Figure 3.

Correlations of mid-thigh, psoas, and paraspinous muscle areas with total lean body mass measured by DEXA.

Table 2.

Regression models for lean body mass and serum albumin as dependent variables

| Lean body mass (kg) β (95% CI) |

Serum albumin (g/L) β (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| For each SD increase in mid-thigh muscle area | 8.2 (6.9, 9.5) | 0.03 (−0.05, 0.12) |

| For each SD increase in psoas muscle area | 5.6 (3.8, 7.4) | 0.03 (−0.06, 0.12) |

| For each SD increase in paraspinous muscle area | 3.6 (2.2, 4.9) | 0.00 (−0.06, 0.07) |

Adjusted for age, gender, race, ESRD duration

Each SD of mid-thigh muscle area = 26.6 cm2; Each SD of psoas muscle area = 3.42 cm2

Each SD of paraspinous muscle area = 9.76 cm2

Figure 4.

Receiver Operator Characteristics (ROC) curves for sarcopenia defined as < 25th percentile of gender-specific lean body mass and for sarcopenia defined as < 10th percentile of gender-specific lean body mass.

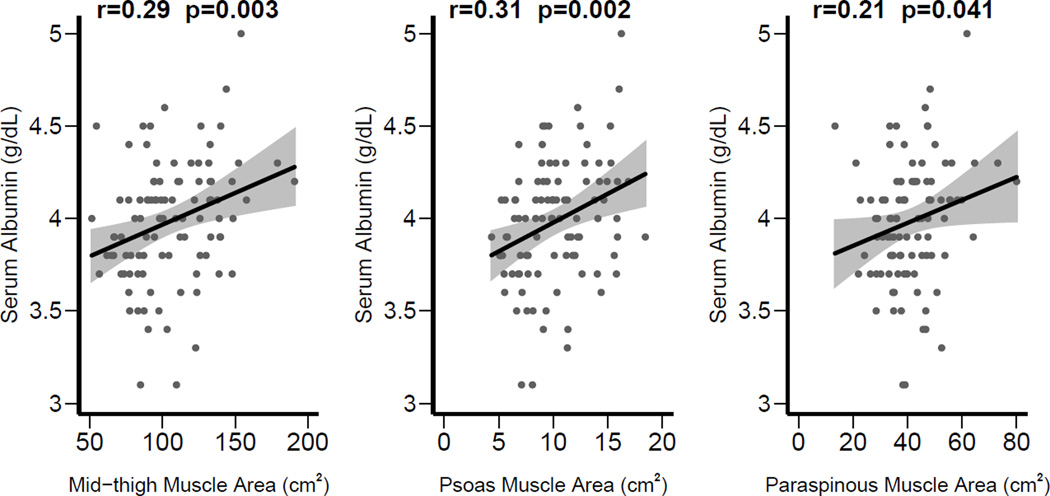

As shown in Figure 5, mid-thigh muscle area, psoas muscle area, and paraspinous muscle area had similar correlations with serum albumin (r = 0.29 for mid-thigh, r = 0.31 for psoas, and r = 0.21 for paraspinous muscle). In multivariable models (Table 2), none of the MRI measurements (mid-thigh, psoas, or paraspinous muscle area) were associated with serum albumin when adjusted.

Figure 5.

Correlations of mid-thigh, psoas, and paraspinous muscle areas with predialysis serum albumin.

In sensitivity analyses, results were similar after excluding Vanderbilt participants. Each SD increase in mid-thigh (8.1, 95% CI 6.7 to 9.6 kg), psoas (6.6, 95% CI 4.4 to 8.8) kg, or paraspinous (3.6, 95% CI 2.0 to 5.2 kg) muscle area was associated with increase in lean body mass. In logistic regression models, c-statistic (< 25th percentile of lean body mass) was 0.95 for mid-thigh, 0.85 for psoas, and 0.77 for paraspinous muscle areas. In similar models of sarcopenia defined as < 10th percentile of lean body mass, the corresponding c-statistic were 0.96, 0.90, and 0.79.

In those without pedal edema, similar associations were seen between mid-thigh and lean body mass (for each SD increase of mid-thigh muscle area, 7.6, 95% CI 6.1 to 9.1 kg), between psoas and lean body mass (for each SD increase of psoas muscle area, 5.1, 95% CI 3.2 to 7.1 kg), and between paraspinous and lean body mass (for each SD increase of paraspinous muscle area, 3.0, 95% CI 1.5 to 4.6). In logistic regression models, c-statistic (< 25th percentile of lean body mass) was 0.88 for mid-thigh, 0.78 for psoas, and 0.74 for paraspinous muscle areas. With sarcopenia defined as < 10th percentile of lean body mass, the corresponding c-statistic were 0.91, 0.91 and 0.72, respectively.

Discussion

Muscle mass measurement is used to evaluate nutrition and assess the effect of exercise interventions. Muscle mass has been correlated with functional independence (13) and decreased fall risk (14) in the elderly, and is strongly correlated with survival in MHD patients (15–17). Hence, measurement of lean body mass as a measure of muscle mass is useful in both research and clinical settings.

In previous studies, the use of mid-thigh muscle area or volume has been shown to be a reliable measure of muscle mass. In a study of 387 healthy white men and women, whole-body and regional measures of skeletal muscle were obtained by MRI (8). The regional skeletal muscle measures, whether obtained by using a single image (mid -thigh level) or a series of 7 consecutive images covering 31 cm of thigh, were strongly correlated with whole-body MRI measurement of skeletal muscle (P <0.001). Independent of sex, the thigh measures derived from a single image were strong correlates of whole-body skeletal muscle mass (men: R2 = 0.77, women: R2 =0.79). In a study of 46 hemodialysis patients, the cross-sectional area of the thigh muscle measured by CT was significantly correlated (r= 0.86, P < 0.01) with creatinine production determined from the sum of creatinine appearing in the dialysate and the estimated metabolic degradation (18).

Decreased psoas muscle area measured with CT has been shown to be associated with increased risk of osteoporotic fractures in elderly men (19). Psoas muscle area measured with CT has been proposed as a measure of sarcopenia by one group which has shown correlation of decreased psoas area with mortality following liver transplant (20), mortality following open aortic aneurysm repair (21), and cortisol levels in subjects with hypercortisolism (22). However, these studies did not validate psoas muscle area as a measure of whole lean body mass. One study of cancer patients has shown that total muscle cross sectional area (not specifically psoas area) on a single CT image at the L3 level correlated well with total lean body mass measured by DEXA (23). Another study has shown that total muscle cross-sectional area in an axial MRI image at the L4–5 level in healthy subjects is strongly correlated with whole-body lean body mass measured by multi-slice whole body MRI (24). None of these studies examined MHD patients. Our study is unique in showing that in MHD patients, psoas muscle area provides a good measure of lean body mass, better than paraspinous muscle area, but slightly inferior to mid-thigh measurement. Psoas muscle area in a single L4–5 MRI image can serve as a substitute for mid-thigh MRI, and psoas area is strongly correlated with lean body mass measured by DEXA (Table 2). Our study also validates psoas muscle measurement at L4–5 as an accurate predictor of sarcopenia. For psoas muscle area, the area under the ROC curve was 0.81 for sarcopenia defined as < 25th percentile lean body mass (Figure 4a) and 0.92 for < 10th percentile (Figure 4b).

Mid-thigh muscle area had a stronger association with lean body mass and sarcopenia (Figures 3–4 and Table 2) than psoas muscle area. Therefore, if measurement of muscle mass is the primary goal, mid-thigh MRI might be better than L4–L5 section MRI. However, in studies where visceral fat is being measured with abdominal MRI, measurement of paraspinous muscle area from the same abdominal images may be an acceptable substitute for mid-thigh MRI.

The current study only included MHD patients. Hence, further studies are warranted to determine whether these results are applicable to the general population. Longitudinal studies are also warranted to test whether changes in psoas muscle area correlate with outcomes.

We conclude that imaging of the psoas muscles can be performed as part of routine abdominal MRI with minimal addition to imaging time, and serves as a reasonable measure of lean muscle mass in addition to providing information on visceral fat.

Practical Applications

In body composition studies in which abdominal MRI is performed for characterization of visceral fat, psoas muscle area measured on a single abdominal MR image may be a suitable substitute for time-consuming separate MRI of the legs as a measure of lean muscle mass.

Summary.

Psoas and paraspinous muscle cross-section areas were measured with MRI on a single axial image of the abdomen at the L4–5 level in a population of hemodialysis patients and were found to correlate with lean body mass measured by DEXA and thigh muscle cross-sectional area measured with MRI of the leg. Psoas and paraspinous muscle cross-section areas were also found to be accurate measures of sarcopenia. Psoas area is more strongly correlated with lean body mass and leg MRI than paraspinous muscle area. In body composition studies in which abdominal MRI is performed for characterization of visceral fat, psoas muscle area measured on a single abdominal MR image may be a suitable substitute for time-consuming separate MRI of the legs as a measure of lean muscle mass.

Acknowledgments

Support

This study is supported by the following: R01- DK077298 and R01 – DK078112 awarded to SB, K24 DK62849 to TAI, 5 K08 CA112449 to GM, University of Utah Study Design and Biostatistics Center, with funding in part from the Public Health Services research grant numbers UL1-RR025764, 1UL-1RR024975 and C06-RR11234 from the National Center for Research Resources.

Appendix

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Protocol

Images of the legs were acquired with a 3.0 Tesla Siemens Trio system (University of Utah) or a 3.0 Tesla Philips Achieva system (Vanderbilt University) using the spine coil incorporated in the scan table posteriorly combined with the torso array coil anteriorly. Localizing images were obtained depicting the entire femur in the coronal plane. The midpoint of the thigh was determined on the coronal images as the point equidistant from the top of the femoral head and the bottom of the femoral condyles. Multislice axial imaging was then performed with the three-point Dixon method, with multislice acquisition centered at the midpoint of the thigh. At the University of Utah, three successive gradient-recalled echo (GRE) acquisitions were performed, each of which acquired a single echo, with echo times of 5.15ms, 6.4ms, and 7.65ms. These echo times correspond to in- and out-of-phase configuration of fat and water at 3.0 Tesla. An odd number of axial slices were obtained with slice thickness of 5mm at intervals of 10 mm with the number of slices chosen to cover half the length of the femur, typically 27 slices, centered at the midpoint of the femur. An image matrix of 512 × 288 was used over a variable field of view chosen to adequately include the entire axial cross-section of the upper thighs, typically about 45 × 25 cm resulting in in-plane resolution of about 0.9 × 0.9 mm. When using the Dixon MRI method for fat and water imaging, multiple echoes can sometimes be acquired in the same sequence repetition to decrease imaging time. However, this reduces the spatial resolution that is possible in the images. For this application, since the legs can be made relatively immobile for an extended scan time, we opted to have three separate sequence repetitions for the three echoes in order to allow very high spatial resolution, at the cost of longer imaging time. Total imaging time for the legs is about 15 minutes. The protocol at Vanderbilt University was the same as at the University of Utah except that a Philips product 3-point Dixon sequence was used to form the source images.

A single axial image was obtained at the L4–5 level for estimation of psoas and paraspinous muscle cross-section. This image was obtained with the same three-point Dixon method and tissue signal model as the leg images. The torso array coil was positioned anterior to the abdomen and was used along with the spine array coil posteriorly. Two acquisitions of a single 2D slice were obtained during a single breath hold. The first acquisition provides the two in-phase images with echo times of 2.75 and 5.15 msec. The second acquisition provides the out of phase echo time of 3.95 msec. An image matrix size of 192 × 156 was used over a field of view fitted to the patient, typically about 36 × 30 cm, resulting in a spatial resolution of about 2 × 2 mm. The lower resolution of the abdominal image compared to the leg images allows the acquisition of two echoes in one sequence repetition time, as well as the use of shorter in-phase and out-of-phase echo times. Each of the two acquisitions required 7 seconds of imaging time. The acquisitions ran back-to-back for a total imaging time of about 14 seconds.

For both the leg and abdomen images, T1 weighting effects in the fat and water images were corrected based on the GRE signal equation, assuming a T1 of 340 ms for the signal component at the fat resonant frequency and a T1 of 640 ms for the signal component at the water resonant frequency. These values were measured in a volunteer in the 3T Trio scanner by a spin-echo inversion recovery sequence. Fat-water separation imaging gives images corresponding to tissue components at the resonant frequency of fat and at the resonant frequency of water. Only fat contributes to fat resonant frequency images. The water resonant frequency image includes signal from water in non-fat soft tissues, including muscle, nerves, blood, and vessels. Water-only images represent primarily muscle, with minimal contribution from nerves and vessels. After fat and water image signal intensities were corrected for T1 effects, the percent volume fraction of fat and non-fat tissue were calculated for each image pixel using an algorithm adapted from Longo et al. (10).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure Declaration

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The results presented in this paper have not been published previously in whole or part, except in abstract format.

References

- 1.Pollock CA, Allen BJ, Warden RA, et al. Total-body nitrogen by neutron activation in maintenance dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1990 Jul;16(1):38–45. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80783-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NKF KDOQI GUIDELINES 2000. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Nutrition in Chronic Renal Failure. [1/3/12]; Available from: http://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guidelines_updates/doqi_nut.html. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crim MC, Calloway DH, Margen S. Creatine metabolism in men: urinary creatine and creatinine excretions with creatine feeding. J Nutr. 1975 Apr;105(4):428–438. doi: 10.1093/jn/105.4.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forbes GB, Bruining GJ. Urinary creatinine excretion and lean body mass. Am J Clin Nutr. 1976;29(12):1359–1366. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/29.12.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dumler F. Use of bioelectric impedance analysis and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry for monitoring the nutritional status of dialysis patients. ASAIO J. 1997;43(3):256–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang SH, Cho KH, Park JW, Yoon KW, Do JY. Comparison of bioimpedance analysis and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry body composition measurements in peritoneal dialysis patients according to edema. Clin Nephrol. 2013;79(4):261–268. doi: 10.5414/CN107693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sjostrom L. A computer-tomography based multicompartment body composition technique and anthropometric predictions of lean body mass, total and subcutaneous adipose tissue. Int J Obesity. 1991;15(Suppl 2):19–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SJ, Janssen I, Heymsfield SB, Ross R. Relation between whole-body and regional measures of human skeletal muscle. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(5):1215–1221. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.5.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glover GH, Schneider E. Three-point Dixon technique for true water/fat decomposition with B0 inhomogeneity correction. Magn Reson Med. 1991;18(2):371–383. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910180211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Longo R, Pollesello P, Ricci C, et al. Proton MR spectroscopy in quantitative in vivo determination of fat content in human liver steatosis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1995;5(3):281–285. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880050311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marcus RL, Addison O, Dibble LE, Foreman KB, Morrell G, Lastayo P. Intramuscular adipose tissue, sarcopenia, and mobility function in older individuals. J Aging Res. 2012;2012:629–637. doi: 10.1155/2012/629637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marcus RL, Smith S, Morrell G, et al. Comparison of Combined Aerobic and High-Force Eccentric Resistance Exercise With Aerobic Exercise Only for People With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Phys Ther. 2008 doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haight T, Tager I, Sternfeld B, Satariano W, van der Laan M. Effects of body composition and leisure-time physical activity on transitions in physical functioning in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(7):607–617. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaStayo PC, Ewy GA, Pierotti DD, Johns RK, Lindstedt S. The positive effects of negative work: increased muscle strength and decreased fall risk in a frail elderly population. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(5):M419–M424. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.5.m419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beddhu S, Pappas LM, Ramkumar N, Samore M. Effects of body size and body composition on survival in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(9):2366–2372. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000083905.72794.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molnar MZ, Streja E, Kovesdy CP, et al. Associations of body mass index and weight loss with mortality in transplant-waitlisted maintenance hemodialysis patients. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(4):725–736. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Su CT, Yabes J, Pike F, et al. Changes in Anthropometry and Mortality in Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients in the HEMO Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013 doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaizu Y, Ohkawa S, Kumagai H. Muscle mass index in haemodialysis patients: a comparison of indices obtained by routine clinical examinations. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002 Mar;17(3):442–448. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.3.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheu Y, Marshall LM, Holton KF, et al. Abdominal body composition measured by quantitative computed tomography and risk of non-spine fractures: the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Study. Osteoporosis Int. 2013;24(8):2231–2241. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2322-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Englesbe MJ, Patel SP, He K, et al. Sarcopenia and mortality after liver transplantation. J Am Coll Surgeons. 2010;211(2):271–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JS, He K, Harbaugh CM, et al. Frailty, core muscle size, and mortality in patients undergoing open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(4):912–917. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.10.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller BS, Ignatoski KM, Daignault S, et al. A quantitative tool to assess degree of sarcopenia objectively in patients with hypercortisolism. Surgery. 2011;150(6):1178–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mourtzakis M, Prado CM, Lieffers JR, Reiman T, McCargar LJ, Baracos VE. A practical and precise approach to quantification of body composition in cancer patients using computed tomography images acquired during routine care. Appl Physiol Nutr Me. 2008;33(5):997–1006. doi: 10.1139/H08-075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shen W, Punyanitya M, Wang Z, et al. Total body skeletal muscle and adipose tissue volumes: estimation from a single abdominal cross-sectional image. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97(6):2333–2338. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00744.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]