Abstract

Osteosarcoma (OS) is the most common type of primary solid tumor that develops in bone. Although standard chemotherapy has significantly improved long-term survival over the past few decades, the outcome for those patients with metastatic or recurrent OS remains dismally poor and, therefore, novel agents and treatment regimens are urgently required. A hypothesis to explain the resistance of OS to chemotherapy is the existence of drug resistant CSCs with progenitor properties that are responsible of tumor relapses and metastasis. These subpopulations of CSCs commonly emerge during tumor evolution from the cell-of-origin, which are the normal cells that acquire the first cancer-promoting mutations to initiate tumor formation. In OS, several cell types along the osteogenic lineage have been proposed as cell-of-origin. Both the cell-of-origin and their derived CSC subpopulations are highly influenced by environmental and epigenetic factors and, therefore, targeting the OS-CSC environment and niche is the rationale for many recently postulated therapies. Likewise, some strategies for targeting CSC-associated signaling pathways have already been tested in both preclinical and clinical settings. This review recapitulates current OS cell-of-origin models, the properties of the OS-CSC and its niche, and potential new therapies able to target OS-CSCs.

1. Introduction

OS is a malignant neoplasm in which the neoplastic cells produce bone and is the most frequent primary sarcoma of the skeleton. The tumor is primary when the underlying bone is normal and secondary when the bone is altered by conditions, such as prior irradiation, coexisting Paget disease, infarction, or other disorders. It has a bimodal age distribution with most cases developing between the ages of 10–16 years and a second smaller peak in older adults (30% of cases in patients over 40 years) [1]. In addition, OS is the most common radiation-induced sarcoma. It has an unknown etiology, although there is an increased incidence of primary OS associated with several genetic syndromes such as Li-Fraumeni, hereditary retinoblastoma, and Rothmund Thomson (see below).

Primary OS may arise in any bone, although the vast majority originate in the long bones of the extremities, especially the distal femur (30%), followed by the proximal tibia (15%), and proximal humerus (15%), which represent sites containing the most proliferative growth plates. Within long bones, the tumor is usually (90%) located in the metaphysis and arises as an enlarging and palpable mass, with progressive pain [2].

The hallmark diagnostic feature of OS is the detection of osteoid matrix produced by the neoplastic cells. However, the most common type of OS, conventional OS, has a very broad spectrum of histological appearances and is subclassified according to the predominant type of stroma (osteoblastic, chondroblastic, fibroblastic, giant cell rich, etc.), although this subclassification has no prognostic relevance [1].

At present, surgery with chemotherapy is the first-line treatment for most OS [3]. Almost all patients receive neoadjuvant intravenous combinational chemotherapy (doxorubicin and cisplatin with or without methotrexate) as initial treatment. Surgical resection of the primary tumor with adequate margins is an essential component of the curative strategy for patients with localized OS. If complete surgical resection is not feasible or if surgical margins are inadequate, radiation therapy may improve the local control rate. The postoperative chemotherapy regimen usually depends on the extent of tumor necrosis observed [1, 3].

Advances in the clinical management of OS have led to a significant increase in 5-year survival rates, which in most centers now largely exceed 50%. However, survival rates for patients presenting with metastatic and recurrent disease have historically remained essentially unchanged with a survival rate below 20%, highlighting the need for a better understanding of the disease leading to the development of novel therapies [4].

2. Genomics of OS

OS is characterized by the presence of complex karyotypes indicative of severe chromosomal instability. This accumulation of barely recurrent genetic alterations hinders the identification of OS-driver genes. A powerful causal-effect relation between specific gene alterations and OS initiation came from studies of human hereditary disorders characterized by a predisposition to the development of OS [5, 6]. The functional validation of these genomic alterations as driver events was confirmed in mouse models [5, 7]. The strongest genetic association for sporadic and hereditary OS is with the retinoblastoma (RB) and the P53 tumor suppressor genes; meanwhile other relevant alterations include mutations in other cell cycle regulators, oncogenes, and DNA helicases [5, 6].

Li-Fraumeni and hereditary retinoblastoma syndromes are caused by heterozygous germ-line mutations of P53 and RB, respectively, and patients presenting with these disorders have a higher predisposition to a range of cancers, including OS [8, 9]. Importantly, mutations in P53 and/or RB genes and other components of their pathways are also common in sporadic OS, suggesting a relevant role for alterations in these tumor suppression genes or their related signaling pathways in OS development [5, 6, 10, 11]. On this basis, several P53 and/or RB-deficient mouse models have been developed to model sarcomagenesis [5, 12]. The most productive OS models have been developed using conditional mesenchymal/osteogenic lineage-restricted mutation of P53 and RB (see below). These models indicate that P53 inactivation is an initiating event in OS [13–15]. On the other hand, the depletion of RB alone was not sufficient to induce sarcoma formation in mice. Notably, RB mutation strongly reduced the latency required for sarcoma formation in P53-deficient mice, although it decreased the proportion of OS formed [13, 15]. It was reported that RB is needed to promote the osteogenic differentiation program of mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs) [16] and, therefore, it could be speculated that RB mutations synergize with P53 inactivation in OS formation only when mutations occur in osteogenic-committed cell types; meanwhile it could favor other sarcoma phenotypes when mutated in more immature cell types (see below).

Other genes involved in P53 or RB signaling have also been found to be mutated in sporadic OS [6, 17]. For example, the INK4A/ARF locus, which encodes for P16INK4A and P19ARF genes, is deleted in approximately 10% of OS [18, 19]. P16INK4A and P19ARF proteins contribute to the stabilization of RB and P53 proteins through the inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) and mouse double minute 2 homolog (MDM2) repressors, respectively [20]. Interestingly, the region 12q13, containing CDK4 and MDM2, is amplified in up to 10% of OS [6, 21]. In addition, the absence of expression of P16INK4A correlated with a decreased survival in pediatric OS, while the amplification of MDM2 has been associated with the development of metastases in OS [6, 22]. The amplification and/or increased expression of other cell cycle genes, such as Cyclins D1 and E, have also been reported in OS, further highlighting an important role of defective cell cycle regulation in OS development [17, 23].

Several oncogenes like C-FOS, C-JUN, and C-MYC also play a role in OS development. C-FOS, C-JUN N-terminal kinase, and C-JUN were found elevated in OS and its expression and activation were associated with the progression of human OS [24–26]. Transgenic mice overexpressing C-FOS developed OS, further suggesting a role in OS pathogenesis [27]. C-MYC amplification was found in sporadic OS and OS associated with Paget's disease [28, 29] and, clinically, high C-MYC expression correlates with worse outcome in OS patients [30].

A recent study using a Sleeping Beauty transposon-based forward genetic screen in mice, with or without somatic loss of P53 restricted to committed osteoblast progenitors, identified 36 putative protooncogenes and 196 potential tumor suppressor genes. Among these OS-driver candidates the protumorigenic role of PTEN and the axon guidance genes SEMA4D and SEMA6D were functionally validated. Moreover, this study highlighted an enrichment of genes involved in PI3K-AKT-mTOR, MAPK, and ERBB signaling cascades [51]. Confirming the heterogeneity of OS, an exome sequencing-based study showed that identified candidate OS-driver genes were associated with the development of a small set of tumors, suggesting that multiple oncogenic pathways drive the characteristic chromosomal instability during OS development. However, the overall mutation signatures in these tumors were reminiscent of BRCA1/2 deficient tumors, a finding with possible therapeutic implications [52]. Comparative genomic hybridization analysis combined with gene expression data also resulted in the identification of genomic alterations associated with a small proportion of OS, which may play a role in the OS pathogenesis. For instance, the cell division-related genes MCM4 and LATS2, the antiapoptotic genes BIRC2 and BIRC3, and other genes including CCT3, COPS3, and WWP1 were reported to be found as potential OS drivers [53–55]. Likewise, genomic analysis indicated that ossification factor genes such as MET, TWIST, and APC are frequently mutated in pediatric high-grade OS and these alterations correlated to a worse outcome, thus suggesting a role in OS development [56].

Other genetic and epigenetic alterations likely involved in OS pathogenesis include mutations in RECQL4 DNA helicase associated with the OS-predisposing Rothmund Thomson syndrome, amplification/mutation in the osteogenic factor RUNX2, loss of heterozygosity of FGFR2 and BUB3, enhanced telomerase activity, deletion of PRKAR1A, and reduced expression of WWOX or hypermethylation of HIC1 in P53 mutated tumors among others [5, 7, 57–61].

3. Cell-of-Origin for OS

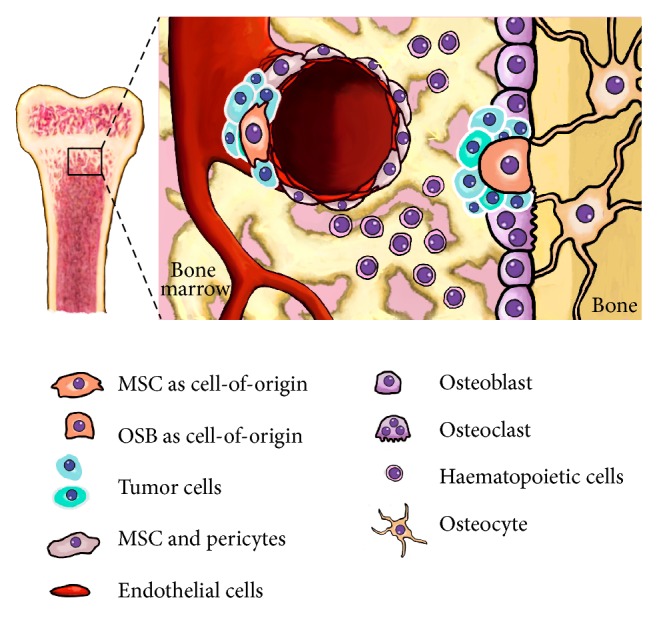

The cell-of-origin concept refers to the normal cell type that acquires the first cancer-promoting mutations and initiates tumor formation [62]. During the last 10 years mounting evidence has placed MSCs and/or their immediate lineage progenitors as the most likely cell-of-origin for many types of sarcomas including OS [12, 63, 64] (Figure 1). Both translocation- and non-translocation-associated sarcomas have been modeled by introducing relevant mutations into MSC [12, 64–66]. In the case of OS, most of the cell-of-origin models are based on mutated P53, alone or in combination with RB inactivation, in the mesenchymal/osteogenic lineage of mouse models or in murine MSC [63]. By crossing mice with conditional (floxed) alleles of P53 and/or RB with mice that have the CRE recombinase gene under the control of different tissue-restricted promoters, several groups were able to generate OS development in vivo. Thus, the inactivation of P53 and/or RB in early mesenchymal progenitors of embryonic limb buds through PRX1-driven CRE expression (PRX1-CRE) resulted in sarcoma development, presenting an OS incidence of 60% in P53 −/− mice and 20–30% in P53 −/− RB −/− mice, where most of the alternate tumors formed poorly differentiated soft tissue sarcomas [14, 16]. Meanwhile, the inactivation of these cell cycle regulators in osteoblast precursors [OSX1 (Osterix)-CRE] resulted in a higher incidence of OS formation in both P53 −/− (100%) and P53 −/− RB −/− mice (between 53 and 100%) [13, 15, 16]. Similarly, ShRNA-mediated depletion of P53, together with CRE-mediated inactivation of RB in osteoblast precursors (OSX1 restricted), resulted in a delayed and consistent formation of OS, presenting a higher degree of osteoblastic differentiation than other CRE-based models [67]. Within the osteogenic differentiation lineage, targeting of P53 in mature osteoblasts, using COL1A1- (collagen-1-alpha-1-) driven CRE expression to target P53 or OCN- (Osteocalcin-) driven expression of SV40-T antigen to inactivate P53 and RB, also resulted in high OS formation incidence (85–100%) [14, 68]. Moreover, another study using a SV40 immortalized murine osteocyte cell line suggests that fully differentiated osteocytes may also serve as an OS-initiating cell [69]. Besides P53 deficiency-based OS models, it has been proven that the expression of the intracellular domain of NOTCH1 (NICD), leading to constitutive NOTCH activation, in osteoblasts (COL1A1-driven expression) was sufficient to induce the formation of bone tumors, including OS [70]. Moreover, NOTCH activation combined with loss of P53 synergistically accelerates OS formation. Notably, the activation of NOTCH in mesenchymal progenitors or in osteoblast precursors produces embryonic lethality [70]. Similarly, mice with upregulated Hedgehog (HH) signaling in mature osteoblasts with a P53 heterozygous background developed OS with high penetrance [71].

Figure 1.

Cell-of-origin for OS. The figure shows the most relevant cell types present in the bone microenvironment. MSCs, represented in a perivascular niche, and their derived cell types along the osteogenic lineage, such as the osteoblasts (OSB), are strong candidates to acquire the first cancer-promoting mutations and initiate OS formation.

These results support the concept that OS originates in the population of cells that undergoes osteoblast commitment rather than in immature MSC. Nevertheless, these experiments also show that, although presenting at a lower incidence, early mesenchymal progenitors targeted with relevant mutations could also initiate OS formation, most likely influenced by certain microenvironment signals. In this regard, the comparison in a single study of the OS formation ability of P53/RB-disrupted immature MSC (PRX1-CRE) and osteoblast committed cells (COL1A1-CRE and OCN-CRE) confirmed that all types of cells were able to initiate OS formation and showed that the level of osteoblastic differentiation of tumors did not correlate with the degree of differentiation of the cell-of-origin, suggesting that epigenetic dedifferentiation mechanisms could be active in mature osteoblasts during osteosarcomagenesis [72]. The fact that early progenitors might represent a cell-of-origin for OS is also strengthened by the observation of different histological subtypes, which may reflect the ability of these progenitors to undergo other differentiation pathways besides osteogenesis.

Studies using murine MSC containing CRE-inactivated P53 and/or RB alleles also reveal relevant clues about the nature of the OS-initiating cell and the factors conditioning their sarcomagenic potential. P53 −/− and P53 −/− RB −/− adipose-derived-MSC (ASC) or BM-derived-MSC (BM-MSC) give rise to leiomyosarcoma-like tumors when injected subcutaneously into immunodeficient mice [72–74]. Otherwise, when BM-MSCs were differentiated along the osteoblastic lineage before CRE-mediated deletion of P53 and RB, they generated OS-like tumors upon subcutaneous injection into immunodeficient mice, whereas P53 −/− RB −/− ASC-derived osteogenic progenitors did not display tumorigenic potential [74]. These data highlight the differences in the sarcomagenic potential of MSC from different tissues and indicate that a certain level of osteogenic differentiation of BM-MSC is needed for the development of the OS phenotype. Nevertheless, orthotopic (intrabone or periosteal) inoculation of P53 −/− and P53 −/− RB −/− BM-MSC and ASC undifferentiated MSC consistently generated osteoblastic OS displaying human OS radiographic and histological features alongside metastatic potential. Importantly, all the histological and radiological OS-related features were less evident or completely lost in the areas of the tumor distant from the recipient bone, thus demonstrating that bone microenvironmental signals play a role in osteogenic differentiation and sarcomagenesis by defining the sarcoma phenotype [75]. In addition, an ectopic model to assay osteosarcomagenesis that relies on the use of P53 −/− RB −/− MSC embedded in hydroxyapatite/tricalcium phosphate ceramics also demonstrates a relevant contribution of bone microenvironmental factors, like bone morphogenic protein 2 (BMP2) and calcified substrates, in the acquisition of the OS phenotype [75].

Furthermore, evidence of undifferentiated MSC as cell-of-origin for OS comes from the introduction of other oncogenic events into undifferentiated BM-MSC, like the expression of C-MYC in a P16INK4A −/− P19ARF −/− genetic background or the aneuploidization accompanied by the loss of the INKAA locus, resulting in OS development [76, 77]. Additionally, similar gene expression signatures were found between human OS samples and undifferentiated MSC or osteogenic-committed MSC [78], suggesting that OS may develop from both osteogenic progenitors and undifferentiated MSC.

Finally, extraskeletal OS is a very rare type of soft tissue mesenchymal neoplasm that produces osteoid. It could be speculated that, rather than BM-MSC, extraskeletal OS could be initiated by MSCs from soft tissues (muscle-derived MSC, ASC, etc.) presenting mutations that favor osteogenic differentiation and/or influenced by pathologically osteogenic signals from the microenvironment [79]. In this regard this type of tumors could be related to fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva, a rare genetic disorder of connective tissue characterized by the presence of activating mutations in the ACVR1 gene, which encode a BMP type I receptor [80].

Overall, the most likely situation is that either MSC-derived osteogenic progenitors or undifferentiated MSC may represent the cell-of-origin for OS under the influence of proper microenvironmental or epigenetic signals.

4. Osteosarcoma Cancer Stem Cell

Experimental evidence supports the notion that sarcomas are hierarchically organized and sustained by a subpopulation of self-renewing cells that can generate the full repertoire of tumor cells and display tumor reinitiating properties [12, 81–83]. In the most likely scenario, these CSC subpopulations emerge after the accumulation of further epigenetic and/or genetic alterations in a cell within the aberrant population, initially generated by the cell-of-origin [62], that is, MSC-derived cell types.

Several methods have been developed to isolate and/or enrich subpopulations with stem cell properties within the tumors [82–85]. The isolation of OS-CSC was first achieved on the basis of their ability to form spherical and clonal expanding colonies (sarcospheres) in anchorage-independent and serum-starved conditions [86–88]. This sarcosphere formation may be further improved by reproducing the hypoxic conditions of tumor microenvironment [89]. In addition, OS-CSCs are commonly isolated by sorting cells according to the expression of specific surface markers associated with stemness and/or tumorigenesis. For example, CD133+ [90–92], STRO1+ CD117+ [93], and CD271+ populations [94] sorted from OS cell lines demonstrated CSC-like features. Other methods used to isolate OS-CSCs include the identification of a “side population” of cells able to exclude fluorescent dyes, alone or in combination with surface markers like CD248 [95, 96]; the sorting of cells with aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) activity [97, 98]; the tracking of subpopulations that express pluripotency-associated genes, such as OCT-4 [99]; the enrichment of subpopulations with high telomerase activity [100, 101]; or the long-term treatment with chemotherapy [102, 103]. Reinforcing their expected mesenchymal progenitor origin, many of these sarcoma-initiating cells express MSC markers [86, 93, 99, 104] and retain in vitro differentiation properties, giving rise to adipogenic, chondrogenic, and osteogenic lineages [86, 104]. These CSC commonly show increased expression of the pluripotent stem cell markers OCT3/4, NANOG, and SOX2 [87, 89, 105, 106]. Remarkably, SOX2 has been reported to identify a population of CSC in OS required for self-renewal and tumorigenesis [107]. Importantly, CSCs isolated from OS are able to self-renew and sustain tumor generation in serial transplantation experiments and are associated with metastasis and drug resistance [89, 93, 96, 98, 105, 107]. This increased chemoresistance of CSC subpopulations has been associated with an increase in the DNA repair ability, with an inhibition of the apoptotic signaling, with increased levels of lysosomal activity due to the overexpression of vacuolar ATPse [108], and, specially, with a gain in the drug efflux capacity due to the overexpression of the ABC transporters [96, 102, 105, 109–111]. In this line, the inhibition of the ABC transporters is able to sensitize OS-derived sarcosphere to doxorubicin [112]. Therefore, it is clear that OS-CSCs possess specific properties, which make them more resistant to therapies.

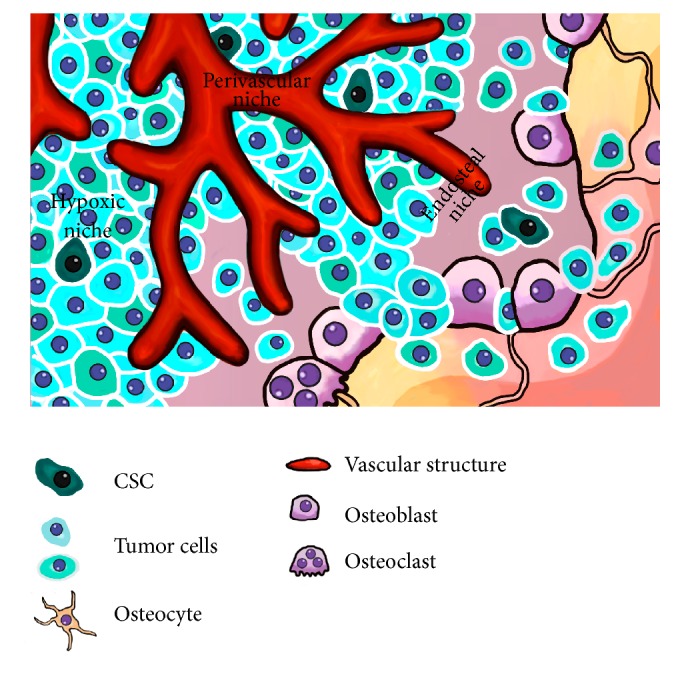

Similar to normal stem cells, microenvironmental niches may play a role in OS-CSC regulation [113]. In this regard, many bone microenvironment signals, including those mediated by fibroblastic growth factor (FGF), transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), BMP, vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF), hypoxia inducible factors (HIF1), wingless-type MMTV integration site family (WNT), HH, or NOTCH among others, are deregulated in OS and seem to be involved in the regulation of their self-renewal, differentiation, growth, drug resistance, and/or metastatic potential of OS-CSC subpopulations (reviewed in [2]). Three types of niches within the bone microenvironment where these signaling pathways are particularly active could be inferred to be the location OS-CSCs: the perivascular niche, the hypoxic niche, and the endosteal niche (Figure 2). OS is a highly vascularized tumor and as OS-CSCs seem to arise from MSC it is likely that OS-CSCs may be located in the same perivascular niche already well-described for normal MSCs. Besides providing stemness signals, this perivascular location would favor migration and metastasis of CSC [84, 114]. On the other hand, the bone is a hypoxic environment and hypoxia-induced signaling is a key environmental factor involved in stemness maintenance, OS progression, and drug resistance and therefore could constitute a suitable niche for OS-CSCs [2, 115]. Finally, the endosteal niche is a rich environment where tumor cells interfere with the bone remodeling process, establishing a “vicious cycle” that favors osteoclast-mediated osteolysis and the subsequent release of calcium and growth factors (FGF, TGF-β, IGF1, BMP, etc.), which support stem and tumorigenic properties [2, 116, 117].

Figure 2.

OS-CSC niches. The figure represents possible niches for CSCs in OS. Suggested locations for CSCs are the perivascular niche, the endosteal niche, and areas of poor vascularization (hypoxic niche).

5. Cancer Stem Cell Targeted Therapies in OS

Studies concerning the molecular biology of cancer are now promoting the identification of new potential therapeutic targets with molecular rationale able to target OS. As a result, therapies targeting altered signaling are being thoroughly tested in several clinical trials [58, 118–120] (Table 1). These strategies included the targeting of the signaling mediated by receptor tyrosine kinases (EGFR, VEGFR, IGF1R, HER2, or PDGFR), mTOR, or WNT/β-catenin. In addition, since OS-CSCs reside within the bone microenvironment and this a key factor in the regulation of tumor homeostasis, therapies directed against microenvironmental niche factors could contribute to the improvement of clinical response [2]. Therefore, several therapeutic strategies have been developed to target the role of the tumor-promoting osteoclast activity [31–33, 121], to reduce the vascularization of tumors [34, 122] and to enhance the immune response against tumors [123–126] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected clinical trials targeting altered signaling and tumor environment in OS∗.

| Target | Drug | Type of drug | Clinical trial reference number (NCT number) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell membrane receptors | |||

| ERBB2 | Trastuzumab | Monoclonal antibody | NCT00023998 |

| IGF1R | Cixutumumab | Monoclonal antibody | NCT01016015/NCT00831844/NCT01614795/NCT00720174 |

| RG1507 | Monoclonal antibody | NCT00642941 | |

| EGFR | ZD1839 | Inhibitor | NCT00132158 |

| PDGFR | Erlotinib | Inhibitor | NCT00077454 |

| Imatinib | Inhibitor | NCT00031915/NCT00030667 | |

| PRGFR/VEGFR | Sorafenib | Inhibitor |

NCT01804374/NCT00889057/NCT00880542/NCT00330421/ NCT01518413 |

| VEGFR | Pazopanib | Inhibitor |

NCT01759303/NCT02357810/NCT01130623/NCT02180867/ NCT01532687/NCT01956669 |

| Bevacizumab | Monoclonal antibody | NCT00667342 | |

| Endostar (rh-endostatin) | Inhibitor | NCT01002092 | |

|

| |||

| Intracellular signaling | |||

| mTOR | Everolimus | Inhibitor | NCT01216826 |

| Ridaforolimus | Inhibitor | NCT00093080/NCT00538239 | |

| WNT/β-catenin | Curcumin | Inhibitor | NCT00689195 |

|

| |||

| Niche cells and their signaling | |||

| Osteoclasts | Zoledronic acid | Bisphosphonate | NCT00691236 |

| Pamidronate | Bisphosphonate | NCT00586846 | |

| RANKL | Denosumab | Monoclonal antibody | NCT02470091 |

| Immune system | T cells expressing GD2 | Cells | NCT02107963 |

| GD2Bi-armed T cells | Cells | NCT02173093 | |

| Anti-GD2 | Monoclonal antibody | NCT00743496/NCT02502786 | |

| Stem and natural killer cells | Cells | NCT02409576/NCT01807468 | |

| Mifamurtide | Monocyte/macrophage activator glycopeptide | NCT02441309/NCT00631631 | |

∗Source: https://clinicaltrials.gov/. Osteosarcoma clinical trials: total: 363, open: 122.

ERBB2: Erb-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2; IGF1R: insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor; EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor; PDGFR: platelet-derived growth factor receptor; VEGFR: vascular endothelial growth factor receptor; mTOR: mechanistic target of rapamycin; WNT: wingless-type MMTV integration site family; RANKL: receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand.

As seen before, OS-CSCs are resistant to most conventional treatments like radiation and chemotherapy and are, therefore, responsible for tumor relapses and metastasis. Hence, in addition to the proposed therapies directed against specific signaling and/or tumor niches, there is a need for developing and testing therapies able to target CSC subpopulations in OS. Below, we reviewed current work reporting specific antitumoral activity on OS-CSC subpopulations or CSC-related features (Table 2).

Table 2.

Therapeutic agents with reported activity on OS-CSCs subpopulations or related properties.

| Therapeutic agent | Proposed mechanisms of action | Effect on CSC/CSC properties | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parthenolide | NF-κB inhibition/oxidative stress induction | Sensitizes to ionizing radiation reducing the viability of CD133+ CSCs | [31] |

| BRM270 | NF-κB/CDK6/IL6 downregulation | Induces programmed cell death | [32] |

| BYL719 | PI3K inhibition | Induces cell cycle arrest and inhibits migration | [33] |

| LY294002 | PI3K inhibition | Induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in OS-sarcospheres | [34] |

| SB431542 | TGF-β inhibition | Reduces self-renewal and differentiation and increases chemosensitivity of OS-sarcospheres | [35] |

| miR-382 expression | YB-1 inhibition | Decreases OS-CSCs, reduces metastatic potential, and inhibits tumor formation from CD133+ OS cells | [36] |

| miR-29b-1 expression | — | Reduces sarcosphere formation and induces chemosensitization of OS cells | [37] |

| miR-133a inhibition | — | Reduces cell invasion of CD133+ OS cells and suppresses metastasis in combination with chemotherapy | [38] |

| lncRNA HIF2PUT | HIF-2α | Reduces CD133+ cells and impairs sphere-forming in OS cells | [39] |

| Metformin | AMPK/mTOR signaling alteration | Reduces sphere-forming ability and sensitizes OS cells to chemotherapeutic agents | [40, 41] |

| Bufalin | miR-148a/DNMT1/CDKN1B | Inhibits differentiation and proliferation of OS-sarcospheres | [42, 43] |

| Salinomycin | WNT signaling downregulation | Reduces sphere-formation and tumor-initiation ability of OS cells and sensitizes them to chemotherapeutic drugs | [44] |

| Salinomycin-loaded nanoparticles | — | When combined with CD133 aptamers selectively targets OS-CD133+ cells | [45] |

| Diallyl trisulfide | Upregulation of tumor-suppressive miRNAs/inhibition of NOTCH1 signaling/downregulation of ABCB1 | Prevents invasion, angiogenesis, and drug resistance in OS cells and in combination with methotrexate reduces OS-CD133+ cells | [46, 47] |

| MC1742/MC2625 | Histone deacetylase inhibition | Induces apoptosis and promotes differentiation of sarcoma CSCs | [48] |

| Vorinostat | Histone deacetylase inhibition | Reduces metastatic potential of OS cells | [49] |

| Anti-CD47 antibody | Increased macrophage phagocytosis | Inhibits invasion and metastasis of OS cells | [50] |

CDK6: cyclin-dependent kinase 6; IL6: interleukin 6; TGF-β: transforming growth factor β; YB-1: Y box-binding protein 1; HIF-2α: hypoxia inducible factors 2α; AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase; mTOR: mechanistic target of rapamycin; DNMT1: DNA (cytosine-5-)-methyltransferase 1; CDKN1B: cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B; WNT: wingless-type MMTV integration site family; ABCB1: ATP-binding cassette subfamily B member 1.

Broad genomic, metabolomic, and proteomic analyses have been useful to better characterize OS-CSC and therefore define potential OS-CSC-specific therapeutic targets with molecular rationale [58, 127, 128]. Among the reported altered signaling pathways with therapeutic implications, nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) is activated in radioresistant subpopulations of OS cell lines, and these subpopulations could be sensitized to radiation by parthenolide, an inactivator of NF-κB [129]. Another NF-κB inhibitor, BRM270, specifically targeted a multidrug resistant OS stem-like cell population by increasing their apoptosis rate and thereby reducing tumorigenic potential [130]. Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) is also an interesting therapeutic target due to its high mutation frequency and its role in regulation of proliferation, cell cycling, survival, and apoptosis. BYL719, a specific PI3Kα inhibitor, induces cell cycle arrest and inhibition of cell migration in OS cells, and, therefore, has been postulated to be useful for multidrug therapeutic approaches [35]. Moreover, another PI3K inhibitor, LY294002, induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in OS-CSC [131].

Developmental signaling pathways like WNT and NOTCH, which are highly involved in the regulation of stemness and differentiation, have also been reported to play a role in OS development [2, 37, 70]. In OS cell lines, the inactivation of NOTCH and WNT pathways resulted in sensitization to chemotherapeutic drugs [36]. In addition, aberrant active WNT/β-catenin signaling has been described in the OS-CSC population and has been associated with SOX2 overexpression and tumorigenicity [38, 132]. On the other hand, the WNT-antagonist Dickkopf proteins 1 (DKK1) has been proposed to enhance protumorigenic properties in OS, in part, through the upregulation of the stress response enzyme and CSC marker ALDH1A1 [133]. In this case, the inhibition of the canonical WNT pathway by DKK1 leads to the activation of noncanonical JUN-mediated WNT pathways, which mediate the induced tumorigenic effects. Likewise, NOTCH signaling has been associated with ALDH activity and increased metastatic potential in OS cells [39]. Therefore, a number of different therapies have been assayed to target WNT or NOTCH pathways via downregulation, inactivation, or silencing techniques [2, 37, 40] (Table 1). Interestingly, curcumin, a natural product that shows high antitumoral activity against OS cells, is a WNT/β-catenin antagonist whose antitumor activity seems to be mediated through the inactivation of NOTCH1 signaling, thereby linking both signaling pathways [41]. In addition, TGF-β is also a well-known regulator of bone biology that plays a relevant role in OS development [42]. The blocking of TGF-β signaling using the natural TGF-β/SMAD signaling inhibitor SMAD7, the inhibitor of TGF-β receptor complexes SD-208, or the natural alkaloid halofuginone hindered OS progression. These treatments reduced in vivo tumorigenic potential of OS cell lines, repressed tumor-associated bone remodeling, and inhibited the development of metastasis [43, 44]. Moreover, TGF-β signaling activation has been involved in the induction of stemness, tumorigenicity, metastatic potential, and chemoresistance in nonstem OS cells, and, conversely, the blocking of this signaling resulted in the inhibition of this dedifferentiation process of nonstem cell populations, thereby highlighting TGF-β as a potential therapeutic target [45].

Not surprisingly, microRNAs (miRNAs) are extensively related to OS development [46]. In a CSC context, a list of 189 miRNAs that are differentially expressed in OS-CSC has been reported [127]. Some of these miRNAs, such as miR-382 and miR-29b-1, were significantly decreased in human OS and their overexpression resulted in a decrease in CSC properties, metastatic potential, or chemoresistance, thus suggesting that these miRNAs could constitute novel therapeutic strategies to target OS-CSC [47, 48]. On the other hand, high levels of miR-133a and CD133 correlated with poor prognosis in OS and the inhibition of miR-133a associated with chemotherapy suppressed lung metastasis and prolonged survival in preclinical models of OS [49]. Moreover, other miRNAs like miR-215 and miR-140 have also been related to OS chemoresistance [50, 134]. In addition, a recent report shows that the overexpression of the novel long noncoding RNA HIF2PUT, involved in the regulation of HIF-2α expression, markedly inhibited proliferation, migration, and stem cell features in OS cells, thus providing a proof of principle for testing HIF2PUT in future therapeutic strategies [135].

Several natural compounds with reported antitumoral activity in OS have recently been shown to demonstrate specific inhibitory effects in OS-CSC (Table 2). Thus, besides inhibiting proliferation, invasion, and metastatic potential in OS cells, the hypoglycemic agent metformin also induces a marked reduction of the self-renewal and differentiation potential of CSC subpopulations and sensitizes OS cell to cisplatin [136, 137]. In a similar way, bufalin inhibits the differentiation and proliferation of OS-CSC through a mechanism regulated by miR-148a [138, 139]. Also, the polyether ionophore antibiotic salinomycin has demonstrated specific antitumoral activity against OS-CSC [140]. Moreover, salinomycin-loaded nanoparticles conjugated with CD133 aptamers highly increase the therapeutic effect of the drug on CD133+ OS-CSC [141]. Another natural derivative with reported antitumoral activity in OS is diallyl trisulfide, which can reverse drug resistance through the downregulation of ABCB1, and, in combination with methotrexate, is able to reduce the CD133+ subpopulation of drug resistant human OS cells [142]. Antitumoral effects of diallyl trisulfide seem to be mediated by the upregulation of tumor-suppressive miRNAs associated with an inhibition of NOTCH1 signaling [143]. Additionally, several histone deacetylase inhibitors have demonstrated antitumoral activity in OS, including the induction of differentiation in OS-CSC and the reduction of the metastatic potential [144, 145].

Finally, immunotherapy is an attractive option to target CSC subpopulations. Thus, the treatment of human OS cell lines with T cells expressing a specific chimeric antigen to target the human epidermal growth factor receptor ERBB2 was able to efficiently decrease the sarcosphere formation capacity and the ability to generate OS in vivo, suggesting that this immune-based strategy is able to target CSC subpopulations [125]. In addition, the membrane receptor CD47, which plays an important role in the mechanisms of tumor immune escape, has been found overexpressed in OS samples and highly expressed in cell subpopulations expressing the CSC marker CD44. Notably, the blockade of CD47 by specific antibodies suppressed the invasive ability and the metastatic potential of OS cells, suggesting a potential use for these anti-CD47 antibodies in the treatment of OS [146].

It is important to mention that CSC subpopulations are heterogeneous and different subpopulations may exist within a tumor with different genetic alterations. Moreover, these subpopulations are highly dynamic and there are processes of dedifferentiation and phenotype switching which may render CSC resistant to a specific CSC therapy [147]. In this regard, future therapies should combine different treatments to target both non-CSCs and CSCs, and those CSC-specific treatments should target multiple pathways altered in different subsets of CSCs within the tumor. These broader spectrum therapeutic approaches include immune-based treatments and/or therapy targeting tumor microenvironment. In addition, inhibition of transcription factors presenting altered activity offers a promising choice since they are pivotal points in signaling pathways and therefore their inhibition may block several routes involved in tumor progression. In this regard, inhibition of SP1 was able to eliminate CSCs in soft tissue sarcoma models [148].

6. Conclusions

In the most likely scenario, OS development is initiated by different cell types along the mesenchymal-osteogenic lineage targeted with relevant oncogenic lesions, like the inactivation of the tumor suppressor genes P53 and RB, and highly influenced by bone microenvironment signals. During tumor evolution, CSC subpopulations emerge after the accumulation of further epigenetic and/or genetic alterations in a subset of tumor cells. During the past decades, chemotherapy for treatment of OS has improved the overall survival for patients significantly. However, despite impressive advances, there are very little novel therapeutic agents that target tumors which are metastatic or refractory to current chemotherapy, creating a real need for the development of more biologically focused treatment regimens. OS represent a heterogeneous type of tumors, for which broader spectrum therapeutic approaches should be proposed. These strategies may include combined targeted therapies, immune-based treatments, and/or therapy targeting tumor microenvironment. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of OS-CSCs, which have been associated with chemoresistance, relapse, and metastasis events. More research aimed towards the characterization of CSC biology and evolution during tumor progression is needed to develop powerful methods of detection and efficient therapies. Targeting the tumor OS-CSCs or disrupting the interaction between OS-CSCs and their bone niche also constitutes a valuable approach, with promising clinical trials ongoing that could yield exciting new therapies for the future.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Plan Nacional 2008–2011 (ISC III/FEDER (Miguel Servet Program CP11/00024) and RTICC (RD12/0036/0015)), the Plan Nacional 2013–2016 (MINECO/FEDER (SAF-2013-42946-R)), and the Plan de Ciencia Tecnología e Innovación del Principado de Asturias (GRUPIN14-003), to Rene Rodriguez, and the Plan Nacional 2008–2011 (ISC III/FEDER (PI11/00377) and RTICC (RD12/0036/0027)), to Javier Garcia-Castro.

Competing Interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Authors' Contributions

Ander Abarrategi, Juan Tornin, Lucia Martinez-Cruzado, Ashley Hamilton, and Enrique Martinez-Campos contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Rosenberg A. E., Cleton-Jansen A. M., de Pinieux G., et al. Conventional osteosarcoma. In: Fletcher C. D. M., Bridge J. A., Hogendoorn P. C. W., Mertens F., editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. 4th. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. pp. 282–288. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alfranca A., Martinez-Cruzado L., Tornin J., et al. Bone microenvironment signals in osteosarcoma development. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2015;72(16):3097–3113. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-1918-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Botter S. M., Neri D., Fuchs B. Recent advances in osteosarcoma. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2014;16(1):15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allison D. C., Carney S. C., Ahlmann E. R., et al. A meta-analysis of osteosarcoma outcomes in the modern medical era. Sarcoma. 2012;2012:10. doi: 10.1155/2012/704872.704872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ng A. J., Mutsaers A. J., Baker E. K., Walkley C. R. Genetically engineered mouse models and human osteosarcoma. Clinical Sarcoma Research. 2012;2(1, article 19) doi: 10.1186/2045-3329-2-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang N., Song W.-X., Luo J., Haydon R. C., He T.-C. Osteosarcoma development and stem cell differentiation. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2008;466(9):2114–2130. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0335-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones K. B. Osteosarcomagenesis: modeling cancer initiation in the mouse. Sarcoma. 2011;2011:10. doi: 10.1155/2011/694136.694136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malkin D., Jolly K. W., Barbier N., et al. Germline mutations of the p53 tumor-suppressor gene in children and young adults with second malignant neoplasms. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1992;326(20):1309–1315. doi: 10.1056/nejm199205143262002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong F. L., Boice J. D., Jr., Abramson D. H., et al. Cancer incidence after retinoblastoma: radiation dose and sarcoma risk. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278(15):1262–1267. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03550150066037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Overholtzer M., Rao P. H., Favis R., et al. The presence of p53 mutations in human osteosarcomas correlates with high levels of genomic instability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(20):11547–11552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934852100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wadayama B.-I., Toguchida J., Shimizu T., et al. Mutation spectrum of the retinoblastoma gene in osteosarcomas. Cancer Research. 1994;54(11):3042–3048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodriguez R., Rubio R., Menendez P. Modeling sarcomagenesis using multipotent mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Research. 2012;22(1):62–77. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berman S. D., Calo E., Landman A. S., et al. Metastatic osteosarcoma induced by inactivation of Rb and p53 in the osteoblast lineage. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(33):11851–11856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805462105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin P. P., Pandey M. K., Jin F., Raymond A. K., Akiyama H., Lozano G. Targeted mutation of p53 and Rb in mesenchymal cells of the limb bud produces sarcomas in mice. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(10):1789–1795. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walkley C. R., Qudsi R., Sankaran V. G., et al. Conditional mouse osteosarcoma, dependent on p53 loss and potentiated by loss of Rb, mimics the human disease. Genes and Development. 2008;22(12):1662–1676. doi: 10.1101/gad.1656808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calo E., Quintero-Estades J. A., Danielian P. S., Nedelcu S., Berman S. D., Lees J. A. Rb regulates fate choice and lineage commitment in vivo. Nature. 2010;466(7310):1110–1114. doi: 10.1038/nature09264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benassi M. S., Molendini L., Gamberi G., et al. Alteration of prb/p16/cdk4 regulation in human osteosarcoma. International Journal of Cancer. 1999;84(5):489–493. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19991022)84:560;489::aid-ijc760;3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.López-Guerrero J. A., López-Ginés C., Pellín A., Carda C., Llombart-Bosch A. Deregulation of the G1 to S-phase cell cycle checkpoint is involved in the pathogenesis of human osteosarcoma. Diagnostic Molecular Pathology. 2004;13(2):81–91. doi: 10.1097/00019606-200406000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maelandsmo G. M., Berner J.-M., Florenes V. A., et al. Homozygous deletion frequency and expression levels of the CDKN2 gene in human sarcomas—relationship to amplification and mRNA levels of CDK4 and CCND1 . British Journal of Cancer. 1995;72(2):393–398. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y., Xiong Y., Yarbrough W. G. ARF promotes MDM2 degradation and stabilizes p53: ARF-INK4a locus deletion impairs both the Rb and p53 tumor suppression pathways. Cell. 1998;92(6):725–734. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lonardo F., Ueda T., Huvos A. G., Healey J., Ladanyi M. p53 and MDM2 alterations in osteosarcomas: correlation with clinicopathologic features and proliferative rate. Cancer. 1997;79(8):1541–1547. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970415)79:8<1541::aid-cncr15>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ladanyi M., Cha C., Lewis R., Jhanwar S. C., Huvos A. G., Healey J. H. MDM2 gene amplification in metastatic osteosarcoma. Cancer Research. 1993;53(1):16–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lockwood W. W., Stack D., Morris T., et al. Cyclin E1 is amplified and overexpressed in osteosarcoma. Journal of Molecular Diagnostics. 2011;13(3):289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gamberi G., Benassi M. S., Bohling T., et al. C-myc and c-fos in human osteosarcoma: prognostic value of mRNA and protein expression. Oncology. 1998;55(6):556–563. doi: 10.1159/000011912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papachristou D. J., Batistatou A., Sykiotis G. P., Varakis I., Papavassiliou A. G. Activation of the JNK-AP-1 signal transduction pathway is associated with pathogenesis and progression of human osteosarcomas. Bone. 2003;32(4):364–371. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(03)00026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu J.-X., Carpenter P. M., Gresens C., et al. The proto-oncogene c-fos is over-expressed in the majority of human osteosarcomas. Oncogene. 1990;5(7):989–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Z.-Q., Liang J., Schellander K., Wagner E. F., Grigoriadis A. E. c-fos-induced osteosarcoma formation in transgenic mice: cooperativity with c-jun and the role of endogenous c-fos. Cancer Research. 1995;55(24):6244–6251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smida J., Baumhoer D., Rosemann M., et al. Genomic alterations and allelic imbalances are strong prognostic predictors in osteosarcoma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;16(16):4256–4267. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ueda T., Healey J. H., Huvos A. G., Ladanyi M. Amplification of the MYC gene in osteosarcoma secondary to Paget's disease of bone. Sarcoma. 1997;1(3-4):131–134. doi: 10.1080/13577149778209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scionti I., Michelacci F., Pasello M., et al. Clinical impact of the methotrexate resistance-associated genes C-MYC and dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) in high-grade osteosarcoma. Annals of Oncology. 2008;19(8):1500–1508. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lamoureux F., Picarda G., Rousseau J., et al. Therapeutic efficacy of soluble receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB-Fc delivered by nonviral gene transfer in a mouse model of osteolytic osteosarcoma. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2008;7(10):3389–3398. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.mct-08-0497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lamoureux F., Richard P., Wittrant Y., et al. Therapeutic relevance of osteoprotegerin gene therapy in osteosarcoma: blockade of the vicious cycle between tumor cell proliferation and bone resorption. Cancer Research. 2007;67(15):7308–7318. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-06-4130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moriceau G., Ory B., Gobin B., et al. Therapeutic approach of primary bone tumours by bisphosphonates. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2010;16(27):2981–2987. doi: 10.2174/138161210793563554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quan G. M. Y., Choong P. F. M. Anti-angiogenic therapy for osteosarcoma. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2006;25(4):707–713. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-9031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gobin B., Huin M. B., Lamoureux F., et al. BYL719, a new α-specific PI3K inhibitor: single administration and in combination with conventional chemotherapy for the treatment of osteosarcoma. International Journal of Cancer. 2015;136(4):784–796. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma Y., Ren Y., Han E. Q., et al. Inhibition of the Wnt-β-catenin and Notch signaling pathways sensitizes osteosarcoma cells to chemotherapy. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2013;431(2):274–279. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.12.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McQueen P., Ghaffar S., Guo Y., Rubin E. M., Zi X., Hoang B. H. The Wnt signaling pathway: implications for therapy in osteosarcoma. Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy. 2011;11(8):1223–1232. doi: 10.1586/era.11.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martins-Neves S. R., Corver W. E., Paiva-Oliveira D. I., et al. Osteosarcoma stem cells have active Wnt/β-catenin and overexpress SOX2 and KLF4. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2016;231(4):876–886. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mu X., Isaac C., Greco N., Huard J., Weiss K. Notch signaling is associated with ALDH activity and an aggressive metastatic phenotype in murine osteosarcoma cells. Frontiers in Oncology. 2013;3, article 143 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cai Y., Cai T., Chen Y. Wnt pathway in osteosarcoma, from oncogenic to therapeutic. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2014;115(4):625–631. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Y., Zhang J., Ma D., et al. Curcumin inhibits proliferation and invasion of osteosarcoma cells through inactivation of Notch-1 signaling. The FEBS Journal. 2012;279(12):2247–2259. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen G., Deng C., Li Y.-P. TGF-β and BMP signaling in osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2012;8(2):272–288. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.2929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lamora A., Mullard M., Amiaud J., et al. Anticancer activity of halofuginone in a preclinical model of osteosarcoma: inhibition of tumor growth and lung metastases. Oncotarget. 2015;6(16):14413–14427. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lamora A., Talbot J., Bougras G., et al. Overexpression of Smad7 blocks primary tumor growth and lung metastasis development in osteosarcoma. Clinical Cancer Research. 2014;20(19):5097–5112. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang H., Wu H., Zheng J., et al. Transforming growth factor β1 signal is crucial for dedifferentiation of cancer cells to cancer stem cells in osteosarcoma. STEM CELLS. 2013;31(3):433–446. doi: 10.1002/stem.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kobayashi E., Hornicek F. J., Duan Z. MicroRNA involvement in osteosarcoma. Sarcoma. 2012;2012:8. doi: 10.1155/2012/359739.359739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Di Fiore R., Drago-Ferrante R., Pentimali F., et al. MicroRNA-29b-1 impairs in vitro cell proliferation, self-renewal and chemoresistance of human osteosarcoma 3AB-OS cancer stem cells. International Journal of Oncology. 2014;45(5):2013–2023. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu M., Jin H., Xu C.-X., et al. miR-382 inhibits osteosarcoma metastasis and relapse by targeting y box-binding protein 1. Molecular Therapy. 2015;23(1):89–98. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fujiwara T., Katsuda T., Hagiwara K., et al. Clinical relevance and therapeutic significance of microRNA-133a expression profiles and functions in malignant osteosarcoma-initiating cells. Stem Cells. 2014;32(4):959–973. doi: 10.1002/stem.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Song B., Wang Y., Titmus M. A., et al. Molecular mechanism of chemoresistance by miR-215 in osteosarcoma and colon cancer cells. Molecular Cancer. 2010;9, article 96 doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moriarity B. S., Otto G. M., Rahrmann E. P., et al. A Sleeping Beauty forward genetic screen identifies new genes and pathways driving osteosarcoma development and metastasis. Nature Genetics. 2015;47(6):615–624. doi: 10.1038/ng.3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kovac M., Blattmann C., Ribi S., et al. Exome sequencing of osteosarcoma reveals mutation signatures reminiscent of BRCA deficiency. Nature Communications. 2015;6, article 8940 doi: 10.1038/ncomms9940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuijjer M. L., Rydbeck H., Kresse S. H., et al. Identification of osteosarcoma driver genes by integrative analysis of copy number and gene expression data. Genes Chromosomes and Cancer. 2012;51(7):696–706. doi: 10.1002/gcc.21956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ou M., Cai W.-W., Zender L., et al. MMP13, Birc2 (clAP1), and Birc3 (clAP2), amplified on chromosome 9, collaborate with p53 deficiency in mouse osteosarcoma progression. Cancer Research. 2009;69(6):2559–2567. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xiong Y., Wu S., Du Q., Wang A., Wang Z. Integrated analysis of gene expression and genomic aberration data in osteosarcoma (OS) Cancer Gene Therapy. 2015;22(11):524–529. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2015.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Entz-Werle N., Lavaux T., Metzger N., et al. Involvement of MET/TWIST/APC combination or the potential role of ossification factors in pediatric high-grade osteosarcoma oncogenesis. Neoplasia. 2007;9(8):678–688. doi: 10.1593/neo.07367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen X., Bahrami A., Pappo A., et al. Recurrent somatic structural variations contribute to tumorigenesis in pediatric osteosarcoma. Cell Reports. 2014;7(1):104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kansara M., Teng M. W., Smyth M. J., Thomas D. M. Translational biology of osteosarcoma. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2014;14(11):722–735. doi: 10.1038/nrc3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mendoza S., David H., Gaylord G. M., Miller C. W. Allelic loss at 10q26 in osteosarcoma in the region of the BUB3 and FGFR2 genes. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 2005;158(2):142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2004.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rao-Bindal K., Kleinerman E. S. Epigenetic regulation of apoptosis and cell cycle in osteosarcoma. Sarcoma. 2011;2011:5. doi: 10.1155/2011/679457.679457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang L. L., Gannavarapu A., Kozinetz C. A., et al. Association between osteosarcoma and deleterious mutations in the RECQL4 gene Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2003;95(9):669–674. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.9.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Visvader J. E. Cells of origin in cancer. Nature. 2011;469(7330):314–322. doi: 10.1038/nature09781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mutsaers A. J., Walkley C. R. Cells of origin in osteosarcoma: mesenchymal stem cells or osteoblast committed cells? Bone. 2014;62:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xiao W., Mohseny A. B., Hogendoorn P. C., Cleton-Jansen A. M. Mesenchymal stem cell transformation and sarcoma genesis. Clinical Sarcoma Research. 2013;3(1, article 10) doi: 10.1186/2045-3329-3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rodríguez R., García-Castro J., Trigueros C., García Arranz M., Menéndez P. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells: clinical applications and cancer modeling. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2012;741:187–205. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-2098-9_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rodriguez R., Tornin J., Suarez C., et al. Expression of FUS-CHOP fusion protein in immortalized/transformed human mesenchymal stem cells drives mixoid liposarcoma formation. Stem Cells. 2013;31(10):2061–2072. doi: 10.1002/stem.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mutsaers A. J., Ng A. J. M., Baker E. K., et al. Modeling distinct osteosarcoma subtypes in vivo using Cre:lox and lineage-restricted transgenic shRNA. Bone. 2013;55(1):166–178. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Molyneux S. D., Di Grappa M. A., Beristain A. G., et al. Prkar1a is an osteosarcoma tumor suppressor that defines a molecular subclass in mice. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2010;120(9):3310–3325. doi: 10.1172/jci42391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sottnik J. L., Campbell B., Mehra R., Behbahani-Nejad O., Hall C. L., Keller E. T. Osteocytes serve as a progenitor cell of osteosarcoma. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2014;115(8):1420–1429. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tao J., Jiang M.-M., Jiang L., et al. Notch activation as a driver of osteogenic sarcoma. Cancer Cell. 2014;26(3):390–401. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chan L. H., Wang W., Yeung W., Deng Y., Yuan P., Mak K. K. Hedgehog signaling induces osteosarcoma development through Yap1 and H19 overexpression. Oncogene. 2014;33(40):4857–4866. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Quist T., Jin H., Zhu J.-F., Smith-Fry K., Capecchi M. R., Jones K. B. The impact of osteoblastic differentiation on osteosarcomagenesis in the mouse. Oncogene. 2015;34(32):4278–4284. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rubio R., García-Castro J., Gutiérrez-Aranda I., et al. Deficiency in p53 but not retinoblastoma induces the transformation of mesenchymal stem cells in vitro and initiates leiomyosarcoma in vivo . Cancer Research. 2010;70(10):4185–4194. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-09-4640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rubio R., Gutierrez-Aranda I., Sáez-Castillo A. I., et al. The differentiation stage of p53-Rb-deficient bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells imposes the phenotype of in vivo sarcoma development. Oncogene. 2013;32(41):4970–4980. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rubio R., Abarrategi A., Garcia-Castro J., et al. Bone environment is essential for osteosarcoma development from transformed mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2014;32(5):1136–1148. doi: 10.1002/stem.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mohseny A. B., Szuhai K., Romeo S., et al. Osteosarcoma originates from mesenchymal stem cells in consequence of aneuploidization and genomic loss of Cdkn2. The Journal of Pathology. 2009;219(3):294–305. doi: 10.1002/path.2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shimizu T., Ishikawa T., Sugihara E., et al. C-MYC overexpression with loss of Ink4a/Arf transforms bone marrow stromal cells into osteosarcoma accompanied by loss of adipogenesis. Oncogene. 2010;29(42):5687–5699. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cleton-Jansen A.-M., Anninga J. K., Briaire-de Bruijn I. H., et al. Profiling of high-grade central osteosarcoma and its putative progenitor cells identifies tumourigenic pathways. British Journal of Cancer. 2009;101(11):1909–1918. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lemos D. R., Eisner C., Hopkins C. I., Rossi F. M. V. Skeletal muscle-resident MSCs and bone formation. Bone. 2015;80:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kaplan F. S., Chakkalakal S. A., Shore E. M. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: mechanisms and models of skeletal metamorphosis. Disease Models and Mechanisms. 2012;5(6):756–762. doi: 10.1242/dmm.010280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Basu-Roy U., Basilico C., Mansukhani A. Perspectives on cancer stem cells in osteosarcoma. Cancer Letters. 2013;338(1):158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dela Cruz F. S. Cancer stem cells in pediatric sarcomas. Frontiers in Oncology. 2013;3, article 168 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu B., Ma W., Jha R. K., Gurung K. Cancer stem cells in osteosarcoma: recent progress and perspective. Acta Oncologica. 2011;50(8):1142–1150. doi: 10.3109/0284186x.2011.584553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Siclari V. A., Qin L. Targeting the osteosarcoma cancer stem cell. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research. 2010;5(1, article 78) doi: 10.1186/1749-799x-5-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tirino V., Desiderio V., Paino F., et al. Cancer stem cells in solid tumors: an overview and new approaches for their isolation and characterization. The FASEB Journal. 2013;27(1):13–24. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-218222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gibbs C. P., Kukekov V. G., Reith J. D., et al. Stem-like cells in bone sarcomas: implications for tumorigenesis. Neoplasia. 2005;7(11):967–976. doi: 10.1593/neo.05394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang L., Park P., Lin C.-Y. Characterization of stem cell attributes in human osteosarcoma cell lines. Cancer Biology and Therapy. 2009;8(6):543–552. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.6.7695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wilson H., Huelsmeyer M., Chun R., Young K. M., Friedrichs K., Argyle D. J. Isolation and characterisation of cancer stem cells from canine osteosarcoma. Veterinary Journal. 2008;175(1):69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Salerno M., Avnet S., Bonuccelli G., et al. Sphere-forming cell subsets with cancer stem cell properties in human musculoskeletal sarcomas. International Journal of Oncology. 2013;43(1):95–102. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.He A., Yang X., Huang Y., et al. CD133+CD+ cells mediate in the lung metastasis of osteosarcoma. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2015;116(8):1719–1729. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Li J., Zhong X.-Y., Li Z.-Y., et al. CD133 expression in osteosarcoma and derivation of CD133+ cells. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2013;7(2):577–584. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tirino V., Desiderio V., Paino F., et al. Human primary bone sarcomas contain CD133+ cancer stem cells displaying high tumorigenicity in vivo. FASEB Journal. 2011;25(6):2022–2030. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-179036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Adhikari A. S., Agarwal N., Wood B. M., et al. CD117 and Stro-1 identify osteosarcoma tumor-initiating cells associated with metastasis and drug resistance. Cancer Research. 2010;70(11):4602–4612. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tian J., Li X., Si M., Liu T., Li J. CD271+ osteosarcoma cells display stem-like properties. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(6, article e98549) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Murase M., Kano M., Tsukahara T., et al. Side population cells have the characteristics of cancer stem-like cells/cancer-initiating cells in bone sarcomas. British Journal of Cancer. 2009;101(8):1425–1432. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sun D.-X., Liao G.-J., Liu K.-G., Jian H. Endosialin-expressing bone sarcoma stem-like cells are highly tumor-initiating and invasive. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2015;12(4):5665–5670. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Honoki K., Fujii H., Kubo A., et al. Possible involvement of stem-like populations with elevated ALDH1 in sarcomas for chemotherapeutic drug resistance. Oncology Reports. 2010;24(2):501–505. doi: 10.3892/or-00000885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wang L., Park P., Zhang H., La Marca F., Lin C.-Y. Prospective identification of tumorigenic osteosarcoma cancer stem cells in OS99-1 cells based on high aldehyde dehydrogenase activity. International Journal of Cancer. 2011;128(2):294–303. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Levings P. P., McGarry S. V., Currie T. P., et al. Expression of an exogenous human Oct-4 promoter identifies tumor-initiating cells in osteosarcoma. Cancer Research. 2009;69(14):5648–5655. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yu L., Liu S., Guo W., et al. hTERT promoter activity identifies osteosarcoma cells with increased EMT characteristics. Oncology Letters. 2014;7(1):239–244. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yu L., Liu S., Zhang C., et al. Enrichment of human osteosarcoma stem cells based on hTERT transcriptional activity. Oncotarget. 2013;4(12):2326–2338. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Di Fiore R., Santulli A., Ferrante R. D., et al. Identification and expansion of human osteosarcoma-cancer-stem cells by long-term 3-aminobenzamide treatment. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2009;219(2):301–313. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tang Q.-L., Liang Y., Xie X.-B., et al. Enrichment of osteosarcoma stem cells by chemotherapy. Chinese Journal of Cancer. 2011;30(6):426–432. doi: 10.5732/cjc.011.10127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Naka N., Takenaka S., Araki N., et al. Synovial sarcoma is a stem cell malignancy. Stem Cells. 2010;28(7):1119–1131. doi: 10.1002/stem.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fujii H., Honoki K., Tsujiuchi T., Kido A., Yoshitani K., Takakura Y. Sphere-forming stem-like cell populations with drug resistance in human sarcoma cell lines. International Journal of Oncology. 2009;34(5):1381–1386. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yan G.-N., Lv Y.-F., Guo Q.-N. Advances in osteosarcoma stem cell research and opportunities for novel therapeutic targets. Cancer Letters. 2016;370(2):268–274. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Basu-Roy U., Seo E., Ramanathapuram L., et al. Sox2 maintains self renewal of tumor-initiating cells in osteosarcomas. Oncogene. 2012;31(18):2270–2282. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Salerno M., Avnet S., Bonuccelli G., Hosogi S., Granchi D., Baldini N. Impairment of lysosomal activity as a therapeutic modality targeting cancer stem cells of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma cell line RD. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110340.e110340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.He H., Ni J., Huang J. Molecular mechanisms of chemoresistance in osteosarcoma (Review) Oncology Letters. 2014;7(5):1352–1362. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Martins-Neves S. R., Lopes Á. O., do Carmo A., et al. Therapeutic implications of an enriched cancer stem-like cell population in a human osteosarcoma cell line. BMC Cancer. 2012;12, article 139 doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yang M., Yan M., Zhang R., Li J., Luo Z. Side population cells isolated from human osteosarcoma are enriched with tumor-initiating cells. Cancer Science. 2011;102(10):1774–1781. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02028.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gonçalves C., Martins-Neves S. R., Paiva-Oliveira D., Oliveira V. E. B., Fontes-Ribeiro C., Gomes C. M. F. Sensitizing osteosarcoma stem cells to doxorubicin-induced apoptosis through retention of doxorubicin and modulation of apoptotic-related proteins. Life Sciences. 2015;130:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Plaks V., Kong N., Werb Z. The cancer stem cell niche: how essential is the niche in regulating stemness of tumor cells? Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16(3):225–238. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kuhn N. Z., Tuan R. S. Regulation of stemness and stem cell niche of mesenchymal stem cells: implications in tumorigenesis and metastasis. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2010;222(2):268–277. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zeng W., Wan R., Zheng Y., Singh S. R., Wei Y. Hypoxia, stem cells and bone tumor. Cancer Letters. 2011;313(2):129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Boyce B. F., Xing L. Functions of RANKL/RANK/OPG in bone modeling and remodeling. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2008;473(2):139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Choong P. F. M., Broadhead M. L., Clark J. C. M., Myers D. E., Dass C. R. The molecular pathogenesis of osteosarcoma: a review. Sarcoma. 2011;2011:12. doi: 10.1155/2011/959248.959248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Harwood J. L., Alexander J. H., Mayerson J. L., Scharschmidt T. J. Targeted chemotherapy in bone and soft-tissue sarcoma. Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 2015;46(4):587–608. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hattinger C. M., Fanelli M., Tavanti E., et al. Advances in emerging drugs for osteosarcoma. Expert Opinion on Emerging Drugs. 2015;20(3):495–514. doi: 10.1517/14728214.2015.1051965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Heymann D., Rédini F. Targeted therapies for bone sarcomas. Bonekey Reports. 2013;2, article 378 doi: 10.1038/bonekey.2013.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Cathomas R., Rothermundt C., Bode B., Fuchs B., Von Moos R., Schwitter M. RANK ligand blockade with denosumab in combination with sorafenib in chemorefractory osteosarcoma: a possible step forward? Oncology. 2014;88(4):257–260. doi: 10.1159/000369975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sampson V. B., Gorlick R., Kamara D., Anders Kolb E. A review of targeted therapies evaluated by the pediatric preclinical testing program for osteosarcoma. Frontiers in Oncology. 2013;3, article 132 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.DeRenzo C., Gottschalk S. Genetically modified T-cell therapy for osteosarcoma. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2014;804:323–340. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-04843-7_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kawano M., Itonaga I., Iwasaki T., Tsuchiya H., Tsumura H. Anti-TGF-β antibody combined with dendritic cells produce antitumor effects in osteosarcoma. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2012;470(8):2288–2294. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2299-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Rainusso N., Brawley V. S., Ghazi A., et al. Immunotherapy targeting HER2 with genetically modified T cells eliminates tumor-initiating cells in osteosarcoma. Cancer Gene Therapy. 2012;19(3):212–217. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2011.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Tarek N., Lee D. A. Natural killer cells for osteosarcoma. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2014;804:341–353. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-04843-7_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Di Fiore R., Fanale D., Drago-Ferrante R., et al. Genetic and molecular characterization of the human osteosarcoma 3AB-OS cancer stem cell line: a possible model for studying osteosarcoma origin and stemness. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2013;228(6):1189–1201. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Gemei M., Corbo C., D'Alessio F., Di Noto R., Vento R., Del Vecchio L. Surface proteomic analysis of differentiated versus stem-like osteosarcoma human cells. Proteomics. 2013;13(22):3293–3297. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201300170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Zuch D., Giang A.-H., Shapovalov Y., et al. Targeting radioresistant osteosarcoma cells with parthenolide. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2012;113(4):1282–1291. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Mongre R. K., Sodhi S. S., Ghosh M., et al. The novel inhibitor BRM270 downregulates tumorigenesis by suppression of NF-κB signaling cascade in MDR-induced stem like cancer-initiating cells. International Journal of Oncology. 2015;46(6):2573–2585. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2015.2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Gong C., Liao H., Wang J., et al. LY294002 induces G0/G1 cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of cancer stem-like cells from human osteosarcoma via downregulation of PI3K activity. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2012;13(7):3103–3107. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.7.3103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Yi X.-J., Zhao Y.-H., Qiao L.-X., Jin C.-L., Tian J., Li Q.-S. Aberrant Wnt/β-catenin signaling and elevated expression of stem cell proteins are associated with osteosarcoma side population cells of high tumorigenicity. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2015;12(4):5042–5048. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.4025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Krause U., Ryan D. M., Clough B. H., Gregory C. A. An unexpected role for a Wnt-inhibitor: Dickkopf-1 triggers a novel cancer survival mechanism through modulation of aldehyde-dehydrogenase-1 activity. Cell Death and Disease. 2014;5(2) doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.67.e1093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Song B., Wang Y., Xi Y., et al. Mechanism of chemoresistance mediated by miR-140 in human osteosarcoma and colon cancer cells. Oncogene. 2009;28(46):4065–4074. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Wang Y., Yao J., Meng H., et al. A novel long non-coding RNA, hypoxia-inducible factor-2α promoter upstream transcript, functions as an inhibitor of osteosarcoma stem cells in vitro. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2015;11(4):2534–2540. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Chen X., Hu C., Zhang W., et al. Metformin inhibits the proliferation, metastasis, and cancer stem-like sphere formation in osteosarcoma MG63 cells in vitro. Tumor Biology. 2015;36(12):9873–9883. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3751-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Quattrini I., Conti A., Pazzaglia L., et al. Metformin inhibits growth and sensitizes osteosarcoma cell lines to cisplatin through cell cycle modulation. Oncology Reports. 2014;31(1):370–375. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Chang Y., Zhao Y., Gu W., et al. Bufalin inhibits the differentiation and proliferation of cancer stem cells derived from primary osteosarcoma cells through Mir-148a. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2015;36(3):1186–1196. doi: 10.1159/000430289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Chang Y., Zhao Y., Zhan H., Wei X., Liu T., Zheng B. Bufalin inhibits the differentiation and proliferation of human osteosarcoma cell line hMG63-derived cancer stem cells. Tumor Biology. 2014;35(2):1075–1082. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1143-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Tang Q.-L., Zhao Z.-Q., Li J.-C., et al. Salinomycin inhibits osteosarcoma by targeting its tumor stem cells. Cancer Letters. 2011;311(1):113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Ni M., Xiong M., Zhang X., et al. Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles conjugated with CD133 aptamers for targeted salinomycin delivery to CD133+ osteosarcoma cancer stem cells. International Journal of Nanomedicine. 2015;10:2537–2554. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s78498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Li J., Liu W., Zhao K., et al. Diallyl trisulfide reverses drug resistance and lowers the ratio of CD133+ cells in conjunction with methotrexate in a human osteosarcoma drug-resistant cell subline. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2009;2(2):245–252. doi: 10.3892/mmr-00000091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Li Y., Zhang J., Zhang L., Si M., Yin H., Li J. Diallyl trisulfide inhibits proliferation, invasion and angiogenesis of osteosarcoma cells by switching on suppressor microRNAs and inactivating of Notch-1 signaling. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34(7):1601–1610. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Di Pompo G., Salerno M., Rotili D., et al. Novel histone deacetylase inhibitors induce growth arrest, apoptosis, and differentiation in sarcoma cancer stem cells. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2015;58(9):4073–4079. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Mu X., Brynien D., Weiss K. R. The HDAC inhibitor Vorinostat diminishes the in vitro metastatic behavior of Osteosarcoma cells. BioMed Research International. 2015;2015:6. doi: 10.1155/2015/290368.290368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Xu J.-F., Pan X.-H., Zhang S.-J., et al. CD47 blockade inhibits tumor progression human osteosarcoma in xenograft models. Oncotarget. 2015;6(27):23662–23670. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Vermeulen L., de Sousa e Melo F., Richel D. J., Medema J. P. The developing cancer stem-cell model: clinical challenges and opportunities. The Lancet Oncology. 2012;13(2):e83–e89. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(11)70257-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Tornin J., Martinez-Cruzado L., Santos L., et al. Inhibition of SP1 by the mithramycin analog EC-8042 efficiently targets tumor initiating cells in sarcoma. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]