Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to determine the association of the extent of metastatic lymph node involvement with survival in pancreatic cancer.

Methods

This is a retrospective review of a prospectively maintained database of patients who underwent resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma, 1999–2011.

Results

165 patients were identified and divided into 3 groups based on the number of positive lymph nodes – 0 (group A), 1–2 (B), >3 (C). Each group had 55 patients. Those in group C were more likely to have a higher T stage, poorly differentiated grade, lymphovascular invasion (LVI), higher mean intraoperative blood loss, positive margins, tumor location involving the uncinate process, and a higher likelihood of undergoing a pancreaticoduodenectomy. Median overall survival (OS) for group A, B and C was 25.5 months (mo), 21 mo and 12.3 mo, respectively (p < 0.001). No survival difference was noted for survival between groups A and B (p = 0.86). The ratio of involved lymph nodes <0.2 was predictive of improved survival (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Resected pancreatic cancer patients with only 1–2 positive lymph nodes or less than 20% involvement have a similar prognosis to patients without nodal disease. Current staging should consider stratification based on the extent of nodal involvement.

Introduction

Over the past several years there has been much debate with regards to the prognostic and clinical significance of pancreatic cancer that is metastatic to lymph nodes. In 1973, Fortner first described the regional pancreatectomy in an attempt to clear a larger area including lymphatic channels and their associated lymph nodes.1 This approach has not been embraced due to the failure to produce significantly better results over standard pancreatectomy, though some studies have reported modest benefit to extending the lymph node dissection.2

The current staging system for pancreatic cancer currently divides nodal status into a binary system, namely positive (N1) or negative nodes (N0). This is based upon multiple studies showing that any degree of lymph node positivity leads to equally adverse outcomes.3, 4, 5 More recently, there has been interest in the metastatic lymph node ratio as a prognostic indicator in pancreatic cancer.6, 7, 8, 9 It has been proposed that an increasing positive lymph node ratio provides superior prognostic information over the current staging system. Along with an increasing node ratio, an increasing absolute number of removed lymph nodes has also been reported to be associated with an improved outcome. It is unclear whether this is due to stage migration or to additional clearance of tumor bearing tissue.10, 11

The prognostic significance of positive lymph nodes and the extent to which lymph nodes should be removed during pancreatectomy needs clarification. To this end, we reviewed our experience of pancreatectomies to further delineate this issue and define the prognostic significance of metastatic lymph node involvement in pancreatic cancer.

Methods

Study population

A prospectively maintained database was reviewed for all patients who underwent pancreatectomy from 1999 to 2011 for curative intent for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Approval was obtained from the institutional review board (IRB) prior to data collection. Patients who were found to have a diagnosis other than adenocarcinoma, who underwent surgery for reasons other than curative intent (diagnostic or palliative reasons), or had carcinoma arising from outside of the pancreas were excluded. The charts and pre-operative imaging were reviewed for all of these patients to confirm collected data and to provide additional data not originally collected. Data variables included patient age, gender, tumor location (head, body, tail), tumor size, grade, morphology, type of surgery performed, estimated blood loss (EBL), vein resection and repair, number of lymph nodes removed and positive lymph nodes, margin status, T stage, N stage, perineural invasion (PNI), lymphovascular invasion (LVI), neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapies, recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS).

The technical aspects of each surgery, including whether to perform a conventional pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) or a pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPPD), were determined by each surgeon at the time of surgery. Vascular resection of the portal vein (PV) or superior mesenteric vein (SMV) was not routinely performed, but was done in select cases when required for complete resection of the tumor. Frozen section was routinely done on the pancreatic and bile duct margins. Extended regional lymphadenectomy was not performed in any of the reviewed cases.

Adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy was considered for all patients with T2 or greater tumors. Treatment was considered to be adjuvant if there was no evidence of disease after surgical resection. Treatment was considered palliative if started when radiographic evidence of residual or recurrent pancreatic cancer was demonstrated. This included residual, recurrent, or metastatic disease found on post-surgical imaging. Treatment decisions were based upon individual patient considerations including performance status, patient desire for adjuvant treatment, and the ability to tolerate treatment based on the judgment of the treating physicians. Treatment regimens and dosing were left to the discretion of the treating physician. Tumors that were considered borderline resectable at time of presentation based on location of the tumor to the PV, SMV, or superior mesenteric artery (SMA) were considered for neoadjuvant treatment.

For the purposes of discriminating between head and body/tail lesions, patients who underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy were confirmed to have head lesions while patients who underwent distal pancreatectomy were considered to have body/tail lesions. The uncinate process was defined to be the area of the head of the pancreas to the right of the line between the SMV and inferior vena cava (IVC) as has traditionally been described. Tumors were then grouped into those involving the uncinate process or those confined to the head of the pancreas only based upon pre-operative CT scans, which were done with IV contrast in both arterial and portal venous phases. For charts without pre-operative imaging available for review, operative and/or pathology reports were used to determine the location of the tumor within the specimen.

Statistical methods

Patient characteristics were reported for the overall sample and by lymph node involvement using means and standard deviations for continuous variables; and frequencies and relative frequencies for categorical variables. Comparisons were made using the Kruskal Wallis and Pearson's chi-square test for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. The survival outcomes included overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) and were summarized using standard Kaplan–Meier methods. Estimates of median survival and 1- and 3-year survival rates were obtained with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Comparisons were made using the log-rank test. Continuous variables were categorized such that the Kaplan–Meier methods could be applied. All analyses were conducted in SAS v9.3 (Cary, NC) at a significance level of 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

Between January 1999 and October 2011, a total of 165 patients who underwent pancreatectomy for adenocarcinoma were identified. Table 1 summarizes patient demographics, tumor characteristics and treatments. Median age was 65 years; 91 (55.2%) of patients were female. Seven (4.2%) patients underwent total pancreatectomy due to inability to obtain a negative margin during resection. Vascular resection and repair was required for removal of the tumor in 21 (12.7%) of resections; 6 (28.6%) of these ultimately had positive margin resections. T4 tumors were defined post-resection by positive margins with involvement of unresectable vessels.

Table 1.

Demographics for patients undergoing pancreatectomy

| Variable | Number of patients () indicate % unless otherwise specified |

|---|---|

| Median age (Range) | 65 (31–86) |

| Tumor location | |

| Head of pancreas | 95 (57.6) |

| Uncinate process | 41 (24.8) |

| Body/Tail | 29 (17.6) |

| Surgery performed | |

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 100 (60.6) |

| Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy | 33 (20.0) |

| Distal pancreatectomy | 25 (15.2) |

| Total pancreatectomy | 7 (4.2) |

| Margin status | |

| Positive | 37 (22.4) |

| Negative | 128 (77.6) |

| Vein resection | 21 (13.0) |

| T stage | |

| 1 | 8 (4.8) |

| 2 | 18 (10.9) |

| 3 | 137 (83.0) |

| 4 | 2 (1.2) |

| Tumor size average (mm) ± Standard deviation | 35.6 ± 21.9 |

| Grade | |

| Well | 9 (5.5) |

| Moderate | 77 (46.7) |

| Poor | 78 (47.2) |

| Perineural invasion | 147 (89.1) |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 66 (40.0) |

| Lymph nodes removed | |

| ≤5 | 11 (6.7) |

| 6–10 | 31 (18.8) |

| >10 | 123 (74.5) |

| Positive lymph nodes | |

| 0 | 55 (33.3) |

| 1–2 | 55 (33.3) |

| ≥3 | 55 (33.3) |

| Neoadjuvant treatment | |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 19 (11.6) |

| Chemotherapy | 2 (1.2) |

| None | 143 (87.2) |

| Adjuvant Treatment | |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 73 (45.1) |

| Chemotherapy | 28 (17.3) |

| Palliative | 10 (6.2) |

| None | 51 (31.5) |

Absolute lymph node involvement

For the purposes of this analysis, metastatic pancreatic cancer to lymph nodes was stratified into three distinct categories: group A – no lymph node involvement (n = 55, 33.3%), group B – one or two positive lymph nodes (n = 55, 33.3%), and group C – three or more positive lymph nodes, (n = 55, 33.3%). The rationale for this grouping was derived from previous studies showing that patients with 1–2 positive nodes have similar outcomes compared to patients with no nodal involvement.12, 13 Interestingly, the distribution among the three groups was identical during the study time period. There were no statistical differences between these groups for age, gender, tumor size, pre-operative Ca 19-9 level, PNI, vein resection, or administration of neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics stratified by number of positive lymph nodes. Groups were divided into 0, 1–2 and 3 or more positive nodes

| Variable () indicate % unless otherwise specified |

0 | 1–2 | ≥3 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T stage | <0.001 | |||

| 1 | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) | 0 | |

| 2 | 13 (72.2) | 4 (22.2) | 1 (5.6) | |

| 3 | 37 (27.0) | 47 (34.3) | 53 (38.7) | |

| 4 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | ||

| Location | 0.006 | |||

| Head of pancreas | 36 (37.9%) | 28 (29.5) | 31 (32.6) | |

| Uncinate | 6 (14.6) | 15 (36.6) | 20 (48.8) | |

| Body/Tail | 13 (44.8) | 12 (41.4) | 4 (13.8) | |

| Grade | 0.004 | |||

| Poor | 17 (21.8) | 28 (35.9) | 33 (42.3) | |

| Moderate | 30 (39.0) | 25 (32.5) | 22 (28.6) | |

| Well | 7 (77.8) | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Number LN removed mean (STD) | 15.6 (8.7) | 16.8 (8.1) | 18.7 (8.7) | 0.15 |

| Positive margin | 6 (16.2) | 7 (18.9) | 24 (65.9) | <0.001 |

As the T stage of the tumor increased, the number of positive lymph nodes also increased. 54 (98.2%) of patients with three or more lymph nodes had T3 or T4 tumors, compared to 48 (87%) of those with one or two positive lymph nodes, and 37 (67.3%) without positive lymph nodes (p < 0.001). Tumors located within the uncinate process were also associated with as significantly high rate of lymph node involvement.

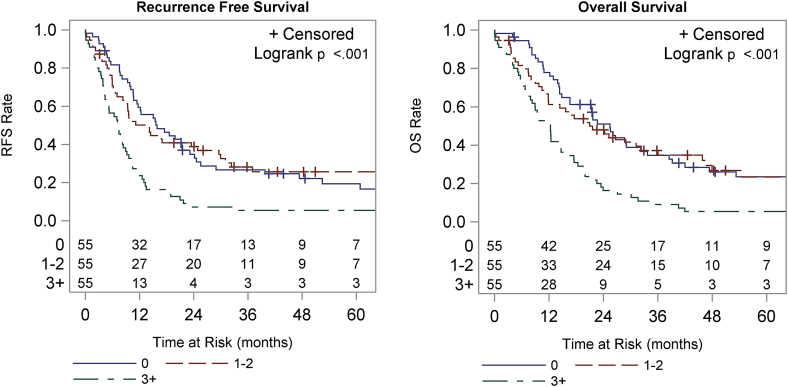

Patients with three or more positive lymph nodes had a significantly worse OS (p < 0.001) and RFS (p < 0.001) when compared to patients with none or one or two positive lymph nodes (Fig. 1). Median OS for patients with no positive lymph nodes was 25.5 months (mo) compared to 21.0 mo for those with one or two positive lymph nodes and 12.3 mo for three or more positive lymph nodes. The 1-year OS was 77.8%, 61.2% and 50.9% and the 3-year OS were 34.7%, 37. %3, and 9.1%, respectively for groups A, B and C. Median RFS was 15.9 mo, 14.2 mo and 7.3 mo for groups A, B and C, respectively. The 1-year RFS was 59.4%, 50.1%, and 23.6%, and 3-year RFS was 26.7%, 28.2%, and 5.5%, respectively.

Figure 1.

Recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) stratified by the number of positive lymph nodes. Groups include 0, 1–2, and 3 or more positive lymph nodes. RFS is shown in the left panel, OS in the right

Number of resected lymph nodes

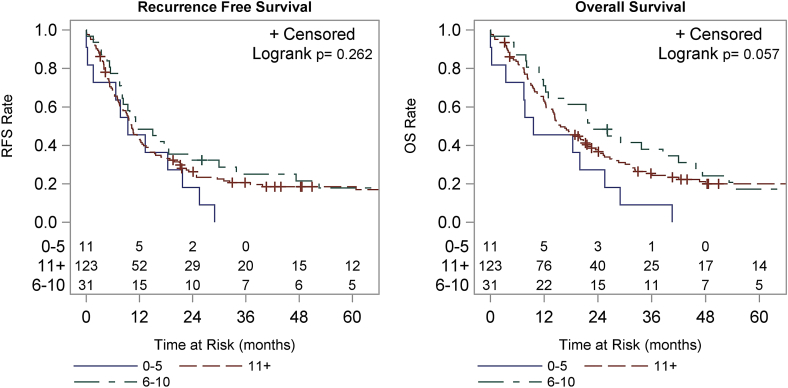

The overall average number of excised lymph nodes was 16.9. 123 (74.5%) patients had >10 lymph nodes removed, 31 (18.8%) had 6–10 lymph nodes removed and 11 (6.7%) had ≤5 lymph nodes removed (p = 0.154) (Fig. 1). There was no statistically significant correlation between the number of nodes removed and the rate of lymph node positivity; those with 0 positive nodes had an average of 15.6 nodes removed compared to 16.8 and 18.7 for groups B and C, respectively (p = 0.154). Those patients who had a higher number of lymph nodes resected trended towards a longer OS (p = 0.057), but there was no observed difference in RFS (p = 0.262) (Fig. 2). Median OS for patients who had >10 lymph nodes removed at the time of resection was 15.7 mo compared to 22.7 mo for 6–10 lymph nodes removed and 9.6 mo for those with ≤5 lymph nodes. The 1-year OS was 62.9%, 71.0% and 45.5% and the 3-year overall survival was 25.4%, 38.0%, and 9.1%, respectively for these groups. Patients who had >10 lymph nodes removed at the time of resection had a median RFS of 10.3 mo compared to 11.4 mo for 6–10 lymph nodes excised and 9.4 mo for those with ≤5 lymph nodes excised. The 1-year RFS was 43.1%, 48.4% and 45.5% and 3-year RFS were 20.6%, 25.1% and 0%, respectively for these groups.

Figure 2.

Recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) stratified by the number of lymph nodes resected and examined. Groups include 5 or less, 6–10 and greater than 10 lymph nodes examined. RFS is shown in the left panel, OS in the right

Lymph node ratio

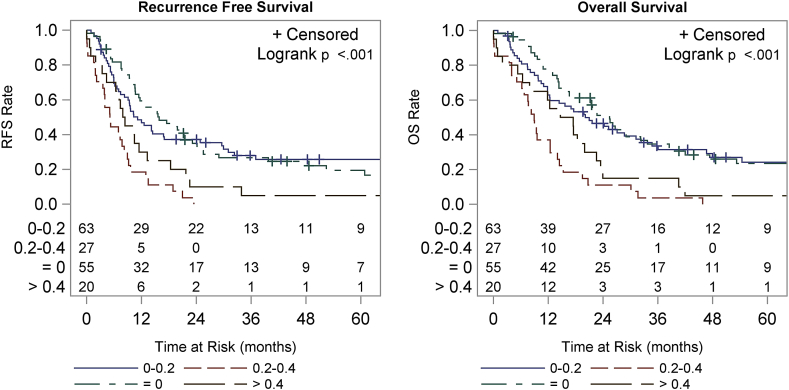

There was a strong correlation between lymph node ratio and both OS and RFS. Patients with a positive lymph node ratio of <0.2 had a statistically significant improved median OS compared to patients with a ratio of >0.2 (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3). Median OS was 25.5 mo for patients with 0 positive lymph nodes, 20.1 mo for a ratio of 0–0.2, 8.9 mo for 0.2–0.4, and 16.1 mo for >0.4. The 1-year OS was 77.8%, 62.9%, 37.0% and 60.0% and 3-year OS was 34.7%, 33.6%, 3.7%, and 15.0%, respectively for these groups based on lymph node ratio. Median RFS was 15.9 mo for patients with 0 positive lymph nodes, 11.1 mo for 0–0.2, 5.1 mo for 0.2–0.4, and 8.1 mo for >0.4. The 1-year RFS was 59.4%, 46.9%, 18.5% and 30.0%, respectively and 3-year RFS was 26.7%, 27.9%, 0%, and 5.0%, respectively.

Figure 3.

Recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) by ratio of positive lymph nodes to total nodes examined. Groups include ratios of 0, 0–0.2, 0.2–0.4 and greater than 0.4. RFS is shown in the left panel, OS in the right

Discussion

Prognosis of lymph nodes in pancreatic cancer has typically been related to a binary system within the current staging guidelines. A retrospective review of a large national database showed that in order to optimally stage pancreatic cancer, a minimum of 15 nodes is needed within the specimen.10 In our series of patients, we found no difference in OS or RFS between patients who had no metastatic lymph node disease and those who had minimal burden confined to one or two lymph nodes. Although this is not the first time this has been described, data comparing minimal nodal disease to node negative disease are uncommon and somewhat conflicting. In 2009, Massucco et al. found that having 2 positive lymph nodes conferred the same prognosis as a lack of metastatic lymph node disease.12 Additionally this study found that if nodal disease was confined to peripancreatic nodes there was no determent to prognosis. Lim et al. also reported similar findings, namely that patients with 1–3 lymph positive lymph nodes had a median survival 18.2 months, which was similar to the node negative group at 19.9 months.5

Recently, Valsangkar et al. published their single institution experience and compared it to SEER data.13 They showed that increasing the lymph node resection number provided more granular data and facilitated the ability to stratify patients into groups based upon both absolute number of positive lymph nodes as well as increasing lymph node ratio. Patients who had 13 or fewer lymph nodes excised at the time of resection tended to do worse overall. In addition to this finding, a single positive lymph node had a similar effect on OS than one or two positive lymph nodes in patients who had more than 17 lymph nodes excised. They showed no statistical difference in OS in patients who had ≥17 lymph nodes excised and had either 0, 1, or 2 positive lymph nodes. In our series, the average number of lymph nodes excised at resection was 16.9, correlating directly with their findings. Where our findings differed was with lymph node ratio, whereby Valsangkar et al. showed a significantly worse outcome in the 0–0.2 range as compared with our results showing that survival for this group was the same as the node negative group.

Riediger et al. also reported on the prognosis of a single positive lymph node, finding that one positive lymph node had the same prognosis as negative lymph node status.14 In addition, they found that increasing lymph node ratio was correlated to prognosis. However, they did not demonstrate an improvement in outcome when comparing the extent of lymph node dissection. Using a cut off of less than 15 lymph nodes removed, there was no demonstrated difference in survival. Several other studies have been published regarding the prognostic power of lymph node ratio; however, most do not evaluate the correlation between low burden metastatic nodal disease and outcome.9, 11, 15, 16

Much has also been written recently regarding the need for adequate lymph node resection.17, 18 Our data trended to show this correlation, but was not statistically significant given the very low number of patients who had 5 or less lymph nodes removed. Inadequate lymphadenectomy can potentially lead to stage migration causing patients to be under staged.

Interestingly, our study also offers insight into the association of tumor location and the risk of positive nodes. As shown in Table 2, tumors located in the uncinate were more likely to have ≥3 positive nodes, which in turn was associated with poorer RFS and OS. While other factors are likely to contribute to poorer outcomes for tumors of the uncinate, such as higher risk of positive margins given the technical limitations of resection for tumors in this part of the pancreas, this data highlights that a higher rate of positive nodes constitutes an important risk factor for tumors in the uncinate. This finding may have novel implications on clinical decision making because tumor location is a characteristic that is available pre-operatively, along with tumor size/invasion and CA 19-9 levels, that can be used to risk stratify patients. Conversely, although the number of lymph nodes retrieved, the number of positive nodes and the lymph node ratio have been shown by this study and others to impact survival outcomes, these are factors that cannot be utilized pre-operatively. Hence, our findings support the notion that tumor location in the pancreas should be considered in pre-operative treatment planning, namely the use of neoadjuvant therapy.

We recognize that there are limitations to this study. This is a relatively small retrospective review of patients who have undergone pancreatectomy with curative intent and the relationship of metastatic lymph node involvement on survival. Despite this limitation, the data regarding low volume nodal metastatic disease is clear and correlates with the relatively limited number of previously published data regarding this matter. While lymph node ratio offers a powerful way to discern the relative significance of a random number of positive lymph nodes in a random number of total excised lymph nodes, it does not address the common problem of minimal metastatic lymph node disease. Fully one third of our reported patient population received an adequate lymph node dissection and yet has minimal nodal disease, with outcomes that overlap patients without nodal disease. Grouping these patients into the broad category of positive nodal disease does not serve this population well in determining their survival after pancreatectomy. This study provides further evidence to a growing body of literature that quantification of positive lymph nodes correlates with survival outcomes, and therefore may play a definitive role in the pathologic staging system for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Taken together with previous studies, the consideration of inclusion of the number of positive lymph nodes and the positive lymph node ratio is highly warranted.

Funding

None.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Fortner J.G. Regional resection of cancer of the pancreas: a new surgical approach. Surgery (USA) 1973;73:307–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pedrazzoli S., DiCarlo V., Dionigi R., Mosca F., Pederzoli P., Pasquali C. Standard versus extended lymphadenectomy associated with pancreatoduodenectomy in the surgical treatment of adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas: a multicenter, prospective, randomized study. Ann Surg. 1998;228:508–517. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199810000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winter J.M., Cameron J.L., Campbell K.A., Arnold M.A., Chang D.C., Coleman J. 1423 pancreaticoduodenectomies for pancreatic cancer: a single-institution experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:1199–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allema J.H., Reinders M.E., Van Gulik T.M., Koelemay M.J.W., Van Leeuwen D.J., De Wit L.T. Prognostic factors for survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for patients with carcinoma of the pancreatic head region. Cancer. 1995;75:2069–2076. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950415)75:8<2069::aid-cncr2820750807>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim J.E., Chien M.W., Earle C.C. Prognostic factors following curative resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a population-based, linked database analysis of 396 patients. Ann Surg. 2003;237:74–85. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200301000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huebner M., Kendrick M., Reid-Lombardo K.M., Que F., Therneau T., Qin R. Number of lymph nodes evaluated: prognostic value in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:920–926. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1853-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Opfermann K.J., Wahlquist A.E., Garrett-Mayer E., Shridhar R., Cannick L., Marshall D.T. Adjuvant radiotherapy and lymph node status for pancreatic cancer: results of a study from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) registry data. Am J Clin Oncol Cancer Clin Trials. 2012 doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e31826e0570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson S.M., Rahman A., Haugk B., French J.J., Manas D.M., Jaques B.C. Metastatic lymph node ratio as an important prognostic factor in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sierzega M., Popiela T., Kulig J., Nowak K. The ratio of metastatic/resected lymph nodes is an independent prognostic factor in patients with node-positive pancreatic head cancer. Pancreas. 2006;33:240–245. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000235306.96486.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwarz R.E., Smith D.D. Extent of lymph node retrieval and pancreatic cancer survival: information from a large US population database. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:1189–1200. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.House M.G., Gönen M., Jarnagin W.R., D'Angelica M., Dematteo R.P., Fong Y. Prognostic significance of pathologic nodal status in patients with resected pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1549–1555. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Massucco P., Ribero D., Sgotto E., Mellano A., Muratore A., Capussotti L. Prognostic significance of lymph node metastases in pancreatic head cancer treated with extended lymphadenectomy: not just a matter of numbers. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3323–3332. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0672-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valsangkar N.P., Bush D.M., Michaelson J.S., Ferrone C.R., Wargo J.A., Lillemoe K.D. N0/N1, PNL, or LNR? the effect of lymph node number on accurate survival prediction in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:257–266. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1974-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riediger H., Keck T., Wellner U., Zur Hausen A., Adam U., Hopt U.T. The lymph node ratio is the strongest prognostic factor after resection of pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1337–1344. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0919-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.La Torre M., Cavallini M., Ramacciato G., Cosenza G., Del Monte S.R., Nigri G. Role of the lymph node ratio in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Impact on patient stratification and prognosis. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:629–633. doi: 10.1002/jso.22013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pawlik T.M., Gleisner A.L., Cameron J.L., Winter J.M., Assumpcao L., Lillemoe K.D. Prognostic relevance of lymph node ratio following pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer. Surgery (USA) 2007;141:610–618. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hellan M., Sun C., Artinyan A., Mojica-Manosa P., Bhatia S., Ellenhorn J.D. The impact of lymph node number on survival in patients with lymph node-negative pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2008;37:19–24. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31816074c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomlinson J.S., Jain S., Bentrem D.J., Sekeris E.G., Maggard M.A., Hines O.J. Accuracy of staging node-negative pancreas cancer a potential quality measure. Arch Surg. 2007;142:767–773. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.8.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]