Abstract

We have shown previously that noncoding variants mapping around a specific set of 170 genes encoding cardiomyocyte intercalated disc (ID) proteins are more enriched for associations with QT interval than observed for genome-wide comparisons. At a false discovery rate (FDR) of 5%, we had identified 28 such ID protein-encoding genes. Here, we assessed whether coding variants at these 28 genes affect QT interval in the general population as well. We used exome sequencing in 4,469 European American (EA) and 1,880 African American (AA) ancestry individuals from the population-based ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities) Study cohort to focus on rare (allele frequency <1%) potentially deleterious (nonsynonymous, stop-gain, splice) variants (n = 2,398 for EA; n = 1,693 for AA) and tested their effects on standardized QT interval residuals. We identified 27 nonsynonymous variants associated with QT interval (FDR 5%), 22 of which were in TTN. Taken together with the mapping of a QT interval GWAS locus near TTN, our observation of rare deleterious coding variants in TTN associated with QT interval show that TTN plays a role in regulation of cardiac electrical conductance and coupling, and is a risk factor for cardiac arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death.

Over the last decade genome wide association studies (GWAS) have been successful in identifying common variants (minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥1%), mostly non-coding, that underlie genetic variation of common diseases and quantitative traits1. Whole exome sequencing- (WES) and/or whole genome sequencing-(WGS) based approaches have extended such screens to include rare coding and non-coding variants (MAF < 1%)2. However, given the stringent thresholds set for attaining genome-wide significance (after correcting for multiple tests)3 and small allelic effects of individual variants4, the discovery of new associations has been challenging. With the number of tests being performed running in millions, correcting for the false positive rates results in a high false-negative rate due to which many true associations remain hidden. One way to increase the power to detect these true associations is to perform hypothesis-driven tests, where the search is limited to candidate genes/loci based on ancillary knowledge of genetic mapping, co-expression, protein-protein interaction, subcellular protein localization and others.

The QT interval (MIM 610141), a measurement of the duration of cardiac repolarization on an electrocardiogram (ECG), is a quantitative trait with ~30% heritability and considerable medical relevance as prolongation and shortening of the QT interval are associated with increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality5,6. Abnormal QT intervals observed in Mendelian disorders, known as long-QT syndrome and short-QT syndrome, are associated with increased risk of cardiac arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death (SCD), and are usually due to rare, high penetrance coding mutations in genes encoding ion channels and their associated proteins7. GWAS of the QT interval have identified at least 35 loci influencing trait variation in subjects of European American (EA) ancestry that collectively explain ~8% of the phenotypic variance in the general population8. Among these GWAS loci, a locus on chromosome 1q containing the gene NOS1AP is the major genetic regulator of QT interval and accounts for ~1% of the population trait variation9,10,11.

Recently, we had shown that a) an enhancer variant affecting NOS1AP expression is the functional basis of the observed trait association, b) over-expression of NOS1AP in cardiomyocytes leads to altered cellular electrophysiology, and c) NOS1AP is localized to cardiomyocyte intercalated discs (ID), leading us to propose that NOS1AP regulates QT interval by affecting cardiac electrical conductance and coupling12. Based on the localization of NOS1AP to ID we had hypothesized that ID plays a major role in regulating of QT interval and genetic variation in its components underlie the risk of cardiac arrhythmias and SCD. In support of our hypothesis, we showed that compared to genome-wide markers, common variants mapping near a specific set of 170 genes encoding ID proteins (henceforth referred to as ID genes) are significantly enriched for association with QT interval. Specifically, we identified 28 ID genes/loci, including NOS1AP, that showed common variants associations with QT interval (false discovery rate (FDR) 5%), many of which were missed in the GWAS and were identified by restricting to variants mapping near a functionally enriched set of ID genes12. In this paper, we assessed whether rare coding variants in these 28 ID genes are associated with QT interval variation as well. As opposed to GWAS that map common polymorphisms and identify positional markers and loci instead of genes, assessing association with coding variants couples the identification of functional variants with specific genes. Using variants identified in the 28 candidate ID genes by WES in 4,469 EA and 1,880 African American (AA) ancestry individuals from the ARIC13 (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) cohort, we identified multiple rare nonsynonymous variants in TTN associated with QT interval variation. Using TTN-specific functional information to annotate coding variants we observed enrichment in association signal and propose that individual protein-specific functional information will be critical in identifying disease/traits variants among a large number of variants identified by sequencing studies.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

Of the 15,792 subjects in the ARIC study, we studied 5,718 EA and 2,836 AA ancestry subjects in whom we had access to GWAS8 and WES (unpublished) data. The ARIC study subjects and the procedures have been previously described in13. Briefly, ARIC is a population-based prospective cohort study of cardiovascular disease in 15,792 subjects aged 45–64 years at baseline (1987–89) who were randomly sampled from four U.S. communities (~4,000 per community). Cohort members completed four extensive clinic examinations, conducted every three years between 1987 and 1998, which included medical, social and demographic data. For assessment of QT interval at baseline, 12-lead ECG digital recording and a 2-minute paper recording of a three-lead (leads V1, II and V5) rhythm strip were made. The QT interval was determined by identifying Q-wave onset and T-wave offset in all three leads. T-wave offset was defined as the point of maximum change of slope as the T-wave merges with the baseline5,14. All individuals studied and all analyses on their samples were performed according to the Helsinki declarations, were approved by local ethics and institutional review committees of the CHARGE (Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology) consortium15 and all participants provided informed consent.

Library Preparation, Exome Sequencing, Variant and Genotype Calling

All the steps of library preparation, capture method, sequencing, variant and genotype calling have been detailed elsewhere16. All variants analyzed in this study have been submitted to Database of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (dbSNP)17, Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine under the dbSNP accession: ss1998364261-ss1998377886 (dbSNP Build ID:149).

Variant-level and Sample-level QC

WES was performed on samples from multiple cohorts as part of the CHARGE consortium15 and will be described elsewhere (unpublished data). In this study we analyzed only single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and ignored the small insertions/deletions (indels). Variant-level QC applied on the entire sequencing data removed variants with >20% missing data, more than 2 observed alleles, monomorphic, or with mean depth of greater than 500-fold. Then, separately within each ancestry group, variants that deviated from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P < 5 × 10−6) were filtered out. Next, within each cohort, samples with >20% missing data were removed. We, then, assessed sequencing data from 5,718 EA and 2,836 AA ARIC subjects. In addition, we filtered out 1,249 EA and 956 AA ancestry ARIC subjects based on genetic relatedness (based on common variant genotypes8), genetic outliers, missing phenotype (no raw QT interval measurement), history of cardiac disease, abnormal ECG findings, or those on known QT-altering medications13, leaving 4,469 EA and 1,880 AA ancestry subjects for analysis.

Variant Annotation

For each of the 28 candidate ID genes we first identified the most abundant human cardiac RefSeq18 transcript using RNA-seq-based gene expression data generated by the UCSD Human Reference Epigenome Mapping Project19 (GEO accession: GSE16256). WES variants observed were then annotated with respect to this transcript using ANNOVAR20,21. Nonsynonymous variants were further annotated with respect to the 46-species vertebrate base-wise conservation score generated using phyloP22 (available from the UCSC Genome Browser23,24) and overlap with a known protein domain (from the Human Protein Reference Database25,26). Nonsynonymous variants in TTN were also annotated with respect to the sarcomeric bands27. For all variants found to be associated with QT interval, we assessed the predicted functional effect using SIFT28 and PolyPhen-229 and also looked up allele counts in the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) browser30.

Statistical Analyses

We used multivariate linear regression to correct the raw QT interval measured in the ECG for known covariates: heart-rate (RR interval on ECG)31, age32 and sex33 as well as genotypes of common polymorphisms representing 34 QT interval GWAS hits; rs1805128 in KCNE1 was not observed in ARIC subjects8. Single variant quantitative trait association analysis was performed as implemented in PLINK34,35 using a linear regression model with standardized QT interval residuals. False discovery rates were calculated from p-values using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure36.

Results

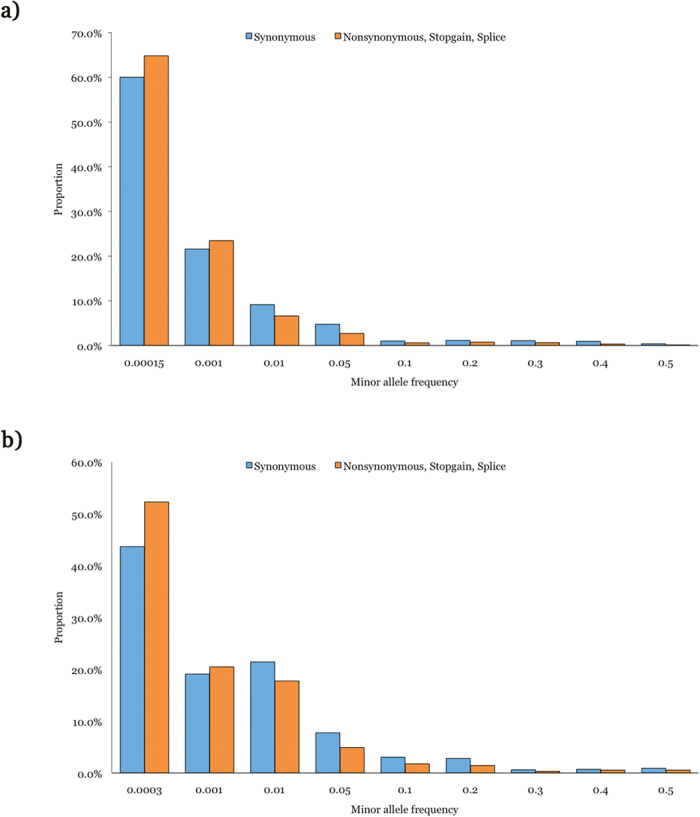

Of the 5,718 and 2,836 self-identified EA and AA ARIC individuals in which WES was performed, 1,249 EA and 956 AA samples, respectively, were excluded for the following reasons a) suspected first-degree relative of an included individual based on genome-wide genotype data, b) genetic outlier based on average identity-by-state using PLINK35 and >8 standard deviations along any of the first 10 principal components in EIGENSTRAT37 after 5 iterations, c) genotypic sex not matching phenotypic sex, d) discordant with previous genotype data, e) individuals with atrial fibrillation, QRS duration >120 ms, bundle branch block or intraventricular conduction delay, f) individuals with history of heart failure or myocardial infarction, and g) when available, use of electronic pacemaker or QT-altering drugs. In the remaining 4,469 EA and 1,880 AA ARIC samples, a total of 5,878 coding SNVs (3,830 in EA subjects, 2,982 in AA subjects and overlap of 934 variants) were identified at the 28 candidate ID genes. Coding SNVs were annotated with respect to the most abundant human cardiac RefSeq transcript using ANNOVAR. Table 1 lists the 28 candidate genes, corresponding transcripts and ORF lengths, types and numbers of coding SNVs observed combined in the EA and AA ARIC subjects, and number of coding SNVs per coding base (see Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 for EA and AA only variants, respectively). A total of 2,035 synonymous, 3,777 nonsynonymous, 33 stop-gain and 33 canonical splice site SNVs were observed across all 28 ID genes. The number of coding SNVs/coding base varied from 0.017 (KCNK3) to 0.050 (NRAP) with a mean and median of 0.031, across all 28 ID genes. For each coding SNV we calculated minor allele frequency using the genotypes from the EA and AA ARIC samples separately and as expected, the majority of the coding variants were rare (Fig. 1). Of all synonymous variants, ~91% (1182/1303) in EA subjects and ~84% (935/1111) in AA subjects had allele frequency <1%, and of all nonsynonymous, stop-gain and splice variants, ~95% (2398/2527) in EA subjects and ~91% (1693/1871) in AA subjects had allele frequency of <1%. Nearly 60% of all synonymous variants and 65% of all nonsynonymous, stop-gain and splice variants were observed as singletons in EA subjects; the corresponding values for AA subjects were 44% and 52%, respectively (Fig. 1).

Table 1. Gene symbol, most abundant cardiac transcript, ORF length, number and type of coding variants observed in EA and AA ARIC subjects, and number of coding variants per coding base for the 28 ID genes.

| Gene | Transcript1 | ORF length | Synonymous | Nonsynonymous | Stopgain | Splice | All | #Variants/ORF length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANKRD30A | NM_052997 | 4026 | 42 | 106 | 3 | 3 | 154 | 0.038 |

| ATP1B1 | NM_001677 | 912 | 15 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 0.020 |

| CAV1 | NM_001172896 | 444 | 4 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0.034 |

| CAV2 | NM_001233 | 489 | 3 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 0.027 |

| CD59 | NM_001127223 | 387 | 9 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0.036 |

| CDH11 | NM_001797 | 2391 | 34 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 79 | 0.033 |

| CDH2 | NM_001792 | 2721 | 32 | 42 | 0 | 0 | 74 | 0.027 |

| CIB1 | NM_001277764 | 696 | 10 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 22 | 0.032 |

| ERBB4 | NM_005235 | 3927 | 35 | 53 | 1 | 1 | 90 | 0.023 |

| KCNJ4 | NM_152868 | 1338 | 27 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 0.026 |

| KCNK3 | NM_002246 | 1185 | 12 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0.017 |

| LRFN2 | NM_020737 | 2370 | 46 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 78 | 0.033 |

| NOS1AP | NM_014697 | 1521 | 24 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 42 | 0.028 |

| NRAP | NM_001261463 | 5196 | 76 | 171 | 7 | 8 | 262 | 0.050 |

| PARVA | NM_018222 | 1239 | 21 | 21 | 0 | 2 | 44 | 0.036 |

| PKP2 | NM_004572 | 2646 | 25 | 63 | 1 | 2 | 91 | 0.034 |

| PKP4 | NM_003628 | 3579 | 45 | 73 | 1 | 2 | 121 | 0.034 |

| PRKCA | NM_002737 | 2019 | 28 | 22 | 1 | 0 | 51 | 0.025 |

| PTK2 | NM_001199649 | 3198 | 28 | 47 | 1 | 1 | 77 | 0.024 |

| SCN5A | NM_000335 | 6048 | 109 | 130 | 2 | 0 | 241 | 0.040 |

| SGCZ | NM_139167 | 939 | 6 | 32 | 1 | 1 | 40 | 0.043 |

| SIPA1L1 | NM_001284247 | 5412 | 66 | 88 | 0 | 0 | 154 | 0.028 |

| SLC16A1 | NM_003051 | 1503 | 13 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 0.022 |

| SLC4A1 | NM_000342 | 2736 | 44 | 83 | 0 | 0 | 127 | 0.046 |

| SLC8A1 | NM_021097 | 2922 | 35 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 0.027 |

| SPTBN1 | NM_003128 | 7095 | 127 | 87 | 0 | 0 | 214 | 0.030 |

| TLN1 | NM_006289 | 7626 | 95 | 95 | 0 | 0 | 190 | 0.025 |

| TTN | NM_001267550 | 107976 | 1024 | 2448 | 14 | 13 | 3499 | 0.032 |

| 2035 | 3777 | 33 | 33 | 5878 |

1Most abundant human cardiac transcript.

Figure 1.

Minor allele frequency distribution of coding variants observed at 28 ID genes in EA (a) and AA (b) ARIC subjects.

The raw QT interval measured in the ECG is known to be strongly dependent on heart-rate (RR interval on ECG)31, age32 and sex33 and needs to be corrected for these known covariates before assessing associations. Using a multivariate linear regression model, the raw QT interval measurement in 4,469 EA and 1,880 AA ARIC subjects was corrected for heart-rate, age, sex, and also for the genotypes at the 34 common GWAS variants reported to modulate QT interval in the general population (rs1805128 in KCNE1 was not observed in ARIC subjects)8 (see Supplementary Figs S1 and S2 for distribution of corrected QT interval in EA and AA subjects, respectively). Of all coding SNVs identified at the 28 ID genes by WES in EA and AA ARIC subjects, we limited the association analysis to rare (MAF < 1%) and potentially deleterious (nonsynonymous, stop-gain, splice) coding variants (n = 2,398 for EA; n = 1,693 for AA). Single variant quantitative trait association analysis using a linear regression model with standardized QT residuals identified 16 and 11 variants, all nonsynonymous, in EA (Table 2) and AA (Table 3) subjects, respectively, at a FDR of 5%. Of the 16 QT interval associated variants in EA subjects 13 were in TTN and 1 each in SCN5A, ERBB4 and SGCZ (Table 2); 14 variants observed as singletons in 10 subjects and 2 variants observed as doubletons in 4 subjects (Supplementary Table S3). Of the 11 QT interval associated variants in AA subjects 9 were in TTN and 1 each in SCN5A and TLN1 (Table 3); 9 variants observed as singletons in 7 subjects and 2 variants observed as doubletons in 4 subjects (Supplementary Table S4). Thus, TTN had 22 out of 27 variants associated with QT interval in EA and AA subjects.

Table 2. Coding variants associated with QT interval in EA ARIC subjects.

| Chr:Position (hg19) | Gene | cDNA change | Protein change | MAF | Beta | P | PhyloP score | Protein domain | ExAC allele count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2:179455718 | TTN | c.G60734A | p.R20245Q | 0.00011 | 8.78 | 1.22 × 10−18 | 6.39 | FN2 | 4/120604 |

| 2:179407497 | TTN | c.G97084T | p.A32362S | 0.00011 | 5.39 | 6.89 × 10−8 | 0.15 | – | – |

| 2:212522534 | ERBB4 | c.C1891T | p.H631Y | 0.00022 | 3.69 | 1.73 × 10−7 | 4.15 | – | – |

| 2:179634919 | TTN | c.A8509T | p.S2837C | 0.00022 | 3.19 | 6.43 × 10−6 | 3.73 | IG | 12/121362 |

| 2:179473995 | TTN | c.A52042G | p.M17348V | 0.00011 | 4.14 | 3.33 × 10−5 | 1.38 | FN3 | 2/96388 |

| 2:179398282 | TTN | c.C103060T | p.P34354S | 0.00011 | 4.14 | 3.47 × 10−5 | 5.98 | – | – |

| 2:179629385 | TTN | c.A9857G | p.K3286R | 0.00011 | 4.11 | 3.81 × 10−5 | 5.11 | IGC2 | 15/121360 |

| 2:179496930 | TTN | c.C43691G | p.S14564C | 0.00011 | 4.11 | 3.98 × 10−5 | 6.35 | – | 5/81630 |

| 2:179466803 | TTN | c.C55195T | p.P18399S | 0.00011 | 3.88 | 0.00010 | 4.14 | FN3 | 1/120260 |

| 8:13959964 | SGCZ | c.G665T | p.G222V | 0.00011 | 3.78 | 0.00015 | 5.48 | – | – |

| 2:179424880 | TTN | c.T85979C | p.I28660T | 0.00011 | 3.77 | 0.00016 | 5.31 | IGC2 | 2/120508 |

| 2:179413763 | TTN | c.G92590A | p.D30864N | 0.00011 | 3.66 | 0.00025 | 3.76 | FN3 | 16/120638 |

| 2:179486250 | TTN | c.A45301C | p.N15101H | 0.00011 | 3.62 | 0.00029 | 3.60 | – | – |

| 2:179644182 | TTN | c.A3737T | p.H1246L | 0.00011 | 3.63 | 0.00029 | 3.43 | – | – |

| 3:38592534 | SCN5A | c.G5326A | p.V1776M | 0.00011 | 3.62 | 0.00029 | 5.80 | – | 3/121080 |

| 2:179666975 | TTN | c.G185A | p.R62H | 0.00011 | 3.56 | 0.00037 | 6.21 | IGC2 | 15/121364 |

Table 3. Coding variants associated with QT interval in AA ARIC subjects.

| Chr:Position (hg19) | Gene | cDNA change | Protein change | MAF | Beta | P | PhyloP score | Protein domain | ExAC allele count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9:35711334 | TLN1 | c.A3937G | p.S1313G | 0.00026 | 15.81 | 3.60 × 10−60 | 3.48 | – | 2/121374 |

| 2:179455331 | TTN | c.C61121T | p.P20374L | 0.00053 | 8.85 | 2.26 × 10−37 | 6.39 | – | 2/119910 |

| 2:179447784 | TTN | c.C65746T | p.R21916W | 0.00026 | 4.98 | 5.87 × 10−07 | 0.65 | IGC2 | 13/113940 |

| 3:38645514 | SCN5A | c.G1579A | p.G527R | 0.00026 | 4.33 | 1.48 × 10−05 | 3.93 | – | 4/90200 |

| 2:179528396 | TTN | c.C36490A | p.P12164T | 0.00026 | 4.10 | 4.03 × 10−05 | −0.49 | IG | 7/117870 |

| 2:179447313 | TTN | c.C65870T | p.P21957L | 0.00026 | 3.90 | 9.92 × 10−05 | 6.22 | FN3 | – |

| 2:179428672–179428673 | TTN | c.82186_82187CA > GT | p.Q27396V | 0.00026 | 3.79 | 0.00015 | 4.74, 5.31 | FN3 | 1/120622, 1/120618 |

| 2:179451505 | TTN | c.G64123A | p.V21375M | 0.00026 | 3.79 | 0.00015 | 6.37 | FN3 | 1/120562 |

| 2:179497341 | TTN | c.G43392A | p.M14464I | 0.00026 | 3.79 | 0.00015 | 1.68 | IGC2 | 3/120562 |

| 2:179434555 | TTN | c.G76304A | p.C25435Y | 0.00026 | 3.62 | 0.00029 | 4.48 | IGC2 | 1/120440 |

| 2:179440480 | TTN | c.T70379G | p.L23460R | 0.00053 | 2.52 | 0.00036 | 5.13 | FN3 | – |

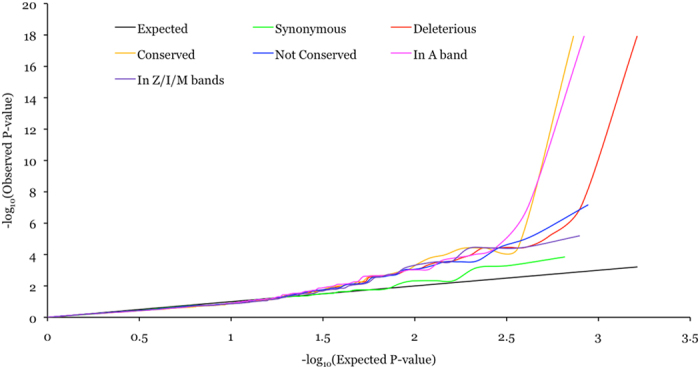

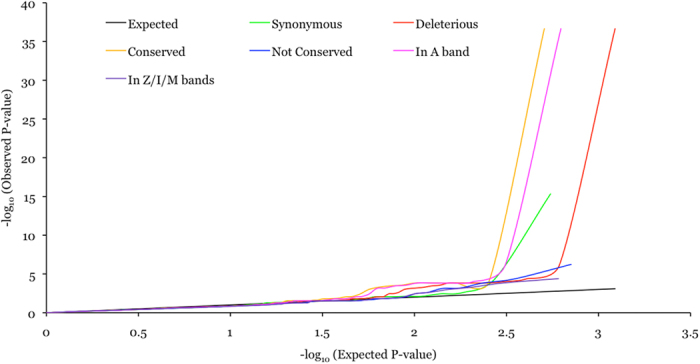

Given that ~80% of the QT interval associated variants in this study were in TTN we focused on all coding variants in TTN and assessed whether classifying variants into various categories based on function, conservation and sarcomeric domain location, irrespective of allele frequency, might uncover additional associated variants. All TTN coding variants were classified by function into two classes: potentially benign (synonymous; 654/549 in EA/AA) and potentially deleterious (nonsynonymous, stop-gain and splice site; 1624/1231 in EA/AA). All nonsynonymous TTN variants were classified by conservation into two classes: conserved (phyloP score ≥4; 732/508 in EA/AA) and not conserved (phyloP score < 4; 877/710 in EA/AA). Titin encoded by TTN is the largest protein in humans and is highly expressed in striated muscle cells, where two titin molecules span each sarcomere in opposing polarity. Within the sarcomere, titin is anchored in the Z-line and spans through the I- and A-bands to the M-line. Mutations in TTN are a leading genetic cause of dilated cardiomyopathies (DCM) and a majority of mutations in patients are observed in the A band27, indicating the functional importance of the corresponding part of the protein in normal physiology. To evaluate the effect of sarcomeric domain location all potentially deleterious TTN variants were classified into two classes: in A band (836/625 in EA/AA) and in Z/I/M bands (788/606 in EA/AA). Quantile-quantile (QQ) plots for various classes of variants showed a trend towards association enrichment for conserved nonsynonymous variants and deleterious variants mapping to the A band (Figs 2 and 3).

Figure 2. QQ plot for various classes of TTN variants in EA subjects.

Figure 3. QQ plot for various classes of TTN variants in AA subjects.

Discussion

In this study we identified multiple rare nonsynonymous variants in TTN associated with QT interval variation in the general population. Identification of these rare coding TTN variants with large genetic effects within a moderately sized subset of population-based ARIC cohort13, represented by 4,469 EA and 1,880 AA ancestry subjects, was made feasible by restricting association analysis of WES variants to coding variants identified in 28 ID genes, for which we had prior evidence of genetic association with QT interval based on common, mostly noncoding polymorphisms12. In other words, a functional-hypothesis driven approach was necessary to reduce the search space and increase the power to detect novel associations. Also, by performing association analysis based on coding variants we could directly implicate TTN as a causal gene, in contrast to GWAS that mostly identify positional markers. It is important to point out that only 1 out of the 28 ID genes assessed had convincing evidence for coding variants associated with QT interval, indicating that the population level trait variance is largely explained by common noncoding variants.

Titin, encoded by TTN, is an abundant protein of the striated muscle contractile apparatus and plays a key role in sarcomere assembly and functioning of muscle fibers. Beyond the well-documented role played by rare deleterious TTN mutations in causing cardiomyopathies27, including arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia38,39, and skeletal myopathies, there is growing evidence for the role of deleterious TTN variants in conduction defects, in the presence or absence of cardiomyopathy and sudden cardiac death40,41. Our observations of rare coding TTN variants associated with QT interval variation in a population-based cohort further support a broader role of TTN in cardiac physiology. In addition, QT interval GWAS have mapped common noncoding variants near TTN at chromosome 2q31.28, raising the possibility that TTN expression levels could also modulate cardiac repolarization.

Of the 27 rare nonsynonymous variants associated with QT interval in EA and AA ancestry ARIC subjects, 22 were in TTN, 2 in SCN5A and 1 each in ERBB4, SGCZ and TLN1. Among these 5 genes, based on the number of associated variants uncovered, we conclude that TTN has the potential to regulate QT interval variation. Although, the role of SCN5A in regulating QT interval is well established, based on genetic studies of rare Mendelian long-QT syndrome7, we observed only 2 variants in SCN5A associated with QT interval variation in the general population. Further association studies would be necessary to assess whether variation in the remaining 3 genes, ERBB4, SGCZ and TLN1, regulates QT interval in the general population. A major limitation of our study is that the 27 QT interval associated variants identified were observed as singletons (23 variants) or doubletons (4 variants) (see Supplementary Table S5 for allele counts in different populations), which raises the possibility that some of these could be false-positives. Therefore, performing similar association studies in independent and larger cohorts is, as always, necessary. Another important question that remains to be explored is whether and how these variants affect gene function (see Supplementary Table S6 for predicted functional effect from SIFT28 and PolyPhen-229). In summary, using a hypothesis-based approach to limit association analysis of WES variants to coding variants in 28 ID genes, we identified multiple rare nonsynonymous TTN variants associated with QT interval variation in the general population, providing evidence of a new role for TTN in cardiac electrical conduction and coupling.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Kapoor, A. et al. Rare coding TTN variants are associated with electrocardiographic QT interval in the general population. Sci. Rep. 6, 28356; doi: 10.1038/srep28356 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the U.S. National Institute of Health grants RO1GM104469 and RO1HL128782. The ARIC Study is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) contracts (HHSN268201100005C, HHSN268201100006C, HHSN268201100007C, HHSN268201100008C, HHSN268201100009C, HHSN268201100010C, HHSN268201100011C, and HHSN268201100012C), R01HL087641, R01HL59367 and R01HL086694. The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions. Funding support for “Building on GWAS for NHLBI-diseases: the U.S. CHARGE consortium” was provided by the NIH through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) (5RC2HL102419). Data for “Building on GWAS for NHLBI-diseases: the U.S. CHARGE consortium” was provided by Eric Boerwinkle on behalf of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, L. Adrienne Cupples, principal investigator for the Framingham Heart Study, and Bruce Psaty, principal investigator for the Cardiovascular Health Study. Sequencing was carried out at the Baylor College of Medicine Human Genome Sequencing Center (U54 HG003273).

Footnotes

A.C. is on the Scientific Advisory Board of Biogen Idec and this potential competing interest is managed by the policies of the Johns Hopkins University, School of Medicine. All other authors have no competing financial interests to declare.

Author Contributions A.K. and A.C. designed the study; A.C., E.B., M.L.G. and D.E.A. contributed towards data generation; A.K., K.B., L.X., P.N., D.L., D.E.A. and A.C. performed data analysis; A.K., K.B. and A.C. wrote the manuscript; all authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Hirschhorn J. N. Genomewide association studies–illuminating biologic pathways. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1699–1701 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirulli E. T. & Goldstein D. B. Uncovering the roles of rare variants in common disease through whole-genome sequencing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 415–425 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risch N. & Merikangas K. The future of genetic studies of complex human diseases. Science 273, 1516–1517 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolio T. A. et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature 461, 747–753 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker J. M. et al. Heart rate-corrected QT interval prolongation predicts risk of coronary heart disease in black and white middle-aged men and women: the ARIC study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 43, 565–571 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton-Cheh C. et al. QT interval is a heritable quantitative trait with evidence of linkage to chromosome 3 in a genome-wide linkage analysis: The Framingham Heart Study. Heart Rhythm 2, 277–284 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priori S. G. & Napolitano C. Genetics of cardiac arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1015, 96–110 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arking D. E. et al. Genetic association study of QT interval highlights role for calcium signaling pathways in myocardial repolarization. Nat. Genet. 46, 826–836 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arking D. E. et al. A common genetic variant in the NOS1 regulator NOS1AP modulates cardiac repolarization. Nat. Genet. 38, 644–651 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton-Cheh C. et al. Common variants at ten loci influence QT interval duration in the QTGEN Study. Nat. Genet. 41, 399–406 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeufer A. et al. Common variants at ten loci modulate the QT interval duration in the QTSCD Study. Nat. Genet. 41, 407–414 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor A. et al. An enhancer polymorphism at the cardiomyocyte intercalated disc protein NOS1AP locus is a major regulator of the QT interval. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 94, 854–869 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The ARIC Investigators. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives. Am. J. Epidemiol. 129, 687–702 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rautaharju P. M., Park L. P., Chaitman B. R., Rautaharju F. & Zhang Z. M. The Novacode criteria for classification of ECG abnormalities and their clinically significant progression and regression. J. Electrocardiol. 31, 157–187 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psaty B. M. et al. Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology (CHARGE) Consortium: Design of prospective meta-analyses of genome-wide association studies from 5 cohorts. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2, 73–80 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupski J. R. et al. Exome sequencing resolves apparent incidental findings and reveals further complexity of SH3TC2 variant alleles causing Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy. Genome Med. 5, 57 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/ Database of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms. Date of access:05/20/2016.

- Pruitt K. D. et al. RefSeq: an update on mammalian reference sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D756–63 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE16256 USCD Human Reference Epigenome Mapping Project. Date of access:01/01/2015.

- http://annovar.openbioinformatics.org/en/latest/ ANNOVAR. Date of access:01/01/2015.

- Wang K., Li M. & Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e164 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard K. S., Hubisz M. J., Rosenbloom K. R. & Siepel A. Detection of nonneutral substitution rates on mammalian phylogenies. Genome Res. 20, 110–121 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karolchik D. et al. The UCSC Table Browser data retrieval tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, D493–6 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- https://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgTables UCSC Table Browser tool. Date of access:01/01/2015.

- http://www.hprd.org/ Human Protein Reference Database. Date of access:01/01/2015.

- Keshava Prasad T. S. et al. Human Protein Reference Database–2009 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D767–72 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A. M. et al. Integrated allelic, transcriptional, and phenomic dissection of the cardiac effects of titin truncations in health and disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 270ra6 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng P. C. & Henikoff S. Predicting Deleterious Amino Acid Substitutions. Genome Research 11, 863–874 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adzhubei I. A. et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat. Methods 7, 248–249 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- http://exac.broadinstitute.org/ ExAC Browser. Date of access:01/01/2015.

- Bazett H. C. An analysis of the time-relations of electrocardiograms. Annals of Noninvasive Electrocardiology 2, 177–194 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Reardon M. & Malik M. QT interval change with age in an overtly healthy older population. Clin. Cardiol. 19, 949–952 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. et al. Sex differences in the rate of cardiac repolarization. J. Electrocardiol. 27, 72–73 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/plink/ PLINK. Date of access:01/01/2015.

- Purcell S. et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y. & Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 57, 289–300 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Price A. L. et al. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 38, 904–909 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M. et al. Genetic variation in titin in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy-overlap syndromes. Circulation 124, 876–885 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun F. et al. Titin and desmosomal genes in the natural history of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. J. Med. Genet. 51, 669–676 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E. & Mani A. Titin as a gene for conduction defects with and without cardiomyopathy (2160M). 64th Annual Meeting of The American Society of Human Genetics San Diego, California (October 20, 2014).

- Leinonen J. T. et al. Search for novel mutations predisposing to ventricular fibrillation without overt cause (614T). 65th Annual Meeting of The American Society of Human Genetics Baltimore, Maryland (October 8, 2015).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.