Abstract

Hearing impairment most often involves loss of sensory hair cells and auditory neurons. As this loss is permanent in humans, a cell therapy approach has been suggested to replace damaged cells. It is thus of interest to generate lineage restricted progenitor cells appropriate for cell based therapies. Human long-term self-renewing neuroepithelial stem (lt-NES) cell lines exhibit in vitro a developmental potency to differentiate into CNS neural lineages, and importantly lack this potency in vivo, i.e do not form teratomas. Small-molecules-driven differentiation is today an established route obtain specific cell derivatives from stem cells. In this study, we have investigated the effects of three small molecules SB431542, ISX9 and Metformin to direct differentiation of lt-NES cells into sensory neurons. Exposure of lt-NES cells to Metformin or SB431542 did not induce any marked induction of markers for sensory neurons. However, a four days exposure to the ISX9 small molecule resulted in reduced expression of NeuroD1 mRNA as well as enhanced mRNA levels of GATA3, a marker and important player in auditory neuron specification and development. Subsequent culture in the presence of the neurotrophic factors BDNF and NT3 for another seven days yielded a further increase of mRNA expression for GATA3. This regimen resulted in a frequency of up to 25-30% of cells staining positive for Brn3a/Tuj1. We conclude that an approach with ISX9 small molecule induction of lt-NES cells into auditory like neurons may thus be an attractive route for obtaining safe cell replacement therapy of sensorineural hearing loss.

Keywords: Sensory neurons, isozaxole 9, stem cell, differentiation

Introduction

The World Health Organization estimates that 360 million people have a disabling hearing loss (http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs300/en/). The most common causes of hearing impairment are related to either inherited and acquired factors e.g., exposure to noise, againg and exposure to otoxic drugs [1]. Hearing impairment is predominantly caused by a loss of sensory hair cells in the cochlea and the subsequent loss of spiral ganglion neurons. In mammals, loss is permanent as neither hair cells nor sensory neurons can regenerate in the cochlea. However, in non-mammalian species the auditory cells have capacity to regenerate, and thus function can be restored [2,3]. It has been shown in avians and lower vertebrates that supporting cells can be triggered by the factors released from dying hair cells to replace the sensory cells, by proliferation or transdifferentiation modes [4]. In humans, the only now available clinical approach for functionally replacing sensory cells is the cochlear implant. A cochlear implant bypasses missing or malfunctioning hair cells and electrically stimulates the auditory neurons. It follows that the efficacy of the cochlear implant depends on the presence of remaining healthy auditory neurons that can be electrically stimulated. A cell therapy approach aiming at increasing the number of auditory neurons in cochlea has thus been proposed to improve the functionality of cochlear implants [5].

Stem cells have the potential to differentiate in many cell types and different technical approaches have been used for obtaining controlled induction into specific cell lineages [6]. Synthetic small molecules with specificities for genes or gene products have been shown to be valuable tools in this respect [7]. This approach has been used to modulate specific targets in stem cells involved in signaling, metabolic, transcriptional or epigenetic mechanisms and allowing them to either maintain their pluripotency or differentiate into particular cell fates [8,9]. Compared to genetic modifications, a chemical approach has a number of advantages, e.g., less labor intense, providing a higher degree of temporal control over protein function (effects are rapid and reversible), and large possibilities to be used at different concentrations and combinations. Interestingly, it has been shown that certain small molecules trigger a rapid conversion of embryonic stem cells to a neural cell fate [8,9].

Recent studies have revealed that isoxazole 9 (ISX9; a small molecule found to promote neurogenesis), and metformin (a first line diabetic drug) induce neuronal differentiation in mouse hippocampal neural stem cells and mouse embryonic cortical radial precursors respectively [10,11].

SB431542 is an inhibitor of the TGFβ/activin/ nodal signalling, blocking phosphorylation of ALK4, ALK5 and ALK7 [12]. It has been shown to increase neuronal differentiation as well as sensory neural differentiation in combination with other small molecules by using human pluripotent stem cells [13-15]. A combination of the small molecule SB431542, Noggin and wnt-1 was reported to promote sensory neural differentiation in human neural progenitors [16].

Metformin is a diabetic drug shown to induce βIII tubulin positive cells from cortical precursors [11], and to provide a neuroprotective effect from oxidative damage [17]. In vivo administration of metformin has been reported to promote neurogenesis by enhancing the proliferation and differentiation of adult olfactory and hippocampal subgranular zone neuroblasts [11].

Long-term self-renewing neuroepithelial stem cell (lt-NES cells), derived from human embryonic stem cells (hESC) or induced pluripotent stem cells (hIPSC), offer new tools for studies of neural development. lt-NES can also be captured directly from the human foetuses [18]. The Lt-NES cells express markers present also in neuroepithelia and neural rosettes, such as PAX6, PROM1, SOX1, MMRN1 and PLZF [19]. It-NES cells can be stably expanded in culture over long periods of time with maintained potency to differentiate into cell populations with more than 90% neurons and lower number of glia cells [19]. An alternative route to obtain Lt- NES cells identical to iPS cell derived.

Here, we report the effect of the above described three small molecules; SB431542, Isoxazole 9 and metformin on lt-NES cells, with focus on possible differentiation into sensory neurons.

Materials and methods

Culture of neuroepithelial stem cells

Lt-NES cell line C1GFP and AF22 were derived from iPSC cell lines and cultured as described previously [19]. Briefly, cells were cultured on 0.1 mg/ml polyornithine (sigma) and 2 μg/ml laminin (sigma) coated flask in NES medium, consisting of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/F12 (DMEM/F12) with L-glutamin, N2 (1:100), B27 (1:1000), penicillin/streptomycin (100 units), bFGF (10 ηg/ml) and hrEGF (10 ηg/ml). Cells were passaged 1:3 every 2-3 days using tripLE Express and define trypsin inhibitor (all reagents from Life Technologies).

Dose response experiments

For dose response experiments, cells were plated on polyornithine and laminin coated cover slips at density of 50,000 cell/cm2 in NES differentiation medium (1:1 ration of DMEM/F12 and Neurobasal medium, N2 (1:100), B27 (1:100)) for 2 days. After two days, cells were treated with NES differentiation medium with isozaxole 9 (ISX9) at a concentration of 5, 10, 20 or 40 μM for 4 days.

Differentiation experiments with small molecule compounds

Isoxazole-9 (ISX9) and SB431542 were dissolved in DMSO and metformin in distilled water. ISX9 was used at a concentration of 20 μm, as identified by dose response experiments (see above). The concentration used for SB431542 was 10 μM and for metformin 500 μM, as described in previous reports [11,16,20]. Cells were plated on polyornithine and laminin coated cover slips in NES differentiation medium, as described above, for 2 days and then grown in NES differentiation medium with small molecules for another 4 days. Medium was changed every day. After 4 days, cells were cultured in NES differentiation medium with BDNF (10 ng/ml) and NT3 (10 ng/ml) for further 7 days. Half of the medium was changed every second day with double concentration of BDNF and NT3.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription (RT)

Total RNA was extracted using Trizole reagent (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was dissolved in 20 μl water (molecular biology grade water, Sigma). The concentration of total RNA was measured using a NanoDrop1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). 1 μg total RNA was treated with RNase free DNase (Invitrogen Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The DNase treated RNA was reverse-transcribed using a high capacity RNA to cDNA kit (Life Technologies), according to the manufacturer’s recommendation.

Real time polymerase chain reaction

Gene expression was quantified using an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real time PCR system, and SYBR Green master mix (Applied Biosystem). Commercially available KiCqStart primers for GATA3, Brn3a, Peripherin, Neurod1, 18S were purchased from Sigma. All reactions were performed in triplicate in SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems) in 96-well optical plates. For each reaction; 20 ng cDNA, 10 μl master mix, 0.5 μl primer and 5 μl water, were used. The PCR reaction was performed according to standard protocols of 40 cycles of denaturation-annealing. Normalization of mRNA was done using 18s ribosomal gene and relative expression level were reported as 2delta delta ct.

Immunocytochemisty

Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 minutes at room temperature and washed 3 times with PBS for 5 minutes. Cells were permeabilized with TTPBS (0.5% Triton X-100 + 1% Tween 20 in PBS) for 10 minutes at room temperature (RT), and exposed to blocking buffer (2% BSA in TTPBS) for 1 hr at RT. Primary antibodies, Brn3a (Millipore, 1:200), Tuj1 (Covance, 1:1000), Ki67 (Abcam, 1:200), active caspase3 (BD Pharmingen, 1:200) were diluted in blocking buffer and incubated with cells at 4°C overnight. Next day, cells were washed three times with TTPBS and secondary antibodies were applied; donkey anti-mouse cy3 diluted 1:400 (Jackson Immunoresearch), donkey anti-rabbit diluted 1:400 (Jackson Immunoresearch) for 2 hrs at RT. Cells were counter stained with DAPI. Positive cells were visualized in an LSM 700 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss). Pictures for analysis were obtained from 9-10 random fields (20X magnification), from 3 independent experiments. Numbers of positive cells were counted from each condition.

Statistics

The Graphpad prism software was used to perform all statistical analysis. Statistical differences were performed by One-way ANOVA, and Tukey’s multiple comparison test to determine significance level among groups.

Results

First we set out to analyse the optimal dose for treatment of the lt-NES cells, with the aim of finding a dose that did not affect proliferation or apoptosis. For treatments with SB431542 and metformin optimal doses have been published [11,16,20]. For ISX9, others have reported variations depending on cell lines [21], and titration experiments were thus performed on the Lt-NES cell lines used (C1GFP and AF22).

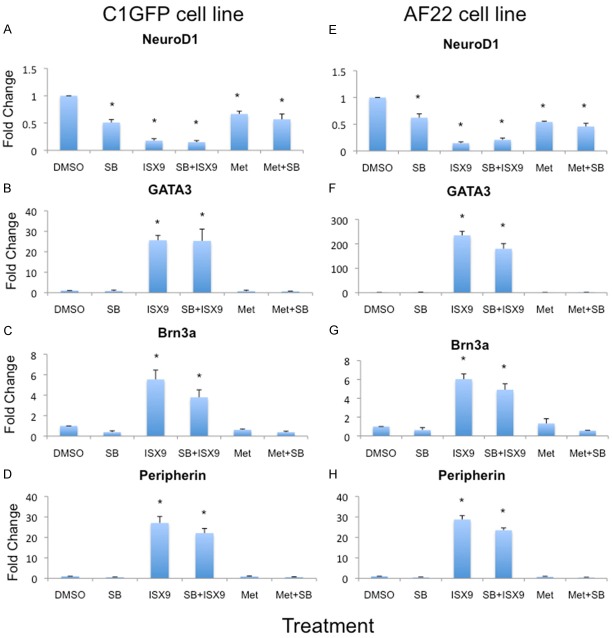

Four concentrations of ISX9 (5, 10, 20 and 40 μM) were first tested on It-NES cells regarding effects on proliferation (measured by Ki67-IHC) and apoptosis (measured by cleaved caspase3-IHC). The percentage of Ki67 positive cells was not affected by 5 or 10 μM ISX9, but significantly reduced by 20 μM and 40 μM (p<0.05. Figure 1A). Percentage of cells staining for cleaved caspase-3 was significantly decreased by 5 or 10 μM ISX9 (p<0.05), unaffected by 20 μM (NS), and increased by 40 μM (p<0.05. Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Dose-dependent response of ISX9 on lt-NES cells. (A) Quantitative analysis of the proliferative maker Ki67 showed that a higher dose of ISX9 significantly reduced proliferation in cells whereas (B) the apoptotic marker Cleaved Caspase 3 was seen to significantly increase at higher dose of ISX9. (C-E) The mRNA expression of NeuroD1 was significantly reduced in ISX9 treated cells. (D-F) At a higher dose of ISX9, GATA3 expression was significantly increased. Average of 3 experiments. Bars show mean ± SD. * = p<0.05.

Titrations for the effects on the expression of neural markers showed that NeuroD1 mRNA was significantly reduced following exposure to all tested doses of ISX9, compared to control treatment with DMSO (p<0.05. Figure 1C, 1E). We also analysed the expression of GATA3 following ISX9 treatment. GATA3 mRNA expression was significantly increased by 20 μM and 40 μM ISX9 (p<0.05. Figure 1D, 1F), but not at lower doses.

Thus, a concentration of 20 μM ISX9 was selected for the differentiation experiments described below.

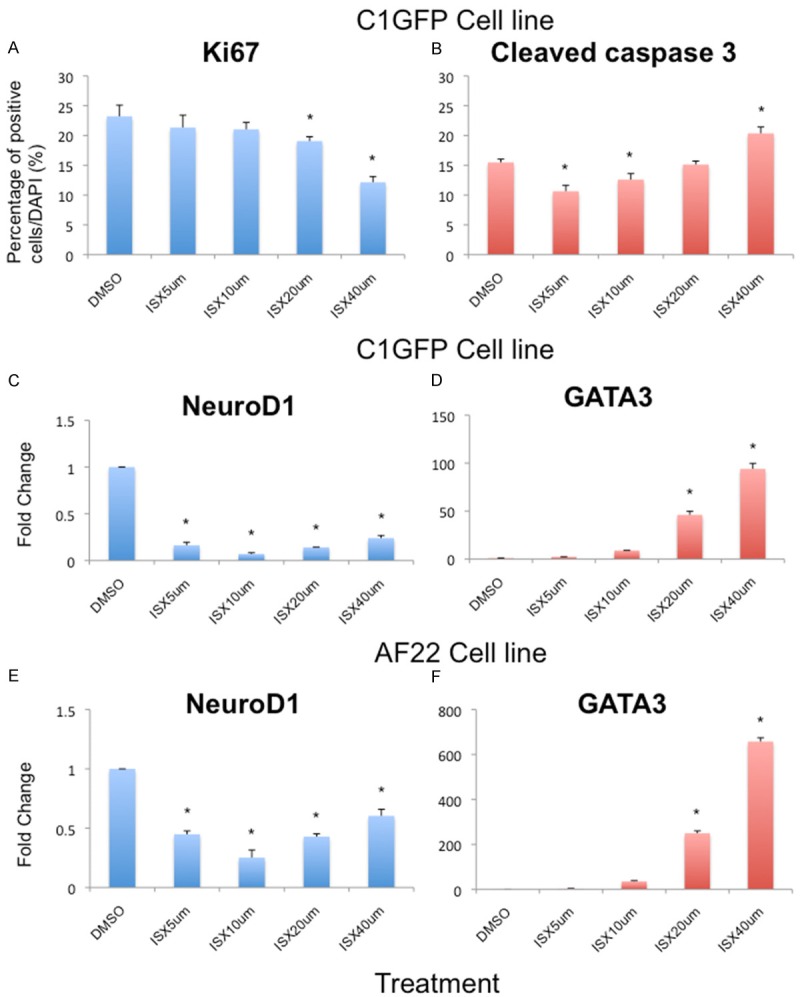

Effects on mRNA expression of sensory neural markers

An overview of the results from qPCR regarding mRNA expression of the sensory neural markers Brn3a, peripherin, GATA3 and NeuroD1 are summarised in Figure 2. In C1GFP cells, the mRNA expression of GATA3 was increased 25-fold after treatment with 20 μM ISX9 and the similar increase was obtained with a combination of ISX9 plus SB431542 (p<0.05. Figure 2B). In AF22 cells, the effects was even more pronounced with a 230-fold increase by treatment with ISX9 alone, and a 180-fold increase by the combination of ISX9 plus SB431542 (p<0.05. Figure 2F). In contrast, treatments with SB431542 and metformin did not induce any change in GATA3 in either of the It-NES cell lines.

Figure 2.

ISX9 induces mRNA expression of sensory neural markers. Gene expression analysis showed a significant increase in GATA3 (B, F), Brn3a (C, G) and peripherin (D, H) in ISX9 treated cells. The Brn3a and peripherin expression were in both cell lines similar but GATA3 expression were 10 times more in AF22 cells compared to C1GFP cells line. However, NeuroD1 expression was reduced in ISX9 treated cells compared to control (A, E). Average of 3 experiments. Bars show mean ± SD. * = p<0.05.

C1GFP cells exhibited a 27-fold increase in peripherin expression following exposure to ISX9 and a 22-fold increase by the combination treatment with ISX9 plus SB431542 (p<0.05 Figure 2D). In AF22 cells the results showed a 28- and 23-fold increase, from the ISX9 or ISX9 plus SB431542 treatments, respectively (p<0.05 Figure 2H).

Expression of Brn3a was 5,5- and 3,7-fold increased in C1GFP cells; and 7 and 5-fold increase in AF22 cells, from ISX9 or ISX9 plus SB431542 treatments, respectively (p<0.05, Figure 2C, 2G).

Effects on protein expression

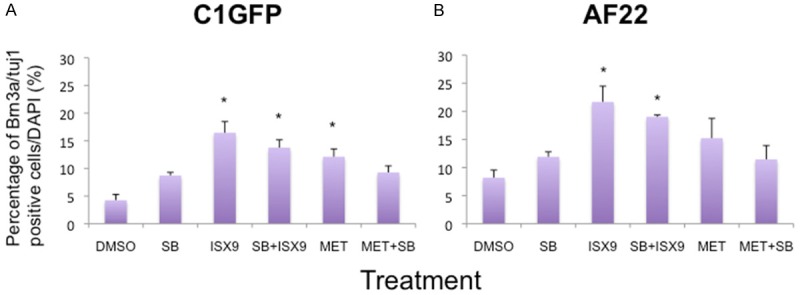

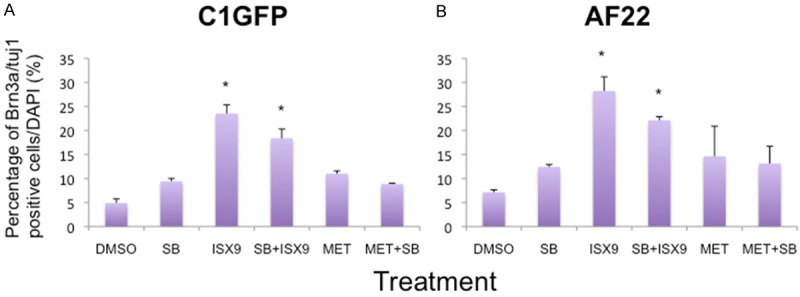

To confirm the mRNA results, we also performed immunocytochemistry for Brn3a and Tuj1 in combination to identify sensory neurons. A summary on the IHC data is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

ISX9 treatment induces an increased number of cells immunoreactive for Brn3a and Tuj1 at 4 days of treatment. The numbers of Brn3a and Tuj1 positive cells were significantly increased following ISX9 treatment, either alone or in combination of SB431542. However, metformin (MET) treatment resulted in a significantly increased number of positive cells in C1GFP cells line (A) but not in AF22 cell line (B). Average from 3 experiments. Bars show mean ± SD. * = p<0.05.

The frequencies of Brn3a/Tuj1 positive cells were significantly increased following exposure to ISX9 as well as from the combination treatment with ISX9 plus SB431542, when compared to control treatment (16% vs 14% in C1GFP (Figure 3A) and 22% vs 19% in AF22 (Figure 3B) p<0.05). A significant increase in Brn3a/Tuj1 positive cells was also obtained following metformin treatment of C1 GFP cells (12%; p<0.05), but not in AF22 cells (15%; NS).

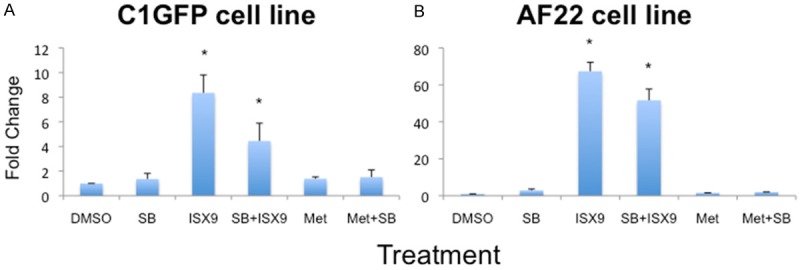

Further differentiation in the presence of neurotrophic factors

As it has been demonstrated that BDNF and NT3 are important for the survival of sensory neurons [22]. After 4 days of treatment with small molecules lt-NES cells were allowed to differentiate for another 7 days in the presence of the neurotrophic factors BDNF and NT3.

The addition of 7 days culture with neurotrophic factors induced no further change regarding mRNA levels of Brn3a or peripherin, in any of the treatment groups (data not shown). However, expression of GATA3 mRNA was significantly up-regulated in the ISX9 as well as in the ISX9+SB431542 treated cells (8- and 5-fold in C1GFP cells; 66- and 50-fold in AF22 cells, respectively) (p>0.05, Figure 4A, 4B). Also the percentages of cells positively immune-stained for Brn3a and Tuj1 were significantly increased in ISX9 and ISX9+SB431542 treated cells (23% vs 18% in C1GFP and 28% vs 22% in AF22), respectively (p>0.05, Figures 5A, 5B and 6).

Figure 4.

Expression of GATA3 after 4+7 days. Lt-NES cells were treated with the small molecules for 4 days and the cultured 7 more days in survival medium containing neurotrophic factors BDNF and NT3. After 4+7 days, GATA3 expression was induced in ISX9 and ISX9+SB431542 treated cells of both cell lines (A, B). Average from 3 experiments. Bars show mean ± SD. * = p<0.05.

Figure 5.

Quantitative analysis of the number of cells immunoreactive for Brn3a and Tuj1 4+7 after days. The frequencies of Brn3a and Tuj1 positive cells in ISX9 treated cells were significantly higher after 7 days of treatment (A, B). Both the cells lines showed similar pattern for positive cells, whereas no difference was seen between other treatments. Average from 3 experiments. Bars show mean ± SD. * = p<0.05.

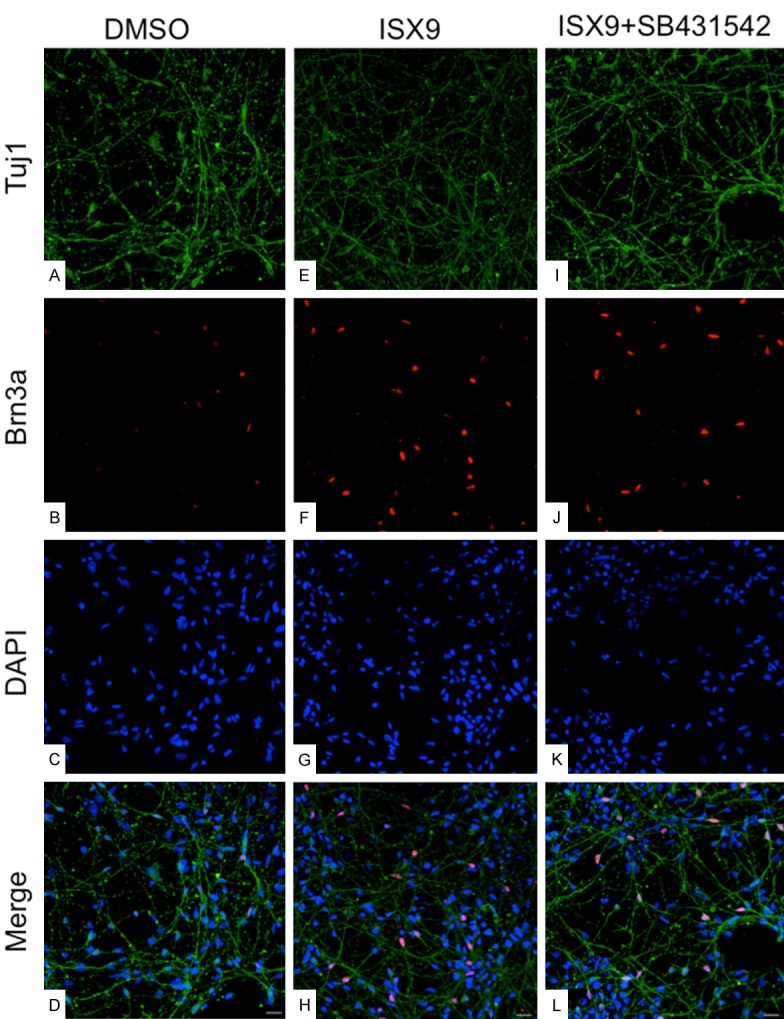

Figure 6.

Immunostaining for sensory neural markers after 4+7 days. Cells were treated with small molecules for 4 days and cultured additional 7 days in medium containing BDNF/NT3. After 4+7 days, cells were immunostained with Tuj1 (A, E, I) and Brn3a (B, F, J). Merged pictures in (D, H, L) for DMSO, ISX9 and ISX9+SB431542 respectively. Cells were counter-stained with DAPI (C, G, K). Magnification 20X.

Discussion

Human It-NES cell lines derived from human pluripotent stem cells have been shown to exhibit a capability to propagate in culture over long periods of time, while maintaining their capacity to differentiate into the neural linage [19]. Previously, it has been shown that It-NES cells can differentiate into different types of neurons, like dopaminergic neurons, motorneurons and cholinergic neurons [19,23,24]. It is, however, not known whether they also can differentiate into sensory neurons.

We have here tested the effects in two human It-NES cell lines from three separate small molecules, with suggested effects on the differentiation of sensory neurons.

Gou et al. showed that a combination of SB431542, noggin and wnt1 could induce differentiation of human neural progenitor cells into 50% of sensory neurons and 50% of Schwann cells [16]. In the present study, we did not observe an increase in the number of sensory neurons after a combination treatment with ISX9 and SB431542. It is possible that SB431542 has inhibiting effect on neuroepithelial cells as they are more committed towards neuronal cells.

The C1GFP and AF22 cell lines differed with regard to response to Metformin. While the frequency of cells staining positive for Brn3a/Tuj1 was increased in the C1GFP cell line, similar statistical difference was not obtained using the AF22 cell line.

It was previously reported that the transcription factors Neurog1 and NeuroD1 both play important roles during the specification and development of cochleo-vestribular ganglions [25,26]. Knockout studies in mice have demonstrated that deletion of Neurog1 or NeuroD1 affect the development of the cochleo-vestibular ganglion. In addition, Schneider and co-workers reported that the small molecule isoxazole 9 activated NeuroD expression in hippocampal neural stem cells and induced robust neuronal differentiation [10]. From these published data, we hypothesized that ISX9 could activate developmental genes for auditory neurons via the NeuroD1 gene. Based on mRNA and protein IHC analysis we here demonstrate that a four day treatment with the small molecule ISX9 induced expression of sensory neural markers in two lt-NES cell lines. However, the NeuroD1 expression was at this time point, contrary to the hypothesis, significantly reduced, leaving the suggested link to NeuroD1 obscure. Further analysis is needed to explore the mechanism, and e.g. a kinetic analysis of the NeuroD1 expression following ISX9 exposure may explain the induction of sensory neuronal markers.

Furthermore, a regimen when ISX9 was removed from the cultures and instead replaced with the presence of the neurotrophic factors BDNF and NT3 for another seven days, significantly increased the frequency of cells expressing markers for sensory neurons, up to 25-30%, (p<0.05). Our results showed here a significantly induced expression for GATA3, Brn3a, and peripherin as well as number of Brn3a/tuje positive cells in ISX9 treated cells. Expression of GATA3 is known to play a critical role in specification of auditory specification during early development [27,28]. A presence of GATA3 expression in mature stages of auditory neurons development has also been reported [27,29].

A four-day ISX9 treatment thus resulted in significantly increased expression of GATA3 and Brn3a as well as protein expression of Brn3a (immunohistochemistry). Prolonged culture in the presence of BDNF and NT3 lead to significant further increase in Brn3a/Tuj1 positive cells as well as GATA3 expression.

In conclusion, the present findings demonstrate that exposure to the small molecule ISX9 induces markers for auditory-like phenotypes in iPS derived lt-NES cells. Notably, contrary to hESC or hiPSC, Lt-NES cells lack in vivo pluripotency, i.e. the developmental potency for teratoma formation. An approach with ISX9 small molecule induction of lt-NES cells for the generation of auditory-like neurons may thus be an attractive route for obtaining cells for a replacement therapy of sensorineural hearing loss.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the AFA insurance company (dnr 110024; MU), the Swedish Research Council (MU grant nr 2010-7209, LAR grant nr K2008-55X-2034-01-3) and the KI-RGD network (LAR). Rouknuddin Ali was supported by a stipend from the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan (RA).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Holley MC. Keynote review: The auditory system, hearing loss and potential targets for drug development. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:1269–1282. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03595-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corwin JT, Cotanche DA. Regeneration of sensory hair cells after acoustic trauma. Science. 1988;240:1772–1774. doi: 10.1126/science.3381100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raphael Y. Cochlear pathology, sensory cell death and regeneration. Br Med Bull. 2002;63:25–38. doi: 10.1093/bmb/63.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morest DK, Cotanche DA. Regeneration of the inner ear as a model of neural plasticity. J Neurosci Res. 2004;78:455–460. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ulfendahl M, Hu Z, Olivius P, Duan M, Wei D. A cell therapy approach to substitute neural elements in the inner ear. Physiol Behav. 2007;92:75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parsons XH. Constraining the Pluripotent Fate of Human Embryonic Stem Cells for Tissue Engineering and Cell Therapy - The Turning Point of Cell-Based Regenerative Medicine. Br Biotechnol J. 2013;3:424–457. doi: 10.9734/BBJ/2013/4309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu T, Zhang M, Laurent T, Xie M, Ding S. Concise review: chemical approaches for modulating lineage-specific stem cells and progenitors. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2013;2:355–361. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2012-0172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li W, Li K, Wei W, Ding S. Chemical approaches to stem cell biology and therapeutics. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:270–283. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu Y, Shi Y, Ding S. A chemical approach to stem-cell biology and regenerative medicine. Nature. 2008;453:338–344. doi: 10.1038/nature07042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider JW, Gao Z, Li S, Farooqi M, Tang TS, Bezprozvanny I, Frantz DE, Hsieh J. Small-molecule activation of neuronal cell fate. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:408–410. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Gallagher D, DeVito LM, Cancino GI, Tsui D, He L, Keller GM, Frankland PW, Kaplan DR, Miller FD. Metformin activates an atypical PKC-CBP pathway to promote neurogenesis and enhance spatial memory formation. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inman GJ, Nicolas FJ, Callahan JF, Harling JD, Gaster LM, Reith AD, Laping NJ, Hill CS. SB-431542 is a potent and specific inhibitor of transforming growth factor-beta superfamily type I activin receptor-like kinase (ALK) receptors ALK4, ALK5, and ALK7. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:65–74. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chambers SM, Fasano CA, Papapetrou EP, Tomishima M, Sadelain M, Studer L. Highly efficient neural conversion of human ES and iPS cells by dual inhibition of SMAD signaling. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:275–280. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chambers SM, Qi Y, Mica Y, Lee G, Zhang XJ, Niu L, Bilsland J, Cao L, Stevens E, Whiting P, Shi SH, Studer L. Combined small-molecule inhibition accelerates developmental timing and converts human pluripotent stem cells into nociceptors. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:715–720. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morizane A, Doi D, Kikuchi T, Nishimura K, Takahashi J. Small-molecule inhibitors of bone morphogenic protein and activin/nodal signals promote highly efficient neural induction from human pluripotent stem cells. J Neurosci Res. 2010;89:117–126. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo X, Spradling S, Stancescu M, Lambert S, Hickman JJ. Derivation of sensory neurons and neural crest stem cells from human neural progenitor hNP1. Biomaterials. 2013;34:4418–4427. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.02.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El-Mir MY, Detaille D, R-Villanueva G, Delgado-Esteban M, Guigas B, Attia S, Fontaine E, Almeida A, Leverve X. Neuroprotective role of antidiabetic drug metformin against apoptotic cell death in primary cortical neurons. J Mol Neurosci. 2008;34:77–87. doi: 10.1007/s12031-007-9002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tailor J, Kittappa R, Leto K, Gates M, Borel M, Paulsen O, Spitzer S, Karadottir RT, Rossi F, Falk A, Smith A. Stem cells expanded from the human embryonic hindbrain stably retain regional specification and high neurogenic potency. J Neurosci. 2013;33:12407–12422. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0130-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Falk A, Koch P, Kesavan J, Takashima Y, Ladewig J, Alexander M, Wiskow O, Tailor J, Trotter M, Pollard S, Smith A, Brustle O. Capture of neuroepithelial-like stem cells from pluripotent stem cells provides a versatile system for in vitro production of human neurons. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29597. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vallier L, Reynolds D, Pedersen RA. Nodal inhibits differentiation of human embryonic stem cells along the neuroectodermal default pathway. Dev Biol. 2004;275:403–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schuldiner M, Eiges R, Eden A, Yanuka O, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Goldstein RS, Benvenisty N. Induced neuronal differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Brain Res. 2001;913:201–205. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02776-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ernfors P, Van De Water T, Loring J, Jaenisch R. Complementary roles of BDNF and NT-3 in vestibular and auditory development. Neuron. 1995;14:1153–1164. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90263-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujimoto Y, Abematsu M, Falk A, Tsujimura K, Sanosaka T, Juliandi B, Semi K, Namihira M, Komiya S, Smith A, Nakashima K. Treatment of a mouse model of spinal cord injury by transplantation of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived long-term self-renewing neuroepithelial-like stem cells. Stem Cells. 2012;30:1163–1173. doi: 10.1002/stem.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang D, Pekkanen-Mattila M, Shahsavani M, Falk A, Teixeira AI, Herland A. A 3D Alzheimer’s disease culture model and the induction of P21-activated kinase mediated sensing in iPSC derived neurons. Biomaterials. 2014;35:1420–1428. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim WY, Fritzsch B, Serls A, Bakel LA, Huang EJ, Reichardt LF, Barth DS, Lee JE. NeuroD-null mice are deaf due to a severe loss of the inner ear sensory neurons during development. Development. 2001;128:417–426. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.3.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma Q, Anderson DJ, Fritzsch B. Neurogenin 1 null mutant ears develop fewer, morphologically normal hair cells in smaller sensory epithelia devoid of innervation. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2000;1:129–143. doi: 10.1007/s101620010017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duncan JS, Fritzsch B. Continued expression of GATA3 is necessary for cochlear neurosensory development. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duncan JS, Lim KC, Engel JD, Fritzsch B. Limited inner ear morphogenesis and neurosensory development are possible in the absence of GATA3. Int J Dev Biol. 2011;55:297–303. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.103178jd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karis A, Pata I, van Doorninck JH, Grosveld F, de Zeeuw CI, de Caprona D, Fritzsch B. Transcription factor GATA-3 alters pathway selection of olivocochlear neurons and affects morphogenesis of the ear. J Comp Neurol. 2001;429:615–630. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20010122)429:4<615::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]