Abstract

Background:

Ipilimumab is an anticytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) monoclonal antibody used for the treatment of malignant melanoma. It can cause immune-mediated inflammatory adverse events, including diarrhoea and even intestinal perforation or death in clinical trials but there is a dearth of data on postmarketing outcomes.

Methods:

A total of 546 patients attending for treatment of metastatic melanoma between 1 January 2009 and 31 August 2015 were identified by interrogation of the oncology database. A total of 83 of these patients received ipilimumab. Clinical information was extracted from chart reviews, endoscopy and radiology reports, and prescription data.

Results:

A total of 83 patients received ipilimumab. Only 19.3% (n = 16) of patients developed a diarrhoeal illness not attributable to other causes. The median grade of diarrhoea among included patients was 2 (range 1–4). In two cases, diarrhoea settled spontaneously without any specific treatment. A total of 87.5% of patients received antidiarrhoeal agents such as loperamide or codeine. These resolved symptoms in all patients with grade 1 diarrhoea. For other treatment, 50% patients received systemic glucocorticosteroids and 31.3% required infliximab. Infliximab resolved symptoms in 100% of cases compared with 50% for systemic glucocorticosteroids.

Conclusions:

The rate of diarrhoea related to ipilimumab in real-world practice is substantial, but below the range observed in data from RCTs. Grade 1 colitis can usually be managed symptomatically, without recourse to stopping ipilimumab. When diarrhoea was grade 2 or above, results from glucocorticosteroids use proved disappointing; but infliximab has been shown to work well. Further research is required into the earlier use of infliximab as an effective treatment for ipilimumab-induced diarrhoea.

Keywords: colitis, diarrhoea, infliximab, ipilimumab, melanoma

Introduction

Ipilimumab is an anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) monoclonal antibody that attenuates negative signalling from CTLA-4 and potentiates T-cell activation and proliferation. It currently holds regulatory approval in the US and Europe for the treatment of malignant melanoma, having been shown to extend median overall survival at 1, 2 and 3 years [Hodi et al. 2010, Robert et al. 2011]. The approved dose of ipilimumab is 3 mg/kg body weight every 3 weeks, given up to a total of four scheduled infusions. Efficacy has also been proposed in other advanced malignancies such as prostate cancer, non-small cell lung cancer and renal cell carcinoma (RCC), often at doses up to 10 mg/kg [Reck et al. 2013; Kwon et al. 2014].

Antibody inhibition of CTLA-4 can cause immune-mediated inflammatory adverse events, which are thought to be a direct result of potentiation of activity of T- cells and commonly involve the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. These can include diarrhoea in 27–31% of patients, and even intestinal perforation or death, occurring in less than 1% of patients [Hodi et al. 2010; Ibrahim et al. 2011]. Enterocolitis, defined by the presence of severe symptoms (grade 3 or 4 as outlined below) or documented by biopsy, was the most common severe immune-mediated adverse event associated with ipilimumab use, occurring in 21% of patients [Beck et al. 2006].

Colitis can manifest somewhat unpredictably after anti-CTLA-4 administration. The summary of product characteristics for ipilimumab states that the median time of onset of severe gastrointestinal reactions is 8 weeks from the start of ipilimumab, with a range of 5–13 weeks [Bristol-Myers Squibb Pharmaceutical Limited, 2015]. However, one study found that the onset of enterocolitis could be after 1–10 cycles of ipilimumab, although the doses varied [Beck et al. 2006]. There may also be a dose effect, and in one study of patients with RCC the incidence of enterocolitis among patients receiving higher doses of ipilimumab was more than twofold that of patients receiving lower doses (35% versus 14%) [Reck et al. 2013].

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis estimated the incidence of watery diarrhoea with anti-CTLA-4 therapy to be 27–54%, and the presence of diffuse acute or chronic colitis at lower endoscopy to be between 8% and 22% [Gupta et al. 2015]. This review also reported high rates of treatment success with glucocorticosteroids and infliximab. However, all of the included studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs). There is currently no postmarketing, real-world data on the incidence and management of diarrhoeal complications in patients receiving ipilimumab in the GI literature, other than isolated case reports.

Aims and methods

We aimed to ascertain the prevalence of diarrhoea or colitis occurring among patients who received ipilimumab at our centre, to collate the endoscopic and radiological findings where these were available, and to assess the treatments used and the outcomes of patients.

Study population

All patients who had received ipilimumab for the treatment of metastatic melanoma between 1 January 2009 and 31 August 2015 were identified by interrogation of the trust oncology database. Our institution is a large university teaching hospital trust that serves an urban population of 850,000 in the north of England and accepts tertiary oncology referrals from a hinterland with a population of 2.3 million. Annual median incidence of stage 4 metastatic melanoma over the study period is 94 per annum. Cases were reviewed by a consultant gastroenterologist and excluded patients who had an alternative cause for diarrhoea, such as infective colitis or chronic idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. None of the patients had pre-existing inflammatory bowel disease.

Definitions

Definitions of diarrhoea and colitis were based on the National Cancer Institutes’ common terminology criteria for adverse events version 3 [US National Institutes of Health, 2006]. This was also the grading used in the clinical trials of ipilimumab [Gupta et al. 2015]. Grade 1 diarrhoea was defined as loose or watery stool, with an increase of less than four stools per day over baseline. Grade 2 diarrhoea was an increase of between four to six stools per day over baseline with or without the need for intravenous (IV) fluids for less than 24 hours, but not interfering with activities of daily living (ADL). Grade 3 diarrhoea was defined as an increase of at least seven stools per day over baseline, incontinence, more prolonged intravenous fluids, interfering with ADL, or hospitalization. Grade 4 diarrhoea comprised life-threatening consequences such as hemodynamic collapse, surgery, or intestinal perforation.

Grade 1 colitis was defined as being asymptomatic, with pathologic or radiological findings only. Grade 2 colitis involved abdominal pain, and mucus or blood in the stool. Grade 3 colitis included abdominal pain, fever, and change in bowel habit with ileus or peritoneal signs. Grade 4 colitis included life-threatening consequences, such as hemodynamic collapse, surgery, intestinal perforation or necrosis, or toxic megacolon.

Data extraction

Clinical information was extracted from chart reviews, endoscopy and radiology reports, and prescription data.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as median and range (minimum and maximum) and categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test with Yates’ correlation. A two-tailed p value of < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All analyses were conducted using SPSS for windows version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, US).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Over the course of the study period, 546 patients with metastatic melanoma were seen and we identified 83 of those patients who received ipilimumab (15.2%). In all cases, the drug was delivered at a dose of 3 mg/kg for metastatic melanoma. Ipilimumab was not used for any other indication in our institution. Of these, 60.2% (n = 50) were male. Median age was 60 years (range 23–81 years). In total, 19.3% (n = 16) of patients developed a diarrhoeal illness not attributable to other causes. One further patient developed a self-limiting illness commensurate with infectious diarrhoea, but with normal stool cultures 3 months after completing their fourth and final cycle of ipilimumab, and another had Clostridium difficile-induced diarrhoea after cycle 1 and completed the course without further diarrhoea, after having antibiotic treatment. Median age was similar in those developing diarrhoea (59 years) compared with those who did not (60 years). Incidence of diarrhoea in female patients and male patients was also similar (21% versus 20%). A total of 8% (n = 7) of the patients were taking proton pump inhibitors while receiving ipilimumab; two of those went on to develop diarrhoea. A total of 7% (n = 6) had antimicrobial therapy within 3 months prior to ipilimumab; two of these went on to develop diarrhoea. The characteristics of patients developing diarrhoea are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients developing diarrhoea.

| Gender | Age | Grade of diarrhoea | Grade of colitis | Cycle after which symptoms commenced | Weeks after commencement of therapy | Drug stopped |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 59 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 8 | Yes |

| Female | 73 | 1 | N/A | 2 | 4 | No |

| Female | 42 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Yes |

| Female | 43 | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | No |

| Female | 49 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 11 | No |

| Female | 59 | 1 | N/A | 2 | 5 | No |

| Female | 31 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 7 | Yes |

| Male | 81 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 8 | Yes |

| Male | 65 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 7 | Yes |

| Male | 52 | 1 | N/A | 1 | 2 | No |

| Male | 78 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | Yes |

| Male | 35 | 1 | N/A | 2 | 4 | No |

| Male | 50 | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | No |

| Male | 70 | 3 | N/A | 2 | 4 | No |

| Male | 68 | 1 | N/A | 2 | 4 | No |

| Male | 68 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 5 | Yes |

| Male | 53 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 6 | Yes |

The median grade of diarrhoea among included patients was 2 (range 1–4). Of those with diarrhoea, 43.8% (n = 7) had grade 1 symptoms, 12.5% (n = 2) had grade 2, and 43.8% (n = 7) had grade 3 symptoms. No patient had grade 4 diarrhoea. Five patients developed diarrhoea after their first cycle of therapy, six after cycle 2, four after cycle 3, and one after cycle 4. The patient level outcomes are outlined in Table 2. There were no incidences of intra-abdominal sepsis, perforation or death. One patient who had received steroids to treat colitis developed septic arthritis.

Table 2.

Outcomes of drug therapy for ipilimumab-induced diarrhoea.

| Treatment used | Patients who responded to/received treatment |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 diarrhoea (n = 7) | Grade 2 diarrhoea (n = 2) | Grade 3 diarrhoea (n = 7) | Grade 4 diarrhoea (n = 0) | Overall | |

| Antidiarrhoeals (loperamide or codeine) | 5/5 | 0/2 | 1/7 | N/A | 6/14 (42.9%) |

| Systemic glucocorticosteroids | N/A | 1/2 | 3/6 | N/A | 4/8 (50%) |

| Oral | N/A | 1/1 | 3/6 | N/A | 4/7 (57.1%) |

| IV | N/A | 0/1 | 0/2 | N/A | 0/3 (0%) |

| Infliximab | N/A | 1/1 | 4/4 | N/A | 5/5 (100%) |

Investigation

Of the patients developing ipilimumab-induced diarrhoea, 75% (n = 12) had their lower GI tract investigated, 43.8% (n = 7) had a flexible sigmoidoscopy and 68.8% (n = 11) had radiologic imaging in the form of computed tomography (CT). There were four patients, all of whom had grade 1 diarrhoea, who did not undergo any investigation. Of the seven patients undergoing sigmoidoscopy, all had colitis, with four having extensive colitis (with continuous changes noted beyond the splenic flexure); two having left-sided colitis, and one having a segmental transverse colitis. Histologically, all biopsies in patients with colitis described nonspecific colitis with crypt distortion without pseudomembranes or granulomata. Among the 11 patients who underwent CT imaging, two were noted to have extensive colitis, two had a left-sided colitis and seven were noted to not have any colitis. In three instances there was no evidence of colitis on CT, despite the fact that sigmoidoscopy had confirmed its presence. In one other instance, radiological appearances suggested a left-sided colitis, but sigmoidoscopy demonstrated extensive colitis. In the eight patients where an endoscopic or radiologic diagnosis of colitis was obtained, four patients had grade 2 and four had grade 3 colitis.

Treatment

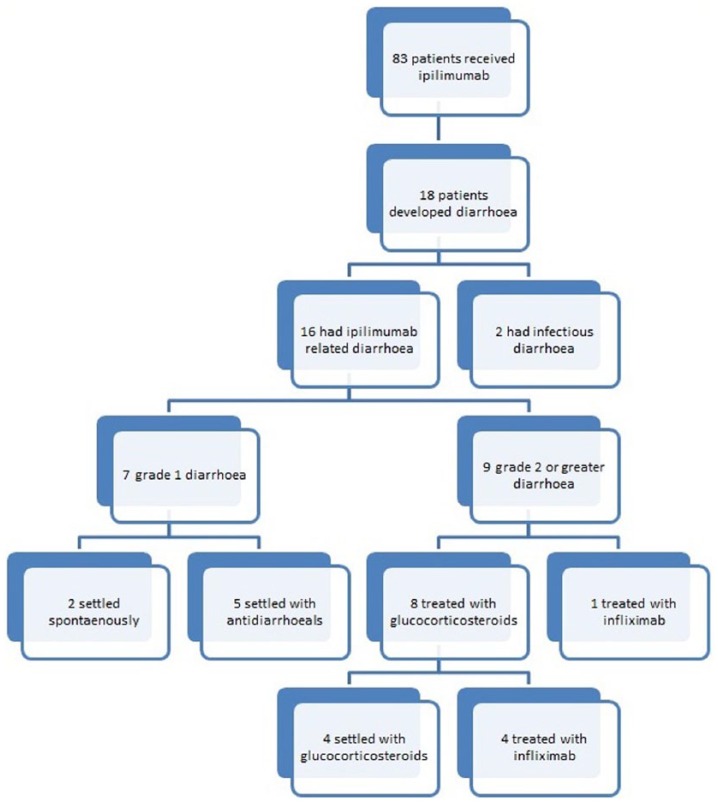

In 2 of the 16 cases, diarrhoea settled spontaneously without any specific treatment. The other 14 (87.5%) patients received antidiarrhoeal agents such as loperamide or codeine. All five of treated patients with grade 1 diarrhoea settled with antidiarrhoeals alone. Nine patients with diarrhoea grade 2 or greater received either glucocorticosteroids or infliximab. In total, eight (50%) patients received systemic glucocorticosteroids, and four of those, having failed to settle, required infliximab therapy (see Figure 1). One patient with grade 3 diarrhoea received primary infliximab therapy without having had glucocorticosteroids, due to severity of symptoms and previous severe adverse effects from steroid use, giving a total of five patients (31.3%) with ipilimumab-related diarrhoea who received infliximab. Oral glucocorticosteroids were delivered at doses of 0.75–1 mg/kg prednisolone. Intravenous hydrocortisone was used at a dose of 100 mg qds. Infliximab was delivered at a dose of 5 mg/kg, with three patients receiving one infusion, and two receiving a second. Antidiarrhoeals, when used, resolved symptoms in all patients with grade 1 diarrhoea. For patients with grade 2 diarrhoea or above, infliximab resolved symptoms in 100% of cases compared with 50% for systemic glucocorticosteroids. The outcomes of treatment are summarized in Table 2. Overall, 50% (n = 8) had to discontinue treatment due to the severity of the symptoms, with seven of these patients having grade 3 diarrhoea and one having grade 2.

Figure 1.

Flow through study.

Discussion

Our study illustrates a rate of diarrhoea related to ipilimumab in real-world practice that is substantial, but below the range observed in data from RCTs. There did not appear to be any age- or sex-based differences between those who developed diarrhoea and those who did not. The timing of presentation was unpredictable, again correlating with RCT data. Although the majority (68.8%) of our patients developed diarrhoea within two cycles of treatment, symptoms still occurred well after the chemotherapy regimen had become established. The severity of symptoms was also quite variable, with 56.3% presenting with grade 1 or 2 diarrhoea and 43.7% having grade 3 or 4 symptoms.

While lower GI endoscopy remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of ipilimumab-induced colitis, the finding of a patient with a segmental transverse colitis is notable. More proximal lesions such as this are often beyond the scope of a limited flexible sigmoidoscopy examination, which is mostly the standard of care [Berman et al. 2010]. We also observed considerable variation between endoscopic and radiological findings. This may indicate that definitive radiological diagnosis of this condition is elusive and when colitis is suspected, that direct endoscopic visualization is necessary.

Regarding treatment, it appears that grade 1 colitis can usually be managed symptomatically, without recourse to stopping ipilimumab. When grade 2 or above symptoms are noted, most algorithms have advocated the use of glucocorticosteroids and at least temporary discontinuation of the drug, with the most benefit being shown when steroids are used within 5 days of symptom onset [O’Day et al. 2011; Andrews and Holden, 2012]. Ensuring such promptness of action is more difficult outside of a clinical trial setting, and the results for glucocorticosteroid use in our observational study were disappointing, with intravenous hydrocortisone not appearing to offer any benefit in the small number of patients who received it. Infliximab has been shown to work well for diarrhoea in RCTs across all indications for ipilimumab [Beck et al. 2006; Hodi et al. 2010; O’Day et al. 2011; Slovin et al. 2013; Wolchok et al. 2010; Yang et al. 2007]. Although the presence of metastatic malignancy would usually be considered a contraindication for the use of infliximab, in this setting it has been considered necessary, and shown in the relatively small number of cases to be efficacious, in preventing colectomy in fulminant ipilimumab-induced colitis.

Our study has several limitations. It was a retrospective, descriptive single-centre analysis. Numbers were small, which made it difficult to identify any predictive factors. As some patients were referred in from other regional centres, fully verified premorbid medication (including, in some cases, prior full chemotherapy history) was not always available. For the same reasons, another limitation is the inability to characterize this cohort of patients also with respect to imaging or endoscopic evaluations prior to the start of ipilimumab. In our centre, ipilimumab was only used for melanoma. In published trial data, comparable rates of diarrhoea were noted for patients receiving 3 mg/kg ipilimumab for renal and pancreatic cancers [Royal et al. 2010; Yang et al. 2007]. Much higher rates of diarrhoea (54%) were reported for patients receiving high doses of ipilimumab (10 mg/kg) for prostate cancer [Slovin et al. 2013].

In the management of acute severe exacerbations of ulcerative colitis, it is an accepted principle that infliximab as a rescue therapy is most efficacious when given earlier [Mowat et al. 2011]. We suggest that further research is required into the earlier use of infliximab as an effective treatment for ipilimumab-induced diarrhoea. In addition, further data on stool and serum biomarkers, as well as the utility of flexible sigmoidoscopy versus full colonoscopy as diagnostic tools, would be beneficial. It may also be useful to screen patients for conditions such as viral hepatitis and tuberculosis prior to initiation of therapy, given the possible need for infliximab.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: Anthony O’Connor received a travelling fellowship grant from MSD Human Health, Ireland in 2013. Maria Marples has received sponsorships to meetings from, and been a member of an advisory board for, Bristol-Myers Squibb. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Anthony O’Connor, Leeds Gastroenterology Institute, Bexley Wing, St. James’s University Hospital, Beckett Street, Leeds LS9 7TF, UK.

Maria Marples, St James’s Institute of Oncology, St. James’s University Hospital, Leeds, UK.

Clive Mulatero, St James’s Institute of Oncology, St. James’s University Hospital, Leeds, UK.

John Hamlin, Leeds Gastroenterology Institute, St. James’s University Hospital, Leeds, UK.

Alexander C. Ford, Leeds Gastroenterology Institute, St. James’s University Hospital, Leeds, UK Leeds Institute of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK

References

- Andrews S., Holden R. (2012) Characteristics and management of immune related adverse effects associated with ipilimumab, a new immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma. Cancer Manag Res 4: 299–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck K., Blansfield J., Tran K., Feldman A., Hughes M., Royal R., et al. (2006) Enterocolitis in patients with cancer after antibody blockade of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. J Clin Oncol 24: 2283–2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman D., Parker S., Siegel J., Chasalow S., Weber J., Galbraith S., et al. (2010) Blockade of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 by ipilimumab results in dysregulation of gastrointestinal immunity in patients with advanced melanoma. Cancer Immun 10: 11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristol-Myers Squibb Pharmaceutical Limited (2015) Ipilimumab SPC. Available at: http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/24779 (accessed 13 September 2015).

- Gupta A., De Felice K., Loftus E., Jr., Khanna S. (2015) Systematic review: colitis associated with anti-CTLA-4 therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 42: 406–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodi F., O’Day S., McDermott D., Weber R., Sosman J., Haanen J, et al. (2010) Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 363: 711–723. Erratum in: N Engl J Med 363: 1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim R., Berman D., DePril V., Humphrey W., Chen T., Messina M., et al. (2011) Ipilimumab safety profile: summary of findings from completed trials in advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol 29: 15. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon E., Drake C., Scher H., Fizazi K., Bossi A., van der Eertweghet A., et al. (2014) Ipilimumab versus placebo after radiotherapy in patients with metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer that had progressed after docetaxel chemotherapy (CA184-043): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase III trial. Lancet Oncol 15: 700–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowat C., Cole A., Windsor A., Ahmad T., Arnott I., Driscoll R., et al. (2011) Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 60: 571–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Day S., Weber J., Wolchok J., Richards J, Lorigan D, McDermott D., et al. (2011) Effectiveness of treatment guidance on diarrhea and colitis across ipilimumab studies. J Clin Oncol 29: abstract 8554. [Google Scholar]

- Reck M., Bondarenko I., Luft A., Serwatowski P., Barlesi F., Chacko R., et al. (2013) Ipilimumab in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin as first-line therapy in extensive-disease-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomized, double-blind, multicenter phase II trial. Ann Oncol 24: 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert C., Thomas L., Bondarenko I., O’Day S., Weber J., Garbe C., et al. (2011) Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 364: 2517–2526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal R., Levy C., Turner K., Mathur A., Hughes M., Kammula U., et al. (2010) Phase II trial of single agent Ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4) for locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Immunother 33: 828–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slovin S., Higano C., Hamid O., Tejwani S., Harzstark A., Alumkal J., et al. (2013) Ipilimumab alone or in combination with radiotherapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: results from an open-label, multicenter phase I/II study. Ann Oncol 24: 1813–1821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US National Institutes of Health (2006) Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. Common terminology criteria for adverse events v3.0 (CTCAE). Available at: http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcaev3.pdf (accessed 4 September 2015).

- Wolchok J., Neyns B., Linette G., Negrier S., Lutzky J., Thomas L. (2010) Ipilimumab monotherapy in patients with pretreated advanced melanoma: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase II, dose-ranging study. Lancet Oncol 11: 155–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Hughes M., Kammula U., Royal R., Sherry R., Topalian S., et al. (2007) Ipilimumab (anti-CTLA4 antibody) causes regression of metastatic renal cell cancer associated with enteritis and hypophysitis. J Immunother 30: 825–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]