Abstract

Background

Understanding of doctors’ attitudes towards disclosing their own mental illness has improved but assumptions are still made.

Aims

To investigate doctors’ attitudes to disclosing mental illness and the obstacles and enablers to seeking support.

Methods

An anonymous, UK-wide online survey of doctors with and without a history of mental illness. The main outcome measure was likelihood of workplace disclosure of mental illness.

Results

In total, 1954 doctors responded and 60% had experienced mental illness. There was a discrepancy between how doctors think they might behave and how they actually behaved when experiencing mental illness. Younger doctors were least likely to disclose, as were trainees. There were multiple obstacles which varied across age and training grade.

Conclusions

For all doctors, regardless of role, this study found that what they think they would do is different to what they actually do when they become unwell. Trainees, staff and associate speciality doctors and locums appeared most vulnerable, being reluctant to disclose mental ill health. Doctors continued to have concerns about disclosure and a lack of care pathways was evident. Concerns about being labelled, confidentiality and not understanding the support structures available were identified as key obstacles to disclosure. Addressing obstacles and enablers is imperative to shape future interventions.

Key words: Health behaviour, physician health, physician impairment, mental health, survey.

Introduction

Improving the quality and effectiveness of patient care is high on the international agenda. In the UK, following the Francis inquiry [1], there are increasing demands on health care practitioners to be more patient-centred and vigilant in how care is delivered. To provide such quality of care, it is recognized that the health and well-being of the whole health care team is of high importance [2]. The health and well-being of doctors, and in particular their mental health, has led to doctors being under particular scrutiny following the introduction of revalidation by professional regulatory requirements.

Rates of mental illness are higher in doctors than in the general population [3] and the risk of suicide among doctors is higher than in many other occupations [4]. In the UK, doctors often find themselves under extreme pressure when being referred to the General Medical Council (GMC) in relation to a complaint or investigation of health concerns [5].

A regional UK study found that ~8% of doctors surveyed would choose not to turn to anyone for treatment of mental illness, preferring to self-medicate or have no treatment at all [6]. Some efforts doctors make to cope with symptoms of mental illness can become maladaptive, leading them to self-manage and avoid disclosure. A survey of UK doctors attending the Practitioner Health Programme found that addictions were the most common diagnoses after depression [7], and the British Medical Association (BMA) has estimated that 1 in 15 doctors have some form of drug or alcohol dependency at some point in their career [8].

A host of psychological and socio-cultural factors affect a doctor’s decision to disclose. In the general population, women are more likely to seek help for mental ill health than men [9]. Among doctors, the pattern of help seeking by gender has not been established, although it is known that female doctors are less likely to turn to colleagues [10].

There seems to be a relationship between a doctor’s speciality and their illness behaviours. In a study of doctors’ suicides, anaesthetists, community health doctors, general practitioners (GPs) and psychiatrists had significantly increased rates of suicide compared with general hospital doctors [4]. In terms of reasons for disclosure, differences were found between grade and career levels [6]. It has been noted by one group providing services for UK doctors over many years that more young doctors than consultants attended for support [11].

Across the UK, the provision and accessibility of mental health services for doctors varies widely. Obstacles identified in obtaining support include lack of knowledge about where to find help and the professional implications of seeking it [12]. Long work hours and shifts can impede access, and this problem is exacerbated in isolated geographic locations [13].

A number of studies have explored general attitudes towards mental illness in medicine but few have focused specifically on stigma among doctors. A UK regional postal survey among doctors found that those perceiving high levels of stigma were significantly less likely to report that they would seek help from GPs or colleagues and more likely to report that they would not seek help from anyone [6]. This was echoed in an Irish study, where 12% of doctors would not seek help at all [14].

In summary, aspects of doctors’ illness behaviour that affect self-disclosure have been explored. However, organizational factors and the major obstacles and en ablers from the doctors’ perspective are not yet fully understood. This study aimed to address such issues and provide insight into how targeted interventions may be introduced or enhanced to support doctors more effectively.

Methods

Doctors throughout the UK were invited, regardless of whether or not they had personally experienced mental ill health, to participate in an anonymous online questionnaire exploring their attitudes to disclosure of mental ill health at work.

The questionnaire contained both categorical items and free text responses and was designed to take 10min to complete. Pathways through the questionnaire were dependent on two main questions. The first asked whether doctors had experienced mental ill health or not. Doctors who had not personally experienced symptoms of mental ill health were asked what they might do if they were to experience mental ill health in the future; those who had already experienced mental ill health were asked to describe their personal experiences. The second question asked whether doctors would, or did disclose their mental ill health in their workplace. At each step, the doctor would be directed to a specific set of questions dependent on their response. A cognitive debrief was conducted prior to dissemination.

The questionnaire was published online using the Bristol Online Survey (BOS) tool and was distributed across the UK. To reach as broad a population as possible, social media, targeted emails, e-newsletters and bulletins, announcements on websites and printed newsletters were used; professional organizations such as the BMA and Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) assisted with distribution. The study obtained ethics approval from Cardiff University’s School of Medicine Research Ethics Committee (SMREC reference 13/43). Data were exported from BOS and analysed in Stata 13.

The analysis was undertaken in two stages: firstly, we examined the association between a number of demographic factors and the likelihood of having disclosed or intending to disclose mental ill health. Disclosure was dichotomized and based on experience of mental ill health; those who had experienced mental ill health stated whether they did disclose and those who had not experienced mental ill health stated whether they would disclose if they experienced poor mental health. The ana lysis modelled the odds ratio of disclosure utilizing a multilevel model with individuals at level one nested within regions. The model covariates included gender, age group, role, employment status, years since qualifying, ethnicity, whether the participants had received specific mental health training and whether the participant had ever experienced mental ill health. The subsequent analysis of the questionnaire items was divided into four subgroups. The second, descriptive analysis examined the differences between these groups with regard to the impact of symptoms on work, onset of symptoms, level of training, type of disorder, reasons for disclosure/non-disclosure, who to disclose to and factors important to disclosure.

Results

The online questionnaire yielded 1954 responses from the four countries of the UK, representing ~1% of the total UK doctor population. Eight questionnaires did not fulfil the inclusion criteria of being completed by qualified doctors and were therefore excluded. This led to 1946 responses with 1048 of these answering about their actual disclosure or intention to do so.

Sixty per cent of respondents were female. The gender ratio was similar across all four countries and differs from the general demographic of UK doctors (44% female). The proportion of doctors who had experienced mental ill health was 60% in Wales, 45% in Scotland, 55% in Northern Ireland and 82% in England. The age profile of doctors was evenly spread. Thirty-four per cent were doctors in training, 32% hospital consultants and 20% GPs. Seventy-six per cent of doctors were married or cohabiting, and 72% identified themselves as White British. Sixty per cent of doctors overall had experienced symptoms of mental ill health. Thirty-nine per cent of all respondents said they had received information or training on taking care of their own mental health and well-being.

Overall, 54% (1048) would or did disclose. For those who had not experienced mental ill health, 73% (570) stated that they would disclose at work. However, for those who had experienced mental ill health, 41% (478) stated they did disclose. This pattern did not differ across role. Looking at overall likelihood of disclosure (‘would disclose’ and ‘did disclose’ combined), staff and associate speciality/locum doctors and trainees were the least likely to disclose (49 and 51%, respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Likelihood of disclosure of mental ill health by role from total sample

| Role | Disclosure, N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Would disclose (no mental health symptoms, n = 570) | Did disclose (had mental health symptoms, n = 478) | Overall willingness to disclose (no mental health/had mental health symptoms combined, n = 1048) | |

| Doctor in training | 175 (62) | 152 (39) | 327 (51) |

| Consultant | 220 (79) | 156 (44) | 376 (62) |

| GP | 113 (84) | 102 (39) | 215 (61) |

| SAS/locum/other | 62 (60) | 68 (38) | 130 (49) |

SAS, staff and associate speciality.

The association between a number of demographic factors and likelihood of either actually disclosing or intending to do so is described in Table 2. The model has a small number of missing cases where participants did not answer all questions (54, 2%); these cases did not differ from those included in terms of age, gender and role. The analysis shows that willingness to disclose was positively associated with female gender, increasing age, being off sick and not having experienced symptoms of mental ill health. Neither role nor having received information or training in mental health were associated with disclosure intentions in a multivariate model. Due to small numbers in non-White ethnic groups, it is not possible to make reliable conclusions about likelihood of disclosure, although there seemed to be a reduction in the likelihood of disclosure for those reporting their ethnicity as Black. The multilevel model showed an intraclass correlation of 1.5%, which suggests that very little of the variance was attributable to regional differences.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of demographic factors and the odds of experience of and intention to disclose mental ill health (n = 1915, number of respondents with full data)

| Number (%) | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 1135 (59) | 1.3* | 1.04, 1.58 |

| Age | |||

| 18–24 | 51 (3) | 1 | Ref. |

| 25–29 | 282 (15) | 1.8 | 0.92, 3.53 |

| 30–34 | 297 (15) | 2.4* | 1.2, 4.94 |

| 35–39 | 245 (13) | 2.71* | 1.2, 6.11 |

| 40–44 | 253 (13) | 4.8*** | 1.89, 12.03 |

| 45–49 | 246 (13) | 5.2** | 1.88, 14.65 |

| 50–54 | 265 (14) | 6.9** | 2.14, 22.39 |

| 55–59 | 207 (11) | 7.5** | 2.07, 27.23 |

| 60–64 | 54 (3) | 4.8* | 1.2, 19.14 |

| 65 and older | 15 (1) | 3.8 | 0.7, 20.46 |

| Role | |||

| Doctor in training | 666 (35) | 1 | Ref. |

| Consultant/GP | 1030 (54) | 1.1 | 0.74, 1.7 |

| SAS/locum | 219 (11) | 1.0 | 0.64, 1.65 |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 1626 (85) | 1 | Ref. |

| Contracted | 152 (8) | 0.62* | 0.43, 0.89 |

| Unemployed | 12 (1) | 0.5 | 0.14, 1.79 |

| Employed, but sick | 15 (1) | 3.8* | 1.16, 12.24 |

| Other | 110 (6) | 1.17 | 0.76, 1.79 |

| Years since qualifying | |||

| 0–10 | 657 (34) | 1 | Ref. |

| 11–25 | 733 (38) | 0.86 | 0.51, 1.45 |

| 26+ | 525 (27) | 1.2 | 0.54, 2.4 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 1660 (87) | 1 | Ref. |

| Asian | 138 (7) | 0.7 | 0.49, 1.09 |

| Black | 21 (1) | 0.2** | 0.08, 0.7 |

| Mixed | 38 (2) | 0.5 | 0.24, 1.04 |

| Chinese | 11 (1) | 1.3 | 0.34, 4.64 |

| Other | 47 (2) | 0.6 | 0.31, 1.08 |

| Received mental health information | |||

| Yes | 763 (40) | 1 | Ref. |

| No | 1152 (60) | 1.0 | 1.0, 1.02 |

| Experienced symptoms of mental ill health | |||

| Yes | 1142 (60) | 1 | Ref. |

| No | 773 (40) | 5.3*** | 4.22, 6.63 |

| Constant | 0.2*** | 0.11, 0.53 | |

| Intraclass correlation | 0.02 | 0.003, 0.08 | |

| N | 1915 | ||

SAS, staff and associate speciality.

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

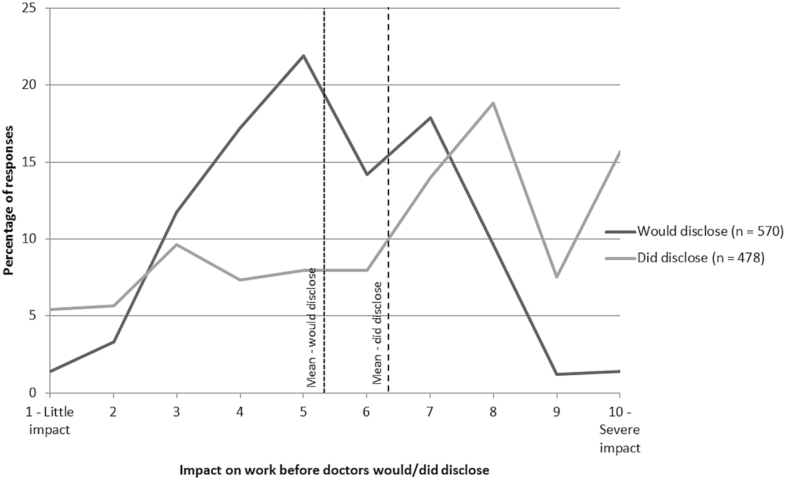

Doctors were asked how much of an impact their mental ill health would have on their work before they would disclose or did disclose. This was measured using a Likert Scale where a score of 1 was little impact and 10 was severe impact.

Those who answered the question hypothetically said they would disclose mental ill health when their symptoms were having less impact on their work (mean = 5.35) than doctors who had personally experienced mental ill health and disclosed it at work (mean = 6.36). The differences between these two groups are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Impact on work before doctors would/did disclose (n = 1048).

For doctors who had had mental ill health, the results suggested that willingness to disclose was also dependent on when symptoms first developed. Trainees were the least likely to disclose symptoms, while consultants were the most likely. A chi-squared test showed the association between level of training at the time symptoms developed and willingness to disclose to be significant (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Timing of first symptoms of mental ill health and disclosure of those symptoms to the workplace (n = 1167, those who have experienced mental ill health)

| Whether participants disclosed at work when first experiencing mental ill health, N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| When did you first experience symptoms of mental ill health? | ||

| Before medical school | 89 (42) | 123 (58) |

| At medical school | 119 (38) | 191 (62) |

| As a trainee doctor | 114 (34) | 219 (66) |

| As a consultant doctor | 156 (50) | 156 (50) |

| Total | 478 (41) | 689 (59) |

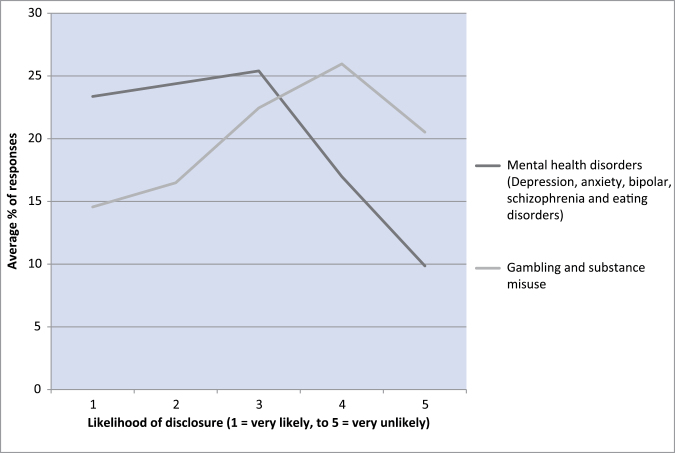

Doctors without a history of mental ill health were asked to think hypothetically about how likely they would be to disclose different types of mental ill health at work and rate this using a Likert scale. The results suggested that doctors were less likely to disclose substance misuse and gambling addictions than depression, anxiety, eating disorders, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. This is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Responses to the question ‘How likely would you be to disclose the following types of mental ill health to your workplace?’ by those respondents with no history of mental ill health (n = 570).

Doctors without a history of mental ill health were asked why they would disclose and those who had experienced mental ill health were asked why they did disclose at work. The trends in responses were the same for both subgroups with ‘professional responsibility’, ‘for advice on how to manage work alongside mental ill health’ and ‘for emotional support’ as the three main reasons (Table 4) for disclosure.

Table 4.

Main reasons for disclosing

| Reasons for disclosure | No previous mental ill health % (n = 570) | Previous or current mental ill health % (n = 478) |

|---|---|---|

| To obtain treatment | 15 | 28 |

| For emotional support | 39 | 38 |

| For advice on how to manage work/studies alongside mental ill health | 66 | 41 |

| Professional responsibility | 85 | 52 |

| To understand any career implications | 19 | 12 |

| Other | 4 | 19 |

In one area, the trend was reversed. Those doctors with a history of mental ill health placed more import ance on the reason ‘to obtain treatment’ than those without such a history. Doctors were given the opportunity to offer free text responses giving the reasons for disclosure. Responses included ‘to take time off on sick leave’ and ‘to negotiate reduction in or changes to workload’.

When doctors were asked why they would not/did not disclose, the most frequent responses were the same in both subgroups with ‘not wanting to be labelled’ as the most cited reason. However, 25% of those with a history of mental ill health used the ‘free text’ section to provide more detailed responses. The main reasons recorded in this section included ‘mild symptoms’, ‘lack of insight’, ‘didn’t see relevance’ and ‘able to deal with it alone’.

Differences in reasons not to disclose were evident between the two subgroups. Twenty-five per cent of doctors without a history of mental ill health would not disclose as they were ‘concerned about involvement of the GMC compared to only 9% of those who had experienced mental ill health’. Nineteen per cent of doctors with a history of mental ill health cited ‘feeling that I was letting colleagues down’ as a reason for not disclosing, compared to 38% of doctors without a history of mental ill health.

Doctors without a history of mental ill health were asked to imagine whom they would disclose to first. Ninety-seven per cent stated that they would confide in someone outside the workplace first, with their spouse or partner chosen by the majority (73%). When asked about whom in the workplace they would confide in the most common answer was a ‘colleague’ (30%), followed by ‘a friend who is a healthcare professional’ (17%) and ‘line manager’ (14%).

Doctors who had personal experience of mental ill health were also asked who they had disclosed to in the workplace. Here, occupational health (38%), colleagues (37%) and line managers (31%) were most commonly cited. Free text comments suggested that the decision about who to disclose to may not be through choice but the procedures required by human resources and the organization with respect to sickness absence management. For example, ‘Obliged to disclose in pre-employment screening’, ‘Didn’t have a choice’ and ‘Had to go through OH to get back to work’.

In terms of the attributes that doctors looked for in somebody to disclose to at work, the trends were the same in both groups with a few exceptions. For doctors with a history of mental ill health, ‘If they were a senior member of staff’ was much more important to them than for doctors without a history of mental ill health. Free text responses given by those with a history of mental ill health cited factors including professional responsibility, to manage their health, manage their workload, or again because they had been advised to or had ‘no choice’.

Discussion

This study highlighted a discrepancy in how doctors thought they might behave if they were to become unwell, compared to how they reported actually behaving when they experienced mental ill health, regardless of role. Importantly, trainees and younger doctors were less likely to disclose. Doctors who had reported experience of mental ill health seemed to disclose later than when the question was posed hypothetically to those who had not experienced mental ill health. This suggests that there are significant obstacles that may only be recognized once a doctor becomes unwell.

Not wanting to be labelled and not understanding the support structures available were identified as key obs tacles to disclosure. Doctors felt they had ‘no option’ in terms of pathways for accessing support. This was highlighted in responses about whom doctors would first approach at work. For those without a history of mental ill health, only 6% stated they would go to occupational health first and no trainee would choose to go to their deanery support unit, although these are the recognized pathways for support within the NHS and deanery systems.

A key strength of the study was that we targeted doctors both with and without a history of mental ill health. This provided us with data that to date had not been captured in other studies. Using an online anonymous survey allowed for nationwide distribution, and multiple modes of dissemination meaning, we were able to target a diverse population. To understand the perspective of both doctors with and without a history of mental ill health, comparable questions were asked of each group. This proved invaluable in highlighting discrepancies in reported and likely behaviour.

The study yielded responses from ~1% (1946) of the UK doctor population and included doctors of different specialities and grades. It provided insight into how doctors with and without symptoms may differ in behaviours for mental ill health. We recognize however that this is a small sample and may not be truly representative of the UK doctor population and may be biased due to self-selection. The question on perceived impact of symptoms on work was subjective. Objective measures may have provided quite a different rating. With respect to the likelihood of disclosing various types of mental ill health, we recognize that the results may be skewed as we only asked about a few well-recognized conditions.

The sample from England had a higher proportion of doctors with mental ill health, which may be due to the main method of dissemination in England, through the Physician Health Programme (PHP) which supports doctors with mental ill health. This obviously may bias our data. The four questionnaire pathways meant that the numbers in each subsection were too small to carry out multivariate regression to assess the influence of individual factors and their interactions, so only univariate associations were tested. The results of this survey must therefore be interpreted with caution.

In comparison to wider literature, our finding that 97% of doctors would confide first in someone outside the workplace supports earlier findings [6], where 73% of doctors would choose to disclose a mental illness to family and friends rather than to a professional. In the same study, consultants were found to be more likely than any other group to cite ‘professional integrity’ as a factor influencing their decision to disclose. In response to our similar question, the findings are replicated, with a higher proportion of consultants (30%) citing ‘professional responsibility’ as a main reason for disclosing at work compared with other types of doctor (10–23%).

In conclusion, asking what people may do gives an indication of individual attitudes to mental ill health and stigma, and potentially to the workplace culture. Organizational culture significantly affects stigma. This study has highlighted that some doctors would never disclose mental ill health in their workplace and many do not understand how they may seek support. Results suggest that dissemination of information about pathways to support, and clarifying how support services function and their boundaries in respect of confidentiality, could help shape future services. Doctors learn maladaptive coping behaviours early on in their medical careers and there is a clear benefit in reviewing support at medical schools [15] if we are to avoid such stress and distress in the future.

Key points

In this study, trainees and younger doctors were less likely to disclose mental ill health than general practitioners and consultants.

Not understanding the support structures available was a key obstacle to disclosure.

In reality, doctors were likely to disclose mental ill health later than they thought they would.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1. The Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry. London: The Stationery Office, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Andrews J, Butler M. Trusted to Care: An Independent Review of the Princess of Wales Hospital and Neath Port Talbot Hospital at Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Board. Cardiff, UK: Welsh Government, 2014. http://gov.wales/topics/health/publications/health/reports/care/?lang=en. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Department of Health. Mental Health and Ill Health in Doctors. London, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hawton K, Clements A, Sakarovitch C, Simkin S, Deeks JJ. Suicide in doctors: a study of risk according to gender, seniority and specialty in medical practitioners in England and Wales, 1979–1995. J Epidemiol Community Health 2001;55:296–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Henderson M, Brooks SK, del Busso L, et al. Shame! Self-stigmatisation as an obstacle to sick doctors return to work: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hassan TM, Ahmed SO, White AC, Galbraith N. A postal survey of doctors’ attitudes to becoming mentally ill. Clin Med (Lond) 2009;9:327–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brooks SK, Chalder T, Gerada C. Doctors vulnerable to psychological distress and addictions: treatment from the Practitioner Health Programme. J Ment Health 2011;20:157–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Working Group on the Misuse of Alcohol and Other Drugs by Doctors. The Misuse of Alcohol and Other Drugs by Doctors. London: British Medical Association, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oliver MI, Pearson N, Coe N, Gunnell D. Help-seeking behaviour in men and women with common mental health problems: cross-sectional study. Br J Psychiatry 2005;186:297–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Adams EF, Lee AJ, Pritchard CW, White RJ. What stops us from healing the healers: a survey of help-seeking behaviour, stigmatisation and depression within the medical profession. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2010;56:359–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Garelick AI. Doctors’ health: stigma and the professional discomfort in seeking help. Psychiatr Bull 2012;36:81–84. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brooks S, Gerada C, Chalder T. Review of literature on the mental health of doctors: are specialist services needed? J Ment Health 2011;1:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Department of Health. Invisible Patients: Report of the Working Group on the Health of Health Professionals. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Feeney S, O’Brien K, O’Keeffe N, Iomaire ANC, Kelly M. Health behaviours and response to stress among non-consultant hospital doctors – barriers and solutions. In: International Conference on Physician Health, BMA, London, 2014 .

- 15. General Medical Council. Supporting Medical Students With Mental Health Conditions. 2013. [Google Scholar]