Abstract

Research has demonstrated the clinical effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention, but little is known about how factors at the individual-, interpersonal-, community-, and structural levels impact PrEP use for black men who have sex with men (BMSM). We advance existing work by examining how all levels of the ecological framework must be addressed for PrEP to be successfully implemented as an effective HIV prevention approach. We interviewed 31 BMSM three times each and 17 community stakeholders once each; interviews were taped, transcribed, and analyzed using the constant comparative method. Factors that influence how BMSM experienced PrEP emerged across all levels of the ecological framework: At the individual level, respondents were wary of giving medication to healthy people and of the potential side-effects. At the interpersonal level, BMSM believed that PrEP use would discourage condom use and that PrEP should only be one option for HIV prevention, not the main option. At the community level, men described not trusting the pharmaceutical industry and described PrEP as an option for others, not for themselves. At the structural level, BMSM talked about HIV and sexuality-related stigmas and how they must overcome those before PrEP engagement. BMSM are a key population in the US National HIV/AIDS Strategy, yet few individuals believe that PrEP would be personally helpful. Our research indicates the urgent need to raise awareness and address structural stigma and policies that could be substantial barriers to the scale-up and implementation of PrEP-related services.

Introduction

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), which uses antiretroviral medications to prevent HIV acquisition among HIV-negative individuals, was effective in a multi-national study among 3000 men who have sex with men (MSM).1 The iPrEx study found a 44% reduction in HIV infections among men taking oral PrEP compared with a psychosocial prevention package, and a >90% efficacy among individuals with detectable drug levels.2 Demonstration projects across the United States3,4 have supported these results. The USFood and Drug Administration approved Truvada as an oral PrEP treatment for MSM in 2012.5

PrEP could help reduce HIV incidence among MSM,6 who account for approximately two-thirds of new HIV infections in the United States.7 Black MSM (BMSM) have the highest HIV incidence rates in the United States; reduction of such disparities is a vital part of the US National HIV/AIDS strategy. Though HIV disparities are stark for BMSM, PrEP has not been embraced in the way public health officials had hoped, even in resource-rich settings such as New York City (NYC). By spring of 2014, only 41% of MSM in NYC had heard of PrEP and only 3% had ever used PrEP.8

The ecological framework and PrEP use

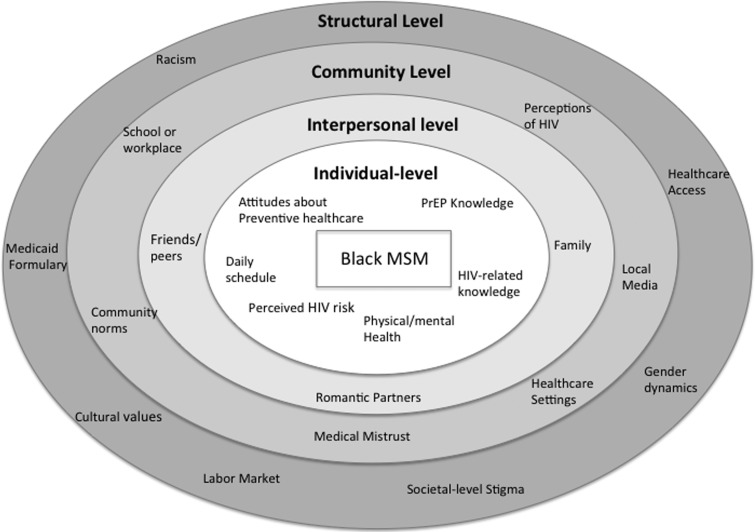

The CDC and its partners are pursuing a “high-impact prevention” approach to reduce HIV infections.9 Given the broad range of social (e.g., housing, employment, racism) and interpersonal factors that impact HIV vulnerability for BMSM, we applied the ecological model to frame our analytic approach of factors that shape MSM's engagement with PrEP. The majority of PrEP research has addressed the individual level, but HIV prevention research suggests that acknowledging all levels of Bronfenbrenner's (1979) ecological systems will be imperative for the successful implementation of PrEP. These levels include the: (1) individual (attitudes, knowledge); (2) interpersonal (friends, partners); (3) community (medical mistrust, healthcare settings); (4) and structural levels (stigma, healthcare policies). Each level uniquely contributes to how individuals engage with HIV prevention measures and come to understand PrEP (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Ecological model of factors that impact pre-exposure prophylaxis attitudes and uptake among black MSM.

PrEP research on individual-level factors has found a range of PrEP-related knowledge and acceptability.10,11 Men often lacked a comprehensive understanding of PrEP, though men aware of PrEP were also at the greatest risk of infection (e.g., due to having sex while high12). The intent to use PrEP has also been associated with no perceived side-effects.13 Researchers exploring interpersonal-level factors have cautioned that PrEP may lower perceived risk and increase condomless sex,14 though results are mixed.12 A recent study described the importance of community-level factors, finding that BMSM's interest in PrEP was contingent on cost, accessibility, and healthcare access,15 particularly since many lacked health insurance.16,17 Little research has examined medical mistrust and PrEP uptake, though one survey identified discomfort talking to physicians about sleeping with men and race-based medical mistrust as barriers to PrEP use.18 Structural-level stigma has been associated with HIV risk and acquisition, as well as with lower adherence; studies have also demonstrated that lower PrEP-related stigma19 and structural stigma20 are associated with PrEP acceptability and use.21

Purpose

Existing research into PrEP uptake has focused almost exclusively on the individual level of the ecological model. Here, we advance existing work by examining how all levels of the ecological framework must be addressed for PrEP to be successfully implemented as an effective HIV prevention approach.

Methods

This study (June 2013–May 2014) included three in-depth interviews each with 31 BMSM (average, 90 min) in NYC who were at least 15 years of age, male, and reported sex with a man in the past year. Men were recruited through outreach in bars, clubs, community health centers, and the Internet, with the goal of diversity related to sexual identity, age, insurance coverage, and income, though lower SES men were overrepresented in the final sample (Table 1). Interview topics included family, education and work history, sexual history, sexual and racial identity, healthcare seeking, and knowledge and attitudes toward HIV prevention and PrEP. Men received a total of $150 for participation ($40 for the first two interviews and $70 for the third). We also conducted 17 semi-structured interviews (average, 60 min) with community stakeholders (e.g., outreach workers, community mobilizers, healthcare professionals) who were involved in HIV prevention and/or BMSM health. They were asked about institutions and support available to BMSM and knowledge and attitudes about BMSM and HIV prevention. Stakeholders were compensated $50.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Black MSM

| Characteristic | Total, N = 31 |

|---|---|

| Age | 29 (average) |

| 15–24 | 17 |

| 25+ | 14 |

| Sexual identity | |

| Gay | 15 |

| Same-gender loving | 3 |

| Bisexual | 4 |

| Discreet | 4 |

| Straight | 3 |

| Other (MSM, none) | 2 |

| HIV test past 6 months | |

| Yes | 23 |

| No | 2 |

| N/A (already positive) | 6 |

| Medical exam past 12 months | |

| Yes | 22 |

| No | 9 |

| Prior knowledge of PrEP | |

| Yes | 15 |

| No | 15 |

| HIV status (self-report) | |

| Negative | 23 |

| Positive | 5 |

| Undisclosed | 3 |

| Housing | |

| Stable | 15 |

| Precarious | 11 |

| Homeless | 5 |

| Employment | |

| Full time | 8 |

| Part time | 8 |

| Unemployed | 15 |

| Insurance status | |

| Private | 5 |

| Public | 17 |

| Uninsured | 9 |

PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis.

All participants provided verbal informed consent: Their understanding was assessed by a series of follow-up questions; data analysis began after verbal consent. The Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved all aspects of this study.

Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Interview data were analyzed and triangulated between and across cases using Atlas.ti 7.0 qualitative software. These analyses employed a codebook that was developed based on domains (code families) derived from the interview guides and line-by-line coding. The analysis for this article used the constant comparative method22 to explore the varied ways that men talk about PrEP, seem willing to engage with PrEP, and understand PrEP. Descriptions of PrEP did not vary significantly between BMSM and community stakeholders; their responses are, therefore, combined in this article.

Results

Participants' average age was 29, and most were unemployed or unstably housed. More than half had Medicaid or were uninsured and were identified as gay or same-gender loving (Table 1). Approximately three-quarters of the men attended community clinics, though primarily for HIV testing and not routine check-ups. The majority of participants had never heard of PrEP, despite PrEP's availability in multiple clinics and inclusion in the state Medicaid formulary. We use the ecological framework to organize our presentation of the numerous factors men described that both supported and challenged their desire for, and ability to take, PrEP. Additional quotes are included in Table 2.

Table 2.

Participants' Statements Regarding the Acceptability and Adoption of PrEP

| Ecological level | Theme | Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Individual | Beliefs about PrEP effectiveness | “I wouldn't take that choice. No, 90% [effective], no. I don't like odds. I like 100 to 0. Cause 100%, then again, but 90 to 10, my luck is very, very bad so I'd be 1 out of the 10. No, I wouldn't take that chance.” (BMSM) |

| Fears of side-effects and giving medication to healthy people | “It depends on the side effects. If I'm going to take something I want to make sure because my own behavior can help me from contracting HIV … I wanna make sure that the side effects ain't going to be worse than death–well it's not death because many people are living with it.” (BMSM) | |

| “Pills over a period of time can become toxic in your system…People just don't like popping pills. I still have a difficult time taking a pill. Because it's like you're putting something in your body, and once you put it in there, you don't have any control anymore.” (BMSM) | ||

| Interpersonal | Risk disinhibition and STI risks | “It's basically just telling people that it's okay for them to go out there and have random sex, unprotected sex with anybody who they want. Why you going to give them something pre [sex], they need something for now, because they don't know who they have slept with and who that person has had or what that person got.” (Community Stakeholder) |

| “I believe it's a good option to have, like I said it kinda just still loses the STI piece of it.” (BMSM) | ||

| “The only thing that's running through people's minds is that Oh my God, I can take a pill, and If I do this right, I'm not gonna catch HIV. They're gonna not be thinking about, Oh, but I could still get Gonorrhea or syphilis or something. They just, the whole thing is I'm not gonna get HIV.” “So you're telling me that those are not important anymore. So I don't think so. Syphilis is still a bad thing.” (BMSM) | ||

| “If you have an untreated STD then your probability of infection just goes sky high so I think the messages of continuing to make sure you're STD free and things of that nature are important and that it's [PrEP] not for everyone.” (Community Stakeholder) | ||

| No single solution | “So I think the messaging needs to be very clear to this group that it's not the end all be all with one pill, that there's still a small chance that if the condom breaks or you don't use condoms that you could become infected. That it's important to take it in collaboration with condoms, continue to promote the importance of condoms and also promote the importance of screenings for STDs and make sure that you're STD free if you're gonna start using PrEP because even if you—you know you use PrEP and the condom breaks, you know, there is the possibility you can get infected.” (Community Stakeholder) | |

| “So I think the messaging needs to be very clear to this group that it's not the end all be all with one pill, that there's still a small chance that if the condom breaks or you don't use condoms that you could become infected. That it's important to take it in collaboration with condoms, continue to promote the importance of condoms and also promote the importance of screenings for STDs and make sure that you're STD free if you're gonna start using PrEP because even if you–you know you use PrEP and the condom breaks, you know, there is the possibility you can get infected.” (Community Stakeholder) | ||

| Community | Medical mistrust | “The government is trying to make money off us because there's money in medicine. The government is trying to get us to just pop a pill and just be done with it or whatever.” (BMSM) |

| “What I would hear from clients is they're not as confident navigating with their medical providers, generally, and also confidential(ity). A lot of them say, ‘Well, who's gonna have access to that information?’ They have a point. They're like, ‘Well, will the government see this?’” (Community Stakeholder) | ||

| “We just ain't gonna believe it ‘cause a lot of us think that's just some shit people are trying to sell to use us as guinea pigs.” (BMSM) | ||

| Who needs PrEP? | “I don't think that people are scared of catching HIV no more because they go out there and they go crazy and have unprotected sex. And then when they catch it now, at first they're worried. And they lay it down. They feel good because they have this reassurance that this pill will take them a long way. So I think this is what now invites them. It ain't a death sentence. I just take some pills. I live a normal life.” (Community Stakeholder) | |

| “Tops are less likely to get it anyway, they can still get it, obviously, but they're less likely to get it than bottoms…I'm sure a lot of other people will have that same mindset.” (BMSM) | ||

| “Getting promiscuous people. Teenagers. They fuck everything like there's no tomorrow. As adults now, we don't just go and fuck anyone…Maybe the condom's not available when you're fucking. Maybe one breaks and you only have one. A lot of things happen.” (BMSM) | ||

| “But since I know how unsexually active I am, it's just something I feel would become tedious after a while or become tedious if I'm just taking it and I'm not doing anything. That might lead me to not take it.” (BMSM) | ||

| Structural | Stigma and PrEP | “If somebody knew I was asking about that pill…then there is a stigma that goes along with that. And I think that people will obviously look at you differently, even black men. If they thought that you was HIV-positive, they usually associate that with being gay, and then they would look at you differently for being gay. That's still in the black community.” (BMSM) |

| “That's predicated on someone actually showing up to the clinic, meaning they've crossed all the barriers of access and perceived homophobia and perceived racism and perceived cost issues or whatever goes into access. And then they've met a provider who they feel comfortable with enough to discuss these things and the provider is knowledgeable and willing to engage that young person in these issues.” (Community Stakeholder) | ||

| Structural barriers to PrEP use | “Like, I just—I—I'm a very—I try to be a very structure person, even though sometimes that leads to my demise ‘cause I always feel like I have to get one thing first, and then it will lead to the next. So my focus is work. Like, I need to find work. Like, I need a job. And then with a job, then I could look into the resources on how to get some type of health coverage. ‘Cause then at that point, I won't feel like I'm just a part of the system. I feel like I just need assistance.” (BMSM) | |

| “I had no money and to be honest with you, around that time I was kind of the breadwinner in the house. Nobody else really—my mother didn't have a job. My grandmother was too old to work and then besides that, she was too busy taking care of my mother's kids to go out and work so I was always the one who would go out and get money and stuff like that, even though I know that my grandmother used to ask me, ‘Where did you get this money from?’ It's like, ‘Where do you get these clothes from?’ and stuff like that. But I'd always lie to her, ‘Oh doing this and doing that.’ I would tell her—I told her one time, because I used to tell her like one time this club, they would pay me to sing. I would tell her like that—stuff like that. I would tell I was waitressing or something like that.” (BMSM) |

Individual level

In addition to PrEP-related challenges reported elsewhere (e.g., daily adherence and cost),12 major individual-level barriers to PrEP engagement were confusion about effectiveness and concerns about potential side-effects.

Beliefs about PrEP effectiveness

Many men expressed confusion over the meaning of a 90% effective pill, and whether the effectiveness referred to risk per sex act or meant that some people were more protected than others. Men grappled with whether 90% effectiveness was sufficient to offset additional risks, and with what 90% effective actually means (e.g., being “1 out of the 10” as opposed to transmission risk per sex act). As one man noted: “It was 90% chance that it's preventative. I'm like, 10% is still pretty big. You know, even 1%—somebody has to make up the 1%, so it still happens” (22, gay).

Fears of side-effects and providing medication to healthy people

The majority of men questioned whether PrEP's efficacy was sufficient to counteract the potential side-effects, which some participants used as a rationale for eschewing PrEP: “It reduces your bone density and how do you correct that? There's really nothing you can do once your bone mass is lost. So taking that pill, it's basically damaging you” (20, discreet). This was described as particularly true since other HIV prevention methods lack side-effects. Some men were adamant that healthy people should not put drugs in their bodies, especially if they already struggled with adherence to medications for existing conditions (e.g., diabetes or asthma). One man shared how “doctors and clinics don't want to voluntarily give medicine to healthy people…‘cause they're healthy people and you're just like, you're voluntarily giving them a drug regimen’” (22, gay).

Interpersonal level

Interactions with friends, family members, and sexual partners also influenced the desire for PrEP. Principle concerns expressed by participants included risk disinhibition and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and how PrEP fit into a range of prevention options.

Risk disinhibition and STI risks

Some men expressed concern that PrEP use would decrease condom use among their partners and sexual networks. Men saw condoms primarily as an HIV prevention tool and thus something that would be used in lieu of, not in combination with, PrEP. Responses depicted how behaviors might shift with PrEP use: “You're going to give me a pill and tell me that with this pill I cannot catch HIV, which means that it's going to make people feel as if it's okay for me to go out and have unprotected sex…Why would you want to do that?” (24, gay). Some men repeated that PrEP would not project against other STIs, and that condoms should still be used. One community stakeholder saw this tension as particularly dangerous: “I think it actually does more harm because it leaves us open for other diseases. The condom is the reason for syphilis and gonorrhea and other things that are sexually transmitted.”

No single solution

Most men described PrEP as simply one more option for HIV prevention, and they suggested the importance of maintaining as many means of prevention as possible. One community stakeholder suggested that PrEP messaging focus on integrating PrEP and condoms, “I think the messaging needs to be very clear that…it's important to continue to promote the importance of condoms and screenings for STDs and make sure that you're STD free if you're gonna start using PrEP.” Another individual noted that, due to the diversity of BMSM, PrEP should be framed as part of a toolkit, not the only option: “I feel like we need a whole lot of different options when it comes to prevention—the community is so diverse…condoms is one thing. Being abstinent is one thing. Being tested and being with only one partner is one thing but it's important to have pills also to help you stay negative and also therapy. I feel like all that is important” (29, gay).

Community level

Community-level themes include medical mistrust and the framing of social risk, specifically viewing PrEP as something that only other people need.

Medical mistrust

Mistrust of both the pharmaceutical industry and healthcare providers was widespread. Some men explicitly referred to historical abuses by pharmaceuticals and research (e.g., Tuskegee Syphilis Study), and how they profit from BMSM: “You would have a hard time selling that [even with] 99.9 percent efficacy coming from pharmaceutical companies…particular to people of color.” Some of the younger men were less vocal, but they still harbored skepticism. One participant noted that, although the pill might work, he still wanted to wait: “I'm not gonna start taking it off the bat, give it a couple more years, see what studies are done, and the information about it” (19, bisexual).

Who needs PrEP?

Men frequently discussed the concept that social researchers would define as “social risk,” and how HIV-related stigma challenged their willingness to accept their own actions as potentially risky. The majority of men described their behaviors as “normal,” or even declined to discuss them at all, and thus did not feel the need to take a daily pill to prevent HIV. When men were asked who should take PrEP, responses focused on the type and amount of sex that people were having, and often involved words such as “slutty,” “promiscuous,” or sexual positioning (i.e., bottoms versus tops). One man felt that PrEP users should be “people who have lived the lifestyle of just hooking up or being out there, just being free…If you're out there and just living life and meeting guy after guy after guy” (18, gay). Men consistently talked about PrEP as something that would be useful for others, but not for themselves. One participate summed it up explicitly, “I think it is good for the whole world, it's good for the community, so yeah, it's gonna work, it just ain't gonna work for me… I don't want to know about the pill because I don't care about the pill. I ain't never fucking taking the pill” (45, straight).

Structural level

The structural level includes social institutions, cultural dimensions, economic organizations, and political structures that affect society as a whole. The high levels of stigma (a social and cultural structure) attached to HIV/AIDS, sexuality, race, and gender performance shaped BMSM's everyday lives and attitudes toward PrEP. The interviewees also described how economic factors such as housing instability and the labor market would impact their ability to take PrEP.

Stigma and PrEP

Most men described how PrEP use could result in HIV stigma, and they feared that friends, family, or sexual partners might see a PrEP bottle and assume they were HIV positive. This would require people to take the pill in secret, which complicates adherence: “People don't like taking any medicine in front of people. Maybe they feel like a stigma would develop from what you are taking? People be nosy, like what's that you taking?”(27, same-gender loving). A few men also described how internalized stigma could impact PrEP uptake. Asking for PrEP would force a man to accept that he was having sex with other men, often without a condom, and was thus at risk for HIV. As one community stakeholder described, “You've got to accept within yourself that you love and enjoy sex with a man every single day, and you may like it raw 90 percent of the time. But then that's like accepting, ‘Oh, I'm going to get HIV. Oh, I'm just another fag.’”

Structural barriers to PrEP use

Even men who expressed interest in taking PrEP reported structural barriers that reflected intersecting inequalities of race, sexuality, and socioeconomic status. Nearly all BMSM reported unstable housing, often as a result of their sexuality (e.g., being kicked out of their home for having sex with men), which complicated daily pill taking: “You gotta find a place to take medicine cause they don't want everybody in their business. From what I hear, everybody's nosy in the shelter, everybody's in your business” (27, same-gender loving). Men also described how fluctuations in daily routines—due to factors such as housing and job instability—would complicate maintaining what was already a strict daily regimen.

Discussion

This ethnographic study explored how BMSM think about, understand, and engage with PrEP. Even men who had heard of PrEP reported an incomplete understanding of PrEP's efficacy, the potential side-effects, and the frequency of use. Also, the view that PrEP was a useful tool for others, but not for oneself, cut across, and was informed by, all aspects of men's lives (e.g., their personal attitudes, relationships, community norms, and structural stigma).

Personal level

Similar to previous research examining facilitators and barriers to PrEP use,15,23–26 two primary factors influenced study participants' PrEP desires: perceived efficacy and side-effects.25 Concerns about effectiveness suggest that men see PrEP as a standalone prevention method rather than as something to pair with condoms. A PrEP messaging study found uncertainty among men about how to interpret numerical estimates and whether clinical trial results would predict personal effectiveness;27 men in this study expressed confusion about what 90% effectiveness meant for their own HIV risk. Study participants also felt conflicted about healthy people taking medication, especially one with side-effects. Particularly since other means of HIV prevention lack side-effects, men reported wariness about whether the benefits outweighed the risks. This echoes other research with HIV-negative MSM, which found potential side-effects (particularly long-term ones) to be the biggest barrier to uptake.28–30 Moreover, potentially reflecting how medical mistrust might amplify concerns about side-effects, MSM of color were more likely than white MSM to state that they would avoid PrEP because of side-effects.31 Men were also loathe to put something in their bodies that could not be taken out again; this suggests that injectable PrEP, which has been discussed as a way of solving PrEP's adherence challenges, may also create new barriers to uptake.

Interpersonal level

Respondents worried about declines in condom use for men on PrEP and those having sex with men on PrEP. Participants emphasized that the PrEP uptake would allow them to avoid condoms and that regular condom use would eliminate the need for PrEP; the few respondents who described joint PrEP and condom use as realistic were community stakeholders. Previous studies reported mixed sentiments about risk disinhibition; 4 of 10 studies in a review12 reported that risk disinhibition would occur,24,25,32,33 whereas 6 did not.15,34–38 A study of MSM in serodiscordant relationships showed that the use of PrEP might reduce condom use and increase risk behaviors, and it found that desire for condomless sex was a major reason to take PrEP.34 Other studies showed that men would forgo condoms if PrEP had an efficacy of more than 50%.12 Men within this study had conflicting narratives about PrEP and condom use. Men described how risk disinhibition among partners and sexual networks would increase their risk for HIV, particularly since PrEP is neither 100% effective, nor does it protect against other STIs. However, others, particularly community stakeholders, felt that PrEP's lack of STI protection should be highlighted as a rationale for continued condom use.

Community level

Two primary factors impacted whether men would seek PrEP: medical mistrust and the framing of social risk (i.e., believing that only others should take PrEP). Although research has examined the intersection of medical mistrust, healthcare seeking, and race, little work exists about how mistrust of the pharmaceutical industry (i.e., of biomedicine writ large) might limit PrEP uptake. Medical mistrust research primarily focuses on patient–provider relationships, with one study finding race-based medical mistrust as a barrier to PrEP use;18 another reported that “medical mistrust and perceived discrimination create barriers for sexual behavior disclosure to clinicians,” which study authors believed could impede PrEP access.39

The men saw PrEP messaging as confusing, because although BMSM were targeted by many campaigns, they did not see themselves as at risk and in need of PrEP. Other studies report such confusion and showed that perceived HIV risk was associated with PrEP uptake.40 Willingness to use PrEP is associated with a higher perceived risk of HIV acquisition,37,41 which supports why the men we spoke with who did not see themselves as at risk felt that PrEP was something that only other people should engage with. This suggests that communications strategies must help men imagine themselves as PrEP users, in addition to presenting technical dimensions of PrEP, such as its effectiveness. This social framing of risk also suggests the need to examine the stigma associated with HIV and sex between men. Addressing risk denial through stigma reduction may help counteract how some men actively resist seeing their behaviors as making them vulnerable to HIV and thus in need of PrEP.

Structural level

The men we spoke with reported that PrEP use might also cause stigma from friends, family, and partners. PrEP uptake involved substantial social risk, including revelations about having sex with men, which many men chose to not disclose to their families and friends. The few studies that have addressed the intersection of PrEP and stigma focused almost exclusively on interpersonal-level factors (e.g., relationships) and reported that men see PrEP use as a marker of infidelity30 and fear disclosure of PrEP use, in part due to HIV-related stigma.42,43 In contrast, the men in this research described stigma on a structural level and focused on how it constrained their ability to accept themselves as BMSM with other men, and to thus recognize the need to engage in HIV prevention.

Structural barriers to PrEP use—felt acutely in a sample in which the majority of men lacked both health insurance and a primary care provider—included unstable housing and lack of access to medical care and HIV prevention services. The iPrEx trial showed that PrEP's effectiveness varies according to adherence, suggesting that PrEP's success at both the individual and population level will depend on ensuring BMSM's access to HIV prevention services (e.g., condoms, STI treatment, HIV testing, and counseling) and primary care1—which are not always available at either low or no cost to BMSM. In addition, the majority of study participants lacked access to a social worker or case manager who could facilitate access to the housing and employment that would provide the stability necessary to begin taking PrEP or to the medical services in which men might actually receive PrEP. Strategies focused on enrolling BMSM in primary care, for example, by using Affordable Care Act health navigators, could also help lay the groundwork for increased PrEP uptake. Lastly, we must ensure that Medicaid formularies across the United States cover PrEP-related care and treatment.

Limitations

Although participants varied by age, sexual identity, and insurance status, they were primarily low SES. Also, New York is unique in terms of available HIV-related services. However, this suggests that the barriers to PrEP would only be more substantial across the United States, since many other states have either not added PrEP to their Medicaid formularies or have less generous funding for Medicaid or fewer BMSM-oriented prevention programs. Though we described PrEP in the interview guide, and answered any resulting questions, participants did not have an extended period to think through all of PrEP's benefits and limitations, which may have limited their capacity to comment.

In conclusion, findings demonstrate that PrEP will only become a successful intervention if all levels of the ecological framework are addressed. Specifically, our findings show that PrEP-related communications strategies should be as detailed as possible about efficacy and explicitly address tensions between PrEP and condom use. Community- and structural-level factors such as medical mistrust and societal stigma can impact PrEP use; potential intervention approaches could include a rights-based, anti-homophobia, approach to mitigate HIV-related stigma as well as community engagement around HIV prevention. To realize the promise of PrEP, future research needs to examine how biomedical prevention can be integrated into the lives of BMSM across all levels of the ecological framework.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH098723, PIs: Paul Colson and J.S.H.). Additional support came from the Center for the Study of Culture, Politics and Health and the Society, Psychology, and Health Research Lab (SPHERE). Dr. M.M.P. is supported by an NIMH training grant (T32-MH19139 Behavioral Sciences Research in HIV Infection; PI: Theodorus G.M. Sandfort, PhD) located within The HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies (P30-MH43520; PI: Robert Remien, PhD). The principal contributions of each of the authors of this article are as follows: M.M.P. as primary author led the study analysis and interpretation of the data and contributed significantly to the drafting and revision of the article; C.M.P. contributed significantly to the analysis and interpretation of the data and revisions of the article; R.G.P. and P.A.W. contributed to the study design and revision of the article; J.G. conducted the majority of data collection and contributed to the revisions of the article; and J.S.H. led the study design and contributed to the analysis, interpretation of data, and revisions of the article.

Funding: This study was funded by R01 MH098723.

Author Disclosure Statement

No conflicting financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. . Pre-exposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. New Engl J Med 2010;363:87–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson PL, Glidden DV, Liu A, et al. . Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med 2012;4:151ra125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, Bacon O, et al. . High interest in preexposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men at risk for HIV infection: Baseline data from the US PrEP demonstration project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;68:439–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider J, Bouris A, Smith D. Race and the public health impact potential of PrEP in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;70:30–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holmes D. FDA paves the way for pre-exposure HIV prophylaxis. Lancet 2012;380:325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan PA, Rose J, Maher J, et al. . A latent class analysis of risk factors for acquiring HIV among men who have sex with men: Implications for implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis programs. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2015;29:597–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CDC. HIV Among Gay and Bisexual Men [Internet]. Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, Sexual Transmitted Diseases and Tuberculosis Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015. Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/msm/index.html (Last accessed November11, 2015)

- 8.Myers J. A Public Health Approach to PrEP and PEP. New York, NY: NYC DOHMH, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 9.CDC. High-Impact HIV Prevention: CDC's Approach to Reducing HIV Infections in the United States [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011, p. 12 Available at: www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/policies_NHPC_Booklet.pdf (Last accessed November11, 2015)

- 10.Eaton LA, Driffin DD, Bauermeister , et al. . Minimal awareness and stalled uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among at risk HIV-negative, black men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs 2015;29:423–430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crosby RA, Geter A, DiClemente RJ, et al. . Acceptability of condoms, circumcision and PrEP among young black men who have sex with men: A descriptive study based on effectiveness and cost. Vaccines 2014;2:129–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sowicz TJ, Teitelman AM, Coleman CL, et al. . Considerations for implementing oral preexposure prophylaxis: A literature review. J Nurs AIDS Care 2014;25:496–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mimiaga MJ, Case P, Johnson CV, et al. . Preexposure antiretroviral prophylaxis attitudes in high-risk Boston area men who report having sex with men: Limited knowledge and experience but potential for increased utilization after education. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009;50:77–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golub SA, Kowalczyk W, Weinberger CL, et al. . Preexposure prophylaxis and predicted condom use among high-risk men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;54:548–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith DK, Toledo L, Smith DJ, et al. . Attitudes and program preferences of African-American urban young adults about pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). AIDS Educ Prev 2012;24:408–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Millett GA, Peterson JL, Wolitski RJ, et al. . Greater risk for HIV infection of black men who have sex with men: A critical literature review. Am J Public Health 2006;96:1007–1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flores SA, Bakeman R, Millett GA, et al. . HIV risk among bisexually and homosexually active racially diverse young men. Sex Transm Dis 2009;36:325–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eaton LA, Driffin DD, Smith H, et al. . Psychosocial factors related to willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among black men who have sex with men attending a community event. Sex Health 2014;11:244–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ayala G, Makofane K, Santos G-M, et al. . Access to basic HIV-related services and PrEP acceptability among men who have sex with men worldwide: Barriers, facilitators, and implications for combination prevention. J Sex Transm Dis Volume 2013 (2013), Article ID 953123, 11 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/953123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Oldenburg CE, Perez-Brumer AG, Hatzenbuehler ML, et al. . State-level structural sexual stigma and HIV prevention in a national online sample of HIV-uninfected MSM in the United States. AIDS 2015;29:837–845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia J, Parker C, Parker RG, et al. . Psychosocial implications of homophobia and HIV stigma in social support networks insights for high-impact HIV prevention among black men who have sex with men. Health Educ Behav 2015;1090198115599398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research [Internet]. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brooks RA, Kaplan RL, Lieber E, et al. . Motivators, concerns, and barriers to adoption of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among gay and bisexual men in HIV serodiscordant male relationships. AIDS Care 2011;23:1136–1145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galea JT, Kinsler JJ, Salazar X, et al. . Acceptability of pre-exposure prophylaxis as an HIV prevention strategy: Barriers and facilitators to pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake among at-risk Peruvian populations. Int J STD AIDS 2011;22:256–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Golub SA, Gamarel KE, Rendina HJ, et al. . From efficacy to effectiveness: Facilitators and barriers to PrEP acceptability and motivations for adherence among MSM and transgender women in New York City. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2013;27:248–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tangmunkongvorakul A, Chariyalertsak S, Amico KR, et al. . Facilitators and barriers to medication adherence in an HIV prevention study among men who have sex with men in the iPrEx study in Chiang Mai, Thailand. AIDS Care 2013;25:961–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Underhill K, Morrow KM, Colleran C, et al. . Explaining the efficacy of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention: A qualitative study of message framing and messaging preferences among US men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav 2015;1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.King HL, Keller SB, Giancola MA, et al. . Pre-exposure prophylaxis accessibility research and evaluation (PrEPARE Study). AIDS Behav 2014;18:1722–1725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brooks RA, Landovitz RJ, Regan R, et al. . Perceptions of and intentions to adopt HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among black men who have sex with men in Los Angeles. Int J STD AIDS 2015;0956462415570159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kubicek K, Arauz-Cuadra C, Kipke MD. Attitudes and perceptions of biomedical HIV prevention methods: Voices from young men who have sex with men. Arch Sex Behav 2015;44:487–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bauermeister J, Meanley S, Pingel E, et al. . PrEP awareness and perceived barriers among single young men who have sex with men. Curr HIV Res 2014;11:520–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khawcharoenporn T, Kendrick S, Smith K. HIV risk perception and preexposure prophylaxis interest among a heterosexual population visiting a sexually transmitted infection clinic. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2012;26:222–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu AY, Kittredge PV, Vittinghoff E, et al. . Limited knowledge and use of HIV post- and pre-exposure prophylaxis among gay and bisexual men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;47:241–247 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brooks RA, Landovitz RJ, Kaplan RL, et al. . Sexual risk behaviors and acceptability of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among HIV-negative gay and bisexual men in serodiscordant relationships: A mixed methods study. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2012;26:87–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van der Elst EM, Mbogua J, Operario D, et al. . High acceptability of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis but challenges in adherence and use: Qualitative insights from a phase I trial of intermittent and daily PrEP in at-risk populations in Kenya. AIDS Behav 2013;17:2162–2172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guest G, Shattuck D, Johnson L, et al. . Changes in sexual risk behavior among participants in a PrEP HIV prevention trial. Sex Transm Dis 2008;35:1002–1008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holt M, Murphy DA, Callander D, et al. . Willingness to use HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and the likelihood of decreased condom use are both associated with unprotected anal intercourse and the perceived likelihood of becoming HIV positive among Australian gay and bisexual men. Sex Transm Infect 2012;88:258–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mustanski B, Johnson AK, Garofalo R, et al. . Perceived likelihood of using HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis medications among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav 2013;17:2173–2179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Underhill K, Morrow KM, Colleran C, et al. . A qualitative study of medical mistrust, perceived discrimination, and risk behavior disclosure to clinicians by U.S. male sex workers and other men who have sex with men: Implications for biomedical HIV prevention. J Urban Health [Internet]. 2015. Available at: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11524-015-9961-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Pérez-Figueroa RE, Kapadia F, Barton SC, et al. . Acceptability of PrEP uptake among racially/ethnically diverse young men who have sex with men: The P18 study. AIDS Educ Prev 2015;27:112–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krakower DS, Mimiaga MJ, Rosenberger JG, et al. . Limited awareness and low immediate uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men using an internet social networking site. PLoS One 2012;7:e33119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mimiaga MJ, Closson EF, Kothary V, et al. . Sexual partnerships and considerations for HIV antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis utilization among high-risk substance using men who have sex with men. Arch Sex Behav 2014;43:99–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mutchler MG, McDavitt B, Ghani MA, et al. . Getting PrEPared for HIV prevention navigation: Young black gay men talk about HIV prevention in the biomedical era. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2015;29:490–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]