Abstract

Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) is a multifunctional growth factor in glioma cells and has been proved to be associated with the grade malignancy of glioma and prognosis of patients. Although there is evidence showing that bFGF plays an important role in proliferation, differentiation, angiogenesis, and survival of glioma cells, the effect of bFGF on chemosensitivity of glioma has not been verified. In this study, we analyzed the relationship between bFGF and chemotherapy resistance, with the objective of offering new strategy for chemotherapy of glioma patients. Here, siRNA was used to silence the expression of bFGF in glioma cell lines including U87 and U251 followed by chemotherapy of temozolomide (TMZ). Then, the characters of glioma including proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and cell cycle were studied in U87 and U251 cell lines. Our results demonstrated that silencing bFGF enhanced the effect of TMZ by inhibiting proliferation and migration, blocking cell cycle in G0/G1, and promoting apoptosis. In addition, the phosphorylation level of MAPK was measured to explore the mechanism of chemosensitization. The results showed that bFGF could promote the activation of the MAPK signal pathway. Our data indicated that bFGF might be a potential target for chemotherapy through the MAPK signal pathway.

Keywords: gliomas, bFGF, temozolomide, combined chemotherapy, drug resistance, chemosensitivity

Introduction

Glioma is one of the most common and malignant primary intracranial tumor in adults, which typically leads to progressive disability and eventually death. Up to now, the standard therapies for glioma include surgical resection followed by chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Unfortunately, even with this multimodality treatment, the median survival time of patients is still ~1 year [1]. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy after surgical resection are the necessary methods to prevent metastasis and recurrence [2]. But chemotherapy does not work well in some patients.

Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), a heparin-binding multifunctional growth factor, can promote the proliferation and angiogenesis on glioma cells through autocrine way [3]. bFGF has been proved to be overexpressed in glioma cells [4], and the expression level of bFGF was associated with the grade and prognosis of patients [5]. In our previous study, the depolarization of mitochondria and apoptosis was induced by delivery of bFGF interfering RNA [6]. In addition, down-regulating the expression of bFGF has been proved to inhibit tumorigenicity and metastasis [7].

Temozolomide (TMZ), an alkylating agent, does not require hepatic metabolism for activation, because TMZ could be spontaneously converted to the active form of alkylating agent (5-(3-N-methyltriazen-1-yl)-imidazole-4-carboxamide) (MTIC) [8]. TMZ can function as a broad-spectrum antitumor agent for several diseases such as melanoma, mesothelioma, lymphoma, sarcoma, leukemia, carcinoma of the ovary, carcinoma of the colon [9], and glioma [10]. Because of its extensive effects, chemotherapy inevitably has a wide range of side effects. Previous studies have shown the side effects including neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, lack of red blood cells, and hemoglobin when TMZ was administered in a dose-dependent manner [11].

However, the role of bFGF in the resistance of chemotherapy is still unclear. In this study, we tried to explore the relationship between bFGF and chemosensitivity. bFGF expression was silenced with specific siRNA and combined with TMZ to investigate its biological impact on glioma cells, which may help to develop new treatment strategies for glioma patients.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and treatment

Glioblastoma cell lines U87 and U251 were obtained from the Peking Union Medical College Cell Library (Beijing, China), and maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Grand Island, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in the appropriate atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The cells were divided into five groups: (1) siRNA negative control (NC) group (cells were transfected with NC); (2) TMZ group (cells were treated with TMZ alone); (3) TMZ + NC (cells were transfected with NC and then treated with TMZ); (4) bFGF-siRNA group (cells were transfected with bFGF-siRNA); and (5) union group (cells were transfected with bFGF-siRNA and then treated with TMZ). U87 and U251 cells were incubated in 6-well plates for 12 h, followed by cell transfections. At 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with or without TMZ (Sigma, St Louis, USA).

siRNA transfection

siRNAs were purchased from GenePharma (Shanghai, China). The sequence of siRNA targeting bFGF (5’-CGAACTGGGCAGTATAAAC-3’) was described as previously shown [9]. The sequence of NC was 5’-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3’. U87 and U251 cells were seeded into 6- or 96-well plates (Corning Costar, Cambridge, USA) and cultured for 12 h. siRNAs were transfected into the cells with Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The mixture of siRNA and Lipofectamine™ 2000 was added to culture medium for 6 h, and then the medium was changed with DMEM containing 10% FBS.

Western blot analysis

U87 and U251 cells were lyzed with the lysis buffer (CW Biotech, Beijing, China) containing protease inhibitor cocktails (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) for 30 min, followed by centrifuging at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. For each sample, 20 μg of total protein was subject to 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and then transferred onto polyvinyl difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in tris buffered saline with tween (TBST) buffer for 1.5 h at room temperature, and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. After being washed five times with TBST buffer, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and developed with the electrochemiluminescence (ECL) kit (Millipore, Billerica, USA). The primary anti-Bcl-2, anti-Bax, anti-matrix metalloproteinases-2 (MMP-2), and anti-MMP-9 antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, USA), and the anti-p-ERK1/2, anti-ERK1/2, anti-p-p38, anti-p38, anti-p-JNK, and anti-JNK primary antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, USA).

3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2-H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay

U87 and U251 cells were seeded into 96-well plates and transfected with NC or bFGF-siRNA, and then treated with TMZ for 48 h. The cell proliferation rate was measured at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h after TMZ treatment. Then, 20 μl of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenylteyrazolium bromide (MTT) (5 mg/ml; Sigma, St Louis, USA) was added into the supernatant. After 4 h of incubation, the medium was exchanged with 150 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma). The absorption at 490 nm was determined by a microplate reader.

Colony formation

U87 and U251 cells were seeded into 6-well plates and transfected with NC or bFGF-siRNA, and then treated with TMZ for 48 h. The cells were re-seeded into 6-well plates at the density of 500 cells/well for colony formation assay. The medium was replaced every 4 days. After the cells were cultured for 2 weeks, the number of colonies was counted.

Migration assay

The migration ability of U87 and U251 cells was detected using a transwell system with 8-μm pore size (Millipore). Cells were transfected with bFGF-siRNA, and then treated with TMZ for 48 h. The lower chamber was filled with 600 μl of culture medium containing 10% FBS, and the upper chamber was seeded with 104 cells from each group. After 24 h of incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and then stained with 1% crystal violet for 20 min. The cells of upper chamber were scraped off using a cotton bud prior to taking photos. Five different fields were randomly chosen in each well and the photos were taken.

Cell apoptosis analysis

U87 and U251 cells were seeded into 6-well plates and transfected with NC or bFGF-siRNA, and then treated with TMZ for 48 h. The cells (~1 × 105) were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and resuspended in 100 μl of binding buffer containing 5 μl of annexin V-FITC and 5 μl of propidium iodide (PI) (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, USA) in a tube. After 15 min of incubation at room temperature in the dark, another 400 μl of binding buffer was added into the tube. Samples were detected by fluorescence-activated cell sorter. The data were analyzed by FlowJo software (BD Pharmingen).

Flow cytometric analysis of cell cycle

U87 and U251 cells were cultured in 25-cm2 cell culture bottles (Corning Co, Corning, USA). The cells were transfected with NC or bFGF-siRNA, and then treated with TMZ for 48 h. The cells were harvested and washed with cold PBS. Then, the cells were fixed in cold 70% ethanol at 4°C overnight. The cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated with stain working solution (containing 50 μg/ml PI, 1% Triton X-100, and 1 mg/ml RNaseA) for 20 min at room temperature. The percentage of cells in each phase was analyzed by flow cytometry (BD Pharmingen).

Statistical analysis

The data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software 22.0, and compared with one-way analysis of variance. The P values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Silence of bFGF coincides with the increase in TMZ cytotoxicity

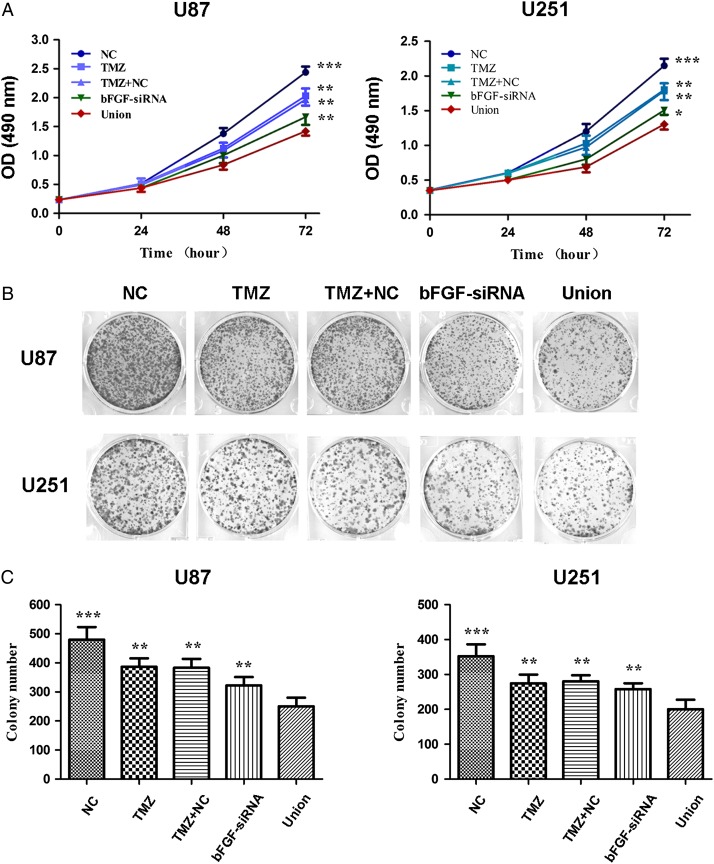

To explore whether silence of bFGF can enhance the inhibition ability of TMZ in U87 and U251 cell lines, the cell proliferation ability was detected by MTT at 24, 48, and 72 h. The results showed that cell proliferation was down-regulated by bFGF-siRNA transfection or TMZ treatment, and there was no difference between TMZ and TMZ + NC group in proliferation. In addition, the cell number was significantly decreased in the union group compared with that in bFGF-siRNA or TMZ alone group (Fig. 1A). Correspondingly, the cell proliferation ability was significantly inhibited by bFGF-siRNA transfection combined with TMZ.

Figure 1.

Effect of bFGF-siRNA treatment combined with TMZ on U87 and U251 cells proliferation (A) The U87 and U251 cell viability was measured at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h after combined treatment with bFGF-siRNA and TMZ. The combination with bFGF-siRNA and TMZ provided significant inhibition of cell growth, when compared with the NC, TMZ, TMZ + NC, and bFGF-siRNA group. (B) The cell proliferation was detected by colony formation assay to measure the effect of combined therapy in U87 and U251 cells. (C) The histogram showed that colony formation was significantly inhibited after combined treatment. The values were presented as the mean ± SD. The experiments were repeated at least three times with similar trends. *P < 0.5, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.0001.

To further verify the effect of bFGF-siRNA on the chemosensitivity to TMZ in U87 and U251 cell lines, the colony formation assay was performed (Fig. 1B). The results showed that the colony number reached the highest in NC group compared with other groups. TMZ or bFGF-siRNA treatment significantly decreased the colony number. There was no difference between TMZ and TMZ + NC group in colony formation. The combination of bFGF-siRNA and TMZ significantly inhibited colony formation ability of glioma cells when compared with cells treated with TMZ, TMZ + NC, or bFGF-siRNA transfection alone (Fig. 1C). Taken together, all these results suggested that silence of bFGF-siRNA had a significant effect on cell proliferation and increased the chemosensitivity to TMZ in U87 and U251 cells.

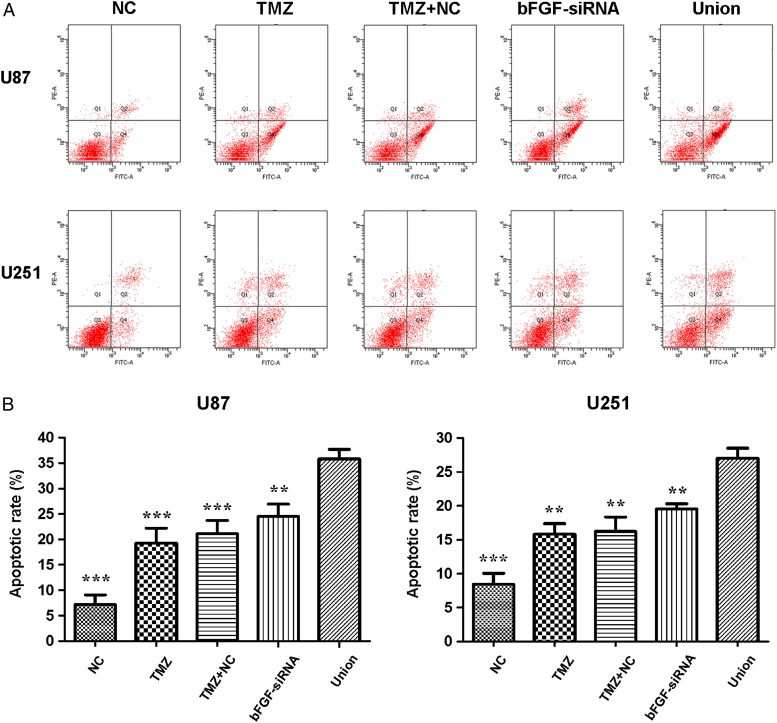

Silence of bFGF enhances TMZ-induced apoptosis

To investigate whether the combined treatment induced U87 and U251 cells apoptosis, cells were transfected with bFGF-siRNA or NC. After 24 h, the cells were treated with TMZ for 48 h, and cell apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. 2A). The results indicated that silence of bFGF or treated with TMZ could induce cell apoptosis, and there was no statistical difference between TMZ and TMZ + NC group in apoptosis. The number of apoptotic cells was significantly higher in the union group than that in TMZ, TMZ + NC, or bFGF-siRNA group (Fig. 2B). These results indicated that cells pretreated with bFGF-siRNA can enhance TMZ-induced cell apoptosis in U87 and U251 cells.

Figure 2.

Apoptosis analysis after treatment with bFGF-siRNA and TMZ (A) U87 and U251 cells were stained with PI and annexin V-FITC to detect apoptotic cells by flow cytometry. Combined treatment significantly promoted apoptosis of U87 and U251 cells. (B) The histogram showed the percentage of apoptotic cells. Data were expressed as mean ± SD. The experiments were repeated at least three times with similar trends. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.0001.

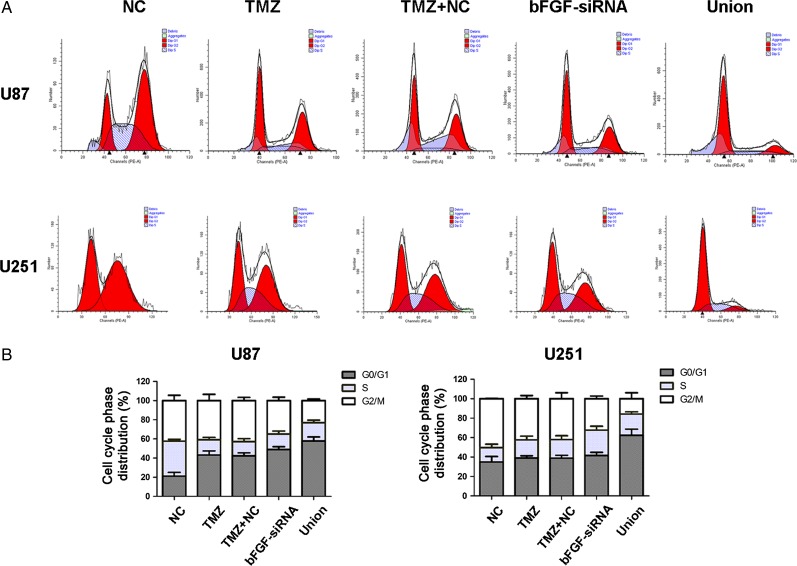

Silence of bFGF enhances TMZ-induced G0/G1 phase arrest

To investigate whether the combined treatment could modulate cell cycle progression in U87 and U251 cells, flow cytometry was performed to detect cell cycle distribution. The results of cell cycle analysis showed that TMZ or bFGF-siRNA induced G0/G1 arrest, and there was no significant difference between TMZ and TMZ+NC group. The percentage of G0/G1 in union group was significantly higher than that in the TMZ or bFGF-siRNA alone group (Fig. 3). These results implicated that silence of bFGF can enhance TMZ-induced G0/G1 phase arrest.

Figure 3.

Cell cycle analysis after treatment with bFGF-siRNA and TMZ (A) The flow cytometry was carried out to analyze U87 and U251 cell cycles using PI. Combined treatment with bFGF-siRNA and TMZ significantly induced G0/G1 phase arrest compared with NC, TMZ, TMZ + NC, and bFGF-siRNA group. (B) The histogram shows the percentage of cells in each phase. The results are indicated by mean ± SD. The experiments were repeated at least three times with similar trends.

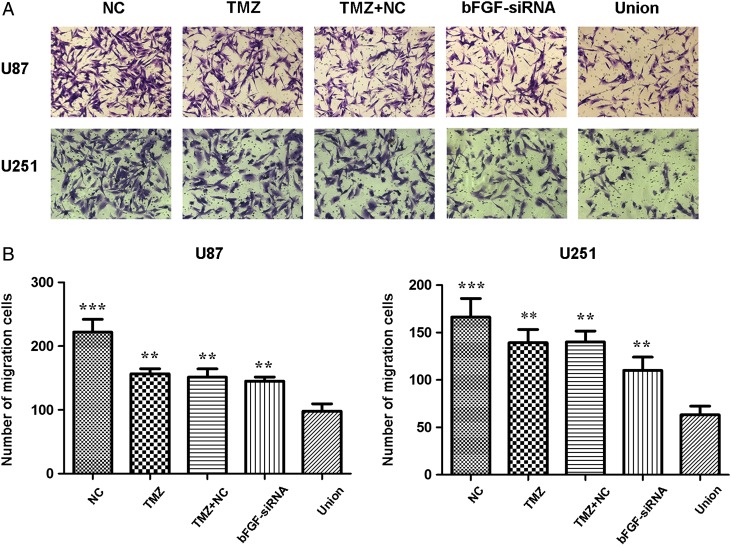

Silence of bFGF decreases the cell migration in response to TMZ

To detect whether the combined treatment suppressed migration of glioma cells, transwell assay was carried out. The results revealed that TMZ or bFGF-siRNA could decrease the ability of migration in U87 and U251 cells (Fig. 4). Additionally, the migration rate in the union group was the lowest when compared with that of TMZ, TMZ+NC, or bFGF-siRNA group.

Figure 4.

Cell migration analysis after treatment with bFGF-siRNA and TMZ (A) U87 and U251 cells were stained with crystal violet to detect migration by transwell assay. (B) The histogram showed that combined treatment with bFGF-siRNA and TMZ significantly restrained migration when compared with NC, TMZ, TMZ + NC, and bFGF-siRNA group. The results were shown as mean ± SD. The experiments were repeated at least three times with similar trends. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.0001.

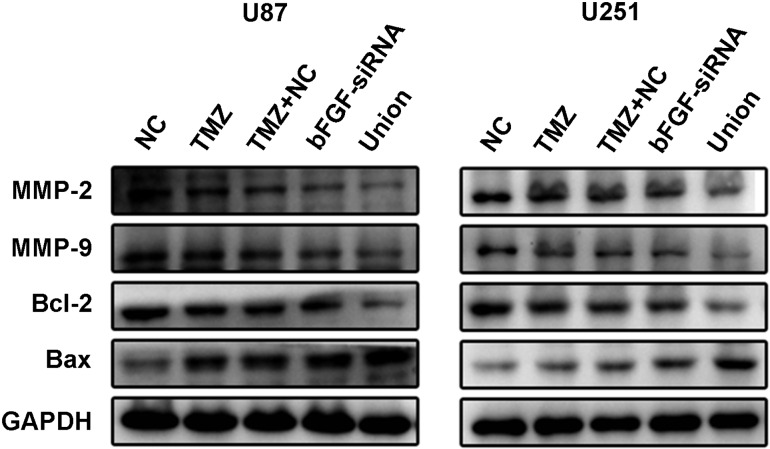

Silence of bFGF regulates the expression level of apoptotic- and migration-related protein in response to TMZ

To explore the molecule mechanism of apoptotic up-regulation, the expression levels of Bcl-2 and Bax were detected by the western blot analysis in U87 and U251 cell lines. It was shown that anti-apoptosis protein Bcl-2 was down-regulated in both TMZ group and bFGF-siRNA group, and there was no significant difference between TMZ group and TMZ + NC group (Fig. 5). The Bcl-2 was significantly down-regulated in union group compared with TMZ or bFGF-siRNA alone group. Correspondingly, pro-apoptotic protein Bax was up-regulated in groups of TMZ and bFGF-siRNA. The expression of Bax was significantly promoted when transfected with bFGF-siRNA combined with TMZ. The expression of migration-related proteins MMP-2 and MMP-9 was also examined. The results showed that the expressions of MMP-2 and MMP-9 were reduced in the TMZ and bFGF-siRNA groups (Fig. 5) when compared with the NC group. Moreover, MMP-2 and MMP-9 were significantly down-regulated in the union group compared with TMZ, TMZ + NC, or bFGF-siRNA groups. Taken together, the silence of bFGF regulated the expression level of apoptotic- and migration-related protein in response to TMZ.

Figure 5.

Expression levels of MMP-2, MMP-9, Bcl-2, and Bax in U87 and U251 cells after treatment with bFGF-siRNA and TMZ The expression levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in union group were inhibited significantly when compared with those in NC, TMZ, TMZ + NC, and bFGF-siRNA groups. The apoptosis repressor Bcl-2 was decreased and the expression level of Bax was increased in union group. The expression levels of Bcl-2 and Bax in union group were significantly different when compared with those in the NC, TMZ, TMZ + NC, and bFGF-siRNA groups. The experiments were repeated at least three times with similar trends.

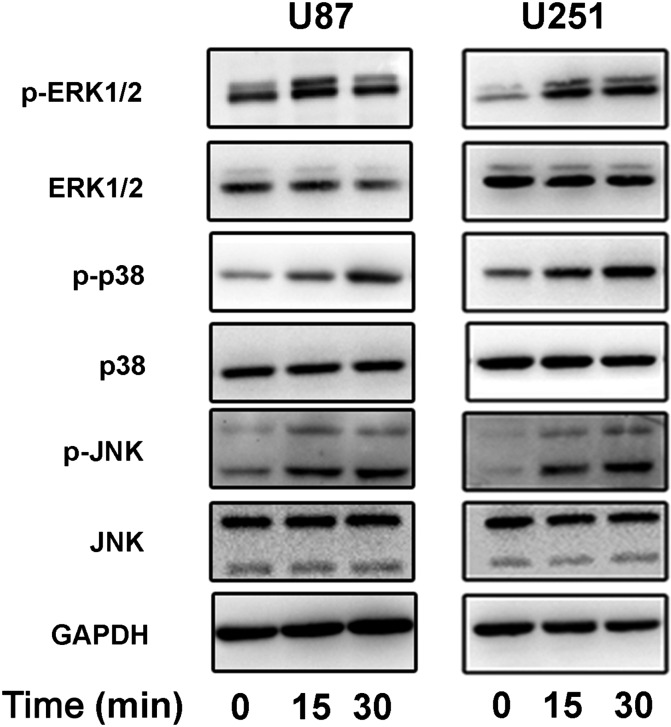

bFGF may induce the activation of the MAPK signal pathway

The MAPK signal pathway plays an important role in cellular processes, such as cell survival, proliferation, migration, and apoptosis [12,13]. To explore the signal pathway by which bFGF promoted the effects of TMZ in U87 and U251 cells, we detected the related protein phosphorylation level of MAPK. The cells without treatment were starved for 3 h in DMEM with 1% FBS, followed by cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS and bFGF (50 ng/ml) for 15 or 30 min. The cell lysates were analyzed using the western blot analysis (Fig. 6). The phosphorylation level of ERK1/2 was obviously enhanced at 15 min and the phosphorylation level of p38 was increased at 30 min. The JNK signal pathway was activated at 15 and 30 min, and there was no difference between these two time points. We speculated that bFGF-siRNA pre-regulated the MAPK signal pathway before chemotherapy. In other words, MAPK signal pathway may be related to the resistance of chemotherapy.

Figure 6.

MAPK signalling pathway activated by bFGF Western blot analysis showed that the phosphorylation levels of ERK1/2, p38, and JNK were enhanced after bFGF (50 ng/ml) stimulation. The experiments were repeated at least three times with similar trends.

Discussion

bFGF, as a multifunctional cytokine, is overexpressed in various cancers, including prostate cancer, basal cell carcinoma, multiple myeloma, breast cancer [14–16], and glioma [4]. bFGF is necessary for the formation of tumor stem cells derived from glioblastomas [17]. Fukui et al. [5] reported that bFGF is closely correlated with malignant grade of tumors and prognosis in patients with glioma. High expression level of bFGF could accelerate proliferation and angiogenesis, and blocking FGFR2 could inhibit glioma proliferation and angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo [18].

One of the main characteristics of cancer cells is the uncontrolled proliferation through mitosis. In this study, we pretreated cells with bFGF-siRNA to down-regulate the expression level of bFGF, and then exposed these cells to TMZ. We found that the combination treatment of bFGF-siRNA and TMZ was more effective in decreasing the proliferation and increasing the apoptosis of U87 and U251 cells than the cells treated with bFGF-siRNA or TMZ alone. Additionally, the cell cycle was blocked in the G0/G1 phase. To investigate the mechanism of this synergism, we detected the expression of apoptosis-related proteins, Bcl-2 and Bax. We found that Bcl-2 was decreased, whereas Bax was increased. Our findings were consistent with a previous report showing that bFGF could modulate the levels of Bcl-2 and Bax [19]. This regulation may be related to the MAPK pathway activated by bFGF, as demonstrated by the increased phosphorylation of ERK1/2, p38, and JNK upon bFGF stimulation.

Tumor migration frequently contributes to the failure of treatment [20]. Some researchers found that bFGF promoted migration via inducing cAMP-response element-binding protein phosphorylation and activation of downstream dual-specificity tyrosine-(Y)-phosphorylation regulated kinase 1 A [21]. To measure the migration ability, we performed the transwell assay to study the combined effect on the migration of glioma cells. The results revealed that pretreatment with bFGF-siRNA combined with TMZ decreased cell migration. MMPs can degrade extracellular matrix, but MMPs are synthesized as inactive zymogens, which require the dissociation of a propeptide by proteinase cleavage [22]. Park et al. [23] reported that the expression of MMP-9 was regulated via the p38MAPK pathway. In our research, the western blot analysis showed that the p38 pathway was also activated by the stimulation of bFGF. Therefore, further studies should focus on whether p38 is the bridge between bFGF and MMPs.

In this study, pretreatment with bFGF-siRNA was found to enhance the effect of TMZ on cell proliferation, apoptosis, and migration. Moreover, this approach could also relieve side effects by decreasing the clinical dosage of TMZ. However, the feasibilities should be explored in vivo. Additionally, bFGF not only modulates glioma cells viability but also relates to drug-resistant genes, such as apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease/redox facto-1 [24] and chloride intracellular channel 1 [25], which are confirmed by our findings that bFGF silence could enhance chemosensitivity to TMZ in glioma cells. Further study is needed to explore target proteins from the palindromia glioma patients with TMZ treatment using protein chip technology.

The MAPK has diverse biological functions in response to a broad-spectrum of stimulations, such as growth cytokines, stress, TGF-β, and ceramides [12]. The MAPK family members play a vital role in cell proliferation, differentiation, survival, and development [26–28] by activating gene expression, mitosis, and metabolism [29]. Additionally, Thomas and Huganir [27] have reported that the MAPK cascade pathway can regulate synaptic plasticity in the central nervous system in adult. The MAPK was up-regulated in the tumors. MAPK also plays an important role in the formation of tumor, including glioma [30]. Some researchers claimed that the MAPK-related pathway is associated with poorer prognosis [1]. In this study, we found that MAPK was overactivated by recombinant human bFGF in glioma. The angiogenesis requires synergism between bFGF and vascular endothelial growth factor [31]. We infer that the combination with bFGF-siRNA may weaken angiogenesis, and thereby decrease the supply of energy. This effect would further enhance the cytotoxicity of TMZ, which nevertheless needs to be verified in future studies.

In summary, we have demonstrated in this study that silence of bFGF with siRNA enhances the chemosensitivity of TMZ on glioma cells proliferation, apoptosis, and migration, indicating that targeting bFGF, combined with TMZ, may be a potential therapy strategy for glioma.

Funding

This work was supported by the grants from the National Key Technology Support Program (No. 2014BAI04B00) and the Foundation of Tianjin Science and Technology Committee (No. 14JCZDJC35600).

References

- 1.Mawrin C, Diete S, Treuheit T, Kropf S, Vorwerk CK, Boltze C, Kirches E, et al. Prognostic relevance of MAPK expression in glioblastoma multiforme. Int J Oncol 2003, 23: 641–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mrugala MM. Advances and challenges in the treatment of glioblastoma: a clinician’s perspective. Discov Med 2013, 15: 221–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gately S, Soff GA, Brem S. The potential role of basic fibroblast growth factor in the transformation of cultured primary human fetal astrocytes and the proliferation of human glioma (U-87) cells. Neurosurgery 1995, 37: 723–730; discussion 730–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baguma-Nibasheka M, Li AW, Murphy PR. The fibroblast growth factor-2 antisense gene inhibits nuclear accumulation of FGF-2 and delays cell cycle progression in C6 glioma cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2007, 267: 127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukui S, Nawashiro H, Otani N, Ooigawa H, Nomura N, Yano A, Miyazawa T, et al. Nuclear accumulation of basic fibroblast growth factor in human astrocytic tumors. Cancer 2003, 97: 3061–3067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu J, Xu X, Feng X, Zhang B, Wang J. Adenovirus-mediated delivery of bFGF small interfering RNA reduces STAT3 phosphorylation and induces the depolarization of mitochondria and apoptosis in glioma cells U251. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2011, 30: 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi JA, Fukumoto M, Kozai Y, Ito N, Oda Y, Kikuchi H, Hatanaka M. Inhibition of cell growth and tumorigenesis of human glioblastoma cells by a neutralizing antibody against human basic fibroblast growth factor. FEBS Lett 1991, 288: 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stevens MF, Hickman JA, Langdon SP, Chubb D, Vickers L, Stone R, Baig G, et al. Antitumor activity and pharmacokinetics in mice of 8-carbamoyl-3-methyl-imidazo[5,1-d]-1,2,3,5-tetrazin-4(3H)-one (CCRG 81045; M & B 39831), a novel drug with potential as an alternative to dacarbazine. Cancer Res 1987, 47: 5846–5852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel M, McCully C, Godwin K, Balis FM. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid pharmacokinetics of intravenous temozolomide in non-human primates. J Neurooncol 2003, 61: 203–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman HS, Kerby T, Calvert H. Temozolomide and treatment of malignant glioma. Clin Cancer Res 2000, 6: 2585–2597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dinnes J, Cave C, Huang S, Milne R. A rapid and systematic review of the effectiveness of temozolomide for the treatment of recurrent malignant glioma. Br J Cancer 2002, 86: 501–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang W, Liu HT. MAPK signal pathways in the regulation of cell proliferation in mammalian cells. Cell Res 2002, 12: 9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zohrabian VM, Forzani B, Chau Z, Murali R, Jhanwar-Uniyal M. Rho/ROCK and MAPK signaling pathways are involved in glioblastoma cell migration and proliferation. Anticancer Res 2009, 29: 119–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jee SH, Chu CY, Chiu HC, Huang YL, Tsai WL, Liao YH, Kuo ML. Interleukin-6 induced basic fibroblast growth factor-dependent angiogenesis in basal cell carcinoma cell line via JAK/STAT3 and PI3-kinase/Akt pathways. J Invest Dermatol 2004, 123: 1169–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bisping G, Leo R, Wenning D, Dankbar B, Padro T, Kropff M, Scheffold C, et al. Paracrine interactions of basic fibroblast growth factor and interleukin-6 in multiple myeloma. Blood 2003, 101: 2775–2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y, Wang JL, Chang H, Barsky SH, Nguyen M. Breast-cancer diagnosis with nipple fluid bFGF. Lancet 2000, 356: 567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee J, Kotliarova S, Kotliarov Y, Li A, Su Q, Donin NM, Pastorino S, et al. Tumor stem cells derived from glioblastomas cultured in bFGF and EGF more closely mirror the phenotype and genotype of primary tumors than do serum-cultured cell lines. Cancer Cell 2006, 9: 391–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Auguste P, Gursel DB, Lemiere S, Reimers D, Cuevas P, Carceller F, Di Santo JP, et al. Inhibition of fibroblast growth factor/fibroblast growth factor receptor activity in glioma cells impedes tumor growth by both angiogenesis-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Cancer Res 2001, 61: 1717–1726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Konig A, Menzel T, Lynen S, Wrazel L, Rosen A, Al-Katib A, Raveche E, et al. Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) upregulates the expression of bcl-2 in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia cell lines resulting in delaying apoptosis. Leukemia 1997, 11: 258–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Itoh Y, Palmisano R, Anilkumar N, Nagase H, Miyawaki A, Seiki M. Dimerization of MT1-MMP during cellular invasion detected by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Biochem J 2011, 440: 319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kottakis F, Polytarchou C, Foltopoulou P, Sanidas I, Kampranis SC, Tsichlis PN. FGF-2 regulates cell proliferation, migration, and angiogenesis through an NDY1/KDM2B-miR-101-EZH2 pathway. Mol Cell 2011, 43: 285–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munaut C, Noel A, Hougrand O, Foidart JM, Boniver J, Deprez M. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression correlates with matrix metalloproteinases MT1-MMP, MMP-2 and MMP-9 in human glioblastomas. Int J Cancer 2003, 106: 848–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park SL, Hwang B, Lee SY, Kim WT, Choi YH, Chang YC, Kim WJ, et al. p21WAF1 Is Required for Interleukin-16-Induced Migration and Invasion of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells via the p38MAPK/Sp-1/MMP-9 Pathway. PLoS One 2015, 10: e0142153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montaldi AP, Godoy PR, Sakamoto-Hojo ET. APE1/REF-1 down-regulation enhances the cytotoxic effects of temozolomide in a resistant glioblastoma cell line. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen 2015, 793: 19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang MK, Kang SK. Pharmacologic blockade of chloride channel synergistically enhances apoptosis of chemotherapeutic drug-resistant cancer stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2008, 373: 539–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagner EF, Nebreda AR. Signal integration by JNK and p38 MAPK pathways in cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer 2009, 9: 537–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas GM, Huganir RL. MAPK cascade signalling and synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci 2004, 5: 173–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seger R, Krebs EG. The MAPK signaling cascade. FASEB J 1995, 9: 726–735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roux PP, Blenis J. ERK and p38 MAPK-activated protein kinases: a family of protein kinases with diverse biological functions. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2004, 68: 320–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.von Deimling A, Louis DN, Wiestler OD. Molecular pathways in the formation of gliomas. Glia 1995, 15: 328–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pepper MS, Ferrara N, Orci L, Montesano R. Potent synergism between vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor in the induction of angiogenesis in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1992, 189: 824–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]