Abbreviations

- GT

Glanzmann thrombasthenia

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- GP

glycoprotein

- ADP

adenosine diphosphate

- PAF

platelet activating factor

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- Bp

base pair

- CAP‐1

canine‐activated platelet‐1

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

A 2‐year‐old, female intact, mixed‐breed dog was presented to the Bailey Small Animal Teaching Hospital at Auburn University for investigation of lifelong, intermittent petechial hemorrhage. Historically, the dog also had excessive gingival bleeding during tooth eruption. The dog was found as a stray and was 1 of a litter of puppies. A male sibling was reported to have a similar history of petechial and ecchymotic hemorrhages and its owner was later contacted and the dog brought to the teaching hospital for platelet aggregation studies.

Before referral, the female dog was managed by the referring veterinarian for suspected immune‐mediated thrombocytopenia with prednisolone 5 mg PO q12h, doxycycline 5 mg PO q12h, famotidine 10 mg PO q24h, and sucralfate 250 mg PO q8–12h. A SNAP 4DX1 was negative and other testing, including von Willebrand Factor (VWF) antigen and a coagulation panel was normal (VWF, 113%; reference interval [RI], 70–180%; prothrombin time, 6.6 seconds; RI, 5.5–12; activated partial thromboplastin time, 11.3 seconds; RI, 10–25).

The dog consistently had platelet counts just below the lower limit of the RI (170–400 × 103/μL) on referring laboratory tests, but the platelet count was not low enough to account for the platelet‐associated bleeding seen. No correlation was identified between increases or decreases in the prednisolone dosage and improvement in platelet counts or the development of petechiation. Immune‐mediated vasculitis was suspected before referral to the Bailey Small Animal Teaching Hospital at Auburn University.

On presentation, the dog was bright and alert. Routine vaccinations were not current. On physical examination, the dog was moderately overweight and petechiae were noted on the ventral abdomen and the inner left thigh. Laboratory testing identified mild anemia (hematocrit, 38.4%; RI, 38.7–59.2%), a moderate neutrophilia (19,627 μL; RI, 2.6–10.4 × 103/μL), and normal platelet counts (210 × 103/μL; RI, 152–518 × 103/μL). Serum biochemistry results were normal. Thoracic radiographs were within normal limits, and the hyperechoic appearance of the liver on abdominal ultrasound examination was consistent with the previous history of steroid treatment but otherwise normal. A buccal mucosal bleeding time was markedly abnormal with prolonged mucosal bleeding >5 minutes (RI, ≤5 minutes). Platelet function studies, including platelet aggregation, clot retraction, and flow cytometry were performed. A hereditary platelet function disorder was suspected given the lifelong history of petechial hemorrhage and lack of clinically relevant findings on diagnostic tests performed that could explain an acquired platelet disorder. The owner was contacted to inquire about possible affected littermates, 1 of which was found and tested at a later time.

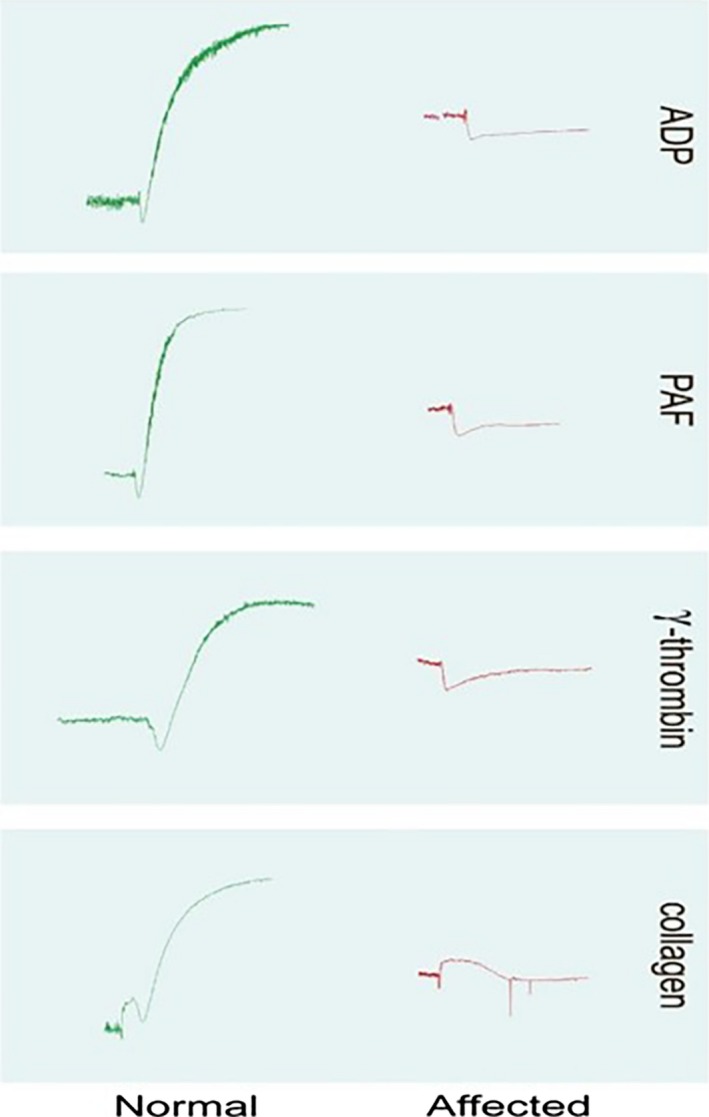

Blood was collected by jugular venipuncture into 3.8% trisodium citrate at a ratio of 9 : 1 from the patient, sibling, and control dogs for isolation of platelet‐rich plasma (PRP). Pressure was applied to the venipuncture site for approximately 10 minutes and then wrapped while the patients were hospitalized. Platelet responses to adenosine diphosphate (ADP), collagen, epinephrine, platelet‐activating factor (PAF), and gamma thrombin were evaluated in a dual channel platelet aggregometer.2 , 1 With the exception of epinephrine, platelets from the control dog responded with shape change and irreversible platelet aggregation to all agonists tested. In contrast, platelets from the patient and sibling underwent shape change responses but failed to aggregate in response to all agonists tested (Fig 1). Epinephrine added before agonist addition enhanced platelet aggregation responses in the control dog but failed to result in platelet aggregation in the patient or the patient's sibling (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Representative platelet aggregometer tracings obtained for the affected dogs and a control dog are shown. Affected dog platelets underwent shape change but failed to aggregate in response to all agonists tested.

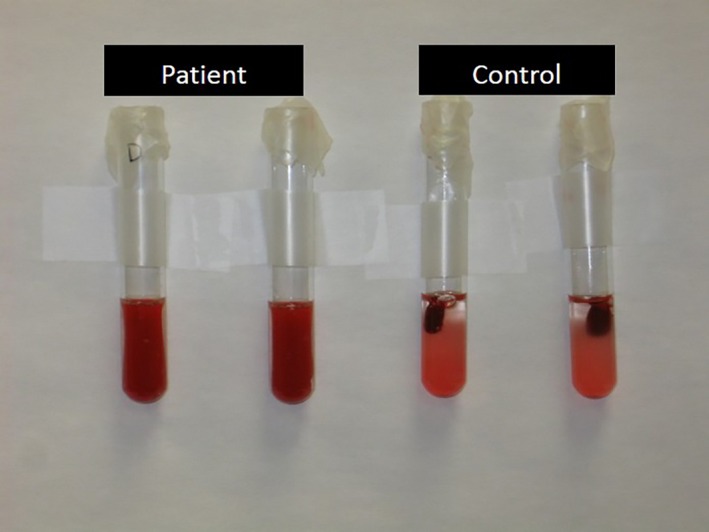

Citrated whole blood (0.5 mL) diluted in 4.5 mL saline was used for the clot retraction assay. Thrombin (1 Unit final concentration) was used to induce clot formation in samples run in duplicate from the patient, sibling, and control dog. Samples were incubated in a 37°C water bath and the degree of clot retraction was monitored at 1 and 2 hours as 1+ to 4+. Clot retraction failed to occur in the sample from the patient and the patient's sibling. The inability of platelets to aggregate in response to multiple agonists accompanied by failure of clot retraction was consistent with a diagnosis of Glanzmann thrombasthenia (GT; Fig 2).

Figure 2.

Clot retraction. In the normal control dog, the clot has retracted. In the affected patient, the sample has clotted; however, platelets are unable to bind fibrinogen and mediate clot retraction.

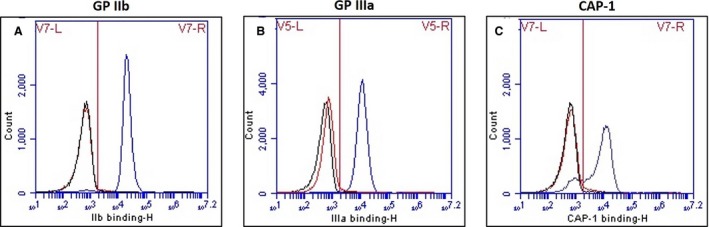

To confirm a diagnosis of GT, flow cytometry was performed to detect the presence of each protein in the glycoprotein (GP) IIb–IIIa complex on the platelet surface in the patient and sibling. Monoclonal antibodies were added to diluted PRP samples. Antibodies used included Y2/51,3 an anti‐human GPIIIa antibody that recognizes canine GPIIIa, 2F9 (gift from Dr S.A. Burstein, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center), an antibody recognizing canine GPIIb, and canine‐activated platelet‐1 (CAP‐1), an antibody recognizing a receptor‐induced binding site on canine fibrinogen.1 Antibody binding was detected using fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)‐labeled goat anti‐mouse IgG.4 Monoclonal antibodies to GPIIb and GPIIIa bound normally to control dog platelets. CAP‐1 monoclonal antibody binding occurred normally when control dog platelets were activated with ADP (Fig 3). Monoclonal antibodies to GPIIb failed to bind to platelets of the patient or sibling, whereas a very small amount of binding of monoclonal antibodies to GPIIIa was detected on platelets obtained from both dogs. GPIIIa monoclonal antibody binding was likely because of binding of the β3 subunit of the vitronectin receptor complex, which is present in much smaller numbers compared to GPIIb–IIIa on the platelet surface.2 CAP‐1 monoclonal antibody binding did not occur in nonactivated or activated platelet samples obtained from both dogs (Fig 3) confirming GT in these related mixed‐breed dogs.

Figure 3.

Representative flow cytometry findings for affected dogs and positive control. The black curve indicates the negative control (background antibody binding), the red curve indicates antibody binding for affected dogs, and the blue curve indicates the positive control (normal control dog). Affected dogs were negative for (A) GPIIb and (C) CAP‐1 antibody binding and minimally positive for (B) GPIIIa, likely because of binding to the vitronectin receptor on platelet surfaces.

Genomic DNA was extracted from EDTA blood samples.5 For RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis, aliquots of PRP were transferred to tubes and prostaglandin E1 was added (3 μM final concentration) before centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 15 minutes to form platelet pellets. Plasma was removed and the pellets were resuspended in a small amount of HEPES buffer and transferred to RNase‐free tubes and centrifuged again. Residual buffer was removed from platelet pellets and the pellets frozen at −80°C until use. RNA was extracted from washed platelet pellets6 and converted to cDNA.7 Primers for polymerase chain reactions (PCR) using genomic DNA as templates were designed to assess all coding areas and exon‐intron splice sites of the genes encoding GPIIb and GPIIIa. PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis on agarose gels and target bands were harvested8 for sequencing.9 A subset of primers was also designed for use with cDNA templates to evaluate for the presence of alternate splicing. Amplified and harvested DNA and cDNA sequences were compared to the published canine sequence in GenBank.

The DNA sequence of the patient was uniform throughout the segments of DNA evaluated. Heterozygosity was not detected at any point in any of the samples evaluated, despite the patient being a mixed‐breed dog, suggesting that the dog's sire and dam were closely related.

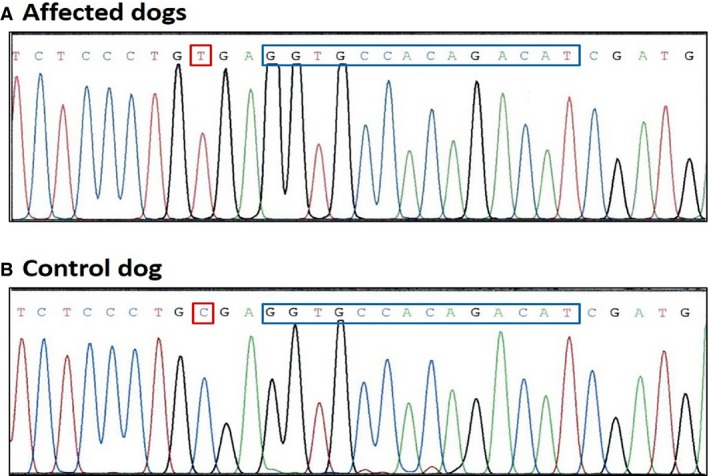

No polymorphisms were detected in the gene encoding GPIIIa. Four single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) were detected in the gene encoding GPIIb. Polymorphisms identified in exon 16 (C1507T), exon 18 (G1726A), and exon 20 (A1974C) were predicted to change encoded amino acids at positions 503 (P503S), 576 (G576R), and 658 (Q658H). These SNP were not considered functionally relevant because they had previously been documented in normal dogs (M. K. Boudreaux, unpublished observations) and were located in regions of the gene that are not highly conserved. The fourth SNP, a single nucleotide change at position 1264 in exon 13 (C1264T), resulted in a nonsense mutation (CGA > TGA) at the codon encoding arginine (R) at position 422 (R422X; Fig 4). The same mutation was found in the patient's sibling. This SNP documents the third mutation resulting in GT in dogs, and the first to be found in mixed‐breed dogs (Table 1).

Figure 4.

A SNP at position 1,264 in exon 13 (C1264T) resulted in a nonsense mutation (CGA > TGA) at the codon encoding arginine (indicated by red box). (A) (upper sequence) is sequence from the affected dogs, and (B) (lower sequence) is normal sequence from a control dog. The location of the 14 bp repeat in exon 13 that occurs in Great Pyrenees dogs with GT is also outlined by the blue box.

Table 1.

Mutations found in dogs and horses resulting in GT

| Disorder | Mutation | |

|---|---|---|

| Dogs | ||

| Great Pyrenees | Glanzmann thrombasthenia | IIb, exon 13, 14 base pair repeat |

| Otterhound | Glanzmann thrombasthenia | IIb, exon 12, GAC to CAC (D367H) |

| Mixed‐breed | Glanzmann thrombasthenia | IIb, exon 13, CGA to TGA (R422X)a |

| Horses | ||

| TB | Glanzmann thrombasthenia | IIb, exon 2, CGG to CCG (R41P) |

| QH‐X | ||

| OB | ||

| QH‐X | Glanzmann thrombasthenia | IIb, exon 11, 10 base deletion |

| Paso Fino | ||

TB, Thoroughbred; QH‐X, quarter horse cross; OB, Oldenburg.

This mutation has been documented in people.

Polymerase chain reaction performed on cDNA from the affected dog that encompassed exon 7 to exon 15 did not generate a band at the expected target (818 bp) but did generate a band that migrated at approximately 625 bp. Sequencing of this band indicated that all of the exons amplified were present except for exon 13 (exon 12 and exon 14 were contiguous). The absence of a band at the expected target size was presumed to be because of nonsense‐mediated mRNA decay. When normal dog cDNA was subjected to PCR under the same conditions, 2 bands were visualized (818 and 625 bp). Sequencing of these bands showed normal presence of exon 13 for the band at the target site but skipping of exon 13 in the band at the 625 bp position. The presence of the smaller bands in both the patient and control dog indicated that alternative splicing was not caused by the presence of the nonsense mutation.

Glanzmann thrombasthenia is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by a quantitative or qualitative defect of the platelet GP complex IIb–IIIa (GPIIb–IIIa), also known as the fibrinogen receptor or integrin αIIbβ3. Mutations in either of the genes encoding GPIIb or GPIIIa can result in GT. This defect results in impaired platelet aggregation and absent clot retraction.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Characteristic clinical signs are caused by failure of primary hemostasis and include mucosal hemorrhage and epistaxis.1, 2, 3, 4

In humans, the defect has been subdivided into 3 categories. Type 1 GT is characterized by severe quantitative decrease in the GPIIb–IIIa complex. Type 2 GT is characterized by a moderate quantitative decrease in the GPIIb–IIIa complex, whereas variant GT is characterized by qualitative decrease in function with relatively normal quantities of proteins.1, 2 All mutations found in animals to date have been within the gene encoding GPIIb.3, 4, 6, 7

Otterhounds with thrombasthenic thrombopathia described in the 1960s were the only known dogs with a platelet function disorder that closely resembled GT until 1996, when a Great Pyrenees dog was identified with Type I GT.1 Molecular studies performed in 1999 allowed for the identification of the specific mutations causing Type I GT in both Otterhounds and Great Pyrenees dogs.3, 4 Additional mutations causing GT have now been identified in several breeds of horses.4, 6

Great Pyrenees dogs with GT were found to have a 14‐base‐pair repeat in exon 13 of the gene encoding GPIIb. This repeat causes a frame shift resulting in the appearance of a premature stop codon.4 Otterhounds were found to have a single nucleotide change in exon 12, resulting in the substitution of a histidine for an aspartic acid within the third calcium‐binding domain of GPIIb. Such a change would be expected to destabilize the GPIIb–IIIa complex.3

Molecular studies in this case confirmed 4 SNPs in the gene encoding GPIIb; 3 of which were not considered functionally relevant. The fourth SNP, a single nucleotide change at position 1,264 in exon 13, results in the appearance of a premature stop codon at the codon for arginine at position 422. This mutation previously has been documented in people (human GT database).

Although there have been several studies in people examining platelet alloantigens, there have been limited studies examining the role of platelet alloantigens in veterinary species. In this case, 3 of the polymorphisms found in the gene encoding GPIIb were not considered functionally relevant, but they are predicted to result in an amino acid residue change. This finding may suggest a role in alloimmunity. In people, alloantigens identified on platelet surfaces have been associated with platelet transfusion refractoriness, posttransfusion thrombocytopenic purpura, as well as neonatal thrombocytopenia.8 Of all alloimmune reactions described in human patients, platelet transfusion reactions are the most likely of the alloimmune platelet reactions to occur in dogs.9 One study10 identified SNPs in the genes encoding major platelet GPs within the Equidae family.10 Another study9 examined polymorphisms in canine platelet GPs and their potential role as platelet antigens. Both studies highlight several polymorphisms in the equine and canine genome but additional studies are required to determine whether the predicted amino acid differences result in alloimmunity.9, 10 The ability to manage and diagnose conditions associated with platelet alloimmunity should improve as the molecular basis of platelet antigen systems becomes known.

The present study describes a third mutation in the gene encoding GPIIb resulting in GT in dogs. Glanzmann thrombasthenia should be a differential diagnosis for platelet‐associated bleeding in dogs with normal VWF concentration and activity and normal platelet counts. Platelet function studies and molecular assays may be used to identify additional cases of GT and unique mutations in the genes encoding platelet GPIIb and IIIa in other dog breeds. Furthermore, future molecular studies of platelet membrane GPs may aid in the identification of potential alloantigens and further characterization of the canine platelet antigen system.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Kevin King for his valuable technical assistance.

Conflict of Interest Declaration: The authors disclose no conflict of interest.

Off‐label Antimicrobial Declaration: The authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobials.

The study was performed at the Bailey Small Animal Teaching Hospital and the Department of Pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Auburn, Alabama.

The study was not supported by a grant.

Footnotes

SNAP4DX, IDEXX Laboratories, Westbrook, ME

Platelet aggregometer, Chrono‐log Corp, Havertown, PA

Antibody Y2/51, DAKO, Carpinteria, CA

FITC‐labeled goat anti‐mouse IgG antigen‐binding fragments (Fab), Beckman Coulter, Atlanta, GA

QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit, Qiagen Inc., Germantown, MD

RNeasy Plus Mini Kit, Qiagen Inc.

iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit, Bio‐Rad, Hercules, CA

QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit, Qiagen Inc.

Eurofins Genomics, Huntsville, AL

References

- 1. Boudreaux MK, Kvam K, Dillon AR, et al. Type I Glanzmann's thrombasthenia in a Great Pyrenees dog. Vet Pathol 1996;33:503–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boudreaux MK, Lipscomb DL. Clinical, biochemical, and molecular aspects of Glanzmann's thrombasthenia in humans and dogs. Vet Pathol 2001;38:249–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boudreaux MK, Catalfamo JL. Molecular and genetic basis for thrombasthenic thrombopathia in Otterhounds. Am J Vet Res 2001;62:1797–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Christopherson PW, Insalaco TA, Santen VLV, et al. Characterization of the cDNA encoding aIIb and b3 in normal horses and two horses with Glanzmann thrombasthenia. Vet Pathol 2006;43:78–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Solh T, Botsford A, Solh M. Glanzmann's thrombasthenia: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and current and emerging treatment options. J Blood Med 2015;6:219–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Christopherson PW, Santen VLV, Livesey L, Boudreaux MK. A 10‐base‐pair deletion in the gene encoding platelet glycoprotein IIb associated with Glanzmann thrombasthenia in a horse. J Vet Intern Med 2007;21:196–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lipscomb DL, Bourne C, Boudreaux MK. Two genetic defects in aIIb are associated with type I Glanzmann's thrombasthenia in a Great Pyrenees Dog: A 14‐base insertion in exon 13 and a splicing defect of intron 13. Vet Pathol 2000;37:581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rozman P. Platelet antigens. The role of human platelet alloantigens (HPA) in blood transfusion and transplantation. Transpl Immunol 2002;10:165–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Callan MB, Werner P, Mason NJ, et al. Polymorphisms in canine platelet glycoproteins identify potential platelet antigens. Comp Med 2013;63:348–354. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boudreaux MK, Humphries DM. Identification of potential platelet alloantigens in the Equidae family by comparison of gene sequences encoding major platelet membrane glycoproteins. Vet Clin Pathol 2013;42:437–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]