Abbreviations

- BoNT

botulinum neurotoxin

- CMAP

compound muscle action potential

- RNS

repetitive nerve stimulation

A 10‐day‐old female, 42 kg pony/Paint horse cross filly was presented to the University of California Davis, William R. Pritchard Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital (VMTH) for low head and neck carriage, suspected to be caused by a fractured cervical vertebrae. For 3 days after parturition, no abnormalities were noted. At 4 days of age, the foal began to exhibit progressive weakness, an inability to rise unassisted, low head carriage, and an inability to nurse without manual support of the head. Radiographs of the cervical vertebrae, complete blood count (CBC), and serum biochemistry profile obtained 4 days before admission did not reveal abnormalities. The foal had received no medications nor had serum IgG concentrations been measured. The dam had one previous foal with no complications and had not been vaccinated in 2 years.

On presentation, the foal was in lateral recumbency and unable to rise unassisted. The owners had assisted her to rise, and supported her head in order to nurse every 2 hours while en route to the hospital. No abnormalities were noted on physical examination other than weakness and an inability to maintain the head and neck in a normal position and posture. Cranial nerve examination was within normal limits. With assistance to stand, the foal was able to ambulate but the gait was short and stiff, and the foal tired quickly. The neck was extended with the head held in a neutral position. No evidence of pain could be elicited on flexion of the neck in either a vertical or horizontal plane. There was a decrease in tone through the dorsal cervical musculature that allowed abnormal hyperextension of the nuchal ligament and neck. The foal was able to suckle well with the head supported, with normal tongue tone and no signs of aspiration.

Repeat radiographs of the cervical vertebrae, CBC, and arterial blood gas analysis did not reveal abnormalities. Because of an inability to nurse unassisted and concerns over the potential for aspiration, an intravenous catheter was placed in the jugular vein and a nasogastric feeding tube was placed. Serum and whole blood submitted for vitamin E and selenium testing, respectively, showed a low whole blood selenium concentration (0.051 ppm; ref: 0.08–0.5 ppm) and a normal vitamin E concentration (3.7 ppm; ref >2 ppm adequate). Ultrasonography of the umbilical structures showed asymmetric umbilical arteries and a mildly hyperechoic left umbilical artery, although both measured within normal limits (<9 mm).

Because of the progressive weakness, without other clinical or hematologic abnormalities, toxicoinfectious botulism was suspected. Botulism types A and C were considered the most likely serotypes in this foal, having been born on the West coast of the United States.

Initial therapy included administration of divalent plasma (18 mL/kg, IV), containing antibodies to C. botulinum Type B and C toxins.1 When it became available 24 hours later, trivalent plasma, with antibodies to Types A, B, and C2 (12 mL/kg), was administered. The foal was administered polyionic fluids3 at 4 mL/kg/h for 48 hours and the rate was adjusted to maintain 6 mL/kg/h total rate in combination with the plasma. Additional therapeutics included: potassium penicillin4 (22,000 mg/kg, IV, q6h), selenium5 (2.5 mg or 1 mL/50 kg, IM, once), omeprazole6 (4 mg/kg, PO, q24h), and vitamin E7 (10 IU/kg, PO, q24h). The foal was assisted to stand, or the recumbent side was alternated, every 2 hours. She was fed 12% of body weight daily as a mixture of mare milk and a commercial milk replacer.8 The foal was weaned onto the commercial milk replacer, and the amount fed was increased to 25% of body weight as she became more active. The transition to milk replacer was initiated because of the unavailability of mare's milk. To treat constipation, a frequent complication of botulism, the foal was administered enemas as well as mineral oil9 (1 mL/kg, through NG administration) once. A fecal sample collected at the time of admission was submitted for PCR detection of C. botulinum toxin genes at The National Botulism Reference Laboratory, The University of Pennsylvania.

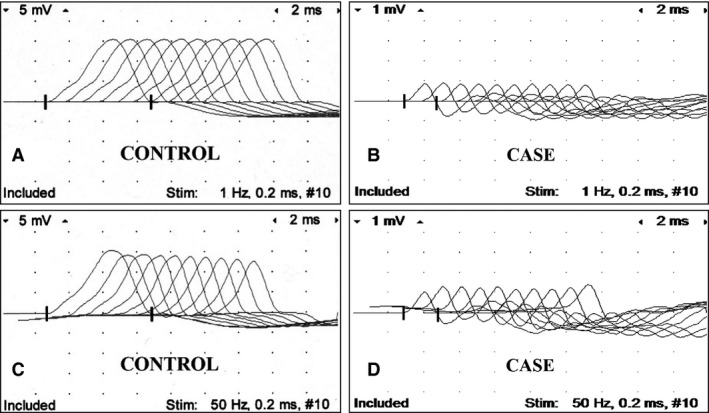

On the second day of hospitalization, repetitive nerve stimulation (RNS) of the common peroneal nerve was performed. The foal was sedated with diazepam10 (0.24 mg/kg IV, total), xylazine11 (1 mg/kg IV total, in 0.24 mg/kg increments), and butorphanol12 (0.69 mg/kg IV total, in 0.23 mg/kg increments). This electrodiagnostic test was performed as previously described.1 Briefly, one stimulating electrode was placed on each side of the common peroneal nerve, 1 inch apart, at the caudal border of the gastrocnemius muscle distal to the stifle. For recording, the active electrode was positioned over the midpoint of the extensor digitorum longus muscle, and the reference electrode was placed at the distal end of this muscle. A subdermal needle electrode was used as a ground and placed between the stimulating and recording electrodes. Repeated supramaximal stimulation of the nerve was performed, utilizing a range of frequencies (1 to 50 Hz). Stimulus duration was 0.2 ms with trains of 10 stimuli delivered at each stimulus repetition rate. Data analyses consisted of measuring the amplitude and area under the curve for each compound muscle action potential (CMAP), and converting these values into percentages of decrement or increment based on the comparison of subsequent potentials to the initial one (baseline) within each set. Aleman et al. reported a decremental response of less than 5% at low frequencies (1 to 10 Hz) that increased at higher frequencies (20 to 50 Hz) in control foals.1 The decremental response was greater in affected foals at low frequencies, whereas an incremental response was recorded from all affected foals at higher frequencies (20 to 50 Hz).1 The results in this case were consistent with botulism (Fig. 1).1 Another differential for the abnormalities noted on the RNS was hypermagnesemia. The foal was confirmed to have a normal serum ionized magnesium concentration (0.51 mmol/L ref: 0.47–0.70 mmol/L).

Figure 1.

Repetitive nerve stimulation of the peroneal nerve. Control foal at 1 Hz (A), case at 1 Hz (B), control foal at 50 Hz (C), and case at 50 Hz (D). Notice low amplitude of CMAP (compound muscle action potential; B, D) in diseased foal compared to control foal, and sequential increment of CMAP at 50 Hz in diseased foal not present in control foal. Calibration at 5 mV and 1 mV per vertical division in recordings of control and diseased foal, respectively; and 2 ms per horizontal division.

The results of the fecal PCR testing for C. botulinum toxin gene sequences13 were available on day 4 of hospitalization and confirmed the presence of type A botulism spores, consistent with toxicoinfectious botulism. During the first 3 days of hospitalization, clinical signs progressed and included an inability to move from lateral recumbency or to stand, and progressive flaccidity of the tongue. Clinical improvement, including a very gradual return of motor function and strength, was noted on day 4 and continued throughout hospitalization, which spanned 30 days. By day 6, tongue tone had increased, allowing for the removal of the nasogastric tube and the foal to be fed from a bowl. By day 10 the foal could stand on her own with assistance to rise, and by day 15 she was able to right herself into sternal recumbency. On day 22, the foal was able to rise without assistance.

Additional therapy included provision of nutrition, maintenance of hydration, ensuring ability to urinate and defecate, and management of decubital ulcers. The foal was treated with potassium penicillin4 IV for the first 11 days and then switched to ceftiofur14 (5 mg/kg SQ q12h) for an additional 10 days. Repeat fecal PCR for botulism13 on day 14 was negative and antibiotic therapy was discontinued when the ultrasound examination showed normal umbilical structures at day 20. The foal was maintained on oral vitamin E7, omeprazole6, and selenium powder15 (0.3–0.6 mg total/day). Other treatments included a single dose of mineral oil9 (30 mL) administered through a nasogastric tube, and repeat soapy water enemas because of difficulty in defecating on days 2–6, lactase enzyme16 (3000 U PO q6h), artificial tears17 (1/4 inch strip OU q6h) until day 20, and silver sulfadiazine cream18 applied topically to the decubital ulcer.

Repeat analysis revealed that whole blood selenium concentrations were within normal limits (0.15 ppm ref: 0.05–0.5 ppm) on day 17 of hospitalization. Serial thoracic and abdominal ultrasound examinations were performed. These showed no abnormalities other than mild diffuse pleural roughening bilaterally, consistent with atelectasis secondary to recumbency.

At discharge (day 30), the foal was still weak and tired easily, but was able to stand unassisted, walk with a shortened stride, drink from a pan, and eat hay and pellets. Her head and neck position were normal. The owners were instructed to gradually increase the turn out time as her strength increased. In order to avoid re‐exposure to soil borne botulism spores, the clients were instructed to remove the surface soil from the filly's stall and paddock, and disinfect the area with 1:10 dilution of sodium hypochlorite. New dirt was brought in to fill the paddock, and rubber mats were placed in the stall in order to reduce exposure. Four months after discharge, the foal reportedly had returned to normal strength, with no persistent neuromuscular deficits or weakness.

This is the first documented case of survival following type A botulism in a horse. Botulism is an often fatal flaccid paralytic disorder caused by the neurotoxins produced by Clostridium botulinum.2 Clinically relevant forms of botulism in horses include toxicoinfectious, food‐borne, and wound botulism.2, 3 The toxicoinfectious form is more commonly seen in foals less than 6 months of age, and occurs when spores are ingested and germinate in the intestinal tract.4 Eight antigenically distinct neurotoxins have been identified: A, B, C (Ca, Cb), D, E, F, and G.5 In horses, botulism has been most commonly associated with serotypes B and C, followed by A and less commonly by D.2, 3, 4, 6, 7 Clinical signs associated with botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) include progressive muscular weakness, dysphagia, dysphonia, ptosis, decreased pupillary light reflex, decreased tongue, tail and anal tone, ileus and respiratory failure.2 The case presented here exhibited all of the primary clinical signs except a decreased pupillary light reflex and respiratory failure. The abnormally low head and neck carriage was reported in only 5% of adult horses with type B botulism and was not described as a clinical sign in foals with type B toxicoinfectious botulism.3, 4 Secondary complications can include aspiration pneumonia, decubital ulcers, and constipation.2, 3 Complications observed in this case included decubital ulcer over the tuber coxae and constipation which resolved with mineral oil. Decubitus was reportedly the most common complication in adult horses.3

Historically, botulism was diagnosed by identification of spores from wounds or GI contents after culture, which has a prolonged turnaround time, or measurement of preformed BoNT in serum, GI contents, or feed.2 The mouse bioassay has been regarded as the most reliable test for food‐borne botulism; however, it has low sensitivity for detection of toxins in equine serum because the horse has a high sensitivity to the effects of the toxins compared to mice.2 PCR and RNS have provided much needed antemortem diagnostic tests for toxicoinfectious botulism in horses, with a rapid turnaround time.1, 8 The key electrodiagnostic finding to support botulism was facilitation as demonstrated by the incremental responses in both amplitude and area under the curve at a high stimulus rate.1 This represents the recruitment of additional muscle fibers contributing to the response as the stimulus frequency increases.1 Facilitation has only been reported in the human literature in a few neuromuscular disorders: Lambert–Eaton syndrome, hypermagnesemia, and botulism.1, 9, 10 The low amplitude of CMAP in the diseased foal of this report (Fig. 1) was consistent with a previous report of RNS in foals with botulism.1

BoNT type A is often associated with more severe disease, longer recovery, and a higher case fatality rate than the other types of botulism in both humans and horses.3 Survival of type B botulism was most recently recorded as 48% in adult horses.7 The median hospitalization period for foals with type B botulism was 14 days if not ventilated or 22 days if ventilated.11 In the only study evaluating Type A botulism in horses, there were no confirmed survivors and clinical signs progressed rapidly and were more pronounced than those reported for other types.3 Of the positive Type A samples in that report, 3 were from isolated cases, all under 1 month of age, whereas the remainder of the 54 cases were from outbreaks.3 The latter horses were all greater than 11 months of age.3 In that study, 3/3 affected foals and 49/54 affected horses with type A botulism were confirmed to be dead at the time of sample submission. The remaining 5 horses were alive at the time of sample submission, but were lost to follow up with an unknown outcome, resulting in a mortality rate of somewhere between 90–100%.3 There have been no reports of survival of Type A cases in horses, and a previously confirmed foal case at the VMTH was ventilated for 18 days with no clinical improvement resulting in euthanasia.1 Given the age of onset of this foal, presence of type A spores in feces, and lack of obvious wounds, it is likely she was exposed to type A spores in the soil of the premises, although infection of the umbilicus cannot be ruled out. These owners did not have other foals <6 months of age, and none of the adult horses were affected.

Timely therapeutic management appears critical for the successful treatment of Type A botulism. Therapies used in this case included plasma containing antibodies against C. botulinum neurotoxins, antimicrobial therapy, and supportive care. It is recommended that the trivalent form of plasma containing antibodies against C. botulinum be used when there is a suspicion for Type A botulism or the case is from West of the Rocky Mountains in the United States.12

This case demonstrates the benefit of RNS as an adjunctive and early diagnostic modality, and the clinical utility of fecal PCR for detection of botulinum toxin genetic material in feces.1, 8 Both tests aid in confirmation of a clinical suspicion of botulism and have a rapid turnaround time for antemortem diagnosis, allowing veterinarians to direct therapy and advise on prognosis.

Because of lack of randomized control studies on the treatment of botulism in horses, the majority of decisions are based on experience or extrapolated from human literature. Controversy exists over the use of metronidazole in horses with botulism, with suspicion that it might affect the more susceptible GI anaerobes allowing clostridial overgrowth.13 However, this requires further study. In addition, caution is expressed over the use of potent clostridiacidal antibiotics in the treatment of human infant botulism, which can potentially increase toxin release and cause clinical deterioration.14 This area needs further research to elucidate the optimal antibiotic therapy of equine botulism. Previously, the most common reported antibiotics used in foals with botulism have included ceftiofur, trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole, and potassium penicillin.4 It should be noted that procaine penicillin, aminoglycosides, and tetracyclines should be avoided because of potentiation of neuromuscular blockade.15, 16

This report documents a case of survival of a foal with confirmed botulism type A infection. It suggests that type A botulism might require long‐term care and recovery as compared to other forms of botulism in foals. It also illustrates the use of fecal PCR and electrodiagnostic testing as practical and rapid means of diagnosis in horses, confirming appropriate therapy and management are being undertaken. Finally, head and neck weakness can be an early indicator of botulism.

Acknowledgments

Support was provided by the Center for Equine Health, with funds from the Oak Tree Racing Association, the State of California pari‐mutuel wagering fund, and contributions from private donors; the Henry Endowed Chair in Emergency Medicine and Critical Care, School of Veterinary Medicine; and the Clinical Neurophysiology Laboratory at the University of California, Davis.

Conflict of Interest Declaration: Authors disclose no conflict of interest.

Off‐label Antimicrobial Declaration: Ceftiofur used at 5 mg/kg which is higher than label dose, but commonly used in equine medicine.

Work performed at: The William R. Pritchard, Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital, University of California, Davis, CA 95616.

Footnotes

PlasVacc B‐C plasma, PlasVacc, Templeton, CA

LakeImm Bot Trivalent, Lake Immunogenics, Ontario, NY

LRS, Baxter, IL

K‐Pen, Vet tek Inc, MO

E‐Se, Merck Animal Health, NJ

Gastrogard, Merial Limited, Duluth, GA

Elevate W.S, Kentucky Performance Products, Versailles, KY

Mare's Match, Land O'Lakes, St Paul, MN

Mineral Oil, Vedco, Saint Joseph, MO

Diazepam, Hospira, IL

Anased, Lloyd, IA

Torbugesic, Zoetis, Fort Dodge, IA

The National Botulism Laboratory, The University of Pennsylvania

Naxcel, Pfizer, NY

Elevate, Kentucky Performance Products, Versailles, KY

Lactaid, McNeil Nutritionals, PA

Artificial Tears, Rugby, Duluth, GA

Thermazene, ThePharmaNetwork, NJ

References

- 1. Aleman M, Williams DC, Jorge NE, et al. Repetitive stimulation of the common peroneal nerve as a diagnostic aid for botulism in foals. J Vet Intern Med 2011;25:365–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Whitlock RH, McAdams S. Equine botulism. Clin Tech Equine Pract 2006;5:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johnson AL, McAdams SC, Whitlock RH. Type A botulism in horses in the United States: A review of the past ten years (1998–2008). J Vet Diagn Invest 2010;22:165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wilkins PA, Palmer JE. Botulism in foals less than 6 months of age: 30 cases (1989–2002). J Vet Intern Med 2003;17:702–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Comella CL, Pullman SL. Botulinum toxins in neurological disease. Muscle Nerve 2004;29:628–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chambron J, Martel JL, Doutre PM. Equine botulism in Senegal. 1st isolation of Clostridium botulinum type D. Rev Elev Med Vet Pays Trop 1971;24:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Johnson AL, McAdams‐Gallagher SC, Aceto H. Outcome of adult horses with botulism treated at a veterinary hospital: 92 cases (1989–2013). J Vet Intern Med 2015;29:311–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Johnson AL, Sweeney RW, McAdams SC, et al. Quantitative real‐time PCR for detection of the neurotoxin gene of Clostridium botulinum type B in equine and bovine samples. Vet J 2012;194:118–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dumitru D, Amato AA. Neuromuscular junction disorders In: Dumitru D, Amato AA, Zwarts MJ, eds. Electrodiagnostic Medicine, 2nd ed Philadelphia, PA: Hanley & Belfus Inc; 2002:1127–1228. [Google Scholar]

- 10. AAEM . Literature review of the usefulness of repetitive nerve stimulation and single fiber EMG in the electrodiagnostic evaluation of patients with suspected myasthenia gravis or Lambert‐ Eaton myasthenic syndrome. Muscle Nerve 2001;24:1239–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wilkins PA, Palmer JE. Mechanical ventilation in foals with botulism: 9 cases (1989–2002). J Vet Intern Med 2003;17:708–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smith GR, Milligan RA. Clostridium botulinum in soil on the site of the former metropolitan (Caledonian) cattle market, London. J Hyg Camb 1979;83:237–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sprayberry KA, Carlson GP. Review of equine botulism. Proc Am Assoc Equine Pract 1997;43:379–381. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Domingo RM, Haller JS, Gruenthal M. Infant botulism: Two recent cases and literature review. J Child Neurol 2008;23:1336–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Santos JI, Swensen P, Glasgow LA. Potentiation of Clostridium botulinum toxin by aminoglycoside antibiotics: Clinical and laboratory observations. Pediatrics 1981;68:50–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. L'Hommedieu C, Stough R, Brown L, et al. Potentiation of neuromuscular weakness in infant botulism by aminoglycosides. J Pediatr 1979;95:1065–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]