Abstract

Background

Bronchiectasis is a permanent and debilitating sequel to chronic or severe airway injury, however, diseases associated with this condition are poorly defined.

Objective

To evaluate results of diagnostic tests used to document bronchiectasis and to characterize underlying or concurrent disease processes.

Animals

Eighty‐six dogs that had bronchoscopy performed and a diagnosis of bronchiectasis.

Methods

Retrospective case series. Radiographs, computed tomography, and bronchoscopic findings were evaluated for features of bronchiectasis. Clinical diagnoses of pneumonia (aspiration, interstitial, foreign body, other), eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy (EBP), and inflammatory airway disease (IAD) were made based on results of history, physical examination, and diagnostic testing, including bronchoalveolar lavage fluid analysis and microbiology.

Results

Bronchiectasis was diagnosed in 14% of dogs (86/621) that had bronchoscopy performed. Dogs ranged in age from 0.5 to 14 years with duration of signs from 3 days to 10 years. Bronchiectasis was documented during bronchoscopy in 79/86 dogs (92%), thoracic radiology in 50/83 dogs (60%), and CT in 34/34 dogs (100%). Concurrent airway collapse was detected during bronchoscopy in 50/86 dogs (58%), and focal or multifocal mucus plugging of segmental or subsegmental bronchi was found in 41/86 dogs (48%). Final diagnoses included pneumonia (45/86 dogs, 52%), EBP (10/86 dogs, 12%) and IAD (31/86 dogs, 36%). Bacteria were isolated in 24/86 cases (28%), with Streptococcus spp, Pasteurella spp, enteric organisms, and Stenotrophomonas isolated most frequently.

Conclusions and Clinical Importance

Bronchiectasis can be anticipated in dogs with infectious or inflammatory respiratory disease. Advanced imaging and bronchoscopy are useful in making the diagnosis and identifying concurrent respiratory disease.

Keywords: Bacterial, Computed tomography, COPD, Endoscopy, Microbiology, Parenchymal disease, Pneumonia, Pulmonary infiltrates with eosinophilia, Radiology and diagnostic imaging, Respiratory tract

Abbreviations

- BAL

bronchoalveolar lavage

- BALF

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- CT

computed tomography

- EBP

eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy

- IAD

inflammatory airway disease

Bronchiectasis is a condition characterized by progressive and irreversible dilatation of the airways.1 Eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy (EBP) has been commonly associated with bronchiectasis,2, 3 along with other diseases in dogs such as chronic bronchitis and pneumonia.4, 5, 6 It is known to occur with primary ciliary dyskinesia7 as well as Mycoplasma pneumonia8 and pulmonary fibrosis.9 Bronchiectasis has also been reported in cats with infectious, inflammatory, or neoplastic disease,10, 11 although its contribution to clinical signs is unclear.

A comprehensive review of radiographically documented bronchiectasis in dogs revealed increased prevalence in Cocker spaniels and Miniature poodles, and older dogs of various breeds were most commonly affected.12 Progression of bronchiectasis and worsened distribution of disease over time was noted in approximately half of the dogs in which follow‐up radiographs were available.12 However, recognition of bronchiectasis is hampered by the poor sensitivity of radiographs,6 and in human medicine, high‐resolution computed tomography (CT) is the standard for diagnosis.13, 14 Computed tomography features of bronchiectasis in the dog have been described,6 and CT is increasingly used to investigate respiratory diseases in dogs and cats, although cost and the need for anesthesia preclude its use in some situations.

Computed tomography provides structural information on the airways and pulmonary parenchyma, however it does not allow documentation of cytologic and microbiologic characteristics that identify the underlying disease processes and guide treatment. In human medicine, sputum cultures are used most frequently to confirm bacterial involvement in bronchiectasis15, however, pharyngeal samples are not always accurate in dogs.16 Bronchoscopy is utilized in referral hospitals to characterize respiratory disease processes and provides valuable visual information to refine disease characteristics. The purpose of this study was to evaluate results of diagnostic tests used to document bronchiectasis, including bronchoscopy, CT, and radiography. We also sought to define underlying or concurrent disease processes in affected dogs.

Materials and Methods

Medical records, imaging studies, and bronchoscopy reports from dogs presented to the UC Davis William R. Pritchard Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital from 2003 through 2014 were searched for identification of bronchiectasis. Inclusion criteria included bronchoscopic characterization of airway dilatation with or without suppuration or radiographic description of lack of normal airway tapering with or without pulmonary infiltrates. Computed tomographic findings consistent with bronchiectasis12 including a bronchoarterial ratio >2.0 and lack of airway tapering were also considered diagnostic of disease. Cases with histologic, radiographic, or CT identification of bronchiectasis that did not have bronchoscopy performed were not included in the analysis. All bronchoscopic reports and available images or videos from procedures were reviewed by a board certified internist (LRJ) to confirm recognition of bronchiectasis. Radiographs (n = 83) and CT images (n = 34) were reviewed by a board certified radiologist (EGJ) for features consistent with bronchiectasis. The number of affected dogs was compared to the total number of dogs in which bronchoscopy was performed during the same time period.

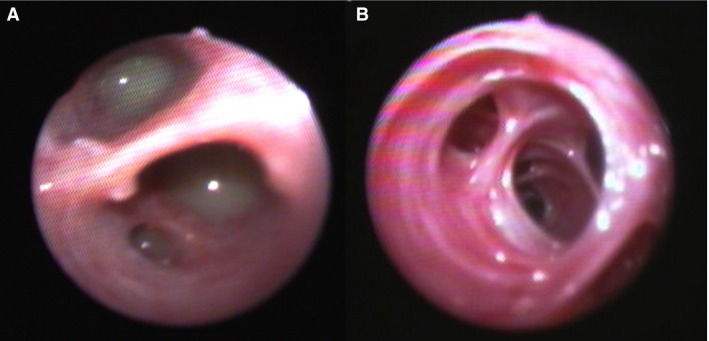

Radiographs were usually performed the day before bronchoscopy and no more than 1 week before the procedure. Laryngoscopy and assessment of upper airway anatomy preceded anesthesia for CT or bronchoscopy in most cases. Laryngeal paresis or paralysis was documented by failure of the cartilages to abduct during appropriate respiratory effort at induction of anesthesia or after stimulation of respiratory movements with doxapram hydrochloride if required. Computed tomography was performed immediately before bronchoscopy and the endoscopist was aware of imaging results at the time of the procedure. Bronchoscopy was performed by one of the authors (LRJ) or a clinician trained by the author. Hyperemia, bronchiectasis with or without mucus plugging of airways (Fig 1) and airway collapse were recorded.

Figure 1.

Bronchoscopic images from 2 dogs with bronchiectasis with (A) and without (B) suppuration.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed at one or more sites by instillation and aspiration of warm, sterile saline through the biopsy channel of the endoscope. An aliquot of BALF was submitted for microbial culture of aerobic bacterial species and Mycoplasma spp. in all cases. In select cases, anaerobic bacterial culture was also performed. Bacterial growth was assessed in a semiquantitative fashion and reported as 1+, 2+, 3+, or 4+, designating the number of quadrants with bacterial growth. BAL fluid from 6 healthy dogs consisted of 200 cells/μL, consisting mostly macrophages, with less than 8% eosinophils, neutrophils, or lymphocytes.17 Alterations in percentage of inflammatory cells can assist in characterization of respiratory disease, and BAL samples were analyzed here by total and differential leukocyte counts (based on a count of 200 cells). Cytologic assessment was made by board certified clinical pathologists to document the presence of oropharyngeal contaminants, intracellular bacteria, fungal elements, neoplasia, and foreign material.

Owner and referring veterinarian histories, medical records, and radiographic findings along with VMTH records were comprehensively reviewed by one of the authors (LRJ). Information abstracted from the VMTH medical record included age, weight, breed, and sex. Physical examination findings, results of imaging, bronchoscopy, BALF cytology, and microbiology along with response to treatment (where available) were used to identify previous respiratory diagnoses and the most likely underlying or concurrent disease processes associated with bronchiectasis in each dog.

Inflammatory airway disease was diagnosed in systemically healthy dogs that lacked radiographic evidence of pneumonia, had BALF that contained >8% neutrophils or lymphocytes, or a mixed inflammatory cytologic pattern that lacked intracellular bacteria, and had no growth of potential pathogens on microbial culture. Eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy was diagnosed in dogs that were negative for heartworm, negative for lungworm or failed fenbendazole trial, demonstrated bronchoscopic findings of yellow mucus, airway collapse, or hyperemia,2 and had a high percentage of BAL eosinophils. Steroid responsive was also documented. Final diagnoses of pneumonia included infectious, aspiration, foreign body, or interstitial pneumonia. When any number of neutrophils in BALF contained intracellular bacteria or culture revealed growth of potentially pathogenic bacteria, the sample was categorized as septic and infectious pneumonia was diagnosed. Historical reports of predisposing risk factors along with radiographic findings consistent with aspiration18 were used in characterizing pneumonia related to aspiration; positive bacterial growth from BALF was not a criterion for this diagnosis. Interstitial pneumonia was diagnosed by characteristic findings on CT or histopathology. A diagnosis of foreign body pneumonia was assigned to dogs that had foreign material removed from the lung.

Statistics

Age, duration of signs, and weight were evaluated for compatibility with a normal distribution using the D'Agostino & Pearson omnibus normality test. Data were not normally distributed and are presented as median and range. The exact Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare distributions of continuous variables between groups; when significant, posthoc exact Mann–Whitney tests with a Bonferroni–Holm multiple comparison adjustment were used. The distribution of affected breeds was compared to the breed distribution of the hospital population using an exact chi‐square test of homogeneity because many expected cell frequencies were less than five. Breeds overrepresented in the affected group were identified based on significantly contributing to the overall chi‐square test statistic; results are presented as observed:expected ratios. The exact chi‐square test of homogeneity was used to assess difference in the detection of airway collapse, hyperemia, mucus plugging, and radiographically or bronchoscopically visible bronchiectasis among disease groups; posthoc pairwise comparisons were performed with a Bonferroni–Holm multiple comparison adjustment. Statistics were performed using commercially available software.1 Statistical significance was defined as P < .05.

Results

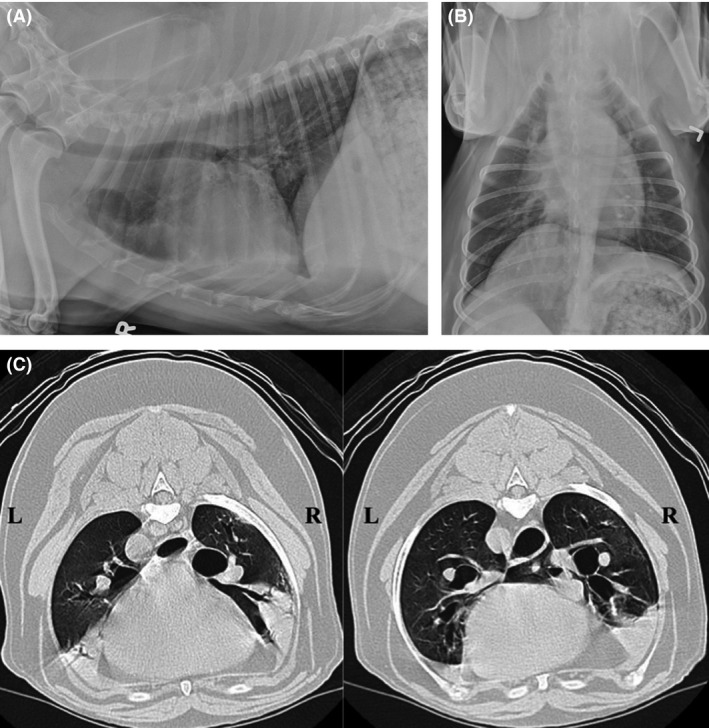

From April 2003 through April 2014, bronchiectasis was documented in 86/621 dogs (14%) that had bronchoscopy performed. Bronchiectasis was diagnosed bronchoscopically in 79/86 (92%) dogs, by thoracic radiology in 50/83 dogs (60%) and by CT in 34/34 dogs (100%). Diagnosis of bronchiectasis was concordant by all 3 methods in 15/34 dogs (44%), however, radiographs did not show bronchiectasis in 13/34 cases (38%). (Fig 2) Computed tomography revealed that bronchiectasis was diffuse in 19/34 dogs, multifocal in 13/34 dogs, or focal in 2/34 dogs. Bronchoscopy revealed airway hyperemia in 58/86 dogs (67%), focal or multifocal mucus plugging of segmental or subsegmental bronchi in 41/86 dogs (48%), and concurrent airway collapse in 50/86 dogs (58%).

Figure 2.

(A and B) Right lateral and dorsoventral radiographs from a dog subsequently diagnosed with diffuse bronchiectasis based on CT and bronchoscopy. Thoracic radiographs reveal mild bronchial wall mineralization, heterotopic bone formation, and mild interstitial pulmonary densities compatible with normal age‐related changes. Bronchiectasis is not identified. (C) Computed tomographic images from the dog in 2A and B. Heavy alveolar infiltrates are present in the ventral aspects of the right cranial, and right middle lung lobes, as well as the caudal subsegment of the left cranial lung lobe. In these images, bronchi to the right cranial and right middle lobes are moderately dilated, and do not taper appropriately.

Final diagnoses in dogs with bronchiectasis included pneumonia in 45/86 dogs (52%), EBP in 10/86 dogs (12%) and IAD in 31/86 dogs (36%). Differential cytologic findings in these groups of dogs are presented in Table 1. Multiple lung lobes were sampled in 85/86 dogs and BAL results from the specific site of bronchiectasis were reported in 57/86 (66%) dogs. In the remaining 29 dogs, BAL results were averaged when similar values were obtained or values from the more cellular sample were reported. A low cell count (<300 cells/μL) did not result in exclusion from analysis when all other clinical data were available.

Table 1.

Cell counts and differential cytology results in dogs with pneumonia, eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy and inflammatory airway disease. Table entries represent median values with range (in parentheses)

| Pneumonia | Eosinophilic Bronchopneumopathy | Inflammatory Airway Disease | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BAL total cell count/μL | 1310 (120–39,440) | 1300 (340–14,040) | 670 (240–6200) |

| Neutrophils (%) | 52 (3–99) | 42 (2–70) | 24 (1–91) |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 6 (0–42) | 3 (0–9) | 11 (0–52) |

| Macrophages (%) | 36 (1–90) | 6 (1–44) | 61 (2–85) |

| Eosinophils (%) | 3 (1–15) | 44 (27–70) | 3 (0–16) |

Affected dogs ranged in age from 0.5 to 14 years (median 10 years) with 1/86 dogs < 6 months, 16/86 dogs (19%) 1–5 years of age, 37/86 dogs (43%) 5.1–10 years of age, and 32/86 dogs (37%) over 10 years of age. Weights of affected dogs ranged from 2 to 49.2 kg with a median of 17 kg. Small dogs (<5 kg) comprised 11/84 (13%) dogs, 27/84 dogs (32%) were 5–15 kg, 35/84 dogs (42%) were 15.1–35 kg, and 11/84 dogs (13%) were >35 kg. Weight was not recorded in 2 dogs. Cough was the primary complaint in 81/86 (94%) dogs, while respiratory difficulty or tachypnea was reported in 5/86 (6%). Duration of cough ranged from 3 days to 10 years, with a median of 6 months.

Demographics for dogs in the various disease groups associated with bronchiectasis are presented in Table 2. The distribution of ages of dogs with specific diseases differed significantly among groups, although none of the pairwise age differences between groups were significant after multiple comparison adjustment. Body weight of dogs with specific diseases differed significantly among groups (P = .001); weight of dogs with pneumonia was significantly greater than that of dogs with IAD (P = .0003). Duration of cough did not differ among groups (P = .091), with median values of 4, 6, and 8.5 months in dogs with pneumonia, EBP, and IAD, respectively.

Table 2.

Demographic data for dogs with bronchiectasis. Table entries represent median values with ranges and P values represent comparisons among disease groups. Significant (P < .05) pairwise group differences test using Mann–Whitney tests and a Bonferroni–Holm posthoc multiple comparison adjustment after a significant Kruskal–Wallis are represented by*

| Pneumonia | Eosinophilic Bronchopneumopathy | Inflammatory airway Disease | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 9.2 (0.5–13.1) | 9.0 (3.0–12.0) | 10.0 (1.5 – 14.0) | .044 |

| Weight (kg) | 25.6 (3.6–49.2)* | 16.0 (4.6–38.0) | 10.4 (2.0–47.7)* | .001* |

| Duration of cough (months) | 4.0 (0.1–48) | 6.0 (2.5–60) | 8.5 (1.0–120) | .091 |

| M/F | 21/24 | 4/6 | 10/18 | .088 |

There was a significant difference in the distribution of breeds between dogs affected with bronchiectasis and other dogs seen at the hospital (P = .0002). Dog breeds affected more than twice included 6 Labrador retrievers, 5 Cocker spaniels, 4 Golden retrievers, and 4 Standard Poodles, and 3 each of the Beagle, Chihuahua, Pug, and Malamute. Compared to the hospital population, the following breeds could be overrepresented, although some were represented by only one case: Airedale (1), Malamute (3), American Eskimo (2), Beagle (3), Belgian Tervuren (1), Cocker Spaniel (5), Rough‐coated Collie (1), Long‐haired miniature Dachshund (1), Flat‐coated retriever (1), Miniature Pinscher (2), Patterdale terrier (1), Standard poodle (5), Shetland Sheepdog (2), Soft‐coated Wheaten (1), and West Highland White terrier (2). (Table 3).

Table 3.

Breeds that were significantly more likely to demonstrate bronchiectasis at the UCD VMTH. The observed:expected (O:E) ratio provides a comparison of the number of affected dogs for a particular breed in relation to the expected number of cases for that breed based on the distribution of all breeds seen at the VMTH during the time frame of this study. P value corresponds to the null hypothesis that the O:E ratio = 1 and is calculated from the breed's cell‐specific chi‐square contribution for bronchiectasis diagnosis to the overall chi‐square test statistic for all breeds

| Breed | Number Affected | Observed:Expected Ratio | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Airedale terrier | 1 | 5.8 | .046 |

| Alaskan Malamute | 3 | 15.1 | .0001 |

| American Eskimo dog | 2 | 10.2 | .0014 |

| Beagle | 3 | 3.3 | .029 |

| Belgian Tervuren | 1 | 19.7 | <.0001 |

| Cocker Spaniel | 5 | 4.7 | .0001 |

| Rough Collie | 1 | 5.9 | .043 |

| Long haired mini‐Dachshund | 1 | 10.9 | .0027 |

| Flat coated retriever | 1 | 7.9 | .014 |

| Miniature Pinscher | 2 | 3.9 | .036 |

| Patterdale terrier | 1 | 90.7 | <.0001 |

| Standard Poodle | 5 | 7.7 | <.0001 |

| Shetland Sheepdog | 2 | 3.8 | .043 |

| Soft coated Wheaten terrier | 1 | 7.0 | .024 |

| West Highland white terrier | 2 | 4.2 | .027 |

Pneumonia concurrent with bronchiectasis was recognized in 45/86 (52%) dogs. Aspiration pneumonia was suspected in 25/45 dogs, with laryngeal paralysis in 7 of these dogs and elongated soft palate in 3 of these dogs as potential contributing factors. Interstitial pneumonia was diagnosed in 6 dogs based on CT (n = 4) and histopathology (n = 4), with inhalational injury suspected in 3/6 dogs and interstitial fibrosis in 2/6 dogs (both West Highland white terriers). Previous foreign body impaction was documented in 3/45 dogs with pneumonia. In the remaining 11 dogs, no specific underlying trigger or concurrent cause for pneumonia was identified, with infection documented in 9 of these cases.

Active infection was documented at the time of diagnosis with bronchiectasis in 22/45 dogs (49%) with pneumonia including 12/25 with aspiration, 1/6 with interstitial pneumonia, 0/3 with foreign body pneumonia, and 9/11 with an unrecognized cause of pneumonia. The most commonly isolated bacterium (n = 7) was Streptococcus, with Streptococcus canis in 4 dogs and Streptococcus viridans, Streptococcus equi spp. zooepidemicus, and an untyped Streptococcus in 1 dog each. Enteric organisms were isolated in 5 cases (E. coli in 4 dogs and Klebsiella pneumonia in 1 dog). Nonenteric bacteria were also isolated including Pasteurella spp. in 4 dogs, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in 3 dogs, and Bordetella bronchiseptica in 2 dogs. Other isolates included Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Actinomyces spp., and Capnocytophagia cynodegmi in 1 dog each. More than one species of bacteria was isolated in 5/21 cases. Concurrent with aerobic bacterial isolation, Mycoplasma culture was positive in 3/21 cases, an anaerobe (Fusobacterium nucleatum) was isolated in 1/21 cases, and fungal culture was positive for Aspergillus terreus in 1/1 dog tested.

Computed tomography was performed in 27 of 45 dogs with pneumonia and revealed findings consistent with bronchiectasis in all. Distribution of bronchiectasis was diffuse in 13, multifocal in 12, and focal in 2 dogs. Thoracic radiography demonstrated bronchiectasis in 19/44 dogs (43%) with pneumonia. Bronchoscopic evidence of airway dilatation was reported in 41/45 dogs (91%), and concurrent airway collapse was diagnosed in 19/45 dogs (42%).

Eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy was diagnosed in 10/86 (12%) dogs. Mean eosinophil percentage was 43.5 ± 13.2%. Two of these 10 dogs had concurrent airway infection, with isolation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Pasteurella canis in one dog each. No Mycoplasma spp. or anaerobes were isolated. Computed tomography revealed diffuse bronchiectasis in 4/4 dogs evaluated, and radiographs demonstrated airway dilatation in 8/10 dogs. Bronchoscopic evidence of bronchiectasis was noted in 9/10 dogs, and concurrent airway collapse was documented in 8/10 dogs.

Inflammatory airway disease was the final diagnosis in 31/86 dogs (36%) with concurrent airway collapse in 23/31 dogs (74%). Computed tomography revealed diffuse bronchiectasis in 2/3 dogs and multifocal disease in 1/3 dogs. Radiographic findings consistent with bronchiectasis were reported in 16/30 dogs (53%). Bronchoscopically, airway dilatation was reported in 29/31 dogs.

Detection of bronchiectasis by radiography or bronchoscopy did not differ significantly among disease groups (P = .33 and P = 1.0, respectively). However, bronchoscopic evidence of airway collapse was significantly different among disease groups (P = .0065), being present in a significantly lower percentage of dogs with pneumonia (42%) than in those with EBP (80%) or IAD (74%), P value = .0094. Mucus plugging of airways differed significantly among disease groups (P = .036), but no pairwise differences were significant after multiple comparison adjustment. (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison among disease groups for the prevalence rates of radiographic and bronchoscopic findings. Table entries represent the number and percentage of affected dogs in each disease group. Significant (P < .05) pairwise group differences using a Bonferroni–Holm posthoc multiple comparison adjustment after a significant chi‐square test are represented by columns sharing*

| Pneumonia | Eosinophilic Bronchopneumopathy | Inflammatory Airway Disease | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiographically visible bronchiectasis | 26/43 (60%) | 8/10 (80%) | 16/30 (53%) | .33 |

| Bronchoscopic evidence of airway dilatation | 41/45 (91%) | 9/10 (90%) | 29/31 (94%) | 1.0 |

| Airway collapse on bronchoscopy | 19/45 (42%)* | 8/10 (80%) | 23/31 (74%)* | .0065* |

| Moderate to severe airway hyperemia | 33/45 (73%) | 5/10 (50%) | 20/31 (65%) | .35 |

| Mucus plugging of airways | 26/45 (58%) | 6/10 (60%) | 9/31 (29%) | .036 |

Discussion

This study identified bronchiectasis with radiographs, computed tomography, bronchoscopy, or a combination of tests in 86/621 dogs (14%) that had bronchoscopy performed over an 11 year period. Concurrent diseases found in dogs with bronchiectasis included various types of pneumonia and inflammatory airway disease associated with eosinophilic, neutrophilic, or lymphocytic infiltration. Although bronchiectasis is reportedly a rare condition when affected cases are compared to the total hospital population,12 results obtained here indicate that it is a relatively common finding in dogs evaluated specifically for respiratory disease.

In human medicine, bronchiectasis develops in adults 10–20 years after the pulmonary insult,15 although the onset varies and children as young as 8 months of age can also be affected.19 Duration of signs in dogs examined here was similar to that reported in a previous study,12 and in 23% of dogs, clinical signs had been present for <2 months. This suggests that ongoing lung disease with irreversible damage is occurring in the absence of owner‐recognized clinical signs or of physical examination abnormalities that could be detected during a routine veterinary visit, a situation similar to that found in children.19 Recognition of the disorder is made more difficult by the finding that radiographs detected less than 2/3 of cases, similar to an earlier investigation.6

In this study, bronchoscopy was highly useful in documenting bronchiectasis, with identification of 92% of affected dogs. In human medicine, bronchoscopy is used only when a foreign body is suspected, when aspiration is presumed, or when atypical bacterial or mycobacterial infection is considered likely.13, 15, 20 However, in certain populations, bronchoscopy is more sensitive for detecting airway pathology than high‐resolution computed tomography and both tests are advised for evaluation of children with wet cough.21 In this study, 8% of bronchoscopy procedures did not document bronchiectasis possibly because of the inability of the endoscope to access more peripheral airways or because of mucus plugging that obscured visualization. Clearly performing both CT and bronchoscopy is preferred for complete evaluation of the lungs, but this study confirms the utility of bronchoscopy in identifying airway dilatation as well as additional findings within the airways.

In dogs with bronchiectasis examined here, pneumonia was the most common disease process, with most dogs suffering from probable aspiration pneumonia. Development of bronchiectasis in aspiration pneumonia can be readily explained, particularly if chronic aspiration is considered likely, as in dogs with laryngeal paralysis or upper airway obstruction. Acid injury and bacterial infection both contribute to airway injury and inflammation which could initiate the processes leading to degradation of the support structures of the lung and airway dilatation.22, 23, 24, 25 Silent aspiration is a common problem in human medicine and might also occur in dogs, as clinical signs in animals could readily go unrecognized. Vomiting, regurgitation, and swallowing disorders are common in dogs,26 but the occurrence of bronchiectasis in that population of dogs is unknown. Further studies are needed as up to 2/3 of pediatric patients with chronic aspiration injury develop bronchiectasis.19

Regardless of the underlying etiology, the pathophysiologic consequences of bronchiectasis are similar. Epithelial cell injury and loss of normal mucociliary transport result in trapping of potential pathogens and environmental particulate matter in the lower airways that can perpetuate airway injury and further infection. Bacterial infection plays a central role in human cases of bronchiectasis,14, 24 however, only 24/86 dogs (28%) had positive bacterial cultures here, despite this increased risk for infection. Previous use of antibiotics could explain the low number of infections documented, however, this was not examined here, and a previous study showed that bacteria could be isolated from many dogs despite antimicrobial administration.27 It has been reported that recognition of bacteria in the lower airways can require culture‐independent mechanisms for detection.25, 28 We have previously reported culture‐based isolation of bacteria from 89/105 dogs with lower respiratory tract infection,27 however, PCR‐based techniques can identify substantially more bacterial species.24, 28, 29 Further investigations are needed to confirm or deny a role for specific bacteria in dogs with bronchiectasis.

Bacterial isolates from some dogs with bronchiectasis were included in a previous study of lower respiratory tract infection in dogs,27 however, it is interesting to note the number of opportunistic pathogens associated with infection in dogs with bronchiectasis examined here, particularly Stenotrophomonas, Pseudomonas, and Capnocytophaga. It was not possible to estimate the duration of active infection in dogs with bacteria isolated and it is unknown whether bacteria were a cause or a result of bronchiectasis. Isolation of Pseudomonas spp, Haemophilus, and Mycobacterium avium is common in human medicine,15, 28 and Stenotrophomonas has been increasingly recognized in both cystic fibrosis and noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis.30 Infection with Pseudomonas spp. is often particularly difficult to eradicate from the lung and contributes to further airway injury through induction of chronic inflammation.15, 24

In a previous study of dogs with radiographically identified bronchiectasis, neutrophilic, and eosinophilic inflammation was common, along with positive bacterial cultures,12 however, specific disease categories were not defined. Our finding of bronchiectasis in inflammatory airway diseases of dogs should not be surprising given that the pathophysiology of bronchiectasis is thought to be related to enzymatic products of inflammatory cells and aberrant cytokine responses,23, 31 although the relatively rare occurrence of bronchiectasis (2%) in the inflammatory condition of human asthma raises questions about the exact mechanisms of development.14 Response of the canine lung to chronic inflammation could be more similar to that found in the cat, where 17% of cases (4 of 23 cats) with bronchitis/asthma had bronchiectasis documented on bronchoscopy.11 It is possible that IAD in the dog more closely resembles the human condition of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, a composite of emphysema and chronic bronchitis, in which up to 50% of patients can demonstrate bronchiectasis.32, 33

The relationship between bronchiectasis and airway collapse in veterinary medicine is unclear. A previous study reported bronchiectasis in 30% of dogs with tracheal collapse.34 However, both conditions were diagnosed solely by review of thoracic radiography, which likely overdiagnosed tracheal collapse and underdiagnosed bronchiectasis. Bronchomalacia was documented in 11 of 33 children with bronchiectasis.35 In dogs with radiographically evident bronchiectasis, fluoroscopic evidence of airway collapse was found in 9/10 dogs examined and was visualized bronchoscopically in 4/6 dogs.12 However, in a report on bronchomalacia in dogs, <10% of dogs had bronchoscopic evidence of bronchiectasis and an equivalent number of dogs without bronchomalacia also had bronchiectasis.36 Fluoroscopy was not evaluated in the present study, although bronchoscopy identified a relatively high percentage of airway collapse (58%), with a higher prevalence in dogs with inflammatory airway disease than in dogs with pneumonia. It has been suggested that airway inflammation could potentiate airway collapse. Given that bronchiectasis is associated with loss of structural support within the airways, increased collapsibility might be anticipated, as was demonstrated in one study of human patients.37 However, some cases of bronchiectasis demonstrated a rigid appearance of the airways rather than collapse. (Fig 1B) Whether these are cases of traction bronchiectasis or cases that lack a strong inflammatory component that could enhance the likelihood of collapse requires further study.

Multiple breeds were affected by bronchiectasis and this study confirms the susceptibility of Cocker spaniels (n = 5) noted previously.11 Interestingly, Malamutes (n = 3) were possibly overrepresented, but had bronchiectasis in association with inflammatory rather than with eosinophilic airway disease, which has been previously reported.2 In addition, several other breeds were overrepresented here in relation to the hospital population. Rare breeds such as the Airedale and Patterdale terrier were possibly overrepresented compared to the hospital population despite diagnosis of bronchiectasis in only 1 dog of each breed. This raises the question of genetic propensity to development of bronchiectasis in certain breeds. However, these findings (and those of Table 4) must be interpreted with caution in light of the small numbers of dogs diagnosed with bronchiectasis within each of the breeds.

Multiple clinicians were involved in bronchoscopic reports and potential inconsistency in documentation represents one limitation of the study. Also, bronchiectasis can develop with age in healthy dogs, which could result in over diagnosis of the disorder in older dogs.38 Other limitations arise from the reliance on owner history for an accurate depiction of events. In some dogs, a long‐term history of respiratory disease was reported, and it was not possible to identify the precise onset of clinical disease. Alternately, while some owners described an acute onset of signs, it is possible that earlier clinical signs might have gone unrecognized. Finally, BAL samples were not always obtained from the region affected by bronchiectasis, and the impact of antibiotic or steroid administration on cell counts and differential cytology was not considered in this study. Although BALF analysis was only one criterion used in defining the final respiratory diagnosis, this represents an important consideration when interpreting results of this study.

The prevalence of bronchiectasis in human medicine has drastically decreased in recent years with more appropriate antibiotic usage but it remains a significant problem in developing countries. This study suggests that bronchiectasis is relatively common in dogs that require specialized diagnostics such as CT or bronchoscopy for identification of disease, as indicated by detection of bronchiectasis in 14% of dogs that had bronchoscopy performed. Given the presumed irreversibility of bronchiectasis and the need for long‐term management of airway secretions and infection, enhanced understanding of disease associations and early recognition of bronchiectasis should allow better patient care. Therefore, dogs with chronic signs associated with pneumonia, EBP, or IAD should be considered at risk for bronchiectasis, and advanced imaging followed by bronchoscopy should be recommended. While both computed tomography and bronchoscopy can provide structural information, bronchoscopy has the advantage of identifying airway collapse as well as allowing collection of airway samples to direct treatment.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: Supported in part by the Bailey Wrigley Fund, University of California Davis.

Conflict of Interest Declaration: L.R. Johnson is a member of the Feline Advisory Board and receives speaker honoraria.

Off‐label Antimicrobial Declaration: Authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobials.

This study was completed at the University of California School of Veterinary Medicine, Davis CA.

Presented in part at the 25th Annual Congress of the European College of Veterinary Internal Medicine – Companion Animal, Lisbon Portugal, September 2015.

Footnote

GraphPad Prism Version 5, San Diego, CA and Stata/IC 1.31, StatCorp LP, College Station, TX.

References

- 1. Chan ED, Iseman MD. Bronchiectasis In: Broaddus VC, Mason RC, Ernst JD, King TE, Lazarus SC, Murray JF, Nadel JA, Slutsky A, Gotway M, eds. Murray and Nadel's Textbook of Respiratory Medicine, 6th edition. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:853–876. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Clercx C, Peeters D, Snaps F, et al. Eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2000;14:282–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mesquita L, Lam R, Lamb CR, McConnell JF. Computed tomographic findings in 15 dogs with eosinophilic bronchopneumopathy. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2015;56:33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Padrid PA, Hornof WJ, Kurpershoek CJ, Cross CE. Canine chronic bronchitis. A pathophysiologic evaluation of 18 cases. J Vet Intern Med 1990;4:172–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Szabo D, Sutherland‐Smith J, Barton B, et al. Accuracy of a computed tomography bronchial wall thickness to pulmonary artery diameter ratio for assessing bronchial wall thickening in dogs. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2015;56:264–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cannon MS, Johnson LR, Pesavento PA, et al. Quantitative and qualitative computed tomographic characteristics of bronchiectasis in 12 dogs. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2013;54:351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beck JA, Ard M, Howerth EW. Pathology in practice. Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) with associated bronchopneumonia, bronchiectasis, and hydrocephalus in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2014;244:421–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kirchner BK, Port CD, Magoc TJ, et al. Spontaneous bronchopneumonia in laboratory dogs infected with untyped Mycoplasma spp. Lab Anim Sci 1990;40:625–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heikkilä HP, Lappalainen AK, Day MJ, et al. Clinical, bronchoscopic, histopathologic, diagnostic imaging, and arterial oxygenation findings in West Highland White Terriers with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Vet Intern Med 2011;25:433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Norris CR, Samii VF. Clinical, radiographic, and pathologic features of bronchiectasis in cats: 12 cases (1987–1999). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2000;216:530–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Johnson LR, Vernau W. Bronchoscopic findings in 48 cats with spontaneous lower respiratory tract disease (2002–2009). J Vet Intern Med 2011;25:236–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hawkins EC, Basseches J, Berry CR, et al. Demographic, clinical, and radiographic features of bronchiectasis in dogs: 316 cases (1988–2000). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2003;223:1628–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pasteur MC, Bilton D, Hill AT; British Thoracic Society Bronchiectasis non‐CF Guideline Group . British thoracic society guideline for non‐CF bronchiectasis. Thorax 2010;65(Suppl 1):i1–i58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brower KS, Del Vecchio MT, Aronoff SC. The etiologies of non‐CF bronchiectasis in childhood: A systematic review of 989 subjects. BMC Pediatr 2014;14:299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nicotra MB, Rivera M, Dale AM, et al. Clinical, pathophysiologic, and microbiologic characterization of bronchiectasis in an aging cohort. Chest 1995;108:955–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sumner CM, Rozanski EA, Sharp CR, Shaw SP. The use of deep oral swabs as a surrogate for transoral tracheal wash to obtain bacterial cultures in dogs with pneumonia. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2011;21:515–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hawkins EC, DeNicola DB, Kuehn NF. Bronchoalveolar lavage in the evaluation of pulmonary disease in the dog and cat. State of the art. J Vet Intern Med 1990;4:267–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kogan DA, Johnson LR, Sturges BK, et al. Etiology and clinical outcome in dogs with aspiration pneumonia: 88 cases (2004–2006). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2008;233:1748–1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Piccione JC, McPhail GL, Fenchel MC, et al. Bronchiectasis in chronic pulmonary aspiration: Risk factors and clinical implications. Pediatr Pulmonol 2012;47:447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Park JH, Kim SJ, Lee AR, et al. Diagnostic yield of bronchial washing fluid analysis for hemoptysis in patients with bronchiectasis. Yonsei Med J 2014;55:739–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Douros K, Alexopoulou E, Nicopoulou A, et al. Bronchoscopic and high‐resolution CT scan findings in children with chronic wet cough. Chest 2011;140:317–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stockley RA, Hill SL, Morrison HM, Starkie CM. Elastolytic activity of sputum and its relation to purulence and to lung function in patients with bronchiectasis. Thorax 1984;39:408–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lapa e Silva JR, Guerreiro D, Noble B, et al. Immunopathology of experimental bronchiectasis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1989;1:297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rogers GB, Zain NM, Bruce KD, et al. A novel microbiota stratification system predicts future exacerbations in bronchiectasis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014;11:496–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Martin C, Burgel PR, Lepage P, et al. Host‐microbe interactions in distal airways: Relevance to chronic airway diseases. Eur Respir Rev 2015;24:78–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bonadio CM, Marks SL, Pollard RE, Kass PH. Causes of canine dysphagia in a veterinary teaching hospital, abstract. Presented at the Annual Forum of the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine, Indianapolis, IN. 2015.

- 27. Johnson LR, Queen EV, Vernau W, et al. Microbiologic and cytologic assessment of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from dogs with lower respiratory tract infection: 105 cases (2001–2011). J Vet Intern Med 2013;27:259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yang DH, Zhang YY, Du PC, et al. Rapid identification of bacterial species associated with bronchiectasis via metagenomic approach. Biomed Environ Sci 2014;27:898–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Aydemir O, Aydemir Y, Ozdemir M. The role of multiplex PCR test in identification of bacterial pathogens in lower respiratory tract infections. Pak J Med Sci 2014;30:1011–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Green H, Jones AM. The microbiome and emerging pathogens in cystic fibrosis and non‐cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2015;36:225–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fuschillo S, De Felice A, Balzano G. Mucosal inflammation in idiopathic bronchiectasis: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Eur Respir J 2008;31:396–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Patel IS, Vlahos I, Wilkinson TMA, et al. Bronchiectasis, exacerbation indices, and inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;170:400–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gatheral T, Kumar N, Sansom B, et al. COPD‐related bronchiectasis; independent impact on disease course and outcomes. COPD 2014;11:605–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Marolf A, Blaik M, Specht A. A retrospective study of the relationship between tracheal collapse and bronchiectasis in dogs. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 2007;48:199–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chang AB, Boyce NC, Masters IB, et al. Bronchoscopic findings in children with non‐cystic fibrosis chronic suppurative lung disease. Thorax 2002;57:935–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Johnson LR, Pollard RE. Tracheal collapse and bronchomalacia in dogs: 58 cases (7/2001–1/2008). J Vet Intern Med 2010;24:298–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nishino M, Siewert B, Roberts DH, et al. Excessive collapsibility of bronchi in bronchiectasis: Evaluation on volumetric expiratory high‐resolution CT. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2006;30:474–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mercier E, Bolognin M, Hoffmann AC, et al. Influence of age on bronchoscopic findings in healthy beagle dogs. Vet J 2011;187:225–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]