Abstract

Background

Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (CKCS) are predisposed to myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD). Studies have indicated a strong genetic background.

Objective

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of a breeding scheme involving auscultation and echocardiography.

Animals

In the Danish Kennel Club mandatory breeding scheme, 997 purebred CKCS were examined during the period 2002–2011. Each dog was evaluated 1–4 times with a total of 1,380 examinations.

Methods

Auscultation and echocardiography were performed to evaluate mitral regurgitation murmur severity and degree of mitral valve prolapse (MVP). The odds of having mitral regurgitation murmur or MVP > grade 1 in 2010–2011 compared to 2002–2003 were estimated using logistic regression analysis including age and sex as covariates. Odds were estimated for dogs that were products of the breeding scheme (defined as dogs with both parents approved by the breeding scheme before breeding) and non‐products of the breeding scheme (defined as dogs with at least 1 parent with unknown cardiac status).

Results

In 2010–2011, the odds of having mitral regurgitation murmur were 0.27 if dogs were a product of the breeding scheme compared with dogs in 2002–2003, reflecting a 73% decreased risk (P < .0001). If non‐products of the breeding scheme examined in 2010–2011 were compared with dogs in 2002–2003, no difference in odds was found (P = .49).

Conclusion and Clinical Importance

A mandatory breeding scheme based on auscultation and echocardiography findings significantly decreased the prevalence of MMVD over the 8‐ to 10‐year period. Such a breeding scheme therefore is recommended for CKCS.

Keywords: Dog, Genetics, Inheritance, Mitral valve prolapse

Abbreviations

- CKCS

Cavalier King Charles Spaniels

- DKCA

Danish Kennel Club Association

- MMVD

myxomatous mitral valve disease

- MVP

mitral valve prolapse

- non‐PB

non‐products of the breeding scheme

- PB

products of the breeding scheme

Myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) often causes cardiac‐related death in dogs <10 years of age.1 The disease results in valvular extracellular matrix changes including deposition of mucopolysaccarides and collagen degeneration.2 The valvular changes may cause mitral valve prolapse (MVP) and insufficient closure of the mitral valve leading to mitral regurgitation.2 Mitral regurgitation murmur intensity and echocardiographic MVP are predictors of MMVD progression in dogs.3, 4, 5 The disease is most common in small and medium‐sized dog breeds, but often is a relatively benign condition because of its slow disease progression.5, 6 A higher prevalence and earlier onset of the disease have been reported in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels (CKCS) compared to other dog breeds.1, 3, 7 A study from Sweden based on animal insurance data from 1995 to 2006 shows that the disease accounts for 37% of the total mortality among CKCS <10 years of age.1

Hereditary background of MMVD has long been suggested on the basis of a higher prevalence of the disease in certain dog breeds,2 and more recent studies indicate strong genetic background with polygenic inheritance.8, 9 In CKCS, a positive association between parental heart status and mitral regurgitation murmur intensity in 5 year‐old offspring has been reported.8 Furthermore, in Dachshunds, a positive association has been found between the degree of MVP in parents and offspring.9 Based on data from the United Kingdom, a high heritability for MMVD in CKCS has been estimated.10 The heritability for having a mitral regurgitation murmur and for the grade of murmur intensity was estimated to 0.33 and 0.67, respectively.10 Furthermore, a recent genome‐wide association study found 2 gene loci on chromosomes 13 and 14 that differ between CKCS with early and late onset of MMVD.11 However, another similar genome‐wide association study including a lower number of CKCS did not find any association between gene loci and MMVD disease severity.12 Additional studies are needed to further elucidate associations between gene changes and MMVD disease severity.

Breeding restrictions or recommendations aimed at decreasing the prevalence of MMVD in CKCS have been developed in breeding clubs in different countries. The high heritability of the disease indicates that selection against the disease could be successful.10 From 2001, a breeding scheme has been ongoing in Denmark as a collaboration between the Danish Kennel Club Association (DKCA), The Cavalier Club in Denmark and the University of Copenhagen. The aim of thisstudy was to evaluate if a mandatory breeding scheme based on echocardiography and cardiac auscultation results in decreased MMVD severity in CKCS after an 8‐ to 10‐year time period.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

A retrospective study of the mandatory cardiac examinations in the DKCA breeding scheme was performed. Inclusion criteria for the statistical analyses were that the cardiac examinations were performed in the period 2002–2011 (both years included), all data from the individual examination were available, and that the dogs were registered in DKCA. Dogs had to be at least 1.5 years at the first examination and registered in the DKCA with a verified CKCS pedigree. Pregnant and lactating dogs were excluded.

Cardiac Examination and Observers

Cardiac auscultation was performed and the degree of mitral regurgitation murmur was graded from 1 to 6.13 The echocardiographic degree of MVP was evaluated with the dog placed in right lateral recumbency using a right parastenal long axis 4‐chamber echocardiographic view with focus on the mitral valve.14, 15 Echocardiographic recordings were stored on video tape or digitally on DVD. Auscultation and echocardiography were performed by 1 of 8 veterinarians (clinical observers; Table 1). Five clinical observers were general practitioners with cardiovascular interest selected by University of Copenhagen, trained at least 2 days in cardiac auscultation and MVP echocardiography and approved by the founder of the breeding scheme (HDP) in 2001 at University of Copenhagen. Two cardiovascular researchers (LHO and JK) with at least 8 years small animal cardiovascular clinical research experience were included as clinical observers in 2004 and 2009, respectively.

Table 1.

Number of dogs examined by 8 different clinical observers from 2002 to 2011 in the Danish Kennel Club Association (DKCA) myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) breeding scheme

| Clinical observer | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | Total Exams | Number of Excluded Dogs | % Excluded Dogs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 64 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 19 | 29 | 12 | 1 | 133 | 11 | 8.3 |

| 2003 | 57 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 17 | 10 | 2 | 99 | 5 | 5.1 |

| 2004 | 34 | 18 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 24 | 9 | 1 | 95 | 3 | 3.2 |

| 2005 | 0 | 79 | 0 | 10 | 4 | 16 | 7 | 2 | 118 | 4 | 3.4 |

| 2006 | 1 | 79 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 24 | 5 | 2 | 122 | 6 | 4.9 |

| 2007 | 0 | 91 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 31 | 15 | 5 | 154 | 17 | 11.0 |

| 2008 | 0 | 124 | 0 | 8 | 7 | 21 | 7 | 3 | 170 | 10 | 5.9 |

| 2009 | 0 | 117 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 15 | 6 | 8 | 159 | 5 | 3.1 |

| 2010 | 0 | 131 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 11 | 7 | 163 | 8 | 4.9 |

| 2011 | 0 | 123 | 3 | 9 | 5 | 16 | 8 | 3 | 167 | 9 | 5.4 |

| Total | 156 | 763 | 6 | 73 | 57 | 201 | 90 | 34 | 1,380 | 78 | 5.7 |

Echocardiographic Assessment of MVP

The degree of MVP was evaluated by LHO or HDP (MVP observers). The degree of MVP was assessed as 0 (≤1.5 mm as the sum of the maximum protrusion of the cranial, caudal and coaption point of the mitral valve according to annulus plane), 1 (>1.5 and ≤4.5 mm), 2 (>4.5 and ≤7.5 mm), and 3 (>7.5 mm).14, 15, 16 One of the MVP observers (HDP) evaluated the MVP echocardiograms from the debut of the breeding scheme until November 2004, hereafter the recordings were evaluated by the other MVP observer (LHO). The MVP observers made the final approval for the DKCA report (see below).

Breeding Guidelines and Cardiac Health Criteria

Dogs examined ≥1½ years of age were approved for breeding until 4 years of age if cardiac health criteria were fulfilled. To continue breeding in DKCS after 4 years of age dogs had to be reexamined. From January 2007, an additional restriction was decided introducing an additional reexamination after 6 years of age for male dogs. At all examination time points, dogs were excluded from breeding if they had MVP grade 3 (first a criterion from 2007) or a mitral regurgitation murmur grade ≥3. Dogs with grade 2 murmurs were excluded if they had MVP grades 2 or 3. Thus, cardiac health criteria for breeding in the MMVD breeding scheme of the DKCA were as follows: Mitral regurgitation murmur of 1 at a maximum combined with a MVP grade 2 at a maximum; or a grade 2 murmur combined with a degree of MVP not >1. Before 2007, dogs with a grade 3 MVP were approved if they had a murmur grade not >1. Ejection murmurs (physiological flow murmurs) were accepted. They were diagnosed as systolic murmurs with crescendo–decresendo sound configuration, point of maximal intensity at the left heart base and with minimal or no concurrent mitral regurgitation estimated using color flow Doppler echocardiography.17 These dogs often have aortic flow maximum velocity on the higher side of the normal reference range (>1.5 m/s).18 This observation was used to confirm the diagnosis. Dogs with heart murmurs caused by non‐MMVD cardiac disease were excluded. Mitral regurgitation murmur intensity and MVP status of all examined dogs became freely available from DKCA homepage after examination. Each parent needed to fulfill the cardiac health criteria for registration of their puppies in DKCA.

Statistics

All statistical calculations were conducted with a statistical software program (SAS)1 and a statistical significance level of 5% was used.

Logistic regression analysis taking clustering caused by multiple measurements per clinical observer into account was performed using proc genmod in the SAS system. Dogs examined in the years of 2002, 2003, 2010, and 2011 were divided into 3 groups. Group 1 was defined as all dogs examined in 2002 and 2003. Dogs in group 2 were examined in 2010 and 2011, and in addition, were a product of the breeding scheme (PB). Group 3 consisted of dogs also examined in 2010 and 2011 but not a product of the breeding scheme (non‐PB). Products of the breeding scheme were defined as dogs with both parents approved by the DKCA breeding scheme. Only the most recent examination was included in the statistical analyses if a dog had repeated examinations within the time period. The presence of mitral regurgitation murmur (yes/no) or degree of MVP > 1 (yes/no) were included as response variables and age at examination, group (1, 2 or 3) and sex (male or female) were included as explanatory variables. Backward stepwise elimination was performed until only explanatory variables showing significance were left in the model. If an overall significance of group was found, the risk of having a mitral regurgitation murmur or MVP > 1 was compared between group 1 (all dogs examined in 2002 and 2003) and group 2 (PB examined in 2010 and 2011), group 1 and group 3 (non‐PB examined in 2010 and 2011), and finally group 2 and 3, to evaluate a potential effect of the MMVD breeding scheme.

Results

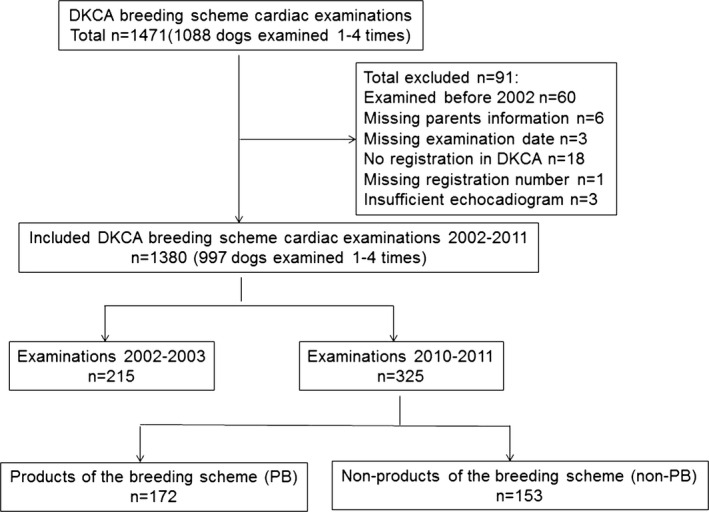

A total of 1,471 cardiac examinations were performed from the debut of the DKCA breeding scheme in December 2001 until the end of 2011. Ninety‐one cardiac examinations were excluded from the statistical analyses according to predefined criteria (Fig 1). A total of 1,380 cardiac examinations were included from 2002 to 2011 (Tables 1 and 2). In the period, 997 dogs were evaluated (689 females and 308 males). Dogs of both sexes were evaluated 1–4 times with an average of 1.4 evaluations per dog. Presence of heart murmur could not be evaluated satisfactorily in 5 dogs and therefore their results regarding murmur were removed from the statistical analyses. Among the 1,380 cardiac examinations, 137 mitral regurgitation murmurs (10%), 83 innocent flow murmurs (6%) and 84 MVP grade 3 (6%) were found. In total, 78 dogs (5.7%; 39 males and 39 females) were excluded from breeding (31 males and 18 females from 2007 to 2011). Among dogs with repeated examinations (n = 343 [306 dogs twice, 34 dogs 3 times and 3 dogs 4 times]), 6 dogs (2%) had decreased degree of mitral regurgitation murmur of 1 grade and 11 dogs (3%) had decreased MVP of 1 grade over time.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for the study.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the dogs examined from 2002 to 2011 in the Danish Kennel Club Association (DKCA) myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) breeding scheme included in the statistical analysis

| Group 1 2002–2003 | Group 2 (PB) 2010–2011 | Group 3 (Non‐PB) 2010–2011 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 215 | 172 | 153 |

| Age (years) | 2.5 (1.8–4.4) | 2.0 (1.7–4.1) | 2.3 (1.6–4.4) |

| Sex (m/f) | 63/152 | 54/118 | 63/90 |

Only the most recent examination was included in the statistical analyses if dogs had repeated examinations. Group 1 is dogs examined in 2002 and 2003. Group 2 and 3 are dogs examined in 2010 and 2011 that are products of the breeding scheme (PB) and nonproducts of the breeding scheme (non‐PB), respectively. f, female; m, male. Except for sex, data are shown as median and 25 and 75% interquartile intervals.

Reduction in Risk of Having a Mitral Regurgitation Murmur

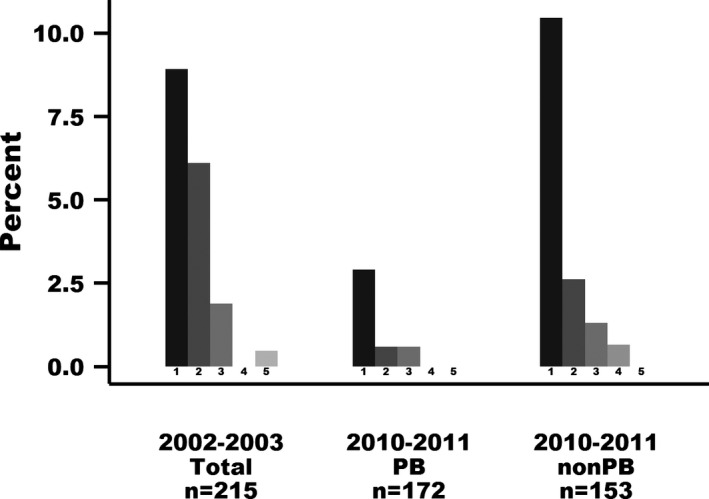

Group and age statistically significantly influenced the presence of mitral regurgitation murmur (Table 3). The odds of having mitral regurgitation murmur in 2010–2011 compared to 2002–2003 were 0.27 if the dogs in 2010–2011 were PB, reflecting a 73% decreased risk (P < .0001; Table 3 and Fig 2). Similarly, within 2010–2011, the odds of having mitral regurgitation murmur for dogs that was PB was 0.31 compared to non‐PB, reflecting 69% decreased risk (P < .0001). If non‐PB examined in 2010–2011 were compared with dogs examined in 2002–2003, no statistical difference in odds of having mitral regurgitation murmur was found (P = .4873). There was no significant influence of sex on odds of murmur. Odds of having a murmur were higher with advancing age (P < .0001; Table 3).

Table 3.

Odds for occurrence of mitral regurgitation murmur and moderate to severe mitral valve prolapse (MVP) in dogs examined in 2010 and 2011 compared with dogs examined in 2002 and 2003

| Response Variable | Variables Adjusted For | PB 2010–2011 Versus 2002–2003 (Group 2 Versus Group 1) | Non‐PB 2010–2011 Versus 2002–2003 (Group 3 Versus Group 1) | PB Versus Non‐PB 2010–2011 (Group 2 Versus Group 3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MR murmur > 0 | Agea at examination (P < .0001) | P | <.0001 | .49 | <.0001 |

| OR | 0.27 | – | 0.31 | ||

| 95% | 0.16–0.43 | – | 0.24–0.41 | ||

| MVP > 1 | Agea at examination and sexb (both P < .0001) | P | .23 | .78 | .0006 |

| OR | – | – | 0.64 | ||

| 95% | – | – | 0.49–0.82 |

Group 1 is dogs examined in 2002 and 2003. Group 2 and 3 are dogs examined in 2010 and 2011 that are products of the breeding scheme (PB) and nonproducts of the breeding scheme (non‐PB), respectively. MR, mitral regurgitation. OR, odds ratio; 95%, 95% confidence interval for the odds ratio.

Odds increase with advancing age.

Male higher odds than female.

Figure 2.

Mitral regurgitation murmur intensity (grade 1–6) in dogs examined in the Danish Kennel Club Association (DKCA) myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) breeding scheme in 2002–2003 and 2010–2011. The Y axis indicates the percentage of dogs with different degrees of mitral regurgitation murmur among dogs examined within the time period. Only the most recent examination is included in the figure if dogs had repeated examinations. PB, products of the breeding scheme. Non‐PB, nonproducts of the breeding scheme.

Reduction in Risk of Having MVP > 1

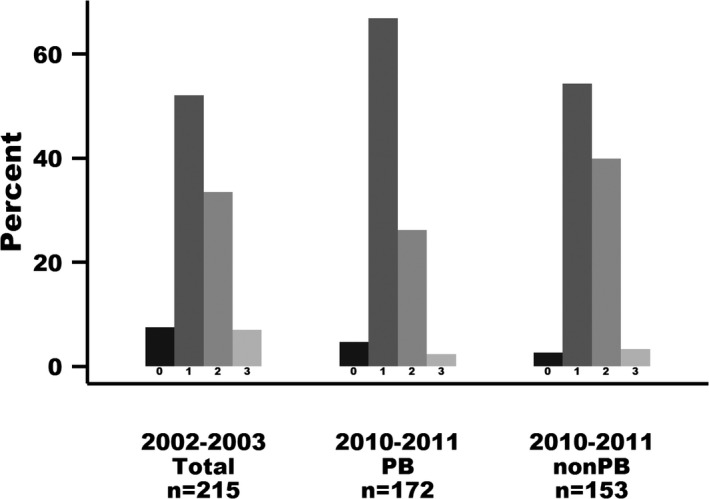

Group, sex, and age at examination significantly influenced the presence of MVP above grade 1 (Table 3). In 2010–2011, the odds of PB having MVP > 1 compared to non‐PB was 0.64 reflecting a 36% reduced risk (P < .0006; Table 3 and Fig 3). There was no significant difference in odds of having MVP > 1 in 2010–2011 compared with 2002–2003.

Figure 3.

Degree of mitral valve prolapse (MVP) (grade 0–3) in dogs examined in the Danish Kennel Club Association (DKCA) myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) breeding scheme in 2002–2003 and 2010–2011. The Y axis indicates the percentage of dogs with different degrees of MVP among dogs examined within the time period. Only the most recent examination is included in the figure if dogs had repeated examinations. PB, products of the breeding scheme. Non‐PB, nonproducts of the breeding scheme.

Discussion

Our study shows that a breeding scheme based on cardiac auscultation and echocardiography markedly decreased the risk of having a mitral regurgitation murmur caused by MMVD after an 8‐ to 10‐year period. The reduction in risk was only significant for offspring where both parents had been approved by the breeding scheme (PB), not for offspring where 1 or both parents not were approved by the breeding scheme (non‐PB). The risk of having moderate to severe MVP (MVP > 1) was not decreased after the 8‐ to 10‐year period, but PB had lower risk of MVP > 1 than did non‐PB within the years 2010 and 2011.

To the authors' knowledge ours is the first study reporting a clear effect of a breeding scheme aimed at decreasing the prevalence of MMVD in CKCS (or in any breed). Preliminary findings from the British voluntary breeding scheme (annual cardiac auscultation and parents' murmur status) reported an effect in the group of dogs auscultated by a general practitioner but only a trend was reported when the dogs were auscultated by a veterinary cardiologist.19 A mandatory breeding scheme in Sweden including annual cardiac auscultation and parent information did not result in significant effect of the scheme, albeit after a short follow‐up period (2007–2009).20

Different breeding schemes aimed at decreasing the prevalence of MMVD in CKCS are ongoing in several countries worldwide to guide dog breeders.19 The breeding schemes are mandatory or voluntary, include cardiac auscultation or both cardiac auscultation and echocardiography and some programs include parent cardiac information. Some schemes include annual cardiac examinations where as others have a more limited number of cardiac examinations during the dog's lifetime. In some schemes, the cardiac examination results are open to the public, in others the results are only known by the dog owner. How much such factors influence the effect of a breeding scheme still needs much clarification.

Voluntary participation may decrease the number of dog owners who follow the breeding advice and thereby decrease the effect of a breeding scheme. In a subanalysis of the voluntary British breeding scheme, it became evident that only 4% of the dog owners had followed the breeding advice.21 Number of included observers and observer experience also may influence the effect of breeding schemes because observer variations are well‐known with regard to cardiac auscultation and echocardiography.14, 17 Therefore interobserver variation was taken into account in the statistical analyses in this study. Unexpected reduction over time in individual mitral regurgitation murmur intensity or degree of MVP was observed in only a few dogs with repeated examinations. The reductions may be the result of changed physiological conditions in the dog such as changed body condition, heart rate, or both.9, 17

Color flow Doppler echocardiography can confirm the diagnosis of mitral regurgitation, but experienced observers can detect mitral regurgitation using auscultation in 89% of dogs with mild or more severe mitral regurgitation (regurgitant jet area >30% of the left atrial area).17 Moderately, experienced observers (general practitioners level) can detect mitral regurgitation in 72% of the dogs by auscultation. Echocardiography is useful to support the diagnosis of ejection murmurs (physiological flow murmurs) and other heart murmurs not associated with mitral regurgitation.17 In this study, approximately 6% of the dogs examined from 2002 to 2011 were diagnosed with ejection murmurs based on clinical findings and echocardiography. In a previous study, 6 of 57 (10%) CKCS were diagnosed with ejection murmurs based on auscultation and phonography.17 Ejection murmurs do not seem to be associated with heart disease,17, 18 and exclusion of dogs with ejection murmurs in breeding schemes may unnecessarily decrease the number of CKCS available for breeding. Estimation of mitral regurgitant jet size in relation to left atrial area using color flow Doppler echocardiography is a semi‐quantitative estimate influenced by several factors including echocardiographic equipment and technical settings.22 This limitation may affect the use of this method in breeding schemes including multicenter clinical examinations.

Studies have shown that MVP is an early predictor of MMVD disease progression and is correlated with other disease variables such as degree of mitral regurgitation and mitral valve thickness.4, 5 In this study, the risk of having moderate to severe MVP was not found to be decrease in the breeding scheme during the 8‐ to 10‐year follow‐up period. However in 2010 and 2011, PB were found to have a decreased risk of having moderate to severe MVP compared to non‐PB suggesting an effect of the breeding scheme on this parameter as well.

The study has limitations. One of the observers in the breeding scheme was replaced in 2004 and the overall observer performance may have changed during the 8‐ to 10‐year time period. Clinical observer was included as random variable in the statistical models to take observer variation into account. However, it was not possible to include MVP observer variation in the modeling. Yet, the finding of a decreased risk of MMVD was confirmed by comparison of the risk of having a mitral regurgitation murmur and moderate to severe MVP (MVP > 1) within a limited time period (2010–2011) between PB and non‐PB during a period with no observer replacements. Finally, it is a study limitation that observers were not blinded to the identity of the dogs.

Further evaluations of breeding schemes are recommended to identify factors with major influence on the effect of such schemes. Echocardiography and mandatory registrations are time‐consuming. Therefore, further evaluation of ongoing breeding schemes is necessary to find the scheme with the highest cost benefit. Until now, the present DKCA breeding scheme is the only scheme with a documented effect. This program is recommended until other breeding schemes aimed at decreasing the prevalence of MMVD with higher performance are described. Genetic tests potentially could be included in future breeding schemes.

In conclusion, a mandatory breeding scheme based on auscultation and echocardiography significantly decreased the prevalence of MMVD over the 8‐ to 10‐year time period. Therefore, such a breeding scheme is recommended for CKCS.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the general veterinary practitioners Christian Mogensen, Varde Animal Hospital, Varde, Denmark; Gustaf Valentiner‐Branth, Bygholm Animal Hospital, Horsens; Mette Rønn‐Landbo, Aalborg Animal Hospital, Aalborg, Denmark; Jesper Lund Sørensen, Rødding and Trekantens Animal Hospital, Rødding, Denmark, Peter Knold, Aarslev Animal Hospital, Aarslev, Denmark; and associate professor Jørgen Koch, Department of Veterinary Clinical and Animal Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Frederiksberg, Denmark, for performing cardiac auscultation and echocardiography of dogs in the breeding scheme. Christina Tirsdal Kjempff, Dennis Jensen and Hanne Carlsson at the Department of Veterinary Clinical and Animal Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Frederiksberg, Denmark are acknowledged for excellent technical assistance.

Conflict of Interest Declaration: Authors disclose no conflict of interest.

Off‐Label Antimicrobial Declaration: Authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobials.

Shared senior authorship: Discussed and agreed on all major issues throughout the study; with HDP being the main driving force before – and LHO after – November 2004.

The work was performed at Departments of Veterinary Disease Biology and Veterinary Clinical and Animal Sciences, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen; Aalborg Animal Hospital, Aalborg; Aarslev Animal Hospital, Aarslev; Bygholm Animal Hospital, Horsens; Rødding and Trekantens Animal Hospital, Rødding; and Varde Animal Hospital, Varde, Denmark.

Preliminary results from this study were presented at the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) Forum in Seattle, Washington, USA, June 2013. The study was supported by The Cavalier King Charles Spaniel Club in Denmark and the Danish Kennel Club Association and by a grant from the Danish National Research Council (Project no. 271‐08‐0998).

Footnote

SAS statistical software, version 9.3, SAS Institute A/S, Cary, NC

References

- 1. Egenvall A, Bonnett BN, Häggström J. Heart disease as a cause of death in insured Swedish dogs younger than 10 years of age. J Vet Intern Med 2006;20:894–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Buchanan JW. Chronic valvular disease (endocardiosis) in dogs. Adv Vet Sci Comp Med 1977;21:75–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Häggström J, Hansson K, Kvart C, Swenson L. Chronic valvular disease in the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel in Sweden. Vet Rec 1992;131:549–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pedersen HD, Lorentzen KA, Kristensen BO. Echocardiographic mitral valve prolapse in cavalier King Charles spaniels: Epidemiology and prognostic significance for regurgitation. Vet Rec 1999;144:315–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Olsen LH, Martinussen T, Pedersen HD. Early echocardiographic predictors of myxomatous mitral valve disease in dachshunds. Vet Rec 2003;152:293–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Borgarelli M, Savarino P, Crosara S, et al. Survival characteristics and prognostic variables of dogs with mitral regurgitation attributable to myxomatous valve disease. J Vet Intern Med 2008;22:120–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Darke PG. Valvular incompetence in cavalier King Charles spaniels. Vet Rec 1987;120:365–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Swenson L, Häggström J, Kvart C, et al. Relationship between parental cardiac status in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels and prevalence and severity of chronic valvular disease in offspring. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1996;208:2009–2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Olsen LH, Fredholm M, Pedersen HD. Epidemiology and inheritance of mitral valve prolapse in Dachshunds. J Vet Intern Med 1999;13:448–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lewis T, Swift S, Woolliams JA, et al. Heritability of premature mitral valve disease in Cavalier King Charles spaniels. Vet J 2011;188:73–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Madsen MB, Olsen LH, Häggström J, et al. Identification of 2 loci associated with development of myxomatous mitral valve disease in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. J Hered 2011;102:S62–S67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. French AT, Ogden R, Eland C, et al. Genome‐wide analysis of mitral valve disease in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. Vet J 2012;193:283–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gompf RE. The clinical approach to heart disease: History and physical examination In: Fox PR, ed. Canine and Feline Cardiology. New York: NY Churchill Livingstone; 1988:29–42. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pedersen HD, Kristensen BO, Lorentzen KA, et al. Mitral valve prolapse in 3‐year‐old healthy Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. An echocardiographic study. Can J Vet Res 1995;59:294–298. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pedersen HD, Olsen LH, Mow T, Christensen NJ. Neuroendocrine changes in Dachshunds with mitral valve prolapse examined under different study conditions. Res Vet Sci 1999;66:11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reimann MJ, Møller JE, Häggström J, et al. R–R interval variations influence the degree of mitral regurgitation in dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease. Vet J 2014;199:348–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pedersen HD, Häggström J, Falk T, et al. Auscultation in mild mitral regurgitation in dogs: Observer variation, effects of physical maneuvers, and agreement with color Doppler echocardiography and phonocardiography. J Vet Intern Med 1999;13:56–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Olsen LH, Hjarbaek R, Pedersen HD. Physiological flow murmurs in cavalier King Charles spaniels. Abstract in the proceeding of the annual meeting of American College of Veterinary Internal medicine (ACVIM), Louisville, Kentucky, USA, 2006:777. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Swift S, Cripps P. Results of the UK Cavalier King Charles Breeding Program: 1991–2010. Abstract in the proceeding of the annual meeting of ACVIM, Seattle, Washington, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lundin T, Kvart C. Evaluation of the Swedish breeding program for cavalier King Charles spaniels. Acta Vet Scand 2010;52:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Häggström J, Swift S, Olsen LH. Canine mitral valve disease: from genetics through screening programs, to practical breeding advice. Abstract in the proceeding of the annual meeting of European Society of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ECVIM), Mainz, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zoghbi WA, Enriquez‐Sarano M, Foster E, et al. Recommendations for evaluation of the severity of native valvular regurgitation with two dimensional and Doppler echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2003;16:777–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]