Abbreviations

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- CNS

central nervous system

- CME

canine monocytic ehrlichiosis

A 10‐year‐old, 4.4 kg, intact female poodle presented with clinical signs of weakness in both hind limbs in May 2013 at the Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand. The dog had a mild fever (39.5°C) and demonstrated hyperesthesia in the lumbar area. Radiographic imaging showed normal appearance of the spine and intervertebral disk spaces. A CBC was within reference ranges. An antipyretic drug, tolfenamic acid, was administered once SC (4 mg/kg), combined with an analgesic drug, tramadol, administered PO (3 mg/kg). The mild fever improved within 24 hours, but the dog still had signs of weakness in the hind limbs and hyperesthesia in the lumbar area. Intervertebral disk disease at the lumbo‐sacral area initially was diagnosed, and anti‐inflammatory doses of a corticosteroid were given for 7 days, after which the clinical signs of weakness in both hind limbs had slightly improved. A month after treatment, in June 2013, there were no signs of hind limb weakness, but recurrence of the same clinical signs occurred for 3 months from June to August 2013, and intermittent 7‐day courses of a corticosteroid were prescribed at subsequent monthly re‐evaluations. On 10th September 2013, the dog was hospitalized with clinical signs of hyperesthesia along the vertebral column and neurologic deficits, including disoriented mental status, unilateral palpebral reflex deficit, and vestibular and cerebellar ataxia. These findings suggested multifocal brain lesions with progressive loss of neurologic functions. A CBC disclosed leukocytosis (26 000 cells/μL) with left shift and mild anemia (hematocrit, 26.8%). Platelet numbers and other blood biochemistry results were normal. Infectious encephalitis was suspected based on the clinical signs and leukocytosis. A sample of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was submitted to the diagnostic laboratory for standard bacterial culture and cytologic examination. The results of CSF culture for bacteria using standard techniques were negative. Subsequently, a broad‐range nested PCR targeting the 16S rRNA gene was performed to confirm bacterial meningoencephalitis. The dog was treated with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (30 mg/kg, PO q12h), dexamethasone (0.05 mg/kg, PO q12h), dimenhydrinate (8 mg/kg, PO q12h), and vitamin B.

DNA was extracted from the CSF sample for the PCR using a DNA extraction Kit1 according to the manufacturer's instructions. A previous study described conserved sequences of the 16S rRNA gene of bacteria that were used for the next‐generation DNA sequencing (pyrosequencing)1. In the current study, we modified these regions to develop the PCR primers for our novel nested PCR, targeting the 16S rRNA gene (16S rDNA). The analytical sensitivity of the nested broad‐range PCR was determined by testing 10 serial 10‐fold dilutions of DNA extracted from Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus spp., Streptococcus spp., Pseudomonas spp., Klebsiella spp., and Proteus spp. The dilutions used ranged from 106–10−3 bacterial colony‐forming units (CFU/mL) and the concentration of DNA extracted from each dilution was measured by spectrophotometer.2 The lowest dilution detected by the PCR was 10−3 CFU/mL from all bacteria analyzed in this study. DNA concentrations of the lowest dilution (10−3 CFU/mL) ranged from 0.5–1.9 ng/μL.

The 16S rDNA primers for the primary PCR consisted of V1‐F (5′ AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG 3′) and V9‐R (5′ GNTACCTTGTTACGACTT 3′). The reaction for the primary PCR was performed using 1 μL of DNA in a 25 μL reaction containing 1× PCR buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 1 μM of each primer, and 0.04 U/μL Taq DNA polymerase.3 The cycling conditions consisted of a pre‐PCR step of 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 60 seconds, 50°C for 60 seconds, and an extension of 72°C for 90 seconds, with a final extension of 72°C for 10 minutes. Expected length of the primary PCR product was 1400 bp. PCR primers for the secondary PCR consisted of V3‐F (5′ ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG 3′) and V6‐R (5′ CGACAGCCATGCANCACCT 3′), also modified from a previous study.1 The reaction for the secondary PCR was performed using 1 μL of DNA in a 25 μL reaction containing 1× PCR buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 1 μM of each primer, and 0.04 U/μL Taq DNA polymerase3. The cycling conditions consisted of a pre‐PCR step of 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 60 seconds, 55°C for 45 seconds and an extension of 72°C for 45 seconds with a final extension of 72°C for 10 minutes. Expected length of the secondary PCR product was approximately 700 bp. All PCR products were purified from agarose gel slices using a DNA purification kit.4 Sequencing was performed using a Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit5 in an Applied Biosystems 3730 DNA Analyzer, following the manufacturer's instructions. The 16S rDNA sequence was analyzed by the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST). Bacterial 16S rDNA was detected in the CSF by PCR, and the DNA sequence derived from the PCR product was most closely related to Ehrlichia canis in the GenBank database, accession number KC479024, with 99% identity.

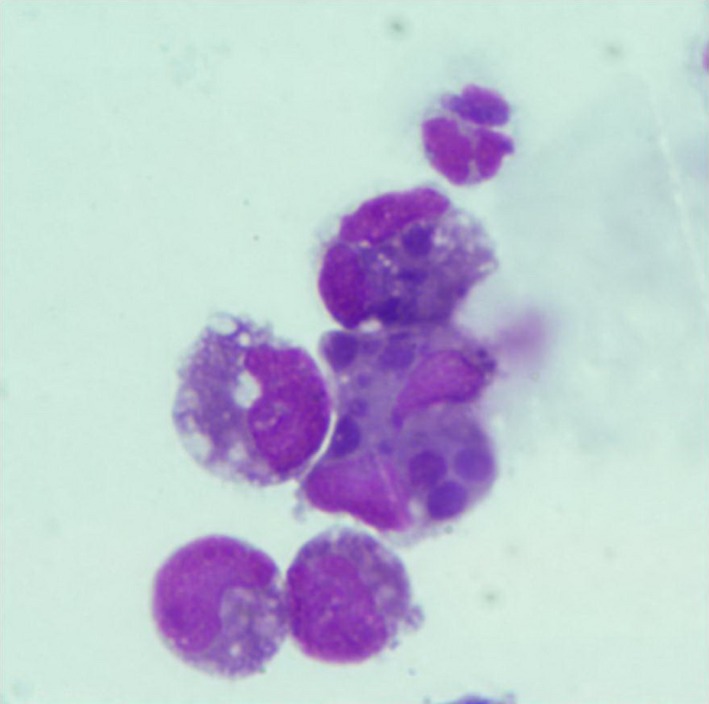

Cerebrospinal fluid analysis disclosed an increased protein concentration (197 mg/dL; reference range, 0–30 mg/dL) and mixed cell pleocytosis (34/μL; reference range, 0–5/μL). Cytologic findings included nondegenerative neutrophils, small lymphocytes, mononuclear cells, and macrophages with engulfed red cells, fat droplets, or both. In addition, intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, consistent with Ehrlichia spp. morulae, were found in mononuclear cells. These findings indicated possible meningoencephalitis caused by E. canis (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Photomicrograph of cerebrospinal fluid cytology. Mixed cell pleocytosis composed of mononuclear cells, lymphocytes, and neutrophil. Several round‐shaped basophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions were seen in mononuclear cells (Wright‐Giemsa stain).

Following the infrequent findings from the BLAST algorithm and CSF analysis, a suicide PCR protocol was adopted to confirm the organism's genetic identity and to prevent cross‐contamination of 16S rDNA amplicons.2 The suicide PCR protocol to overcome the issue of contamination in PCR reactions was first described in a study of the causative agent of the Black Death that killed millions in Western Europe during the 14th century.2 False‐positive PCR results commonly occur in ancient human remnants which have been exposed to and colonized by modern saprophytic microflora. Second and third primer pairs from novel loci were included in the protocol to confirm the identification of Yersinia pestis DNA in the ancient human specimens.2 However, to avoid PCR amplicon cross‐contamination, Good Laboratory Practice is most important and should not be replaced by the suicide PCR procedure. The suicide PCR was adopted in this study to confirm the unexpected finding of E. canis DNA in the CSF of this unusual clinical case and to rule out potential cross‐contamination of the 16S rRNA amplicons. The amplification of a novel gene, the gp36 of E. canis, was performed once without the addition of a positive control. This novel locus had never been amplified previously and was targeted only once with fresh primers. The suicide PCR protocol confirmed that detection by the 16S PCR had not resulted from cross‐contamination in our laboratory.

The PCR targeting the gp36 locus of E. canis was performed and DNA sequencing of the resulting PCR product was completed after the first amplification. PCR primers for the gp36 gene, EC36‐F1 (5′‐GTATGTTTCTTTTATATCATGGC‐3′) and EC36‐R1 (5′‐GGTTATATTTCAGTTATCAGAAG‐3′) were used based on a previous study.3 Nucleotide sequences generated for both loci were analyzed by Chromas lite version 4.0 (http://www.technelysium.com.au) and aligned with reference sequences from E. canis from GenBank using Clustal W (http://www.clustalw.genome.jp). A phylogenetic tree of the gp36 gene was constructed by the distance method and the program Mega version 5.1.6

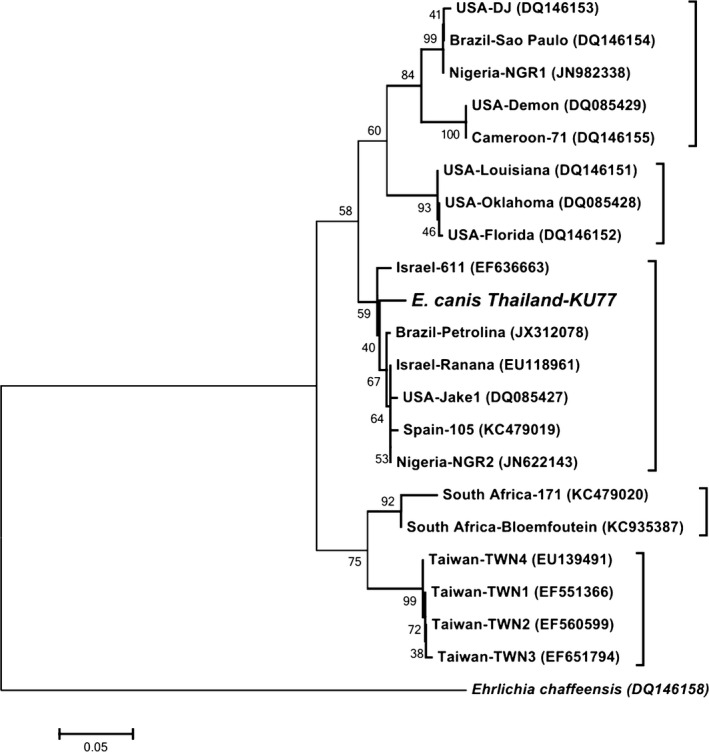

The 16S rRNA and gp36 loci sequences were submitted to GenBank with accession numbers KM879929 and KM879930, respectively. A neighbor‐joining phylogenetic tree of the gp36 gene was constructed and indicated that the E. canis‐like genotype detected in the present study was closely related to other validated genotypes reported from Israel, Brazil, United States, Spain, and Nigeria (89.5–96.1% identity; Fig 2). These genotypes were classified as E. canis cluster A in a previous report.4 However, the dog died before advanced brain imaging was performed. The molecular diagnosis and CSF cytology results were recorded subsequently.

Figure 2.

Neighbor‐joining phylogenetic tree of the gp36 gene of Ehrlichia canis detected in the cerebrospinal fluid of a dog in Thailand and validated genotypes of E. canis. Percentage bootstrap support (>40%) from 1000 pseudoreplicates is indicated at the left of the supported node.

Ehrlichia canis, a tick‐borne pathogen, mainly transmitted by Rhipicephalus sanguineus, is the cause of canine monocytic ehrlichiosis (CME), which is a multisystemic disease resulting in hematologic abnormalities and respiratory, ocular or neurologic sequelae.5 Coagulation disorder, because of severe thrombocytopenia and platelet dysfunction, is the most prominent sign of infection with E. canis.5, 6 The organism has resulted in high morbidity and mortality in dogs in Southeast Asia since it was first described affecting US military dogs during the Vietnam War in the 1960s.7 However, published reports in this region, of both clinical manifestations and genetic studies, are very limited.8, 9, 10 Genus‐specific primers for Thai Ehrlichia and Anaplasma were designed based on the 16S rRNA sequences10. These genus‐specific primers and sequence analysis allow detections of diverse genotypes of the organisms in this region10 and this report demonstrated advantage of next‐generation diagnostics which include broad‐range PCR primers and sequence analysis.

Persistent infection of Ehrlichia muris in a mouse model was shown to induce antibodies that protected the mice against an ordinarily lethal secondary Ixodes ovatus Ehrlichia challenge.11 In the study, antigen‐specific gamma interferon (INF)‐producing splenic memory T cells played a major role in the immune protection of the infected mice without doxycycline treatment.11 Because corticosteroids have been shown to inhibit production of IL‐12, a cytokine known to enhance gamma IFN synthesis in mouse splenic adherent cells,12 the use of corticosteroids in our treatment protocol could have compromised the immune status of this dog, which was most likely in the chronic or subclinical phase of CME, accompanied by persistent infection with E. canis. Where possible, diagnosis of chronic or persistent infections of E. canis in dogs in endemic areas should be performed before corticosteroid treatment to avoid possible recrudescence of infection. Serodiagnostic tests before corticosteroid treatment of patients have been recommended in strongyloidiasis in humans in endemic regions,13 because latent infections with the parasite, Strongyloides stercoralis, have been described and massive invasion by filariform larvae has been triggered by corticosteroid treatment.14 In addition, severe strongyloidiasis has been prevented in corticosteroid‐treated patients by administration of prophylactic ivermectin.13 These strategies could be applied for treatment of potential E. canis cases in endemic regions and in the future, serodiagnostic tests for E. canis will be recommended before corticosteroid treatment and, if long‐term corticosteroids are warranted, prophylactic doxycycline will be used. Chemoprevention programs using doxycycline were performed and validated in French military dogs working in E. canis endemic areas.15 Each dog was administered doxycycline at (3 mg/kg bodyweight, PO q24h) for at least 4 months. The CME mortality and morbidity rates for these 614 dogs in this study were not detected and the seroconversion rate was very low (4%; 24/614). In addition, there were no clinical signs in the seropositive dogs (low titers), and seronegative in these dogs occurred after doxycycline treatment.15

This dog showed typical clinical signs of bacterial meningoencephalitis as described. Therefore, initial treatment was based on a diagnosis of bacterial encephalitis. Unfortunately, as a result of the unusual clinical and hematologic findings of this case, E. canis was not included in the differential diagnosis and thus initially there were no specific tests used for E. canis infection (eg, specific PCR or antibody detection). In retrospect, the rapidly progressing CNS signs in this dog most likely resulted from E. canis infection, confirmed by CSF cytology, sequencing result of the 16S rRNA gene, and phylogenetic analysis of the gp36 gene. Neurologic deficits of ehrlichial meningoencephalitis are influenced by plasma cell infiltration of the meninges or hemorrhage in cerebral or spinal cord parenchyma.16, 17 The first detection of E. canis in CSF was reported from the United States in 1989 and the report described seizures as the dominant sign in the infected dog, together with nonregenerative anemia and chronic thrombocytopenia.18 A subsequent report in 2012 from Japan also described ataxia of the hind limbs in the infected dog, with nonregenerative anemia and severe thrombocytopenia.16 In addition, the case from Japan reported xanthochromia in the CSF, which is consistent with subarachnoid hemorrhage. There is less information in the literature describing meningoencephalitis associated with ehrlichiosis in dogs without thrombocytopenia and bleeding tendency, as was the case in our patient. A normal platelet count and transient thrombocytopenia were previously reported in a dog with an uncommon case of severe hepatitis associated with acute E. canis infection.19 The use of ampicillin and enrofloxacin to treat this dog was based on an initial diagnosis of infectious hepatitis caused by leptospirosis. Ehrlichia spp. morulae were subsequently found after liver impression cytology, and treatment was changed to doxycycline at 7 days postadmission.19

The CSF abnormalities reported in our case are nonspecific and easily could be attributed to general bacterial meningoencephalitis. Presumptive diagnosis and treatment in such cases frequently is performed for bacterial or other causes of CSF pleocytosis, and canine erhlichiosis is regularly excluded from the differential diagnosis, particularly in nonthrombocytopenic cases. Consequently, in this case, doxycycline (the drug of choice for CME) was not administered. Although various pathogens could have been eliminated using specific PCR assays for each organism, the broad‐range PCR technique we adapted was quicker and more advantageous and should be recommended for the diagnosis of patients with negative CSF culture results, including the diagnosis of atypical CME.

Acknowledgments

We thank all staff from the Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory and Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kasetsart University, Bangkok for their support in this study. We also thank for Dr Nipon Wongprasert for technical support.

Conflict of Interest Declaration: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Off‐label Antimicrobial Declaration: Authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobials.

Funding: This study was supported by a grant provided by the Thailand Research Fund, Office of the Higher Education Commission and Kasetsart University Research and Development Institute.

Footnotes

E.Z.N.A.R Tissue DNA Kit, Omega Bio‐Tek, Inc., Norcross, GA

NanoDrop 1000 Spectrophotometer V3.7, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Wilmington, DE

Taq DNA polymerase, InvitrogenR, Life technologies, Carlsbad, CA

UltraCleanTM 15 DNA Purification Kit, MO BIO Laboratories Inc., Carlsbad, CA

ABI Prism™ Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA

Mega5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis software, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ

References

- 1. Cai L, Ye L, Tong AH, et al. Biased diversity metrics revealed by bacterial 16S pyrotags derived from different primer sets. PLoS One 2013;8:e53649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Raoult D, Aboudharam G, Crubezy E, et al. Molecular identification by “suicide PCR” of Yersinia pestis as the agent of medieval black death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000;97:12800–12803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hsieh YC, Lee CC, Tsang CL, Chung YT. Detection and characterization of four novel genotypes of Ehrlichia canis from dogs. Vet Microbiol 2010;146:70–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zweygarth E, Cabezas‐Cruz A, Josemans AI, et al. In vitro culture and structural differences in the major immunoreactive protein gp36 of geographically distant Ehrlichia canis isolates. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 2014;5:423–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Castro MB, Machado RZ, de Aquino LP, et al. Experimental acute canine monocytic ehrlichiosis: Clinicopathological and immunopathological findings. Vet Parasitol 2004;119:73–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bulla C, Kiomi Takahira R, Pessoa Araujo J Jr, et al. The relationship between the degree of thrombocytopenia and infection with Ehrlichia canis in an endemic area. Vet Res 2004;35:141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Greene CE. Ehrlichia and Anaplasma infections In: Greene CE, ed. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat, 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:227. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Foongladda S, Inthawong D, Kositanont U, Gaywee J. Rickettsia, Ehrlichia, Anaplasma, and Bartonella in ticks and fleas from dogs and cats in Bangkok. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2011;11:1335–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jirapattharasate C, Chatsiriwech J, Suksai P, et al. Identification of Ehrlichia spp. in canines in Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2012;43:964–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pinyoowong D, Jittapalapong S, Suksawat F, et al. Molecular characterization of Thai Ehrlichia canis and Anaplasma platys strains detected in dogs. Infect Genet Evol 2008;8:433–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thirumalapura NR, Crossley EC, Walker DH, et al. Persistent infection contributes to heterologous protective immunity against fatal ehrlichiosis. Infect Immun 2009;77:5682–5689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. De Kruyff RH, Fang Y, Umetsu DT. Corticosteroids enhance the capacity of macrophages to induce Th2 cytokine synthesis in CD4 + lymphocytes by inhibiting IL‐12 production. J Immunol 1998;160:2231–2237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fardet L, Genereau T, Cabane J, et al. Severe strongyloidiasis in corticosteroid‐treated patients. Clin Microbiol Infect 2006;12:945–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Siddiqui AA, Berk SL. Diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Clin Infect Dis 2001;33:1040–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Davoust B, Keundjian A, Rous V, et al. Validation of chemoprevention of canine monocytic ehrlichiosis with doxycycline. Vet Microbiol 2005;107:279–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Baba K, Itamoto K, Amimoto A, et al. Ehrlichia canis infection in two dogs that emigrated from endemic areas. J Vet Med Sci 2012;74:775–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Woody BJ, Hoskins JD. Ehrlichial diseases of dogs. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1991;21:75–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meinkoth JH, Hoover JP, Cowell RL, et al. Ehrlichiosis in a dog with seizures and nonregenerative anemia. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1989;195:1754–1755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mylonakis ME, Kritsepi‐Konstantinou M, Dumler JS, et al. Severe hepatitis associated with acute Ehrlichia canis infection in a dog. J Vet Intern Med 2010;24:633–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]