Abstract

Setting: Integrated HIV Care programme, Mandalay, Myanmar.

Objectives: To determine time to starting antiretroviral treatment (ART) in relation to anti-tuberculosis treatment (ATT) and its association with TB treatment outcomes in patients co-infected with tuberculosis (TB) and the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) enrolled from 2011 to 2014.

Design: Retrospective cohort study.

Results: Of 1708 TB-HIV patients, 1565 (92%) started ATT first and 143 (8%) started ART first. Treatment outcomes were missing for 226 patients and were thus not included. In those starting ATT first, the median time to starting ART was 8.6 weeks. ART was initiated after 8 weeks in 830 (53%) patients. Unsuccessful outcome was found in 7%, with anaemia being an independent predictor. In patients starting ART first, the median time to starting ATT was 21.6 weeks. ATT was initiated within 3 months in 56 (39%) patients. Unsuccessful outcome was found in 12%, and in 20% of those starting ATT within 3 months. Patients with CD4 count <100/mm3 had a four times higher risk of an unsuccessful outcome.

Conclusions: Timing of ART in relation to ATT was not an independent risk factor for unsuccessful outcome. Extensive screening for TB with rapid and sensitive diagnostic tests in HIV-infected persons and close monitoring of anaemia and immunosuppression are recommended to further improve TB treatment outcomes among patients with TB-HIV.

Keywords: HIV-associated TB, treatment outcome, operational research, SORT IT, early ART initiation, adverse TB treatment outcomes

Abstract

Contexte : Programme intégré de prise en charge du virus de l'immunodéficience humaine (VIH), Mandalay, Myanmar.

Objectifs : Chez les patients atteints de tuberculose (TB) et VIH enrôlés entre 2011 et 2014, déterminer la date du début du traitement antirétroviral (TAR) en relation avec le traitement antituberculeux (ATT) et son association avec le résultat d'ATT.

Schéma : Etude rétrospective de cohorte.

Résultats : Sur 1708 patients TB-VIH, 1565 (92%) ont débuté l'ATT en premier et 143 (8%) ont commencé le TAR en premier. Le résultat du traitement a été manquant pour 226 patients qui n'ont pas été inclus. Chez les patients ayant débuté l'ATT en premier, le délai médian de mise en route du TAR a été de 8,6 semaines. L'initiation du TAR a été retardée d'un délai médian de 8 semaines chez 830 (53%) patients. Parmi ces patients, 7% ont eu un résultat médiocre, avec une anémie qui a constitué un facteur de risque indépendant. Chez les patients ayant débuté le TAR en premier, le délai médian de mise en route de l'ATT a été de 21,6 semaines. L'ATT a été initié au cours des 3 mois chez 56 (39%) patients. Le traitement a échoué chez 12% des patients et chez 20% de ceux qui ont débuté l'ATT dans les 3 mois. Les patients ayant des CD4 <100/mm3 ont eu un risque quatre fois plus élevé d'échec.

Conclusions: La chronologie du TAR en rapport avec l'ATT n'a pas été un facteur de risque indépendant d'échec du traitement. Un dépistage extensif de la TB avec des tests de diagnostic rapides et sensibles chez les personnes infectées par le VIH et un suivi étroit de l'anémie et de l'immunosuppression sont recommandés afin d'améliorer encore le résultat du traitement de TB parmi les patients TB-VIH.

Abstract

Marco de referencia: El programa integrado de atención de la infección por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana (VIH) en Mandalay, en Birmania.

Objetivos: Determinar el lapso entre el comienzo del tratamiento antirretrovírico (ART) y el inicio del tratamiento antituberculoso (ATT) en los pacientes coinfectados registrados del 2011 al 2014 y su asociación con el desenlace del ATT.

Método: Fue este un estudio retrospectivo de cohortes.

Resultados: De los 1708 pacientes coinfectados por el VIH y la tuberculosis (TB), 1565 iniciaron primero el ATT (92%) y 143 comenzaron en primer lugar el ART (8%). Se excluyeron 226 casos que carecían de registro del desenlace terapéutico. En los pacientes que iniciaron en primer lugar el ATT, la mediana del lapso hasta el comienzo del ART fue 8,6 semanas; este tratamiento se inició después de 8 semanas en 830 pacientes (53%). Se observó un desenlace terapéutico desfavorable en 7% de estos pacientes; la principal variable independiente asociada fue la presencia de anemia. Cuando el ART se inició en primer lugar, la mediana hasta el comienzo del ATT fue 21,6 semanas; este tratamiento se inició durante los 3 primeros meses en 56 pacientes (39%). Se observó un desenlace terapéutico desfavorable en 12% de estos pacientes y en 20% de los pacientes que iniciaron el ART en los primeros 3 meses. El riesgo de un desenlace desfavorable fue cuatro veces más alto en los pacientes con un recuento de linfocitos CD4 <100 células/mm3.

Conclusión: La coordinación cronológica del ART y el ATT no representó un factor independiente de riesgo de obtener un desenlace desfavorable. Se recomienda la detección sistemática de la TB en los pacientes infectados por el VIH mediante pruebas diagnósticas rápidas y sensibles y una supervisión cuidadosa de la anemia y la inmunodepresión, con el objeto de obtener aun mejores desenlaces del ATT en los pacientes aquejados de coinfección TB-VIH.

The success of tuberculosis (TB) control is threatened by the increase in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) associated TB. In 2014, 9.6 million patients globally were estimated to have developed TB, of whom 1.2 million (12%) were co-infected with HIV. Of these, 390 000 (33%) died while undergoing anti-tuberculosis treatment (ATT).1 This mortality rate is high considering that TB can be successfully cured with standard ATT regimens and HIV can be successfully managed with long-term antiretroviral therapy (ART). In 2012, the World Health Organization (WHO) published a policy document on collaborative TB-HIV activities to reduce the burden of dual disease that focused on 1) mechanisms for delivering integrated TB and HIV services, 2) early ART and the ‘Three I's’ (intensified case finding, isoniazid preventive therapy and TB infection control for people living with HIV) to reduce the burden of TB in people living with HIV, and 3) activities to reduce the burden of HIV in patients with presumptive and diagnosed TB.2

Myanmar ranks seventeenth among the 22 high TB burden countries, and has one of the most severe HIV/AIDS (acquired immune-deficiency syndrome) epidemics in Asia, with a prevalence of 0.53% in adults.1,3 As a result of this dual epidemic, there is likely to be a significant burden of HIV-associated TB. In 2013, according to the WHO report, only 16 882 (12%) of the notified TB patients in the country were HIV tested; 5413 were found to be HIV-positive, of whom 4006 (74%) were recorded as being on ART during ATT.3 For the 2011 TB cohort, only 65% of HIV-infected TB patients successfully completed treatment, which was much lower than the rate of 89% amongst newly diagnosed TB patients overall. These data suggest that 1) there is a significant pool of patients with TB-HIV who are not diagnosed or offered HIV care, and 2) for those who are diagnosed and treated, outcomes are poor.

Amongst the TB-HIV patient cohort in the Integrated HIV Care (IHC) programme in Mandalay, one group of adults was initiated on ART after starting ATT (ATT-first group) and the second group was initiated on ATT after ART (ART-first group). This provides an opportunity to assess TB treatment outcomes in both groups. In the ATT-first group, it is now well established that an earlier start of ART after ATT commencement, especially in those with low CD4 cell counts, is associated with reduced TB case fatality.4–6 In Myanmar, there is no published national information about when patients with TB-HIV start ART or whether this affects TB treatment outcomes. This study was therefore planned in the IHC programme, Mandalay, Myanmar, between 2011 and 2014 with the following objectives: to determine among patients with TB-HIV 1) the time to start ART and the relationship to TB treatment outcomes in the ATT-first group; and 2) the time spent on ART before ATT and the relationship to TB treatment outcomes in the ART-first group.

METHODS

Study design

This was a retrospective cohort study involving record review.

Setting

General setting

Myanmar, situated in South-East Asia, has an estimated population of 53 million, of whom 60% live in rural areas. The National Tuberculosis Programme (NTP), together with partners, offers diagnostics, cost-free treatment and follow-up services for patients with presumptive and confirmed TB, based on the WHO TB treatment guidelines.7 The National AIDS Programme (NAP), together with partners, offers HIV testing and counselling, and for HIV-positive patients, care and ART.8 TB-HIV collaborative activities in Myanmar were launched in collaboration with the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union) in Mandalay in seven townships in 2005. After scaling up decentralisation of HIV counselling and testing, TB-HIV sites had expanded to 236 townships by 2015.

Integrated HIV Care programme and study site

The Union implements the IHC programme in the public sector in 24 townships through 34 service delivery clinics in Myanmar in collaboration with the NTP, the NAP and the Ministry of Health (MOH). The details of the IHC programme and the ART and ATT regimens used have been described previously.9 Briefly, the first-line ART regimen up to 2012 was zidovudine or stavudine with lamivudine and nevirapine or efavirenz; since 2012 it has consisted of tenofovir, lamivudine and efavirenz. The second-line regimen is protease inhibitor based. ATT regimens follow WHO guidelines.7 For the sake of infection control, all TB-HIV patients are enrolled in one particular clinic in the Mandalay IHC programme. All TB-HIV patients are initiated on ART and cotrimoxazole preventive therapy (free of charge) in line with the NAP guidelines, based on the WHO 2010 guidelines.8,10

Along with the necessary laboratory investigations, all patients on ART are carefully monitored at the clinics by clinicians, and are seen every 3 months if healthy and more frequently if sick. The data for patients initiating ART and followed up on treatment are entered in patient files that are kept securely in lockable cabinets. Every week these data are single-entered into a central electronic database at the office headquarters in Mandalay.

Patient population

All patients with TB-HIV (aged ⩾15 years) enrolled in the Mandalay IHC programme and initiated on ART between 2011 and 2014 were included in the study. Drug-resistant TB cases were excluded from the study.

Data variables, sources of data and data collection

The source of data was the Mandalay central electronic database, and data were extracted between March and November 2015. Data variables included the IHC registration number; the start date of ATT; the start date of ART; the age at the time of ATT initiation; sex; CD4 cell count and body mass index (BMI) before or after 6 months of ATT initiation; haemoglobin, hepatitis B and hepatitis C status at the time of registration at the IHC clinic; the category and site of TB; and TB treatment outcomes. The classification of anaemia and BMI (for Asian populations) were per WHO recommendations.11,12

Analysis and statistics

Data were extracted into Excel (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA, USA) and imported into EpiData analysis software version 2.2.2.183 (EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark). Univariate analysis and adjustment for single confounders was performed using Epi-Data analysis software. Multivariate analysis was performed using STATA version 12.1 (STATA Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

Analyses were performed in relation to the two groups of TB-HIV patients: ATT first and ART first. Within each group, frequency and proportions were used to summarise baseline characteristics and ATT outcomes. The median interquartile range (IQR) was used to summarise the time between ATT and ART. Associations between ATT outcomes and time between ART and ATT (including baseline characteristics) were summarised using relative risks (adjusted for confounding wherever applicable using the Mantel Haenszel method) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Among those who started ATT first, log binomial regression (enter method) was used and variables with univariate P < 0.2 were included in the model. Among those who started ART first, we did not perform log binomial regression because a high number of records (30%) had missing data in at least one of the explanatory variables.

Ethics approval

Permission for the study was obtained from the Myanmar NAP and NTP. Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethics Advisory Group, The Union, Paris, France. As this study involved the analysis of secondary programmatic data, the need for informed patient consent was waived.

RESULTS

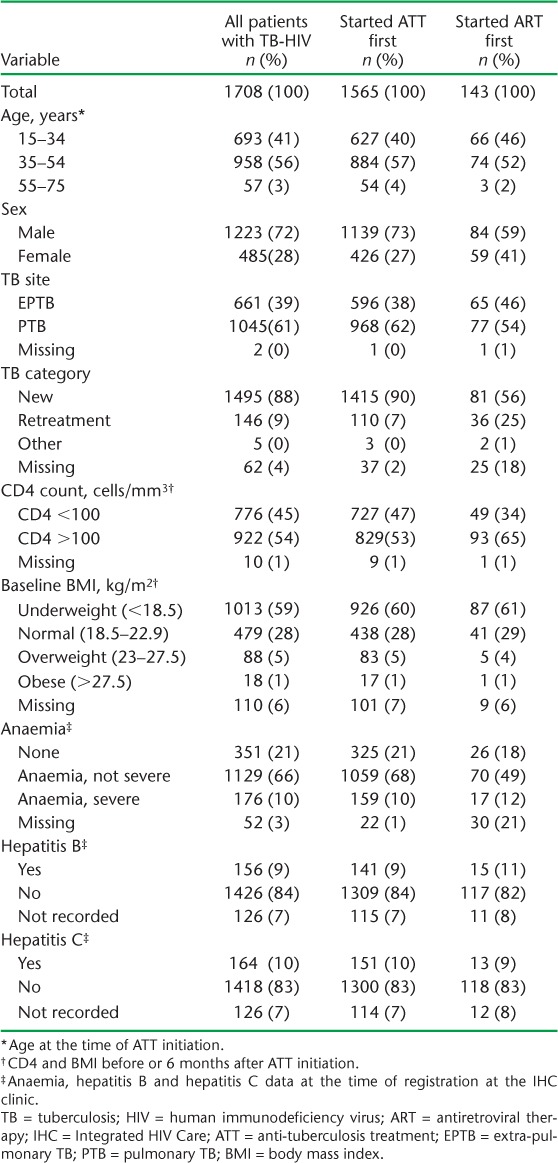

Between 2011 and 2014, 1934 patients with TB-HIV were enrolled on treatment. Of these, 226 (12%) had no treatment outcomes recorded, and 1708 patients with TB-HIV were included in the study. The baseline characteristics of the study participants are summarised in Table 1. At the time of ATT initiation, 776 (45%) had a baseline CD4 <100/mm3 and 1013 (59%) were underweight. At the time of entry into IHC care, 1305 (76%) patients had anaemia, 156 (9%) were seropositive for hepatitis B and 164 (10%) were seropositive for hepatitis C.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of all patients with TB-HIV initiated on ART at the IHC programme, Mandalay, Myanmar, 2011–2014

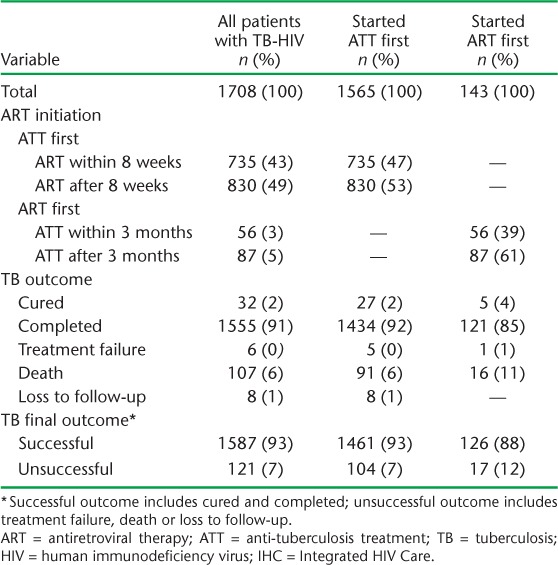

The timing of ART in relation to ATT and the ATT outcomes are shown in Table 2. Of all patients with TB-HIV (n = 1708), 1565 (92%) started ATT first and 143 (8%) started ART first.

TABLE 2.

ART initiation and ATT outcomes of all patients with TB-HIV initiated on ART in the IHC programme, Mandalay, Myanmar, 2011–2014

‘ATT-first’ group

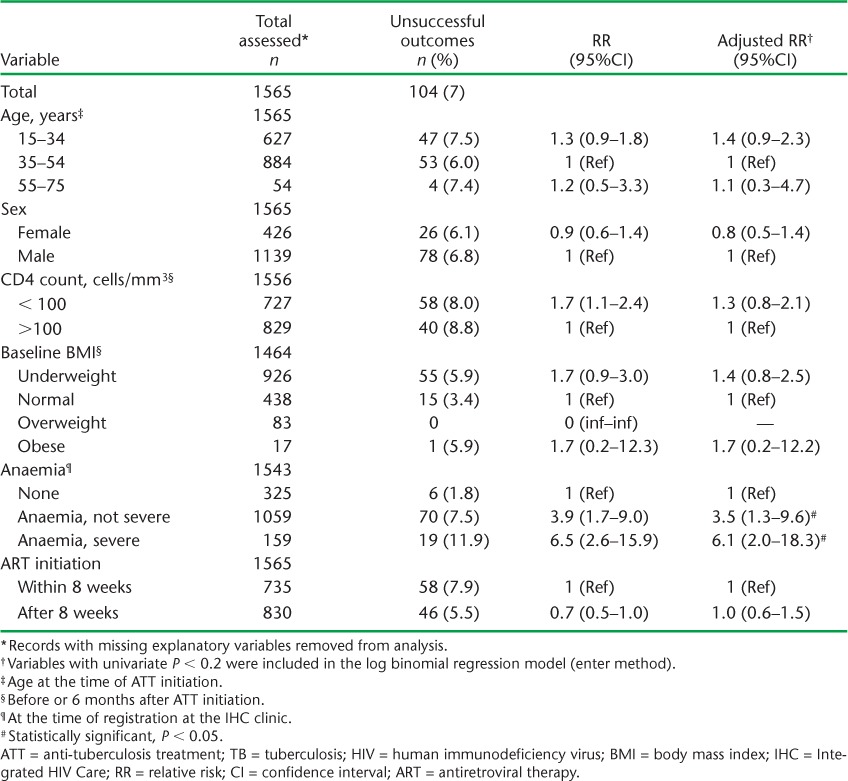

Among those patients who started ATT first, ART was initiated within 8 weeks of starting treatment in 735 (47%) patients and after 8 weeks in 830 (53%) patients (Table 2). The median (IQR) time in weeks to initiation of ART was 8.6 (5.7–13.7). Seven per cent of the patients had an unsuccessful outcome (Table 2). After adjusting for various confounders, patients with non-severe anaemia had a 3.5 times higher risk of an unsuccessful outcome, while those with severe anaemia had a 6 times higher risk, compared with patients with no anaemia. The timing of ART initiation (early or late) was not significantly associated with unsuccessful outcomes (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Risk factors associated with unsuccessful ATT outcomes among patients with TB-HIV who initiated ATT first in the IHC programme, Mandalay, Myanmar, 2011–2014

‘ART-first’ group

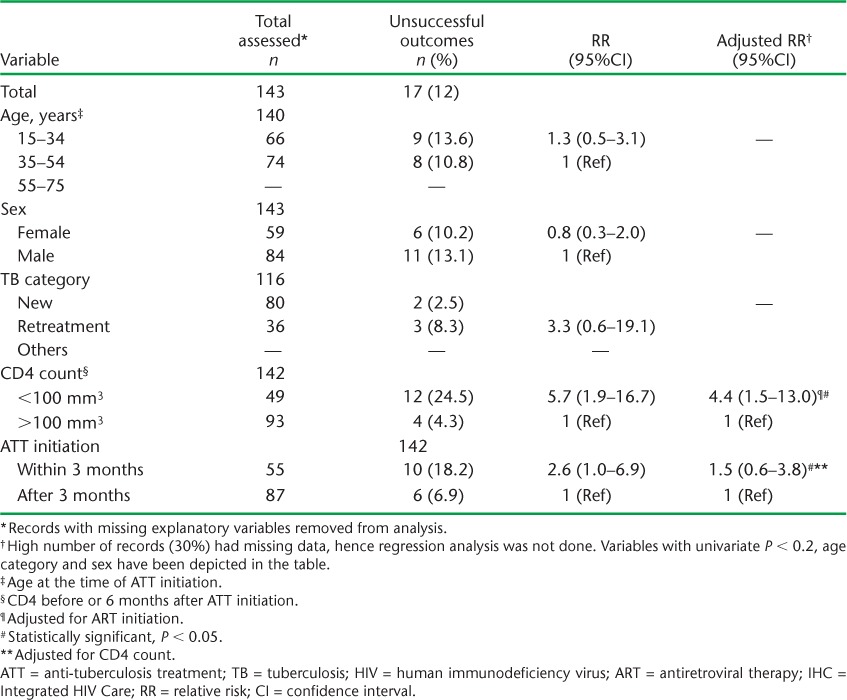

Among those patients who started ART first, ATT was initiated within 3 months of initiating ART in 56 (39%) patients, while 87 (61%) started ATT after 3 months (Table 2). The median (IQR) time in weeks to starting ATT was 21.6 (6.0–60.7). An unsuccessful outcome was recorded for 12% of the patients (Table 2) and for 19.6% of a subset of patients who started ATT within 3 months of starting ART (data not shown). After adjusting for ATT initiation, patients with a CD4 count <100/mm3 had a more than four-fold higher risk of an unsuccessful outcome compared to patients with a CD4 count >100/mm3. Patients who were started on ATT within 3 months had a three-fold higher risk of an unsuccessful treatment outcome compared with those who started ATT after 3 months. However, this association appeared to be confounded by CD4 count (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Risk factors associated with unsuccessful ATT outcomes among patients with TB-HIV who initiated ART first at the IHC Programme, Mandalay, Myanmar, 2011–2014

DISCUSSION

This is the first study from Myanmar to evaluate the timing of ART and associated ATT outcomes in a large TB-HIV cohort over 3 years. The overall proportion of patients with an unsuccessful treatment outcome was small. In those starting ART first, the risk of an unsuccessful outcome was higher in patients with a low CD4 count and in those who commenced on ATT within the first 3 months, although the timing of ATT was not an independent risk factor. In patients starting ATT first, anaemia appeared to be the most significant factor associated with an unsuccessful outcome.

The strengths of this study are a robust methodology, which included pre-defined operational definitions for the study population and variables, a large sample, adjusted measures of association and adherence to the Strengthening The Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for conducting and reporting on observational studies.13 As we studied the entire population of patients with TB-HIV initiated on ART between 2011 and 2014 at the study site, the results are likely to be representative for the region. However, there were some limitations. Data on TB treatment outcomes were missing for more than 10% of the patients. There was a high proportion of missing data for TB treatment outcome dates, which precluded a time to event analysis. As data on the ART regimen at the time of ATT initiation were not readily available, we could not determine the effect of ART regimens on treatment outcomes. Data on haemoglobin were recorded on entry to the IHC clinic and not during ATT initiation.

There were some important findings in this study. First, baseline anaemia at entry to the IHC clinic was common and an independent risk factor for unsuccessful ATT outcomes in those starting ATT first. Moderate to severe anaemia at entry into HIV care increases the risk for TB among HIV-infected patients.14 Previous studies have also documented a high prevalence of anaemia in patients with TB-HIV, associated with delayed sputum conversion, poor immune recovery and increased mortality.15–19

Second, the timing of ART in relation to ATT was not an independent risk factor for unsuccessful outcomes. It is well known that ART before or after ATT is associated with decreased TB mortality.20,21 Early initiation of ART within 8 weeks of ATT or within 2–4 weeks is associated with a lower risk of mortality, especially among those with low CD4 cell counts, even though there is a higher risk of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome.4,22–25 This evidence endorses the current WHO recommendations that ART be used for all individuals with TB, regardless of their CD4 count, as soon as possible within the first 8 weeks of ATT and as early as within 2 weeks if the CD4 count is <50 cells/mm3.26 However, the evidence for these effects is not consistent with some studies that show no significant differences in survival between early and late initiation of ART.27,28 The findings from our study, in which nearly half the patients had a CD4 count <100 cells/mm3, are in line with these observations. It is likely that in the routine setting other patient factors, such as access to the clinic, financial security, clinical condition and patient readiness, play a part in determining treatment outcomes.

Third, in the ART-first group, around 40% started ATT within 3 months. This suggests that TB might have been prevalent at the time of starting ART, with the disease being missed at the initial screening because of the difficulties in establishing a diagnosis of TB in the context of severe immunosuppression or the disease being subclinical and becoming unmasked during immune reconstitution. ART failure may also have been a reason for TB developing after 3 months of ART initiation. It is well known that patients who develop TB soon after starting ART are at higher risk of mortality.29

Our study concurs with these observations, although the association was confounded by severe immunosuppression. These findings do, however, suggest that better, more sensitive tests are required to diagnose TB in severely immune-suppressed patients. Rapid, sensitive tests such as Xpert® MTB/RIF (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and/or urine TB lipoarabinomannan (LAM) have been found to be useful in detecting prevalent TB among HIV patients with advanced disease, and these should be considered as part of the diagnostic package in these patients.14,15 The Mandalay IHC, in collaboration with the NTP, started initiating Xpert testing for HIV patients in 2013. This is a step in the right direction.

There are some important policy recommendations from this study. First, routine data collection must be improved so that all variables that should be collected are actually collected. Second, routine measurement of haemoglobin in patients with TB-HIV would be useful, with moderate/severe anaemia being used to identify those at risk for TB among HIV-infected patients and those at risk of poor outcomes among TB-HIV patients, who might need closer and more frequent clinical monitoring. Third, the IHC programme should strongly consider the scale-up of Xpert testing for HIV patients and the deployment and use of urine LAM to diagnose TB much earlier than is probably the case. Finally, there is scope to get more patients initiated on early ART. The rapid advice issued by the WHO in September 2015 recommended that all persons with HIV start ART, regardless of CD4 cell count and WHO clinical stage.30 There is strong evidence that this approach reduces mortality and risk of TB,31,32 and this would help to reduce TB incidence and TB mortality in patients living with HIV. In this regard, there is also good evidence that the addition of isoniazid preventive therapy to ART can further reduce the risk of TB and other adverse outcomes,32,33 and should be considered as part of the package.

In conclusion, the study found generally good treatment outcomes in patients with TB-HIV enrolled for care in the IHC programme in Mandalay, Myanmar. Although unsuccessful outcomes were more common in patients starting ART before ATT, the timing of ART in relation to ATT was not an independent risk factor. The issues identified in this study need to be addressed for the programme to achieve the target of ending the epidemic of TB and HIV by 2030 in line with the recently released Sustainable Development Goals.34

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted through the Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative (SORT IT), a global partnership led by the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases at the World Health Organization (WHO/TDR). The model is based on a course developed jointly by the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union), Paris, France, and Medécins Sans Frontières (MSF), Brussels Operational Centre, Luxembourg. The specific SORT IT programme that resulted in this publication was jointly developed and implemented by The Union South-East Asia Regional Office, New Delhi, India; the Centre for Operational Research, The Union; the Operational Research Unit (LUXOR), MSF; the School of Public Health, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India; and the Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education & Research, Puducherry, India.

The programme was funded by the Department for International Development, London, UK. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none declared.

In accordance with WHO's open-access publication policy for all work funded by WHO or authored/co-authored by WHO staff members, the WHO retains the copyright of this publication through a Creative Commons Attribution IGO license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/legalcode) which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium provided the original work is properly cited.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report, 2015. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2015. WHO/HTM/TB/2015.22. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. WHO policy on collaborative TB/HIV activities. Guidelines for national programmes and other stakeholders. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2012. WHO/HTM/TB/2012.1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNAIDS. Myanmar Global AIDS Response progress report 2014. National AIDS Programme. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanc F-X, Sok T, Laureillard D et al. Earlier versus later start of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected adults with tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1471–1481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Havlir D V, Kendall M A, Ive P et al. Timing of antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 infection and tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1482–1491. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karim S S A, Naidoo K, Grobler A et al. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral drugs during tuberculosis therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1492–1501. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Treatment of tuberculosis: WHO guidelines. 4th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2010. WHO/HTM/TB/2009.420. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National AIDS Programme, Myanmar Ministry of Health. Guidelines for the clinical management of HIV infection in adults and adolescents in Myanmar. 3rd ed. Yangon, Myanmar: Myanmar Ministry of Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thida A, Tun S T T, Zaw S K K et al. Retention and risk factors for attrition in a large public health ART program in Myanmar: a retrospective cohort analysis. PLOS ONE. 2014;9:e108615. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents. Recommendations for a public health approach: 2010 revision. Geneva, Switzerland: 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2011. WHO/NMH/NHD/MNM/11.1. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363:157–163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Von Elm E, Altman D G, Egger M et al. The Strengthening The Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerkhoff A D, Wood R, Vogt M, Lawn S D. Predictive value of anemia for tuberculosis in HIV-infected patients in sub-Saharan Africa: an indication for routine microbiological investigation using new rapid assays. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66:33–40. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawn S D, Kerkhoff A D, Vogt M, Wood R. HIV-associated tuberculosis: relationship between disease severity and the sensitivity of new sputum-based and urine-based diagnostic assays. BMC Med. 2013;11:231. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kerkhoff A D, Wood R, Cobelens F G, Gupta-Wright A, Bekker L G, Lawn S D. Resolution of anaemia in a cohort of HIV-infected patients with a high prevalence and incidence of tuberculosis receiving antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:3860. doi: 10.1186/s12879-014-0702-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maruza M, Albuquerque M F, Braga M C et al. Survival of HIV-infected patients after starting tuberculosis treatment: a prospective cohort study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:618–624. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawn S D, Harries A D, Anglaret X, Myer L, Wood R. Early mortality among adults accessing antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2008;22:1897–1908. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830007cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagu T J, Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E et al. Anaemia at initiation of tuberculosis therapy is associated with delayed sputum conversion among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Dares-Salaam, Tanzania. PLOS ONE. 2014;9:e91229. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Odone A, Amadasi S, White R G, Cohen T, Grant A D, Houben R M. The impact of antiretroviral therapy on mortality in HIV positive people during tuberculosis treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. 2014;9:e112017. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naidoo K, Grobler A C, Deghaye N et al. Cost-effectiveness of initiating antiretroviral therapy at different points in TB treatment in HIV-TB coinfected ambulatory patients in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69:576–584. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schiffer J T, Sterling T R. Timing of antiretroviral therapy initiation in tuberculosis patients with AIDS: a decision analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:229–234. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802e2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naidoo K, Baxter C, Abdool Karim S S. When to start antiretroviral therapy during tuberculosis treatment. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2014;26:35–42. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32835ba8f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdool Karim S S, Naidoo K, Grobler A et al. Integration of antiretroviral therapy with tuberculosis treatment. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1492–1501. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laureillard D, Marcy O, Madec Y et al. Paradoxical tuberculosis-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome after early initiation of antiretroviral therapy in a randomized clinical trial. AIDS. 2013;27:2577–2586. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000432456.14099.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han S H, Zhou J, Lee M P et al. Prognostic significance of the interval between the initiation of antiretroviral therapy and the initiation of anti-tuberculosis treatment in HIV/tuberculosis-coinfected patients: results from the TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database. HIV Med. 2014;15:77–85. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang C-H, Chen K-J, Tsai J-J et al. The impact of HAART initiation timing on HIV-TB co-infected patients, a retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:304. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koenig S P, Riviere C, Leger P et al. High mortality among patients with AIDS who received a diagnosis of tuberculosis in the first 3 months of antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:829–831. doi: 10.1086/597098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization. Guideline on when to start antiretroviral therapy and on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.INSIGHT START Study Group. Lundgren J D, Babiker A G et al. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV Infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:795–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.TEMPRANO ANRS 12136 Study Group. Danel C, Moh R et al. A trial of early antiretrovirals and isoniazid preventive therapy in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:808–822. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rangaka M X, Wilkinson R J, Boulle A et al. Isoniazid plus antiretroviral therapy to prevent tuberculosis: a randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;384:682–690. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60162-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization. Health in 2015 from Millennium Development Goals (MDG) to Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2015. [Google Scholar]