Abstract

Background

We investigated self-perceived cognitive deficits and their relationship with internalized stigma and quality of life in patients with schizophrenia in order to shed light on the clinical correlates of subjective cognitive deficits in schizophrenia.

Methods

Seventy outpatients with schizophrenia were evaluated. Patients’ self-perceived cognitive deficits, internalized stigma, and subjective quality of life were assessed using the Scale to Investigate Cognition in Schizophrenia (SSTICS), the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Scale (ISMI), and the Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale Revision 4 (SQLS-R4), respectively. Correlation and regression analyses controlling for the severity of symptoms of schizophrenia were performed, and a mediation analysis was conducted to examine the hypothesis that internalized stigma mediates the relationship between self-perceived cognitive deficits and subjective quality of life.

Results

Pearson’s partial correlation analysis showed significant correlations among the SSTICS, ISMI, and SQLS-R4 scores (P<0.01). Multiple regression analysis showed that the SSTICS and ISMI scores significantly predicted the SQLS-R4 score (P<0.01). Mediation analysis revealed that the strength of the association between the SSTICS and SQLS-R4 scores decreased from β=0.74 (P<0.01) to β=0.56 (P<0.01), when the ISMI score was statistically controlled. The Sobel test revealed that this difference was significant (P<0.01), indicating that internalized stigma partially mediated the relationship between self-perceived cognitive deficits and quality of life.

Conclusion

The present study indicates that self-perceived cognitive deficits are significantly associated with internalized stigma and quality of life. Furthermore, internalized stigma was identified as a partial mediator of the relationship between self-perceived cognitive deficits and quality of life. These findings suggest that clinicians should be aware that patients with schizophrenia experience significantly greater self-stigma when they suffer subjective cognitive deficits, and that this may further compromise their quality of life.

Keywords: subjective cognitive deficits, internalized stigma, quality of life, schizophrenia

Introduction

Self-perceived cognitive deficits are subjective disturbances that primarily affect memory, attention, and executive function, and have been reported since the earliest description of dementia praecox.1,2 Unlike objective psychopathology that can be measured using interviewer-rated scales, subjectively experienced deficits are difficult to quantify and the reliability of the measurements is often questioned; accordingly, self-perceived cognitive deficits have been relatively neglected in research.3

In recent years, several different scales have been developed to measure subjective cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia with sufficient reliability and validity and have been reported to have utility in investigating compromised cognitive constructs in schizophrenia.4–6 These efforts have yielded a renewed interest in the research and clinical aspects of self-perceived cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Self-perceived cognitive deficits have been reported to play a substantial role in vulnerability,1 symptom severity,3,7 treatment compliance,8 functional outcome,9 and status of remission10 in patients with schizophrenia. In addition, the exploration of subjective cognitive symptoms may provide a foundation for helping patients to avoid maladaptive coping responses in favor of more appropriate coping strategies.11

At present, the clinical correlates of subjective cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia have not been sufficiently investigated and warrant further exploration. In particular, the relationship between subjective cognitive deficits and internalized stigma that has been reported to significantly affect various functional outcomes including quality of life12–14 remains unexplored. It has been considered that patients with schizophrenia internalize the stigma associated with illness and experience lowered self-esteem, which results in substantially diminished quality of life.14,15 Moreover, internalized stigma has been reported to play an important mediating or moderating role in the relationship between key clinical variables in schizophrenia.16,17 For example, previous studies found internalized stigma to be a significant mediator or moderator in the relationship between insight and social functioning and between symptom severity and quality of life.16,17

Given that cognitive dysfunction is an inherent component of the symptoms of schizophrenia, and that certain subjective experiences serve as specific fundamental features of schizophrenia,2,3,18 it can be hypothesized that self-perceived cognitive deficits are one of the important variables associated with internalized stigma experienced by patients with schizophrenia. Furthermore, internalized stigma may play an important role as a mediator in the relationship between self-perceived cognitive deficits and reduced quality of life. Therefore, in the present study, we investigated self-perceived cognitive deficits and their relationship with internalized stigma and quality of life in stable outpatients with schizophrenia in order to further shed light on the characteristics of subjective cognitive deficits and their clinical correlates in schizophrenia.

Materials and methods

Subjects

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Gachon University Gil Medical Center, and all procedures used in the study were conducted in accordance with international ethical standards as per the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects after a full explanation of the study procedure. The criteria for patient recruitment were as follows: 1) a diagnosis of schizophrenia by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition,19 which was established using the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition;20 2) age between 20 and 50 years; 3) outpatients on at least 4 weeks of maintenance therapy with atypical antipsychotics without changes in the dosage of medications over the same period; and 4) be able to be rated reliably on psychiatric rating scales. Patients were excluded if they: 1) met the diagnostic criteria for a psychiatric disorder other than schizophrenia; 2) had a concurrent diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence; 3) had a history of head trauma with loss of consciousness; or 4) had concurrent medical or neurological disorders.

Seventy outpatients (33 males, 37 females) were enrolled in the study. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects are presented in Table 1. Subjects had a mean age of 35.8±10.4 years and a mean duration of illness of 7.1±2.8 years. The mean years of education were 11.9±2.1 years. All subjects were chronic patients with one or two relapses and were receiving maintenance treatment with atypical antipsychotics. Twenty-eight patients (40.0%) had a single relapse and 42 patients (60.0%) had two relapses. None of the patients was taking antidepressants or mood stabilizers. The antipsychotics that patients were taking at the time of enrollment were paliperidone (n=29, mean dose: 6.2±2.4 mg/day), olanzapine (n=17, mean dose: 10.9±5.3 mg/day), aripiprazole (n=13, mean dose: 9.0±4.8 mg/day), clozapine (n=7, mean dose: 242.9±100.7 mg/day), and quetiapine (n=4, mean dose: 337.5±85.3 mg/day).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects (n=70)

| Variables | Mean ± SD/number (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 35.8±10.4 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 33 (47.1) |

| Female | 37 (52.9) |

| Duration of illness (years) | 7.1±2.8 |

| Education (years) | 11.9±2.1 |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 36 (51.4) |

| Married | 34 (48.6) |

| Manchester scale score | 9.1±7.8 |

| CDSS score | 5.7±5.4 |

| SSTICS score | 18.9±14.3 |

| ISMI score | 61.7±15.5 |

| SQLS-R4 score | 75.9±26.8 |

Abbreviations: CDSS, Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia; ISMI, Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Scale; SD, standard deviation; SQLS-R4, Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale Revision 4; SSTICS, Scale to Investigate Cognition in Schizophrenia.

Assessments

Self-perceived cognitive deficits were assessed using the Scale to Investigate Cognition in Schizophrenia (SSTICS).4 The SSTICS is a self-rating scale with a 5-point Likert-type format that ranges from 0 (never) to 4 (very often), and consists of 21 items concerning a wide range of subjective cognitive deficits in the domains of memory, attention, executive function, language, and praxis. The total score (range: 0–84) is calculated as the sum of all items, such that a higher score is associated with a greater self-perception of cognitive deficits.4,7,21 The SSTICS scores have been found to be significantly correlated with objective neuropsychological test results.4

Patients’ subjective experience of stigma was assessed using the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Scale (ISMI).22 The ISMI is a 29-item self-rating questionnaire that measures five aspects of self-stigma including alienation, stereotype endorsement, discrimination experience, social withdrawal, and the level of stigma resistance. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), with the five items of stigma resistance being reverse coded. A higher score is indicative of greater perception of internalized stigma.22–24 We used the total ISMI score for the analysis of the present study.

Patients’ quality of life was assessed using the Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale Revision 4 (SQLS-R4).25 The SQLS-R4 is a self-administered scale comprising 33 items. The SQLS-R4 is a schizophrenia-specific quality-of-life instrument that measures quality of life according to the patients’ perspective. All except four items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale (0= never, 1= rarely, 2= sometimes, 3= often, and 4= always), with the exceptional four items being reverse-coded, and the total score is calculated. A lower score represents a better quality of life, while a higher score indicates a lower quality of life.25–29 Previous studies have shown sufficient internal consistency and construct validity of the SQLS-R4.27–29 The SQLS-R4 has been increasingly used in different populations of patients with schizophrenia.30,31

The symptoms of schizophrenia were evaluated using the Manchester scale (MS).32 The MS is a widely used clinician-rated instrument for assessing psychiatric symptoms in schizophrenia. Scores are summed across items rated on a 5-point Likert scale.32–35 It consists of eight items measuring a broad range of symptoms: delusion, hallucination, incoherence, flattened affect, poverty of speech, psychomotor retardation, depression, and anxiety. The positive symptom score is defined as the sum of the scores for delusion, hallucination, and incoherence, and the negative symptom score is defined as the sum of the scores for flattened affect, poverty of speech, and psychomotor retardation. The depression/anxiety symptom score represents the sum of the scores for depression and anxiety.32–35 The severity of depressive symptoms was also assessed using the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS),36 which is the most widely used clinician-rated scale for assessing depression in schizophrenia.36,37

Each patient was administered a baseline interview and was evaluated using the MS and the CDSS by an investigator who was sufficiently trained and familiar with the assessment of psychiatric symptoms in schizophrenia.38–40 Each patient was then assessed using the SSTICS, ISMI, and SQLS-R4 in the presence of a research assistant who monitored whether or not the questions were completely understood.

Data analysis and statistical methods

Pearson’s partial correlation analysis was performed between SSTICS, ISMI, and SQLS-R4 scores, controlling for the severity of symptoms measured by the MS and CDSS. Multiple regression analysis was performed with SQLS-R4 score as the dependent outcome variable and the SSTICS and ISMI scores as independent variables in order to examine the impact of self-perceived cognitive deficits and internalized stigma on quality of life. In the multiple regression analysis, variables were entered in two stages. First, the SSTICS and ISMI scores were entered. Second, the MS and CDSS scores were added. At each stage of the multiple regression analysis, the variables were entered simultaneously. The MS sum score was used in the multiple regression analysis, while subscale scores were used in the correlation analysis.

In addition, we performed a mediation analysis using the Sobel test41 in order to examine the hypothesis that the relationship between self-perceived cognitive deficits and subjective quality of life is mediated by internalized stigma. For all analyses, the level of statistical significance was defined as P<0.01 (two-tailed). The level of P<0.05 (two-tailed) was considered a statistical tendency. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

The results in Table 2 show that demographic variables (age, sex, years of education, marital status, duration of illness, and number of relapses) had no significant correlations with SSTICS, ISMI, or SQLS-R4 scores (r=−0.09 to 0.16, P>0.01). The type of antipsychotics, which patients were taking at the time of the assessment, was also not significantly associated with SSTICS, ISMI, or SQLS-R4 scores (rho =−0.15 to 0.03, P>0.01).

Table 2.

Correlations of SSTICS, ISMI, and SQLS-R4 scores with demographic and clinical variables

| Variables | SSTICS score | ISMI score | SQLS-R4 score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.08 | 0.04 | −0.05 |

| Sex | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.09 |

| Education | 0.16 | −0.01 | −0.05 |

| Marital status | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.01 |

| Duration of illness | −0.06 | 0.03 | −0.08 |

| Number of relapses | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.08 |

| Antipsychoticsa | 0.03 | −0.15 | −0.12 |

| Manchester scale | |||

| Positive symptom score | 0.25* | 0.21 | 0.20 |

| Negative symptom score | 0.22 | 0.25* | 0.22 |

| Depression/anxiety symptom score | 0.42** | 0.35** | 0.43** |

| CDSS score | 0.56** | 0.54** | 0.58** |

Notes:

P<0.05.

P<0.01. Data are presented as Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients (rho, two-tailed) (for sex, marital status, and antipsychotics) and Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r, two-tailed) (for the other variables).

The type of antipsychotics that patients were taking at the time of the assessment.

Abbreviations: CDSS, Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia; ISMI, Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Scale; SQLS-R4, Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale Revision 4; SSTICS, Scale to Investigate Cognition in Schizophrenia.

With respect to the MS scores, the SSTICS, ISMI, and SQLS-R4 scores had no significant correlations with the MS-positive symptom score (r=0.20 to 0.25, P>0.01) or MS-negative symptom score (r=0.22 to 0.25, P>0.01) (Table 2). The SSTICS and ISMI scores tended to be correlated with the MS-positive symptom (r=0.25, P=0.04) and negative symptom (r=0.25, P=0.04) scores (Table 2). The SSTICS, ISMI, and SQLS-R4 scores had significant correlations with the MS depression/anxiety symptom score (SSTICS: r=0.42, P<0.01; ISMI: r=0.35, P<0.01; SQLS-R4: r=0.43, P<0.01) (Table 2). The SSTICS, ISMI, and SQLS-R4 scores also had significant correlations with CDSS score (SSTICS: r=0.56, P<0.01; ISMI: r=0.54, P<0.01; SQLS-R4: r=0.58, P<0.01) (Table 2).

There were significant intercorrelations between the SSTICS, ISMI, and SQLS-R4 scores. Pearson’s partial correlation analysis controlling for the severity of symptoms measured by the MS and CDSS showed significant correlations between the scores of all scales (SSTICS and ISMI: r=0.49, P<0.01; SSTICS and SQLS-R4: r=0.62, P<0.01; ISMI and SQLS-R4: r=0.72, P<0.01). Table 3 shows the results of the multiple regression analysis. At the first stage, the SSTICS and ISMI scores significantly predicted the SQLS-R4 score (P<0.01). At the second stage, the results were essentially unchanged in that SSTICS and ISMI scores were found to significantly predict the SQLS-R4 score (P<0.01) (Table 3). The MS and CDSS scores were not significant predictors (P>0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multiple regression analysis with SQLS-R4 as the dependent variable and SSTICS, ISMI, MS, and CDSS scores as independent variables

| Step | B | Standard error | β | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||

| (Constant) | 2.189 | 7.466 | ||

| SSTICS | 0.712 | 0.154 | 0.379 | <0.01 |

| ISMI | 0.977 | 0.143 | 0.563 | <0.01 |

| 2 | ||||

| (Constant) | 4.965 | 7.780 | ||

| SSTICS | 0.640 | 0.164 | 0.341 | <0.01 |

| ISMI | 0.918 | 0.149 | 0.529 | <0.01 |

| MS | −0.297 | 0.493 | −0.053 | 0.55 |

| CDSS | 0.862 | 0.628 | 0.142 | 0.17 |

Abbreviations: CDSS, Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia; ISMI, Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Scale; MS, Manchester scale; SQLS-R4, Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale Revision 4; SSTICS, Scale to Investigate Cognition in Schizophrenia.

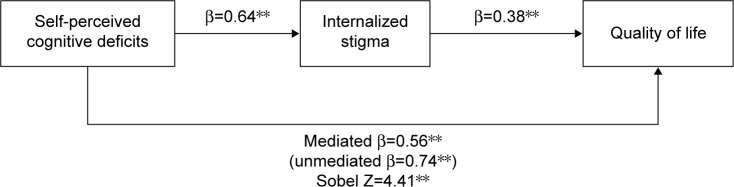

The results of the mediation analysis are presented in Figure 1. There were significant associations between the SSTICS and SQLS-R4 scores (β=0.74, P<0.01) and between the SSTICS and ISMI scores (β=0.64, P<0.01). The results of the regression analysis revealed a significant association between the ISMI and SQLS-R4 scores when the SSTICS was statistically controlled (β=0.38, P<0.01) (Figure 1). The strength of the association between the SSTICS and SQLS-R4 scores decreased from β=0.74 (P<0.01) to β=0.56 (P<0.01) when the ISMI score was statistically controlled. The Sobel test revealed that the difference was significant (Z=4.41, P<0.01), indicating that internalized stigma partially mediated the relationship between self-perceived cognitive deficits and quality of life (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The results of the mediation analysis using the Sobel test.

Note: **P<0.01.

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated self-perceived cognitive deficits and their relationship with internalized stigma and quality of life in outpatients with schizophrenia in order to shed light on the clinical correlates of subjective cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. The main findings of the present study are that self-perceived cognitive deficits are significantly associated with internalized stigma and quality of life and that internalized stigma partially mediates the relationship between self-perceived cognitive deficits and quality of life. To the best of our knowledge, this is among the first reports to evaluate the relationship between subjective cognitive deficits, internalized stigma, and quality of life in patients with schizophrenia.

In our study, the SSTICS score was significantly correlated with the ISMI score, even after controlling for the severity of symptoms of schizophrenia. These results suggest that, independent of symptom severity, the self-perception of limited cognitive function is strongly associated with a greater experience of self-stigma, which may ultimately decrease a patient’s sense of self-efficacy and social adaptation. Consistent with previous findings,7,42 depressive/anxiety symptoms were also strongly associated with subjective cognitive deficits. Patients with more severe depressive/anxiety symptoms may be more likely to ascribe their difficulties to cognitive deficits.7 Alternatively, difficulties associated with cognitive dysfunction may result in emotional discomforts or they may share a common pathophysiological basis.43 It should be noted that the SSTICS score showed a significant positive correlation with the SQLS-R4 score. Since a lower SQLS-R4 score represents a better quality of life and a higher score indicates a lower quality of life, these results indicate an inverse relationship between subjective cognitive deficits and quality of life in schizophrenia. This finding is in agreement with previous reports that patients’ perception of cognitive impairments has a significant negative impact on quality of life.44

The inverse relationship between internalized stigma and quality of life is consistent with previous reports that self-stigma is significantly negatively correlated with subjective well-being or quality of life in schizophrenia.12–14,45–47 Our finding, along with previous reports, suggests that effective interventions should be developed and implemented at various levels to reduce the influence of internalized stigma on subjective recovery and function.48 In addition, we found that the ISMI score was strongly associated with depressive/anxiety symptoms, which is consistent with previous findings on strong and mutual influences between depressive symptoms and self-stigma.48–50

Notably, the results of our mediation analysis revealed that internalized stigma partially mediates the relationship between self-perceived cognitive deficits and quality of life. These results may support a model in which self-perceived cognitive deficits affect internalized stigma, and internalized stigma subsequently affects quality of life, although subjective cognitive deficits and internalized stigma independently exert significant influences on quality of life. Previous studies have suggested that internalized stigma is an important mediator between clinical and outcome variables in patients with schizophrenia.16 Our study extends these findings to include the relationship between self-perceived cognitive deficits and quality of life. However, because of the cross-sectional nature of the present study, this mediation model requires further validation in a prospective study.

A recent meta-analysis showed that educational interventions combined with other intervention modalities are associated with a reduction in public or personal stigma.51 However, no firm evidence has demonstrated the effectiveness of these interventions for reducing perceived or self-stigma.51 Considering that metacognitive capacity is an important factor that facilitates stigma resistance, metacognitively oriented therapy or metacognitive reflective insight therapy may promote subjective forms of recovery and improvements in quality of life.52 The development of effective therapeutics for improving stigma resistance is clearly required to help patients with schizophrenia live a more fulfilling and satisfactory life.53,54

In addition, clinicians should pay greater attention to the domain of subjective cognitive dysfunction, given its substantial impact on self-stigma and quality of life. Future research should identify factors that predict subjective cognitive deficits in order to bolster evaluations of these self-perceived deficits, and furthermore effective pharmacological and nonpharmacological strategies should be developed to control these factors.7 Moreover, research has mainly focused on the issue of symptom unawareness and subsequent nonadherence to treatment; however, the present study shows that awareness of cognitive deficits plays a significant role in internalized stigma and diminished quality of life. These factors may explain the high suicide rates in patients with schizophrenia.

The interpretation of the results of the present study should be considered in light of some limitations. This was a cross-sectional study in a naturalistic clinical setting. Given the relatively small sample size, correlation coefficients from multiple regression and mediation analysis may have tended to overestimate associations and need to be interpreted carefully.55 A prospective study with a larger sample is warranted to confirm the stability of the relationships identified herein. The subjects were all outpatients receiving stable doses of antipsychotics; as such, the findings may not be generalized to a more diverse group of patients. Future studies should include more diverse samples such as drug-free patients in order to determine whether the relationship observed in the present study holds true for those patients. In the present study, we used a self-rating scale in order to assess quality of life. The use of an observer-rated quality-of-life scale might have led to different results.

Conclusion

The results of our study indicate that self-perceived cognitive deficits are significantly associated with internalized stigma and quality of life and that internalized stigma partially mediates the relationship between self-perceived cognitive deficits and quality of life in patients with schizophrenia. Our findings suggest that clinicians should be aware that patients with schizophrenia experience significantly greater self-stigma when they suffer subjective cognitive deficits and that this may further compromise their quality of life. Effective interventions should be developed and implemented to reduce the influence of self-perceived cognitive deficits and internalized stigma on subjective recovery and function in patients with schizophrenia.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI14C2750), and by the Gachon University Research Fund (grant number: GCU-2015-5031).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Schultze-Lutter F. Subjective symptoms of schizophrenia in research and the clinic: the basic symptom concept. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(1):5–8. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klosterkötter J, Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S. Kraepelin and psychotic prodromal conditions. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;258(Suppl 2):74–84. doi: 10.1007/s00406-008-2010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim JH, Byun HJ, Ann JH, Lee J. Relationship between subjective experiences and psychopathological dimensions in schizophrenia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(10):952–957. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2010.495940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stip E, Caron J, Renaud S, Pampoulova T, Lecomte Y. Exploring cognitive complaints in schizophrenia: the subjective scale to investigate cognition in schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2003;44(4):331–340. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00086-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Homayoun S, Nadeau-Marcotte F, Luck D, Stip E. Subjective and objective cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia – is there a link? Front Psychol. 2011;2:148. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moritz S, Lambert M, Andresen B, Böthern A, Naber D, Krausz M. Subjective cognitive dysfunction in first-episode and chronic schizophrenic patients. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42(3):213–216. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.23144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sellwood W, Morrison AP, Beck R, Heffernan S, Law H, Bentall RP. Subjective cognitive complaints in schizophrenia: relation to antipsychotic medication dose, actual cognitive performance, insight and symptoms. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e83774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naber D, Lambert M, Karow A. Subjective well-being under antipsychotic treatment and its meaning for compliance and course of disease. Psychiatr Prax. 2004;31(Suppl 2):S230–S232. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-828486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verdoux H, Monello F, Goumilloux R, Cougnard A, Prouteau A. Self-perceived cognitive deficits and occupational outcome in persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178(2):437–439. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naber D. Subjective effects of antipsychotic drugs and their relevance for compliance and remission. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2008;17(3):174–176. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00001238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peralta V, Cuesta MJ. Subjective experiences in schizophrenia: a critical review. Compr Psychiatry. 1994;35(3):198–204. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(94)90192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park SG, Bennett ME, Couture SM, Blanchard JJ. Internalized stigma in schizophrenia: relations with dysfunctional attitudes, symptoms, and quality of life. Psychiatry Res. 2013;205(1–2):43–47. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang IC, Wu HC. Quality of life and self-stigma in individuals with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Q. 2012;83(4):497–507. doi: 10.1007/s11126-012-9218-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sibitz I, Amering M, Unger A, et al. The impact of the social network, stigma and empowerment on the quality of life in patients with schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26(1):28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watson AC, Corrigan P, Larson JE, Sells M. Self-stigma in people with mental illness. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(6):1312–1318. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lysaker PH, Roe D, Yanos PT. Toward understanding the insight paradox: internalized stigma moderates the association between insight and social functioning, hope, and self-esteem among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(1):192–199. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan KK, Mak WW. The mediating role of self-stigma and unmet needs on the recovery of people with schizophrenia living in the community. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(9):2559–2568. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0695-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakaya M, Kusumoto K, Ohmori K. Subjective experiences of Japanese inpatients with chronic schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190(2):80–85. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200202000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders Research Version (SCID-I) New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson I, Tabbane K, Dellagi L, Kebir O. Self-perceived cognitive functioning does not correlate with objective measures of cognition in schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52(6):688–692. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ritsher JB, Otilingam PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Res. 2003;121(1):31–49. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim WJ, Song YJ, Ryu HS, et al. Internalized stigma and its psychosocial correlates in Korean patients with serious mental illness. Psychiatry Res. 2015;225(3):433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoo T, Kim SW, Kim SY, et al. Relationship between suicidality and low self-esteem in patients with schizophrenia. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(3):296–301. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2015.13.3.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilkinson G, Hesdon B, Wild D, et al. Self-report quality of life measure for people with schizophrenia: the SQLS. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:42–46. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim JH, Lee S, Han AY, Kim K, Lee J. Relationship between cognitive insight and subjective quality of life in outpatients with schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:2041–2048. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S90143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuo PJ, Chen-Sea MJ, Lu RB, et al. Validation of the Chinese version of the Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale Revision 4 (SQLS-R4) in Taiwanese patients with schizophrenia. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(9):1533–1538. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9262-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin CR, Allan R. Factor structure of the Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale Revision 4 (SQLS-R4) Psychol Health Med. 2007;12(2):126–134. doi: 10.1080/13548500500407383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim JH, Yim SJ, Min SK. The Korean version of the 4th Revision of Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale: validation study and relationship with PANSS. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2006;45(5):401–410. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chou CY, Yang TT, Ma MC, Teng PR, Cheng TC. Psychometric validations and comparisons of schizophrenia-specific health-related quality of life measures. Psychiatry Res. 2015;226(1):257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rouillon F, Eriksson L, Burba B, Raboch J, Kaprinis G, Schreiner A. Functional recovery results from the risperidone long-acting injectable versus quetiapine relapse prevention trial (ConstaTRE) Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2013;25(5):297–306. doi: 10.1017/neu.2013.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krawiecka M, Goldberg D, Vaughan M. A standardized psychiatric assessment scale for rating chronic psychotic patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1977;55(4):299–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1977.tb00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manchanda R, Saupe R, Hirsch SR. Comparison between the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale and the Manchester Scale for the rating of schizophrenic symptoms. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1986;74(6):563–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1986.tb06285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jackson HJ, Burgess PM, Minas IH, Joshua SD. Psychometric properties of the Manchester Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1990;81(2):108–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb06461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barnes TRE, Nelson HE. The Assessment of Psychoses: A Practical Handbook. London: Chapman & Hall Medical; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Addington D, Addington J, Maticka-Tyndale E. Assessing depression in schizophrenia: the Calgary Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1993;22:39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Addington J, Shah H, Liu L, Addington D. Reliability and validity of the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS) in youth at clinical high risk for psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2014;153(1–3):64–67. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim JH, Jung HY, Kang UG, et al. Metric characteristics of the drug-induced extrapyramidal symptoms scale (DIEPSS): a practical combined rating scale for drug-induced movement disorders. Mov Disord. 2002;17(6):1354–1359. doi: 10.1002/mds.10255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim JH, Kim SY, Lee J, Oh KJ, Kim YB, Cho ZH. Evaluation of the factor structure of symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2012;197(3):285–289. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim JH, Son YD, Kim JH, et al. Serotonin transporter availability in thalamic subregions in schizophrenia: a study using 7.0-T MRI with [(11)C]DASB high-resolution PET. Psychiatry Res. 2015;231(1):50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2014.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological Methodology. Washington DC: American Sociological Association; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bayard S, Capdevielle D, Boulenger JP, Raffard S. Dissociating self-reported cognitive complaint from clinical insight in schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24(4):251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim JH, Lee BC, Park HJ, et al. Subjective emotional experience and cognitive impairment in drug-induced akathisia. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43(6):456–462. doi: 10.1053/comp.2002.35908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caqueo-Urízar A, Boyer L, Baumstarck K, Gilman SE. Subjective perceptions of cognitive deficits and their influences on quality of life among patients with schizophrenia. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(11):2753–2760. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pérez-Garín D, Molero F, Bos AE. Internalized mental illness stigma and subjective well-being: the mediating role of psychological well-being. Psychiatry Res. 2015;228(3):325–331. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mashiach-Eizenberg M, Hasson-Ohayon I, Yanos PT, Lysaker PH, Roe D. Internalized stigma and quality of life among persons with severe mental illness: the mediating roles of self-esteem and hope. Psychiatry Res. 2013;208(1):15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mosanya TJ, Adelufosi AO, Adebowale OT, Ogunwale A, Adebayo OK. Self-stigma, quality of life and schizophrenia: an outpatient clinic survey in Nigeria. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2014;60(4):377–386. doi: 10.1177/0020764013491738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yanos PT, Lysaker PH, Roe D. Internalized stigma as a barrier to improvement in vocational functioning among people with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178(1):211–213. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schrank B, Amering M, Hay AG, Weber M, Sibitz I. Insight, positive and negative symptoms, hope, depression and self-stigma: a comprehensive model of mutual influences in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2014;23(3):271–279. doi: 10.1017/S2045796013000322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lysaker PH, Vohs J, Hasson-Ohayon I, Kukla M, Wierwille J, Dimaggio G. Depression and insight in schizophrenia: comparisons of levels of deficits in social cognition and metacognition and internalized stigma across three profiles. Schizophr Res. 2013;148(1–3):18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Griffiths KM, Carron-Arthur B, Parsons A, Reid R. Effectiveness of programs for reducing the stigma associated with mental disorders. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(2):161–175. doi: 10.1002/wps.20129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lysaker PH, Kukla M, Belanger E, et al. Individual psychotherapy and changes in self-experience in schizophrenia: a qualitative comparison of patients in metacognitively focused and supportive psychotherapy. Psychiatry. 2015;78(4):305–316. doi: 10.1080/00332747.2015.1063916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sibitz I, Unger A, Woppmann A, Zidek T, Amering M. Stigma resistance in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(2):316–323. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bifftu BB, Dachew BA, Tiruneh BT. Stigma resistance among people with schizophrenia at Amanuel Mental Specialized Hospital Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional institution based study. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:259. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0259-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ioannidis JP. Why most discovered true associations are inflated. Epidemiology. 2008;19(5):640–648. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31818131e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]