Abstract

Introduction

Empathy in doctor-patient relationships is a familiar topic for medical scholars, and a crucial goal for medical educators. Nonetheless, there are persistent disagreements in the research literature concerning how best to evaluate empathy among physicians, and whether empathy declines or increases across medical education. Some researchers have argued that the instruments used to study “empathy” may not be measuring anything meaningful to clinical practice or to patient satisfaction.

Methods

We performed a systematic review to learn how empathy is conceptualized in medical education research. How do researchers define the central construct of empathy, and what do they choose to measure? How well do definitions and operationalizations match?

Results

Among the 109 studies that met our search criteria, 20% failed to define the central construct of empathy at all, and only 13% had an operationalization that was well-matched to the definition provided. The majority of studies were characterized by internal inconsistencies and vagueness in both the conceptualization and operationalization of empathy, constraining the validity and usefulness of the research. The methods most commonly used to measure empathy relied heavily on self-report and cognition divorced from action, and may therefore have limited power to predict the presence or absence of empathy in clinical settings. Finally, the large majority of studies treated empathy itself as a black box, using global construct measurements that are unable to shed light on the underlying processes that produce empathic response.

Discussion

We suggest that future research should follow the lead of basic scientific research that conceptualizes empathy as relational—an engagement between a subject and an object—rather than a personal quality that may be modified wholesale through appropriate training.

Introduction

Rationale

Empathy in doctor-patient relationships is a familiar topic for medical scholars, and a crucial goal for medical educators. Yet definitions of empathy are not consistent from one piece of scholarship to another, and sharp disagreement remains on some basic issues in the field.

Humanists, ethicists, and social scientists agree that empathy is critical—and very often lacking—in medical care. In his widely read book, The Silent World of Doctor and Patient, the ethicist Jay Katz1 examined the obstacles that prevent honest and empathic communication between physicians and the people they serve. Empathy is also a predictable theme in artistic depictions of medicine and medical training. Novels that portray the destruction of empathy, such as House of God, are handed down from one generation of medical students to the next, while the popular television show House, M.D. openly celebrates a doctor’s disregard for bedside manner, implicitly communicating that one can be a good doctor without mastering the interpersonal dimensions of the job.2 Such behavior is not confined to fiction: schooled in the hidden curriculum of clinical internships and residency, new doctors learn to mock certain groups of patients.3

While the development of empathy among medical trainees has been an important goal for medical educators, it has also been an intriguing conundrum for researchers: a substantial (if somewhat controversial) body of research has demonstrated that empathy typically decreases during medical training.4 Medical schools and medical associations take the problem seriously: the development of empathy in professional conduct is an explicit goal of both the American Association of Medical Colleges and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Yet despite a host of intervention strategies, “medical education still seems surprisingly ineffective in helping students walk a mile in their patients’ shoes.”5 This persistent problem has led some researchers to suggest that the problem is selection, rather than treatment—that medical schools must find ways to identify and recruit students who are more empathic or have better communication skills to begin with. The assumption underlying such proposals seems to be that empathy is a personal and relatively immutable characteristic: one either has it, or one does not.

Other researchers question whether this much-lamented empathy decline is actually real, pointing to problems in study design and instrumentation.6 Two recent reviews of changes in empathy among medical students and residents reached disparate conclusions. In a systematic review, Neumann and colleagues found that empathy declines during medical training as students engage more with patients.7 Colliver and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis drawing on much of the same research and concluded that declines in empathy during medical training are minimal, perhaps even nonexistent.6 This second group also argued that the instruments used to study “empathy” may not be measuring anything meaningful to clinical practice or to patient satisfaction. (For example, most past research has utilized student self-assessments, which may be an ineffective way to measure empathy.) The discrepancy between these two reviews poses serious concerns for researchers and educators seeking to maximize empathy in medical practice. Furthermore, although there is controversy over the effect of medical training on empathy, there is relatively little controversy surrounding the need for more empathic medical practice; under such circumstances, it would be unfortunate to take solace in the possibility that empathy does not decline during medical training.

Objectives

To foster better and more useful research on empathy in medical training, we designed a systematic review to learn how empathy is defined and operationalized in medical education research—how do researchers define the central construct of empathy, and what do they choose to measure?—as well as how well definitions compare to the operationalizations used. Our review is unusual in that it focuses on the conceptualization of empathy in empirical research studies, rather than the results of those studies. Certain features common to most systematic reviews, such as a consideration of bias in the reporting and interpretation of results, are therefore not appropriate for our review. Whereas most systematic reviews and meta-analyses focus on the methods and results of empirical research, we believe that conceptual and definitional issues that precede methodological decisions are key to understanding the state of the field—that an incomplete, poorly articulated understanding of empathy is at the root of both the discordant results and the limited success in educational intervention. In this view, an analysis of the existing state of empathy definitions and operationalization is the first step to rethinking medical education research on empathy.

Methods

Information Sources and Search

We systematically queried the following databases for relevant English-language studies published before November 1, 2012: PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), Web of Science, PsycInfo, and Education Resource Information Center (ERIC). The following terms were used in combination to search all databases: professional education or clinical education or medical education; medical students, nursing students, psychology students, and dental students; empathy or empathi*. With the guidance of a library science expert, we added search terms tailored to each database. Synonyms for each of the above terms used in specific databases were also searched. For more details on the search strategies used within each database, see Appendix 1.

Eligibility Criteria

For this systematic review, we included English-language publications that (1) examined physicians, medical students or residents, (2) operationalized empathy in an empirical study, and (3) included some quantitative component. Under the guidance of our library science expert, we included all studies published before November 1, 2012 and did not exclude articles published before any particular time point. The time range of publications does vary for each database and is noted in Appendix 1. While our initial search terms included non-physician health care personnel, we ultimately excluded studies in which the study’s main focus was not physicians or physician trainees. We also excluded editorials or essays that lacked an empirical component, and publications for which our librarians could not locate a full-text article. We elected to include only studies that had a quantitative component. This necessarily removes many high quality studies from consideration of how empathy is being assessed in medical education.

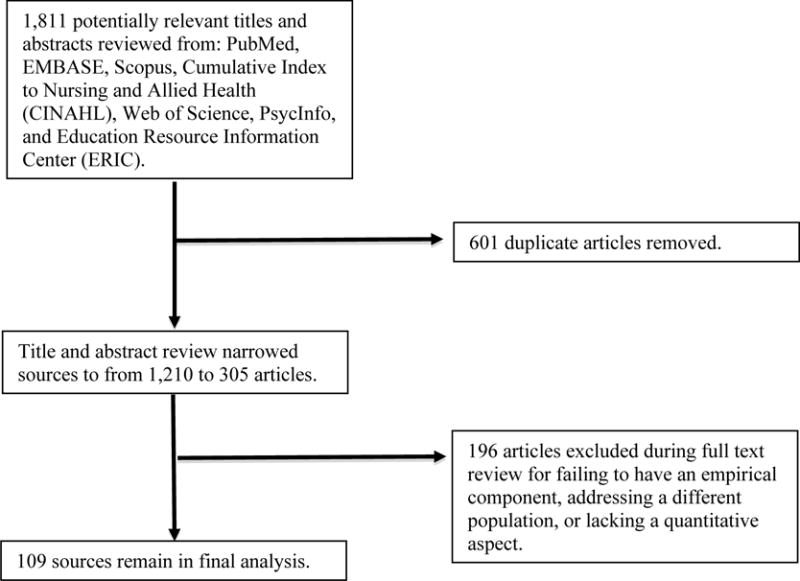

Study Selection: Title and Abstract Review

Our initial search yielded 1,811 articles. After removing duplicates, 1,210 articles remained. The first author (S.S.) and a trained research assistant independently reviewed the title and abstracts of each article for appropriate population and subject area, which resulted in a total of 305 articles. Any articles the reviewers disagreed on or that lacked sufficient information were included for full text review.

Data Collection Process and Data Items

For the remaining 305 articles, the full text was examined for goodness of fit with the study criteria. 196 additional publications were excluded based on this review, leaving 109 articles.4,8–115 Subsequently, the following information was extracted from each remaining article: the definition of empathy (if present), and whether the definition incorporated thinking, feeling, acting or more than one of these components. Additionally, we extracted the means by which empathy was operationalized, including the scales, questionnaires, or other mechanisms used to measure empathy when these could be identified. We also coded articles for the party evaluating empathy: self, patient, or other. Two authors (S.S. and C.W.) each coded full-text articles, and resolved discrepancies by reaching a consensus.

Data Analysis and Summary Measures

We entered the above data categories into an Excel file, and calculated descriptive statistics for each variable. We analyzed the presence or absence of empathy definitions, and the complexity and variation in definitions in relation to various forms of operationalization. As noted above, our central questions concerned the strength of the conceptual foundations on which this body of research has been built, rather than the research designs within which concepts of empathy have been deployed. Therefore, we deemed it inappropriate to evaluate study strength through meta-analytic measures. The approach we used instead provides a comparison of the underlying conceptual frameworks within empathy research in medical education.

Results

Definition of Empathy

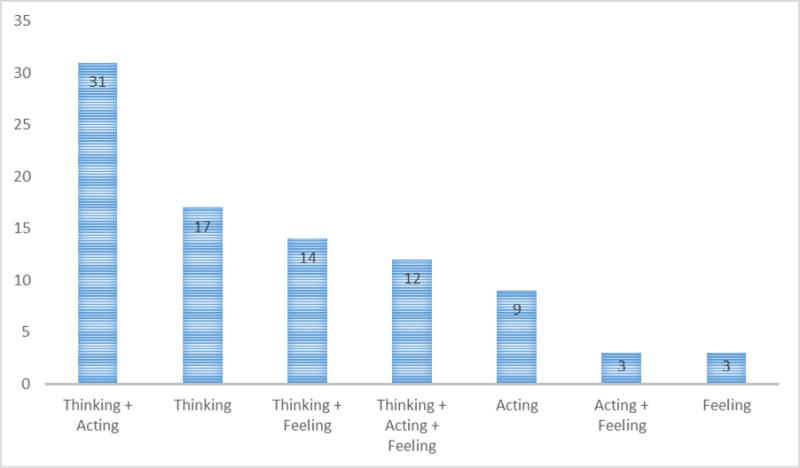

Other authors have noted that there is little consensus on definitions of empathy.116 Those definitions that exist may emphasize cognitive, emotional, or behavioral elements—or some combination thereof. In our review, 22 of 109 articles (20%) included no definition of empathy at all. For the 87 articles that did provide definitions, we coded whether those definitions included elements related to thinking, feeling, or acting. A definition could incorporate one, two, or all three elements, and we included verbal communications under the rubric of “acting.” A list of words used to identify thinking, feeling, and action can be found in Appendix 2. Seventy-four articles (82% of articles providing a definition) defined empathy as consisting in part or entirely of a cognitive, thinking process. Thirty-two (37%) defined empathy as consisting in part or entirely of a feeling process. And 53 (61%) defined empathy as including an action component. Overall, the majority of definitions included components from more than one domain (see Figure 2). Thinking or cognitive processes were the most prevalent component of empathy definitions, and present in the top four categories. Feeling or affective processes are the least prevalent in definitions.

Figure 2.

Frequency of Components in Empathy Definitions

Operationalization of Empathy

All of the studies included in our sample (109) operationalized empathy in the sense that every study sought to measure, assess, or evaluate it in some way. Ninety-five (87%) used some sort of scalar tool to evaluate empathy, and 43 (39%) used a non-scalar tool (for instance, asking patients to describe physicians’ empathy). Twenty-nine studies (27%) used both. The most common scalar instrument was the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy (JSPE). Forty-five (41%) studies used either the JSPE or the JSPE-Student Version. Nineteen (17%) used the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI). Five (5%) used the Hogan Empathy Scale. The Balanced Emotional Empathy Scale (BEES), the Barrett-Lennard Scale, the Accurate Empathy Scale and the Consultation and Relational Empathy Measure (CARE) were each used four times (4% for each). More than a dozen other scales were used more rarely, typically in a single study.

Assignment of Empathy

We evaluated who determined the presence or absence of empathy in the context of each study. Studies most commonly used self-report: 66 of 109 (61%) used only self-reporting tools, while an additional thirteen articles used self-report in combination with another source of evaluation. In total, 79 used self-report (72%), 18 relied on patient or standardized-patient reports (17%), and 28 (26%) used a third-party report such as that of a faculty member, a trained observer, or a peer. Few studies (fourteen, or 13% of the total) used reports from multiple perspectives, typically combining self-report with that of an observer.

Empathy as a Construct

To assess operationalization, we examined each instrument used to quantify empathy, to identify whether it assessed physicians’ (or trainee physicians’) cognitive processes, feelings, or behaviors. In seven cases, we were unable to assess details of the scale used, because it was either proprietary or in a non-English language (despite publication of the study in English).

The same word list used to assess definitions was used to assess operationalizations (see Appendix 2). For instance, one study trained coders to examine videotaped encounters between physicians and patients; the coders counted several specific physician behaviors, both verbal (such as interrupting, supportive talk, etc.) and non-verbal (eye contact, silence, etcetera) and divided them by the total number of utterances in the encounter.25 This operationalization was coded as “acting.”

Finally, we extracted whether empathy was conceptualized as (a) a global construct to be measured in presence, absence or degree; or (b) a summation of multiple component parts. Among the papers for which we could assess details of operationalization, eighty operationalized empathy as a global construct (78%), and 45 (44%) operationalized empathy as a composite construct, as in the example above. Fifteen publications (15%) operationalized empathy in both ways.

Consistency between Definition and Operationalization

Rather than measuring the empirical quality of the studies, our conceptually focused analysis judged quality by assessing whether or not a study’s definition of empathy was aligned with how the authors chose to operationalize and evaluate empathy. Specifically, we compared our coding of the definitions of empathy with our coding for operationalizations of empathy. For example, several studies used the definition of empathy provided by Hojat and colleagues, developers of the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy: “a predominantly cognitive (as opposed to affective or emotional) attribute that involves an understanding (as opposed to feeling) of patients’ experiences, concerns, and perspectives combined with a capacity to communicate this understanding.”117p74 We coded this definition as including thinking and acting components, but not feeling. An examination of the items in the JSPE scale shows an extensive focus on thinking, with no items on action. A study that used this definition and operationalized it with the JSPE alone would be considered non-matching. Each study in the database for which we could assess operationalization was coded in this way. Studies that did not include a definition were automatically rated as non-matching. Only 13 of 102 studies (13%) had matching operationalizations and definitions across these dimensions.

Discussion

Summary of Evidence

Empirical studies on empathy in medical education, though increasingly common, are still outnumbered by commentaries. Furthermore, our analysis reveals that many of these studies are characterized by internal inconsistencies and vagueness in both the conceptualization and operationalization of empathy, limiting the validity and usefulness of the research.

One-fifth of the studies in our sample failed to define the central construct of empathy, either (a) relying on commonsense notions of empathy, or (b) using a scale or other instrument as a de facto definition of empathy. Relying on commonsense ideas presumes a consensus about the definition and characteristics of empathy that is notably absent from the literature. Using a measurement tool as an implicit definition is problematic because it is the construct definition that enables other scholars to judge whether a particular instrument is appropriate and the resulting claims are valid.

All of the studies that defined empathy incorporated at least one of the three domains thinking, feeling, and acting, although there was no consensus about which of these were the key components. Twelve studies (14%) integrated all three dimensions. For example, Shanafelt and colleagues defined empathy as “the ability to listen to a patient, understand their perspective, sympathize with their experience, and express understanding, respect, and support.”96 Another 51 (59%) included two dimensions, most commonly thinking and acting (34, or 39%). Thus, in a 2004 paper Hojat and colleagues defined empathy as “a cognitive attribute that involves an understanding of the inner experiences and perspectives of the patient as a separate individual, combined with a capability to communicate this understanding to the patient.”118p935 Only a quarter of the studies that defined empathy included its feeling dimension—and some quite specifically excluded it—despite the etymological origins of empathy in “feeling in” or “feeling with.”

A surprising majority of studies contained internal contradictions, with definitions that focused on different dimensions (i.e., thinking, feeling, and acting) than the accompanying scales or research instruments. Of the 81 studies that defined empathy, and whose instruments we were able to access and code, only 11 studies (14%) defined and operationalized empathy consistently.

Looking across all studies included in the review, our analysis reveals that the methods used to study empathy have limited power to predict the presence or absence of empathy in clinical settings. The most common instruments for measuring empathy rely on self-report, which as Colliver and colleagues remind us, is only loosely correlated with behavior.6 Furthermore, many instruments place a heavy emphasis on cognition—thoughts related to empathy. The best research on medical thought and clinical judgment has always paired cognition with its action consequences because the predictive value of cognition alone is limited.119 In short, by focusing on what doctors and medical trainees self-report, and especially on the thoughts that they report, existing research on empathy offers a tenuous connection to clinical settings.

This research focuses on the conceptual quality of empirical research on empathy in medical education, and as such is only half of the story. It should ideally be read in the context of other research, such as that done by Colliver and colleagues, that sheds light on the technical quality of research in the field. Furthermore, by omitting studies that lacked a clear quantitative component, we present a somewhat narrow view of research in the field. Although excluding purely qualitative research removed many potentially high-quality studies from our sample, we believe our focus on quantitative and mixed-methods studies is justified by both the influential role of quantitative research in the medical education literature (as exemplified by the two prominent reviews described above) and the particular problems of operationalizing a complex variable in quantitative research. Finally, given the widespread heterogeneity in approaches, our analysis was limited in its ability to deeply explore the characteristics of any specific subset of approach.

Conclusions

The various conceptual flaws noted above—lack of definition, mismatch between definition and operationalization, an over-reliance on cognition and self-report—raise significant challenges to the validity of research on empathy in medical education.

Our greatest concern, however, is the degree to which empirical studies treat empathy itself as a black box, and are thus incapable of shedding light on the mechanisms that underlie clinician empathy. Most studies (61%) assessed empathy solely through self-assessment by clinicians or students, an operationalization that presumes it to be a quality inherent in the individual and independent of any given relationship. Nearly two thirds of the studies in this review operationalized empathy solely as a global construct that increases or decreases monolithically, rather than something with interacting component parts. Should educators focus on cognitive or affective interventions to enhance clinician empathy? Without understanding the underlying mechanisms, we cannot know. Furthermore, it is entirely possible that there are multiple pathways leading to empathic response. Research into the mechanisms of clinician empathy is needed to help medical educators guide students to a better understanding of their own strengths.

Basic scientific research (including evolutionary psychology and primate studies) offers some leads that medical social science might follow in investigating the underlying mechanisms of empathy.14 Rather than a personal quality that may be modified wholesale through appropriate training, this research suggests that empathy is relational–an engagement between a subject and an object. Furthermore, this research suggests that empathy favors individuals who we perceive as similar to ourselves.8 Shielding oneself from identifying with another—a widely noted consequence of medical education—may actually reduce empathy.15 This hypothesis requires in-depth investigation—yet if confirmed, it would reveal a far-reaching problem with medical education. It is challenges like these that research on empathy should strive to identify and address. Understanding the mechanisms that shape empathy in the doctor-patient relationship deserves more careful attention.

Figure 1.

Systematic Review Inclusion Process

Appendix 1: Search Terms

-

PubMED search: (Education, professional OR “Professional Education” OR “Medical Students” OR “Nursing Students” OR “Psychology Students”) AND (Empathy OR Empathi*)

183 articles found.

MeSH Term: “Professional Education”

Date: 1887 (UNC Library site)

-

EMBASE search: (Medical Education OR Clinical Education OR Medical School OR “Medical Students” OR “Nursing Students” OR “Psychology Students”) AND (Empathy OR Empathi*)

465 articles found.

Emtree for “Professional Education” resulted in the substitution for Medical Education, Clinical Education, and Medical School.

EMBASE has been indexed since 1947.

-

Scopus search: (Education, professional OR “Professional Education” OR “Medical Education” OR “Medical Students” OR “Dental Students” OR “Nursing Students” OR “Psychology Students”) AND (Empathy OR Empathi*)

794 articles found.

Date: 1996 (UNC Library cite)

-

CINAHL search: (“Clinical Education” OR “Health Sciences Education” OR “Medical Education” OR “Professional Education” OR “Medical Students” OR “Dental Students” OR “Nursing Students” OR “Psychology Students”) AND (Empathy OR Empathi*)

48 articles found.

Headings

Support website said 1937, but UNC Library site said 1982.

-

Web of Science search: (“Health Sciences Education” OR “Medical Education” OR “Clinical Education” OR “Professional Education” OR “Medical Students” OR “Dental Students” OR “Nursing Students” OR “Psychology Students”) AND (Empathy OR Empathi*)

80 articles found.

Date: 1955 (UNC Library site)

-

PsycInfo search: (“Health Sciences Education” OR “Medical Education” OR “Clinical Education” OR “Professional Education” OR “Medical Students” OR “Dental Students” OR “Nursing Students” OR “Psychology Students”) AND (Empathy OR Empathi*)

228 articles found.

Headings

Date: 1887 (UNC Library site)

-

ERIC search: (“Health Sciences Education” OR “Medical Education” OR “Clinical Education” OR “Professional Education” OR “Medical Students” OR “Dental Students” OR “Nursing Students” OR “Psychology Students”) AND (Empathy OR Empathi*)

13 articles found.

No mesh terms, just field term

Indexing and abstracting since 1966.

Appendix 2: Coding Terms

(Note: Two authors (SS and CW) brainstormed this list of terms before coding began. In each case, cognates were also included. In most cases, definitions using these terms explicitly referred to cognitive, behavioral, or affective components to which they were linked.)

THINKING

Cognition

perspective-taking

imagination/imagining

apprehension

understanding

seeing

perceiving

processing

comprehend

appreciation of

knowledge

recognize

identification

controlled

intellectually sense

role-taking

grasp

identify with

FEELING

Compassion

feeling

emotion

concern

“joining with patient’s feelings”

to enter into or join with feelings

socio-emotional

care

emotional participation

affective

vicarious emotional response

generation of similar feelings

sharing of emotions

sense

emotional contagion

sympathize

match/experience someone’s emotional state

emotive

specific feeling words: e.g. angry, enjoy, care, sad, etcetera

ACTION

Communication

Conveying

behavioral

express

listen

interrupt

eye contact

Appendix 3: Table of Extracted Codes

| Coding of Definitions | Coding of Operationalizations | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Last Name of First Author | Thinking | Feeling | Acting | No Definition | Scalar | Non Scalar | Thinking | Feeling | Acting | Self-report | Patient Assess | Other 3rd Party | Global Empathy | Composite Empathy |

| 2011 | Berg | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 1985 | Jarski | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2007 | Chen | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2013 | Costa | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2007 | Austin | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2007 | West | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2011 | Abreu | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2012 | Garroutte | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 2010 | Michalec | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2004 | Hojat | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 1988 | Jarski | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 1982 | Malpiede | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2010 | Wimmers | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 1996 | Yarnold | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 1998 | Colliver | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 2001 | Gallagher | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 2011 | Lim | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 2012 | Paro | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2009 | Spiegel | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 2013 | Consoli | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2008 | Stratton | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2013 | Kondo | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 2012 | Chen | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2009 | Crandall | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2008 | Harlak | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2012 | Dehning | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2010 | Chen | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2004 | Fields | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 1996 | Carmel | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2004 | Easter | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 2007 | Hojat | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2013 | Chang | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 1974 | Charles | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2009 | Bunn | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2007 | Neumann | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2013 | Imran | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2005 | Tai t | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 1998 | Kliszcz | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 2005 | Stratton | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2002 | Bylund | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2011 | Hojat | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 1988 | Hornblow | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2013 | Lelorai n | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2007 | Wickramasekera | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2001 | Bailey | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 1982 | Elizur | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1977 | Fine | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 2013 | Goncalves-Pereira | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 1992 | Higgins | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 2005 | Hojat | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2011 | Hojat | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 1984 | Hong | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2011 | Magalhaes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 1996 | Ogle | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 2008 | Rahimi-Madiseh | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2008 | Shariat | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2010 | Tavakol | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2013 | Hojat | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 1993 | Tamburrino | 1 | 1 | * | * | * | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2000 | Winefield | 1 | 1 | * | * | * | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2011 | Baykan | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | * | * | * | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2005 | Bylund | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2013 | Lim | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2007 | Thomas | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2011 | Rosenthal | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2009 | Bonvicini | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 2008 | Fernandez-Olano | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 1989 | Kramer | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 2000 | Morton | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2008 | Newton | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 1980 | Poole | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 2012 | Kataoka | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 1993 | Evans | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2011 | Berg | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 2008 | Morse | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 2005 | Bellini | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2008 | Bonvicini | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | * | * | * | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 2003 | Hojat | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2011 | Pollak | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 2001 | DeCoster | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2011 | Hojat | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2011 | Tavakol | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2005 | Shanafelt | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 2007 | Glaser | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2005 | Hojat | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2010 | Colliver | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2013 | Preusche | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2000 | Switzer | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 1980 | Sanson-Fisher | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2011 | Faye | 1 | 1 | 1 | * | * | * | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2013 | Batt-Rawden | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2009 | Hojat | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2012 | Passalacqua | 1 | 1 | 1 | * | * | * | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2011 | Weng | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2004 | Kim | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2011 | Neumann | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2007 | Nicolai | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2009 | Di | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2001 | Hojat | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2012 | Suh | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 2012 | Canale | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 1979 | Christiansen | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2009 | Spreng | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2011 | Bayne | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2013 | Garcia | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 1978 | Sanson-Fisher | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| 2007 | Silvester | 1 | 1 | 1 | * | * | * | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2002 | Bellini | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 2013 | Newton | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| TOTALS | 74 | 32 | 53 | 22 | 95 | 43 | 75 | 75 | 55 | 79 | 18 | 28 | 82 | 43 | |

References

- 1.Katz J. The Silent World of Doctor and Patient. New York: Free Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strauman EC, Goodier BC. The doctor(s) in House: an analysis of the evolution of the television doctor-hero. J Med Humanit. 2011;32:31–46. doi: 10.1007/s10912-010-9124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wear D, Aultman JM, Varley JD, Zarconi J. Making fun of patients: medical students’ perceptions and use of derogatory and cynical humor in clinical settings. Academic Medicine. 2006;81(5):454–462. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000222277.21200.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hojat M, Vergare MJ, Maxwell K, et al. The devil is in the third year: a longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Academic Medicine. 2009;84(9):1182–1191. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b17e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro J. Walking a mile in their patients’ shoes: empathy and othering in medical students’ education. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2008;3:10. doi: 10.1186/1747-5341-3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colliver JA, Conlee MJ, Verhulst SJ, Dorsey JK. Reports of the decline of empathy during medical education are greatly exaggerated: a reexamination of the research. Academic Medicine. 2010;85:588–593. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d281dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neumann M, Edelh„user F, Tauschel D, et al. Empathy decline and its reasons: a systematic review of studies with medical students and residents. Academic Medicine. 2011;86(8):1–14. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318221e615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abreu BC. Accentuate the positive: reflections on empathic interpersonal interactions. The American journal of occupational therapy: official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association. 2011;65(6):623–634. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2011.656002. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Austin EJ, Evans P, Magnus B, O’Hanlon K. A preliminary study of empathy, emotional intelligence and examination performance in MBChB students. Medical Education. 2007;41(7):684–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02795.x. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bailey BA. Empathy in medical students: Assessment and relationship to specialty choice. US: ProQuest Information & Learning; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Batt-Rawden SA, Chisolm MS, Anton B, Flickinger TE. Teaching empathy to medical students: An updated, systematic review. Academic Medicine. 2013;88(8):1171–1177. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318299f3e3. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baykan Z, Naçar M, Demirel SO. Evaluation of empathic skills and tendencies of medical students. Academic Psychiatry. 2011;35(3):207–208. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.35.3.207. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bayne HB. Training medical students in empathic communication. Journal for Specialists in Group Work. 2011 Dec;36(4):316–329. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bellini LM, Baime M, Shea JA. Variation of mood and empathy during internship. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002 Jun 19;287(23):3143–3146. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.23.3143. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellini LM, Shea JA. Mood change and empathy decline persist during three years of internal medicine training. Academic Medicine. 2005;80(2):164–167. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200502000-00013. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berg K, Majdan JF, Berg D, Veloski J, Hojat M. Medical students’ self-reported empathy and simulated patients’ assessments of student empathy: An analysis by gender and ethnicity. Academic Medicine. 2011;86(8):984–988. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182224f1f. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berg K, Majdan JF, Berg D, Veloski J, Hojat M. A comparison of medical students’ self-reported empathy with simulated patients’ assessments of the students’ empathy. Medical Teacher. 2011;33(5):388–391. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.530319. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonvicini KA. Physician empathy: Impact of communication training on physician behavior and patient perceptions. US: ProQuest Information & Learning; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonvicini KA, Perlin MJ, Bylund CL, Carroll G, Rouse RA, Goldstein MG. Impact of communication training on physician expression of empathy in patient encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75(1):3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.09.007. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bunn W, Terpstra J. Cultivating empathy for the mentally ill using simulated auditory hallucinations. Academic Psychiatry. 2009;33(6):457–460. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.33.6.457. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bylund CL, Makoul G. Empathic communication and gender in the physician-patient encounter. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(3):207–216. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00173-8. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bylund CL, Makoul G. Examining empathy in medical encounters: An observational study using the Empathic Communication Coding System. Health Communication. 2005;18(2):123–140. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1802_2. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Canale SD, Louis DZ, Maio V, et al. The relationship between physician empathy and disease complications: An empirical study of primary care physicians and their diabetic patients in Parma, Italy. Academic Medicine. 2012;87(9):1243–1249. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182628fbf. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carmel S, Glick SM. Compassionate-empathic physicians: personality traits and social-organizational factors that enhance or inhibit this behavior pattern. Social science & medicine (1982) 1996 Oct;43(8):1253–1261. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00445-9. 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang CL, Park BK, Kim SS. Conversational analysis of medical discourse in rehabilitation: A study in Korea. J Spinal Cord Med. 2013;36(1):24–30. doi: 10.1179/2045772312Y.0000000051. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charles CH. Correlates of adjudged empathy as early identifiers of counseling potential. US: ProQuest Information & Learning; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen D, Lew R, Hershman W, Orlander J. A cross-sectional measurement of medical student empathy. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22(10):1434–1438. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0298-x. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen DCR, Kirshenbaum DS, Yan J, Kirshenbaum E, Aseltine RH. Characterizing changes in student empathy throughout medical school. Medical Teacher. 2012;34(4):305–311. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.644600. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen DCR, Pahilan ME, Orlander JD. Comparing a self-administered measure of empathy with observed behavior among medical students. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25(3):200–202. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1193-4. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christiansen CH. The relationship between life history variables and measured empathic capacity in allied health students. US: ProQuest Information & Learning; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colliver JA, Conlee MJ, Verhulst SJ, Dorsey JK. Reports of the decline of empathy during medical education are greatly exaggerated: A reexamination of the research. Academic Medicine. 2010;85(4):588–593. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d281dc. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colliver JA, Willis MS, Robbs RS, Cohen DS, Swartz MH. Assessment of empathy in a standardized-patient examination. Teaching and Learning in Medicine. 1998;10(1):8–11. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Consoli SM, Airagnes G, de Morhlon O, Jaury P. Can appropriate training improve the empathic capacities of medical students? J Psychosom Res. 2013 Jun;74(6) doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.03.005. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costa P, Magalhães E, Costa MJ. A latent growth model suggests that empathy of medical students does not decline over time. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2013;18(3):509–522. doi: 10.1007/s10459-012-9390-z. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crandall SJ, Marion GS. Commentary: Identifying attitudes towards empathy: an essential feature of professionalism. Academic medicine: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2009 Sep;84(9):1174–1176. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b17b11. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeCoster VA, Egan M. Physicians’ perceptions and responses to patient emotion: Implications for social work practice in health care. Soc Work Health Care. 2001;32(3):21–40. doi: 10.1300/J010v32n03_02. 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dehning S, Girma E, Gasperi S, Meyer S, Tesfaye M, Siebeck M. Comparative cross-sectional study of empathy among first year and final year medical students in Jimma University, Ethiopia: Steady state of the heart and opening of the eyes. BMC Medical Education. 2012;12(1) doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-12-34. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Di Lillo M, Cicchetti A, Scalzo AL, Taroni F, Hojat M. The Jefferson scale of physician empathy: Preliminary psychometrics and group comparisons in Italian physicians. Academic Medicine. 2009;84(9):1198–1202. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b17b3f. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Easter DW, Beach W. Competent patient care is dependent upon attending to empathic opportunities presented during interview sessions. Current Surgery. 2004;61(3):313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.cursur.2003.12.006. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elizur A, Rosenheim E. Empathy and attitudes among medical students: The effects of group experience. Journal of Medical Education. 1982 Sep;57(9):675–683. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198209000-00003. 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Evans BJ, Stanley RO, Burrows GD. Measuring medical students’ empathy skills. The British journal of medical psychology. 1993 Jun;66(Pt 2):121–133. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1993.tb01735.x. 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Faye A, Kalra G, Swamy R, Shukla A, Subramanyam A, Kamath R. Study of emotional intelligence and empathy in medical postgraduates. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;53(2):140–144. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.82541. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fernández-Olano C, Montoya-Fernandez J, Salinas-Sánchez A. Impact of clinical interview training on the empathy level of medical students and medical residents. Medical Teacher. 2008;30(3):322–324. doi: 10.1080/01421590701802299. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fields SK, Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Mangione S, Kane G, Magee M. Comparisons of nurses and physicians on an operational measure of empathy. Eval Health Prof. 2004 Mar;27(1):80–94. doi: 10.1177/0163278703261206. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fine VK, Therrien ME. Empathy in the doctor-patient relationship: skill training for medical students. Journal of medical education. 1977 Sep;52(9):752–757. doi: 10.1097/00001888-197709000-00005. 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gallagher TJ, Hartung PJ, Gregory SW., Jr Assessment of a measure of relational communication for doctor-patient interactions. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;45(3):211–218. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00126-4. 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.García D, Bautista O, Venereo L, Coll O, Vassena R, Vernaeve V. Training in empathic skills improves the patient-physician relationship during the first consultation in a fertility clinic. Fertility and Sterility. 2013;99(5):1413–1418 e1411. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.12.012. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garroutte EM, Sarkisian N, Karamnov S. Affective interactions in medical visits: Ethnic differences among American Indian older adults. J Aging Health. 2012;24(7):1223–1251. doi: 10.1177/0898264312457410. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Glaser KM, Markham FW, Adler HM, McManus PR, Hojat M. Relationships between scores on the Jefferson Scale of physician empathy, patient perceptions of physician empathy, and humanistic approaches to patient care: a validity study. Medical science monitor: international medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 2007 Jul;13(7):CR291–294. 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goncalves-Pereira M, Trancas B, Loureiro J, Papoila A, Caldas-De-Almeida JM. Empathy as related to motivations for medicine in a sample of first-year medical students. Psychological Reports. 2013;112(1):73–88. doi: 10.2466/17.13.PR0.112.1.73-88. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harlak H, Gemalmaz A, Gurel FS, Dereboy C, Ertekin K. Communication skills training: effects on attitudes toward communication skills and empathic tendency. Education for health (Abingdon, England) 2008 Jul;21(2) 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Higgins HM. Empathy training and stress: Their role in medical students’ responses to emotional patients. US: ProQuest Information & Learning; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hojat M, Axelrod D, Spandorfer J, Mangione S. Enhancing and sustaining empathy in medical students. Medical teacher. 2013 Jun 11; doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.802300. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, Magee M. Physician empathy in medical education and practice: Experience with the Jefferson scale of physician empathy. Seminars in Integrative Medicine. 2003;1(1):25–41. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Academic Medicine. 2011;86(3):359–364. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182086fe1. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hojat M, Mangione S, Kane GC, Gonnella JS. Relationships between scores of the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy (JSPE) and the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) Medical Teacher. 2005;27(7):625–628. doi: 10.1080/01421590500069744. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hojat M, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, et al. The Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy: Development and preliminary psychometric data. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2001;61(2):349–365. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hojat M, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, Gonnella JS, Magee M. Empathy scores in medical school and ratings of empathic behavior in residency training 3 years later. Journal of Social Psychology. 2005 Dec;145(6):663–672. doi: 10.3200/SOCP.145.6.663-672. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hojat M, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, et al. An empirical study of decline in empathy in medical school. Medical Education. 2004;38(9):934–941. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01911.x. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hojat M, Paskin DL, Callahan CA, et al. Components of postgraduate competence: Analyses of thirty years of longitudinal data. Medical Education. 2007;41(10):982–989. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02841.x. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hojat M, Spandorfer J, Louis DZ, Gonnella JS. Empathic and sympathetic orientations toward patient care: conceptualization, measurement, and psychometrics. Academic medicine: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2011 Aug;86(8):989–995. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822203d8. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hojat M, Zuckerman M, Magee M, et al. Empathy in medical students as related to specialty interest, personality, and perceptions of mother and father. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;39(7):1205–1215. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hong M, Bahn GH, Lee WH, Moon SJ. Empathy in Korean psychiatric residents. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry. 2011;3(2):83–90. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hornblow AR, Kidson MA, Ironside W. Empathic processes: perception by medical students of patients’ anxiety and depression. Medical education. 1988 Jan;22(1):15–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1988.tb00403.x. 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Imran N, Aftab MA, Haider II, Farhat A. Educating tomorrow’s doctors: A cross sectional survey of emotional intelligence and empathy in medical students of lahore. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences. 2013;29(3) doi: 10.12669/pjms.293.3642. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jarski RW. An investigation of physician assistant and medical student empathic skills. J Allied Health. 1988 Aug;17(3):211–219. 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jarski RW, Gjerde CL, Bratton BD, Brown DD, Matthes SS. A comparison of four empathy instruments in simulated patient-medical student interactions. Journal of medical education. 1985 Jul;60(7):545–551. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198507000-00006. 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kataoka HU, Koide N, Hojat M, Gonnella JS. Measurement and correlates of empathy among female Japanese physicians. BMC Medical Education. 2012;12(1) doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-12-48. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim SS, Kaplowitz S, Johnston MV. The effects of physician empathy on patient satisfaction and compliance. Eval Health Prof. 2004;27(3):237–251. doi: 10.1177/0163278704267037. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kliszcz J, Rembowski J. Emotional and cognitive empathy in medical schools. Academic Medicine. 1998 May;73(5) doi: 10.1097/00001888-199805000-00025. 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kondo K, Fujimori M, Shirai Y, et al. Characteristics associated with empathic behavior in Japanese oncologists. Patient Educ Couns. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.06.023. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kramer D, Ber R, Moore M. Increasing empathy among medical students. Medical Education. 1989 Mar;23(2):168–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1989.tb00881.x. 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lelorain S, Sultan S, Zenasni F, et al. Empathic concern and professional characteristics associated with clinical empathy in French general practitioners. European Journal of General Practice. 2013;19(1):23–28. doi: 10.3109/13814788.2012.709842. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lim BT, Moriarty H, Huthwaite M. “Being-in-role”: A teaching innovation to enhance empathic communication skills in medical students. Medical Teacher. 2011;33(12):E663–E669. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.611193. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lim BT, Moriarty H, Huthwaite M, Gray L, Pullon S, Gallagher P. How well do medical students rate and communicate clinical empathy? Medical teacher. 2013;35(2):e946–951. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.715783. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Magalhães E, Costa P, Costa MJ. Empathy of medical students and personality: Evidence from the Five-Factor Model. Medical Teacher. 2012;34(10):807–812. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.702248. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Malpiede DM, Leff MG, Wilson KM, Moore VM. Assessing interaction between medical trainees and parents of pediatric patients. Journal of Medical Education. 1982;57(9):696–700. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198209000-00006. 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Michalec B. An Assessment of Medical School Stressors on Preclinical Students’ Levels of Clinical Empathy. Current Psychology. 2010;29(3):210–221. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Morse DS, Edwardsen EA, Gordon HS. Missed opportunities for interval empathy in lung cancer communication. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168(17):1853–1858. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.17.1853. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Morton KR, Worthley JS, Nitch SR, Lamberton HH, Loo LK, Testerman JK. Integration of Cognition and Emotion: A Postformal Operations Model of Physician-Patient Interaction. Journal of Adult Development. 2000;7(3):151–160. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Neumann M, Bensing J, Wirtz M, et al. The impact of financial incentives on physician empathy: A study from the perspective of patients with private and statutory health insurance. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84(2):208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.07.012. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Neumann M, Wirtz M, Bollschweiler E, et al. Determinants and patient-reported long-term outcomes of physician empathy in oncology: A structural equation modelling approach. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;69(1–3):63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.07.003. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Newton BW. Walking a fine line: is it possible to remain an empathic physician and have a hardened heart? Frontiers in human neuroscience. 2013:7. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00233. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Newton BW, Barber L, Clardy J, Cleveland E, O’Sullivan P. Is there hardening of the heart during medical school? Academic Medicine. 2008;83(3):244–249. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181637837. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nicolai J, Demmel R. The impact of gender stereotypes on the evaluation of general practitioners’ communication skills: An experimental study using transcripts of physician-patient encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;69(1–3):200–205. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.08.013. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ogle J, Bushnell JA, Caputi P. Empathy is related to clinical competence in medical care. Medical Education. 2013;47(8):824–831. doi: 10.1111/medu.12232. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Paro HBMS, Daud-Gallotti RM, Tibério IC, Pinto RM, Martins MA. Brazilian version of the Jefferson Scale of Empathy: Psychometric properties and factor analysis. BMC Medical Education. 2012;12(1) doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-12-73. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Passalacqua SA, Segrin C. The Effect of Resident Physician Stress, Burnout, and Empathy on Patient-Centered Communication During the Long-Call Shift. Health Communication. 2012;27(5):449–456. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.606527. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pollak KI, Alexander SC, Tulsky JA, et al. Physician empathy and listening: Associations with patient satisfaction and autonomy. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2011;24(6):665–672. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.06.110025. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Poole AD, Sanson-Fisher RW. Long-term effects of empathy training on the interview skills of medical students. Patient counselling and health education. 1980;2(3):125–127. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(80)80053-x. 1980 3d Quart. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Preusche I, Wagner-Menghin M. Rising to the challenge: Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation of the adapted German version of the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy for Students (JSPE-S) Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2013;18(4):573–587. doi: 10.1007/s10459-012-9393-9. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rahimi-Madiseh M, Tavakol M, Dennick R, Nasiri J. Empathy in Iranian medical students: A preliminary psychometric analysis and differences by gender and year of medical school. Medical Teacher. 2010;32(11):e471–e478. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.509419. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rosenthal S, Howard B, Schlussel YR, et al. Humanism at heart: Preserving empathy in third-year medical students. Academic Medicine. 2011;86(3):350–358. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318209897f. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sanson-Fisher RW, Poole AD. Training medical students to empathize: an experimental study. The Medical journal of Australia. 1978 May 06;1(9):473–476. 1978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sanson-Fisher RW, Poole AD. Simulated patients and the assessment of medical students’ interpersonal skills. Medical education 1980/07// 1980;14(4):249–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1980.tb02269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shanafelt TD, West C, Zhao X, et al. Relationship between increased personal well-being and enhanced empathy among internal medicine residents. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20(7):559–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0108.x. 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shariat SV, Habibi M. Empathy in Iranian medical students: Measurement model of the Jefferson Scale of Empathy. Medical Teacher. 2013;35(1):e890–e895. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.714881. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Silvester J, Patterson F, Koczwara A, Ferguson E. “Trust me..”: Psychological and behavioral predictors of perceived physician empathy. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(2):519–527. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.519. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Spiegel W, Zidek T, Maier M, et al. Breaking bad news to cancer patients: Survey and analysis. Psychooncology. 2009;18(2):179–186. doi: 10.1002/pon.1383. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Spreng RN, McKinnon MC, Mar RA, Levine B. The Toronto empathy questionnaire: Scale development and initial validation of a factor-analytic solution to multiple empathy measures. J Pers Assess. 2009;91(1):62–71. doi: 10.1080/00223890802484381. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Stratton T, Saunders J, Elam C. Changes in medical students’ emotional intelligence: an exploratory study. Teaching & Learning in Medicine. 2008 Jul;20(3):279–284. doi: 10.1080/10401330802199625. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Stratton TD, Elam CL, Murphy-Spencer AE, Quinlivan SL. Emotional intelligence and clinical skills: preliminary results from a comprehensive clinical performance examination. Academic medicine: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2005 Oct;80(10 Suppl):S34–37. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200510001-00012. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Suh DH, Hong JS, Lee DH, Gonnella JS, Hojat M. The Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy: A preliminary psychometric study and group comparisons in Korean physicians. Medical Teacher. 2012;34(6):e464–e468. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.668632. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Switzer CL. Service learning in a medical school: Psychosocial and attitudinal outcomes. US: ProQuest Information & Learning; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tait RC, Chibnall JT, Luebbert A, Sutter C. Effect of treatment success and empathy on surgeon attributions for back surgery outcomes. J Behav Med. 2005;28(4):301–312. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9007-6. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tamburrino MB, Lynch DJ, Nagel R, Mangen M. Evaluating empathy in interviewing: Comparing self-report with actual behavior. Teaching and Learning in Medicine. 1993;5(4):217–220. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tavakol S, Dennick R, Tavakol M. Psychometric properties and confirmatory factor analysis of the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy. BMC Medical Education. 2011;11(1) doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-11-54. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tavakol S, Dennick R, Tavakol M. Empathy in UK medical students: Differences by gender, medical year and specialty interest. Education for Primary Care. 2011;22(5):297–303. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2011.11494022. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Thomas MR, Dyrbye LN, Huntington JL, et al. How do distress and well-being relate to medical student empathy? A multicenter study. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22(2):177–183. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0039-6. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Weng HC, Steed JF, Yu SW, et al. The effect of surgeon empathy and emotional intelligence on patient satisfaction. Advances in Health Sciences Education. 2011;16(5):591–600. doi: 10.1007/s10459-011-9278-3. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.West CP, Huntington JL, Huschka MM, et al. A prospective study of the relationship between medical knowledge and professionalism among internal medicine residents. Academic Medicine. 2007;82(6):587–592. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180555fc5. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wickramasekera IE., Ii Empathic features of absorption and incongruence. Am J Clin Hypn. 2007;50(1):59–69. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2007.10401598. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wimmers PF, Stuber ML. Assessing medical students’ empathy and attitudes towards patient-centered care with an existing clinical performance exam (OSCE) 2010 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Winefield HR, Chur-Hansen A. Evaluating the outcome of communication skill teaching for entry-level medical students: Does knowledge of empathy increase? Medical Education. 2000;34(2):90–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00463.x. 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Yarnold PR, Bryant FB, Nightingale SD, Martin GJ. Assessing physician empathy using the Interpersonal Reactivity Index: A measurement model and cross-sectional analysis. Psychology, Health and Medicine. 1996;1(2):207–221. 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Spreng RN, McKinnon MC, Mar RA, Levine B. The Toronto Empathy Questionnaire: Scale development and initial validation of a factor-analytic solution to multiple empathy measures. J Pers Asess. 2009;91(1):62–71. doi: 10.1080/00223890802484381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hojat M, LaNoue M. Exploration and confirmation of the latent variable structure of the Jefferson scale of physician empathy. International Journal of Medical Education. 2014;5:73–81. doi: 10.5116/ijme.533f.0c41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hojat M, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, et al. An empirical study of decline in empathy in medical school. Medical Education. 2004;38:934–941. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Tversky A, Kahneman D. Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognit Psychol. 1973;5(2):207–232. 5(2), 207–232. Cognitive psychology. [Google Scholar]