Abstract

Introduction

COPD exacerbation negatively impacts the patient’s quality of life and lung function, increases mortality, and increases socioeconomic costs. In a real-world setting, the majority of patients with COPD have mild-to-moderate airflow limitation. Therefore, it is important to evaluate COPD exacerbation in patients with mild-to-moderate airflow limitation, although most studies have focused on the patients with moderate or severe COPD. The objective of this study was to evaluate factors associated with COPD exacerbation in patients with mild-to-moderate airflow limitation.

Methods

Patients registered in the Korean COPD Subtype Study cohort were recruited from 37 tertiary referral hospitals in Korea. We obtained their clinical data including demographic characteristics, past medical history, and comorbidities from medical records. Patients were required to visit the hospital to document their COPD status using self-administered questionnaires every 6 months.

Results

A total of 570 patients with mild-to-moderate airflow limitation were enrolled. During the first year of follow-up, 30.5% patients experienced acute exacerbation, with exacerbations being more common in patients with poor lung function. Assessed factors associated with COPD exacerbation included COPD assessment test scores, modified Medical Research Council dyspnea assessment test scores, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire for COPD scores, a previous history of exacerbation, and histories of pneumonia and allergic rhinitis. Logistic regression tests revealed St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire for COPD scores (odds ratio [OR], 1.02; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.00–1.04; P=0.034), a previous history of exacerbation (OR, 3.12; 95% CI, 1.35–7.23; P=0.008), and a history of pneumonia (OR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.06–3.25; P=0.032) as risk factors for COPD exacerbation.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that COPD exacerbation in patients with mild-to-moderate airflow limitation is associated with the patient’s quality of life, previous history of exacerbation, and history of pneumonia.

Keywords: COPD, exacerbation, risk factors

Introduction

Patients with COPD may experience acute exacerbations, which are defined as events characterized by a worsening of respiratory symptoms that is beyond normal day-to-day variations, necessitating a change in medications.1 COPD exacerbation is important because frequent acute exacerbations have a negative effect on the quality of life of patients2 and are one of the most common causes of hospitalization and mortality.3 Moreover, the frequency of exacerbations contributes to a long-term decline in lung function.4 From economic perspectives, acute exacerbation results in an increase in the economic and social burden.5 Regardless of the degree of airflow limitation, the known precipitating factors for acute exacerbation include viral or bacterial infection, and air pollutants, with no specific factors identified for approximately one-third of cases.1

It has been reported that mild-to-moderate airway obstruction (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease [GOLD] class 1 and 2) accounts for the majority of COPD patients in several prevalence studies on COPD.6–8 The exacerbation rate in these patients is 0.7–0.9/year, as estimated from large randomized controlled trials.1 However, few studies have evaluated the incidence of acute exacerbations and the associated risk factors in COPD patients with mild-to-moderate airflow limitation in real-world practice. The aim of this study was to determine factors associated with acute COPD exacerbations in patients with mild-to-moderate airflow limitation in actual clinical settings.

Materials and methods

Study participants

We enrolled COPD patients with mild-to-moderate airflow limitation from the Korean COPD Subtype Study (KOCOSS) cohort, which is a registry organized to clarify the clinical phenotype of COPD in Korea.9,10 Patients were recruited from 37 tertiary referral hospitals in Korea. The inclusion criteria for KOCOSS cohort were as follows: age ≥40 years, postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) <0.7, and the presence of respiratory symptoms such as cough, sputum, and dyspnea. We excluded patients receiving treatment for any respiratory diseases mimicking COPD, such as bronchiectasis, asthma, and tuberculosis-destroyed lungs. The definition of mild-to-moderate airflow limitation was adopted from the GOLD guidelines (FEV1 ≥50% of the predicted value).1 All patients included in this analysis were part of the patient dataset obtained on December 31, 2014.

Procedures

Clinical examinations and spirometry were performed to assess the severity of COPD in all patients. We used self-administered questionnaires to acquire demographic characteristics, past medical histories, and data related to comorbidities. Dyspnea and quality of life were assessed by the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) score, COPD assessment test (CAT), and St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire for COPD (SGRQ-c).11–13 Because there can be discrepancies between mMRC and CAT scores, we collected both data simultaneously.10 SGRQ-c is also a reliable, valid instrument to measure the self-reported quality of life in COPD patients. Therefore, we gathered data using three different questionnaires at baseline. Histories of exacerbation before enrollment were gathered at baseline. Exacerbation was defined in this study as worsening of one of the respiratory symptoms, such as an increase in sputum volume, purulence, or dyspnea, necessitating treatment with systemic corticosteroids, antibiotics, or both.9 Furthermore, when the exacerbation required a visit to the emergency room or hospitalization, it was defined as moderate or severe exacerbation, respectively.

The patients received appropriate treatment according to their COPD status. Prospective exacerbation data were collected according to the KOCOSS protocol. The patients were required to visit the hospital every 6 months, and spirometry was performed every year during the follow-up period. When patients could not visit the hospital, we contacted them by telephone to acquire data. During follow-up, the doctors assessed the disease status, conducted physical examinations, and asked patients to complete questionnaires. December 31, 2014 was used as the cutoff date for available longitudinal data. We gathered exacerbation data according to severity of airflow limitation and GOLD risk group and compared the baseline characteristics of patients stratified by the presence or absence of a previous acute exacerbation history.

Statistical analyses

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation where appropriate and were analyzed using SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) for Windows. Descriptive analyses were performed to assess differences in baseline characteristics between patients with and without exacerbation histories. We used chi-square tests and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables. In addition, we performed logistic regression analysis to determine the risk factors for COPD exacerbation. All P-values were two-sided, and values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Ethical statement

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethics and review board of each participating study center (Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital, IRB No 2012-I027). All patients provided written informed consent before participation.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 570 COPD patients with mild-to-moderate airflow limitation were enrolled in this study. The proportion of males was 90.4%, the mean follow-up duration was 22.3±21.4 months, and the mean age of patients was 69.8±7.8 years. A total of 114 (20%) patients had experienced acute exacerbation a year before enrollment. Furthermore, 90.7% patients exhibited moderate airflow limitation (GOLD 2), while the remaining exhibited mild airflow limitation (GOLD 1). According to the 2011 GOLD classification, 24.9% and 74.7% patients exhibited GOLD class A and B, respectively. The enrolled patients exhibited comorbidities, with hypertension being the most frequently encountered (37.9%). A total of 14.2% patients had a history of pneumonia. The patients’ baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included patients with COPD and mild-to-moderate airflow limitation

| Characteristics | Total (n=570) |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 69.8 (7.8) |

| Male, no (%) | 515 (90.4) |

| Follow-up duration (months), mean (SD) | 22.3 (21.4) |

| Lung function, mean (SD) | |

| Postbronchodilator FEV1 (L) | 1.79 (0.54) |

| Postbronchodilator FEV1 (% of predicted) | 66.0 (11.6) |

| Postbronchodilator FVC (L) | 3.28 (0.75) |

| Postbronchodilator FVC (% of predicted) | 87.4 (15.4) |

| Smoking amount (pack-years), mean (SD) | 43.8 (24.3) |

| Total CAT score, mean (SD) | 13.9 (6.9) |

| mMRC score, mean (SD) | 1.36 (0.85) |

| SGRQ-c, mean (SD) | 30.4 (6.5) |

| Number of patients with previous exacerbation history, no (%) | 114 (20) |

| Comorbidities, no (%) | |

| Hypertension | 37.9 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 14.3 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 10.4 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 8.3 |

| Osteoporosis | 3.8 |

| Congestive heart failure | 3.1 |

| Past medical history, no (%) | |

| Asthma | 65.4 |

| Tuberculosis | 22.1 |

| Measles | 17.4 |

| Pneumonia | 14.2 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 11.0 |

Abbreviations: CAT, COPD assessment test; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; SD, standard deviation; SGRQ-c, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire for COPD.

Experience of acute exacerbation

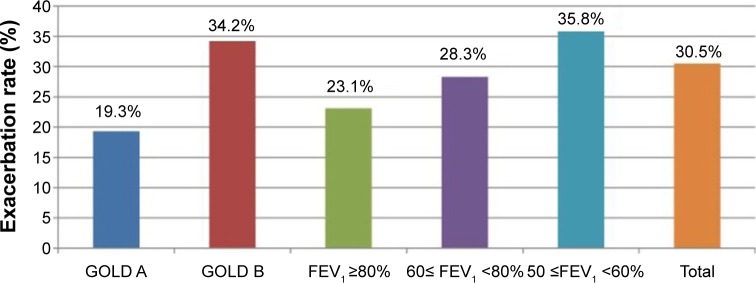

A total of 30.5% patients experienced acute exacerbation during the first year of follow-up. The estimated exacerbation rates were 23.1% for patients with an FEV1 of ≥80% of the predicted value, 28.3% for patients with an FEV1 of 60%–80% of the predicted value, and 35.8% for patients with an FEV1 of ≤60% of the predicted value (P=0.369). Using the new GOLD classification for comparisons, we found that 34.2% patients with GOLD class B developed exacerbation during the first year of follow-up, whereas only 19.3% patients with GOLD class A experienced exacerbation during this period (P=0.036; Figure 1). We showed the proportion of patients according to the exacerbation of COPD during the first year of follow-up in Figure S1. A total of 58.3% patients with a history of exacerbation before enrollment experienced exacerbation events during the first year of follow-up. Among the patients with exacerbation, 36.9% exhibited moderate or severe exacerbations (emergency room visit or hospital admission).

Figure 1.

Exacerbation rate of COPD according to the GOLD classification and severity of airflow limitation during the first year of follow-up.

Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.

Factors associated with acute exacerbation of COPD

We compared baseline characteristics between patients with COPD exacerbation and those without during the follow-up period and found that mean mMRC, CAT, and SGRQ-c scores were significantly higher for the former than for the latter (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline characteristics between patients with experience of COPD exacerbation and those without

| Variables | Experience of acute exacerbation | Non-experience of acute exacerbation | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 70.4±6.9 | 70.4±7.7 | 0.989 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.6±2.9 | 23.4±3.5 | 0.732 |

| mMRC score | 1.57±0.93 | 1.25±0.85 | 0.015 |

| SGRQ-c score | 37.9±2.00 | 28.1±1.6 | 0.000 |

| CAT score | 16.41±7.80 | 13.25±6.83 | 0.005 |

| Postbronchodilator FEV1 (L) | 1.69±0.44 | 1.80±0.48 | 0.102 |

| Postbronchodilator FEV1 (% of predicted) | 64.5±13.8 | 67.1±13.0 | 0.188 |

Notes: Data shown as mean ± standard deviation. An independent t-test was used to compare the two groups.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CAT, COPD assessment test; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; SGRQ-c, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire for COPD.

With regard to comorbidities, hyperlipidemia was more frequent in patients with exacerbation than in those without, while hypertension, diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, osteoporosis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease showed similar prevalences in both groups. Among the patients with exacerbation, histories of pneumonia and allergic rhinitis were more prevalent (Table 3). Multivariate analysis using a logistic regression model that included all associated variables revealed that the SGRQ-c score (odds ratio [OR], 1.02; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.00–1.04; P=0.034), a previous history of exacerbation (OR, 3.12; 95% CI, 1.35–7.23; P=0.008), and a history of pneumonia (OR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.06–3.25; P=0.032) were independently related to a higher risk of COPD exacerbation (Table 4).

Table 3.

Comparison of self-reported comorbidities and past medical histories between patients with a history of COPD exacerbation and those without

| Variables | Presence of acute exacerbation | Absence of acute exacerbation | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidities (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 40.6 | 39.9 | 0.203 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12.5 | 12.5 | 0.453 |

| Congestive heart failure | 3.1 | 4.9 | 0.392 |

| Osteoporosis | 3.1 | 2.8 | 0.249 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 7.8 | 11.9 | 0.419 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 5.7 | 3.1 | 0.018 |

| Past medical history (%) | |||

| Asthma | 62.9 | 71.6 | 0.143 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 27.4 | 10.8 | 0.008 |

| Pneumonia | 23.0 | 14.9 | 0.008 |

| Measles | 21.0 | 18.9 | 0.475 |

| Tuberculosis | 19.4 | 22.3 | 0.110 |

Note: A chi-square test was used to compare the two groups.

Table 4.

Logistic regression model for the risk factors for COPD exacerbation

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Previous exacerbation history | 3.12 (1.35–7.23) | 0.008 |

| History of pneumonia | 1.85 (1.06–3.25) | 0.032 |

| SGRQ-c score | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.034 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 1.15 (0.61–2.19) | 0.667 |

| mMRC | 1.07 (0.66–1.75) | 0.777 |

| CAT score | 1.00 (0.93–1.07) | 0.883 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.82 (0.52–1.30) | 0.384 |

Abbreviations: CAT, COPD assessment test; CI, confidence interval; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; OR, odds ratio; SGRQ-c, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire for COPD.

Discussion

In the present study, we showed that 30.5% COPD patients with mild-to-moderate airflow limitation experienced acute exacerbation in the first year of follow-up. When compared according to baseline FEV1 levels, 23.1% patients with an FEV1 of ≥80% of the predicted value (mild COPD) and 64.1% with an FEV1 of 50%–80% of the predicted value (moderate COPD) experienced exacerbation. The risk of exacerbation is known to increase with an increase in the degree of airflow limitation.1 The estimated annual exacerbation rate from several medium-term studies has been reported to range from 0.5 to 3.5 per patient per year, regardless of the severity of airflow limitation.14–16 Furthermore, the annual rate of exacerbation in patients with moderate COPD has been reported as 1.02 per person per year for females and 0.74 per person per year for males.17 The estimated annual rate of exacerbation in our study was 0.57 per patient per year, which was relatively lower than that in previous studies. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in the study population; our study included 9.3% patients with mild COPD and a majority of male patients.

A previous history of exacerbation is a well-known risk factor for future exacerbation,14 and our study confirmed this. A total of 58.3% patients with a previous history of exacerbation experienced acute exacerbations in the first year of follow-up. This figure was significantly higher than that for patients without a history of exacerbation (P=0.000). In logistic regression analysis, OR for a previous exacerbation history was 3.12 (95% CI, 1.35–7.23; P=0.008).

We also explored the association between baseline FEV1 and COPD exacerbations. The estimated exacerbation rates were 23.1% for patients with an FEV1 of ≥80% of the predicted value, 28.3% for patients with an FEV1 of 60%–80% of the predicted value, and 35.8% for patients with an FEV1 ≤60% of the predicted value. There was no significant association, although the COPD exacerbation rate was higher for patients with poor lung function (P=0.369).

SGRQ-c and CAT scores were significantly higher for patients with a previous history of exacerbation, and the differences between groups were above the minimal clinically important difference for each score.18,19 This finding supported the findings of previous studies reporting that exacerbations were significantly associated with an impairment in health status.2,20 Binominal logistic regression analysis revealed that patients with poor SGRQ-c scores were at greater risk of COPD exacerbation. Although some previous studies have demonstrated that a poor SGRQ-c score was a risk factor for readmission or increased COPD-related mortality,21–24 to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report a direct association between the SGRQ-c score and COPD exacerbation, particularly in patients with mild-to-moderate airflow limitation.

We also evaluated the association between self-reported comorbidities and COPD exacerbation and found that only hyperlipidemia was associated with COPD exacerbation; other diseases such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, osteoporosis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease were not significant factors. However, because of the short follow-up duration in this study, it was difficult to fully determine the relationship between the COPD exacerbation rate and comorbidities. Further research is needed to determine this association.

Pneumonia is a well-known risk factor for COPD exacerbation.1,25 Patients with a history of childhood pneumonia were found to develop more frequent and severe COPD exacerbations compared with patients with no history.26 We showed that a history of pneumonia was more frequent in patients with COPD exacerbation and was a risk factor for COPD exacerbation according to logistic regression analysis. This finding was consistent with that of a study conducted in South Korea, where it was reported that a history of pneumonia increased the risk of COPD exacerbation by 18 times.20

Distinct phenotypes are believed to exist in terms of acute COPD exacerbation,27 and there may be different phenotypes in patients with different degrees of airway limitation in terms of the development of acute exacerbation. In the present study, we showed that a history of pneumonia was associated with COPD exacerbation in addition to a history of previous exacerbation. This finding suggests that chronic airway bacterial colonization is a more important risk factor for COPD exacerbation in patients with mild-to-moderate airflow limitation.

This study has some limitations. First, the follow-up period was relatively short; therefore, we were unable to assess the long-term exacerbation events in patients with mild-to-moderate COPD. However, we believe that this study provides an insight that a substantial number of COPD patients with mild-to-moderate airflow limitation can experience exacerbation. Second, we attempted to determine the relationship between comorbidities and COPD exacerbation; however, the exacerbation rate was not fully evaluated with regard to comorbidities. Also, the use of self-reported comorbidities may have confounded the accuracy of results. Third, the predominance of male patients and patients with GOLD 2 is inconsistent with the patients samples in previous prevalence studies regarding COPD.7,8 Because our subjects were already diagnosed with COPD, our study may differ from those of previous prevalence studies aimed at the general population. Furthermore, our study sample may reflect the actual situation in Korea.28

Despite these limitations, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report the incidence of exacerbation in COPD patients with mild-to-moderate airflow limitation in actual clinical setting. In future course of this ongoing study, we will determine the entire natural course of disease in this patient population.

Conclusion

We found that 30.5% COPD patients with mild-to-moderate airflow limitation developed acute exacerbation in the first year of follow-up. The development of acute exacerbation was associated with quality of life, a previous history of exacerbation, and a history of pneumonia. Patients with mild-to-moderate airflow limitation may exhibit different phenotypes; this will be clarified during the future course of this ongoing study.

Summary at a glance

This study examines the factors associated with acute exacerbation in patients with mild-to-moderate COPD in South Korea. The results suggest that exacerbations occur more frequently in patients with a history of pneumonia or exacerbation in mild-to-moderate COPD patients.

Supplementary material

Proportion of patients according to the exacerbation of COPD during the first year of follow-up.

Abbreviation: GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. [Accessed February 5, 2014]. updated 2014. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.org.

- 2.Spencer S, Calverley PMA, Burge PS, Jones PW. Impact of preventing exacerbations on deterioration of health status in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(5):698–702. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00121404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soler-Cataluna JJ, Martınez-Garcıa MA, Roman Sanchez P, Salcedo E, Navarro M, Orchando R. Severe acute exacerbations and mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2005;60(11):925–931. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.040527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donaldson GC, Seemungal TAR, Bhowmik A, Wedzicha JA. Relationship between exacerbation frequency and lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2002;57(10):847–852. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.10.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan SD, Ramsey SD, Lee TA. The economic burden of COPD. Chest. 2000;117:5S–9S. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.2_suppl.5s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korean Academy of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Disease COPD Guidelines. [Accessed February 5, 2014]. revised 2012. Available from: http://www.lungkorea.org/thesis/guide.php.

- 7.Buist AS, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, et al. BOLD Collaborative Research Group. International variation in the prevalence of COPD (The BOLD Study): a population-based prevalence study. Lancet. 2007;370(9589):741–750. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61377-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menezes AMB, Perez-Padilla R, Jardim JRB, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in five Latin American cities (the PLATINO study): a prevalence study. Lancet. 2005;366:1875–1881. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67632-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang YI, Park YB, Oh YM, et al. Comparison of Korean COPD guideline and GOLD Initiative Report in term of acute exacerbation: a validation study for Korean COPD guidelines. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29(8):1108–1112. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2014.29.8.1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rhee CK, Kim JW, Hwang YI, et al. Discrepancies between modified Medical Research Council dyspnea score and COPD assessment test score in patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1623–1631. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S87147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bestall JC, Paul EA, Garrod R, Garnham R, Jones P, Wedzicha J. Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1999;54(7):581–586. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.7.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, Wiklund I, Chen WH, Kline Leidy N. Development and first validation of the COPD Assessment Test. Eur Respir J. 2009;34(3):648–654. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00102509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mequro M, Barley EA, Spencer S, Jones PW. Development and validation of an improved, COPD-specific version of the St. George Respiratory Questionnaire. Chest. 2007;132(2):456–463. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seemungal TAR, Donaldson GC, Bhowmik A, Jeffries DJ, Wedzicha JA. Time course and recovery of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(5):1608–1613. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9908022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calverley PMA, Anderson JA, Celli B, et al. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(8):775–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seemungal TAR, Hurst JR, Wedzicha JA. Exacerbation rate, health status and mortality in COPD – a review of potential interventions. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2009;4:203–223. doi: 10.2147/copd.s3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, et al. Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) Investigators. Susceptibility to exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(12):1128–1138. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kon SS, Canavan JL, Jones SE, et al. Minimum clinically important difference for the COPD Assessment Test: a prospective analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(3):195–203. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones PW. St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2(1):75–79. doi: 10.1081/copd-200050513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang YI, Lee SH, Yoo JH, et al. History of pneumonia is a strong risk factor for COPD exacerbation in South Korea: the EPOCH study (Epidemiologic review and Prospective Observation of COPD and Health in Korea) J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(12):2203–2213. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.12.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mapel DW, Robert MH. Spirometry, the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire and other clinical measures as predictors of medical costs and COPD exacerbation events in a prospective cohort. Southwest Respir Crit Care Chron. 2015;3(10):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osman LM, Godden DJ, Friend JAR, Legge JS, Douglas JG. Quality of life and hospital re-admission in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1997;52:67–71. doi: 10.1136/thx.52.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mullerova H, Maselli DJ, Locantore N, et al. Hospitalized exacerbation of COPD. Risk factors and outcomes in the ECLIPSE cohort. Chest. 2015;147(4):999–1007. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Domingo-Salvany A, Lamarca R, Ferrer M, et al. Health-related quality of life and mortality in male patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(5):680–685. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2112043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papi A, Bellettato CM, Braccioni F, et al. Infections and airway inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severe exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(10):1114–1121. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200506-859OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayden LP, Hobbs BD, Cohen RT, et al. Childhood pneumonia increases risk for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the COPD-Gene study. Respir Res. 2015;16(1):115. doi: 10.1186/s12931-015-0273-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lopez-Campos JL, Agusti A. Heterogeneity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations: a two-axes classification proposal. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(9):729–734. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoo KH, Kim YS, Sheen SS, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Korea: the fourth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2008. Respirology. 2011;16(4):659–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.01951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Proportion of patients according to the exacerbation of COPD during the first year of follow-up.

Abbreviation: GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.