Significance

In the United States, large, persistent gaps exist in the rates at which racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups complete postsecondary education, even when groups are equated on prior preparation. We test a method for preventing some of those gaps by providing individuals with a lay theory about the meaning of commonplace difficulties before college matriculation. Across three experiments, lay theory interventions delivered to over 90% of students increased full-time enrollment rates, improved grade point averages, and reduced the overrepresentation of socially disadvantaged students among the bottom 20% of class rank. The interventions helped disadvantaged students become more socially and academically integrated in college. Broader tests can now be conducted to understand in which settings lay theories can help remedy postsecondary inequality at scale.

Keywords: inequality, behavioral science, field experiment, social psychology, lay theories

Abstract

Previous experiments have shown that college students benefit when they understand that challenges in the transition to college are common and improvable and, thus, that early struggles need not portend a permanent lack of belonging or potential. Could such an approach—called a lay theory intervention—be effective before college matriculation? Could this strategy reduce a portion of racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic achievement gaps for entire institutions? Three double-blind experiments tested this possibility. Ninety percent of first-year college students from three institutions were randomly assigned to complete single-session, online lay theory or control materials before matriculation (n > 9,500). The lay theory interventions raised first-year full-time college enrollment among students from socially and economically disadvantaged backgrounds exiting a high-performing charter high school network or entering a public flagship university (experiments 1 and 2) and, at a selective private university, raised disadvantaged students’ cumulative first-year grade point average (experiment 3). These gains correspond to 31–40% reductions of the raw (unadjusted) institutional achievement gaps between students from disadvantaged and nondisadvantaged backgrounds at those institutions. Further, follow-up surveys suggest that the interventions improved disadvantaged students’ overall college experiences, promoting use of student support services and the development of friendship networks and mentor relationships. This research therefore provides a basis for further tests of the generalizability of preparatory lay theories interventions and of their potential to reduce social inequality and improve other major life transitions.

Many students face significant challenges during the transition to college, increasing their risk of dropping out (1–4) and undermining their future financial security, health, and contributions to society (5, 6). Students who contend with social and economic disadvantages can experience worse outcomes even when they enter with identical academic qualifications (2, 3, 7, 8). Of course, institutions provide supports and resources to help students navigate the transition to college, but this often occurs after they have entered the institution. Is it possible to improve the transition in advance? Could this mitigate inequality?

Students may not benefit from additional support before a transition, for instance, more college advising, because they have not yet faced the challenges associated with a new role or setting. They might also forget material taught months in advance, such as step-by-step directions for studying or for choosing classes.

However, taking a psychological approach, it may be helpful to provide a lay theory (9) of the transition—a starting hypothesis that many challenges in the transition are common and not cause to doubt one’s prospects of belonging and success (10, 11). This kind of lay theory may help people make sense of challenges they later face and take steps to overcome them, for instance, by helping students feel comfortable accessing support services and reaching out to peers and professors.

If preparatory lay theory interventions were effective, it would suggest a route for improving the college transition and, perhaps, other life transitions. Moreover, because many colleges have structural opportunities to reach students en masse before matriculation—such as first-year student registration or orientation—this strategy might remedy a portion of group disparities at institutional scale.

Not all psychological interventions are effective as preparation. Writing expressively about emotions elicited by a past trauma helps people cope and improves health, but expressive writing before a trauma (e.g., a life-altering surgery) does not (12). Likewise, people undergoing exposure therapy for anxiety disorders do not seem to benefit from time anticipating an upcoming aversive stimulus, even though processing emotions after exposure to the aversive stimulus does improve outcomes (13). This may be because people have difficulty forecasting the nature and emotional intensity of future experiences (14).

However, lay theory interventions do not require people to preprocess emotions. Instead, they provide a basis for assigning meaning to experiences. Just as a scientific theory allows a researcher to understand the causes and effects they observe in their data (15), lay theories help people interpret adversities they encounter—what caused the adversities and what they mean for their future (9). Even if people cannot remember step-by-step directions long in advance, it may be memorable and helpful to learn that struggling in class or having difficulty making friends does not mean that they, or people like them, are unintelligent or do not belong.

Lay theory interventions should benefit students most who have the greatest reason to draw negative inferences from adversities in college and, therefore, may help reduce group-based inequalities (7). In the United States, students from racial/ethnic minority groups and those who would be the first in their families to earn a college degree (i.e., first-generation students) can face negative stereotypes about their intellectual ability, numeric underrepresentation, and other group-based threats on campus (2, 3, 7, 16). This circumstance can lead students to worry whether they and people like them can fully belong (11, 17), will be seen as lacking intelligence (7, 18, 19), or will be a poor cultural fit in college (20, 21). Although students from majority groups can experience personal worries about belonging and potential, they are less likely to experience these at the group level. Such concerns seed harmful inferences for even commonplace challenges in college such as feelings of loneliness, academic struggles, or critical feedback: “Maybe this means people like me do not belong or cannot succeed.” These inferences sap motivation and undermine achievement through a cycle that gains strength through its repetition (22, 23).

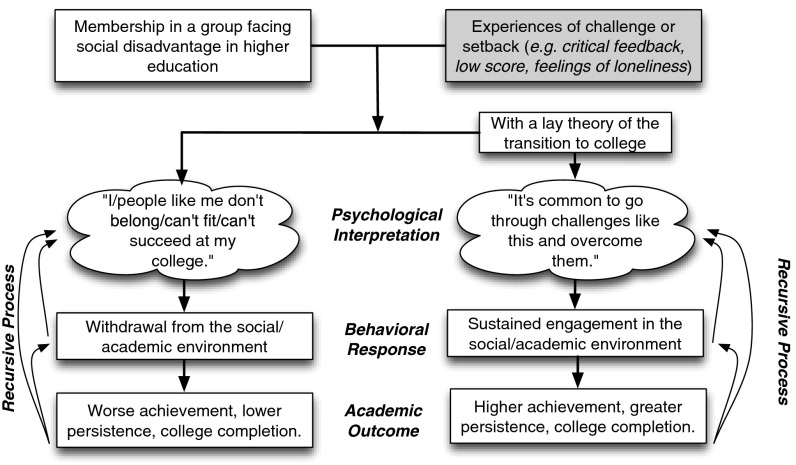

This process is depicted in Fig. 1, which highlights how problematic lay theories—arising from group-based experiences that give rise to persistent worries about belonging, potential, and cultural fit—can impede the social and academic integration critical to success in college (4, 24), contributing to group-based inequality.

Fig. 1.

Theoretical model: the process through which lay theories affect disadvantaged students’ behavior and academic outcomes across the transition to college.

As we have suggested, a corollary of the process in Fig. 1 is that providing people with an alternative lay theory—one that characterizes adversities as common and improvable—should reduce those inequalities. In small-scale trials, this strategy has been effective when carried out as treatment. Specifically, interventions teaching an alternative lay theory have raised achievement for negatively stereotyped racial minority and first-generation college students (11, 18, 20), in one case reducing the racial achievement gap by half over 3 years. Furthermore, effects appeared to be mediated by the psychological and behavioral processes depicted in Fig. 1—for instance, asking professors or teaching assistants for help, attending office hours, or taking chances on making friends (11, 17, 25).

Although promising, the scale and timing of past lay theory interventions in college have been limited by the constraints of face-to-face delivery. Each past trial was implemented at a selective 4-y university and involved fewer than 50 treated disadvantaged students. The present studies, by contrast, randomized more than 90% of students at three diverse institutions to online lay theory or control conditions (n > 9,500).

Thus, in addition to our primary contribution of testing the potential of preparatory rather than reactive lay theory interventions, these studies provide an unparalleled test of the scalability, replicability, and generalizability of lay theory interventions to lessen postsecondary inequality. Further, we administer a much broader range of measures of social and academic integration than available in past lay theory research, directly testing the processes predicted in Fig. 1.

Overview of Present Research

Three double-blind, randomized experiments tested the effects of prematriculation (i.e., before arriving on campus), Internet-administered lay theory interventions on postsecondary outcomes for students who face greater social and economic disadvantages in college. Randomization was at the student level.

The primary objective was to test the general efficacy of preparatory lay theory interventions, so the studies tested several variants, including (i) two used in past research with college students (addressing social belonging and growth mindset of intelligence) (11, 18, 26), (ii) one used previously with younger students (addressing lay theories about critical feedback) (27), and (iii) a novel intervention based on prior research and theory with college students (addressing lay theories about cultural fit) (21). All interventions had a common structure, format, and length (Methods and SI Appendix, Appendix 1).

Each experiment had four conditions—one control and three interventions. The primary analysis involved the contrast of receiving any intervention versus the control. Post hoc comparisons tested for differences among them. In the one case where a difference was found, interventions were interpreted separately.

Evaluations were conducted in diverse settings—high school seniors exiting high-performing charter school networks and attending 70+ mostly low-selectivity 2- and 4-y colleges, first-year students at a public flagship with low 4-y graduation rates, and first-year students at a highly selective university. Analyses focused on core first-year college outcomes appropriate to these contexts. In each setting, students were known to be college-ready. This was crucial for testing our theory; lay theories will not remedy inadequate preparation but may allow prepared students to achieve in college.

As in past experiments, negatively stereotyped racial/ethnic minority students and first-generation students were expected to benefit. Although these groups differ in important respects, they share a common psychological predicament in college: group-based fears about belonging, potential, or cultural fit (7, 17, 21). However, social and economic disadvantages are not inherent to groups but defined by the social context (28). Therefore, in experiments 2 and 3, the groups expected to benefit were defined using (i) theory and (ii) institutional data revealing which groups have, in the past, performed less well at each university (see analyses in SI Appendix, Appendix 3, pp. 30–31, and Appendix 4, pp. 49–50). In experiment 1, all students were either racial minority or first-generation students and, based on low graduation rates in previous cohorts, were known to face disadvantages in college.

Throughout the paper, all estimates are raw percentages or means, unadjusted for covariates. All analyses are intent-to-treat. Statistical tests for treatment effects are from regression models with preintervention covariates (SAT score, high-school class rank, and gender). Significance levels do not differ without covariates.

Results

Experiment 1: Urban Charter Graduates.

Participants were two cohorts of outgoing seniors at four high-performing urban charter schools (n = 584). They were admitted to more than seventy 4- and 2-y public and private colleges. This study involved initial correlational analysis of the effects of the social belonging lay theory, followed by an experiment testing the effects of a social belonging lay theory intervention, customized for urban charter students (SI Appendix, Appendix 2a). Fully crossed with this was a growth mindset of intelligence intervention, a week later.

Correlational analysis.

First, correlational data among untreated students from the first cohort of data collection (n = 185) showed that those who had a lay theory that they might not belong in college (i.e., belonging uncertainty, e.g., “Sometimes I worry that I will not belong in college”) (17) were less likely to persist through the first year of college [logistic regression odds ratio (OR) = 0.66, Z = −2.60, P = 0.009]. This was true controlling for a number of covariates (SI Appendix, Appendix 2b, Table S7). No other personality trait or lay theory, including growth mindset (see below), predicted college persistence in this sample, nor did intelligence quotient, net of SAT, and grade point average (GPA). Beyond prior preparation, it was not students’ traits or attitudes that predicted success in the transition to college. It was the presence of an initial doubt about whether they would fit in (for related analyses, see ref. 3).

Primary intervention outcome: Full-time enrollment.

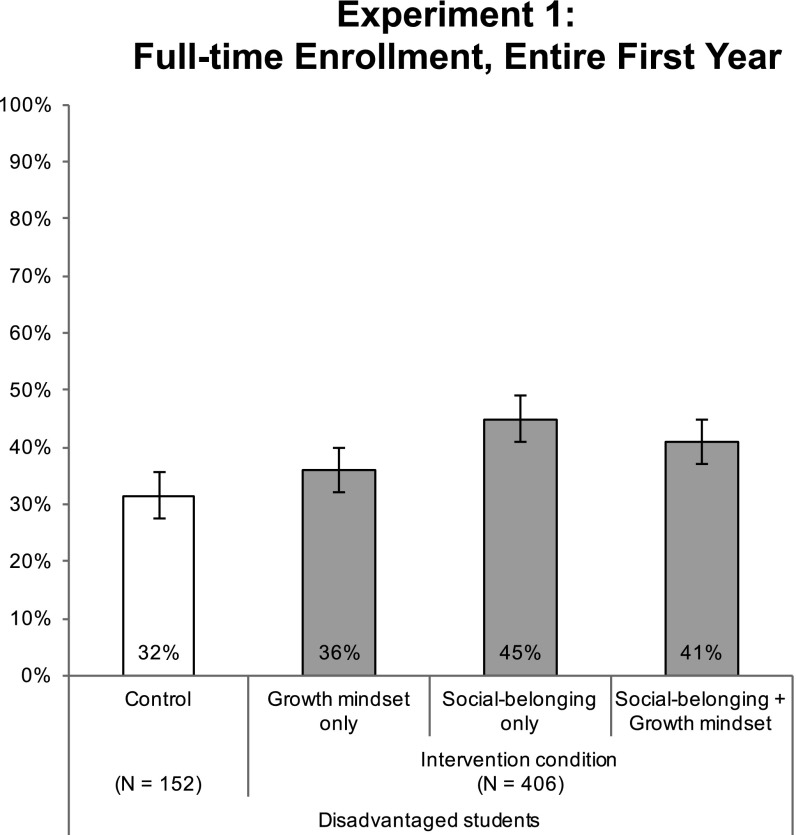

Among students from both cohorts, only 32% of students in the randomly assigned active control condition were enrolled full-time continuously for the first year of college, even though 100% were admitted to college. For students who received any preparatory lay theory intervention, that number was 41%, a significant increase (logistic regression OR = 1.59, Z = 2.17, P = 0.030).

Post hoc tests revealed that this treatment contrast masked significant heterogeneity (growth mindset only = 36%; social belonging only = 45%; social belonging plus growth mindset = 41%) (Fig. 2). The growth mindset-only condition showed significantly poorer outcomes compared with the two social belonging conditions (Z = 2.00, P = 0.046) and did not differ from active controls (P > 0.50) (see below for possible explanation). Furthermore, the two social belonging conditions did not differ on the basis of whether students also received a growth mindset (Z = 1.13, P = 0.26), and both social belonging conditions combined differed significantly from the active control, logistic regression (OR = 1.87, Z = 2.70, P = 0.007). Hence, only the social belonging intervention was effective in the present experiment.

Fig. 2.

A prematriculation social belonging intervention improves full-time college enrollment among urban charter high school graduates in experiment 1. The growth mindset intervention was not effective in this experiment. Bars represent raw, unadjusted means or percentages.

Social belonging intervention.

Why was the social belonging intervention effective? First, survey questions answered moments after completing the social belonging materials showed that it effectively taught the lay theory that many students feel that they do not belong at first in college but come to do so over time (SI Appendix, Appendix 2a, Table S5; for analogous self-reports in experiments 2 and 3, see SI Appendix, Appendix 3, Table S9, and Appendix 4, Table S17).

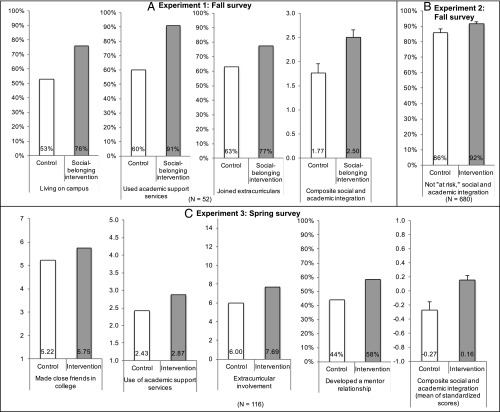

Next, an exploratory analysis of survey data at 6-mo follow-up suggests that the social belonging intervention increased students’ social and academic integration on campus, supporting the model in Fig. 1. Students who received a social belonging intervention were more likely than students who did not to report that they had used academic support services, had joined an extracurricular group, and had chosen to live on campus [composite index of social and academic integration, t(50) = 2.76, P = 0.008, d = 0.78] (Fig. 3). This index statistically mediated effects of the social belonging intervention on year-end full-time continuous enrollment [indirect effect b = 0.15 (95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.03, 0.29), P < 0.01] (28). There was no effect of the mindset intervention on this metric (P > 0.50). This mediation analysis is limited by sample size, effects in only two of three intervention conditions, and narrow scope of measures. These are improved upon in experiment 2.

Fig. 3.

Prematriculation lay theory interventions improve disadvantaged students’ social and academic integration in college in the first year. (A) Experiment 1: social belonging, participants from two conditions that received a social belonging intervention; control, participants from two conditions that did not receive a social belonging condition (because the growth mindset intervention did not affect full-time enrollment or survey responses, as noted in the text). (B and C) Experiments 2 and 3: any intervention, participants receiving any of the three interventions; control, participants receiving no intervention. Bars represent raw means or percentages, unadjusted for covariates. The y axes for unstandardized scores represent full scale ranges.

Growth mindset intervention.

The growth mindset of intelligence intervention has previously been effective when delivered via the Internet (26, 29) but, as noted, was not here. This was not expected. Two possibilities are germane, but we cannot definitively confirm one or the other. One is that the intervention was redundant with growth mindset messages already taught by the high-performing charter network: the school already administered similar materials and messages, and students in this population already endorsed a growth mindset (SI Appendix, Appendix 2b, p. 28). A second is that the growth mindset message was represented as a private belief, not a reflection of their college’s values. Even apart from private beliefs, the perception that an organization endorses a fixed mindset can lead people who face negative stereotypes to worry that their intelligence will be questioned (30).

Experiment 2: Public University.

Experiment 2 extended experiment 1 by (i) testing lay theory interventions with incoming students at a high-quality 4-y public university, instead of outgoing students at a high school network; (ii) having interventions come from the university instead of the high school, which may increase efficacy (31); (iii) testing whether students from socially and economically disadvantaged backgrounds benefit disproportionately and, thus, whether lay theory interventions remedy a portion of inequality; (iv) increasing the sample size by a factor of 12 (n = 7,335); (v) investigating the model in Fig. 1 with a broad measure of social and academic integration; and (vi) comparing students in the randomized cohort to students in previous and later cohorts not randomized to condition, to examine reductions in inequality for the entire institution. For details on intervention materials and the sample, see SI Appendix, Appendix 3. The focal lay theory interventions were social belonging and growth mindset of intelligence interventions. The latter was theoretically distinct from that tested in experiment 1 in that it represented growth mindset as the ethos of the university.

Primary outcome: Full-time enrollment.

A leading predictor of on-time graduation is first-year full-time enrollment (i.e., completing 12+ credits both semesters of the first year) (32). Therefore, as in experiment 1, this was the primary outcome.

First, inequality at this institution in the randomized control group was large. Disadvantaged students in the control condition were 10 percentage points less likely to complete the first year full-time enrolled in both terms compared with advantaged students (69% versus 79%; raw values; χ2(1) = 27.32, P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Percent completing fall semester full-time enrolled in experiment 2, by year or condition

| Study year or condition | Advantaged students | Disadvantaged students |

| 2011: no intervention (n = 6,896) | 90% | 81% |

| 2012: randomized control (n = 2,062) | 90% | 82% |

| 2012: randomized intervention (n = 5,356) | 90% | 86%*** |

| 2013: no intervention (n = 6,719) | 88% | 81% |

| 2014: nonrandomized intervention (n = 6,244) | 90% | 84%*** |

P < 0.001, significantly different from disadvantaged students who did not receive the intervention.

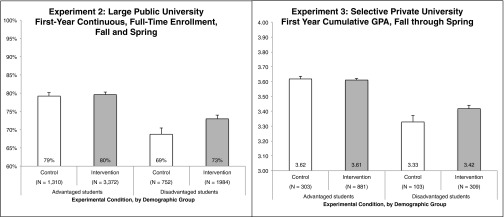

Next, the one-time prematriculation lay theory interventions cut this inequality by 40%, increasing the percentage of full-time enrolled disadvantaged students over the first year to 73%, a significant increase compared with the randomized control group (OR = 1.23, Z = 2.26, P = 0.024). Unlike experiment 1, there was no heterogeneity across intervention conditions, meaning that they appeared to be equally effective (mindset only = 74%; belonging only = 72%; social belonging plus growth mindset = 73%; all pairwise contrasts among intervention conditions Ps > 0.50).

There was no effect of the lay theory interventions among advantaged students (OR = 1.03, Z = 0.22, P = 0.79), nor was there expected to be, replicating past research (11). However, because the trend for advantaged students was positive, the group × condition interaction did not reach significance (Z = 1.59, P = 0.11), as in some past research (18) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Prematriculation lay theory interventions narrow first-year achievement gaps when delivered to entire incoming classes (>90%). Each experiment involved three intervention conditions that are presented in composite form because they did not differ significantly. Experiment 2 intervention condition separate effects: mindset only, 74%; belonging only, 72%; social belonging plus growth mindset, 73%. Experiment 3 intervention condition separate effects: social belonging, 3.39; cultural fit, 3.47; critical feedback, 3.39. Bars represent raw, unadjusted means or percentages.

Why was the growth mindset lay theory intervention beneficial here (SI Appendix, Appendix 3, Table S10) but not in experiment 1? One possibility is that this sample had not been systematically exposed to prior growth mindset messaging (although we do not have a direct test of this). A second and related possibility is that a growth mindset was more consequential for this sample: here, unlike experiment 1, growth mindset predicted full-time enrollment in the control group (SI Appendix, Appendix 3, p. 36) (belonging uncertainty was also a significant predictor, P < 0.01, replicating experiment 1). Third, here the growth mindset message signaled the beliefs of key people in the institution (e.g., professors), as shown by analyses of the manipulation check items (30). Furthermore, students’ beliefs about the university’s growth mindset ethos predicted outcomes in the control group net of SAT scores (SI Appendix, Appendix 3, p. 36).

The condition that combined growth mindset and belonging treatments was no more (or less) effective than either intervention on its own, replicating findings from analogous research (26). One explanation for this comes from manipulation check analyses, which suggest that by teaching two messages in a single session, neither came through as clearly as when they were taught alone (SI Appendix, Appendix 3, p. 40).

Full-scale institutional change.

Year-over-year comparisons (n = 14,216 advantaged and disadvantaged students) examined whether the lay theory interventions could contribute to reductions in institutional-level inequality when delivered to the entire incoming student body without randomization (analyses focused on full-time fall term enrollment because spring term data were unavailable for the nonexperimental years; Table 1). There were no over-time changes among disadvantaged students who did not receive an intervention (81–82%), but disadvantaged students who received the randomized treatment (86%) and who received the nonrandomized treatment (84%) both differed from all untreated disadvantaged students (Ps < 0.001), and this produced significant disadvantaged group × condition interactions (Ps < 0.001) because there was no corresponding increase for advantaged students (intervention year, 90%; nonintervention years, 88–90%). Hence, the lay theory interventions appear to have led to full-scale reduction in institutional inequality.

Social and academic integration.

Among the quarter of students randomized to the control group, disadvantaged students were more likely to be identified as at risk for dropping out due to their reports of social and academic integration (disadvantaged students: 13% at risk of dropping out; advantaged students: 8%), a marginally significant inequality (Z = 1.92, P = 0.055). However, among the three-quarters of students randomized to a lay theory intervention, only 7% of disadvantaged students were designated at risk, a significant decrease (Z = 2.46, P = 0.014), eliminating the group difference (Fig. 3). This improvement in social and academic integration mediated the intervention effect on continuous full-time full-year enrollment among disadvantaged students [indirect b = 0.01 (95% CI = 0.001, 0.03), P = 0.040] (28).

Experiment 3: Selective University.

Experiment 3 extended these results by (i) testing preparatory lay theory interventions at a selective private university (n = 1,592); (ii) examining an outcome appropriate for selective colleges (cumulative first-year GPA instead of full-time enrollment because fewer than 1% of participating students at this institution fail to persist through their first year); (iii) testing social belonging and two other lay theory interventions, focused on cultural fit and the experience of receiving critical feedback, but not growth mindset; and (iv) providing a more detailed assessment of social and academic integration than available in experiment 2 and assessing this at the end of the academic year instead of during the fall term. This precludes mediational analyses but assesses the durability of benefits.

Primary outcome: First-year GPA.

In the randomized control condition, disadvantaged students earned lower GPAs than advantaged students (disadvantaged students: M = 3.33 on a 4.0 scale; advantaged students: M = 3.62; raw means), planned contrast t(1,591) = 6.99, P < 0.001, d = 0.80—a significant achievement gap.

However, receiving a lay theory intervention raised disadvantaged students’ first-year GPAs by 0.09 grade points to 3.42, a significant improvement [t(1,591) = 2.16, P = 0.031, d = 0.25]. Like experiment 2, post hoc tests found no heterogeneity across treatment conditions (all contrast ps > 0.30; social- belonging = 3.39; cultural fit = 3.47; critical feedback = 3.39). The improvement from the combined preparatory lay theory interventions corresponds to a 31% reduction in the raw achievement gap (47%, covariate-adjusted; SI Appendix, Appendix 4, Table S17). There was no intervention effect for advantaged students, t < 1, and the subgroup × condition interaction was significant [F(1,1588) = 4.04, P = 0.045] (Fig. 4).

Previous national surveys found that disadvantaged students at elite colleges disproportionally end up in the lowest quintile of class rank (the bottom 20%) (2). Replicating this, in the control condition, 46% of disadvantaged students fell in the bottom quintile for first-year GPA. This percentage was reduced to 29% by the lay theory interventions [χ2(1) = 8.76, P = 0.003] (for results for all class rank increments, see SI Appendix, Appendix 4, Figs. S4 and S5). There was no harm or benefit on class rank for advantaged students (χ2 < 1).

Comparison with preintervention years.

Historical data were obtained for two preintervention years (n = 3,029). The cumulative first-year GPAs of disadvantaged students randomized to the control condition in the study year did not differ from those in the prior years (3.33 vs. 3.32, respectively; P > 0.80). However, disadvantaged students who received a lay theory intervention earned significantly higher GPAs relative to peers from nonintervention years [planned contrast t(4517) = 4.02, P < 0.001, d = 0.26].

Social and academic integration.

Analyses of a spring survey, completed roughly 11 mo postintervention, showed that treated disadvantaged students reported greater social and academic integration on campus at the end of the first year—having made more close friends, being more likely to have developed a close mentor relationship, being more involved in extracurricular groups, and making greater use of academic support services—compared with randomized controls [composite index planned contrast t(473) = 3.20, P = 0.001, d = 0.72] (SI Appendix, Appendix 4, Table 21) (Fig. 3).

Although consistent with our process model (Fig. 1), these responses were collected after most grades had been recorded and so cannot be used in mediation analysis of first-year GPA. However, friends, mentors, and extracurricular involvement are important outcomes in their own right and facilitate later college achievement, as well as postcollege opportunities above and beyond classroom performance (4, 24).

Discussion

The present research has two major contributions. First, it shows that preparatory lay theory interventions can be effective in the college transition. Second, it directly informs theory about societal inequality (6).

Preparatory Intervention.

Three institutional-scale, double-blind, randomized, active-controlled experiments showed improvement in disadvantaged students’ achievement in the first year of college. In experiments 2 and 3, the treatments reduced raw achievement gaps by 31–40%. These effects were obtained with samples of 90%+ of incoming students and reproduced when the intervention was administered to all students on a nonrandomized basis (experiment 2). Extending past research, they represent the most rigorous replication of lay theory interventions to date. These characteristics make the quality of these data unusually high and highly relevant for policy as well as for cumulative science.

On a practical level, these effect sizes are important. When a single college student does not graduate, he or she can forfeit between $500,000 to $1 million dollars in lifetime wages (33). Likewise, colleges and universities invest significant resources to recruit and retain students from underrepresented groups, and society bears financial responsibility for adults who cannot find work due to a lack of training. The present effects thus signify the recovery of meaningful financial losses for individuals, colleges, and the public. Moreover, once evaluated in a given context, the present interventions can be administered at low marginal cost on an ongoing basis. Indeed, this has occurred in the postintervention years with the schools that participated in these experiments. This said, the present results derive from a specific set of postsecondary settings. A critical next step, for both theory and application, is to systematically interrogate settings to determine where effects are greater or weaker.

Can preparatory lay theory interventions improve other major life transitions? This is an exciting possibility. If a new mother struggles to cope with a difficult baby, will she benefit from knowing in advance that this does not make her a bad mother but is common and can improve with time? If a veteran struggles to find work, will he or she benefit from hearing in advance stories about struggles other veterans faced returning to civilian society and how they overcame these? What kinds of people are most at risk for drawing harmful inferences in these and other major life transitions (e.g., to retirement and in divorce), who may benefit most from lay theory interventions? Is it possible to deliver such interventions at a socially meaningful scale? Research to answer these questions could uncover new ways to reduce long-standing social problems.

Societal Inequality.

Educational attainment is the best predictor of upward mobility in the developed world (6); thus, inequality in the rates at which qualified students from different racial, ethnic, and social class backgrounds complete college threatens the ideal of meritocracy and undermines both individuals’ life prospects and national economic growth (2, 3, 8). Our findings directly speak to ongoing debates about the bases of inequality in sociology, economics, and law.

For instance, sociologists have found that prior social and economic disadvantages faced by African-American, Latino, and lower-social class college students predict their belief that people in college will view them as not having the intellectual potential to succeed. These beliefs, in turn, predict poor college achievement and persistence (2, 3). Relatedly, using correlational data, economists have estimated that nearly half of dropouts after the first year of college among socioeconomically disadvantaged students can be attributed to a loss of confidence in the first term (1). However, the lack of causal evidence for these relationships led one leading scholar to lament, “How strong is the evidence that beliefs matter? Unfortunately, not very strong” (ref. 8, p. 69). Using random assignment experiments, the present research directly confirms the role of student beliefs (aka lay theories) arising from social disadvantage in causing postsecondary inequality, at least within the settings studied here.

Next, one influential economic model suggests that struggling first-year students learn that they truly lack intellectual ability, which allows them to make the informed choice to withdraw (1). Our experiments show that this choice need not reflect a lack of ability. When students learned that early difficulties are common and not necessarily diagnostic of a lack of ability or belonging, they showed they could succeed.

Our research also complements so-called behavioral economic approaches, which show that remedying procedural barriers (like simplifying the completion of financial aid forms and text messages to remind students to pay registration fees or select courses) can increase college persistence (34, 35). These are not thought to operate through the mechanisms depicted in Fig. 1 and therefore represent a complementary (not competing) cause of and remedy for postsecondary inequality.

Finally, in law, some scholars and Supreme Court justices have argued that it does racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic minority students a disservice to admit them to elite institutions where they will subsequently earn low class rank or drop out (36, 37). However, experiment 3 showed that low class rank is not automatic for students from disadvantaged backgrounds. When selective colleges create environments in which students’ belonging and potential are not constantly in question, they can admit a diverse class, and members of this class can succeed (38).

Implications, Limitations, and Future Directions.

A critical misinterpretation of our research would be to conclude that psychological disadvantage is simply in the head. To the contrary, worries about belonging and potential are pernicious precisely because they arise from awareness of real social disadvantage before and during college, including biased treatment, university policies and practices that inadvertently advantage some groups of students over others, and awareness of negative stereotypes and numeric underrepresentation (2–4, 7). Some lay theory interventions highlight how students’ experiences can differ along group identity lines and how students can overcome group-specific challenges to belong and succeed (20, 25). Further, in implementing lay theory interventions, institutions recognize how awareness of social disadvantage can facilitate threatening interpretations of adversities disproportionately for students from disadvantaged backgrounds. These interventions represent institutional efforts to help all students navigate challenges in college effectively.

Another misinterpretation would be to think of lay theories interventions as “magic bullets” that will work universally for all racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic minority students in all settings without adaptation or that they work alone, absent other student supports (23). Lay theory interventions should be effective only when (i) materials successfully redirect problematic lay theories in a given context (hence the customization carried out in each study) (29); (ii) student motivation is hindered by the targeted lay theory in a given context; and (iii) colleges afford instructional opportunities, relationship opportunities, and financial supports necessary for better outcomes (23).

A critical question then is, in what types of institutions will different groups of students benefit most and least from which lay theory interventions? The present research did not fully answer this, but it did find variability that may be informative for future theory development and replication attempts. A growth mindset intervention was ineffective in experiment 1, where students had already been taught a growth mindset and where the mindset intervention was not represented as reflective of their colleges’ values. However, it was effective in experiment 2, where students had not been systematically exposed to growth mindset ideas and where a growth mindset was represented as the ethos of the university. First-generation Asian-American students benefitted in experiment 2 but performed well and were not classified as disadvantaged in experiment 3.

We did not test whether students who were unprepared for college or who did not desire a college credential would benefit from the intervention because they were not expected to. It will be exciting in future research to expand to more heterogeneous samples of students and institutions, and, ideally probability-based samples, to allow for generalizable inferences.

Finally, it is essential to recognize that there are many psychologically meaningful events in the transition to college, which can either support or thwart students’ growth and belonging. Preparatory interventions have a special importance because they provide students a first lens for making sense of events they later experience. However, how a professor introduces difficult course material, provides critical feedback, or responds to a struggling student; how a dean welcomes the entering class; and how a university frames an academic probation letter, among many other events, can have independent effects (27, 28). These all represent opportunities to improve the psychological environment of college and thus student success.

Methods

General Intervention Procedures for All Experiments.

Each intervention used the same basic grammar to teach a lay theory (SI Appendix, Appendix 1). Each (i) clearly described specific difficulties in college and persuasively represented these as common and as changeable; (ii) provided vivid stories from upper-year students who experienced and overcame common struggles; (iii) conveyed data—either results of surveys or summaries of the neuroscience of learning—in support of these messages; and (iv) allowed participating students to take ownership of the lay theory after having reflected on the stories and data by writing about challenges they anticipated and how these challenges are common and likely to change over time. These essays, students were told, might be shared with future students to improve their transition (exemplary ones were). This final element, called the “saying-is-believing” technique, allows students to personalize generic materials, promoting internalization (10, 17, 18). The institutional review boards at the University of Texas at Austin and at Stanford University approved all procedures. Students provided active consent on the first page of the surveys. The data reported in this paper are tabulated in the SI Appendix and are available upon request from the authors to investigators, provided that requestors secure the necessary institutional review board approvals.

Experiment 1.

Participants and procedure.

Experiment 1 included two consecutive cohorts of seniors (n = 584, or 97% of students) graduating from high-performing “no-excuses” public urban charter high schools. This charter network has consistently produced large gains in state test scores compared with local district schools, it graduates almost all of its students, and college admission is a requirement for graduation. Hence, students were, by some standards, college-ready. However, only approximately one-fourth earn any postsecondary credential within 6 y.

Participants were predominately African-American (88%) and first-generation college students (67%) (all but one student were one, the other, or both). Continuous (fall and spring) full-time enrollment was tracked through an objective, third-party database: the National Student Clearinghouse (NSC). The NSC does not report GPA (39).

Intervention.

From students’ perspectives, the intervention was a survey about the transition to college in which they would hear from upper-year students. To control for placebo effects, all students were told the survey might be interesting and might help them succeed in college. Students completed it in their classrooms in May of their senior year of high school. After this session, students were not contacted again by researchers. Students in cohort 1 were later recruited by school staff (blind to condition) for the fall survey.

One-half of students were randomized to a social belonging lay theory intervention within gender × high school GPA (high vs. low) strata. The exact stories were based on prior research but revised extensively through a design thinking process (29) described in SI Appendix, Appendix 2a. The other half of participants were randomized to a control condition, which included similar tasks but focused on adjusting to the physical rather than social environment of college (e.g., weather and campus buildings). It also involved reading stories from upper-year students and writing an essay to future students transitioning to college. As noted, fully crossed with the social belonging intervention was a growth mindset of intelligence intervention. This was delivered 1 wk later (SI Appendix, Appendix 2a).

Fall survey.

For the first cohort of students (n = 172), staff at the partner charter network contacted students in late fall of their first year of college to invite them to complete a survey assessing social and academic integration on campus. The survey link was sent to students via email, text message, and social media. Thirty percent of students in this cohort completed the survey (n = 52 students). See SI Appendix, Appendix 2a, for questions.

Experiment 2.

Participants and procedure.

Participants were 7,335 (91%) of the first-year students entering a high-quality public university. Over 85% were in the top 10% of their high school class, but only 50% typically graduated in 4 ys (32).

Students completed online orientation materials in private between May and August in the summer before entering college. The materials were embedded among other preorientation tasks, including reporting immunization records, signing the honor code, registering for classes, etc. The presentation of the intervention mirrored experiment 1.

Interventions.

Randomization to one of four conditions occurred with equal probability within gender × SAT (high vs. low) × college major × race/ethnicity strata. The social-belonging intervention (11) was based on prior research and adapted to fit the prematriculation context. The growth-mindset intervention (18, 26) used neuroscientific information to convey that intelligence is not a fixed quantity but can be developed with effort on challenging tasks. In the combined condition, participants read growth mindset intervention content and upper-year student stories drawn from the belonging condition. The control condition mirrored experiment 1 and past research (11).

Survey.

Independent of the research team, the university hired a private firm to administer a web-based survey to all first-year students 2 mo into the fall semester. The survey was never associated with the present intervention and differed significantly in format and presentation. All first-year students were told in an email that they were required to complete it; 1,722 students (23%) did so. Student-level data on an aggregated “at-riskness” index were obtained by the research team (SI Appendix, Appendix 3).

Experiment 3.

Participants and procedure.

Participants were 1,592 matriculating students (90% of the incoming class) at a highly selective private university. Analogous to experiment 2, the intervention materials were embedded as a link on the matriculation website hosted by the university’s undergraduate advising office. Between mid-May and early June, students were required to complete a number of forms on this website. Randomization to one of four conditions occurred with equal probability within gender × race/ethnicity strata.

Interventions.

Students were randomized to a control condition, to a social-belonging intervention nearly identical to that tested in experiment 2, or to one of two other lay theory interventions, which addressed contextually specific beliefs relevant to social and academic belonging. One was a cultural fit intervention. This emphasized that although college has an independent cultural focus (e.g., “choose your path”), students can maintain interdependent social relationships with home communities and join interdependent communities in college. This message was designed to forestall the inference for students coming from interdependent cultural communities (many ethnic minority and first-generation college students) that early social difficulties mean that they have a fundamental cultural mismatch with college (21). The second was a critical feedback intervention. This emphasized that critical academic feedback from professors and other instructors reflects instructors’ high standards and confidence students can meet those standards, not a negative judgment of the student or his or her potential (27).

Survey.

In the spring of students’ first year, a follow-up survey was conducted with participating students. Students were invited to participate in exchange for a small token (a class sticker). A total of 31% of the sample (n = 491 out of 1,592) elected to do so. The survey also included additional items assessing attitudinal/affective measures such as feelings of belonging and perceived stress; for consistency with experiments 1 and 2, and to understand behavioral outcomes, analyses reported here focus on behavioral measures of social and academic integration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Aspire, KIPP, Mastery, and Yes Prep charter schools and the Stanford University d.school for assistance piloting and prototyping interventions. We thank PERTS for logistical and IT support. We also thank students and colleagues who contributed to design processes, including K. Belden, R. Crandall, C. Gabrieli, J. Gabrieli, A. Ericcsson, A. House, J. Powers, A. Royalty, C. Steele, and U. Treisman, and those who assisted with data collection and analysis, including J. Beaubien, K. Breiterman-Loader, C. Macrander, S. Keller, M. Niemasz-Cavanagh, P. McGowan, and O. Zahrt-Omar. Critical feedback was provided by B. Bigler, R. Crosnoe, C. Muller, J. Pennebaker, and the social and personality area at the University of Texas at Austin. This research received support from the William and Melinda Gates Foundation, Stanford University, and the University of Texas at Austin.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1524360113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Stinebrickner R, Stinebrickner T. Academic performance and college dropout: Using longitudinal expectations data to estimate a learning model. J Labor Econ. 2014;32(3):601–644. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Espenshade TJ, Radford AW. No Longer Separate, Not Yet Equal: Race and Class in Elite College Admission and Campus Life. Princeton Univ Press; Princeton: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Massey DS, Charles CZ, Lundy G, Fischer MJ. The Source of the River: The Social Origins of Freshmen at America’s Selective Colleges and Universities. Princeton Univ Press; Princeton: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tinto V. Leaving College: Rethinking the Causes and Cures of Student Attrition. Univ of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayward MD, Miles TP, Crimmins EM, Yang Y. The significance of socioeconomic status in explaining the racial gap in chronic health conditions. Am Sociol Rev. 2000;65(6):910–930. [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Addio AC. Intergenerational Transmission of Disadvantage: Mobility or Immobility Across Generations? A Review of the Evidence for OECD Countries. Organ for Econ Co-op and Dev; Paris: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steele CM. A threat in the air. How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. Am Psychol. 1997;52(6):613–629. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.52.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morgan SL. On the Edge of Commitment: Educational Attainment and Race in the United States. Stanford Univ Press; Stanford, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross L, Nisbett RE. The Person and the Situation: Perspectives of Social Psychology. 2nd Ed Pinter & Martin Ltd; London: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson TD, Linville PW. Improving the performance of college freshmen with attributional techniques. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1985;49(1):287–293. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walton GM, Cohen GL. A brief social-belonging intervention improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science. 2011;331(6023):1447–1451. doi: 10.1126/science.1198364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pennebaker JW, Chung CK. Expressive writing and its links to mental and physical health. In: Friedman HS, editor. The Oxford Handbook of Health Psychology. Oxford Univ Press; London: 2011. pp. 417–437. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tiwari S, Kendall PC, Hoff AL, Harrison JP, Fizur P. Characteristics of exposure sessions as predictors of treatment response in anxious youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2013;42(1):34–43. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.738454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson TD, Gilbert DT. Affective forecasting: Knowing what to want. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2005;14(3):131–134. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuhn TS. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Univ of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy MC, Steele CM, Gross JJ. Signaling threat: How situational cues affect women in math, science, and engineering settings. Psychol Sci. 2007;18(10):879–885. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walton GM, Cohen GL. A question of belonging: Race, social fit, and achievement. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92(1):82–96. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aronson JM, Fried CB, Good C. Reducing the effects of stereotype threat on African American college students by shaping theories of intelligence. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2002;38(2):113–125. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dweck CS, Leggett EL. A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychol Rev. 1988;95(2):256–273. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stephens NM, Hamedani MG, Destin M. Closing the social-class achievement gap: A difference-education intervention improves first-generation students’ academic performance and all students’ college transition. Psychol Sci. 2014;25(4):943–953. doi: 10.1177/0956797613518349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stephens NM, Fryberg SA, Markus HR, Johnson CS, Covarrubias R. Unseen disadvantage: How American universities’ focus on independence undermines the academic performance of first-generation college students. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2012;102(6):1178–1197. doi: 10.1037/a0027143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen GL, Garcia J, Purdie-Vaughns V, Apfel N, Brzustoski P. Recursive processes in self-affirmation: Intervening to close the minority achievement gap. Science. 2009;324(5925):400–403. doi: 10.1126/science.1170769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeager DS, Walton GM. Social-psychological interventions in education: They’re not magic. Rev Educ Res. 2011;81(2):267–301. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coleman JS. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am J Sociol. 1988;94:95–120. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walton GM, Logel C, Peach JM, Spencer SJ, Zanna MP. Two brief interventions to mitigate a “chilly climate” transform women’s experience, relationships, and achievement in engineering. J Educ Psychol. 2015;107(2):468–485. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paunesku D, et al. Mind-set interventions are a scalable treatment for academic underachievement. Psychol Sci. 2015;26(6):784–793. doi: 10.1177/0956797615571017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeager DS, et al. Breaking the cycle of mistrust: Wise interventions to provide critical feedback across the racial divide. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2014;143(2):804–824. doi: 10.1037/a0033906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy MC, Walton GM. From prejudiced people to prejudiced places: A social-contextual approach to prejudice. In: Stangor C, Crandall C, editors. Frontiers in Social Psychology Series: Stereotyping and Prejudice. Psychology Press; New York: [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeager DS, et al. Using design thinking to improve psychological interventions: The case of the growth mindset during the transition to high school. J Educ Psychol. 2016;108(3):374–391. doi: 10.1037/edu0000098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy MC, Dweck CS. A culture of genius: How an organization’s lay theory shapes people’s cognition, affect, and behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2010;36(3):283–296. doi: 10.1177/0146167209347380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castleman BL, Owen L, Page LC. Stay late or start early? Experimental evidence on the benefits of college matriculation support from high schools versus colleges. Econ Educ Rev. 2015;47:168–179. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diehl R. Final Report of the Task Force on Undergraduate Graduation Rates. Univ of Texas at Austin; Austin, TX: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Julian TA. Work-Life Earnings by Field of Degree and Occupation for People with a Bachelor’s Degree: 2011. US Census Bureau; Washington, DC: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Castleman BL, Page LC. Summer nudging: Can personalized text messages and peer mentor outreach increase college going among low-income high school graduates? J Econ Behav Organ. 2015;115:144–160. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bettinger EP, Long BT, Oreopoulos P, Sanbonmatsu L. The role of application assistance and information in college decisions: Results from the H&R Block FAFSA experiment. Q J Econ. 2012;127(3):1205–1242. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sander R, Jr, ST (2012) Mismatch: How Affirmative Action Hurts Students It’s Intended to Help, and Why Universities Won’t Admit It (Basic Books, New York)

- 37.Liptak A. 2015 Supreme court justices’ comments don’t bode well for affirmative action. NY Times. Available at www.nytimes.com/2015/12/10/us/politics/supreme-court-to-revisit-case-that-may-alter-affirmative-action.html. Accessed December 10, 2015.

- 38.Walton GM, Spencer SJ, Erman S. Affirmative meritocracy. Soc Issues Policy Rev. 2013;7(1):1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dynarski SM, Hemelt SW, Hyman JM. 2013. The Missing Manual: Using National Student Clearinghouse Data to Track Postsecondary Outcomes (Natl Bur of Econ Res, Cambridge, MA), NBER Work Pap 19552.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.