Significance

ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels are present in cardiac and smooth muscle; when activated, they relax blood vessels and decrease cardiac action potential duration, reducing cardiac contractility. Cantu syndrome (CS) is caused by mutations in KATP genes that result in overactive channels. Contrary to prediction, we show that the myocardium in both CS patients and in animal models with overactive KATP channels is hypercontractile. We also show that this results from a compensatory increase in calcium channel activity, paralleled by specific alterations in phosphorylation of the calcium channel itself. These findings have implications for the way the heart compensates for decreased excitability and volume load in general and for the basis of, and potential therapies for, CS specifically.

Keywords: KATP, transgenic, cardiovascular system, KCNJ8, Kir6.1

Abstract

Cantu syndrome (CS) is caused by gain-of-function (GOF) mutations in genes encoding pore-forming (Kir6.1, KCNJ8) and accessory (SUR2, ABCC9) KATP channel subunits. We show that patients with CS, as well as mice with constitutive (cGOF) or tamoxifen-induced (icGOF) cardiac-specific Kir6.1 GOF subunit expression, have enlarged hearts, with increased ejection fraction and increased contractility. Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings from cGOF or icGOF ventricular myocytes (VM) show increased basal L-type Ca2+ current (LTCC), comparable to that seen in WT VM treated with isoproterenol. Mice with vascular-specific expression (vGOF) show left ventricular dilation as well as less-markedly increased LTCC. Increased LTCC in KATP GOF models is paralleled by changes in phosphorylation of the pore-forming α1 subunit of the cardiac voltage-gated calcium channel Cav1.2 at Ser1928, suggesting enhanced protein kinase activity as a potential link between increased KATP current and CS cardiac pathophysiology.

Cantu syndrome (CS), characterized by hypertrichosis, osteochondrodysplasia, and multiple cardiovascular abnormalities (1), is caused by gain-of-function (GOF) mutations in the genes encoding the pore-forming (Kir6.1, KCNJ8) and regulatory (SUR2, ABCC9) subunits of the predominantly cardiovascular isoforms of the KATP channel (2–5). Because the same disease features arise from mutations in either of these subunits, it is concluded that CS arises from increased KATP channel activity, as opposed to any nonelectrophysiologic function of either subunit.

However, this conclusion does not provide immediate explanation for many CS features. In the myocardium, for example, acute activation of KATP channels results in shortening of the action potential (AP), with concomitant reduction of both calcium entry and contractility (6). The naïve prediction in CS would therefore be that KATP GOF mutations should shorten the AP, reduce contractility, and reduce cardiac output. We previously reported high cardiac output with low systemic vascular resistance in CS (7). Cantu syndrome cardiac pathology is therefore opposite to prediction, and also unlike classical hypertrophic or dilated cardiomyopathies, in that the ventricle is dilated, but there is increased cardiac output. Here we characterize CS cardiac pathology in patients, and explore the mechanistic basis using mice that express KATP GOF mutant subunits in the heart and vasculature.

Results

Low Blood Pressure in CS Patients.

Eleven CS individuals (five male, six female, aged 17 mo to 47 y), all harboring ABCC9 mutations (Table S1), participated in CS research clinics at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. Five had been previously followed at this institution (7) and the remainder were enrolled via the CS Interest Group (www.cantu-syndrome.org). Patient demographic data, genotype, and available cardiac historical, physical, and test information are summarized in Table S1. Most patients had no recalled cardiac symptomatology, although prior office notes revealed episodes of chest pain, fatigue, shortness of breath, and exercise intolerance associated with pericardial effusion. Additionally, three patients (cs002, cs004, cs005) reported palpitations and exercise intolerance. One of these (cs004) also had symptoms with orthopnea, resulting from “idiopathic” high-output state and atrial fibrillation. Five patients had patent ductus arteriosus that required surgical ligation or catheter-based closure, two had significant pericardial effusions, three had been diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension, and five had histories of lower extremity edema. All patients had full but noncollapsing peripheral pulses. All but one patient (cs004, who was on several medications; Table S1) had supine systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP) that was well below mean for age (Table S1) [mean age: 16.6 ± 13.5; systolic BP: 90.5 ± 12.8 mmHg; diastolic BP: 58.2 ± 6.2 mmHg; heart rate (HR): 85 ± 17 beats per minute (bpm)] (8). Despite these low BP values, no patient demonstrated orthostatic HR or BP changes. There were relatively few cardiac findings on physical examination, with the exception of one patient with a diastolic murmur (cs004) at the apex. Electrocardiograms revealed first-degree atrioventricular (AV) block in four patients, fascicular block in two, and T-wave abnormalities (T-wave axis 180° displaced from QRS axis and morphologic abnormalities) in seven patients, but no evidence of QT shortening or correct QT (QTc) prolongation (Table S2).

Table S1.

Patient genotype and history

| cs001 | cs002 | cs003 | cs004 | cs005 | cs006 | cs007 | cs008 | cs009 | cs010 | cs011 | |

| Age (y), gender | 12.3 M | 17.9 F | 23.4 F | 47.0 F | 18.1 F | 12.8 M | 32.0 F | 1.5 F | 4.0 M | 6.0 M | 8.0 M |

| Height (cm) | 152.1 | 155.3 | 163.7 | 181.2 | 157.8 | 139.8 | 177 | 81.5 | 109 | 121.2 | 143.3 |

| Height (%) for age | 75 | 10 | Adult | Adult | 10–25 | <5 | Adult | 50–75 | 90–95 | 75–90 | >95 |

| Weight (kg) | 45.6 | 45.4 | 57.2 | 100.1 | 68.3 | 30.7 | 87.6 | 10.48 | 21.3 | 23.4 | 39.7 |

| Amino acid substitution | R1154W | R1154Q | R1154Q | R1154Q | R1154W | H1005L | R1116C | R1116C | R1116C | R1116C | R1116H |

| History | |||||||||||

| Orthopnea | — | — | — | Yes | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Exercise intolerance | — | — | — | Yes | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Symptoms with exertion | — | — | — | Yes | Occasionally | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Palpitations | — | Yes | — | Yes | Yes | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Presyncope | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Syncope | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Fatigue | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Headaches | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | — | — | — | — | |

| Rhythm abnormalities | No | No | No | AF | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| PDA | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Pericardial effusion | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Pulmonary hypertension | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Lower extremity edema | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Medications | Atenolol, Cardizem Lasix, spironolactone | Enalapril, Focalin | Sildenafil | ||||||||

| Physical | |||||||||||

| HR (bpm) | |||||||||||

| Supine | 78 | 72 | 74 | 92 | 66 | 100 | 75 | 126 | 90 | 90 | 72 |

| Upright | 84 | 88 | 88 | 92 | 76 | 104 | 83 | 120 | 102 | 112 | 96 |

| HR norms for age (10–90%) | 62–96 | 62–96 | 60–80 | 60–80 | 62–96 | 62–96 | 60–80 | 98–135 | 86–123 | 81–117 | 74–111 |

| BP (mmHg) | |||||||||||

| Supine | 92/62 | 88/52 | 92/70 | 116/60 | 88/50 | 74/56 | 106/64 | 72/50 | 84/56 | 85/60 | 98/60 |

| Upright | 96/66 | 92/58 | 88/62 | 108/70 | 98/62 | 74/50 | 102/60 | 94/64 | 74/56 | 72/54 | 100/62 |

| Orthostatic changes: BP | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Orthostatic changes: HR | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| BP norms for age (50–99%) | 108–133/63–90 | 109–133/65–90 | 120–140/80–90 | 120–140/80–90 | 120–140/80–90 | 101–126/59–86 | 120–140/80–90 | 90–114/42–67 | 95–120/51–78 | 98–123/53–80 | 102–127/61–88 |

| Age at which systolic BP represents 50th percentile | 4-y-old boy | 4-y-old girl | 6-y-old girl | Normal adult | 4-y-old girl | <1-y-old boy | 11-y-old girl | 1-y-old girl | <1-y-old boy | <1-y-old boy | 8-y-old boy |

| CV findings | None | None | None | Chronic venous changes | None | None | Chronic venous changes | None | None | None | None |

AF, atrial fibrillation; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus.

Table S2.

Human electrocardiological findings

| cs001 | cs002 | cs003 | cs004 | cs005 | cs006 | cs007 | cs008 | cs009 | cs010 | cs011 | |

| Age (y) | 12.3 | 17.9 | 23.4 | 47 | 18.1 | 12.8 | 32 | 1.5 | 4 | 6 | 8 |

| HR (bpm) | 90 | 73 | 71 | 70 | 73 | 87 | 75 | 114 | 132 | n.d. | 91 |

| Rhythm | NSR | NSR | NSR | NSR | NSR | NSR | NSR | NSR | NSR | NSR | |

| P axis (°) | 76 | 46 | 45 | 37 | 36 | 40 | 37 | 43 | 44 | 56 | |

| QRS axis (°) | 81 | 110 | 51 | −36 | 68 | 109 | 20 | 10 | 69 | 113 | |

| T axis (°) | 77 | 25 | −42 | −42 | 21 | 81 | 30 | 58 | 9 | 76 | |

| PR interval (ms) | 170 | 190 | 148 | 208 | 154 | 108 | 210 | 150 | 150 | 170 | |

| QRS interval (ms) | 96 | 82 | 96 | 114 | 94 | 82 | 96 | 86 | 78 | 96 | |

| RR interval (ms) | 690 | 816 | 808 | 848 | 826 | 612 | 810 | 560 | 440 | 690 | |

| QT interval (ms) | 330 | 390 | 356 | 400 | 388 | 366 | 400 | 320 | 290 | 330 | |

| QTc interval (ms) | 404 | 430 | 387 | 432 | 427 | 440 | 447 | 440 | 430 | 440 | |

| T-wave abnormality | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes (mild flattening) | Yes (right precordial) | No | No | |

| Conduction delay | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Early repolarization | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | |

| QRS axis norm for age | 9–128 | 9–128 | −10–95 | −31–90 | 9–128 | 9–128 | −25–91 | 89–152 | 10–139 | 6–116 | |

| QRS interval norm for age | 40–90 | 69–107 | 69–107 | 69–107 | 69–107 | 40–90 | 69–107 | 30–80 | 30–70 |

HR normative values from Fleming et al. (62). Blood pressure norms from National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) normative blood pressure values (8). Height percentiles based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published growth charts. Normative ECG interval and axes values for age were from Moss and Allen (25). Normal QTc <450 ms; borderline QTc 450–470 (1). Values listed represent the second and 98th percentile norms for age. ND, not determined; NSR, normal sinus rhythm.

Cardiovascular Structural and Functional Characteristics in CS Patients.

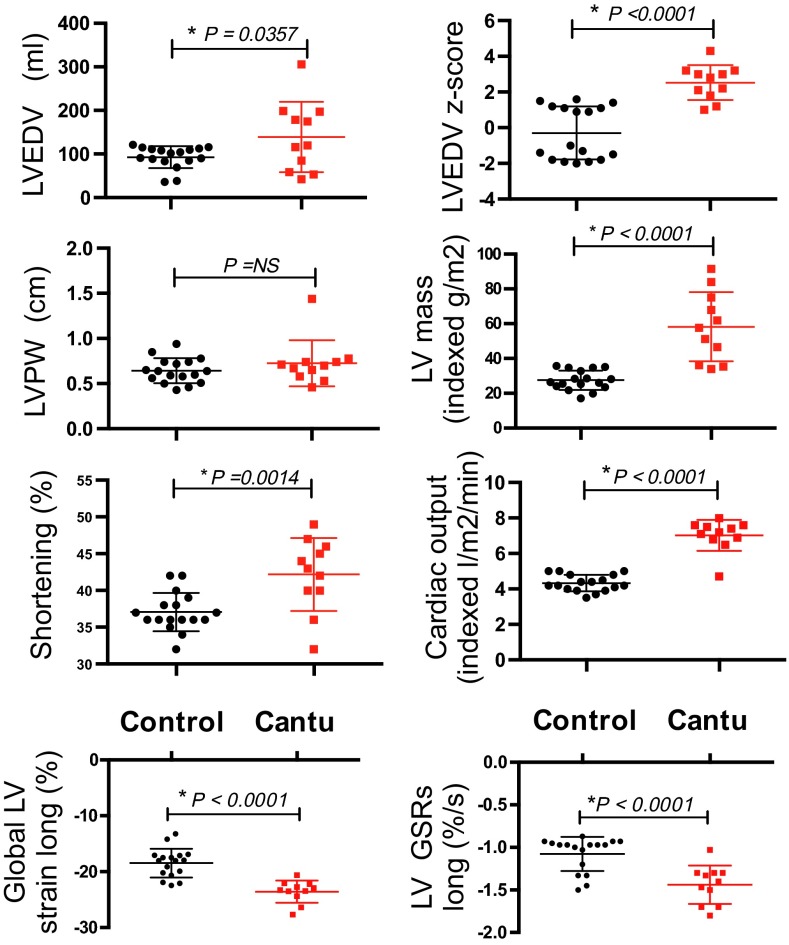

Two-dimensional color Doppler echocardiographic interrogation and strain imaging (Fig. 1, Fig. S1, and Table S3) revealed normal segmental anatomy, but markedly enlarged hearts (Fig. 1), with enhanced cardiac output and contractility, in CS patients. Left ventricular (LV) chambers were significantly dilated in CS patients, and cardiac output was markedly increased (Fig. 1). LV mass was increased but, interestingly, LV posterior wall thickness (LVPWD) was not different from controls (Fig. 1). This constellation of features is distinct from both typical hypertrophic cardiomyopathies (where LVPWD is increased) and typical dilated cardiomyopathies (where there is chamber dilation with diminished cardiac function). In part, this dilated hypercontractile phenotype could be a secondary response to chronically elevated blood volume as a result of vasodilation—a directly predicted consequence of vascular KATP GOF (9). Pulsed-wave velocity testing offers a noninvasive correlate of vascular tone. Consistent with BP measurements, there was diminished pulsed-wave velocity in CS patients (control 5.6 ± 0.9 ms−1, n = 8; CS 4.5 U+ 0.8 m/s, n = 7, P = 0.003), implying diminished vascular tone.

Fig. 1.

Enhanced cardiac volume and contractility in CS patients. Comparisons of pertinent echocardiographic measures from control and CS patients.

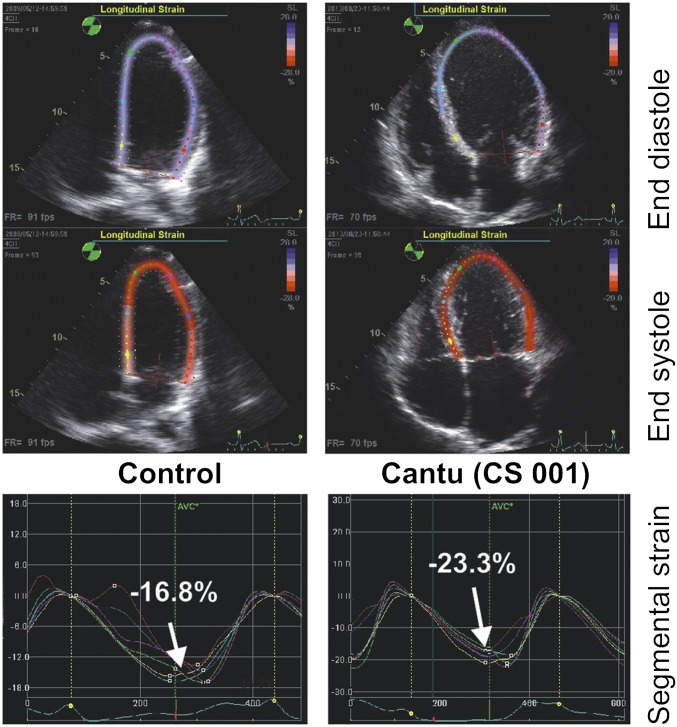

Fig. S1.

Human echocardiography. (Upper) Two-dimensional four-chamber view images of hearts from CS patient (cs001) and control individual at both end systole and end diastole. Note multicolor tag markings along the LV chamber for computing strain (deformation) measurements. (Lower) CS patient shows markedly greater strain (−22.3) than control (−16.8). Comparisons of pertinent echocardiographic measures from control and CS patients.

Table S3.

Human echocardiographic findings

| Control (n = 17) | Cantu (n = 11) | P value | |||

| Average | SD | Average | SD | ||

| BMI | 19.52 | 0.44 | 21.49 | 1.57 | NS |

| Weight (kg) | 50.94 | 16.42 | 48.74 | 27.45 | NS |

| Height (cm) | 157.75 | 30.77 | 143.64 | 29.63 | NS |

| BSA (DuBois method) | 1.5 | 0.41 | 1.36 | 0.52 | NS |

| Systolic BP | 108.29 | 12.08 | 93.64 | 13.43 | 0.00585 |

| Diastolic BP | 67.76 | 5.61 | 58.09 | 8.77 | 0.0014 |

| HR | 82.82 | 3.92 | 90.00 | 5.62 | NS |

| LVDD | 4.62 | 0.95 | 5.32 | 1.28 | NS |

| LVDD Z-score | 1.15 | 0.98 | 2.77 | 1.92 | 0.0064 |

| LVPW | 0.6429 | 0.1358 | 0.7383 | 0.1386 | NS |

| RWT | 0.28 | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0.09 | NS |

| LVMI-MMODE | 27.55 | 5.57 | 58.33 | 19.84 | <0.00001 |

| LVM-2D | 90.04 | 29.71 | 143.85 | 83.00 | 0.0208 |

| LVEDV | 93.00 | 25.35 | 139.09 | 80.57 | 0.0357 |

| LVEDV Z-score | −0.29 | 1.49 | 2.53 | 0.97 | <0.00001 |

| LVESV | 36.5 | 12.04 | 56.05 | 39.99 | NS (0.0662) |

| LVMI-2D (g/m2.7) | 23.6 | 3.2 | 60.79 | 20.06 | <0.00001 |

| Remodeling | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.82 | 0.6 | <0.00001 |

| FS (%) | 37.0 | 2.6 | 42.18 | 4.95 | 0.0014 |

Circadian Abnormalities and Low Vagal Function in CS Patients.

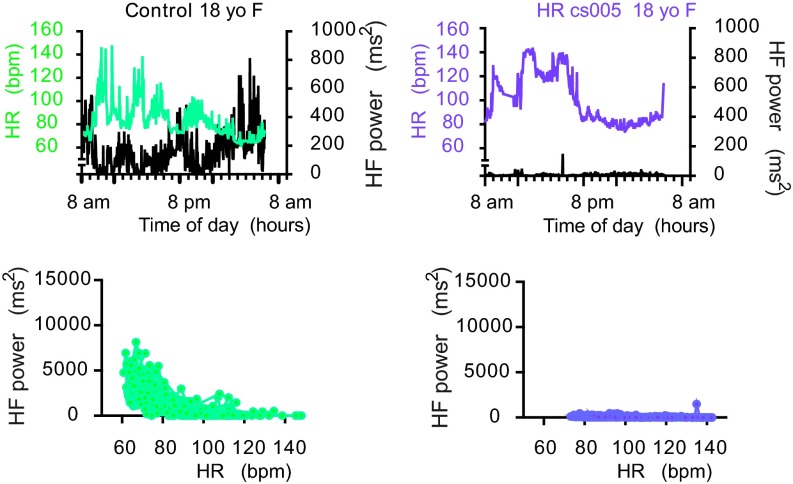

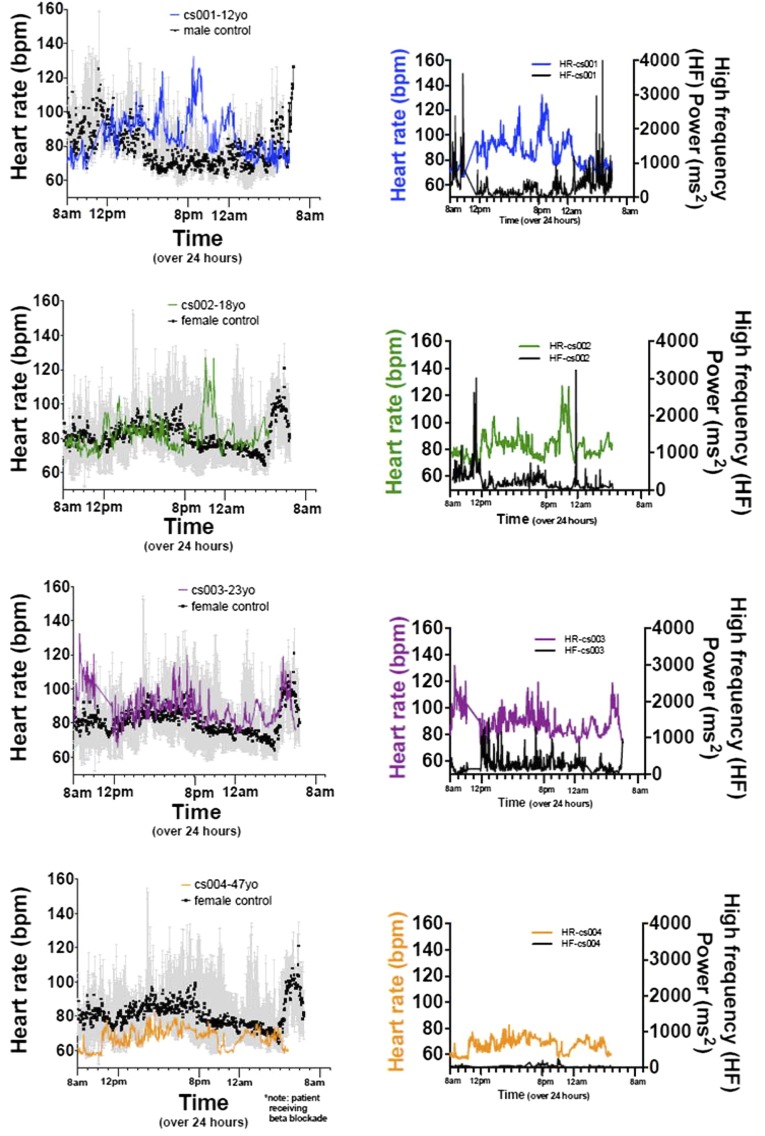

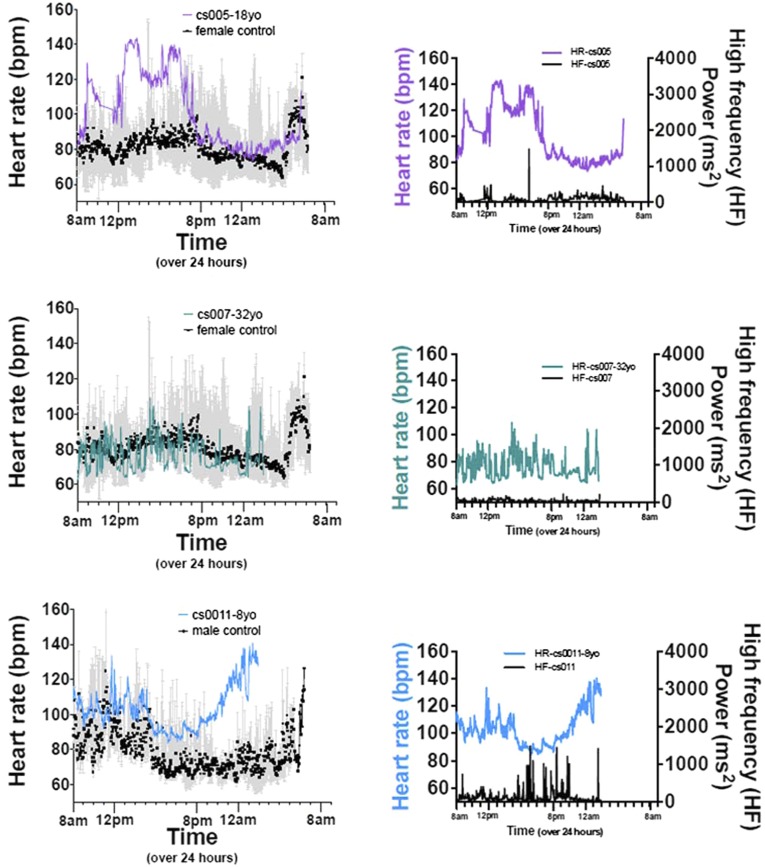

Several patients received 24-h ambulatory ECG monitoring. None demonstrated atrial or ventricular arrhythmia during the recording period. The data were subsequently used for heart rate variability analysis (HRV). Fig. 2 displays HR and high-frequency (HF) power, a marker for vagal activity, as a function of time of day, for a representative CS patient and age/sex-matched control. The control 18-y-old female shows typical circadian variation: in general, higher HR during waking hours, and significantly lower HR during sleeping hours; HF also has a circadian rhythm that is inversely related to this HR trend, rising during sleeping hours, and low during waking hours. Interestingly, all CS patients demonstrated markedly diminished HF power (Fig. 2 and Fig. S2) and generally high HR for age that failed to lower appropriately during sleeping hours (Figs. S2 and S3). These latter findings suggest a relatively elevated sympathetic activity but diminished vagal activity.

Fig. 2.

Cardiovascular control in CS patients. CS patient (cs005, 18-y-old female) and control (18-y-old female) heart rate (color) and high-frequency power (right axis, black) plotted over 24 h.

Fig. S2.

Cantu patient circadian rhythm and high-frequency power graphs.

Fig. S3.

Cantu patient circadian rhythm and high-frequency power graphs.

Enhanced Contractility in Hearts Expressing KATP GOF Mutations.

The predicted effect of KATP GOF in the myocardium itself is AP shortening and reduced contractility, whereas the predicted effect in the vasculature is reduced peripheral resistance. The above clinical evaluation of CS patients reveals physiologically low BPs, consistent with the latter prediction. However, myocardial hypercontractility and no evidence of K current-induced QT shortening on ECG are grossly opposite to prediction. We hypothesize that these features are secondary consequences of the primary predictions. Specifically, we propose that increased KATP current in either ventricular or smooth muscle myocytes will lead to lower cardiac output and decreased peripheral resistance, respectively; both of these will result in diminished tissue perfusion, which in turn will induce a systemic feedback to increase cardiac output (see, for example, Fig. 7C).

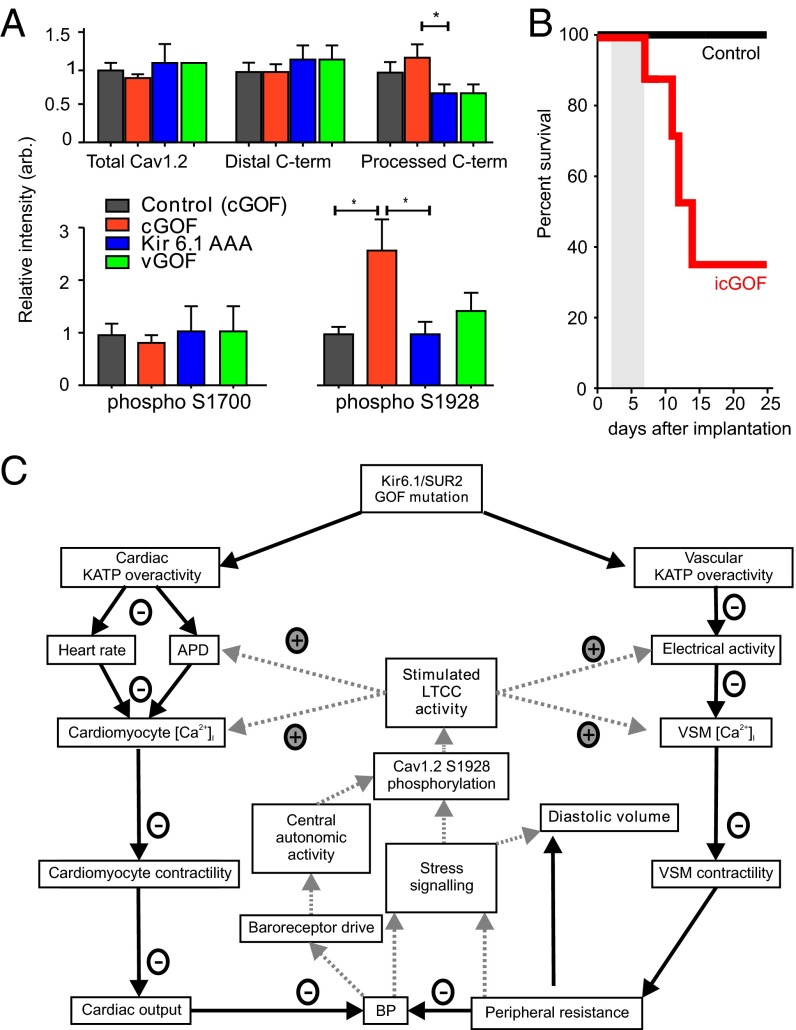

Fig. 7.

Cellular and molecular basis of Cantu syndrome. (A) Quantitation of Western blot analysis of isolated total Cav1.2a subunit protein, distal C terminus, and processed C-terminal fragments, normalized to WT protein levels in cGOF, Kir6.1[AAA], and vGOF cardiac samples, as well as relative levels of phospho-S1700 and phospho-S1928 residues. (B) Kaplan–Meier survival curve for male icGOF (n = 7) and littermate control mice (n = 6) transplanted with slow-release propranolol pellets (5 mg/21-d release) on day 0, and then induced (both icGOF and control) with tamoxifen starting on days 2–7 (gray bar). (C) Proposed mechanistic basis of Cantu syndrome. GOF mutations in either the pore-forming (KCNJ8) or accessory (ABCC9) KATP subunits will directly cause action potential (AP) shortening and reduced heart rate in cardiomyocytes and reduced excitability in smooth muscle myocytes, which will result in diminished calcium uptake, decreased contractility, and decreased cardiac output, as well as decreased peripheral resistance. Combined, these reactions would reduce blood pressure, stimulating baroreceptors and triggering PKA- or PKC-dependent stress-signaling pathways in the heart and potentially in smooth muscle. These pathways lead to phosphorylation of LTCC, specifically the Cav1.2 subunit, resulting markedly enhanced basal activity of the LTCC, enhanced contractility of the myocyte, and restored APD. In vascular smooth muscle cell, the diminished peripheral resistance will result in diminished effective tissue perfusion, giving rise to long-standing volume load on the heart, and chamber dilation.

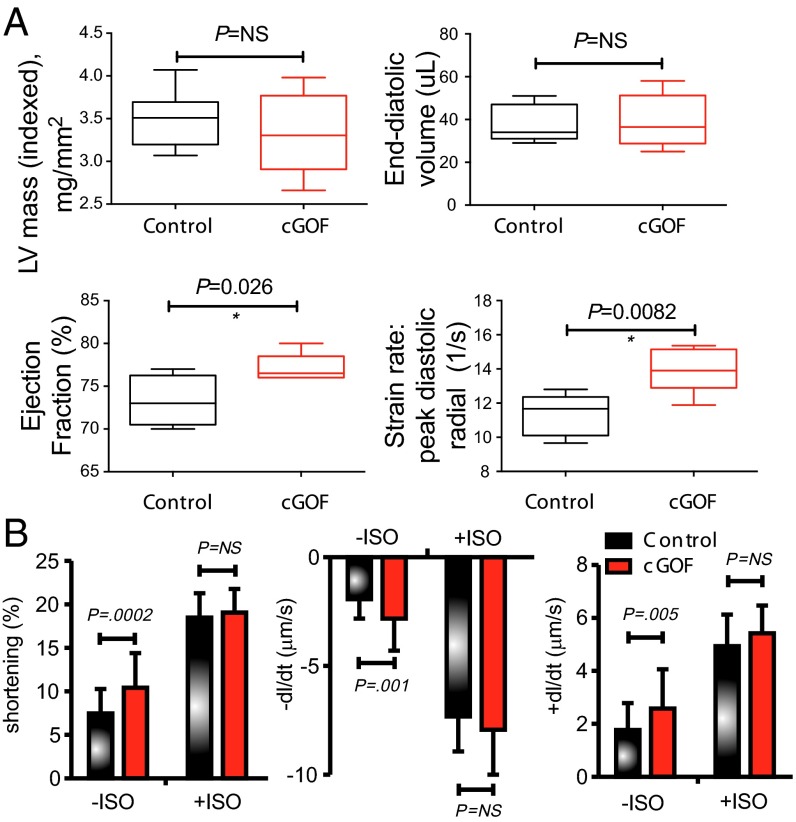

To examine these hypotheses in a tractable system, we first evaluated the cardiac consequences of Kir6.1 GOF mutations expressed in the myocardium under α-myosin heavy chain (αMHC) control in mice [constitutive GOF (cGOF) mice]. cGOF mice exhibit prolonged PR intervals, as well as episodes of junctional rhythm, and diminished AV nodal conduction, but no QT shortening (10). Echocardiography under light anesthesia (11) (Fig. 3A and Table S4) revealed normal chamber wall dimensions, but increased contractility and ejection fraction in cGOF hearts, again counter to naïve prediction, but consistent with the hypercontractile phenotype of CS patients.

Fig. 3.

Enhanced contractility in cGOF mice. (A) Echocardiographic analysis showing increased ejection fraction and strain rate in cGOF mice compared with controls. (B) Contractility parameters for isolated ventricular myocytes from cGOF and control sex-matched littermate hearts.

Table S4.

Mouse KIR 6.1 GOF (cGOF) echocardiographic findings

| Control (n = 5) | cGOF (n = 6) | P value | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Body weight (mg) | 26.7 | 4.2 | 27.8 | 3.7 | NS |

| HR (bpm) | 620.2 | 44.6 | 608.7 | 36.2 | NS |

| LVPWd (mm) | 0.842 | 0.059 | 0.820 | 0.068 | NS |

| IVSd (mm) | 0.846 | 0.065 | 0.813 | 0.056 | NS |

| LVIDd (mm) | 3.37 | 0.47 | 3.60 | 0.19 | NS |

| LVPWs (mm) | 1.44 | 0.09 | 1.41 | 0.08 | NS |

| IVSs (mm) | 1.50 | 0.06 | 1.46 | 0.16 | NS |

| LVIDs (mm) | 1.61 | 0.39 | 1.77 | 0.17 | NS |

| LVM (mg) | 96.8 | 28.7 | 101.5 | 17.7 | NS |

| LVMI | 3.60 | 0.77 | 3.64 | 0.28 | NS |

| RWT | 0.506 | 0.054 | 0.453 | 0.023 | NS (0.057) |

| FS | 52.6 | 5.0 | 50.9 | 3.7 | NS |

| EDV | 37.9 | 8.6 | 39.0 | 12.4 | NS |

| ESV | 10.3 | 2.5 | 9.1 | 3.2 | NS |

| EF | 72.9 | 2.9 | 76.9 | 1.6 | 0.017 |

| dV/dt-s | 1.0 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.3 | NS |

| dV/dt-d | 0.9 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.3 | NS |

| LVMd | 95.4 | 15.5 | 92.9 | 21.5 | NS |

| LVMdI | 3.6 | 0.3 | 3.3 | 0.5 | NS |

| SV | 27.53 | 6.43 | 29.83 | 9.33 | NS |

| CO | 16.45 | 3.26 | 17.76 | 5.52 | NS |

| S-rad | 36.753 | 4.193 | 41.504 | 6.865 | NS |

| S-long | 21.539 | 2.760 | 21.522 | 4.936 | NS |

| SR-rad-s | 9.964 | 0.876 | 10.456 | 1.267 | NS |

| SR-rad-d | 11.320 | 1.229 | 13.890 | 1.280 | 0.008 |

| SR-long-s | 8.524 | 0.751 | 8.566 | 1.783 | NS |

| SR-long-d | 12.254 | 2.461 | 11.352 | 3.200 | NS |

| Control (n = 5) | cGOF (n = 6) | ||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | P value | |

| Body weight | 26.7 | 4.2 | 27.8 | 3.7 | 0.641 |

| HR | 620.2 | 44.6 | 608.7 | 36.2 | 0.647 |

| LVPWd | 0.842 | 0.059 | 0.820 | 0.068 | 0.585 |

| IVSd | 0.846 | 0.065 | 0.813 | 0.056 | 0.394 |

| LVIDd | 3.37 | 0.47 | 3.60 | 0.19 | 0.287 |

| LVPWs | 1.44 | 0.09 | 1.41 | 0.08 | 0.630 |

| IVSs | 1.50 | 0.06 | 1.46 | 0.16 | 0.582 |

| LVIDs | 1.61 | 0.39 | 1.77 | 0.17 | 0.396 |

| LVM | 96.8 | 28.7 | 101.5 | 17.7 | 0.746 |

| LVMI | 3.60 | 0.77 | 3.64 | 0.28 | 0.908 |

| RWT | 0.506 | 0.054 | 0.453 | 0.023 | 0.057 |

| FS | 52.6 | 5.0 | 50.9 | 3.7 | 0.529 |

| EDV | 37.9 | 8.6 | 39.0 | 12.4 | 0.871 |

| ESV | 10.3 | 2.5 | 9.1 | 3.2 | 0.512 |

| EF | 72.9 | 2.9 | 76.9 | 1.6 | 0.017 |

| dV/dt-s | 1.0 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.793 |

| dV/dt-d | 0.9 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.376 |

| LVMd | 95.4 | 15.5 | 92.9 | 21.5 | 0.833 |

| LVMdI | 3.6 | 0.3 | 3.3 | 0.5 | 0.338 |

| SV | 27.53 | 6.43 | 29.83 | 9.33 | 0.653 |

| CO | 16.45 | 3.26 | 17.76 | 5.52 | 0.653 |

| S-rad | 36.753 | 4.193 | 41.504 | 6.865 | 0.211 |

| S-long | 21.539 | 2.760 | 21.522 | 4.936 | 0.995 |

| SR-rad-s | 9.964 | 0.876 | 10.456 | 1.267 | 0.483 |

| SR-rad-d | 11.320 | 1.229 | 13.890 | 1.280 | 0.008 |

| SR-long-s | 8.524 | 0.751 | 8.566 | 1.783 | 0.961 |

| SR-long-d | 12.254 | 2.461 | 11.352 | 3.200 | 0.619 |

CO, cardiac output mL/min; +dV/dt, peak rate of LV volume increase in diastole; ); −dV/dt, peak rate of LV volume decrease in systole; EDV, end-diastolic LV volume (μL) based on long-axis images; EF, ejection fraction [(EDV − ESV)/EDV]; ESV, end-systolic LV volume (μL); IVS, interventricular septum; LV FS, left ventricular fractional shortening; LLViDs, left ventricular internal dimension in systole; LViDd, left ventricular internal dimension in diastole; VPWd, left ventricular posterior wall width in diastole; LVPWs, left ventricular posterior wall width in diastole; S-long, average peak longitudinal strain (%); SR-long-d, average peak diastolic longitudinal strain rate (1/s); SR-long-s, average peak systolic longitudinal strain rate (1/s); S-rad, average peak radial strain (%); SR-rad-d, average peak diastolic radial strain rate (1/s); SR-rad-s, average peak systolic radial strain rate (1/s); SV, stroke volume [μLLVM, LV mass] (mg). Data are presented as the mean ± SD, and tests of statistical difference were computed using two-tailed Student’s t test for all parameters.

Isolated cGOF myocytes displayed diminished resting sarcomere length, significantly increased fractional shortening and increased rates of shortening and relaxation (Fig. 3B and Table S5). These features are similar to those seen in WT myocytes following exposure to isoproterenol (ISO). The subsequent effect of ISO was reduced in cGOF myocytes (Fig. 3B), consistent with the idea that cGOF myocytes are effectively “prestimulated” (12) via a pathway that is at least convergent with that responding to β-adrenergic signaling. To confirm that this prestimulation effect was not an artefactual effect of increased Kir6.1 protein expression per se, mice expressing dominant-negative Kir6.1[AAA] subunits under αMHC control (AAA) were studied (13). No significant differences in contractile parameters were seen between AAA and littermate control myocytes (Table S6).

Table S5.

Kir6.1 cGOF contractility data

| Baseline measures | Control, n = 39 | cGOF, n = 45 | P value | ||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Sarcomere length | 1.799 | 0.043 | 1.770 | 0.050 | 0.0063 |

| Contraction rate | −1.932 | 0.886 | −2.825 | 1.468 | 0.0014 |

| Contraction time | 0.291 | 0.017 | 0.289 | 0.012 | NS |

| End-systolic length | 1.664 | 0.063 | 1.585 | 0.083 | 0.000006 |

| Peak contraction amplitude | 0.135 | 0.051 | 0.185 | 0.071 | 0.0004 |

| Fractional shortening | 7.473 | 2.810 | 10.429 | 3.976 | 0.0002 |

| Time to peak contraction | 0.398 | 0.031 | 0.414 | 0.026 | 0.0115 |

| Relaxation rate | 1.768 | 1.019 | 2.578 | 1.486 | 0.0052 |

| Relaxation time | 0.462 | 0.046 | 0.486 | 0.042 | 0.0151 |

| Isoproterenol | Control, n = 30 | Kir 6.1 GOF, n = 41 | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Sarcomere length | 1.678 | 0.059 | 1.713 | 0.063 | 0.0214 |

| Contraction rate | −7.322 | 1.604 | −7.926 | 2.232 | NS |

| Contraction time | 0.280 | 0.008 | 0.279 | 0.010 | NS |

| End-systolic length | 1.368 | 0.072 | 1.386 | 0.055 | NS |

| Peak contraction amplitude | 0.309 | 0.046 | 0.327 | 0.052 | NS |

| Fractional shortening | 18.462 | 2.814 | 19.051 | 2.724 | NS |

| Time to peak contraction | 0.388 | 0.018 | 0.387 | 0.019 | NS |

| Relaxation rate | 4.937 | 1.193 | 5.421 | 1.046 | NS (0.0736) |

| Relaxation time | 0.456 | 0.038 | 0.454 | 0.034 | NS |

All times in milliseconds, all lengths in μm, and all rates in μm/milliseconds.

Table S6.

Kir6.1 AAA contractility data

| Baseline measures | Control, n = 34 | Kir 6.1 AAA, n = 35 | P value | ||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Sarcomere length | 1.815 | 0.025 | 1.822 | 0.037 | NS |

| Contraction rate | −2.001 | 0.909 | −2.499 | 1.313 | NS |

| Contraction time | −0.094 | 0.018 | −0.098 | 0.016 | NS |

| End-systolic length | 1.692 | 0.057 | 1.674 | 0.086 | NS |

| Peak contraction amplitude | 0.124 | 0.047 | 0.148 | 0.076 | NS |

| Fractional shortening | 6.826 | 2.577 | 8.109 | 4.175 | NS |

| Time to peak contraction | 0.133 | 0.015 | 0.134 | 0.013 | NS |

| Relaxation rate | 1.739 | 1.065 | 2.153 | 1.576 | NS |

| Relaxation time | 0.057 | 0.013 | 0.056 | 0.016 | NS |

| Isoproterenol | Control, n = 20 | Kir 6.1 AAA, n = 27 | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Sarcomere length | 1.752 | 0.048 | 1.729 | 0.066 | NS |

| Contraction rate | −8.130 | 1.190 | −8.210 | 1.409 | NS |

| Contraction time | −0.096 | 0.012 | −0.089 | 0.010 | 0.040 |

| End-systolic length | 1.425 | 0.044 | 1.395 | 0.067 | NS |

| Peak contraction amplitude | 0.327 | 0.043 | 0.334 | 0.037 | NS |

| Fractional shortening | 18.654 | 2.206 | 19.346 | 2.127 | NS |

| Time to peak contraction | 0.128 | 0.015 | 0.123 | 0.015 | NS |

| Relaxation rate | 6.188 | 1.225 | 6.444 | 1.184 | NS |

| Relaxation time | 0.058 | 0.011 | 0.049 | 0.008 | 0.003 |

All times in milliseconds, all lengths in μm, and all rates in μm/milliseconds.

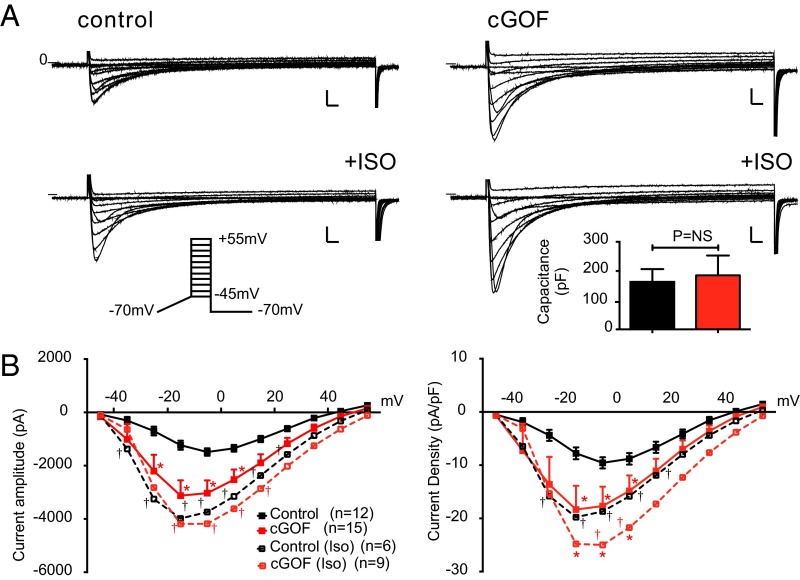

KATP GOF Myocytes Demonstrate Increased LTCC.

Cardiac excitation–contraction (EC) coupling depends on Ca entry via the L-type Ca2+ current (LTCC), which is modulated by phosphorylation in response to β-adrenergic and other neurohumoral inputs. Prestimulated cGOF myocyte contractility is consistent with enhancement of such modulation. Cell size, assessed by cell capacitance, was normal in cGOF myocytes, but baseline LTCC amplitude and density were double those of control myocytes (Fig. 4B). Commensurate with the idea that cGOF myocytes were prestimulated, LTCC amplitudes and densities were markedly increased by ISO in control myocytes but much less so in cGOF myocytes (Fig. 4). There was a slight shift in voltage dependence in the baseline cGOF current–voltage (I/V) relationship, again similar to that in control I/V curves after ISO exposure.

Fig. 4.

Enhanced LTCCs in cGOF myocytes. (A) Representative families of Ca2+ current obtained from control (Left) or cGOF (Right) mice. Na+ and T-type Ca2+ channels were inactivated by slow voltage ramp from holding potential of −70 to −45 mV, and then voltage was stepped to +55 mV in 10-mV increments. The identical protocol was used to elicit ICa following exposure to ISO (1 mM). (B) Peak ICa amplitude and ICa density as a function of voltage (mean ± SEM). (Inset) Mean capacitance in each case. (Scale bars, 500 pA and 20 ms.) Solid lines here and in following figures indicate currents in baseline, dotted lines in ISO; asterisks indicate significance of cGOF vs. control in each condition (two-way ANOVA, P < 0.001). In this figure only, daggers indicate significance of ISO vs. baseline for control (black) and cGOF (red).

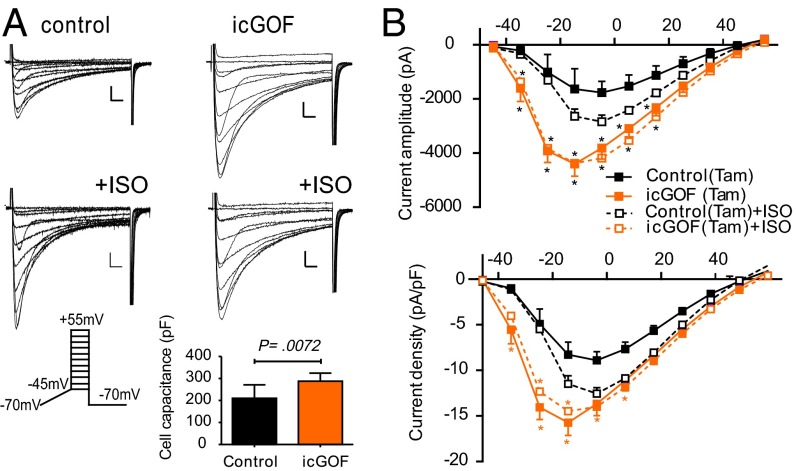

Because the Kir6.1 GOF transgene is constitutively activated in cGOF hearts, the above changes in LTCC properties might be developmentally induced. To examine the temporal link between expression of KATP GOF and consequent increases in LTCC, we assessed cardiomyocytes in which GOF was induced postnatally, rather than developmentally [tamoxifen-induced GOF (icGOF)] by crossing Kir6.1[G343D] and tamoxifen-inducible Myh6-Cre mice (14). Double-transgenic icGOF and littermate controls were treated with tamoxifen for 5 d; ventricular myocytes were isolated, and LTCC recorded, on day 6. Recorded icGOF myocytes were larger than control myocytes but, even controlling for this, icGOF LTCC density was still dramatically increased at baseline (Fig. 5). Again, as in cGOF myocytes, ISO significantly stimulated LTCC in control but not icGOF myocytes. These experiments further confirm remodeling of LTCC in response to Kir6.1 GOF, and demonstrate that this can occur in adult animals and rapidly (within hours or days) following transgene induction, implying that such responses are physiologically, not developmentally, mediated.

Fig. 5.

Enhanced LTCCs in inducible icGOF ventricular myocytes. (A) Representative families of Ca2+ current obtained from either control (Left) or icGOF (Right) at baseline and in presence of ISO. Protocols as in Fig. 4. (B) Peak ICa amplitude and ICa density plotted as a function of voltage (mean ± SEM). (Inset) Mean capacitance in each case. (Scale bars, 500 pA and 10 ms.)

Vascular KATP GOF Expression Results in Enlarged Hearts and Increased LTCC.

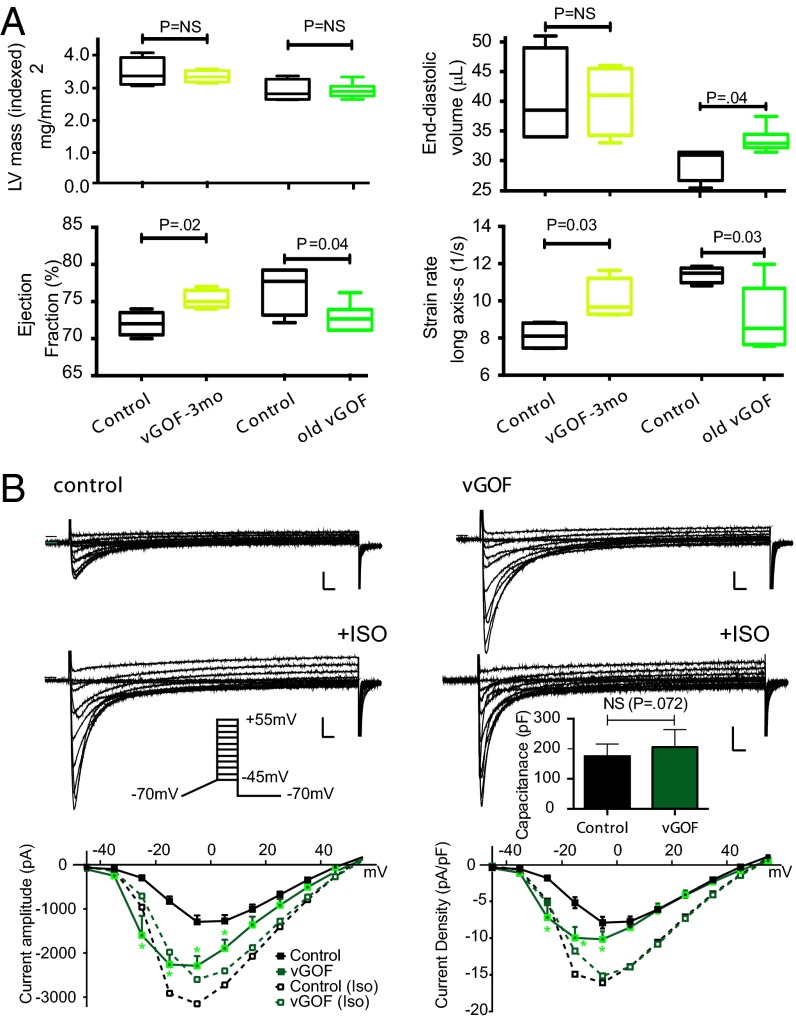

Kir6.1 and SUR2 are prominently expressed in vascular smooth muscle (VSM). VSM expression of KATP GOF under smooth muscle (SM)-MHC promoter control reduces vascular contractility, resulting in a chronically vasodilated state with low systolic and diastolic BP (9). Young vGOF mice, induced with tamoxifen at 2 mo and studied by echocardiography 1 mo later, revealed no significant changes in cardiac structural parameters, but did exhibit enhanced cardiac contractility (Fig. 6A). A second cohort of vascular-specific expression (vGOF) mice in which expression had been induced for more than 6 mo (old vGOF) showed significant chamber dilation and now showed diminished contractility (Fig. 6A and Table S7). Consistent with these older vGOF echocardiographic findings, baseline LTCC in vGOF myocytes was elevated, although not as dramatically as in cGOF or icGOF mice, and both vGOF and control LTCC increased following ISO (Fig. 6B). Interestingly, the baseline I–V relationship was left-shifted by ∼10 mV (Fig. 6B) in vGOF myocytes.

Fig. 6.

Dilated heart and enhanced LTCCs in vGOF cardiac muscle. (A) Echocardiographic features of vGOF mice at 3 mo and >6 mo of age. (B) Representative Ca2+ currents obtained from either control (Left) or vGOF (Right) cardiomyocytes. Protocols as in Fig. 4. Peak ICa amplitude and ICa density plotted as a function of voltage (mean ± SEM). (Inset) Mean capacitance in each case. (Scale bars, 500 pA and 20 ms.)

Table S7.

Comparison of echocardiographic parameters in old cohort of vGOF mice

| Control (n = 4) | vGOF (n = 6) | P value | |||

| Age (d) | 276.5 | 109.1 | 308.0 | 97.6 | 0.6454 |

| HR | 635.3 | 23.6 | 646.2 | 12.2 | 0.3586 |

| LVPWd | 0.85 | 0.10 | 0.87 | 0.11 | 0.8104 |

| IVSd | 0.90 | 0.10 | 0.89 | 0.10 | 0.8350 |

| LVIDd | 3.17 | 0.28 | 3.31 | 0.21 | 0.3958 |

| LVPWs | 1.498 | 0.192 | 1.422 | 0.230 | 0.6023 |

| IVSs | 1.510 | 0.153 | 1.478 | 0.135 | 0.7391 |

| LVIDs | 1.50 | 0.16 | 1.71 | 0.19 | 0.1124 |

| LVM | 90.58 | 13.37 | 96.84 | 8.68 | 0.3909 |

| LVMI | 3.06 | 0.88 | 3.12 | 0.39 | 0.8967 |

| RWT | 0.557 | 0.103 | 0.534 | 0.092 | 0.7186 |

| FS | 52.7 | 1.8 | 48.5 | 3.8 | 0.0736 |

| EDV | 28.75 | 2.87 | 32.61 | 2.04 | 0.0367 |

| ESV | 6.63 | 1.70 | 8.94 | 1.01 | 0.0255 |

| EF | 76.3 | 3.6 | 72.3 | 1.9 | 0.0519 |

| dV/dt-s | 0.843 | 0.070 | 0.890 | 0.063 | 0.3066 |

| dV/dt-d | 0.869 | 0.166 | 0.962 | 0.131 | 0.3518 |

| LVMd | 76.1 | 9.0 | 79.7 | 10.5 | 0.5984 |

| LVMdI | 2.90 | 0.33 | 2.91 | 0.23 | 0.9720 |

| SV | 22.13 | 2.06 | 23.67 | 1.17 | 0.1648 |

| CO | 13.83 | 1.54 | 15.10 | 0.99 | 0.1482 |

| S-rad | 40.88 | 3.63 | 37.13 | 1.40 | 0.0476 |

| S-long | 22.81 | 0.75 | 21.74 | 2.18 | 0.3811 |

| SR-rad-s | 11.9 | 1.7 | 10.6 | 1.0 | 0.1775 |

| SR-rad-d | 14.6 | 2.1 | 14.3 | 1.5 | 0.7943 |

| SR-long-s | 11.5 | 0.4 | 9.1 | 1.8 | 0.0325 |

| SR-long-d | 12.9 | 1.8 | 12.5 | 1.9 | 0.7874 |

Increased Cav1.2 Protein Phosphorylation in Kir6.1 GOF Hearts.

The LTCC in mature ventricular myocytes is conducted by Cav1.2 channels, composed of a pore-forming α1 subunit in association with α2δ, β, and possibly γ subunits (15). In the heart, the large C-terminal domain of the 250-kDa α1 subunit is proteolytically processed, resulting in a complex of the core Cav1.2 protein plus its noncovalently bound distal C terminus (16), a potent autoinhibitor of channel activity (17). β-Adrenergic stimulated phosphorylation of the Cav1.2 channel relieves this autoinhibition and enhances LTCC and myocyte contractility, in response to sympathetic signaling (18–20). We found no change in the level of full-length Cav1.2 channel protein, proteolytically processed Cav1.2 protein, or distal C-terminal protein, between cGOF and control hearts (Fig. 7A). We investigated two phosphorylation sites on Cav1.2 channels that have been identified in intact ventricular myocytes using phosphospecific antibodies (Ser1700 at the interface between the distal and proximal C-terminal domains and Ser1928 in the distal C-terminal domain). Phosphorylation of Ser1700 by PKA is directly implicated in β-adrenergic regulation of Cav1.2 channels (18, 19), whereas phosphorylation of Ser1928 may correlate with PKA or PKC pathway activity (18, 21). We found no significant change in phosphorylation of Ser1700 in cGOF, but Ser1928 phosphorylation was increased approximately twofold in cGOF mice (Fig. 7A), and ∼1.25-fold in vGOF mice. Because Ser1928 is also a substrate for phosphorylation by PKC (22), phosphorylation of this site by either PKA or PKC signaling pathways may be involved in persistent increase in basal activity, and consequent loss of β-adrenergic stimulation of Cav1.2 channels in CS.

Intolerance of β-Blockade in icGOF Animals.

To further explore the mechanistic basis of Cantu disease and directly assess whether β-adrenergic signaling is required for adaptation to KATP GOF in the heart, we chemically ablated sympathetic signaling in icGOF and littermate control mice by implanting adult (12- to 32-wk-old) animals with slow-release propranolol pellets, and then initiating transgene expression with tamoxifen 2–7 d later. The majority of icGOF mice treated with propranolol pellets died within 2 wk of transgene induction, but no deaths were observed in littermate controls (Fig. 7B). Though further mechanistic details remain to be elucidated, these data are a striking indication that adrenergic signaling is required for adaptation to KATP GOF induction.

Discussion

CS and Cardiovascular Disease.

KATP channels are heterooctameric complexes of pore forming Kir6.1 or Kir6.2 subunits and regulatory SUR1 or SUR2 subunits (23). ABCC9 (SUR2) and KCNJ8 (Kir6.1) are prominently expressed in cardiac myocytes, VSM, and vascular endothelial cells (23), suggesting that cardiovascular features will predominate in CS. We show that CS patients have dilated LVs, increased cardiac output and ejection fraction, and increased myocardial contractility. LV mass is increased compared with controls, but LV wall thicknesses are normal. Such findings are distinct from hallmarks of either hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) or dilated cardiomyopathy; the former typically demonstrates thickened LV chamber walls with hypercontractile function, whereas the latter demonstrates a dilated LV chamber with diminished cardiac function. Distinguishing between these cardiac phenotypes is critical, because standard therapies for HCM, for example, might actually worsen a Cantu patient’s clinical status.

High cardiac output states such as we observe can arise from chronic vasodilation, and can lead to LV volume overload and subsequent chamber dilation (24–27). Vital statistic and echocardiographic data support the hypothesis that CS patients are vasodilated, but in a compensated high cardiac output state. Though it is controversial to term BP as clinically low in an asymptomatic patient, systolic and diastolic BPs were greatly diminished compared with mean for age.

Feedback Control via L-Type Ca Current in Compensated Cardiac Function.

Gain of K+ channel function in blood vessels would be predicted to cause reduced contractility and vasodilation, and in the heart to shorten APs, reducing Ca2+ entry and contractility. Available clinical data regarding ECG phenotype in CS patients is limited, but there is no evidence for AP shortening (10). The high cardiac output state evident by echocardiography is also not naively predicted and leads us to postulate that feedback response to both the heart and vasculature remodels EC coupling to produce the unexpected hypercontractile function (Fig. 7). In mice, echocardiograms and isolated myocyte contractility studies reveal that such compensation does indeed occur: cardiac contractility is increased, concomitant with increased LTCC. Isolated cGOF myocytes reveal basal hypercontractility and elevated LTCC, but similar maximal contractility and LTCC after ISO exposure to control, whereas old vGOF myocytes also show some increase in baseline LTCC. Direct analysis of LTCC in hearts of CS patients is not feasible, but there are indirect suggestions of similarly enhanced basal LTCC in the ambulatory ECG data: higher than normal heart rates, as well as blunted heart rate variability and T-wave abnormalities (Fig. 2).

In the presence of ISO, LTCC densities in cGOF or icGOF myocytes are not significantly different from control (Figs. 4 and 5) (12). This lack of ISO response is consistent with chronic in vivo activation of signaling pathways that result in prestimulation. This prestimulation must be a consequence of the initial defect; that is, the gain of KATP conductance, which we suggest will indeed be a reduced cardiac output, but that this results in activation of adrenergic or parallel signaling pathways. We previously showed that basal and ISO-stimulated cAMP concentrations are not altered in transgenic Kir6.2 GOF hearts that also show prestimulation (12). Cardiac LTCC can be increased by PKA activation (28–30), but also by PKC in response to α-adrenergic and endothelin-1–dependent signaling (31–35). PKC overexpression may result in diminished LTCC current in some circumstances (36), although dialysis of critical LTCC-associated proteins may confound results in whole-cell patch-clamp experiments (32). Both PKA and PKC modulation of LTCC (22, 37) are mediated by phosphorylation of CaV1.2 serine residues on the pore or accessory subunits (18–20, 38). The identity of relevant residues phosphorylated in response to adrenergic signaling remains an active area of investigation. Ser1700 and Ser1928 phosphorylation of Cavα1.2 have both been demonstrated, but Ser1928 may also be phosphorylated by PKC (35, 39), and Ser1700 may also be a target of CaMKII (18, 40). Our analysis implicates Ser1928 phosphorylation as a marker of the response to KATP GOF but not Ser1700. Though Ser1928 phosphorylation may not itself be directly involved in the enhancement of LTCC, it is suggestive that PKC or PKA pathways may ultimately be activated.

Feedback Response to Vascular Defects in CS.

Two distinct effects were observed on cGOF and icGOF LTCC: left-shift in activation and increased current density. We also observed a left-shift of voltage dependence of LTCC in vGOF, but only a mild increase in current density, and a nonsignificant increase in Ser1928 phosphorylation. In contrast, older vGOF animals exhibited increased diastolic volume, as observed in CS patients. Vascular KATP GOF results in increased smooth muscle KATP current and diminished BP (9), providing a potentially direct explanation for the markedly low-for-age BPs in CS patients; this also provides a systemic mechanism that may link the primary vGOF phenotype to secondary consequences in the heart: vascular KATP GOF expression results in vasodilation that will ultimately result in a long-standing volume load, evidenced by LV chamber dilation. Early after transgene induction (6 wk), vGOF hearts exhibit increased contractility and increased ejection fraction (Fig. 6), but end diastolic volume is increased in older vGOF animals, potentially reflecting dilation manifesting after prolonged exposure to volume overload (26).

Conclusions and Implications.

CS can arise from GOF in either Kir6.1 or SUR2 proteins of the cardiovascular KATP channel (2–5). A distinct CS cardiac pathology is characterized by high output state with enhanced cardiac contractility and enhanced chamber volume, associated with decreased vascular pulse wave velocity and low BP. Our animal studies suggest that CS cardiac pathology emerges from combined cardiac and vascular KATP GOF mutation expression (Fig. 7C). The vascular findings are readily explained by the expected molecular consequences, but KATP GOF mutations in the myocardium will tend to reduce cardiac action potential duration (APD) and decrease pacemaker activity, both of which would reduce cardiac contractility and output. The counter observation of enhanced contractility and maintained APD is explained by enhanced LTCC, with left-shifted activation and increased basal conductance, associated with enhanced phosphorylation of the PKA/PKC target residue Ser1928. These findings are consistent with compensatory chronic signaling, potentially involving adrenergic stimulation, through pathways that converge on the LTCC.

This consistent explanation for CS cardiac features raises the question of whether or how to treat them. The dramatic difference in response of icGOF and control animals to β-blockade (Fig. 7B) is consistent with adrenergic signaling being involved in at least the early compensation to KATP GOF, further suggesting that β-blockade could be a dangerous approach to treating Cantu patients. Alternately, appropriate therapies should target KATP channels directly, and the success of sulphonylurea drugs in treating neonatal diabetes, which results from GOF in the pancreatic KATP isoforms, gives promise that similar or more selective KATP antagonists may reverse some or all CS disease features.

Methods

Human studies were carried out on CS patients recruited to an annual research clinic at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. Written informed consent was provided by all patients. The study was approved by the Human Research Protection Office of Washington University School of Medicine and performed at St. Louis Children’s Hospital in St. Louis. Echocardiographic and electrocardiographic studies were performed. All animal studies complied with the standards for the care and use of animal subjects as stated in the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (41) and were reviewed and approved by the Washington University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mouse strains used included cGOF (10), αMHC-Cre (42), icGOF (tamoxifen-inducible Kir6.1[G343D] transgenic), Mer-Cre-Mer-α-MHC (43), and vGOF (9). Transgene expression was induced by 5× daily injections of 10 mg/kg tamoxifen (44). Isolated myocyte studies and isolated tissue Western blot analyses were carried out as previously described (45–48). Detailed methods are available in SI Methods.

SI Methods

Human Study Design.

Patients were recruited to an annual research clinic through invitations from cardiology and genetic outpatient clinics at St. Louis Children’s Hospital, and through the CS interest group website (www.cantu-syndrome.org). After a detailed explanation of the study, and before enrollment, written informed consent was obtained from each subject or, if under 18, their parents. We included healthy age, gender, and body mass index (BMI)-matched subjects from a separate study (49). The study was approved by the Human Research Protection Office of Washington University School of Medicine and performed at St. Louis Children’s Hospital.

Standard clinical histories and physical examinations, including height, weight, and head circumference measurements, were made. BP was measured by manual sphygmomanometer with appropriate cuff size and heart rate, in the resting supine position and after 2 min in the upright position, to ascertain orthostatic vital sign changes. BP measurements were repeated three times to confirm measurement accuracy, and were subsequently compared with published normative values by gender and age (www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/child_tbl.pdf).

Ventricular structure.

Transthoracic complete M-mode, 2D, and color Doppler echocardiographic examinations were performed with a commercially available ultrasound imaging system with appropriate size-phased array transducer (Vivid 7 and 9; General Electric Medical Systems). M-mode imaging of the LV in the parasternal short axis view was used to measure LV end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), LV end-systolic diameter (LVESD), end diastolic posterior wall thickness (PWT), relative wall thickness (RWT = 2 × PWT/LVEDD) (50) and LV mass. LV mass was calculated and indexed to height (LVMI) using the Devereux equation (51). To define ventricular structural phenotype, the 95th percentiles for LVMI for children older than 9 y of age (>40 g/height2.7 in females and >45 g/height2.7 in males) and the 95th percentile value for RWT for normal children and adolescents (RWT > 0.41) were used as cutoff values to categorize abnormal LV geometry (52, 53). Children categorized as having normal LV geometry had LVMI and RWT below the 95th percentiles. Concentric remodeling was defined as normal LVMI and elevated RWT, eccentric hypertrophy as elevated LVMI and normal RWT, and concentric hypertrophy as elevated LVMI and RWT (54).

Ventricular function.

Cardiac output was calculated from measured aortic valve annular diameter (D), time velocity integral (TVI) of pulse-wave Doppler velocity in LV outflow tract, and HR (beats per minute) using equation: π × (D/2)2 × TVI × HR × 100 (l per min), averaged for three consecutive cardiac cycles and indexed against body surface area (BSA) (l⋅min−1⋅m2) (55). In addition, M-mode imaging was used to measure LV fractional shortening [FS = (LVEDD – LVESD)/LVEDD], and 2D imaging was used to measure LV ejection fraction using the modified Simpson method. Myocardial mechanics were evaluated by measurement of strain (dimensionless measure of myocardial deformation) and strain rate (time derivative of strain), which correlates with LV peak elastance, reflecting contractile performance (56). Strain and strain rate were analyzed by 2D speckle-tracking echocardiography. This technique is noninvasive, minimally angle-dependent, and has been validated against sonomicrometry and tagged MRI (57, 58). LV global longitudinal strain (GLS) and rates (GLSR) were measured from grayscale 2D apical images of the LV (four-, three-, and two-chamber views) (57). The peak LV GLS, systolic GLSR, early diastolic GLSR, and late diastolic GLSR values were calculated using EchoPAC (General Electric Medical Systems) software, by averaging the GLS and GLSR measurements from the three apical views.

Characterization of heart rate and rhythm.

Cardiac rhythm and conduction were assessed by 15-lead surface ECG and rhythm strip, and two-lead 24-h ambulatory ECG recording. Data were loaded onto a MARS PC Holter Analyzer (GE Medical Systems) and analyzed using standard research Holter techniques. Time-domain HRV was used to measure the statistical properties of NN interval variation over various time scales (from beat-to-beat to 24 h). Frequency domain HRV using power spectral analysis (fast Fourier transforms) was used to quantify variance (power) of heart rate as a function of underlying physiological oscillations, reflecting different aspects of the regulatory action of the autonomic system on the heart (59).

Animal Studies.

Generation and strains of transgenic mice.

All procedures complied with the standards for the care and use of animal subjects as stated in the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (41) and were reviewed and approved by the Washington University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Animals used were as follows::

cGOF.

Mice harboring a Kir6.1[G343D] mutation downstream of the β-chicken actin promoter fragment knocked into the ROSA26 locus as previously described (9) were crossed with tissue- and time-specific Cre-driver mice to yield experimental models. Germ-line cardiac-specific KATP GOF was achieved by crossing with αMHC-Cre mice, which express Cre recombinase under direction of an α-myosin heavy-chain promoter fragment (60).

icGOF.

Kir6.1[G343D] mice were crossed with Mer-Cre-Mer–regulated α-MHC promoter fragment mice (43) and transgene expression was induced in double-transgenic (TG) animals by 5× daily injections of tamoxifen (10 mg/kg) as detailed previously (44). Control single-TG littermates were treated the same way.

vGOF.

Kir6.1[G343D] mice were crossed with animals expressing CRE recombinase under control of a smooth muscle-myosin heavy-chain promoter fragment (61) (SM-MHC-Cre). Transgene expression was induced in double-TG animals by 5× daily injections of 10 mg/kg tamoxifen (44). Control single-TG littermates were treated the same way.

Kir6.1[AAA].

TG mice carrying an inducible dominant-negative mutation in the pore-forming subunit of Kir6.1 were described previously (13). Double-TG animals were obtained by crossing with αMHC-Cre driver mice as described previously.

Isolation of cardiac myocytes.

Mice were anesthetized by subcutaneous injection with 2.5% (vol/vol) Avertin (10 mL/kg, i.p.). The heart was rapidly excised, and retrogradely perfused through the aorta with Ca2+-free solution for 5 min followed by perfusion with digestion solution containing 0.8 mg/mL collagenase (Type 2; Worthington Biochemical). LV myocytes were dispersed by manual trituration. Cells were stored at room temperature in WIM solution.

Cellular electrophysiology.

Isolated myocytes were transferred into a recording chamber containing Tyrode solution (below; 5.4 mM CsCl replaces KCl) and TTX (10 μM). ISO (1 μM) was added where indicated. Patch-clamp electrodes (1–3 MΩ when filled with electrode solution) were fabricated from soda lime glass microhematocrit tubes (Kimble 73813). Cell capacitance and series resistance were determined using 5–10 mV hyperpolarizing square pulse from a holding potential of –70 mV following establishment of whole-cell recording configuration. Series resistance was electronically compensated by 60–80%. pCLAMP 9.0 software and Digidata 1200 converter were used to generate command pulses and collect data. Data were filtered at 1 kHz and recorded at 3 kHz.

Single-cell contraction measurement.

To assess contractility, unloaded cell length was measured using a video edge detection system (IonOptix). Myocytes were bathed with normal Tyrode solution and stimulated with bipolar-stimulating electrodes placed near the cell.

Solutions.

Wittenberg isolation medium.

NaCl, 116 mM; KCl, 5.3 mM; NaH2PO4, 1.2 mM; glucose, 11.6 mM; MgCl2, 3.7 mM; Hepes, 20 mM; l-glutamine, 2.0 mM; NaHCO3, 4.4 mM; KH2PO4, 1.5 mM; 1× essential vitamins (GIBCO catalog no. 12473-013); 1× amino acids (GIBCO catalog no. 11120-052); pH 7.3–7.4.

Tyrode solution with CsCl substituted for KCl.

NaCl, 137 mM; CsCl, 5.4 mM; NaH2PO4, 0.16 mM; glucose, 10 mM; CaCl2, 1.8 mM; MgCl2, 0.5 mM; Hepes, 5.0 mM; NaHCO3, 3.0 mM; pH 7.3–7.4.

Krebs–Henseleit.

NaCl, 118 mM; KCl, 4.7 mM; NaHCO3, 25 mM; NaH2PO4, 1.2 mM; MgSO4, 1.2 mM; CaCl2, 1.2 mM; glucose, 10 mM; saturated with a 95% O2–5% CO2 gas mixture; pH 7.3–7.4.

KINT.

KCl, 140 mM; K2ATP, 5 mM; Hepes, 10 mM; EGTA, 10 mM; pH 7.3–7.4.

CsINT.

CsCl, 120 mM; TEA-Cl, 20 mM; K2ATP, 5 mM; Hepes, 10 mM-; pH 7.3–7.4.

Western blot analysis.

Hearts were homogenized in buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 8.5), 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM KCl, 1% Triton X-100, 5 mM NaF, 5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM sodium-orthovanadate, plus protease inhibitors and membranes were solubilized in homogenization buffer for 2 h at 4 °C. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 20 min. Proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and analyzed by immunoblotting. Polyclonal anti-CNC1 was generated against amino acid sequences in the intracellular loop between domains II and III of Cav1.2 (821–838) and detects both the long and short forms of Cav1.2 channels (45, 46). Polyclonal CH2 antibodies were generated against peptides corresponding to residues 2051–2066 in the distal C terminus of Cav1.2 (16) and were used to detect the distal C terminus and the processed C terminus. Anti-CH3P was generated against residues 1923–1932 and recognizes phosphorylated S1928 (47). Anti-Cav1.2-pS1700 phosphospecific antibody was generated against residues 1694–7109 in the proximal C terminus (48).

Data analysis.

Unless indicated, data were analyzed using Clampfit, Microsoft Excel, and GraphPad Prism6 (GraphPad) software. Results are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical tests and P values are denoted in figures.

Acknowledgments

We thank Theresa Harter for help with animal husbandry, as well as the patients and volunteer members of the Center for the Investigation of Membrane Excitability Diseases and the Department of Pediatrics for their participation in the Cantu research clinics.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1606465113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Nichols CG, Singh GK, Grange DK. KATP channels and cardiovascular disease: Suddenly a syndrome. Circ Res. 2013;112(7):1059–1072. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.300514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harakalova M, et al. Dominant missense mutations in ABCC9 cause Cantú syndrome. Nat Genet. 2012;44(7):793–796. doi: 10.1038/ng.2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Bon BW, et al. Cantú syndrome is caused by mutations in ABCC9. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90(6):1094–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper PE, et al. Cantú syndrome resulting from activating mutation in the KCNJ8 gene. Hum Mutat. 2014;35(7):809–813. doi: 10.1002/humu.22555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brownstein CA, et al. Mutation of KCNJ8 in a patient with Cantú syndrome with unique vascular abnormalities - support for the role of K(ATP) channels in this condition. Eur J Med Genet. 2013;56(12):678–682. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nichols CG. KATP channels as molecular sensors of cellular metabolism. Nature. 2006;440(7083):470–476. doi: 10.1038/nature04711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grange DK, Lorch SM, Cole PL, Singh GK. Cantu syndrome in a woman and her two daughters: Further confirmation of autosomal dominant inheritance and review of the cardiac manifestations. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140(15):1673–1680. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;14(2 Suppl 4th report):555–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li A, et al. Hypotension due to Kir6.1 gain-of-function in vascular smooth muscle. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(4):e000365. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levin MD, et al. Electrophysiologic consequences of KATP gain of function in the heart: Conduction abnormalities in Cantu syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12(11):2316–2324. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Razani B, et al. Fatty acid synthase modulates homeostatic responses to myocardial stress. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(35):30949–30961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.230508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flagg TP, et al. Remodeling of excitation-contraction coupling in transgenic mice expressing ATP-insensitive sarcolemmal KATP channels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286(4):H1361–H1369. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00676.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tong X, et al. Consequences of cardiac myocyte-specific ablation of KATP channels in transgenic mice expressing dominant negative Kir6 subunits. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291(2):H543–H551. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00051.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agah R, et al. Gene recombination in postmitotic cells. Targeted expression of Cre recombinase provokes cardiac-restricted, site-specific rearrangement in adult ventricular muscle in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1997;100(1):169–179. doi: 10.1172/JCI119509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Catterall WA. Voltage-gated calcium channels. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3(8):a003947. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Jongh KS, et al. Specific phosphorylation of a site in the full-length form of the α1 subunit of the cardiac L-type calcium channel by adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. Biochemistry. 1996;35(32):10392–10402. doi: 10.1021/bi953023c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hulme JT, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Lin TW, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Autoinhibitory control of the CaV1.2 channel by its proteolytically processed distal C-terminal domain. J Physiol. 2006;576(Pt 1):87–102. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.111799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuller MD, Emrick MA, Sadilek M, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular mechanism of calcium channel regulation in the fight-or-flight response. Sci Signal. 2010;3(141):ra70. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fu Y, Westenbroek RE, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Basal and β-adrenergic regulation of the cardiac calcium channel CaV1.2 requires phosphorylation of serine 1700. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(46):16598–16603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419129111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fu Y, Westenbroek RE, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Phosphorylation sites required for regulation of cardiac calcium channels in the fight-or-flight response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(48):19621–19626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319421110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lemke T, et al. Unchanged β-adrenergic stimulation of cardiac L-type calcium channels in CaV 1.2 phosphorylation site S1928A mutant mice. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(50):34738–34744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804981200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamp TJ, Hell JW. Regulation of cardiac L-type calcium channels by protein kinase A and protein kinase C. Circ Res. 2000;87(12):1095–1102. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.12.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flagg TP, Enkvetchakul D, Koster JC, Nichols CG. Muscle KATP channels: recent insights to energy sensing and myoprotection. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(3):799–829. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simmons BE, et al. Sickle cell heart disease. Two-dimensional echo and Doppler ultrasonographic findings in the hearts of adult patients with sickle cell anemia. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148(7):1526–1528. doi: 10.1001/archinte.148.7.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moss AJ, Allen HD. Moss and Adams’ Heart Disease in Infants, Children, and Adolescents: Including the Fetus and Young Adult. 7th Ed Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCullagh WH, Covell JW, Ross J., Jr Left ventricular dilatation and diastolic compliance changes during chronic volume overloading. Circulation. 1972;45(5):943–951. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.45.5.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ross J, Jr, McCullagh WH. Nature of enhanced performance of the dilated left ventricle in the dog during chronic volume overloading. Circ Res. 1972;30(5):549–556. doi: 10.1161/01.res.30.5.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daaka Y, Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. Switching of the coupling of the β2-adrenergic receptor to different G proteins by protein kinase A. Nature. 1997;390(6655):88–91. doi: 10.1038/36362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuznetsov V, Pak E, Robinson RB, Steinberg SF. β2-adrenergic receptor actions in neonatal and adult rat ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 1995;76(1):40–52. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiss S, Oz S, Benmocha A, Dascal N. Regulation of cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel CaV1.2 via the β-adrenergic-cAMP-protein kinase A pathway. Circ Res. 2013;113(5):617–631. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tseng GN, Boyden PA. Different effects of intracellular Ca and protein kinase C on cardiac T and L Ca currents. Am J Physiol. 1991;261(2 Pt 2):H364–H379. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.2.H364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinberg SF. Cardiac actions of protein kinase C isoforms. Physiology (Bethesda) 2012;27(3):130–139. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00009.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woo SH, Lee CO. Role of PKC in the effects of α1-adrenergic stimulation on Ca2+ transients, contraction and Ca2+ current in guinea-pig ventricular myocytes. Pflugers Arch. 1999;437(3):335–344. doi: 10.1007/s004240050787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kelso E, Spiers P, McDermott B, Scholfield N, Silke B. Dual effects of endothelin-1 on the L-type Ca2+ current in ventricular cardiomyocytes. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;308(3):351–355. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00366-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang L, et al. Ser1928 is a common site for CaV1.2 phosphorylation by protein kinase C isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(1):207–214. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410509200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Braz JC, et al. PKC-α regulates cardiac contractility and propensity toward heart failure. Nat Med. 2004;10(3):248–254. doi: 10.1038/nm1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ter Keurs HE, Boyden PA. Calcium and arrhythmogenesis. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(2):457–506. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang L, Katchman A, Samad T, Morrow JP. β-Adrenergic regulation of the L-type Ca2+ channel does not require phosphorylation of β1C Ser1700. Circ Res. 2013;113(7):871–880. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang L, et al. Protein kinase C isoforms differentially phosphorylate CaV1.2 α1C. Biochemistry. 2009;48(28):6674–6683. doi: 10.1021/bi900322a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hofmann F, Flockerzi V, Kahl S, Wegener JW. L-type CaV1.2 calcium channels: From in vitro findings to in vivo function. Physiol Rev. 2014;94(1):303–326. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00016.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Committee on Care and Use of Laboratory Animals 1996. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), DHHS Publ No (NIH) pp 85–23.

- 42.Ray O. How the mind hurts and heals the body. Am Psychol. 2004;59(1):29–40. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sohal DS, et al. Temporally regulated and tissue-specific gene manipulations in the adult and embryonic heart using a tamoxifen-inducible Cre protein. Circ Res. 2001;89(1):20–25. doi: 10.1161/hh1301.092687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Z, York NW, Nichols CG, Remedi MS. Pancreatic β cell dedifferentiation in diabetes and redifferentiation following insulin therapy. Cell Metab. 2014;19(5):872–882. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hell JW, et al. Identification and differential subcellular localization of the neuronal class C and class D L-type calcium channel α1 subunits. J Cell Biol. 1993;123(4):949–962. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.4.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hell JW, et al. Differential phosphorylation of two size forms of the neuronal class C L-type calcium channel α1 subunit. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(26):19451–19457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hulme JT, Westenbroek RE, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Phosphorylation of serine 1928 in the distal C-terminal domain of cardiac CaV1.2 channels during β1-adrenergic regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(44):16574–16579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607294103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Emrick MA, Sadilek M, Konoki K, Catterall WA. β-adrenergic-regulated phosphorylation of the skeletal muscle CaV1.1 channel in the fight-or-flight response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(43):18712–18717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012384107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh GK, et al. Alterations in ventricular structure and function in obese adolescents with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Pediatr. 2013;162(6):1160–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lang RM, Mor-Avi V, Sugeng L, Nieman PS, Sahn DJ. Three-dimensional echocardiography: The benefits of the additional dimension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(10):2053–2069. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Devereux RB, et al. Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy: Comparison to necropsy findings. Am J Cardiol. 1986;57(6):450–458. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90771-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khoury PR, Mitsnefes M, Daniels SR, Kimball TR. Age-specific reference intervals for indexed left ventricular mass in children. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22(6):709–714. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Daniels SR, Loggie JM, Khoury P, Kimball TR. Left ventricular geometry and severe left ventricular hypertrophy in children and adolescents with essential hypertension. Circulation. 1998;97(19):1907–1911. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.19.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lang RM, et al. American Society of Echocardiography’s Nomenclature and Standards Committee Task Force on Chamber Quantification American College of Cardiology Echocardiography Committee American Heart Association European Association of Echocardiography, European Society of Cardiology Recommendations for chamber quantification. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2006;7(2):79–108. doi: 10.1016/j.euje.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lewis JF, Kuo LC, Nelson JG, Limacher MC, Quinones MA. Pulsed Doppler echocardiographic determination of stroke volume and cardiac output: Clinical validation of two new methods using the apical window. Circulation. 1984;70(3):425–431. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.70.3.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Greenberg NL, et al. Doppler-derived myocardial systolic strain rate is a strong index of left ventricular contractility. Circulation. 2002;105(1):99–105. doi: 10.1161/hc0102.101396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Singh GK, et al. Accuracy and reproducibility of strain by speckle tracking in pediatric subjects with normal heart and single ventricular physiology: A two-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography and magnetic resonance imaging correlative study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23(11):1143–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Amundsen BH, et al. Noninvasive myocardial strain measurement by speckle tracking echocardiography: Validation against sonomicrometry and tagged magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(4):789–793. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stein PK, Reddy A. Non-linear heart rate variability and risk stratification in cardiovascular disease. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2005;5(3):210–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Subramaniam A, et al. Tissue-specific regulation of the alpha-myosin heavy chain gene promoter in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(36):24613–24620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Regan CP, Manabe I, Owens GK. Development of a smooth muscle-targeted Cre recombinase mouse reveals novel insights regarding smooth muscle myosin heavy chain promoter regulation. Circ Res. 2000;87(5):363–369. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.5.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fleming S, et al. Normal ranges of heart rate and respiratory rate in children from birth to 18 years of age: A systematic review of observational studies. Lancet. 2011;377(9770):1011–1018. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62226-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]