Abstract

Importance

Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) has not been rigorously evaluated for young and middle-aged adults with chronic low back pain.

Objective

To evaluate the effectiveness for chronic low back pain of MBSR versus usual care (UC) and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

Design, Setting, and Participants

Randomized, interviewer-blind, controlled trial in integrated healthcare system in Washington State of 342 adults aged 20–70 years with CLBP enrolled between September 2012 and April 2014 and randomly assigned to MBSR (n = 116), CBT (n = 113), or UC (n = 113).

Interventions

CBT (training to change pain-related thoughts and behaviors) and MBSR (training in mindfulness meditation and yoga) were delivered in 8 weekly 2-hour groups. UC included whatever care participants received.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Co-primary outcomes were the percentages of participants with clinically meaningful (≥30%) improvement from baseline in functional limitations (modified Roland Disability Questionnaire [RDQ]; range 0 to 23) and in self-reported back pain bothersomeness (0 to 10 scale) at 26 weeks. Outcomes were also assessed at 4, 8, and 52 weeks.

Results

Among 342 randomized participants (mean age, 49 (range, 20–70); 225 (66%) women; mean duration of back pain, 7.3 years (range 3 months to 50 years), <60% attended 6 or more of the 8 sessions, 294 (86.0%) completed the study at 26 weeks and 290 (84.8%) completed the study 52weeks. In intent-to-treat analyses, at 26 weeks, the percentage of participants with clinically meaningful improvement on the RDQ was higher for MBSR (61%) and CBT (58%) than for UC (44%) (overall P = 0.04; MBSR versus UC: RR [95% CI] = 1.37 [1.06 to 1.77]; MBSR versus CBT: 0.95 [0.77 to 1.18]; CBT versus UC: 1.31 [1.01 to 1.69]. The percentage of participants with clinically meaningful improvement in pain bothersomeness was 44% in MBSR and 45% in CBT, versus 27% in UC (overall P = 0.01; MBSR versus UC: 1.64 [1.15 to 2.34]; MBSR versus CBT: 1.03 [0.78 to 1.36]; CBT versus UC: 1.69 [1.18 to 2.41]). Findings for MBSR persisted with little change at 52 weeks for both primary outcomes.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among adults with chronic low back pain, treatment with MBSR and CBT, compared with UC, resulted in greater improvement in back pain and functional limitations at 26 weeks, with no significant differences in outcomes between MBSR and CBT. These findings suggest that MBSR may be an effective treatment option for patients with chronic low back pain.

Low back pain is a leading cause of disability in the U.S. [1]. Despite numerous treatment options and greatly increased medical care resources devoted to this problem, the functional status of persons with back pain in the U.S. has deteriorated [2, 3]. There is need for treatments with demonstrated effectiveness that are low-risk and have potential for widespread availability.

Psychosocial factors play important roles in pain and associated physical and psychosocial disability [4]. In fact, 4 of the 8 non-pharmacologic treatments recommended for persistent back pain include “mind-body” components [4]. One of these, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), has demonstrated effectiveness for various chronic pain conditions [5–8] and is widely recommended for patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP). However, patient access to CBT is limited. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) [9], another “mind-body” approach, focuses on increasing awareness and acceptance of moment-to-moment experiences, including physical discomfort and difficult emotions. MBSR is becoming increasingly popular and available in the U.S. Thus, if demonstrated beneficial for CLBP, MBSR could offer another psychosocial treatment option for the large number of Americans with this condition. MBSR and other mindfulness-based interventions have been found helpful for a range of conditions, including chronic pain [10–12]. However, only one large randomized clinical trial (RCT) has evaluated MBSR for CLBP [13], and that trial was limited to older adults.

This RCT compared MBSR with CBT and usual care (UC). We hypothesized that adults with CLBP randomized to MBSR would show greater short- and long-term improvement in back pain-related functional limitations, back pain bothersomeness, and other outcomes, as compared with those randomized to UC. We also hypothesized that MBSR would be superior to CBT because it includes yoga, which has been found effective for CLBP [14].

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

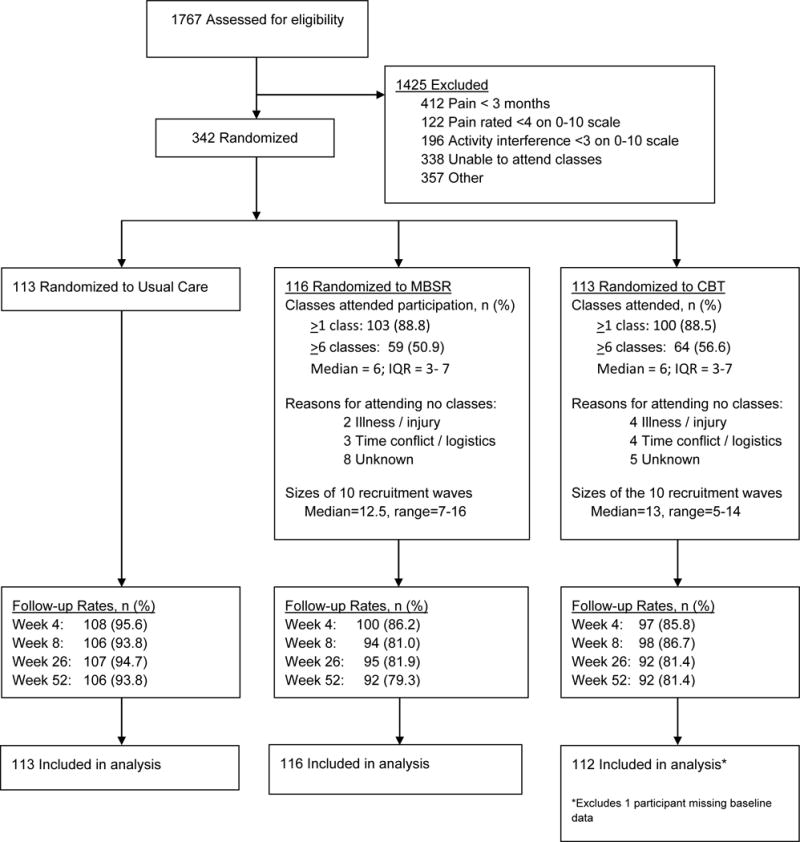

We previously published the Mind-Body Approaches to Pain (MAP) trial protocol [15]. The primary source of participants was Group Health (GH), a large integrated healthcare system in Washington State. Letters describing the trial and inviting participation were mailed to GH members who met the electronic medical record (EMR) inclusion/exclusion criteria, and to random samples of residents in communities served by GH. Individuals who responded to the invitations were screened and enrolled by telephone (Figure 1). Potential participants were told that they would be randomized to one of “two different widely-used pain self-management programs that have been found helpful for reducing pain and making it easier to carry out daily activities” or to continued usual care plus $50. Those assigned to MBSR or CBT were not informed of their treatment allocation until they attended the first session. We recruited participants from 6 cities in 10 separate waves.

Figure 1.

Flow of Participants through Trial Comparing Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction with Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Usual Care for Chronic Low Back Pain.

We recruited individuals 20 to 70 years of age with non-specific low back pain persisting at least 3 months. Persons with back pain associated with a specific diagnosis (e.g., spinal stenosis), with compensation or litigation issues, who would have difficulty participating (e.g., unable to speak English, unable to attend classes at the scheduled time and location), or who rated pain bothersomeness <4 and/or pain interference with activities <3 on 0–10 scales were excluded. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were assessed using EMR data for the previous year (for GH enrollees) and screening interviews. Participants were enrolled between September 2012 and April 2014. Due to slow enrollment, after 99 participants were enrolled, we stopped excluding persons 64–70 years old, GH members without recent visits for back pain, and patients with sciatica. The trial protocol was approved by the GH Human Subjects Review Committee. All participants gave informed consent.

Randomization

Immediately after providing consent and completing the baseline assessment, participants were randomized in equal proportions to MBSR, CBT, or UC. Randomization was stratified by the baseline score (≤12 versus ≥13, 0–23 scale) of one of the primary outcome measures, the modified Roland Disability Questionnaire (RDQ) [16]. Participants were randomized within these strata in blocks of 3, 6, or 9. The stratified randomization sequence was generated by the study biostatistician using R statistical software [17], and the sequence was stored in the study recruitment database and concealed from study staff until randomization.

Interventions

All participants received any medical care they would normally receive. Those randomized to UC received $50 but no MBSR training or CBT as part of the study and were free to seek whatever treatment, if any, they desired.

The interventions were comparable in format (group), duration (2 hours/week for 8 weeks, although the MBSR program also included an optional 6-hour retreat), frequency (weekly), and number of participants per group [See reference 15 for intervention details]. Each intervention was delivered according to a manualized protocol in which all instructors were trained. Participants in both interventions were given workbooks, audio CDs, and instructions for home practice (e.g., meditation, body scan, and yoga in MBSR; relaxation and imagery in CBT). MBSR was delivered by 8 instructors with 5 to 29 years of MBSR experience. Six of the instructors had received training from the Center for Mindfulness at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. CBT was delivered by 4 licensed Ph.D.-level psychologists experienced in group and individual CBT for chronic pain. Checklists of treatment protocol components were completed by a research assistant at each session and reviewed weekly by a study investigator to ensure all treatment components were delivered. In addition, sessions were audio-recorded and a study investigator monitored instructors’ adherence to the protocol in person or via audio-recording for at least one session per group.

MBSR was modelled closely after the original MBSR program [9], with adaptation of the 2009 MBSR instructor’s manual [18] by a senior MBSR instructor. The MBSR program does not focus specifically on a particular condition such as pain. All classes included didactic content and mindfulness practice (body scan, yoga, meditation [attention to thoughts, emotions, and sensations in the present moment without trying to change them, sitting meditation with awareness of breathing, walking meditation]). The CBT protocol included CBT techniques most commonly applied and studied for CLBP [8, 19–22]. The intervention included (1) education about chronic pain, relationships between thoughts and emotional and physical reactions, sleep hygiene, relapse prevention, and maintenance of gains; and (2) instruction and practice in changing dysfunctional thoughts, setting and working towards behavioral goals, relaxation skills (abdominal breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery), activity pacing, and pain coping strategies. Between-session activities included reading chapters of The Pain Survival Guide [21]. Mindfulness, meditation, and yoga techniques were proscribed in CBT; methods to challenge dysfunctional thoughts were proscribed in MBSR.

Follow-up

Trained interviewers masked to treatment group collected data by telephone at baseline (before randomization) and 4 (mid-treatment), 8 (post-treatment), 26 (primary endpoint), and 52 weeks post-randomization. Participants were compensated $20 for each interview.

Measures

Sociodemographic and back pain information was obtained at baseline (Table 1). All primary outcome measures were administered at each time-point; secondary outcomes were assessed at all time-points except 4 weeks.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants by Treatment Groupa

| All (n=341) |

UC (n=113) |

MBSR (n=116) |

CBT (n=112) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 49.3 (12.3) | 48.9 (12.5) | 50.0 (11.9) | 49.1 (12.6) |

| Female | 224 (65.7) | 87 (77.0) | 71 (61.2) | 66 (58.9) |

| Education | ||||

| High school or less | 26 (7.6) | 5 (4.4) | 14 (12.1) | 7 (6.3) |

| Some college or vocational school | 114 (33.4) | 37 (32.7) | 41 (35.3) | 36 (32.1) |

| College graduate | 201 (58.9) | 71 (62.8) | 61 (52.6) | 69 (61.6) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 278 (82.5) | 88 (80.0) | 97 (84.4) | 93 (83.0) |

| Asian | 13 (3.9) | 3 (2.7) | 4 (3.5) | 6 (5.4) |

| African-American | 11 (3.3) | 3 (2.7) | 4 (3.5) | 4 (3.6) |

| Other | 35 (10.4) | 16 (14.6) | 10 (8.7) | 9 (8.0) |

| Hispanic | 23 (6.8) | 8 (7.1) | 5 (4.3) | 10 (8.9) |

| Married or living as married | 249 (73.0) | 79 (69.9) | 85 (73.3) | 85 (75.9) |

| Annual family income > $55,000 USD | 206 (62.6) | 72 (66.1) | 66 (58.4) | 68 (63.6) |

| Employed | 263 (77.1) | 89 (78.8) | 87 (75.0) | 87 (77.7) |

| Back pain history and expectations | ||||

| At least one year since one week without LBP | 269 (78.9) | 86 (76.1) | 93 (80.2) | 90 (80.4) |

| Have had spinal injection for LBP | 8 (2.7) | 3 (3.1) | 3 (3.0) | 2 (2.0) |

| “A lot of pain” currently in body site other than back | 100 (29.3) | 35 (31.0) | 34 (29.3) | 31 (27.7) |

| Days of back pain in last 180 days, median (25th–75th percentile) | 160 (100–180) | 160 (100–180) | 170 (115–180) | 160 (100–180) |

| Expect LBP to be much better or gone in 1 year | 101 (29.8) | 36 (31.9) | 34 (29.6) | 31 (27.9) |

| Expectation LBP self-management program will be helpful (0–10), mean (SD) | 7.5 (1.9) | 7.8 (1.8) | 7.6 (2.0) | 7.2 (1.8) |

| Primary Outcomes | ||||

| RDQ (modified) (0–23; higher scores indicate worse function), mean (SD) | 11.4 (4.8) | 10.9 (4.8) | 11.8 (4.7) | 11.5 (5.0) |

| Pain bothersomeness rating (0–10; higher scores indicate greater pain), mean (SD) | 6.0 (1.6) | 6.0 (1.6) | 6.1 (1.6) | 6.0 (1.5) |

| Secondary Outcomes | ||||

| Characteristic pain intensity (0–10; higher scores indicate greater pain), mean (SD) | 5.9 (1.3) | 5.8 (1.3) | 6.0 (1.3) | 5.8 (1.2) |

| Depression (PHQ-8) (0–24; higher scores indicate more depression), mean (SD) | 5.6 (4.1) | 5.3 (3.8) | 5.7 (4.0) | 5.7 (4.4) |

| Anxiety (GAD-2) (0–6; higher scores indicate more anxiety) | ||||

| mean (SD) | 1.4 (1.5) | 1.5 (1.3) | 1.4 (1.5) | 1.4 (1.5) |

| median (25th–75th percentile) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) |

| Medication use for LBP in past week | ||||

| Any medication | 252 (73.9) | 82 (72.6) | 85 (73.3) | 85 (75.9) |

| Opioids | 38 (11.1) | 12 (10.6) | 14 (12.1) | 12 (10.7) |

| Back-specific exercise, at least 3 days in past week | 137 (40.2) | 44 (38.9) | 48 (41.4) | 45 (40.2) |

| General exercise, at least 3 days in past week | 167 (49.0) | 53 (46.9) | 57 (49.1) | 57 (50.9) |

| SF-12 Physical Component Score (0–100 scale; higher scores indicate higher function), mean (SD) | 39.1 (7.9) | 39.7 (7.6) | 38.2 (7.5) | 39.4 (8.6) |

| SF-12 Mental Component Score (0–100 scale; higher scores indicate higher function), mean (SD) | 39.9 (7.9) | 39.8 (7.4) | 40.6 (8.1) | 39.4 (8.2) |

Abbreviations: UC, usual care; MBSR, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction; CBT, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy; y, years; SD, standard deviation; LBP, low back pain; PHQ-8, Patient Health Questionnaire-8; GAD-2, Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2; SF-12, 12-item Short-Form Health Survey; USD, United States dollars

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Co–primary Outcomes

Back pain-related functional limitation was assessed by the RDQ [16], modified to 23 (versus the original 24) items and to ask about the past week rather than today only. Higher scores (range 0–23) indicate greater functional limitation. The original RDQ has demonstrated reliability, validity, and sensitivity to clinical change [23]. Back pain bothersomeness in the past week was measured by a 0–10 scale (0 = “not at all bothersome,” 10 = “extremely bothersome”). Our primary analyses examined the percentages of participants with clinically meaningful improvement (≥30% improvement from baseline) [24] on each measure. Secondary analyses compared the adjusted mean change from baseline between groups.

Secondary Outcomes

Depressive symptoms were assessed by the Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8; range, 0–24; higher scores indicate greater severity) [25]. Anxiety was measured using the 2-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-2; range, 0–6; higher scores indicate greater severity) [26]. Characteristic pain intensity was assessed as the mean of three 0–10 ratings (current back pain and worst and average back pain in the previous month; range, 0–10; higher scores indicate greater intensity) from the Graded Chronic Pain Scale [27]. The Patient Global Impression of Change scale [28] asked participants to rate their improvement in pain on a 7-point scale (“completely gone, much better, somewhat better, a little better, about the same, a little worse, and much worse”). Physical and mental general health status were assessed with the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) (0–100 scale; lower scores indicate poorer health status) [29]. Participants were also asked about their use of medications and exercise for back pain during the previous week.

Adverse Experiences

Adverse experiences were identified during intervention sessions and by follow-up interview questions about significant discomfort, pain, or harm caused by the intervention.

Sample Size

A sample size of 264 participants (88 in each group) was chosen to provide adequate power to detect meaningful differences between MBSR and CBT and UC at 26 weeks. Sample size calculations were based on the outcome of clinically meaningful improvement (≥30% from baseline) on the RDQ [24]. Estimates of clinically meaningful improvement in the intervention and UC groups were based on unpublished analyses of data from our previous trial of massage for CLBP in a similar population [30]. This sample size provided adequate power for both co-primary outcomes. The planned sample size provided 90% power to detect a 25% difference between MBSR and UC in the proportion with meaningful improvement on the RDQ, and ≥80% power to detect a 20% difference between MBSR and CBT, assuming 30% of UC participants and 55% of CBT participants showed meaningful improvement. For meaningful improvement in pain bothersomeness, the planned sample size provided ≥80% power to detect a 21.8% difference between MBSR and UC, and a 16.7% difference between MBSR and CBT, assuming 47.5% in UC and 69.3% in CBT showed meaningful improvement.

Allowing for an 11% loss to follow-up, we planned to recruit 297 participants (99 per group). Because observed follow-up rates were lower than expected, an additional wave was recruited. A total of 342 participants were randomized to achieve a target sample size of 264 with complete outcome data at 26 weeks.

Statistical Analysis

Following the pre-specified analysis plan [15], differences among the three groups on each primary outcome were assessed by fitting a regression model that included outcome measures from all four time-points after baseline (4, 8, 26, and 52 weeks). A separate model was fit for each co-primary outcome (RDQ and bothersomeness). Indicators for time-point, randomization group, and the interactions between these variables were included in each model to estimate intervention effects at each time-point. Models were fit using generalized estimating equations (GEE) [31], which accounted for possible correlation within individuals. For binary primary outcomes, we used a modified Poisson regression model with a log link and robust sandwich variance estimator [32] to estimate relative risks. For continuous measures, we used linear regression models to estimate mean change from baseline. Models adjusted for age, sex, education, pain duration (<1 year versus ≥1 year since experiencing a week without back pain), and the baseline score on the outcome measure. Evaluation of secondary outcomes followed a similar analytic approach, although models did not include 4-week scores because secondary outcomes were not assessed at 4 weeks.

We evaluated the statistical significance of intervention effects at each time-point separately. We decided a priori to consider MBSR successful only if group differences were significant at the 26-week primary endpoint. To protect against multiple comparisons, we used the Fisher protected least-significant difference approach [33], which requires that pairwise treatment comparisons are made only if the overall omnibus test is statistically significant.

Because our observed follow-up rates differed across intervention groups and were lower than anticipated (Figure 1), we used an imputation method for non-ignorable nonresponse as our primary analysis to account for possible non-response bias. The imputation method used a pattern mixture model framework using a 2-step GEE approach [34]. The first step estimated the GEE model previously outlined with observed outcome data adjusting for covariates, but further adjusting for patterns of non-response. We included the following missing pattern indicator variables: missing one outcome, missing one outcome and assigned CBT, missing one outcome and assigned MBSR, and missing ≥2 outcomes (no further interaction with group was included because very few UC participants missed ≥2 follow-up time-points). The second step estimated the GEE model previously outlined, but included imputed outcomes from step 1 for those with missing follow-up times. We adjusted the variance estimates to account for using imputed outcome measures for unobserved outcomes.

All analyses followed an intention-to-treat approach. Participants were included in the analysis by randomization assignment, regardless of level of intervention participation. All tests and confidence intervals were 2-sided and statistical significance was defined as a P-value ≤ 0.05. All analyses were performed using the statistical package R version 3.0.2 [17].

RESULTS

Figure 1 depicts participant flow through the study. Among 1,767 individuals expressing interest in study participation and screened for eligibility, 342 were enrolled and randomized. The main reasons for exclusion were inability to attend treatment sessions, pain lasting <3 months, and minimal pain bothersomeness or interference with activities. All but 7 participants were recruited from GH. Almost 90% of participants randomized to MBSR and CBT attended at least 1 session, but only 51% in MBSR and 57% in CBT attended at least 6 sessions. Only 26% of those randomized to MBSR attended the 6-hour retreat. Overall follow-up response rates ranged from 89.2% at 4 weeks to 84.8% at 52 weeks, and were higher in the UC group.

At baseline, treatment groups were similar in sociodemographic and pain characteristics except for more women in UC and fewer college graduates in MBSR (Table 1). Over 75% reported at least one year since a week without back pain and most reported pain on at least 160 of the previous 180 days. The mean RDQ score (11.4) and pain bothersomeness rating (6.0) indicated moderate levels of severity. Eleven percent reported using opioids for their pain in the past week. Seventeen percent had at least moderate levels of depression (PHQ-8 scores ≥10) and 18% had at least moderate levels of anxiety (GAD-2 scores ≥3).

Co-Primary Outcomes

At the 26-week primary endpoint, the groups differed significantly (P = 0.04) in percent with clinically meaningful improvement on the RDQ (MBSR 61%, UC 44%, CBT 58%; Table 2a). Participants randomized to MBSR were more likely than those randomized to UC to show meaningful improvement on the RDQ (RR = 1.37; 95% CI, 1.06–1.77), but did not differ significantly from those randomized to CBT. The overall difference among groups in clinically meaningful improvement in pain bothersomeness at 26 weeks was also statistically significant (MBSR 44%, UC 27%, CBT 45%; P = 0.01). Participants randomized to MBSR were more likely to show meaningful improvement when compared with UC (RR = 1.64; 95% CI, 1.15–2.34), but not when compared with CBT (RR = 1.03; 95% CI, 0.78–1.36). The significant differences between MBSR and UC, and non-significant differences between MBSR and CBT, in percent with meaningful function and pain improvement persisted at 52 weeks, with relative risks similar to those at 26 weeks (Table 2a). CBT was superior to UC for both primary outcomes at 26, but not 52, weeks. Treatment effects were not apparent before end of treatment (8 weeks). Generally similar results were found when the primary outcomes were analyzed as continuous variables, although more differences were statistically significant at 8 weeks and the CBT group improved more than the UC group at 52 weeks (Table 2b).

Table 2a.

Co-Primary Outcomes: Percentage of Participants with Clinically Meaningful Improvement in Chronic Low Back Pain by Treatment Group and Relative Risks Comparing Treatment Groups (Adjusted Imputed Analyses)a,b

| Percentage (95% CI)

|

Omnibus P-value‡ | Relative Risks (95% CI)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UC | MBSR | CBT | MBSR-UC | CBT-MBSR | CBT-UC | ||

|

|

|||||||

| Roland Disability Questionnaire (RDQ) | |||||||

| 4 weeks | 27.3 (20.3, 36.6) | 34.5 (26.8, 44.3) | 24.7 (18.1, 33.8) | 0.23 | 1.26 (0.86, 1.86) | 0.72 (0.48, 1.07) | 0.91 (0.59, 1.39) |

| 8 weeks | 35.4 (27.6, 45.2) | 47.4 (38.9, 57.6) | 51.9 (43.6, 61.7) | 0.04 | 1.34 (0.98, 1.84) | 1.10 (0.84, 1.42) | 1.47 (1.09, 1.98) |

| 26 weeks | 44.1 (35.9, 54.2) | 60.5 (52.0, 70.3) | 57.7 (49.2, 67.6) | 0.04 | 1.37 (1.06, 1.77) | 0.95 (0.77, 1.18) | 1.31 (1.01, 1.69) |

| 52 weeks | 48.6 (40.3, 58.6) | 68.6 (60.3, 78.1) | 58.8 (50.6, 68.4) | 0.01 | 1.41 (1.13, 1.77) | 0.86 (0.70, 1.04) | 1.21 (0.95, 1.54) |

| Pain Bothersomeness | |||||||

| 4 weeks | 20.6 (14.6, 28.9) | 19.1 (13.3, 27.4) | 21.7 (15.3, 30.6) | 0.88 | 0.93 (0.56, 1.52) | 1.14 (0.69, 1.87) | 1.05 (0.65, 1.71) |

| 8 weeks | 24.7 (18.1, 33.6) | 36.1 (28.3, 46.0) | 33.8 (26.5, 43.2) | 0.15 | 1.46 (0.99, 2.16) | 0.94 (0.67, 1.32) | 1.37 (0.93, 2.02) |

| 26 weeks | 26.6 (19.8, 35.9) | 43.6 (35.6, 53.3) | 44.9 (36.7, 55.1) | 0.01 | 1.64 (1.15, 2.34) | 1.03 (0.78, 1.36) | 1.69 (1.18, 2.41) |

| 52 weeks | 31.0 (23.8, 40.3) | 48.5 (40.3, 58.3) | 39.6 (31.7, 49.5) | 0.02 | 1.56 (1.14, 2.14) | 0.82 (0.62, 1.08) | 1.28 (0.91, 1.79) |

Abbreviations: UC, usual care; MBSR, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction; CBT, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy; CI, confidence interval

Wald P-value. P < 0.05 for bolded pairwise comparisons.

Estimates from GEE 2-step imputed model adjusting for baseline outcome score, sex, age, education, and pain duration (<1 year versus ≥1 year since experiencing a week without back pain). Clinically meaningful improvement was defined as ≥30% improvement from baseline on the measure.

N=341 included in the analysis; one randomized participant who did not complete the baseline survey was excluded. Follow-up rates (sample sizes before imputation) at each time point by randomization group are detailed in Figure 1. In addition, 1 MBSR respondent at 8 weeks, and 1 UC respondent at 26-weeks were missing data for the Pain Bothersomeness outcome.

Table 2b.

Co-Primary Outcomes: Mean (95% CI) Change in Chronic Low Back Pain by Treatment Group and Mean (95% CI) Differences Between Treatment Groups (Adjusted Imputed Analyses)a

| Mean Change from Baseline

|

Omnibus P-value‡ | Between-Group Differences

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UC | MBSR | CBT | MBSR-UC | CBT-MBSR | CBT-UC | ||

|

|

|||||||

| Roland Disability Questionnaire (RDQ) | |||||||

| 4 weeks | −1.28 (−1.91, −0.65) | −1.93 (−2.61, −1.25) | −1.44 (−2.10, −0.78) | 0.37 | −0.65 (−1.59, 0.28) | 0.49 (−0.46, 1.45) | −0.16 (−1.07, 0.76) |

| 8 weeks | −1.83 (−2.59, −1.07) | −3.40 (−4.22, −2.59) | −3.37 (−4.14, −2.60) | 0.005 | −1.57 (−2.70, −0.45) | 0.04 (−1.11, 1.18) | −1.54 (−2.61, −0.46) |

| 26 weeks | −2.96 (−3.79, −2.14) | −4.33 (−5.16, −3.51) | −4.38 (−5.3, −3.47) | 0.03 | −1.37 (−2.55, −0.19) | −0.05 (−1.31, 1.21) | −1.42 (−2.66, −0.18) |

| 52 weeks | −3.43 (−4.33, −2.52) | −5.3 (−6.16, −4.43) | −4.78 (−5.67, −3.89) | 0.01 | −1.87 (−3.14, −0.60) | 0.51 (−0.75, 1.78) | −1.36 (−2.63, −0.08) |

| Pain Bothersomeness | |||||||

| 4 weeks | −0.68 (−0.98, −0.38) | −0.57 (−0.87, −0.27) | −0.79 (−1.13, −0.44) | 0.66 | 0.11 (−0.32, 0.53) | −0.21 (−0.67, 0.25) | −0.11 (−0.56, 0.35) |

| 8 weeks | −0.67 (−1.02, −0.33) | −1.40 (−1.71, −1.10) | −1.28 (−1.62, −0.94) | 0.005 | −0.73 (−1.19, −0.27) | 0.12 (−0.34, 0.58) | −0.61 (−1.09, −0.12) |

| 26 weeks | −0.84 (−1.21, −0.46) | −1.48 (−1.86, −1.11) | −1.56 (−2.02, −1.11) | 0.02 | −0.64 (−1.18, −0.11) | −0.08 (−0.68, 0.51) | −0.73 (−1.32, −0.13) |

| 52 weeks | −1.10 (−1.48, −0.71) | −1.95 (−2.32, −1.59) | −1.76 (−2.14, −1.39) | 0.005 | −0.85 (−1.39, −0.32) | 0.19 (−0.33, 0.71) | −0.67 (−1.20, −0.13) |

Abbreviations: UC, usual care; MBSR, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction; CBT, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy; CI, confidence interval.

Wald P-value. P < 0.05 for bolded pairwise comparisons.

Estimates from GEE 2-step imputed model adjusting for baseline outcome score, sex, age, education, and pain duration (<1 year versus ≥1 year since experiencing a week without back pain).

N=341 included in the analysis; one randomized participant who did not complete the baseline survey was excluded. Follow-up rates (sample sizes before imputation) at each time point by randomization group are detailed in Figure 1. In addition, 1 MBSR respondent at 8 weeks, and 1 UC respondent at 26-weeks were missing data for the Pain Bothersomeness outcome.

Secondary Outcomes

Mental health outcomes (depression, anxiety, SF-12 Mental Component) differed significantly across groups at 8 and 26, but not 52, weeks (Table 3). Among these measures and time-points, participants randomized to MBSR improved more than those randomized to UC only on the depression and SF-12 Mental Component measures at 8 weeks. Participants randomized to CBT improved more than those randomized to MBSR on depression at 8 weeks and anxiety at 26 weeks, and more than the UC group at 8 and 26 weeks on all three measures.

Table 3.

| UC | MBSR | CBT | Omnibus P-value‡ | MBSR-UC | CBT-MBSR | CBT-UC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Mean Change from Baseline Outcomes | Mean Change Estimates (95% CI) | Between-Group Mean Differences | |||||

| Depression (PHQ-8) | |||||||

| 8 weeks | −0.12 (−0.74, 0.50) | −1.60 (−2.15, −1.05) | −2.29 (−2.66, −1.92) | <0.001 | −1.48 (−2.31, −0.64) | −0.69 (−1.35, −0.02) | −2.17 (−2.89, −1.45) |

| 26 weeks | −0.64 (−1.23, −0.06) | −1.32 (−1.81, −0.83) | −1.80 (−2.35, −1.26) | 0.02 | −0.68 (−1.45, 0.09) | −0.48 (−1.21, 0.26) | −1.16 (−1.95, −0.37) |

| 52 weeks | −0.88 (−1.50, −0.27) | −1.51 (−2.09, −0.92) | −1.72 (−2.28, −1.16) | 0.13 | −0.62 (−1.48, 0.23) | −0.21 (−1.03, 0.61) | −0.83 (−1.67, 0.00) |

| Anxiety (GAD−2) | |||||||

| 8 weeks | −0.09 (−0.32, 0.13) | −0.33 (−0.56, −0.10) | −0.51 (−0.69, −0.33) | 0.02 | −0.24 (−0.56, 0.09) | −0.18 (−0.47, 0.11) | −0.41 (−0.70, −0.13) |

| 26 weeks | 0.02 (−0.24, 0.28) | 0.00 (−0.28, 0.28) | −0.49 (−0.72, −0.25) | 0.005 | −0.02 (−0.41, 0.37) | −0.49 (−0.85, −0.12) | −0.51 (−0.86, −0.16) |

| 52 weeks | −0.14 (−0.40, 0.12) | −0.15 (−0.40, 0.10) | −0.39 (−0.59, −0.18) | 0.23 | 0.00 (−0.37, 0.36) | −0.24 (−0.56, 0.08) | −0.24 (−0.58, 0.09) |

| Characteristic pain intensity | |||||||

| 8 weeks | −0.37 (−0.62, −0.12) | −1.00 (−1.28, −0.73) | −0.86 (−1.12, −0.59) | 0.002 | −0.63 (−1.01, −0.26) | 0.15 (−0.24, 0.53) | −0.49 (−0.84, −0.13) |

| 26 weeks | −0.65 (−0.95, −0.35) | −1.10 (−1.42, −0.77) | −1.15 (−1.44, −0.86) | 0.04 | −0.45 (−0.89, −0.01) | −0.05 (−0.50, 0.39) | −0.50 (−0.92, −0.09) |

| 52 weeks | −0.79 (−1.10, −0.48) | −1.42 (−1.72, −1.12) | −1.40 (−1.74, −1.05) | 0.007 | −0.63 (−1.06, −0.19) | 0.02 (−0.44, 0.48) | −0.61 (−1.07, −0.14) |

| SF-12 Physical Component Score | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 2.21 (1.12, 3.30) | 3.69 (2.61, 4.77) | 3.24 (2.21, 4.27) | 0.16 | 1.48 (−0.06, 3.02) | −0.45 (−1.95, 1.05) | 1.03 (−0.48, 2.54) |

| 26 weeks | 3.27 (2.09, 4.44) | 3.58 (2.15, 5.01) | 3.78 (2.56, 5.00) | 0.84 | 0.31 (−1.53, 2.16) | 0.20 (−1.69, 2.10) | 0.52 (−1.19, 2.22) |

| 52 weeks | 2.93 (1.70, 4.16) | 3.87 (2.55, 5.19) | 3.79 (2.55, 5.03) | 0.50 | 0.94 (−0.86, 2.74) | −0.08 (−1.91, 1.75) | 0.86 (−0.87, 2.60) |

| SF-12 Mental Component Score | |||||||

| 8 weeks | −0.65 (−1.86, 0.55) | 1.68 (0.57, 2.79) | 1.77 (0.82, 2.72) | 0.004 | 2.33 (0.68, 3.99) | 0.09 (−1.37, 1.54) | 2.42 (0.87, 3.97) |

| 26 weeks | −1.11 (−2.39, 0.17) | 0.45 (−0.85, 1.76) | 2.13 (0.86, 3.40) | 0.002 | 1.57 (−0.27, 3.40) | 1.68 (−0.12, 3.47) | 3.24 (1.44, 5.04) |

| 52 weeks | 0.75 (−0.58, 2.08) | 2.01 (0.74, 3.28) | 1.81 (0.59, 3.03) | 0.36 | 1.26 (−0.60, 3.11) | −0.19 (−1.95, 1.56) | 1.06 (−0.75, 2.88) |

|

| |||||||

| Binary Outcomes | Percentage (95% CI) | Relative Risks (95% CI) | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Global Improvement (pain much better or completely gone) | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 10.8 (6.5, 17.8) | 15.6 (10.4, 23.5) | 21.9 (15.9, 30.3) | 0.06 | 1.45 (0.76, 2.78) | 1.40 (0.84, 2.35) | 2.04 (1.12, 3.69) |

| 26 weeks | 13.6 (8.6, 21.5) | 26.2 (19.3, 35.7) | 30.1 (22.7, 39.9) | 0.01 | 1.93 (1.12, 3.32) | 1.15 (0.76, 1.73) | 2.21 (1.30, 3.76) |

| 52 weeks | 18.0 (12.1, 26.7) | 30.0 (22.6, 39.8) | 31.9 (24.5, 41.6) | 0.048 | 1.67 (1.03, 2.71) | 1.06 (0.73, 1.55) | 1.78 (1.11, 2.85) |

| Used medications for LBP in past week | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 63.3 (55.6, 72.1) | 53.4 (45.9, 62.2) | 53.2 (46.1, 61.4) | 0.09 | 0.84 (0.70, 1.02) | 1.00 (0.82, 1.21) | 0.84 (0.70, 1.00) |

| 26 weeks | 54.2 (46.2, 63.6) | 43.4 (35.9, 52.6) | 50.9 (43.4, 59.7) | 0.18 | 0.80 (0.63, 1.02) | 1.17 (0.92, 1.49) | 0.94 (0.76, 1.16) |

| 52 weeks | 52.9 (45.1, 62.0) | 46.8 (39.2, 55.9) | 42.1 (34.9, 50.9) | 0.17 | 0.89 (0.70, 1.11) | 0.90 (0.70, 1.16) | 0.80 (0.63, 1.01) |

| At least 3 days of back exercise in past week | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 42.3 (34.5, 51.8) | 66.3 (58.2, 75.6) | 59.1 (51.1, 68.4) | 0.001 | 1.57 (1.23, 2.00) | 0.89 (0.74, 1.08) | 1.40 (1.09, 1.79) |

| 26 weeks | 36.4 (28.4, 46.7) | 42.0 (34.3, 51.5) | 41.8 (34.1, 51.3) | 0.62 | 1.15 (0.84, 1.59) | 0.99 (0.75, 1.32) | 1.15 (0.84, 1.58) |

| 52 weeks | 35.0 (27.5, 44.5) | 51.4 (42.9, 61.5) | 41.0 (33.0, 50.9) | 0.04 | 1.47 (1.09, 1.98) | 0.80 (0.60, 1.05) | 1.17 (0.85, 1.61) |

| At least 3 days of general exercise in past week | |||||||

| 8 weeks | 54.0 (45.9, 63.4) | 64.4 (57.2, 72.5) | 62.5 (55.1, 70.9) | 0.20 | 1.19 (0.98, 1.45) | 0.97 (0.82, 1.15) | 1.16 (0.95, 1.41) |

| 26 weeks | 60.1 (52.0, 69.5) | 51.3 (43.7, 60.2) | 50.7 (42.7, 60.1) | 0.21 | 0.85 (0.69, 1.05) | 0.99 (0.79, 1.24) | 0.84 (0.68, 1.05) |

| 52 weeks | 56.2 (48.0, 65.7) | 62.6 (55.1, 71.1) | 52.4 (44.7, 61.5) | 0.19 | 1.11 (0.91, 1.36) | 0.84 (0.69, 1.02) | 0.93 (0.75, 1.16) |

Abbreviations: UC, usual care; MBSR, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction; CBT, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy; LBP = low back pain; CI = confidence interval; PHQ-8, Patient Health Questionnaire-8; GAD-2, Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2

Wald P-value. P<0.05 for bolded pairwise comparisons.

Estimates from GEE 2-step imputed model adjusting for baseline outcome score, sex, age, education, and pain duration (<1 year versus ≥1 year since experiencing a week without back pain).

N=341 included in the analysis; one randomized participant who did not complete the baseline survey was excluded. Follow-up rates (sample sizes before imputation) at each time point by randomization group are detailed in Figure 1. In addition, the following number of participants had missing data for secondary outcomes:

Depression, anxiety, pain intensity, global improvement, medication use, and exercise: UC (n=2 at 8-weeks, n=5 at 26-weeks, n=6 at 52-weeks), MBSR (n=3, n=6, n=2 respectively), CBT (n=3, n=5, n=7 respectively);

SF-12 physical and SF-12 mental: UC (n=4, n=5, n=8 respectively), MBSR (n=6, n=8, n=6 respectively), CBT (n=3, n=6, n=7 respectively)

The groups differed significantly in improvement in characteristic pain intensity at all three time-points, with greater improvement in MBSR and CBT than in UC and no significant difference between MBSR and CBT. No overall differences in treatment effects were observed for the SF-12 Physical Component score or self-reported use of medications for back pain. Groups differed at 26 and 52 weeks in self-reported global improvement, with both the MBSR and CBT groups reporting greater improvement than the UC group, but not differing significantly from each other.

Adverse experiences

Thirty of the 103 (29%) participants attending at least 1 MBSR session reported an adverse experience (mostly temporarily increased pain with yoga). Ten of the 100 (10%) participants who attended at least one CBT session reported an adverse experience (mostly temporarily increased pain with progressive muscle relaxation). No serious adverse events were reported.

DISCUSSION

Among adults with CLBP, both MBSR and CBT resulted in greater improvement in back pain and functional limitations at 26 and 52 weeks, as compared with UC. There were no meaningful differences in outcomes between MBSR and CBT. The effects were moderate in size, which has been typical of evidence-based treatments recommended for CLBP [4]. These benefits are remarkable given that only 51% of those randomized to MBSR and 57% of those randomized to CBT attended ≥6 of the 8 sessions.

Our findings are consistent with the conclusions of a 2011 systematic review [35] that “acceptance-based” interventions such as MBSR have beneficial effects on the physical and mental health of patients with chronic pain, comparable to those of CBT. They are only partially consistent with the only other large RCT of MBSR for CLBP [13], which found that MBSR, as compared with a time- and attention-matched health education control group, provided benefits for function at post-treatment (but not at 6-month follow-up) and for average pain at 6-month follow-up (but not post-treatment). Several differences between our trial and theirs (which was limited to adults ≥65 years and had a different comparison condition) could be responsible for differences in findings.

Although our trial lacked a condition controlling for nonspecific effects of instructor attention and group participation, CBT and MBSR have been shown to be more effective than control and active interventions for pain conditions. In addition to the trial of older adults with CLBP [14] that found MBSR to be more effective than a health education control condition, a recent systematic review of CBT for nonspecific low back pain found CBT to be more effective than guideline-based active treatments in improving pain and disability at short- and long-term follow-ups [7]. Further research is needed to identify moderators and mediators of the effects of MBSR on function and pain, evaluate benefits of MBSR beyond one year, and determine its cost-effectiveness. Research is also needed to identify reasons for session non-attendance and ways to increase attendance, and to determine the minimum number of sessions required.

Our finding of increased effectiveness of MBSR at 26–52 weeks relative to post-treatment for both primary outcomes contrasts with findings of our previous studies of acupuncture, massage, and yoga conducted in the same population as the current trial [30, 36, 37]. In those studies, treatment effects decreased between the end of treatment (8 to 12 weeks) and long-term follow-up (26 to 52 weeks). Long-lasting effects of CBT for CLBP have been reported [7, 38, 39]. This suggests that mind-body treatments such as MBSR and CBT may provide patients with long-lasting skills effective for managing pain.

There were more differences between CBT and UC than between MBSR and UC on measures of psychological distress. CBT was superior to MBSR on the depression measure at 8 weeks, but the mean difference between groups was small. Because our sample was not very distressed at baseline, further research is needed to compare MBSR to CBT in a more distressed patient population.

Limitations of this study must be acknowledged. Study participants were enrolled in a single healthcare system and generally highly educated. The generalizability of findings to other settings and populations is unknown. About 20% of participants randomized to MBSR and CBT were lost to follow-up. We attempted to correct for bias from missing data in our analyses by using imputation methods. Finally, the generalizability of our findings to CBT delivered in an individual rather than group format is unknown; CBT may be more effective when delivered individually [40]. Study strengths include a large sample with adequate statistical power to detect clinically meaningful effects, close matching of the MBSR and CBT interventions in format, and long-term follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS

Among adults with chronic low back pain, treatment with MBSR and CBT, compared with UC, resulted in greater improvement in back pain and functional limitations at 26 weeks, with no significant differences in outcomes between MBSR and CBT. These findings suggest that MBSR may be an effective treatment option for patients with chronic low back pain.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Complementary & Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AT006226. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Role of sponsor: The study funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Trial Registration: clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01467843

Author contributions: Dr. Cook had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Cherkin, Sherman, Balderson, Cook, Turner

Acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data: Cherkin, Sherman, Balderson, Cook, Anderson, Hawkes, Hansen, Turner

Drafting of the manuscript: Cherkin, Sherman, Balderson, Anderson, Turner

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Cherkin, Sherman, Balderson, Cook, Anderson, Hawkes, Hansen, Turner

Statistical analysis: Cook, Anderson

Obtained funding: Cherkin

Administrative, technical, or material support: Cherkin, Sherman, Balderson, Cook, Anderson, Hawkes, Hansen, Turner

Study supervision: Cherkin, Sherman, Balderson, Hawkes, Hansen

Conflicts of interest and financial disclosures: All authors report no conflicts of interest or disclosures.

Important disclaimers: None

Previous presentation: Dr. Cherkin presented a brief summary of the preliminary results at the “Mindfulness & Compassion: The Art and Science of Contemplative Practice” conference on June 4, 2015 at San Francisco State University.

Additional Contributions: We acknowledge the support provided by the following individuals: Kristin Delaney, MPH, Group Health Research Institute Programmer Analyst, for extracting information from data systems, assisting with the design and development of data tracking systems, and interim analyses (received salary support from the NCCIH grant); Zoe Bermet, LMP, John Ewing, BFA, Kevin Filocamo, MA, Melissa Parson, MFA, Margie Wilcox, Group Health Research Institute Research Specialists, for participant recruitment, tracking, staffing classes, data entry, and interviews (received salary support from the NCCIH grant); Beth Kirlin, BA, Group Health Research Institute Project Manager, for implementation and oversight of project activities (received salary support from the NCCIH grant); Katherine Bradley, MD, Group Health Research Institute Medical Advisor, for adverse events review and oversight; Robert Wellman, MS, Group Health Research Institute Biostatistician, for input on research design and implementation (received salary support from the NCCIH grant); Michelle Chapdelaine, BA, Natalia Charamand, BA, Group Health Research Institute Research Support Specialists, for administrative support (received salary support from the NCCIH grant); MBSR Instructors: Diane Hetrick, PT, Rebecca Bohn, MA, Tracy Skaer, PharmD, Vivian Folsom, MSS, LICSW, Carolyn McManus, PT, MS, MA, Timothy Burnett, Cheryl Cebula, MSW, ACSW, Lorrie Jones, BSN, for teaching the MBSR arm of the intervention (instructors were paid on a consultancy basis for classes taught); CBT Instructors: Brenda Stoelb, PhD, Sonya Wood, PhD, Geoffrey Soleck, PhD, Leslie Aaron, PhD, for teaching the CBT arm of the intervention (instructors were paid on a consultancy basis for classes taught); Richard Deyo, MD, MPH, Medical Consultant, for providing guidance on clinical issues (paid on a consultancy basis).

Contributor Information

Daniel C. Cherkin, Group Health Research Institute; Departments of Health Services and Family Medicine, University of Washington.

Karen J. Sherman, Group Health Research Institute; Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington.

Benjamin H. Balderson, Group Health Research Institute, University of Washington.

Andrea J. Cook, Group Health Research Institute; Department of Biostatistics, University of Washington.

Melissa L. Anderson, Group Health Research Institute, University of Washington.

Rene J. Hawkes, Group Health Research Institute, University of Washington.

Kelly E. Hansen, Group Health Research Institute, University of Washington.

Judith A. Turner, Departments of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Washington.

References

- 1.US Burden of Disease Collaborators. The State of US Health, 1990–2010: Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors. JAMA. 2013;310(6):591–606. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.138051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin BI, Deyo RA, Mirza SK, et al. Expenditures and health status among adults with back and neck problems. JAMA. 2008;299:656–664. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.6.656. A published erratum appears in JAMA 2008;299:2630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mafi JN, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Landon BE. Worsening trends in the management and treatment of back Pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(17):1573–1581. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.8992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al. Clinical Efficacy Assessment Subcommittee of the American College of Physicians; American College of Physicians; American Pain Society Low Back Pain Guidelines Panel Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:478–491. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams AC, Eccleston C, Morley S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD007407. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007407.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henschke N, Ostelo RW, van Tulder MW, et al. Behavioural treatment for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;7:CD002014. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002014.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richmond H, Hall AM, Copsey B, Hansen Z, Williamson E, Hoxey-Thomas N, Cooper Z, Lamb SE. The effectiveness of cognitive behavioural treatment for non-specific low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0134192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehde DM, Dillworth TM, Turner JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for individuals with chronic pain: Efficacy, innovations, and directions for research. Am Psychol. 2014;69:153–166. doi: 10.1037/a0035747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kabat-Zinn J. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness. New York: Random House; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reinier K, Tibi L, Lipsitz JD. Do mindfulness-based interventions reduce pain intensity? A critical review of the literature. Pain Med. 2013;14:230–242. doi: 10.1111/pme.12006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fjorback LO, Arendt M, Ornbøl E, Fink P, Walach H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;124:102–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cramer H, Haller H, Lauche R, Dobos G. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for low back pain: a systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:162. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morone NE, Greco CM, Moore CG, Rollman BL, Lane B, Morrow LA, Glynn NW, Weiner DK. A mind-body program for older adults with chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.8033. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cramer H, Lauche R, Haller H, Dobos G. A systematic review and meta-analysis of yoga for low back pain. Clin J Pain. 2013;29(5):450–60. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31825e1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Balderson BH, et al. Comparison of complementary and alternative medicine with conventional mind-body therapies for chronic back pain: protocol for the Mind-body Approaches to Pain (MAP) randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:211. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patrick DL, Deyo RA, Atlas SJ, Singer DE, Chapin A, Keller RB. Assessing health-related quality of life in patients with sciatica. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20:1899–1908. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199509000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013. http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blacker M, Meleo-Meyer F, Kabat-Zinn J, Santorelli SF. Stress Reduction Clinic Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) Curriculum Guide. Worcester, MA: Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society, Division of Preventive and Behavioral Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turner JA, Romano JM. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain. In: Loeser JD, Butler SH, Chapman CR, Turk DC, editors. Bonica’s Management of Pain. 3rd. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. pp. 1751–1758. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lamb SE, Hansen Z, Lall R, et al. Back Skills Training Trial investigators: Group cognitive behavioural treatment for low-back pain in primary care: a randomised controlled trial and cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:916–923. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turk DC, Winter F. The Pain Survival Guide: How to Reclaim Your Life. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otis JD. Managing Chronic Pain: A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Approach (Therapist Guide) New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roland M, Fairbank J. The Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:3115–3124. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00006. A published erratum appears in Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ostelo RW, Deyo RA, Stratford P, et al. Interpreting change scores for pain and functional status in low back pain: towards international consensus regarding minimal important change. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33:90–94. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815e3a10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skapinakis P. The 2-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale had high sensitivity and specificity for detecting GAD in primary care. Evid Based Med. 2007;12:149. doi: 10.1136/ebm.12.5.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Von Korff M. Assessment of Chronic Pain in Epidemiological and Health Services Research. In: Turk DC, Melzack R, editors. Empirical Bases and New Directions in Handbook of Pain Assessment. 3rd. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. pp. 455–473. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guy W, National Institute of Mental Health (US). Psychopharmacology Research Branch. Early Clinical Drug Evaluation Program . ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, National Institute of Mental Health, Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs; 1976. Revised 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Kahn J, et al. A comparison of the effects of 2 types of massage and usual care on chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:1–9. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-155-1-201107050-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levin J, Serlin R, Seaman M. A controlled, powerful multiple-comparison strategy for several situations. Psychol Bull. 1994;115:153–159. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang M, Fitzmaurice GM. A simple imputation method for longitudinal studies with non-ignorable non-responses. Biom J. 2006;48:302–318. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200510188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Veehof MM, Oskam MJ, Schreurs KM, Bohlmeijer ET. Acceptance-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2011;152(3):533–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Avins AL, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing acupuncture, simulated acupuncture, and usual care for chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:858–866. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Wellman RD, et al. A randomized trial comparing yoga, stretching, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(22):2019–26. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lamb SE, Mistry D, Lall R, et al. Back Skills Training Trial Group Group cognitive behavioural interventions for low back pain in primary care: extended follow-up of the Back Skills Training Trial (ISRCTN54717854) Pain. 2012;153(2):494–501. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Von Korff M, Balderson BH, Saunders K, et al. A trial of an activating intervention for chronic back pain in primary care and physical therapy settings. Pain. 2005;113(3):323–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moreno S, Gili M, Magallón R, et al. Effectiveness of group versus individual cognitive-behavioral therapy in patients with abridged somatization disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Psychosom Med. 2013;75(6):600–608. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31829a8904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]