Abstract

Purpose

This study explores transitions in contraceptive use in early sexual life in France and has three objectives: describe predictors of contraceptive use at first sex with first and second partners, describe contraceptive trajectories in these partnerships, and test associations between use at first sex and switching in first partnership on use with second partner.

Methods

Our analyses include 1,823 participants, aged 15-29, of the 2010 French national sexual health survey who reported at least 2 lifetime sexual partners and a subset of 1,593 people who report contraceptive use throughout their first partnership. We use logistic regression and generalized estimating equation models to investigate the three objectives.

Results

Our results reveal a decline in contraceptive use between first and second partner, driven primarily by decreases in condom use, from 87.9% to 79.5% between first and second partner. This is partially offset by an increase in use of effective methods (from 7.8% to 38.1%), particularly by women. Any method use and discontinuation with first partner were predictors of patterns with second partner.

Conclusions

Analysis of early transitions in contraceptive use of adolescents in early sexual life reveals shifts from STI to pregnancy prevention as well as an increase in unprotected sex.

Implication and Contributions

This study reveals changes in preventive behaviors in early sexual life, towards more effective contraceptives and a decline in condom use. Future studies could explore the relationship and gendered contexts in which trade-offs between pregnancy prevention and STI prevention are negotiated.

Background

Over 90% of French adolescents use contraception at first sex.1 In other European countries use ranges from 33% - 91%2 and is approximately 82% in the US.3 Despite this high use at first sex, one in five pregnancies among people aged 18-29 are reported as unintended in France.4 Unintended pregnancy and abortion rates, highest among women in their 20s, have been on the rise since the mid-1990s, peaking in the mid-2000s.4,10 This is mostly driven by use of less effective pregnancy prevention methods, inconsistent use, or gaps in use as young people switch between methods.5–8

The HIV epidemic in the 1980s in France contributed to the uptake of condom use at sexual debut,1,9 replaced by the pill once young people transition into more durable relationships.1 While successful in limiting the spread of HIV and other STIs, the focus on STI prevention has overshadowed the risk of unintended pregnancy. Women preferring to prevent pregnancy would be better off choosing long acting reversible contraceptives,10 while STI prevention – particularly essential early in any relationship – is most effective with condoms. Understanding whether and how young people move from STI focused prevention to more effective pregnancy prevention is essential to identifying points to intervene to prevent gaps or discontinuation.

Many studies focus on preventive behaviors at first sex as this predicts later sexual behaviors.11–13 However, we know little about if/when people switch or discontinue using particular methods. With that gap in the literature in mind, this paper has three objectives. First, we describe the factors associated with different protective strategies at first sex with a new partner (either first or second). Second, we explore individual trajectories in protective behaviors within first partnership and between partners, and discuss the implications of these changes for pregnancy and STI prevention. Third, we explore the predictive effect of contraceptive use with first partner on preventive behaviors with second partner.

Methods

The FECOND study, a national probability survey conducted in France in 2010, addresses sexual and reproductive health in the French population. A sample of 8,645 individuals aged 15 to 49 years was identified using random digit dialing (including landline and cellphones). One individual per phone number was selected for participation. After orally consenting, participants responded to telephone interviews, which lasted an average of 41 minutes. The FECOND study was approved by the French agency CNIL and the Johns Hopkins IRB approved these analyses.

The present analyses include individuals who were under the age of 30 (n=3,424) and who reported ever having heterosexual intercourse (n=2,712) because questions on contraceptive practices were restricted to this subgroup of respondents. We excluded individuals who abandoned the questionnaire before describing their history of contraceptive use (n=51) and four who refused to answer. We also excluded three individuals who reported an age at first intercourse under the age of 10. Thus, our initial study population (“Population 1”) includes 2,657 participants. To explore predictors of use at first sex with first and second partners, we selected respondents who reported at least 2 opposite sex sexual partners (n=2,009). We further excluded individuals who reported they had a one-night stand with either partner (n=174) because they were only asked about condom use and not other contraceptive methods. Finally, we excluded participants who did not answer questions about contraceptive practices with their second partner (n=12). Our analytical sample for the analysis of contraceptive use at first sex with both first and second partners thus included 1,823 individuals (“Population 2”). Finally, in order to explore the transitions in preventive behaviors both within and across partnerships we further restricted the analytical sample to respondents who reported more than one act of intercourse with their first partner (“Population Switch:” n=1,593).

Measures

The FECOND questionnaire covered a range of sexual and reproductive health topics, including current and past contraceptive usage, pregnancy histories, and reproductive healthcare service utilization. People under the age of 30 were asked to describe their first sexual experiences in their first 2 partnerships. Respondents were asked if they had done anything to avoid a pregnancy at first sex and if so, what method was used – including all hormonal contraception methods, intra-uterine devices (IUDs), and condoms. If they reported a non-condom birth control method, they were asked separately if they had also used a condom. They then were asked how long they had used their first method/condom, and whether they had discontinued using any of these methods with their first partner. Those who discontinued were asked about other methods used with this partner and whether there was a gap in use between methods. Additionally, respondents who did not use any method at first intercourse were asked if they had ever started to use a method with their first partner, and if so, what and when (condoms were asked about separately again). Questions about contraceptive and condom use at first intercourse with the second partner were asked similarly. Based on this information, we defined four dichotomous (yes/no) measures to assess preventive practices at first sex with either partner:

- Any form of contraception,

- condom use,

- use of very effective methods (hormonal or IUDs), and

- dual method use.

These measures were chosen to assess protection against STI on the one hand, effective protection against pregnancy on the other, and optimal protection against both STIs and pregnancy. Very effective contraceptives were predominantly composed of oral contraceptive pills.

We adjusted for educational level, country of birth, and religious beliefs. While educational level was recorded at the time of the survey rather than at the time of first sex, we considered it to capture important educational trajectories. However, because such trajectories were not well accounted for among the youngest respondents who are still in school, we defined a category for respondents who were still in high school. We also considered the respondent's father's and mother's education and assessed openness with parents about sexuality by asking respondents to recall the ease of discussing sexuality with their parents at the age of 15. In order to account for period effects, current age is controlled for. Finally, we include age at first, as previous analyses show differences in contraceptive usage at first sex by age at the event.1

Statistical Analysis

The first analysis was cross sectional. We described the demographic characteristics of the study populations (Table 1) and used bivariate statistics to explore factors associated with use of any method, condoms, very effective methods, and dual methods at first sex with either first or second partner (bivariate analyses are not shown). We then used multivariate logistic regression to assess independent factors associated with the four different variables assessing contraceptive/ condom use at first sex with both partners. After specifying the best fitted model for each of these outcomes (using goodness of fit and AIC criteria), we fitted generalized estimated equation regression models to account for non-independence of observations between first and second partner (Table 2). Analyses were stratified by gender (and tested with interactions by sex), in order to uncover potential sex differences in factors informing preventive practices.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of study populations

| Respondents who ever had sexual intercourse (n=2,657) | Respondents who had 2 partners and no 1 night stand (n=1,823) | Respondents who had 2 partners and >1 sexual act with 1st partner (n=1,593) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males N=1124 |

Females N=1535 |

Males N=801 |

Females N=1022 |

Males N=700 |

Females N=893 |

||

| Sex | 50% | 50% | 48.7% | 51.3% | 51.6% | 48.4% | |

| Age | 15 – 19 | 27.2% | 25.8% | 23.5% | 22.4% | 23.3% | 21.4% |

| 20 – 24 | 32.9% | 32.0% | 33.3% | 32.6% | 33.6% | 33.5% | |

| 25 – 29 | 39.9% | 42.2% | 43.2% | 45.0% | 43.2% | 45.0% | |

| Place of birth | France (mainland and overseas) | 92.9% | 90.3% | 92.5% | 91.2% | 94.0% | 92.8% |

| foreign | 7.1% | 9.7% | 7.5% | 8.8% | 6.0% | 7.2% | |

| Education attainment | <high school | 37.2% | 24.8% | 38.0% | 23.9% | 36.0% | 23.3% |

| high school | 16.4% | 14.9% | 17.5% | 16.7% | 18.1% | 16.6% | |

| >High school | 22.7% | 31.9% | 24.2% | 34.4% | 25.3% | 35.0% | |

| Still in school and no college degree | 23.7% | 28.4% | 20.3% | 25.1% | 20.5% | 25.0% | |

| Mother's educ. | no diploma | 20.1% | 19/0% | 19.7% | 16.9% | 17.6% | 16.6% |

| <high school | 30.2% | 33.3% | 32.6% | 34.8% | 32.5% | 34.4% | |

| high school | 17.4% | 17.8% | 17.4% | 18.1% | 18.0% | 19.2% | |

| > high school | 27.1% | 25.4% | 25.3% | 26.4% | 27.1% | 26.0% | |

| Don't know | 5.2% | 4.5% | 4.9% | 3.9% | 4.8% | 3.7% | |

| Father's education | no diploma | 16.9% | 17.9% | 17.1% | 16.5% | 15.0% | 16.6% |

| <high school | 34.5% | 31.0% | 34.0% | 30.7% | 34.7% | 30.6% | |

| high school | 14.2% | 14.3% | 15.8% | 14.7% | 15.8% | 14.1% | |

| > high school | 24.8% | 24.4% | 24.8% | 26.5% | 26.6% | 26.9% | |

| Don't know | 9.7% | 12.3% | 8.7% | 11.7% | 7.8% | 11.8% | |

| Talk with mother about sexuality | easily | 42.1% | 51.8% | 42.9% | 52.0% | 45.6% | 54.0% |

| with difficulty | 6.2% | 12.9% | 6.2% | 13.6% | 6.1% | 12.8% | |

| didn't want to talk about it | 50.2% | 34.2% | 49.3% | 33.9% | 46.5% | 32.6% | |

| didn't see the mother | 1.7% | 1.0% | 1.6% | 0.5% | 1.8% | 0.6% | |

| Talk with father about sexuality | easily | 38.3% | 14.6% | 39.6% | 14.2% | 41.0% | 15.1% |

| with difficulty | 9.1% | 13.6% | 7.9% | 12.8% | 8.1% | 13.5% | |

| didn't want to talk | 48.7% | 68.3% | 49.1% | 69.8% | 47.4% | 67.7% | |

| didn't see the father | 4% | 3.4% | 3.4% | 3.2% | 3.5% | 3.6% | |

| Importance of religion | very important | 4.9% | 5.8% | 4.3% | 4.3% | 3.6% | 3.6% |

| not very important | 95.1% | 94.2% | 95.7% | 95.7% | 96.4% | 96.4% | |

| Method used at 1st sex (1st partner) | no method | 6.1% | 7.7% | 5.8% | 5.9% | 4.1% | 4.0% |

| other | 1.3% | 1.7% | 1.0% | 1.4% | 1.2% | 1.5% | |

| condom alone | 76.1% | 56.5% | 76.7% | 58.2% | 77.2% | 57.7% | |

| very effective method alone | 2.0% | 5.0% | 2.0% | 3.3% | 2.4% | 3.6% | |

| very effective method & condom | 14.4% | 29.1% | 14.3% | 31.3% | 15.2% | 33.3% | |

| Method used at 1st sex (2nd partner) | no method | 8.8% | 8.7% | 7.7% | 9.3% | ||

| other | 0.8% | 0.7% | 0.9% | 0.5% | |||

| condom alone | 67.7% | 36.0% | 67.0% | 35.1% | |||

| very effective method alone | 6.2% | 12.4% | 6.6% | 13.0% | |||

| very effective and condom | 16.5% | 42.2% | 17.8% | 42.2% | |||

| Ever Used Condom | yes | 93.3% | 89.9% | 94.4% | 92.9% | 95.6% | 94.2% |

| no | 6.6% | 10.1% | 5.6% | 7.1% | 4.4% | 5.8% | |

Table 2.

Factors associated with any use of any contraception, with condom use or with use of very effective methods of contraception at first intercourse with first or second partner (N=1,823)

| Any Method Use (yes/no) – aOR (95%CI) | Condom Use (yes/no) – aOR (95%CI) | Very effective Method Use (yes/no) – aOR (95%CI) | Dual Method Use (yes/no) – aOR (95%CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Observations | 1,588 | 2,018 | 1,588 | 2,018 | 1,588 | 2,018 | 1,588 | 2,018 |

| Number of IDs | 794 | 1,009 | 794 | 1,009 | 794 | 1,009 | 794 | 1,009 |

| Partner (Ref : 1st Partner) | ||||||||

| 2nd Partner | 0.6** (0.4-0.9) | 0.6* (0.4-1.0) | 0.5*** (0.3-0.7) | 0.4*** (0.3-0.5) | 1.5** (1.2-1.9) | 2.5*** (2.1-2.9) | 1.2** (0.9-1.5) | 1.7*** (1.4-1.9) |

| Current Age (ref : 15-19 years) | ||||||||

| 20-24 years | 1.3 (0.5- 2.9) | 1.3 (0.6- 2.9) | 1.2 (0.6-2.1) | 1.0 (0.6-1.8) | 1.4 (0.8-2.4) | 2.3*** (1.5-3.4) | 1.5 (0.8-2.7) | 2.2 (1.4-3.3) |

| 25-29 years | 1.1 (0.4-2.8) | 1.1 (0.5-2.6) | 1.3 (0.6-2.6) | 1.0 (0.5-1.8) | 1.3 (0.8-2.3) | 2.7*** (1.7-4.2) | 1.7 (0.9-3.2) | 2.7 (1.7-4.4) |

| Age at first sex (ref : 16+ years) | ||||||||

| <16 years | 1.2 (0.7-2.2) | 0.7 (0.4 -1.2) | 1.4 (0.9-2.3) | 0.8 (0.6 -1.2) | 0.7 (0.5-1.0) | 0.7* (0.5 -0.9) | 0.7 (0.5-1.1) | 0.6 (0.5 -0.9) |

| Country of Birth (ref : French born) | ||||||||

| Foreigh born | 0.2** (0.1-0.4) | 0.3** (0.1-0.7) | 0.2*** (0.1-0.5) | 0.5* (0.2-0.9) | 0.6 (0.3-1.5) | 0.3*** (0.1-0.6) | 0.4 (0.2-1.1) | 0.3** (0.1-0.6) |

| Education (Ref : <high school) | ||||||||

| High School | 3.3** (1.5-7.2) | 1.3 (0.7 – 2.6) | 3.0*** (1.7-5.7) | 1.5 (0.9-2.4) | 1.0 (0.6-1.6) | 1.0 (0.6-1.5) | 1.3 (0.7-2.2) | 1.0 (0.7-1.6) |

| >high school | 2.5** (1.2-5.3) | 3.6*** (1.9-6.8) | 2.2** (1.3-4.0) | 1.8** (1.2-2.8) | 1.2 (0.8-1.9) | 1.1 (0.7-1.6) | 1.5 (0.9-2.59) | 1.1 (0.7-1.7) |

| Still in school | 3.6** (1.4- 9.3) | 1.4 (0.6-3.4) | 3.5** (1.7-7.4) | 1.5 (0.8-2.7) | 1.2 (0.7-2.2) | 0.9 (0.6-1.5) | 1.9* (1.0-3.7) | 1.1 (0.7-1.8) |

| Mother's Education (ref : No Diploma) | ||||||||

| <High School | 1.2 (0.6-2.4) | 1.5 (0.8-2.9) | 1.6 (0.9-3.0) | 1.4 (0.9-2.3) | 0.8 (0.5-1.4) | 1.0 (0.6-1.5) | 1.1 (0.6-1.8) | 1.1 (0.7-1.7) |

| High School | 1.6 (0.7-3.4) | 3.9** (1.6-9.5) | 1.6 (0.8-3.1) | 2.3** (1.3-4.1) | 0.9 (0.5-1.7) | 1.2 (0.7-1.9) | 1.1 (0.6-2.1) | 1.3 (0.8-2.2) |

| > High school | 1.5 (0.7-3.4) | 2.1 (0.9-4.7) | 1.4 (0.7-2.7) | 1.8* (1.0-3.0) | 1.0 (0.5-1.7) | 1.1 (0.7-1.8) | 1.0 (0.6-2.0) | 1.2 (0.7-1.9) |

| Don't Know | 4.3* (1.1-16.9) | 1.1 (0.4-3.3) | 4.8** (1.5-15.0) | 1.2 (0.5-2.9) | 0.5 (0.1-1.6) | 1.9 (0.8-4.9) | 1.1 (0.3-3.6) | 2.3 (0.9-5.9) |

| Father's Education (ref : No deploma) | ||||||||

| <High School | 1.3 (0.6 -2.7) | 1.5 (0.8 -2.9) | 0.9 (0.4-1.7) | 1.8* (1.1 -2.9) | 1.3 (0.7 -2.2) | 1.1 (0.8-1.7) | 1.1 (0.6 -1.9) | 1.4 (0.9 -2.2) |

| High School | 1.0 (0.5-2.4) | 1.4 (0.7-3.0) | 0.7 (0.3-1.5) | 1.7 (1.0-3.0) | 1.3 (0.7-2.5) | 1.3 (0.8-2.1) | 1.0 (0.5-2.1) | 1.7* (1.0-2.7) |

| > High school | 1.8 (0.7-4.4) | 1.9 (0.8-4.5) | 1.3 (0.6-2.8) | 1.9* (1.0-3.5) | 1.0 (0.5-1.9) | 1.0 (0.61.6) | 1.0 (0.5-1.9) | 1.3 (0.8-2.1) |

| Don't Know | 0.3*** (0.1-0.6) | 1.4 (0.6-3.3) | 0.2*** (0.1-0.5) | 1.6 (0.9-3.0) | 1.8 (0.8-4.13) | 1.4 (0.8-2.3) | 1.1 (0.4-3.0) | 1.6 (0.9-2.8) |

| Comfort Talking with Mother about Sexuality (ref : spoke with ease) | ||||||||

| Difficulty | 1.7 (0.5 6.3) | 0.4** (0.2 -0.9) | 3.1 (0.8 -11.3) | 1.0 (0.6 -1.6) | 0.8 (0.4 -1.6) | 0.5** (0.3 0.7) | 1.4 (0.7-3.0) | 0.6* (0.4-0.9) |

| Didn't want to | 0.7 (0.3 -1.5) | 0.6* (0.3 -1.0) | 1.0 (0.6 -1.9) | 0.9 (0.6 -1.3) | 0.9 (0.6-1.3) | 0.6** (0.4 -0.8) | 1.2 (0.7-1.8) | 0.6** (0.5 0.9) |

| N/A (wasn't there etc.) | 2.6 (0.6-11.6) | 0.1*** (0.0- 0.4) | 2.6 (0.7-9.3) | 0.4 (0.1- 1.9) | 0.3 (0.1- 1.2) | 0.4 (0.1- 1.4) | - | 0.5 (0.1- 1.9) |

| Comfort Talking with Father about Sexuality (ref : spoke with ease) | ||||||||

| Difficulty | 0.9 (0.3-2.7) | 1.7 (0.7-4.0) | 0.7 (0.2 -1.9) | 0.9 (0.5-1.6) | 1.1 (0.6-2.1) | 1.2 (0.8-1.9) | 0.8 (0.4-1.6) | 1.0 (0.6-1.6) |

| Didn't want to | 0.9 (0.4-2.0) | 1.3 (0.6-2.5) | 0.7 (0.4 -1.3) | 0.8 (0.5-1.3) | 1.1 (0.7-1.6) | 1.1 (0.8-1.6) | 0.9 (0.6-1.4) | 0.9 (0.7-1.3) |

| N/A (wasn't there etc.) | 2.4 (0.5-12.9) | 1.8 (0.5-7.0) | 1.5 (0.4- 5.7) | 1.8 (0.6-4.8) | 0.8 (0.3-1.9) | 0.5 (0.2-1.1) | 0.8 (0.3-2.5) | 0.5 (0.2-1.3) |

In order to complement the cross-sectional analysis, we conducted a longitudinal analysis that illuminated individual changes in these behaviors (from first to second partner). We explored switching patterns in condom use and very effective method use within first partnership (from first sex to subsequent intercourse with first partner) and between partners (Figures 1 and 2). In addition, we statistically assessed the predictive effect of contraceptive use at first sex ever and of contraceptive switching with first partner on use at first sex with second partner (Table 3). This switching analysis was only carried out for respondents who had used contraception at first sex since the number of individuals who did not use any form of contraception was too small (n=50, 3.13%) to create stable models. All analyses are stratified by sex (and tested with interactions) as we anticipated the predictors of contraceptive trajectories would differ.

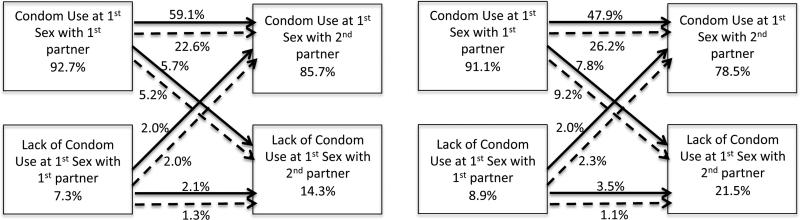

Figure 1. Individual Trajectories in Condom Use (Males - Left and Females - Right).

Solid lines indicate no switching of condom use in the first partnership. Dotted lines indicate switching of condom use in the first partnership

Percentages presented along the dotted and solid lines represent the percentage of respondents according to condom use transitions within first partnership and between first and second partner among the full sample of 1593 respondents who had at least 2 partners more than 1 act of intercourse with each (n=700 for young men; n=893 for young women). For example 59.1% of all males used a condom at first sex with first partner, did not stop using condoms with first partner and used a condom at first sex with second partner

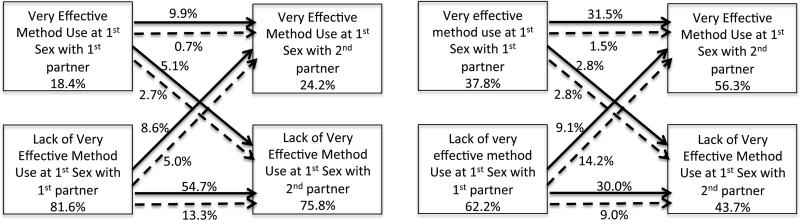

Figure 2. Individual Trajectories in Very Effective Method Use (Males- Left and Females - Right).

Solid lines indicate no stopping of medical method use in the first partnership

Dotted lines indicate stopping of medical method use in the first partnership

Percentages presented along the dotted and solid lines represent the percentage of respondents following each transitions of use of very effective methods within fist partnership and between first and second partner among the full sample of 1593 respondents who had at least 2 partners more than 1 act of intercourse with each (n=700 for young men; n=893 for young women). For example 31.5% of all females used a very effective at first sex with first partner, did not stop using a very effective method with first partner and used a very effective method at first sex with second partner

Table 3.

Prediction Models

| Any Method Use | Condom Use | Very Effective Method Use | Dual Method use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Odds of Using Any Method/Condoms/very effective Methods/dual methods at first sex with 2nd Partner according to usage of the method at first sex with 1st Partner | ||||||||

| VARIABLES | (1) Adjusted odds ratio | (2) Adjusted odds ratio | (3) Adjusted odds ratio | (4) Adjusted odds ratio | (5) Adjusted odds ratio | (6) Adjusted odds ratio | (7) Adjusted odds ratio | (8) Adjusted odds ratio |

| Use at 1st Intercourse | 8.1*** (3.1 - 21.3) | 4.53** (1.7 - 11.9) | 6.5*** (3.2 - 12.9) | 3.7*** (2.1 - 6.4) | 7.5*** (4.7 - 12.0) | 11.0*** (7.4 - 16.3) | 12.6*** (7.4 – 21.3) | 8.6*** (6.0 - 12.2) |

| Observations | 794 | 1,009 | 793 | 1,007 | 794 | 1,009 | 744 | 1009 |

| Odds of Using Any Method/Condoms/ very effective Methods/dual methods at first sex with 2nd Partner according to discontinuation of the method with 1st Partner (among respondents who used the method at first sex with first partner) | ||||||||

| Switching During 1st Partnership | 0.5 (0.2 - 1..2) | 0.3** (0.1 - 0.6) | 0.4** (0.2 - 0.8) | 0.4*** (0.2 - 0.6) | 0.1*** (0.03 - 0.4) | 0.1*** (0.03 - 0.2) | 0.2*** (0.04 - 0.8) | 0.1*** (0.02 - 0.2) |

| Observations | 674 | 854 | 648 | 806 | 131 | 350 | 117 | 337 |

These models are all adjusted for age at the time of the survey, age at first sex country of birth, the respondent's education, father's and mother's education, ease of speaking with mother and father about sexuality

All analyses were weighted with survey weights using svy commands in Stata.

Results

Description of Study Sample and Contraceptive Use

The socio-demographic characteristics of “Population 2” (n=1,823) as well as the “Population Switch” (n=1,593) were similar to the larger population (n=2,657) (Table 1) (less than 1% of either males or females had missing data for any variable). The mean age of “Population 2” was 23.2 years. 31% had not completed high school at the time of the survey and 29% had some college or graduate education. 47% reported it had been easy to talk with their mother about sexuality while a little over a quarter felt comfortable talking with their father. The mean age at sexual debut was 16.2 years for men and 16.7 for women (p<0.05).

A vast majority of young people used a condom at first intercourse either alone (56.5% of women and 76.1% of men) or in combination with very effective methods (31.1% of women and 14.4% of men). Few used very effective methods alone at first sex (3.3% for women and 2.0% for men). Altogether 5.9% of women and 5.8% of men indicated not using contraception at first sex (Table 1).

Analyses of preventive behaviors at first sex with second partner show an increase in non-use: 8.7% of women and 8.8% of men did not use any method at first intercourse with second partner. This was mostly driven by a drop in condom use (from 89.5% to 78.2% for women and 91% to 83.5% for men). Conversely there was an increase in use of very effective methods (34.6% to 54.6% for women and 16.3% to 22.7% for men).

Analysis of Factors Associated with Contraceptive Use at first Sex with either partner

Analyses of factors associated with the use of any method at first sex with a new partner (1st or 2nd) are summarized in Table 2. This analysis includes 3,646 datapoints (corresponding to first sexual encounters with first and second partners among the 1,823 respondents who reported at least 2 partners). Predictors of any method and condom use were very similar, as condoms were by far the most popular method used. Use of any method or condoms increased with educational level, especially for men, with an additional effect of father's and mother's educational attainment for women. Results also suggest lower levels of use at first intercourse among participants who were foreign born. Ease of talking about sexuality with mother was associated with greater use of any method for women but had no effect for men (test of interaction, p=0.06). Talking about sexuality with either parent was not associated with condom use at first intercourse, regardless of respondents’ sex.

The predictors of use of very effective methods as well as dual method use were different from those related to condom use alone (Table 2). Specifically, neither the respondent's nor their parents’ education predicted very effective method use or dual use. Age at the time of the survey and at first sex were both associated with very effective and dual method use among women. Women aged 25-29 years at the time of the survey were more likely to have used a very effective or a dual method at first sex than the younger cohorts. Irrespective of a period effect, women who initiated sexual intercourse under the age of 16 years were less likely to have used a very effective method at first intercourse. Talking about sexuality with their mother increased the odds of using a very effective or dual method for women.

Analyses revealed a significant difference in preventive behaviors between first and second partner after adjusting for the other factors discussed above. Specifically, the odds of using condoms at first sex with second partner dropped significantly as compared to first partner while the odds of using a very effective method increased. This increase was particularly marked for women (OR=2.5) as compared to men (OR=1.5) (test of interaction, p=0.01) (Table 2). The decline in condom use drove the overall decline in contraception between first and second partner (odds of any use decreased by 40%) even though the increase in very effective method use drove an increase in dual method use.

Longitudinal Analysis of Preventive Behaviors within and between Partnerships

Analyses of individual respondents’ switching patterns within first partnership and between first and second partnerships were conducted among the 1,593 respondents who had at least two opposite sex sexual partners with whom they had intercourse more than once. Subject-specific switching patterns are presented separately by sex and by method (condom and very effective method use) in Figures 1 and 2. The dotted lines in these figures represent respondents whose contraceptive practices changed within their first partnership, while solid lines indicate no change.

Overall, a majority of respondents did not change their contraceptive practices within first partnership or across partnerships, regardless of method: 78.4% of men and 81.4% of women never switched with respect to any method use (not shown). Likewise, 61.2% of men (59.1% who always used and 2.1% who never used) and 51.4% of women (47.9% who always used and 3.5% who never used) never switched with respect to condom use (Figure 1). This was also true for very effective method use where 65.6% of men (9.9% who always used and 54.7% who never used) and 61.5% of women (31.5% who always used and 30% who never used) never switched with respect to very effective method use (Figure 2).

Switching patterns within and across relationships indicate that changes in condom usage within first partnership were the most common. Over a quarter of men (27.8%) and more than a third of women (35.4%) stopped using condoms before the end of their relationship (and 2.3% of men and 2.4% of women started use with first partner after first sex) (Figure 1). Over a quarter of women (27.4%) and 21.7% of men described changes in use of very effective methods with first partner, with almost all reflecting uptake of such methods after first intercourse (24.1% of women and 18.3% of men) (Figure 2). Altogether 13.2% of men and 10.6% of women stopped using any method with first partner, while 2.7% of men and 2.6% of women started using a method after first sexual intercourse (not shown). Finally, while most men (59.9%) never combined condom and very effective method use within first partnership, dual method use rose sharply with first partner after first intercourse among women (24%) (data not shown).

Analyses of switching patterns across partnerships, comparing first sexual intercourse with first and second partner show differences by method. Only 5.6% of all men and 6.1% of all women switch from any method to no method between partners, while 3.2% of all men and 2.9% all women switched from no method to any method (not shown). The same analysis exploring condom use reveals a significant drop in condom use: 10.9% point drop for men and 17.0% point drop for women (4.0% of men and 4.4% women used a condom at first sex with second partner but had not done so with their first partner) (Figure 1). The uptake of very effective methods across partnerships was observed for 13.6% of men and 23.3% of women. Conversely, 7.8% of men and 4.7% of women had used a medical method at first sex with first partner but not with second partner (Figure 2). In terms of dual method use, the decline in condom use mostly offset the uptake of very effective methods among men: 8.9% became new dual method users at first sex with second partner while 6.7% who had been dual users at first sex with first partner no longer were with second partner. For women, the uptake of very effective methods drove a substantial increase in dual method use at first sex with second partner, despite the drop in condom use: 17.7% were dual method users at first sex with second partner but not with first partner. Conversely, 8.3% of women had been dual users at first sex with first partner but were no longer dual users with their second partner.

Predictive effect of Behaviors with 1st Partner on Behavior with 2nd Partner

Across all measures – any method, condom, or very effective methods – use at first sex with first partner was highly predictive of use of the same method at first sex with second partner (Table 3). Further analysis including method discontinuation within first partnership, reveals a negative effect such that stopping any of the methods with first partner was associated with lower odds of using any of the methods at first sex with second partner (Table 3).

Discussion

This study reveals changes in preventive behaviors during the early stages of sexual life. Over time, young people in France move towards use of more effective contraceptive methods but are less likely to use condoms – including at first intercourse with their second partner. This is a positive shift for the purpose of pregnancy prevention but a challenge in terms of STI prevention. The decline in condom use is concerning as the risks of STIs are high in this age group14,15 while switching from one method to another presents opportunities for gaps in coverage or discontinuation of a new method.

Our results also indicate that preventive behaviors with both partners are socially determined with sustained inequalities in use. New immigrants and people with less education are less likely to use condoms than more highly educated or native-born people. This may contribute to the disparities in STI rates by educational level observed in France.16 These findings are also consistent with higher rates of STIs by deprivation level seen in Britain and the US.17,18

In our study, men and women report different contraceptive practices. In particular, men report less use of very effective methods. As very effective methods are primarily female controlled, a lack of communication between partners about contraceptive practices driven by the prevailing gender norm that women are expected to take sole responsibility for contraception, may result in men being unengaged in contraceptive decisions.19 It is unclear from these data whether men know about their partner's use of very effective methods but the lower reported frequency of use of very effective methods by men suggests communication about pregnancy prevention with their partners may be lacking.20 Future research should explore whether decisions about contraception – beyond STI prevention – fall exclusively on women or whether these decisions are shared with their male partners. If men are less attuned, gender transformative interventions that challenge norms about masculinities and promote men's participation, not only as partners but also as actors of their own reproductive decisions, may improve both men and women's sexual and reproductive health outcomes.21

Another layer of the gendered results may be driven by the fact that teens learn about sexuality and contraception from their parents but parents talk differently to sons than to daughters. Numerous studies have documented the role of parental communication on teen sexual and reproductive health outcomes.22,23 We found that girls who were comfortable talking to their mother about sexuality were more likely to use effective contraception though the same was not true for boys. These results suggest a lack of effective communication between parents and adolescent males on sexual and reproductive health issues – particularly around pregnancy prevention that results in a missed opportunity to engage young men in taking more responsibilities in pregnancy and STI prevention.

This study shows important shifts in preventive behaviors that operate within first partnerships. The decline in condom has sustainable effects on preventive behaviors with a subsequent partner. For women, especially, the transition from condom to oral contraception seems to reduce their likelihood of using a condom with a new partner, suggesting the need to emphasize dual protection messages to prevent STI transmission in the context of new partnerships24,25 while continuing to encourage young women to use more effective pregnancy prevention methods if they state a lack of desire to get pregnant.

The retrospective nature of the data does not provide a rich source of contextual information to investigate time varying individual, relationship, and social circumstances informing these behaviors. In particular, preventive sexual practices are negotiated between partners and therefore depend on the characteristics of the partner and the nature of the relationship. For example, previous studies among US teens indicate lower usage when the age gap between partners increases suggesting that the perceived ability to negotiate contraceptive use may be important for usage.26 More positive as well as more negative aspects of relationships are also shown to be associated with decreased usage of contraceptives or usage of condoms. 27–29

This study offers new insights on young people's contraceptive trajectories in the early stages of sexual life. Most importantly, we found a decrease in contraceptive usage during first partnership, with sustained negative impact with second partner. Additionally we found evidence of gaps in usage that should be addressed by healthcare professionals and a lack of knowledge on the part of men about their partners’ contraceptive use. Future studies could explore further the relationship contexts in which the trade-offs between pregnancy prevention and STI prevention observed in our study are negotiated.

Acknowledgements

Hannah Lantos was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (T32 AI050056-12).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Hannah Lantos, Child Trends.

Nathalie Bajos, INSERM U1018.

Caroline Moreau, Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health, Department of Population, Family and Reproductive Health.

References

- 1.Beltzer N, Bajos N. Sexuality in France: Practices, Gender and Health. The Bardwell Press; Oxford, UK: 2012. Contraeptive and Preventive Behaviour: Issues in Negotation at Different Stages of Affective and Sexual Trajectories. pp. 401–423. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avery L, Lazdane G. What do we know about sexual and reproductive health of adolescents in Europe? Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2010;15(sup2):S54–S66. doi: 10.3109/13625187.2010.533007. doi:10.3109/13625187.2010.533007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welti K, Wildsmith E, Malove J. Trends and Recent Estimates: Contraceptive Use Among U.S. Teens and Young Adults. Child Trends; Washington, D.C: 2011. www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Child_Trends-2011_12_01_RB_ContraceptiveUse.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bajos N, Le Guen M, Bohet A, Panjo H, Moreau C. FECOND group. Effectiveness of family planning policies: the abortion paradox. PloS One. 2014;9(3):e91539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091539. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0091539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bajos N, Leridon H, Goulard H, Oustry P, Job-Spira N, COCON Group Contraception: from accessibility to efficiency. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2003;18(5):994–999. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bajos N, Lamarche-Vadel A, Gilbert F, et al. Contraception at the time of abortion: high-risk time or high-risk women? Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2006;21(11):2862–2867. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del268. doi:10.1093/humrep/del268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goulard H, Moreau C, Gilbert F, Job-Spira N, Bajos N, Cocon Group Contraceptive failures and determinants of emergency contraception use. Contraception. 2006;74(3):208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.03.007. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moreau C, Trussell J, Desfreres J, Bajos N. Patterns of contraceptive use before and after an abortion: results from a nationally representative survey of women undergoing an abortion in France. Contraception. 2010;82(4):337–344. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.03.011. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bajos N, Bozon M, Beltzer N, et al. Changes in sexual behaviours: from secular trends to public health policies. AIDS Lond Engl. 2010;24(8):1185–1191. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328336ad52. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e328336ad52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moreau C, Bohet A, Hassoun D, Teboul M, Bajos N, FECOND Working Group Trends and determinants of use of long-acting reversible contraception use among young women in France: results from three national surveys conducted between 2000 and 2010. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(2):451–458. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.04.002. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mmari K, Sabherwal S. A review of risk and protective factors for adolescent sexual and reproductive health in developing countries: an update. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med. 2013;53(5):562–572. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.018. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shafii T, Stovel K, Davis R, Holmes K. Is condom use habit forming?: Condom use at sexual debut and subsequent condom use. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31(6):366–372. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200406000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Svare EI, Kjaer SK, Thomsen BL, Bock JE. Determinants for non-use of contraception at first intercourse; a study of 10841 young Danish women from the general population. Contraception. 2002;66(5):345–350. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(02)00333-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crosby RA, Charnigo RA, Weathers C, Caliendo AM, Shrier LA. Condom effectiveness against non-viral sexually transmitted infections: a prospective study using electronic daily diaries. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88(7):484–489. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050618. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2012-050618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams RL, Fortenberry JD. Dual use of long-acting reversible contraceptives and condoms among adolescents. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med. 2013;52(4 Suppl):S29–S34. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.02.002. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goulet V, de Barbeyrac B, Raherison S, et al. Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis: results from the first national population-based survey in France. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86(4):263–270. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.038752. doi:10.1136/sti.2009.038752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shafii T, Stovel K, Holmes K. Association between condom use at sexual debut and subsequent sexual trajectories: a longitudinal study using biomarkers. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(6):1090–1095. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.068437. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.068437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sonnenberg P, Clifton S, Beddows S, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and uptake of interventions for sexually transmitted infections in Britain: findings from the National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal). Lancet. 2013;382(9907):1795–1806. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61947-9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61947-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raine TR, Gard JC, Boyer CB, et al. Contraceptive decision-making in sexual relationships: young men’s experiences, attitudes and values. Cult Health Sex. 2010;12(4):373–386. doi: 10.1080/13691050903524769. doi:10.1080/13691050903524769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manlove J, Ryan S, Franzetta K. Contraceptive use patterns across teens’ sexual relationships: the role of relationships, partners, and sexual histories. Demography. 2007;44(3):603–621. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bajos N, Marquet J. Research on HIV sexual risk: social relations-based approach in a cross- cultural perspective. Soc Sci Med 1982. 2000;50(11):1533–1546. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00463-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Widman L, Choukas-Bradley S, Helms SW, Golin CE, Prinstein MJ. Sexual Communication Between Early Adolescents and Their Dating Partners, Parents, and Best Friends. J Sex Res. 2013 Dec; doi: 10.1080/00224499.2013.843148. doi:10.1080/00224499.2013.843148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Widman L, Choukas-Bradley S, Noar SM, Nesi J, Garrett K. Parent-Adolescent Sexual Communication and Adolescent Safer Sex Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatr. Nov;2015:1–10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2731. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fortenberry JD, Tu W, Harezlak J, Katz BP, Orr DP. Condom use as a function of time in new and established adolescent sexual relationships. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(2):211–213. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ku L, Sonenstein FL, Pleck JH. The dynamics of young men's condom use during and across relationships. Fam Plann Perspect. 1994;26(6):246–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ford K, Sohn W, Lepkowski J. Characteristics of adolescents’ sexual partners and their association with use of condoms and other contraceptive methods. Fam Plann Perspect. 2001;33(3):100–105, 132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manning WD, Flanigan CM, Giordano PC, Longmore MA. Relationship dynamics and consistency of condom use among adolescents. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2009;41(3):181–190. doi: 10.1363/4118109. doi:10.1363/4118109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manlove J, Welti K, Barry M, Peterson K, Schelar E, Wildsmith E. Relationship characteristics and contraceptive use among young adults. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011;43(2):119–128. doi: 10.1363/4311911. doi:10.1363/4311911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manlove J, Welti K, Wildsmith E, Barry M. Relationship types and contraceptive use within young adult dating relationships. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2014;46(1):41–50. doi: 10.1363/46e0514. doi:10.1363/46e0514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]