Abstract

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a significant health care crisis that affects two million individuals in the United Sates alone and over ten million worldwide each year. While numerous monotherapies have been evaluated and shown to be beneficial at the bench, similar results have not translated to the clinic. One reason for the lack of successful translation may be due to the fact that TBI is a heterogeneous disease that affects multiple mechanisms, thus requiring a therapeutic approach that can act on complementary, rather than single, targets. Hence, the use of combination therapies (i.e., polytherapy) has emerged as a viable approach. Stringent criteria, such as verification of each individual treatment plus the combination, a focus on behavioral outcome, and post-injury vs. pre-injury treatments, were employed to determine which studies were appropriate for review. The selection process resulted in 37 papers that fit the specifications. The review, which is the first to comprehensively assess the effects of combination therapies on behavioral outcomes after TBI, encompasses five broad categories (inflammation, oxidative stress, neurotransmitter dysregulation, neurotrophins, and stem cells, with and without rehabilitative therapies). Overall, the findings suggest that combination therapies can be more beneficial than monotherapies as indicated by 46% of the studies exhibiting an additive or synergistic positive effect versus on 19% reporting a negative interaction. These encouraging findings serve as an impetus for continued combination studies after TBI and ultimately for the development of successful clinically relevant therapies.

Keywords: combination therapies, controlled cortical impact, environmental enrichment, cognition, fluid percussion, neurobehavioral, traumatic brain injury, stem cells

1. Introduction

With an estimated incidence of two million cases in the United States each year (Faul et al., 2010; Albrecht et al., 2015), and several million more worldwide (Hyder et al., 2007), traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a significant health care issue (Max et al., 1991; Thurman and Guerrero, 1999; Hyder et al., 2007; Summers et al., 2009; Coronado et al., 2011). Motor vehicle accidents and falls resulting in a blow to the head are the typical causes of TBI in the general population, whereas blasts and shrapnel from improvised explosive devices are the leading causes for military personnel in active war zones (Ling et al., 2009; Cernak and Noble-Haeusslein, 2010; Young et al., 2015). Brain traumas range from mild to severe with the former being the case in the majority of occurrences (Sosin et al., 1996) and generally not displaying marked behavioral symptoms, while the latter occurs less often, but presents significant motor and/or cognitive dysfunction that can have perpetual adverse consequences on the quality of life (Binder, 1986; Millis et al., 2001). TBI can also increase the risk for other neurological disorders such as seizures (D'Ambrosio et al., 2004; D'Ambrosio and Perucca, 2004; Curia et al., 2011), Alzheimer’s disease (Sullivan et al., 1987; Schofield et al., 1997; Fleminger et al., 2003; Ikonomovic et al., 2004; DeKosky et al., 2007; Gupta and Sen, 2016; Scott et al., 2016) and Parkinson’s disease (Marras et al., 2014; Acosta et al., 2015; Tanner et al., 2015; Taylor et al., 2016), which further exacerbate neurologic dysfunction. Psychiatric comorbidities, such as major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder are also escalated after TBI (Rogers and Read, 2007; Ponsford et al., 2012; Na et al., 2014; Warren et al., 2015; Alway et al., 2016; Scholten et al., 2016) and further limit the successful integration of patients to society and the workforce. Lastly, while the affective toll of TBI on interpersonal relationships with family, friends, and coworkers is incalculable, the economic cost to society accounts for billions of dollars each year (Max et al., 1991; Selassie et al., 2008).

Several pre-clinical treatment approaches, including, but not limited to, anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative strategies (Knoblach and Faden, 1998; Hall et al., 1999; Kline et al., 2004b; Bayir, 2005; Gopez et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2006; Jing et al., 2012; Anthonymuthu et al., 2015; Hellewell et al., 2015), hypothermia (Clifton et al., 1991; Bramlett et al., 1995; Clark et al., 1996; Dixon et al., 1998; Koizumi and Povlishock, 1998; Dietrich and Bramlett, 2015), exogenous administration of neurotrophins (Dixon et al., 1997a; McDermott et al., 1997; Saatman et al., 1997; Sinson et al., 1997; Carlson et al., 2014), pharmacologic agents targeting various neurotransmitter systems (Feeney et al., 1993; Temple and Hamm, 1996; Kline et al., 2000, 2002, 2010; Parton et al., 2005; Baranova et al., 2006; Cheng et al., 2008, 2015; Reid and Hamm, 2008; Bales et al., 2009; Osier and Dixon, 2015; Markos et al., 2016), neutraceuticals (Hoane et al., 2003, 2005, 2008; Gómez-Pinilla, 2008; Guseva et al., 2008; Kokiko-Cochran et al., 2008; Peterson et al., 2012; Agrawal et al., 2015; Vonder Haar et al., 2015), rehabilitative approaches (Hamm et al., 1996; Maegele et al., 2005; Matter et al., 2011; Cheng et al., 2012; Monaco et al., 2013, 2014; Bondi et al., 2014, 2015a,b; Griesbach et al., 2012, 2015; Kreber and Griesbach, 2016), and stem cell transplantation (Gao et al., 2006; Riess et al., 2007; Valle-Prieto and Conget, 2010; Zanier et al., 2011; De La Peña et al., 2015; Patel and Sun, 2016) have been shown to confer motor and/or cognitive benefits in research laboratories using clinically relevant experimental models (Kline and Dixon, 2001, Cernak, 2005; Morales et al., 2005; Morganti-Kossmann et al., 2010; Marklund and Hillered, 2011; Johnson et al., 2015), but few have successfully translated to the clinic (Doppenberg et al., 2004; Beauchamp et al., 2008; Menon, 2009).

The lack of translational success has prompted researchers and clinicians to reconsider the likelihood that single or monotherapeutic approaches may not be the best, or even the appropriate, course of action for optimal recovery after TBI and that combining drug treatments that target multiple and complementary mechanisms of action should be evaluated. Therapies that have been shown to produce beneficial effects on their own and that may provide additive benefit when combined, or that have modest effects on their own but act synergistically to exert positive outcomes should also be pursued. Thus, albeit intuitive, multi-or-combinational therapeutic strategies have historically received only modest attention. However, the volume of such studies has increased since the convening of a TBI and combination therapy workshop that included the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute of Child Health and Development, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and the Department of Veterans Affairs (Margulies et al., 2009). One practical explanation for the dearth of combined therapy studies may be due to the inherent complexity of such an approach. It is well known that TBI produces a plethora of secondary pathophysiological responses (Hayes et al., 1992; Raghupathi, 2004; Greve and Zink, 2009; Veenith et al., 2009; Algattas and Huang, 2013; Agoston, 2015; Laskowski et al., 2015; Fig. 1) at time points that are not well understood and hence, deciding when, how often, and at what dose, to administer a single treatment is difficult, and becomes exponentially more complicated when determining the correct course of action for dual or “cocktail” therapies. A simpler, but more salient reason for the paucity of combined therapy research may be that the majority of early studies using this approach were unsuccessful. Specifically, polytherapies have either been neutral, meaning they failed to alter outcome (Faden, 1993; Smith et al., 1993; Yan et al., 2000; Çelik et al., 2006; Todd et al., 2006; Kline et al., 2007; Öztürk et al., 2008), or have been negative, which is defined as worsening endpoint measures or suppressing the beneficial effects of treatments that on their own were effective (Faden, 1993; Guluma et al., 1999; Kline et al., 2002; Griesbach et al., 2008). Fortunately, a small number of early studies revealed positive benefits (Lyeth et al., 1993; Yan et al., 2000; Menkü et al., 2003; Barbre and Hoane, 2006; Mahmood et al., 2007), suggesting that the correct combination of treatments during the appropriate therapeutic window can be efficacious and thus served as the impetus for further investigation into this complex, but more realistic and potentially more successful strategy for rehabilitation of TBI.

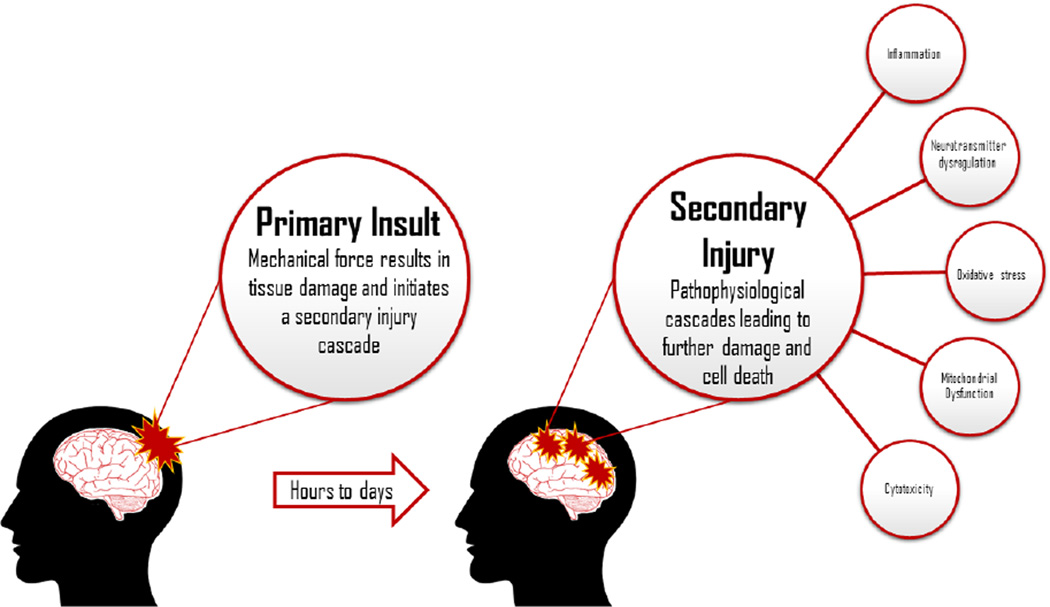

Fig. 1.

Cartoon illustrating the progression and consequences of TBI. As noted, TBI consists of a primary impact, which leads to immediate cell death at the site of injury with subsequent progression into a secondary phase of TBI pathology. The second phase initiates a plethora of pathophysiological cascades that leads to further damage as well as neurobehavioral and cognitive dysfunction. For clarity, only a few of the TBI-induced responses are portrayed.

While combined treatment approaches are also utilized in other central nervous system disorders, such as stroke (Gisvold et al., 1984; Liu et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2012; Ji et al., 2015; Schuch et al., 2016) and spinal cord injury (Koopmans et al., 2009; Tanabe et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2012; Wilems et al., 2015), the aim of this review is to highlight the current state of combinational treatment approaches for neurobehavioral and cognitive recovery in experimental TBI. The review, which is the first, and currently the only, to comprehensively assess the effects of combination therapies on behavioral outcomes after TBI, is based on studies that were found on a PubMed search in March 2016 using the key phrase “combination AND therapy AND traumatic AND brain AND injury” that produced 529 papers. After an initial review of the papers in which the type of CNS injury was determined, 81 papers fit the criteria of “traumatic” brain injury based on currently validated models (Kline and Dixon, 2001, Cernak, 2005; Morales et al., 2005; Morganti-Kossmann et al., 2010; Marklund and Hillered, 2011; Johnson et al., 2015). After selecting the TBI papers an additional review was conducted to ensure that the papers reported complete combination studies (i.e., evaluating each therapy individually before combining) vs. quasi combination (i.e., the addition of therapies without individual confirmation of their effects). Studies that did not fit the criteria were excluded as they precluded determination of individual treatment effects. Moreover, only studies in which behavioral outcomes were assessed and those where treatments were provided post-injury were included as treating pre-injury is not considered clinically relevant, albeit we do acknowledge that such studies can provide valuable information regarding potentially effective therapies. Studies that had an additional insult beyond TBI were also omitted. Lastly, given that some combinational behavioral studies may not have been located due to insufficient or ineffective key words, the review, which consists of 37 papers, may not be exhaustive, although every effort was made.

Because many of the secondary sequelae triggered by TBI often interact with one another, ascribing the combination therapies to finite mechanisms has proven to be a challenge for a concise and clearly delineated review. However, the overlap in targeted mechanisms by the combination therapies coincide with the recommendations put forth by The Combination Therapies for Traumatic Brain Injury Workshop Leaders (2009) that treatments should act on complementary, rather than single, targets. Hence, the review encompasses five broad categories (inflammation, oxidative stress, neurotransmitter dysregulation, neurotrophins, and stem cells, with and without rehabilitative therapies).

2. Inflammation

Proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) induced by TBI contribute to further damage, intensify post-injury symptomatology, and prolong recovery (Shohami et al., 1996; Fan et al., 1995; Lucas et al., 2006; Werner and Engelhard, 2007). Inflammatory reactions triggered by IL-1β attract immune cells to injured brain tissue, stimulate edema formation, and contribute to neuronal death (Lawrence et al., 1998; Clausen et al., 2011). The proinflammatory cytokine, TNF-α, is upregulated early after TBI and promotes neutrophil infiltration and has been associated with neurological dysfunction including impaired motor abilities and cognition, as well as apoptosis (Shohami et al., 1997; Kim et al., 1992). Increases in TGF-β have been reported in cerebrospinal fluid after TBI, with the highest levels detected in the days immediately following injury and attenuation being associated with a reduction in post-injury symptoms (Morganti-Kossman et al., 2002; Cacheaux et al., 2009). To combat the deleterious effects of post-traumatic neuroinflammation, numerous anti-inflammatory monotherapy studies have been conducted with favorable outcomes (Knoblach and Faden, 1998; Gopez et al., 2005; Shohami et al., 1996; for an excellent review see Hellewell et al., 2015). These studies give rise to the theory that polytherapies may be beneficial in reducing adverse molecular events and functional deficits after TBI to a greater extent than monotherapies.

2.1. Positive effect (treatments more efficacious when combined than individually)

2.1.1. Minocycline and N-acetylcysteine

To determine other promising therapies for anti-inflammatory responses, Abdel Baki and colleagues (2010) evaluated minocycline (MINO), N-acetylcysteine (NAC), simvastatin, cyclosporine A, and progesterone (PROG) in adult rats after moderate CCI injury. However, only cyclosporine A and NAC were combined with MINO. Furthermore, all rats in the MINO+ cyclosporine A group died within 4 days of treatment and did not yield behavioral data. Hence, only the specifics of MINO and NAC will be discussed. NAC is known to be a powerful antioxidant with the capability to reduce levels of IL-1β and TNF-α, making it a strong candidate for targeting both the oxidative stress and neuroinflammatory pathophysiology of secondary injury after TBI. MINO (45 mg/kg), NAC (150 mg/kg), or saline were administered intraperitoneally 1 hr after injury and on post-operative days 1–2. Significant protection against demyelination was conferred by both MINO and the combination, with no differences between the two. Behaviorally, MINO + NAC improved active place avoidance after massed training, which suggests that the combination of treatments synergistically produced a positive effect.

A subsequent, quite similar, study conducted by the same group administered MINO and NAC to adult rats that were subjected to a mild CCI injury (Haber et al., 2013). After surgery the rats received three intraperitoneal injections of MINO (45 mg/kg), NAC (150 mg/kg), or their combination at 1 hr, 24 hr, and 48 hr post-injury. The results from the conflict active place avoidance task indicated that the combination treatment paradigm increased cognition as indicated by significantly fewer entrances into the shock zone relative to the vehicle and monotherapy groups. Quantification of Iba-1, a pan-selective marker of microglia, revealed that MINO decreased Iba-1 expression and NAC had no effect compared to the vehicle-treated control group. Unexpectedly, the combination synergistically increased Iba-1 immunoreactivity, but also significantly attenuated CD68 immunoreactivity, an indicator of phagocytic microglia, in the corpus callosum relative to the vehicle and monotherapy groups. No treatment affected infiltrating neutrophils or astrocyte activation, assessed via myeloperoxidase immuno-labeling or glial fibrillary acidic protein expression, respectively. As concluded by the authors, modulation, rather than suppression, of neuroinflammation may have mediated the cognitive benefits observed with the combined MINO plus NAC treatments.

2.1.2. Minocycline and botulinum toxin constraint-induced movement therapy

Rehabilitation regimens often combine a pharmacological agent with some type of physical therapy to target multiple aspects of a patient’s recovery after TBI. In an attempt to mimic the rehabilitation clinic, Lam and colleagues (2013) combined MINO (25 mg/kg beginning 24 hr after CCI injury and daily thereafter until sacrifice at 7, 12, and 16 days) and botulinum toxin constraint-induced movement therapy (Botox physical therapy; BPT) to determine its effects on functional outcome, lesion volume, microglial, and astrocyte expression. BPT as a treatment involved injecting botulinum toxin A (Botox-A) into the unimpaired forelimb 1 day after injury to force the use of the impaired forelimb. Commencing on day 5 post-injury and continuing for 2 weeks thereafter, rats assigned to physical therapy participated in daily rope climbing, net traversal, and wheel running for 10 min each. An additional 30 min was spent force-walking. Behavioral tests were conducted from day-7 to day-56 post-TBI. In the forelimb use asymmetry task, the BPT and MINO + BPT groups were less impaired relative to MINO alone and the vehicle controls. Neither MINO nor BPT alone improved fine motor performance, but the combination therapy was significantly improved compared to the TBI controls. Cognitive function was preserved by MINO alone and the combination of MINO + BPT vs. the TBI vehicle controls. Moreover, the MINO alone, BPT alone, and combination treatment groups expressed significantly fewer activated microglia in the perilesional cortex and dentate gyrus as compared to injured controls. No significant differences existed between treatment groups, indicating that both monotherapies were equally efficacious at reducing this inflammatory marker compared to the combination treatment. GFAP expression was significantly reduced in the MINO and MINO + BPT groups vs. the vehicle-treated TBI group, indicating reduced astrocytic inflammatory activation. Taken together, these findings suggest that although both BPT and MINO were effective, their combination resulted in better performance in several endpoint measures (Lam et al., 2013). The data suggest that it may be beneficial to provide this combination to cover a wide range of injury-induced deficits.

2.1.3. Progesterone and nicotinamide

Nicotinamide (NAM), the amide form of vitamin B3, increases the bioavailability of adenosine triphosphate in neurons and has been reported to benefit neurobehavioral, cognitive, and histological outcomes after TBI (Hoane et al., 2006, 2008; Vonder Haar et al., 2011, 2014). PROG has also been shown in numerous studies to confer significant benefits after experimental brain injury (Cutler et al., 2007; Cekic et al., 2009; Cekic and Stein, 2010; Stein and Cekic, 2011). Both treatments work in part by regulating signaling pathways involved in neuroinflammation and as such, Peterson and colleagues (2015) hoped to augment this mechanism by administering these agents alone and in combination, to explore effects on behavioral outcome, lesion volume, neuronal degeneration, and astrocyte activation. To this end, adult male rats received a CCI injury of moderate severity and subsequently received NAM (75 mg/kg loading dose and 12 mg/kg/h infusion thereafter), PROG (75 mg/kg loading dose at 4 h post-injury and 10 mg/kg every 12 h thereafter until sacrifice), their combination, or vehicle. While all treatment groups performed better than the vehicle-treated controls on some motor tasks, the combination paradigm was significant better, suggesting an additive effect. Moreover, Fluoro-Jade+ and GFAP+ cell reactivity was reduced significantly more in the combination group relative to both individual treatments. Indicating a synergistic effect, the combination treatment was the only group exhibiting a reduction in cortical lesion volume 24 hr after TBI. However, that benefit was lost when lesion volume was again assessed at 29 days (Peterson et al., 2015). Albeit two large Phase III clinical trials evaluating PROG recently concluded with negative results (Stein, 2015), the current studies suggest that perhaps PROG may still be effective if combined with NAM or other therapeutic approaches at appropriate times after TBI.

2.1.4. Lithium and valproate

Lithium has been shown to decrease TNF-α and GFAP positivity after weight drop TBI (Ekici et al., 2014). It has also been shown to reduce microglial activation and cyclooxygenase-2 induction as well as improve motor function and attenuate anxiety-like behaviors after CCI injury (Yu et al., 2012). In a murine model of TBI, lithium was reported to attenuate cerebral edema, reduce the expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1β, and enhance spatial learning in a water maze task (Zhu et al., 2010). The acute administration of valproate to TBI rats has been reported to improve BBB integrity and enhance motor and cognitive function (Dash et al., 2010). Given the beneficial effects on behavioral and inflammatory responses with lithium and valproate when provided singly, Yu and collaborators (2013) set out to evaluate the potential synergistic effect of their combination on lesion volume, BBB integrity, and motor function. Briefly, adult male mice received a CCI injury of moderate severity and then were administered sub-therapeutic doses of lithium (1 mEq/kg), valproate (200–300 mg/kg), their combination, or saline intraperitoneally 15 min after injury and once daily for 3 weeks. The combination treatment attenuated cortical lesion volume BBB disruption, and hippocampal degenerating neurons, while neither lithium nor valproate differed from saline in any assessment. Although lithium alone, but not valproate, improved motor function relative to the saline-treated TBI controls, the combination paradigm produced a synergistic benefit. These data suggest that the combination of sub-therapeutic doses of lithium and valproate may be a strategy worth pursuing further as a treatment for TBI.

2.1.5. Simvastatin and fenofribrate

Growing clinical evidence suggests that the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors, otherwise known as “statins,” may possess neuroprotective properties including the inhibition of serum cholesterol biosynthesis and anti-inflammatory actions (Cucchiara and Kasner, 2001; Weitz-Schmidt et al., 2001). In addition, statins have been shown to reduce cerebral hypoperfusion and ischemic injury after TBI by increasing cerebral blood flow via upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (McGirt et al., 2002). Fenofribrate, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α agonist has also been shown to confer neuroprotective, anti-edematous, and functional improvements due to its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties (Besson et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2007), but has not been included in a combination paradigm. Hence, Chen and colleagues (2008) targeted vasogenic edema and neurological outcome utilizing the combination of simvastatin (37.5 mg/kg; p.o.) and fenofribrate (50 mg/kg; p.o.). The treatments were administered at 1 hr and 6 hr after moderate FP injury and the results were compared to the single therapies and vehicle controls. Neurological assessments and motor function, assessed using a modified version of the Feeney beam-walk task (Feeney et al., 1982) were conducted at 6, 24, and 48 hr after injury, and edema was assessed at 24 hr and 48 hr. The combined treatment significantly increased neurological scores and enhanced beam-walk performance, as well as significantly reduced edema and lesion volume compared to all other injured groups. Furthermore, a delayed treatment regimen in which treatments were administered at 3 hr and 8 hr post-injury showed that despite not attenuating edema at 48 hr, the combination group significantly improved motor function compared to the monotherapies and vehicle. Taken together, these findings reveal synergistic benefits to motor recovery, edema, and tissue loss with the combination of simvastatin and fenofibrate. However, as reflected by the data, relatively early treatment is necessary to combat edema.

2.2. Neutral effect (treatments neither more efficacious nor deleterious when combined than individually)

2.2.1. Melatonin and minocycline

To evaluate the potential behavioral (spatial learning) and histological (spared cortical tissue) efficacy of anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory treatments, Kelso and colleagues (2011) administered melatonin (5 mg/kg) and MINO (40 mg/kg) alone and in combination to adult male rats subjected to a CCI of mild severity (1.5 mm tissue deformation). Treatments were provided at 5 min and 60 min post-TBI (melatonin) and once per day beginning on day-1 post-injury and continuing through day-4 post-injury (MINO). The early dosing regimen of melatonin was chosen due to the acute response of free radical production after injury, while the delay in MINO was to allow for an initial microglial response. No differences were observed in cognitive performance, cortical tissue sparing, or attenuation of immunohistochemical markers of microglia activation. The lack of benefits with one or any combination of treatments is surprising as others have shown both treatments to enhance cognition when provided singly (Campolo et al., 2013; Haber et al., 2013; Lam et al., 2013). The lack of efficacy in the current study may be due to dose and timing issues.

2.2.2. Simvastatin and vitamin C

Statins have been reported to confer neuroprotective effects after TBI (Lu et al., 2007; Li et al., 2014) and have been combined with other therapies. Vitamin C exhibits antioxidant properties, which have been shown to protect against a number of disease pathologies (Engler et al., 2003; Sánchez-Moreno, 2004). To determine the effect of combined simvastatin and vitamin C on TBI-induced inflammatory responses and neurological function (grip strength), Wang and colleagues (2014) subjected adult male rats to a TBI of moderate severity via a weight-drop and randomized them to receive simvastatin (15 mg/kg daily for 7 days post-injury), vitamin C (20 mg/kg daily for 3 days post-injury), or both. All treatment paradigms significantly reduced intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) expression and neurological deficits relative to vehicle controls, but there was no additive effect with the combination. Interleukin-10 (IL-10) expression was not impacted by any treatment condition. The authors speculate that the neuroprotective mechanisms may be related to the ability of the treatments to attenuate the cerebral vascular endothelial inflammatory response.

2.2.3. Melatonin and dexamethasone

The combination of melatonin and the synthetic glucocorticoid dexamethasone has been reported to exhibit anti-inflammatory effects at lower doses and with fewer side effects than other steroidal treatments for inflammatory conditions in experimental spinal cord injury and intracerebral hemorrhage (Genovese et al., 2007; Li et al., 2009). To assess their efficacy after TBI, Campolo and associates (2013) administered melatonin (10 mg/kg), dexamethasone (0.025 mg/kg), and their combination after a moderate CCI injury in adult male mice. Treatments were provided intraperitoneally at 1 hr and 6 hr post-injury and motor function plus biased swing activity were assessed 24 hr post-TBI, after which time the mice were sacrificed for determination of inflammatory markers and tissue loss. All treatment groups performed significantly better on both motor tasks and exhibited marked histological benefits relative to the vehicle-treated TBI controls. However, although the combination therapy synergistically reduced BAX protein expression, increased Bcl-2 expression, and significantly reduced tissue infarct area compared to both monotherapies and TBI vehicle controls, it did not confer significantly greater benefits in the rotarod motor task (no data were reported for the elevated body swing test). Taken together, these data support the use of antioxidants in combination with anti-inflammatory therapies to reduce cell death. However, endpoints beyond 24 hr may be necessary to evaluate the potential efficacy of combined treatments on behavioral outcome.

2.3. Negative effect (individual treatment benefits compromised when combined)

2.3.1. Interleukin-10 and hypothermia

Neutrophil accumulation occurs following TBI in response to the early production of cytokines and the upregulation of inflammatory signals such as ICAM-1 on cerebrovascular endothelial cells, beginning as early as 4 hr post-injury and peaking between 24–72 hr (Carlos et al., 1997; Clark et al., 1994; Soares et al., 1995). Anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10, have been shown to inhibit increased production of cytokines and chemokines and the upregulation of ICAM-1, helping to reduce TNF-α production and tissue loss and improving functional recovery after experimental spinal cord injury, middle cerebral artery occlusion, and TBI in rats (Bethea et al., 1999; Spera et al., 1998; Knoblach and Faden, 1998). Hypothermia exerts a protective effect after brain trauma by reducing inflammatory processes and slowing the secondary injury cascade. Studies have shown that in rodent models of ischemia, anti-inflammatory agents coupled with hypothermia are effective in reducing long-term deficits and preserving hippocampal CA1 neurons (Coimbra et al., 1996; Dietrich et al., 1999). Building on these studies, Kline and colleagues (2002) assessed the efficacy of combined human IL-10 (5 µL intravenously at 30 mins post-injury) and moderate hypothermia (32°C within 15 min post-TBI for 3 hr) in adult male rats subjected to a moderate CCI injury. IL-10 significantly reduced neutrophil accumulation, but did not affect functional outcome. In contrast, hypothermia alone conferred significant recovery of motor, cognitive, and histological outcome. Contrary to the hypothesis that the polytherapy approach would provide an additive benefit, combining IL-10 with hypothermia suppressed the efficacy of hypothermia (Kline et al., 2002). The attenuation of hypothermia-mediated benefits when combined with an additional therapy has also been reported by Heegaard and colleagues (1997) who showed that the addition of dichloroacetic acid and/or deferoxamine to hypothermic CCI-injured rats negated the reduction in cerebral edema seen with hypothermia alone relative to TBI controls. While the Heegaard et al study clearly utilizes two different treatments, it was not included in the review because of its quasi combination status (i.e., lack of normothermia groups receiving treatments).

2.3.2. n-acetyl-L-tryptophan and substance P

Endogenous neurogenesis has been shown to be upregulated by substance P following ischemic injury (Park et al., 2007). However, its role in TBI is typically viewed as deleterious. Specifically, substance P is associated with increased secondary damage after TBI, specifically edema formation (Donkin et al., 2009). In contrast, the NK-1 receptor antagonist n-acetyl-L-tryptophan (NAT) prevents substance P-induced axonal damage and improves functional recovery post-injury (Donkin et al., 2011). Despite the known negative effects of substance P in TBI, Carthew and colleagues (2012) decided to use it in a combination paradigm with NAT to test the hypothesis that a single-dose of NAT (2.5 mg/kg, i.v.) 30 min post-weight drop injury of moderate severity in adult male rats would prevent early damage related to substance P, while delayed substance P administration (1 µmol/L, reconstituted in artificial CSF, beginning 48 hr post-injury) would further contribute to neurogenesis after stabilization of the injury microenvironment, with the ultimate result being improved motor behavior. As the data showed, motor performance on a rotarod task was improved with NAT treatment alone, but not with substance P or the combination. In fact, substance P reduced the efficacy of NAT when combined. The immunohistochemical data showed an increase in ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule-1, a marker of microglia activation, after treatment with substance P, but not NAT. The authors speculate that the increase in microglia was detrimental as only the NAT group showed improved behavioral function. These data suggest that caution should be exercised when considering substance P as a component in a combination treatment paradigm.

3. Oxidative stress

Oxidative stress is a critical secondary process resulting from TBI that is caused by free radical attacks on cellular components, leading to biochemical and physiological damage. The toxicity created by free radicals, as well as free radicals themselves collectively comprise what are known as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS). Damage to the endogenous antioxidant system combined with TBI-induced glutamate excitotoxicity can lead to increased production of ROS and RNS, which in turn contributes to lipid peroxidation, malfunction of the mitochondrial electron transport chain, cleavage of DNA, and protein oxidation (Lau and Tymianski, 2010; Cornelius et al., 2013). Oxidative stress affects blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability, leading to edema and neuronal death via intertwined, complex pathways, and ultimately behavioral dysfunction.

3.1. Positive effect

3.1.1. Docosahexaenoic acid and voluntary exercise

The effect of combined therapies in reducing oxidative stress was recently reported by Wu and colleagues (2013). Briefly, adult male rats received a mild fluid percussion (FP) brain injury or sham procedure and then were maintained on a diet high in docosahexaenoic acid (DHA; 1.2%) with or without voluntary exercise for 12 days. DHA and exercise individually enhanced spatial learning in a water maze task as reflected by learning the location of the escape platform significantly quicker than the standard-fed sedentary TBI group. Moreover, the combination treatment group performed significantly better than the monotherapy groups, indicating a more robust effect of the dual therapies. The data further showed that DHA levels were significantly increased with the combination paradigm vs. monotherapies and vehicle-treated TBI controls. Significant increases in acyl-CoA oxidase-1 and 17-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type-4 levels were also observed in the combination group. Lipid peroxidation was reduced significantly more with the combination as levels of 4-hydroxy-2-hexenal (4-HHE) were lower compared to all other treatment groups. Calciumin-dependent PLA2 (iPLA2) was increased in the combination group vs. all other injury groups, regardless of treatment. This crucial molecule involved in metabolism of membrane phospholipids has been implicated in cognitive function and synaptic stability (Schaeffer et al., 2009; Allyson et al., 2012). Along with iPLA2, the DHA-regulated structural synaptic membrane molecule, syntaxin-3, as well as the neural plasticity markers brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and p-Trk B, were increased with the combination treatment regimen beyond that observed with the monotherapies (Wu et al., 2013). Cumulatively, these findings suggest that dietary DHA supplementation and voluntary exercise are not only beneficial after TBI for cognitive function, but also for the enhancement of neural plasticity and protection from oxidative stress-induced secondary injury.

3.1.2. Docosahexaenoic acid and curcumin

In a follow-up combination strategy, Wu and co-workers (2014) again included DHA as a principle component of the combination, but instead of exercise DHA was supplemented with curcumin. The aim was to determine whether post-injury administration of dietary DHA and curcumin would confer benefits to plasma membrane stability, thereby affecting synaptic plasticity and cognitive recovery after moderate FP or sham injury in adult male rats that were randomized into groups receiving 2 weeks of control diet (rat chow), DHA diet (1.2% DHA), curcumin diet (500 ppm), or combined DHA and curcumin. Cognitive performance was assessed with the established Barnes maze (Barnes, 1979) and was conducted for a total of 5 days beginning 1 week after injury. DHA, curcumin, and the combination significantly improved learning performance compared to the control diet group. Additionally, a learning slope analysis revealed that the combined treatments significantly improved learning speed relative to DHA, curcumin, and control diet, indicating an additive cognitive benefit. All treatments significantly attenuated the FP mediated loss of BDNF compared to TBI controls, and although the combined treatment appeared to attenuate the loss better than DHA or curcumin alone, the effect was not different. The FP injury-induced increases in the lipid peroxidation markers 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE) and 4-HHE were reversed by all treatment conditions. Moreover, the combined treatment reduced 4-HHE levels significantly more than either treatment alone, indicting an additive effect. The combination approach also increased DHA levels more than both curcumin and DHA alone. In summary, these findings suggest that curcumin enhances the benefits conferred by DHA when these dietary supplements are combined after experimental TBI, as evidenced by improved cognitive recovery that corresponded with upregulation of BDNF receptor signaling and decreases in lipid peroxidation mediators. In addition to the benefits produced, both strategies are non-invasive, have no known side effects, and are easy to obtain as nutraceuticals, which make them strong candidates for integration into a rehabilitation paradigm after TBI.

4. Neurotransmitter dysregulation

Alterations in various neurotransmitter systems have been reported after TBI. The direction of the change (i.e., increased or decreased levels) is often dependent on timing post injury. Excitotoxicity is a critical process in neuronal death and is produced, in part, by excessive release of glutamate (Faden et al., 1989; Stover et al., 1999; Stover and Unterberg, 2000; Rose et al., 2002; Hinzman et al., 2010, 2012) and serotonin (Busto et al., 1997) early after brain trauma. Moreover, the changes in acetylcholine (Dixon et al., 1996, 1997c; Ciallella et al., 1998), norepinephrine (Dunn-Meynell et al., 1994), and dopamine (McIntosh et al., 1994; Massucci et al., 2004) neurotransmission after TBI may, at least partially, contribute to the neurobehavioral and cognitive impairments observed. Hence, given that physiological and behavioral outcomes are influenced by altered neurotransmitter levels, it is important that therapies be targeted toward regulating the fluctuations of these chemicals. Indeed, several monotherapies have been utilized with significant benefits (for excellent reviews see McIntosh et al., 1998; Kokiko and Hamm, 2007; Wheaton et al., 2009; Bales et al., 2009; Garcia et al., 2011; Cheng et al., 2015), but relatively few combination studies have been conducted. In the polytherapy approaches that have been reported, the primary focus has been on therapies that alter the glutamatergic and serotonergic systems (Cheng et al., 2015).

4.1. Positive effect

4.1.1. Magnesium chloride and riboflavin

The anti-excitotoxic effects of magnesium chloride (MgCl2, 1.0 mmol/kg, 1 h post-injury), riboflavin (B2, 7.5 mg/kg), and their full dose or half-dose combination (0.5 mmol/kg of MgCL2 and 3.75 mg/kg B2) were evaluated in adult male rats after moderate CCI injury. Treatments were administered intraperitoneally 1 hr post-injury and sensorimotor and motor outcomes were assessed on multiple days (Barbre and Hoane, 2006). The authors report that the full-dose combination treatment significantly reduced initial impairment and improved subsequent performance in the vibrissae forelimb placement task relative to the half-dose combination, the monotherapies, and vehicle. All groups improved performance on the tactile adhesive removal task vs. the vehicle-treated TBI group, but did not differ from one another. None of the treatment groups improved lesion volume. Overall, while the monotherapies conferred some behavioral benefit, the optimal outcome was observed with the full-dose combination paradigm.

4.1.2. Buspirone and environmental enrichment

With TBI taking a disproportionate toll on the pediatric population, Monaco and colleagues (2014) sought to investigate the potential efficacy of buspirone and environmental enrichment (EE) after CCI in postnatal day-17 male rats. The first manipulation in the study was an initial dose response experiment to determine the optimal dose (of buspirone) to use in the combination paradigm. The data revealed that 0.1 mg/kg of buspirone conferred significantly greater cognitive and histological benefit compared to vehicle and the lower and higher doses of buspirone. Thus, in the combination approach, buspirone (0.1 mg/kg) or VEH was administered intraperitoneally 24 hr post-injury and once daily for 16 days. EE or standard (STD) housing began immediately after CCI. The data showed that both buspirone and EE significantly improved performance in the water maze task and attenuated the size of the cortical lesion relative to the TBI controls. The combination group performed significantly better in the spatial learning task relative to the monotherapies, which demonstrates a positive additive effect (Monaco et al., 2014).

4.2. Neutral effect

4.2.1. Magnesium chloride and ketamine

In another early study, Smith and colleagues (1993) administered MgCl2 (125 µmol), the non-competitive NMDA receptor antagonist ketamine (4 mg/kg), or their combination to adult male rats subjected to a FP brain injury of moderate severity. Treatments were provided intravenously 15 min post-injury and the rats were subsequently assessed on a water maze task. The findings were compared to vehicle-treated TBI rats and showed that MgCl2 and ketamine, as well as the combination, significantly improved memory retention. However, no significant differences in performance were detected between the three treatment groups, indicating that the combination did not confer additional improvement in memory.

4.2.2. Magnesium sulfate and progesterone

The developing brain is highly vulnerable to excitotoxic damage and subsequent apoptotic neurodegeneration induced by TBI, as there is a higher prevalence of NMDA-mediated Ca2+ influx into immature neurons after injury (Ozdemir et al., 2005, 2012; McDonald et al., 1988). Thus, it is also important to identify therapies that are effective in reducing glutamate excitotoxicity in pediatrics. To this end, Uysal and colleagues (2013) evaluated the effects of a single intraperitoneal injection of magnesium sulfate (MgSO4; 150 mg/kg), PROG (8 mg/kg), or their combination on cognitive outcome, cell death, neurotrophic factor expression, and hippocampal cell sparing after a weight-drop TBI in post-natal day-7 rats (no gender details indicated). Treatments were provided immediately after TBI. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) immunoreactivity was increased in all treatment groups, but the more robust expression was observed in the combination group. Moreover, all conditions enhanced spatial learning and memory in a water maze task and reduced TUNEL positive cells relative to vehicle-treated TBI controls, with no differences observed among the treatment groups, suggesting equivalent benefits in learning and memory and in attenuating apoptosis. Thus, while the combination strategy conferred added benefits to VEGF expression and preservation of intact dentate gyrus neurons, the protection did not yield cognitive benefits beyond that of individual treatments. These findings suggest that the pediatric brain may benefit from combined MgSO4 and PROG treatment to combat excitotoxicity after TBI.

4.2.3. Dizocilpine maleate and hypothermia

It is well established that dizocilpine maleate (MK-801) and hypothermia confer neuroprotection, reduce inflammatory responses, and attenuate functional deficits after brain trauma (Shapira et al., 1990; Clifton et al., 1991; Bramlett et al., 1995; Clark et al., 1996; Dixon et al., 1998; Koizumi and Povlishock, 1998; Goda et al., 2002; Han et al., 2009; Sönmez et al., 2015; Dietrich and Bramlett, 2015), but the effects of their combination is less known, especially in pediatric rats. To address this issue, Çelik and colleagues (2006) produced a TBI via a weigh drop in 17-day-old male and female rats and assigned them to normothermia (36 °C), hypothermia (32 °C), normothermia + MK-801 (0.5 mg/kg at 15 and 45 min after TBI, i.p.) and hypothermia + MK-801. Both MK-801 and hypothermia exerted protective effects on histopathology and neurological function relative to vehicle controls, but no additive effect was observed.

4.2.4. 8-OH-DPAT and environmental enrichment

Seeking to mimic the clinical arena where neurorehabilitation would be provided in concert with a pharmacotherapy, Kline and colleagues combined the serotonin1A (5-HT1A) receptor agonists 8-hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino) tetralin (8-OH-DPAT) and buspirone, which have been reported in numerous studies to confer motor, cognitive and histological benefits when provided singly after a moderate CCI injury (Cheng et al., 2007, 2008, 2015; Kline et al., 2004; Olsen et al., 2012) with EE, a preclinical model of neurorehabilitation that has also been shown to provide significant benefits after experimental TBI (Hamm et al., 1996; Passineau et al., 2001; Hoffman et al., Sozda et al., 2010; de Witt et al., 2011; Matter et al., 2011; Cheng et al., 2012; Bondi et al., 2014).

In the first study in a series of combination therapies evaluating 5-HT1A receptor agonists, adult male rats were subjected to a CCI injury of moderate severity and provided with a single intraperitoneal injection of 8-OH-DPAT (0.5 mg/kg) or saline vehicle 15 min post-injury, followed by immediate and continuous EE housing or STD laboratory housing conditions. The findings revealed that all treatments (i.e., 8-OH-DPAT alone, EE alone, and the combination) significantly improved spatial learning and memory in a water maze task and significantly preserved hippocampal CA3 neurons compared to the vehicle-treated TBI controls. Although the combination treatment was statistically better in the water maze vs. the 8-OH-DPAT only group, an additive effect could not be indicated as the combination group did not differ from the EE only group (Kline et al., 2007). The authors suggest that the lack of an additive effect may be due to the effectiveness of EE producing a ceiling effect.

A follow-up study evaluating the early and acute treatment paradigm attempted to more closely mimic the rehabilitative setting by providing delayed and once daily administrations of 8-OH-DPAT. The rationale was that patients in rehabilitation would likely receive drug therapies more than once during the course of their stay. As such, a CCI injury was induced as previously described (Kline et al., 2007) and the rats were placed in their randomly assigned housing conditions. Treatment with 8-OH-DPAT (0.1 mg/kg) or vehicle began 24 hr later and were provided once daily for 19 days. As was observed with the single administration paradigm (Kline et al., 2007) both individual treatments enhanced motor and cognitive performance, but there was no additive effect. The single treatment approach also provided significant hippocampal CA3 cell sparing vs the non-therapy TBI controls. In contrast, the polytherapy paradigm significantly attenuated TBI-induced medial septum choline acetyl transferase-positive cell loss compared to EE and 8-OH-DPAT alone, which also conferred benefit relative to the STD-housed vehicle-treated TBI control group (Kline et al., 2010). However, the histological benefit did not lead to improved behavioral outcome and based on the criteria of this review, the combination approach in this study is considered to be neutral.

4.2.5. Buspirone and environmental enrichment

In a subsequent study Kline and colleagues (2012) focused on the potential efficacy of buspirone combined with EE. The rationale for using buspirone was twofold. First, buspirone was shown in a thorough dose response study to confer significant benefits after TBI (Olsen et al., 2012) and second, buspirone is widely used clinically to treat anxiety and depression, and thus if effective could facilitate bench-to-bedside translatability as safety and tolerability issues are well known (Chew and Zafonte, 2009). Identical surgical, housing, and drug administration manipulations as described previously (Kline et al., 2010) were followed. The data showed that buspirone (0.3 mg/kg), EE, and the combination (buspirone and EE) significantly improved motor and cognitive performance relative to the non-therapy TBI controls. As observed in the 8-OH-DPAT studies, the combination group performed better than the buspirone-treated group, but did not differ from EE alone, thus precluding an interpretation of additional benefit. The EE paradigm may once again have limited any potential additive or synergistic effects due to its robustness.

4.2.6. Methylphenidate and environmental enrichment

Methylphenidate (MPH) is a dopamine2 receptor agonist that has been shown to enhance motor (Kline et al., 1994) and cognitive (Kline et al., 2000; Wagner et al., 2007) recovery after experimental TBI. In clinical TBI, MPH improves attention, memory, processing speed, and mental fatigue (Whyte et al., 2004; Willmott and Ponsford, 2009; Johansson et al., 2015). Based on the benefits conferred by MPH alone, Leary and colleagues (2016) set to test the hypothesis that combining MPH with EE after a CCI injury of moderate severity in adult male rats would produce greater benefits on behavioral recovery than either treatment individually. Beginning 24 hr after TBI or sham injury, MPH (5 mg/kg; i.p.) or vehicle (1.0 mL/kg; i.p.) was administered once daily for 19 days, while the rats were either in EE or STD housing. Both the MPH and vehicle groups receiving EE exhibited improved motor function compared to the STD-housed vehicle-treated TBI controls, but did not differ from one another. MPH improved cognitive performance when provided alone and also when combined with EE. Lastly, the MPH group receiving EE performed significantly better than the MPH group in STD conditions, but an additive effect cannot be reported as the enriched MPH group did not differ from the enriched vehicle group. As concluded in previous studies on EE and pharmacotherapies, the robustness of EE may have precluded an additive benefit (Kline et al., 2007, 2010; 2102).

4.3. Negative effect

4.3.1. Nalmefene, YM14673, and dextrorphan

In one of the earliest studies evaluating the potential efficacy of combination treatments after TBI to attenuate glutamate-induced excitotoxicity, Faden (1993) intravenously administered the opioid receptor agonist nalmefene (0.1 mg/kg), the thyrotropin releasing hormone analog YM14673 (1.0 mg/kg), and the noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist dextrorphan (10 mg/kg) individually or in combination (nalmefene + YM14673, nalmefene + dextrorphan, and YM14673 + dextrorphan) to adult male rats 30 min after a moderate FP brain injury. Neurological scores were assessed at 24 hr, 1 wk, and 2 wk post-injury and were significantly improved with each individual treatment vs. vehicle-treated TBI controls. While the combinations of nalmefene + YM14673 and nalmefene + dextrorphan did not differ from the monotherapies, the combination of YM14673 plus dextrorphan significantly reduced the efficacy of each individual treatment (Faden, 1993).

4.3.2. Citicoline and voluntary exercise

Citicoline has been reported to reduce TBI-induced deficits in rats (Dixon et al., 1997b; Dempsey and Raghavendra, 2003), albeit a recent clinical trial reported no effects relative to placebo controls (Zafonte et al., 2012). Additionally, voluntary exercise is a rehabilitation paradigm that has been shown to increase cell proliferation, decrease apoptosis, provide neuroprotection, and promote functional recovery after experimental TBI (Itoh et al., 2011; Griesbach et al., 2012, 2015; Kreber and Griesbach, 2016). To determine the potential efficacy of these therapies in combination, Jacotte-Simancas and colleagues (2015) subjected young adult male rats to a mild-moderate CCI injury and assessed functional and histological outcomes following treatment with citicoline (200 mg/kg; i.p. for 4 days), voluntary exercise (20 days of wheel running beginning 4 days after surgery), or their combination compared to vehicle-treated controls. Citicoline and exercise improved object recognition memory when provided singly, but the combination resulted in the loss of benefit at the 24 hr time point. The combination also attenuated some of the histological variables. Whether the negative interaction is due to exercise or citicoline is unknown, but a study by Griesbach and colleagues (2008) showed that when exercise was combined with amphetamine, the increases in plasticity markers observed by each treatment were diminished. In both studies, voluntary exercise was initiated rather early, which may have been a determining factor as the benefits appear to be time dependent with delayed implementation being more effective than early (Griesbach et al., 2004).

4.3.3. Haloperidol and environmental enrichment

Antipsychotic drugs are typically used to manage TBI-induced agitation so that patients can be evaluated and treated effectively (Lombard and Zafonte, 2005; Chew and Zafonte, 2009; McNett et al., 2012; Rao et al., 2015). However, HAL has been reported to negatively impact spatial learning after CCI and FP brain injury (Wilson et al., 2003; Kline et al., 2007a, 2008; Hoffman et al., 2008; Phelps et al., 2015). In contrast, EE enhances motor and cognitive function and confers neuroprotection (Kline et al., 2007b, 2010; 2102). Because management of agitation is necessary so that neurorehabilitation can be initiated and safely provided, Folweiler and colleagues (2016) set out to determine how the two therapeutic approaches influence functional recovery. Briefly, adult male rats received a CCI injury of moderate severity, or sham injury, and then were provided HAL (0.5 mg/kg; i.p.) or vehicle (1 mL/kg; i.p.) beginning 24 hr after surgery and once daily for 19 days while housed in EE or STD conditions. The data showed that the TBI groups receiving EE performed significantly better than those in STD-housing. Furthermore, the STD HAL group performed worse than the STD vehicle group. Given the protective effects previously reported by EE, it was surprising that HAL was able to reduce the EE-mediated benefits. The clinical relevance of these data is that administering HAL to reduce agitation may also reduce rehabilitative efficacy.

5. Neurotrophins

Neurotrophins are a family of peptides that hold great promise for the treatment of TBI. These include BDNF, glial cell derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), nerve growth factor (NGF), neurotrophin 3, and neurotrophin 4/5. In the healthy brain these peptides bind with high affinity to the tyrosine kinase (trk) receptors, including trkA, trkB, and trkC (Huang and Reichardt, 2001), and in doing so help regulate neural cell growth and survival by activating proteins in the cell cytoplasm and nucleus and altering gene expression (Kaplan and Miller, 2000). Neurotrophins also bind with low affinity to p75NTR receptors, members of the TNF family. Neurotrophins have been implicated in reducing neuronal and glial apoptosis, and in improving functional outcome after brain trauma (Nakata et al., 1993; Fisher et al., 1995; Dietrich et al., 1996; Dixon et al., 1997a; McDermott et al., 1997; Nemati and Kolb, 2011). However, the disruption of neurotrophin levels and variability in trk/p75NTR receptor concentrations, as well as the pathways by which neurotrophins act on target receptors can factor into TBI outcomes. Enhancing the levels and resulting actions of neurotrophins may be a viable therapeutic approach for treating the sequelae of TBI.

5.1. Positive effect

5.1.1. Fibroblast growth factor-2 and hypothermia

Given the numerous benefits reported with neurotrophic factors and hypothermia after TBI, Yan and colleagues (2000) sought to evaluate the effects of intravenous administration of fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2; 45 µg/kg/h for a total of 135 µg/kg) combined with moderate hypothermia (32° ± 0.5°C; commencing 10 min post TBI and a duration of 3 hr), or each alone in adult male rats subjected to a moderate CCI injury. The combination group performed significantly better on the beam-walk task relative to the individually treated FGF-2 and hypothermia groups, which did not differ from the vehicle-treated TBI controls. Spatial learning was improved in all treatment conditions compared to the normothermic vehicle-treated TBI controls, but the combination was not more efficacious than the individual treatments. Moreover, glial fibrillary acid protein expression was significantly attenuated in all treatment groups, but again the combination of treatments was not more effective. Lastly, no significant differences were appreciated among the groups in terms of beam-balance performance, hippocampal CA1,3cell survival, or cortical lesion volume. Overall, the effects of the combination treatment were both additive and neutral, but the lack of negative outcomes suggests that this therapeutic combination may be worth pursuing further with different timing and dosing strategies.

5.2. Neutral effect

5.2.1. Nerve growth factor and environmental enrichment

Following up on previous studies evaluating EE as one of the key therapies in the combination approach (Kline et al., 2007, 2010, 2012), Young et al. (2015) provided EE and NGF, alone and in combination, to adult male rats following a moderate CCI injury over the forelimb sensorimotor cortex. After surgery, the rats were randomized to groups receiving EE or STD housing and intranasal administration of NGF (0.1 mg/mL in phosphate buffered saline) or vehicle once every other day for 7 days post-injury. Sham animals were assigned to both housing conditions but did not receive NGF. Neurorehabilitation with EE led to significantly fewer placement errors in the foot fault test compared to the STD-housed NGF-treated group; the benefits were similar whether the rats received EE alone or combined with NGF, which suggests that EE was more beneficial than NGF, but also highlights the absence of an additive effect. No differences were found among the treatment groups in terms of remaining cortical tissue or hippocampal cell counts. The lack of an EE-induced benefit in histological outcomes is surprising given the robust protection reported by others in both male and female rats (Passineau et al., 2001; Maegele et al., 2005; Kline et al., 2007, 2010, 2012; Hoffman et al., 2008; Sozda et al., 2010; Monaco et al., 2013). Overall, the findings demonstrated a rehabilitative, but not NGF, effect.

5.2.2. Adenoviral glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor and L-arginine

The administration of adenoviral glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (AdGDNF) is another approach that has been used to recover symptoms of TBI. In an initial study, Minnich and co-workers (2010) injected AdGDNF unilaterally into the rat forelimb sensorimotor cortex one week prior to a CCI injury of moderate severity. The treatment reduced lesion volume and cell loss relative to untreated TBI controls, but did not fully restore symmetrical forelimb use. Postulating that the failure of AdGDNF in functional recovery may have been due to metabolic deficiencies in the injured parenchyma caused by impaired cerebral blood flow (CBF), DeGeorge and colleagues (2011) combined AdGDNF with L-arginine, which is known to enhance CBF after injury. Their goal was to provide greater metabolic homeostasis to help regulate protein synthesis, which is required in virally-mediated trophic factor expression (Lee et al., 1999) and is believed to play a role in the lack of success in the original experiment. Following a CCI injury of moderate severity to adult male rats, two doses of viral vectors of AdGDNF (2 × 107 plaque-forming units total via 2 µL injections) or green fluorescent protein were infused directly into the cortex 30 min post-injury at a rate of 0.5 µL per min. L-arginine (150 mg/kg) or vehicle was injected via the femoral vein immediately following AdGDNF administration. The data showed that the polytherapy group had significantly smaller lesions relative to the monotherapy groups and vehicle treated controls. No amelioration of behavioral deficits was observed regardless of treatment compared to vehicle (DeGeorge et al., 2011). Thus, the effect of the combination treatment is considered to be “neutral” based on our criteria and focus on behavioral endpoints.

5.3. Negative effect

5.3.1. Basic fibroblast growth factor and magnesium chloride

Unlike the study by Yan et al. (2000), where FGF-2 combined with hypothermia produced a significant benefit in motor function and neutral effects in other endpoints, the combination of FGF-2 (i.e., basic fibroblast growth factor, bFGF, 384 µg, i.v. infusion over 24-hr) and MgCl2 (125 µmol, 15 min i.v. infusion) in FP injured adult male rats resulted in a negative effect as bFGF negated the benefit of MgCl2 on the composite neuroscore on post-injury day-7 (Guluma et al., 1999). Specifically, no benefits were observed with any of the treatment groups at 48 h post-injury, but assessment on day-7 showed that the MgCl2 alone group conferred significantly improved motor function relative to the vehicle-treated TBI controls. bFGF had no effect when provided singly, but when combined with MgCl2 the benefits of MgCl2 were lost.

5.3.2. Vascular endothelial growth factor and fibroblast growth factor-2

Growth factors alone may be sufficient to stabilize the microenvironment of the injury parenchyma to a point where endogenous neurogenesis can flourish. To stimulate neurogenesis and angiogenesis simultaneously, Thau-Zuchman and colleagues (2012) administered FGF-2, VEGF, or their combination to adult male mice who sustained a moderate TBI via a weight-drop to the left frontoparietal cortex. An Alzet mini-osmotic pump was implanted into the right lateral ventricle for delivery of saline vehicle, VEGF (10 µg/mL), FGF-2 (2.5 µg/mL), or the combination of VEGF + FGF-2 (total dose of 0.84 µg of each treatment provided at a rate of 0.5 µL/hour over the course of 7 days), which was followed 3 days later by once daily injections of BrdU. VEGF, FGF-2, and the combination recovered neurological function significantly faster than the TBI vehicle controls. However, the neurological severity score was significantly better with VEGF alone relative to both FGF-2 and the combination. This finding suggests that the addition of FGF-2 resulted in a negative interaction and subsequently reduced the efficacy of VEGF. Regarding histological outcomes, both VEGF treatments lead to the expression of significantly more BrdU positive cells and more NeuN and Gal-C positive cells than treatment with vehicle, although they did not significantly differ from one another. VEGF, FGF-2, and their combination increased astrocytic differentiation compared to vehicle-treated TBI controls, but no significant differences were observed between the combination and individual therapy groups. Increased angiogenesis was observed in all treatment groups, but the largest increase was in the VEGF alone. Lastly, all treatment groups reduced lesion volume, but only the VEGF group reached statistical significance. That the combination group did not significantly decrease lesion volume as well suggests that adding FGF-2 to VEGF decreased the effectiveness of VEGF. These findings suggest that the combination was not more effective than either therapy alone in reducing neurological deficits, but actually negated the benefit of VEGF in improving neurological scores and in reducing the size of the lesion. It is possible that the growth factors together reached a ceiling effect, or perhaps due to shared action on tyrosine kinase receptors, the pathway became saturated such that a greater effect could not be achieved with the combination. Growth factors acting on different signaling receptors may work better in concert.

6. Stem cells

Many of the strategies discussed thus far have sought to provide neuroprotection by attenuating the pathophysiological events of secondary brain injury, which in turn reduce cell loss and functional deficits. An alternative strategy to preserving existing cells is to stimulate endogenous neurogenesis, which promotes regeneration of tissue. Though the vast majority of neurogenesis occurs during early development and tapers off with age, continuous neurogenesis occurs in the subventricular zone of the lateral ventricles and in the subgranular layer of the dentate gyrus throughout adulthood (Doetsch et al., 1999; van Praag et al., 2002). Cellular proliferation is increased in these regions following TBI in rodents (Chirumamilla et al., 2002; Bye et al., 2009) and it is believed that cells generated specifically in the subventricular zone may possess the ability to migrate to the injury parenchyma and merge into existing neural networks, enhancing the function of neurons in areas that would otherwise be disturbed after brain trauma (Richardson et al., 2009; Ng et al., 2012). Indeed, studies providing stem cells have shown positive results after TBI (Gao et al., 2006; Riess et al., 2007; Valle-Prieto and Conget, 2010; Zanier et al., 2011), but one prevailing issue preventing full integration of stem cells is the hostile microenvironment in the tissue surrounding the site of injury (Hernandez, 2006). Several combination therapies have been investigated that provide stem cells to be integrated into neuronal networks with the goal of improving function, and/or that work to alleviate the catastrophic secondary events occurring in injured tissue in order to make a more hospitable environment for newly integrating endogenous and exogenously transplanted neural cells.

6.1. Positive effect

6.1.1. Human umbilical cord blood cells and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor

Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) has been shown to enhance cognitive recovery, reduce inflammation, decrease amyloid protein expression, increase neurogenesis, and restore neural connectivity in experimental models of Alzheimer’s disease and stroke (Sanchez-Ramos et al., 2009; Cui et al., 2013). Hence, Acosta and colleagues (2014) intravenously administered human umbilical cord blood cells (hUCBCs; 4×106 viable cells) when combined with G-CSF (300 µg/kg in 500 µL sterile saline) 7 days after a moderate CCI injury in adult male rats to determine their efficacy in improving neuroprotection and attenuating neuroinflammatory responses. Behavioral assessments were conducted until day-56 post-TBI at which time tissue was collected for assessment of various molecular markers. While some benefits to functional outcome were conferred by hUCBC and G-CSF treatments individually, the combination treatment provided the greatest benefit. Neuroinflammation was significantly reduced by all treatment conditions vs. TBI controls, but the effect was more robust in the combination strategy. These findings suggest that the combination of hUCBCs and G-CSF is a strong therapeutic regimen, having synergistic effects on recovery of motor function and anti-inflammatory properties unrivaled by the individual treatments (Acosta et al., 2014).

6.1.2. Recombinant human erythropoietin and simvastatin

Recombinant human erythropoietin (rhEpo) is known for its anti-apoptotic, anti-edematous, and antioxidant properties after CNS injury (Byts and Siren, 2001; Chen et al., 2007; Öztürk et al., 2008; Xiong et al., 2010) and as previously discussed, statins attenuate secondary injury mechanisms such as inflammation, cerebral hypoperfusion, and ischemia after TBI (Weitz-Schmidt et al., 2001; McGirt et al., 2002). These drugs help to stabilize the tissue microenvironment, which may increase stem cell survival in the injured brain. Chauhan and Gatto (2010) combined these treatments to determine their effects on promoting cell proliferation and repairing axonal damage, as well as cognitive recovery. Specifically, adult male C57BL/6J mice were assigned to naïve, sham, or moderate CCI injury conditions and then randomized to receive rhEpo (5000 U/kg dissolved in 300 µL saline, i.p.), oral simvastatin (2 mg/kg), vehicle plus an isocaloric diet for 8 weeks, or combined rhEpo + simvastatin. Treatments were provided at 6 hr, 1 day, and 3 days post-injury. The behavioral data revealed beneficial effects of the treatments, whether provided alone or in combination, in spatial learning and working memory relative to the untreated TBI controls. While the authors report additive effects for all assessments with the combination strategy, it appears that an additive effect was only observed in the spatial learning task where the combined treatment group reached the level of the sham controls. However, there was a clear additive effect in cell proliferation and axonal integrity based on the significant increase in bromdeoxyuridine (BrdU) positive cells and SMI 312 immunoreactivity, respectively, in the combination group vs. the individual treatment groups. Each treatment also increased BrdU positive cells relative to the TBI controls. Taken together, these findings suggest that the combination paradigm is more effective than individual treatments in spatial learning, cell proliferation, and protecting against axonal degeneration.

6.1.3. Marrow stromal cells and atorvastatin

In combination with stem cells, statins may induce the production of growth factors in injured tissue and enhance neurogenesis (Chen et al., 2005; Mahmood et al., 2004; Lu et al., 2004). Mahmood and colleagues (2007) evaluated the effects of transplanted adult male rat bone marrow stromal cells (MSCs; 1 × 106, i.v., 24 h post-injury) and atorvastatin (0.5 mg/kg, p.o. 24 h post-injury for 14 days), both alone and in combination, on functional outcome and access/survival of MSCs in the brains of female rats after a moderate CCI injury. No significant improvements in neurological severity scores or cognitive performance were revealed in the monotherapy groups. However, both functional outcome measures were significantly improved in the polytherapy group. Significantly more MSCs were found in brain tissue of the combination group vs. MSC treatment alone. Also, significantly more endogenous cell proliferation and vascular density was seen in the hippocampus and injury boundary zone in the combination therapy group compared to the monotherapy groups and injured controls, indicating that the combination treatment increased the number of newly generated cells and stimulated angiogenesis. Thus, the combination of MSCs plus atorvastatin is more effective than either therapy alone (Mahmood et al., 2007).

6.1.4. Marrow stromal cells and simvastatin

A subsequent study by the same group looked at the effects of MSCs (doses of 1 × 106 or 2 × 106 i.v., 7 days post-injury) and simvastatin (0.5 mg/kg or 1.0 mg/kg, p.o., starting 24 h post-injury for 14 days thereafter), alone and in combination, on functional outcome in female rats after a moderate CCI. The data showed that both doses of MSCs and simvastatin, as well as all combinations, significantly improved neurological severity scores vs. TBI controls. However, the lower dose of simvastatin combined with the higher dose of MSCs revealed a synergistic effect vs. all monotherapies in improving outcome. Donor MSCs were detected in the lesion boundary zone, as well as in other areas of the ipsilateral and contralateral cortex, in rats that received either single or combined MSCs, with no differences between groups. Endogenous cell proliferation in the injury boundary area was increased in all treatment groups vs. non-treated TBI controls, and no significant differences were found among the combination groups and MSCs alone. Like the previous study by this group (Mahmood et al., 2007) MSCs and simvastatin appear to exert a synergistic effect on functional outcome after CCI injury in female rats (Mahmood et al., 2008).

6.1.5. Pluripotent stem cells and environmental enrichment

The use of stem cells in combination with rehabilitation is a relatively new innovation in TBI, but has gained traction as a strategy for treating TBI-induced deficits. To this end, Dunkerson and colleagues (2014) evaluated this combination paradigm in adult male rats subjected to a bilateral CCI injury of moderate severity. Induced pluripotent stem cells were transplanted 7 days post-surgery while the rats were receiving EE. Motor coordination and cognitive performance were evaluated following single therapy or combination and compared to media-treated TBI controls. All groups exposed to EE produced benefits in motor performance relative to the media plus STD-housed controls. No benefit was revealed in the water maze cognitive task with the monotherapies, but the combination group exhibited performance at near sham levels.

6.1.6. Cortical embryonic stem cells, progesterone, and environmental enrichment

In perhaps one of the most polytherapy-oriented studies to date, Nudi and colleagues (2014) sought to assess the effects of PROG (10 mg/kg; i.p., 4 hr post-injury and every 12 hr thereafter for 72), cortical embryonic stem cells (eSCs; ~100,000 in 2.5 µL of media i.v., 7 days post-injury), and EE alone or in two and three therapy combinations on functional outcome, lesion volume, and hippocampal cell preservation, as well as on the survival and differentiation of eSCs in the brain after a CCI injury of moderate severity in adult male rats. The experimental design was complicated, and the statistical analyses may not have been sufficiently stringent for the multiple comparisons, but the general consensus that emerged from the study was that all therapies produced significant benefit over the untreated vehicle controls. Moreover, the combination therapies were more efficacious than monotherapies and the addition of EE further promoted benefits in some endpoint assessments. These data lend further support for rehabilitation as a critical player in recovery from TBI.

6.2. Neutral effect

6.2.1. Embryonic stem cells and environmental enrichment

Continuing with the research paradigm investigating rehabilitation combined with stem cell implantation for treating TBI-induced deficits, Peruzzaro and colleagues (2013) provided murine cortical eSCs alone or in combination with EE and assessed on motor and cognitive outcome following bilateral prefrontal CCI injury of moderate severity in male rats. EE was initiated immediately after TBI and continued for over a month. eSCs or media were implanted 1 week post-injury, such that rats were exposed to EE both before and following transplantation. While the combination of eSCs and EE led to performance approaching sham control levels, suggesting that a certain degree of neuroprotection was achieved, there were no statistical differences in any endpoint measure relative to the monotherapies. No stringent quantitative analyses for eSC survival, migration, and differentiation into neural or glial cells were performed, hence the direct functional relevance of eSC implantation combined with EE remains to be elucidated.

7. Discussion

The review focused on studies that included some form of behavioral outcome, regardless of how modest. The reasoning for this decision was that the ultimate goal of any therapy is to positively influence behaviors (i.e., neurobehavioral or cognitive outcome) that will benefit TBI patients and facilitate their independence and integration into society. However, the paucity of behavioral assessments is concerning. In reviewing the papers that fit the criteria for a combination study, only the 37 reviewed here included at least one behavioral outcome measure, while 22 focused exclusively on cell signaling, histological, and physiological changes. We acknowledge that it is important to determine how potentially efficacious therapies, alone or in combination, affect these non-behavioral symptoms as this line of research is valuable for drug design and development and may eventually lead to new therapies for attenuating many of the secondary sequelae of TBI and ameliorating functional outcome.

Stringent criteria for defining a combination study were adhered. Specifically, to be considered a true combinational paradigm, each study was required to include the effects of not only the combination, but each individual therapy. Investigating a combination without simultaneously assessing the effects of each monotherapy can give the false impression that a combination is superior to a single treatment, when in reality similar or only slightly different effects may be imparted. Studies by Kline and colleagues saliently highlight this important point as they have shown positive interactions with the 5-HT1A receptor agonists 8-OH-DPAT and buspirone (Kline et al., 2007, 2010, 2012) as well as the D2 receptor agonist methylphenidate (Leary et al., 2016) when paired with EE, a preclinical model of neurorehabilitation. However, even though the combination groups performed significantly better than the individual pharmacotherapies, the polytherapy effects were not statistically different from EE alone. Had the studies not been properly designed and executed to also evaluate the efficacy of EE individually, one would certainly, but mistakenly, conclude that the combination was better. Ensuring that all the proper groups are included inevitably adds a degree of complexity to combination treatment studies, yet it is crucial for making correct interpretations and therapeutic advances. Unfortunately, over a dozen papers, in which the authors reported better effects with the combination, were omitted from this review because the study design did not allow for assessment of both individual therapies.

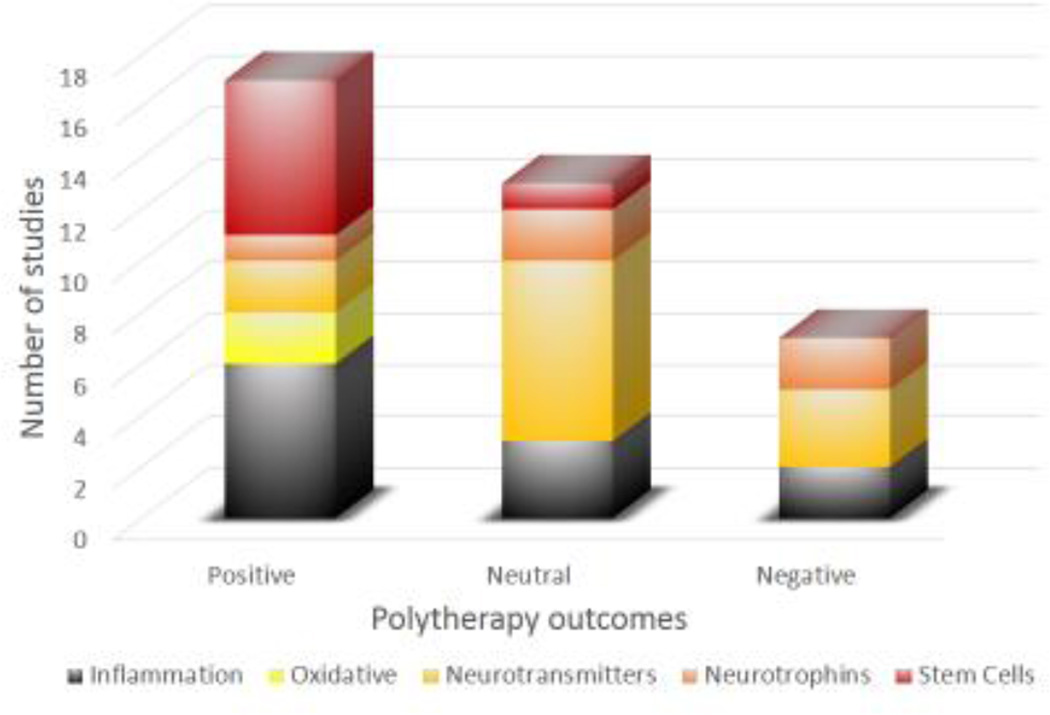

Overall, the findings suggest that the answer to the question “is more better?” when referring to polytherapy versus monotherapy paradigms for improving neurobehavioral and cognitive function after experimental TBI is an optimistic, but cautious “yes” as 17 (46%) of the studies exhibited an additive or synergistic positive effect versus 13 (35%) revealing a neutral outcome, and only 7 (19%) reporting a negative interaction. These encouraging findings serve as an impetus for continued combination studies after TBI and ultimately for the development of successful clinically relevant therapies. Indeed, polytherapy has been the norm for cancer and AIDs research and treatment for several years (Li et al., 2014; Henkle, 1999).