Abstract

Introduction

Skin cancer is the most common cancer, and its incidence is increasing. Young adults expose themselves to large amounts of ultraviolet radiation (UV) and engage in minimal skin protection, which increases their risk. Internet interventions are effective in modifying health behaviors and are highly disseminable. The current study's purpose was to test an Internet intervention to decrease UV exposure and increase skin protection behavior among young adults.

Study design

RCT conducted in 2014, with data analyzed in 2015.

Setting/participants

A national sample of adults aged 18–25 years at moderate to high risk of developing skin cancer by a self-report measure was recruited online.

Intervention

Participants were randomized to one of three intervention conditions: assessment only, the website of a skin cancer organization, or a tailored interactive multimedia internet intervention program (UV4.me) based on the Integrative Model of Behavioral Prediction.

Main outcome measures

Self-reported overall UV exposure and skin protection assessed at 3 and 12 weeks after baseline. Secondary outcomes were self-reported intentional and incidental UV exposure, sunburns, sunscreen use, and skin cancer screening.

Results

For the intervention arm, there were significant decreases in UV exposure and increases in skin protection at both follow-up time points compared with the assessment-only condition (p<0.001). The effect sizes (Cohen's d) comparing the experimental and assessment-only arm for exposure behaviors were 0.41 at 3-week follow-up and 0.43 at 12-week follow-up. The effect sizes for protection behaviors were 0.41 at 3-week follow-up and 0.53 at 12-week follow-up. The control condition was not significantly different from the assessment only condition. All three conditions exhibited decreased exposure and increased protection at both follow-ups (p<0.01), but the effect was much stronger in the intervention group. Secondary outcomes were generally also significantly improved in the intervention condition compared with the other conditions.

Conclusions

This is the first published report describing the results of an RCT of an Internet intervention to modify skin cancer risk behaviors among young adults. The UV4.me intervention significantly improved self-reported skin cancer prevention behaviors. Future research will investigate mechanisms of change and approaches for dissemination.

Introduction

Skin cancer is the most common cancer, with nearly five million diagnoses annually in the U.S., and its incidence has been increasing in recent years.1–5 Invasive melanoma is the second most diagnosed cancer among young adults.6 Contributing to increased skin cancer risk among young adults is the fact that U.S. adolescents have had the lowest skin protection rates of all age groups7 and also engage in increased exposure to ultraviolet radiation (UV) as they move into adulthood.8

For these reasons, it is important to have available interventions that are effective in addressing skin cancer risk behaviors among young adults. Although a few such interventions exist,9 most of these intervention studies have been conducted locally often with college (more often female) students only, have required an in-person component, and the length of follow-up has been short. Additionally, no reports on Internet interventions for skin cancer prevention among this population have been published previously. However, with approximately 97% of U.S. young adults using the Internet,10 and the evidence for the efficacy of Internet interventions,11 the Internet is an ideal mechanism with which to reach young adults and explore the efficacy of a skin cancer prevention intervention for this population.

The web-based intervention that was designed to modify skin cancer risk and protective behaviors among young adults was informed by the Integrative Model for Behavioral Prediction (IM).12 Constructs from the IM are associated with skin cancer risk and protective behaviors and include demographics, past UV-related behavior, attitudes such as appearance consciousness,13,14 other individual difference variables (e.g., knowledge and risk perception), UV-related beliefs,15– 22 norms and compliance,13,23 self-efficacy and control,24–29 and intentions,28 though the authors' group is the only one that has applied the overall model to the skin cancer domain. Individually tailored and interactive messages and material focusing on IM constructs such as norms and self-efficacy were featured in the web-based intervention. The tailored intervention emphasized appearance concerns, which are known to be the primary motivation for UV exposure and lack of skin protection among young adults. This was accomplished in part through the use of facial images showing UV damage as well as computerized age progression demonstrations.30–33

The purpose of the study was to test the efficacy of the web-based intervention to decrease UV exposure and increase skin protection behaviors among young adults at moderate to high risk of developing skin cancer in an RCT. It was hypothesized that participants randomized to the experimental intervention would report significantly less exposure and more protection than participants in other conditions at follow-up. Unlike prior research, this study was conducted with a large national sample.

Methods

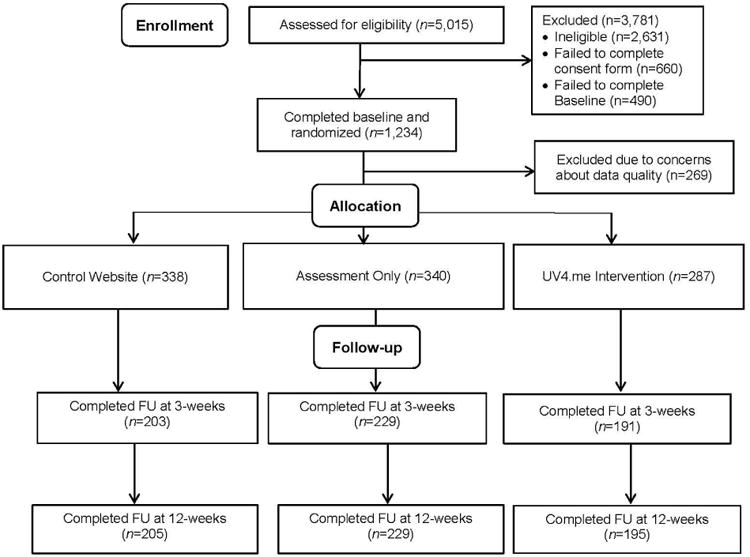

Participants were recruited online by Survey Sampling International using their U.S. consumer opinion panel and partnerships with other panels and online communities. Survey Sampling International panelists were exposed to brief web banner ads about the study from which they could click to link to the study website. Once at the study website, interested candidates were asked to complete the Brief Skin Cancer Risk Assessment Tool (BRAT),34 which was scored automatically. Skin cancer risk items include sun sensitivity, sunburn history, number of moles/freckles, and climate of childhood residence. Items are weighted, resulting in a 0–78 score. The BRAT authors recommend a cut off of ≥27 to denote moderate to high skin cancer risk. Internal and test–retest reliability compare favorably to those reported in the literature for similar items/scales (BRAT).34 Eligible participants were adults aged 18–25 years, had never had skin cancer, and were at moderate to high risk of developing skin cancer based on the BRAT. Approximately 47% of the 5,015 individuals who submitted a screening form met these eligibility criteria. Figure 1 shows the CONSORT study flow diagram.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram.

FU, follow-up

This project was approved and monitored by Fox Chase Cancer Center's IRB, and informed consent was obtained from research participants. Eligible participants were directed to the online informed consent form, which participants signed using a computer mouse. Participants were then directed to the baseline survey. Participants were subsequently randomized to one of three treatment conditions in blocks of nine or 12: assessment only, a control website, and the intervention website (described below).

In order to intervene with participants prior to summer, participants completed assessments at baseline in the spring (March to June, 2014), 3 weeks after baseline (April to July, 2014), and 12 weeks after baseline (June to October, 2014). Of the participants who completed baseline assessments, approximately 71% completed the first follow-up survey, and approximately 72% completed the second follow-up. Participants received an Amazon e-giftcard after each questionnaire: $10 for baseline, $20 for 3-week follow-up, $50 for 12-week follow-up, plus $20 for completing all three assessments.

Intervention Conditions

This trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier, NCT02147080). The experimental website (UV4.me) was targeted to young adults, personally tailored, and included interactive, multimedia, and goal-setting components. The control website was the Skin Cancer Foundation (SCF) website (www.skincancer.org). According to the SCF website, the SCF “is the only international organization devoted solely to education, prevention, early detection, and prompt treatment of” skin cancer. The SCF website was chosen because it is a high-quality multimedia website on the topic of skin cancer; however, no prior study has reported on its potential impact on behavior. Major topics include skin cancer information, prevention, true stories, healthy lifestyle (e.g., sports, anti-aging, vitamin D), news, and getting involved, among others. Participants were sent automated e-mail reminders to enter the control website and to begin and engage with UV4.me (e.g., set and work on goals).

The UV4.me Intervention

Based on a synthesis of prior formative individual interviews and focus groups with the target population, the authors' expertise, and the literature,35–37 a multidisciplinary team collaborated to create the design, modules, and other activities to be included in the web program. The intervention was intended to be interactive, tailored, utilize multiple media formats (text, audio/video, images), and maximize participant engagement. Twelve modules were created, with topics determined to be important in terms of risk or protective behaviors:

Why do people tan?

To tan or not to tan?

Indoor tanning.

UV & health.

Skin cancer.

UV & looks.

Skin damage.

Shade.

Clothes.

Sunscreen.

Sunless tanning.

Skin exams.

Constructs from the IM12 were incorporated throughout the modules. For example, the indoor tanning module provided data showing that most young adults do not indoor tan in order to attempt to influence normative beliefs about indoor tanning. In addition, several other more general website sections (e.g., avatar, MyStuff—a printable summary of tailored goals and recommendations) were developed. Each module was expected to take about 10 minutes to review, and an attempt was made to have each module stand alone and be as focused as possible on encouraging behavior change.

Tailoring algorithms were created to direct participants to prioritize certain modules based on their responses to a few questions administered during the baseline questionnaire (e.g., the indoor tanning module was recommended if participants said they tanned indoors). Tailoring also occurred throughout the web program. For example, participants were asked questions (e.g., Who tans in your circle?) and were provided with feedback (You said that no one in your circle tans. You're in good company!). A number of interactive elements were created to increase engagement in the web program and successful behavioral outcomes. For example, at the end of each module was a goal-setting section (Locke and Latham38 provide a review of goal setting theory and research) in which participants could choose to set a pre-specified goal for the next 2 weeks or not (e.g., For the next two weeks, I will not use a tanning bed, booth, or sunlamp.). More detail about the development, content, and pre-testing of the intervention is provided in another paper (Heckman, et al., Internet Interventions, in press).

Measures

Demographic variables included age, sex, race, ethnicity, skin color, family history of skin cancer, education, employment status, ability to live on income, and receipt of public assistance.

The following sun protection behaviors were assessed, using a seven-item scale adapted from Glanz and colleagues42: wearing sunscreen with a sun protection factor (SPF) of ≥15 on the face, wearing sunscreen with an SPF of ≥15 on other parts of the body, wearing a shirt with sleeves that cover the shoulders, wearing long pants, wearing a hat, wearing sunglasses, and staying in the shade. Participants indicated how often they engaged in these behaviors over the past month (1=never, 5=always). This measure was internally consistent (α=0.76).

In addition, participants were asked to indicate how often they engaged in five UV exposure behaviors (wearing clothes that expose the skin to the sun, sunbathing, getting a tan just by being outdoors [i.e., unintentional tanning], tanning indoors, and using products to get a faster or deeper tan) over the past month (1=never; 5=always), using a five-item scale adapted by Ingledew et al.43 This measure had acceptable internal consistency (α=0.74).

For secondary outcomes, individual items were used. Because these data were skewed, responses were dichotomized. For sunburns, participants were asked to indicate how many times in the past month that they had a red or painful sunburn that lasted a day or more, an item adapted from Glanz and colleagues.42 Responses were dichotomized into those who reported being sunburned in the past month versus those who did not. In addition to including indoor tanning in the overall UV exposure scale, indoor tanning was also examined independently. Participants were asked to indicate the number of days in the past month that they used a tanning bed or booth, using an item adapted from Lazovich et al.44 Responses were dichotomized into those who reported tanning indoors in the past month versus those who did not. Participants were also asked to report how many hours per week in the past month they spent in the sun trying to get a tan (i.e., sunbathing) and not trying to get a tan (e.g., working, recreational activities). Responses were categorized: 0 hours, 1–4 hours, and ≥5 hours for intentional sun exposure and 0 hours, 1–4 hours, 5–10 hours, and ≥10 hours for incidental sun exposure.

Participants were asked about the SPF of the sunscreen they used most often in the past month with response options of didn't use sunscreen, <15, 15–30, >30, and I'm not sure/I don't know. Responses were dichotomized into SPF <15 versus SPF ≥15. In terms of skin cancer screening, participants were asked whether they, a partner, or a healthcare provider had checked their whole body for skin cancer using items adapted from Glanz and colleagues.42 Response options were yes and no.

Statistical Analyses

Prior to conducting outcome analyses, quality metrics derived from the baseline questionnaire were evaluated using methods described by Meade and Craig.45 The metrics selected to indicate potential poor quality responses were:

unusually short or long baseline questionnaire completion time;

unusually long or short strings of identical consecutive responses;

low within-subject correlation for items with the strongest positive correlations across all subjects (i.e., synonyms);

unusually high or low within-subject correlations for even and odd numbered items within subscales; and

unusually high or low Euclidean distance from subjects' responses to the mean response on each item.

Responses were also “flagged” as indicating potential poor quality for issues such as providing a non-unique or non-working e-mail address or phone number.46

Based on interactions with participants during the course of the study, several participants with unusually similar responses on the screener questionnaire were identified who may have been either affiliated with one another through a participant-initiated Facebook post or who had enrolled in the study more than once. Hierarchical clustering was used to determine membership in this affiliated group based on the Euclidean distance matrix of responses to each screener question.47,48 A cluster of individuals was identified and are referred to as “similar screeners.”

Polytomous Variable Latent Class Analysis Version 1.42013 was used to identify groups of subjects with similar distributions of quality metrics.49 Included were all quality metrics from the baseline questionnaire, other flagged responses, and classification as a similar screener. Based on characteristics of the fitted class memberships, classes representing lower-quality responders were determined. Overall, low-quality respondents (n=269) had a greater number of “hits” on the low quality metrics.

The final sample (N=965) consisted of participants with predicted membership in the high-quality latent class. Demographics were examined to determine whether randomization was successful using chi-square tests and ANOVA. All outcomes were analyzed using generalized linear regression models. The primary outcomes of UV exposure and skin protection behaviors were analyzed as continuous variables, using linear regression. Additionally, categories for intentional and incidental UV exposure were created based on hours of reported exposure per week, and multinomial logistic regression was used to determine the effects of the intervention. Other secondary outcomes were dichotomized, and logistic regression was used to model these outcomes. All models contained intervention condition, time (categorized as baseline, 3 weeks post baseline, and 12 weeks post baseline), and the interaction between intervention and time. Generalized estimating equations50 were used for all regressions to account for within-individual correlation. For the exposure and protection outcomes at 12-week follow-up, moderation by sex and age were assessed using a linear regression, with an interaction between treatment and each of the moderating variables. Likelihood ratio tests were used to determine whether the overall interaction between each moderator and treatment was statistically significant.

The reported analyses used all observed data from the high-quality sample. To determine potential biases due to selective drop-out, another analysis of the primary outcomes was conducted with the last observation carried forward to fill in missing data. This gives a conservative estimate of the intervention effect, as it assumes no improvement in any participants who did not complete the 3- or 12-week follow-up questionnaire, which can be interpreted as a lower bound on the true intervention effects. To determine the effect of removing low-quality screeners, a sensitivity analysis was conducted in which all participants who completed the baseline questionnaire were included, regardless of quality.

Results

No demographic covariates were significantly different between the three intervention conditions, indicating successful randomization (Table 1). Demographic characteristics of the high-quality sample are shown in Table 1, and descriptive data for the outcomes at each time point are shown in Table 2. On average, the 84% of those randomized to the control website who accessed it visited the control website twice (2.1 [1.7]), whereas the 70.4% of experimental condition participants who accessed the intervention website visited it more than five times (5.8 [5.0]), completing almost half (5.7 [5.0]) of the available 12 modules.

Table 1. Baseline Demographic Characteristics by Intervention Condition (N=965).

| Variable n (%) | Overall | Assessment only (n=340) | Control (n=338) | Experimental (n=287) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age [Mean (SD)] | 21.8 (2.2) | 21.9 (2.2) | 21.7 (2.2) | 21.8 (2.2) | 0.498 |

| Female Sex | 637 (66.1) | 224 (65.9) | 216 (64.1) | 197 (68.6) | 0.487 |

| White | 825 (85.7) | 297 (87.6) | 283 (84.0) | 245 (85.4) | 0.397 |

| Hispanic | 92 (9.6) | 30 (8.9) | 31 (9.3) | 31 (10.9) | 0.668 |

| Fair skin color | 833 (86.3) | 288 (84.7) | 301 (89.1) | 244 (85.0) | 0.192 |

| Family history of skin cancer | 339 (35.2) | 110 (32.4) | 127 (37.7) | 102 (35.5) | 0.344 |

| College graduate | 213 (22.1) | 71 (20.9) | 76 (22.6) | 66 (23.0) | 0.792 |

| Working >full-time | 175 (18.1) | 62 (18.2) | 58 (17.2) | 55 (19.2) | 0.819 |

| Hard to live on income | 314 (32.5) | 114 (34.9) | 113 (34.3) | 87 (31.4) | 0.634 |

| Receives public assistance | 173 (18.8) | 62 (18.6) | 62 (19.1) | 49 (18.1) | 0.953 |

| Northern U.S. | 640 (66.3) | 227 (66.8) | 232 (68.8) | 181 (63.1) | 0.497 |

Table 2. Descriptive Data for the Outcome Variables.

| Variable | Baseline (n=965) |

3-week follow-up (n=623) |

12-week follow-up (n=629)a |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| M (SD) | Assessm ent only (n=337)b |

Contr ol (n=33 6) |

Experime ntal (n=286) |

Assessm ent only (n=229) |

Contr ol (n=20 3) |

Experime ntal (n=191) |

Assessm ent only (n=229) |

Contr ol (n=20 5) |

Experime ntal (n=195) |

| Overall UV exposure | 1.49 (0.80) | 1.50 (0.79) | 1.44 (0.80) | 1.34 (0.81) | 1.35 (0.75) | 1.02 (0.76) | 1.21 (0.73) | 1.19 (0.70) | 0.89 (0.73) |

| Skin protection | 1.95 (0.77) | 1.83 (0.81) | 1.94 (0.81) | 2.09 (0.87) | 2.00 (0.84) | 2.45 (0.88) | 2.17 (0.87) | 2.17 (0.84) | 2.64 (0.89) |

|

| |||||||||

| N (%) | |||||||||

| Sunburn | 191 (56.3) | 172 (51.5) | 156 (54.5) | 116 (50.9) | 91 (44.8) | 62 (32.6) | 94 (41.2) | 78 (38.2) | 51 (26.3) |

| Indoor tanning | 30 (8.9) | 31 (9.3) | 26 (9.1) | 19 (8.3) | 17 (8.3) | 8 (4.2) | 17 (7.4) | 12 (5.9) | 8 (4.1) |

| No incidental UV | 84 (25.1) | 80 (24.0) | 78 (27.6) | 38 (16.8) | 27 (13.4) | 46 (24.6) | 38 (16.9) | 43 (21.3) | 60 (31.1) |

| No intentional UV | 265 (78.2) | 254 (75.4) | 212 (74.1) | 176 (77.2) | 153 (75.0) | 160 (83.8) | 186 (81.6) | 163 (80.3) | 175 (90.7) |

| SPF of 15 or higher | 187 (55.0) | 164 (48.5) | 143 (49.8) | 150 (65.5) | 131 (64.2) | 140 (73.3) | 161 (70.3) | 156 (76.1) | 162 (83.1) |

| Clinician screening | 54 (15.9) | 61 (18.2) | 45 (15.7) | 52 (22.7) | 41 (20.1) | 47 (24.6) | 56 (24.5) | 53 (25.9) | 69 (35.4) |

| Self-screening | 43 (12.6) | 48 (14.3) | 36 (12.5) | 59 (25.8) | 38 (18.6) | 63 (33.0) | 59 (25.8) | 48 (23.4) | 87 (44.6) |

Participants who did not complete the 3-week follow-up were still permitted to complete the 12-week follow-up.

Note that n = the total possible sample size for each intervention group at each time-point, though the sample size for any specific outcome variable may have been slightly less due to missing data.

The main results of interest in the regression models were whether the effects of the intervention and control arms were different from the assessment-only arm at 3- and 12-week follow-up. For the intervention arm, significant decreases in exposure behaviors and significant increases in protection behaviors were found at both 3 and 12 weeks when compared with the assessment-only arm (p<0.001, Table 3). The effect sizes (Cohen's d) comparing the experimental and assessment-only arm for exposure behaviors were 0.41 at 3-week follow-up and 0.43 at 12-week follow-up. The effect sizes for protection behaviors were 0.41 at 3-week follow-up and 0.53 at 12-week follow-up. The control arm was not significantly different from the assessment-only arm at follow-ups. All three arms exhibited decreased exposure and increased protection at 3 and 12 weeks (p<0.01), but the effect was much stronger in the intervention group (results not shown). The intervention effects were somewhat attenuated when using the last observation carried forward method for missing data or when all participants, regardless of quality assessment, were included; however, effect direction and statistical significance was maintained in all analyses (results not shown). Significant moderator effects of sex and age were not identified (results not shown).

Table 3. Generalized Estimating Equation Analyses for Primary Outcomes.

| Overall UV exposure (N=962) | Skin protection (N=894) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Effecta | SE | p-value | Effecta | SE | p-value | |

| Baseline | ||||||

| Assessment only | ref | - | - | ref | - | - |

| Control | 0.014 | 0.061 | 0.822 | -0.127 | 0.064 | 0.047 |

| Experimental | -0.051 | 0.064 | 0.423 | -0.017 | 0.069 | 0.804 |

|

| ||||||

| 3 weeks | ||||||

| Assessment only | ref | - | - | ref | - | - |

| Control | 0.012 | 0.069 | 0.864 | -0.108 | 0.082 | 0.186 |

| Experimental | -0.293 | 0.071 | <0.001 | 0.349 | 0.086 | <0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| 12 weeks | ||||||

| Assessment only | ref | - | - | ref | - | - |

| Control | -0.034 | 0.067 | 0.609 | -0.024 | 0.083 | 0.773 |

| Experimental | -0.300 | 0.070 | <0.001 | 0.429 | 0.090 | <0.001 |

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05).

Treatment effects at each time point compared with assessment only condition.

For the secondary outcomes, all groups were less likely to report any sunburns (p<0.001) and to report ≥5 hours of intentional sun exposure (p=0.05) at 12-week follow-up. All groups were more likely to report use of SPF of ≥15 (all p<0.001), to report having completed a clinician skin cancer screening (all p<0.01), as well as completing a self or partner-assisted skin cancer screening (all p<0.001) at 3- and 12-week follow-up.

In terms of intervention effects on secondary outcomes, intervention participants were less likely than assessment-only participants to report sunburns at either 3- or 12-week follow-up (p=0.003 and p=0.014, respectively) or 1–4 hours of intentional sun exposure at 12 weeks than assessment-only subjects (p=0.002). Intervention participants were more likely than assessment-only participants to report clinician screening at 12-week follow-up (p=0.035) as well as self-screening (p=0.003). The control group did not differ from the assessment only group on any of these secondary outcomes (results not shown).

Finally, intervention participants were more likely than assessment-only participants to report higher SPF use at either 3- or 12-week follow-up (p=0.015 and p<0.001, respectively), as were control participants at 12-week follow-up (p=0.019). Intervention participants were less likely to report 5–10 or ≥10 hours of incidental sun exposure at 12 weeks than the assessment group (p=0.018 and p=0.016, respectively), but there was no decrease in 1–4 hours of incidental UV exposure (results not shown). There were no significant differences over time or by treatment condition for the number of days spent indoor tanning in the past month.

Discussion

To the authors' knowledge, this is the first published report on the efficacy of a web-based prevention intervention to modify skin cancer risk behaviors among at-risk young adults from a national RCT. Participants in the tailored, multimedia, interactive Internet intervention (UV4.me) improved their self-reported UV exposure and protection behaviors significantly more than they would have otherwise. The effect sizes for the primary outcomes of 0.41–0.53 were in the small to medium range according to Cohen's criteria.51 Though the experimental group decreased their indoor tanning by more than 50%, there was not enough power for this result to be significant due to the small number of individuals who had tanned indoors in the last month at baseline, approximately 9%. These findings are important because UV exposure is a definitive skin cancer risk factor, and skin protection can help prevent skin cancer.3,52-58

Upon closer examination of some of the behaviors, the experimental group reduced both their intentional and incidental exposure more than the other groups. Both the experimental and control group were more likely to report using higher SPF sunscreen than the assessment-only group. This suggests that a generic website not necessarily intended to change specific behaviors may be successful in doing so in some cases. Additionally, the experimental group was more likely to report both clinician and self skin cancer screening than the other groups.

Interestingly, participant behavior also improved in the control condition and the assessment-only condition, though less than in the experimental condition. This is notable given that one might have expected behavior to worsen during the summer. It is unknown whether the improvement reported in the non-experimental groups was due to potential increased awareness, behavior tracking, attrition by less motivated participants, social desirability, or other factors related to longitudinal “panel conditioning.”59,60 Though the assessments were not intended to serve as an intervention, participants from each condition commented that they found the questionnaires “fun,” “thorough,” “interesting,” or “informative.” Some prior skin cancer prevention studies have found knowledge and behavior to be unrelated or demonstrated minimal short-term effects of increased awareness and knowledge.61-65 Thus, it would be interesting to see whether the changes in the non-experimental groups would have decreased over a longer time period. Many studies have demonstrated behavioral tracking to be an effective behavior change intervention, though none have been reported in the area of skin cancer prevention.66-69 Participants who were less interested in or motivated by the topic may not have completed the follow-up questionnaires, resulting in the appearance of a certain amount of behavioral improvement across all groups, although improvements for all groups were maintained based on the last observation carried forward method. Finally, though prior studies have found self-report of UV exposure and protection to be reliable and valid,39–41 future intervention researchers may want to include a measure of social desirability.

Next steps for this line of research will be to investigate additional moderators, mediators, and mechanisms of intervention effects as well as dissemination and enhancement strategies. It will be useful to learn whether certain subgroups of individuals are more or less impacted by the intervention based on demographic characteristics such as skin color, past behavior (e.g., having indoor tanned or not), or traits such as concern about appearance. Though several participants commented that the intervention seemed to be designed primarily for women or adolescents, and women and older participants were more likely to complete the study assessments, intervention effects were not moderated by sex or age. Similarly, it will be important to know which constructs from the IM (e.g., norms, self-efficacy) change with intervention and whether certain modules or components of the intervention are more or less impactful than others. Additionally, a dissemination trial should investigate strategies for engaging at-risk young adults with the intervention without the help of a market research company and unsustainable incentives such as by using Google, Facebook, and snowball sampling. Finally, the intervention could be enhanced to facilitate reach and engagement through the use of a mobile version and social media/networking. Although intervention engagement seemed relatively strong compared with other Internet intervention trials,70-75 16% of control participants and 30% of experimental participants did not access the interventions. Among participants in the experimental condition, only about half of the modules were viewed/completed. Innovative techniques and strategies will need to be added to future versions to address matters of adherence. In addition, a longer follow-up period should be employed to better understand issues of long-term behavior change and maintenance.

Limitations

The strengths of the study include a focus on an important public health issue, an RCT design, a theoretically informed intervention, and participation of a large national sample. The study also has several limitations. First, in order to enhance efficiency and geographic diversity, a commercial research panel was used for recruitment rather than other more-traditional methods. However, two large studies have demonstrated similar demographic characteristics and long-term follow-up rates comparing multinational consumer panels and traditional national surveys.76,77 Participants were disproportionately female. This may be because women were more interested in this study or because they were more likely to be eligible owing to their risk behaviors. Second, data quality procedures are necessary for online studies including incentives.45,46 Thus, not all of the data collected for the current study was deemed high quality and able to be included in the outcome analyses. However, though including only high-quality data attenuated the effects somewhat, this did not change the direction or statistical significance of the effects. Third, the SCF website front page is updated regularly with news stories, thus potentially changing the nature of the control condition during the course of the study. However, the study was completed within a period of about 6 months; thus, it is likely that few major changes were made to the website during this time period that would have significantly altered its impact. Fourth, self-report methods were used for outcome assessments. However, several studies have been conducted demonstrating the reliability and validity of self-report questionnaires of UV exposure and protection compared to observation and objective measures with no systematic bias identified among various populations.39,41,78-80

Conclusions

The UV4.me intervention was found to be successful in increasing skin protection and decreasing UV exposure and sunburns, which are known to be associated with skin cancer and its prevention. Future studies designed to modify behaviors associated with skin cancer development will investigate moderators, mediators, and mechanisms of intervention effects as well as dissemination and enhancement strategies.

Acknowledgments

This trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier, NCT02147080). This work was funded by R01CA154928 (CH), T32CA009035 (SD), and P30CA006927 (Cancer Center Support Grant). The study sponsor had no role in study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication. We thank the following for their assistance with this project: Carolyn Caruso, Mary Grove, Peter Braswell, and Gabe Heath from the staff of BeHealth Solutions, Inc. for creating the website and online assessment and data management system, Teja Munshi for her assistance with intervention development and data management, Stephanie Raivitch for her assistance with intervention and assessment development, and Helene Conway for her assistance with manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Dr. Ritterband is an equity holder of BeHealth Solutions, Inc., which developed the data management system and helped develop the intervention described in this paper. Dr. Ritterband's conflict of interest is being managed by a conflict of interest committee at the University of Virginia, in accordance with their respective conflict of interest policies.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Donaldson MR, Coldiron BM. No end in sight: the skin cancer epidemic continues. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2011;30(1):3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2011.01.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sder.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon R. Skin cancer: an overview of epidemiology and risk factors. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2013;29(3):160–169. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2013.06.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nikolaou V, Stratigos AJ. Emerging trends in the epidemiology of melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170(1):11–19. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12492. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bjd.12492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. DHHS. The Surgeon General's Call to Action to Prevent Skin Cancer. Washington, D.C.; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuong W, Cheng LS, Armstrong AW. Melanoma: epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30(1):113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2011.08.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.det.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bleyer A, Barr R. Introduction--impact of malignant diseases on young adults II. Semin Oncol. 2009;36(5):380. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.07.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stanton WR, Janda M, Baade PD, Anderson P. Primary prevention of skin cancer: a review of sun protection in Australia and internationally. Health Promot Int. 2004;19(3):369–378. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dah310. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dah310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacNeal RJ, Dinulos JG. Update on sun protection and tanning in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007;19(4):425–429. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3282294936. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0b013e3282294936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams AL, Grogan S, Clark-Carter D, Buckley E. Appearance-based interventions to reduce ultraviolet exposure and/or increase sun protection intentions and behaviours: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Br J Health Psychol. 2013;18(1):182–217. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2012.02089.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8287.2012.02089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pew Research Internet Project. Health Fact Sheet. [Accessed November 17, 2014];2014 www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/health-fact-sheet/

- 11.Tate DF, Finkelstein EA, Khavjou O, Gustafson A. Cost effectiveness of internet interventions: review and recommendations. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38(1):40–45. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9131-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12160-009-9131-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fishbein M, Hennessy M, Yzer M, Douglas J. Can we explain why some people do and some people do not act on their intentions? Psychol Health Med. 2003;8(1):3–18. doi: 10.1080/1354850021000059223. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1354850021000059223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arthey S, Clarke VA. Suntanning and sun protection: a review of the psychological literature. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(2):265–274. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)e0063-x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(94)E0063-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reynolds D. Literature review of theory-based empirical studies examining adolescent tanning practices. Dermatol Nurs. 2007;19(5):440–443. 447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cafri G, Thompson JK, Jacobsen PB. Appearance reasons for tanning mediate the relationship between media influence and UV exposure and sun protection. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142(8):1067–1069. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.8.1067. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archderm.142.8.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Danoff-Burg S, Mosher CE. Predictors of tanning salon use: behavioral alternatives for enhancing appearance, relaxing and socializing. J Health Psychol. 2006;11(3):511–518. doi: 10.1177/1359105306063325. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1359105306063325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hillhouse J, Turrisi R, Stapleton J, Robinson J. A randomized controlled trial of an appearance-focused intervention to prevent skin cancer. Cancer. 2008;113(11):3257–3266. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23922. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hillhouse JJ, Stair AW, 3rd, Adler CM. Predictors of sunbathing and sunscreen use in college undergraduates. J Behav Med. 1996;19(6):543–561. doi: 10.1007/BF01904903. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01904903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hillhouse JJ, Turrisi R, Kastner M. Modeling tanning salon behavioral tendencies using appearance motivation, self-monitoring and the theory of planned behavior. Health Educ Res. 2000;15(4):405–414. doi: 10.1093/her/15.4.405. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/her/15.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahler HI, Kulik JA, Butler HA, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX. Social norms information enhances the efficacy of an appearance-based sun protection intervention. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(2):321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.037. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olson AL, Gaffney CA, Starr P, Dietrich AJ. The impact of an appearance-based educational intervention on adolescent intention to use sunscreen. Health Educ Res. 2008;23(5):763–769. doi: 10.1093/her/cym005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thieden E, Philipsen PA, Sandby-Moller J, Wulf HC. Sunscreen use related to UV exposure, age, sex, and occupation based on personal dosimeter readings and sun-exposure behavior diaries. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(8):967–973. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.8.967. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archderm.141.8.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borland R, Hill D, N S. Being sunsmart: Changes in community awareness and reported behaviour following a primary prevention program for skin cancer control. Behav Change. 1990;7(3):126–135. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0813483900007105. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gritz ER, Tripp MK, James AS, et al. Effects of a preschool staff intervention on children's sun protection: outcomes of sun protection is fun! Health Educ Behav. 2007;34(4):562–577. doi: 10.1177/1090198105277850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hay JL, Oliveria SA, Dusza SW, Phelan DL, Ostroff JS, Halpern AC. Psychosocial mediators of a nurse intervention to increase skin self-examination in patients at high risk for melanoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(6):1212–1216. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0822. http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hillhouse JJ, Adler CM, Drinnon J, Turrisi R. Application of Azjen's theory of planned behavior to predict sunbathing, tanning salon use, and sunscreen use intentions and behaviors. J Behav Med. 1997;20(4):365–378. doi: 10.1023/a:1025517130513. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1025517130513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.James AS, Tripp MK, Parcel GS, Sweeney A, Gritz ER. Psychosocial correlates of sun-protective practices of preschool staff toward their students. Health Educ Res. 2002;17(3):305–314. doi: 10.1093/her/17.3.305. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/her/17.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myers LB, Horswill MS. Social cognitive predictors of sun protection intention and behavior. Behav Med. 2006;32(2):57–63. doi: 10.3200/BMED.32.2.57-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/BMED.32.2.57-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stryker JE, Lazovich D, Forster JL, Emmons KM, Sorensen G, Demierre MF. Maternal/female caregiver influences on adolescent indoor tanning. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(6):528 e521–529. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Lane DJ, Mahler HI, Kulik JA. Using UV photography to reduce use of tanning booths: a test of cognitive mediation. Health Psychol. 2005;24(4):358–363. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.358. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hysert PE, Mirand AL, Giovino GA, Cummings KM, Kuo CL. “At Face Value”: age progression software provides personalised demonstration of the effects of smoking on appearance. Tob Control. 2003;12(2):238. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.2.238. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tc.12.2.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahler HI, Kulik JA, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX. Effects of photoaging information and UV photo on sun protection intentions and behaviours: a cross-regional comparison. Psychol Health. 2013;28(9):1009–1031. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2013.777966. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2013.777966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stock ML, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, et al. Sun protection intervention for highway workers: long-term efficacy of UV photography and skin cancer information on men's protective cognitions and behavior. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38(3):225–236. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9151-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12160-009-9151-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glanz K, Schoenfeld E, Weinstock MA, Layi G, Kidd J, Shigaki DM. Development and reliability of a brief skin cancer risk assessment tool. Cancer Detect Prev. 2003;27(4):311–315. doi: 10.1016/s0361-090x(03)00094-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0361-090X(03)00094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barak A, Klein B, Proudfoot JG. Defining Internet-supported therapeutic interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38:4–17. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9130-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12160-009-9130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ritterband LM, Tate DF. The science of internet interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38(1):1–3. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9132-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12160-009-9132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ritterband LM, Thorndike FP, Cox DJ, Kovatchev BP, Gonder-Frederick LA. A behavior change model for internet interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38(1):18–27. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9133-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12160-009-9133-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Locke EA, Latham GP. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation. A 35-year odyssey. Am Psychol. 2002;57(9):705–717. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.57.9.705. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.57.9.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glanz K, Mayer JA. Reducing ultraviolet radiation exposure to prevent skin cancer methodology and measurement. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(2):131–142. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.04.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glanz K, McCarty F, Nehl EJ, et al. Validity of self-reported sunscreen use by parents, children, and lifeguards. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(1):63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Riordan DL, Glanz K, Gies P, Elliott T. A pilot study of the validity of self-reported ultraviolet radiation exposure and sun protection practices among lifeguards, parents and children. Photochem Photobiol. 2008;84(3):774–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00262.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00262.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glanz K, Yaroch AL, Dancel M, et al. Measures of sun exposure and sun protection practices for behavioral and epidemiologic research. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(2):217–222. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2007.46. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archdermatol.2007.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ingledew DK, Ferguson E, Markland D. Motives and sun-related behaviour. J Health Pyschol. 2010;15(1):8–20. doi: 10.1177/1359105309342292. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1359105309342292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lazovich D, Stryker JE, Mayer JA, et al. Measuring nonsolar tanning behavior: indoor and sunless tanning. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(2):225–230. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2007.45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archdermatol.2007.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meade AW, Craig SB. Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychol Methods. 2012;17(3):437–455. doi: 10.1037/a0028085. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0028085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bowen AM, Daniel CM, Williams ML, Baird GL. Identifying multiple submissions in Internet research: preserving data integrity. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(6):964–973. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9352-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10461-007-9352-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Everitt B. Cluster Analysis. London: Heinemann Educational Books; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hartigan JA. Clustering Algorithms. New York: Wiley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Linzer DA, Lewis J. poLCA: an R Package for Polytomous Variable Latent Class Analysis. J Stat Softw. 2011;42(10):1–29. http://dx.doi.org/10.18637/jss.v042.i10. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/biomet/73.1.13. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goldberg MS, Doucette JT, Lim HW, Spencer J, Carucci JA, Rigel DS. Risk factors for presumptive melanoma in skin cancer screening: American Academy of Dermatology National Melanoma/Skin Cancer Screening Program experience 2001-2005. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(1):60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.02.010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lazovich D, Vogel RI, Berwick M, Weinstock M, Anderson KE, Warshaw EM. Indoor tanning and risk of melanoma: A case-control study in a highly exposed population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(6):1557–1568. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1249. http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Markovic SN, Erickson LA, Rao RD, et al. Malignant melanoma in the 21st century, part 1: epidemiology, risk factors, screening, prevention, and diagnosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(3):364–380. doi: 10.4065/82.3.364. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0025-6196(11)61033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Psaty EL, Scope A, Halpern AC, Marghoob AA. Defining the patient at high risk for melanoma. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49(4):362–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04381.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qureshi AA, Zhang M, Han J. Heterogeneity in host risk factors for incident melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer in a cohort of U.S. women. J Epidemiol. 2011;21(3):197–203. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20100145. http://dx.doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20100145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Siskind V, Aitken J, Green A, Martin N. Sun exposure and interaction with family history in risk of melanoma, Queensland, Australia. Int J Cancer. 2002;97(1):90–95. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1563. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ijc.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vishvakarman D, Wong JC. Description of the use of a risk estimation model to assess the increased risk of non-melanoma skin cancer among outdoor workers in Central Queensland, Australia. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2003;19(2):81–88. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0781.2003.00012.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0781.2003.00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cantor D. Review and Summary of Studies on Panel Conditioning. Handbook of longitudinal research: design, measurement, and analysis. 2008:123–138. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sturgis P, Allum N, Brunton-Smith I. Attitudes Over Time: The Psychology of Panel Conditioning. In: Lynn P, editor. Methodology of Longitudinal Surveys. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2009. pp. 113–126. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9780470743874.ch7. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dennis LK, Lowe JB, Snetselaar LG. Tanning behavior among young frequent tanners is related to attitudes and not lack of knowledge about the dangers. Health Educ J. 2009;68(3):232–243. doi: 10.1177/0017896909345195. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0017896909345195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Knight JM, Kirinich AN, Farmer ER, Hood AF. Awareness of the risks of tanning lamps does not influence behavior among college students. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(10):1311–1315. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.10.1311. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archderm.138.10.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Robinson JK, Guevara Y, Gaber R, et al. Efficacy of a sun protection workbook for kidney transplant recipients: a randomized controlled trial of a culturally sensitive educational intervention. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(12):2821–2829. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12932. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ajt.12932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Robinson JK, Rademaker AW, Sylvester JA, Cook B. Summer sun exposure: knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of Midwest adolescents. Prev Med. 1997;26(3):364–372. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/pmed.1997.0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Swindler JE, Lloyd JR, Gil KM. Can sun protection knowledge change behavior in a resistant population? Cutis. 2007;79(6):463–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dalum P, Schaalma H, Kok G. The development of an adolescent smoking cessation intervention--an Intervention Mapping approach to planning. Health Educ Res. 2012;27(1):172–181. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr044. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/her/cyr044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Helsel DL, Jakicic JM, Otto AD. Comparison of techniques for self-monitoring eating and exercise behaviors on weight loss in a correspondence-based intervention. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(10):1807–1810. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.07.014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shay LE, Seibert D, Watts D, Sbrocco T, Pagliara C. Adherence and weight loss outcomes associated with food-exercise diary preference in a military weight management program. Eating behaviors. 2009;10(4):220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.07.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sinadinovic K, Berman AH, Hasson D, Wennberg P. Internet-based assessment and self-monitoring of problematic alcohol and drug use. Addict Behav. 2010;35(5):464–470. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.021. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bennett GG, Glasgow RE. The delivery of public health interventions via the Internet: actualizing their potential. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:273–292. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100235. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fleisher L, Kandadai V, Keenan E, et al. Build it, and will they come? Unexpected findings from a study on a Web-based intervention to improve colorectal cancer screening. J Health Commun. 2012;17(1):41–53. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.571338. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2011.571338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kelders SM, Kok RN, Ossebaard HC, Van Gemert-Pijnen JE. Persuasive system design does matter: a systematic review of adherence to web-based interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(6):e152. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2104. http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nation J, Crusto C, Wandersman A, et al. What works in prevention. Principles of effective prevention programs. Am Psychol. 2003;58(6-7):449–456. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.6-7.449. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.58.6-7.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Proudfoot J. Establishing guidelines for executing and reporting internet intervention research. Cogn Behav Ther. 2011;40(2):82–97. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2011.573807. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2011.573807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.WHO. The World Health Report 2002: Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Lifestyle. Geneva: WHO; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.West R, Gilsenan A, Coste F, et al. The ATTEMPT cohort: a multi-national longitudinal study of predictors, patterns and consequences of smoking cessation; introduction and evaluation of internet recruitment and data collection methods. Addiction. 2006;101(9):1352–1361. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01534.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gardner JS, Szpunar CA, O'Connell MJ, et al. Cohort maintenance and comparability in a pharmacoepidemiologic study using a commercial consumer panel to recruit comparators. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 1996;5(4):207–214. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1557(199607)5:4<207::AID-PDS190>3.0.CO;2-I. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1557(199607)5:4<207∷AID-PDS190>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Glanz K, McCarty F, Nehl EJ, et al. Validity of self-reported sunscreen use by parents, children, and lifeguards. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(1):63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Glanz K, Gies P, O'Riordan DL, et al. Validity of self-reported solar UVR exposure compared with objectively measured UVR exposure. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(12):3005–3012. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0709. http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.O'Riordan DL, Nehl E, Gies P, et al. Validity of covering-up sun-protection habits: Association of observations and self-report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(5):739–744. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.12.015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]