Abstract

Background

Asthma is a leading cause of chronic disease-related school absenteeism. Little data exist on how information on absenteeism might be used to identify children for interventions to improve asthma control. This study investigated how asthma-related absenteeism was associated with asthma control, exacerbations, and associated modifiable risk factors using a sample of children from 35 states and the District of Columbia.

Methods

The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Child Asthma Call-back Survey is a random-digit dialing survey designed to assess the health and experiences of children aged 0–17 years with asthma. During 2014–2015, multivariate analyses were conducted using 2006–2010 data to compare children with and without asthma-related absenteeism with respect to clinical, environmental, and financial measures. These analyses controlled for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

Results

Compared to children without asthma-related absenteeism, children who missed any school because of asthma were more likely to have not well controlled or very poorly controlled asthma (prevalence ratio: 1.50; 95% CI: 1.34–1.69) and visit an emergency department or urgent care center for asthma (prevalence ratio: 3.27; 95% CI: 2.44–4.38). Mold in the home and cost as a barrier to asthma-related health care were also significantly associated with asthma-related absenteeism.

Conclusions

Missing any school because of asthma was associated with suboptimal asthma control, urgent or emergent asthma-related health care utilization, mold in the home, and financial barriers to asthma-related health care. Further understanding of asthma-related absenteeism could establish how to most effectively use absenteeism information as a health status indicator.

INTRODUCTION

Asthma is a common chronic disease of childhood, affecting one in 12 U.S. children.1, 2 Childhood asthma is a leading cause of chronic disease-related school absenteeism in the U.S., associated with >10 million missed school days annually.3 Asthma-related school absenteeism affects most (59%) children with asthma and is linked to lower academic performance, especially among urban minority youth.1, 4–9 Most literature on asthma-related absenteeism and its consequences focuses on differences between children with and without asthma.7, 8, 10–16 Less is known about how absenteeism might be a useful health status indicator among children with asthma.14, 16, 17

Asthma-related school absenteeism can result from asthma exacerbations, lack of asthma control, or routine clinic visits.3, 18–21 Some studies reported associations between absenteeism and secondhand smoke exposure among children with asthma.16, 22, 23 Other modifiable factors affecting asthma control (e.g., home environment, health care access) might be related to school absenteeism, but this possibility is unexplored.16 Given the range of possibilities that can contribute to school absences, the utility of absenteeism for assessing asthma morbidity is not well-described.16 If the implications of asthma-related absenteeism were better understood, this information could be useful to public health officials, educators, policy makers, investigators, and others considering whom to include in school-based efforts to improve asthma control.24–26 Therefore, this study examined how asthma-related school absenteeism was associated with asthma control, asthma exacerbations, and associated modifiable risk factors using a sample of children from 35 states and the District of Columbia with data from 2006–2010.

METHODS

Asthma Call-back Survey

Data were analyzed from the 2006–2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) Child Asthma Call-back Survey (ACBS).27, 28 BRFSS is an ongoing, state-based, random-digit-dialed telephone survey of non-institutionalized U.S. adults.27 Before 2011, BRFSS interviews were conducted via landline telephone.27 BRFSS respondents reporting a child with a diagnosis of asthma (ever) were eligible to participate in the Child ACBS; the child in the household was randomly selected and then asthma status was assessed.28 The Child ACBS is conducted approximately two weeks after the BRFSS telephone interview and is designed to assess the health and experiences of children with asthma.28 Informed consent is obtained and an adult family member serves as a proxy respondent for the child.28 Only one child per household could participate in the Child ACBS.28

To obtain a sufficiently large sample to produce stable estimates, Child ACBS data were combined from 2006–2010.28 Data were weighted to represent children aged 0–17 years with asthma from 35 states and the District of Columbia (i.e., U.S. areas from which Child ACBS data were available from 2006–2010).29 The weighting procedure accounted for states where data were not collected in all years; partial-year data from states were excluded.29 More information on participating states, weight calculations, and response rates is located online and in prior publications.29–31

Studies based on ACBS data are exempt from IRB review at the CDC. State-specific IRB requirements apply to each participating state and the District of Columbia.

Study Sample

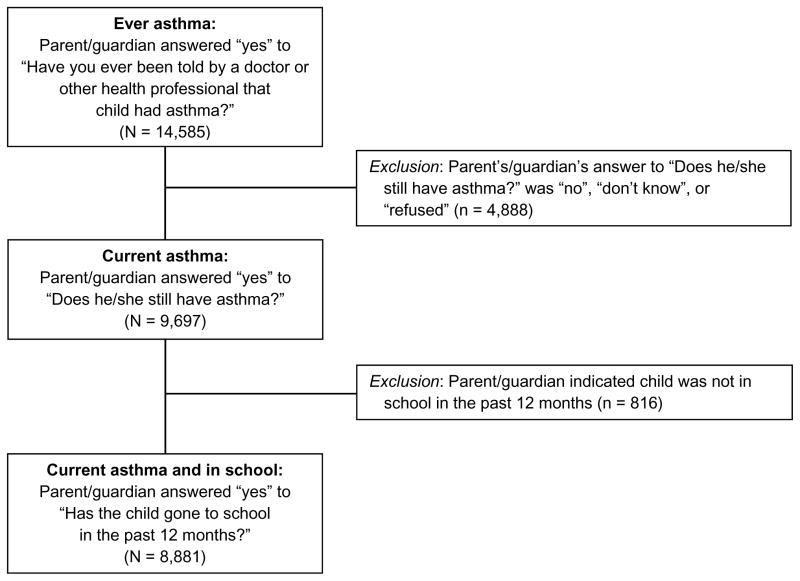

This study was limited to children with current asthma attending school within the past 12 months (Figure 1). Identical to previous publications of ACBS data, children were classified with current asthma if adult proxies responded “yes” to two questions: “Have you ever been told by a doctor, nurse, or other health professional that the child had asthma?” and “Does the child still have asthma?”30–32 Children were categorized as attending school within the past 12 months if the answer was “yes” to the question “Has the child gone to school in the past 12 months?”

Figure 1.

Study Population of Children Aged 0–17 Years in School with Current Asthma: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Asthma Call-Back Survey, 2006–2010

Measures

Characteristics presented here include child age group (at time of interview), sex, race/ethnicity, U.S. census region, child’s health insurance, annual household income, and asthma medication use in the past three months. Asthma medication use was classified into four categories: none, short-acting β agonists (SABAs), ≥1 asthma controller medication (inhaled corticosteroids, long-acting β agonists, leukotriene modifiers, methylxanthines, cromolyn, nedocromil, or immunomodulators), and oral corticosteroid only (without SABA or asthma controller medication[s]).

Because school absenteeism data were right-skewed, children were categorized using the questionnaire item “During the past 12 months, about how many days of school did [he/she] miss because of [his/her] asthma?” Children with responses indicating one or more days missed were classified as having missed ≥1 day of school because of asthma in the past 12 months (hereafter referred to as “missed [any] school for asthma” or “with asthma-related school absenteeism”). Children whose adult proxies answered “zero” were considered to have missed no school for asthma (i.e., no asthma-related absenteeism).

A dependent variable was created to measure asthma control using previously published methods30, 31 which were adapted from the 2007 National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma (EPR-3) and account for the ACBS design.18, 30, 31 Specifically, three impairment measures were assessed: daytime symptoms, night-time symptoms, and SABA use (other than for preventing exercise-induced bronchospasm) during the past three months. Asthma control was defined using the highest impairment level identified for each child across these three measures.30, 31 Children were categorized as having well controlled asthma or “uncontrolled asthma” (i.e., children with asthma classified as not well controlled or very poorly controlled).18, 30, 31 Additionally, using data on asthma control and controller medication use, asthma severity was measured according to previously published methods consistent with EPR-3 guidelines.18, 31 Briefly, children whose asthma was well controlled without asthma controller medication use in the past three months were categorized as having intermittent asthma. Persistent asthma included all children reported to use asthma controller medication (regardless of asthma control status) and children not reported to use asthma controller medication but classified with uncontrolled asthma.31 More information on defining asthma control and severity using ACBS data is available in prior publications.30, 31

Occurrence of asthma exacerbations was assessed using responses to four questionnaire items: “During the past 12 months, has the child had an episode of asthma or an asthma attack?”; “During the past 12 months, has the child had to visit an emergency room or urgent care center because of [his/her] asthma?”; “Besides those emergency room or urgent care center visits, during the past 12 months, how many times did the child see a doctor or other health professional for urgent treatment of worsening asthma symptoms or an asthma episode or attack?”; and “During the past 12 months, that is since [one year ago today], has the child had to stay overnight in a hospital because of [his/her] asthma?” These four variables were combined for the composite variable “acute health care encounters for asthma.”

Cost as a barrier to health care was investigated using questionnaire responses concerning inability to buy medication, see a primary care physician, or see a specialist for asthma in the past 12 months.

School environmental factors were assessed through four questionnaire items: “Does the child have a written asthma action plan or asthma management plan on file at school?” (hereafter referred to as “school AAP”); “Does the school the child goes to allow children with asthma to carry their medication with them while at school?”; “Are there any pets such as dogs, cats, hamsters, birds or other feathered or furry pets in the child’s classroom?”; and “Are you aware of any mold problems in the child’s school?”

Home environment variables were related to secondhand smoke, pets allowed in children’s bedrooms, reports of seeing or smelling mold in the home in the past 30 days, and report of seeing cockroaches, mice, or rats inside the home in the past 30 days.

As in previous analyses, uninformative responses (i.e., don’t know, missing, refused) were considered negative responses (i.e., not having the relevant outcome).33

Statistical Analysis

ACBS sampling weights were used to calculate population estimates representative of 35 states and the District of Columbia — i.e., areas with available Child ACBS data from 2006–2010. These sampling weights accounted for BRFSS and ACBS nonresponse and unequal sampling probabilities, as well as differences across states in the number of participating years during 2006–2010.30, 31, 34 To properly account for the complex sample survey design,33, 35 the entire dataset (N = 14,585 children ever diagnosed with asthma) was retained in the final analyses; only results generated from the stratum of the selected population of 8,881 children with current asthma attending school within the past 12 months (Figure 1) are presented.35

The χ2 test was used to compare children with asthma-related school absenteeism to those without asthma-related absenteeism, among all children with current asthma. Variance under the sampling conditions (i.e., sampling with replacement) was estimated with the Taylor series method.33, 36 For multivariate analyses, ORs, prevalence ratios (PRs; predicted marginal risk ratios)30, 37, and 95% CIs were calculated for associations between asthma-related school absenteeism and all dependent variables; these were adjusted for child age group, race/ethnicity, asthma medication use, and annual household income. Because many dependent variables were common (>10% prevalence in this study population)38, ORs were larger than PRs; therefore, this study highlights findings from PRs.

Complex sample survey procedures were used to perform χ2 testing and logistic regression in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC);39, 40 PRs were calculated using SAS-callable SUDAAN (version 10.0.0, RTI International, NC).41 Statistical significance was determined as a P value <0.05. Results based on <50 unweighted respondents (i.e., percentages based upon a denominator <50) or for which the relative standard error (standard error/prevalence estimate; a measure of an estimate’s reliability) was >0.3 were suppressed.30, 31, 42

Three distinct sensitivity analyses were conducted: dichotomization of asthma-related absenteeism using a greater number of school days missed (≥5 versus ≤4); controlling for asthma severity instead of asthma medication use (except for outcome asthma control, because the definition of asthma severity included asthma control); and excluding uninformative responses.

RESULTS

In this study, 8,881 unique children who had current asthma and attended school in the past 12 months were identified (Figure 1). Because sampling weights were incorporated into these analyses, this study population represents approximately 4.3 million children.

Approximately half of children in school with current asthma missed at least one school day because of asthma in the past 12 months (51%; 95% CI: 48.2–53.0; Table 1). The percentage of children who missed ≥1 school day for asthma varied significantly by geographic region (P = .004). These children were more likely to have Medicaid/Medicare insurance than children who did not miss school for asthma (20.9% vs. 16.3%), but differences in health insurance type by absenteeism status did not reach statistical significance (P = .05). Annual household incomes <$25,000 were more common among children who missed school for asthma (29.3% vs.19.6%). Children with asthma-related absenteeism were more likely to be black or Hispanic than children who missed no school for asthma. In contrast, children without asthma-related absenteeism were more likely to be non-Hispanic white. Also, children who missed school for asthma were more likely to use asthma controller medication than children who missed no school for asthma (51.3% vs. 35.7%). Regarding asthma severity, persistent asthma was more common among children with asthma-related absenteeism than children without asthma-related absenteeism (69.5% vs. 47.8%, P < .001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Children in School with Current Asthma: BRFSS ACBS, 2006–2010

| Characteristic | All (N = 8,881b) n (weighted %; 95% CI) |

No Missed School for Asthmaa (n = 4,993b) n (weighted %; 95% CI) |

Missed ≥1 School Day for Asthmaa (n = 3,888b) n (weighted %; 95% CI) |

Pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||||

| Age group, years | .001 | |||

| 0–4 | 662 (11.1; 9.5–12.7) | 309 (10.0; 8.0–12.0) | 353 (12.3; 9.9–14.7) | |

| 5–11 | 3,622 (47.5; 45.1–49.9) | 1,813 (44.1; 41.0–47.2) | 1,809 (50.8; 47.1–54.5) | |

| 12–17 | 4,597 (41.4; 39.0–43.8) | 2,871 (45.9; 43.0–48.8) | 1,726 (37.0; 33.3–40.7) | |

| Census region | .004 | |||

| Northeast | 2,200 (25.6; 24.0–27.2) | 1,286 (28.5; 26.0–31.0) | 914 (22.8; 20.4–25.2) | |

| Midwest | 2,858 (25.7; 24.3–27.1) | 1,673 (27.6; 25.4–29.8) | 1,185 (23.9; 21.7–26.1) | |

| South | 1,942 (27.2; 25.8–28.6) | 955 (24.5; 22.5–26.5) | 987 (29.9; 27.4–32.4) | |

| West | 1,881 (21.5; 19.5–23.5) | 1,079 (19.4; 16.7–22.1) | 802 (21.5; 21.0–26.0) | |

| Health insurance | 0.05 | |||

| Parent/guardian employer | 5,945 (63.7; 61.4–66.0) | 3,502 (67.4; 64.5–70.3) | 2,443 (60.1; 56.6–63.6) | |

| Medicaid/Medicare | 1,440 (18.6; 16.7–20.5) | 699 (16.3; 14.1–18.5) | 741 (20.9; 17.8–24.0) | |

| State children’s health insurance | 508 (5.7; 4.7–6.7) | 274 (5.0; 3.8–6.2) | 234 (6.3; 4.7–7.9) | |

| Other | 642 (8.3; 6.7–9.8) | 339 (7.6; 5.6–9.6) | 303 (8.8; 6.3–11.3) | |

| None | 290 (3.2; 2.4–4.0) | 147 (3.1; 1.9–4.3) | 143 (3.3; 2.3–4.3) | |

| Unknown | 56 (0.5; 0.3–0.7) | 32 (0.5; 0.1–0.9) | 24 (0.5; 0.3–0.7) | |

| Household income, annual | <.001 | |||

| <$15,000 | 719 (11.3; 9.1–13.5) | 313 (8.6; 6.6–10.6) | 406 (13.9; 10.4–17.4) | |

| $15,000–$24,999 | 1,096 (13.2; 11.6–14.8) | 571 (11.0; 9.2–12.8) | 525 (15.4; 12.7–18.1) | |

| $25,000–$49,999 | 1,895 (19.2; 17.4–21.0) | 1,014 (19.8; 17.3–22.3) | 881 (18.6; 16.2–21.0) | |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 1,531 (14.9; 13.5–16.3) | 869 (13.9; 12.1–15.7) | 662 (15.9; 13.5–18.3) | |

| >$75,000 | 3,165 (35.6; 33.4–37.8) | 1,955 (39.8; 36.9–42.7) | 1,210 (31.4; 28.1–34.7) | |

| Unknown | 475 (5.8; 4.8–6.8) | 271 (6.9; 5.1–8.7) | 204 (4.7; 3.5–5.9) | |

| Race/ethnicity | <.001 | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 5,953 (55.2; 52.8–57.6) | 3,548 (60.6; 57.7–63.5) | 2,405 (49.9; 46.2–53.6) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 904 (15.3; 13.5–17.1) | 413 (12.1; 10.1–14.1) | 491 (18.4; 15.3–21.5) | |

| Hispanic | 884 (16.4; 14.2–18.6) | 429 (14.1; 11.6–16.6) | 455 (18.5; 15.2–21.8) | |

| Other | 824 (9.4; 7.8–11.0) | 435 (8.9; 6.9–10.9) | 389 (10.0; 7.7–12.4) | |

| Unknown | 316 (3.7; 2.9–4.5) | 168 (4.3; 3.1–5.5) | 148 (3.2; 2.3–4.0) | |

| Sex | .47 | |||

| Male | 5,040 (56.3; 53.9–58.7) | 2,772 (55.0; 51.9–58.1) | 2,268 (57.7; 54.0–61.4) | |

| Female | 3,808 (43.4; 41.0–45.8) | 2,202 (44.7; 41.6–47.8) | 1,606 (42.1; 38.4–45.8) | |

| Unknown | --c --c | --c --c | --c --c | |

| Clinical | ||||

| Asthma medication used | <.001 | |||

| None | 2,958 (31.9; 29.7–34.1) | 2,034 (41.2; 38.3–44.1) | 924 (22.8; 20.1–25.5) | |

| SABA only | 1,985 (22.8; 20.6–25.0) | 1,131 (22.8; 20.1–25.5) | 854 (22.7; 19.2–26.2) | |

| ≥1 asthma controllere | 3,836 (43.6; 41.2–46.0) | 1,813 (35.7; 33.0–38.4) | 2,023 (51.3; 47.6–55.0) | |

| Oral corticosteroid onlyf | 102 (1.8; 1.0–2.6) | --c --c | 87 (3.2; 1.6–4.8) | |

| Asthma severityg | <.001 | |||

| Intermittent | 3,801 (41.2; 38.8–43.6) | 2,586 (52.2; 49.3–55.1) | 1,215 (47.8; 44.7–50.9) | |

| Persistent | 5,080 (58.8; 56.4–61.2) | 2,407 (47.8; 44.9–50.7) | 2,673 (69.5; 66.4–72.6) | |

|

| ||||

| Total | 8,881h | 4,993 (49.4; 47.0–51.8) | 3,888 (50.6; 48.2–53.0) | |

SABA, short-acting β agonist.

During the past 12 months.

Boldface indicates statistical significance (P < .05).

Results based on <50 unweighted respondents or for which the relative standard error was >0.3 were suppressed.

During the past three months.

Defined as inhaled corticosteroids, long-acting β agonists, leukotriene modifiers, methylxanthines, cromolyn, nedocromil, or immunomodulators (during the past three months).

Without SABA or asthma controller medication (during the past three months).

Children were classified as having intermittent asthma if their asthma was well controlled without asthma controller medication use in the past 3 months. Persistent asthma included all children using asthma controller medication (regardless of asthma control status) and children who were not using asthma controller medication but had uncontrolled asthma.

Total study population representative of 4,257,045 children in 35 U.S. states (AZ, CA, CT, GA, HI, IA, IL, IN, KS, LA, MA, MD, ME, MI, MO, MS, MT, NE, ND, NH, NJ, NM, NY, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, TX, UT, VA, VT, WA, WI, WV) and the District of Columbia.

Table 2 shows differences in asthma clinical measures by asthma-related absenteeism, including results of multivariate analyses. Children who missed school for asthma were more likely to have uncontrolled asthma than children who did not miss school (PR: 1.50; 95% CI: 1.34–1.69). Children who missed any school because of asthma were more likely to report asthma episodes or attacks (PR: 1.50; 95% CI: 1.34–1.69) and to have sought health care for urgent or emergency treatment of asthma (PR: 3.27; 95% CI: 2.44–4.38). Overall, asthma-related hospitalizations were uncommon and reported for only 5.2% of children with asthma-related absenteeism and 1.8% of children without asthma-related absenteeism (PR: 1.72; 95% CI: 0.86–3.42). The composite variable of acute health care encounters for asthma (i.e., emergency department visits, urgent care center visits, other urgent visits, and hospitalizations) was also more frequent among children with than without asthma-related absenteeism (61.3% vs. 21.6%; PR: 2.41; 95% CI: 2.10–2.78). Similarly significant results for asthma-related absenteeism and clinical measures resulted from the multivariate logistic regression model.

Table 2.

Asthma-Related Measures and Absenteeism Among Children in School with Current Asthma: BRFSS ACBS, 2006–2010a

| Clinical Measure | No Missed School for Asthma (n = 4,993) Weighted % (95% CI) |

Missed ≥1 School Day for Asthma (n = 3,888) Weighted % (95% CI) |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Prevalence Ratiob (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma uncontrolledc | 24.6 (22.1–27.1) | 47.7 (44.0–51.4) | 2.12 (1.73–2.69) | 1.50 (1.34–1.69) |

| ≥1 asthma episode or attack | 43.0 (39.9–46.1) | 70.6 (67.1–74.1) | 2.68 (2.17–3.31) | 1.50 (1.38–1.64) |

| Visited ED or urgent care center for asthma | 6.5 (4.7–8.3) | 29.1 (25.8–32.4) | 4.63 (3.35–6.39) | 3.27 (2.44–4.38) |

| Saw health professional for urgent treatment of worsening asthma symptoms or asthma episode/attackd | 19.2 (16.5–21.9) | 54.1 (50.6–57.6) | 4.24 (3.37–5.34) | 2.44 (2.08–2.86) |

| Hospitalized ≥1 night for asthma | -- --e | 5.2 (3.6–6.8) | 1.90 (0.93–3.89)f | 1.72 (0.86–3.42)f |

| ≥1 acute health care encounter for asthmag | 21.6 (18.9–24.5) | 61.3 (57.8–64.8) | 4.88 (3.91–6.09) | 2.41 (2.10–2.78) |

ED, emergency department.

Data are representative of 35 U.S. states (AZ, CA, CT, GA, HI, IA, IL, IN, KS, LA, MA, MD, ME, MI, MO, MS, MT, NE, ND, NH, NJ, NM, NY, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, TX, UT, VA, VT, WA, WI, WV) and the District of Columbia.

Adjusted for child age group, race/ethnicity, annual household income, asthma medication use. Referent is children with no missed school for asthma.

Based on child’s day symptoms, night symptoms, and SABA use in the past three months. “Uncontrolled asthma” is a composite variable consisting of not well controlled and very poorly controlled asthma. Not well controlled asthma was present among 26.7% (95% CI: 23.4–29.9%) of children with asthma-related absenteeism and 16.2% (95% CI: 14.0–18.3%) of children without asthma-related absenteeism (P < .001). Very poorly controlled asthma was present among 21.0% (95% CI: 17.8–24.3%) of children with asthma-related absenteeism and 8.5% (95% CI: 6.9–10.0%) of children without asthma-related absenteeism (P < .001). For children without asthma-related absenteeism, the prevalence estimate for uncontrolled asthma differed slightly from the sum of estimates for not well controlled and very poorly controlled asthma because of rounding.

Besides the aforementioned ED or urgent care center visits.

Results based on <50 unweighted respondents or for which the relative standard error was >0.3 were suppressed.

Estimate not reliable because relative standard error >0.3.

Composite variable of ED visits, urgent care center visits, urgent visits other than ED or urgent care center visits, and hospitalizations.

In Table 3, missed school for asthma was associated with inability to see a primary care doctor for asthma (PR: 2.00; 95% CI: 1.26–3.19), see a specialist for asthma (PR: 2.97; 95% CI: 1.68–5.24), and buy medication for asthma (PR: 1.82; 95% CI: 1.23–2.71). Mold in the home in the past 30 days was more common among children who missed school for asthma, compared to those who did not (PR: 1.83; 95% CI: 1.36–2.47).

Table 3.

Financial and Environmental Factors Associated with Asthma-Related School Absenteeism: BRFSS ACBS, 2006–2010a

| Variable | No Missed School for Asthma (n = 4,993) Weighted % (95% CI) |

Missed ≥1 School Day for Asthma (n = 3,888) Weighted % (95% CI) |

Odds Ratiob (95% CI) | Prevalence Ratiob (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost as a barrier to asthma-related health care | ||||

| Unable to see primary care doctor | 2.4 (1.4–3.4) | 5.5 (4.3–6.7) | 2.08 (1.25–3.47) | 2.00 (1.26–3.19) |

| Unable to see specialist | 1.3 (0.7–1.9) | 4.6 (2.8–6.4) | 3.34 (1.89–5.92) | 2.97 (1.68–5.24) |

| Unable to buy medication | 5.1 (3.3–6.9) | 10.7 (8.3–13.1) | 2.05 (1.30–3.22) | 1.82 (1.23–2.71) |

| School environment | ||||

| Asthma action plan on file at school | 36.0 (33.3–38.7) | 43.5 (40.0–47.0) | 1.23 (1.02–1.50) | 1.12 (1.00–1.25) |

| Allowed to self-carry asthma medication | 46.8 (43.9–49.7) | 43.2 (39.7–46.7) | 0.91 (0.75–1.11) | 0.96 (0.86–1.06) |

| Feathered or furry pets in classroom | 3.9 (2.9–4.9) | 4.5 (3.1–5.9) | 1.05 (0.69–1.60) | 1.17 (0.74–1.68) |

| Mold problems in school | 1.9 (1.1–2.7) | 2.6 (1.6–3.6) | 1.50 (0.96–2.33) | 1.48 (0.97–2.27) |

| Home environment | ||||

| Secondhand smoke | 7.9 (6.5–9.3) | 11.7 (8.8–14.6) | 1.34 (1.00–1.92) | 1.22 (0.95–1.57) |

| Pets in bedroom | 37.7 (34.8–40.6) | 31.3 (28.2–34.4) | 0.83 (0.68–1.02) | 0.95 (0.84–1.07) |

| Cockroaches seen | 7.8 (6.0–9.6) | 7.5 (5.9–9.1) | 0.93 (0.65–1.32) | 0.85 (0.62–1.17) |

| Mice or rats seen | 6.1 (4.7–7.5) | 5.3 (3.7–6.9) | 0.86 (0.58–1.29) | 0.83 (0.57–1.21) |

| Mold seen or smelled | 6.4 (5.0–7.8) | 12.3 (9.8–14.8) | 1.92 (1.38–2.68) | 1.83 (1.36–2.47) |

Data are representative of 35 U.S. states (AZ, CA, CT, GA, HI, IA, IL, IN, KS, LA, MA, MD, ME, MI, MO, MS, MT, NE, ND, NH, NJ, NM, NY, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, TX, UT, VA, VT, WA, WI, WV) and the District of Columbia.

Adjusted for child age group, race/ethnicity, annual household income, asthma medication use. Referent is children with no missed school for asthma.

Sensitivity analysis results were similar to the main results, with several exceptions. Asthma-related absenteeism of ≥5 days (Tables S1 and S2) was associated with asthma-related hospitalizations and classroom pets, but not school AAPs. After controlling for asthma severity instead of asthma medication use (Tables S1 and S2), school AAPs were no longer associated with asthma-related absenteeism of ≥1 day. Compared to the main analysis, excluding uninformative responses revealed significant associations between asthma-related hospitalizations (PR: 3.37; 95% CI: 1.56–7.32) and mold problems in school (PR: 1.55; 95% CI: 1.02–2.35), but not school AAPs (PR: 1.09; 95% CI: 0.98–1.22).

DISCUSSION

In a survey of children in school with current asthma from 35 U.S. states and the District of Columbia, over half of children missed at least one school day because of asthma in the past 12 months. Even after controlling for potential confounding variables, missing any school for asthma was associated with uncontrolled asthma, asthma episodes/attacks, urgent/emergent health care utilization for asthma, cost as a barrier to asthma-related health care, and reported signs of mold in the home.

This analysis identified new or newly quantified associations between asthma-related school absenteeism, clinical measures, and potentially modifiable factors that are representative of >4 million children with current asthma. Given the large population of children this study’s sample represented and the high frequency of absenteeism, even small percentages experiencing absenteeism with modifiable risk factor (e.g., 5.5% of children with asthma-related absenteeism were unable to see a primary care doctor for asthma because of cost) reflect a substantial number of children affected in these areas.

These results suggested even one missed school day because of asthma could provide useful information. For public health officials, educators, policy makers, investigators, or others working with schools, asthma-related absenteeism might enhance the identification of children whose asthma control could be improved through intensified clinical, environmental, or case management services.24, 25, 43–45 For clinicians, parent, guardian, or caregiver reporting of asthma-related school absenteeism might prove useful for identifying children with asthma who could benefit from an assessment of their need for home mold remediation, case management, or additional interventions recommended by the EPR-3 guidelines.18

As the importance of prevention and health care-public health collaboration is increasingly emphasized in the U.S.46, these findings highlight opportunities to improve asthma control in children using school absenteeism information. Studies of asthma prevalence and communicable diseases (e.g., influenza, dengue) have suggested school absenteeism data are timely, relatively inexpensive, and complementary to existing methods.11, 12, 47, 48 Additionally, this investigation could inform future studies of school absenteeism as a health indicator for other child health concerns such as diabetes or substance abuse.17, 49–52

These findings support prior literature. The frequency with which children with asthma missed school in this study was similar to prior estimates.3 School absenteeism is a known consequence of asthma exacerbations and lack of asthma control, and environmental mold is known to affect asthma control.53, 54

Although asthma-related school absenteeism was associated with uncontrolled asthma, it was also associated with asthma controller medication use. These results do not support the hypothesis that asthma-related school absenteeism is related to lower use of asthma controller medication. This investigation is not the first to identify a positive relationship between school absenteeism and asthma medication use; similar findings were reported from the 2007 California Health Interview Survey.55 This study’s cross-sectional survey design affects interpretation of results. Medication adherence, medication regimen appropriateness, or proper inhaler technique could not be ascertained. Alternatively, children with asthma episodes/attacks severe enough to cause school absenteeism could have then received a higher level of routine management involving asthma controller medication.18

Unlike prior literature56, 57, this investigation did not find significant associations between factors affecting school indoor quality and school absenteeism; this difference might be attributable to the low frequency of classroom pets and school mold problems (as reported by children’s adult proxies) in the data.

Limitations

These survey data were cross-sectional; therefore temporal proximity between asthma-related absenteeism and other variables could not be determined. Absenteeism rates could not be calculated because data on total number of attended school days were unavailable. These findings cannot be generalized to children in the 15 states not included in this dataset or children without household access to landline telephones; interview responses were provided by children’s adult proxies and could not be verified. Non-response bias was possible because survey response rates for participating states were approximately 50%, but sampling and weighting procedures helped diminish the potential impact on results.30, 34 Finally, the content of the ACBS questionnaire circumscribed the ability to investigate other potential contributors to school absenteeism.16, 58

Conclusion

This study analyzed data on children with current asthma from 35 U.S. states and the District of Columbia and found approximately half of children missed at least one school day because of asthma. Missing even one day of school for asthma over a 12-month period was associated with uncontrolled asthma, asthma episodes/attacks, asthma-related urgent/emergent health care utilization, reported signs of mold in the home, and reporting cost as a barrier to asthma-related medication and outpatient care. These findings suggest opportunities to improve asthma control. Further understanding of asthma-related absenteeism, including extended and repeated absence, could establish how to most effectively use absenteeism information as a health status indicator.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jeanne Moorman and Hatice Zahran for contributing to the development of this study. We are grateful to the states and jurisdictions that contributed data for this study. The Asthma Call-back Survey is funded by the National Asthma Control Program in the Air Pollution and Respiratory Health Branch of the National Center for Environmental Health. In 2006–2010 the Asthma Call-back Survey was jointly administered with the Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology and Laboratory Services, Division of Behavioral Surveillance. No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Footnotes

Financial disclosure: No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper

Conflict of interest: No conflicts of interest and no external funding were reported by the authors of this paper

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Asthma in the US. [cited 2015 April 17]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/pdf/2011-05-vitalsigns.pdf.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most Recent Asthma Data. [cited 2015 April 28]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_data.htm.

- 3.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Liu X. Asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality: United States, 2005–2009. Natl Health Stat Report. 2011;(32):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Basch CE. Asthma and the achievement gap among urban minority youth. J Sch Health. 2011;81(10):606–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moonie S, Sterling DA, Figgs LW, Castro M. The relationship between school absence, academic performance, and asthma status. J Sch Health. 2008;78(3):140–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moonie SA, Sterling DA, Figgs L, Castro M. Asthma status and severity affects missed school days. J Sch Health. 2006;76(1):18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2006.00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liberty KA, Pattemore P, Reid J, Tarren-Sweeney M. Beginning school with asthma independently predicts low achievement in a prospective cohort of children. Chest. 2010;138(6):1349–55. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moonie S, Cross CL, Guillermo CJ, Gupta T. Grade retention risk among children with asthma and other chronic health conditions in a large urban school district. Postgrad Med. 2010;122(5):110–5. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2010.09.2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fowler MG, Davenport MG, Garg R. School functioning of U.S. children with asthma. Pediatrics. 1992;90(6):939–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silverstein MD, Mair JE, Katusic SK, Wollan PC, O’Connell EJ, Yunginger JW. School attendance and school performance: a population-based study of children with asthma. J Pediatr. 2001;139(2):278–83. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.115573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medaglia F, Knorr RS, Condon SK, Charleston AC. School-based pediatric asthma surveillance in Massachusetts from 2005 to 2009. J Sch Health. 2013;83(12):907–14. doi: 10.1111/josh.12109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knorr RS, Condon SK, Dwyer FM, Hoffman DF. Tracking pediatric asthma: the Massachusetts experience using school health records. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112(14):1424–7. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petronella SA, Bricker SK, Perrotta D, Brown C, Brooks EG. Addressing asthma in Texas: development of a school-based asthma surveillance program for Texas elementary schools. J Sch Health. 2006;76(6):227–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2006.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parcel GS, Gilman SC, Nader PR, Bunce H. A comparison of absentee rates of elementary schoolchildren with asthma and nonasthmatic schoolmates. Pediatrics. 1979;64(6):878–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mizan SS, Shendell DG, Rhoads GG. Absence, extended absence, and repeat tardiness related to asthma status among elementary school children. J Asthma. 2011;48(3):228–34. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.555038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shendell DG, Alexander MS, Sanders DL, Jewett A, Yang J. Assessing the potential influence of asthma on student attendance/absence in public elementary schools. J Asthma. 2010;47(4):465–472. doi: 10.3109/02770901003734298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weitzman M, Klerman LV, Lamb G, Menary J, Alpert JJ. School absence: a problem for the pediatrician. Pediatrics. 1982;69(6):739–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma—Full Report 2007. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2007. NIH Publication No. 07-4051. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmier JK, Manjunath R, Halpern MT, Jones ML, Thompson K, Diette GB. The impact of inadequately controlled asthma in urban children on quality of life and productivity. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;98(3):245–51. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60713-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dean BB, Calimlim BM, Kindermann SL, Khandker RK, Tinkelman D. The impact of uncontrolled asthma on absenteeism and health-related quality of life. J Asthma. 2009;46(9):861–6. doi: 10.3109/02770900903184237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCowan C, Bryce FP, Neville RG, Crombie IK, Clark RA. School absence--a valid morbidity marker for asthma? Health Bull (Edinb) 1996;54(4):307–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilliland FD, Berhane K, Islam T, Wenten M, Rappaport E, Avol E, et al. Environmental tobacco smoke and absenteeism related to respiratory illness in schoolchildren. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(10):861–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerald LB, Gerald JK, Gibson L, Patel K, Zhang S, McClure LA. Changes in environmental tobacco smoke exposure and asthma morbidity among urban school children. Chest. 2009;135(4):911–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hollenbach JP, Cloutier MM. Implementing school asthma programs: Lessons learned and recommendations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(6):1245–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cicutto L, Gleason M, Szefler SJ. Establishing school-centered asthma programs. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(6):1223–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruzzese JM, Evans D, Wiesemann S, Pinkett-Heller M, Levison MJ, Du Y, et al. Using school staff to establish a preventive network of care to improve elementary school students’ control of asthma. J Sch Health. 2006;76(6):307–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2006.00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. [cited 2015 April 28]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/asthma/survey/brfss.html.

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. BRFSS Asthma Call-back Survey. [cited 2015 April 28]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/acbs/

- 29.2006–2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Asthma Call-Back Survey History and Analysis Guidance. [cited 2015 October 7]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/acbs/history/ACBS_06_10.pdf.

- 30.Zahran HS, Bailey CM, Qin X, Moorman JE. Assessing asthma control and associated risk factors among persons with current asthma - findings from the child and adult Asthma Call-back Survey. J Asthma. 2014:1–9. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2014.956894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zahran HS, Bailey CM, Qin X, Moorman JE. Assessing asthma severity among children and adults with current asthma. J Asthma. 2014;51(6):610–7. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2014.892966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moorman JE, Akinbami LJ, Bailey CM, Zahran HS, King ME, Johnson CA, et al. National surveillance of asthma: United States, 2001–2010. Vital Health Stat. 2012;3(35):1–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mirabelli MC, Beavers SF, Chatterjee AB, Moorman JE. Age at asthma onset and subsequent asthma outcomes among adults with active asthma. Respir Med. 2013;107(12):1829–36. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multiple Year (2006 ~ 2010) Child Asthma Call-back Survey Prevalence Tables - Technical Information. [cited 2015 April 28]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/asthma/acbs/acbstechnical.htm.

- 35.Graubard BI, Korn EL. Survey inference for subpopulations. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144(1):102–6. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Council of American Survey Research. Organizations code of standards and ethics for survey research. [cited 2015 April 29]; Available from: http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.casro.org/resource/resmgr/casro_code_of_standards.pdf.

- 37.Bieler GS, Brown GG, Williams RL, Brogan DJ. Estimating model-adjusted risks, risk differences, and risk ratios from complex survey data. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(5):618–23. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Continuous NHANES Web Tutorial. [cited 2015 May 11]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/tutorials/NHANES/NHANESAnalyses/LogisticRegression/Info1.htm.

- 39.SAS/STAT(R) 9.2 User’s Guide, Second Edition: PROC SURVEYFREQ Statement. [cited 2015 October 7]; Available from: http://support.sas.com/documentation/cdl/en/statug/63033/HTML/default/viewer.htm#statug_surveyfreq_sect004.htm.

- 40.SAS/STAT(R) 9.2 User’s Guide, Second Edition: PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC Statement. [cited 2015 October 7]; Available from: http://support.sas.com/documentation/cdl/en/statug/63033/HTML/default/viewer.htm#statug_surveylogistic_sect004.htm.

- 41.RTI International SUDAAN Procedures: Logistic (RLOGIST) Example #3. [cited 2015 October 7]; Available from: http://www.rti.org/sudaan/pdf_files/110Example/Logistic%20Example%203.pdf.

- 42.CDC BRFSS 2010 Child Asthma Data: Technical Information. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/asthma/brfss/2010/brfsschildtechinfo.htm.

- 43.Moricca ML, Grasska MA, MBM, Morphew T, Weismuller PC, Galant SP. School asthma screening and case management: attendance and learning outcomes. J Sch Nurs. 2013;29(2):104–12. doi: 10.1177/1059840512452668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levy M, Heffner B, Stewart T, Beeman G. The efficacy of asthma case management in an urban school district in reducing school absences and hospitalizations for asthma. J Sch Health. 2006;76(6):320–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2006.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coffman JM, Cabana MD, Yelin EH. Do school-based asthma education programs improve self-management and health outcomes? Pediatrics. 2009;124(2):729–42. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Institute of Medicine. Primary Care and Public Health: Exploring Integration to Improve Population Health. 2012 Available from: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2012/Primary-Care-and-Public-Health.aspx. [PubMed]

- 47.Kom Mogto CA, De Serres G, Douville Fradet M, Lebel G, Toutant S, Gilca R, et al. School absenteeism as an adjunct surveillance indicator: experience during the second wave of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic in Quebec, Canada. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e34084. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheng CK, Channarith H, Cowling BJ. Potential use of school absenteeism record for disease surveillance in developing countries, case study in rural Cambodia. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e76859. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Glaab LA, Brown R, Daneman D. School attendance in children with Type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2005;22(4):421–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bernal J, Frongillo EA, Herrera HA, Rivera JA. Food insecurity in children but not in their mothers is associated with altered activities, school absenteeism, and stunting. J Nutr. 2014;144(10):1619–26. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.189985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Belachew T, Hadley C, Lindstrom D, Gebremariam A, Lachat C, Kolsteren P. Food insecurity, school absenteeism and educational attainment of adolescents in Jimma Zone Southwest Ethiopia: a longitudinal study. Nutr J. 2011;10:29. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-10-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weitzman M. School absence rates as outcome measures in studies of children with chronic illness. J Chronic Dis. 1986;39(10):799–808. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(86)90082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Institute of Medicine. Clearing the Air: Asthma and Indoor Air Exposures. 2000 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25077220. [PubMed]

- 54.Reddel HK, Taylor DR, Bateman ED, Boulet LP, Boushey HA, Busse WW, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: asthma control and exacerbations: standardizing endpoints for clinical asthma trials and clinical practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(1):59–99. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200801-060ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meng YY, Babey SH, Wolstein J. Asthma-related school absenteeism and school concentration of low-income students in California. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E98. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.110312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Daisey JM, Angell WJ, Apte MG. Indoor air quality, ventilation and health symptoms in schools: an analysis of existing information. Indoor Air. 2003;13(1):53–64. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0668.2003.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mendell MJ, Heath GA. Do indoor pollutants and thermal conditions in schools influence student performance? A critical review of the literature. Indoor Air. 2005;15(1):27–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2004.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lipstein EA, Perrin JM, Kuhlthau KA. School absenteeism, health status, and health care utilization among children with asthma: associations with parental chronic disease. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):e60–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.