Abstract

Angiostrongylus vasorum is a nematode that lives in the pulmonary arteries and right cardiac ventricle of domestic dogs and wild canids. It is increasingly being reported in several European countries and North America. This parasite induces inflammatory verminous pneumonia, causing severe respiratory disease in dogs. In some instances, coagulopathies, neurological signs and even death may occur. Scant data are available regarding the occurrence of A. vasorum in Portugal. Therefore, sera of 906 shelter dogs from North to South mainland Portugal were collected. ELISAs to detect A. vasorum circulating antigen and specific antibodies against this parasite were performed. A total of six dogs [0.66 %, 95 % confidence intervals (CI) 0.24–1.43] were positive for both A. vasorum antigen and antibody detection, indicating an active infection, and 12 dogs (1.32 %, CI 0.68–2.30) were A. vasorum antibody-positive only. Regions with antigen- and antibody-positive animals overlapped and were distributed over nearly all sampled areas in the country. This is the first large-scale ELISA-based serological survey for A. vasorum in dogs from Portugal. The endemic occurrence of A. vasorum in dogs from different geographical areas of Portugal is therefore confirmed.

Keywords: Angiostrongylus vasorum, Dog, ELISA, Seroprevalence, Epidemiology, Portugal

Introduction

Angiostrongylus vasorum, also known as the French heartworm, is described to have apparently spread in the last decade into previously uninfected areas (Helm et al. 2010). It is a potentially lethal parasite that resides in the heart and pulmonary arteries of dogs and wild carnivores, with gastropods acting as obligate intermediate hosts (Guilhon and Cens 1973). This nematode may cause a wide spectrum of manifestations in dogs, ranging from mild (or even absent) to severe forms that can be fatal. Respiratory signs (coughing and dyspnoea), bleeding disorders (haemorrhages) and neurological signs are the most frequent clinical features described. Howbeit, non-specific signs such as depression, weight loss, anorexia and exercise intolerance may also be present (Chapman et al. 2004; Wessmann et al. 2006; Koch and Willesen 2009). Such a wide variety of clinical signs makes it challenging to confirm or exclude a diagnosis of canine angiostrongylosis based exclusively on a clinical assessment.

A definite diagnosis can be reached using the Baermann method, through the detection of A. vasorum first stage larvae (L1), with the characteristic kinked tail, dorsal spine and notch feature (Guilhon and Cens 1973). FLOTAC, an improved flotation-based coproscopic method, also allows for the visualisation of A. vasorum L1 in faecal samples, with a good sensitivity (Schnyder et al. 2011a). However, due to prepatency, intermittent larval excretion and the possible occurrence of mixed lungworm infections, copromicroscopic techniques have limitations concerning sensitivity and specificity. Besides, by the time dogs start to be positive in Baermann or FLOTAC, damage to the lung parenchyma is already present, and recovery is more difficult (Guilhon and Cens 1969; Neff 1971; Dennler et al. 2011). Newly developed diagnostic techniques, such as PCR (Jefferies et al. 2009; Al-Sabi et al. 2010) and serological methods (Schnyder et al. 2011b; Schucan et al. 2012), have been developed to detect infected animals. Serological methods were shown to be highly suitable for both individual and massive screening of dog populations. In fact, A. vasorum serologies require single serum samples instead of repeated faecal samples and allows for rapid detection of infection, shortly before or contemporaneously with patency (Schnyder et al. 2015b).

Regarding the geographical distribution of A. vasorum, southern France (Guilhon and Cens 1969; Bourdeau 1993), south-east England and Wales (Jacobs and Prole 1975; Simpson and Neal 1982) and Denmark (Bolt et al. 1992) were traditionally considered areas with high endemic foci, while sporadic cases were diagnosed all over Europe. Nowadays, A. vasorum has a very heterogeneous distribution with reports suggesting the presence of endemic hotspots in many areas, namely in Croatia (Rajkovic-Janje et al. 2002), Italy (Della Santa et al. 2002; Guardone et al. 2013), Switzerland (Staebler et al. 2005), Germany (Staebler et al. 2005; Barutzki and Schaper 2009), Spain (Segovia et al. 2004; Mañas et al. 2005), Greece (Papazahariadou et al. 2007), Poland (Demiaszkiewicz et al. 2014), Slovakia (Miterpakova et al. 2014), Hungary (Schnyder et al. 2015a) and others. Several hypotheses have been raised to explain this possible expansion, such as increased movements of pet dogs and increased fox populations even in urban areas, suggesting that new areas are open to colonisation (Morgan et al. 2009).

In Portugal, knowledge concerning the current situation of A. vasorum infection in domestic and wild canids is poor. No studies conducted so far showed positive results, and no surveillance mechanisms are in place to assess its prevalence or geographical range. A. vasorum was first identified during the necropsy of one of 306 red foxes (Vulpes vulpes silacea) collected between 1970–1987, mostly from the coastal central and southern regions of Portugal, (Carvalho-Varela and Marcos 1993) and more recently, in the littoral centre of Portugal, with a prevalence of 16.1 % (Eira et al. 2006). Excluding foxes, A. vasorum was sporadically identified in domestic dogs, with three positive cases diagnosed in the last few years in the Lisbon area (Madeira de Carvalho et al. 2009, 2013; Nabais et al. 2014). A serological study using a commercial A. vasorum antigen kit (Angio DetectTM Test, IDEXX Laboratories) tested negative on the 120 surveyed dogs from the Algarve region (Maia et al. 2015).

The present serological study aimed to increase the knowledge about the occurrence and geographical dispersion of A. vasorum infections in Portugal.

Material and methods

A total of 906 shelter dogs randomly distributed from north to south of mainland Portugal were studied. All animals were stray dogs, and no information was available regarding previous preventive treatments. Blood samples (2–3 ml) were collected from the cephalic vein, and serum was separated by centrifugation and stored at −20 °C until use. Sera were tested at the Institute of Parasitology, Vetsuisse Faculty, University of Zurich, Switzerland, for the presence of circulating A. vasorum antigens using monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies in a sandwich ELISA, with a sensitivity of 95.7 % and a specificity of 94.0 %, as previously described (Schnyder et al. 2011b). Additionally, a sandwich ELISA (sensitivity 81.0 %, specificity 98.8 %) using A. vasorum adult somatic antigen purified by monoclonal antibodies (mAb Av 5/5) was used for specific antibody detection (Schucan et al. 2012). Test thresholds (Schnyder et al. 2013a) were regionally determined with 300 randomly selected samples based on the mean value of optical density (A405 nm) plus three standard deviations. All test runs included a background control, a conjugate control, three positive control sera from three experimentally infected dogs and two negative control sera from uninfected dogs.

The collected data were analysed using a geographical information system (GIS) program (RegioGraph 10, GfK GeoMarketing, Bruchsal, Germany) to visualise the regional distribution of collected and analysed serum samples and A. vasorum antigen- and/or antibody-positive samples. The locations of positive samples were displayed on maps with administrative and postcode boundaries based on the Portuguese four-digit postcode as points of reference. Excel 2007 for Windows (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, USA) was used to calculate the prevalence values and their 95 % confidence interval (CI).

Results

A total of 0.66 % of the dogs (n = 6, 95 % CI 0.24–1.43) were positive for both A. vasorum antigen and antibody detection, and 12 dogs (1.32 %, 95 % CI 0.68–2.30) were A. vasorum antibody-positive only. Additionally, a total of 1.99 % (n = 18, 95 % CI 1.18–3.12) of the dogs were A. vasorum antigen-positive only (Table 1).

Table 1.

Serological results of 906 dog samples from Portugal tested for the presence of A. vasorum circulating antigens and for specific antibodies against A. vasorum

| Positive samples (n) | Percentage (%) | 95 % confidence intervals | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody-positive | 18 | 1.99 | 1.18–3.12 |

| Antibody-positive only | 12 | 1.32 | 0.68–2.30 |

| Antigen-positive | 24 | 2.65 | 1.70–3.92 |

| Antigen-positive only | 18 | 1.99 | 1.18–3.12 |

| Antibody- and antigen-positive | 6 | 0.66 | 0.24–1.43 |

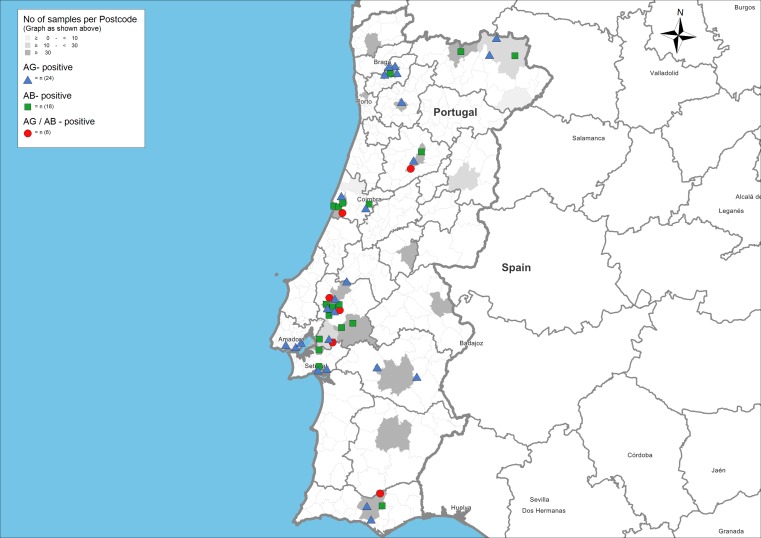

Regions with antigen- and antibody-positive animals overlapped and were distributed over nearly all sampled areas in the country (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Occurrence of Angiostrongylus vasorum detected by ELISA in 906 dogs from Portugal. Dark grey areas represent the origin of the tested dog sera. Dogs positive for antigen and antibody are represented by red dots, dogs positive only for antibody are represented by green squares and dogs positive only for antigen are represented by blue triangles

Discussion

Positive dogs for both ELISAs were detected in the north, centre and southern areas of Portugal, indicating an active infection widely distributed throughout the sampled area. The endemic occurrence of A. vasorum in dogs from different geographical areas of Portugal is therefore confirmed. Interestingly, A. vasorum was nearly absent in the central-eastern part of the country that borders Spain. Howbeit, the lack of evidence of A. vasorum in certain regions of Portugal does not ensure its non-existence, and thus, geographical location should not be used as the unique criterion to suspect or rule out this diagnosis.

With 0.66 % of the examined dogs being positive in both ELISAs, the prevalence in Portugal is apparently higher than that found for Germany (Schnyder et al. 2013a) or Poland (Schnyder et al. 2013b) and lower than in Hungary (Schnyder et al. 2015a), UK (Schnyder et al. 2013a) and Italy (Guardone et al. 2013), but not significantly. Nevertheless, it is important to highlight that this study surveyed shelter dogs, i.e., stray dogs usually not under any kind of prophylaxis and therefore frequently demonstrating higher parasitic prevalence (Alho et al. 2014).

Approximately 2 % of the dogs were positive for specific antibodies against A. vasorum, indicating parasite exposure: these dogs may have been sampled between 3 and 6 weeks after an A. vasorum infection, when antigen detection is still negative (first positive results between 7 and 11 weeks after infection), or the dogs were parasite-free but still antibody-positive after anthelmintic treatment or natural clearance of the infection (Table 1) (Schnyder et al. 2015b).

The results herein presented confirm the endemic occurrence of A. vasorum in dogs from different geographical areas of Portugal and may support the hypothesis of a gradual progression of A. vasorum in Portugal, since the prevalence of this parasite in red fox necropsies have also increased, from 0.3 % between 1970 and 1987 to 16.1 % between 2000 and 2006 (Carvalho-Varela and Marcos 1993; Eira et al. 2006). Several recent studies from other European countries such as Germany, Hungary, Switzerland, Great Britain or Italy illustrate the highly successful establishment of A. vasorum in the last decades. Although the reasons for this impressive success are not fully understood, a similar success within Portugal cannot be excluded. The occurrence of A. vasorum is linked to the presence of final hosts, among which red foxes represent powerful reservoirs and spreaders of this parasite, as indicated by higher prevalence in foxes compared to dogs (summarised in Koch and Willesen 2009). In fact, red foxes are the most widespread European wild canid (Otranto et al. 2015), greatly dispersed also all over the Iberian Peninsula (Macdonald and Reynolds 2008). This, in the absence of obvious geographic barriers, plays an important role in the expansion and establishment of A. vasorum, possibly explaining the high prevalence of this parasite detected in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in Portugal (Eira et al. 2006) and throughout Spain (Barbosa et al. 2005; Mañas et al. 2005; Gerrikagoitia et al. 2010). Also, the potential role of the wolf (Canis lupus) as a wild reservoir of A. vasorum can be mentioned based on a prevalence of 1.9–2.1 % reported in wolves from Spain (Segovia et al. 2001, 2007). Finally, the prevalence found in our study might be also explained by the results obtained in a pet owners’ questionnaire performed in Portugal, where it was shown that although the majority of the owners give antiparasitic drugs to their dogs, this often occurs at irregular and consequently ineffective intervals, with only 11.8 % of the dogs following the recommended endoparasitic treatment and only 28.4 % uninterruptedly protected throughout the year from canine vector borne diseases (European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites (ESCCAP 2016); Matos et al. 2015).

Interestingly, a simulation based on the observed distribution of A. vasorum in Europe and eco-climatic similarities predicted highly suitable areas in the north of Portugal and no suitability in the centre and southern part of the country (Morgan et al. 2009). Indeed, climate may play an important role in A. vasorum transmission, as the population dynamics and the activity of intermediate host species are highly dependent on temperature and moisture conditions. The north of Portugal is usually characterised by average low temperatures and high humidity in contrast to the south, where temperatures are frequently higher with lower humidity. Nevertheless, the slugs Arion rufus and Deroceras laeve, two gastropods known as intermediate hosts of A. vasorum, have already been described in distinct parts of the Portuguese territory (Grewal et al. 2003; Bank 2011).

To conclude, positive cases detected in such distinct areas of Portugal suggest that this parasite is now widespread in endemic foci over nearly the whole country. Since there have been only few studies in Portugal, it is not clear if the epidemiological situation in the country is stable or if it is moving.

Despite the complexity and challenges involved in diagnosing A. vasorum infection, when early detection and prompt-targeted therapy are undertaken, prognosis is good. Considering the impact of this disease on the health of affected dogs, it is thus important to increase knowledge concerning the epidemiological situation of this potentially fatal parasite. We believe that these results will be crucial to raise the awareness of veterinary practitioners, ensuring routine screenings of lungworms in dogs, and a well-timed diagnosis and treatment. Furthermore, we hope this data will contribute to highlight the importance of owner’s education in order to adopt behaviours that minimise the risk of infection.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the public and private animal shelters involved in this study, as well as to their employees and local veterinarians for their extremely valuable help, and also to Markus Reule for his precious help with the geographic information system analysis.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

A.M. Alho, M. Schnyder, J. Meireles, S. Belo, P. Deplazes and L.M. Carvalho declare no conflict of interest. R. Schaper is employed by Bayer Animal Health.

Funding

PhD research grant SFRH/BD/85427/2012; Project UID/CVT/00276/2013 supported by CIISA-FMV-ULisboa, Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT), Portugal. This work was done under the frame of EurNegVec COST Action TD1303.

Ethical standards

All institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals were followed.

References

- Alho AM, Landum M, Ferreira C, Meireles J, Gonçalves L, Madeira de Carvalho L, Belo S. Prevalence and seasonal variations of canine dirofilariosis in Portugal. Vet Parasitol. 2014;206(1–2):99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sabi MN, Deplazes P, Webster P, Willesen JL, Davidson RK, Kapel CM. PCR detection of Angiostrongylus vasorum in faecal samples of dogs and foxes. Parasitol Res. 2010;107:135–140. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-1847-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bank RA (2011) Fauna Europaea Project: checklist of the land and freshwater Gastropoda of the Iberian peninsula (Spain, Portugal, Andorra, Gibraltar). http://www.nmbe.ch/sites/default/files/uploads/pubinv/fauna_europaea_-_gastropoda_of_iberian_peninsula.pdf. Accessed 13 January 2016

- Barbosa AM, Segovia JM, Vargas JM, Torres J, Real R, Miquel J. Predictors of red fox (Vulpes vulpes) helminth parasite diversity in the provinces of Spain. Wildl Biol Pract. 2005;1(1):3–14. doi: 10.2461/wbp.2005.1.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barutzki D, Schaper R. Natural infections of Angiostrongylus vasorum and Crenosoma vulpis in dogs in Germany (2007–2009) Parasitol Res. 2009;105(Suppl 1):S39–48. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1494-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolt G, Monrad J, Henriksen P, Dietz HH, Koch J, Bindseil E, Jensen AL. The fox (Vulpes vulpes) as a reservoir for canine angiostrongylosis in Denmark. Field survey and experimental infections. Acta Vet Scand. 1992;33:357–362. doi: 10.1186/BF03547302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdeau P. L’angiostrongylose canine. Receuil Méd Vét. 1993;169:401–407. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho-Varela M, Marcos MVM. A helmintofauna da raposa (Vulpes vulpes silacea Miller, 1907) em Portugal. Acta Parasitol Port. 1993;1(1/2):73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman PS, Boag AK, Guitian J, Boswood A. Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in 23 dogs (1999–2002) J Small Anim Prac. 2004;45:435–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2004.tb00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Santa D, Citi D, Marchetti V, Nardoni S. Infezione da Angiostrongylus vasorum nel cane: review della letteratura e presentazione di un caso clinico. Veterinaria. 2002;16:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Demiaszkiewicz AW, Pyziel AM, Kuligowska I, Lachowicz J. The first report of Angiostrongylus vasorum (Nematoda; Metastrongyloidea) in Poland, in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) Acta Parasitol. 2014;59:758–762. doi: 10.2478/s11686-014-0290-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennler M, Makara M, Kranjc A, Schnyder M, Ossent P, Deplazes P, Ohlerth S, Glaus TM. Thoracic computed tomography findings in dogs experimentally infected with Angiostrongylus vasorum. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2011;52:289–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2010.01776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eira C, Vingada J, Torres J, Miquel J. The helminth community of the red fox, Vulpes vulpes, in Dunas de Mira (Portugal) and its effect on host condition. Wildl Biol Pract. 2006;1:26–36. [Google Scholar]

- European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites (ESCCAP) Guidelines. http://www.esccap.org Accessed 3 January 2016

- Gerrikagoitia X, Barral M, Juste RA. Angiostrongylus species in wild carnivores in the Iberian peninsula. Vet Parasitol. 2010;174:175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal PS, Grewal SK, Tan L, Adams BJ. Parasitism of molluscs by nematodes: types of associations and evolutionary trends. J Nematol. 2003;35(2):146–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guardone L, Schnyder M, Macchioni F, Deplazes P, Magi M. Serological detection of circulating Angiostrongylus vasorum antigen and specific antibodies in dogs from central and northern Italy. Vet Parasitol. 2013;192:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilhon J, Cens B. Migrations and evolution of Angiostrongylus vasorum (Baillet, 1866) in dogs (in French) C R Acad Sci Hebd Seances Acad Sci D. 1969;269:2377–2380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilhon J, Cens B. Angiostrongylus vasorum (Baillet, 1866): Étude biologique et morphologique. Ann Parasitol Hum Comp. 1973;48:567–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm JR, Morgan ER, Jackson MW, Wotton P, Bell R. Canine angiostrongylosis: an emerging disease in Europe. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2010;20(1):98–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-4431.2009.00494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs DE, Prole JH. Angiostrongylus vasorum and other nematodes in British greyhounds. Vet Rec. 1975;96:180. doi: 10.1136/vr.96.8.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies R, Morgan ER, Shaw SE. A SYBR green realtime PCR assay for the detection of the nematode Angiostrongylus vasorum in definitive and intermediate hosts. Vet Parasitol. 2009;166:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch J, Willesen JL. Canine pulmonary angiostrongylosis: an update. Vet J. 2009;179:348–359. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald DW, Reynolds JC (2008) Vulpes vulpes. The IUCN red list of threatened species 2008: e.T23062A9412884. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T23062A9412884.en Accessed 26 January 2016

- Madeira de Carvalho L, Pereira da Fonseca IM, Gomes L, Meireles JM (2009) Lungworms in domestic and wild carnivores in Portugal: rare parasites or rarely diagnosed? ECVIM Congress, Bayer Angiostrongylosis Forum. Porto. Proceedings, pp. 28

- Madeira de Carvalho L, Alho AM, Matos M, Sousa S, Miranda LM, Anastácio S, Otero D, Gomes L, Nunes T, Otranto D, Belo S, Deplazes P. Some emerging canine vector borne diseases and antiparasitic control measures in companion animals in Portugal—recent updates. XVIII Congreso de la Sociedad Española de Parasitologia (SOCEPA), Sep 17–20 2013. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Keynote - CL.3, Proceedings; 2013. p. 100. [Google Scholar]

- Maia C, Coimbra M, Ramos C, Cristovão JM, Cardoso L, Campino L. Serological investigation of Leishmania infantum, Dirofilaria immitis and Angiostrongylus vasorum in dogs from southern Portugal. Parasit Vector. 2015;8:152. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0771-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mañas S, Ferrer D, Castella J, Maria Lopez-Martin J. Cardiopulmonary helminth parasites of red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in Catalonia, northeastern Spain. Vet J. 2005;169:118–120. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos M, Alho AM, Owen SP, Nunes T, Madeira de Carvalho L. Parasite control practices and public perception of parasitic diseases: a survey of dog and cat owners. Prev Vet Med. 2015;122:174–80. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miterpakova M, Hurnikova Z, Zalewski AP. The first clinically manifested case of angiostrongylosis in a dog in Slovakia. Acta Parasitol. 2014;59:661–665. doi: 10.2478/s11686-014-0289-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan ER, Jefferies R, Krajewski M, Ward P, Shaw SE. Canine pulmonary angiostrongylosis: the influence of climate on parasite distribution. Parasitol Int. 2009;58:406–410. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabais J, Alho AM, Gomes L, Ferreira da Silva J, Nunes T, Vicente G, Madeira de Carvalho L. Aelurostrongylus abstrusus in cats and Angiostrongylus vasorum in dogs from Lisbon, Portugal. Acta Parasitol Port. 2014;20(1/2):35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Neff H (1971) Experimentelle Infektionen von Hunden mit Angiostrongylus vasorum (Nematoda). Dissertation, Universität Zürich

- Otranto D, Cantacessi C, Dantas-Torres F, Brianti E, Pfeffer M, Genchi C, Guberti V, Capelli G, Deplazes P. The role of wild canids and felids in spreading parasites to dogs and cats in Europe. Part II: helminths and arthropods. Vet Parasitol. 2015;213(1–2):24–37. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papazahariadou A, Founta A, Papadopoulos E, Chliounakis S, Antoniadou-Sotiriadou K, Theodorides Y. Gastrointestinal parasites of shepherd and hunting dogs in the Serres Prefecture, Northern Greece. Vet Parasitol. 2007;148:170–173. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkovic-Janje R, Marinculic A, Bosnic S, Benic M, Vinkovic B, Mihaljevic Z. Prevalence and seasonal distribution of helminth parasites in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) from the Zagreb County (Croatia) Z Jagdwiss. 2002;48:151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Schnyder M, Maurelli MP, Morgoglione ME, Kohler L, Deplazes P, Torgerson P, Cringoli G, Rinaldi L. Comparison of faecal techniques including FLOTAC for copromicroscopic detection of first stage larvae of Angiostrongylus vasorum. Parasitol Res. 2011;109:63–69. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-2221-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnyder M, Tanner I, Webster P, Barutzki D, Deplazes P. An ELISA for sensitive and specific detection of circulating antigen of Angiostrongylus vasorum in serum samples of naturally and experimentally infected dogs. Vet Parasitol. 2011;179:152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnyder M, Schaper R, Bilbrough G, Morgan ER, Deplazes P. Seroepidemiological survey for canine angiostrongylosis in dogs from Germany and the UK using combined detection of Angiostrongylus vasorum antigen and specific antibodies. Parasitology. 2013;140:1442–1450. doi: 10.1017/S0031182013001091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnyder M, Schaper R, Pantchev N, Kowalska D, Szwedko A, Deplazes P. Serological detection of circulating Angiostrongylus vasorum antigen- and parasite-specific antibodies in dogs from Poland. Parasitol Res. 2013;112(Suppl 1):109–117. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnyder M, Schaper R, Lukács Z, Hornok S, Farkas R. Combined serological detection of circulating Angiostrongylus vasorum antigen and parasite-specific antibodies in dogs from Hungary. Parasitol Res. 2015;114(Suppl 1):S145–S154. doi: 10.1007/s00436-015-4520-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnyder M, Jefferies R, Schucan A, Morgan ER, Deplazes P. Comparison of coprological, immunological and molecular methods for the detection of dogs infected with Angiostrongylus vasorum before and after anthelmintic treatment. Parasitology. 2015;142:1270–1277. doi: 10.1017/S0031182015000554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schucan A, Schnyder M, Tanner I, Barutzki D, Traversa D, Deplazes P. Detection of specific antibodies in dogs infected with Angiostrongylus vasorum. Vet Parasitol. 2012;185:216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segovia JM, Torres J, Miquel J, Llaneza L, Feliu C. Helminths in the wolf, Canis lupus, from north-western Spain. J Helminthol. 2001;75(2):183–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segovia JM, Torres J, Miquel J. Helminth parasites of the red fox (Vulpes vulpes L., 1758) in the Iberian Peninsula: an ecological study. Acta Parasitol. 2004;49:67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Segovia JM, Miquel J, Torres J, Feliu C. Role of satellite species in helminth communities of the Iberian wolf (Canis Lupus Signatus Cabrera, 1907) Rev Iber Parasitol. 2007;67(1–4):79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson VR, Neal C. Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in dogs and slugs. Vet Rec. 1982;111:303–304. doi: 10.1136/vr.111.13.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staebler S, Ochs H, Steffen F, Naegeli F, Borel N, Sieber-Ruckstuhl N, Deplazes P. Autochthonous infections with Angiostrongylus vasorum in dogs in Switzerland and Germany (in German) Schweiz Arch Tierheilkde. 2005;147:121–127. doi: 10.1024/0036-7281.147.3.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessmann A, Lu D, Lamb CR, Smyth B, Mantis P, Chandler K, Boag A, Cherubini GB, Cappello R. Brain and spinal cord haemorrhages associated with Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in four dogs. Vet Rec. 2006;158:858–863. doi: 10.1136/vr.158.25.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]