Abstract

This study reports the increasing prevalence of clinical Escherichia coli of sequence type 167 (ST167) carrying both blaNDM-1 and blaNDM-5 on the conjugative IncX3 plasmid in various parts of China. Close surveillance is needed to monitor the future dissemination of ST167 strains that harbor blaNDM-5 or other blaNDM-like genes.

TEXT

The continuous emergence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) strains in recent years has posed an increasing public health threat worldwide. The dissemination of mobile resistance elements, especially those carrying the New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase gene (blaNDM-1), has been regarded as a major mechanism responsible for causing a dramatic increase in the prevalence of CRE in clinical settings. NDM-producing organisms were first reported on the Indian subcontinent and then in several Middle Eastern and Balkan countries in 2009 (1, 2). This gene has since spread to different species of Enterobacteriaceae and other Gram-negative bacteria throughout the world (3). The rapid increase in the prevalence of CRE may be due to both transmission of blaNDM-1-carrying elements among the Enterobacteriaceae species and clonal spread of strains containing such elements (4, 5). Current evidence, however, suggests that the transmission of specific mobile resistance elements in CRE has a strong association with specific types of bacterial strains. For example, the blaNDM-1-like genes are predominantly detected in multilocus sequence typing (MLST) sequence type 131 (ST131) and ST101 strains of Escherichia coli and ST11 strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae (5–8). The underlying mechanisms leading to the clustering of the blaNDM-1-like genes in specific STs remain to be investigated.

In China, blaNDM-1 was reported in 2011 (9). Since then, the gene has become detectable in most species of Enterobacteriaceae in various cities in China, and yet, there is a lack of information on the linkage of specific STs of E. coli to blaNDM-1 carriage due to the sporadic and noncomprehensive nature of CRE-related data in China. Recently, four studies have reported several sporadic cases of clinical infections linked to E. coli ST167 carrying blaNDM-5 in various parts of China (10–12). The gene was shown to be located on the IncX3 plasmid in two studies (11, 12).

In this work, we have conducted a more comprehensive investigation in order to better understand whether the E. coli ST167 strains are predominantly involved in the transmission of the blaNDM-1 and blaNDM-5 genes in hospitals in various parts of China. Clinical carbapenem-resistant E. coli strains, as determined by the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method according to CLSI guidelines, were obtained from 7 hospitals in various locations in China, as shown in Table 1, from 2013 to 2014. A total of 48 carbapenem-resistant E. coli isolates were obtained during the study period and screened for the presence of blaNDM-1 as previously described (13). Twenty-five (52%) were found to carry blaNDM carbapenemase genes, among which 11 were isolated from patients in hematology departments, 4 from patients in intensive care units (ICUs), 4 from patients in pediatric surgery, 4 from patients in recovery departments, and the others from patients in burn departments and intensive medicine. Of these 25 isolates, 13 were recovered from blood samples and the others were recovered from urine or secretion samples.

TABLE 1.

Profiles of plasmids and β-lactamase genes recoverable in 25 blaNDM-positive E. coli clinical isolates and the corresponding transconjugants

| Isolatea | MLST | β-Lactamase gene(s) in: |

Estimated size(s) (kb) of plasmid(s) inb: |

Plasmid type in transconjugantc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental strain | Transconjugant | Parental strain | Transconjugant | |||

| SY91 | 167 | blaNDM-5, blaCTX-M-14 | blaNDM-5 | 280, 160, 110, 60 | 60 | IncX3 |

| SY92 | 167 | blaNDM-5, blaCTX-M-14 | blaNDM-5 | 280, 160, 110, 60 | 60 | IncX3 |

| SY93 | 167 | blaNDM-5, blaCTX-M-14 | blaNDM-5 | 280, 135, 60 | 60 | IncX3 |

| JN102 | 167 | blaNDM-5, blaCTX-M-14, blaCTX-M-15, blaTEM-1 | blaNDM-5, blaTEM-1 | 110, 90, 60 | 60 | IncX3 |

| JN105 | 167 | blaNDM-5, blaCTX-M-15, blaTEM-1 | blaNDM-5, blaTEM-1 | 160,135, 100, 60 | 65 | IncX3 |

| JN106 | 167 | blaNDM-5, blaCTX-M-15, blaTEM-1 | blaNDM-5, blaTEM-1 | 160,135, 100, 60 | 60 | IncX3 |

| BJ114 | 167 | blaNDM-5, blaCTX-M-14 | blaNDM-5, blaCTX-M-14 | 160, 100,80, 60 | 200 | IncX3 |

| LZ135 | 167 | blaNDM-5, blaCTX-M-15 | blaNDM-5 | 150, 100 | 105, 100, 90 | IncFrepB |

| JN103 | 167 | blaNDM-1, blaCTX-M-14, blaCTX-M-15, blaTEM-1 | blaNDM-1, blaTEM-1 | 200, 160, 110 | 160 | UT |

| SRM94 | 167 | blaNDM-1, blaTEM-1 | blaNDM-1, blaTEM-1 | 160 | 160 | IncF |

| JX6 | 167 | blaNDM-1, blaCTX-M-14, blaTEM-1, blaSHV-12 | blaNDM-1, blaTEM-1, blaSHV-12 | 110, 100, 60 | 65 | IncX3 |

| JX34 | 167 | blaNDM-1, blaCTX-M-15, blaTEM-1, blaSHV-12 | blaNDM-1, blaTEM-1, blaSHV-12 | 210, 110, 60 | 60 | IncX3 |

| BJ119 | 405 | blaNDM-5, blaCTX-M-15 | blaNDM-5 | 130,70,60 | 60 | IncX3 |

| SRM282 | 533 | blaNDM-5, blaCTX-M-14 | blaNDM-5 | 200, 120, 60 | 60 | IncX3 |

| WH97 | 410 | blaNDM-1, blaCTX-M-14, blaCTX-M-15 | blaNDM-1, blaCTX-M-14 | 100, 75, 60 | 60 | IncN |

| JX45 | 359 | blaNDM-1, blaCTX-M-15, blaTEM-1, blaSHV-12 | blaNDM-1, blaTEM-1, blaSHV-12 | 160, 100, 60 | 60 | IncX3 |

| WH32 | 1284 | blaNDM-1 | blaNDM-1 | 160, 68 | 230 | IncN |

| SY96 | 2749 | blaNDM-1, blaCTX-M-15 | blaNDM-1 | 240, 170, 60 | 330, 60 | IncN |

| SRM251 | 3489 | blaNDM-1, blaSHV-12 | blaNDM-1, blaSHV-12 | 165, 60, 48 | 60 | IncX3 |

| BJ128 | 5699 | blaNDM-1, blaCTX-M-14 | blaNDM-1, blaCTX-M-14 | 200,100,80 | 200 | UT |

| LZ136 | 167 | blaNDM-5, blaCTX-M-15, blaTEM-1 | 150, 90 | NC | ||

| JX33 | 167 | blaNDM-1, blaCTX-M-15 | 160, 125, 100 | NC | ||

| BJ116 | 101 | blaNDM-3, blaCTX-M-15 | 165, 90, 85 | NC | ||

| WH36 | 1284 | blaNDM-1 | 200 | NC | ||

| SRM49 | 5138 | blaNDM-1, blaCTX-M-14, blaTEM-1 | 155, 125, 100, 80 | NC | ||

Isolate identification codes indicate the source of the isolate as follows: WH, Wuhan, capital city of Hubei Province; SY, Shenyang, capital city of Liaoning Province; JX, Jiaxing, city of Zhejiang Province; LZ, Lanzhou, capital city of Gansu Province; JN, Jinan, capital city of Shandong Province; SMR, People's Hospital of Zhejiang Province in Hangzhou, capital of Zhejiang Province; BJ, Beijing.

Plasmids harboring blaNDM genes are denoted in boldface. NC, nonconjugative.

UT, untypeable.

These 25 E. coli isolates were subjected to further characterization by PCR and sequencing as previously described to determine the exact type of β-lactamase genes harbored by these isolates (13). The blaNDM-like genes in 13 isolates were confirmed to be blaNDM-1, and blaNDM-5 was found to be present in 11 isolates, whereas blaNDM-3 was detected in one strain. Other β-lactamase genes, such as those encoding CTX-M-14, CTX-M-15, SHV-12, and TEM-1, were also frequently detected in various strains (Table 1). The MICs of 10 antibiotics, including imipenem, meropenem, ceftazidime, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, amikacin, tobramycin, polymyxin B, cefoperazone-sulbactam, fosfomycin, aztreonam, levofloxacin, and ciprofloxacin, were determined for these isolates using the agar dilution method, and the results were analyzed according to the CLSI criteria of 2014 (14). All 25 blaNDM-1-positive isolates were found to be resistant to most β-lactam antibiotics, including extended-spectrum cephalosporins and the carbapenems. The MICs for imipenem and meropenem were between 4 and 64 μg/ml. These isolates were also resistant to fluoroquinolones (100%), aztreonam (88%), tobramycin (64%), amikacin (32%), and fosfomycin (16%). All isolates were susceptible to polymyxin B.

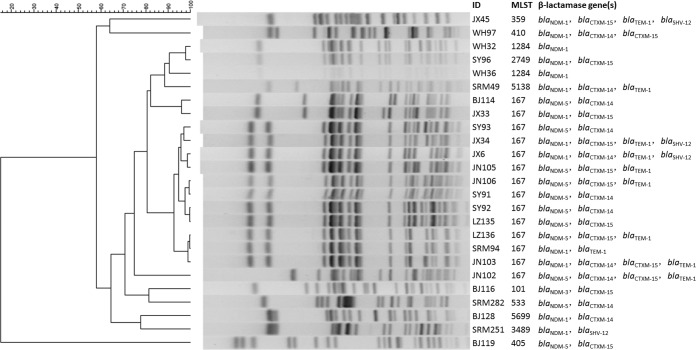

To assess the genetic relatedness of these 25 isolates, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and sequence typing were performed as previously described (13). Fourteen of the 25 isolates belonged to ST167, among which 11 exhibited very similar, although not identical PFGE patterns, while 3 showed different PFGE patterns (Fig. 1). Other strains belonged to 9 other STs and displayed very diverse PFGE patterns, suggesting that these E. coli strains were not genetically related to each other even though a number of strains were recovered from the same hospital (Fig. 1). Among the 11 blaNDM-5-positive isolates, 9 were associated with ST167, while 2 were associated with ST405 and ST533, respectively, suggesting the tight association of ST167 and blaNDM-5. On the other hand, 5 ST167 E. coli strains were found to carry blaNDM-1, and the isolate which harbored the blaNDM-3 gene was found to belong to ST101.

FIG 1.

PFGE patterns of 25 blaNDM-positive clinical E. coli isolates.

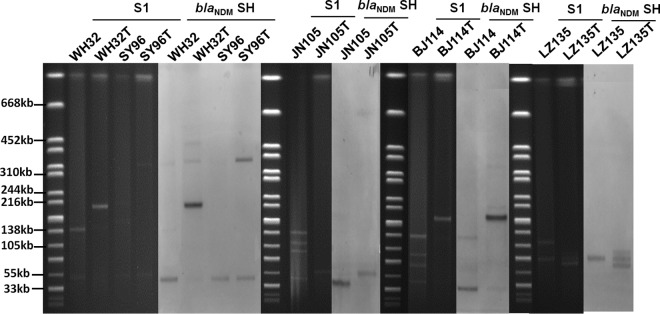

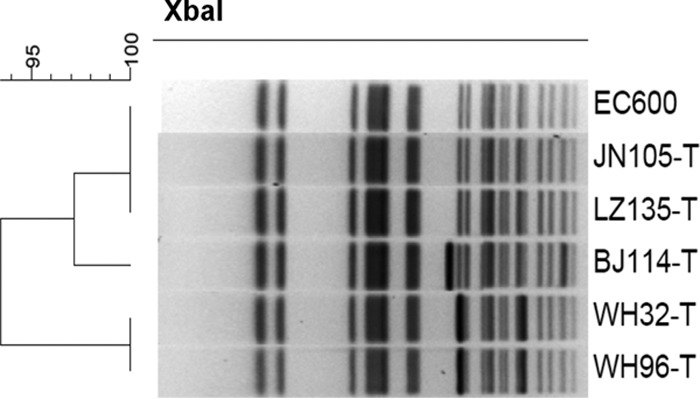

Conjugation experiments were performed for these 25 isolates as previously described (13). Twenty of the 25 isolates tested could successfully transfer their carbapenem-resistant phenotype to E. coli strain J53. In addition to the resistance to carbapenems, 1, 2, 2, 3, and 6 of the 20 transconjugants also exhibited resistance to fosfomycin, fluoroquinolone, amikacin, tobramycin, and aztreonam, respectively. S1 nuclease digestion combined with PFGE (S1-PFGE) and Southern hybridization were performed on the parental strains and their corresponding transconjugants to identify the blaNDM-1- and blaNDM-5-bearing plasmids concerned. Multiple plasmids with sizes ranging from ∼48 kb to ∼280 kb were detected in the parental strains, with blaNDM-1 and blaNDM-5 being predominantly located on an ∼60-kb plasmid. However, several plasmids of various sizes were also found to carry blaNDM-1 and blaNDM-5 (Table 1). Among the 20 transconjugants, most were found to harbor one plasmid, with the ∼60-kb conjugative plasmid being the most prevalent (Table 1). Transconjugants from strains LZ135 and SY96 were found to carry more than one blaNDM-encoding plasmid, with one being transferred from the parental strain and one or two new plasmids not being detectable in the parental strain (Table 1; Fig. 2). Some transconjugants were found to harbor blaNDM-encoding plasmids with different sizes than those from the parental strains, such as parental strains BJ114, WH32, and LZ135 (Table 1; Fig. 2). To doubly confirm that these transconjugants were correct, PFGE was performed on them, together with the recipient strain E. coli EC600. The results indicated that these transconjugants were indeed E. coli EC600; the large blaNDM-encoding plasmids were obvious on some of them, such as BJ114-T, WH32-T, and WH96-T, while the transconjugants carrying small blaNDM-encoding plasmids, such as LZ135-T and JN105-T, showed PFGE profiles identical to that of E. coli EC600, suggesting that the PFGE data for these transconjugants was consistent with the S1-PFGE and Southern hybridization data (Fig. 3). This phenomenon could be due to the recombination events between the blaNDM-1-positive and -negative plasmids present in the parental strains or the repetition of multiple copies of one mobile element (unpublished observation on plasmids from other bacteria in our laboratory). The incompatibility groups of the detectable plasmids were determined by PCR replicon typing as previously described (14). Most of the conjugative plasmids were of the IncX3 type, with a size of ∼60 kb. Other types included IncN (3 plasmids), FrepB (1 plasmid), IncF (1 plasmid), and untypeable (2 plasmids) (Table 1). Most of the blaNDM-5-bearing plasmids belonged to the IncX3 types, of which seven were harbored by the ST167 strains and one each was harbored by an ST405 and an ST533 strain. One blaNDM-5 gene was found to be located on a FrepB plasmid in an ST167 strain, and one was in a nonconjugative plasmid in an ST167 strain. The blaNDM-1-bearing plasmids in five ST167 strains included IncX3 (2 plasmids), IncF (1 plasmid), and untypeable (1 plasmid) conjugative plasmids and one nonconjugative plasmid (Table 1).

FIG 2.

S1-PFGE (S1) and Southern hybridization (blaNDM SH) of representative blaNDM-positive E. coli clinical isolates and the corresponding transconjugants. Uppercase Ts denote transconjugants; the strain identification codes are described in Table 1.

FIG 3.

Comparison of PFGE profiles of transconjugants carrying different sizes of plasmids from their parental strains to the PFGE profile of the recipient strain, E. coli EC600.

All conjugative plasmids were screened for their similarity to previously reported IncX3 plasmids, as shown in Table 2. Our screening data showed that all IncX3 blaNDM-positive plasmids were positive for repB, topB-ftsH, and bleo-blaNDM-1, some of which harbored the blaSHV-2 gene (positive for ISL3 tnpA-blaSHV-2). Plasmids of the other types were only positive for bleo-blaNDM-1. The data suggested that all plasmids, including IncX3 types and other types, carried the conserved fragment blaNDM-1-bleMBL-trpF.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of conjugative plasmids carried by the 20 transconjugants

| Transconjuganta | Result of screening forb: |

Estimated plasmid size(s) (bp) | Plasmid typec | β-Lactamase gene(s) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repB | ISL3-blaSHV-12 | bleo-blaNDM-1 | blaNDM-1-insH | topB-ftsH | ||||

| SY91-T | + | + | + | 60 | IncX3 | blaNDM-5 | ||

| SY92-T | + | + | + | 60 | IncX3 | blaNDM-5 | ||

| SY93-T | + | + | + | 60 | IncX3 | blaNDM-5 | ||

| JN102-T | + | + | + | 60 | IncX3 | blaNDM-5, blaTEM-1 | ||

| JN105-T | + | + | + | 65 | IncX3 | blaNDM-5, blaTEM-1 | ||

| JN106-T | + | + | + | 60 | IncX3 | blaNDM-5, blaTEM-1 | ||

| BJ114-T | + | + | + | 200 | IncX3 | blaNDM-5, blaCTX-M-14 | ||

| LZ135-T | + | 105, 100, 90 | IncFrepB | blaNDM-5 | ||||

| JN103-T | + | + | 160 | UT | blaNDM-1, blaTEM-1 | |||

| SRM94-T | + | 160 | IncF | blaNDM-1, blaTEM-1 | ||||

| JX6-T | + | + | + | + | + | 65 | IncX3 | blaNDM-1, blaTEM-1, blaSHV-12 |

| JX34 | + | + | + | + | + | 60 | IncX3 | blaNDM-1, blaTEM-1, blaSHV-12 |

| BJ119-T | + | + | + | 60 | IncX3 | blaNDM-5 | ||

| SRM282-T | + | + | + | 60 | IncX3 | blaNDM-5 | ||

| WH97-T | + | 60 | IncN | blaNDM-1, blaCTX-M-14 | ||||

| LX45-T | + | + | + | + | + | 60 | IncX3 | blaNDM-1, blaTEM-1, blaSHV-12 |

| WH32-T | + | + | 230 | IncN | blaNDM-1 | |||

| SY96-T | + | 330, 60 | IncN | blaNDM-1 | ||||

| SRM251-T | + | + | + | + | + | 60 | IncX3 | blaNDM-1, blaSHV-12 |

| BJ128-T | + | 200 | UT | blaNDM-1, blaCTX-M-14 | ||||

Identification codes are described in Table 1; the uppercase Ts denote transconjugants.

Primers were designed based on the IncX3 plasmid, namely, pNDM-HN380 (NC_019162). Primers targeting repB (positions 54029 to 1127) and topB-ftsH (positions 28908 to 33069) were used to screen for X3-specific conjugative plasmids, the primer targeting ISL3 tnpA-blaSHV-2 (positions 4395 to 8093) was used to screen for the blaSHV-2 gene, the primer targeting bleo-blaNDM-1 (positions 17,418 to 18,100) was used to screen for the conservative blaNDM-1 mobile element, and the primer targeting blaNDM-1-insH (positions 17768 to 20103) was used to screen for the upstream transposase gene.

UT, untypeable.

In summary, this study provides strong evidence that ST167 strains in clinical settings in China exhibited close linkages with blaNDM genes, and particularly, a blaNDM-5 variant with higher hydrolytic activity than blaNDM-1. Close surveillance is needed to monitor future dissemination of ST167 strains that harbor the blaNDM-like genes in China and other parts of the world.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the team of curators of the Institute Pasteur MLST and whole-genome MLST databases for curating the data and making them publicly available at http://bigsdb.web.pasteur.fr. We extend special thanks to the hospitals which kindly provided the reference strains.

The authors have no conflicts to declare.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the Chinese National Key Basic Research and Development (973) Program (2013CB127200).

REFERENCES

- 1.Kumarasamy KK, Toleman MA, Walsh TR, Bagaria J, Butt F, Balakrishnan R, Chaudhary U, Doumith M, Giske CG, Irfan S, Krishnan P, Kumar AV, Maharjan S, Mushtaq S, Noorie T, Paterson DL, Pearson A, Perry C, Pike R, Rao B, Ray U, Sarma JB, Sharma M, Sheridan E, Thirunarayan MA, Turton J, Upadhyay S, Warner M, Welfare W, Livermore DM, Woodford N. 2010. Emergence of a new antibiotic resistance mechanism in India, Pakistan, and the UK: a molecular, biological, and epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis 10:597–602. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70143-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yong D, Toleman MA, Giske CG, Cho HS, Sundman K, Lee K, Walsh TR. 2009. Characterization of a new metallo-β-lactamase gene, blaNDM-1, and a novel erythromycin esterase gene carried on a unique genetic structure in Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 14 from India. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:5046–5054. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00774-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marra A. 2011. NDM-1: a local clone emerges with worldwide aspirations. Future Microbiol 6:137–141. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lascols C, Hackel M, Marshall SH, Hujer AM, Bouchillon S, Badal R, Hoban D, Bonomo RA. 2011. Increasing prevalence and dissemination of NDM-1 metallo-beta-lactamase in India: data from the SMART study (2009). J Antimicrob Chemother 66:1992–1997. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sonnevend A, Al Baloushi A, Ghazawi A, Hashmey R, Girgis S, Hamadeh MB, Al Haj M, Pal T. 2013. Emergence and spread of NDM-1 producer Enterobacteriaceae with contribution of IncX3 plasmids in the United Arab Emirates. J Med Microbiol 62:1044–1050. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.059014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pannaraj PS, Bard JD, Cerini C, Weissman SJ. 2015. Pediatric carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Los Angeles, California, a high-prevalence region in the United States. Pediatr Infect Dis J 34:11–16. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peirano G, Schreckenberger PC, Pitout JD. 2011. Characteristics of NDM-1-producing Escherichia coli isolates that belong to the successful and virulent clone ST131. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:2986–2988. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01763-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giske CG, Froding I, Hasan CM, Turlej-Rogacka A, Toleman M, Livermore D, Woodford N, Walsh TR. 2012. Diverse sequence types of Klebsiella pneumoniae contribute to the dissemination of blaNDM-1 in India, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:2735–2738. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06142-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y, Zhou Z, Jiang Y, Yu Y. 2011. Emergence of NDM-1-producing Acinetobacter baumannii in China. J Antimicrob Chemother 66:1255–1259. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang L-P, Xue W-C, Meng D-Y. 2016. First report of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase 5 (NDM-5)-producing Escherichia coli from blood cultures of three leukemia patients. Int J Infect Dis 42:45–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang P, Xie Y, Feng P, Zong Z. 2014. blaNDM-5 carried by an IncX3 plasmid in Escherichia coli sequence type 167. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:7548–7552. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03911-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen D, Gong L, Walsh TR, Lan R, Wang T, Zhang J, Mai W, Ni N, Lu J, Xu J, Li J. 2016. Infection by and dissemination of NDM-5-producing Escherichia coli in China. J Antimicrob Chemother 71:563–565. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang X, Chen G, Wu X, Wang L, Cai J, Chan EW, Chen S, Zhang R. 2015. Increased prevalence of carbapenem resistant Enterobacteriaceae in hospital setting due to cross-species transmission of the blaNDM-1 element and clonal spread of progenitor resistant strains. Front Microbiol 6:595. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carattoli A, Bertini A, Villa L, Falbo V, Hopkins KL, Threlfall EJ. 2005. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. J Microbiol Methods 63:219–228. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]