Abstract

Background: Silicosis is a fatal and fibrotic pulmonary disease caused by the inhalation of silica. After arriving at the alveoli, silica is ingested by alveolar macrophages (AMOs), in which monocyte chemotactic protein-induced protein 1 (MCPIP1) plays an essential role in controlling macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses. However, the mechanism of action of MCPIP1 in silicosis is poorly understood. Methods: Primary rat AMOs were isolated and treated with SiO2 (50 µg/cm2). MCPIP1 and AMO activation/apoptosis markers were detected by immunoblotting. MCPIP1 was down-regulated using siRNA in AMOs. The effects of AMOs on fibroblast activation and migration were evaluated using a gel contraction assay, a scratch assay, and a nested collagen matrix migration model.

Results: After exposure to SiO2, MCPIP1 was significantly increased in rat AMOs. Activation and apoptosis markers in AMOs were up-regulated after exposure to SiO2. Following siRNA-mediated silencing of MCPIP1 mRNA, the markers of AMO activation and apoptosis were significantly decreased. Rat pulmonary fibroblasts (PFBs) cultured in conditional medium from AMOs treated with MCPIP1 siRNA and SiO2 showed significantly less activation and migration compared with those cultured in conditional medium from AMOs treated with control siRNA and SiO2. Conclusion: Our data suggest a vital role for MCPIP1 in AMO apoptosis and PFB activation/migration induced by SiO2.

Keywords: silicosis, macrophage, fibroblast, MCPIP1, apoptosis.

Silicosis is one of the most serious occupational diseases worldwide and is caused by the inhalation of silica. The pathogenic characteristics of silicosis are chronic inflammation and late pulmonary fibrosis. Even when the patient is no longer exposed to silica, lung function impairment increases with disease progression (Leung et al., 2012).

Previous studies have shown that alveolar macrophages (AMOs) and pulmonary fibroblasts (PFBs) are the effector cells of silicosis (Liu et al., 2015b). AMOs are the most important immune barrier against invading pathogens and environmental contaminants in pulmonary innate immunity. When dust particles and bacteria in the air reach the alveoli, they are captured and eliminated by AMOs. After ingesting silica particles, AMOs become activated and release inflammatory mediators, such as reactive oxygen species, reactive nitrogen, chemokines, cytokines, and growth factors (Fujimura, 2000; Mossman and Churg, 1998). These substances may impair pulmonary tissues and stimulate fibroblast proliferation, leading to fibrotic reactions. Activated AMOs cannot clear silica but are induced to undergo apoptosis. Accumulating data have indicated that AMO apoptosis is an underlying mechanism for the development of silicosis (Borges et al., 2001; Gu et al., 2013; Lim et al., 1999).

Chemokine (C–C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2/MCP-1) is an inflammatory mediator secreted by activated AMOs that plays a pivotal role in silicosis by recruiting C–C chemokine receptor type 2-expressing inflammatory monocytes to mediate pulmonary inflammatory reactions and induce the late fibrogenic reaction (Zhou et al., 2006). Recently studies from our lab suggest that CCL2 plays a critical role in SiO2-induced pulmonary fibrosis (Liu et al., 2015b). Moreover, CCL2 expression is increased in both the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid from patients and the supernatant of cultured AMOs (Wang et al., 2015). However, the downstream mechanisms of action of CCL2 remain unclear. Monocyte chemotactic protein-induced protein 1 (MCPIP1) is a novel CCCH zinc-finger-containing protein that is significantly induced by CCL2 in human peripheral blood monocytes. The MCPIP proteins include MCPIP-1, MCPIP-2, MCPIP-3, and MCPIP-4, which belong to the CCCH zinc-finger family and are encoded by four genes, Zc3h12a, Zc3h12b, Zc3h12c, and Zc3h12d, respectively (Liang et al., 2008). MCPIP1 expression is highly enriched in macrophage-related organs (thymus, spleen, lung, small intestine, adipose tissue, etc.) (Matsushita et al., 2009). Recent studies have shown that MCPIP1, a negative regulator of macrophage activation, plays an anti-inflammatory role by inhibiting the expression of key proinflammatory cytokines (Liang et al., 2008). Previous data from our lab suggest that MCPIP1 is involved in regulating cell proliferation and migration (Zhu et al., 2015), which are also regulated by small RNA-9 (miR-9) (Yao et al., 2014). However, the detailed mechanism of action of the CCL2/MCPIP1 axis in pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis induced by silica is unclear.

We hypothesized that silica induces AMO activation and apoptosis via MCPIP1, which, in turn, contributes to PFB proliferation and migration in vitro. We demonstrate that MCPIP1 plays an important role in SiO2-induced inflammation and fibrosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats were obtained from Nanjing Medical University Laboratories (Nanjing, China) at 4–8 weeks of age. All animals were housed (4 per cage) in a temperature-controlled room (25 °C, 50% relative humidity) on a 12-h light/dark cycle. All animal procedures were performed in strict accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines, and the animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Southeast University.

Reagents

Crystalline silica (SiO2) was obtained from Sigma (S5631, 1–5 µm), selected by sedimentation according to Stokes’ law, acid hydrolyzed, and baked overnight (200 °C, 16 h) to inactivate endotoxin contamination. The SiO2 dosage used in this study was based on previous studies and dose-response experiments (Supplementary Figure S1A and B) (Brown et al., 2007; Fazzi et al., 2014; Hao et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2015b). Fetal bovine serum (FBS), normal goat serum (NGS), Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; No. 1200-046), and 10× MEM (11430-030) were purchased from Life Technologies. Amphotericin B (BP2645) and GlutaMax Supplement (35050-061) were obtained from Gibco, and Pen-Strep (15140-122) was obtained from Fisher Scientific. PureCol type I bovine collagen (3 mg/ml) was obtained from Advanced Biomatrix. Antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Sigma, Inc., and Cell Signaling.

Primary cultures of rat AMOs

AMOs were harvested by BAL of rats as previously described (Chao et al., 2009). Briefly, rats were anesthetized with 40 mg/kg i.p. pentobarbital sodium. Catheters were placed in the jugular vein (PE50) and trachea (PE240). After euthanasia with an overdose of pentobarbital sodium (150 mg/kg i.v.), the animals were exsanguinated, and BAL was performed as described previously in (Chao et al. (2011). The collected fluid was centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 10 min, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 2 ml of DMEM supplemented with 10% serum, plated in a sterile flask and placed in a 37 °C incubator equilibrated with 5% CO2 in air for 45 min. The supernatant was discarded and replaced with serum-free DMEM.

Isolation and purification of primary rat PFBs

Whole lungs of SD male rats were mechanically dissociated using scissors and tweezers to remove membranes and large blood vessels. Lung tissues were cut into 1 × 1 mm sections, and the tissues were washed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove any blood, placed into a petri dish, and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 3 h. After incubation, 1 ml of DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS was added and incubated overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2. One milliliter of DMEM was added the next day. The medium was changed every 2 days. After 5–6 days, lung fibroblasts were harvested by trypsinization.

Lentiviral transduction of primary rat PFBs with green fluorescent protein

Rat PFBs were transduced with LV-RFP lentivirus (Hanbio, Inc., Shanghai, China) as described previously in Chao et al. (2014). Briefly, P3-4 primary PFBs were cultured in a 24-well plate (1 × 104 cells/well) in DMEM containing 10% FBS for 48 h. The medium was replaced with 1 ml of fresh medium containing 8 µg/ml polybrene. Then, 100 µl of lentivirus solution (107 IU/ml) was added to each well, followed by incubation at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 24 h. After incubation, the treatment medium was replaced with fresh DMEM containing 10% FBS, and the cells were cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2 until the cells reached >50% confluence. The transduced cells were selected using blasticidin as follows. Briefly, the medium was replaced with DMEM containing 10 µg/ml puromycin and 10% FBS, and the cells were cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 24 h. Then, the cells were washed twice with fresh DMEM containing 10% FBS. Pure transduced PFB cultures were expanded and/or stored in liquid nitrogen as described previously in Carlson et al. (2004).

MTT assay

Cell viability was measured via the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) method. Briefly, the cells were collected and seeded in 96-well plates. Different seeding densities were employed at the beginning of the experiments. The cells were exposed to I/R medium. Following incubation for different periods of time (3–24 h), 20 μl of MTT dissolved in Hank’s balanced salt solution was added to each well at a final concentration of 5 μg/ml, and the plates were incubated in a 5% CO2 incubator for 1–4 h. Finally, the medium was aspirated from each well, and 200 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide was added to dissolve the formazan crystals. Then, the absorbance of each well was obtained using a plate reader at reference wavelengths of 570 and 630 nm. Each experiment was repeated at least 3 times.

Fibroblast-populated collagen matrix

The collagen matrix model was utilized as described previously Carlson et al. (2004) and Grinnell et al. (1999). The final matrix parameters were as follows: volume = 0.2 ml; diameter = 12 mm; collagen concentration = 1.5 mg/ml; and cell concentration = 1.0 × 106 cells/ml. The matrices were established in 24-well plates (BD No. 353047), and the cells were incubated in the attached state in DMEM containing 5% FBS for approximately 48 h prior to initiating each experiment.

Gel contraction assay

Fibroblast-populated collagen matrix (FPCM) contraction was determined using the floating matrix contraction assay as described previously in Bell et al. (1979) with minor modifications. Briefly, the matrices were polymerized, covered with DMEM containing 5% FBS, released from the culture well using a sterile spatula, and incubated at 37 °C. At different time points after the matrices were released, they were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4 °C overnight, and images were obtained using a desktop flatbed scanner. The matrix area was measured using ImageJ software, and the data are presented as the ratio of the released matrix area to the attached matrix area.

In vitro scratch assay

Cell migration ability in the 2D culture system was evaluated using an in vitro scratch assay. Briefly, 1 × 105 HPF-a cells were seeded in 24-well tissue culture plates and cultured in growth medium for 24 h, at which point the HPF-a cells were approximately 70–80% confluent. Using a sterile 200-µl pipette tip, a straight line was carefully scratched in the monolayer across the center of the well in a single direction while maintaining the tip perpendicular to the plate bottom. Similarly, a second straight line was scratched perpendicular to the first line to create a cross-shaped cellular gap in each well. Each well was washed twice with 1 ml of fresh growth medium to remove any detached cells. Digital images of the cell gap were captured at different time points, and the gap width was quantitatively evaluated using ImageJ software.

Nested matrix model and cell migration assay

The nested collagen matrix model was used as described previously in Grinnell et al. (2006) with some modifications. For the nested attached matrix, a standard FPCM was incubated in the attached state for 72 h in DMEM containing 10% FBS. Then, the FPCM was removed from the culture well and placed in a 60-µl aliquot of fresh acellular collagen matrix solution (a NeoMatrix solution) centered inside a 12-mm diameter score on the bottom of a new culture well. Next, a 140-µl aliquot of NeoMatrix solution was used to cover the newly transferred FPCM. The NeoMatrix was allowed to polymerize for 1 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2, and then, 2 ml of DMEM containing 10% FBS was added to the well.

Cell migration from the nested FPCM to the acellular NeoMatrix was quantified via fluorescent microscopy at 24 h after nesting. Digital images (constant dimensions of 1000 × 800 µm) were captured using an EVOS FL Cell Imaging microscope (Life Technologies, Grand Island, New York) from 3 to 5 randomly selected microscopic fields at the interface of the nested FPCM with the acellular NeoMatrix. PFB migration from the nested FPCM was quantified by counting the number of cells that had clearly migrated from the nested matrix to the cell-free matrix. The maximum migration distance was quantified by identifying the cell that had migrated the longest distance from the nested matrix to the cell-free matrix. The number of cells per field that had migrated from the nested matrix and the maximum migration distance per field were averaged from these digital micrographs.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was utilized as described previously in Carlson et al. (2004), with minor modifications. Cells were collected from the culture dishes, washed with PBS and lysed using a mammalian cell lysis kit (MCL1-1KT, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The Western blot membranes were probed with primary antibodies. Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies were used (1:5000). The signals were detected using chemiluminescence (SuperSignal West Dura Chemiluminescent Substrate, Thermo Scientific, Grand Island, NY, USA). Each Western blot analysis was repeated using cells from 3 different donors. A single representative immunoblot is shown in each figure. Densitometry was performed using ImageJ software, and the results from all of the repeated experiments were combined into 1 plot.

Immunocytochemistry

Rat AMOs were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4 °C overnight. Then, the fixed samples were permeabilized for 30 min at room temperature (RT) with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS. The permeabilized samples were blocked with PBS containing 10% NGS (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) and 0.3% Triton X-100 at RT for 2 h. The blocked samples were incubated in primary antibodies in PBS containing 10% NGS and 0.3% Triton X-100 at 4 °C overnight. Then, the samples were washed 3 times with PBS and incubated in donkey anti-rabbit (conjugated to Alexa-Fluor 488) and donkey anti-mouse (conjugated to Alexa-Fluor 576) secondary antibodies for 2 h at RT. After the samples were washed 3 times in PBS, they were mounted using mounting solution (Prolong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI; P36931, Life Technologies). The slides were examined under an EVOS FL fluorescence microscope.

RNA interference of MCPIP1 using siRNA

RNA interference targeting MCPIP1 was performed in rat AMOs as described previously in Carlson et al. (2007) with some modifications. The RNA interference protocol for a single well of a 24-well plate was as follows. Briefly, 49 µl of serum-free DMEM was combined with 1 µl of transfection reagent, and 1 µl of siRNA stock was added to 49 µl of serum-free DMEM. Then, both solutions were incubated at RT for 15 min. The transfection reagent and siRNA solutions were mixed together, and the resulting solution was incubated at RT for an additional 15 min. Rat AMOs were seeded at a concentration of 5.0 × 105 cells/100 µl/well in serum-free DMEM. The siRNA-vehicle solution was mixed and incubated at RT for 15 min. The siRNA-vehicle solution was added to the plated cells. The transfected rat AMOs were cultured in serum-free DMEM for 24 h; then, the medium was replaced with DMEM containing 10% FBS for 48 h prior to conducting further experiments. siRNA knockdown efficiency was determined at 2 days after transfection via Western blot analysis.

Statistics

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Unpaired numerical data were compared using the unpaired t-test (2 groups) or ANOVA (more than 2 groups), and statistical significance was set at P < .05.

RESULTS

SiO2 Induced MCPIP1 Expression in Cultured Rat AMOs

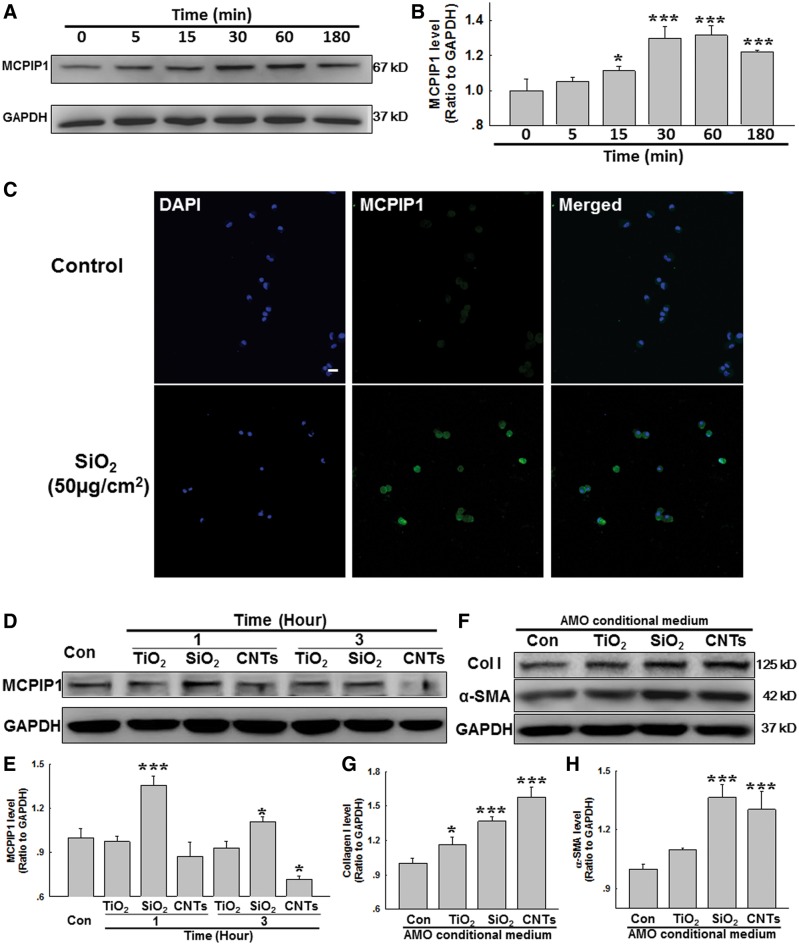

Accumulating evidence suggests that CCL2 plays a critical role in inflammation and fibrosis induced by SiO2 (Liu et al., 2015b; Wang et al., 2015). However, whether MCPIP1 a downstream molecule of CCL2, also mediates the effects of CCL2 in silicosis remains unknown. Thus, AMOs from normal rats were isolated for in vitro experiments. As shown in Figures 1A and B, MCPIP1 expression increased in a time-dependent manner in AMOs after SiO2 treatment, with a peak response at 30 and 60 min. This result was confirmed by immunocytochemical staining (Figure 1C).

FIG. 1.

MCPIP1 expression is increased in primary cultured rat AMOs exposed to SiO2 A, Representative Western blot showing that SiO2 induced rapid and sustained MCPIP1 expression in primary cultured rat AMOs. B, Densitometric analyses of MCPIP1 from 5 separate experiments. *P < .05, ***P < .01 versus. the 0-min group. C, Representative immunocytochemical images showing that SiO2 increased MCPIP1 expression in AMOs. D, Representative Western blot showing MCPIP1 expression in primary cultured rat AMOs after exposure to TiO2 (10 µg/ml), SiO2 (50 µg/cm2), or CNTs (50µg/ml). E, Densitometric analyses of MCPIP1 from 5 separate experiments. *P < .05, ***P < .01 versus. control group. F, Representative Western blot showing that conditional medium from AMOs exposed to TiO2, SiO2, or CNTs induced collagen I and α-SMA expression in cultured rat PFBs. Densitometric analyses of collagen I (G) and α-SMA (H) expression from 5 separate experiments. *P < .05, ***P < .01 versus control group.

To further understand the role of SiO2-induced MCPIP1 in fibrosis, the effect of a nonfibrogenic particle (titanium dioxide, TiO2, 20 µg/ml) (Jawad et al., 2011) and a profibrotic agent (carbon nanotubes [CNTs], 50 μg/ml) (Lee et al., 2012) on MCPIP1 expression was measured in AMOs. As shown in Figures 1D and E, only SiO2 induced MCPIP1 upregulation in AMOs. Interestingly, CNTs inhibited MCPIP1 expression after a 3-h exposure. The physiological relevance of fibrosis was evaluated by measuring the effect of conditional medium from AMOs exposed to TiO2, SiO2, or CNTs on the expression of α-SMA (α smooth muscle actin, a marker of fibroblast activation) and collagen I (an indicator of fibrosis). As expected, conditional medium from AMOs treated with CNTs or SiO2 increased α-SMA and collagen I expression, whereas that from TiO2-treated AMOs only induced a slight increase of collagen I, not α-SMA. Moreover, functional scratch assay experiments were performed with conditional medium; both SiO2 and CNTs, but not TiO2, induced PFB migration (Supplementary Figure S2A and B). These data suggest that the mechanisms involved in fibrosis induced by CNTs and SiO2 are different.

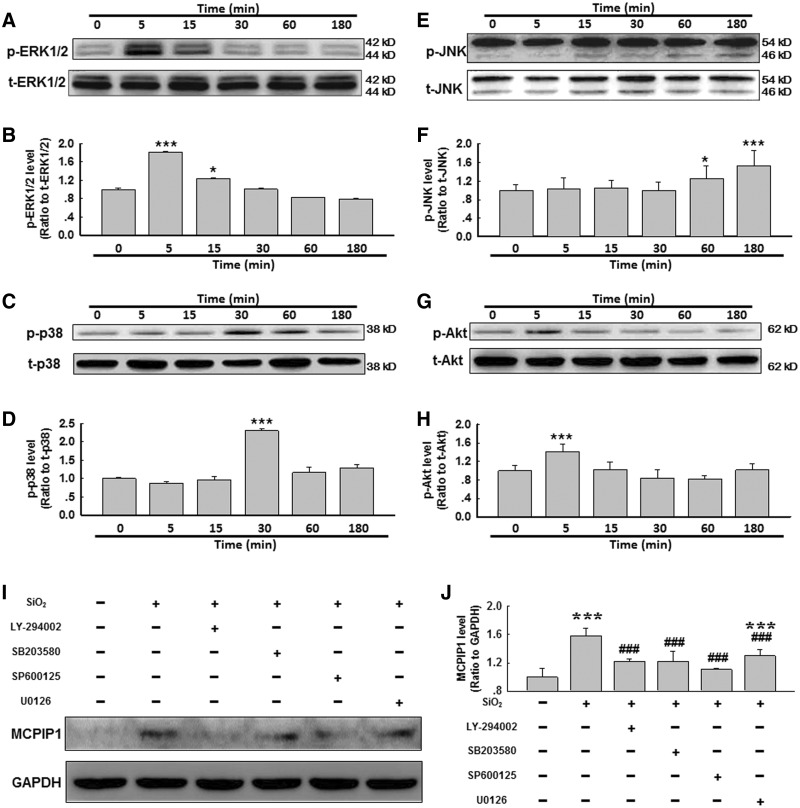

Effect of SiO2 on MAPK and Akt Phosphorylation in AMOs

To further understand the molecular mechanism underlying SiO2-induced MCPIP1 expression, we investigated the potential association between kinase activation and MCPIP1 expression. Thus, we measured MAPK and PI3K/Akt phosphorylation within 3 h of exposure to SiO2. As shown in Figures 2A and B, within 5 min of exposure to SiO2, Erk phosphorylation increased and then diminished. After 30 min of exposure to SiO2, p38 was phosphorylated, peaking at approximately 30–60 min and then tapering off (Figs. 2C and D). c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) also exhibited a rapid activation at 60–180 min after exposure to SiO2 (Figs. 2E and F). Moreover, Akt displayed rapid and transient phosphorylation after exposure to SiO2.

FIG. 2.

SiO2 induced MAPK and PI3K/Akt phosphorylation in primary cultured rat AMOs. Representative Western blot showing that SiO2 induced rapid and transient phosphorylation of ERK (A), p38 (C), JNK (E) and Akt (G) in primary cultured rat AMOs. Densitometric analyses of p-ERK (B), p-p38 (D), p-JNK (F) and p-Akt (H) expression from 5 separate experiments. *P < .05, ***P < .01 versus the 0-min group. I, Representative Western blot showing that SiO2-induced MCPIP1 expression was attenuated by pretreating AMOs with MAPK or PI3K/Akt inhibitors. J, Densitometric analyses of MCPIP1 expression from 5 separate experiments. *P < .05 versus control group; #P < .05 versus SiO2 group.

Effect of the Pharmacological Inhibition of MAPKs or Akt on MCPIP1 Induction after SiO2 Exposure

After confirming that MAPK and Akt activity was enhanced after SiO2 exposure, the effects of pharmacological inhibition of these kinases were examined (Figs. 2I and J). The purpose of these experiments was to determine whether the kinase pathways of interest (JNK, ERK, p38, and PI3K/Akt) regulate MCPIP1 expression in AMOs exposed to SiO2. A 30-min time point after SiO2 exposure was selected to maximize the probability of detecting the effects of kinase inhibition, as this time point corresponded to a relatively large increase in MCPIP1 expression in AMOs after SiO2 exposure (Figs. 1A and B). Pretreatment of AMOs with the commercially available small molecules SP600125 (20 nmol/l, JNK inhibitor), SB203580 (20 nmol/l, p38 inhibitor), or LY-294002 (20 nmol/l, Akt inhibitor) strongly inhibited the SiO2-induced up-regulation of MCPIP1 expression (Figs. 2I and J). However, U0126 (20 nmol/l, MEK inhibitor) only partially inhibited the SiO2-induced up-regulation of MCPIP1 expression (Figs. 2I and J). These results indicate that the SiO2-induced expression of MCPIP1 is primarily mediated by the MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways.

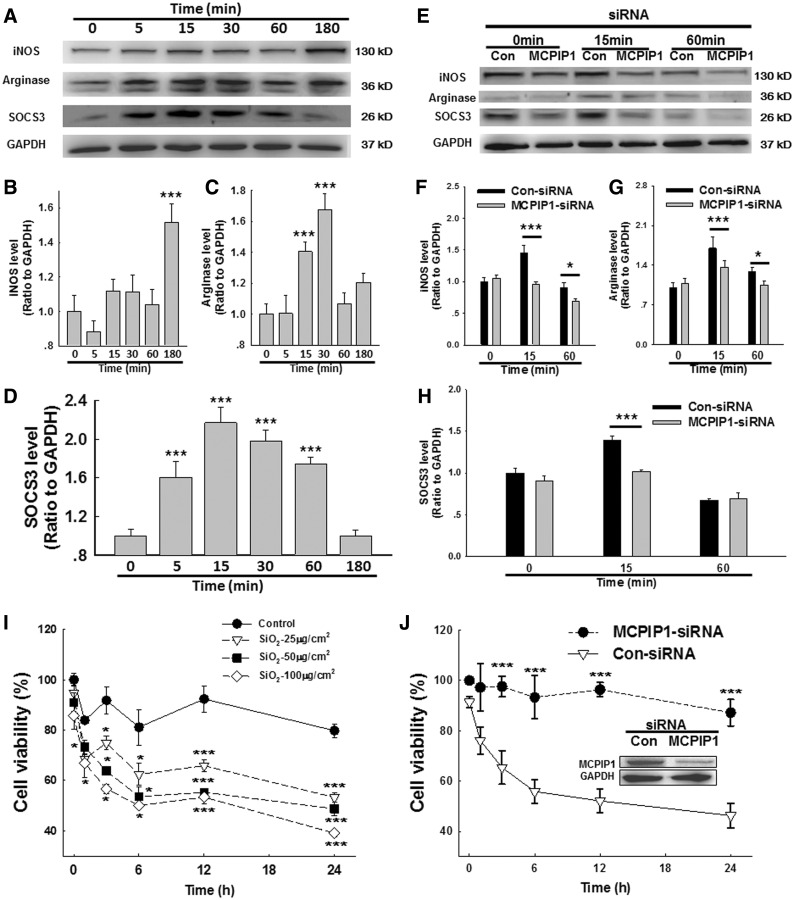

MCPIP1 Is Involved in SiO2-Induced AMO Polarization

Macrophages are a heterogeneous population of immune cells that are essential for the initiation and resolution of pathogen- or damage-induced inflammation. The plasticity of macrophages enables them to respond efficiently and alter their phenotype and physiology in response to environmental cues. Macrophages are classified according to their functional polarization: M1 macrophages produce proinflammatory cytokines, and M2 macrophages secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines and promote tissue repair and remolding as well as tumor progression. As shown in Figures 3A, C, and D, both the M2a marker arginase and the M2c marker SOCS3 exhibited rapid and transient increases in AMOs exposed to SiO2. In contrast, the expression of the M1 marker inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) began to increase after 3 h in AMOs exposed to SiO2, demonstrating an M2–M1 switch during the progression of the inflammatory response and indicating a dual role of macrophages in orchestrating the onset of inflammation and subsequently promoting fibrosis. Moreover, siRNA for MCPIP1 in AMOs significantly inhibited both M1 and M2 polarization induced by SiO2. Moreover, as shown in Figure 3I, SiO2 decreased AMO viability in a dose- and time-dependent manner. MCPIP1 siRNA knockdown rescued the decreased cell viability induced by SiO2 in AMOs (Figure 3G). These results indicate that MCPIP1 influences cell viability during AMO polarization after SiO2 treatment.

FIG. 3.

MCPIP1 is involved in the polarization of AMOs induced by SiO2. A, Representative Western blot showing the effect of SiO2 on the polarization of primary cultured rat AMOs. Densitometric analyses of the M1 marker iNOS (B), M2a marker arginase (C) and M2c marker SOCS3 (D) from 5 separate experiments. *P < .05, ***P < .01 versus the 0-min group. E, Representative Western blot showing that the SiO2-induced macrophage polarization was abolished by MCPIP1 siRNA. Densitometric analyses of iNOS (F), arginase (G), and SOCS3 (H) expression from 5 separate experiments. *P < .05, ***P < .01 versus control at the corresponding time points. I, MTT assay showing that SiO2 decreased the cell viability of primary cultured AMOs in a time- and dose-dependent manner. *P < .05, ***P < .01 versus 0 h in the saline group, n = 5. J, The SiO2-induced effect on cell viability was abolished by MCPIP1 siRNA. ***P < .05 versus control at the corresponding time point.

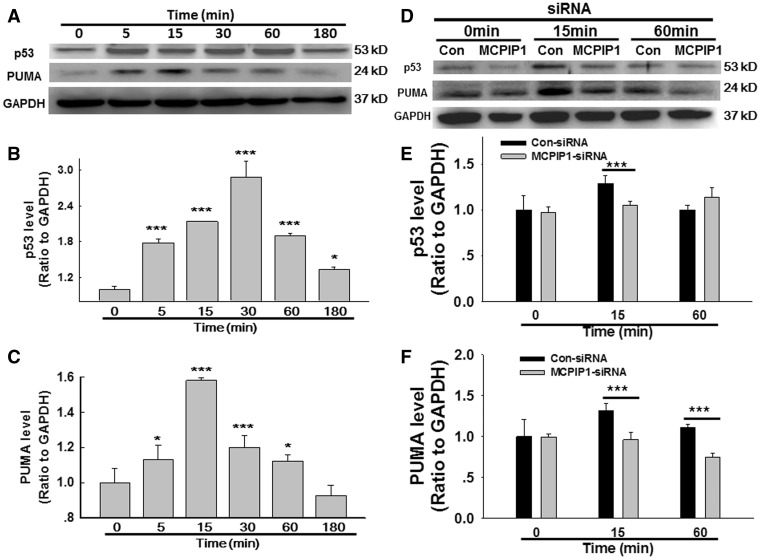

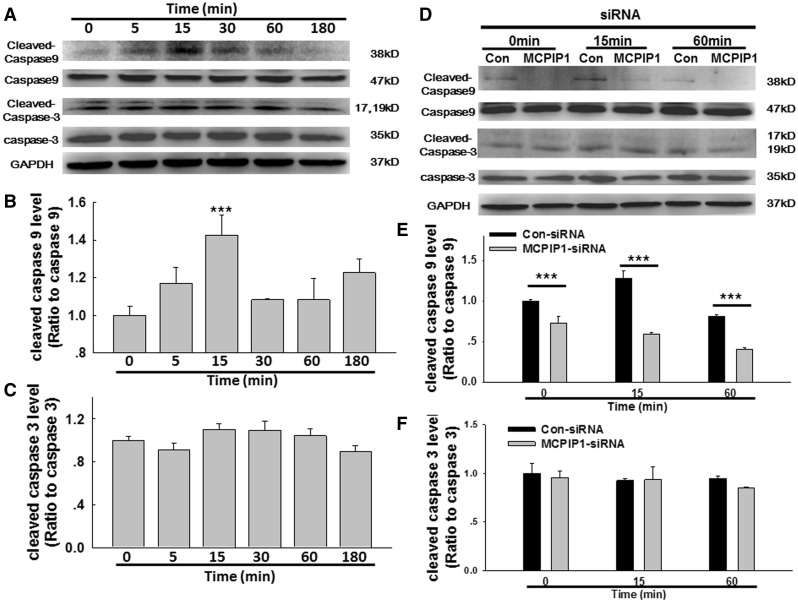

MCPIP1 Is Involved in SiO2-Induced AMO Apoptosis

Previous studies have indicated that MCPIP1 induces p53 expression in cardiovascular macrophages, thereby initiating apoptosis (Zhou et al., 2006). Whether the p53 pathway is also involved in AMO apoptosis in silicosis remain unclear. As shown in Figure 4A and B, SiO2 induced a rapid and transient increase in p53 expression. Moreover, the expression of p53 up-regulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA), a target for activation by p53, exhibited the same pattern of increase in AMOs exposed to SiO2 (Figs. 4A and C). MCPIP1 siRNA was used to determine whether MCPIP1 regulates p53/PUMA expression, and protein levels were determined by immunoblotting (Figs. 4D–F). As expected, siRNA for MCPIP1 inhibited the SiO2-mediated induction of p53/PUMA expression, suggesting that MCPIP1 induces apoptosis via p53/PUMA. Because p53/PUMA induces apoptosis primarily through the caspase pathway, we next detected the expression of initiator and executioner caspases (caspase-9 and caspase-3, respectively). As shown in Figures 5A–C, SiO2 induced a significant increase in caspase-9, but not caspase-3, in cultured AMOs. siRNA for MCPIP1 abolished the increase in caspase-9 induced by SiO2 but did not affect caspase-3 expression (Figs. 5D–F).

FIG. 4.

MCPIP1 is involved in SiO2-induced AMO apoptosis through the p53/PUMA pathway. A, Representative Western blot showing that SiO2 induced rapid and transient p53 and PUMA expression in primary cultured rat AMOs. Densitometric analyses of p53 (B) and PUMA (C) expression from 5 separate experiments. *P < .05, ***P < .01 versus the 0-min group. D, Representative Western blot showing that the SiO2-induced effects on p53 and PUMA expression were abolished by MCPIP1 siRNA. Densitometric analyses of p53 (E) and PUMA (F) expression from 5 separate experiments. *P < .05, ***P < .01 versus control at the corresponding time points.

FIG. 5.

MCPIP1 is involved in SiO2-induced AMO apoptosis through the caspase-9 pathway, A, Representative Western blot showing that SiO2 induced rapid and transient caspase-9, but not caspase-3, expression in primary cultured rat AMOs. Densitometric analyses of caspase-9 (B) and caspase-3 (C) expression from 5 separate experiments. *P < .05, ***P < .01 versus the 0-min group. D, Representative Western blot showing that the SiO2-induced effect on caspase-9 expression was abolished by siRNA for MCPIP1. Densitometric analyses of caspase-9 (E) and caspase-3 (F) expression from 5 separate experiments. *P < .05, ***P < .01 versus control at the corresponding time points.

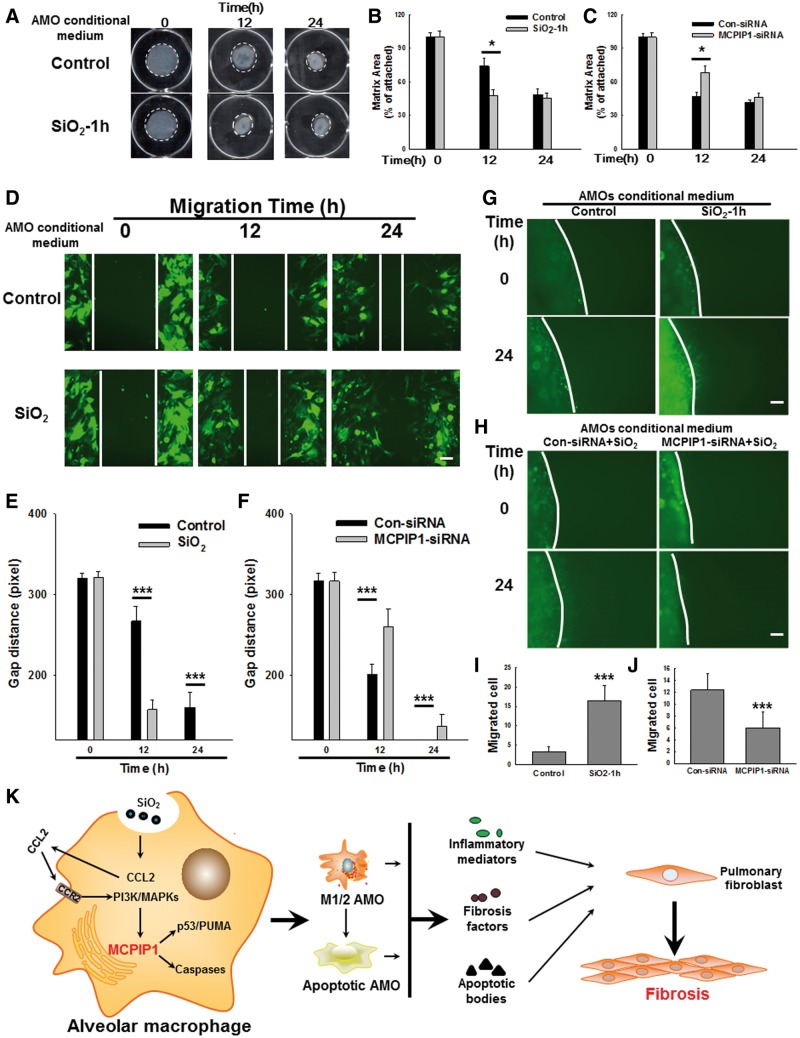

Effects of siRNA for MCPIP1 in AMOs on FPCM Contraction

To understand the functional relevance of the changes in MCPIP1 expression in AMOs on SiO2-induced fibrosis, a gel contraction assay was utilized to evaluate fibroblast activity (Grinnell and Petroll, 2010). First, culture medium from AMOs treated with or without SiO2 (conditional medium) was subjected to a gel contraction assay. As shown in Figures 6A and B, conditional medium from the SiO2-treated group induced a significant increase in gel contraction, suggesting that fibroblast activity was up-regulated by a fibrosis factor released by AMOs. Next, conditioned medium from AMOs treated with either control siRNA or siRNA for MCPIP1 was subjected to a gel contraction assay. As shown in Figure 6C, conditional medium from SiO2- and control siRNA-treated AMOs induced gel contraction. However, siRNA for MCPIP1 abolished the fibrosis factor-induced increase in gel contraction.

FIG. 6.

AMO-derived MCPIP1 mediated the SiO2-induced fibroblast activation and migration. A, Representative images of the collagen gel size showing that SiO2 increased gel contraction (indicating fibroblast activation). B, Quantification of gel size at different time points after SiO2 exposure. C, Quantification of gel size at different time points after SiO2 exposure, indicating that siRNA forRNAi of MCPIP1 inhibited SiO2-induced fibroblast activation. ***P < .01 versus control at the corresponding time points. D, Representative images showing that SiO2 induced the migration of GFP-labeled rat fibroblasts cultured as a monolayer. Scale bar = 80 µm. E, Quantification of the scratch gap distance from 6 separate experiments. ***P < .01 versus control at the corresponding time points. F, Quantification of the scratch gap distance at different time points after SiO2 exposure, indicating that siRNA forRNAi of MCPIP1 inhibited SiO2-induced fibroblast migration. ***P < .01 versus control at the corresponding time points. Representative images (G) and quantification of the number of migrated cells (H), indicating that SiO2 induced the migration of GFP-labeled rat fibroblasts in the nested gel matrix. Scale bar = 80 µm. ***P < .01 versus control. Quantification of the number of migrated cells (J), indicating that siRNA forRNAi of MCPIP1 inhibited SiO2-induced fibroblast migration. ***P < .01 versus control. K, Schematic of the inflammatory cascade and fibrosis initiated by SiO2.

Effect of siRNA for MCPIP1 in AMOs on Fibroblast Migration

Increasing evidence suggests that PFB migration is a critical aspect of pulmonary fibrosis. Therefore, we explored the roles of MCPIP1 in SiO2-mediated cell migration. As shown in Figures 6D and E, SiO2-treated AMO conditional medium significantly increased PFB migration in scratch assays. However, MCPIP1 siRNA-treated AMO conditional medium inhibited the increase in cell migration (Figure 6F).

Significant differences have been observed in cell physiology between 2D and 3D in vitro culture systems (Grinnell, 2003; Pampaloni et al., 2007; Rhee, 2009; Rhee and Grinnell, 2007). The FPCM culture system has facilitated the analysis of fibroblast physiology under conditions that more closely resemble the in vivo environment than conventional 2D cell culture systems (Lee et al., 2000). After determining that MCPIP1 participated in fibroblast migration based on the scratch assays, we sought to validate these findings by monitoring fibroblast migration in a 3D cell culture system. As shown in Figures 6G and I, conditional medium from the SiO2-treated group significantly increased cell migration, similar to the results observed in the scratch assay. Moreover, conditional medium from SiO2- and control siRNA-treated AMOs induced cell migration, whereas that from MCPIP1 siRNA-treated AMOs suppressed the increase in cell migration (Figs. 6H and J).

DISCUSSION

Silicosis is an occupational disease caused by the inhalation of silica, and it is characterized by pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis (Moore et al., 2003; Rao et al., 2004). AMOs are the most important barrier in pulmonary innate immunity (Hamilton et al., 2008; Huaux, 2007; Leung et al., 2012; Thakur et al., 2009). Accumulating data suggest that silica-induced pulmonary inflammation occurs after apoptosis rather than necrosis (Bhandary et al., 2015; Delgado et al., 2006; Lim et al., 1999; Pfau et al., 2004). AMO apoptosis is an underlying mechanism for the development of silicosis (Borges et al., 2001; Gu et al., 2013; Lim et al., 1999). In this study, we focused on the effects of AMO-derived MCPIP1 on cell proliferation and the activation of PFBs in vitro.

CCL2 is a proinflammatory factor released by activated AMOs that has been linked to different types of inflammatory disease (Baggiolini and Dahinden, 1994; Ransohoff et al., 1996; Zickus et al., 1998). The role of AMO-expressed CCL2 in pulmonary fibrosis has been previously investigated (Gharaee-Kermani et al., 1996; Moore et al., 2001; Zickus et al., 1998). Recent studies and data from our lab suggest that fibroblast-derived CCL2 is an important mediator of SiO2-induced fibrosis (Gharaee-Kermani et al., 1996; Rao et al., 2004, 2005; Wang et al., 2015). Among the molecules that are downstream of CCL2, MCPIP1 has been identified as a negative regulator of macrophage activation (Huang et al., 2012; Liang et al., 2008). However, the mechanisms of action of AMO-derived MCPIP1 in silicosis have not been elucidated. Our data demonstrate that SiO2 induced a rapid and sustained up-regulation of MCPIP1 expression in primary cultured AMOs, which was linked to apoptosis through the caspase-9 and p53/PUMA pathways. Previous data suggest that MCPIP1 is significantly up-regulated during stress, which disassembles stress granules and promotes cellular apoptosis (Qi et al., 2011). Further, MCPIP1 evoked the activation of JNK and p38, as well as the induction of p53 and PUMA, which subsequently induced autophagy and apoptosis in H9c2 cells (Younce and Kolattukudy, 2010). Our results provide further molecular insight into the mechanism by which the elevated MCPIP1 levels associated with chronic inflammation contribute to the development of SiO2-induced fibrosis. Interestingly, although caspase-9 was up-regulated in association with MCPIP1 expression, the downstream caspase-3 was not affected (Figs. 4A–C). Indeed, MCPIP1 has been shown to promote angiogenesis through transcriptional activation of cdh12 and cdh19, suggesting a complicated role for MCPIP1 in the regulation of cell fate (Niu et al., 2008).

In this study, SiO2 exposure resulted in JNK, p38, Erk, MAPK, and PI3K/Akt phosphorylation in AMOs, similar to a previous finding in fibroblasts (Liu et al., 2015a; Wang et al., 2015). Moreover, blockade of the JNK, p38, Erk, and Akt pathways inhibited MCPIP1 expression (Figs. 2I and J), indicating the general involvement of the MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways in silicosis. AMOs are the most prevalent resident cell in the lung (Chao et al., 2009), and they become activated after SiO2 exposure. In contrast to the inverse correlation between M1 and M2 macrophage activation in response to environmental stimuli (Genin et al., 2015; Gordon, 2003), SiO2 increased both the M1 and M2 types of AMOs (Figs. 3A–D). M1 macrophages are characterized by the production of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-12, while M2 macrophages produce anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10, CCL18, and CCL22 (Gordon, 2003; Martinez et al., 2009; Van Ginderachter et al., 2006). SiO2 induced a rapid and transient increase in M2 macrophages, whereas there was a delayed increase in M1 macrophages, indicating a switch between M1 and M2 in a different stage of AMO activation by SiO2. Moreover, MCPIP1 knockdown inhibited both M1 and M2 polarization, suggesting that MCPIP1 inhibits macrophage activation but does not switch macrophage type (M1/M2). A recent study in MCF-7 cells suggested that sphingosine-1-phosphate caused a switch in macrophage phenotype from M1 to M2 (Jain, 2005). The key factor involved in macrophage polarization in silicosis needs to be further investigated.

Fibroblast activation is the first step in SiO2-induced fibrosis (Chao et al., 2014; Grinnell, 1994; Liu et al., 2015b). Recent studies have shown the direct effect of SiO2 on fibroblast activation, which involves p53/PUMA and CCL2 (Liu et al., 2015b; Wang et al., 2015). Interestingly, although SiO2 induced MCPIP1 expression in PFBs, MCPIP1 upregulation has been shown to be involved specifically in regulating fibroblast migration rather than in a widespread cellular response (Liu et al., 2015a). Here, we provide another example of the indirect effects of MCPIP1 on fibroblasts; MCPIP1 was upregulated in AMOs in response to SiO2 and mediated fibroblast activation. Moreover, the fibroblast activation induced by AMO conditional medium did not last long, as indicated by the lack of a difference between the control and SiO2 groups after 24 h. One explanation is that the presumed fibroblast activator released by AMOs produced only a rapid and reversible effect on the fibroblasts. In vivo, SiO2 induce AMO apoptosis, and monocytes are then recruited to the lungs, where they differentiate into macrophages, which can maintain the levels of the fibroblast activator and produce a sustained effect. All these data indicate a complex mechanism of fibrosis induced by SiO2. Moreover, MCPIP1 knockdown prevented the rapid effects of AMO conditional medium, indicating the involvement of more than 1 fibroblast activator in this process. Previous data from our lab suggest that direct exposure of fibroblasts to SiO2 induces their rapid and sustained activation, indicating that multiple mechanisms are involved in SiO2-induced fibrosis. Taken together, current data suggest that MCPIP1 plays an important role in the interaction between AMOs and PFBs. Fibroblast migration is a critical aspect of pulmonary fibrosis. MCPIP1 has been shown to promote HUVEC migration (Niu et al., 2008). In addition, CCL2-knockout mice exhibit delayed wound re-epithelialization and angiogenesis (Low et al., 2001). Given these roles of CCL2 and MCPIP1 in cell migration, we sought to determine whether MCPIP1 participates in the signaling events that regulate fibroblast functions relevant to silicosis, such as proliferation, contraction, and migration.

Fibroblast function in silicosis has been studied extensively in 2D cell culture models; however, discrepancies between cell behaviors in culture and in vivo have motivated an increasing number of research groups to utilize 3D models, which better represent the living tissue microenvironment (Even-Ram and Yamada, 2005). Fibroblast migration/motility is a complicated process that involves cell-matrix adhesion, cell-matrix interaction, and global/local matrix remodeling (Rhee and Grinnell, 2007). The nested collagen matrix model is an easy, rapid, reliable, and quantitative method for measuring fibroblast migration/motility in 3D models (Grinnell et al., 2006; Silva et al., 2012; Zhou and Petroll, 2010). Fibroblasts within the embedded matrix of the nested model have a morphology similar to that of normal fibroblasts in tissues (Goldsmith et al., 2004; Langevin et al., 2005) and biosynthetic features of the resting dermis (Grinnell, 2003; Kessler et al., 2001). Although the understanding of fibroblast migration in 2D cell culture systems has improved (Rodriguez-Menocal et al., 2012), the mechanisms underlying cell migration in 3D cell culture systems remain less clear. Herein, we provide new insights into the novel roles of MCPIP1 in regulating fibroblast migration in both 2D and 3D cell culture systems. Our results indicate that SiO2 induced MCPIP1 expression by activating the MAPK and PI3K pathways. Furthermore, we determined that p53, which is downstream of MCPIP1, is involved in this process (Figure 4). In addition to fibroblast migration, other silicosis-mediated processes, such as collagen matrix contraction, represent important fibroblast functions in matrix, and these processes indicate fibroblast activation. MCPIP1 knockdown inhibited fibroblast activation by SiO2. These findings suggest that MCPIP1 is involved in regulating fibroblast activation and migration in silicosis.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, our findings demonstrate that SiO2 induces MCPIP1 expression in AMOs and that MCPIP1 plays a vital role in AMO apoptosis and PFB activation/migration; these data will expand our knowledge of MCPIP1 in silicosis (Figure 6K).

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at http://toxsci.oxfordjournals.org/.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study is the result of work that was partially supported by the resources and facilities at the core lab at the Medical School of Southeast University.

FUNDING

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81473263), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, China (BK20141347 and BK20141497), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (China).

REFERENCES

- Baggiolini M., Dahinden C. A. (1994). CC chemokines in allergic inflammation. Immunol. Today 15, 127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell E., Ivarsson B., Merrill C. (1979). Production of a tissue-like structure by contraction of collagen lattices by human fibroblasts of different proliferative potential in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 76, 1274–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandary Y. P., Shetty S. K., Marudamuthu A. S., Fu J., Pinson B. M., Levin J., Shetty S. (2015). Role of p53-fibrinolytic system cross-talk in the regulation of quartz-induced lung injury. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 283, 92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges V. M., Falcao H., Leite-Junior J. H., Alvim L., Teixeira G. P., Russo M., Nobrega A. F., Lopes M. F., Rocco P. M., Davidson W. F, et al. (2001). Fas ligand triggers pulmonary silicosis. J. Exp. Med. 194, 155–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. M., Swindle E. J., Kushnir-Sukhov N. M., Holian A., Metcalfe D. D. (2007). Silica-directed mast cell activation is enhanced by scavenger receptors. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 36, 43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M. A., Longaker M. T., Thompson J. S. (2004). Modulation of FAK, Akt, and p53 by stress release of the fibroblast-populated collagen matrix. J. Surg. Res. 120, 171–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M. A., Prall A. K., Gums J. J. (2007). RNA interference in human foreskin fibroblasts within the three-dimensional collagen matrix. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 306, 123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao J., Wood J. G., Blanco V. G., Gonzalez N. C. (2009). The systemic inflammation of alveolar hypoxia is initiated by alveolar macrophage-borne mediator(s). Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 41, 573–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao J., Donham P., van Rooijen N., Wood J. G., Gonzalez N. C. (2011). Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 released from alveolar macrophages mediates the systemic inflammation of acute alveolar hypoxia. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 45, 53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao J., Pena T., Heimann D. G., Hansen C., Doyle D. A., Yanala U. R., Guenther T. M., Carlson M. A. (2014). Expression of green fluorescent protein in human foreskin fibroblasts for use in 2D and 3D culture models. Wound Repair Regen. 22, 134–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado L., Parra E. R., Capelozzi V. L. (2006). Apoptosis and extracellular matrix remodelling in human silicosis. Histopathology 49, 283–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Even-Ram S., Yamada K. M. (2005). Cell migration in 3D matrix. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 17, 524–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazzi F., Njah J., Di Giuseppe M., Winnica D. E., Go K., Sala E., St Croix C. M., Watkins S. C., Tyurin V. A., Phinney D. G, et al. (2014). TNFR1/phox interaction and TNFR1 mitochondrial translocation Thwart silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis. J. Immunol. 192, 3837–3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura N. (2000). Pathology and pathophysiology of pneumoconiosis. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 6, 140–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genin M., Clement F., Fattaccioli A., Raes M., Michiels C. (2015). M1 and M2 macrophages derived from THP-1 cells differentially modulate the response of cancer cells to etoposide. BMC Cancer 15, 577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharaee-Kermani M., Denholm E. M., Phan S. H. (1996). Costimulation of fibroblast collagen and transforming growth factor beta1 gene expression by monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 via specific receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 17779–17784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith E. C., Hoffman A., Morales M. O., Potts J. D., Price R. L., McFadden A., Rice M., Borg T. K. (2004). Organization of fibroblasts in the heart. Dev. Dyn. 230, 787–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon S. (2003). Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 23–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinnell F. (1994). Fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and wound contraction. J. Cell. Biol. 124, 401–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinnell F., Zhu M., Carlson M. A., Abrams J. M. (1999). Release of mechanical tension triggers apoptosis of human fibroblasts in a model of regressing granulation tissue. Exp. Cell. Res. 248, 608–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinnell F. (2003). Fibroblast biology in three-dimensional collagen matrices. Trends Cell. Biol. 13, 264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinnell F., Rocha L. B., Iucu C., Rhee S., Jiang H. (2006). Nested collagen matrices: a new model to study migration of human fibroblast populations in three dimensions. Exp. Cell. Res. 312, 86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinnell F., Petroll W. M. (2010). Cell motility and mechanics in three-dimensional collagen matrices. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 26, 335–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu W., Song J., Cao Y., Sun Q., Yao H., Wu Q., Chao J., Zhou J., Xue W., Duan J. (2013). Application of the ITS2 region for barcoding medicinal plants of selaginellaceae in pteridophyta. PLoS One 8, e67818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton R. F., Jr., Thakur S. A., Holian A. (2008). Silica binding and toxicity in alveolar macrophages. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 44, 1246–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao C. F., Li X. F., Yao W. (2013). Role of insulin-like growth factor II receptor in transdifferentiation of free silica-induced primary rat lung fibroblasts. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 26, 979–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S., Qi D., Liang J., Miao R., Minagawa K., Quinn T., Matsui T., Fan D., Liu J., Fu M. (2012). The putative tumor suppressor Zc3h12d modulates toll-like receptor signaling in macrophages. Cell. Signal. 24, 569–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huaux F. (2007). New developments in the understanding of immunology in silicosis. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 7, 168–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain R. K. (2005). Normalization of tumor vasculature: an emerging concept in antiangiogenic therapy. Science 307, 58–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jawad H., Boccaccini A. R., Ali N. N., Harding S. E. (2011). Assessment of cellular toxicity of TiO2 nanoparticles for cardiac tissue engineering applications. Nanotoxicology 5, 372–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler D., Dethlefsen S., Haase I., Plomann M., Hirche F., Krieg T., Eckes B. (2001). Fibroblasts in mechanically stressed collagen lattices assume a “synthetic” phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 36575–36585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langevin H. M., Bouffard N. A., Badger G. J., Iatridis J. C., Howe A. K. (2005). Dynamic fibroblast cytoskeletal response to subcutaneous tissue stretch ex vivo and in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 288, C747–C756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. J., Rosenfeldt H., Grinnell F. (2000). Activation of ERK and p38 MAP kinases in human fibroblasts during collagen matrix contraction. Exp. Cell Res. 257, 190–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. K., Sayers B. C., Chun K. S., Lao H. C., Shipley-Phillips J. K., Bonner J. C., Langenbach R. (2012). Multi-walled carbon nanotubes induce COX-2 and iNOS expression via MAP kinase-dependent and -independent mechanisms in mouse RAW264.7 macrophages. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 9, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung C. C., Yu I. T., Chen W. (2012). Silicosis. Lancet 379, 2008–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J., Wang J., Azfer A., Song W., Tromp G., Kolattukudy P. E., Fu M. (2008). A novel CCCH-zinc finger protein family regulates proinflammatory activation of macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 6337–6346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim Y., Kim J. H., Kim K. A., Chang H. S., Park Y. M., Ahn B. Y., Phee Y. G. (1999). Silica-induced apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Toxicol. Lett. 108, 335–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Dai X., Cheng Y., Fang S., Zhang Y., Wang X., Zhang W., Liao H., Yao H., Chao J. (2015a). MCPIP1 mediates silica-induced cell migration in human pulmonary fibroblasts. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. ajplung 00278 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Fang S., Liu H., Wang X., Dai X., Yin Q., Yun T., Wang W., Zhang Y., Liao H., et al. (2015b). Role of human pulmonary fibroblast-derived MCP-1 in cell activation and migration in experimental silicosis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 288, 152–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low Q. E., Drugea I. A., Duffner L. A., Quinn D. G., Cook D. N., Rollins B. J., Kovacs E. J., DiPietro L. A. (2001). Wound healing in MIP-1alpha(-/-) and MCP-1(-/-) mice. Am. J. Pathol. 159, 457–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez F. O., Helming L., Gordon S. (2009). Alternative activation of macrophages: an immunologic functional perspective. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27, 451–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita K., Takeuchi O., Standley D. M., Kumagai Y., Kawagoe T., Miyake T., Satoh T., Kato H., Tsujimura T., Nakamura H., Akira S. (2009). Zc3h12a is an RNase essential for controlling immune responses by regulating mRNA decay. Nature 458, 1185–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore B. B., Paine R., 3rd, Christensen P. J., Moore T. A., Sitterding S., Ngan R., Wilke C. A., Kuziel W. A., Toews G. B. (2001). Protection from pulmonary fibrosis in the absence of CCR2 signaling. J. Immunol. 167, 4368–4377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore B. B., Peters-Golden M., Christensen P. J., Lama V., Kuziel W. A., Paine R., 3rd., Toews G. B. (2003). Alveolar epithelial cell inhibition of fibroblast proliferation is regulated by MCP-1/CCR2 and mediated by PGE2. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 284, L342–L349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossman B. T., Churg A. (1998). Mechanisms in the pathogenesis of asbestosis and silicosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 157, 1666–1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu J., Azfer A., Zhelyabovska O., Fatma S., Kolattukudy P. E. (2008). Monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP)-1 promotes angiogenesis via a novel transcription factor, MCP-1-induced protein (MCPIP). The. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 14542–14551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampaloni F., Reynaud E. G., Stelzer E. H. (2007). The third dimension bridges the gap between cell culture and live tissue. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8, 839–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfau J. C., Brown J. M., Holian A. (2004). Silica-exposed mice generate autoantibodies to apoptotic cells. Toxicology 195, 167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi D., Huang S., Miao R., She Z. G., Quinn T., Chang Y., Liu J., Fan D., Chen Y. E., Fu M. (2011). Monocyte chemotactic protein-induced protein 1 (MCPIP1) suppresses stress granule formation and determines apoptosis under stress. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 41692–41700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransohoff R. M., Glabinski A., Tani M. (1996). Chemokines in immune-mediated inflammation of the central nervous system. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 7, 35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao K. M., Porter D. W., Meighan T., Castranova V. (2004). The sources of inflammatory mediators in the lung after silica exposure. Environ. Health Perspect. 112, 1679–1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao K. M., Ma J. Y., Meighan T., Barger M. W., Pack D., Vallyathan V. (2005). Time course of gene expression of inflammatory mediators in rat lung after diesel exhaust particle exposure. Environ. Health Perspect. 113, 612–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee S., Grinnell F. (2007). Fibroblast mechanics in 3D collagen matrices. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 59, 1299–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee S. (2009). Fibroblasts in three dimensional matrices: cell migration and matrix remodeling. Exp. Mol. Med. 41, 858–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Menocal L., Salgado M., Ford D., Van Badiavas E. (2012). Stimulation of skin and wound fibroblast migration by mesenchymal stem cells derived from normal donors and chronic wound patients. Stem Cells Trans. Med. 1, 221–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva D., Caceres M., Arancibia R., Martinez C., Martinez J., Smith P. C. (2012). Effects of cigarette smoke and nicotine on cell viability, migration and myofibroblastic differentiation. J. Periodontal. Res. 47, 599–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur S. A., Hamilton R., Jr., Pikkarainen T., Holian A. (2009). Differential binding of inorganic particles to MARCO. Toxicol. Sci. 107, 238–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ginderachter J. A., Movahedi K., Hassanzadeh Ghassabeh G., Meerschaut S., Beschin A., Raes G., De Baetselier P. (2006). Classical and alternative activation of mononuclear phagocytes: picking the best of both worlds for tumor promotion. Immunobiology 211, 487–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Liu H., Dai X., Fang S., Wang X., Zhang Y., Yao H., Zhang X., Chao J. (2015). p53/PUMA expression in human pulmonary fibroblasts mediates cell activation and migration in silicosis. Sci. Rep. 5, 16900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H., Ma R., Yang L., Hu G., Chen X., Duan M., Kook Y., Niu F., Liao K., Fu M., et al. (2014). MiR-9 promotes microglial activation by targeting MCPIP1. Nat. Commun. 5, 4386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younce C. W., Kolattukudy P. E. (2010). MCP-1 causes cardiomyoblast death via autophagy resulting from ER stress caused by oxidative stress generated by inducing a novel zinc-finger protein, MCPIP. Biochem. J. 426, 43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C., Petroll W. M. (2010). Rho kinase regulation of fibroblast migratory mechanics in fibrillar collagen matrices. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 3, 76–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L., Azfer A., Niu J., Graham S., Choudhury M., Adamski F. M., Younce C., Binkley P. F., Kolattukudy P. E. (2006). Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 induces a novel transcription factor that causes cardiac myocyte apoptosis and ventricular dysfunction. Circ. Res. 98, 1177–1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu T., Yao Q., Hu X., Chen C., Yao H., Chao J. (2015). The Role of MCPIP1 in Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury-Induced HUVEC Migration and Apoptosis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 37, 577–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zickus C., Kunkel S. L., Simpson K., Evanoff H., Glass M., Strieter R. M., Lukacs N. W. (1998). Differential regulation of C-C chemokines during fibroblast-monocyte interactions: adhesion vs. inflammatory cytokine pathways. Mediators Inflamm 7, 269–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.